Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.33 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a12

ARTICLES

Repetitions repeatedly repeated: mimetic desire, ressentiment, and mimetic crisis in Julian Rosefeld's Manifesto (2015)

Duncan Reyburn

Department of Visual Arts, School of the Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa duncan.reyburn@up.ac.za | https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6753-3368

ABSTRACT

This paper offers an exploration of Julian Rosefeld's film Manifesto (2015), which is a fascinating amalgamation and interpretation of modernist, avant gardist manifestos. The paper employs the film itself as a hermeneutical framework, especially is use of the rhetorical-hermeneutical device of repetition, and also makes use of René Girard's mimetic theory. Through this double-hermeneutic, two aims are set out: the first being to offer a way to rethink the meaning of the art manifesto as that modernist genre par excellence and the second being a way to rethink trends in artistic and creative production in general.

Keywords: art manifestos; René Girard; hermeneutic mimetic theory; creative innovation; ressentiment.

"... you write a manifesto when you're young and insecure." - Julian Rosefeld (2016).

Introduction

German artist and filmmaker Julian Rosefeld's Manifesto (2016) is a powerful and entertaining tribute to the innovations of the artistic avant-garde - or rather to the avant-gardist obsession with innovation. Given the film's stress on innovation, it is perhaps unexpected that it makes extensive use of the rhetorical device of repetition, since it is a device that would seem to resist novelty. Repetition, after all, has been regarded as a rhetorical device since the days of Plato and Aristotle as a confirmation and affirmation of what has already been communicated. Even when the repetition or mimesis involves the obscuring of an original eidos, as in Plato,1 it has always been used to signal constants and consistencies rather than irregularities. Arguably, Rosefeld's choice of repetition is not only rhetorical (persuasive), but also hermeneutical (interpretive). Thus, the nature of this repetition is somewhat more complicated than it may initially appear. It does not merely imply something like monotony or mere uniformity, but in fact suggests something more along the lines of harmony, which includes difference within its structural unity.

Repetition was first highlighted as an aspect of the interpretive process by Martin Heidegger. In hermeneutics, to repeat is not to merely create a 'static reproduction of a meaning fixed once and for all', but instead suggests 'the revival of a meaning subject to continual review and revision' (Kiesel 1972:196). Thus, the repetition of the same is not against novelty but the primary source of and context for novelty. The pursuit of the new and the unfamiliar is highlighted by what would appear to be the opposite or even the negation of the new. This paradox provides the primary interpretive key for the film. It is a paradox to be expected, since all theories of the new pay homage to the presence and recapitulation of the familiar. Novelty arises not in the absence of the same, but in the reframing and 'rearranging of existing elements' (North 2013:31).

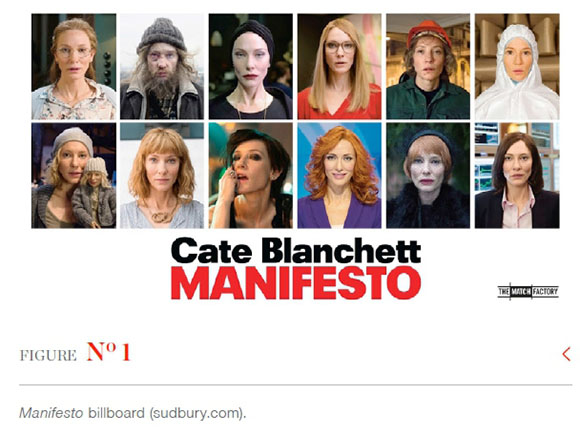

Two fundamental repetitions contextualise all other repetitions in Rosefeld's film. First, the screenplay comprises a restatement of selections from existing art manifestos from the past century or so. It is, therefore, again paradoxically, an original screenplay constructed almost entirely from quotations. The film itself, as Rosefeld (2016) suggests, is also heavily reliant on homages to previous films. Thus, if it is fresh, and there is certainly reason to view the film as both fresh and refreshing, it is precisely because it is a movie made up of recycled recipes - reframed and thus renewed.2 Then, second is the visual-dramatic repetition of Cate Blanchett, who, as the primary presence and sole performer of the art manifesto selections, plays a number of quite different characters in the film: a school teacher, a CEO, a factory worker, a Russian Ballet choreographer, a homemaker, a broker, an intoxicated punk, a newsreader and news reporter in conversation, a scientist, a puppeteer (with a look-alike puppet), a widow, and a homeless man (Figure 1). As the film credits reveal, the very filming of Manifesto required several doubles for Blanchett; thus, there is also the idea that Blanchett's doubling of herself - especially as noted in the puppeteer's double of herself and the news-reader's interviewing of her double - is repeated in the form of other unnoticeable, "invisible" doubles.

Mirroring the manifestos it quotes from, Rosefeld's film is analogous to a 'theme and variations' musical composition. In this, however, emphasis remains on the theme of the manifesto itself rather than on its variations, which is to say that form takes precedence over content. And yet, again, what, precisely, is the meaning of repetition in this film - and why should it matter? In this paper, it is my concern to examine this question within the context of mimetic theory. Apart from exploring how Rosefeld undercuts the rather shaky avant-gardist conception of novelty, which naively presumes that repetition undermines novelty, the purpose of this paper is to offer something along the lines of Rosefeld's reframing exercise. I offer: first, a way to rethink the meaning of the (art) manifesto as that 'modernist form' or genre 'par excellence' (Winkiel 2008:2);3 and, second, a way to consider trends in artistic and creative production in general. The first aim is more modest and therefore, arguably, more realisable in a paper of this scope and length. However, the second aim, while articulated here only in fragile, provisional terms, is more vital since it can help to clarify some of the meaning of the quintessentially modernist (avant-gardist and post-avant-gardist) obsession with dialectical oppositions in pursuit of novelty (Groys 2008:1). In so doing, I ask questions about artistic identity and provide something of a challenge to notions of artistic autonomy.

First repetition: mimetic desire

Manifesto commences with a screenshot of a definition of the word manifesto, which is said to be 'a public declaration of policy and aims by a party, group or individual' (Rosefeld 2015). This definition is followed by a blurred-out shot of the burning fuse of a firework (Figure 2) over which we hear Blanchett's voice declare, 'All that is solid melts into air' (Rosefeld 2015). This line, as confirmation of rhetorical-hermeneutical repetition, is a duplication in at least a few senses. It is, firstly, a quote from Karl Marx and Frederick Engels's The Communist Manifesto (1848). But since the line is followed by a quotation from Tristan Tzara's Dada Manifesto (1918), it is obvious that it is also a duplication of Tzara's repetition of Marx and Engels's words in his own manifesto. This has been quoted by Rosefeld in his screenplay, and finally by Blanchet in her performance. It is therefore, as the viewer encounters it, a quotation of a quotation of a quotation. Vitally, this redoubling does not conform to mere univocal or identical repetition. Rather, by drawing attention to repetition via minor contextual alterations, a kind of difference within repetition is allowed for, or perhaps something like an equivocal surplus arising from univocal determination.4

Tzara's manifesto goes on, 'To put out a manifesto, you must want ABC to fulminate against 1, 2, 3. To fly into a rage, and sharpen your wings to conquer and disseminate little ABCs and big ABCs, to sign, to shout, to swear ... ' (Tzara 2011:137). The image of the burning fuse of the firework and the consequent image of the firework being lit and released (Figure 3) suggests one meaning of this reference to repetitions of form: repetition can be a means by which we overcome the sheer transience of art, and also the brevity life itself. It may be a means, to employ a Nietzschean idea, of positing being over and against the scenography of entropic becoming (Bittner 2003:xxv). And yet, transience remains - as is captured in Manifesto's (2015) quotation of Phillipe Soupault's subversive but playful reflection on what it means to write a manifesto, 'I'm writing a manifesto because I have nothing to say'. Here, Soupault notes one irony of the manifesto form, namely that its self-assertion predicts and even insists upon its own erasure.5 This is an irony also captured by Tzara (2011:137) when he suggests that even to have an 'ABC' is to assume a norm, and to assume a norm is 'deplorable'. To establish a new norm (that which ought to be repeated) is to set up the very conditions according to which the norm will be undermined. To assert youth, for instance, is to '[chase] after Death' (Marinetti 2011:3).

The juxtaposition at the outset of such radically different manifestos in Rosefeld's film is fascinating in itself, since it may be taken as a kind of archetype of the modernist frame. On the surface, it would seem to capture the sheer pluralism of the avant-garde. But since the focus is on the form of the manifesto, it is more likely a reflection of something like Boris Groys's (2008:2) contention that, 'The field of modern art is not a pluralistic field but a field strictly structured according to the logic of contradiction. It is a field where every thesis is supposed to be confronted with its antithesis'. As intimated above, it involves self-contradiction, which implies the inevitable undoing of what one has done and is doing. Groys's idea here presents an incomplete dialectic; that is, a dialectic without the promise of a synthesis and which resists acknowledging the affirmative place of a thesis. Antithesis is the rule, which is ultimately to say that modern art is less univocal or dialectical than it is equivocal.6 In other words, modern art's trend towards self-mediation (the mediation of the other into the same intimated by dialectic) is precisely what gives rise to equivocation (the proliferation of unmediatable difference implied by the notion of the equivocal). Groys's idea is no doubt intuitively plausible even though it is also challenged by Manifesto's many repetitions, since repetition suggests that underlying this contradictory structure is something perhaps even more constant than such a perpetual oscillation between opposites would indicate. This constant, as I discuss shortly, is mimetic desire.

As a counterpoint to the various restatements of prior verbal and visual signs, Tzara himself declares resistance to repetition and therefore stresses the equivocal posture that he regards as essential in artistic creation, 'I oblige no one to follow me', he writes, 'And everyone practices his art in his own way, if he knows the joy that rises like arrows to the astral layers, or that other joy that goes down into the minds of corpse flowers and fertile spasms' (in Rosefeld 2015; Tzara 2011:137). Tzara (2011:138) continues to insist in surprisingly unironic fashion - as do many avant garde manifesto writers -upon the radical autonomy of both the artwork and the artist, 'Does anyone think he has found a psychic base common to mankind? How can one expect to put order into the chaos that constitutes that infinite and shapeless variation ... man?' Tzara (2011:138) offers that Dada's only 'common base' is a nominalist 'distrust for unity', which establishes a (self-contradictory) universal rejection of the possibility of any kind of universal. And yet, Rosefeld's film suggests, against this enactment of the equivocal, that the universal is not so easily done away with, since it is found in our endless desire for and reliance upon repetitions.

Tzara's notion of a "common base" happens to be echoed in the music that plays during and after Manifesto's opening monologue. It is piano music built upon the repetition of a single note, while chords vary around it - sometimes with harmonious resonances and sometimes with atonal dissonances. In this, and because it constantly calls into question the equivocities of the manifesto form by insisting upon the presence of the identical and the familiar, the filmic text seems again to raise the question: what is repeated, and what is the nature and meaning of this repetition? To answer this question, it helps to reflect more directly on Blanchett's presence in the film: her presence operates as a common base in this visual text - and as an actress, she repeats the lives of others that she is not. She reflects identities other than her own through her own identity: contra Tzara, difference thus occurs within the frame of identity rather than in the absence of identity. Identity equates to a unity that is established via the mediation of otherness, for things have to become what they are not in order to be themselves (Pickstock 2013:7).

This reflects something of what we find in the mimetic theory of René Girard. In Girard's work, the answer to the question of what the 'psychic base common to mankind' is, and therefore the thing repeated via otherness, is mimetic desire. Desire, for Girard, is not something that springs up automatically within a strictly bounded and autonomous individual, and is thus not born in the resonance of arbitrary equivocal being, but is something that emerges from 'interdividual rapport' (Girard 1991:49, 67, 146, 340; Oughourlian 2010:39). This is to say that desire is copied and, consequently, that the self's very sense of authenticity and autonomy is entirely dependent on the absorption of - that is, the repetition of - the desires of others.

In what it is widely recognised as the founding art manifesto, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism (1909), which is also quoted in Rosefeld's film, we find a vehemently antagonistic attitude towards an older artistic order. Museums are referred to as 'abattoirs for painters and sculptors', and '[a]dmiring an old painting' is likened to 'pouring our purest feelings into a funerary urn' (Marinetti 2011:6). Academies become 'cemeteries of wasted effort, calvaries of crucified dreams, records of impulses cut short!' (Marinetti 2011:6). In a later manifesto, echoing these bitter sentiments, Marinetti (2011:25) refers to tradition as a 'sewer'. For Marinetti (2011:7), given his persistent denigration of the past, what is required by the artist is an absolute break with what has gone before, such that art 'can be nothing but violence, cruelty and injustice'. Such things, deplorable though many would find them, function for the Futurist as a purgation of the notion of art. War is celebrated, because it cleanses; violence is called for because it offers the hope of renewal.

Towards the end of this same manifesto is a striking admission of hypocrisy, 'Our sharp duplicitous intelligence tells us that we are the sum total and extension of our forebears. Well, maybe! ... But what does it matter? We want nothing to do with it!' (Marinetti 2011:8). What is desired, whether realistic or not, is the nullification of any reference to commonality. Thus, Marinetti (2011:8) declares, 'Woe betide anybody whom we catch repeating these infamous words of ours!' This admission is striking because it submits that Futurism's very rejection of tradition is parasitic upon tradition, although there is still a strange homage to or foretelling of its own tradition to be found in the fact that Futurist manifestos are always dated '11' - a repetition owed, apparently, to one of Marinetti's superstitions (Danchev 2011:9). Nevertheless, the insistence against repetition remains: Futurism should not be copied (see also Apollinaire in Rosefeld 2015; Apollinaire 2011:26-28). And, indeed, art itself should be built upon a rivalry with what has gone before.

Here, then, is one of the clearest indications of the paradox of novelty, and a further indication that Girard's thesis applies rather well to the avant-garde impulse articulated in art manifestos. However, further clarification is required if this is to be rendered properly plausible, since the continuity with tradition both affirmed and disavowed in Marinetti's first manifesto can still appear to be the manifestation of a desire that contradicts an original desire rather than confirming it. In other words, it would seem that the desire of the artist here is not quite mimetic in the Girardian sense, but quite the opposite: a refusal to imitate the desire of the other. Is the desire for the new here therefore not in opposition to a desire for the traditional? In other words, is this not, as many proponents of the avant-garde seem to assume, a confirmation of the presence of some mythical equivocity intrinsic to artistic innovation?

This question finds an interesting answer in a visual repetition in our filmic text: Blanchett's one character - a New York stockbroker is presented as one among many people buying and selling stocks (Figure 4). Marinetti's (2011:25) Against traditionalist Venice (1910) manifesto is heard as a voice-over, announcing the reign of the 'Divine Electric light'. It is by way of this seemingly ironic juxtaposition of the artistic with the economic that the film announces something like a 'tradition of the new'. What was stated as a belief that nothing should be repeated is undermined here through endless repetition (Figure 5) - and, of course, the verbal repetition of Marinetti's manifesto, too, which goes against his stated desire to not have his manifesto's ideas repeated. As we would expect, a great deal of change happens within this stock market imagery of repetition, as is indicated by the constant updating of the market boards, which causes a repetitive cacophony of clicks. Nevertheless, such change is rendered insignificant within a world reduced to impersonality through repetition. Here, as if by dialectical mediation, the equivocal is temporarily overcome by a restatement of unbridled univocity.

We may ask: is the stock market not the most obvious example of unpredictability? The answer to this within mimetic theory is: no. The stock market, as Jean-Pierre Dupuy (2013) has argued, is mimeticism at its purest: people buy and sell stocks in accordance with trends; that is, in keeping with the swarming, collective, mimetic desires of others. Unpredictability is the equivocal emergent in a system of univocal similarity. Indeed, the desire to break with the desires of others along the lines of market trends is itself a mimetic desire. The shared desire is still to make money and thus to conform to the given complex, bureaucratic economic order. In Manifesto (2015), the stock market becomes an analogy for art, not just in reflecting its increasing commercialisation, but also reflecting the mimeticism embedded in art praxis. The shared desire, beneath all apparent trends and conflicts, is still to make art; to fit into the given complex artistic order. This is neither negative nor positive, but is noted here to stress that simplistic conceptions of artistic autonomy are simply wrong. Even if the nature of the relation between the artist and the art work to the larger context cannot be precisely delineated, the mimetic relation is nevertheless impossible to ignore.

This mimeticism is indicated most starkly by the repetition of the word "art" in the film. In various quoted Futurist manifestos, for example, traditional 'art' is utterly reviled and rejected, yet 'art' itself is not rejected. This, then, is the other desire accompanying the desire to break with the past, namely the repeated desire to create art. But how can two apparently contradictory desires co-operate? How does one stage, as Marinetti does, such a vehement repudiation of the entirety of everything done in the past in art and yet propose that what one is doing now or will do is nevertheless still acceptable as 'art'?7 Here, again, in this anti-dialectic of endless negations, is the promise of Groys's conception of modern art as dialectic without synthesis. The oppositional rhetoric of modern art - together with naïve claims of novelty - mask a deeper mimetic desire, namely the desire to be the guardian of (whatever) 'art' (is), albeit only temporarily.8

If tradition is rejected, it is because it has somehow failed to manifest 'art' to the world in keeping with the times. I would suggest that even the radical temporalisation of art is a mask behind which is a powerful transpersonal principle: mimetic desire. Still, the precise nature and content of this mimetic desire requires some elucidation.

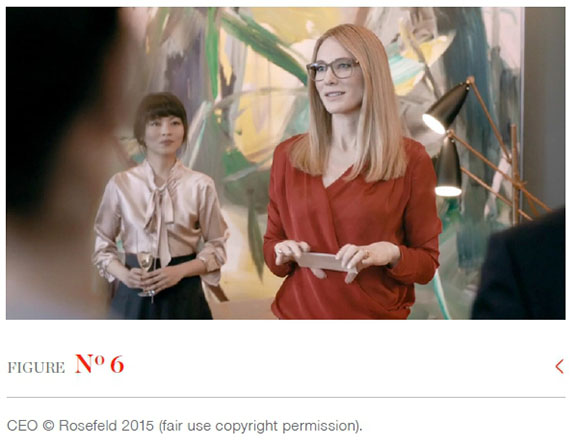

Second repetition: ressentiment

One of the subtler but more provocative moments in Manifesto (2015) has Blanchett taking on the role of a CEO at a private dinner party (Figure 6). She delivers a speech amidst various signs of social sophistication: elitist attire and wine included. After the speech has been delivered - a speech that clearly bores many listeners, and even seems to bore Blanchett's rather cold and detached character - Blanchett's facade is greeted by a number of people, and her forced smile and flippant commentary on the lives of others in this scene indicates a disconnection both with the show she is putting on and with herself. She seems polite, but there are indications that she does not want to be. The entire event seems fake. Everything is just for show. Then, in one brief moment, the facade of politeness drops: honesty is allowed, but only for an instant.

Blanchett's CEO happens to look into the eyes of a person whose back is turned to us - and then snubs him to talk to someone else instead (Rosefeld 2015). The illusory repetitions of etiquette are broken. This is very much an echo of Blanchett's earlier CEO speech, which follows the text of Wyndham Lewis's Manifesto (in Rosefeld 2015), 'We need the unconsciousness of humanity - their stupidity, animalism and dreams. The art-instinct is permanently primitive. We only want the world to live, and to feel its crude energy flowing through us'. In this scene, therefore, we find a clear contrast between word and image: between the primitive and the apparently cultured. This is a helpful symbol for the contrast in the desires of the manifesto writers: the conscious desire for novelty, which seeks to maintain the illusion of an autonomous break with the past, is rooted in an unconscious and thus misrecognised mimeticism, since, as Girard (2016:343) contends, the mimetic is the 'real unconscious'.

To better understand the presence of such opposite desires, it helps to consider the presence of the kind of emotivist moralism required for the writing of a manifesto. It is intriguing to notice how frequently in manifestos the "new" is framed as a moral category, while the "old" is given the status of the immoral. This indicates the presence of what Nietzsche understood by ressentiment (Girard 2016:353; Nietzsche 1996:22), which is, as Tomaso Tomalleri (2015) argues and as Max Scheler implies (2007:30), a mimetic phenomenon. The term ressentiment does not directly translate into the English resentment. Instead, it has become a technical term in philosophy, suggesting a 'reversal of the evaluating gaze' in the face of an inability or failure to achieve the ideals of an original values structure (Nietzsche 1996:22, §10). It involves a 're-ordering of the sentiments' (Ten Elshof 2009:70), such that what was previously regarded as praiseworthy - that is, worthy of emulating and envying - ends up being recast as worthless garbage (Scheler 2007:30). Action - or in the terms of this paper, artistic creation - 'seeks out its antithesis in order to affirm itself' (Nietzsche 1996:22, §10). As Nietzsche (1996:22, §10) explains, with reference to 'slave morality',9ressentiment requires 'an opposing outer world' to be able to act. It is therefore an action (or activism) entirely constructed from reactivity (reactivism) and, one could even say, passivity (Scheler 2007:25). This is what makes it possible to consciously reject tradition (declaring it a betrayal of "art"), while unconsciously affirming it (in reasserting the predominance of "art"). The fact that the referential locus seems to be external to the self also ensures the eventual negation of the self; indeed, the eventual negation of the self (or the artistic movement) in the end is merely a symptom of an absence of genuine selfhood at the beginning (Scheler 2007:87). Ressentiment renders the self essentially submissive; that is, as merely receptive to the mimetic desires of others.

The quintessential illustration of ressentiment is Aesop's fable about the fox and the grapes (Frings 2007:7; Scheler 2007:46). The fox, unable to acquire the desired grapes, maintains his sense of dignity and superiority by denouncing the prize as being mere 'sour grapes'. The actual state of the grapes, naturally, is not the issue for the subject who makes the evaluation. Importantly, '[t]he fox does not say that sweetness is bad, but that the grapes are sour' (Scheler 2007:46). The emotional frame is what has shifted, although the resulting 'revaluation of values' - another Nietzschean (2003:152, §9[77]) phrase, which is employed by Groys (2014) in relation to the concept of the 'new' in art - always relies on the point of reference of the original values. Ressentiment suggests an 'impulse to revenge' without the 'revenge itself', 'The impotency and powerlessness concerned blocks the venom of ressentiment from being washed away by a factual revenge' (Frings 2007:7). Crucial here, again, is the fact that ressentiment is rooted in mimetic desire - more specifically, an 'acquisitive' mimetic desire - even though it appears in the form of an action that opposes the original, copied desire. In Aesop's fable, for example, the fox rejects the grapes precisely because he wanted them. And in the case of, among others, Marinetti's tirade against traditional art: in all likelihood, at least as the logic of mimetic theory suggests, he rejects tradition on the basis of a failure to be able to live up to it; he lowers the standard in order to be able to achieve it. Thus, 'the criticism accomplishes the very thing it pretends to condemn' (Scheler 2007:37).

Also crucial is the fact that ressentiment involves a mix of hatred and admiration, although it is hatred that determines the apparently 'ethical' outcome (Scheler 2007:43), in this case the assignment of a moral status to that which replaces what was originally envied. Tzara's (2011:137) realisation of the underlying structure of the manifesto as involving not merely a goal or ideal but also fulmination against something 'other' demonstrates the essential consequence of the ressentiment, namely scapegoating - albeit a kind of scapegoating that inverts the usual mimetic structure. In ressentiment, it is the underdog or subordinate that rages against the elite, and the powerless that rage against the apparently powerful. The original regime is regarded as the enemy, not because it is tyrannical but rather because the underdog's weakness is tyrannical. To notice this is to notice that the seeming moral (and artistic) higher ground of the manifestos has very little, if anything at all, to do with morality (or even aesthetics). What is perceived by the manifesto writer is an apparent oppressiveness by some dominant power or ideology; but what is not perceived is that it is not as much the power or ideology that oppresses as it is the feeling of powerlessness in the writer. To convert this sense of powerlessness into a feeling of moral superiority is one of the fundamental deceptions of ressentiment. Recognition is falsified (Scheler 2007:45); misrecognition, what Girard calls méconnaissance, is codified and normalised. The underdog's weakness becomes the true tyrant - an example of what Adam Katz calls 'victimocracy' (in Katz & Gans 2015:148).

One of the most obvious features of the manifesto is the insistent and repeated protest against the establishment, whatever that somewhat arbitrarily selected establishment happens to be. This is articulated, often, in very unremitting terms - and on the surface this would suggest an appeal to what Nietzsche (2017:449, §800) refers to as the 'strength' and 'power' of the artist. However, given the doubling of desires and the obvious overtones of ressentiment it manifests, as highlighted by Rosefeld's filmic repetitions, it becomes more likely that what is being announced is the feebleness of the artist: the artist's inability to match or surpass tradition, and thus the concomitant tirade against tradition. If tradition can be utterly derided and dismissed, it will no longer seem to be competition. The artist will then be able to assert not only his or her illusory autonomy, but also dominance over what constitutes 'art'. This is an example of Girard's (2017:255) contention that when acquisitive desire is exaggerated, the model becomes not a rival to be argued with but an obstacle to be destroyed. The tirade against tradition is a refrain in Manifesto (2015), and yet tradition's role is implicitly confirmed; even disavowal requires affirmation. The affirmation is unavoidable since it is on the basis of the affirmation (repetition) of the desire of the other that rivalry is established.

Third repetition: ritual and mimetic crisis

So, how does this relate to the manifesto as a genre? By now, I have demonstrated, with the aid of Rosefeld's rhetorical-hermeneutical repetitions, that the manifesto itself can easily be thought of in terms of mimetic desire. To a significant extent, it is a genre rooted in a mimetic rejection of mimesis. But this argument is not yet sufficiently particular, since there are many texts that could and do function along the lines of mimetic desire. However, already we can add to this evident mimeticism a trend for manifestos to manifest ressentiment, although I also recognise that this will not always be the case, even if exceptions do not overrule the rule. Before I begin to formulate my final contentions around the manifesto as genre, a further aspect of Rosefeld's filmic stress on repetition needs to be explored, especially with reference again to the tension between the apparently new and so-called old.

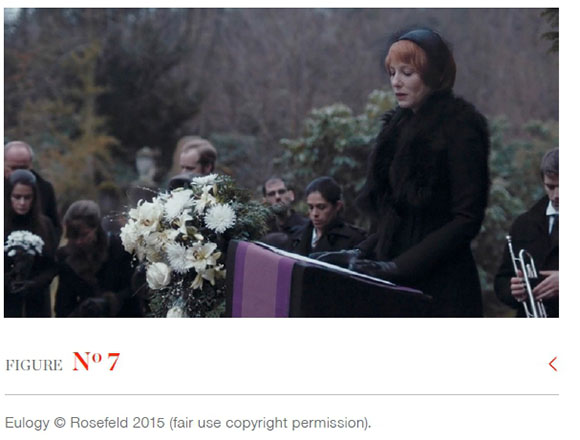

Two scenes, hinging on ritual, are particularly pertinent in this regard. The first takes the form of a funeral, which is combined with a eulogy delivered by Blanchett (Figure 7). The ritual affirms tradition through its recognition that tradition has died. However, the aggressive and jarringly funny eulogy seeks to lay that tradition to rest. The eulogy itself contains this doubleness: repetition that both consciously denies and unconsciously affirms, as in the words of Francis Picabia (slightly altered by Rosefeld),

'You are all complete idiots, made with the alcohol of purified sleep. You are like your hopes: nothing. Like your paradise: nothing. Like your idols: nothing. Like your political men: nothing. Like your heroes: nothing. Like your artists: nothing. Like your religions: nothing' (Picabia 2011:165; in Rosefeld 2015). These words, replete with the rhetoric of repetition, are echoed by the words of Louis Aragon:

No more painters, no more writers, no more musicians, no more sculptors, no more religions, no more republicans, no more royalists, no more imperialists, no more anarchists, no more socialists, no more Bolsheviks, no more politicians, no more proletarians, no more democrats, no more bourgeois, no more aristocrats, no more armies, no more police, no more fatherlands, enough of all these imbecilities, no more anything, no more anything, nothing, NOTHING, NOTHING, NOTHING. (Aragon, in Rosefeld 2015)

Tradition is also juxtaposed against the new in a scene in which Claes Oldenberg's 'I am for an art' manifesto (1961) is recited as a very lengthy grace said by a "traditional mother" with her family before dinner (Rosefeld 2015; Oldenberg 2011:352-355) (Figure 8). Again, we have an affirmation: prayer is one of the most ancient forms of human utterance - an affirmation, among other things, of human dependence and need, and of a desire for divine blessing. And yet, the use of Oldenberg's manifesto as a prayer, which only makes sense in the context of the givenness of prayer, overwrites both the original form and content of religious utterance and devotion. Picabia's (2011:165) insistence that 'religion' is 'nothing' is enacted in this scene. The intimation of this is that for tradition to be rejected it must be replaced with something else, although paradoxically the traditional is still what would legitimate what has replaced it. As in the funeral scene, the emphasis in this scene is on the repetitiveness of ritual. Oldenberg's Manifesto endlessly relies on anaphora in the form of the phrase 'I am for an art which is then followed by a range of 'qualifiers' describing the kind of art that Oldenberg is in favour of:

I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum. I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all. I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap and still comes out on top. I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary. I am for all art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself ... (Oldenberg 2011:352-355).

To have Oldenberg's Manifesto recited as a prayer is to be confronted both with the stability in anaphora and a kind of barrage of turbulent variations. In grappling with Oldenberg's words, one finds, indeed, that the 'art' that he is 'for' is not defined at all. It reflects a desire for everything that amounts to a desire for nothing in particular. The chimera at the outset of his manifesto ('an art that is political-erotical-mystical') is nonsensical; it offers a kind of ontological void. Art is this chimera: it is 'whatever is necessary' (Oldenberg 2011:352) even if what is necessary is only violence.

In all of this, Rosenfeld exposes how the manifesto as genre has become ritualised. Even the variations in content confirm the ritualistic nature of the form. And Girard (2017:45) explains that ritual is, in many cases, a remnant of the founding murder upon which culture itself was formed. It is a remnant that obscures the original violence; it is, in other words, the ressentiment ethos that obscures an original pride, envy and hatred, and also covers up an original crime against the scapegoat. This is the subtext of the manifesto as genre: an expulsion that is repeated and ritualised (Bubbio 2018:61). To manifesto is, in adolescent fashion, to refuse to look at the victim upon whose 'death' one's 'life' is constructed - the victim one has created in an attempt to affirm one's own authenticity.

It is in keeping all of the above in mind - namely the various repetitions in service of the intersection of mimetic desire, ressentiment and ritual - that we at last may begin to reframe the nature of the manifesto itself.10 In the above argument, and given the interpretive coordinates offered by Rosefeld's film, my primary contention is that the manifesto as a founding text functions less in terms of the apparent elucidation and clarification of the aims of the given movement than it does as a form of hermeneutic mystification. It functions much in the same way that mythology does, at least as Girard (2017:169-170) sees it: to blind us to the darker desires driving the artistic impulse, as well as the darker manifestations of those desires. As a result, we may fail to see that the art created to reflect the ideals espoused in any given manifesto may well be, so to speak, drenched in blood, sweat and tears - not just the blood, sweat and tears of the artist but of anyone upon whose corpse a new culture can be formed.

Intentions are not so much stated as masked; meaning is not to be understood but obscured. As Tzara's formulation suggests, the manifesto as form echoes what Paulo Diego Bubbio (2018) terms 'intellectual sacrifice': the heart of the manifesto as genre and form is not to be found in its affirmations, but in what it rejects without explanation or rational justification (although emotional justifications are abundant). Indeed, it is clear, although only on critical inspection, that the novelty presumed and proclaimed by manifestos would be impossible without the expulsion of something else - a "victim". And, as Bubbio (2018:77) writes, '[t]he entire mimetic victimage ... necessitates an 'other,' individual or symbolic, likewise caught in the mechanism's web'. Without this "other" playing the role of the scapegoat, 'the entire mimetic-sacrificial edifice collapses' (Bubbio 2018:77).

This is something confirmed repeatedly throughout Rosefeld's film, but is particularly well symbolised towards the end of the scene involving the traditional mother saying grace: the traditional father gets up and begins to carve up the dead bird that they are about to eat, while the mother pours gravy into it and while their son watches (Figure 9). The camera then shows the family eating and then pans to the show us the sitting room next to this dining room, in which we see a number of taxidermied animals and animal furs, and a live crow (Figure 10). The symbolism here is fairly clear, given the context of the film: life emerges with and out of death. With mimetic theory in mind, this may be put more strongly: culture emerges out of violence.

With this in mind, an even more provocative conception of the manifesto is allowed, namely that the manifesto functions, sometimes consciously and sometimes unconsciously, not just as the death warrant of some unsuspecting scapegoat, but also as a kind of suicide note. Given the often vicious mimetic rivalry that underpins manifesto writing, although sometimes articulated in the subtler language of ressentiment, what appears at first as self-legitimation is ultimately the undermining of self. The sentiments of Marinetti (2011:7) become typical of anyone who writes a manifesto and even of any manifesto, 'The oldest among us are thirty: so we have at least ten years in which to complete our task. When we reach forty, other, younger and more courageous men will very likely toss us into the trash can, like useless manuscripts'. Manifesto writing, on the whole, involves a commitment to the absolutely immanent, with only scant commitment to the past or the future. Because it conforms to the pattern of ressentiment, as tamed and concealed revenge, it preemptively announces its own irrelevance and demise. Thus, Chesterton's (1908:9) scathing remark on the modernist commitment to the new and often merely fashionable, 'It is incomprehensible to me that any thinker can calmly call himself a modernist; he might as well call himself a Thursdayite'.

Then, finally, the manifesto as genre seems to intimate something of the avant-garde artist's position within a field in mimetic crisis. Artistic innovation does not have to operate in mimetic crisis, but manifestos do reveal something of the perpetual return of such crisis. Girard's contention is that in the modern world, scapegoating no longer works: the sacrifice does not "take" and the consequence is an escalation to extremes that requires ever new scapegoats. The victimage mechanism that acts as initial foundation can only ever be an unstable base upon which to build anything. When Groys suggests that the field of modern art is structured according to the logic of contradiction, he comes close to noticing, without quite realising, the degree to which the avant-gardist mindset is a state of pure mimesis and unbridled rivalry and ressentiment. What appears to stem from a commitment to novelty, from what we can tell from the many manifestos already written, is more likely to be the result of envy: a fierce desire not for novelty but outdo the one/s imitated. Of course, this cannot possibly be regarded as a total explanation of the nature and meaning of manifestos, but it is certainly a dimension of the avant-garde mindset that has hitherto been downplayed, if not outright neglected. It is the reminder that however we may conceive of the artistic enterprise, and whether we judge artistic creation harshly or favourably, it is always imitation that is the mother of invention. And yet, the artist does not always want this to be known, either by others or by himself, lest the audience become aware of the weakness upon which his apparent strength has been constructed: 'Woe betide anybody whom we catch repeating these infamous words of ours!' (Marinetti 2011:8).

Notes

1 . Plato's apparent tirade against mimesis is far from an outright rejection of mimesis. The issue for Plato is whether the copy moves away from the original form (the Good) or whether it signals, in the consciousness of the philosopher, a return to the original form (the Good). See the discussion by Schindler (2008:283-336).

2 . This is pertinent, given that Rosefeld (2016) advises young filmmakers to 'forget about existing recipes' in their creative work.

3 . Much has been written on the manifesto as a genre, and for the sake of space and the present argument much needed to be omitted. An excellent engagement with writing on the manifesto as a genre is Galia Yanoshefsky's "Three decades of writing on manifesto: The making of a genre" (2009).

4 . Throughout this paper, a threefold philosophical distinction with regard to speaking of being is employed: (1) univocal, (2) equivocal and (3) dialectical. Briefly put, the univocal concerns the immediate, determination of meaning, apparently apart from mediation. This emphasises the obviousness of unity over variation, multiplicity, mediation and difference, and is largely ignorant of equivocation. Beyond this univocity, the equivocal concerns the ambiguities in being, and stresses difference, otherness and even 'unmediatability' over similarity. The dialectical refers to the modernist, especially Hegelian, trend towards recovering the univocal without entirely denying the truth of the equivocal. It suggests the self-mediation of otherness. Thus, with the dialectical, reason overcomes otherness by prioritising a mediated unity over unmediated difference (see Reyburn 2015). A fourth way of speaking of being, the metaxological or analogical, is not referred to here owing to the constraints of the paper itself. The question of the relation between the univocal, equivocal and dialectical is one explored at length by philosopher William Desmond (See, for example, Desmond 1995:xii-xiii).

5 . Marinetti's own manifesto sets the stage for this irony: to stake a claim is to predict the rivals that will stake their own claims against you: ' ... When we reach forty, other, younger and more courageous men will very likely toss us into the trash can, like useless manuscripts. And that's what we want!' (Marinetti 2011:7).

6 . To qualify this statement, it helps to bear in mind that the Hegelian frame presumes the predominance of antithesis or negation. As JM Fritzman (2014:3) explains, 'Although the thesis comes first in the order of narration, it actually emerges as a reaction to the antithesis. That is, what we are calling the thesis is recognized as a thesis only after it has been contested by the antithesis. Prior to that, the thesis is not explicitly articulated'. This is to say that the 'thesis is a product of the antithesis' (Fritzman 2014:4). Hegel presumes the predominance of mediation; that is, the possibility that the thesis can be reconciled with the antithesis via mediation. However, if we follow Groys, it seems that the avant-gardist gesture involves a certain refusal of mediation: the thesis is not clarified by its negation, as it would be in Hegel's dialectic, but obscured. See also Scheler (2007:41) on this idea in relation to ressentiment, which is discussed below.

7 . The famous question posed by Rudyard Kipling is underscored here: ' ... is it Art?'

8 . The sheer temporary nature of this guardianship can be called into question, of course, since the terms of whatever "art" is or will become are still univocally set by the modern artist.

9 . Nietzsche equates this slave morality to Christian morality, but Max Scheler (2007:55-78) has shown that in this respect Nietzsche is utterly mistaken, owing largely to the fact that he reads Christianity as essentially akin to a kind of socialism, which it is not. However, it is arguable - as Groys even suggests and as much in the imagery of Rosefeld's Manifesto confirms - that the modernist break in art is very much in keeping with the Nietzschean rejection of Christianity, since what is "traditional" in art that is railed against is very much bound up in the legacy of Christianity, especially with regard to its narrative and emphasis on positive virtue. This, however, is a complex issue that goes beyond the scope of the present paper.

10 . I recognise the risk of generalising too much, given that the manifesto form will necessarily include exceptions to the rule. Nevertheless, it is safe to say that in the context of Rosefeld's film, together with the analysis I have given thus far, as well as in keeping with the definitional coordinates of the avant-garde, the reframing of the manifesto as genre that I offer here, while involving generalisations, is nevertheless specific enough to offer further possibilities of analysis.

REFERENCES

Bittner, R. 2003. Introduction, in Nietzsche: Writings from the late notebooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University:ix-xxxiv. [ Links ]

Bubbio, PD. 2018. Intellectual sacrifice and other mimetic paradoxes. East Lansing: Michigan State University. [ Links ]

Chesterton, GK. 1908. All things considered. London: Methuen. [ Links ]

Danchev, A. (ed). 2011. 100 artists' manifestos: from the Futurists to the Stuckists. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Desmond, W. 1995. Being and the between. Albany: Suny. [ Links ]

Frings, M. 2007. Introduction, in Ressentiment, by M Scheler, translated by LB Coser & WW Holdheim. Milwaukee: Marquette University:1-18 [ Links ]

Girard, R. 1966. Deceit, desire and the novel: self and other in literary structure, translated by Y Freccero. London: Johns Hopkins. [ Links ]

Girard, R. 1991. A theatre of envy: William Shakespeare. South Bend: Angelico. [ Links ]

Girard, R. 2005. Violence and the sacred, translated by P Gregory. London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Girard, R. 2016. Things hidden since the foundation of the world, translated by S Bann & M Metteer. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Groys, B. 2008. Art power. London: MIT [ Links ]

Groys, B. 2016. On the new. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Katz, A & Gans, E. 2015. The first shall be last: rethinking anti-Semitism. Boston: Brill Nijhoff. [ Links ]

Kiesel, T. 1972. Repetition in Gadamer's hermeneutics. Analecta Husserliana 2(1):196-203. [ Links ]

Manifesto billboard. [O]. Available: https://www.sudbury.com/lifestyle/indie-cinema-presents-sudbury-premiere-of-manifesto-thursday-825736 Accessed 25 January 2019. [ Links ]

Marinetti, FT 2011. The foundation manifesto of Futurism (1909), in 100 artists' manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists, edited by A Danchev. London: Penguin:1-8. [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. 1996. On the genealogy of morals, translated by D Smith. Oxford: Oxford University. [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. 2003. Nietzsche: writings from the late notebooks, translated by R Bittner. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [ Links ]

Nietzsche, F. 2017. The will to power, translated by RK Hill & MA Scarpitti. London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Oldenberg, C. 2011. I am for an art (1961), in 100 artists' manifestos: from the Futurists to the Stuckists, edited by A Danchev. London: Penguin:351-355. [ Links ]

Pickstock, C. 2013. Repetition and identity. Oxford: Oxford University. [ Links ]

Reyburn, D. 2015. Laughter and the between: GK Chesterton and the reconciliation of theology and hilariy. Radical Orthodoxy: Theology, Philosophy, Politics 3(1):18-51. [ Links ]

Rosefeld, J. (dir) 2015. Manifesto [Film]. Australian Centre for the Moving Image. [O]. Available: https://www.hollandfestival.nl/media/4366708/manifesto-manifesten-engels.pdf Accessed 14 August 2018. [ Links ]

Rosefeld, J. 2016. Text as pure thought and pure poetry. [O]. Available: https://creativescreenwriting.com/manifesto/. Accessed 25 January 2019. [ Links ]

Scheler, M. 2007. Ressentiment, translated by LB Coser & WW Holdheim. Milwaukee: Marquette University. [ Links ]

Schindler, DC. 2008. Plato's critique of impure reason. Washington: Catholic University of America. [ Links ]

Ten Elshof, G. 2009. I told me so. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Tomelleri, S. 2015. Ressentiment: reflections on mimetic theory and society. East Lansing: Michigan State University. [ Links ]

Tzara, T. 2011. Dada Manifesto (1918), in 100 artists' manifestos: from the Futurists to the Stuckists, edited by A Danchev. London: Penguin:136-144. [ Links ]

Winkiel, L. 2008. Modernism, race, and manifestos. Cambridge: Cambridge University. [ Links ]

Yanoshevsky, G. 2009. Three decades of writing on manifesto: The making of a genre. Poetics Today 30(2):257-286. [ Links ]