Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.34 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a3

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a3

Remembering the Pass - Exploring curatorial reenactment in PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes

Jayne Crawshay-Hall

The Open Window, Centurion, South Africa jayne@openwindow.co.za

ABSTRACT

The exhibition, PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes (2010), curated by Gabi Ngcobo, was site-specific and took place at the former Pass Office in Johannesburg, a space not officially acknowledged as a struggle site. Ngcobo, recognising the potential for using dynamic display formats to mobilise a curatorial concept, brought memory to the fore by installing artworks at the Pass Office as reenactments of evidence. I argue that PASS-AGES invokes traumatic memory through curatorial reenactment, and indicates the potentials for reenactment to explore repressed histories that still hold presence in a contemporary moment. Memory is thus invoked as an additional "text" to mobilise the conceptual framework, akin to how remembrance is often used in the continuous struggle for justice. Employing an autoethnographic methodology, which describes an analytical approach used to critically examine the researcher's own experiences as a means to access greater understanding of cultural experience, I allow the reader to experience the exhibition through my own account. I argue that, as a nomadic curator, Ngcobo was freed from contextual, spatial, or methodological limitations traditionally bound to a colonial logic of curatorial practice. I convey that a nomadic curatorial approach can be adopted to critique traditional or institutional curatorial paradigms. To this end, I argue that Ngcobo was able to engage care in her practice by using reenactment to interrogate memory in a manner that may otherwise have been subdued within an institutional context.

Keywords: Gabi Ngcobo; reenactment; curatorial practice; nomadic curator; PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes, site specific, memory, autoethnography.

Introduction

The exhibition, PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes (2010),1 which was curated by Gabi Ngcobo to coincide with the inaugural launch of the Johannesburg-based curatorial platform, Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR 2010-2014),2 was presented just over fifteen years after the end of South Africa's apartheid regime.3 The exhibition makes direct reference to apartheid's "pass" system in its title and served to interrogate the "ripple effect" incurred as a result of the violations the system imposed.4 Each of the artists included in the exhibition, namely Dineo Seshee Bopape, Ernest Cole (included posthumously), Kemang Wa Lehulere, Zanele Muholi and Mary Sibande, engage with historical narratives as a departure point in their artworks, question issues surrounding identity, and interrogate the role and position of the black body as well as the stigma and withstanding effects that the system of racial classification has had on them (Ngcobo 2010:2). My interest in this article is to convey how PASS-AGES invokes traumatic memory through curatorial reenactment, indicating the potentials this particular curatorial project has to explore repressed histories that still hold presence in the contemporary moment.5 Ngcobo's PASS-AGES, I indicate, became a 'vehicle of trauma' (Felman 1997: 743).6 I argue that Ngcobo uses space and the arrangement and installation of artworks to mobilise a conceptual framework that invokes memory as an additional "text". Through this, Ngcobo foregrounds how memory work, and the remembrance of traumatic events can be used in the continuous endeavour to achieve justice for violations against human rights (Bonder 2009:63).7 I contend that through presenting the exhibition as a reenactment, Ngcobo elicits care in her activist curatorial practice by inviting the viewer to reflect critically on traumas related to the pass system, and thereby invoke empathy and understanding in this context.

Mediating the exhibition, PASS-AGES

PASS-AGES was site-specific, installed in the basement section at the site of the former Pass Office in Johannesburg;8 a building that had not been acknowledged as an official "struggle site".9 According to James Balloi ([sa]), the Pass Office was the 'head office' for the Johannesburg Non-European Affairs Department (JNEAD) and could be described as the 'nerve centre' of apartheid. After 1986, when the pass system was abolished, the Pass Office was shut down, and as investigated in PASS-AGES, it is believed that the records were burned or otherwise destroyed (Ngcobo 2010:2).10 This routine practice of destroying records by the apartheid government, or what Verne Harris (1999:1) refers to as 'state-imposed amnesia', was a significant method in which the National Party (NP) attempted to maintain power and control. Ngcobo used the space in PASS-AGES to "weave" these narratives into the curatorial text, so that space became an important tool in establishing the conceptual underpinning of the exhibition.

The space is described by Khwezi Gule (2015:92) as exuding oppression. I argue that Ngcobo's assumption of a nomadic curatorial position allowed her to be selective with space and be able to use and respond to site-specific contexts in order to critically question, and in some cases, dismantle, the mechanisms of exclusion inherent in institutional spaces. The nomadic curator is thus able to accelerate the critical quality of curatorial practice in a way that may have been minimised by a curator working in an institutional space. I define the nomadic curator as an independent curator who has become resourceful in gaining access to space, but who does not work in a manner that is restricted by policies or expectations imposed on permanent museum/gallery employees or independent curators working in traditional art spaces. By working in a nomadic capacity, curators are able to respond to the former, as well as the limiting parameters of the institutional/white cube spaces that are available. Ngcobo did not aesthetically "neutralise" the space for the sake of displaying the artworks,12 but rather worked with the space to bring about affective meaning, inserting the works into the space as she found it so that the viewer may imagine that this was exactly how the space was left the moment the Pass Office was vacated. The nomadic approach thus invites the curator to use space to enhance the conceptual framework of the show, and stimulates a dynamic curatorial response in developing new creative solutions that work within these spaces. I argue that, owing to Ngcobo's nomadic approach, she was able to make use of adaptive curatorial models and transform PASS-AGES into a discursive site that deconstructed characteristic curatorial approaches.

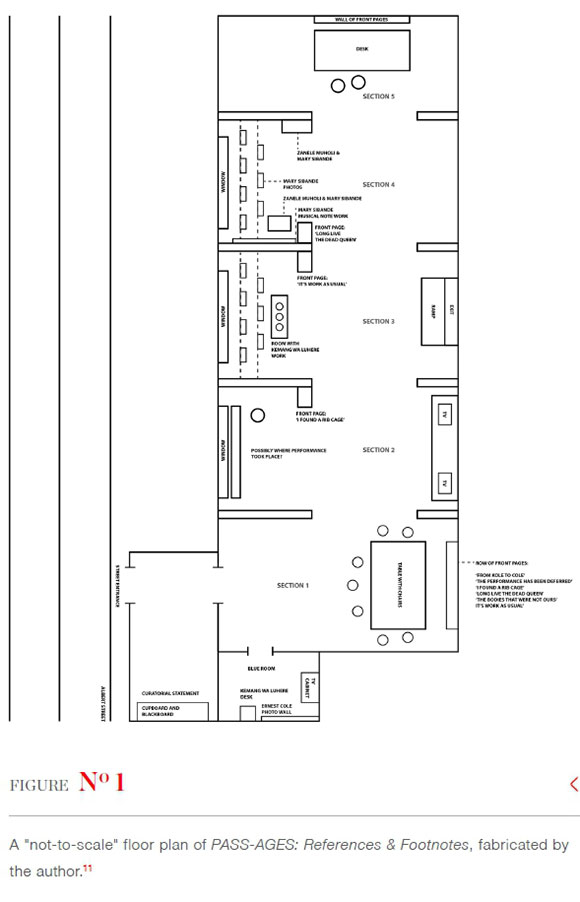

Below I outline my own experience of encountering PASS-AGES and the 'consciousness-raising appeal' it brought to bear for me (Margulies 2003a:15). It is important to note that my experience of the exhibition is a mediated one that took place through the "leftovers" of the project, and is thus not an immediate response. These remains exist through the space and the layout, the building, the exhibition notes, the curatorial statement, the photographs, and the remaining artworks and objects that I have encountered in differing contexts, newspaper articles, the published catalogue, and published reviews and commentaries available. In mediating PASS-AGES, I employ an auto-ethnographic methodology, which describes an analytical approach used to critically examine the researcher's own experiences of the process, result and understanding. According to Carolyn Ellis, Tony Adams, and Arthur Bochner (2011), autoethnography is a method employed that allows the researcher to simultaneously describe and analyse personal experience as a means to understand cultural experience. Furthermore, autoethnographic researchers produce research that is grounded in personal experience, and which can be used to 'sensitize readers to issues of identity politics, to experiences shrouded in silence, and to forms of representation that deepen our capacity to empathize with people who are different from us' (Ellis & Bochner 2000 in Ellis, Adams & Bochner 2011). As such, I do not assume that my research is independent from my experience, but rather acknowledge that my experience is valuable to my research (Méndez 2013). I adopted this approach as an attempt to negotiate the tendency to discuss the remains of an exhibition out of context of the experience and effects of the project, which are often far more elusive. My description, which is to be read in conjunction with Figure 1,13 enables the reader to "re-enact" the manner in which one may have navigated and been affected by PASS-AGES:

Upon entering the old government-style building on Albert Street in Marshalltown, Johannesburg city, a space that is currently being utilised as a women's shelter, one first encounters a curatorial statement, hand-written in white chalk onto a painted blackboard, framed by a blue chalk-drawn border positioned above a dilapidated white wooden cabinet built onto the wall. The paint on the wall is peeling off.

The curatorial statement comprises a number of questions, such as: 'What is the relationship between art and history?' and 'How can art contextualise history and how can it effect how we receive or understand history?'. To the right of the blackboard, in two neatly drawn squares, acknowledgements to the supporters of the exhibition14 and artist and research contributors are listed.15 Neatly piled on top of the cabinet lies a stack of curatorial programmes which take the form of a self-published newspaper. They include a curatorial outline, biographies, written contributions, references to artworks and past historical events, as well as a record of events that may be cited as having an impact on the contemporary artists' works on display.

After reading the curatorial statement, one encounters the main exhibition area: a large basement that is divided into five sections due to the architectural layout and the addition of prefab walling installed on the street-side of the building. The atmosphere is reminiscent of an old, neglected, administrative department, and the space appears deteriorated from time. Fluorescent lights and exposed bulbs, their lampshades missing, provide the lighting to the exhibition. Poor natural light seeps in through the street-facing windows and the darkly painted burglar bars draw attention to the fact that the windows are street level. The exposed concrete floors, which are cracking in areas and dirty from years of foot-traffic, storage and use, add to the atmosphere of neglect.

In the first section of the exhibition, a large wooden table surrounded by white plastic garden chairs is placed on one side of the room. More curatorial programmes are piled on this table. The walls have an off-white shade (presumably from years of needing to be re-painted) except for the primary shade of blue peeping through the doorway of the small adjoining room to the right. Upon entering this confined space, one is faced with a backdrop of Ernest Cole's now iconic image, titled Young Boy is Stopped for his Pass as White Plainclothesman Looks On (1967), printed jumbo size and repeated as a wallpaper, floor to ceiling, across the breadth of the entire back wall.

Against this backdrop, Kemang Wa Lehulere's sculptural piece is installed in the corner in front of the doorway, for which no title is provided. The sculptures are made from repurposed and reassembled old-style school desks typical of South African schools. They are rendered defected and dysfunctional without a surface and with a chair set so close to the desk that it is impossible to sit on. On the adjacent wall, a box-set television, positioned in an old cabinet, plays Wa Lehulere's video piece titled Pencil Test (c 2010) on loop. In it, Wa Lehulere reenacts the notorious pencil test used for apartheid classification,16 rendering it absurd through multiple insertions of pencils into his own hair (Bethlehem 2010). One is invited to sit on the two retro wooden armchairs with green velvet cushions, placed in front of the cabinet, and watch the video piece.

Exiting this room, and walking towards the next section, one encounters two more box-set televisions placed on top of an old wooden counter - the kind that resembles 1950s-style office furniture. One television set plays another of Wa Lehulere's performances, titled uGuqul'ibhatyi (2008) on loop.17 In this piece, Wa Lehulere digs a hole using an afro-comb in a back-yard of a house in the township of Gugulethu,18 Western Cape, only to discover the skeleton of a cow.

Moving to the third section, introduced by way of a fabricated front-page newspaper street-pole advertisement containing the text 'I found a ribcage' the viewer is faced with a cubicle dedicated to displaying objects and photographs related to Wa Lehulere's video performance pieces. On the floor, placed dramatically in the centre of the room, is a wooden display box containing a selection of three popular "types" of Afro-combs. Each "type" is contextualised through the inclusion of two examples, grouped through their display as specimens framed by sheets of glass. The objects are amplified by the backdrop to this representative display, as still images from the performance hang clipped onto wires draped across the breadth of the room, as if part of a process of gathering evidence, or hung out to dry in a darkroom. The exhibition is presented as an act of gathering data and presenting the narratives of those affected by the pass system.

Again, as a way of introducing Zanele Muholi's work installed in the fourth section of the basement area, a fabricated version of the front-page of a newspaper advertisement containing the text 'Its work as usual [sic]' hangs at the archway. Muholi's photographic series titled, Work as Usual (c2010) is a direct reference to a newspaper article, 'Work as Usual for Bester', published in The Sun newspaper (3 December 2002) which acknowledged Bester Muholi, Muholi's late mother, for her 41 years of dedicated work for one family at the time of her retirement from employment as a domestic worker.19 In the black and white photographs, Muholi investigates the problematic relationship of the South African (white) "madam" and (black) "maid". The unframed photographs are haphazardly pinned, like cheap, non-precious pamphlets or handouts, to two old wooden notice boards. One board leans against the wall to the left, and the other, a "sandwich style" board, is placed on the right side of the room. Inserted amongst these are photographs from Mary Sibande's series, Long Live the Dead Queen (2010), exhibited in the same space due to Sibande's similar inquiry into the role of the "maid" and its perseverance in post-apartheid and democratic South Africa. On the wall to the right, a large, blue fabric installation of musical notes hangs at eye-level adjacent to a front-page newspaper poster with the text, 'Long live the dead queen' on it. Towards the back of the room, Sibande's sculptural piece, a life-size figure dressed in a transformed maid's uniform that recalls Victorian-style dress, is installed; the blue fabric is overflowing on the floor in front of photographs of the installation.

Finally, one faces a wallpaper installation of fabricated front-page newspaper posters, repeated to take up the entire wall's space. The posters include texts that refer to each artist's works included in the show, as a reminder of how art can affect how history might be understood: 'From Kole to Cole'; 'The performance has been deferred'; 'I found a rib cage'; 'Long live the dead queen'; 'The bodies that were not ours' and 'Its work as usual [sic]'. This installation forms the backdrop to a reception counter, with two stools that sit precariously in front of it - perhaps a visual reminder of the bureaucratic system of apartheid.

Curatorial reenactment

Historical reenactments, according to Jonathan Lamb (2009:1), serve to reproduce and reframe history in the present. Vanessa Agnew (2009:297) concurs, stating that reenactment offers an opportunity to bring the past closer to the present. Both Lamb (2009) and Agnew (2009), however, speak of reenactment in the manner that calls to mind a group of people, dressed in costumes, reenacting battles in a celebratory way. Reenactment, as adopted by Ngcobo, is used rather critically and with a certain degree of irony. Ngcobo's use of reenactment serves to provide palpable physical context to a history that the NP attempted to erase. Recognising the potential for the exhibition as a medium to mobilise this concept, Ngcobo experiments with curatorial composition by inverting the "traditional" hanging style one may expect from conventional exhibition displays, and rather "sets a stage" using the artworks as prompts to reenact the effects of the pass system and pose questions about how this history has impacted the present.

Muholi's series, Work as Usual (c2010), investigates the continuation of the informal domestic work sector in post-apartheid South Africa. Muholi visually depicts hierarchy in her work by framing the high heels of a white employer against the view of a domestic worker washing the floor on her knees (in this case, a self-portrait). Considering how the series was installed, as unframed photographs, tacked to a notice board, the works can be read as an annotation to the continuing complexities of the domestic worker/employer relationship (Bethlehem 2010).20 Sibande's Long Live the Dead Queen (2010), installed in the same room, uses a similarly informal display style, with works hung on clips, or tacked to the board in between Muholi's series. According to Bronner (2016:ii), the figure of the "maid", used by both Muholi and Sibande, can be considered a vehicle to evoke memory and emotion related to South African historical traumas. The curatorial composition alludes to Ngcobo's supposed intention that these photographic artworks should be read as testimonials evidencing the continued effects of apartheid and the trauma of surviving the pass system. The works, installed as reenactments, elicit acknowledgement of the past, allowing the exhibition to play a role in prompting reconciliation and redress.

The display of the Afro-comb "tools" used to excavate the soil in Wa Lehulere's performance, uGuqul'ibhatyi (2008), is particularly important, as the comb makes reference to Afro-hair, which apartheid officials assessed to racially classify citizens.21 By making this reference using an Afro-comb, often used to tease out hair into an Afro-style, Wa Lehulere is perhaps subverting the perception of Afro-hair being used for oppression, and rather positing Afro-hair alongside discourses of black empowerment through hair styling (Afro-hair was used as a signifier of Black Power in the 1960s and 1970s). By installing this work in relation to Cole's repeated image, Ngcobo presents a 'dense nexus' of the 'lived archive' of South African racial production (Bethlehem 2010).

The exhibition also serves as a vehicle for further reenactment, conjuring up the effect of the trauma of the past as a vehicle for post-trauma or postmemory for some viewers.22 This can be considered in terms of Derridean thought, specifically considering the notion of trace, wherein the sign, for Jacques Derrida (1997 [1967]:xvii), is always already inhabited by that which is forever absent. Derrida (1997 [1967]),23 discussing deconstruction, uses the term 'sous rature' (French for "under erasure"), and printed both the word and the deletion to show that signs are always inhabited by other signs, which implies a move away from binary constructions (Spivak 1974:ixi). For Derrida (1997 [1967]), the sign should always be studied as "under erasure", always already inhabited by the trace of another sign, both simultaneously present (the reenactment as the sign) and absent (the post-traumatic experience/memory as the trace). The notion of trace can also be used to access Griselda Pollock's (2009:40) understanding that trauma is 'not in the past, since it knows no release from its perpetual present because it is not yet known: was never known, hence never forgotten, and thus not yet remembered'. The inclusion of Dineo Bopape's live performance piece, titled The Performance Has Been Deferred (2008, 2010), further highlights the tensions between acknowledgement and denial, which are embodied in the Pass Office space. Raél Jero Salley (2013:358), who details the events of this performance piece,24 describes how Bopape (or an actor) would exit from the gathered crowd waiting in anticipation for the performance to begin, and announce into a microphone under the spotlight, that the performance has been deferred before returning into the crowd. Salley (2013:355) contextualises the term 'defer' as implying that which is not yet fully present.

This experience relates to the lingering effects the pass system may have had on the people never fully acknowledged as present or entitled citizens in their own land, and whose standing as South African was essentially deferred (Salley 2013:357-8). As with Derrida's (1997 [1967]:xvii) conception of trace, black South Africans were citizens both present and absent, denied a place in society, whilst simultaneously subjected to surveillance in the pass system, their standing in society sinisterly documented. Furthermore, the performance can also be considered a metaphor for the unacknowledged struggle site of the Pass Office, and how this deferral of remembrance can be considered a trauma itself.

Ngcobo's curatorial reenactment could be argued to embody the 'aesthetics of remembrance' (Hirsch 2008:104), linking reenactment as an aesthetic approach to account for a collection of knowledge and/or memory absent from the historical archive (Diane Taylor in Hirsch 2008:105). PASS-AGES should therefore be considered a "reinscription" of memory into the site where the traumas are connected. By drawing attention to the lack of acknowledgment and the need to actively confront the issues required to achieve redress, PASS-AGES also presents a "challenge" towards the ideologies of reconciliation, unity, and transformation in post-apartheid South Africa (Roux 2017:100). Ngcobo's PASS-AGES is thus a call for accountability, using (ironical) "reenactment" as a means of unearthing testimonies and gathering "evidence" of the traumas and post-traumas of apartheid's crimes against humanity.

Care as curatorial methodology

Magdalena Jadwiga Härtelova (2016:5) argues that care should be considered a methodology in curating, and motivates the curator to entice the viewer to think critically about matters, even if they extend beyond the 'life experiences' of the viewer. Care in curating is also a way of encouraging the viewer to be an active participant, whereby the curator consistently prompts the viewer to consider ways to 'think through' the exhibition 'even when our bodies, our identities, are implicated and being changed' (Härtelova 2016:23). Ngcobo intended to use the exhibition as a vehicle to impact various groups, and not only those directly affected by being subject to the pass laws. This is important, as Dominick LaCapra (1999:697) indicates that post-apartheid South Africa is presented with the problem of 'working through historical losses in ways that affect different groups differently'. By drawing on frameworks of critical reenactment, Ngcobo does not "work through" the loss for us, but invites the audience to experience the reenactment and acknowledge the impact within the space that embodies the trauma. In this sense, Ngcobo's practice to reenact traumatic memory can be considered an attempt to draw out repressed memory and to actively engage with the trauma of the pass system. Ngcobo's exhibition serves as a means to provide evidence to trauma, and thus humanise those previously relegated to marginalised positions both by the pass system, and thereafter by the denial of the evidence's roles as witness to these traumas. By reenacting the evidence of the Pass Office, Ngcobo asks of the viewers to reconsider their own subjectivities and consider differing narratives from differing historical accounts.

For those who had to endure the pass system, and for the generations that followed, I speculate that the physical space of the Pass Office would work to summon traumatic memories and postmemories of the primary objectives of the apartheid state. For those that occupied a position of privilege during apartheid, the space may serve as a reminder to how white privilege was attained through black oppression, and elicit feelings of shame. Whilst outlining my experience of PASS-AGES, I became acutely aware of my own position as a white, middle class, South African woman, born in the latter half of the 1980s and thus never having fully lived the experience of apartheid myself. Encountering a reenactment of traumatic memory, of which my race and self is implicated - or as Samantha Vice (2010:323) argues, is 'thoroughly saturated by histories of oppression' - brought to bear an acute sense of shame and guilt, which manifested into a deeper empathy and awareness of the continued impact South African apartheid history presently has. This lasting impact, bolstered through sifting through the remains of the exhibition and experiencing the documents as evidence, testimony and memory of past and current oppression, I believe, had a greater impact on me than learning about the logistics of the pass system through secondary sources has ever had. The reenactment provided me with a momentary glimpse into the lives of the disempowered, and the continuing impact this trauma evokes.

The aim of the exhibition was to encourage a reinterpretation of the past (Ngcobo 2010:2). This position is reiterated in the curatorial statement framing the exhibition, which was presented in the accompanying "newspaper". The framing of the curatorial programme in newspaper-like compositions contributes to the impact of reenactment, not only by explaining the curatorial concept and providing anecdotes to the works on exhibition, but also by allowing the presentation to visually and conceptually provoke further frameworks through which the exhibition may be read. This is further exemplified in the use of the accompanying headline additions to each artist's work. According to Ngcobo (2010:2), the curatorial programme, presented as a newspaper, was 'compiled to suggest the various ways of sifting through the rubble of history'.

Despite the apartheid government's stringent attempts at censorship,25 newspapers served a seminal role in the resistance struggle against apartheid and the efforts to highlight awareness of the racial injustice that was occurring against black people in South Africa. The image, taken by Sam Nzima, of Hector Pieterson's 26 lifeless body being carried down the street during the 1976 Soweto Uprising,27 published widely in newspapers, is an example of how newspapers helped to emphasise, and possibly even revive, resistance action in society. Importantly, this reference to histories of resistance by the youth is also called to the fore in PASS-AGES through the use of the curatorial statement as hand-written on a black board. The blackboard formulation may also have been used to "reenact", or call to the fore, past resistance to the unequal education at white and black schools. Thus, the composition of the curatorial framework as both newspaper- and blackboard-style format, responds to themes of resistance. The exhibition statement, which is still widely available, offers longevity to framing the curatorial concept for the exhibition, and in a similar way, to how space can be used as a tool to enhance the curatorial concept of the exhibition; so too can the installation/ presentation of the curatorial statement.

Conclusion

Terry Smith (2012a:21) discusses the notion of 'activist curating', as often enacted beyond the venues of the art world, where the exhibition is presented as an argument and conceptual framework to spark response, highlight issues that need further engagement, and bring about political and social change. Ngcobo's intention was to convey how contemporary artists' practices are significantly shaped by the construction of historical legacies (Ngcobo 2017; Ngcobo 2010:2). The use of space and curatorial composition in PASS-AGES imbues the exhibition with meaning, galvanising the exhibition's potential of uncovering testimonies, and thus contributing to probing the manner in which society responds to these denied narratives (Ngcobo 2010:2). Using reenactment to interrogate memory in her curatorial practice, Ngcobo was able to highlight repressed histories in a manner that may otherwise have been subdued within an institutional context. By evoking care in her activist curatorial practice, Ngcobo invited the viewer to reflect critically on repressed violations in an attempt to contribute to the endeavour to achieve justice for violations against human rights. Ngcobo's use of reenactment allowed her to invoke memory in a way that provided further critical comment on socio-cultural and political issues regarding histories, the erasure of histories, and the need to engage, address and contextualise these histories and traumatic memories for the remediable future. As Ngcobo uses care as a methodology in her curatorial reenactment, so I employ reenactment as a strategy in this article, wherein I invite the reader to reflect critically on PASS-AGES, which has the potential to continue to develop empathy and understanding through the longevity of the reenacted exhibition statement still widely available.

Acknowledgements

Much of the research in this article is extracted from research conducted as part of my PhD study, titled 'Reconceptualising curatorial strategies and roles: Autonomous curating in Johannesburg between 2007 and 2016' (2019). The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards my PhD research in 2016 is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

Notes

1. Hereafter referred to as PASS-AGES.

2. The CHR was co-founded by Ngcobo and artist Kemang Wa Lehulere in July 2010. The CHR intended to explore ways in which artistic production could frame particular readings of history, and furthermore, how history informs artistic production (Gabi Ngcobo/Radio Papesse 2010). Their intention was to reveal how histories are universal, can be repeated, and are often preserved (Smith 2012a:156-157), which they explored through exhibitions, publications, screenings, discussions, performances, workshops and seminars.

3. Institutionalised racial segregation (apartheid) was made law in South Africa by the National Party (NP) from 1948 until 1994.

4. The pass system, under apartheid, was implemented as a way of controlling the movement of black citizens in South Africa. According to Khwezi Gule (2015:92), the pass (also nicknamed ipasi or dompas) was an internal passport that black citizens over the age of sixteen years were required to carry by law. The pass served to racially identify black citizens and contributed to regulating the movements of black citizens in urban centres. This system was instrumental in implementing racial segregation laws, such as the Population Registration Act or the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act. During apartheid, if a black citizen was caught without his/her pass, he/she could be arrested, fined, or deported to rural "homelands". In the context of this article, I use the term "black" inclusively to represent all those who were not classified as "white" under the apartheid racial classification system, similarly to how Steve Biko regarded "black" as an inclusive term in the context of the Black Consciousness movement (Hadfield 2017).

5. Ngcobo set a precedent of using reenactment in curatorial practice as a form of critical enquiry and affective engagement with the past in South Africa, both in this exhibition, and in her collaborative establishment of The Center for Historical Reenactments. In South Africa, although many site-specific monuments have been established, the use of "reenactment" as a critical tool to mobilise (traumatic) memory as an additional text within these sites is uncommon, and the potentials of curatorial reenactment remain under-explored. It should be acknowledged, however, that visitors to sites such as Constitution Hill and Robben Island may (momentarily) engage elements of reenactment as part of experiencing the historical conditions of the site. Thus, despite the exhibition being ten years old in 2020, it serves as a noteworthy example of how reenactment can be used as a curatorial technique.

6. Shoshana Felman (1997) discusses the trial of OJ Simpson as a 'vehicle of trauma', arguing that it 'aggravated' the trauma by means of highlighting the consequences of the event. In a similar way, Ngcobo's PASS-AGES also interrogates the lasting effects that the pass system has had.

7. Trauma is a reenactment of violence and a reliving of the event. Bonder (2009:63) references apartheid as an example of a traumatic event. Trauma, however, is not only experienced as a result of major events, but also as day-to-day lived experiences of these manifestations of trauma, such as the continued impact that oppression has on everyday South African life following the abolition of the pass system.

8. The former Pass Office is situated at the corner of Albert and Polly Street in Johannesburg, South Africa. During apartheid, the Pass Office was the Johannesburg administrative office responsible for issuing pass documents and tracking the movements of black South Africans.

9. By acknowledging spaces as "struggle sites", the current African National Congress (ANC) government provides opportunities for the active remembrance of the struggle for freedom in South African history. This preservation of historical/heritage sites (particularly "struggle sites") is acknowledged for important resistance events having taken place there during apartheid.

10. Balloi ([sa]) comments that despite the building having significance in apartheid history, the building's history and the events that occurred at the site remain proportionately unknown.

11. The floor plan was fabricated from the close readings of numberous photographic records of the installation. The plan indicates the placement of the works in relation to the space and its remaining features, such as furniture left behind, and should be read in conjunction with the written walkabout as described below.

12. I use "neutralise" in this sentence to indicate the common aesthetic process of readying a space for the display of art by preparing surfaces using neutral tones (white, grey, beige). I use scare-quotes to indicate that I am aware that white spaces are not neutral spaces, and thus I am not using the term "neutralise" reductively.

13. Figure 1 indicates a "not-to-scale" floorplan that outlines where I surmised each of the elements were placed in the space, and can be referred to as visual support for the written "walkabout". As I had not attended the exhibition myself, and was unable to access the site where the exhibition was held in 2010 due to the building being unofficially classified as illegally occupied at the time of writing, I base my description of the exhibition on close readings of photographic records of the installation. I also consider quotes by authors who describe their own accounts of the exhibition, namely Louise Bethlehem (2010) and Khwezi Gule (2015), which I have used to assess my readings of the photographic records in the installation. The images, which are copyright to The Center for Historical Reenactments, are available on its website: http://historicalreenactments.org/Passages.html

14. The supporters are listed as the Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism (JWTC) and The Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR), Goethe Institut and Usindiso Ministries.

15. The contributors to the programme are Coco Fusco, Sean Jacobs, Desiree Lewis, Hlonipha Mokoena and Zamani Xola.

16. During apartheid, officials would assess "Afro-hair" to racially classify citizens. The objective was to test with how much ease the pencil moved through the hair, and depending on the result, the subject would be classified within a racial group (Gule 2015:92-93).

17. According to Gule (2015:92) the performance is titled after the isiXhosa term for a "turncoat". This is a reference to the nickname used to refer to black citizens who altered their racial identity so that they could be classified "coloured" (the apartheid-era name for people of mixed race) as coloured people held more privileges during apartheid than black people. The work was originally performed as part of the exhibition entitled Scratching the Surface Vol. 1 curated by Ngcobo and Mwenya Kabwe at the AVA Gallery in Cape Town, 4-22 August 2008.

18. Gugulethu is a township in Cape Town, South Africa, where Wa Lehulere grew up (Gule 2015:92).

19. This newspaper article was included in the curatorial programme for the exhibition, PASS-AGES.

20. As Irene Bronner (2016) has indicated in her analysis of Muholi's Massa and Mina(h) series, which the series included in PASS-AGES was later referred to, the work also has underlying homoeroticism. Bronner (2016:186) argues that Muholi fictionalises a pseudo-sexual relationship between Mina the "maid" and her "madam"; it is 'a story line that encourages the viewer to self-consciously evaluate how narratives from various origins may be imposed upon both "maid" and "madam"'.

21. As previously mentioned, this process was referred to as the "pencil test".

22. Marianne Hirsch (2008:104) discusses postmemory as a framework to consider the transfer of trauma and memory from one generation to another. Postmemory, for Hirsch (2008:104), is inherited trauma, often passed to the second generation. For some, despite the event occurring before their birth, the inherited trauma can be so deep that is gets passed on to the next generation, and manifests as memory (Hirsch 2008:104). Considering that PASS-AGES was installed in 2010, 16 years after the end of apartheid, and 24 years after the abolishing of the pass system, it can be argued that the reenactment may have provoked the experiences of trauma both through post-trauma and postmemory.

23. Derrida wrote De la grammatologie in 1967, which was first translated to English by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in 1974.

24. It should be noted that Salley's (2013) discussion of Bopape's The Performance Has Been Deferred (2008) is made in context to its presentation at the exhibition Black Womanhood: Images, Icons and Ideologies of the African Body curated by Barbara Thompson (The Hood Museum of Art, New Hampshire, 2008). However, as the title of the performed work is maintained from the original 2008 performance, my assumption is that the intention and happenings of the performance remain similar to those that took place in PASS-AGES.

25. Newspapers during the apartheid years were often white owned, white controlled, and published in support of the NP's political regime - or if not, they were often shut down or censored. There were a few white-owned newspaper platforms that presented criticism of the government, notably the Rand Daily Mail and later, the Weekly Mail (Touwen 2011). After the Rand Daily Mail closed in 1985, a few journalists went on to form the Weekly Mail, which later became the Mail & Guardian.

26. According to the website on Gauteng Tourist Attractions (1999-2018) that refers to the Hector Pieterson Memorial Site, the spelling of Pieterson has been written as "Peterson" and "Pietersen" by the press, but the family has confirmed that the correct spelling is 'Pieterson'. The Pieterson family's surname was originally "Pitso", but the family opted to adapt their surname in an attempt to pass as "coloured" during apartheid. Thus, for the sake of this study, I have opted to use the spelling indicated as correct by Pieterson's family.

27. The 1976 Soweto Uprising was a series of demonstrations led by black school children in South Africa, protesting the NP's decision to make Afrikaans, alongside English, a compulsory medium of instruction in schools (announced in 1974). It should be noted that the Bantu Education Act of 1953 had already implemented an inferior education system for black children. The protest action began on the morning of 16 June 1976, where between 3000 and 10 000 students joined the march. Policeman met on route opened Are, using tear gas and live ammunition, which resulted in widespread revolt against the government and a country-wide uprising (South African History Online 2019).

References

Agnew, V. 2009. Epilogue: Genealogies of space in colonial and postcolonial reenactment, in Settler and creole reenactment, edited by V Agnew and J Lamb. London: Palgrave Macmillan:294-318. [ Links ]

Agnew, V & Lamb, J (eds). 2009. Settler and creole reenactment. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Arriola, M. 2009/2010. Towards a ghostly agency: A few speculations on collaborative and collective curating. Manifesta Journal: Journal of Contemporary Curatorship 8:21-31. [ Links ]

Balloi, J. [sa]. Albert Street Pass Office. [O]. Available: http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article-categories/albert-street-pass-office Accessed 3 January 2018. [ Links ]

Bethlehem, L. 2010. By/way of Passage. [O]. Available: http://jhbwtc.blogspot.co.za/2010/07/byway-of-passage.html Accessed 21 February 2018. [ Links ]

Bonder, J. 2009. On memory, trauma, public space, monuments, and memorials. Places 21(1):62-69. [ Links ]

Bronner, IE. 2016. Representations of domestic workers in post-apartheid South African art practice. Doctor of Literature and Philosophy thesis, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Derrida, J. 1997 [1967]. Of grammatology. Translated by GC Spivak. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Ellis, C, Adams, CT & Bochner, AP. 2011. Autoethnography: An overview. FQS Forum: Qualitative Social Research 12(1). [O]. Available: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1589/3095 Accessed 4 March 2019. [ Links ]

Felman, S. 1997. Forms of judicial blindness, or the evidence of what cannot be seen: Traumatic narratives and legal repetitions in the O. J. Simpson case and in Tolstoy's "The Kreutzer Sonata". Critical Inquiry 23(4):738-788. [ Links ]

Gabi Ngcobo/Radio Papesse. 2010. Gabi Ngcobo - The incubator for a Pan-African roaming Biennial: Manifesta 8. [Podcast]. Available: http://www.radiopapesse.org/en/archive/interviews/gabi-ngcobo-the-incubator-for-a-pan-african-roaming-biennial Accessed 22 October 2017. [ Links ]

Gauteng Tourist Attractions. 1999-2018. Hector Pieterson Memorial Site. [O]. Available: https://www.sa-venues.com/attractionsga/hector-pieterson-memorial-site.htm Accessed 30 March. [ Links ]

Gule, K. 2010. Contending Legacies: South African modern and contemporary art collections, in 100 years of collecting: The Johannesburg Art Gallery, edited by J Carman. Pretoria: Design>Magazine:119-126. [ Links ]

Gule, K. 2015. Center for historical reenactments: Is the tale chasing its own tail? Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 39:90-99. [ Links ]

Hadfield, LA. 2017. Steve Biko and the black consciousness movement. [O]. Available: http://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-83 Accessed 11 February 2019. [ Links ]

Harris, V. 1999. "They should have destroyed more": The destruction of public records by the South African state in the final years of apartheid, 1990-1994. [O]. Available: http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10539/7871/HWS-166.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed 7 June 2019. [ Links ]

Härtelova, MJ. 2016. Curating ~ Care: Curating and the methodology of intersectional care. Master's thesis in Curatorial Practice, California College of the Arts, California, United States. [ Links ]

Hassan, S. 2008. Introduction, for the twenty-first century and the mega-shows: A curator's roundtable. Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 22/23:152-188. [ Links ]

Hendeles, Y. 2011. THE WEDDING (The Walker Evans Polaroid Project): A curatorial composition by Ydessa Hendeles (New York: Andrea Rosen Gallery 2011). [O]. Available: https://artmap.com/andrearosen/exhibition/the-wedding-2011 Accessed 9 June 2019. [ Links ]

Hirsch, M. 2008. The generation of postmemory. Poetics Today 29(1):103-128. [ Links ]

Jonas-Mpofu, T. 2018. Introduction, in A person my colour: Love, adoption and parenting while white, edited by Martina Dahlmanns. Cape Town: Modjadji Books. [ Links ]

LaCapra, D. 1999. Trauma, absence, loss. Critical Inquiry 25(4):696-727. [ Links ]

Lamb, J. 2009. Introduction to settlers, creoles and historical reenactment, in Settler and creole reenactment, edited by V Agnew and J Lamb. London: Palgrave Macmillan:1-19. [ Links ]

Lowenthal, D. 2015. The past is a foreign country - revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Margulies, I. 2003a. Bodies too much, in Rites of realism: Essays on corporeal cinema, edited by I Margulies. Durham & London: Duke University Press:1-15. [ Links ]

Margulies, I. 2003b. Exemplary bodies: Reenactment in love in the city, sons, and close up, in Rites of realism: Essays on corporeal cinema, edited by I Margulies. Durham & London: Duke University Press:217-244. [ Links ]

Margulies, I (ed). 2003. Rites of realism: Essays on corporeal cinema. Durham & London: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Méndez, M. 2013. Autoethnography as a research method: Advantages, limitations and criticisms. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal 15(2). [O]. Available: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0123-46412013000200010 Accessed 4 March 2019. [ Links ]

Miller, K & Schmahmann, B (eds). 2017. Public art in South Africa: Bronze warriors and plastic presidents. Indiana: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Ngobo, G. 2017. SABC News: Gabi Ngcobo on her appointment as curator of the 10th Berlin Biennal. [O]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WhzUc6P6iW8 Accessed 23 October 2017. [ Links ]

Ngcobo, G. 2010. PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes. A curatorial project by the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR) in collaboration with the Johannesburg Workshop for Theory and Criticism (JWTC). [Catalogue]. [O]. Available: http://historicalreenactments.org/images/projects/Passages/15-1.pdf Accessed 7 July 2016. [ Links ]

Okeke-Agula, C. 2008. The twenty-first century and the mega-shows: A curator's roundtable (Gilane Tawadros, Elizabeth Harney, Ery Camara, Laurie Ann Farrell, Colin Richards). Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 22/23:152-188. [ Links ]

O'Neill, P. 2007. The curatorial turn: From practice to discourse, in Issues in curating contemporary art and performance, edited by J Rugg and M Sedgwick. Bristol: Intellect:13-28. [ Links ]

PASS-AGES References and Footnotes. 2013. [O]. Available: http://historicalreenactments.org/Passages.html Accessed 2 November 2017. [ Links ]

PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes (self-published newspaper). 2010. Johannesburg: Center for Historical Reenactments and Johannesburg Workshop in Theory and Criticism. [ Links ]

Pollock, G. 2009. Art/Trauma/Representation. Parallax 15(1):40-54. [ Links ]

Roux, N. 2017. Mandela's walk and Biko's ghosts: Public art and the politics of memory in Port Elizabeth's city center, in Public art in South Africa: Bronze warriors and plastic presidents, edited by K Miller and B Schmahmann. Indiana: Indiana University Press:95-117. [ Links ]

Salley, RJ. 2013. The changing now of things. Third Text 27(3):355-366. [ Links ]

Smith, T. 2010. The state of art history: Contemporary art. The Art Bulletin 92(4):366-383. [ Links ]

Smith, T. 2012a. Thinking contemporary curating. New York: Independent Curators International. [ Links ]

Smith, T. 2012b. Contemporary art: world currents in transition beyond globalization, in The global contemporary: The rise of new art worlds after 1989, edited by H Belting, A Buddensieg and P Weibel. Cambridge, Massachusets: MIT Press:[sp]. [ Links ]

Smith, T. 2015. Talking contemporary curating. New York: Independent Curators International. [ Links ]

South African History Online. 2019. [O]. Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/history-apartheid-south-africa Accessed 7 June 2019. [ Links ]

Spivak, GC. 1974. Translator's preface, in Of grammatology by Jacques Derrida. Maryland: John Hopkins University Press:xxvi-cxii. [ Links ]

The Center for Historical Reenactments. 2013. [O]. Available: http://historicalreenactments.org/index3.html Accessed 22 October 2017. [ Links ]

Touwen, CJ. 2011. Resistance Press in South Africa: The legacy of the alternative press in South Africa's media landscape. [O]. Available: https://carienjtouwen.wordpress.com/essays/resistance-press-in-south-africa/ Accessed 30 October 2017. [ Links ]