Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.35 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2021/n35a7

The return of Rosie the Riveter: Contemporary popular reappropriations of the iconic World War II image

Belinda du Plooy

Engagement Office, Engagement and Transformation Division, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. belinda.duplooy@mandela.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5036-1814)

ABSTRACT

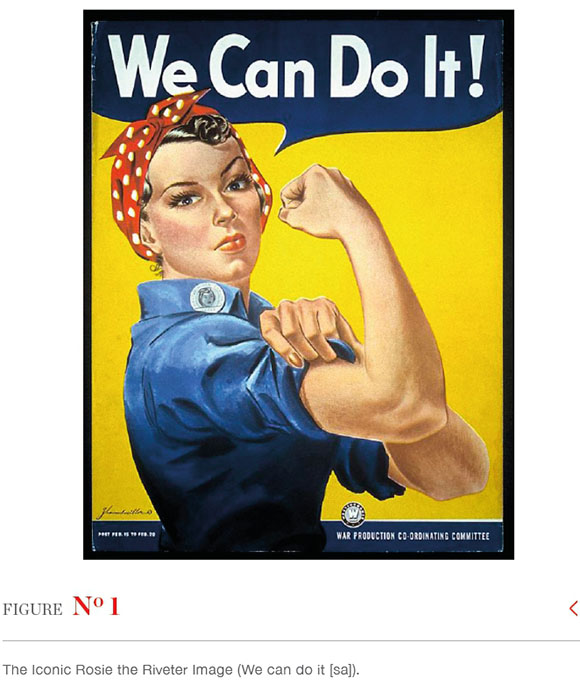

The iconic image of Rosie the Riveter played an important role in American patriotic ideological processes during World War II. Aimed at the recruitment of women for wartime work, particularly in factories and traditionally masculine occupations, this representation of a woman in overalls and head scarf, with sleeves rolled up, showing her bicep and balled fist, declaring 'We can do it', has been a contentious point of discussion for its significance in feminist agendas since its first appearance. While building on, and playing to, the suffrage agendas of first wave feminism, the popular image of Rosie was transcended by second wave concerns about depictions of women in the workplace, such as those in films like Norma Rae (Ritt 1979), Silkwood (Nichols 1983), North Country (Caro 2005) and Made in Dagenheim (Cole 2010). But Rosie is making a comeback. The image has recently been appropriated in various ways and for various purposes - naively, ironically, satirically, as bricolage, pastiche and in sexualised portrayals - to represent contemporary women's issues and concerns, as well as arguably forming part of a backlash culture against feminism. Contemporary depictions have, for example, ranged from Hilary Clinton, Sarah Palin, Michelle Obama, Malala Yousafzai and Beyoncé. This paper considers the development and transformation of the image of Rosie the Riveter and its contradictory (re)-appropriations in various contemporary popular cultural discourses.

Keywords: feminist expression, Michel Foucault, gender roles, popular culture, Rosie the Riveter.

Introduction

Iconic images often function effectively at a symbolic level because they conjure a sense of both familiarity and nostalgia, closeness and longing, in the viewer. Analyses have shown how this can be used for a variety of ideological purposes by creators, interpreters and manipulators of imagery and discourse. In this paper, I consider one specific iconic image that has become a carrier of multifarious significations - both of female potential and limitations - namely Rosie the Riveter, a familiar and often nostalgic World War II poster image. Currently, in the third decade of the twenty-first century, Rosie the Riveter is making a post-millennial comeback. It is 100 and 75 years, respectively, after the two World Wars in 1914-1919 and 1939-1945, as well as 50 years after the start of the Vietnam War in 1965. Since its creation, the image of Rosie has been appropriated in various ways and for various purposes, often in complex combinations, to represent women's issues.

It is reported that the number of women in the American workforce increased by at least 10 per cent during the Second World War years, from 26 per cent to 36 per cent, which meant that the number of women workers rose from 14 million to 19 million, of which a large percentage was factory workers (Kopp 2007:591 cited by Baxandall, Gordon & Reverby 1976). The iconic image that came to be known as Rosie the Riveter has become part of western cultural mythology and played an important part in American patriotic ideological processes during World War II. This representation of a woman in overalls and head scarf, with sleeves rolled up, showing her bicep and balled fist, declaring '[w]e can do it', has been a contentious point of discussion for both its feminist agenda and its lack thereof. It is now commonly believed (erroneously, according to Gwen Sharp & Lisa Wade 2011, James Kimble 2016, and James Kimble & Lester Olsen 2006) to have been aimed at the recruitment of women for wartime work, particularly in the armament industry, on factory production lines and in offices: thus, for traditionally male jobs.

Following the suffrage agenda of the turn of first wave feminism in the nineteenth century, the 1940s wartime image of Rosie was superseded, in the 1960s and 1970s, by second wave concerns about women in the workplace and civic spaces. Book-ended by what is now viewed as the first two waves of feminist theory and activism in western culture (Evans 2015), Rosie is historically situated at the interstices of ideological cross-appropriation and re-interpretation. Paradoxically, she has now become a simultaneous contraction and expansion of the gender(ed) roles and politics of several generations.

In this paper, I consider the ways in which this image has recently been (re)appropriated in a variety of contemporary popular cultural discourses and contexts. I begin with a short description of some of the easily accessible versions of the Rosie iconography (all obtainable via the internet and a simple web search). I follow with a short contextualising his(her)storical perspective of what is now called "Rosie the Riveter" and the myths surrounding her, many of which have already been debunked and which I briefly summarise. As one example, I then consider the image of Rosie as part of the contemporary revivalist/"vintage" performance of Second World War nostalgia and its, sometimes overt, but more often subliminal, discursive and ideological implications in terms of gender(ed) performativity and masquerade (Butler 1997; 2005; 2011a; 2011b). I situate my reading of the imagery in the context of ideological and poststructuralist criticism and apply the thoughts of critical theorists of ideology, power and culture, such as Michel Foucault, Slavoj Zizek, Angela McRobbie and Judith Butler, to my reading.

Rosie is potentially 'a powerful platform ... for communicating messages of unified yet complex political dissent' (Wiederhold & Field-Springer 2015:147), but she is also caught in what McRobbie describes as a postfeminist 'double entanglement', in Foucault's 'heterotopic experience', in Zizek's 'ideological myopia' and in Butler's 'gender performativity'. I argue that Rosie is now, and possibly always has been, an empty or open signifier, a simulacrum and palimpsest of herself, which transcends not only her original post-war intent, but also her second wave iterations. In this way, and with the increasing aid of communication and cyber-technologies, the image of Rosie the Riveter has, in less than a century, become a multi-vocal, multi-purposed signifier, a contemporary ideologically distorted dreamscape where all manner of heterotopic experiences (Foucauldian crisis, deviation and compensation) play themselves out in individual and collective forms. Reclaiming Rosie for feminism requires, in the first place, recontextualising her into the historical positions that she occupied during wartime and in feminism's second wave, and then newly and productively reinscribing her with historically contextualised meaning for post-millennial generations.

Contemporary Rosie iconography and iterations

A simple Google search shows that contemporary Rosie iconography ranges from, for example, depictions of Hillary Clinton, Sarah Palin, Michelle Obama, Malala Yousafzai, Beyoncé, Britney Spears, Marge Simpson, the Muppet's Miss Piggy, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Princess Leia, comic book characters Betty and Veronica, She-Hulk and Wonder Woman, comedienne Rosie O'Donnell and Disney's Sleeping Beauty. There is also now a multitude of examples of Covid-19/Corona Rosies wearing pandemic face masks, specifically representing female essential workers; also images of the original Rosie poster with Rosie's red polka dot scarf doubling as a face mask. Rosie is also appropriated as a character in children's books, for example, Rosie Revere, Engineer by Angela Beaty (2013) and R Is For Rosie The Riveter, Working Women On The Home Front in World War II by Frances Tunell Carter and Nell Carter Brenum (2014). There is a Rosie Lego figurine and a variety of dolls (porcelain, paper cut-out and bobble-headed), as well as a poster with space for a face to be inserted, inviting one to 'Rosify Yourself!'. Clad in a nurse's uniform, playing on the Florence Nightingale trope, she is used as a reminder that 'health care is a human right' and, in another version, she is part of the call for solidarity among the wives of American Marines ('Proud Marine Wives'). Rosie also vacillates between, among others, the status of a burlesque pin-up, a drag show staple persona, tattoo art, a Halloween costume, a fashion statement, and a consumer vehicle for anything from doggie treats to bed linen, and from washing powder to vacuum cleaners. The appropriation of Rosie for western consumer home-making culture is especially significant and ironic, as I explain later. Other interesting variations on the image, with clear counter-hegemonic intentions, include a male version, with a bearded man holding a baby and dusting brush, declaring '[h]e can do it' and several Rosies representing non-Caucasian racial groupings and non-Christian religions (a Rosie image with the woman wearing a burka can be found on the internet).

In one example from the internet, Rosie is used as the face of a breast cancer awareness campaign, supported by the slogan 'fight like a girl'. The latter is a tenuous connection at best, probably based on the idea of endurance in the face of adversity, inner psychological warfare in the familiar rhetoric of "a battle with cancer" (and also "the battle of the sexes"), and the "positive thinking" rhetoric of popular psychology. The intent is clearly counter-discursive and counter-hegemonic, but the effect is ironic for a couple of reasons. First, because the attitudinal value of "girl fight" is loaded with connotations of weakness and relational violence, rather than strength (Dellasega 2005). Relational violence is viewed as a quintessential "female" fighting strategy, as opposed to typical "male" physical violence. The entrenchment of such binary oppositions is not productive for the advancement of radical new ways of thinking. Think, for example, of the connotations attached to a girl - or a boy - on a sports field being told "you play like a girl". The 2016 gendered unequal pay controversy in world championship tennis is a clear example of this, suggesting that many still view women's activities and exertions as inferior to those of men (see BBC News 2016). Second, the appropriation of Rosie for the 'fight like a girl' cancer campaign is ironic and counter-productive, since the original wartime Rosie did not fight, either in combat or for women's rights, but exclusively functioned in a patriotic-nationalist and corporate ideological context, and by extension as a place-holder - at home and at work - for male soldiers. She was only retrospectively appropriated for feminism during the second wave of feminism in the 1980s (Sharp & Wade 2011). Using Rosie as a champion for women's fight against breast cancer brings together physical femaleness, implied by breasts, though men have them too and can also develop breast cancer; feminism, implying women's rights to equality with men; and femininity, the conventional and socially-constructed roles and rules associated with women (Zimbardo 2007). All these connotations are significant in understanding the complex (dys)functionality of the Rosie image. This becomes clear if one asks how would it be perceived if one told a man with testicular or prostate (or breast) cancer to 'fight like a girl'? The differentiated discursive effect is a signal that something is amiss in the appropriation of this image for certain messages and thus calls for a re-contextualisation of Rosie before indiscriminately reappropriating or "reinventing" her.

Another example from the internet provides an interesting illustration of both inter-and sub-textuality. An original World War II poster depicts a drawing of a recognisable Rosie with headscarf, worker's gloves and wrench in hand, looking over her shoulder and away from the viewer toward the image of a soldier on the battlefield (depicted in a dream/memorial-like cloud), stating, '[t]he girl he left behind is still behind him - she's a WOW' (Woman Ordinance Worker). A modernised version of the same poster (without headscarf, tools or recognisable context) presents a photograph of a smiling woman, passively sitting in a generic outdoor environment, this time facing the viewer directly, but suggesting eye contact with an implied person in the space just off camera. The text, presented in similar typographical layout as the previous poster and functioning as the link between the two images, states, '[m]odern day Rosies - still doing our part - she's a Riveter'. Despite the differences in posture (looking away and facing the viewer), the move away from discernible activity in the original poster to passivity in the later version, accompanied by the shift from the pronoun 'she' in the original (implying objectified, even heroic or idolised, activity) to 'our' in the modern version (implying communal, internalised passivity) are important changes in the visual and linguistic coding of Rosie-messages across three generations (the war generation, the second wave generation and the post-millennial generation). The original poster presents a contextualised Rosie - the context of the Second World War, industrial work and nationalistic patriotism is implied - while the latter presents a woman who is merely pretty, with no overt clues to why she is 'a Riveter' or what being a riveter is supposed to signify. Without the first poster to provide context, the latter is rendered meaningless and empty.

Similarly, Jennifer Siebel Newsom's 2012 Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN) documentary, Miss Representation (ironically subtitled You Can't Be What You Can't See) is a critique of popular representations of women in American media, 'portraying women's primary values as their youth, beauty and sexuality - rather than their capacity as leaders' (Oprah.com [Sa]). It utilises the Rosie image in its film poster and DVD cover footage, yet, incongruously, never engages with the image of Rosie in the film itself, though the fate of women in industry after World War II is briefly mentioned. A search of the internet also soon delivers what is probably a very accurate articulation of contemporary and post-millennial iconographical praxis: the original wartime '[w]e can do it!' Rosie poster, with a blurb bubble above Rosie's head stating, '[y]our text here!'. Having become an empty signifier, the image of Rosie at the same time contains the potential for any appropriation or inscription of meaning.

Postfeminism and feminist backlash

Rosie iconography, as I have argued, is not necessarily, and has never been, constitutive of a feminist agenda. "A feminist agenda", of course, does not itself constitute an unproblematically monolithic or univocal conceptual construct. In fact, exactly the opposite is true, especially in the current era of what is often called "post-millennialism", or, the third - sometimes even the fourth - wave of feminism (some have even referred to it as "postfeminism", although this is a highly contested term). In full acknowledgement of the multiplicity of feminist experience, praxis and theory, I argue that Rosie the Riveter is both a site for genealogical excavation and an example of how 'girls have become the new poster boy for neoliberal dreams of winning, and "just doing it" against all odds' (Ringrose 2007:484). Viewed as such, Rosie - the long-accepted icon of working women - is indeed today a neoliberal chimera and, arguably, 'patriarchy's Trojan horse' (Davies et al. 2017:2,4).

Rosie has arguably also, at least in some instances, been appropriated as part of the popular backlash against feminism, of which Susan Faludi warned in her 1991 book Backlash. Likewise, she is also seen as part of what is often loosely called postfeminism - a conceptual construct that is defined by Angela McRobbie (2004a; 2007) as 'feminism dismantling itself' and as 'an active process by which feminist gains of the 1970s and 80s come to be undermined ... elements of popular culture [that] are perniciously effective in regard to this undoing of feminism, while simultaneously appearing to be engaging in a well-informed and even well-intended response to feminism' (McRobbie 2004a:255). Seminal feminist critical theorists, Judith Butler (2005) and Chandra Mohanty (2002), have both, along with many others, identified the waning of sexual politics, feminism and the women's movement with the rise of global capitalism, consumer culture, women's involvement in the global labour market and a shift in global politics to the right (McRobbie 2007:719; Ringrose 2007:427), which is often associated with the neocolonialist aspect of neoliberalism (Rottenberg 2014:420). The "feminist paradox" thus emerges,

... whereby women support the general tenets of the movement but disassociate with the term 'feminist' and despite support for gender equality, some women reject the feminist label as a result of the negative connotations accompanying the term (Swirsky & Angelone 2016:445; see also Abowitz 2008 and Leaper & Arias 2011).

McRobbie (2004a:256) describes this as 'a form of Gramscian common sense' - the simultaneous identification and repudiation of feminism, thus dismantling possibilities for feminist politics and its much-needed renewed discourses. It is a space of neoliberal subjectification par excellence, where contexts constitute subjects and subjects constitute contexts in the perpetual motion of representation and iteration. Jessalyn Keller and Jessica Ringrose (2015:1) define this type of neoliberal feminism as,

[a] version of feminism [that] recognises current inequalities between men and women yet disavows the social, cultural and economic roots of these inequalities in favour of the neoliberal ethos of individual action, personal responsibility, and unencumbered choice as the best strategy to produce gender equality.

McRobbie identifies 'a new social contract' (2007:718) as pivotal to western post-feminism, where feminism is perceived as 'no longer needed' (McRobbie 2007:256) and is caught in a 'double entanglement', comprising 'the co-existence of neo-conservative values in relation to gender, sexuality and family life ... with processes of liberalisation in regard to choice and diversity in domestic, sexual and kinship relations' (McRobbie 2007:255). According to McRobbie (2007:718), this new postfeminist social contract rests on four silent agreements. The first is 'the guise of equality', which is assumed to have been achieved by second wave feminism through the seeming standardisation and normalisation of equality in legislative and civic spaces, and through systems such as gender mainstreaming and the institutionalisation of equity through policies and quotas (McRobbie 2007:718). The second silent agreement is consumer culture's 'postfeminist masquerade where the fashion and beauty system appears to displace traditional modes of patriarchal authority' (McRobbie 2007:718). The third is the emergence of the 'phallic girl' or 'ladette', to use British terminology, who 'appears to have gained access to sexual freedoms previously the preserve of men' (McRobbie 2007:718). The fourth agreement is the construction of idealised '"top girls" in education and employment, understood to be the subjects of female success, exemplars of the new competitive meritocracy' (McRobbie 2007:718; see also Ringrose 2007). This creates new categories and expectations of gender(ed) performance in which, as Jessica Ringrose (2007:474, following Walkerdine 2005) explains, 'both feminine and masculine qualities are to somehow be juggled [by top/successful girls/women], creating massive contradictions for girls'. The so-called 'mama grizzlies' (Ha 2017:834; Schreiber 2017:480) of the new American conservative politics is an example of a mature version of this "top girl" phenomenon, where the combination of conventional masculinity and femininity in the gender(ed) performance of female excellence has become ubiquitous. Another example is Facebook executive Sheryl Sandberg's (2013) memoir/self-help bestseller, Lean In, aimed at women in the corporate world (Rottenberg 2015). McRobbie (2007:718) further says about the "top girl" phenomenon,

[t]he new 'career girl' in the affluent west finds her counterpart, the 'global girl' factory worker, in the rapidly developing factory system of the so-called Third World. Underpinning this attribution of capacity and the seeming gaining of freedoms is the requirement that the critique of hegemonic masculinity associated with feminism and the women's movement is abandoned. The sexual contract now embedded in political discourse and in popular culture permits the renewed institutionalisation of gender inequality and the re-stabilisation of gender hierarchy by means of generational-specific address which interpellates young women as subjects of capacity. With government now taking it upon themselves to look after the young woman, so that she is seemingly well-cared for, this is also an economic rationality which envisages young women as endlessly working on a perfectible self, for whom there can be no space in the busy course of the working day for renewed feminist politics.

This continual pseudo-feminist representational politics and economics of self-perfecting and self-surveillance is (all)consuming work in terms of time and energy, often reliant on contradictory discourses of power, choice and sexuality, that are centred around "having" or "getting" imperatives rather than those of Heideggerian Dasein-driven "being" or "belonging" (implying that being human is necessarily always also already a state of unitary [wholeness] and holistic being-in-the-world).

As neo-feminists situated within popular cyber culture, bloggists Holly Baxter and Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett argue in The Vagenda (2015) that sexualised femininity and the indiscriminate appropriation of feminist discourses (also known as "girl power") can manifest as a baseline for anti-feminist or even misogynist backlash discourses, such as those contained in "lad culture", or what Kitty Nichols (2016:73) also calls 'mischievous masculinities'. These are not exclusively performed by men, but are also often symbiotically appropriated by women through socialisation and media representation. As Baxter and Cosslett argue (also see Francis 1999; Edwards 2006; Gill 2008; Nichols 2016), stereotypical post-millennial lad culture - a specific masculine embodiment, enactment or trend of patriarchy - is a complex occurrence, like "girl power" and "top girls", at the intersecting nexus created by consumer ethics, women's magazines, men's magazines, advertising culture, feminist discourse, popular music, social networking and the internet. McRobbie (2007:719) aptly quotes Foucault (1984) as saying 'it is quite clear that the danger has changed'.

Examples of "original" girl power popular discourses can, for example, be found in the turn-of-the-millennium pop music of the Spice Girls and Pussycat Dolls, which is re-emerging in a different guise in the work of recent popular singers such as Beyoncé, who has a very large female pre-teen following. In commenting on pop singers such as Beyonce's commodified and highly sexualised girl power rhetoric (the word feminism is often specifically reclaimed by the new wave of post-millennial celebrity feminists), often aimed at prepubescent and very impressionable young audiences, fellow-singer and humanitarian activist Annie Lennox distinguishes between "feminism lite" and "feminism heavy" as two ends of a scale. At the "heavy" end of the scale, she situates feminists such as Eve Ensler as 'very impactful feminists who have dedicated their lives to the movement of liberating women, supporting women at the grass roots' (Leight 2014). At the "lite" end of the scale she identifies sexualised, corporate and consumerist girl power music, 'I find it disturbing and I think it's exploitative. It's troubling ... Twerking is not feminism ... it's not liberating, it's not empowering. It's a sexual thing that you're doing on a stage; it doesn't empower you' (Lennox 2014; see also Azzopardi 2014; Leight 2014; Weidhase 2015).

Lifestyle feminism

Feminism lite, or as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls it, 'conditional female equality' (Brockes 2017), can also be associated with what is called 'lifestyle feminism', 'neoliberal feminism', 'choice feminism', 'free market feminism' or 'celebrity feminism' (McRobbie 2004b; Ringrose 2007; Eisenstein 2009; Fraser 2013; Hatton and Trautner 2013; Gay 2014; Valenti 2014; Keller & Ringrose 2015). These all signify the hollowness and neo-voyeuristic aspect of much of post-millennial "feminist" discourse and its agendas. Rosalind Gill (2011:63), following Robert Goldman (1992), calls it 'commodity feminism', describing 'the ways in which advertisers [seek] to appropriate and harness the cultural energy of feminism and sell it back to women, emptied of its political content'. Roxane Gay (2014) writes,

[i]t frustrates me that the very idea of women enjoying the same inalienable rights as men is so unappealing that we require - even demand - that the person asking for these rights must embody the standards we're supposedly trying to challenge. That we require brand ambassadors and celebrity endorsement to make the world a more equitable place is infuriating.

This produces a new objectification of the female as something to be looked at only in terms of the concept of "success", or its lack, which would signify "failure". Thus, it arguably creates a new form of abjection (following Julia Kristeva's concept of the abject as horrific), namely an unattainable and idealised, even idolised body (of beauty and success), which is simultaneously both obsessively sought-after and reviled, but which also serves to distract the attention from other(ed)/alternative ("failed") bodies and embodiments and other ways of seeing and being. Brigid Delaney (2017) says about lifestyle feminism, '[i]t's also a movement that empowers individuals often at the expense of the collective. The result is a blend of capitalism and feminism that feeds successful women into a patriarchal power structure of money, comfort and privilege but does not do much to improve the lives of many women who still live with capitalism's boot on their neck'. That women are often deeply implicated and complicit in this patriarchal power structure, both exploiting and benefitting from it, cannot be ignored. Jessa Crispin, an Australian author who distances herself from this kind of feminism, says in a conversation with Delaney (2017),

[t]here is very little sense of solidarity [in/about lifestyle feminism]. You use feminism to ask for a raise at work, or negotiate your romantic relationships - but you don't use it to negotiate the shared experience that minorities have or to renegotiate capitalism. There is less of an understanding of the big picture and more instead of how you are doing as an individual ... Feminism has become a way of shielding your choices from questioning. This is part of choice feminism; I call myself a feminist and I'm making a choice so therefore the choice is feminist. And that's absurd.

Elsewhere, Crispin (Cooke 2017) says about lifestyle feminism (what Cooke [2017] calls 'this self-obsession and ideological laziness'), 'it is about individualism, and self-achievement. It's about pop stars and television and narcissism. It's not about subsidised childcare, or institutional and structural social change. It's meaningless' and 'not getting what you want is not, by any stretch of the imagination, oppression'. Similarly, Rosie images associated with this kind of "feminism" can be seen as meaningless.

Feminist heterotopology

Foucault (1984:4) describes contemporary heterotopic experience - generated in part by living in different ideological spaces at the same time - as 'a sort of mixed, joint experience' and as mirror-like. This resonates with McRobbie's (2004a:255) 'double entanglement' of contemporary women, who are discursively often constructed as eternal 'girls', designating them to a type of perpetual adolescence, a ritualised and often pseudo-sacred liminal space of self-constitution and self-contestation. One invariably thinks of the two ironic lead characters, Edina and Patsy (played by Jennifer Saunders and Joana Lumley), in the British television series Absolutely Fabulous (1992-1996) as examples of these "stuck old girls" (with literal emphasis on each word); postfeminist veterans, so to speak, and an extreme example of flipped laddish behaviour and self-obsession. Their younger alter egos can be found in the female characters of popular Anglo-American millennial films and television series such as Sex and the City (1998-2004), Ally McBeal (1997-2002), Bridget Jones's Diary (Maguire 2001), Friends (1994-2004) and Will and Grace (1998-2006).

Foucault (1984:4) argues that heterotopic experience is 'a sort of simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live'. As he goes on to explain, experiencing such disparate spaces can lead to 'ideological conflicts' (Foucault 1984:1) and heterotopic anxiety (Danaher, Schirato & Webb 2002:113): an experience that is intensified today by the complex simultaneous mediation of a variety of networks of communication technologies. Manuel Castells (2012) describes social media and social movements in contemporary societies as paradoxically being simultaneous 'networks of [both] outrage and hope'. It is also, following Foucauldian logic, a site for both productive/constructive and de(con)structive power; the effects are determined by the use of social media. As McRobbie (2004a:258) says, '[the media] casts judgement and establishes the rules of play'. Heterotopia can offer freedom from patriarchal restrictions but can equally reinforce these restrictions. This has wide-ranging implications for the ways in which female subjectivities and desires (and the objects of this desire) are constructed and commodified within contemporary western neo-liberal consumerist cultures. The result is contradictory discourses and representational politics of feminine success (girl power and girls having it all), which are, as Ringrose (2007:482) points out, 'both wildly celebratory and deeply anxiety ridden'.

In keeping with Foucauldian ideas on heterotopic engagement, Castells (2012) explains that in networked societies symbolic spaces are transformed into public spaces, which then become political spaces. Certainly, this is not new and has always been part of human relationship management. However, the unprecedented variety, simultaneity, immediacy and intensity of these transformations are unique to contemporary technology-driven societies (virtual and real). This calls for continuous vigilance and what Foucault (1983) (cited by Rabinow & Dreyfus 1983:232) calls 'pessimistic activism'. He says 'it is not that everything is bad, but that everything is dangerous ... If everything is dangerous then we always have something to do. So my position leads not to apathy, but to a hyper- and pessimistic activism' (Foucault cited by Rabinow & Dreyfus 1983:232). Ringrose (2007:474, following McRobbie 2004a) also points out the need to remain vigilant about how some feminist discourse can feed into neoliberal formulas and fantasies of girls as 'metaphors for educational [and by implication workplace] success and equality'. This kind of vigilance stands in opposition to the pop culture Zeitgeist term 'slacktivism', which describes 'a virtual relatively costless display of token support with brief shows of public support of a cause via Facebook or online petition signing' (Guillard 2016:611; Kristofferson et al. 2014:1149). Furthermore, Foucault (1984:1) says of heterotopic experience (writing presciently from the pre-millennial 1980s) that,

we are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed. We are at a moment, I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein.

He goes on to describe three kinds of heterotopic experiences that are ideologically constructed and negotiated by societies. These are: first, crisis heterotopias that are socially constructed places where people in crisis go; second, heterotopias of deviation, which are also socially constructed places but, in this instance, where individuals go who deviate from the norm; and third, heterotopias of compensation that are socially constructed ideological utopic ideal places. Of the latter, Foucault (1984:8) says that 'their role is to create a space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled'. In the next section, I apply Foucault's insights to images of Rosie the Riveter.

Rosie the Riveter as heterotopic site

Rosie the Riveter presents an example of how contemporary iconographic culture engages with all three of these spaces simultaneously. First, the image of Rosie is repeatedly utilised as a site of heterotopic crisis. During the Second World War, this was a nationalistic/patriotic crisis; during second wave feminism it was the crisis of women's rights, especially in workplaces; and more recently, in the post-millennial era, it is the joint crisis of personal choice at the nexus of consumerism, individualism and an illusory nostalgia. It is more accurate to speak of plural nostalgias, since one may argue that the critiques of postfeminism often contain within them a degree of nostalgia for certain kinds of seemingly less complex and layered second wave feminism, or feminist politics.

Rosie has also always been a site of heterotopic deviation and dissidence. During wartime, this manifested as women being employed in traditionally male jobs, and during the second wave, as women's rights and equality. For post-millennials, she has become a paradoxical site of both postfeminist and reactionary nostalgia, often superficial sexualised girl power discourses and anti-feminist backlash. Finally, Rosie has also always been a site of heterotopic compensation, symbolising a type of ideal or perfect woman. During the Second World War she was presented as both strong and capable in carrying a nation to victory on the home front (a direct descendant of the American "frontierswoman" and a female version of the icon of the cowboy in American mythology), while also "knowing her place" and playing all the assigned traditional feminine roles, thereby playing into the traditional heteronormative fantasies of domesticity, sexuality and nurturing. During the second wave feminist movement, with the anti-war sentiments of the Vietnam era rendering Rosie ineffective in her previous World War II iteration, she symbolised the feminist ideal of the working woman, equal and on par with her male colleagues - engaged in the battle of the sexes in employment and civic spaces. For the post-millennial generation, she has become a heterotopic site of compensatory commodified nostalgia and consumer culture, presenting a dehistoricised ideal of women, especially in relation to what McRobbie (2004a:257) calls 'top girls' and 'phallic girls', both eternally infantilised and sexualised in the linguistic coding of the word girls; '[neoliberal] subjects par excellence, and also subjects of excellence'.

In the 2012 film, A pervert's guide to ideology (Fiennes), controversial psychoanalytic philosopher Slavoj Zizek explains that 'when we think we escape ideology in our dreams, that is when we are in ideology' (emphasis added). Language and discourse, including visual imagery and iconography, present us with ideological dreamscapes through which human beings both reveal and conceal themselves at the same time and often simultaneously in more than one space (real, virtual, social, cultural, ideological, and so forth). Thus, ideology can be seen as the complex heterotopic playing field of our dreams and desires. Zizek (in Fiennes 2012) describes ideology as the distorting glasses through which we view the world. He says that critical engagement with ideology is like removing these glasses - always a painful experience, since, after all, 'we enjoy our ideology' (Fiennes 2012). Rosie is a powerfully ideological figure, having been mobilised through nearly a century in the service of contradictory ideological agendas.

Rosie in wartime and in the workplace

Throughout history, women have always been central to war efforts. Most often, certainly in the popular western imagination of the last two centuries, this role was constructed as fivefold. First, women provided inspiration and existential meaning for fighting, suggestive of participation in the protection of the nation state, and by extension the sanctity of the home and family. Nurturing associations relating to the mythical "motherland" abound in wartime rhetoric, as does the idea of women as incubators, breeders or producers of more fighters against a clearly identified common enemy. Second, women in wartime are depicted as providing essential home-front emergency and other support services, thus literally "keeping the home fires burning" and temporarily occupying spaces previously filled by men.1 Third, women in wartime are depicted in more direct battle-related nurturing and care-taking roles, such as nursing, a notoriously poor occupation until Florence Nightingale ("The Lady with the Lamp") revolutionised and popularised it during the Crimean War.2 Red Cross and other nursing recruitment posters from the two World Wars often carried messages such as 'Save his life and find your own 'Be ready for your war service', 'The comforter', and 'If I fail he dies .. .'.3 Fourth, it was seen as the duty of women at home to send uplifting messages in letters to their 'menfolk' on the battlefield, for personal morale-building as well as patriotic national morale and counter-interception purposes. War posters from the Second World War contain messages such as '[k]eep 'em smiling with letters from folks and friends' and '[b]e with him at every mail call'. The fifth traditional inspirational role women occupy in wartime is that of entertainer/ entertainment and/or sexualised diversion from the hardship of masculine combat and war.4

Coinciding with the emergence of new communication technologies at the turn of the twentieth century, "entertaining the troops" was seen as the patriotic duty of popular film and radio personalities during both World Wars (both at the front and at a distance, from radio at the home front, and from recording studios and film locations). Morale building, closely related to propaganda in wartime, is a central part of any war effort and mainstream examples from Rosie's era are the uniform-clad Andrews Sisters (producing up-beat dance songs with a lot of sexual innuendo), Vera Lynn (called "The Forces' Sweetheart" and best known for nostalgic songs of loss and longing), and the androgynous Marlene Dietrich, whose haunting versions of Lili Marlene in both German and English are iconic of the pathos of war. Invariably, as counter-point, (unenlisted) male entertainers like Bob Hope supplied comic relief, while their female counterparts supplied nostalgic inspiration and sexualised distraction. The film, For the Boys (Rydell 1991), starring Bette Midler and James Caan, memorably depicts the evolution of this USO-style (United Service Organisation Inc) "entertaining the troops" tradition from the Second World War to the Vietnam War.

A related staple role for women during wartime is that of pin-up model. One of the most famous series of images of Marilyn Monroe shows her in a sequin-dress entertaining the American troops in this style in 1954 during the Korean War. Monroe was a 'Rosie' during the Second World War - she worked as a factory worker in the aeroplane industry before breaking into the entertainment industry after the war. Photos of her as Norma Jean Dougherty, taken in 1944 by army photographer David Conover (Collman 2013), show her in what has become the quintessential Rosie-pose, assembling an early version of what we today call drone planes. In a complex ideological combination of military aerial identification strategy, nostalgic patriotic affection, wistful sexualised ideation, hommage to femininity, and militaristic pornography, Second World War bomber aircraft (which, ironically, women were building in factories "back at home") were painted with pin-up pictures of women in provocative poses, in the style of the famous photograph of Betty Grable in a bathing costume looking back over her shoulder.5

These sexualised pin-up-style images have become a staple of the complex contemporary vintage and burlesque revival genres, with strong links to classical and Victorian parody and caricature, like the Vaudeville tradition. These images have re-emerged, like Rosie and often as Rosie, in the post-millennial era amid an unprecedented boom in communications technology. They form part of both the backlash against feminism and the re-imagining of gender and sex roles (also in drag and queer counter-cultures, some of which are contentiously claimed as feminist discourses). Simultaneously inscribed with the meanings of the complex and varied roles women occupy during wartime, Rosie has become a vehicle for self-conscious gender(ed) performance: women (and sometimes men) purposefully enact or depict gender(ed) Rosie-style roles and adapt these roles to suit different situations.6 This not only portrays an increasing awareness, mainstreaming and popularisation of the Butlerian idea of gender performativity, but also indicates the presence of Foucauldian ideological heterotopias, as well as the lenses of ideological distortion, to use Zizek's phraseology. These references to Rosie are often subliminal, making their ideological force stronger.

The industrialisation of the nineteenth century, including printing and communication technologies, not only advanced the capacity of the military war machine to staggering levels, but also aided the communication of nationalistic patriotism in ways that were unimaginable in earlier centuries. This also coincided with what is now called the first wave of feminism, which campaigned for women's suffrage and rights. The 2015 film, Suffragette (Gavron), based on Emmeline Pankhurst's autobiography, My own story, published in the first year of the First World War, provides a media-saturated generation with visual images and a coherent narrative to reimagine the revolutionary history of a previous generation. The suffragettes' struggle took place against the backdrop of increasing activism for women's rights within the textile industry. During wartime (in both World Wars), many of these factories turned to the manufacturing of weapons, bombs, tanks and aeroplanes, in addition to supplying uniforms and related equipment.

In the US, during the First World War, the now iconically famous picture of Uncle Sam (with Kitchener being the British equivalent) was augmented with wartime posters aimed at women. In the Uncle Sam poster, men are told, 'I want you for US Army' [sic]. Posters aimed at women stated, for example, 'Gee, I wish I were a man; I'd join the navy' (with a picture of a coy, wind-swept woman in a sailor's hat and navy uniform); 'Hello, this is Liberty speaking - billions of dollars are needed and needed now' (with a picture of a woman with a Statue of Liberty-headdress speaking into a telephone); and 'Joan of Arc saved France - Women of America save your country - Buy war savings stamps' (with an armour-clad woman wielding a sword, while casting her eyes up to heaven). Ironically, the contradictory fact that both Marianne (the emancipatory figure of the French Revolution, closely associated with "Liberty") and Joan of Arc were leading armies of revolutionaries to their death on the battlefield seem to be superfluous and inconvenient information in these patriotic images. Neither of them was spending or saving money as part of the home front war effort, as implied in the poster's message: they were engaged in active combat. The irony here is that the posters encourage economic frugality and austerity as the domain of (warring) women, whereas similar posters aimed at men would have emphasised recruitment to the battlefield.

A famous British poster of the time shows two women and a child clutching each other and their clothing while peering out of a window at a darkening sky and uniformclad, bayonet-wielding troops marching away to the front; the text simply states, '[w]omen of Britain say - Go!'. The gap left behind by the nearly three million British men called to combat (Crang 2000:144) - and death - were filled by the women "left behind". More than 350,000 men from Britain alone died in the war; the total Allied deaths amount to over 9,000,000 (The National WWII Museum [Sa]). A British poster of the time shows a smiling woman, with aeroplanes flying overhead as a factory and tank emerges from behind her skirt. The poster's text reads, 'Women of Britain -Come into the factories'. Another shows two women in nondescript brown and blue uniforms, with corresponding silhouettes of two men, one with a combat helmet and the other with aeroplane microphone-headgear, and text declaring, '[e]very woman not doing vital work is needed now'. It does not define 'vital work'; by implication, this would be "men's work", leading to the illogical assumption that non-essential work is all the work that women usually do. Two decades later the same patriotic iconography was repeated on both sides of the Atlantic. The emergence and use of these posters contextualise Rosie's appropriation and reinvention.

Can the real Rosie please stand up?

As I have shown, there are a multitude of variations on the themes and images associated with Rosie. The last three images that I describe form a trio of seminal iconographic and ideological meaning-making that shows - at least in part - the evolution of the central character of this paper and the intersecting early twentieth century discourses about women and war and women in the workforce. The first image is a pencil drawing depicting two women in similar postures; the first, in the upper left-hand corner, portrays a pioneer woman in bonnet and hoop skirt busy loading a rifle, while the second, in the lower right-hand corner, is the same image of the same woman, but in factory overalls with a red polka-dot headscarf and red manicured nails, busy riveting what most likely is a piece of fuselage from an aeroplane. The accompanying text reads, '[i]t's a tradition with us, Mister!'7

The second image is the original poster of the first so-called 'Rosie', emblem of the blue-collar working woman - the much-reproduced image of a woman with balled fist, in overalls and polka-dot headscarf, rolling up her sleeve while flexing her bicep and declaring, '[w]e can do it!'. In fact, she is not here identified as either 'Rosie' or a riveter and would not have been recognised as either by the viewers of her own time (Sharp & Wade 2011:82). Some claim that the image is of a 17-year old factory worker, Geraldine Hoff Doyle, while others argue that it is Naomi Parker (Kimble 2016:245). If these claims are true, this would be one of a series of corporate public relations posters created in 1942 by J. Howard Miller for the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company's War Production Coordinating Committee, who did not employ riveters (Sharp & Wade 2011:82-83). The poster was not widely published at the time; it was displayed for only two weeks8 and was used by the commissioning company for their own internal marketing purposes against unionism and in favour of corporate compliance (Sharp & Wade 2011:83). Thus, ironically, and in hindsight, the poster symbolises patriotic nationalism, corporatisation and control rather than dissidence, individualism or feminist communalism. The 'we' in the slogan refers to 'the company' and not to 'women'. The poster was therefore not intended as a rallying call to feminist solidarity, but was part of a series of visual communications addressed to all company employees. This is more in the Orwellian vein of Big Brother's doublespeak than that of Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan.

The poster re-emerged during the 1980s as part of the second wave feminist movement in the US (Sharp & Wade 2011), in what Anna Wiederhold and Kimberley Field-Springer (2015:147) would call a 'productive misreading'. As Sharp and Wade (2011:82, following Kimble and Olson 2006) explain, 'the idea that the poster was an inspirational call to other women is the result of reading history through the lens of our current assumptions about gender and politics ... Rosie, then, isn't calling out to women to join her in working at the plant, as [US] national mythology suggests; she's speaking to workers already employed there'. Thus, as Sharp and Wade (2011:83) explain,

[p]lacing the [Rosie] poster in its original context illustrates the way in which historical myth-making has obscured its real role. Ironically, the iconic image that we now imagine as an early example of girl-power marketing served not to empower women to leave the domestic sphere and join the paid workforce, but to contain labour unrest and discourage the growth of the labour movement.

The third image (and the source of the name Rosie) is a Norman Rockwell painting, published on the cover of the May 1943 Memorial Day edition of the Saturday Evening Post, which depicts a red-haired female riveter on lunch break, sandwich in hand, with a rivet gun in her lap, her lunchbox resting on her thigh and the American flag as backdrop. The name 'Rosie' is inscribed on the lunchbox. The image is reminiscent of the iconic Depression-era photographs of male construction workers on sky-scraper scaffolding against the backdrop of cityscapes and distant horizons - images speaking to a generation of disempowered and feminised men (Armengol 2014). The model for Rockwell's Rosie was a 19-year old telephone operator named Mary Doyle and the image was styled according to a part of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel paintings of the prophet Isaiah. In Rockwell's painting, Hitler's Mein Kampf can be seen on the floor under Rosie's foot - a symbol of the Allied victory over Nazi Germany (Fischer 2005). The US Treasury department used this image for patriotic war bond drives until the end of the war in Europe in 1945, after which it disappeared into American history owing to copyright regulations. At the time, the image coincided with a song written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb, performed by The Four Vagabonds (which probably inspired Rockwell), called Rosie the Riveter, with the following lyrics:

All the day long

Whether rain or shine

She's a part of the assembly line

She's making history, working for victory

Rosie, brrrrrrrrrrr, the Riveter

Keeps a sharp lookout for sabotage

Sitting up there on the fuselage

That little frail can do more than a male can do

Rosie, brrrrrrrrrrr, the Riveter

Rosie's got a boyfriend, Charlie

Charlie, he's a Marine

Rosie is protecting Charlie

Workin' overtime on the riveting machine ...

Oh, when they gave her a production 'E'

She was as proud as a girl could be

There's something true about, red, white, and blue about

Rosie the riveter gal (International Lyrics Playground [Sa]).

Despite the song and painting, it seems that the moniker 'Rosie the Riveter' was not widely used to refer to women factory workers during wartime, and only became popular when it was rediscovered and reinvented in the 1980s as part of the feminist workers' movement in the US, iconically represented by Sally Field in Norma Rae (Ritt 1979) and Charlize Theron in North Country (Caro 2005).9 Today there is a Rosie the Riveter Trust and World War II Home Front National Historical Park in California (Rosie the Riveter Trust [Sa]), and an American Rosie the Riveter Association (American Rosie the Riveter Association 2021). On the American Library of Congress website, Rosie is called 'the home-front equivalent of G.I. Joe' (Rosie the Riveter: Real Women Workers in World War II 2010). G.I. Joe is a military-styled post-Depression comic book action hero from the 1940s. He was reconfigured as a Hasbro action figure toy in 1964, nearly two decades after the end of the Second World War, but at the height of the US's involvement in Vietnam.

The image of Wonder Woman, a fictional DC Comics Justice League character, created in 1941, also makes for an interesting reading in relation to the Rosie iconography. Like Rosie, wartime Wonder Woman was re-appropriated by second wave feminists, spurred on by Gloria Steinem's placement of her on the 1972 front cover of Ms magazine. Like Rosie, Wonder Woman also experienced post-millennial reinvention through the 2017 and 2020 eponymous films (Jenkins 2017, 2020) and the recent Justice League films (Snyder 2016, 2017) and franchise. Wonder Woman, however, was presented as a superhero from her inception (she is Diana, an Amazon-princess, the secret daughter of Zeus and has supernatural powers). Neither the legend of Rosie nor her presentation includes superhuman qualities. Instead, Rosie is Everywoman. Wonder Woman, furthermore, occupies an escapist fantasy world, in typical comic book and graphic novel style, while Rosie originates from and is traditionally located in a factual context (historical wars and factory/industrial spaces). Wonder Woman is also loaded with (alternative) sexual politics, such as bondage, sadomasochism and polyamory, which originated in the real-life experiences of her creator, William Marston and his life partners.10 Rosie-imagery, on the other hand, is conventionally associated with more traditional and normative gender(ed) politics, although it does dabble in putting women into traditional men's roles.

Gender(ed) performance and the neoliberal retro/vintage trend

In her relationship to both the placement of women in wartime and in the workplace, Rosie today is situated in a Foucauldian (1984:4) heterotopic space, being a 'simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live'. She is also an example of how gender is enacted through ideological and discursive processes of both history- and myth-making. Sometimes the performance of gender is overt, intentional and systemically controlled - the most obvious example is propaganda, seen in many of the war posters mentioned earlier. However, more often gender performativity is depicted as unregulated, as exemplified in much of the self-construction that takes place in cyberspace and in social networking domains today. The technologies of self and the governmentalism of body, gender and identity politics are ever-present and interdependent, both in hegemonic and counter-discourses, which, in their turn, can become hegemonic as power shifts. Rosie is an example of this, with her origins in workplace institutionalism and compliance, and her reappropriation in second wave feminist discourses, while now 'helping to produce a [new/neoliberal] particular kind of feminist subject' (Rottenberg 2014:421).

Another ideologically complex version from the internet retains the original image of Rosie, but changes the words in the text bubble to 'I can do it!' - a comment on the shift from what is often perceived as traditional communally-centred feminist discourses (invoking the mythical sisterhood of women) to a discourse of typical neoliberal individualism and triumphalism. Yet another image shows the original Rosie poster picture with the text '[y]ou can do anything' - an open-ended statement in an era of an often debilitating array of options and choices about "what to do", often implying "how to be a good consumer". Catherine Rottenberg (2014:421, following Brown 2005 and Larner 2000) points to the entrepreneurial aspect of neoliberal discourses of self-creation and self-governmentalism; she says, referring to Wendy Larner,

[Collective forms of action or well-being are eroded, and a new regime of morality comes into being, one that links moral probity even more intimately to self-reliance, and efficiency, as well as to the individual's capacity to exercise his or her own autonomous choices. Most disturbing for Larner, however, is the way neoliberal governmentality undoes notions of social justice, while usurping concepts of citizenship by producing economic identities as the basis for political life ... There is no orientation beyond the self, which makes this form of feminism distinct ... thus effectively orient[ating] women away from conceptions of solidarity and towards their own particular development, which, to stay on 'track' as it were, requires constant self-monitoring.

Rottenberg's analysis is specifically focused on Sheryl Sandberg's Lean in, the 2013 bestseller self-help guide for corporate women. However, her observations also apply to my reading of post-feminist Rosie. This is paradoxically both far removed and closely related to the original, anti-unionist, non-feminist intent behind the first Rosie poster.

These two messages - 'I can do it' and '[y]ou can do anything' - can be read in different ways. They may be perceived as ironic self-referential comments on the complex internal politics of postfeminism; as a critique of the heteronormativity, classism and racial bias often claimed to be inherent in mainstream western feminism (where 'we' in the original 1940s message excluded more people than it included). Finally, it may be read as an ironic indication that despite the two waves of western feminism, women still face limitations that are systemically and structurally restrictive, even debilitating. These 'I' and 'you' messages can also be read as symptomatic of a reactionary shift in popular political consciousness, which coincides with the backlash theory. This further coincides with two significant forces in global culture and politics. The first of these is the post-millennial western mainstream "retro" fascination with postwar consumerist feminine paraphernalia and values. The second is the US's contentious involvement in wars in the Middle East during the millennial era. George W. Bush referred to US foreign policy in 2001 as a 'war on terrorism' (a term with its roots in the Reagan administration of the 1980s).

In relation to the "retro" consumer culture that is prevalent in the post-millennial era (remembering also that 2014 was the centennial of the First World War and 2015 marked 75 years since the end of the Second World War), the placement of women in relation to the discourses of both war and work are significant. As historian Barbara J. Berg (cited by Newsom 2014) explains,

[d]uring World War Two six million women were pulled in to take care of the factories in the absence of the men. By the time the war was coming to a close 80% wanted to stay at their jobs. When the returning GIs came home, within two days of the victory in the Pacific 800 000 women were fired from the aircraft industry and other companies began to follow suit. We needed a huge media campaign to get these women back into the home. One of the most effective ways to do this was through the television. So the television was part of the redomestication. We had television shows sponsored by numerous commodities - the gleaming commodities that June Cleaver would use in the kitchen; these commodities would be linked to the good life.

Thus, neoliberal economic consumption, cultural messages about what constitutes "the good life" and contemporary war rhetoric are inextricably interwoven with the rhetoric of gendered performance and millennial retro/vintage nostalgia. This bricolage of '1950s kitsch' femininity is, as Ulrika Dahl (2014:605) points out 'a white bourgeois fantasy of the past that was and remains far from universally available'. This presents 'a palatable and nostalgic 1950s version [of femininity], [but] remains racialized and, more importantly, links "high femininity" to histories of imperialism and nationalism', while also simultaneously implying a binary counter-point of 'rugged masculinist national pride' (Dahl 2014:609).

Conclusion

Ringrose (2007:477) sees postfeminism as 'complex representational terrain, temporal, political, theoretical (etc.)' where both backlash and destabilisation result. She says that 'postfeminism [is] a useful conceptual tool that helps in tracing the complex effects of and implications of various forms of feminism (like liberal and neoliberal feminism) over time in popular culture and beyond' (Ringrose 2007:477). This paper has explored how the diverse forces at work in postfeminism affect one icon of western popular culture, Rosie the Riveter. Today, this figure carries a multitude of significations and can be considered as a site of simultaneous collective, intergenerational and transgressive gendered messages, with the potential for continued future deployment as a vehicle to counteract the often exclusively self-centred aspirational turn of neoliberal feminist discourses. Rottenberg (2014:431) notes that,

even in the heyday of the feminist movement in the early 1970s, the call for self-transformation or self-empowerment was accompanied by some critique of systemic male domination and/or structural discrimination. Today, by contrast, the emergent feminism is contracting, shining its spotlight, as well as the onus of responsibility on each female subject while turning that subject even more intensively inward. As a result neoliberal feminism is - not surprisingly - purging itself of all elements that would orient it outwards, towards the public good.

To return to Zizek's (in Fiennes 2012) statement that 'when we think we escape ideology in our dreams, that is when we are in ideology' (my emphasis), I argue that reappropriations of the original image of Rosie the Riveter provide a case study of how our dreamscapes (including visual images and discourses) both reveal and conceal complex ideological placements, displacements and dissonances. Owing to communication network(ed) technology, these images and their multifarious iterations are communicated to a global audience that often lack historical or situational context for the images. Therefore, the images, in truly postmodern ways - having become empty or open signifiers - develop lives, contexts and networks of their own, transmuting themselves in and across social, political and symbolic spaces, creating heterotopic experiences of being in more than one ideological space at the same time.

Rosie, originating in corporate institutional discourse and nationalistic patriotism, is caught between the extremes of feminist expression, anchored in discourses of war and work, and has become 'a simulacrum of a life she had never lived and yet that also had resonance with her own life' (Dahl 2014:613). Used simultaneously as both an icon of women's empowerment (which was not the original intent) and as a symbol of nostalgic traditional gender(ed) values, the image of Rosie has become a commodity. She is an open discursive signifier, possibly dangerously so and in need of vigilance (in a Foucauldian sense); she is an unmoored ship adrift in a sea of ideological currents. In order for Rosie to reclaim her rightful place and value, both historical and ideological, she must first be reinstated in her original context, from whence she can be productively reappropriated for neo-feminist discourses and post-millennial women's empower- ment. As, in the first place, an example of how hegemonic discursive practices operate, and, secondly, of her own (dys)functional cross-generational appropriation, she can become active, useful and productive again - a reoperationalised vessel with a clear mission. We need to apply what Rottenberg (2014:433) calls for when she speaks of the need for 'a specific kind of internal critical gaze' in cultural and feminist analyses, and which Sue Morgan (2009:382) calls the 'internal debates and self-critical dialogue ... [of] ... reflexive feminist historiography ... [which is] ... a source of tremendous creativity, optimism and analytical momentum'.

Notes

1 . Home fires (2015-2016) is the title of a popular ITV series about women in Cheshire during the Second World War.

2 . Hana, played by Juliette Binoche in the award-winning film of Michael Ondaatje's Second World War novel The English patient (Minghella 1996) is a recent popular iteration, as are the London East End post-war nurses in the popular BBC television series Call the midwife (2012-2020), which is now in its tenth season.

3 . These slogans appear as results of a Google search for nursing recruitment posters during the two World Wars.

4 . Prostitution, of course, peaks during war, which in itself is a complex indicator of a variety of social and ideological factors relating to, among others, differentiated gendered roles, violence, destabilised social norms, coercion and shifting economic terrain. Likewise, the role of women in espionage and counterespionage is complex and is seen in, for example, the film Paradise in service (Doze 2014), which portrays the story of a Republic of China Armed Forces military brothel.

5 . The Memphis Belle was the most famous example of what is now called aircraft "nose art", depicted in the eponymous Alms of 1944 (a documentary) and 1990 (Action). As Cockburn (2003 cited by Wiederhold & Field-Springer 2015:151) states, patriarchy, nationalism and militarism often belong to 'a mutual admiration society' and 'a feminist theory of war must challenge not just patriarchy, but also nationalism and militarism'.

6 . That it coincides with the centennial of The Great War (World War I, 1914-1919) and the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War (1939-1945) is not insignificant.

7 . The American Library of Congress calls Rosie 'an example of a strong, competent foremother' (The Library of Congress [Sa]).

8 . The dates are seen on the original poster: 15-28 February 1943 (Sharp & Wade 2011:83).

9 . Norma Rae was pitched at the time of its production as a female Rocky - 'a realist-looking film about a poor [working class] underdog' (Toplin 2010:283). This film produced another iconic image, like Rosie, relating to women in the workplace, which is immortalised in the moment when Sally Field (playing Norma Rae, based on the true life story of Crystal Lee, an American textile mill worker) literally brings the noisy factory shop floor to a standstill as she holds up a placard with the word 'union'. Robert Toplin (2010:283) provides an account of the production dynamics of this film which combines unionism and feminism in its message 'in an era when unions were falling out of favour with the American public and politicians appeared eager to criticise organised labour for harming American competitiveness in the global marketplace' (Toplin 2010:282). The British women's worker movement of the time was depicted in a Broadway Musical and the 2010 film about the 1968 Ford Motor Company strikes, Made in Dagenheim (Cole).

10 . Depicted in the 2017 fictionalised biopic of his life, Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, directed by Angela Robinson.

REFERENCES

Abowitz, DA. 2008. The campus F word: feminist self-identification (and not) among undergraduates. International Journal of Sociology of the Family 34:43-63. [ Links ]

Absolutely Fabulous. 1992-1996. [Television Programme]. Saunders and French Productions. [ Links ]

Ally McBeal. 1997-2002. [Television programme]. 20th Century Fox. [ Links ]

American Rosie the Riveter Association. 2021. [O]. Available: http://rosietheriveter.net/ Accessed 13 May 2016. [ Links ]

Armengol, JM. 2014. Gendering the Great Depression: rethinking the male body in 1930s American culture and literature. Journal of Gender Studies 23(1):59-68. [ Links ]

Azzopardi, C. 2014. Q&A: Annie Lennox on her legacy, why Beyoncé is 'feminist lite'. [O]. Available: http://www.pridesource.com/article.html?article=68228. Accessed 26 May 2017. [ Links ]

Baxandall, RF, Gordon, L & Reverby, S (eds). 1976. America's working women. New York: Vintage. [ Links ]

Baxter, H & Cosslett, RL. 2015. The Vagenda. London: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

BBC News. 2016. Novak Djokovic questions equal prize money in tennis. [O]. Available: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-35859791. Accessed 16 May 2016. [ Links ]

Beaty, A. 2013. Rosie Revere, Engineer. Abrams Books for Young Readers. [ Links ]

Block, S (dir.). 2015-2016. Home fires. [Television series]. ITV Masterpiece. [ Links ]

Brockes, E. 2017. Interview with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: 'Can people please stop telling me feminism is hot?'. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/04/chimamanda-ngozi-adichie-stop-telling-me-feminism-hot. Accessed 22 May 2017. [ Links ]

Brown, W. 2005. Neo-liberalism and the end of liberal democracy. Theory & Event 7(1):37-59. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 1997. Excitable speech. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 2005. Undoing gender. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 2011a. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Butler, J. 2011b. Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of sex. Routledge Classics Series. Oxfordshire: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Call The midwife. 2012. [Television series]. BBC One. [ Links ]

Caro, N (dir.) 2005. North country. [Film]. Warner Bros. [ Links ]

Carter, FT & Brenum, NC. 2014. R is for Rosie the Riveter: Working women on the home front in World War II. Portland: Premier Press. [ Links ]

Castells, M. 2012. Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. New York: Wiley. [ Links ]

Caton-Jones, M (dir.). 1990. Memphis belle. [Film]. Warner Bros. [ Links ]

Cockburn, C. 2003. Why (and which) feminist antimilitarism? Invited talk at the annual general meeting of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. [O]. Available: http://www.cynthiacockburn.org/Blogfeministantimilitarism.org. Accessed 15 May 2017. [ Links ]

Cooke, R. 2017. Interview with Jessa Crispin: 'Today's feminists are bland, shallow, lazy'. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/23/jessa-crispin-todays-feminists-are-bland-shallow-and-lazy. Accessed 24 May 2017. [ Links ]

Cole, N (dir.). 2010. Made in Dagenheim. [Film]. Paramount Pictures. [ Links ]

Collman, A. 2013. Marilyn the Riveter: New photos show Norma Jean working at a military factory during the height of World War II. [O]. Available: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2380152/Marilyn-Monroe-photos-young-Norma-Jean-working-WWII-factory.html. Accessed 30 May 2017. [ Links ]

Crang, J. 2000. The British Army and the people's war, 1939-1945. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Dahl, U. 2014. White gloves, feminist fists: race, nation and the feeling of 'vintage' in femme movements. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 21(5):604-621. [ Links ]

Danaher, G, Schirato, T & Webb, J. 2002. Understanding Foucault. London: SAGE. [ Links ]

Davies, SG, McGregor, J, Pringle, J & Giddings, L. 2018. Rationalizing pay inequality: Women engineers, pervasive patriarchy and the neoliberal chimera. Journal of Gender Studies 27(6):623-636. [ Links ]

Delaney, B. 2017. Jessa Crispin: The woman at war with lifestyle feminism. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/03/jessa-crispin-the-woman-at-war-with-lifestyle-feminism. Accessed 22 May 2017. [ Links ]

Dellasega, C. 2005. Mean girls grown up: Adult women who are still queen bees, middle bees, and afraid-to-bees. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Edwards, T. 2006. Cultures of masculinity. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Eisenstein, H. 2009. Feminism seduced: How global elites use women's labor and ideas to exploit the world. Boulder, Colorado: Paradigm. [ Links ]

Evans, E. 2015. What makes a (third) wave? How and why the third-wave narrative works for contemporary feminists. International Feminist Journal of Politics 18(3):409-428. [ Links ]

Evans, R & Loeb, JJ. 1943. Rosie the Riveter. [Song]. Performed and recorded by The Four Vagabonds. Bluebird Music 300810A. RCA. [O]. Available: http://www.authentichistory.com/1939-1945/3-music/10-Pitching_In/19430200_Rosie_the_Riveter-The_Four_Vagabonds.html. Accessed 25 May 2017. [ Links ]

Faludi, S. 1991. Backlash. Danvers, Massacheusetts: Random House. [ Links ]

Fiennes, S (dir.). 2012. The pervert's guide to ideology. [Film]. Zeitgeist Films. [ Links ]

Fischer, DH. 2005. Liberty and freedom: A visual history of America's founding ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1983. On the genealogy of ethics: an overview of work in progress, in Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Second Edition, edited by HL Dreyfus & P Rabinow. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1986. Of other Spaces, translated by Jay Miskowiec (based on Des espaces autres lecture given in 1967, published in Architecture-Mouvement-Continuite, October, 1984). Diacritics 16(1):1-9. [ Links ]

Francis, B. 1999. Lads, lasses and (new) labour: 14-16-year-old students' responses to laddish behaviour and boys' underachievement debate. British Journal of Education 20:353-371. [ Links ]

Fraser, N. 2013. Fortunes of feminism: From state-managed capitalism to neoliberal crisis. London: Verso Books. [ Links ]

Friends. 1994-2004. [Television programme]. Warner Bros. Studios. [ Links ]

Gavron, S (dir). 2015. Suffragette. [Film]. Film4. [ Links ]

Gay, R. 2014. Emma Watson? Jennifer Lawrence? These aren't the feminists you're looking for. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/oct/10/-sp-jennifer-lawrence-emma-watson-feminists-celebrity. Accessed 22 May 2017. [ Links ]

Goldman, R. 1992. Reading ads socially. London and New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Gill, R. 2003. Power and the production of subjects: Genealogy of the new man and the new lad. The Sociological Review 51:34-56. [ Links ]

Gill, R. 2011. Sexism reloaded, or, it's time to get angry again! Feminist Media Studies 11(1):61-71. [ Links ]

Guillard, J. 2016. Is feminism trending? Pedagogical approaches to countering (Sl) activism. Gender and Education 28(5):609-626. [ Links ]

Ha, JS. 2017. Ronald Reagan in heels; constructing the Mama Grizzly political persona in the 2010 US elections. Journal of Gender Studies 27(7):834-846. [ Links ]

Hatton, E & Trautner, MN. 2013. Images of powerful women in the age of 'choice feminism'. Journal of Gender Studies 22(1):65-78. [ Links ]

Hooks, B. 2016. Moving beyond pain. [O]. Available: http://www.bellhooksinstitute.com/blog/2016/5/9/moving-beyond-pain. Accessed 5 May 2017. [ Links ]

International Lyrics Playground. [Sa]. Rosie the Riveter. [O]. Available: https://lyricsplayground.com/alpha/songs/r/rosietheriveter.html. Accessed 12 May 2017. [ Links ]

It's a tradition with us, mister! [sa] [O]. Available: https://digitalcollections.hoover.org/objects/40400/its-a-tradition-with-us-mister Accessed 27 April 2021. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P (dir). 2017. Wonder Woman. [Film]. Warner Bros Pictures. [ Links ]

Jenkins, P (dir). 2020. Wonder Woman 1984. [Film]. Warner Bros Pictures. [ Links ]

Keller, J & Ringrose, J. 2015. 'But then feminist goes out the window!': Exploring teenage girls' critical response to celebrity feminism. Celebrity Studies 6(1):132-135. [ Links ]

Kimble, JJ. 2016. Rosie's secret identity, or, how to debunk a woozle by walking backward through the forest of visual rhetoric. Rhetoric & Public Affairs 19(2):245-274. [ Links ]

Kimble, JJ & Olson, LC. 2006. Visual rhetoric representing Rosie the Riveter: Myth and misconception in J. Howard Miller's 'We Can Do It!' poster. Rhetoric & Public Affairs 9(4):533-569. [ Links ]

Kopp, DM. 2007. Rosie the Riveter: A training perspective. Human Resource Development Quarterly 18(4):589-597. [ Links ]

Kristofferson, K, White, K & Peloza, J. 2014. The nature of slacktivism: How the social observability of an initial act of token support affects subsequent prosocial action. Journal of Consumer Research 40(6):1149-1166. [ Links ]

Larner, W. 2000. Neo-liberalism: Policy, ideology, governmentality. Studies in Political Economy 63:5-25. [ Links ]

Leaper, C & Arias, DM. 2011. College women's feminist identity: A multidimensional analysis with implications for coping with sexism. Sex Roles 64:475-490. [ Links ]

Leight, E. 2014. Interview with Annie Lennox: Twerking is not feminism'. [O]. Available: http://www.billboard.com/articles/news/6289251/annie-lennox-twerking-not-feminism. Accessed 26 May 2017. [ Links ]

Lennox, A. 2014. 'You cannot go back': Annie Lennox on 'Nostalgia'. [O]. Available: http://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyld=357622310. Accessed 30 May 2017. [ Links ]

Maguire, S (dir). 2001. Bridget Jones's diary. [Film]. United International Pictures. [ Links ]

McRobbie, A. 2004a. Postfeminism and popular culture. Feminist Media Studies 4(3):255-264. [ Links ]

McRobbie, A. 2004b. Notes on postfeminism and popular culture: Bridget Jones and the new gender regime, in All about the girl: culture, power and identity, edited by A Harris. New York: Routledge:3-14. [ Links ]

McRobbie, A. 2007. Top girls? Cultural Studies 21(4):718-737. [ Links ]

Minghella, A (dir.) 1996. The English patient. Miramax. [ Links ]

Mohanty, CT. 2002. 'Under Western Eyes' revisited: feminist solidarity through anticapitalist struggles. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(2):499-535. [ Links ]

Morgan, S. 2009. Theorising feminist history: A thirty-year retrospective. Women's History Review 18(3):381-407. [ Links ]

Newsom, JS (dir). 2011. Miss Representation. [Film]. Girl's Club Entertainment. [ Links ]

Nichols, M (dir). 1983. Silkwood. [Film]. 20th Century Fox. [ Links ]

Nichols, K. 2016. Moving beyond ideas of laddism: Conceptualising 'mischievous masculinities' as a new way of understanding everyday sexism and gender relations. Journal of Gender Studies 27:73-85. [ Links ]

Ondaatje, M. 1992. The English patient. New York: Alfred A Knopf. [ Links ]

Oprah.com. [Sa]. OWN acquires Miss Representation for OWN's Documentary Film Club. [O]. Available: http://www.oprah.com/pressroom/ Accessed 13 May 2016. [ Links ]