Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.33 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a13

Persistence of the past and the here-and-now of the Union Buildings

Alan Mabin

Emeritus Professor, School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa alan.mabin@wits.ac.za | https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3191-2056

ABSTRACT

In their presence and continued use as seat of government, the Union Buildings in Pretoria reveal the persistence of the past in a prime space of power and official commemoration in South Africa. The paper focuses on the retention of these segregation-era buildings as the "top" site of government in the context of Tshwane, or Pretoria, in the democratic era from 1994. The paper traces events and actions through several periods since the Buildings were conceived in 1909, to and beyond the inauguration of President Mandela at the site. Some alternative views on continued use of the buildings are explored. The argument of the paper is that urban collective memory in which monuments such as the Union Buildings stand, is constantly remade, and the meanings ascribed to the images evoked by such an edifice shift into sometimes radically different directions from those held in earlier periods.

Keywords: Union Buildings; monuments; colonial nationalism; here-and-now.

A monument reluctant to fall

This paper explores the persistence of the past in a prime space of governmental administration and official commemoration in South Africa. It focuses on the Union Buildings and poses the question of their retention as the "top" site of government in the context of Tshwane - the metropolitan municipal area of Pretoria - and in the democratic era from 1994. The point of departure lies in the days of the apartheid regime's efforts to deepen and extend its power against growing opposition, in the 1980s, which for many might suggest that the edifice represents the oppressions of the past. The image, uses and effects of the site are then followed through several periods, beginning from the origins of the Buildings and traversing several periods since. The argument of the paper is that urban collective memory, in which monuments such as the Union Buildings stand, is constantly remade, and the meanings ascribed to the images evoked by such an edifice shift into sometimes radically different directions from those held in earlier periods, reflected in texts from diverse quarters. In the case of the Union Buildings the consequence appears to be that far from calling for their fall as "seat of government" in a democracy, the complex plays a heightened role in the symbolism and imagination of the country.

Just after his "security" agents blew up Jeanette Curtis Schoon by parcel bomb in Lubango, Angola (28 June), and shot dead Bongani Khumalo, COSAS leader, in Soweto (13 September), President PW Botha unveiled the Police Memorial on 17 October 1984, just below the eastern flank of the Union Buildings in the corner of the gardens. The cornerstone of the memorial had been laid on 20 May 1983 by the Commissioner of the South African Police, Genl. MCW Geldenhuys. The architects were Maree and Sons.

The monument, in the form of a small amphitheatre, has three principal elements: a solid enclosing wall two metres high, which represents the duty of protection performed by the police, a higher wall, which encloses a curved row of columns representing the various branches of the police, and link with history provided by a breach in the protecting wall through which the Voortrekker Monument is visible across the city. Bronze plaques bear the names of police officers who died whilst performing their duty, and every year the addition of new names is dedicated through a special memorial service in honour of those who gave their lives in the fight against crime (Department of Public Works 2007:17).

The Police Memorial is a difficult subject to handle, for it is a site of grieving for many people, especially families of police who have died in service. I do not wish to indicate any disrespect for the bereaved or the deceased. Yet its continued presence across the historical divide between the era of official apartheid and the era of electoral democracy poses a paradox, and provides a stark example of old monuments that have not been ruined in the passage to greater freedom in South Africa. On my first close inspection of the memorial, on 3 September 2014, a few days before the annual commemoration event at the memorial that takes place each year on the first Sunday of September, I was struck by the seamlessness of the representation of these tragic deaths before and after democracy dawned in the country - elections on 27 April and inauguration of Mr Nelson Mandela as president on 10 May 1994.

This method of recording police service deaths continues up to the present, as does the annual commemoration. In 2015 then-President Zuma spoke at the event, in 2017 then-Deputy President Ramaphosa, and on 2 September 2018, the Minister of Police. Thus the memorial, far from having fallen, surmounts the divide between past and present regimes, and is incorporated into practices of the consolidated and renamed South African Police Service.1 I am not aware of any negative critique of the memorial or of the commemorative practices: though it's quite possible that such exists, at least in less public conversation. Certainly I think its origins in the PW Botha era are dubious and its design and style could easily be problematised, but presently there is no call for it to fall.

The Police Memorial captures elements of many monuments:

... collective memory is shaped by the politically contestable nature of place... Every memorial's placement and relative location may confirm, erode, contradict, or render mute the intended meanings of the memorial's producers. A memorial's placement refers to the specific condition of its site, e.g., its visibility, accessibility, symbolic elements, and its adjacency to other parts of the landscape (Dwyer & Alderman 2008:168).

The memorial, of course, stands in the grounds of the Union Buildings, a placement which must affect the way the monument shapes visitors' responses. I would hazard from informal observation on many visits since 2014 that only a tiny proportion see the Police Memorial, out of the many who visit the Union Buildings and pose for photos with the large statue of Mandela which has been in place since unveiling on 16 December 2013, eleven days after his death and just over 100 years since the completion of the Union Buildings. A statue of 1924-1939 Prime Minister Hertzog was moved to the treed area at the east side of the gardens below the Police Memorial, to make way for the Mandela statue, so some past monuments have altered. Walking away from the Police Memorial with an oblique view of the Union Buildings, thoughts turn to why this "colonial" or perhaps more accurately "settler colonial" edifice still stands proud on Meintjieskop, and further, why this place is called "the seat of government" in the era of a post-apartheid regime. That is the question the paper proceeds to explore.

To the Buildings

Like an ancient temple adorning over the city it governs, the Union Buildings are a modern day acropolis, built at the highest point of South Africa's capital city, Pretoria, it forms the official seat of South Africa's government and houses The Presidency (The Presidency 2019).2

Views on the Union Buildings are varied. Numerous bodies, as with the Presidency, offer paeans of praise for the Union Buildings such as:

The Union Buildings are considered South Africa's architectural masterpiece (SA History Online 2019).

An important South African heritage site, the impressive building is surrounded by pretty terraced gardens that offer panoramic views over the city (Gauteng.net 2019).

Traversing events at the Union Buildings in varied periods, we might pause to reflect on the Afrikaner women's gathering in August 1915 calling for release of Christiaan de Wet and other rebels; the 1940 march, again by Afrikaner women protesting South Africa's engagement in the war against Nazism; the rather more famous Women's March of 1956 (Kros 1980); the funeral of Prime Minister Verwoerd in 1966; the inauguration of President Nelson Mandela in 1994; and his posthumous lying in state in 2013. The powerful presence of the Union Buildings and its current use could engage with parallel or intersecting debates about places of post-oppressive-history government in other countries, with themes of nostalgia (Dlamini 2009), rupture and continuity, and in commemorative forms in the twenty-first century - both through specific events and through monuments old and new, particularly those situated at the Union Buildings. These include war memorials, the Women's Monument (Becker 2000) and the continued use of the PW Botha-inspired Police Memorial.

One of the last acts of the outgoing government was declaration of 'The property with the Union Buildings thereon, including the memorials of Delville Wood and the Second World War, as well as the statues of generals Louis Botha, Jan Smuts and JBM Hertzog', as a national monument by Government Notice 605, published in Government Gazette 15593 of 31 March 1994 (Department of Public Works 2007:20). For many decades a place to see, the Department of Public Works noted 'The Union Buildings is already a major tourism attraction, although this has not yet been exploited to its full potential. Visitors regard it as one of the "must see" items on their travel itinerary and South Africans from other provinces see the Union Buildings as a symbol of a new nation' (Department of Public Works 2007:34).

Most accounts of the edifice note the elements of the architecture that

was designed to celebrate the achievement of the Union of South Africa in 1910 after years of strife, civil war and division amongst the settler population. But the reconciliation that took place in order to achieve this union excluded the majority of the population of South Africa, the blacks. The vision of the new state of that time was therefore narrow, racist and elitist. Despite its negative historical context, Union Buildings has already acquired a meaning, which transcends adverse associations, for it was this site, which was chosen for the inauguration of our first democratically elected President on 10 May 1994. In that sense, and in that day, Union Buildings was again appropriated, this time by the entire, liberated population of South Africa (Department of Public Works 2007:36).

I have previously noted that the Union Buildings' 'insertion of local elements and use of materials makes it a perhaps unlikely but highly successful centre for the power of post-apartheid government. Unlike the monuments of Washington or Brasilia, this is not a building which symmetrically dominates the city. It almost awkwardly faces only its own grounds' (Mabin 2011:180). To accomplish its apparently widely accepted place in democratic South Africa, some claim that 'it was the act of Nelson Mandela stepping across the threshold of the Union Buildings ... as the new president ... which effectively rinsed those buildings of their tarnished associations with a government of apartheid, and re-appropriated them for the new South Africa. In doing so Mandela effectively 'recoded' these buildings' (Leach 2002b:93).3 Perhaps Leach treated symbolic cleansing as too individual, for not all would agree. As a participant observer,

I would venture that it was the 100 000 strong crowd on 10 May 1994 and their response to the events of that memorable occasion who moved the image of the Buildings into a new phase.

For some, the Union Buildings were controversial from the start. Whilst they were being built, prior to the 31 May 1910 declaration of the Union of South Africa from four former British colonies subsequent to the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 and several years before their completion in 1913, a proto-nationalist commentary complained (De Volkstem, II January 1910, cited in Department of Public Works 2007:35):

We rather grant a hundred times over the young Union of South Africa a government palace in Pretoria that is full of mistakes and problems but sparkles of South African character, than a perfect product of foreign architectural techniques from the hand of an imported foreign architect.

The 'imported foreign architect', as is very well known, was (Sir) Herbert Baker, who had moved to Cape Town from England in 1892 and lived there for a decade, relocating to Johannesburg where he resided for another decade prior to his commission with Edward Luytens to design government buildings in New Delhi. A protégé of Rhodes, he designed the temple-like Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town; intriguingly that structure is still intact, whereas the Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town below the monument, became the centerpiece of the 'Fallist' decolonial movement in 2015 (Kros 2015).

A foreign architect yes - one who designed prominent buildings still in post-colonial use in several parts of the world, not least in New Delhi and Nairobi. Those buildings pose their own paradoxes, but here the apparent contradictions of the Union Buildings are the main concern. Denis Radford (1985) suggested that Baker's design was greatly influenced by the Londoner Luytens, even less an indigenous architect - for although from outside, Baker had lived in South Africa for two decades. Certainly it is common cause among critics that Baker's 'exposure to the classical world [of Greece and Rome] ... had transformed his design philosophy' (Foster 2008:160). His 'politically engaged architecture', some have suggested, was 'not so much ... "architecture that established a nation" as an "architecture expressive of the ideals of the British Empire"' (Foster 2008:160). Yet that architecture had to produce buildings that appealed simultaneously to a variety of audiences (Foster 2008, following Metcalf 1986). Foster called this a 'wide-ranging, traveling architectural vision' (Foster 2008:160). Baker's associate, JM Solomon, stressed 'both the South Africanness and the modernity' of Baker's work (Solomon 1910), perhaps more strongly put than Baker's own words at the time (Baker 1909).

A special landscape feature of the architecture involved 'juxtaposing civilization and wildness', and certainly placing the Union Buildings below the ridge horizon of Meintjieskop 'left the slope immediately behind the building in its untouched native state' still 'preserved as a fragment of wildness' today; while the building 'imparted a sense of stability, autonomy, and orientation that stood against the unconfigured, unimproved third nature of the veld beyond' (Foster 2008:160).4

The slight hyperbole in such assessments seems common in critique of Baker's work, whatever members of this audience may make of it (and I do find it pretty remarkable without forgetting how many assistants were involved not to mention craftspeople and workers). The exaggeration is revealed by the incompleteness of the Union Buildings project, for Baker included structures above the actually existing edifice on the summit: Roger Fisher (2004:43-44) remarked that 'perhaps thankfully' the project remained incomplete.

Contextualising the architecture of the Union Buildings remains important but perhaps more elusive than conclusive (Kros 2015:156):

Baker and Rhodes were members of a network ... of upper-class English supporters of the particular vision of 'reconstruction' espoused by Lord Alfred Milner and the civil service officials he recruited ... As administrator of the two former Boer Republics, Milner was confronted with the ruination left in the wake of the war, and the still smouldering hostility between Boer and Briton. His programme of comprehensive reconstruction was intended to address both. It included the ideological promotion of a united white South African 'nation' that would retain close ties with Britain - summed up in the paradoxical concept of 'colonial nationalism' ... As Foster (2008) argues, the visual landscape came to be heavily imbued with the programme of 'colonial nationalism'. Foster (2008: 40) asserts: ... Baker's study tour abroad ... had fired [his] imagination about architecture's capacity for making an indelible impression of 'dignity and power' on citizen and visitor alike (Baker 1909:513) - According to Foster (2008), the legacy of colonial nationalism endured long after Milner's departure in 1905.

I return to the concept of 'colonial nationalism' towards the end of this piece. Next, however, let us consider some moments in the history of the Union Buildings over its 105 years.

Power of the Union Buildings

In a way the power of the Union Buildings is revealed through protest actions against various governments that have taken place there, often with marches to the site, on occasion from far away. The most well-known protest in Pretoria in earlier eras was probably that of 9 August 1956, when thousands of women marched on the Union Buildings to protest against the extension of passes to women - that is, of the notorious identity documents used to control movement during generations of segregation and apartheid (Kros 1980). The often ignored downside, however, of this much celebrated event, is that it did absolutely nothing to deflect the then government from its course (Mabin 2011:183). The same could be said of the two demonstrations by "Afrikaner women" a quarter of a century apart, in 1915 and 1940: the rebels of 1914 were not released, South Africa did not withdraw from the Second World War, and, indeed, passes were extended to women.5

In 1992, newspapers around the world reported that 'Mandela leads blacks in huge demonstration in Pretoria, South Africa'. 'Nelson Mandela led 100,000 cheering black marchers to the seat of white power, Wednesday, in one of the biggest demonstrations ever to demand an end to President FW de Klerk's government', the report went on to say. Yet, as Barbara Harmel noted at the time, '[a]n impressive display of mass opposition by the African National Congress, these protests alone posed no serious challenge to the De Klerk government'.6 Yet as electoral democracy developed, demonstrations at the Union Buildings arguably gained greater success than those in the apartheid epoch. One of the ultimately more successful took place on 23 October 2015, when thousands of students from around the country converged on the Union Buildings demanding at least no increases in their fees for the next year, and beyond that calling for 'Fees Must Fall'. Then President Zuma responded with a commission of enquiry, plus a commitment to no university fee increases for 2016. As his own position weakened for a wide variety of reasons, just over two years after the student demonstration Zuma announced free first year university education. Indeed, sources of his weakened position included a large march and rally on 12 April 2017 at the Union Buildings; his presidency came to an end well under a year after that.

So, in a way, perhaps the Union Buildings, built as the home of a white minority government in Africa, for some at least - a large number in some cases - can function as 'an anti-monument to white supremacy' since 'a memorial's articulation of the past is in part a function of its audience' (Dwyer & Alderman 2008:169).7 Or as Mitchell (2013:446) noted, in relation to the Cartier monument in Montreal, which has echoes of colonial and settler politics not completely distant from the period in which the Union Buildings came into being:

... there is a shifting choreography of ceremonies which take place there, and which inexorably rework the types of linkages and meanings of the memorial through time. As the spectacles change, the urban collective memory associated with the monument also changes, and the monument becomes something of a palimpsest, reflecting both "present pasts" (Huyssen, 2003) and past presents.

Change at the Union Buildings

Amongst other things, the uses of the Union Buildings have changed over many decades. Most obvious is the departure over time of many government departments originally housed there, and following the exit of what is now called DIRCO (Department of International Relations and Cooperation) a few years ago, leaving only the Presidency. I return to the dispersal of government bureaucracy around Tshwane below.

There will be historians who read this paper who will well remember working in the reading room of the old State Archives, housed in the Union Buildings until the end of the 1980s. The archive was part of the original design: as JM Solomon wrote in 1912, 'the archives department extends under the greater portion of the building. The 43 000 superficial feet of space [over 4 000 square metres] will be sufficient to store the records of Government for many generations to come, and will justify a thousandfold the cost of the excavations (Solomon 1912:7).

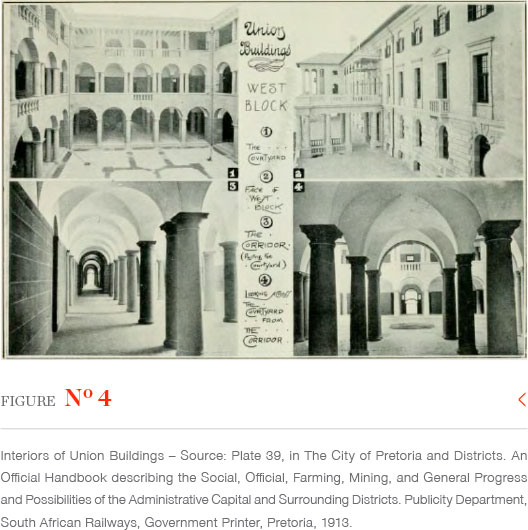

Most historians never saw the archive stacks down below, but certainly enjoyed the tinkling of the fountain in the West Courtyard below the open windows of the non-airconditioned reading room on typical hot Pretoria days. At that time, one entered the Union Buildings with the presentation of some form of identification to rather casual policing at the western-lower entrance; not so very long before that, right up to the 1990s, one could wander freely around the amphitheatre, through the colonnades, and into the interiors that have been hidden behind ever increasing security over the past generation.

Thus, the segregation of participants in perhaps the most celebrated event in the history of the Union Buildings, the 10 May 1994 inauguration of Nelson Mandela as the first president of a 'new South Africa', came as no surprise. Not only were 'VIPs' sealed off at the highest level, performers, musicians and choirs occupied a middle fenced area at the top of the gardens; whilst the 100000 or more in the crowd stood no chance of getting closer to the day's main event. The president and deputies 'took the oath of office "in the presence of all those assembled here" while standing in a small pavilion, open to the VIPs in the amphitheatre but sealed with plexiglass at the rear end facing the crowd below. The official enactment of the new state and its representative actors in this privileged space' (Kruger 1999:1) could best be seen anywhere else in the world on TV screens.

Nowadays, a visitor centre stands on the road below the amphitheatre, but as Gauteng province's official tourism agency puts it, 'Unfortunately, you cannot go inside the buildings themselves, but visitors are free to explore the terraced gardens that look out over the city' (Gauteng.net 2018). So for those of us who saw the interiors of the Union Buildings more or less unfettered in times gone by, not to mention an earlier generation to whom past prime ministers without any pretense at body guards doffed their hats whilst walking by, the "sealing off" of the Union Buildings might suggest a separation between citizen and power and a concealment that has strengthened over time. That impression can be undercut by the experience of some visitors finding themselves unexpectedly invited into the Buildings by staff, or slipping past the supposedly tight security oddly demanded by officials like Arts and Culture Director General and former political prisoner, Rob Adam, in 2000.8

One result of this enclosure is that the Police Memorial in the grounds is far more accessible to the public than the Women's Monument. That

memorial, unveiled on 9 August 2000 (Women's Day) ... implied that they were now equal with men in the new South Africa. But as happens so often in women's history, deeds not words render finality. The Union Buildings are no longer accessible to the public. They have become a restricted zone. The memorial, installed with high hopes, cannot project its homage to history or insert its presence into twenty-first century rhetoric about justice and equality. Anyone wishing to view the Women' s Memorial now has to make an appointment, well ahead of the expected visit, via the Office of the President (Arnold 2005:27).

What a visitor can see once ascended onto Government Avenue (the uppermost roadway, Fairview Avenue, is closed to the public) is a popular view of Pretoria, numerous curio sellers and other tourists, and the back of the statue of Nelson Mandela, placed high up in the Gardens and unveiled on 16 December 2013 just after the death of its subject. This is the major change that alters the character of the place, and distracts attention from the inaccessibility of the interiors. It hardly needs to be added that the Mandela statue is wildly popular as an element in photos, which surely just about every visitor will participate in making.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the closure of the Buildings, the mystique of this place of power persists - and does so in new ways. There is a new kind of incorporation of the Buildings into the life of the city; along with shifts in the ways that citizens see government, its symbols and its other trappings. I return to some of the ambiguous results of these changes further on in the paper; for now, I want to turn to the impression of the 'seat of government' within the landscape of the (executive) capital city.

Union Buildings and the city

I would hazard (supported by many, many comments on popular internet travel sites) that most people find the Union Buildings "impressive". This structure, however, is not a Roman or Washingtonian forum; 'Pretoria is of course peculiarly lacking in something similar to the Capitol in Washington, the national assembly in Abuja or the dramatic Niemeyer assemblage in Brasília' (Mabin 2015:34). Perhaps we could say that there is a limit to the impression of 'supernatural omnipresence' (Hook 2005) that a massive monument like the Union Buildings could be thought to project; a limit by comparison with Rome or Washington, or newer attempts such as Astana (Therborn 2017:355-6) to the ways in which the Union Buildings shift the 'bodily experience' of constructed spaces, merely a partial success in creating 'a vivid sensation of the conditions of intersubjectivity between monument and spectator' (Kros 2015: 153, citing Hook 2005:693, 697 and Henri Lefebvre's emphasis on bodily experience). Here we are concerned with one major building in a generally non-planned capital; in those major planned capital cities, along with Abuja, Dodoma, Brasília and others, debate and contest over symbolic and related features of such cities is substantial when not repressed (a major study being that of Therborn 2017).

Thus, despite the power of the Union Buildings as symbol (picked up in the official logo of the City of Tshwane not to mention the Presidency of the country) and the impressiveness of the edifice and site, apparently there has been a need felt by some to enhance the effect the Union Buildings create. That is usually related to a call for doing something significant with the landscapes of Pretoria.

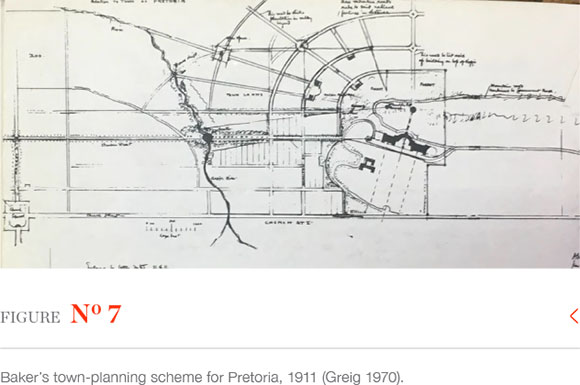

Many schemes have been proposed over more than a century to emphasise the "capitalness" of Pretoria, and each one involves ways of re-presenting the Union Buildings. Then City Manager, Blake Moseley Lefatola, complained in 2005 that 'coming in from south, east, west and north of the city, you have no idea that you are entering the administrative capital of the country', and went on to indicate that the city was thinking of creating landmarks to demarcate its status and shape to travellers (Mail & Guardian 2005:12). Recent schemes were far from the first to seek to change the image of the city. Perhaps the earliest was Herbert Baker's unimplemented 1911 scheme in relation to his design of the Union Buildings. He proposed to create a capital precinct, not in front of his masterwork (unlike, say, the Mall in Washington), but to its side:

I am bringing over to Pretoria a drawing ... showing a town planning scheme in relation to the Union Buildings ... there is a magnificent view westward, over the town lands, across the river and up [Struben Street] . if you can keep open a broad road . and carry this through the town lands, where it can be brought to the river and connected with [Struben] street beyond, we shall have a most magnificent effect some day in the future ... (cited in Fisher 2004:43, drawing on Doreen Greig).

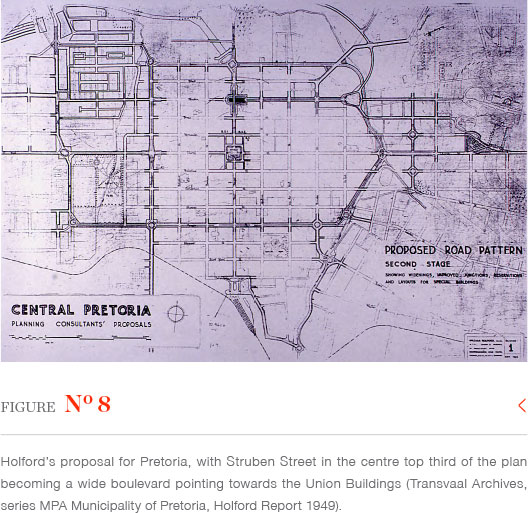

Decades later, something similar again emerged. In the period of "reconstruction" after World War II (Mabin 1988), Pretoria, like other South African and indeed global cities, sought a new plan. Into this context came (Lord) William Holford directly from his inner-London rebuilding activities, hired by the Pretoria City Council to produce proposals for the central area of the city (Mabin 1994). Innumerable meetings during the period discussed ways and means of improving the housing of government departments and the impact that reconstruction in this regard could have on the urban scene in the capital. 'Pretoria has a chance to develop into a new kind of capital city...', Holford remarked in August 1949 when presenting his draft report.9 The central feature of his plan for Pretoria's central area echoed Baker's of 1911: the idea of a government precinct along the sole central city street (Struben Street), which provided a view of the Union Buildings on the ridge to the east. The scheme entailed expropriation (of owners of various ethnicities, against their vociferous protests), widening towards a "boulevard", and a gradual concentration of new government buildings in that area. However, the City Council failed to persuade government that the plan should be implemented. Once the then Transvaal provincial administration undercut the scheme with huge new buildings near Church Square instead of along Struben Street, the idea of a government precinct for the capital faded away. In the democratic era, with a major repopulation of government and considerable social change in the city, inevitably the notion of achieving "capitalness" in new ways reappeared.

Why is Pretoria the capital, after all?10

In August 1997, President Mandela remarked that 'he believed South Africa should have one capital', not specifying which city that should be, but unleashing conflict within the governing party, the African National Congress (ANC) and elsewhere on whether to attempt to relocate the bulk of government administration to Cape Town, or move parliament to Pretoria (Pretoria set to take Parliament 1997). The constitution does not mention Pretoria, merely that 'The seat of Parliament is Cape Town, but an Act of Parliament ... may determine that the seat of Parliament is elsewhere' (in section 42 (6), which could explain continued efforts by the metropolitan council (named Tshwane since 2001) to 'rehistoricise the post-apartheid future' and run various media and event campaigns promoting the city as the capital and indeed, as a special and cosmopolitan place (Shepperson & Tomaselli 1997).

Debate seems to have continued in the ANC National Executive Committee and elsewhere for two decades, with committees sometimes being appointed to examine the 'capital issue', and the Department of Public Works, in collaboration with the City of Tshwane, developing a programme named 'Re Kgabisa Tshwane'.

The question of what to do with Pretoria dragged on for years. Cabinet kept the matter on its agenda, it seems, from October 1997 to February 2001. Meanwhile national government commissioned Freedom Park, designed and developed as perhaps the only major public space distinctly seeking to break with the past, within the capital city (Kros 2012). In 2001, Cabinet took the decision that national government headquarters would remain located in 'inner city Tshwane', in part 'to promote urban renewal', and although things moved slowly, within the next three years a new directive emerged. In June 2004, the president mandated the Departments of Public Works (the government's internal landlord) and the Department of Public Service and Administration to 'develop a framework to improve the physical work environment for the public service'. This programme was, in principle, approved by the cabinet in May 2005 (Department of Public Works 2005). In some respects, the programme was 'surrounded by the kinds of myths which seem typical of capital city development programmes. In Berlin, the notion of restoring a past glorious centre has framed rather more grandiose plans than the real scale and significance of what has actually been achieved by the city' (Cochrane & Jonas 1999). In Pretoria, a perhaps exaggerated notion of the continental and global importance of South Africa, symbolised by the mantra of 'our vast diplomatic community', serves similar purposes and sometimes drives a sense of the need for Pretoria to be something quite different from what it has yet become. Some ministries have been rehoused in major new buildings since the late 90s, but thus far there has not been a major plan or implementation which has accomplished a significant alteration to the physical nature of the city' (Mabin 2011:186).

In power in Tshwane, the ANC pursued dreams of what Clarke and Kuipers (2015) called 'recentreing Tshwane ... for a resilient capital' and unfolded various versions of plans to do so (Clarke & Lourens 2015). But perhaps because of the ANC's loss of power in Tshwane in August 2016, one struggles to find any reference to Re Kgabisa Tshwane subsequently.

In February 2016, then President Zuma startled many people by calling in his State of the Nation Address for parliament to be moved from Cape Town to Pretoria (or somewhere nearby) claiming this would save money in the longer term. A tender was launched and withdrawn, to conduct a feasibility study into moving Parliament from Cape Town to Pretoria. But in February 2018 a formal tender was indeed advertised (Parliament 2018), and a company called Pamoja secured appointment as announced in May 2018 (News24.com 2018). The report was due before the end of 2018 - but delay often occurs in such matters, plus the departure of the previous president and national elections in 2019 further placed the matter in abeyance. In mid-2019 the issue of moving parliament to Pretoria resurfaced, with claims that sites had already been identified, as well as acknowledgement that such a move would require constitutional amendment (Cape Talk 2019): the long running saga of the multiple capitals appeared likely to continue.

Meanwhile many government departments and agencies have created alternative architectures of government in Tshwane; and a string of others has chosen sites outside the central city and even deep into the suburbs. For example, foreign affairs moved from the Union Buildings to some distance north of the ridge where the Union Buildings stand; government communications are based in the eastern suburbs, and the defence department over 10 km out of the city centre. While the Department of Trade and Industry is closer to the central city, on a purpose-built 'campus' in the Sunnyside area, the new StatsSA (the government statistics agency) complex, erected between Pretoria Station and Freedom Park, paid some attention to the idea of reinforcing and expanding the core of the city. These locations frustrate the idea that a major government precinct, corridor, concentration or zone could develop in the central city with some links to the Union Buildings. Unlike two provincial governments' real or attempted engagements with old and new architecture in Northern Cape and Mpumalanga (see for example Noble 2011), and the Gauteng fantasy for central Johannesburg which has not yet proceeded, national government has not yet commissioned something new and dramatic. In consequence, the major symbol of government in Pretoria remains the Union Buildings, whilst the broader location of executive power and other government functions is increasingly dispersed.

'Ever since the union government was established in 1910 in Pretoria, in fact, this dispersion of government offices has prevented Pretoria from presenting a consolidated face of state power to citizens ... Such conditions and representations hardly facilitate the development of Pretoria as an uncontested and coherent capital city' (Mabin 2015:34-35). But they do not, in the end, challenge the Union Buildings as a site of power. Instead, a newer refrain has emerged, wishing for renaming, a form of recoding.

Renaming, retaining, rejecting?

In recent times, a particular focus of demands has been naming and renaming, reflected in controversy over naming Pretoria as Tshwane, the metropolitan area in which the Union Buildings may be found. Globally, regime change and renaming are very much interwoven (for some global contributions see Alderman 2006, Azaryahu 1996, and Yeoh 1996; for select South African commentary see Guyot & Seethal 2007, Ndletyana 2012 and Duminy 2014).

A particular ambiguity is discerned by many in the story of the Union Buildings - thus for example Mandela's inauguration revealed an 'ambiguous character of this astonishing climax to South Africa's transition to democracy' (Adler & Webster 1996:75). Apparently happy to retain the Buildings for their governmental use, yet concerned at their unmediated presence, some have called for renaming the place, at least since 2006. And, of course, like so many other name changes in South Africa and elsewhere, controversy followed.

Time for Union Buildings to be renamed: The ANC Youth League (ANCYL) president Fikile Mbalula suggested that "Progress cannot be expected until the Union Buildings is renamed after important people (who fought in the struggle). There is nothing important about the Union Buildings but it was named (as such) as a symbol of oppression of our people," Mbalula said, adding "everything named by the apartheid government must be replaced". Confirming the call ... ANCYL spokesperson Zizi Kodwa said there were many people the famous building could honour ... But ... DA MP Desiree van der Walt said the Union Buildings was not a symbol of apartheid but a symbol of South Africa, made even more so by the recent celebrations commemorating the 1956 Women's March to the buildings in protest against pass laws (Independent Online 2018).

The centenary celebration of the completion of the Union Buildings naturally created an opportunity for reviving the issue:

The EFF ... rejected the centenary celebration of the Union Buildings and called for the seat of government in Pretoria to be renamed. 'To celebrate the Union Buildings as 'union' is to celebrate history of black dispossession and exclusion,' spokesman Mbuyiseni Ndlozi said in a statement (Independent Online 2013).11

However, the only new naming was to call the amphitheatre the Nelson Mandela Amphitheatre, made official at that time.

As the Jacob Zuma presidency gathered increasing hostility, the Union Buildings provided once more a foil for criticism and for promoting the contrast between different ANC regimes:

ANC veteran and convener of the Save South Africa campaign Sipho Pityana has called for the Union Buildings to be renamed after the country's first democratic president, Nelson Mandela ... He said citizens shouldn't continue to live with symbols of an oppressive past overshadowing SA's diverse and inclusive future ... speaking in his capacity as the chairperson of the University of Cape Town council, he told guests who had gathered for a graduation ceremony that it was ironic that government had renamed only part of the colonial-era building after the global icon. Yet the name of the Union Building itself remains as it is in memory of the four provinces in 1910 that excluded blacks. It is upon you as the new generation of intellectuals to share these lessons with society, point out the irony and insist that the Union Buildings should be named Nelson Mandela House," he said. South Africans should not continue to live with symbols of an oppressive past overshadowing the diverse and inclusive future that they seek to build as a new society, he said. He added: "We need to do the same about the many other oppressive symbols in our society (The Citizen 2016a).

Two days later, The Citizen newspaper reported random remarks presumably from people a reporter accosted on the street, headlining 'Pityana's remarks provoked much talk around Pretoria'.

Jeminah Mhlongo from Pretoria said: "The name reminds us of the past. My understanding is if you don't know where you are coming from, you will not know where you are going to."

"I think the name should remain for the next coming generation to also know where we are coming from."

Mhlongo added that South Africans need to change their mindsets and understand that this was the place where serious matters were supposed to be discussed.

"Those who want to choose the Union Buildings and the name issue for the wrong reasons are not doing us justice."

Danie Oberholtzer said the Union Buildings got its name long before apartheid.

"The name comes just after the Boer War and that is where the 'Unie' comes from," he said.

"We will also have to look at all the cost just to change the name. We have to look at the bigger picture.

"[People] should, instead, focus on the disadvantaged and build houses because so many people are still living in shacks. [People] should leave the name changes and rather focus on building up the nation."

Masindi Ndidzulafhi said there was a lot of history behind the Union Buildings.

"For instance, the women marched to the Union Buildings in 1956. The name does not refer to any apartheid name.

"[People] must keep the name to preserve this part of the history for our children and grandchildren," he said.

"There are a lot of places, streets named after Nelson Mandela, so I honestly think that is enough. The Union Buildings should not be replaced with the name Nelson Mandela.

"We love him and we honour his legacy, but the Union Buildings cannot be named after Nelson Mandela."

Birnadette Lottering agreed with Ndidzulafhi and said enough places were named after Nelson Mandela (The Citizen 2016).

Just as Ramabina Mahapa, President of University of Cape Town's (UCT) Students' Representative Council (SRC), stated that the Rhodes Must Fall campaign was not directed against a particular historical individual, but rather the 'symbols' of 'institutional colonialism' that persist at the university well beyond the advent of democracy (Kros 2015:151), there may be in circulation unrecorded and even unspoken desires to take the potent combination of power and architecture away from the 'colonial nationalism' of the Union Buildings. Thus, author Mandla Langa wrote 21 years after the inauguration of Nelson Mandela as President at the Union Buildings:

It is my belief that while the practicalities of today's (the past's?) negotiated settlement dictated for appropriation of the savage splendour of the edifices of apartheid's conquistadors, for instance, the Union Buildings and Parliament, the weight of the memory of the provenance of such structures will, one day, undermine the project of democracy. One believes that these buildings should have been converted into museums, where the unexorcised spirits of the past could be contained, rather than being unleashed to poison our inexorable march into the future (Langa 2015:22).

Such a view raises the question of whether continued use of architecture such as the Union Buildings 'undermines the democratic project', and related questions concerning alternatives to such extension - the kinds of alternatives, perhaps, which have driven creations of new capitals and their architecture in Brazil and Nigeria, in Tanzania and Kazakhstan; and global debate over reuse of buildings with problematic pasts, such as those in Berlin.

Foster (2008:28) pointed to the 'unresolved character of the new nation' of the Union of South Africa at the time of creation of the Union Buildings. I have previously suggested that something akin to that lack of resolution can be identified in the country now:

in a context of lack of clarity about the nation, multiple capitals and diffuse political power, Pretoria is definitely not a 'total capital', 'dominant culturally and economically as well as politically', which one would have 'expected (other things being equal) to favour socially and culturally cohesive political elites, and through them more consistent public policies' (Therborn 2002: 516). It is not yet, at least, a place 'where governments are installed, and where governments lose their power'; and it is far from being the sole 'center of political debate about the orientation of the country...[a place] where national differences are made' (Therborn 2002: 513).... Pretoria today remains a place where the 'political iconography of the city' (Sonne 2003) is perhaps more in flux, less clearly developed, than in many other capitals. Although there is a growing attempt to place a new impress on this city - and the other South African capitals - the underlying diffuse nature of power in the country, and the lack of cohesion around the idea of the nation, let alone its capital, are likely to preserve the perhaps disordered, and indeed perhaps more human, character which Pretoria seems to have settled into in the early decades of democracy. Of course, there is a chance that this picture will change radically (Mabin 2011:187).

The City Council's consultants picked up the same type of theme in producing Tshwane Vision 2055, in 2013:

there are historical reasons the City of Tshwane did not completely take on the monumental qualities found in most other capital cities. The compromise reached when establishing the Union of South Africa in 1910 led to the creation of three capitals ... Even today, Government departments are not in one government complex that is inaccessible to the public. They sit side by side with shops in the City's downtown placing the national decision makers on par with the citizenry to the extent that they are visible and accessible (Tshwane 2013:84).

In this city and national context, perhaps the Union Buildings survive and do more than that, precisely because Baker's conception was not isolated: as Foster (2008, citing Metcalf) argued that Baker's vision was 'much wider', amongst other elements thinking that 'British metropolitan architecture had fallen lamentably short of its potential'. So the Union Buildings continue, changed in minor ways, but very much altered in the ways in which publics and individuals perceive them:

Typically, memorial landscapes are meant to broadcast an unequivocal lesson to all who behold them ... these plans are undone if a memorial means nothing to a passing viewer. Might it be the case that the [monument's] historical significance is lost on most passers-by, their appetite for history dulled by a youthful diet of disconnected historical dates and a parade of (in)famous characters? Those bold enough to propose a memorial must confront the inevitable: once in place, memorials can be ignored (Dwyer & Alderman 2008:176).

Let us pick up that thought. As people pass along Stanza Bopape Street (former Church Street east), very many of them in collective taxis, some may well ignore the view of the Union Buildings above the expansive lawns; others will notice them, each day; what do these passing viewers make of the edifice? My contention is that what is seen has transformed and is changing, given the events and characters that have passed across this stage in the lifetimes of most passers-by; so that the 'locus of collective memory' has been 'radically de-center[ed] from designer to viewer' by the passage of time and the turns of events (paraphrasing Dwyer & Alderman 2008:176 and their footnote 2). Pure architectural history of the Union Buildings and the intentions of Baker and his acolytes cannot account for how the place has been re-inscribed into the collective and individual consciousness of passers-by. In this form, I am perhaps echoing the long established ideas of Halbwachs (1952) on memory as social.

As I noted earlier in this piece, I want to return to 'colonial nationalism'. For me, static descriptions such as 'Sir Herbert Baker's monument to British Empire and white supremacy' (Kruger 1999:1) turn out to be unhelpful in understanding the fluidity of the 'monument', many diverse perceptions of it, not to mention its continued housing of the peak of state power in what we might once have called "majority-ruled" South Africa. My proposition is that the Union Buildings continue to represent a type of "colonial nationalism", the meaning of which is continuously contested in contemporary South Africa. Nationalisms in South Africa, indeed in Africa, seem to me trapped in an endless response to colonialism, understandings of which are varied and shifting, but colonial nonetheless, eluding the decoloniality that so many demand. There are elements of nostalgia even in memories of life in the high apartheid era (Dlamini 2009). And the Union Buildings appear able to continue to make a dramatic statement of something set in the world (so easily welcoming all those heads of state and deputies whom I watched on 10 May 1994, from Fidel Castro to Al Gore); so appropriate, apparently, to the present era (so quietly but commandingly present on the presidential banners); somehow seen as - yes - South African, not foreign ... and, perhaps, rather than a simple cleansing from an oppressive past, continually changing just as the city and the society that surrounds them do so too. The politics of the Union Buildings do not end here. This object has proved not to be reluctant to change, and whilst it may yet fall figuratively, functionally or literally, it shows no signs of doing so just yet, for

[d]espite the impression that memorial landscapes are somehow frozen in time, they are perhaps better seen as open-ended, conditionally malleable symbolic systems, ones that are fashioned here-and-now in order to influence a near-at-hand tomorrow (Dwyer & Alderman 2008:168).

For the present, the Union Buildings appear to preside over Pretoria and to house the President of the country, as though there had been no rupture between the past and the future. The image, social memory and consciousness of the Buildings has been remade by many actors though the events and epochs described in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This article began as a paper for the Wits History Workshop/School of Architecture and Planning colloquium 'Falling Monuments, Reluctant Ruins' held in November 2018. Thanks to the organisers and funders, and participants there, as well as to referees and editors of Image & Text. I bear responsibility for the article, and report no conflict of interest.

Notes

1 . On aspects of complex transition in the police forces, see inter alia Cawthra (1993).

2 . Apart from a grammatical failure, it's incorrect to claim that Meintjieskop is the highest point in the city; and the Union Buildings are not on the summit but rather on a more level piece of ground below the ridge. Casual errors creep into many accounts of the Union Buildings and their place in South Africa today - for example Bremner's (2007:95) notion that a 'jumbo jet flypast' took place when Mandela was inaugurated - those who were there saw air force jets trailing the 6 colours of the new flag, not the jumbo jet of the 1995 Rugby World Cup final, and the symbolism of the military saluting the new president was hardly lost on the crowd.

3 . Leach's (2002a) account is in a chapter which follows his application of the idea of 'denazification' to Berlin and Bucharest where the notion is perhaps more appropriate. According to one reviewer his approach lacks depth and conceptual sophistication (Bremner 2003).

4 . The site is a portion of a farm oddly enough named 'Blackmoor' - cadastral reference 347 JR.

5 . In addition to the well-known women's march of 1955, at least two other notable demonstrations by women took place at the Union Buildings: in 1915 calling for release of imprisoned leaders of a 1914 rebellion led by defeated South African War generals; and in 1940 calling for South Africa to withdraw from fighting Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.

6 . Among many other media around the world, San Antonio Express, news, 6 August 1992; Barbara Harmel, Let people power finish the job in South Africa, International Herald Tribune, 5 September 1992. Accessed 1 August 2008, http://www.iht.com/articles/1992/09/05/edba.php?page=1

7 . These authors make the point in relation to the 'Liberty Monument' to the White League in New Orleans, arguing that such turnarounds are not uncommon.

8 . Sholain Govender, A shrine honouring women hidden from sight, https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/a-shrine-honouring-women-hidden-from-sight-250413[09.08.2005]cons 11.11.2018.

9 . Sources for this material are in Transvaal Archives, Pretoria (TA), Pretoria Town Clerk series (MPA), cited in Mabin (1994).

10 . Siting the Constitutional Court in Johannesburg - the 'fourth national capital' as a result (Mabin 2011) - seems to have occupied more attention than the question of changing the other three capitals during the negotiation period in the early nineties, but this is a matter for further investigation.

11 . For a silly riposte from 'Banananews' see https://banananewsline.wordpress.com/2013/12/18/renaming-the-union-buildings-will-bring-economic-prosperity/

REFERENCES

Adler, G & Webster, E. 1995. Challenging transition theory: the labor movement, radical reform and transition to democracy in South Africa. Politics & Society 23(1):75-106. [ Links ]

Alderman, D. 2006. Naming streets after Martin Luther King, Jr.: No easy road, in Landscape and Race in the United States, edited by R Schein. New York: Routledge:213-236. [ Links ]

Arnold, M. 2005. Visual culture in context: The Implications of union and liberation, in Between union and liberation: Women artists in South Africa 1910-1994, edited by M Arnold and B Schmahmann. Aldershot: Ashgate:1-33. [ Links ]

Azaryahu, M. 1996. The power of commemorative street names. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14(3):311-330. [ Links ]

Baker, H. 1909. The architectural needs of South Africa. State of South Africa. May:512-524. [ Links ]

Becker, R. 2000. The new monument to the women of South Africa. African Arts (Los Angeles) 33(4):1-4. [ Links ]

Botha, PR. 2013. Captive the life of our static buildings, MArch Prof research report, University of Pretoria, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Bremner, L. 2003. Book review: Neil Leach, The hieroglyphics of space: reading and experiencing the modern metropolis. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27(2):471-482. [ Links ]

Bremner, L. 2007. Memory, nation building and the post-apartheid city: The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, in Desire lines: Space, memory and identity in the post-apartheid, edited by N Murray, N Shepherd, M Hall. London: Routledge:85-104. [ Links ]

Bunn, D. 1998. Whited sepulchres: on the reluctance of monuments, in _Blank: Architecture, Apartheid and After, edited by H Judin and I Vladislovic. Cape Town: David Philip & Rotterdam: NAI:92-117. [ Links ]

Cape Talk. 2019. Parliament still developing a plan to move to Tshwane. [O]. Available: http://www.capetalk.co.za/articles/346303/parliament-still-developing-a-plan-to-move-to-tshwane. Accessed 07 July 2019. [ Links ]

Cawthra, G. 1993. Policing South Africa: The South African police and the transition from apartheid. London: Zed Books. [ Links ]

Clarke, N. & Lourens, F. 2015. Urban planning in Tshwane: Addressing the legacy of the past, in Re-centring Tshwane: Urban heritage Strategies for a Resilient Capital, edited by N Clarke & M Kuipers. Pretoria: Visual Books:39-51. [ Links ]

Clarke, N. & Kuipers, M. Re-centring Tshwane: Urban heritage strategies for a resilient capital. Pretoria: Visual Books. [ Links ]

Department of Public Works 2007 Pretoria: Union Buildings: Conservation management plan: Statement of significance, Union Buildings Architectural Consortium. Pretoria: Reimmer and Schütte Architects and others. [ Links ]

Dlamini, J. 2009. Native nostalgia. Johannesburg: Jacana. [ Links ]

Duminy, J. 2014. Street Renaming, Symbolic Capital, and Resistance in Durban, South Africa. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32(2):310-328. [ Links ]

Dwyer, OJ & Alderman DH. 2008. Memorial landscapes: analytic questions and metaphors. GeoJournal 73:165-178. [ Links ]

Fisher, R. 2004 The Union Buildings: reflections on Herbert Baker's design intentions and unrealised designs. South African Journal of Art History 19:38-47. [ Links ]

Foster, J. 2008. Washed with sun: Landscape and the making of white South Africa. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [ Links ]

Frykenberg, R. (ed.) 1986. New Delhi through the ages: essays in urban history, culture and society. New Delhi: Oxford University Press: [ Links ]

Gauteng.net 2018. Attractions. [O]. Available: https://www.gauteng.net/attractions/union_buildings/. Accessed 30 September 2018 and 11 November 2018. [ Links ]

Greig, D. 1970. Herbert Baker in South Africa. Cape Town: Purnell. [ Links ]

Guyot, S & Seethal, C. 2007. Identity of place, places of identities, change of place names in post-apartheid South Africa. South African Geographical Journal 89(1):55-63. [ Links ]

Halbwachs, M. 1952. Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire; trans L. Coser as On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1992. [ Links ]

Hook, D. 2005. Monumental spaces and the uncanny. Geoforum 36(6):688-704. [ Links ]

Independent Online 2013.16 December. [O]. Available: https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/rename-union-buildings-eff-1623130. Accessed 01 November 2018. [ Links ]

Independent Online 2018. [O]. Available: https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/time-for-union-buildings-to-be-renamed-300795 30 October 2006. Accessed 01 November 2018. [ Links ]

Judin, H. & Vladislovic, I (eds). 1998. _Blank: Architecture, Apartheid and After. Cape Town: David Philip & Rotterdam: NAI. [ Links ]

Keath, M. 1992. Herbert Baker: architecture and idealism, 1892-1913: the South African years. Johannesburg: Ashanti. [ Links ]

Kros, C. 1980. Urban African women's organisations 1935-1956. Africa Perspectives (dissertation No. 3). University of the Witwatersrand, September (reprinted December 1982). [ Links ]

Kros, C. 2012. A new monumentalism? From public art to Freedom Park. Image and Text 19:34-51. [ Links ]

Kros, C. 2015. Rhodes Must Fall: archives and counter-archives. Critical Arts, 29 sup1:150-165. [ Links ]

Kruger, L. 1999. The Drama of South Africa: Plays, pageants and publics since 1910. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Langa, M. 2015. Pillars of Society: Our most enduring monuments are our democracy and our diversity. Business Day WANTED May, 125: 22-26. [ Links ]

Leach, N. 2002a. Erasing the traces: the 'denazification' of post-revolutionary Berlin and Bucharest, in The hieroglyphics of space: Reading and experiencing the modern metropolis, edited by N. Leach. London: Routledge: 80-91. [ Links ]

Leach, N. 2002b. Erasing the traces: the 'denazification' of post-apartheid Johannesburg and Pretoria, in The hieroglyphics of space: Reading and experiencing the modern metropolis, edited by N Leach. London: Routledge:92-100. [ Links ]

Leach, N. (ed) 2002c. The hieroglyphics of space: Reading and experiencing the modern metropolis. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 1994. The influence of London planning on two phases of reconstruction in South Africa: 1940s and 1990s. Paper presented at International Planning History Society conference: Seizing the Moment, London Planning 1944-1994, 7-9 April. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 1998. Reconstruction and the making of urban planning in 20th-century South Africa, in _Blank: architecture, apartheid and after, edited by H Judin & I Vladislavic. Cape Town: David Philip, Rotterdam: NAi: 268-277. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 2011. South African capital cities, in Capital cities in Africa: Power and powerlessness, edited by G Therborn and S Bekker. Dakar: Codesria and Pretoria: HSRC Press:168-191. [ Links ]

Mabin, A. 2015. Tshwane and spaces of power in South Africa. International Journal of Urban Sciences 18(1):29-39. [ Links ]

Mail & Guardian 2005. 10 November: 12. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. 1974. The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Metcalfe, T. 1986. Herbert Baker and New Delhi, in New Delhi through the ages: Essays in urban history, culture and society, edited by R Frykenberg. New Delhi: Oxford University Press:391-400. [ Links ]

Mitchell, K. 2003. Monuments, memorials, and the politics of memory. Urban Geography 24 (5):442-459. [ Links ]

Ndletyana, M. 2012. Changing place names in post-apartheid South Africa: accounting for the unevenness. Social Dynamics: A Journal of African studies 38(1):87-103. [ Links ]

News24.com 2018. [O] Available: https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/parliament-sets-up-feasibility-study-to-look-into-move-to-pretoria-20180523. Accessed 01 November 2018. [ Links ]

Noble, J. 2011. African identity in post-apartheid public architecture: white skin, black masks. Aldershot: Ashgate. [ Links ]

Parliament of the Republic of South Africa 2018 Invitation to bid: B2/2018: Comprehensive feasibility study for possible relocation of Parliament to Pretoria relating to socio-economict impact & cost effectiveness of the project (3 February). [ Links ]

Radford, D. 1985. Baker, Lutyens, and the Union Buildings. South African Journal of Cultural History 2(1):62-69. [ Links ]

SA History Online 2018 Union Buildings [O]. Available: https://www.sahistory.org.za/place/union-buildings. Accessed 30 September 2018. [ Links ]

Shepperson, A & Tomaselli, K. 1997. 'Pretoria, here we come': re-historicising the postapartheid future. Communicatio 23(2):24-33. [ Links ]

Solomons, JM. 1910. The Union Buildings and their architect. The State of South Africa, 4 (1) July: 3-18. [ Links ]

Sonne, W. 2003. The political iconography of the city, in Representing the state: Capital city planning in the early twentieth century, edited by W Sonne. Munich: Prestel. [ Links ]

Sonne, W (ed.) 2003. Representing the state: Capital city planning in the early twentieth century. Munich: Prestel. [ Links ]

South African Police Officers Memorial [O]. Available: http://www.southafricanpoliceofficersmemorial.com/national-police-memorial.html. Accessed 04 July 2019. [ Links ]

The Citizen 2016a. [O]. 21 December. Available: https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/1380727/sipho-pityana-wants-the-union-buildings-to-be-named-after-mandela/. Accessed 01 November 2018. [ Links ]

The Citizen 2016b. 23 December. [O]. Available: https://citizen.co.za/news/south-africa/1382127/dont-name-union-buildings-after-madiba-urge-residents/ Accessed 20 September 2018. [ Links ]

The Presidency 2018: [sp]. Union Buildings [O]. Available: http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/content/union-buildings. Accessed 30 September 2018. [ Links ]

Therborn, G. 2002. Monumental Europe: The national years. On the iconography of European capital cities housing. Theory and Society 19(1):26-47. [ Links ]

Therborn, G & Bekker, S. 2011. Capital cities in Africa: Power and powerlessness. Dakar: Codesria & Pretoria: HSRC Press. [ Links ]

Therborn, G. 2017. Cities of power: the urban, the national, the popular, the global. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Tshwane, City of. 2013. Tshwane Vision 2055: Remaking the Capital City (City of Tshwane). [ Links ]

WIReDSpace [sa] [O]. Wits Institutional Repository on DSpace. Available: http://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/10881. Accessed 04 July 2019. [ Links ]

Yeoh, BSA. 1996. Street-naming and nation-building: toponymic inscriptions of nationhood in Singapore. Area 28:298-307. [ Links ]