Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Image & Text

versão On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versão impressa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.34 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a4

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a4

The Big Druid's photographs of trees: Art and knowledge

Suzanne de Villiers-Human

Department of Art History and Image Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa Humane@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

This article argues that the world-renowned multi-media artist, Willem Boshoff's, digital image gallery of photographs of trees, flowers and plants on the digital domain of the internet and in his digital archive, forms part of a history of efforts by modern artists to dismantle and stage the reductive divisions between the arts and the natural sciences. By emphasising their agency to richly interweave layers of cultural meaning and ideological questioning, while producing cascades of other images, the objective is to situate the botanical photographs in Boshoff's digital "image gallery" in an expanded history of imaging, and to explore the layered perspectives that this positioning may entail and divulge. The interpretation includes comparative visual material from atlases and other image galleries, landscape art and land art, photographic and cinematic images, diagrams and scientific "illustrations", Druid Walks and performances, and so forth. The interpretation ventures to fathom the aesthetic, artistic and cultural significance of this body of photographs, as well as their power to ignite debates on the relationship between art, science, knowledge, wisdom, politics and culture.

Keywords: Art, science, knowledge, wisdom, image atlas, photographs of trees.

Introduction

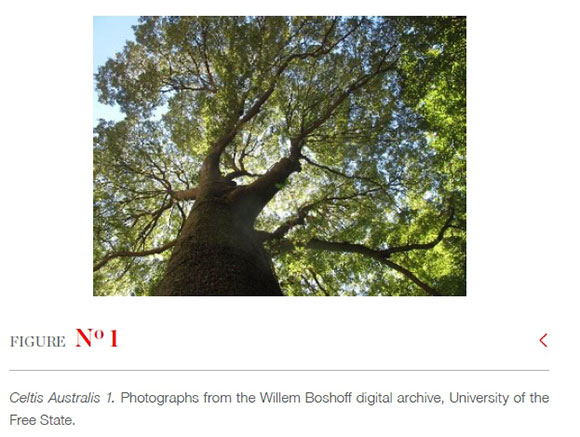

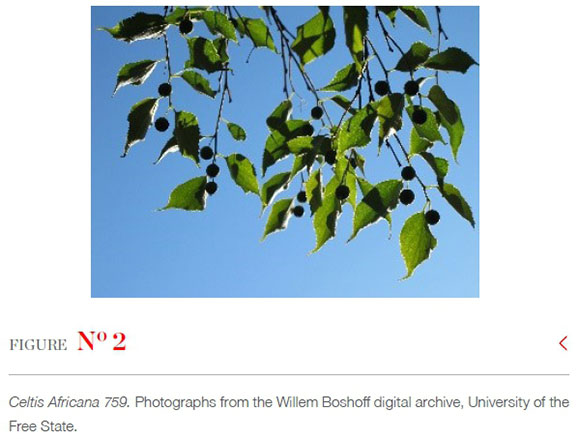

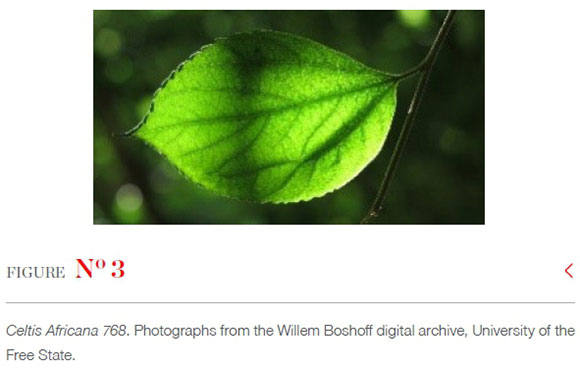

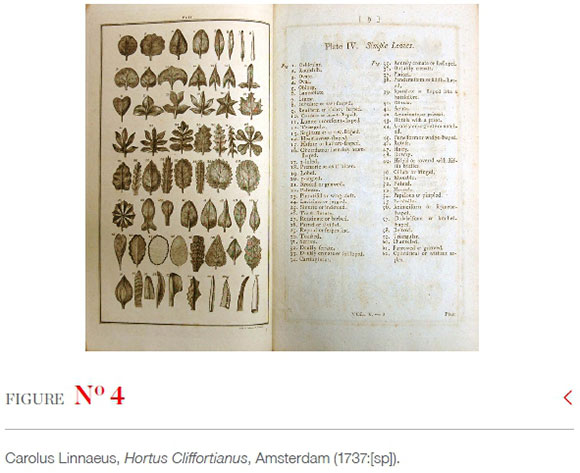

On the World Wide Web and on the database made available on-site in the Willem Boshoff Digital Archive on the campus of the University of the Free State in Bloemfontein, South Africa,1 viewers can retrieve considerable numbers of colour photographs of a large variety of catalogued specimens of trees, plants and flowers, shot by Willem Boshoff from diverse angles, at various times of the day, and taken in various regions of South Africa and the world. There are tens of thousands of these colour photographs by now (for example, Figures 1, 2 & 3). Together, they constitute a photographic image gallery on the digital domain of the internet,2 which could be deemed a con-temporary version of botanical atlases of engravings, drawings and paintings of trees, plants, insects and other objects of nature, reproduced in book form, which proliferated in Europe since the sixteenth century, for instance in the eighteenth century Hortus Cliffortianus by Carolus Linnaeus (Amsterdam, 1737, Figure 4), to whom Boshoff often refers (Gentric 2004). Comparable to these historical tomes, Boshoff's digital image gallery of colour photographs continues the tradition of a systematic compilation of "working images" or scientific instruments, which enable researchers and nature enthusiasts alike to find, identify and name trees. Scientific atlas-making has been a central practice across the disciplines of the natural sciences since the sixteenth century. During the twentieth century, comparable "scientific" or pseudo-scientific practices - initiated by artists such as Marcel Duchamp and subsequently manifesting as for instance 'archive fever' (Derrida 1995) and as the 'archival impulse' (Foster 2004) in the Fine Arts - began to permeate the arts (with specific reference to trees and environmental art, in the work of Rachel Sussman, Emma Livingstone, Sabastaio Salgado, Marc Hirsch, Beth Moon and Gerhard Richter, for example). If this twentieth century phenomenon is construed (as it is by me) as a belated and mischievous reaction to the way in which the arts and natural sciences had been pried apart since the mid-nineteenth century (Daston & Gallison 2010), Boshoff's digital image gallery of photographs could be part of a history of efforts by modern artists to dismantle and stage the reductive divisions between the arts and the natural sciences.

The striking gallery of catalogued nature photographs by a world-renowned multimedia artist - often reductively described as a conceptual artist3 - sparks the questions: How is this body of "documentary" photographs related to his larger oeuvre of art works, including Druid Walk performances, land art, sculptures, sculptural installations, drawings and so forth? Are we supposed to appreciate them in terms of the historical conventions of artistic landscape, land and performance art and compare them with the work of contemporary and historical artists? Or, could Boshoff's botanical digital image gallery be appreciated in terms of a history of images of science? More articulately, do these rich photographs not beg for the integration of these questions in terms of Image Studies,4 to ask: What is the image-historical relevance of the shifting historical relationships of the division between "artistic" and "scientific" pictures in the interpretation of these photographs?

In recent times, in the context of Image Studies, imaging is cherished as 'epistemic agent' (Marr 2016), as 'cultural technique' (Bredekamp 2010; 2018), as a tool for speculative model building (Daston & Galison 2010), rather than merely as illustrative device. Images are experienced as passages or portals or cues (Elsaesser 2013) for sensing and probing during processes of changing, while picturing. They are valued for their capacity to present, rather than to represent (Elkins 1995). This has not only transformed our perceptions of the ways in which science is pictured, but has also enabled a more refined differentiation and articulation of the various powers of artistic images (Boehm 2007; 2008; 2010; 2012), for instance their capacity to point to (Zeigen), to witness and persuade or provide evidence (Bildevidenz), to affect or to criticise as instruments of knowledge (Bildkritik), and so forth.5

Already in 1979, Paul Ricoeur queried artificial divisions in perceptions of knowledge acquisition, between the natural and the cultural sciences when he explored the notion of 'fiction' in his essay 'The function of fiction in shaping reality'. He introduces the idea of a 'productive imagination' and explains: images may be seen to have the agency to shape reality. He argues that 'imagination is "productive" not only of unreal objects, but also of an expanded vision of reality' (Ricoeur 1979:128) and that 'iconic augmentation' (used by him in a figurative sense, rather than referring to pictures), performs the labour of augmenting while abbreviating, condensing while developing reality and thus offers transformed or transfigured models of perceiving the world (Ricoeur 1979:136). Ricoeur (1979:126) invents the concept of 'iconic augmentation', because 'fictions' to him do not refer in a 'reproductive' way to reality as already given, but they may refer in a 'productive' way to 'reality as intimated by fiction'. This function of 'fiction' to invent, discover, change, increase and extend reality, has since been associated with imaging in the natural sciences. In their historical differentiation of ways of scientific seeing, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison (2010:383) tentatively characterise current understandings of scientific imaging as 'image-in-process' where images 'function at least as much as a tweezer, hammer, or anvil of nature: a tool to make and change things'.

My aim is to explore the agency of Boshoff's beautiful but seemingly anodyne documentary photographs of punctiliously examined trees, beyond the usual contexts of scientific "images at work" in atlases, in an expanded context of sophisticated imaging, including art. By emphasising their agency to richly interweave layers of cultural meaning and ideological questioning, while producing cascades of other images, I endeavour to situate the botanical photographs in Boshoff's digital "image gallery" in an expanded history of imaging and to explore the layered perspectives that its positioning within such an extended history of images may entail and divulge. This includes comparative visual material from atlases and other image galleries, landscape art and land art, photographic and cinematic images, diagrams and scientific "illustrations", Druid Walks and performances, and so forth. I probe the heuristic value of contextualising them amidst the historically changing relationships between artistic and scientific imaging evident for instance in the work of Leonardo da Vinci and Marcel Duchamp. The aim of this article is to investigate the scope and nature of these botanical pictures by comparatively analysing a select few. Such an interpretation ventures to fathom the aesthetic, artistic and cultural significance of this body of photographs, as well as their power to ignite debates on the relationship between art, science, knowledge, wisdom, politics and culture.

Why trees?

Among the botanical pictures in Boshoff's digital image gallery, I concentrate on his photographs of trees. This is partly because the tree photographs are so abundant, but also because the tree copiously figures in the rest of Boshoff's oeuvre in diverse metaphorical and material contexts. Many of his artworks are thus related to the body of botanical photographs as well as to the processes involved in making them: the acquaintance he makes with each photographed tree while picturing it and his reflections on these processes. Boshoff expresses it thus (Perryer 2007:4):

I am awestruck by trees and, to a large extent dependent on them, not only for their great wooden material but also for ideas. My father, a carpenter, supported us by working with wood. As an artist, I give preferential treatment to wood for most of my sculptures. Many of my works deal with paper as a sacrificial product of the slaughtered tree. In the 1980s I was chairman of the Dendrological Society, Southern Transvaal branch, where I spent numerous week-ends studying trees scientifically. For the last 25 years, I have extended the study of trees and other plants to botanical venues all over the world and these activities led me to make three massive "Gardens of Words".

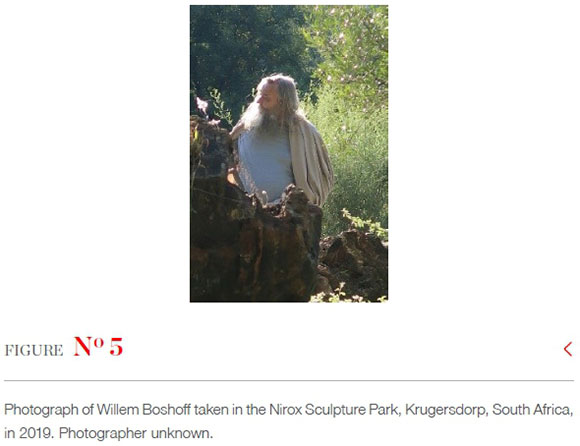

Examples of art works in his oeuvre directly related in some way to trees are: Tree Walk (2007), Tafelboek (1975), Kasboek (1980), House of Herbs (2011), Highveld (2011), Garden of Words III, IV (1982-1997), 370 Day Project (1982- 1983), Tree of Knowledge (1997), Bloeiselplas, Bottled Hope (1995), Black Christmas (2009), Annuloid, Touch Wood (2012), Burning Bush (2011), All Flesh is Grass (2011), as well as some 'early work in wood' on his website and his research on and works about tree nymphs. One could argue that the gallery of photographs is the result, as well as the cause of his art-making and performances, and that especially his research for his early works 370 Day Project (1982-1983) and Garden of Words (1982-1997), were intimately related to it.6 As the son of a carpenter, Boshoff possesses profound transmitted knowledge of wood types. He is also a self-styled Druid. Boshoff assumed the persona of the Druid7 for himself to incorporate especially his passion for trees and plants with his many other interests, including books, words, stones, pebbles, sand and music -interests which are all well-represented in his digital archive. Druids, admittedly, were an ancient Celtic order of priests, diviners, teachers and magicians and in Greek 'drus' means 'oak tree', but Boshoff insists that he reinterprets the typical Stonehenge version of the Druid into his own persona as 'an African outsider who creates, collects, ponders and sometimes comments' (Boshoff 2009:1). This cultural ambiguity is suggested in a recent photograph taken of Boshoff draped in a blanket (2019), in the Nirox Sculpture Park (Figure 5). According to Boshoff, both the words 'inyanga' (in Zulu a traditional healer) and 'druid' mean 'man of trees' (Boshoff 2009:1).

His gathering together of trees in a gallery, forms an imaginary world comparable to a wood, and the persona of the Druid organises his oeuvre, just as his digital archive of documented works and research in various fields systematises randomness into accessible knowledge. His appropriation of the persona of the Druid, which stems from an era before the separation of science and art and which is closely associated with trees, thus predisposes the interpretation of this body of tree photographs. The profundity of his contemplation, at an early stage in his career, on the meaning of trees as instruments of the revelation of all-encompassing knowledge, or wisdom, is evident from a paragraph in his Masters' dissertation:

Die aardsboek van alle boeke is die 'Boom van Kennis van Goed en Kwaad'. Dit is hierdie boom waarvan 'alle papier' gemaak is, waarop 'alle boodskappe' uitgekerf is, waarvan mikstokke gesny is vir boodskapperdraers, waaruit 'alle kerfstokke' kom waarmee nog ooit telling gehou is. Die boom is die moeder van die letterkunde. Die rol wat hierdie boom speel met die ontbloting van kennis is allesomvattend. (The earthly/arch-book of all books is the 'Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil'. It is from this tree that 'all paper' is made, upon which 'all messages' are carved, from which cleft sticks for messengers were cut, from which 'all notch sticks' come with which score is kept. The tree is the mother of literature. The role that this tree plays in the revelation of knowledge is all-encompassing) (Boshoff 1984).

Boshoff's intimation of this profound potential, gift or promise, inherent to trees, to impart wisdom, and his knowhow to aesthetically enhance or harness this in pictures, images, photographs and art works involving trees, I will argue, is visible in Celtis Australis 1 (Figure 1).8 In the following analysis, I point to several key aspects that characterise Boshoff's interest in and observation of trees, which I scrutinise and develop with reference to other art works and pictures.

One photograph analysed

Celtis Australis 1 (Figure 1) is a photograph discernibly taken by an artist who is not in the ser vice of a botanist, as earlier "illustrators" of botanical atlases used to be. At work here, rather, is an artist expertly knowledgeable about trees. Since the nineteenth century, a distinction was increasingly drawn between artistic craftsmanship and scientific-technical knowledge, and scientists became associated rather with photographers, than artists and illustrators as before. Since the seventeenth century, atlases were the dictionaries of the sciences of the eye which trained the eye to pick out certain kinds of objects as exemplary, guiding to what is worth looking at, how it looks, and how it should be looked at. They provided the definitive, set standards, how to describe, depict and see (Daston & Gallison 2010:22). As substitutes for natural specimens in the systematic compilations of standardised 'working objects' in atlases, pictures enabled natural scientists to generalise, compare, and to train and calibrate the eye, with reference for instance to the graphic depictions of leaf shapes as in Carolus Linnaeus' Hortus Cliffortianus (Amsterdam, 1737) (as seen in Figure 4) (Daston & Gallison 2010; Ford 2014). Therefore, in the era of scientific objectivity the new photographic apparatus with its aura of technical impartiality increasingly replaced handcrafted pictures. The seemingly merely mechanical procedure of photography had split de-piction from signification.

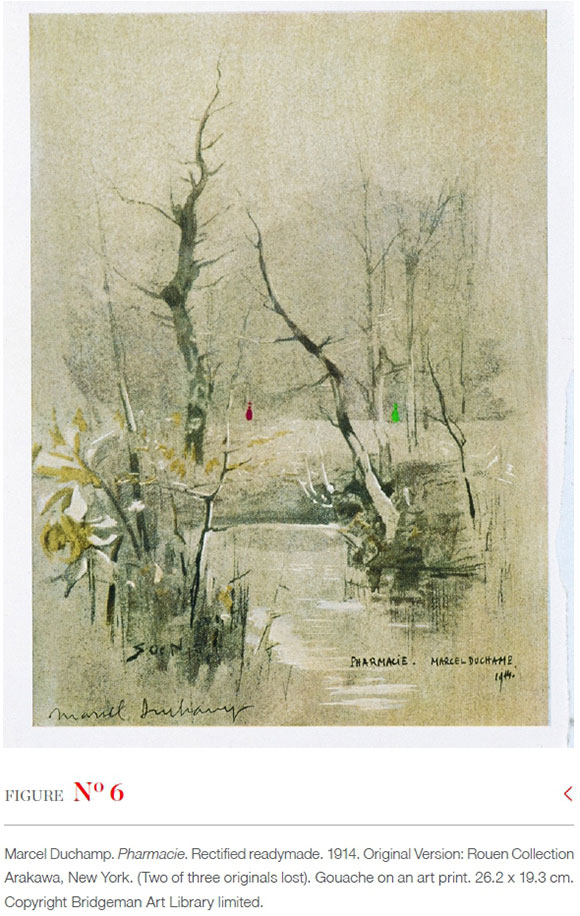

Early in the twentieth century, however, in order to counteract photography's undermining influence on the principle of mimesis in art, the Cubists, and subsequently Duchamp, created the first tableaux-objets through imaginative processes of active invention, synthesising seeing and knowing, in order to invent pictures which were able to interrogate in the process of attaining knowledge. Duchamp and other Dadaist artists (to whom Boshoff has a special attraction) ventured to replace "retinal art" with what may be described as visual thinking, or conceptual picturing, often with reference to research in the natural sciences. In the history of imaging nature, one of the most important traditions is landscape art and Duchamp was one of the early artists of the twentieth century to self-consciously re-assess the genre as it had developed.

Landscape art

Duchamp's Pharmacie (1914) (Figure 6) exposes the modern crisis in the genre of landscape art at a time when the role of the horizon was being questioned. In this "corrected readymade" of a trivial watercolour painting (bought in a shop for artists' materials) of a winter landscape with trees which seems fit to decorate a calendar, he added onto the horizon, a spot each of red and of green paint. These two coloured blobs were reminiscent to him, of the lights in the windows of French chemist shops, serving to attract attention at night. For Duchamp the pharmacy lights had an aura of melancholy, loneliness and ailment among shop windows with exhibited commerce - from the perspective of a nocturnal flaneur of the city streets. Red and green pharmacy lights (Molderlings 1987:223-225) now seem to shine from the horizon through the trees of the dreary winter landscape, transferring the distanced viewer into the city streets. The genre of landscape painting was established during the seventeenth century, concomitantly with the establishment of the natural sciences as scientific disciplines with their objectifying stance towards nature. The horizon was a primary feature of landscape art as it developed then, when landscape was looked upon (Draufblick), or looked horizontally through (Durchblick). Subsequently, modern art questioned this perspective on the landscape by rediscovering what it entails to be surrounded by nature, to be enfolded by heaven and earth through detailed insider knowledge (Einblick), as in the work of Claude Monet, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian and others (Boehm 1986; 2007). Comparably, Boshoff's photographs, produced by a handheld camera, are deliberate interpretative interventions, I wish to argue, which open up new critical debates about art and knowledge and their related function in society.

The Druid-artist's positioning of the camera in Figure 1 draws attention to his personal relationship, or more generally, a human relationship with the tree. The camera man is close to, maybe in awe of this gigantic, ancient, living being illuminated from its top, from within the depth of the picture. In this position, the shared uprightness of the tree and the human body is brought to mind. However, in the depth of the picture the blue of the sky reveals the existence of a shifted metaphysical horizon, which suggests what is hidden to the empirical gaze past the picture plane. While the sunlight, which seemingly comes from beyond the picture, uncovers, makes transparent or delineates the respective observable details of leaves, branches and trunk, it also suggests the revelatory light of heaven; an alternative light of wisdom beyond ordinary vision.9 This experience of rootedness and being surrounded by an overarching cosmos is a rediscovery of dimensions of the landscape which is overlooked when landscape is regarded as being looked upon or when landscape art depicts a horizontal gaze through the landscape (Boehm 1986; 2007). Similarly, in Piet Mondrian's series of depictions of trees (another artist admired by Boshoff) the horizon is gradually and confusingly lost.

The photograph in Figure 1 shows a personal relationship with a tree in other ways too. It is one picture in a gradual process of familiarisation and acquaintance; of getting to know it as if from scratch, from various stances and distances (Figures 2 & 3), thus producing a variety of photographs of the same species of a tree. In this specific instance (Figure 1), light directs the point of view or stance of the photographer, because the camera lens must be shielded from direct sunlight. According to Boshoff (in personal conversations), the time of day at which he arrives at a specific tree to be pictured, cannot be predicted. Therefore, the light shining upon the tree is a gift of a specific time and place which cannot be changed and to which the artist-photographer-participant must adapt and for which he must be thankful. Instead of controlling or imposing knowledge upon the tree, the photographer lets himself be enfolded by it as an instrument of revelation. Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1993 [1961):129) describes this meeting ground of humans in relation to nature with reference to trees, in 'Eye and Mind' where he writes: 'As Andre Marchand says, after Klee:'

In a forest, I have felt many times over that it was not I who looked at the forest. Some days I felt that the trees were looking at me, were speaking to me... I was there, listening... I think that the painter must be penetrated by the universe and not want to penetrate it ... I expect to be inwardly submerged, buried. Perhaps I paint to break out (Merleau-Ponty (1993 [1961):129).

For Boshoff, both camera and picture become tools which mediate the engagement between himself and his environment.

Tools and collecting

Not only are the camera and pictures revelatory tools for Boshoff, but the process of collecting pictures - like this gallery of photographs - is in this sense a cultural technique which opens up new perspectives on nature. This collection of pictures, because it comprises of material and technical skills, aptitudes, rites and practises that provide the foundation for innovative thinking, thus qualifies as a cultural technique according to Geoffrey Winthrop-Young (2013) and Horst Bredekamp and Sybille Krämer (2013).

In this respect, Boshoff's plant collection at his home in Kensington,10 Johannesburg, is of special interest. His caring and disciplined relationship with plants materialises as a watering routine, their transplantation into pots of various sizes, the furnishing of water holes for their pots, moving pots into the sun or shade, and generally attending to each plant in multiple ways - watching over it to produce buds, to flower, to open, photographing it repeatedly and waiting for the sun to provide the right type of light from the right angle. This discipline predicts the ways in which Boshoff would design performative briefs or remits for himself according to which he would photograph or produce works of art (for instance the 370 Days Project) in a patterned, scheduled and self-regulating way.

As a collector, Boshoff has a conspicuous proclivity for tools, but on closer inspection it could be asserted that he employs and regards collections themselves as tools or cultural techniques. Exhibiting sections of larger collections (as in this case of photographs from the Tree Walk discussed below) in new contexts, as discrete artworks, is a common practice in Boshoff's oeuvre. In this sense, the image gallery of tree photographs could be compared to Boshoff's other collections of, for instance, words in various types of dictionaries, or of objects such as stones, spoons or scissors which often find their way into individual artworks. Boshoff's interest in the aesthetics of tools of craft and his almost obsessive attention to workmanship, skill and finish in his art works testify to his faith in the capacity of cultural techniques to open up new exploratory spaces for perception, communication and cognition.

In his chapter 'The poetics of tool use. From technology, language and intelligence to craft, song and imagination', Tim Ingold (2000:481) compares the novice practitioner of a musical instrument with a scientist, 'who confronts nature in rather the same questioning way that the novice player confronts his instrument, as a domain of oc-current phenomena whose workings one is out to understand'. The use of tools to acquire knowledge in this phenomenological sense is also described by Ingold (2000: 72) in terms of early nomadic hunting practices:

the weapons of the hunter, far from being instruments of control or manipulation, serve this purpose of acquiring knowledge. Through them the hunter does not transform the world, rather the world opens itself up to him ... In short, the hunter does not seek, and fail to achieve, control over animals: he seeks revelation.

The manifestation of a personal relationship between artist, observer, participant and the tree, by the use of a camera, a photograph of a tree, and a collection of photographs of trees, challenges habitual ways in which knowledge is construed to be acquired through a division of mind, hand, and senses.

Knowledge-making

By being enfolded and actively taking part in the tree's disclosure or "revelation" of itself (see Figure 1), there is no separation between understanding and doing. Rather, in these photographs, sensing, perceiving and understanding are visibly conjoined in a fundamental way. The process of taking the tree photographs is an artistic practice of knowledge-making which integrates and interweaves techné at various levels in the picture. In this way, the tree photographs not only impart botanical knowledge, as well as imply diverse stances towards the relationship of humans and nature, as in landscape art, but also interrogate the foundations of knowledge and the boundaries between the arts and the sciences.

Although the photograph implies an "artist's stance" towards nature, it additionally affords a detailed or "scientific" observation of the discernible attributes of the specific species. This includes features such as its typical elephantine bark, clearly visible in the foreground of the photograph (Figure 1), its umbel-shaped crown, or rounded broad canopy, shaped by branches protruding like umbrella ribs, on the evidence of which this species can be named and catalogued. Most importantly, however, while being useful to botanists, it simultaneously draws knowledge of botanical items into wider cultural awareness from which botanical images have become isolated, because of artificial divisions among scientific disciplines. In what could be seen merely as a botanical document, the artist makes the viewer of the photograph aware of an underlying order of the cosmos as a shaping force of meaning, as Ricoeur (1979) has intimated with the concept of 'fiction'. Boshoff's tree photographs, by referring to, and even taking over, the function of scientific atlas images, endeavour to restore the function of art to convey embedded knowledge. In this way, his photographs constitute a challenge to the positivistic conception of what the natural sciences are. By recognising the alleged weakness of images in being subjective, their strength is proclaimed. Thus, by intruding upon and then subverting biases in the domain of the natural sciences with his atlas photographs, the scientific photographer in the guise of a Druid (a persona of pre-historic origins), succeeds in elevating or questioning the epistemological complexity of natural scientific discourse.

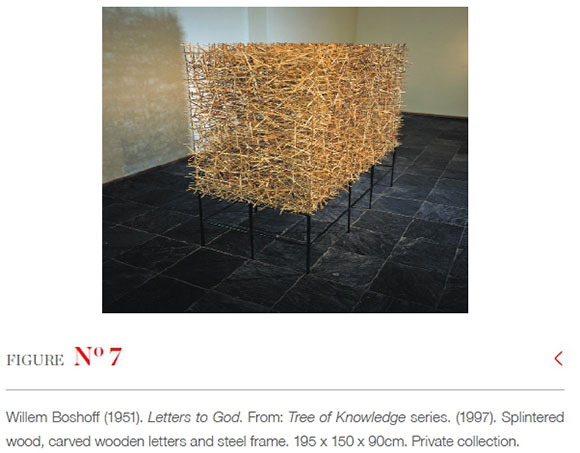

In the photograph in Figure 1 the umbrella-like relationship between trunk and branches, is shown to be repeated in the sub-division of bunches of smaller branches sprouting from the ends of branches in turn, and the similarity of this relationship is made clear from the chosen point of view. In the history of knowledge, it seems to have been natural to impose the branching structure of trees onto discourse and even onto knowledge itself, in the form of tree metaphors (Eco 2014). Peter Burke (2016:61) in his book What is the history of knowledge? observes that; 'Debates about clas-sification in particular disciplines were extended, almost inevitably, to knowledge itself, often imagined as a tree with many branches'. Boshoff's interest in relationships and connections rather than divisions among various disciplines (through the Humanities and Natural Sciences) in his digital archive, makes the tree and this sense of natural order that it imparts, an apt metaphor for knowledge itself, in his oeuvre. The tree depicted in Boshoff's photograph (Figure 1) as at once rooted and reaching towards the sky, projects an horizon or opening limit which shapes the expected inherent coherence that he projects onto the world. For Boshoff the grasping together of fragmented knowledge in a system to organise and rediscover wisdom once again, is indispensable and imperative after the dispersion and shattering of knowledge in the Garden of Eden and Babel (see for instance Tree of Knowledge (1997) in Figure 7). Whereas for Walter Benjamin this tragic scattering into fragments prompts a mournful restoration process, for Boshoff there is no melancholy in his ardent urgency to salvage meaning.

Indeed Boshoff's archive and oeuvre present themselves as an incessant gathering together of splintered knowledge with the tree, wood splinters and chips of wood as recurring motifs in his art works - as in Tree of Knowledge (1997) (Figure 7) (Van Wyk 2018). Boshoff emphasises that he does not allow himself to add a tree or plant to his catalogue of species, unless he has touched, scratched, crushed, smelt, scrutinised, and experienced it first-hand, after which he memorises the taxonomic details in Latin. Boshoff thus adds the name of a particular item to his collection in order to salvage it from extinction from human memory, in Latin, the lingua franca for the dispersion of such knowledge. This calls into being communities of observers, scientific communities or collectives of experts over centuries and across countries. His gallery of photographs of trees thus functions as an intrinsically social endeavour and as a mnemotechnic device or cultural technique to remember the names of the genus and species of a vast array of trees, not confined to South Africa. Boshoff's passionate cataloguing of hundreds of trees in photographs over many years suggests an urgency that these trees could somehow elude human consideration, be lost from memory or become extinct.

Time

His project of documentation is insistently aware of the passing of natural and cultural time and changing circumstances, in contrast to which the abundance of the pictures in the project bestows a sense of constancy and endurance to resist the devastation of the passing of time. His three existing expansive Gardens of Words projects (a fourth in the making), presenting thousands of species, and his careful tending to the plants in his garden, attest to this. The unified project of taking botanical photographs is therefore open-ended. The continuous growth and development inherent in the life span of living creatures such as trees, necessitate that Boshoff makes his ritual acquaintance with them anew each time, even when he journeys to the same tree more than once. Therefore, the usual metaphor of the tree denoting unity, structure and hierarchy (Deleuze & Guatari 1988) is tempered by an idea comparable to Goethe's 'transforming form' deriving from Goethe's notion of the Urpflanze, which is a natural form that is inherently transforming. Neither Boshoff's reiteration of one species of tree in several photographs nor the repeatable rhythms of nature, inhibits the incom-pletion of Boshoff's digital image gallery in its endless variety and transformations. In Boshoff's limitless series of photographs the trees are never static, but air and changing light animate them against the sky to make leaves reflect, gleam and shimmer. The transforming effects of time become almost cinematically present in reiteration, as in Dziga Vertov's (1929) self-reflective film Man with a Movie Camera. In this film, to reflect on the new medium of the moving image on projected screens, the tree, animated by wind and light (Figures 8 & 9), together with the metaphors of the flowing surface of water, and the shifting clouds against the sky, becomes a recurrent motif which metaphorically refers to the cinema screen itself where images unfold and transform in time. The abundance and inherent animation of Boshoff's photographs of the same tree at different times of day and season, seem to protest comparably in buoyant or hopeful fashion, against the arresting qualities of the photographic medium.

Diagram

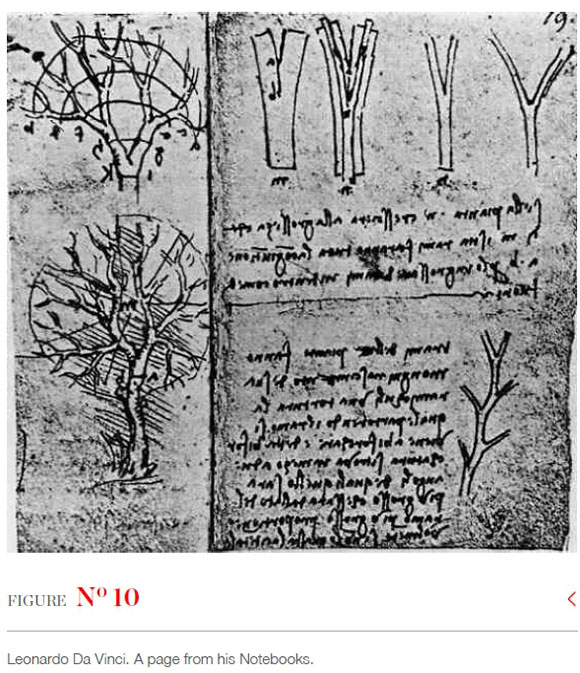

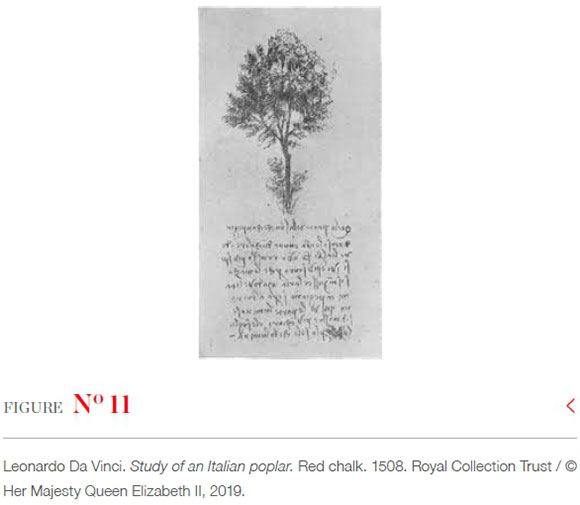

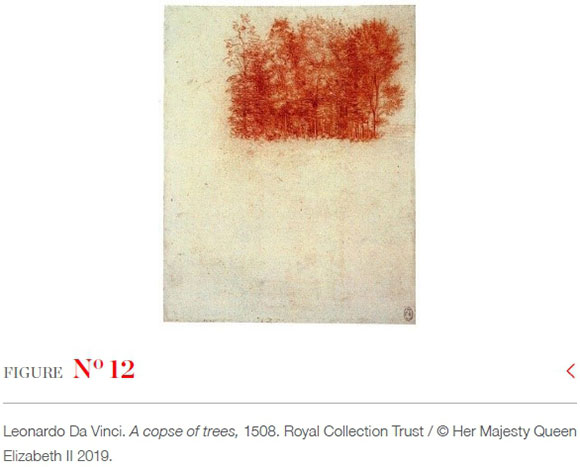

In the history of imaging nature, the most important traditions are landscape art, on the one hand, and scientific imaging in for instance atlases and diagrams, on the other. In comparison with each other, each of these image types present a distinguishable range of vision or horizon of expectation. However, science images are currently accorded much more indeterminacy and potentiality (Huppauf & Weingart 2011; Daston & Gallison 2010), so that the line separating the sciences and the arts is shifting once more. According to Gottfried Boehm (2007:114; Frank & Lange 2010:23) arguments for the exclusion of the 'diagram' in an extended history of images in Bildwissenschaft is a consequence of the old antagonism between 'cognitive knowledge and aesthetic experience'. A diagram, according to John Bender and Michael Marrinan (2010:14), is in essence a tool of research, by means of which correlations are made visible, by formalising relationships in the world and producing an experience that cannot be reduced to a single point of view. Some diagrams dictate a dominant point of view, while some are situated in the world like objects: they foster many potential points of view, from several different angles with a mixed sense of scale that implies nearness alongside distance. Otto Benesch (1943:326) argues that Leonardo da Vinci inaugurated a new understanding of visualising reality by empathetic observation, freed from preconceived inner images, and that he stands at the beginning of diagrammatic scientific drawing: 'With Leonardo begins the importance of drawing as diagram of technical and scientific conclusions and statements'. For Da Vinci, the first artist to sketch and draw in the open air, drawing was a primary means to convey knowledge in the empirical sciences. Leonardo writes (cited in Benesch 1943:318) that if you want to describe nature in words, 'the more you will confuse the mind of the reader and the more you will prevent him from the knowledge of the thing described. And so it is necessary to draw and to describe'. In the work of Leonardo (Benesch 1943:311) his penetrating research of natural objects is transformed and developed into an aesthetic experience, because of his deep understanding of the functions and shapes of the separate parts (Figures 10 & 11). In a meticulous study, in Windsor Castle (Figure 11), of the branching structure of an Italian Poplar, drawn in red chalk, the artist shows for instance the discovery he had made that the age of a tree can be computed from the number of the main shoots of the branches arranged in concentric layers (Benesch 1943:316). Leonardo's finely rendered copse of birch trees in red chalk from 1508 (Figure 12) in the top corner of a page of one of his notebooks, on the other hand, succeeds in combining the nearness of the experience of tactility of feathery leaves with what seems a distant horizon. He seems to suggest the gentle movement of the trees in the flow of air and the trembling of their leaves blurring their outlines. It has been argued that in the era of computer-generated images, the work of the imagination is acknowledged once more and that the contribution of the imagination to make scientific images comprehensible, has increased. Bernd Huppauf and Christoph Wulf (2013:16) assert that '[h]ighly technical images correspond to the aesthetic imagination to an extent that no previous science image ever did'. I have endeavoured to make gradually clearer how Boshoff's photographs unobtrusively yet insistently, interrogate the historically shifting horizon of the relationship between aesthetic and scientific imaging by appealing to the 'productive imagination' (Ricoeur 1979) and thus transforming models of perceiving the world.

Acheiropoietoi

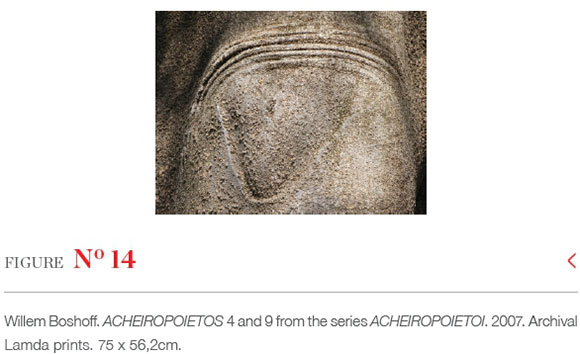

A few of Boshoff's tree photographs have been exhibited as artworks, as in the case of a numbered series of eight photographs of anthropomorphic details of trees titled Acheiropoietoi, which formed part of an exhibition at the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town in 2007, titled ÉPAT (Figures 13 & 14). While taking photographs of trees in the Nirox Sculpture Park in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site near Krugersdorp during a Nirox residency in 2007, Boshoff experienced the endeavour as a meditative encounter. He went closer to trunks and branches in detailed inspections of the fungal infestations at that time, of the elephantine bark of the Celtis Africanus or white stinkwood trees and simultaneously, as behoves the Druid, searched for manifestations of the presence of Dryads or tree nymphs who protect and care for trees, especially in such circumstances. 'The resident nymph of the elm trees and their Ulmaceae family, is Ptelea. She became my primary focus in 2007', he says.11As Boshoff was suffering from lead poisoning at the time, it was with empathy that he examined his diseased "tree-friends". All the photographs taken on these peregrinations were arranged in the order in which they were taken, and labelled Tree Walk in the digital archive. This Tree Walk ultimately sparked the idea of his subsequent famous Druid Walks which could be described as land art performances at any location, during which he still searched for revelations of nymphs or presences or genii loci at selected sites, taking photographs, often joined by a silent crowd of participants.

In the more than 500 close-up photographs taken during the meditative Tree Walk, Boshoff experienced moments of seeing "true images" or vera icons produced naturally by the trees themselves. He experienced that, 'The ancient history of this enigmatic place has somehow forced its way up through the roots of the trees to become visible on the surface of their bark as "body" and "skin"' (Perryer 2007:4). In these close-up photographs, some of which he selected for the exhibition, he framed or cut (true to the etymology of the word 'detail') a part from some trees to make a picture resembling human body parts. However, the title of the exhibited series of photographs, Acheirapoietoi, negates the implicit violence of the photographic act of framing. For Boshoff it seemed that, 'The likenesses conjured up in the trees occur naturally - no trees were harmed in any way. I have used no artificial lighting, no Photoshopping and no cropping or adjustments afterwards' (Perryer 2007:4,5) which make them true Acheiropoietoi ('made without hands'). Acheiropoietoi refers to religious self-made images such as the Sudarium or sweat-cloth of the legendary St Veronica ('true icon') upon which the imprint of the facial features of Christ was made automatically when He wiped his face with the cloth she gave him on his way to Golgotha. It describes the 'untouched figurative elements' in the photographed trees which seems to have been imprinted on the tree by nature itself (Perryer 2007:4). This makes them comparable to the category of objects discussed by Lorraine Daston (1998:232) in 'Nature by design', like cameos (or "figured stones") and fossils 'at one time or another viewed as straddling the boundary between art and nature' and which were believed to be pictures of nature, shaped by nature, during the Early Modern period. For Boshoff, the trees having shed their leaves during winter seemed to be undressed and revealing themselves as human beings, while the marks made by the fungi growing on the infected bark made them seem to be suffering and in pain.

The suffering human figures hiding in the form of trees (Figures 13 & 14) in a wood, remind of a recurring reference in Boshoff's oeuvre to the medieval comparison of the suffering body of Christ (the Word of God) on the Cross, to a tree, and symbolically prefigured by the Tree of knowledge of good and evil. The coloured marks of the infestations on the bark additionally suggest ancient ciphers reminding of Boshoff's characteristic comparison of Book and tree, which to him both reveal and conceal all-encompassing wisdom, which includes knowledge. Thus, nature itself is revealed to be decipherable divine inscription, which could also be 'a strange sacred reality of tree nymphs' (Perryer 2007:6).

Conclusion

During the twentieth century, Duchamp for instance, as suggested above, initiated the project of renewing art's function of once more disseminating knowledge. However, whereas it was believed this was only possible if art were severed from mere mimesis of nature, Boshoff staunchly, but not without a touch of irony and subversion, renews art's conceptual function by returning in these atlas-like images, to the very mimetic medium of photography. Boshoff transcends the aura of automatic graphic inscription and apparent scientific precision of the medium of photography. The title of the series of photographs, Acheiropoietoi, ironically and self-reflectively suggests the 'self-registration' of the 'pencil of nature' (Talbot). Yet, concomitantly the title, in dialogue with the photographs, expands the religious meaning of acheiropoieta to refer to nature as the speaking Word of God. Thus, wonder and joy are combined with scientific meticulousness - as is the case in the photograph in Figure 1, where the sun and blue sky in the depth of the picture reveal the existence of the light of wisdom beyond ordinary vision. The title, Acheiropoietoi, ironically evokes richly interwoven layers of contrasting historical attitudes towards pictures and towards nature. Thus, his multi-layered artistic photographs compensate for the loss of integration among the natural and cultural sciences, and endeavour to make amends for the gap between science and society.

The multi-layered signification of Boshoff's image gallery of botanical photographs aids in diluting the borders between faculties and disciplines, counteracting the modern self-isolation of the Humanities in what Immanuel Kant termed the 'conflict of the faculties' (cited in Borgdorff 2012). This makes evident that imaging is a common problem or field in the entire knowledge system. By eliciting cascades of other images, his tree photographs ignite promises, fears and debates which are central to society's description of itself and of the future of education, knowledge and art.

Notes

1. I want to express my gratitude to Josef van Wyk who expertly advised me on the contents of the archive. See also his joint publication (2017) which contextualises the archive, as well as his Masters' dissertation (2018).

2. The image gallery is partially accessible on the website: http://scholar.ufs.ac.za:8080/xmlui/handle/11660/2565 (accessed on 18 July 2019). The photographs are also available on Boshoff's website: https://www.willemboshoff.com/copy-of-plant-studies. These plant studies are collected under Garden of Words IV under the subheading: Gallery Flora and Fauna. Another subheading reads 'Site Study' and includes photographs of Boshoff's own plant collection at his home in Kensington: https://www.willemboshoff.com/copy-of-garden-of-words-iv-artist-s

3. I want to thank Katja Gentric for bringing to my attention that Boshoff had shunned the figurative image until 2004 when he started to use the camera extensively for the first time, subsequently producing a profusion of photographs. She notes that this new development had seemed incoherent and difficult to reconcile with his previous claims in this regard. I would also like to thank her for her sensitive and careful comments on a previous version of this text. See Gentric (2004; 2013).

4. The contribution of Image Studies, is to not only purposely focus on the political power of what is conveyed by a wider "visual culture", but also to ask fundamental questions about the nature of images (including visible pictures opening up an inner wealth of images and other pictures of what is depicted), and about how images and pictures produce, disseminate and change knowledge in general.

5. This is especially the domain of the Eikones Graduate School at the University of Basel in Switzerland, where the Center for the Theory and History of the Image is an interfaculty and interdisciplinary unit researching images as iconic agents in the whole cultural spectrum.

6. List provided by Josef van Wyk. There is a document in the Willem Boshoff archive listing the names of trees, quotes about trees and words related to trees, under the headings: Some sacred and imaginary trees, Love of trees, Healing and quietude from trees, Conservation/disregard, Oldest trees, Tallest trees, Stoutest trees, Largest trees. The document is called Trees - Leigh Voigt. Willem Boshoff words, and was written in relation to an exhibition at the Everard Read Gallery in Johannesburg, which took place between 29 April 2010 - 23 May 2010.

7. In 2009, for the duration of the Art Basel Exhibition in Switzerland, Willem Boshoff lived like a Druid in a custom-made cubicle replicating his studio at home in South Africa. This media performance was titled Big Druid in His Cubicle. See his proposal for the exhibition in the Archive and listed below

8. The photograph is accessible at: http://scholar.ufs.ac.za:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11660/4415/Celtis_australis.jpg?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

9. Boshoff's idiosyncratic imagery derives from the Bible, as is clear from his Masters' dissertation of 1984. In my interpretation of his work I accept that although he renounces his belief at a later stage in his life, he continues to expand upon, and to re-integrate basic elements of the imaginary world he had forged for himself at the beginning of his career. See forthcoming article by Josef van Wyk on Boshoff's personal symbolism.

10. I thank Katja Gentric for her insights with regard to Boshoff's garden. See also references to Boshoff's garden of the imagination in Josef van Wyk's Masters' thesis (2018:19).

11. Tree nymphs were one of three types of nymphs researched by Boshoff. The others were nymphs of water (the subject of his artwork, 300 Water Nymphs) and nymphs of the city (as in his Druid Walk of 2009, New York. In Memorium).

REFERENCES

Bender, J & Marrinan, M. 2010. The culture of diagram. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Benesch, O. 1943. Leonardo Da Vinci and the beginning of scientific drawing. American Scientist 37f4j:311-328. [ Links ]

Borgdorff, HA. 2012. The conflict of the faculties: perspectives on artistic research and academia. Leiden: University of Leiden Press. [ Links ]

Boehm, G. 1986. Das neue Bild der Natur, Nach dem Ende der Landschaftsmalerei, in Landschaft, edited by M Smuda. Frankfurt aM: Suhrkamp:87-110. [ Links ]

Boehm, G. 2007. Offene Horizonte. Zur Bildgeschichte der Natur. Ein Bildkritischer Versuch, in Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen: die Macht des Zeigens. Berlin: Berlin University Press: 72-93. [ Links ]

Boehm, G, Mersman, B & Spies, C (Hrsg.) 2008. Movens Bild: zwischen Evidentz und Affekt. Paderborn: Fink. [ Links ]

Boehm, G, Egenhofer, S & Spies, C (Hrsg.) 2010. Zeigen: die Rhetorik des Sichtbaren. München: Wilhelm Fink. [ Links ]

Boehm, G, Egenhofer, S & Hinterwaldner, I (Hrsg.). 2012. Was ist ein Bild?: Antworten in Bildern. München: Wilhelm Fink. [ Links ]

Boshoff, W. 2007. Trees undressed. an exercise in acheiropoietics. Willem Boshoff Digital Archive, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Boshoff, W. 2009. Big Druid in his cubicle: Proposal. Willem Boshoff Digital Archive, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Boshoff, WHA. 1984. Die Ontwikkeling en Toepassing van Visuele Letterkundige Verskynsels in die Samestelling van Kunswerke. Beeldhoukuns en Grafiese Kuns. Verhandeling ter vervulling van die vereistes vir die Nasionale Diploma in Tegnologie in die Departement van Beeldende Kuns van die Skool vir Kuns en Ontwerp van die Technikon Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H. 2003. A neglected tradition? Art history as Bildwissenschaft, in The art historian. national traditions and institutional practices, edited by MF Zimmermann. Williamstown, MA: Yale University Press:147-159. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H & Krämer, S. 2013. Culture, technology, cultural techniques - moving beyond text. Theory, Culture & Society 30(6):20-29. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H, Dunkel, V & Schneider, B (eds). 2015. The technical image: a history of styles in scientific imagery. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H. 2010. Theorie des bildakts. Frankfurt aM: Suhrkamp. [ Links ]

Bredekamp, H. 2018. Image acts: a systematic approach to visual agency. Translated by E Clegg. Boston: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Burke, P. 2016. What is the history of knowledge? Malden, MA: Polity. [ Links ]

Busch, W & Schmook, P. 1987a. Kunst: die geschichte ihrer funktionen. Weinheim: Quadriga. [ Links ]

Busch, W & Schmook, P. 1987b. Eine Geschichte der Kunst im Wandel Ihrer Funktionen. Berlin: Quadriga. [ Links ]

Daston, L & Galison, P. 1992. The image of objectivity. Representations 40:81-128. [ Links ]

Daston, L & Galison, P. 2010. Objectivity. New York: Zone Books. [ Links ]

Daston, L. 1998. Nature by design, in Picturing science, producing art, edited by C Jones & P Galison. London: Routledge:232-253. [ Links ]

Daston, L. 2002. Nature paints, in Iconoclash, edited by B Latour & P Weibel. Karlsruhe: ZKM:136-138. [ Links ]

Deleuze, G & Guattari, F. 1988. A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia. Translated by B Massumi. London: Athlone Press. [ Links ]

Derrida, J & Prenowitz, E. 1995. Archive fever: a Freudian impression. Diacritics 25(2):9-63. [ Links ]

Eco, U. 2014. From the tree to the labyrinth. Historical studies on the sign and interpretation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Edie, J (ed). 1964. The primacy of perception. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [ Links ]

Elkins, J. 1995. Art history and images that are not art. The Art Bulletin 77(4):553-571. [ Links ]

Elsaesser, T. 2013. The "return" of 3-D: On some of the logics and genealogies of the image in the twenty-first century. Critical Inquiry 39:217-246. [ Links ]

Ford, LL. 2014. From plant to page: Aesthetics and objectivity in a nineteenth-century book of trees, in Ways of Making and Knowing: The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge, edited by PH Smith, ARW Meyers & HJ Cook. Ann Arbor, MI: Universisty of Michigan Press:221-242. [ Links ]

Foster, H. 2004. An archival impulse. October 110:3-22. [ Links ]

Frank, G & Lange, B. 2010. Einführung in die bildwissenschaft: bilder in der visuellen kultur. Darmstadt: WBG. [ Links ]

Gentric, K. 2004. Gardens of Words, Willem Boshoff remembering not to forget. Paper presented at New Dep(art)ures SAAAH (South African Association of Art Historians) Conference, University of Kwa-Zulu/Natal, Durban. [ Links ]

Gentric, K. 2013. Willem Boshoff, Monographie d'artiste et catalogue. Doctoral thesis in Art History, University of Burgundy, France. Available in the Willem Boshoff Digital Archive, UFS, Bloemfontein. [ Links ]

Gibson, P. & Brits, B (eds). 2018. Covert plants: Vegetable consciousness and agency in an anthropocentric world. New York: Punctum Books. [ Links ]

Hüppauf, B & Weingart, P (eds). 2011. Science images and popular images of the sciences. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Huppauf, B & Wulf, C. 2013. Dynamics and performativity of imagination: the image between the visible and the invisible. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ingold, T. 2000. From trust to domination. An alternative history of human animal-relations, in The perception of the environment. Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill, edited by T Ingold. London: Routledge:71-76. [ Links ]

Ingold, T. 2000. The poetics of tool use. From technology, language and intelligence, to craft, song and the imagination, in The perception of the environment. Essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill, edited by T Ingold. London: Routledge:406-419. [ Links ]

Jones, C. & Galison, P (eds). 1998. Picturing science, producing art. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Latour, B & Weibel, P (eds). 2002. Iconoclash. Karlsruhe: ZKM. [ Links ]

Manghani, S, Piper, A & Simons, J. 2006. Images: A Reader. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Marr, A. 2016. Knowing images. Renaissance Quarterly 69(3):1001-1013. [ Links ]

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1964. Eye and Mind. Translated by Carleton Dallery, in The primacy of perception, edited by J Edie. Evanston: Northwestern University Press:159-190. [ Links ]

Molderlings, H. 1987. Vom Tafelbild zur Objektkunst: Kritik der "reinen Malerei", in Busch & Schmook: 204-232. [ Links ]

Nassar, B. 2018. Metaphoric plants. Goethe's metamorphosis of plants and the metaphors of reason, in Covert plants: Vegetable consciousness and agency in an anthropocentric world, edited by P Gibson & B Brits. New York: Punctum Books:101-122. [ Links ]

Perryer, S (ed). 2007. Willem Boshoff. Épat. Cape Town: Michael Stevenson. [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. 1979. The function of fiction in shaping reality. Man and World 12(2):123-141. [ Links ]

Smelik, A (ed). 2010. The scientific imaginary in visual culture. Goettingen: V&R Unipress. [ Links ]

Smith, PH, Meyers, ARW & Cook, HJ (eds). 2014. Ways of making and knowing: the material culture of empirical knowledge. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Smuda, M (Hrsg.) 1986. Landschaft. Frankfurt aM: Suhrkamp. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, J, De Villiers-Human, S & Van den Berg, D. 2017. Verkennende verbeeldingswêrelde: Die ontsluiting van die Willem Boshoff Argief. LitNet Akademies 74(2):26-64. [ Links ]

Van Wyk, J. 2018. "Tree of knowledge" (1997): Die ontketening van kennissamehange by Willem Boshoff. Masters thesis in the Department of Art History and Image Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. [ Links ]

Winthrop-Young, G. 2013. Cultural techniques: preliminary remarks. Theory, Culture and Society 30(6):3-19. [ Links ]

Zwijnenberg, R. 2010. How to depict life: A short history of the imagination of human interiority, in The Scientific Imaginary in Visual Culture, edited by A Smelik. Goettingen: V&R Unipress:21-38. [ Links ]