Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.35 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2021/n35a5

ARTICLES

All that glitters is not gold: Counter penetrating in the name of Blackness and queerness, or, Athi-Patra Ruga's camp act in the dirt

Adéle Adendorff

School of the Arts, University of Pretoria, South Africa. adele.adendorff@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6820-8148)

ABSTRACT

In this article I engage South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga's artistic practice to flesh out the complexities that arise from the intersection of the terms Black and queer. Drawing on diverse historical, social and textual resources, I interpret Ruga's dismantling of dominant post-apartheid and postcolonial narratives vis-a-vis a close reading of some of his provocative avatars. Ruga's practices of staining, tainting and contaminating serve to expose the borders that produce conventional notions of race and gender. The article employs camp discourse in its allusion to performativity, displacement and artifice in order to 1) lay bare prevailing normative structures; and 2) dismantle conventional views of identity. To avoid being blindsided by camp's flamboyance and ostentation, I propose a view that favours an intimate embroilment with dirt - a stance I argue may furnish camp acts with political intent and so help create a more sophisticated and comprehensive view on the juncture of Blackness and queerness. Relying on Ruga's method of counter penetration as a way of fleshing out a hermeneutic view of Black queer subjectivity, I show how counter penetration in Ruga's estimation is a subversive and transgressive act intent on contaminating and infecting conventional narratives of history, identity and politics.

Keywords: Black queer identity, camp, Athi-Patra Ruga, performance.

Introduction

A cluster of colourful balloons atop a pair of cerise pink stockinged legs, propped up by red suede stilettos, slowly ambles through the dusty street. There is an air of anxiety mixed with celebration, echoed by the balloons and the dull sound of the crowd that saunters in tow. Taking great care to maintain balance and poise, the balloon character navigates the ebb and flow of the jagged terrain. The peculiar procession stirs memories of macabre funerary marches - something between the festive chimes of the Kaapse Klopse minstrel parade and the sounds of resistance from toyi toyi protests. The obscured figure squeaks and screeches as the bundled balloons press up against the wearer's body and passersby. The kaleidoscope of inflated vessels, taut and heavy with liquid rather than breath, swags from one side to the other, rhythmically echoing the bearer's pendulous sway. As the shrouded person continues on her path, the occasional burst balloon leaks her all over the landscape, reminding us of her burden, now too heavy to carry.

The obscure(d) character, The Future White Woman of Azania, is one of South African artist Athi-Patra Ruga's gender- and race-ambivalent avatars; the defiant protagonist of his The Future White Woman of Azania (2010-2016) saga (Figure 1). The series, comprising performances, photographs, sculptures and petit point tapestries, spins a fable of a mythical promised land, Azania, where Black queerness reigns supreme - a tale that 'counter penetrates' normative narratives of history and identity as Ruga (cited by Libsekal 2014:157) names his praxis. Azania, both fictional and real, is the name of an ancient society discovered under the soil of Mapungubwe in South Africa's Limpopo province. The legends and myths of Azania as a pre-colonial and untainted nation were resurrected in the 1960s as part of South Africa's 'liberation rhetoric' (Corrigall 2014:89). Similarly suspended between ideals for a liberated (South) Africa and counterfeit cultural artefacts, Ruga reimages Azania as a paradox of sorts. Corrigall (2014:91) notes,

[Ruga] offers a multiple reading of Azania as a utopian state hailing from the past, with references to the colonial or apartheid era, and a future place sustained by black consciousness ideology.

It is amidst the textuality and unclear margins in Ruga's Azania that the artist refracts the rainbow of post-apartheid through a prism of skepticism. There to aid him in his quest is a mob of no-nonsense protagonists - fabricated avatars through which I speculate about Black queer identity. I draw on historical, social and textual resources as a way to illuminate some of the issues that arise from the intersection of the terms "Black" and "queer". I filter an intertextual reading through Ruga's vivid characters, drawing on queer studies, cultural studies, identity politics, art history, anthropology and Black studies, to bring into focus complex and unabridged Black queer bodies. I take cognisance of Ruga's reliance on the camp act - both its aesthetic repertoire of flamboyance, decoration and glamour, and its performative gesture that paraphrases, appropriates and displaces. I argue that to offer a view of camp as a critical and engaged mode of interrogation, Ruga's exploitation of the outrageously beautiful should be navigated as part of his commitment to the threateningly objectionable abject. This hybrid act, which he channels through his strategy of counter penetration, offers a reading of complex and problematic relations that puts forward a view of Black queerness as liminal, manifold and intricate.

Eventually, she seems to reach her destination: a beautifully fashioned monument in the form of a fine-grained marble plinth topped with a towering female winged figure of peace, covering (for) a fallen soldier and presenting a wreath in her left hand. In stark contrast with the proposed divinity of the celestial being gazing out over the city square, the worn-out, soiled balloon-body ascends the steps of the monument. Pressing herself up against the cold slab, she rubs up against the past. Part struggle, part respite, she slowly comes into being as each balloon is slit open, its technicolour liquid pigment gurgling, staining, soiling and contaminating the off-white marble and the body of the, now visible, artist.

A political agenda for a darker shade of camp

The comingling of the terms Black and queer is not intended to delimit queer studies by offering a splinter group of racialised queerness. Michael Warner (1993:xxvi) rightly argues that queer studies necessitate an 'aggressive impulse of generalisation' while it rebuffs the 'minoritising logic of toleration'. In its seizing of numerous modalities of gender and sexuality that depart from the convention of white heterosexual masculine norms, queer studies yearn, instead, for a more comprehensive approach (Warner 1993:xxvi). Notwithstanding, I insist on the racial modifier here to offer a unique frame of reference for queer encounters and expressions as it transpires from the precarious and violent historical nuances that frame both race and gender in South Africa. In this way, to borrow from Kathryn Bond Stockton (2006:2), I 'cut a path through strained relations ... to see how "queer" and "black" touch upon each other's meaning'. Thus, Black queer subjectivity emphasises the various intersectional1 positions Ruga's art practice converges.

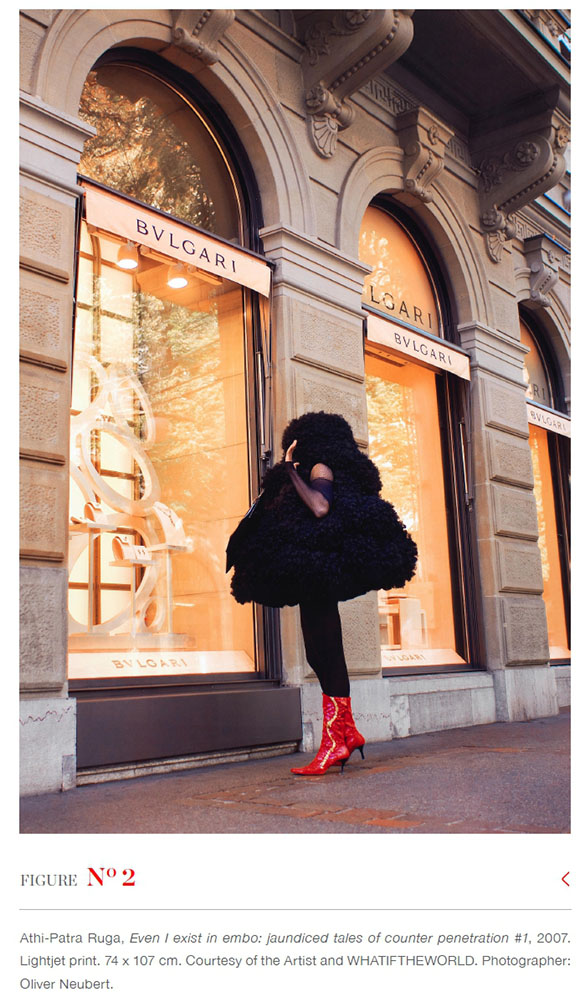

For Ruga (cited by Libsekal 2014:157), the term "counter penetration" is shorthand for his desire to (re)insert Blackness and queerness into spaces and narratives in a 'sexual' and 'transgressive' way. Inj'ibhabha, Ruga's avatar erected in Bern, is a shaggy concealed figure - both the 'black sheep and ... the dainty flaneur' that both seduces and disrupts (Buys 2009:22). Inj'ibhabha is an isiXhosa word that refers to traction alopecia (gradual hair loss) that typically results from pulling owing to wearing braids. Inj'ibhabha is a big bundle of synthetic afro-like hair - an 'afro-womble' - spotted in all the "right" Swiss places for all the "wrong" reasons. Inj'ibhabha is the 'figurative black sheep' that the xenophobic Swiss People's party attempted to expel at the time - 'a hairline fracture - present, sharp and unrelenting' (Libsekal 2014:158).

The use of the term counter penetration first appeared in the title of a series of work, Even I exist in embo - jaundiced tales of counter penetration (2007) (Figure 2), which featured Inj'ibhabha.2Since Inj'ibhabha gave birth to counter penetration as an act of deliberate and stubborn insertion of the self into unexpected spaces, this tactic has evolved to become an emboldened approach by the artist to constrain and negate homogenous and reductionist narratives.

To unpack the artist's strategy first requires an understanding of what may be implied by the kind of penetration that the artist wishes to oppose or negate. In broad terms, penetration connotes the forceful insertion of whiteness through colonial and apartheid strategies; the "rape" of Africa, her history and her people. Penetration also extends to patriarchal probing and heteronormative diffusion in social and cultural psyches

- both collectively and individually. It is this that Ruga's counter penetration desires to reverse, pervert and override. Taking as her backdrop post-apartheid multicultural South Africa, the avatar upends narratives of Blackness and queerness. As The Future White Woman of Azania navigates across the adjacent township en route to the Grahamstown festival terrain, the feeble promises of a forgotten Rainbow Nation are writ large. The apparent poverty and inequality impale township passersby too. At the same time, the colonial narrative remains poised, seemingly oblivious to its own malaise, on the shoulders of The winged figure further along the route. Ruga's counter penetration of the impoverished landscape - the balloon-body's magnificent obscurity in this dusty space - is not a way to bring his performance to the people; it is not the target of the counter penetrating gaze. Rather, as Andrew J. Brown (2017:71) remarks, The Future White Woman of Azania accentuates the 'stark differences in experience produced by this national celebration' and for those whom the incandescence of the rainbow is felt. She upends the colonial subjugation of Blackness by revealing its vast exploitation; she stains the marbled icons of its grandeur as the burst vessels infuse its proud history with shame.

Counter penetration in Ruga's estimation of defiance is the modus operandi of his fabricated avatars. Able to thread (mis)behaviour through Ruga's successive avatars, their ongoing counter penetration ultimately gives birth to The Future White Woman of Azania. For me, counter penetration is present in a long line of Ruga's alter egos, and most pronounced in Inj'ibhabha, Miss Congo, Beiruth, and ultimately, The Future White Woman of Azania. As I show, the goal of the artist's counter penetration is to infect, pollute and pass on dis-ease; it is a means to dislodge and debase postcolonial narratives, hegemonic structures, and the current status quo. Following Elizabeth Freeman's (2010:xi) explanation of 'counterpolitics of encounter', Ruga's body, 'decomposed' by the strategies of his artmaking, forges - in the sense of 'both making and counterfeiting - history differently'. The (de)composition Freeman mentions is the result of a lack of belonging - the anachronistic and starkly displaced avatars that pierce the "normativity" of everyday life.

Ruga's reliance on camp aesthetics and performance similarly offers creative avenues for surveying Black queer identity. Camp's allegiance with displacement, duality and aesthetics - its 'incongruent juxtaposition' to employ Esther Newton's (2000:103) label - makes it an ideal lens through which to consider Black queer subjects. Postcolonial discourse markedly subordinates queerness to race as a way to offer a 'unified front of racialised blackness' (Johnson & Henderson 2005:4). The privileging of racialised bodies over sexualised and gendered bodies also appears to give credence to 'sexist and homophobic rhetoric' (Johnson & Henderson 2005:4). E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (2005:4) explain in the introductory chapter to their edited text, Black queer studies: A critical anthology, that queerness, viewed as 'sexual deviance', is postulated as a 'white disease' that contaminates Blackness. It is this co-implication of the terms Black and queer that Ruga's practice problematises.

In The dark side of camp aesthetics: Queer economies of dirt, dust and patina, Ingrid Hotz-Davies, Georg Vogt and Franziska Bergmann (2018) insist on the recognition of the presence of dirt as central to the camp gesture. Here, blemishes are not seen as binaries or opposite poles of the 'flamboyantly pretty', but are rather immersed in it (Hotz-Davies et al. 2018:1). In this appraisal, the grimy side of camp, which I argue is a perspective that Ruga's performances offer, may be interpreted as 'material to be signed over to the dust-heap or the sewer' (Hotz-Davies et al. 2018:2). As a master craftsman with a background in fashion,3 Ruga's exploitation of the seductive allure and flamboyance of his avatars' carefully crafted costumes and the exquisite detail and ornateness of his saccharine tapestries are perhaps the most recognisable attributes of his work. Conversely, I wish to focus on his complicity in the underside of glamourous camp, as stressed by Hotz-Davies et al. (2018).

While Hotz-Davies et al. (2018) portray camp as dirt in its deviation from heteronormative gender and sex categories, black expressions of camp arguably offer a darker shade of dirt than its white counterparts. It is Ruga's tactics of staining, spoiling, contaminating and infecting (utterances of the interlaced categories of Black and queer) that inform counter penetration and fuse his strategy with camp. The performance described in the preamble took place during the 2012 National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape and formed part of Ruth Simbao's Making way (2012) exhibition. Titled Performance obscura (2012), the performance piece, in its most literal sense, invades history, memory and identity structures to expose the paradoxical freedom and faux peace that overshadows South Africa's postcolonial democracy: Ruga 'dismantles not only the Whiteness of The White Woman, but the supposed multicultural inclusivity of the Rainbow Nation itself' (Brown 2017:74) - a kaleidoscopic dream that is only accessible to those with their hands securely tucked into the pot of gold; a rainbow ideal that remains an impotent dream to the vast majority of Black South Africans. As The Future White Woman of Azania's poise bursts, the dark blood-like colour eclipses the blackness of the present too as it taints the whiteness of the past. Ruga's loyalty to grime gives substance to his glimmering tributes to camp - both in performance and aesthetic - and endows camp with a politically-charged seriousness.

Numerous discussions of camp draw on Susan Sontag's (1966 [1964]) seminal essay, 'Notes on camp'. Most of these reflect on an over-the-top, highly decorative and artificial style that representations of camp imbue. Sontag's (1966:280) essay offers a 'pocket history of camp' and, while it recently received much criticism (most notably from queer studies), it was the first attempt to expand camp from a mere cultural curiosity to critical discourse in western culture. In her 58 notations, punctuated by phrases from Oscar Wilde's writing, Sontag (1966:274) focuses her efforts on characterising (by way of examples) camp's love affair with the unorthodox via its 'artifice' and 'exaggeration'. Sontag (1966:277) also dedicates her notes to Wilde, which anchors the camp gesture in 'homosexuality'. For her, 'homosexual' individuals are lovers of camp who 'appreciate vulgarity' - 'an impoverished self-elected class, mainly homosexuals who constitute themselves as aristocrats of taste' (Sontag 1966:290). The long list of attributes suggests camp is 'good because it's awful' (Sontag 1966:292). Sontag (1966:277) describes it as an aesthetic mode that is often decorative while emphasising 'texture, sensuous surface, and style at the expense of content'. It is this lack of content and seriousness that renders the camp gesture, according to Sontag (1966:277), 'disengaged, depoliticised - or at least apolitical'.

The politics and poetics of camp (1994) is perhaps the most comprehensive text aimed at refuting Sontag's claims of camp's frivolity and triviality. As the editor of the book, Moe Meyer (1994:1), writes in the introductory chapter, camp 'is a suppressed and denied oppositional critique embodied in the signifying practices that processually constitute queer identities'. In a fashion similar to Sontag's, Meyer (1994:1) offers a list of camp's re-construction in its opposition to stable identity formations (after, or rather, in opposition to, Sontag),

Camp is political; Camp is solely queer (and/or sometimes gay and lesbian) discourse; and Camp embodies an explicitly queer cultural critique. Additionally, because Camp is defined as a solely queer discourse, all un-queer activities that have been previously accepted as 'camp', such as Pop culture expressions, have been redefined as examples of the appropriation of queer praxis. Because un-queer appropriations interpret Camp within the context of compulsory reproductive heterosexuality, they no longer qualify as Camp as it is defined here. In other words, the un-queer do not have access to the discourse of Camp, only to derivatives constructed through the act of appropriation.

Despite Meyer's (1994:1-2) elaboration of queer as not indicative of sex or gender but rather as an ontological provocation to 'dominant labeling philosophies', he remains fastidious in merging camp and queer as sole partners. For Meyer (1994:2, 7), camp's political disposition lies in its 'ontological critique' that he roots in queer activism -queerness' deviation from normative structures of ordering. While Meyer's (1994:1) argument for camp's political inclination is justified from this 'appropriation of queer praxis', this alliance also casts an essentialist shadow on queer's all-encompassing attitude. Despite Meyer's (1994:3) separation of queer discourse from sex and gender, he also attacks Sontag for 'downplay[ing], sanitiz[ing]' and offering 'homosexual connotations' as harmless and digestible for public consumption. In what is perhaps the primary shortcoming of his argumentation, Meyer (1994:138) alludes tangentially to camp's utilisation of 'marginal social identities'. Given the book's western outlook of queer practices (both in its argumentation and examples offered), it appears that, once again, Meyer's inclusive understanding of queerness is rather rudimentary. While I do agree with Meyer's assertion that camp offers political potential, I suggest an alternative logic to his mere piggybacking of camp on queerness' back as a way to provide an inclusive reading. Instead, I rely on the glimpses, instances and moments of juncture that my engagement with these terms, read via Ruga's artistic practice, reveals. I also suggest, in the next section, that an approach to thinking through camp's glamorous allure to recruit its darkness may very well illuminate the political - a shade of grime that, as mentioned before, is much gloomier when viewed through glasses of Blackness.

Notes on (the dirty side of) camp, or towards the politics of "dark camp"

Analyses blinded by camp's ostentatious and animated posture render primary, limited assumptions, or a form of 'failed seriousness' (Sontag 1966:287). To offer a corrective, I take advantage of camp's simultaneous engagement with the pretty and the ugly, read via a selection of Ruga's performance artworks, to consider Black queer identity within the local context. Infused then with camp's sensibility of extravagance, excess and embellishment, eclipsed by the darkness of their (dis)content, Ruga's avatars seduce and attract. In essence, they "camp it up".4 They are committed to dirt. Grime, in Ruga's hands, is not merely a by-product of camp's deluge. Instead, as the avatars stain, mark, defile, corrupt and taint, they bring into view camp's rebellious nature. To this end, and in opposition to Sontag's claims of camp's frivolity and lack of seriousness, I explore how dark camp reassigns its ostentation as defilement - a strategic and critical approach with political clout. This, in Ruga's sense, means not to be blindsided by the enchantment of camp caprice or Madiba's magic rainbow.5 Ruga's avatars throw shade on rainbowisms,6 failed promises, unavailing democracies and (hetero) normalising rhetoric. The Future White Woman of Azania oozes and gushes; she infiltrates - counter penetrates - the extremities of identities, history and politics in postcolonial South Africa.

The first avatar conjured up by Ruga is Miss Congo. Miss Congo (2007) (Figure 3) is a three-channel video piece filmed in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The video pictures Ruga as he, oblivious to his environment, embroiders a tapestry in ritualistic and methodical action. While Miss Congo does not deliberately engage in counter penetration, she indeed posits a link between the camp act and dirt or displacement. Miss Congo, sitting over what appears to be a gutter in Kinshasa and on a rubbish heap in a subsequent performance, is the embodiment of displacement. Her methodical embroidering of a tapestry compounds this - a labour-intensive task widely associated with stereotypical depictions of passive and decorous white Victorian women - a task generally contained to the privacy of the domestic space. Given the public visibility of this performance, Ruga enacts the task of stitching in awkward and taxing bodily positions. In his attempt at conflating the public/private and male/female gender roles, Ruga appears quite at home in these demeaning and marginal spaces of otherness where Black queer identities are often banished or exiled. With the enactment of this conventionally western, female activity, usually consigned to the private domain, Ruga's deliberate public visibility becomes an act of disagreement - a way to question traditional gender and racial categories (Siegenthaler 2009:14). But Ruga's overly comfortable inhabitance of gutters and waste sites urges us to enter the dark side even further. Perhaps Ruga's sense of ease if not a reflection of his state of mind, but rather part of his counter strategy. I suggest that Miss Congo cosily inhabits dirt in the same way that non-heteronormative individuals reclaimed the derogatory term "queer" during the 1980s. Her purposefully provocative embrace of the very spaces to which colonial imaginations have condemned Blackness -spaces where "Black" is equated with evil, darkness and savagery (Fanon 1986:113) offers a politically evocative critique of racist thinking. It is in the gutter that Miss Congo's needlework contaminates whiteness and femininity; it is on the rubbish dump that her Black narrative unpicks the harmonious threads of the past and, instead, 'forges ... history differently' (Freeman 2010:xi), or counter penetrates.

The notion of commingling the cherished and the filthy is not a new discursive exercise. To mobilise camp as a critical inquiry with a political agenda, I scratch around in the shadowy depths of western discourse that wears the same skepticism as Ruga's avatars. In the 1933 psychoanalytic text, Modern man in search of a soul, Carl Jung (2001[1933]:35) asks, '[h]ow can [one] be substantial if [one does] not cast a shadow?'. He continues that a 'dark side' is necessary too for a subject 'to be whole' (Jung 200:35). It is then one's shadow (both literally and metaphorically) that bears testament to our existence and constitutes complex and intricate bodies. It is the interplay of light and shade that fashions objects and figures in volume. While I do agree with Jung's suggestion that cognisance of one's so-called dark side is imperative, I depart from his parochially inscribed view. I wonder, what if one is cast as the shadow or dark side as so many Black and queer (and Black queer) individuals have been? How does one return to the light? Jung's dualistic thinking casts individuals in very stark terms without much modulation of the nuanced shades and tones moulded by the gradation of light and shadow, white and Black, male and female? Is it not after all through the effect of chiaroscuro (from Latin clarus meaning clear or bright, and oscuro meaning obscure) that intricate and elaborate portraits of the self are revealed?

As light and dark narrates form, frivolity, flatness and shallowness transform into gravity. Sontag (1966:276,280) traces camp's highly showy and stylised aesthetic back to the ornate style of design prevalent in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with its propensity to 'efface' nature in exchange for the overstated and artificial. While the attributes of the Baroque and Rococo periods are most evident in camp appropriations, I wish to add another - perhaps one of the most definitive marks of the period - namely, tenebrism (an expanded form of chiaroscuro). Derived from the Italian, tenebroso, the term translates as dark, gloomy or mysterious. As a popular style of painting at the time, mostly associated with Caravaggio, this dramatic illumination is a kind of overstated chiaroscuro with features of violent differentiation between lightness and darkness. Artists working in this manner implemented tenebrism to create a spotlight effect for theatrical and dramatic ends. Despite Sontag's (Ibid.) acknowledgement of camp as Y, she steers clear of appealing to this shadowy aspect. Even so, I summon the dark and the grim to inform my view of camp as a politically infused proposition to throw shade on queerness of a dark kind (with all its allusions to race and gender intact). But first, a brief review of literature that similarly explores the ends of darkness as a way to give impetus to black camp.

Initially published in 1966, Purity and danger. an analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo by Mary Douglas offers an exposition of purity and uncleanliness in various societies and cultures. Douglas (1966:36) pursues the notion that dirt is abhorrent to us because it is 'matter out of place'. She argues that our beliefs regarding trash are fundamentally about order - objects and subjects associated with grime are avoided as these are anomalies and 'dirt is the by-product of a systematic ordering and classification of matter' - they lie outside the (hetero)normative system (Douglas 1966:36). Margins are dangerous. Douglas (1966:37) extends notions regarding dirt to that of danger as 'all the rejected elements of ordered systems'. She implies that impure things are associated with evil, as bad consequences are believed to follow from breaking the moral code. Accordingly, dirt is ambiguous and anomalous, which causes anxiety by disrupting classification systems and the 'normal' ordered relations through which one understands the world:

For us dirt is a kind of compendium category for all events which blur, smudge, contradict, or otherwise confuse accepted classifications. The underlying feeling is that a system of values which is habitually expressed in a given arrangement of things has been violated (Douglas 1975:51).

In following Douglas's view of dirt as excess that falls by the wayside of normative systems of order, Black queer bodies highlight notions of displacement in their exile from mainstream fantasies premised on both race and gender. Continuing along these lines, Ruga's queerness inscribed upon his Black body (and his Blackness imprinted on his queer body) is then cast away as 'matter [doubly] out of place'. Ruga's camping draws from a long tradition of drag in South Africa that goes back to the mid-1950s. Despite the militant safeguarding of heteronormative gender roles, drag forms an indispensable part of the Western Cape's 'coloured communities' (Cameron & Gevisser 1995:7).7 It should be noted that, for the most part, drag and queer communities were strictly policed during the apartheid period, along with Blacks. At the time, 'high-art draggers' were mostly white with their work presented in prominent theatres such as Pieter-Dirk Uys and Nataniël and, more recently, artist Stephen Cohen (Cameron & Gevisser 1995:7).

Ruga is added to this line as the first Black artist to follow in this tradition. However, he is 'already marginalised', as many Black cultural beliefs of masculinity are in stark contrast to the subversion of conventionally understood sex and gender roles (Buys 2009:24). Nevertheless, as Anthea Buys (2009:28) suggests, Ruga's camp expression is laced with violent displacement. Ruga's unstable and ambivalent characters deliberately seize public space - places that enhance their queerness by appearing grotesquely as 'matter out of place'. In the same obdurate way, Ruga's narrative, too, seems ill at ease as he attempts to reconcile traditional Xhosa ceremonies practised in rural settings with his urban, cosmopolitan sense of community found in Cape Town and Johannesburg along with the violence and bigotry experienced during adolescence. From the ostentatious costumes in which Ruga's avatars are adorned to the excessively embroidered, garish tapestries and a penchant for the artificial and decorative, the artist acts irreconcilable narratives through the stylised prism of camp to invoke the repulsive. It is this sense of abhorrence and chaos that prompts Douglas' understanding of order/purity/cleanliness as binaries to dirt. Dirt invokes normative structures. Departing from Douglas' structuralist perspective that views purity and dirt as two opposites of a coin, I argue for a dirt-and-purity synthesis where the filthy threatens ordered systems of knowledge not only by exposing their binary nature but also by infecting, or to use Ruga's vocabulary, counter penetrating them. In turn, and specifically in Ruga's practice, camp's crudeness and obscenity are exorcised by his tactic of counter penetration - a ploy for cathartic ends, or the purification of the self.

Although camp is known for its juxtaposing of ideas or its embrace of duality and ambivalence, there are also no two distinct sides to camp. By choice, camp offers an entangled and indivisible 'totality of glam-and-dirt' that disrupts binary logic -rationality pursued 'in the interest of a wider deconstruction that takes the boundary between the precious and the dirty itself as its target' (Hotz-Davies et al. 2018:6). In a similar vein, the French intellectual Georges Bataille (1985) casts a wider deconstructive net when he criticises sentimentality and nostalgia in his essay, 'The language of flowers'. Bataille (1985:11) asserts that beauty, cleanliness and purity cannot be viewed as absolutes, as they are necessarily embroiled in their own perversity. Bataille's dismantling of the glamour of flowers elucidates the glam-and-dirt sum of the camp act that Hotz-Davies et al. recognise. Bataille (1985:10-12) decomposes flowers as rather unsavoury - a view past the prettiness of the petals exposes 'dirty traces of pollen' and 'hairy sexual organs'. The (short-lived) corolla rises from the 'stench of the manure pile' and 'relapse absurdly into its original squalor', thereby throwing nostalgia and sentiment into decline (Bataille 1985:12). In this way, camp offers dirt and preciousness simultaneously with the challenge to think 'the two together' rather than discerning either one or the other (Hotz-Davies et al. 2018:7). The acknowledgement of dirt in camp, the act of truncating 'beautiful things' to 'a strange mise en scène', may thus serve to undermine the very notion of sentiment and nostalgia, Bataile (1985:14) notes. This sense of defilement, fundamental to counter penetration, promotes camp to a subversive political strategy. It is in the association with excess, the grotesque, or as Corrigall (2013) suggests, the ongoing reproduction of coveted fashion items that become 'living being[s]' that Ruga's alternative reality is produced. A political myth that hovers between fact and fiction; the promise of a rainbow and a corrupted, skewed post-apartheid South Africa.

Perhaps one of the most apparent texts concerning dirt and defilement is Julia Kristeva's psychoanalysis of the abject. Kristeva (1982:1) considers the 'violent, dark revolt of being' within us political, and even beguiling. Abjection is matter cast away, expelled or thrown out; belched or discharged from the self or exiled from a group. As the lowest form of degradation, 'refuse and corpses show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live' (emphasis added) (Kristeva 1982:3). Bond Stockton (2006:12) suggests that Kristeva's theorisation of abjection as exclusion offers it up as 'a form of challenge and frightening seduction'. A challenge that, in Hotz-Davies et al. (2018:6), takes 'the boundary between the precious and the dirty itself as its target' in grimy camp. We are reminded: margins are dangerous. For Kristeva (1982:4), the abject 'disturbs identity, system, order' and 'does not respect borders, positions, rules'. Referring to Bataille, Kristeva (1982:65, emphasis in original) orientates the abject towards the political as a threat to 'one's own and clean self, which is the underpinning of any organisation constituted by exclusions and hierarchies'. To elaborate on the 'logic of exclusion that causes the abject to exist' (Kristeva 1982:69), she turns to Douglas' anthropological study. Kristeva (1982:69) notes that 'filth is not a quality in itself ... but applies to what relates to a boundary'. More specifically, grime represents that expelled, excreted or eliminated 'out of that boundary, its other side, a margin' (Kristeva 1982:69). Perhaps the signification of death is the ultimate boundary marking filth. The body's crossing of this boundary would render it a corpse - 'the most sickening of wastes' (Kristeva 1982:3). Death, as the most perverse form of dirt, infects life (Kristeva 1982:4). It is here where I wish to insert Ruga's strategy of counter penetration.

Of counter penetration, gift-giving and death drives

While the counter penetrative enterprise appears rather violent and affective, it operates as a double-edged sword. Ruga's act of counter penetration does not only taint normative thinking but reciprocates its dis-ease spreading intention to the artist's own body. Ruga's playing on death's doorstep amplifies the political intent of his camp efforts by implicating his body in its Blackness and queerness. The naivety of Beiruth #1 (2008) (Figure 4), a photographic series shot in Johannesburg, pictures Beiruth as a character donning a thick mane of artificial black hair held in place by a black helmet doubling as a facial disguise. She first appears in the artist's exhibition, ... Of bugchasers and watussi faghags, hosted by the Stevenson gallery in Cape Town in 2008. Her wig's allusion to West African ceremonial masks operates dually: both as a way to conceal her identity and as a veil that obstructs her view of the world around her. Perhaps she prefers to turn a blind eye to the farcical notion of the Rainbow Nation; maybe it is a sign of her 'historical blindness' to the fraught and unsettling past of the environment (Muller 2019:5). She is scantily dressed in a bright red and green floral-patterned two-piece leotard, a broad salmon belt pulled in tightly at the waist, black fishnet stockings and a pair of red stiletto ankle boots. Crouching like someone on the run, the figure appears out of place or exiled in her nondescript urban environments - places of transition and margins, spaces of danger. Beiruth is a bugchaser or gift-giver.

Bond Stockton (2006:2) suggest that the 'strained relations' between Blackness and queerness result from 'acts of debasement' which connect them as 'bottom states'. Through her investigation of shame in Black queer identity, Bond Stockton (2006:7) relies on degradation as strategy 'to make impure ... by adding extraneous or improper ingredients'. She draws on Fanon's classic text Black skin, white masks (1967) to position Blackness in relation to shame and debasement. Fanon begins his introductory chapter with an epigraph taken from Aimé Césaire (in Fanon [1967] 2008:1): 'I am talking of millions of men who have been skillfully injected with fear, inferiority complexes, trepidation, servility, despair, abasement'. In short, it is the patriarchal, colonial and imperial penetration that Ruga wishes to counter.

Bugchasing is a practice, typically among gay men, of pursuing sex with an HIVpositive partner to contract the virus. This risqué behaviour bears 'resistance to dominant heterosexual norms' as a way to deny society's stigma and rejection towards HIV-positive individuals and gay folk (Crossley 2014:239). Bugchasing 'spit[s] in the eye of "dominant" culture' (Crossley 2014:239). For Beiruth, her "occupation" is one of 'empathy and courage', as Buys (2010:483) explains, despite her putting herself at risk of injury, infection or death during her acts of counter penetration. Ruga's oppositional infiltration (Beiruth's bugchasing as a mode of displacement) turns upon itself. But this fact does not elude Ruga. His is a conscious act of (self)destruction - a tactic to dismantle restraining politics and undermine their seemingly invisible effects on the Black queer body. As mentioned previously, I suggest that, in the same way as queer subjects adopted the very term meant to denigrate them as part of a strategic move towards selfhood, Blackness (at least in Ruga's estimation) too embraces shame, dirt and abjection. Robert F. Reid-Pharr (2001:137) advocates that re-imagining Black identity necessarily regurgitates the debased history of the past. In his words, '[e]ven as we express the most positive articulations of Black and gay identity, we are nonetheless referencing the ugly historical and ideological realities out of which those identities have been formed'. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (2003:30) describes queer politics as a self-elected stigma - the act of an 'almost inconceivable willed assumption of stigma'. This stigma (the AIDS pandemic as a marker of both Africa - or Blackness - and queerness) taints the body as her heavy balloons bled and besmirched everything, including the artist himself, in their way.

Lee Edelman (2004:9) considers this invocation of the demise of the subject as a 'death drive'. For him, the negativity and exile experienced by queer folk in 'every form of social viability' translates to this mode of self-destruction. Sigmund Freud in Beyond the pleasure principle (1920) defines the concept as 'opposition between the ego or death instincts and the sexual or life instincts'. In Kristeva's (2006:9) terms, we might understand it as a move toward abjection, or, as Bond Stockton (2006:1) suggests, an 'embracing of shame'. Working from this premise, Edelman (2004), in No future: Queer theory and the death drive, sketches a profoundly grim view of queerness. Drawing on Jacques Lacan, his polemic focuses on the figure of the child as key in the proposition of the future. The child is premised in stark contrast to the future-negating stance of the lacking queer figure. For Edelman, queer individuals should rise to the occasion of being in opposition, obtrusive and negative in their embodiment of the instability of social and political order. In essence, they should indulge the death drive as Beiruth does.

Beiruth, along with Ruga's other avatars and their counter penetrative manners, are understood as 'willful subjects',8 in Sara Ahmed's (2014:9) terms. Ahmed offers a tale of disobedience, a willing of death and disturbing persistence. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm's (2011[1884]:420) short "fairy tale", The willful child, reads as follows,

[o]nce upon a time, there was a child who was willful and would not do as her mother wished. For this reason, God had no pleasure in her, and let her become ill, and no doctor could do her any good, and in a short time she lay on her deathbed. When she had been lowered into her grave, and the earth was spread over her, all at once her arm came out again, and stretched upwards, and when they had put it in and spread fresh earth over it, it was all to no purpose, for the arm always came out again. Then the mother herself was obliged to go to the grave, and strike the arm with a rod, and when she had done that, it was drawn in, and then at last the child had rest beneath the ground.

Willfulness, as illustrated by the "grim tale", ultimately undermines a subject's survival (Ahmed 2014:470). To be willful is to antagonise, arrest and disrupt the flow of things - to counter penetrate. Ahmed (2014:7) places emphasis on the historical under-standing of will as a 'straightening device' for subjects 'already bent'. To be deemed willful, Ahmed (2014:x) explains, 'is to become a killjoy of the future: the one who steals the possibility of happiness', thus aligning her purview to that of Edelman's. Ahmed (2014:470) notes this drive towards death and demise is evident in the fairy tale; a deliberate act of transgression is punished by 'a passive willing of death and allowing of death'. Willfulness is not only restricted to an unwillingness to move with the flow, but also implies a desire to obstruct the very flow of things. 'Striking bodies', in Ahmed's (2014:161) description, 'go on strike' (emphasis in original) to counter - a reference made to toyi toyi marches in The Future White Woman's procession. As Ahmed (2014:161) explains, striking in a political and historical sense portrays narratives of 'those willing to put their bodies in the way, to turn their bodies into blockage points that stop the flow'. Or, in Beiruth's terms, a willful embrace of the death drive; a counter penetration that forever taints identity and cast Black queer subjects in shadows of darkness and valleys of death.

I strain my discussions of the grimy, abject Black queer body briefly through one of camp's most written about attributes, namely performance, as I return my thoughts to The Future White Woman of Azania. Her counter penetration - piercing, infecting, staining and contaminating - informs complex and diverse views of Black queer identity. Attitudes that perverse rainbowism infect reductive politics and infiltrate normative ordering of both race and gender. A perspective of this kind confronts bodies in their degradation and begriming; bodies are smeared with the violence of the past and burdened by the incomplete narratives of history. Imaginably it is the embrace of this death drive - the willful willing through the dirt - that might offer a glimmer of hope. Maybe it is, as Kristeva (1982:3-4) suggests, that 'refuse and corpses show [Black queer subjects] what [they] permanently thrust aside in order to live'. Perhaps this is what Ruga aims to achieve - a necessary confrontation with all that debases his Blackness and queerness. A branding of his body to mark its willed and willful act.

Notes

1 . Intersectionality is widely attributed to the critical legal race scholar, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, who coined the term in 1989. However, the principal ideas of intersectionality are rooted in Black feminist, postcolonial and queer scholarship and activism that revealed the complexity and interconnectedness of experience and knowledge that shape our sense of self. Patrica Hill Collins (1990), bell hooks (1984) and Combahee River Collective (1977) are but a few of the early scholars who have drawn on intersectionality as a way to challenge inequities and promote equality. In continuing along this tradition, I intend to offer a reading of the intersection of Blackness and queerness in South Africa via Ruga's art practice that recognises identity as complex and shaped by the relationality of different social locations such as race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexuality, age, religion and so forth.

2 . The set of performance and photographic works was produced by Ruga during a residency at the Zenter furKulturproduction in Bern, Switzerland. The work centres on xenophobia and is an antagonistic response to a 'clearly xenophobic poster from a Swiss People's Party political poster' (Ruga cited by Libsekal 2014:156).

3 . After completing his secondary schooling, Ruga pursued an honours diploma in fashion history and design at the Gordon Flack Davison Design Academy in Johannesburg (Siegenthaler 2013:167).

4 . For Sontag (1966:281), the 'vulgar use' of the word camp as a verb, 'to camp', suggests a 'mode of seduction' that operates through flamboyance suggestive of a double meaning.

5 . The notion of the Rainbow Nation is a term coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu after the 1994 elections to represent an image of multiculturalism and the promise of a democratic future. Ideals associated with the rainbow are often seen as a myth and criticised for attempting to gloss over domestic and political issues within South Africa (Habib 1996:1). For Ruga, this promise is unrealised in terms of racial, social and gender equity.

6 . For Dagmawi Woubshet (2003:34), the discourse of rainbowism 'reifies politics of innocence, where history is forgotten, criticism is stifled, critique of institutions is perceived as ad hominem attacks, and critical self-inventory turns into a political correctness contest'. It is this utopian ideal that Ruga critically interrogates in his practice, as it glances over political rhetoric to offer up an imagined future while ignoring how racism, sexism and violence thwart the daily existence of South African life.

7 . See Defiant desire: Gay and lesbian lives in South Africa (1995) for a more elaborate account.

8 . Despite my following of English spelling conventions, the employment of the American spelling of the word "willful" (versus "wilful" in English) is deliberate in its alignment with Ahmed's theorisation. Ahmed (2014:322) notes that the American version allows for a reading of the "will" in "willful" - an essential aspect of her theorisation of willful subjects' engagement in deliberate acts of defiance and their will to ameliorate both their and others' lives.

REFERENCES

Athi-Patra Ruga. F.W.W.O.A. SAGA. 2014. Cape Town: WHATIFTHEWORLD. [ Links ]

Athi-Patra Ruga. The works 2006-2009. 2009. Cape Town: WHATIFTHEWORLD. [ Links ]

Bataille, G. 1985. Visions of excess. Selected writings 1927-1939. Translated by A Stoekl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Bolton, A. (ed). 2019. Camp: Notes on fashion. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [ Links ]

Bond Stockton, K. 2006. Beautiful bottom, beautiful shame. Where 'black' meets 'queer'. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Buys, A. 2009. Alleys, ellipses & the eve of context, in Athi-Patra Ruga. The works 2006 2009. Cape Town: Whatiftheworld:77-89. [ Links ]

Buys, A. 2010. Athi-Patra Ruga and the politics of context. Critical Arts 24(3):480-485. [ Links ]

Cameron, E & Gevisser, M (eds). 1995. Defiant desire: Gay and lesbian lives in South Africa. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Corrigal, M. 2013. When the party is over: Athi-Patra Ruga. [O]. Available: http://corrigall.blogspot.com/2013/12/when-party-is-over-athi-patra-ruga.html Accessed: 3 May 2020. [ Links ]

Corrigall, M. 2014. Unpicking the Azanian seam, in Athi-Patra Ruga. F.W.W.O.A. SAGA. Cape Town: Whatiftheworld:89-94. [ Links ]

Crossley, M. 2004. Making sense of 'barebacking': Gay men's narratives, unsafe sex and the 'resistance habitus'. The British Journal of Social Psychology 43(June):225-244. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. 1966. Purity and danger. An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Douglas, M. 1975. Pollution, in Implicit meanings: Essays in anthropology, edited by M Douglas. London: Routledge:47-59. [ Links ]

Douglas, M (ed). 1975. Implicit meanings: Essays in anthropology. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Edelman, L. 2004. No future: Queer theory and the death drive. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1986. Black skin, white masks. Translated by CL Markham. London: Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1986. Of other spaces. Diacritics 16(1):22-27. [ Links ]

Freeman, E. 2010. Time binds: Queer temporalities, queer histories. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Freud, S. [1920] 2015. Beyond the pleasure principle. New York: Dover Publications. [ Links ]

Grimm, J & Grimm, W. 2011 [1884]. Grimm's complete fairy tales. Translated by M Hunt. San Diego: Canterbury Classics. [ Links ]

Habib, A. 1996. Myth of the Rainbow Nation: Prospects for the consolidation of democracy in South Africa. [O]. Available: http://www.iss.co.za/Pubs/ASR/5No6/Habib.html Accessed 10 July 2011. [ Links ]

Hotz-Davies, I, Bergmann, F & Vogt, G (eds). 2019. The dark side of camp aesthetics. Queer economies of dirt, dust and patina. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Johnson, P. 2005. 'Quare' studies, or (almost) everything I know about queer studies I learned from my grandmother, in Black queer studies: A critical anthology, edited by P Johnson & MG Henderson. Durham & London: Duke University Press:124-157. [ Links ]

Johnson, P & Henderson, MG (eds). 2005. Black queer studies: A critical anthology. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Johnson, P & Henderson, MG. 2005. Introduction: Queering black studies/'quaring' queer studies, in in Black queer studies: a critical anthology, edited by P Johnson & MG Henderson. Durham & London: Duke University Press:2-16. [ Links ]

Jung, C. 2001 [1933]. Modern man in search of a soul. Translated by WS Dell & CF Baynes. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. 1982. The power of horror: An essay of abjection. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Libsekal, M. 2014. When sheroes appear: Missla Libsekal interviews Athi-Patra Ruga, in Athi-Patra Ruga. F.W.W.O.A. SAGA. Cape Town: Whatiftheworld:155-166. [ Links ]

Meyer, M (ed). 1994. The politics and poetics of camp. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Meyer, M. 1994. Reclaiming the discourse of camp, in The politics and poetics of camp, edited by M Meyer. London & New York: Routledge:1-22. [ Links ]

Newton, E. 2000. Margaret Mead made me gay. Personal essays, public ideas. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Of Gods, Rainbows & Omissions - Athi-Patra Ruga. 2019. Cape Town: Whatiftheworld & Big Paper. [ Links ]

Reid-Pharr, RF. 2001. Black gay man: Essays. London & New York: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Ruga, A. 2007. Miss Congo. [O]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YZaQ0_gocB8 Accessed 3 May 2020. [ Links ]

Sedgwick, EK. 2003. Touching feeling: Affect, performativity, pedagogy. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Siegenthaler, F. 2013. Visualizing the mental city: The exploration of cultural and subjective topographies by contemporary performance artists in Johannesburg. Research in African Literatures 44(2):164-176. [ Links ]

Sontag, S. 1966 [1964]. Against interpretation and other essays. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux:275-292. [ Links ]

Warner, M (ed). 1993. Fear of a queer planet. Queer politics and social theory. Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Woubshet, D. 2003. Staging the Rainbow Nation. Art South Africa 2(2):33-36. [ Links ]