Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.34 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a1

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a1

Extreme apartheid: the South African system of migrant labour and its hostels

Christo Vosloo

University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa cvosloo@uj.ac.za (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2212-1968)

ABSTRACT

The migrant labour system was an historical system used to reconcile the conflicting need for cheap labour in the mines and cities, with the apartheid ideology that workers should not reside there on a permanent basis. Labourers were housed in a unique accommodation type that developed from the Kimberley Closed Compound into the Witwatersrand Mine Compound and ultimately the migrant labour hostel. During the late colonial and apartheid periods, the mining compounds and the migrant labour hostels, which formed a key element of this system, were designed (and functioned) as tools of control and repression. In time they became synonymous with violence, overcrowding and squalor. As with so many other political and social systems, dismantling the migrant labour apparatus, and undoing the harm it caused, often requires even more tenacious efforts over a period of time.

Keywords: Migrancy; compounds; hostels; workers' housing; control; apartheid.

Introduction

The migrant labour system was an historical system, manipulated by capitalist, colonial and apartheid powers as a means of reconciling the conflicting needs for cheap labour in the mines and cities of "white" South Africa, with the desire to restrict black people to rural areas far away from the "white" cities. As part of this system, people (mostly men) were forced to migrate to places of employment but were not permitted to do so with their families or stay permanently, resulting in a system of oscillating migrancy (Posel in Bank 2017:6).

The hostels that formed a key element of this system were, and remain to this day, physical legacies of the systematic policy of racial discrimination and blatant economic exploitation of the indigenous people of South Africa (Hunter & Bundy in Ramphele 1993:15). This article briefly reflects on the South African migrant labour system in its historical context. By way of a literature study, the article provides a concise overview of the origin, history and current form of the migrant labour system. Furthermore, the forms of the three historical building typologies developed during the three distinct manifestations of this system are considered, namely the Kimberley Closed Compound, the Witwatersrand Mine Compound and the migrant labour hostel. This is because authors, such as Fassil Demissie (1998:445), have highlighted that current research largely ignores the aspects of architecture and spatial organisation that formed a critical part in the operation of the apartheid system. The forementioned aspects rely on information and images obtained from various museums in Kimberley and Johannesburg. The aim is to show that the Migrant Labour Hostels is one example where the legacy of apartheid planning and thinking continue to frustrate the ideals of social and physical transformation of our cities and society as a whole.

Design and spatial control

In 1785, the English philosopher and social theorist, Jeremy Bentham, proposed the idea of the panopticon - a design for a jail and a social control mechanism that became a symbol of authority and discipline (Butchart 1996:187). The principle behind the panopticon's design is the ability to survey the maximum number of prisoners with as few guards as possible. The layout comprises a central tower housing the guards; surrounding it is a ring-shaped building comprising a single layer of wedge-shaped prison cells (Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology & the Ancient World 2009:[sp]). The cells have one open side facing the guards. This allows the guards to see the entire cell at any time, leaving the prisoners vulnerable and visible, while prisoners cannot see into the central tower.

During the 1970s, the French philosopher, Michel Foucault, identified four design strategies through which authorities can achieve power in institutions such as prisons, asylums, schools and so forth. An important aspect of his theory is the link between visibility and power. The first of these design strategies revolves around the need to create "observatories" through the building's layout and spatial configuration. Spaces are designed and buildings arranged in such a way that it allows the observation of the inhabitants in order to get to know them, and through the awareness of being observed, ultimately alter their behaviour through self-policing. By arranging spaces in this way, the physical environment becomes a relay system that allows power to be exercised on the inmates by the authorities (Foucault 1977:78). In time, this power is internalised and the inmates exercise control over themselves without the need for external surveillance, thereby locking individuals into a permanent continuum of power and control (Foucault 1977:78). Panoptical layouts are the most obvious regime to accomplish this objective (Foucault 1977:195). However, disciplinary power can also be exercised by normalising judgement. The inhabitants are subjected to micro penalties and restrictions in the form of time, activity, behaviour, speech, the body and sexuality modifications, thus creating strict confines and understandings of what is acceptable and what is not (Foucault 1977:78). Strict routines coupled with punishment and incarceration are the means by which this aim can be achieved. The imposition of a disciplinary regime and a strict programme governing the sequence in which things are done is required; even the behaviour and sequence of bodily movements must be regulated (Foucault 1977:73-104). Finally, disciplinary power is created through examination - a combination of both hierarchical observation and normalising of judgement. In each of the variants of the migrant labour hostels that are reviewed in this article, these techniques were exercised as ways of controlling the workforce through power relations.

The South African system of migrant labour: a brief historic overview

Over a period of approximately 500 years, before the arrival of colonialists, a trade network developed across Southern Africa (Delius, Philips & Rankin-Smith in Delius 2017:1). A characteristic of this network was that men from the area, currently known as South Africa, had for centuries sought income and employment in places away from their homes by moving to other areas that formed part of this network (Delius 2017:2). Peter Delius holds that from about 1850, the growth of new economic centres and a demand for labour, caused by the rise of the commercial production of wool and the growing sugar cane industry in what is now KwaZulu-Natal, led to the first changes to this system. These changes eventually resulted in what became known as the migrant labour system, wherein colonial and postcolonial politicians and capitalists abducted the system to suit their own ends.

Much has been written about the migrant labour system since 1970, when Giovani Aright (in Delius 2017:11) postulated that it was the mingling of market forces and underdeveloped tribal economies that drew men into migrant labour. Delius (2017:12) contends that this argument became the backdrop for the debate that followed between the 'voluntarists' and the 'revisionists'. Whereas the voluntarists ascribed the phenomenon of migrancy in South Africa to market forces operating in the context of backward local economies in tribal areas, the revisionists stressed the critical role of conquest, dispossession of land, increasing taxes aided by draconian pass laws, centralised recruiting, compounds, and divide and rule tactics, in grappling for an understanding of the causes for the expansion of this system (Delius 2017:11-12). The debate was followed by a second wave of 'revisionists', including Harold Wolpe and Colin Bundy (in Ramaphele 1993:15), who argued that the need for cheap labour, as described previously, was the seed that spawned the systems of segregation and apartheid. This view is supported by many, including Francis Wilson (1972). Another theme that emerges from various writers is the need to control the movement and behaviour of migrant workers, in other words, the need to have a constant labour force, as well as to put a stop to illegal diamond trading and disorderly behaviour (Turrell 1987 & Van der Horst 1971 in Wentzel 1993:1-3). Control was uppermost in the minds of the segregationists within government, who sought to manage the influx of much needed "black" labour into "white" areas.

The migrant labour system evolved and flourished during a period that stretched over approximately 125 years, that is to say, from 1860 until 1985 (Wilson 1972:62; Cooke 1996:l).2 However, remnants of the system persist at various mine sites, with some of the migrant labour hostels remaining just as they existed decades ago, despite the post-1994 changes in government policy that sought to convert the sites into family housing. Many important writers emphasise the need to understand the dynamic interaction between the rural and urban aspects of migrants' lives. William Beinart (in Delius 2017:13) concludes that migrancy, in the South African context, stems from the dynamic relationships of power and authority in the rural areas, as well as from the demands of capital and politicians.

The debilitating impact of this system is well recognised. Delius (2017:12) concludes that,

There are few commentators today who dispute that the system was shaped by high levels of coercion or that it has had profound consequences for virtually every aspect of the lives of black South Africans. It has been long recognised that it had deeply destructive consequences for family life, as well as for peer group forms of socialisation. To this day, this toxic and intractable legacy remains a major impediment to positive processes of social and economic change.

As stated previously, the history of the migrant labour system can be divided into three distinct phases or types of institutions around which this paper is structured.

Origins

The traditional South African system of migrant labour, as described earlier, acquired a new dimension when Natal sugar farmers started importing temporary labour from India in 1860 (Wilson 1972:63). Later, around 1870, some Western Cape farmers attempted to solve their perennial labour problems by bringing in temporary workers from the Eastern Cape, Mozambique, Cornwall, and Germany. Concurrently, in the Eastern Cape, teams of sheep shearers became oscillating migrants in the more common seasonal mode, during shearing time.

By 1874, less than ten years after the discovery of diamonds, there were approximately 10 000 oscillating black migrant workers on the Kimberley diamond fields (Wilson 1972:63). Furthermore, by 1899, 13 years after the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand, the gold mines employed 100 000 black migrants (Wilson 1972:3). Julian Cooke (2007:64-68) describes the aims of the system as 'perhaps the most destructive social engineering of the country's history'. According to Cooke (2007: 67), a study of the system 'show[s] starkly how colonial and apartheid regimes used the spatial devices of jails or concentration camps to keep labour present and subservient, and in tandem with social regulation, created a divided and violent land'.

The Kimberley diamond fields

By the early 1880s, the newly created mining companies, who were the major employers on the diamond fields, were confronted by two weighty problems - illicit diamond buying (and selling) and theft (Ramahapu 1981:7). Alan Mabin (1986:120) adds to this list of issues: the attitudes prevalent amongst the pre-industrial workforce, the inability of the mine owners to control the workforce in the chaotic conditions that existed in the mining 'boom-town' of Kimberly, and the potential to manage the health of workers, thereby reducing absenteeism through a controlled environment. Responding to the fore mentioned problems was offered as the justification by the mine owners for creating the first compounds (Harris 1954). However, Rob Turrell (1982:2-8) has shown that the compounds were modelled on the convict stations that had already been established.3 Delius (2017:3) adds that the compounds also provided a means to reduce the costs of housing and feed the labour force. Furthermore, as highlighted by Mabin (1986:13), they allowed the mine owners to discipline the workforce. Thus, the real motivation for the introduction of the compounds were to reduce costs, as well as to ensure a constant and controllable supply of disciplined labour, while endeavouring to stop the illegal diamond trade.

The development of the closed compound was the work of Francis Thompson, a close friend of Cecil John Rhodes (Harris 1954:18). Cyril Harris (1954:19) relays that the plan was to completely isolate workers in the compounds for the entire period spent on the diamond fields in order to stop the leakage of diamonds. In addition, the compounds allowed the mine owners to secure sufficient workers for their needs (Delius 2017:2). Turrell (1982:7) summarises the situation as follows:

The rapid construction and commercialization of capital that underground mining required also dictated a more rigorous control of migrant labour, the unregulated scarcity and [seasonal] abundance which had persistently [hampered] the process of accumulation. It meant the closed compound system was the effective form in which the diamond mine owners came to terms with migrant labour.

Thus, the compounds were a response to the inefficiency of labour. They presented the mine owners with the mechanism to coerce labourers into reemployment, thereby establishing a pool of proficient labourers. Because they housed exclusively black labour, they limited interracial violence4 and made it easy to apply wage control. The combined effect of the compounds, the amalgamations between the mining companies, and the increased use of convict labour, resulted in a 60% drop in the weekly wages (Turrell 1982:5).

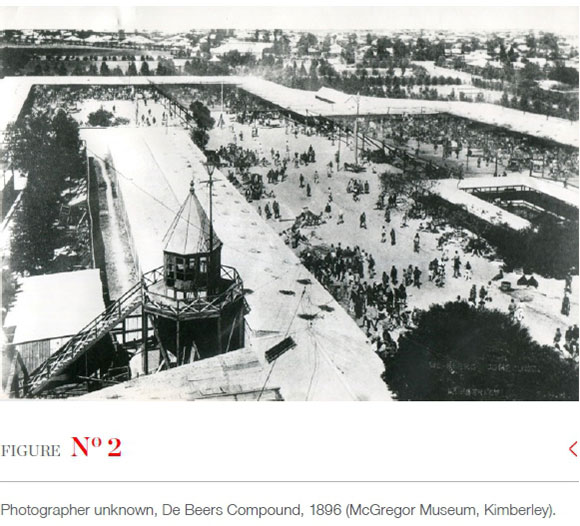

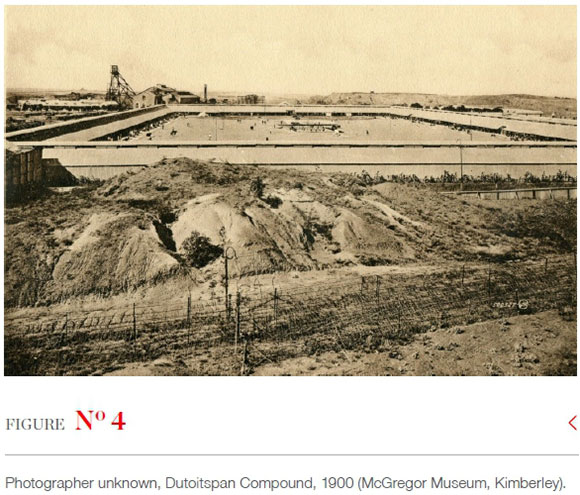

Each of the four compounds housed approximately 5 000 workers and covered an area of 25 acres (Harris 1954:18; Mazibuko 2000:22). Figure 1 shows the Bultfontein Compound wherein these architectural strategies of control are evident. Cooke (1996:2-8) holds that the physical isolation and the constant surveillance facilitated by the watch tower in the centre of the courtyard and the ten-foot high corrugated iron fence, made the required levels of control possible.

The watch tower can also be seen in Figures 2 and 4. Cooke (1996:2-8) relays how the compounds were organised around a central courtyard, typically rectangular in shape with three sides formed by rows of dormitories. The fourth side consisted of health, commercial, administrative and leisure facilities, and accommodation for a few white miners (see Figure 3). A well-guarded gate was the only link to the outside world.

and in addition, the perceived advantages of migrant labour, led the Witwatersrand gold mines to adopt aspects of this compound construct (Pearson 1975:i). The hostels were initially intended as places where migrants could recover from their journey and find housing close to the mine, while being shielded from the very high cost of living that prevailed on the Witwatersrand gold fields (Harris in Demissie 1998:453). However, the shortage of labour after the South African War, which ended in 1902 (Ramahapu 1981:2), and the need to use more sophisticated equipment as the mines became deeper, caused the mine owners to pay closer attention to compound security and efficiency. Thus, the open compound soon resembled the Kimberley prototype, but without the watchtowers (Demissie 1998:447).

Profitable mining of low-grade gold ore necessitated large quantities of cheap labour (Ramahapu 1981:1). The Chamber of Mines responded with urgent requests to the government to relieve the labour shortage (Moroney 1978:1). This resulted in the Transvaal Labour Commission of Inquiry in 1903 and the introduction of Chinese Indentured Labour in 1904. The mining industry itself responded by creating the Witwatersrand Native Labour Organisation, founded to co-ordinate their recruitment efforts and to unite on labour matters. The agreements that emerged from this organisation resulted in lower wages for workers, who were recruited mainly from the eastern parts of South Africa, and the Transkei and Ciskei regions of South Africa.

A tunnel, constructed to prevent any contact between miners forming part of changing shifts, was the connection with the mine itself. Some parts of the compounds were covered by overhead wire netting (visible in Figures 2, 5 and 6) to prevent anything being thrown out of the compound during or between shifts, in an effort to curtail diamonds being smuggled out of the mine precinct.

Each compound contained bakers, butchers, grocers (the workers had to cook for themselves), a dispensary, and a hospital (Harris 1954:18). Harris (1954:19) explains that the hostels included the so-called 'solitary cell system'. These cells were buildings with concrete floors, and walls with electric lighting. Workers at the end of their contracts were locked in these rooms after they were forced to undress and bath, after which, their hands were locked in leather fist-cuffs. They spent their last five days locked in this way to ensure that any diamonds swallowed or hidden anally were passed and left behind before they were escorted out of the city.

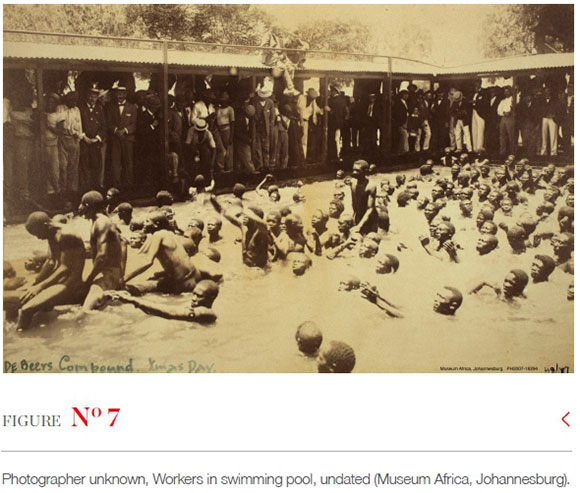

The layout shows a total indifference to any human concern, a quality also seen in the positioning of the compounds within the mine complex. They represented functional units, nothing but another piece of equipment, placed without any human intention or reference (Cooke 1996:22). The only concern for comfort was the swimming pools, as seen in Figure 7, where workers could cool off during the hot summer months, and which one could argue, were in fact merely a device to ensure continued productivity by preventing heat-exhaustion (Harris 1954:21).

The buildings, as illustrated, and the programme of activities conform to Foucault's (1977:195-207) 'measures to obtain power and control' by offering strict spatial partitioning, observation posts and continuous observation, spatial enclosure and the imposition of a strict routine and discipline. Thus, within the chaos that characterised the rapidly developing environment of the rush-years on the diamond fields, total control required physical enclosure, constant surveillance, and the functional autonomy of the mine companies to restrict, isolate and subdue the black workforce. In the 1970s, the great strides made in the mechanisation of the industry and the move to deep level mining brought the system to an end (Crush & James 1991:304305). Thus, the compounds of the Kimberly diamond fields were demolished, and no example of this reprehensible building type remains as a monument to the injustices that funded the wealth of the mining companies.

The Witwatersrand gold mines

Gold was discovered on the Witwatersrand in 1886, not long after the construction of the Kimberley compounds. The control that the Kimberley compounds provided, (Wilson in Bank 2017:7). Demissie (1998:445) regards the mining compounds that were designed in this way as 'an architectural discourse, a strategy of organising space and an institutional design which has emerged in various forms since the nineteenth century to discipline and regulate industrial labour'.

In addition, the mining industry's deceptive and coercive recruitment drives necessitated further steps to ensure that migrant labourers fulfilled their obligations. Amongst other things, they supported the re-institution of the Pass Laws and the Master and Servant Laws by the Transvaal Government. The reintroduction of these laws gave them the wide-ranging powers required to exercise full control over workers (Moroney 1978:1). They were also supported by the Native Service Control Act of 1932, and the Native Trust and Land Act of 1936 that followed (Demissie 1998: 450). Furthermore, the government incentivised rural men to look for work within the migrant labour system by introducing various forms of colonial taxes such as the 'hut and head' taxes (Demissie 1998:450-452).

Over and above the compound's controlling function, migrant labour also had two additional advantages for the mine owners (Murray 1981:26): Justifying the low wages paid by the mine owners who argued that wages were only a part of the total package offered to workers who essentially were farmers in need of additional income while also reducing the cost of mine establishment, since it obviated the cost of building family housing with its associated infrastructural implications (schools, hospitals and the like).

In addition, the compounds were used to 'protect' the white communities against the perceived threat of thousands of black male mineworkers staying in close proximity to them (Demissie 1998:458). A schematic representation of the compounds within their geographic context is shown in Figure 14. Thus, as with the diamond mines, the compounds (and migrant labour) were used because of the low costs and the control it offered the mine owners.

According to Patric Moroney (1978:1), the earlier compounds were quite rudimentary and unroofed. However, the shortage of labour after the war, and the need to use more sophisticated equipment as the mines became deeper, caused the mine owners to pay closer attention to compound security and efficiency. Thus, the open compound (see Figures 8 and 9) soon resembled the Kimberley prototype but without the watchtowers (Demissie 1998:447). Hence, additional measures aimed at ensuring complete control, including violence and coercion, could also be introduced. These actions depended on an environment of isolation, and the compound provided the requisite conditions. Additional measures aimed at optimising the output of the workers housed in the compound and reinforcing the envisaged power relations were also introduced. The first of these were the 'experimental chambers' and the 'heat tolerance test', introduced to screen incoming workers in order to select the 'best' candidates (Dresoti in Butchart 1996:187). Individuals were observed while performing strenuous work simulations, naked, and with the observers hidden behind glass screens (Dresoti in Butchart 1996:187). Alexander Butchart (1996:187) holds that these 'tests' were also used as 'instruments] of disciplinary power' as they constituted a 'ritual of dehumanisation, an exercise in debasement aimed at demonstrating the power of the mining industry over its African subjects'.

Efforts to reduce the rate of tuberculosis infection, the spread of which, according to Randall Packard (1989:67), was assisted greatly by the working and living conditions of the Witwatersrand gold mines, were also taken into account. Various restrictions and regulations were introduced in an effort to reduce the spread of this highly infectious disease that was impacting one of the mining industry's primary resources - cheap labour. These measures included space requirements and a call for close supervision. A noted publication of the time by Patric Pearson and Athur Mouchet5 (in Butchart 1996:194) suggested that,

The general features which we should seek to embow in any arrangement are those which conduce to easy supervision and maximum accessibility to all installations combined with a great degree of compactness as possible, in view of the necessity for avoiding too great proximity between natives.

Two notable features that resulted from these recommendations were the 'fan compound', a fan-shaped layout, that allowed visual observation (this was known as the 'dispensary gaze' and punted to reduce spitting) in a manner reminiscent of the panopticon (Butchart 1996:194), and the "rand" hut (see Figures 8 and 11). Here extensive use was made of ventilating lanterns on the ridgeline of dormitory rooms. This was done in an effort to reduce the spread of infections, since it was believed that infections were spread predominantly by carbon monoxide (Crush 1994:311). The fan-shaped layout became quite common in both the mining and migrant labour hostels. This realisation of Bentham's panoptical design not only allowed the designers to enable the 'maximisation of observation' but also to overcome the spatial limitations imposed by the rectangular courtyards of the early compounds (on the Reef and in Kimberley) (Crush 1992:6). It came to be that the levels of control provided by the Pass Laws and the Master and Servant Laws were augmented by the following internal control measures (Ramahapu 1981:2-8; Moroney 1978:3-5): The control of food supplies, a system of fines and incarceration, employment contracts which prevented labourers claiming against mine owners, implementing divide and rule tactics through the separation of the labourers along ethnic lines, strengthening tribal affiliations through traditional pursuits, such as competitive tribal dancing and by banning black trade unions. Aided by a repressive internal organisation and constant observation, punishment and dehumanisation, as described above, these measures laid the foundations for a system of total control (Foucault 1977:195-207). Furthermore, these measures reduced desertions and increased the output of workers.6

Other steps that were implemented to keep the inhabitants satisfied included allowing the brewing of traditional beer, providing a generous alcohol issue and liberal food rations, offering 'special passes' that allowed 'well-behaved' workers to exit the compound over weekends and providing limited married quarters (Demissie 1998:454).

Jonathan Crush (1994:309) provides the following description of the 1914 City Deep Compound by the Deputy Commissioner of the Johannesburg Police:

It is surrounded first of all by a galvanised iron fence. It has barbed wire at the top which prevents anybody from getting in or out ... The gates are so constructed that they have turnstiles by which each native can file in singly. The buildings are so constructed that from the gold compound manager's office he can see down any direction along the line of huts. The buildings are arranged like the spokes of a wheel with the office as a hub [and] by that means they are able to see exactly what goes on in the compound and practically almost in the rooms.

While the panoptical layout described above was exceptional in 1914, by the 1930s this layout had become more common, and by the 1940s it was the standard, as can be seen in Figure 12 (Crush 1994:309). However, in the 1970s the panoptic layout was discarded in favour of a more humane, park-like layout with less bleak living quarters (see Figure 13).

Crush (1994:308) adds that most compounds had 'stokkies', which are cells where wrongdoers could be locked-up, isolated, and punished for a few days at a time. Supervisory personnel enjoyed better accommodation, and this was separate from that of the ordinary workers (Crush 1994:310). Furthermore, accommodation was divided along ethnic lines.

While the form of the compounds varied considerably, a few common characteristics prevailed (Cooke 1996:8-14), for example:

• the Kimberley archetype, where workers were placed in isolation within the mine property

• the layout and siting were determined only by the efficient operation of the mine and ethnic separation

• single entrance controlled by mine police

• incorporating large, visible courts as circulatory and recreational spaces so that inhabitants could be observed most of the time

• the use of communal sleeping halls, and the meagre furnishing thereof, showed no concern for the human experience, or the individuality, identity, privacy, choice, and so forth, of the inhabitants

• communal ablutions, toilets and sleeping quarters

• sleeping areas housing 16 or more workers

Many of the features were changed in the later compounds, such as those on the Orange Free State gold fields (Cooke 1996:13), built after the 1960s, but the new layouts still aimed at ensuring isolation, division and observation. In essence, control remained the main objective (see Figure 11).

However, during the 1980s, as the apartheid era neared its inevitable demise, mines had to consider alternatives, not only as a result of political changes, but owning a range of factors, including technological changes that favoured skilled over unskilled workers (Crush & James 1991:304). The advantages of the migrant labour system no longer applied and high labour turnover, seasonal labour scarcity, high recruiting costs and labour indiscipline accumulated to turn this into an expensive option. Economic changes required that the mines increase their productivity, and mechanisation also became more common. At the same time, the main trade union, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) captured the compounds and used these institutions to organise and mobilise the workforce (Bezuidenhout & Buhlungu 2011:238). Family housing now became the preferred option, also owning to pressure from the NUM to abolish these institutions. However, the migrant labour system remains a fundamental aspect of mine labour. The compounds, or hostels as the mining companies now call them, continue as family housing for part of the workforce. The remainder of the migrant workforce are now paid living-out allowances which they use to rent backyard rooms in the informal settlements that have sprung up in the areas around the mines, a situation that has given rise to a whole range of new social problems (Reddy 2013:[sp]). The post-apartheid geographic context of the mine hostels is illustrated in Figure 15.

The migrant labour hostels

The dawn of the new political order in 1994 did not result in the disappearance of migrant labour, nor the migrant labour hostels, as many would have hoped. Noëleen Murray and Leslie Witz (2013:59) inform that most hostels have been converted into family accommodation. However, there are those that were torn down and the area used for conventional housing (Cooke & le Fèvre 2009 in Murray & Witz 2013:59). Some were simply refurbished and others, such as the Denver Hostel in Johannesburg and Diepkloof in Soweto, were left unaltered as migrant labour hostels. A few, such as Zwelihle, the AECI Labour Compound in Somerset West, were simply abandoned. Yet another few were turned into museums. These include the Newtown Compound (now the Workers Museum), KwaMuhle in Durban and Museum Africa in Johannesburg.

Historical overview

Browett (1982:14) regards that in colonial and apartheid South Africa, governments sought to contain the indigenous peoples in a subordinate position as labourers in the "white" economy. To achieve this ideal, the respective governments introduced legislation meant to control the urbanisation process of "natives". This included moving people off the land they were farming on and into the homelands to create reserves of available labour (Murray 1981:22-26).

The first such legislation was the Cape's Native Reserves Locations Act of 1902. This was followed by statutes passed in the Transvaal and Orange Free State aimed at augmenting legislation passed in the 1890s (Browett 1982:14). Nationally, the first pieces of legislation were the Native Labour Regulation Act of 1911 (Demissie 1998: 452) and the Urban Areas Act of 1923, following the recommendations of the Stallard Commission (Wilson 1972:100). These measures heralded the onset of the era of segregation (1923-1937)7 which resulted in influx control and segregated planning of cities and towns.

The second phase was the era of both confrontation and relaxation (1937-1948) following the passing of the Native Laws Amendment Act of 1937. This law saw an influx of stricter control measures. However, the industrial upswing following the outbreak of the Second World War soon forced the relaxation of these measures. The Group Areas era (1948-1968) commenced when the National Party government took power in 1948. Following the example of the mining industry, they realised that an oscillating migrant workforce could be controlled because of the possibility of sending home agitators and preventing them from returning to the urban areas. Hence, they rejected the moderate proposals of the Fagan Commission and passed the notorious Section 10 amendments to the Urban Areas Act of 1952 and the Bantu Laws Amendment Act of 1964 (Wilson 1972:101).

In practical terms, this meant that all black persons seeking employment in the "white" urban areas, had to obtain a pass from one of the labour bureaus in the Bantustans (Murray 1981:27). Should a suitable employment opportunity be available, the worker entered into a one-year contract. At the completion of this contract, he or she had to return to their area of origin and re-register as a job seeker. Thus, after 1968, workers who found work in the "white" areas, could never work or remain there permanently. In this way the migrant labour system came into being.

Anthony Lemon (1991:2) believes that the successful implementation of this system depended on control. Control encompassed managing the numbers, movement and socio-economic development of the migrants. To achieve such control, it was important to separate the migrants from black urbanites in general and to get them to be reliant on their employers. Lemon (1991:2) rationalises this as follows:

Focus of control imposed to maintain relations of dominance depend crucially on control of access to political power, but also included control of access to means of production and levels of employment, and to the means of employment (education, training and opportunity) of upward socio-economic mobility; control over land resources, their ownership, use and distribution; and over access to services and amenities; and control over special relations through segregation and urban containment. These controls were used inter alia to achieve minimal urban development, to contain forces threatening to economic and social interests (including health) of the dominant group, and to ensure that subordinate group housing was self-financing. Such controls [were] all characteristic of both segregation and apartheid cities in South Africa.

To affect this, the government took a leaf out of the mining industry's book and introduced hostels as standard accommodation for temporary workers. In doing so, the mining compound was used as the archetype (Murray 1981:26). Hence, they passed the Section 10 amendments to the Urban Areas Act. This forced many private companies and municipalities to construct their own hostels as accommodation for their migrant workforce (Cooke 1996:15).

A comprehensive system of isolation (and control) was thus put in place. The whole system sought to separate: urban from rural, men from women, fathers from their families, hostel dwellers from the urban population and ethnic groups from one another (Cooke 1996:15). Essentially, the climax of the divide and rule paradigm and apartheid had been reached. The migrant labour hostels were developed into the particular form of housing that would achieve the seemingly contradictory requirements that labour should both serve the requirements of industry whilst abiding by the constructs of separateness, exclusion and restriction (Moroney 1978:1). Thus, hostels became not merely a problematic form of housing, but also a problematic form of urban development and therefore, an urban planning problem.

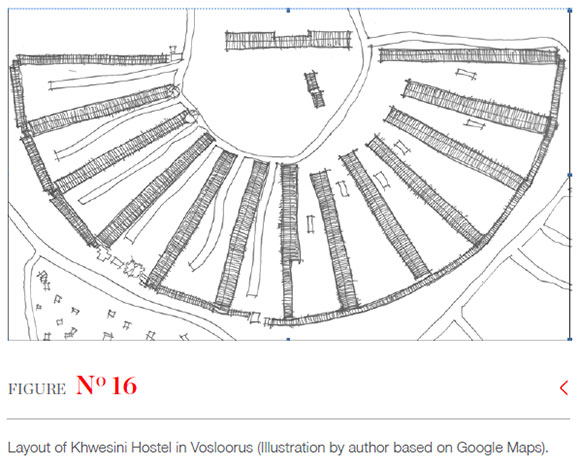

Initially, migrant labour hostels were modelled on their mining forerunners (see Figure 16). However, practical considerations meant that in time, they became quite different (see Figure 17), not only in relation to the precedent set by the design of the mine compounds, but also from each other, as some had to be situated in inner city areas. Most belonged to public authorities (municipal or provincial), for the purpose of housing oscillatory migrants who were employed (on contract) by a variety of employers or the municipality itself. Large state-owned organisations, such as the railways, also constructed hostels in which to house their own migrant labourers. The fact that they worked in the general economy for a variety of employers necessitated a degree of freedom of movement for residents. Hence, the physical control measures could not be used, requiring that these measures be replaced by a complex framework of statutory restrictions. Many also included facilities where those who transgressed were locked up and punished. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that in some cases, the hostels had to be invisible so as not to unsettle the white inhabitants of the apartheid city (Murray & Witz 2013:54).

These changes meant that their layout and design varied greatly. However, many had the following features in common (Cooke 1996:16-22):

• ideally, they were situated away from the surrounding urban fabric, particularly the townships. They were separated by substantial vacant buffer spaces, or other features such as walls, main roads, railway lines, beer halls, and so forth

• the differences in scale and density highlighted the difference between this form of housing and the surrounding townships and suburbs

• as with the mining compounds, they were positioned insensitively as functional elements in the urban landscape

• they were placed to provide relatively easy access to the commercial and industrial areas or to means of transport such as railway lines, main routes, and so forth

• they bore no likeness to anything fit for human housing and there was no attempt to soften the harsh environment

• they represented simplistic, mechanical attempts to fit the maximum number of units onto a given piece of land

Gavin Woods (1993:65) identifies the following common physical features of hostels:

• most are located on the edges of the black townships of the apartheid city

• they are large, brutal, impersonal structures that resemble face-brick prisons or barracks

• they could be single- or multi-storey

• their interiors are austere and neglected

• they are inadequate facilities mostly in poor state of repair

• communal kitchens are used for other purposes, typically as storage

• they consist of rooms housing between 6 and 16 beds, often with a permanent brick base topped by concrete or wooden tops without mattresses

• they have the built-in beds that restricted flexibility

• the rooms usually contained no more than beds, and only in some cases a small table next to it

• they have narrow, dark and dingy corridors with rough concrete floors, poor lighting and grubby walls

• there are overflowing drains

An early example, the Newtown Compound in Johannesburg (currently the Workers Museum), had a row of north-facing houses (with staff quarters) for white staff while the 300 workers, employed by the Johannesburg Municipality, were accommodated in a U-shaped building with the manager's office dominating the courtyard, controlling access and egress. The workers were housed in rooms that contained rows of two-tier bunks on either side (see Figure 18).

The bottom shelf was made from concrete while the top shelf was in wood. No lockers or mattresses were provided. A central mbawula or coal stove was the only comfort provided. Ablutions were outside and comprised a room equipped with open "squat pans" (see Figure 19) and open showers. The building also had a lock-up room which was used to lock up workers who disobeyed any of the many rules that controlled their lives. The compound manager sentenced disobeying workers to this room for a couple of hours or even an overnight sentence. It had a heavy iron ring in the wall to which workers were sometimes chained. There was a bucket that could be used for a toilet.

The Lwandle Hostel, the Khwesini Hostel in Vosloorus, and many others, adopted the panoptical layout seen in the design of the gold mine compounds (see Figures 12 and 16), but the need for higher densities meant that some, such as the Wolhuter Hostel in Johannesburg, had to adopt alternative forms (see Figure 17). Noëleen Murray and Leslie Witz (2013:56) describe one such hostel, the Lwandle Hostel, built in 1977 near Somerset West as follows:

Designed in a linear manner, configured in parallel rows of double- and single-storey structures, the hostel blocks were laid out around a central core space in a chevron-type pattern, allowing for 'clear lines of sight' along the rows. In each row there were a number of units. Each unit had a single exit/entrance, was divided into two rooms and each of these further subdivided into four small, confined individual compartments containing two or four beds, with up to 32 men in a hostel block, their lives effectively reduced to a "bedhold" (Ramphele 1993:22). Each unit had an outside latrine block with open cubicles that made use of the bucket system, and in close proximity were communal kitchens and showers.

To summarise, the compounds and the hostels established a form of development that controlled and restricted the inflow and residence of the black labour force through isolation and oppression. At the same time, it established a unique form of urban development that has become an inherent part of the South African urban fabric. However, as stated before, the repeal of the policies and legislation which had created these inhumane environments did not result in their demise or disappearance, and many continue to exist as problematic blotches in the urban environment.

The key problems associated with the migrant labour hostels are (Vosloo 1998:36): Firstly, the isolation of the complexes in their urban environments and the divide (physical and social) experienced by their inhabitants who are isolated from both their rural support base and the urbanites that live around them. Secondly, the isolation of the complexes in their urban environments and the seperation (physical and social) experienced by their inhabitants who now are isolated from both their rural support base and the urbanites that live around them. Thirdly, the violence associated with these institutions, both internally and in relation to their urban surroundings. Fourthly, the poverty and squalor so common in these complexes. Fifthly, the form of housing they offer their inhabitants which falls short of minimum standards concerning space, privacy and safety and finally, the conflicting and unrealistic expectations prevalent amongst their inhabitants which complicates redevelopment projects

Current situation

Influx control was finally abolished in 1986 (Ramphele 1993:17). This resulted in drastic changes for the various hostels. By 1991, the hostels had developed in a variety of different ways (Smit 1991:8). In many of the hostels in Gauteng, their isolation and unique demographic profile turned them into the barracks of particular, mostly traditional, political groupings (Cooke 1996:3; Minnaar 1993:10-48). Woods (1993:6480), as well as Trevor Payze and Catherine Keith (1993:48-64), have shown how their distinctness fanned the violence that followed these changes, and became one of the recurring issues connected with the hostels during the transition to democracy. They also highlight how many became overpopulated when the families of hostel dwellers, and other employment seekers in need of temporary or permanent accommodation, moved into them (Payze & Keith 1993:52).

In many cases, the political changes in the country saw the collapse of the apartheid era control mechanisms that had managed and maintained the hostels (Clarke 1994:10). As a result, the residents set up their own managerial structures. However, these structures did not have the means to cope with the numbers that had to be accommodated. The combination of the abovementioned factors resulted in the deterioration of the physical conditions of the buildings and services (Payze & Keith 1993:54). Thus, while the hostels at no time provided acceptable housing or living conditions, the remaining ones are now in an even worse state.

The situation was aggravated by their new demographic profile, as men-only hostels were now accepting women and children. To make matters worse, the deterioration of the general socio-economic situation, brought about by years of low financial and economic growth, resulted in widespread unemployment and serious poverty (Woods 1993:66). The change in their socio-economic and socio-political contexts have also led, in many cases, to an increase in isolation, alienation and the marginalisation of their inhabitants who often supported the Inkatha Freedom Party, while the surrounding communities supported the African National Congress (Morris & Hindson 1992:152170). As a result, the hostels that have not been redeveloped, such as the Denver Hostel, remain as bitter physical legacies of apartheid: islands needing effective redevelopment and integration into their surrounding urban fabric (Davies & Goldschmidt 1994:8). In 1996 the National Housing Forum (NHF) (1996:117) pointed out that the hostels are regarded differently by various groups - for some they are a reminder a bitter past; for others they are prized shelters in a sea of homelessness. Some further see them as a central part of the system of circulatory migration, which they would like to maintain; while for most people, their forms and conditions represent an urban aberration. This remains the case.

BW Dhlamini (2012), writing in the Mail & Guardian, attributes the vestiges of the problem to government policy, which does not understand the complexity of the problem and regards it in isolation of the wider housing and urban problem. Dhlamini (2012) holds that the government still sees hostels as temporary structures providing temporary housing, rather than homes that could provide starting capital for their inhabitants. This attitude persists despite the warnings from many, such as Smit (1991:15), that interventions need to take the broader issues, such as the urbanisation and housing processes of surrounding areas, into account. These hostels remain as a continuing phenomenon, proving that the simplistic explanation that the migrant labour system was a form of gradual urbanisation under a restrictive political order is equally simplistic (Mabin 1990:312). A more plausible explanation could be that the mining companies and apartheid governments, in a most atrocious manner, hijacked a traditional system for their own advantage. Even though these drivers are no longer encouraging this phenomenon, however, some of the factors and traditions, referred to in Section 2, that supported and allowed this to happen, are still at play.

Conclusion

It would be difficult to argue that those who planned and developed the migrant labour system did this to achieve all the disabling effects it had, and continue to have, on the black (African) population of South Africa. Hence, many of the conditions must be seen as unintended consequences. An example of this is the fact that the system carried the seed that would result in its own destruction; it made it easy for resistance forces to organise inside the confined space. Another example is the fact that in some cases, these institutions became vestiges of opposition political parties and groupings and that the open spaces around them became informal settlements, exclusively housing supporters of the same opposition parties. This happened in the case of the Denver Hostel which houses almost exclusively supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party. However, what is true is that they designed a building typology that facilitated the subjection of large parts of the black (African) population and this enabled a white minority to rule the country for as long as it did.

Separation at various levels (geographic, gender, social, economic, racial, tribal, nuptial) was a core theme in the thinking that created this abhorrent system. Therefore, treating the problem in isolation of the broader urban and housing problems, and without considering the diverse needs of society, represents a continuation of this superficial and simplistic level and type of thinking. Wishing it away by implementing policies to redevelop these institutions into family housing will not solve the problem either, particularly in view of the continuing general housing crisis, the need for urban transformation, as well as the need to create housing at greater densities, located closer to the central parts of South African cities.

The mining compounds and the migrant labour hostels were designed (and functioned) as tools of control and repression. As with so many other political and social systems, dismantling the system and undoing the harm it caused often requires an even more tenacious effort over a period of time. Sue Rubenstein and Neil Otten (1996:150) conclude that the challenge is for 'all the actors in the hostel arena to think beyond the narrow confines of grimy hostel walls and to develop bold, ap propriate and creative responses' that will move South Africa away from the current situation.

Notes

1. This article was developed from Vosloo, C. 1998. The migrant labour hostels: A physical planning strategy for the re-development of the Mathew Goniwe Hostel. Unpublished MArch dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

2. Or until 2014, according to Delius (2017:1). The difference in timespans could be because Cooke (1996) refers to the official policy while Delius (2017) includes the period after the official repeal of the policy in which the social momentum created by the policy led to its continuation.

3. According to Turrell, the mines before the establishment of the compounds used a combination of convict and unregulated labour.

4. White mineworkers were accommodated separately (Mabin 1986:17-18).

5. See Pearson and Mouchet (1923).

6. For a detailed description of how these conditions were established, refer to Moroney (1978), Ramahapu (1981), Pearson (1976) and Cooke (1996:8-14).

7. This classification is based on Lemon (1991:126), Davenport (1991:1-19), Posel (1991:19-33) and Mabin (1991:33-48).

REFERENCES

Afrikana Library. 65 Du Toitspan Rd, Kimberley, 8301. www.africanalibrary.co.za. [ Links ]

Bank, L. 2017. Migrant labour in South Africa. Paper presented at Migrant Labour in South Africa: Conference and Public Action Dialogue, 7-8 February, University of Fort Hare, East London Campus. [ Links ]

Bezuidenhout, A & Buhlungu, S. 2010. From compound to fragmented labour: Mineworkers and the demise of compounds in South Africa. Antipode 43(2):237-263. [ Links ]

Browett, J. 1982. The evolution of unequal development within South Africa: An overview, in Living under apartheid, edited by DM Smith. London: George Allen and Unwin:10-23. [ Links ]

Butchart, A. 1996. The industrial panopticon: Mining and the medical construction of migrant African labour in South Africa, 1900-1950. Social Science and Medicine 42(12):185-197. [ Links ]

Clarke, V. 1994. The international context. Hostel initiatives: An urban reconstruction and development perspective. Johannesburg: Development Bank of South Africa. [ Links ]

Cooke, J. 1996. The anatomy of the migrant labour hostels. Unpublished research paper, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Cooke, J. 2007. The form of the migrant labour hostel. Architecture South Africa July/ August:64-69. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 1992. The genealogy of the compound. Paper presented at the 8th International Conference of Historical Geographers, 16-21 August, Vancouver. [ Links ]

Crush, J. 1994. Scripting the compound: Power and space in the South African mining industry. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 12:301 -324. [ Links ]

Crush, J. & Wilmot, J. 1991. Depopulating the compounds: Migrant labour and mine housing in South Africa. World Development 19(4):301-316. [ Links ]

Davenport, R. 1991. Historical background of the apartheid city to 1948, in Apartheid city in transition, edited by M Swilling, R Humphries & K Shubane. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Davies, G & Goldschmidt, K. 1994. Integrating hostels into communities. Hostel initiatives: An urban reconstruction and development perspective. Johannesburg: Development Bank of South Africa. [ Links ]

Delius, P. 2017. Migrant labour in South Africa (1800-2014). Oxford research encyclopaedia of African history: Economic and social history, Southern Africa. [O]. Available: http://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-93 Accessed 24 April 2019. [ Links ]

Demissie, F. 1998. In the shadow of the gold mines: Migrancy and mine housing in South Africa. Housing Studies 13(4):445-469. [ Links ]

Dhlamini, BW. 2012. Hostels must be integrated into inclusive housing policy. Mail and Guardian. [O]. Available: https://mg.co.za/article/2012-06-07-hostels-need-to-be-integrated-into-an-inclusive-housing-policy Accessed 24 April 2019. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Google Maps. 2019. Khwesini Hostel. [O]. Available: https://www.google.com/maps/@-26.3671869,28.1493744,477m/data=!3m1!1e3 Accessed 23 April 2019. [ Links ]

Harris, CB. 1954. How the compound system came into existence in Kimberley. The Diamond News and the South African Watchmaker and Jeweller August:18-21. [ Links ]

Internalized authority and the prison of the mind: Bentham and Foucault's panopticon. 2009. [O]. Available: https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/courses/13things/7121.html Accessed 25 November 2019. [ Links ]

Lemon, A (ed). 1991. Homes apart: South Africa's segregated cities. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 1986. Labour, capital, class struggle and the origins of residential segregation in Kimberley, 1880-1920. Journal of Historical Geography 12(1):4-26. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 1990. Limits of urban transition model in understanding South African urbanisation. Johannesburg: Development Bank of South Africa. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 1991. The dynamics of urbanisation since 1960, in Apartheid city in transition, edited by M Swilling, R Humphries & K Shubane. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mazibuko, RP. 2000. The effects of migrant labour on the family system. Unpublished Master's degree dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

McGregor Museum. P.O. Box 316, Kimberley, 8300. www.museumsnc.co.za. [ Links ]

Moodie, D. 1994. Going for gold: Men, mines and migration. Berkley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Moroney, S. 1978. The development of the compound as a mechanism of worker control: 1900-1912. Paper presented at the Wits History Workshop: The Witwatersrand: Labour, Townships and Patterns of Protest, 3-7 February, University of Witwatersrand. [ Links ]

Morris, M, & Hindson, DC. 1992. The disintegration of apartheid: From violence to reconstruction. The South African Review (6):152-170. [ Links ]

Murray, C. 1981. Families divided: The impact of migrant labour in Lesotho. Raven: Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Murray, N. & Witz, L. 2013. Camp Lwandle: Rehabilitating a migrant labour hostel at the seaside. Social Dynamics 39(1):51-57. [ Links ]

Museum Africa. 121 Bree Street, Newtown, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

National Housing Forum. 1996. Booklet 7: Hostels. The National Housing Forum: Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Packard, RM. 1989. White plague, black labour: Tuberculosis and the political economy of health and disease in South Africa. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Payze, C & Keith, T. 1993. Everyday life in South African hostels, in Communities in isolation: Perspectives on hostels in South Africa, edited by A Minnaar. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council:48-64. [ Links ]

Pearson, A & Mouchet, R. 1923. The practical hygiene of native compounds in tropical Africa. London: Bailliere, Tindall and Cox. [ Links ]

Pearson, P. 1976. Authority and control in a South African goldmine compound.Unpublished paper delivered to African Studies Seminar. African Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Posel, D. 1991. Curbing African urbanisation, in Apartheid city in transition, edited by M Swilling, R Humphries & K Shubane. Cape Town: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Ramahapu, TV. 1981. The controlling mechanisms of the mine compound system in South Africa. Maseru: Institute of Labour Studies. [ Links ]

Ramphele, M. 1993. A bed called home: Life in the migrant labour hostels of Cape Town. Cape Town: David Phillip. [ Links ]

Reddy, M. 2013. Migrant Marikana: The shifts in the migrant labour system. Amandla! 32:[sp]. [ Links ]

Rubinstein,S & Otten, N.1996.Towards transformation: Lessons from the Hostels Redevelopment Programme, in A mandate to build: Developing consensus around a national housing policy in South Africa, edited by K Rust and S Rubenstein. Johannesburg: Raven Press:138-151. [ Links ]

Smit, D. 1991. From anonymity to notoriety: Hostels in South Africa. Booklet 7: Hostels. The National Housing Forum: Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Turrell, RV. 1982. Kimberley: Labour and compounds, 1871-1888, in Industrialisation and social change in South Africa: African class formation, culture and consciousness 1870-1936, edited by S Marks & R Rathbone. London: Longman:2-8. [ Links ]

Turrell, RV. 1987. Capital and labour on the Kimberley diamond fields, 1871-1890. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Vosloo, C. 1998. The migrant labour hostels: A physical planning strategy for the redevelopment of the Mathew Goniwe Hostel. Unpublished MArch dissertation, University of Cape Town, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Wentzel, M. 1993. Historical origins of hostels in South Africa: Migrant labour and compounds, in Communities in isolation: Perspectives on hostels in South Africa, edited by A Minnaar. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]

Wilson, F. 1972. Migrant labour. Johannesburg: South African Council of Churches and SPROCAS. [ Links ]

Woods, G. 1993. Hostel dwellers. A socio-psychological and humanistic perspective: Empirical findings on a national scale, in Communities in isolation: Perspectives on hostels in South Africa, edited by A Minnaar. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council. [ Links ]