Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.34 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a2

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a2

Embedded participation in the architectural curriculum towards engendering urban citizenship in graduates

Carin CombrinckI; Rienie VenterII

IUniversity of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, Carin.Combrinck@up.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0003-0501)

IIUniversity of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, Ventema@unisa.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6441-565X)

ABSTRACT

Instilling ethical development and a regard for the production of urban space through vertical and horizontal curriculum participation may equip architectural graduates with the capacity to engage with the complexity and temporal fluidity of urban citizenship. Creative outputs of four academic year groups in an Architecture department who engaged with a particular township community in South Africa were considered in terms of Perry's Scheme of Intellectual and Ethical Development and how this relates to Lefebvre's notion of lived space. The students' levels of engagement and recognition of the complexity of social structures were reflected in the levels of ethical development presented in the models used. In this paper we argue that it is necessary to distribute curricular participation vertically throughout the curriculum to ensure that students are able to transcend from one level to the following in order to resolve the complexities they are confronted with in the spatial and ontological challenges inscribed within urban citizenship.

Keywords: Urban citizenship; curricular engagement; ethical development in education; Thirdspace.

Introduction

The urbanism of the Global South is one of emergence and contested spatial legacies, a multi-dimensional palimpsest of social, political and economic agencies calling for radical consideration of the skills required to navigate this complex environment. These skills include the development of ethical moral values that support the graduate professional in transcending a position of authority-in-knowledge to one of citizen collaborator.

In the face of homelessness, violent service delivery protests and opportunistic crime, institutional and market-driven development has resulted in schizophrenic spatial conditions of self-incarceration and collective paranoia. In this scenario, the greatest loss is that of urban citizenship, or meaningful and authentic participation in the urban realm. According to Henry Lefebvre's (1991) proposed understanding of urban space, this lack of engagement undermines a fundamental aspect of human activity, in which a collective contribution to the oeuvre of the city is required. This cannot, therefore, be separated from the more technical skills required of spatial professionals. In Edward Soja's (1996) re-presentation of Lefebvre's constructs, he suggests that architecture is normally concerned with the material realities of fixed and imagined spaces (First and Second Space), but rarely with the complexities of Thirdspace, where the dimensions of time, sociality and change are ever present. The potential for the architectural profession to actively contribute to this fluid and contested space is therefore drawn into question unless there can be a concerted effort to reconsider the social dimensions of the discipline.

Through community engagement strategies that have evolved at universities since the 1990s, it has been argued that students can become socially aware of urban circumstances beyond their own frame of reference (Oldfield 2008). These strategies of engagement, however, can only contribute to the type of meaningful citizen engagement inferred through a reading of Lefebvre (1991) and Soja (1996), if the potential for this evolution within students could be activated and developed. William Perry's (1970) Scheme of Intellectual and Ethical Development describes such an evolution from a simplistic and binary view, to one in which greater complexity and openness can be observed.

Globally, literature on the scholarship of engagement considers the many ways in which participation is included into curricula and takes cognisance of Ernest Boyer's (1996:19-20) vision connecting the wealth of academic resources to the most pressing social, civic and ethical problems (Bringle & Hatcher 2009). However, the institutionalisation of participation in the form of service learning is often seen to be superficial, temporal, lacking in commitment and impact, and in many cases, more damaging than beneficial to the partnering communities (Gray in Costandius & Botes 2018; Winkler 2013). The enrichment of curriculum content, development of professional attitudes, and definitions of citizenship are similarly lacking even though service learning appears to promise such consequences (Perold-Bull in Costandius & Botes 2018). There is therefore a need to propose participation strategies that serve to support the development of an ethos towards urban citizenship, in which the complex understanding of spatial production can be embedded.

The aim of this paper is to illustrate the potential shifts in moral ethical development in architecture students through focused participation with a specific social network in a marginalised urban community. The argument forwarded is that embedded participation across the architectural curriculum can contribute towards the development of greater complexity in thinking, thereby assisting students to evolve from a position of authority-in-knowledge towards one of moral commitment to an integrated and complex reality. Such an approach is required for the architectural profession to contribute meaningfully to the current urban conditions of emergence and contested legacy that are particularly relevant to the South African context. By establishing participation as an embedded component of the curriculum, architectural graduates may be equipped to navigate complex socio-spatial landscapes, thereby acquiring the tacit skills required for urban citizenship.

A reading of urban citizenship through the lens of Lefebvre (1991) and Soja (1996) establishes the theoretical framework of the paper, from where it is argued that Perry's (1970) scheme of students' intellectual and ethical development can be seen as a necessary pathway to equip architectural graduates with the capacity to engage with the complexity and temporal fluidity of urban citizenship. An overview of the scholarship of engagement situates the paper in current discourse, from where selected creative outputs of curriculum-based engagement modules across four academic year groups at a South African university's Department of Architecture are considered. A thematic analysis of the work serves to identify positions of ethical development as described in Perry's (1970) theory and how this relates to a reading of urban citizenship. Findings from this exploration point to the importance of coherence in the scholarship of engagement, where long-term commitment is required to simultaneously navigate the differences in students' development phases, as well as establishing an authentic dialogue with the participating community groups.

Literature Review

Urban Citizenship

There is agreement among scholars of urbanism that the Global South is experiencing an unprecedented migration to urban centres, resulting in volatile contestations for opportunity, access and power. Postcolonial legacies of spatial segregation are being challenged through informal occupation on the one hand, and market-driven development on the other. Within these spaces of heightened tension, there is an evolving conceptualisation of what it means to contest the right to the city (Huchzermeyer 2011). According to Soja's (1996) interpretation, such contestation plays out in his conceptualisation of the Thirdspace, a theoretical construct in which the fluidity, temporality and complexity of spatiality occurs. This is differentiated from First space, that can be equated with the documentation of found conditions, such as Geography, and Second space, that refers to the constructed imaginaries often associated with planning and architecture. A further reading of rights-based literature, however, points to urban citizenship as the creation of re-shaped identities through participation, therefore an insistence on the value and importance of engaging in the Thirdspace.

Talja Blokland, Christine Hentschel, Andrej Holm, Henrik Lebuhn and Talia Margalit (2015:656-657) describe urban citizenship as 'continuously in the making', a multi-layered strategy of local socio-political movements engaged in debates on rights to, in, and through the city. Recognised by a tireless process based on reciprocity, negotiation and adjustment (Grazioli 2017), urban citizenship is seen as a contextualised, community-oriented and bottom-up framework (Blokland et al. 2015). J Mauricio Domingues (2017) regards this type of citizenship as a form of mediation between modern individuals, where identity is shaped through solidarity and active public participation. The possibility of cosmopolitan transformation at a national scale is considered by Rainer Baubock (2003) to be a possible result emanating from this understanding of urban citizenship.

Grass roots civic movements originating in the urban peripheries of the Global South have been credited with these new conceptualisations of governance, citizenship, and social rights (Cunningham 2011; Domingues 2017; Holston 2008). Rights-based literature celebrating the achievements of these activist movements mostly focuses on the strength of their self-determination in offering an alternative to entrenched power relations (Lopez de Souza 2010). In line with this, Diana Mitlin (2013) pertinently discards any value that can be brought to these community-oriented structures by urban design professionals owning to their implication in the formal systems themselves.

Amira Osman (in Costandius & Botes 2018:71), however, contends that an educational attitude that denies the contribution that can be engendered through developing a capacity for participation effectively withholds vital professional services from the communities that most need them.

Although social change is driven largely by social imagination and collective creativity, Domingues (2017) points to the fact that while this may lead to new types of demo-cratisation and urbanisation, it may also lead to new kinds of violence, injustice, fear and residential fortification. It could therefore be argued, in the light of establishing a virtuous urban citizenship (Cunningham 2011), that co-production of such a new identity could in fact benefit from spatial agency (Awan, Schneider & Till 2011), where urban professionals could 'intervene in complexes of interacting processes where they find themselves in already formed cultural conditions' (Cunningham 2011:39). Therefore, in conceptualising an urban citizenship that is complex, heterogenous, context-specific, and aimed at remaking society, greater value may be attached to the contribution of various role-players to the urban experience (Baubock 2003; Blokland et al. 2015; Domingues 2017; Grazioli 2017).

Building on James Holston (2008:9), the potential for urban professionals to contribute to the formation of such a new identity would rely on achieving solidarity or shared citizenship values based on transformed relations and rooted within the urban environment. Seeing the right to the city thus enfolded in an understanding of urban citizenship suggests a concern with the decisions that produce urban space (Purcell 2009). According to Holston (2008:9), this then implies a role for professionals that is 'specific to place, particularity of interest ... hence requiring a skill set of participation'.

Community participation in tertiary education

Preparing graduates in the spatial disciplines to engage with these complex decision-making processes related to the production of urban space involves a deeper reading of curricular participation in higher education. From Boyer's (1996) vision of connecting the resources of higher education to the social and civic needs of society, curricular participation has become significant in most institutions of higher education. A framework for critical citizenship education has been proposed by Laura Johnson and Paul Morris (2010), in which knowledge, skills, values and disposition have been considered in terms of political, social, subjective and practical engagement aspects. Their concern highlights the importance of seeing the challenge in holistic pedagogical terms. Robert Bringle and Julie Hatcher (2009) suggest that the value of engagement ought to be considered in terms of the breadth and depth of curricular offering, institutional philosophy, and involvement by the participating communities. The authors consider the ideal situation to be one in which engagement modules are evenly distributed across academic units (horizontal distribution) and across various levels of the curriculum (vertical distribution), in particular so that longitudinal evaluation of student development can be assessed, along with long term impacts on participating community structures.

The dilemma of meaningful engagement

In the South African higher education context, participation in the form of community engagement, service learning, and community development has evolved since the 1990s with institutional support from government and service partners (Mouton & Wildschut 2005). Impact studies on students, staff and participating communities have contributed to a deepening of the scholarship of engagement and have provided the basis for comprehensive policies outlining strategic and operational plans for the implementation of curricular engagement (De la Rey, Kilfoil & van Niekerk 2017; University of Pretoria 2012). As part of these outcomes, such policies are designed to ensure that students receive one module per degree course in which a community engagement experience is required, while at the same time ensuring that there should not be so many engagement components that the workload becomes too onerous (University of Pretoria 2012).

Within such a narrow ambit of the actual implementation of curricular engagement, however, there is no opportunity for the vertical and horizontal distribution suggested by Bringle and Hatcher (2009). This may be seen as contributing to some of the critical reflection offered by Tanja Winkler (2013), in which expectations by community members and students alike could not be met through the engagement processes. Work undertaken by Planning students in the context of marginalised urban communities failed to deliver on the hope created by their involvement, and relationships with community members became strained. As Winkler (2013:224) states, 'It was unrealistic to expect implementable interventions based on a semester-long project with introductory students'. Sophie Oldfield (2008) and Costandius and Botes (2018) similarly report on the limitations derived from the short span of time allocated to an architectural engagement studio in South Africa, and suggest that the deliverables of such engagements need to be clearly defined at the outset so as to avoid unrealistic expectations and disappointment.

The prevalent theme of curricular participation is the need for reciprocal learning, impact and knowledge development. Whereas the original intention may have been weighted in favour of philanthropy, experience points to the need for engagement strategies to grapple with the dissonance between entrenched (western and north-Atlantic) knowledge systems, and those that have been marginalised, thereby addressing the 'violent denial of the racially colonized's humanity and history and a systematic devaluation of cultural uniqueness' (Fanon in Rabaka 2009:194).

Authority in Knowledge

Through the legitimation of reason and rational thinking, one mode of thinking is promoted and usually enforced. According to Newtonian thinking, it is believed that an objective reality exists and can be discovered through reason (Meyer, Moore & Viljoen 1997). We contend that it is not such knowledge itself that poses a problem, but the authority that is attached to knowledge systems and which legitimises it as the only way to approach a problem. When knowledge is declared "true" by means of scientific reasoning and experimentation, it is usually considered as authoritative because it is based on "reason". According to Enlightenment thinking, reason is considered the only avenue towards reliable knowledge, to discover universal truths, and the key to making the world a more progressive, safe, and humane place (Farganis 1996:11). Based on the authority that was gained through science and rational thinking, reason is considered an indisputable way to interpret humanity and to address problems in scientific disciplines.

When it is believed that reason is the only way to approach problems, it follows that those who take exception to this view may be considered "non-reasoned". In the rational community, the imperative of what should be spoken is reason. The speaker is inessential, as long as what is said is in accordance with the prevailing narrative. Zygmunt Bauman (1995:203) argues that western and north-Atlantic paradigms for thinking rest on a 'cognitive and moral map' of the world. A further consequence of the rational community is that those who do not fit into this way of thinking may be assimilated by making them the same as all the others, or rejected as strangers, as the other or as culturally disadvantaged (Bauman 1995:202). Either way, the stranger is seen as a problem, someone whose mode of being needs to be either corrected or resisted, someone whose reality can be accessed, described and interpreted.

Pierre Bourdieu (1977) is of the opinion that individuals' right to participate in public decision-making may be benefited by them having certain credentials. If one is familiar with the dominant culture, able to understand and use so-called "educated" language, possess the attitudes and values held by the dominant class, have the propensity to affirm and conserve the dominant culture, and practice customs that the dominant culture considers valuable, it may lead to more societal benefit (Sullivan 2002).

While growing up in Kenya, NgügT wa Thiong'o (1992:16-17) experienced a deliberate undervaluing of his people's culture and history, as well as the repressing of their language: the colonial child was made to see the world and where he stands in it as seen and defined by, or reflected in, the culture of the language of imposition. A lack of such cultural credentials that Bourdieu (1977) refers to therefore not only results in no voice, but helps to reproduce and legitimate social inequalities, as well as enable the subject-object dichotomy where one person has the right to define the reality of the other.

Herein lies the potential value of participation strategies; in the ability to undermine the inherent and assumed authority in knowledge towards a deeply responsive transformation of the fundamental project of knowledge development itself. For such a project to have meaning and impact on an emergent society, however, it is important to view it as legitimate in itself, not to limit it to a single module in a curriculum or to confuse it with substitute service-related products. Rather, we argue that participation ought to be embedded within the curriculum to ensure the development of complexity in the graduate. We suggest that the curriculum should be open to the realities and differing ontologies presented not only by the marginalised communities that constitute the "other", but increasingly and necessarily responsive to those students who have grown up in such "othered" contexts and who struggle to synthesise these contested ontologies (Davids 2019).

Phases of student development

While keeping valuable models in our disciplines, we need to detect the authority in knowledge systems such as absolutes and binaries. This implies that people cannot be removed from the contexts that shape them, the processes of which they are a part, and the relationships and connections that structure their being-in-the-world. To move towards social justice in the built environment planning disciplines, we need a new commitment to ethical research. To establish an ethics of being as a legitimate alternative to an ethics of absolutes, we may draw on Perry's (1970) Scheme of Intellectual and Ethical Development.

The development towards complexity in Perry's scheme describes an evolution from a simplistic, categorical and binary view of the world, to a realisation of the contingent nature of knowledge and the relativity of values. It successfully transcends the deadlock of relativity in morality in its last phase. For the purposes of this article, Perry's nine statuses are clustered into four general positions. In each position, elements of Thirdspace are integrated to broaden the dimension of ethical possibilities.

Position 1: Having a perception of the world in absolutist terms

During this stage, individuals defend and follow concrete and absolute categories deriving from their discipline by using closed logic. As a representative of the "rational community", they assume the moral high ground of objectivity and neutrality. Based on the viewpoint that absolute truth exists, they believe that the knowledge base from which they work exists absolutely. They feel comfortable in this framework of absolutes, because it is supported by science, where everything is measurable and explainable. From this position they are able to consider the physicality of space (First space) and may experiment with the planning and conception of changed physical space according to their known value or knowledge system (Second space).

The position they occupy is one of authority, as a subject who may study and describe the reality of the "other" as object scientifically and make interpretations accordingly. Should this reality differ from the absolute rules in the discipline, the studied reality may be considered as deviating from the set norm. At this level, any diversity of opinion or social commentary is regarded as unwarranted confusion. Disruption, diversity and uncertainty are seen as temporary and puzzling, and the individual may get confused and even defensive in the light of options or multiple points of views. If the individual cannot transcend this stage, remaining at this level of understanding the world may limit the successful consideration of moral options in their full complexity and extent (Clarkeburn, Downie, Gray & Matthew 2003:444).

Position 2: Making room for diversity and recognition of the multi-faceted aspects and problematic nature of life

This stage of development allows individuals to acknowledge that there may be more positions than simply the absolutes of the values and approaches in their discipline. They no longer consider opinions that differ from theirs as deviating. However, they will remain in a position where they will either not be able to evaluate the different points of view, or they will refrain from attempting to understand them by saying, I don't have all the answers.

Position 3: Recognising that knowledge and values are relative

During this stage, individuals recognise that knowledge is contextual and relative. Where previously different points of view were simply recognised, individuals now see all perspectives as pieces that fit together into a larger whole, namely the context of the various points of view. Individuals now have the capacity for detachment; they seek "the big picture". They question all absolute values and they release the position of authority which was assigned to them in their discipline. While now questioning all values, including their own, an interesting problem is created. Which route should be followed, since everybody's beliefs have merit? Because it is now impossible to choose, they can take neither role nor responsibility. Henriikka Clarkeburn et al. (2003:446) refer to this as 'distress in relativism'. In this respect, Lefebvre (in Soja 1996:61) suggests that disruptions building cumulatively on one another produce 'a certain practical continuity of knowledge production that is an antidote to the hyperrelativism and anything goes' philosophy often associated with such radical epistemological openness. Therefore, if the deadlock that relativism holds is not solved, professionals in a discipline will work without direction. In this position, discussions about ethics may serve only to increase confusion and the use of non-constructive escape mechanisms in the face of intolerable indecision rather than to support ethical development (Clarkeburn et al. 2003:444). For the built environment planning disciplines to be able to move to an ethics of being as a legitimate alternative to an ethics of absolutes, transcending this position of abstractness and immateriality is necessary.

Position 4: Experiencing the necessity of orienting oneself through personal commitment

The individual resolves the threat of identity loss and disorientation, which may have been created by temporarily struggling with the implications of relativity in the previous phase, by making a moral commitment (Clarkeburn et al. 2003:447). By drawing on Lefebvre's Thirdspace, this moral commitment is a strategic position against an ethics of absolutes and in favour of an ethics of being. There is no fixed absolute value or answer and only diverse, even opposing, values. This position creates a possibility for the 'thirding-as-othering', a critical step in transforming the closed logic of 'either/ or' to the dialectically open logic of 'both or also' (Soja 1996:60). 'Thirding-as-othering' does not just constitute a position in-between opposites, or a superficial consensus, but it becomes a position with combinatorial potential which 'transforms the categorical to the dialectically open logic of "both" and "also"' (Soja 1996:60). It not only brings together competing values; it brings together what is available.

In this regard, Perry's concept of constructed knowledge is relevant to dialogue where multiple views exist (Finster 1991:754). It opens the possibility of integrating procedural knowledge gained from the group, with personal, "inner", "prior", subjective, or intuitive knowledge based on personal experience, as well as avoiding that compartmentalisation which Perry considers a shortcoming of objective knowledge. It is not any more a focus on the differences between constructs, but on the dialectical relationship between them (Soja 1996:61). It is a radical openness to additional otherness, an openness to a continuing expansion of spatial knowledge where any new creative direction does not constitute a new absolute. Lefebvre (in Soja 1996:61) therefore contends that there are no permanent constructions of reality, only continuous disruption and interruption of values to remain receptive for different perspectives.

Methodology and data collection

The philosophical approach of this study is the phenomenological interpretivist paradigm. This research approach suggests that one's reality is socially constructed (Mertens 2005) and described not by objective observation, but by 'identifying the essence of human experiences about a phenomenon as described by participants in a study' (Creswell 2009:231). The research method used is the qualitative research approach.

The study considers work undertaken in an urban township in South Africa and is representative of four academic year groups in the Architecture department of the local university. Participation with the community was arranged by way of a network of Early Childhood Development centres (ECDs) situated within a 5km radius of the satellite campus, which is situated in the township approximately 25km from the main campus. The principals of the ECDs were identified through their involvement with the Service Learning Entrepreneurship Unit of the Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences.

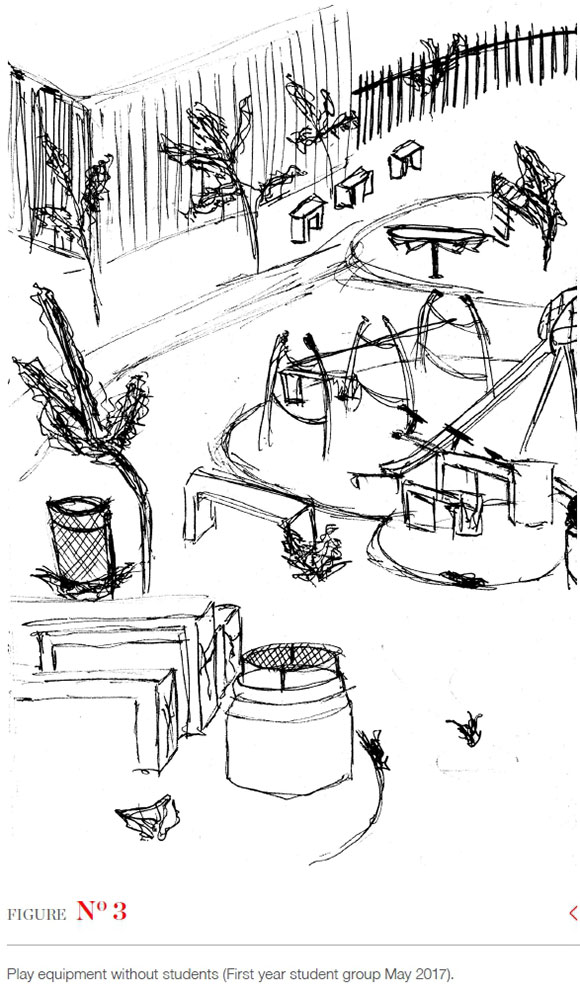

As the study was aimed at investigating embedded participation within existing modules, the sequence of activities was determined by schedules that predetermined when and how often students could be in the field (Osman in Costandius & Botes 2018:76). Table 1 lists the student groups that were involved, along with the duration of their engagement.

Analysis of all the data was guided by the data analysis process as proposed by Martin Terre Blanche, Kevin Durrheim and Desmond Painter (2006:322); the assignments and activities during the visits are described together with the findings and discussion.

Step1: Familiarisation and immersion

The researcher reads through the data and reflects on the meanings thereof to deepen the researcher's understanding of the interpretation likely to occur. Ideas and identification of possible patterns may be shaped as the researcher becomes familiar with all aspects of her/his data. Emerging impressions of what the data mean and how elements in the data relate to each other may emerge.

Step 2: Inducing themes

While reading and reflecting, themes that emerge are identified. A theme captures something important about the data in relation to the research question and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set. A new theme or sub-theme may be identified as the data are being analysed.

Step 3: Coding

Pieces of qualitative data are broken up to still retain their context and meaning, and are coded into the identified themes.

Step 4: Elaboration

When bringing coded data together, meaning is created that describes the theme. Sections of text that appear to belong together are compared to elaborate on existing themes.

Step 5: Interpretation and checking

The gathered information is reviewed into appropriate interpretations for each year group.

In addition, field notes, memos and reflections by the researcher are also documented during data collection and are used to enrich the data, as well as to clarify information.

Findings and discussion

First year day trip to the township

As part of the first year in Architecture, students are required to maintain a visual journal in which they document spaces, objects and experiences. For their trip to the township, they were tasked to capture their impressions of the place in the same way, without any prompting or stimulus. Once they were in the area, they undertook a walking tour with opportunities for sketching. No direct participation with community partners was arranged for this trip, as it was intended to gauge the students' representation of the context. For the majority of the 81 students, this represented their first opportunity to experience a part of the city considered to be foreign and inaccessible.

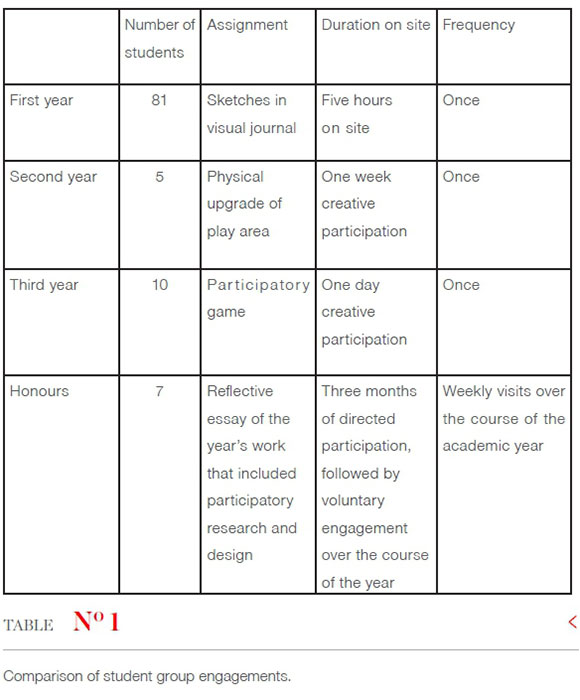

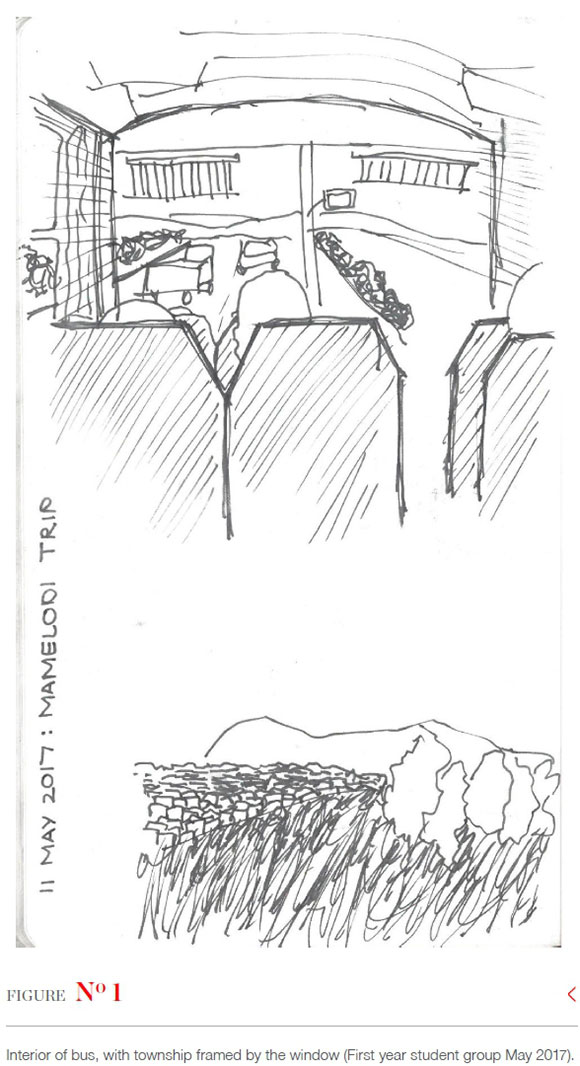

Themes identified in the journal sketches ranged from specific contexts, such as the interior of the bus, to that of distant observer once they entered the township. Certain landmarks, such as electrical pylons, made significant impressions, and architectural qualities were noted to greater or lesser degrees of detail. The presence and absence of people in the spaces became a significant theme in the sketches.

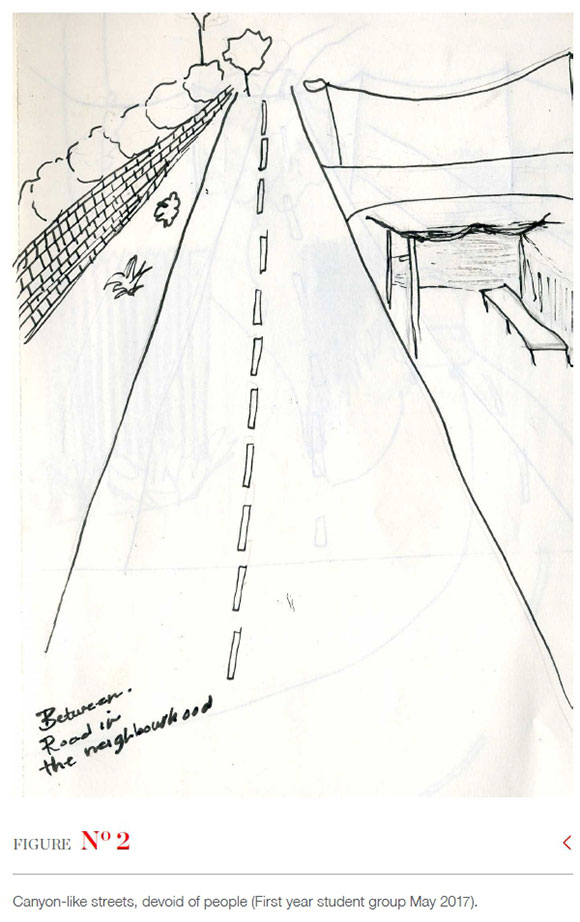

The trip into the township is seen in a great number of drawings, where the bus interior is populated by heads peeking over the back of seats, followed by images of the township seen in the distance, framed by the bus window (Figure 1). For the greatest part, sketches indicated an unoccupied urban environment, where empty streets framed by canyon-like walls and razor wire hide the houses (Figure 2). The first point of entry into the area was a park with play equipment, where all the students commenced to draw in their journals. Despite this high level of activity, more than half of the sketches of this play park are devoid of people, and present desolate landscapes of walls and play equipment (Figure 3). Sketches of street vendor stalls are similarly shown as being empty even though these structures are hubs of informal trade (Figure 4). Where people are shown, it is usually the back of a colleague walking ahead, distinguishable by the details on the backpacks.

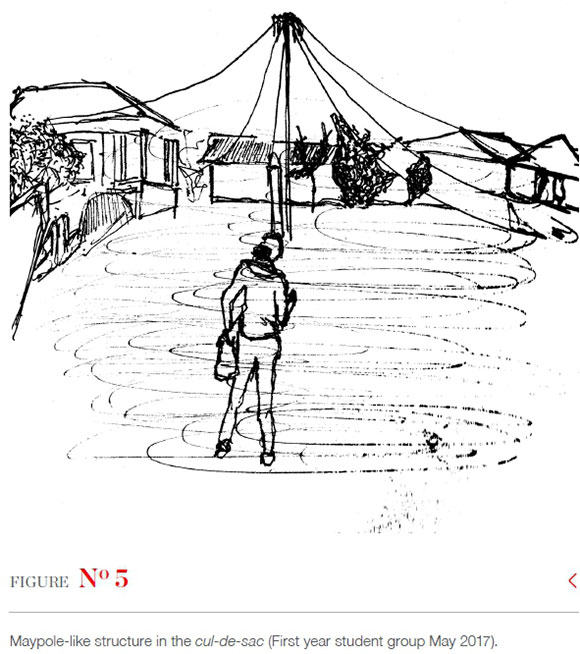

Architectural details on buildings, fences and signage were captured in many instances, with many of the students focusing on negative aspects such as broken trees, litter and prison-like fences. Most significantly, more than two thirds of the students produced sketches in which an electrical pole in the middle of a cul-de-sac is indicated as being extremely prominent, with electrical cables connected to the surrounding houses in a maypole-like fashion (Figure 5). This vertical element is often drawn in dark lines, situated in the middle of the page. Large electrical pylons were also documented, but did not feature as regularly as the maypole-like structure.

The salient positions that are derived from this analysis can be related to the first level of development as outlined by Perry (1970), in which these students are able to document physical and objective space (First space), devoid of people. By focusing on the found conditions of the site, such as litter, fences and broken trees, they display the ability to study and describe the reality of the "other", rather than being immersed in the space. Where immersion is evident, such as drawing the inside of the bus or a friend's backpack walking ahead of them, this appears to confirm their self-awareness and defensiveness in the strange and foreign context. The remarkable emphasis placed on the square and maypole-like structure in front of one of the ECDs is reminiscent of Kevin Lynch's (1960) description of nodes and landmarks, where it is argued that people tend to require a mental map of the urban environment to counter the fear of disorientation. By documenting such a prominent landmark, emotional security and conceptual organisation can be created. It would appear from this investigation, therefore, that the first-year students maintained their distance and scientific objectivity during this field trip, which according to Clarkeburn et al. (2003), could limit their capacity for complex integration if they were to be rooted in this position of moral development.

Second year upgrade of play space

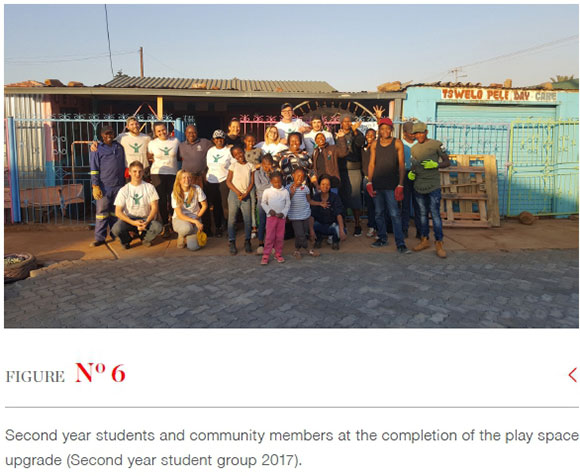

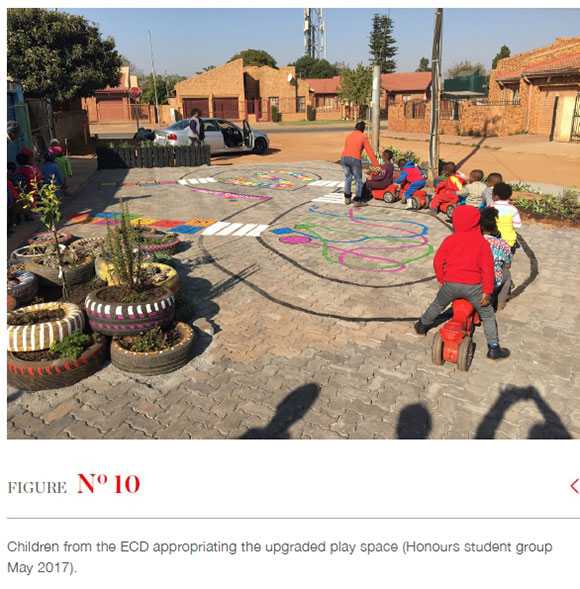

The mandatory credit-bearing module representing the single official opportunity within the curriculum for a community engagement experience is the Joint Community Project module (JCP), situated in the second year of study (University of Pretoria 2012). Every student enrolled in the Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology Faculty is required to render 40 hours of community service within a self-selected project. One group of five students chose to undertake the upgrade of one of the partnering ECD's play spaces, which is documented in a video as part of the expected outcomes. Levels of engagement, task orientation and an attitude towards aid and dependency could be thematically derived from the video documentation.

Engagement with the community did not occur immediately with this group, as they initially focused more on the task at hand, rather than engendering relationships, although this softened over the course of the week with community members becoming more involved as the project progressed. From their approach to the project, it is clear that the second year group did not consult the community on the merits of their proposal and followed a very confident task-oriented attitude to achieving a completed product (Figure 6). Their consideration of impact or potential for change is viewed as one of aid or philanthropy, where they equate their achievement with the gratitude of the beneficiaries.

It is not entirely clear whether one can claim a direct association between this work to Perry's (1970) second position of development, as the work is not necessarily indicative of students acknowledging positions beyond the absolute. Rather, one could argue that there is more evidence to suggest a certain amount of rootedness in the first level, in which a position of authority is retained. By engaging in the planning and conception of a changed physical space (the upgrade of the play area), it could be argued that students were able to experiment with Second space. Despite the contribution of community members to the project towards the end, such contribution was viewed as subject to the task at hand, rather than being viewed as transformative in any way beyond the physical. This resonates with concerns raised by Costandius and Botes (2018), Oldfield (2008) and Winkler (2013), in which engagement projects may even be negative because of a lack of due consideration for impact on the community. This can then be argued back to Perry's (1970) identification of a level of moral development (in this case, not fully at level two yet) that cannot yet grasp the complexity of such consequence.

Third year game assignment

During their third year, Architecture students are introduced to development practice theory as a conceptual framing for architectural intervention, with a strong emphasis on community empowerment. As part of their outcomes, students are required to design a participatory game, of which the enactment in its intended context must be documented on video. Two of the groups chose to implement this assignment at the ECDs, with one game of road safety instruction and one focused on the awareness of personal space. A few themes could be identified from these videos, such as the students' attitudes to the staff and children in the ECDs, their interest in documenting the surrounding context, and the level at which they positioned the outcomes of their games.

Owning to the nature of the assignment, both videos indicate the playful way in which students engaged with children and staff of the ECDs. An eagerness to engage with the children is clear, with a general sense of co-operation in the students as well as the participants (Figure 7). A certain amount of contextual information is offered in the road safety game, in which the problem being addressed through the game is highlighted. In the personal safety game, little attention is given to the surrounding context - rather, the focus is on the game being played by the children, along with the students engaging with them. In both instances, the choice of game and its presentation is based on the possibility of effecting change in the behaviour of the children to empower them in their context. Despite the clear indication that the context presents certain challenges, emphasis is placed on the vibrancy and positive potential of the township.

According to Perry's (1970) scheme, one could expect students in their third year of study to have progressed towards the second and third positions of intellectual and moral development, so that one could observe a possible shift from absolute objectivity towards acknowledging positions different from their own, possibly questioning known values. The confusion that is opened in the second position may lead to a state of detachment in the third position, where authority is released. In the instance of the game where students are urging the children to say no to infringement on their personal space, it could be argued that students are reflecting their own situation by emphasising the right to say no to authority. One may contend that this demonstrates a desire for cumulative disruption as suggested by Lefebvre (in Soja 1996:61), rather than complacence in terms of social constructs.

In the road safety game, students display the capacity to see 'the big picture' as described by Perry (1970) by identifying the relation between unsafe conditions observed in the context and the need to instill road safety habits in children through the game. The perspective of the children becomes the focus in both games, thereby supporting Perry's observation that students at this stage of development have the ability to accommodate values or points of view other than their own. The indecision about the relativity of values that may be present at this stage could not be discerned from these assignments (Clarkeburn et al. 2003).

Honours critical reflection essays

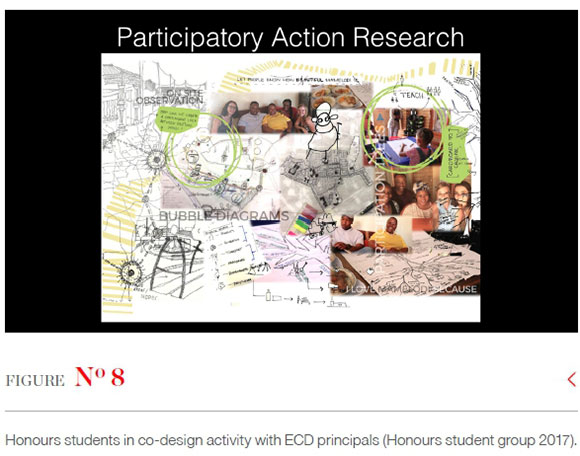

The most comprehensive participation occurred within the Honours course, where students were introduced to the ECD principals at the beginning of the year and were encouraged to build relationships of trust over the course of the year, with co-design as expected outcomes (Figure 8). Theory lectures serve to underscore the principles of participatory research and co-design, where students are encouraged to apply these principles to urban visions and architectural proposals (Constandius & Botes 2018). Following on the outcomes of the first module, students in the Honours year have the option to remain involved with their community partners in terms of design projects in the subsequent modules (Osman in Constandius & Botes 2018). Some of the Honours students also chose to remain involved with the second year implementation of the ECD play-space, which was a continuation of their urban vision. Critical reflection essays were prepared as an assignment at the end of the year, seven of which serve as the basis for this analysis (Schön 1983).

The overarching themes that could be identified from the essays were how the year had impacted on the students, how they were able to understand the context through their processes of engagement, and eventually, how this influenced their approach to design. Most of the students reported a significant shift in their perceptions of the township, which had been an unfamiliar place to them before. More significantly, however, a change in their normative position is described, in which a greater understanding of the people and conditions in the township required of them to accept limits within themselves, "unlearn and relearn" and to "give up control". In one case, a student described the process as 'daunting and intimidating' and that a greater commitment to architecture was required.

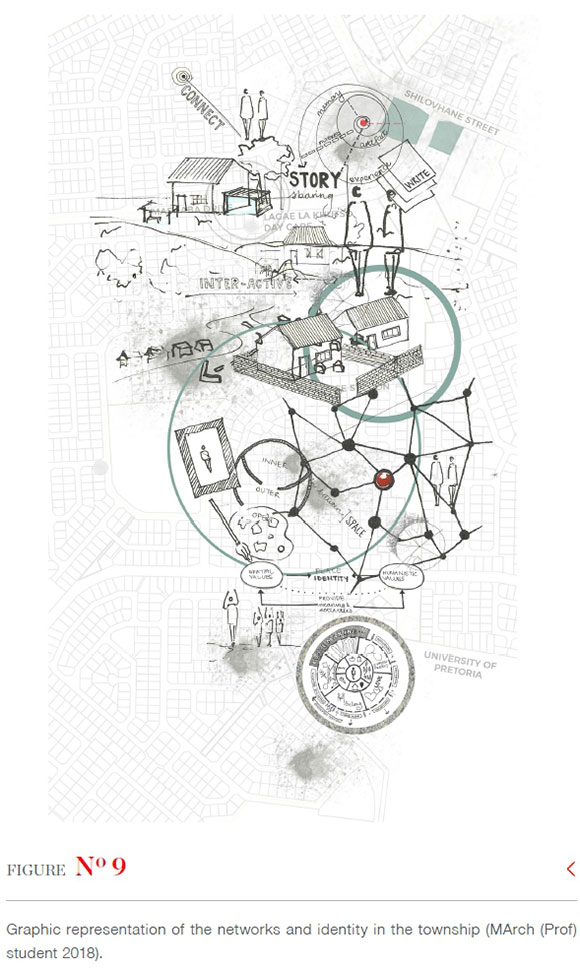

In all the essays, the students expressed an understanding of the context through the perspective of the residents, acknowledging the existing networks of association, co-operation, hierarchies and identity (Figure 9). The complexity of the systems encountered is noted, with deference paid to the tacit expert knowledge that was revealed through the mapping processes: 'Elders provided valuable knowledge about heritage'.

Eventually, the shift in position is reflected in the attitude to design, which in most of the essays favors an approach of enablement rather than prescription, where the architect assumes the position of catalyst for change rather than lead agent. Such an approach is described as relying on reciprocal exchange and collaboration that serves to engender a sense of ownership within the community.

These reflective essays serve to confirm clear evidence of the Honours students' progression into Perry's (1970) fourth position of development, where a moral commitment follows on the disorientation and possible loss of identity in the previous phase (Clarkeburn et al. 2003:447). From the initial introduction to the site, where students experience strangeness and discomfort, there is a distinct conclusion at the end of the year where resolution is found in "re-learning" or in the commitment to a newly defined normative position.

Such resolution brings together the combinatorial potential of 'thirding-as-othering' as expressed in the recurring themes of viewing the context through the eyes of the residents and choosing collaboration and enablement over traditionally prescriptive design practices (Soja 1996:60). In this, there is clear evidence of receptiveness to different perspectives as proposed by Lefebvre (in Soja 1996). By recognising the networked relationships and complexity of the found social structures, students display not only the capacity for openness to the "other", but also a reverence that serves to dismantle prior dominance of social values as described by Alice Sullivan (2002). This capacity for complexity therefore addresses the need to navigate the indeterminate spatiality of urban citizenship that is 'continuously in the making' (Blokland et al. 2015:656).

Vertical distribution of curricular participation

By considering the creative outputs of the four consecutive year groups in the same context, the dilemma of limited community engagement that lacks vertical and horizontal distribution has been highlighted, as students at various stages of intellectual and moral development experience the engagements very differently (Bringle & Hatcher 2009). A comparison between the video documentation of the second year group and the Honours group, who were all involved in the upgrade of the play area in front of the ECD, serves to underscore this difference.

Whereas the Honours students introduce the project by way of their immersion in the context and relationship with the community members, the second year students focus from the outset on the task at hand, include images of the community as bystanders, and eventually offer documentation of community members assisting with the task. Eventually, the motivation for involvement with the project is presented by the Honours students as contributing to the enablement of the community towards a greater vision (Figure 10), whereas the second years conclude their contribution as having improved found conditions through their actions.

The same play area was documented by the first years as the orienting node and landmark, and by the third years as the site for the road safety game. Where the first years emphasised the maypole-like structure of the electricity pole in the middle, this strong visual impression does not exist in the subsequent year groups, who focus on the physical improvement of this space (second years), the edges and potential of the square (third years), and the potential for community enablement through spatial activation by the Honours students.

Through these examples across the curriculum, it is therefore clear that there is a relation between the students' levels of development and their capacity to engage in an unfamiliar context. In terms of the Johnson and Morris (2010) framework for critical citizenship education, it is clear that levels of knowledge, skills, values and disposition cannot be achieved in single or simple engagements. Failing to make provision for the students' transition from one level to another therefore runs the risk of undermining their ethical and moral development in terms of participation, thereby falling short of achieving the levels of socio-spatial complexity required of urban citizenship (Clarkeburn et al. 2003).

Conclusion

Curricular engagement is intended to equip graduates with a sense of social responsibility, but is often restricted to a single opportunity, thereby failing to achieve the level of complexity required for meaningful participation, iteration, or reflection. Through an investigation into the creative outputs of four academic year groups in Architecture, the study has indicated that the development towards greater moral complexity in students can be seen in Perry's positions and Lefebvre's notion of lived space. From these findings, we argue that it is necessary to distribute curricular participation vertically throughout the curriculum to ensure that students are able to transcend from one level to the following in order to resolve the complexities they are confronted with in the spatial and ontological challenges inscribed within urban citizenship. Further investigation into horizontal distribution in trans-disciplinary work and longitudinal studies of vertical curricular integration would be required to confirm the impact on specific cohorts of students. The spatial injustices experienced in countries of the Global South require the critical and visionary contribution by professionals who are suitably equipped to engage with stakeholders that include those who have been marginalised through entrenched power relations. It is therefore imperative to consider the development of these professionals in terms of their socio-spatial capacity.

REFERENCES

Awan N, Schneider, T & Till, J. 2011. Spatial agency: Other ways of doing Architecture. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Baubock, R. 2003. Reinventing urban citizenship. Citizenship Studies 7(2):139-160. [ Links ]

Bauman, Z. 1997. The making and unmaking of strangers, in Debating cultural hybridity: Multicultural identities and the politics of anti-racism, edited by P Werbner and T Modood. London: Zed:46-57. [ Links ]

Blokland, T, Hentschel, C, Holm, A J, Lebuhn, H & Margalit, T. 2015. Urban citizenship and the right to the city: The fragmentation of claims. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (4):655-665. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. 1977. Cultural reproduction and social reproduction, in Power and ideology in education, edited by J Karabel and AH Halsey. Oxford: Oxford University Press:173-197. [ Links ]

Boyer, EL. 1996. The scholarship of engagement. Journal of Public Service and Outreach 1(1):11-20. [ Links ]

Bringle, RG & Hatcher, JA. 2009. Innovative practices in service-learning and curricular engagement. New Directions for Higher Education 147:37-46. [ Links ]

Clarkeburn, HM, Downie, JR, Gray, C & Matthew, RGS. 2003. Measuring ethical development in Life Sciences students: A study using Perry's developmental model. Studies in Higher Education 28(4):443-456. [ Links ]

Costandius, E & Botes, H. 2018. Educating citizen designers in South Africa. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. [ Links ]

Creswell, JW. 2003. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Cunningham, F. 2011. The virtues of urban citizenship. City, Culture and Society 2(1):35-44. [ Links ]

Davids, N. 2019. Citizenship can't be taught in a module. Mail & Guardian 6-12 Dec:33. [ Links ]

De la Rey, C, Kilfoil, W & Van Niekerk, G. 2017. Evaluating service leadership programs with multiple strategies, in University social responsibility and quality of life: A global survey of concepts and experiences, edited by DTL Shek and RM Hollister. Singapore: Springer:155-174. [ Links ]

Domingues, JM. 2017. From citizenship to social liberalism or beyond? Some theoretical and historical landmarks. Citizenship Studies 21(2):167-181. [ Links ]

Farganis, J. 1996. Readings in social theory: The classic tradition to postmodernism. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Finster, DC. 1991. Developmental instruction: Application of Perry's model to general chemistry. Journal of Chemical Education 68(9):752-756. [ Links ]

Grazioli, M. 2017. From citizens to citadins? Rethinking the right to the city inside housing squats in Rome, Italy. Citizenship Studies 21(4):393-408. [ Links ]

Holston. J. 2008. Participation, the right to rights, and urban citizenship. Princeton University Institute for International and Regional Studies: Urban Democracy and Governance in the Global South. [O]. Available: https://www.princeton.edu/~piirs/projects/Democracy%26Development/papers/Holston,%20Participation%20and%20Urban%20Citizenship.pdf Accessed 21 May 2018. [ Links ]

Huchzermeyer, M. 2011. Cities with 'slums': From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Johnson, L & Morris, P. 2010. Towards a framework for critical citizenship education. The Curriculum Journal 21(1):77-96. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. 1991. The production of space. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Lynch, K. 1960. The image of the city. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Meyer, WF, Moore, C & Viljoen, HG. 1997. Personology: From individual to ecosystem. Johannesburg: Heinemann Higher and Further Education. [ Links ]

Mitlin, D. 2013. A class act: Experiences with providing professional support to people's organizations in towns and cities of the Global South. Environment and Urbanization 25(2):483-499. [ Links ]

Mouton, J & Wildschut, L. 2005. Service Learning in South Africa: Lessons learnt through systematic evaluation. Acta Academica Supplementum 3:116-150. [ Links ]

Ngügï wa Thiong'o. 1992. Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature. London: James Currey. [ Links ]

Oldfield, S. 2008. Who's serving whom? Partners, process and products in Service-Learning projects in South African urban geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 32(2):269-285. [ Links ]

Perry, WG Jr. 1970. Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years: A scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [ Links ]

Purcell, M. 2009. Resisting Neoliberalization: Communicative planning or counter-hegemonic movements. Planning Theory 8(2):140-165. [ Links ]

Rabaka, R (ed). 2009. Africana critical theory. Lanham, ML: Lexington Books. [ Links ]

Schon, D. 1983. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. London: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Soja, EW. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Malden: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Sullivan, A. 2002. Bourdieu and education: How useful is Bourdieu's theory for researchers? The Netherlands Journal of Social Sciences 38(2):144-166. [ Links ]

Terre Blanche M, Durrheim K & Painter D (eds). 2006. Research in practice. Applied methods for the social sciences. Cape Town: UCT Press. [ Links ]

University of Pretoria Department for Education Innovation. 2012. Community Engagement Policy. Document number: UP_reg_1001e. [ Links ]

Winkler, T. 2013. At the coalface: Community-university engagements and Planning Education. Journal of Planning Education and Research 33(2):215-227. [ Links ]