Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.33 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a11

ARTICLES

Under Priscilla's eyes: state violence against South Africa's queer community during and after apartheid

Brian Michael Müller

School for African & Gender Studies, Anthropology & Linguistics, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa brian.michael.muller@gmail.com | http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8177-454X

ABSTRACT

Using South African performance artist Athi-Patra Ruga's ...the Naïveté of Beiruth (2008) photographic series as its genesis, this article employs critical approaches to semiotics and textual analysis to examine the history of police brutality in South Africa with a focus on the experiences of the queer community both under apartheid and after the transition to democracy - a history that repeatedly doubles back to the former-South African Police Force headquarters: John Vorster Square/Johannesburg Central Police Station. For queer subjects, South Africa's transition to democracy in 1994 brought with it many significant de jure changes to the daily lived reality of life in South Africa. However, misconduct and violence at the hands of the police - referred to as 'Priscilla' in the gay South African argot, Gayle - continues under democracy albeit of a divergent nature. Through Ruga's radical aesthetic and disruptive artistic intervention with the Johannesburg Central Police Station - a site which has deeply penetrated South Africa's cultural imaginary - this paper examines state violence against those who are identified as queer to expose the limits of the Rainbow Nation project, question the transformation of the South African police, and serve as an unsettling reminder of the complex and often dangerous societal position of women and queer subjects in South Africa. Significantly, while predominantly phenomenological in nature, this article to also partly auto-ethnographic as I draw from my own experience as a queer subject born in apartheid-era Johannesburg and living in democratic South Africa.

Keywords: State violence; Athi-Patra Ruga; queer; Johannesburg Central Police Station; John Vorster Square; South African Police Force; South African Police Service; photography.

The night is eating us out of futures we believe we deserve.- K. Sello Duiker, The Quiet Violence of Dreams (2001).

INTRODUCTION

I wish to begin this paper with a personal rumination on a single photograph: ...the Naïveté of Beiruth 4 (2008) (Figure 1) created by queer South African performance artist Athi-Patra Ruga.1 In the image, a figure - who the viewer comes to know as Beiruth from the project rationale (see Stevenson Gallery 2008) - frolics through a parking lot outside the Johannesburg Central Police Station (formerly John Vorster Square). She is clad in striking attire: red stilettos, black fishnet stockings drawn across muscular legs, a bright floral-printed leotard cinched at the waist by a thick coral-coloured belt accentuating a curvaceous body.2 The photograph captures her mid-stride as she runs through a flock of pigeons taking flight; they fill the air in a flurry of grey wings. Beiruth's large black wig billows around her face and shoulders, arms bent and hands extended in front of her as though preparing to grasp one of the birds. She is visibly exhilarated by her escapade. Like a child chasing after birds in the park, the feelings of excitement and glee are almost tangible.

This image, however, is not an uncomplicated one.

The parking lot's asphalt surface is covered in curved lines and irregular arcs extending the width of the frame and the site's historical significance as a locus of apartheid-era torture, violence and human rights violations - what Miller (2018:129) refers as the 'space of historic violence' - bleeds into my interpretation and I read these lines as a visual echo of chalk outlines drawn around bodies at a crime scene. Used to preserve evidence, these chalk lines are markers of the past in the present. In this light, I read the birds, photographed in their ascent towards heaven, as embodying the spirits of the dead as they leave the body. The imagery speaks of a haunted landscape, as if recalling where bodies once lay: the bodies of freedom fighters like Ahmed Timol and Matthews Mabelane whose lives came to an abrupt end in this parking lot at the hands of the South African Police Force's (SAP) high-profile Security Branch and whose deaths remain largely shrouded in mystery and doubt: Timol died in 1971 after allegedly jumping from the tenth floor of Johannesburg Central Police Station while in police custody and, similarly, Mabelane died in 1977 under markedly similar (and equally suspicious) circumstances (see Truth and Reconciliation Commission 1999).3

In my reading, it is the sharp juxtaposition of these two narratives - that of blind joy and violent death - within the same frame which points to Beiruth's ascribed 'naïveté'.

The absurdly oversized black wig and helmet covering Beiruth's eyes prevents her from seeing the world around her but, more significantly, harks to an inability to see beyond the "rainbow nation" veneer of post-apartheid South Africa.4 It is both a historical blindness to the location's unsettling past and its entanglement, to adopt Nuttall's (2009) terminology, with the present, as well as a failure to see true and substantive change despite the country's transition to democracy in 1994.

This image is one of five in the ...the Naïveté of Beiruth (2008) series which, according to Ruga, was inspired by the 2008 sexual assault and public 'humiliation of Nwabisa Ngcukana in an event that would be [later known as] 'The Miniskirt Attacks' (Ruga as quoted in Hunkin 2016:[sp]) at the Noord Street taxi rank in Johannesburg and was created in the shadow of the Johannesburg Central Police Station - a prominent site of apartheid-era 'humiliation and brutality', a site 'saturated with traumatic, painful memories' (Miller 2018:125).5 By confronting South Africa's on-going fight against both gender-based and state violence, Ruga's disruptive artistic intervention exposes the limits of the rainbow nation project, questions the extent of the transformation of the South African police and serves as an unsettling reminder of the complex and often dangerous societal position of women and queer subjects in South Africa. For women and queer subjects, South Africa's transition to democracy and the adoption what has become commonly known as the "equality clause" (Section 9 of the Bill of Rights) brought with it many significant de jure changes to the daily lived reality of life in South Africa; much research, however, has been published highlighting a significant delta between de jure and de facto life under democracy (Scheepers & Lakhani 2017; Munro 2012; Thomas 2013, 2014).6 In terms of the South African Police Service (SAPS), police abuse and misconduct targeted at women and queer subjects continues today under democracy as it did under apartheid albeit of a divergent nature (see Scheepers & Lakhani 2017; Amnesty International 2013; Holland-Muter 2012; Nath 2011). Ruga's image, thus, constitutes an aide-memoire of the failure of the state to fully actualise the freedoms and rights enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa and notes how the fight for equality is more urgent now as it falls within the gaps and shadows of the dominant collective political consciousness.

It is from this context that both Ruga's photographic series and this article are born. In this paper, I employ critical approaches to textual and semiotic analysis inspired by researchers and theorists like Barthes (1977; 1980) and Sontag (1977) to read Ruga's ... the Naïveté of Beiruth series and examine the history of police brutality in South Africa with a focus on the experiences of the queer community both under apartheid and post-apartheid - a history that repeatedly doubles back to the Johannesburg Central Police Station.7 While predominantly phenomenological in nature, I believe this work to also be partially auto-ethnographic as I draw from and am informed by my own experience as a queer subject born in Johannesburg under apartheid and living in democratic South Africa. Ruga's ... theNaïvetéofBeiruth series - drawing on architectural theory, political history, fashion, performance art, ethnography and other photography genres - offers the viewer a radical aesthetic to highlight the solemnity of the Johannesburg Central Police Station and its structural denial of South Africa's socio-political plight. The building and Ruga's photographs - themselves critical works of visual activism - underscore the disjuncture between South Africa's liberal and progressive rhetoric and the role of the police in protecting and enforcing this egalitarian legislation. More significantly, Ruga's images encapsulate the plight of those who defy the dominant heteronormative culture in the hope of increasing public engagement and fostering true social transformation.

Visualising violence and the birth of Beiruth

The camera played a key role in the policing of sex and gender during apartheid.8Historical accounts from the period reveal how during raids of queer bars, nightclubs, bathhouses, cruising spots and private residences and other queer(-friendly) spaces, police officers armed with cameras 'would line people up against the wall and snap pictures of as many faces as possible' (Retief 1993:20). Testimonies from a 1966 police raid of a private residence in Johannesburg - an incident that would become infamously known as the Forest Town Raid - recount how guests were detained on the premises for several hours before being interrogated and photographed (Retief 1993:30). Similar attestations emerged regarding the 1979 raid of The New Mandy's nightclub during which 'patrons were manhandled, photographed, verbally abused, and kept locked up in the building until morning' (Gevisser 1994:47). For queer subjects, this photographic process instilled fear that 'one's name and picture would appear in the daily newspaper' (Retief 1993:20). In some cases, Retief (1993:22) notes, the police invited the press to document their raids - in both text and photographs - for publication in the mainstream media. Given the conservative Calvinist and Christian Nationalist ideological climate of the apartheid dispensation, public disclosure of one's queer identity could result in unemployment (or at least limit earning potential), eviction from housing, social stigmatisation, alienation and exposure to myriad forms of violence on a daily basis (Wells & Polders 2004; Cameron & Gevisser 1994). Such an action constitutes intimidation and encroaches upon psychological warfare, forcing many queer subjects to hide their sexuality and live a double-life out of fear of repercussions - thereby perpetuating the invisibility of the queer community (see Retief 1993; Gevisser 1994).

It is, therefore, poignant that Ruga utilises photography as part of his disruptive artistic intervention with the Johannesburg Central Police Station. While the act of having a drink at a queer(-friendly) bar or attending a private party at the home of a fellow community member is an ephemeral, temporally-specific act, the SAP attempted to use photography to document and record these moments for posterity. In this way, the camera becomes a powerful bio-political tool of control and oppression striking fear of exposure into the queer community. Ruga, similarly, uses photography to capture and record Beiruth's temporal site-specific performance as well as the surrounding built environment with its symbolic link with the nation's violent and traumatic history and present.9 Moreover, it is precisely this intersectionality of violence, queer identity, complex social and political space, visibility (and the consequences thereof) that form the core of Beiruth's performance and, to a large extent, Beiruth herself.

Although Beiruth only formally came into existence in 2016, Beiruth's theoretical roots can be traced back to Ruga's childhood. Ruga's biography has been well documented elsewhere (see Dlungwana 2014; Whatiftheworld 2017) but his reflections on his childhood - particularly his navigation of and reaction to complex politico-spatial environments - provides critical insight into his interpretation of contemporary South Africa and his artistic praxis. Born in 1984 in Umtata, a town in South Africa's present-day Eastern Cape province and capital of the former Bantustan, the Republic of Transkei, Ruga recalls how he would go 'to East London for school and then go back to the Republic [of Transkei] to go stay and actually have a family' (Ruga as quoted in National Arts Festival 2014). Ruga's recollection notes how he had to frequently cross international borders thus embedding the concepts of movement and the navigation of complex political zones deep within his psyche. For Ruga, these dichotomous worlds forced him to adopt 'two different mentalities altogether': one for home and one for circumnavigating South Africa's apartheid dispensation; 'I was always aware of acting to assimilate to a certain space and to a certain context from a very young age' (Ruga as quoted in National Arts Festival 2014). Thus, importantly, Ruga's penchant for persona creation and the complex theatrics of performance were not originally fostered as tools for his artistic works but are, instead, formative survival mechanisms that echo the intricate identity politics queer subjects under apartheid had to navigate to prevent themselves being 'outed' and, therefore, targets of violence.

According to Ruga, a key inspiration behind Beiruth was the 2008 Miniskirt Attack against Nwabisa Ngcukana at the Noord Street taxi rank in Johannesburg (Hunkin 2016:[sp]). The incident involved the then-25-year-old Ngcukana being publicly stripped and paraded through the taxi rank before being drenched in alcohol and sexually assaulted because she was wearing a miniskirt (Gunkel 2011:6; Mitchell, Moletsane & Pithouse 2012:4). Despite the media attention this event received, this was neither a unique nor isolated incident: Mitchell et al (2012:4) note similar occurrences in a Durban township in 2007 and, reporting on Ngcukana's attack, The Sowetan newspaper revealed that security guards stationed at the taxi rank (as well as people working at an unidentified nearby shopping center) had witnessed analogous incidents to the extent that security guards were ultimately instructed 'not to allow women wearing miniskirts into the rank' for their own safety (Makhafola 2008:[sp]).

Nationally, sexual and gender-based violence is widely acknowledged as having reached and sustained such noteworthy levels that South Africa has become synonymous with some of the highest rates of sexual and gender-based violence in the world (Center for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation 2016; Vetten 2014; Adar & Stevenson 2000). More specifically, South Africa demonstrates 'corrective rape' rates on a unprecedented scale (Thomas 2013) and exhibits some of the highest rates of intimate partner femicide in the world (Mathews, Jewkes & Abrahams 2015; Abrahams, Mathews, Martin & Jewkes 2013).10 However, as Finchilescu and Dugard (2018:2) note, there are 'no reliable data' on sexual and gender-based violence in South Africa for myriad reasons spanning changes to/problematic legal definitions through to limited data collection methodologies and, consequently, detailed specifics and statistics are not readily available (see Wilkinson 2018). Beiruth's very existence, therefore, not only points to a moment in history when the disjuncture between South Africa's liberal constitution and the daily lived reality of marginalised subjects is brought to light but acts as a formal reminder that the extent of South Africa's sexual and gender-based violence problem is largely unknown.

While Ruga admits that he can 'never experience in full what it is to be a woman' (Ruga as quoted in Corrigall 2017:[sp]), performing as one of his avatars or performing in drag in public spaces is a high-risk activity and the threat of danger is ever-present. Fellow South African performance artist Steven Cohen - although white, privileged and from a different generation than Ruga - also uses queer visibility and feminine personas for his theatrical 'monster drag' performances (Sizemore-Barber 2016:192).11This methodology has frequently placed Cohen in danger locally and abroad; in a 2012 interview for example, Cohen described 'getting my arse kicked, spending hours in police stations talking about art ... I have been yelled at, mocked, spat on, hit, punched, [and] kicked' (Cohen as quoted in Jolly 2012) all while trying to execute his performances. Therefore, Cohen's recollection is a testament to and a warning about the omnipresent threat of violence that exists for both queer performance artists and practitioners who draw on drag for their performances.

Beyond Cohen and his contemporaries (Berni Searle, Pieter-Dirk Uys, Tracey Rose et al) whose performative works under apartheid and/or the early years of the democratic dispensation marked them as significant voices on the international performance art stage, South Africa is home to a growing new generation of performance artists and live art practitioners (see Panther & Boulle 2019). This group, significantly, includes many black- and queer-identifying subjects including FAKA (Fela Gucci [Thato Ramaisa] and Desire Marea [Buyani Duma]), Nicholas Hlobo, Umlilo (Siya Ngcobo), Selogadi Mampane, Ibokwe (Albert Silindokuhle Khoza), Odidiva (Odidi Mfenyana) and, of course, Athi-Patra Ruga. For many members of this group, site-specific performance art appears to play a central component within their artistic praxis.

Within the South African context, site-specific performance art holds a particularly symbolic role as site specificity itself is strongly linked to 'South African cultural practices of healing, shamanism, mourning, initiation and celebration' (Panther & Boulle 2019:3) and therefore these artistic works have a connection with a long-established and integral part of traditional South African culture. These links with 'mourning', 'healing' and other markers of significant phase and life transitions are central to many black queer practitioners' work highlighting the continued marginal positionality of women and queer subjects in South Africa: Queer visual activist Collen Mfazwe conceptualised State of Emergency (2014) in response to the violent 'corrective rape' and murder of then-28-year-old Thembelihle Sokhela. The performance piece was staged at Soweto Pride - itself created by activists and community members who rejected the 'commercial and depoliticized nature of Johannesburg Pride' (Craven as cited in McLean 2013:28) - and portrays the imagined rape and murder of one of its performers. During the performance, the performers were verbally harassed by onlookers and, ultimately, forcibly removed from the site by police. The work, as Thomas (2017:273-274) argues in her discussion of the performance, 'makes visible the lie that queer people have access to public space'. Similarly, internationally acclaimed queer visual activist Zanele Muholi has adopted performative elements in some of their work including acting as their own corpse at the launch of their Of Love and Loss (2014) photographic exhibition - itself an exploration of funerals and weddings in South Africa's black queer community - at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg. The performance signifies the possibility of Muholi's own queercide revealing how even fame and fortune cannot protect queer subjects from violence and death in South Africa and, more significantly, underscores the interconnected nature of visibility and violence ultimately arguing 'the need for a safe space to express individual identities' (Stevenson Gallery 2014:[sp]).12

John Vorster Square/Johannesburg Central Police Station

Beiruth's debut appearance occurred in ...of Bugchasers and Watussi Faghags (2008), Ruga's first solo exhibition at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg.13 Here, Buys (2009:80) notes that Beiruth was documented having 'prowled the nowhere places of Johannesburg inner city'; she crawls out of an open manhole and creeps out from dark, non-descript niches to squat on the pavement and run through the streets. Siegenthaler (2013:69) expresses similar sentiments when she argues that, in Beiruth's performances, the 'physical space of the city' is reduced to 'a stage, a backdrop for the actions of this alien'. For Siegenthaler, it is only through Beiruth's actions and her engagement with the concrete, brick and glass structures around her that the viewer is alerted to the 'surroundings that are bodily experienced by the protagonist' (Siegenthaler 2013:72). Although an intriguing perspective which speaks to Beiruth as an empowered protagonist and her ability to conquer any obstacles and hardships in her way, Siegenthaler reduces the urban landscape to a passive backdrop, interchangeable if and as necessary. While this may hold true for Beiruth's other performances - such as the Death of Beiruth (2008) series - the images of which depict no distinct geographic markers and thus could plausibly be exchanged for numerous other locations to support the narrative, this does not hold true for Ruga's .the Naïveté of Beiruth series set against the Johannesburg Central Police Station.

The monolithic Johannesburg Central Police Station first opened in 1968 as John Vorster Square, named in honour of then-Prime Minister of South Africa, Balthazar Johannes Vorster.14 The building was heralded as a state-of-the-art facility and regarded as a critical step in the development of apartheid South Africa's national security services as it housed every notable branch of the SAP in the same building (South African History Archive 2007; Segal & Holden 2008:141). The building - described by former detainee and Pan African Congress veteran Jaki Seroke as 'the pinnacle of torture chambers' (Seroke as quoted in Segal & Holden 2008:139) - soon became a notorious site of state-sanctioned violence and, as we shall see, became emblematic of apartheid South Africa's notions of racialised heteronormative masculinity which forbade 'all expressions of sexuality outside a same-race heterosexual marriage' (Human Rights Watch 2003:51). The site, significantly, is one that historically would have rejected both Ruga and his Beiruth persona on both racial and gendered terms - to a possibly deadly end. Under the apartheid regime, if either figure was seen running or hiding in the vicinity as witnessed in the ...the Naïveté of Beiruth series, it was arguably for their lives.

The apartheid regime, Gunkel (2010:28) argues, is best understood as being 'based on institutionalized white supremacy and as having underwritten its race regime through heterosexuality'. Thus, through a combination of Afrikaaner Calvinism and Christian Nationalist ideology, hegemonic Afrikaner masculinity placed (and continues to place) significant emphasis on morality, sexual purity and heteronormativity to promote a national agenda of dominance and prosperity (du Pisani 2001; Retief 1994). The perceived femininity and/or inferiority of queer subjects, therefore, marks them as 'un-Afrikaans' and existing 'outside tradition and culture and thus outside the nation' (Grunkel 2010:27). Consequently, queer subjects posed an intra-state threat to the national image of superiority and needed to be controlled - or, ideally, completely eradicated - to ensure the success of the apartheid scheme (Pieterse 2013:620; du Pisani 2001:169). Such control was achieved by means of intimidation, criminalisation, state-sanctioned medical experiments and, ultimately, homicide (du Pisani 2001:69).15Thus, as the working arms of the apartheid government, the SAP 'was at the forefront of enforcing racist laws to promote white hegemony' and protect the white male minority government (Newham, Masuku & Dlamini 2006:15). Therefore, the SAP played a crucial role in maintaining the government's desired racialised and gendered status quo through violence, intimidation and fear. A 1966 article in the Sunday Express, 'Police drive against vice "clubs"', notes how the South African Police were tracking 'organized' homosexual activity and 'probing the activity of 25 000 known homosexuals in Witwatersrand' (Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action AM2580). Such police actions were expressly intended to 'trace and wipe out homosexual clubs in Johannesburg' (Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action AM2580) and constitutes the cornerstone of the systematic erasure and destruction of queer culture and communities in South Africa on behalf of the state. John Vorster Square, therefore, as the headquarters of this violent and oppressive state body and frequent site of violence against queer subjects, becomes symbolic of apartheid South Africa's notions of racialised heteronormative power and masculinity.

John Vorster Square is arguably one of the principal sites of apartheid-era torture, violence and human rights violations and thus, as a site of embodied meaning, is a monument to a time of enforced racism and heteronormativity as well as a reminder of the criminalised and marginalised societally-enforced position of both Ruga and Beiruth. Jessie Duarte, African National Congress (ANC) Deputy Secretary-General and former detainee, echoes these sentiments, noting how John Vorster Square is the 'true embodiment of the violence of the apartheid system' (South African History Archive 2007). The building's top two floors, in particular, have spawned some of the most horrific stories of apartheid-era violence and depravity. Stories of the systematic non-stop torture of detainees resulting in hospitalisation or death - many of which were ex post facto staged to look like suicides and accidents to prevent any legal ramifications. As Michael Cawood Green's 'John Vorster Square' (1997), a poetic 'song' published in Green's Sinking: A Story of Disaster Which Took Place at the Blyvooruitzicht Mine. Far West Rand, on 3 August 1964 (1997), notes:

The top two floors are barred and sound-proofed so you can't call for a trial that's fair / Anyway they don't need a courtroom to keep you in John Vorster Square (Green 1997:147).

These two floors - the ninth and tenth - accommodated the Security Branch and were not easily accessible as, as Green notes, extreme security measures and technological innovations were employed to ensure isolation, control and power. From secret entrances and surveillance systems to separate lifts with security override capabilities, the space speaks to the myriad ways in which the building was conceived, designed and constructed to accommodate interrogation, torture and other illicit activities into everyday police practice while keeping these practices hidden from public view (Blaine 2012).

It was not only the building's interior that was designed as an apparatus of disciplinary power, the building's exterior was also a mechanism to psychologically influence the population. In Dry White Season (1979), South African novelist André Brink describes the building's exterior as 'tall and severely rectilinear, concrete and glass, blue, massive' (Brink 1998:57), marking the squat Modernist office block as 'oddly out of place' with its surroundings. Located at the 'wrong end' (Brink 1998:57) of Commissioner Street - Brink's value judgement ostensibly due to the building's proximity to Soweto and his highlighting of South Africa's national government's aversion thereof particularly in the wake of the 1976 Soweto uprising (see Glaser 2005; Chabedi 2003) - on the western margins of the Johannesburg Central Business District, the multi-storey structure towers over the nearby M1 freeway, sentinel-like, monitoring all those who enter and exit the inner city.17 The building's strategic placement ensures all those who enter the city are aware of a superior authority at work in the country, an omniscient Big Brother willing to bully, torture and kill to successfully achieve the apartheid agenda. In this way, the building's looming presence is symbolically similar to Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon, continuously reminding citizens of their assigned place in the national power structure in an attempt to psychologically impose the government's preferred version of citizenship and behaviour upon those within its influence.18

Today, writing in the post-apartheid present, the building stands almost entirely unchanged. In 'Erasing the Traces' (2002), Neil Leach discusses '"denazifying" the built environment' (Leach 2002:95) - by which Leach means 'the process of ridding the built environment of associations with a previous unpleasant regime' (Leach 2002:81) - of post-1994 Johannesburg and Pretoria drawing attention to the democratic government's limited re-appropriation and constructive re-use - what Leach refers to as the 'Bucharest syndrome' (Leach 2002:95) - of John Vorster Square.19 Leach raises concern about the extent to which police reform has occurred or is perceived to have taken place in the eyes of the broader public given that the building - emblematic of the police's history of brutality and corruption - remains largely unchanged. The 'representation of police reform,' Leach (2002:96) notes, 'remains as important as the reforms themselves' and, as such, leaving the building chiefly unaffected by the transition to democracy - to date, the September 24, 1997 name change from John Vorster Square to Johannesburg Central Police Station and the removal of a plaque and the large Vorster bust from the building's foyer on September 22, 1997 (Leach 2002) and the occasional coat of paint are the only known alterations to occur since democracy - marks it as symbolically outside the need for change and locates the police's actions as within the realm of acceptable policing. Leach expresses doubt, however, about the successful renaming and limited 'architectural repackaging' (Leach 2002:95) of John Vorster Square noting how its re-appropriation relies upon two fundamental premises: firstly, it relies upon the 'genuine change in police activities' that is 'perceived and accepted' by the South African public and, secondly, that 'any physical works to the building [.] should be works which facilitate the new spatial practices within that building' (Leach 2002:95).

The 2008 Royal Institute of British Architects' Corobrik Award was presented to University of Witwatersrand master's student Guy Trangos for his dissertation, '"In the Shadow of Authority": a proposed architectural intervention to transform the Johannesburg Central Police Station' (Royal Institute of British Architects 2009:[sp]). The theoretical project envisaged 'a new entrance, a large counselling facility, an oral history facility, a large exhibition space and an aviary, all inserted into, onto or between the buildings of the existing police station' (Royal Institute of British Architects 2009:[sp]). Trangos's proposed 'architectural repackaging', to draw from Leach's lexicon, visualises a dynamic, historically-aware and transparent space for both the new, post-apartheid police service and for South Africans at large. Such an intervention would push beyond the 'superficial gesture' (Leach 2002:95) of the current architectural transformation to show true engagement with the past and would be demonstrative of a conscious break from the police's former modus operandi thus subverting the silence and atrocities still inextricably tied to the building. Such an intervention would be in line with Leach's proposed socio-spatial remediation and would signify a distinct break from apartheidera policing and the hand-in-hand arrival of South Africa's new police service.

Queer subjects and the police apartheid

In ...the Naïveté of Beiruth 1 (figure 2), the first image in the sequence, Beiruth is photographed sitting in a runner's starting position on the sidewalk near the Johannesburg Central Police Station. I read Beiruth's body as one of pent up tension and anxiety. Her arms are kept close to her body with only the tips of her splayed fingers touching the pavement as if ready to sprint if/when necessary. A line of fear runs through the curve of her arched back as if forcefully trying to conceal herself by retreating into a small ball and hiding among the grass growing in the cracks in the pavement. She is shrinking her body down to the smallest possible size to avoid detection. Photographed against a brick wall, I read the dark bricks contrasting with the light grey stripes of mortar, the interplay of dark and light horizontal lines, as suggestive of a police lineup. Beiruth, photographed against this backdrop, is symbolically linked with criminals and unlawful activity despite South Africa's liberal constitution. This association marks her as a deviant and, cognisant of the potential violence she may face at the hands of the police, is attempting to stay out of sight of law enforcement officers while simultaneously positioning her directly in the line of fire.

In this context, the interplay between light and dark within the framework of criminality, my reading of ...the Naïveté of Beiruth 1 is permeated by the Immorality Act (Act 5 of 1927) and its various amendments which policed the intersection of race and sexuality under apartheid through, inter alia, strict anti-miscegenation legislation (see Retief 1994; Cameron 1994). The image brings to mind the criminalised interracial relationships of couples like anti-apartheid and queer rights activists Roy Shepherd and Tsepo Simon Nkoli. Nkoli recalls how, after a regrettable encounter with some photographs, he had the topics of his sexuality and miscegenation repeatedly raised while being interrogated and tortured in detention at John Vorster Square:

One policeman, who had seen snaps of white men in my photo album, became particularly angry. 'Why do you like fucking white men?' he asked 'What have they done to you? Why don't you have sex with your own people?' (Nkoli 1994:254).

Here, Nkoli's personal photographs - simultaneously small, tangible 'snaps' preserving Nkoli's treasured memories and, in the eyes of the SAP, 'proof' of immoral behavior and therefore justification for a particular brand of violence - enabled Nkoli to be targeted by the police because of his sexuality and relationships with white men: during his detention, police officers would 'bring in things like a baton and tell me to go fuck myself with it. They also said they'd put me in prison with others and get me raped' (Nkoli 1994:254). Such behavior was not uncommon, and while Rauch (2000:[sp]) argues that the 'iconic image' of the SAP officer as 'a rather brutish, uneducated, working-class, white, Afrikaans speaking policeman' was a curated projection not necessarily in-line with the overall racial profile of the SAP towards the end of apartheid, testimonies like Nkoli's bring to the fore questions about the true 'brutish' nature of the SAP. Nkoli's account, moreover, underscores the link between queer identity, the complex role of photography in the policing of sex and gender under apartheid, and the SAP's heavy-handed and systematic enforcement of state-sanctioned homophobia, racism and heteronormative violence.

In 1994, then-president Nelson Mandela announced the overhaul of the SAP noting the need to transition from a national police and law enforcement unit that ruthlessly enforced racist administrative terrorism and heteronormative violence under the guise of patriotism to one of national protection and community upliftment. This new job description was formally outlined in Section 205(3) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa:

The objects of the police service are to prevent, combat and investigate crime, to maintain public order, to protect and secure the inhabitants of the Republic and their property and to uphold and enforce the law.

The following year, the South African Police Service Act (Act 68 of 1995) concretised this community-orientated approach to policing advertised primarily through the renaming of the South African Police Force to the South African Police Service (SAPS).20By renaming the entire apparatus, thus shifting the lexicon from a 'force' to a 'service', the government attempted to semantically recode public opinion in favour of the new crime prevention, citizen rights and victim support-orientated justice system and differentiate it from its oppressive and violent government-controlled predecessor (Tait 2004:114). For queer subjects this reformation was critical.

Retief (1993:26) notes that although the apartheid regime enforced discriminatory laws against members of the queer community, these subjects did de jure possess 'certain elementary rights' including 'the rights to a proper trial and to protection from criminal victimization and violence'. These rights, however, do not appear to have been upheld by members of the police and, instead, appear to have been resolutely rejected in many cases. In fact, Retief (1993:43) notes, 'police abuse and discrimination' against queer subjects under apartheid were such 'serious problems' as to require 'urgent addressing'. Within the report, Retief cites his own independent research into police brutality including an interview conducted with a woman (identified only as 'D') who was arrested for kissing another woman in a Durban nightclub. At the police station, the officer working the case 'looked down her shirt and told her that all she needed was a good fuck and that he would release her if she let him do the honours' (Retief 1993:25). Similarly, in a 1992 interview with John Pegge, then-Director of the Gay Association of South Africa (GASA), Pegge informed Retief that GASA 6010's call center which provided counselling and support for the national queer community (particularly for those living with HIV/AIDS), handled approximately four to five reports of police abuse and misconduct monthly. These include instances of

police beating and raping men whom they detain in cruising areas; fabrication of evidence in 'public indecency' and 'soliciting' cases; and illegal police raids on homes of gay men in order to confiscate gay erotica and to obtain the addresses of other gays (Retief 1993:27-28).

Not only was this system of violence and intimidation designed to make daily life in South Africa impossible, it was also designed to be inescapable. Louis de Araujo, a South African expat living in Canada, recalls how these late-night raids on public venues and private homes by the 'thugs from the dreaded Vice Squad' could have serious long-term implications for those involved (regardless of their sexuality). De Araujo recalls one instance when he had an 'unscheduled sleepover at John Vorster Square [...] when the gay club where I was bartending was raided one night' (Hemming 2013:200-201). Not only did de Araujo undergo immediate punitive treatment for his association with the queer community thus adding to the demonisation of the queer community but, years later when he wanted to emigrate to Canada, was required to obtain a Police Clearance Certificate where his prior encounter with the SAP had potential consequences for his future prospects.

From within the archives, there is little discernable mainstream media coverage from the 1980s and early 1990s on police misconduct or the management of these raids but there are echoes of this unlawful behavior in the alternative press. One enlightening exposé on the treatment of queer subjects by police in Johannesburg and Pretoria was published in the April/May 1988 edition of Exit - one of South Africa's leading queer newspapers and one of the only locally produced publications to operate continuously since its inception in the mid-1980s (Davidson & Nerio 1995:225). The article reports that 'a number of complainants' were 'innocently accosted, or were subjected to soliciting actions and entrapment or harassment' at Zoo Lake and Emmarentia Dam in Johannesburg and Sunnypark in Pretoria - known cruising spots in the area (Police swoop on camping places 1988:3). The report outlines how individuals were arrested and then 'driven around in a white car for periods of around an hour' while being verbally threatened that their sexual orientation would be 'splashed across the newspapers' (Police swoop on camping places 1988:3). Other cases include civilians being assaulted or, in one instance, 'shot several times' (Police swoop on camping places 1988:3) after attempting to run away from the police. For those who were arrested and eventually taken into police custody - some were asked to pay an admission of guilt fine on the spot and released while others were released and told to appear at the police station the next day - they were taken to John Vorster Square where they were requested to pay the admission of guilt fine (Police swoop on camping places 1988:3).

In 1994, author and journalist Mark Gevisser and now-Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron, co-edited and published the 'path-breaking' (Gevisser & Cameron 1994:3) Defiant desire: gay and lesbian lives in South Africa. The book, highlighting 'the sexual politics coursing beneath the country's troubled passage to democracy', is a 'testimony to the range of gay and lesbian experiences' (Gevisser & Cameron 1994:back cover) under apartheid. At the time of publication, Defiant desire was South Africa's first-ever queer non-fiction book (Bauer 1994:[sp]) and is significant in that it 'details for the first time the extent to which homosexuality exists and flourishes in black communities and cultures' (Gevisser & Cameron 1994:3). This book, over two decades after its publication, continues to be a seminal text on the diverse experiences of queer subjects living under apartheid rule and, from the anecdotal and oral history evidence therein, slivers of fragmented stories emerge illuminating interactions between the police and the queer community.

One contributor (identified only as 'Joe') states that 'it was well-known that Priscilla [the police] would hang around the New Library to pick up information about the gay scene' (Gevisser 1994:30).21 The police would regularly stake out clubs, bars and other public venues accumulating information and infiltrating social functions dressed in plain clothes, to drink and dance with other party-goers before the police would 'swoop' (Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action AM2580).22 Such embedded policing appeared to be a fruitful undertaking and is generally accepted as the means by which police learnt about private parties, new queer(-friendly) venues and events for potential investigation and raids. In the case of private parties and community meetings, hosts made every effort to be discreet and 'protect the safety of our guests' (Gevisser 1994:24) - such as 'strict screening at the door' (Gevisser 1994:32) - thus preventing 'intrusion by either police or the media' (Gevisser 1994:32) and ensuring invitees would not be victimized or risking exposure.

'Police surveillance was a big thing' (Galli & Rafael 1994:137), confirms 'Jeremy', another contributor, as was fear of police. Consequently, many members of the queer community opted to socialise and be sexually explorative within what Peter Galli and Luis Rafael refer to as 'prison-houses of desire' (Galli & Rafael 1994:134). These architecturally fortified venues - including health clubs and tea-room bioscopes - were designed to reduce police intervention or, at the very least, stall a raid long enough to ensure patrons could stop any incriminating activities. Jeremy, referring to the London Health Club in Johannesburg, explains:

The Club had a swing door so that only one person could enter at a time. Should Priscilla [the police] raid, by the time they had all entered we would have had enough time to be engaged in healthy activities... We felt secure within the Club (Galli and Rafael 1994:138).23

While such actions signify a resilience and creative ingenuity to navigate apartheid's oppressive system and fostered the expression and exploration of 'dissident or illicit sexualities', to use Epprecht's (2004:12) terminology, in the face of the national Calvinist ideology, the very circumstances under which these actions took place perpetuates the notion of non-normative sexualities as shameful and needing to be hidden.

Queer subjects and the police: democracy

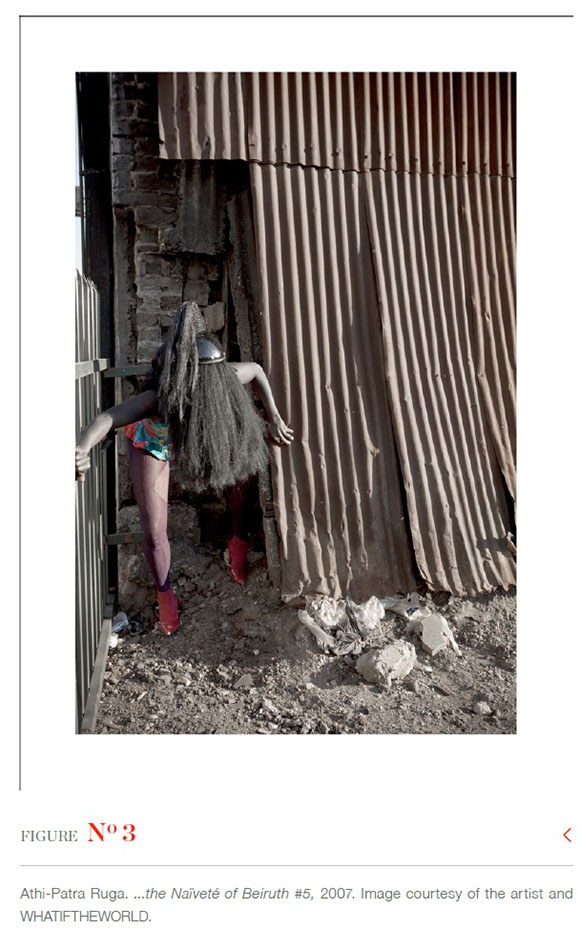

In the last image in the series, ...the Naïveté of Beiruth 5 (figure 3), I see the same fear I witnessed in ...the Naïveté of Beiruth 1 (figure 2). Here, having completed the narrative loop of the series, starting and ending with anxiety, fear and terror, Beiruth is photographed emerging from the darkness of a corrugated iron inner-city nook near the Johannesburg Central Police Station. Stepping around building rubble and other waste, the darkened scene is reminiscent of a survivor emerging from a shelter in the aftermath of a war or from a shack within an informal settlement - itself a site of political and social violence in the South African context (see Bonnin 2004). Tentatively stepping into the light and into possible harm's way, Beiruth is almost doubled over with her head lowered and in line with her abdomen as she extends her body around the corner to, in my reading, check for danger. Her dextral arm extended in front of her, she clasps the bars of a spiked fence as if for security and support, the other hand clutches the structure's iron sheeting as if unsure whether to leave the relatively safety of the darkness. I read this image as one of hesitancy, fear and anxiety. What is unseen and unknown cannot be punished, cannot be mistreated. Much like those queer subjects who "passed" as straight under the apartheid regime were not necessarily subject to the same violence as other members of the queer community. It is an image that speaks of the futility and cyclic nature of the struggle for freedom and recognition. It is a terrifying indictment on the failure of the democratic process, the failure of the state to keep its own legislative promises and protect some of its most vulnerable citizens.

Writing in the post-apartheid present, police abuse and misconduct targeted at women and queer subjects continues. Headlines regarding police brutality and violence are common occurrences in the mainstream media and seemingly underscore the sustained use of apartheid-era practices: 'Deaths from police brutality on the rise - report' (Mkhwanazi 2017:[sp]), 'Police Brutality On Rise In South Africa: Officers Accused Of Killing, Raping Citizens' (Morrison 2015:[sp]), 'South Africa reports of police brutality more than tripled in the last decade' (Smith 2013:[sp]), 'Apartheid culture of police brutality still alive today' (Raphaely 2014:[sp]), 'No end in sight for police brutality in South Africa' (Malala 2013:[sp]), and 'Policemen arrested for torturing to death a suspect in custody' (Lewis 2015:[sp]) reveals the perceived limits of post-1994 police transformation and the continued presence of repressive police strategies. However, while this 'surge in state violence appears to bear disturbing continuities with the country's colonial and apartheid past, in which white supremacy was maintained through the barrel of the police gun' (McMichael 2016:4), these headlines only provide a limited snapshot into police abuse and misconduct and it is important to note that, while violence and abuses of power do take place, the manner and nature of these incidents has changed since South Africa's transition to democracy. Under apartheid there were regular police raids on queer(-friendly) bars, nightclubs, and private residences. However, under democracy, there is seemingly no evidence of police raids on sites purely because they are queer-friendly or instances where police officers photographed queer subjects and threaten to expose their identity in the mainstream media.

This change can be seen as stemming from a variety of factors including extensive legislative reform which decriminalised "deviant" sexualities and granted queer subjects a number of socio-economic and political rights, poor vetting during recruitment means those with histories of criminal activity are recruited into the police (Grobler & Prinsloo 2012), transformation of the SAPS's racial and gender profile which assisted in shifting institutional culture (Newham et al. 2006),24 and the changing political landscape that often pits South Africa's most disenfranchised communities against the SAPS in various unrest incidents including service delivery protests, industrial action and social movements (Mkhize 2015; McMichael 2016).

While police brutality is generally accepted to be a problem in post-1994 South Africa there are 'numerous problems with measuring police brutality' (Bruce 2001:[sp]). These include 'low visibility in terms of the presence of witnesses', shifting definitions of "brutality", limited distinction between incidents by on- and off-duty officers, problematic systems of reporting and investigating incidents, and, importantly, limited nuance in the taxonomies of crimes ('If one understands brutality as unlawful violence by the police ... should one include charges of rape against members of a police service within the category?' (Bruce 2001:[sp]). For example, the police watchdog, the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID), 2017/18 Annual Report notes there were 5 524 reported cases of violence, corruption and misconduct perpetrated by the SAPS that year. Of these there were 3 598 cases of assault, 216 torture cases (an increase of 25% from the previous reporting period), 201 cases resulting in death in police custody, and 102 cases of rape by a police officer. These statistics, as unsettling as they are, are misleading: 201 deaths in police custody does not necessarily mean 201 deaths resulting from police brutality. These data, as with the broader South Africa, do not allow for a robust and accurate comparative analysis of the extent of the police misconduct in terms of violence targeted at women and queer subjects. Significantly, these data are not nuanced enough to make informed conclusions and only represent instances reported to the IPID and even then, 'few allegations are thoroughly investigated and prosecutions and convictions of implicated officials are rare' (Raphaely 2014:[sp]).25

In the queer context, despite South Africa's liberal constitution, queer persons are still othered and subject to various acts of violence at the hands of the new SAPS. This continued violence and brutality, despite - and arguably in spite of - South Africa's liberal constitution, bring to the fore complex and uncomfortable questions about whether South Africa's law enforcement can be anything other than a violent force spurred on by a deeper, residual colonial and apartheid-era societal conservatism. These questions are further complicated by the recent remilitarisation of the SAPS through the reconceptualisation of the apparatus as a paramilitary force and the reintroduction of military ranks in 2010 (McMichael 2016; Steinberg 2011). While it is difficult to quantitatively determine the rate and extent of changes in police behavior, this is not to say that all forms of abuse and misconduct perpetrated by the police now are the same as they were pre-1994.

There is little reliable statistical evidence to demonstrate police brutality and misconduct targeted directly at the queer community but, in its absence, anecdotal and oral history evidence can be drawn upon to full comprehend the interaction between the SAPS and the queer community. Amnesty International (2013) recounts several instances of police brutality against queer subjects in post-1994 South Africa. The report reproduces personal testimonies from members of the queer community revealing the police to be perpetrators of both first-hand violence and secondary victimisation as well as misconduct arguing that 'police officers discriminate against LGBTI individuals, even as the LGBTI individuals seek protection from abuse in their communities' (Amnesty International 2013:29):

Following KwaThema Pride (Ekurhuleni Pride) in September 2010, a woman walking home from the pride was harassed by the police. And there were two incidents following Soweto Pride. One woman, called Maki, was pulled over by the police. A female cop threw her in the back of her van, and drove her around for hours. The cop said a lot of derogatory stuff about gay people. After the last pride in Soweto (September, 2009), seven lesbians were arrested in KFC and were abused in police custody. One of the women involved, P, went on a TV show on ETV to talk about the incident. One year later, the cops raided a party where she was at, and used pepper spray on everyone, including people who were asleep. There were four vans and 20 police. They said there had been a noise complaint. They lined people up outside, and said 'fucking lesbians, where's your ETV now? Who's gonna save you now?' 11 people were taken into custody, but all got released. The court case was on the following Monday, and the prosecutor threw the case out of court (Amnesty International 2013:28).

Within the same report, Nonhlanhla Mkhize, Director of the Durban Gay and Lesbian Community and Health Centre, shares insights into cases of police abuse her organisation has dealt with including wrongful arrests and sexual harassment by police officers as well as the police's inappropriate response to the homophobic attack against a gay-identifying student at an undisclosed university residence. Mkhize's account includes her own experience of gender-based violence where her assailant publicly 'shouted gender insensitive and homophobic remarks at her' (Amnesty International 2013:28) whilst physically attacking her. More significantly, Mkhize notes the subsequent 'inadequate' (Amnesty International 2013:28) response of the police who 'just stood there. When called to intervene they told us to wait for the police services we had called to come' (Amnesty International 2013:28). These accounts are corroborated by findings reported by Mills, Shahrokh, Wheeler, Black, Cornelius & van den Heever (2015:24) who note that 'the present actions of the post-apartheid state are failing to adequately address inequalities through the judicial system' citing victim-blaming and 'institutional discrimination' within the police as key factors behind crimes not being reported or investigated. One testimony the authors received from a contributor at a queer support center in Khayelitsha, an informal settlement approximately 25km south-east of Cape Town, elaborates:

[When LGBTQI] people go to the police station, [they] are then subjected to secondary rape by the police themselves. They call others and laugh at the person, and many people feel they are not going to report a case. In some instances, when someone goes to report a case, this is what happens at the police station. The perpetrator won't be arrested, or the police won't investigate (Mills et al 2015:24).

While many survivors of hate crimes and gender-based violence do not report these incidents to the police, in some instances - such as rape - reporting these crimes to the police is legally required so survivors can receive the necessary medical treatment. In these cases, and for queer subjects who insist the justice system bear witness to their daily lived reality in the hope of seeking redress, engagement with the police is often coloured by inefficiency, incompetence and corruption. Nath (2011:46) analyses the 'experiences of those individuals ... who did go to the police' examining eighteen distinct testimonies - spanning more than a decade of democratic rule - underscoring the breadth of the SAPS's administrative terrorism, abuse (verbal, physical and psychological), cronyism, and corruption to the extent that the police seem 'more preoccupied with how lesbians have sex than with securing justice' (Nath 2011:47). Such misconduct and abuse - the legacy of South Africa's long history of structural violence under colonialism and apartheid - has resulted in an 'overwhelming lack of faith in law enforcement and in the criminal justice system' (Nath 2011:54). As Holland-Muter (2012:2) concludes, 'violence against LGBTI communities has been a feature of life before, during and after the transition to democracy' (Holland-Muter 2012:2) and, given the SAPS management's apparent disregard for the findings and recommendations of oversight bodies - of which 'South Africa has more ... than most nations' (Sammonds 2000:[sp]), the broader targeting and oppression of queer subjects does not appear to be changing.

CODA

While my reading of .the Naïveté of Beiruth 5 (Figure 3) is one of darkness and trepidation, it would be amiss to not acknowledge the thread of hope and bravery that exists. In the midst of the violence - with literal shrapnel encircling - Beiruth emerges from the relative safety of the shack to put herself in potential harm's way. It is, in my reading, akin to 'coming out' as queer and facing the repercussions thereof. On some level, Beiruth believes - perhaps, as per the series title, naively - in the possibility of change, in the possibility of understanding, acceptance and inclusion.

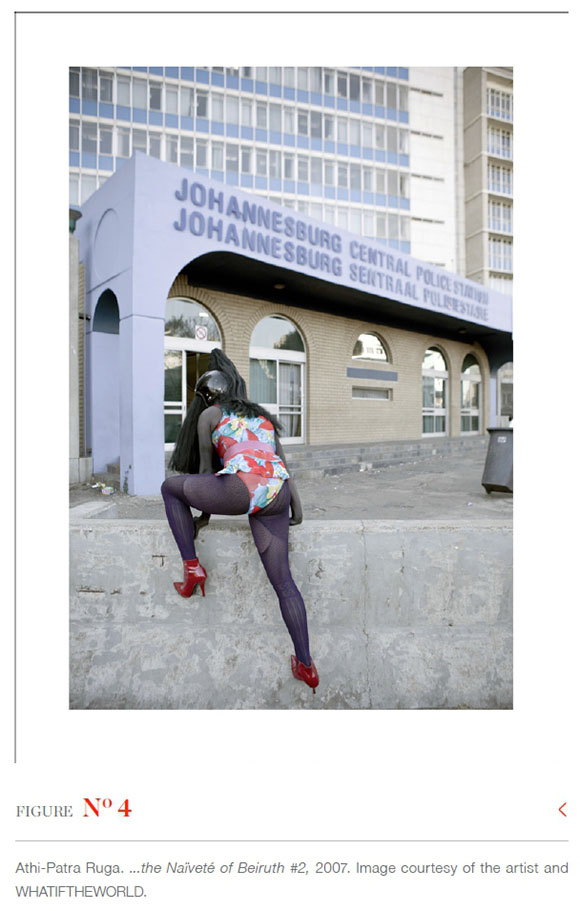

I read this same thread in ... the Naïveté of Beiruth 2 (Figure 4). Here, Beiruth is photographed attempting to scale a wall outside the main entrance to the Johannesburg Central Police Station. Captured mid-mount, she defies the wall restricting her access to the space, controlling her movement and dictating her navigation through the area. In bravely maneuvering through the space in her own desired way, unafraid of the fortified building filled with (possibly armed but always dangerous) police, Beiruth pushes back against the system that deems her unwanted and expendable to reclaim her agency and assert her value.

Through this image, I recall the intoxicating and apocryphal stories popularly circulated about the 1979 police swoop at The New Mandy's nightclub where the diverse mix of clientele - ranging from drag queens to Afrikaans businessmen - fought back against the unapologetically violent police. The tales tell of bloody police officers with stiletto-inflicted cranial trauma ... Beiruth's heels, already a deep and glossy crimson and ripe with Freudian phallic symbolism, could make notable penetrating injuries. In this light, the oversize wig and protective helmet have transformed into a galea, a combat headdress with eccentric plumage signifying her as somebody of superiority and power; the wide belt, no longer clearly accentuating Beiruth's hour-glass physique, visually resonates with the appearance of a military-issue riggers belt or possibly a Sam Browne.26 She has transformed into a warrior in Helen Moffett's militia fighting in South Africa's 'unacknowledged gender civil war' (Moffett 2006:130).

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to my supervisors Kylie Thomas and Harry Garuba for their support and supervision of my dissertation from which this paper is derived. I am also grateful to Rory du Plessis and Brenna Munro who, in their capacity as external examiners, provided constructive feedback and comments on the dissertation. A big thank you to Linda Chernis from Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA) who assisted in my archival research. Thank you to Image & Text and the two anonymous reviewers who provided constructive criticism on earlier renditions of this paper. I also owe thanks to the UCT Merit Scholarship, which provided financial assistance.

Notes

1 . Despite the on-going expansion of acronyms like LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/ questioning, intersex, and asexual, while the "+" denotes other diverse identities like non-binary, two spirit and pansexual) and LGBTQQIP2SAA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, queer, intersex, pansexual, two-spirit, androgynous, and asexual) to include increasingly recognised and diverse identities, I deploy the term 'queer' throughout this article as an umbrella label for all counter-normative performances of sexuality and gender. It is important to note that, under apartheid, only gay and lesbian sexual identities were recognised in South Africa - most blatantly evidenced by the names of NGOs fighting for equality and social support across the country: Gay Association of South Africa (GASA), Organisation of Lesbian and Gay Activists (OLGA) and the Gay and Lesbian Association (GALA). This is not to say that alternative forms of sex and gender identity were not present under apartheid and my use of 'queer' refers to all forms of counter-normative sex and gender expression regardless of their temporal or political recognition. For more information on the usefulness of the above acronyms and the value of revising and applying social theory from a queer perspective, see Warner (2011).

2 . On 13 September 2018, Ruga posted to Facebook: '10 years ago, my 3 Avatar, The Beiruth, tested her autonomous body against a massive structure like the ever-glamorous Universal Church of athe [sic] Christ. The pronouns 'her/she' are also used in Beiruth-centric authorised texts about Ruga published by Whatiftheworld Gallery (see Siegenthaler 2013). Consequently, I use the pronouns "her/ she" in this text.

3 . Throwing or pushing detainees out of the upper windows of John Vorster Square was 'not unusual practice of the time' (Herwitz 2005:532) notes social theorist Daniel Herwitz in his theorisation around Ahmed Timol's memorialisation and the legacy of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Significantly, on 12 October 2017, High Court Judge Billy Mothle ruled that 'Timol did not jump out of the window of room 1026 but was either pushed out of the window or from the roof of John Vorster Square. Thus, Timol did not commit suicide but was murdered' (EWN 2017). Like Timol's court case, amaranthine calls for investigations into apartheid-era atrocities and mysteries are themselves exemplary of how the past continues to play out in the post-apartheid present.

4 . With South Africa's transition to democracy and the adoption of one of the most progressive constitutions in the world, South Africa was politically rebranded as a progressive and inclusive society, transforming it into what Archbishop Desmond Tutu, on the eve of South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994, termed the "Rainbow Nation". The Rainbow Nation was Tutu's utopian belief that the new national corpus would transcend the boundaries of, inter alia, race, gender and sexuality and lead South Africa into the future as an enlightened and unified nation. The daily lived reality of democratic South Africa, however, is starkly different to the dream.

5 . Ruga was not alone in this call to action: news of Ngcukana's ordeal sparked national outrage and resulted in a protest march through the streets of Johannesburg with many protesters wearing miniskirts in active defiance of the policing of women's bodies. Since 2011, Johannesburg has hosted an annual SlutWalk, a protest march against rape culture and rejecting the notion 'that a women [sic] can be blamed for rape if she was wearing a miniskirt' (SlutWalk 2011:[sp]).

6 . This 'equality clause' legally prevents discrimination based on 'race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language, and birth'. This clause has become a key legislative took for broadening ideological perspectives on egalitarianism and was at the center of a number of legal victories for queer subjects including the Labour Relations Act (Act 66 of 1995), which made it illegal to dismiss employees on the grounds of sexuality, the Employment Equity Act (Act 55 of 1998), which defined 'family responsibility' to include queer families, amendments to the Child Care Act and the Guardianship Act now permit same-sex couples to adopt children, and the Civil Union Act (Act 17 of 2006), that legalised same-sex marriage. The inclusion of the term "sexual orientation" in the equality clause is the result of the successful lobbying efforts of many parties including the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality(NCGLE), for a history see Cock (2003).

7 . I am inclined to agree with Hesselink and Häefele (2015:317) who define 'police brutality' as the 'excessive use of force that surpasses police actions that are necessary to achieve a lawful police purpose'. As such, police brutality is the deliberate unlawful use of force - such assult and torture - on members of the public. This is not to say that the police cannot or should not use force. Indeed, much police work is in situations where force may be necessary and lawfully justified and 'police brutality' in this regard is the '(unlawful) abuse of the capacity to use force' (Bruce 2002:[sp]; emphasis in original).

8 . More broadly, the camera played an important yet antagonistic role under apartheid as both an important bureaucratic apparatus of bio-political control by enabling the enforcement of racial segregation but also as a "liberatory and political tool" (Weinberg 2018:16) of the resistance movement in its ability to make visible the hidden realities of life under apartheid (Hayes 2007). In the hands of the government and its subsidiary agencies, the camera - particularly Polaroid's patented instant imaging technology - provided a simple and efficient means of documenting black South Africans for, inter alia, their mine identity cards and dompas (a type of passbook; literally translated as 'stupid pass') which, under the Natives (Abolition of Passes and Co-ordination of Documents) Act (Act 67 of 1952), all black South Africans were legally forced to carry at all times - both documents included a small black and white portrait of the carrier. Conversely, South Africa was also home to many photographers and anti-apartheid activists who dedicated themselves to documenting and exposing the atrocities of the apartheid dispensation (Hayes 2007). Photographers like Mabel Cetu (1910-1990), Alfred Kumalo (1930- 2012), David Goldblatt (1930-2018), Sam Nzima (1934-2018), Peter Magubane (b. 1938) and Ernest Cole (1940-1990) as well as photographic collectives like the Bang Bang Club and Afrapix played critical rolls in combating the apartheid governments extensive propaganda campaign to sell apartheid both locally and abroad (Hayes 2011).

9 . 'Site-specificity', notes Kaye (2000:25), 'is linked to the incursion of "surrounding" space, "literal" space or "real" space into the viewer's experience of the artwork'. Ultimately, Kaye argues that 'the location, in the reading of an image, object, or event, its positioning in relation to political, aesthetic, geographical, institutional or other discourses, all inform what "it" can be said to be' (Kaye 2000:1).

10 . It is with great trepidation that I use the popular nomenclature 'corrective rape' as I agree with Thomas (2013) and Lahiri (2011) who argue that the term asserts a normative conception of gender and sexuality which perpetuates the erroneous belief that these are choices that can be consciously (un-)made and attempts to rationalise and justify this violence within a broader ideology. Moreover, as Lahiri (2011:123) notes, the term's usage has become wrapped in thinly concealed racist discourses which expose lingering cultural beliefs held against 'African men'.

11 . See, for example, Coq/Cock (2013) and Chandelier (2001).

12 . I use the term 'queercide' to refer to the systematic killing and destruction of the counter-normative community. I use it instead of the arguably more common terms 'gendercide' and 'homocaust' to ensure our understanding of the problem extends beyond rape and gender-based violence within a heteronormative patriarchy to include offenses against all counter-normative individuals. The term also holds significance in that Queerside was a photographic and video project created by visual activist Zanele Muholi 'to denounce and record hate crimes and atrocities committed against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people' (Stevenson Gallery 2011 :[sp]). In April 2012, Muholi's apartment was broken into and only her hard drives and camera equipment were stolen while other valuables were left untouched. As Thomas (2013) notes, 'If the theft was directed at keeping her work from being exhibited, it operates as an act of symbolic silencing' (Thomas 2013:2).

13 . As noted in the ...of Bugchasers and Watussi Faghags exhibition rationale, '"bug-chasing" (the act of contracting the H.I. virus intentionally) - with its seemingly altruistic motivation; while also referring to the history of the 'Watussi', a colonial mis-pronouncement of the Tutsi people of the Burundi-Ruanda nation' (Ruga as quoted in Stevenson Gallery 2008: [sp]). For more of Ruga's work around the Watussi myth and his critical engagement with renowned South African expressionist painter Irma Stern's ethnographic work on the Watussi, see his Pixilated Arcadia tapestry series specifically Watussi Rooi Kombers (after Irma Stern 1943) (2008) and Watussi Queen (after Irma Stern 1946) (2008).

14 . Vorster had previously held the post of Minister of Justice (1961-1966) and would later go on to become the fourth President of South Africa (1978-1979). In a 1972 poem, entitled 'Brief uit die vreemde aan slagter (Letter from Foreign Parts to Butcher), with the subtitle 'For Balthazar', South African poet Breyten Breytenbach describes in unsettling and gruesome detail the human rights violations that lead to the torture and murder of detainees at John Vorster Square and implies that Vorster himself is to be held accountable for these deaths. Similarly, Michael Cawood Green's 'John Vorster Square' (1979) speaks of detainees 'singing ... songs of torture and suicide and exits' from their lofty cells concluding with the detainees - 'both dead and alive' - engaging Vorster directly: 'John Vorster are you proud to have that building bear your name?' (Green 1997:147).

15 . In terms of medical experiments, the South African Defence Force (SADF) - itself a glorified symbol of heterosexual masculinity within Afrikaans culture - 'partook in human rights abuses by utilising aversion therapy, hormone therapy, sex-change operations and barbiturates in the 1970s and 1980s on young white homosexual men as a means to "cure" them of their homosexual "disease"' (Jones 2008:398). South Africa had forced conscription for white males between 1957-1993 and thus constitutes a way in which the state systematically controlled queer subjects and prided heteronormativity above all else. For more information on medical experiments on queer subjects by the SADF - known as The Aversion Project - see van Zyl, Reid, Hoad and Martin (1999).

16 . The explanations police gave for deaths in detention were so ridiculous that they became easy fodder for artists and writers. See, for example, Chris van Wyk's poem 'In Detenion' which begins with standard responses to death in detention: 'He fell from the ninth floor/ He hanged himself/ He slipped on a piece of soap while washing' eventually devolving into 'He fell from a piece of soap while slipping/ He hung from the ninth floor/ He washed from the ninth floor while slipping/ He hung from a piece of soap while washing' thereby showing the absurdity of the SAP's response to the deaths.

17 . Soweto is a syllabic abbreviation for "South Western Townships" and comprises approximately 30 smaller townships. In terms of gender-based violence under apartheid, Soweto was home to a particularly violent brand: Jackrolling. The term originally referred to the Jackrollers - a gang of predominantly youth-members which operated in Soweto in the late 1980s - who would forcefully abduct and gang rape women in public including 'shebeens (informal township bars), picnic spots, schools, nightclubs and in the streets' (Vogelman & Lewis 1993:[sp]). The term is now generally applied to describe abduction and rape of women in general. It is not clear to what extent this term is used in Soweto post-1994. For more, see Mokwena (1991).

18 . Bentham conceived of the Panopticon as a prison model whereby inmates would be aware on an omnipresent disciplinary authority even if individuals were unaware of when they were personally being surveyed. In Michael Foucault's critical text Discipline and Punish (1975) his discussion of Bentham's Panopticon highlights that allowing a punitive or correctional institution to create a 'state of conscious and permanent visibility that ensures the automatic functioning of power' (Foucault 1977:201) marks the point at which architecture can be used as a means of control and psychological manipulation. By becoming strategically 'caught up in a power situation' (Foucault 1977:201), inmates would thus self-regulated their behavior. Moreover, Bentham conceived of his prison as being both punitive and preventative in nature and suggested that his Panopticon be situated near or visible from the center of the city as a constant reminder of the bitter fruits of criminal activity thereby encouraging the citizens - like the prisoners - to become 'the principle of [their] own subjection' (Foucault 1977:203). Thus, the Panopticon would continuously reassert the power dynamic and subject both inmates and citizens to similar auto-regulatory behaviors. John Vorster Square's architectural design and premeditated positioning works in a similar manner to promote the silencing and deterring of political unrest in Johannesburg's Central Business District.

19 . The 'Bucharest syndrome' refers to the 're-appropriation and re-use of buildings from a previous regime' (Leach 2002:81). Leach uses the example of the successful transformation of former-dictator Nicolae Ceausescu's grand palace into Romania's House of Parliament and an international conference center considered to be the 'popular center of Bucharest' (Leach 2002:81). This is juxtaposed with the 'Berlin Wall Syndrome' which refers to the 'almost complete eradication of the traces of the Iron Curtain around Berlin' (Leach 2002:81).

20 . The emphasis on police-community partnerships was further promoted in both the National Crime Prevention Strategy (1996) and the White Paper on Safety and Security (1998).

21 . The term 'Priscilla' comes from a South African gay argot, Gayle. Gayle uses the standard foundation of the English and Afrikaans language but replaces selected words with alternatives - a overwhelming majority of which are women's names. Under apartheid, Gayle, used primarily in white gay social contexts, would allow homosexual men to conceal their identity in a time of criminal punishment, identify fellow oppresses without exposing each other to harm, and gave speakers a sense of solidarity and camaraderie. For more on the history of Gayle and a concise dictionary, see Cage (2013).

22 . See, for example, the Rand Daily Mail's coverage of the 1966 Forest Town Raid, which - in an article entitled 'Five Pay "Men Only" Party Fines' - notes how 'to maintain their disguise police had to conform by dancing with men at the party' (Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action AM2580).

23 . Interestingly, despite opening in 1998, Hot House, South Africa's premier gay cruising bathhouse advertising itself on its company website as a 'European style steam bath', employs similar strategic architectural and structural barriers which would delay a raid, including: access control at two doors, ascending two flights of stairs, navigating a lobby and a locker room all before accessing the sauna proper. Thus, Gallie and Rafael's 'prison-houses of desire' (Gallie & Rafael 1994:134) concept seemingly continues in the post-apartheid present. For more see, www.hothouse.co.za. The tactical (dis)advantages of these labyrinthine structures and their regulation of interpersonal encounters were key tropes in Tom Frederic's short film Sauna the dead: a fairy tale (2016) in which the establishment's perceived security and safety are subverted during a zombie outbreak within the building.

24 . Under apartheid, the SAP overwhelmingly consisted of Afrikaans white men with the limited number of black officers seen as 'naturally inferior to the white officers' (Newham et al. 2006:15) - itself demonstrative of the embodied racial hierarchy within the police and the country at large. The SAP, however, went through several recruitment phases due to increased unrest and the need for total control of the black population with various degrees of racial inclusivity (Newham et al. 2006) and, as Rauch (2000) notes, by the time of the 1994 election, South Africa's 11 military and paramilitary units - of which the SAP was one with approximately 112 000 members (Rauch 2000:[sp] - were 'pretty representative of the racial makeup of the South African population - 64% of the combined personnel of the police organisations was black. Even the SAP alone (which contributed 80% of the personnel to the total), was not as dramatically unrepresentative as many observers had believed - 55% of its members were black' (Rauch 2000:[sp]). The problem, however, exists in the racialised hierarchy in which 'whites were over-represented in the senior ranks of the organisation, while blacks were over-represented in the lower ranks' (Newham et al. 2006:18). Today, however, the police system is seen as more diverse and representative but, thanks to the lingering dominance of white males in senior ranks, the SAPS still has 'some way to go before the organisation achieves all its equity targets with regards to race and gender' (Newham et al. 2006:5).

25 . The 2017/18 IPID report notes that while there was a total of 99 criminal convictions over the reporting period, there were zero convictions for torture (as well as zero disciplinary convictions), 33 convictions for assault and one conviction for a death in police custody. Rademeyer and Wilkinson (2016:[sp]) argues that these low arrest and conviction rates may breed thoughts of impunity and encourage officers to participate in criminal behavior.

26 . The Sam Browne belt has adopted particular significance for queer subjects within the BDSM (bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, sadism and masochism) subculture. The appropriation of accessories or garments closely linked with heterosexual masculinity allowed for marginalised groups to create powerful counter-narratives where 'power is transgressed, destabilized, negotiated and challenged' (Geczy & Karaminas 2013:112). In this way queer subjects reclaim their agency and personhood in a social context where they are marginalised and disenfranchised. Other examples include leather chaps and cowboy boots.

REFERENCES

Abrahams, N, Mathews, S, Martin, L & Jewkes, R. 2013. Intimate partner femicide in South Africa in 1999 and 2009. PLoS Medicine 10(4). [ Links ]