Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.34 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a6

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Ellen Ripley, Sarah Connor, and Kathryn Janeway: The subversive politics of action heroines in 1980s and 1990s film and television

Janine Engelbrecht

School of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa janine.engelbnecht@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9681-5137)

ABSTRACT

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, female characters that are different from the sexualised and passive women of the 1960s started appearing in science fiction film and television. Three prominent women on screen that reflect the increasing awareness of women's sexualisation and lack of representation as main protagonists in film, and that appeared at the height of feminism's second wave, are Ellen Ripley from the Alien franchise (1979-1997), Sarah Connor from the Terminator film series (1984-1991;2019) and Kathryn Janeway from the Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001) television series. These female characters were, in contrast to their predecessors, the main protagonists and heroes at the centre of their respective narratives, they were desexualised, and they were not subservient to their male contemporaries. Most importantly, and as I show in this paper, they are complex, hybrid characters that do not perpetuate the masculine/ feminine dichotomy as their predecessors did. I further argue that it is these characters' hybridity that makes them heroines instead of simply being male heroes in female bodies, which they are often accused of. I term the heroine archetype presented by these characters the "original action heroine", and I argue that these women are likely candidates to be regarded as the first heroine archetype on screen.

Keywords: Second wave feminism; science fiction film; action heroine; Ellen Ripley; Sarah Connor; Kathryn Janeway.

Introduction

Women have been pivotal in science fiction (sci-fi) since the earliest sci-fi films. The first full-length sci-fi film made, Metropolis (Lang 1927), features a machine-woman named Maria, who leads the city's workers in a revolt against its intellectuals, and is ultimately burned at the stake by the men of Metropolis, as central to the narrative (Huyssen 1986:67). Since Maria, representations of women in sci-fi continued to be largely limited to 'projection[s] of the male gaze' that perpetuate 'the myth of the dualistic nature of women as either asexual virgin-mother or prostitute vamp' and portrayed as 'either oversexed or undersexed aliens or as human secretaries and assistants', all of which enforce sexual difference (Lathers 2010:6). Some of the most notable female characters in sci-fi include Princess Leia and Padme from the popular Star Wars film series, who are often sexualised despite their statuses as "empowered" women. They are accompanied by countless other women in sci-fi film and television including Barbarella (Vadim 1968), Peri Brown from Doctor Who (1963-1989), Cassiopeia from Battlestar Galactica (1978-1979), Diana from V (1984-1985), Priss (an android "pleasure model") from Blade Runner (Scott 1982), and many women throughout the various Star Trek series, such as Lieutenant Uhura, Jadzia Dax, Counsellor Deanna Troi and Droxine to name only a few, who are not only sexualised, but are often oppressed by male characters.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, female characters that are different from the sexualised and passive women of the 1960s started appearing on screen. Lieutenant Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) was the first significant action heroine whose representation departed from decades of above-mentioned female tropes in sci-fi. Ripley appeared for the first time in Ridley's Scott's cult horror film, Alien (1979), in which an alien (also termed a xenomorph) makes its way onto the spaceship and wipes out the entire crew, and only Ripley manages to escape. After Alien gained considerable popularity in sci-fi, Ripley subsequently returned in three more Alien films and gained iconic status as an action heroine. The appearance of more heroines on screen who reflect the increasing awareness of women's sexualisation and lack of representation as main protagonists in popular culture are Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) from the Terminator film series (Cameron 1984-1991) and Captain Kathryn Janeway (Kate Mulgrew) from the Star Trek: Voyager television series (1995-2001). These female characters were, in contrast to their predecessors, the main protagonists and heroes at the centre of their respective narratives, they were desexualised, and they were not subservient to their male contemporaries. These heroines not only reveal second wave feminism's profound influence on representations of women in cinema,1 but more importantly prompt questions such as what makes an action heroine different from an action hero? Is she simply a male hero in a female body? Should she not be different from an action hero precisely because of her gender?

These questions have certainly been interrogated by the myriad literature on female action heroines in film and television, but as I aim to show in this paper, a unique heroine archetype can be found within these action heroines that emerged in a Zeitgeist where second wave theory and activism was prolific. It will become evident throughout this paper that these heroines are complex, hybrid characters that do not perpetuate the masculine/feminine dichotomy as their predecessors did. I argue that it is these characters' hybridity that makes them heroines instead of simply being male heroes in female bodies, which suggests a novel category of female heroism not yet identified in literature theorising these characters. I term the distinctive heroine archetype presented by these characters the "original action heroine", and I argue that these women are likely candidates to be regarded as the first heroine archetype in film. I first outline how these three heroines negotiate second wave early liberal and cultural feminist notions of female empowerment, and then consider how contradictions between these two feminisms simultaneously embodied by these characters in fact create complex and hybrid heroines.2I also briefly touch on recent feminist scholarship and contemporary female action heroines that seem to embrace similar notions of hybridity, however, a thorough analysis of contemporary feminism and representation is beyond the scope of this paper and perhaps an avenue for further research.

Early liberal feminism and representations of women in film

Early liberal feminism, which advocates for gender sameness, was second wave feminism's 'first [version of] equality' and emerged in the 1960s in America (Evans 1995:28). Many recognise Betty Friedan's influential text, The Feminine Mystique (1963), which is also considered to be one of the pioneering second wave texts, as the catalyst for early liberal feminism, as she calls on women to pursue careers (like men do). For Friedan (1963:14), in the media specifically, images that show women 'bak[ing] their own bread' and 'sew[ing] ... their children's clothes' perpetuate the notion of the 'feminine mystique', which problematically suggests that women should solely engage in domestic tasks, while only men should 'make the major decisions' and generate incomes. Simone De Beauvoir (2011 [1949]:23), writing in France a decade earlier, coined a similar term, the 'eternal feminine', that exposed the essentialist understandings of women upon which twentieth century western society was built.

The eternal feminine, for Beauvoir (2011 [1949]:24) essentialises women by postulating that 'no woman can claim.. .to be situated beyond her sex'. The eternal feminine suggests that there exists something like a 'true woman', an essential femininity, which is 'frivolous, infantile, irresponsible' and 'subjugated to man' (Beauvoir 2011 [1949]:32-33). Moreover, the eternal feminine conforms to and perpetuates stereotypes that women are hysterical,

irrational, caring, nurturing, and so forth (Beauvoir 2011 [1949):33), or in Friedan's (1963) conceptualisation, that women are good at domestic tasks because they are women. Another task of the early second wavers was therefore to establish an ideological divide between biological sex (male/female) and socially constructed "gender" (masculine/ feminine) (Bradley 2007:14), since the feminine mystique and eternal feminine are based on the premise that women's behaviour is somehow directly attributed to their reproductive and mothering capacities. Sexualised images of women in sci-fi, or representations of women as "space secretaries", inevitably perpetuate these myths of femininity, and essentialises women by causally linking their sex with their gender, which reinforces sexual difference.

Ascribing masculinity (in all its guises) upon the female sexed body is therefore one strategy early liberal feminism uses to subvert the feminine mystique, or the eternal feminine. For Judith Evans (1995:29-31), the 'true characterization' of liberal feminists is that 'they want to advance women to what is conventionally regarded as equality with men, within the various hierarchically ordered groups', which includes equality in terms of women's participation in all social and economic structures. Although Beauvoir is not categorised as early liberal, some arguments presented in her seminal text for feminism, The Second Sex (1949), ascribe to these early liberal arguments. By tracing the entire history of women's '[en]slave[ment]' by men, ranging from biology to myths about femininity, to religion, Beauvoir (2011 [1949):29) gives insight into what this "equality" entails. Most tellingly, Beauvoir (1949:857) contends that if women were raised 'with the same demands and honors, the same severity and freedom, as her brothers, taking part in the same studies and games, promised the same future, surrounded by women and men who are unambiguously equal to her' from the beginning, their situation will be vastly improved. Furthermore, mother and father would enjoy equal matrimonial and material responsibility for a (girl) child, who would be raised in 'an androgynous world around her' and not an exclusively 'masculine world' that subjugates women (Beauvoir 2011 [1949):857; emphasis added). As a consequence, a woman would be able to 'prove her worth in work and sports, actively rivaling boys' (Beauvoir 2011 [1949):857).

Although Beauvoir's (2011 [1949):857) vision articulated here seems somewhat idealistic, her specific ideas regarding gender sameness, as well as Friedan's (1963) call for women to enter the workforce, are to an extent manifested in the representations of Ripley, Janeway and Connor. By having their own careers, and choosing their careers above familial obligations, Ripley and Janeway display a version of femininity that is not exclusively tied to domesticity. Ripley is a blue-collar worker and is revealed in Aliens (Cameron 1986) to have left her 8-year old daughter, Amanda, behind in order to serve on The Nostromo. Janeway is a Starfleet officer, who similarly leaves behind her fiancé, Mark, in the pilot episode, Caretaker (1995), to captain the starship Voyager. Moreover, the status of captain of a Starfleet vessel in Star Trek is a prestige only reserved for white males up until 1995, therefore as the first female captain in Star Trek, Janeway 'prove[s) her worth', as Beauvoir (2011 [1949):857) would say, in this established masculine sphere and envisions a future where women are raised in 'an androgynous world'.

In terms of gender, Beauvoir (2011 [1949):26) writes that the "male", masculinity, and therefore "man", are constructed as the norm, the 'Subject', the 'Absolute', and femininity and "woman" as its deficit, the 'Other', which always exists in relation to the Subject. In this way, gender and sex are categorised in terms of binary oppositions, where, as another French feminist, Hélène Cixous (1987), has shown, 'femininity is always associated with powerlessness' and masculinity, by implication, with power (Cavallaro 2003:24). Binaries, such as masculine/feminine, culture/nature, head/emotions, intelligible/ sensitive, logos/pathos (see Cixous & Clément 1987:63) are also not simply on equal opposite ends of the spectrum, but hierarchical, where the masculine is always favoured above the feminine (Hansen 2000:201). In denaturalising the link between gender and sex, and in exposing the construction of the masculine as Absolute and the feminine as Other, second wave feminists were able to challenge the notion that 'gender differences are "natural", arising from genital and genetic differences, and thus inevitable and impossible to change' (Bradley 2007:16).

These three heroines use a similar strategy in order to subvert stereotypes perpetuated by the eternal feminine in in their display of 'toughness', to which Sherrie Innes (1999:13) ascribes two sets of definitions. First, 'toughness' refers to the capacity of a hero to perform great physical feats with (his) physical endurance, sturdiness and ability to overcome physical fatigue; and second, it refers to the hero's 'intellectual or moral endurance', steadfastness, persistence, and ability to resist influence (Innes 1999:13). As Innes (1999:14) points out, these characteristics of toughness have mythically become associated solely with male heroes, such as Captain James T. Kirk from Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-1969), Bruce Wayne, Rambo and the T-800 Terminator model, to name only a handful among the multitude of male heroes in film and on television.

Ripley is, in the sense of both definitions, tough. George Faithful (2016:353-354) notes that Ripley displays 'selfless courage' and 'technical prowess' and Stephen Scobie (1993:82) further recalls that she is 'cool, resourceful, courageous and able to save herself without the assistance of a man'. For example, in Alien, Ripley strictly adheres to quarantine protocol and refuses to let Kane, who has a "facehugger" on his face, along with the other (male) members, back onto the ship. Ripley's decision and her demeanour in this event are rational and unemotional. In Aliens especially, Ripley's physical strength and resilience is apparent. She shows not only physical endurance when she battles against the xenomorph queen, but she also wields an elaborate machine gun/flamethrower. In another scene in Aliens, Ripley possesses the physical strength and technical knowledge to skilfully operate a cargo lifter, and in Alien, she efficiently initiates the self-destruct sequence, to list only some examples. In this way, Ripley's display of toughness show the original action heroine's embrace of Beauvoir's (2011 [1949]:857) notion that women can 'actively [rival] boys' in all aspects.

Similar to Ripley, in Terminator 2 (Cameron 1991), Sarah Connor, who is the future mother of John Connor, the person who will save humanity from a machine-led apocalypse, also demonstrates 'traditional [male] heroic qualities', such as strength, stamina and determination (Helford 2000:294). In The Terminator (Cameron 1984), Kyle Reece travels back in time to protect Connor from a killing machine, called a 'terminator', and by the end of the film she is pregnant with John. Terminator 2 displays a different Connor who underwent a radical transformation in the interim between The Terminator and Terminator 2 (Faithful 2016:355); she has been placed in a mental asylum, her son has been taken away from her, and this time it is she who protects her son from another terminator who comes back from the future to kill him. For Faithful (2016:355), Connor is even more overt in her display of masculinity than Ripley:

By Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) Connor had become a violent survivalist. In mind, body, and spirit, actor Linda Hamilton portrayed a woman now utterly given over to her mission. With ruthless efficiency, she acquired the hardware and skills that she, her son, and the remnant of humanity would need to survive the machine-dominated future. She has moulded herself into the human equivalent of a terminator, eschewing emotion, honing her physique, and developing lethal potential.

Connor handles a variety of weapons in Terminator 2, from knives, to pistols and machineguns, to grenades, rivalling the deadly terminator (played by Arnold Schwarzenegger) himself. Similar to Ripley, who ultimately sacrifices herself in order to save humankind from the xenomorph threat, Connor is ruthless in the pursuit of her mission.

Kathryn Janeway is similarly often confronted with gruelling situations, and as a Starfleet Captain, she is frequently placed in the position to make reasonable, logical, and diplomatic decisions. In Star Trek: Voyager, Captain Janeway and her crew become stranded in the fictional Delta Quadrant, 75 000 light years away from earth. Janeway's task is to bring her crew back to earth safely while facing numerous unpredictable space anomalies and dangerous enemies on a theoretically 75-year journey home. Characteristics that the two male captains that came before Janeway, Captain Kirk and Captain Picard, displayed, such as 'reason, strength and power', as well as leadership, are exhibited in Janeway, who 'leads, guides, advises and commands her crew' (De Gaia 1998:23-24).

Janeway is absolute in the application of Starfleet principles, to the point that she strands Voyager and its crew thousands of light years away from home in order to adhere to them. Furthermore, Janeway 'commonly [makes] statements in which she refuses to sacrifice power and force for a perhaps more "feminine" precision', such as her statement about not 'delicately' manoeuvring a spacecraft, but rather '[punching] your way through' in the episode Parallax (1995) (Dove-Viebahn 2007:603). In these ways, the original action heroines discussed here display 'toughness', which is associated with masculinity, as Innes (1999:13) articulates it, in terms of their physical and personal capacities, and an embrace of early liberal sexual sameness.

Evidently, second wave liberal feminism's strategy to achieve gender equality is thus to be the same as men. For Beauvoir (2011 [1949]:856), as it is for Friedan (1963:13), 'shedding [one's] femininity', and dissolving the feminine mystique, in order to attain these goals is not necessarily a large price to pay either. Androgyny and equality in the ways argued by liberal feminists are not only reflected in the original action heroines' social positions and personalities, but it is no surprise that sexual sameness is revealed in their physical appearances as well. For example, in Alien and Aliens, Ripley wears a loose-fitting boiler suit that does not emphasise her feminine features, but rather, is practical and similar to the clothing the other male members of the crew wear. In Alien 3 (Fincher 1992), Ripley is seen in a military jacket and baggy pants, and she becomes almost indistinguishable from the male prisoners on Fiorina 161, who wear similar clothing (see Figure 1). Notably, Ripley's hair also becomes shorter over the span of the first three Alien films, to the point where she is completely bald in Alien 3.

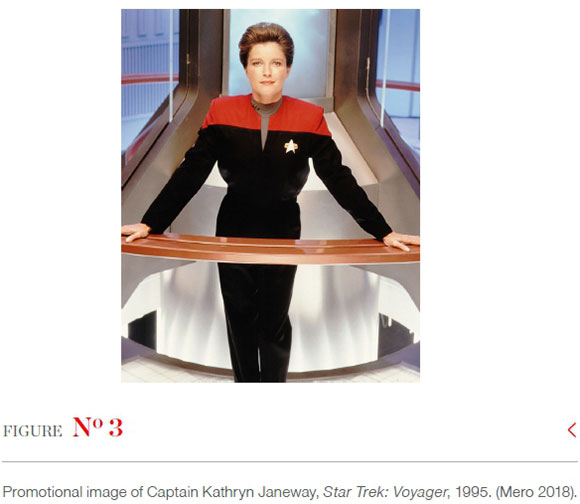

Similarly, Connor is seen in a tank top, and baggy military-style pants throughout Terminator 2 (see Figure 2). Although Connor's tank top may be revealing, its purpose is not to draw attention to her breasts, but rather her muscular arms. Janeway, although appearing in her nightdress or other dresses on a few occasions throughout the series, is in her unisex Starfleet uniform for the most part of the 172 Voyager episodes. As seen in Figure 3, Janeway also wears an unrevealing, loose-fitting outfit that, like Ripley's boiler suit, does not draw any attention to her feminine features, and Janeway's hair similarly becomes shorter throughout Voyager's journey.

Cultural feminism and representations of women in film

I have up until this point discussed the emphasis placed on these three characters' adoption of masculine traits as a means to subvert essentialist understandings of women. As I have alluded to earlier though, the original action heroine is masculine in her physical appearance and character, yet she simultaneously displays traits historically associated with femininity.3 Characteristics such as emotion, intuition, and nurture, that are criticised by Beauvoir (1949) and Friedan (1963) for reinforcing sexual difference, are displayed in Ripley, Connor and Janeway in addition to the masculine traits identified earlier. Just as these heroines embody the core values of early liberal feminism, they also negotiate aspects of one of the last second wave feminisms,

cultural feminism, in their representation. I show in this section that from a cultural feminist perspective, instead of "feminine" attributes causing these heroines to descend into negative tropes of femininity, such as the damsel-in-distress that causes 'the confusion of a dual identity' (Han & Song 2014:45),4 the possession of these traits has the potential to construct a unique heroine archetype. As I assert, it is the original action heroine's hybridity of masculinity and femininity that makes her a heroine that is different from the archetypal male action hero.

A branch of second wave feminism - one that advocated for gender difference - was theorised toward the end of the twentieth century. Cultural feminism believes, in contrast to the "gender sameness" agenda of early liberal feminism, that 'women's characteristics and values are for the good' and are in fact 'superior and ethically prior to men's, and should [therefore] be upheld' (Evans 1995:76). Despite widespread criticism that a sexual difference approach reinforces essentialist understandings of women 'by positively valuing what is distinctive about the female, rather than the male body' in its attempts to undermine patriarchy (Annandale & Clark 1996:20), in theorising an action heroine, sexual difference provides a means for the heroine to transcend simply being a male hero disguised as a woman.

In the case of Ripley, her stereotypically feminine personality qualities, instead of her masculine traits (displayed by most male heroes), aid her in survival. In Aliens a dichotomy is set up between masculinity, which proves to be ineffective against the xenomorphs, and femininity, which ultimately defeats the xenomorph queen and survives. Caldwell (2010:127-128) observes how the marines in Aliens represent the opposite of the 'empathetic and intuitive' Ripley in their mechanical, violent and anti-intellectual approach to eliminating the xenomorphs; in their briefing the marines claim that they only need to know where the creatures are so that they can shoot them; all other information is irrelevant. Despite the marines' obvious display of masculinity and bravado throughout the film, however, it is Ripley through her more indirect, 'inventive', 'resourceful', intuitive, and by implication, feminine, approach that makes it out alive (Caldwell 2010:128).

In Alien: Resurrection (Jeunet 1997), a similar dichotomy between masculinity and femininity exists. The resurrected Ripley displays an even more apparent femininity than that of Ripley in Aliens in terms of her heightened intuition and her deep connection to the xenomorph queen that represents nature at its most primal (Caldwell 2010:129). The crew of the cargo ship, The Betty, which is a group of mercenaries, as well as the group of scientists that cloned Ripley, portray traits associated with masculinity, while the 'outsiders', Ripley, Call, and Dom, are aligned with femininity (Di Risio 2015). Scientists throughout the Alien franchise symbolise patriarchy and its attempt to control the female body, and the male crewmembers from The Betty have a violent approach to the xenomorphs similar to that of the marines in Aliens. Once again, brute strength and science prove to be ineffective against the xenomorphs and it is Ripley through her intuition and intimate connection with the aliens, as well as Call, a female android symbolised as the opposite of the (patriarchal) inhumane humans in the film (Di Risio 2015), and Dom, a paraplegic who lacks the physical strength associated with masculinity, that make it out alive.

Evidently, instead of these qualities causing her to develop a 'dual identity', where she identifies with male characteristics while also descending into negative female archetypes, her feminine qualities rather aid in her survival. In her analysis of the character of Ripley, Judith Newton (1980:294;296) confirms that Ripley's character 'appropriates qualities traditionally identified with male, but not masculanist, heroes' while simultaneously being reinvested with 'traditionally feminine qualities', as is seen in the examples cited above. Although some theorists maintain that Ripley's "feminine qualities" problematically perpetuate gender difference, I agree with Elizabeth Graham (2010:101) that this characterisation makes Ripley 'an autonomous character that does not fit the false dichotomy of masculine versus feminine'.

Similarly, in Janeway's case, her "feminine" attributes often save Voyager and its crew from certain destruction. Bowring (2004) is of the opinion that Janeway's intuition rarely leads her to success, but this presents a limited reading of the 172 Voyager episodes. For example, in Counterpoint (1998), Janeway uses her instincts to discern the intentions of a manipulative alien and with it ultimately rescues her crew and a group of refugees. In Hope and Fear (1998), again Janeway's intuition not to trust a message from Starfleet that claims to be able to get Voyager home within three months prevents her and her crew from being assimilated by the Borg. Moreover, Janeway's compassion for her crew and other species also saves Voyager on multiple occasions. In the episode Night (1998), Janeway decides to aid a group of aliens rather than handing them over to their enemy, who is using their region of space to dump theta radiation, even though the aliens' enemy offered to get Voyager out of the desolate region. Initially it appears that Janeway's compassion will get Voyager stuck in the sector for two years, however, owning to her care for the species, the aliens ultimately help Voyager escape the region through a vortex. Similarly, in The Void (2001), Janeway focuses on making alliances rather than stealing from other ships in order to escape another desolate area of space, to mention only two examples.

Furthermore, Aviva Dove-Viebahn (2007:600) notes that Voyager is a military vessel, but owning to becoming stranded, it is forced to simultaneously become a domestic space where the crew lives, therefore destroying 'the dichotomy between public and private' and by implication, masculine and feminine (Haraway 1991:168). Consequently, Janeway is not only the crew's captain, who represents the Lacanian Father that is 'the disciplinarian and topmost authority on the ship', 'the voice of reason in tight situations' and the 'ethical and moral . enforcer of society's laws', but she is also a mother figure who 'nurtures her crew', 'provides a domestic and protective haven' for them, and is responsible for their 'well-being and garners their devotion' (Dove-Viebahn 2007:605). Janeway's 'relative asexuality' caused by her remaining alone throughout Voyager's journey further points to the show's attempts to 'leave Janeway unfettered by masculine or feminine roles' that could potentially be dictated through romantic relationships (Dove-Viebahn 2007:604).

Although Connor is notably more masculine in character than Ripley and Janeway, her compassion, 'inventive[ness]' and 'resourcefulness]', as Ripley is described by Caldwell (2010:128), aid in hers and John's survival. Connor realises in the beginning of Terminator 2 that she will not be able to escape the mental institution by using brute force, and rather employs a more 'inventive' approach (Caldwell 2010:128). Connor successfully uses only a paperclip, a syringe and cleaning materials to escape from the heavily guarded institution. In another instance, Connor's compassion leads her to abort assassinating Miles Dyson, the person responsible for inventing Skynet that causes the apocalypse. By keeping Dyson alive, Connor manages to break into the labs where all his research is kept, and destroys it, which ultimately leads to the world avoiding Judgment Day.

Notably, all three of these heroines are also represented as (biological or non-biological) mothers. Even though their motherhood has often been claimed to undermine their feminist potential, as it essentially suggests that 'being female means being, always already, a mother' (Wood 2004:33), I contend that their motherhood becomes not only one of their greatest sources of strength, but it also aids in their construction as hybrid characters. For cultural feminists, certain female roles, especially motherhood, have been devalued by men and therefore it is feminism's task to reclaim and celebrate these roles (Evans 1995:76). Adrienne Rich's interrogation of motherhood in her book, Of Women Born (1986) particularly informs a cultural feminist agenda, and her conceptions of how motherhood can be liberatory for women are also evident in representations of all three original action heroines.

In Of Women Born (1986), it becomes apparent that for Rich (1986), twentieth century motherhood has become nothing less than 'penal servitude' (Rich 1986:14). Rich (1986:13-14, emphasis in original) is of the opinion though that motherhood 'need not be' this way though, and she explicitly distinguishes between 'two meanings of motherhood', namely 'the potential relationship of any woman to her powers of reproduction and to children; and the institution, which aims at ensuring that that potential - and all women - shall remain under male control'. Rich (1986:13) contends that it is this institution, rather than motherhood itself, that 'has ghettoized and degraded female potentialities'. Institutionalised motherhood, for Rich (1986:42), is problematic because it 'demands of women "maternal instinct" rather than intelligence, selflessness rather than self-realization, relation to others rather than the creation of self'. It further perpetuates stereotypes that maternal love is 'selfless' and that a mother 'is a person without further identity' (Rich 1986:22).

In the words of Evans (1995:84), the conclusion of Rich's (1986) arguments in Of Women Born (1986) is that 'motherhood gives women power'. For Ripley, Connor and Janeway, despite the fact that they are in various ways manifestations of liberal feminist conceptions that seem to disregard motherhood, it is significant that they remain mothers of either biological or non-biological, human or alien, children. Although Rich's (1986) position has limitations, as it may perpetuate essentialist views of women, the emphasis on all three the original action heroines' roles as mothers displays cultural feminism's celebration of motherhood, and allows for the construction of a heroine.

Following a cultural feminist argument, Thomas Caldwell (2010:130; emphasis added) therefore sees the alignment of Ripley with motherhood as facilitating a 'positive representation of femininity as [both] resourceful and nurturing' and not one or the other. Sarah Bach and Jessica Langer (2010:88-89; emphasis in original) provide an analysis of Ripley's adoption of Newt that especially denies what Adrienne Rich (1986) sees as institutionalised motherhood that reinforces the nuclear family structure:

Ripley's motherhood of Newt is unconnected to the process of childbearing as Newt is her surrogate but not her biological, daughter ... The relationship [therefore] represents a fracturing of the normatively sexual mode of motherhood, in her emotional connection to Newt despite her lack of biological connection rather than because of the biological connection between a mother and a daughter. It is an active and chosen connection rather than a passive biological connection and functions as a site of Ripley's power.

Bach and Langer (2010:89) thus argue that the bond between Ripley and Newt does not situate Ripley within the confines of the nuclear family, but is rather a bond that exists 'outside of the patriarchal ideal of the biological, nuclear family as primary unit of society', and therefore has the potential to transcend gender binaries imposed by the nuclear family structure.

Furthermore, although Ripley is a warrior in Alien before she becomes a mother (Faithful 2016:354), she only fully displays her "toughness" after she has developed maternal feelings towards Newt, and ultimately risks her life in order to face off against the xenomorph queen and save Newt. Faithful (2016:361) suggests that in the process of protecting their children, Ripley and Connor become the 'ultimate human [beings)' that are 'survivor[s)', 'warrior[s)' and 'committed parent[s)'. Evidently, by simultaneously being mothers (that is associated with women and femininity, and is not associated with male heroes) and 'warrior[s)' (Faithful 2016:361) capable of wielding heavy weapons and saving the world (like male heroes do), these two heroines embody characteristics associated with masculinity and femininity and display a different form of heroism than that of male heroes.

Janeway also occupies the position of mother to her crew. In the episode, Q2 (2001), the omnipotent being, Q, explicitly says to Janeway 'you are not [a mother) in a biological sense, but you are certainly a mommy to this crew' when she tells Q that she knows nothing about motherhood after he asks her to help him raise his son, Q2. Various theorists, such as Susan De Gaia (1998:23), have also identified Janeway as 'a symbolic figure who embodies the essential feminine associations of motherhood, home and land'. Again, Janeway's motherhood has also been read as constricting her to traditional stereotypes of femininity. De Gaia (1998:21;27) for example acknowledges that Janeway's motherhood, like that of Ripley, might tie her to es-sentialist female qualities such as intuition and care-giving, and according to Debra Shaw (2006:75), compulsory heterosexuality as an institution that oppresses women. In the context of Voyager, this is reinforced through Janeway's symbolic role as the crew's mother.

I agree with De Gaia (1998:22-23), however, that even though conventional images of women and femininity are employed in Voyager, Janeway's status as captain and substitute mother to her crew subverts these myths. What Janeway's motherhood allows her to do is to bring together 'the essences of feminine and masculine through the conventional associations of mother with care and nurture, and of captain with reason and power' (De Gaia 1998:25). Moreover, because "female qualities" such as 'emotionalism, intuition, and physicality support secondary associations of women with occupations like domesticity, food service, and health care on the one hand and prostitution and pornography on the other' (De Gaia 1998:22), the fact that Janeway possesses these characteristics through her care for the crew while still being the authoritative captain of a starship subverts these associations. Janeway's role as the crew's surrogate mother is therefore crucial to her hybridity, just as that of Ripley and Connor.

Contemporary feminism and hybridity

I have done this analysis in order to finally distinguish the difference between a "female hero" and a "heroine". The term "female hero", to my mind, refers to a woman who does and is everything associated with male heroism (that is, a male hero in a female body), where the term "heroine" connotes a specifically female version of heroism, which I have shown to be embodied in second wave action heroines and is characterised by the hybridity of masculinity and femininity. Some may argue that a female hero should not be different from a male hero, as this perpetuates gender difference, and some, such as Hye-Won Han and Se-Jin Song (2014:45), contend that a female hero simply following a male hero model narrative and possessing his characteristics reinforces a patriarchal system. In fact, for Han and Song (2014:28), a 'true' female hero in popular culture is yet to emerge. Although the search for 'true' heroineness is an essentialist project, I hold that at least an archetype of female heroism that does not perpetuate gender difference, but also does not simply mimic the archetypal male hero, can be found, as I have shown, in sci-fi film and television produced during feminism's second wave.

Recent feminist literature and representations of female action heroines also seem to embrace the notion of complex, hybrid characters that do not sustain the masculine/ feminine dichotomy. In a very recent publication, titled Fourth Wave Feminism in Science Fiction and Fantasy (2019), Valerie Estelle Frankel introduces an extensive list of recent heroines in films that are desexualised and capable, and one can argue, androgynous as Ripley, Connor and Janeway are, yet also embrace notions of motherhood and femininity. Although this is scope for future investigation, Frankel (2019) also points out that contemporary heroines are often also represented in intertextual terms, consisting of various races, cultures and sexual orientations, which aids in their construction as hybrid characters. It may seem that the original action heroine archetype could be returning in popular culture, and that these contemporary characters may also be heroines in terms of the definition put forward in this paper.

Conclusion

Ellen Ripley, Sarah Connor and Kathryn Janeway, who appeared as the second wave feminist 'ideal power women' (Knight 2010:186), all possess characteristics traditionally associated with both masculinity and femininity, and as I have shown, it is the successful hybridity of these traits that become the source of their heroism. I reiterate that it is these heroines' hybridity of masculinity and femininity that makes them heroines, rather than rudimentary copies of the male hero, or simply a male hero in a female body. Moreover, these three characters are symptomatic of a Zeitgeist where second wave feminism had a notable impact on the representation of women in the media. As such, Ripley, Connor and Janeway embody ideals of both early liberal and cultural feminism, which in themselves seem to contradict one another. In embodying the values of both seemingly opposing feminisms though, a heroine archetype is constructed.

Notes

1. Feminist film criticism by authors such as Laura Mulvey (1975) and Claire Johnston (1973) undeniably also impacted women's representations in popular cinema.

2. I am aware of the debates surrounding the use of 'waves' as a useful way to categorise the various feminisms, however, I use the wave metaphor in this essay, and its debate is beyond the scope of this paper.

3. I use the terms "female qualities" or "feminine features" to refer to characteristics traditionally associated with women; I am aware that ascribing certain qualities to exclusively to women and others to men perpetuates essentialist notions of gender. However, these terms are useful for the arguments I make here.

4. Han and Song (2014) refer to the new version of Lara Croft in their analysis, however, a similar argument can be made about the original action heroine.

References

Bach, S. & Langer, J. 2010. Getting off the boat: Hybridity and sexual agency in the Alien films, in Meanings of Ripley: The Alien Quadrilogy and Gender, edited by Elizabeth Graham. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing:79-98. [ Links ]

Battlestar Galactica. 1978-1979. [Television programme]. NBC Universal Television Distribution. [ Links ]

Bowring, M.A. 2004. Resistance is not futile: Liberating Captain Janeway from the masculine-feminine dualism of leadership. Gender, Work and Organization 11(4):381-405. [ Links ]

Bradley, H. 2007. Gender. Cambridge: Polity Press. [ Links ]

Caldwell, T. 2010. 'Aliens': Mothers, monsters and marines. Screen Education 59:125-130. [ Links ]

Cavallaro, D. 2003. French Feminist Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: Continuum. [ Links ]

Cameron, J. 1984. The Terminator. [Film]. Orion Pictures. [ Links ]

Cameron, J. 1986. Aliens. [Film]. Brandywine Productions. [ Links ]

Cameron, J. 1991. Terminator 2: Judgment Day. [Film]. Carolco Pictures. [ Links ]

Cixous, H. & Clément, C. 1987. The newly born woman. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

De Beauvoir, S. 2011 [1949]. The second sex. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

De Gaia, S. 1998. Intergalactic heroines: Land, body, and soul in Star Trek: Voyager. International Studies in Philosophy 30(1):19-32. [ Links ]

Di Risio, P. 2015. Post-human humanity in Alien: Resurrection. Deletion 9. [ Links ]

Doctor Who. 1963-1989. [Television programme]. BBC Studios. [ Links ]

Dove-Viebahn, A. 2007. Embodying hybridity, (en)gendering community: Captain Janeway and the enactment of a feminist heterotopia on Star Trek: Voyager. Women's Studies 36:597-618. [ Links ]

Evans, J. 1995. Feminist Theory Today: An Introduction to Second Wave Feminism. SAGE: London. [ Links ]

Faithful, G. 2016. Survivor, warrior, mother, savior: The evolution of the female hero In apocalyptic science fiction film of the late cold war. Implicit Religion 19(3):347-370. [ Links ]

Fincher, D. 1992. Alien 3. [Film]. Brandywine Productions. [ Links ]

Graham, E (ed). 2010. Meanings of Ripley: The Alien quadrilogy and gender. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars. [ Links ]

Han, H. & Song, S. 2014. Characterisation of Female Protagonists in Video Games: A Focus on Lara Croft. Asian Journal of Women's Studies 20(3):27- 49. [ Links ]

Hansen, J. 2000. There are two sexes, not one/Luce Irigaray, in The French Feminism Reader, edited by K. Oliver. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 1991. A cyborg manifesto: Science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century, in Simians, cyborgs and women: The reinvention of nature. Routledge: New York:149-181. [ Links ]

Helford, E.R. 2000. Postfeminism and the female action-adventure hero: Positioning Tank Girl, in Future females, the next generation: New voices and velocities in feminist science fiction criticism, edited by MS Barr. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield:291-308. [ Links ]

Huyssen, A. 1986. After the great divide: Modernism, mass culture, postmodernism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Innes, S. 1999. Tough girls: Women warriors and wonder women in popular culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [ Links ]

Jeunet, JP. 1997. Alien: Resurrection. [Film]. Brandywine Productions. [ Links ]

Johnston, C. 1999 [1973]. Women's cinema as counter-cinema, in Feminist Film Theory: A Reader, edited by S Thornham. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press:31-40. [ Links ]

Knight, G. 2010. Female action heroes: A guide to women in comics, video games, film, and television. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. [ Links ]

Lang, F. 1927. Metropolis. [Film]. UFA. [ Links ]

Lathers, M. 2010. Space oddities: Women and outer space in popular film and culture, 1960-2000. New York, NY: The Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Mero, G. 2018. Kathryn Janeway Boldly Going. [O]. Available: https://futurism.media/kathryn-janeway Accessed 1 June 2019. [ Links ]

Mulvey, L. 1975. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen 16(3):6-18. [ Links ]

Newton, J. 1980. Feminism and anxiety in Alien. Science Fiction Studies 7:293-297. [ Links ]

Pinterest. Ellen Ripley Alien 3. [Sa]. [O]. Available: https://za.pinterest.com/pin/61713457367104485/?lp=true Accessed 13 October 2018. [ Links ]

Rich, A. 1986. Of Women Born. W.W. New York: Norton and Company. [ Links ]

Scobie, S. 1993. What's the Story, Mother?: The Mourning of the Alien. Science-Fiction Studies 20:80-93. [ Links ]

Scott, R. 1979. Alien. [Film]. 20th Century Fox. [ Links ]

Scott, R. 1982. Blade Runner. [Film]. The Ladd Company. [ Links ]

Shaw, D.B. 2006. Sex and the single starship captain: Compulsory heterosexuality and Star Trek: Voyager. Femspec 7(1):66-85. [ Links ]

Star Trek: The Original Series. 1966-1969. [Television programme]. NBC. [ Links ]

Star Trek: Voyager. 1995-2001. [Television programme]. UPN. [ Links ]

V. 1984-1985. [Television programme]. NBC. [ Links ]

Vadim, R. 1968. Barbarella. [Film]. Paramount Pictures. [ Links ]

Wagoner, M. 2016. In Defense of Linda Hamilton Arms - Because, It's Judgment Day. [O]. Available: https://www.vogue.com/article/terminator-linda-hamilton-best-arms-sarah-connor-workout-biceps-triceps Accessed 5 June 2019. [ Links ]

Wood, P. 2010. Redressing Ripley: Disrupting the Female Hero, in Meanings of Ripley: The Alien Quadrilogy and Gender, edited by Elizabeth Graham. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing:32-59. [ Links ]