Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.33 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a10

ARTICLES

Sonic fingerprints: on the situated use of voice in performative interventions by Donna Kukama, Lerato Shadi and Mbali Khoza

Katja Gentric

Postdoctoral Fellow, Art History and Image Studies Department, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. Chercheur Associé au Centre Georges Chevrier, UMR 7366 - CNRS uB, France. ge.katja@yahoo.fr

ABSTRACT

This article focuses on sonic elements in performative interventions by three South African artists: Donna Kukama's, Chapter F: The Free School for Art and All Fings Necessary (Until Fees fall) (2016), Lerato Shadi's Matsogo (2013) and Mbali Khoza's What difference does it make who is speaking? (2014). By observing the details of each artist's use of voice and its 'situatedness' (Goniwe; Mohoto-wa Thaluki), I have positioned the works within the discipline of sound studies. Beyond the sites chosen for the interventions, their 'situatedness' refers to the cultural aspects informing them, including language specificity and the diachronical re-actualitsations of struggle-songs, traditional tales and newspaper journalism. The locations are a hole or negative space in the pavement on Johannesburg's Beyers Naudé Square, a discarded newspaper page showing the foreign index, and Makhanda Eastern Star Museum. I refer here to sound, time and matter as 'fingerprint' (Cassin; Dolar), arguing for each one's right to be heard according to his/her personal means of expression, and that 'accentedness' (Coetzee) and situatedness should not lead to the assumption of the existence of an impenetrable 'epistemic barrier' (Maharaj). The triad combining use of language (individuated speech), bodily voice, and the time-factor involved allows for a sonic fingerprint to evolve.

Keywords: sound studies; voice; situatedness; accentedness; untranslatables; artistic intervention.

From the most intimate whimper or whisper, to the amplified speech of a politician at a rally, or the roaring outcry of a crowd,1 a voice is a versatile tool. Voice is also an instrument used by artists, where beyond vocal forms of cultural expression like opera, theatre or cinema, it may be part of process-driven art practices. This article focuses on the sonic elements in the performative interventions of the South African artists Donna Kukama, Lerato Shadi and Mbali Khoza.

To introduce the central issues addressed by research on the sonic element in contemporary art practices, two apparently random examples may serve as a preface to this paper: Bruce Nauman's much-cited Lip Sync (1969)2 and Roman Opalka's series 1 - ∞ (1965-2011). Both grew out of the experimental art of the 1960s. Nauman's work can be situated further within the context art of the 1970's in the United States of America, while Roman Opalka's concept stems from a life evolving between France and Poland.

Bruce Nauman's Lip Sync (1969) systematically explores the technical vectors and creative potential of video as a tool to interrogate the discrepancies between sight and hearing. In this work, the time-lag and logical shifts between what is seen and what is heard create awareness of the medium. Similarly, in Roman Opalka's series 1 - °° (1965-2011), the more widely known visual elements - his paintings of white numbers on a dark grey ground - are accompanied by the less frequently mentioned soundtrack of the artist's recorded voice counting out each number as he painted it (Opalka [sa]). Over a period of more than 40 years, Opalka progressively and gradually lightened the black paint with white, which eventually resulted in the effacement of the contrast between the ground and the painted numbers (Fréchuret 2016:153-162). At the same time, a forceful bodily dimension was added to these visual and vocal recordings of the passage of time by the sound of his ageing voice and his particular way of pronouncing the numbers, which he chose to count out in Polish.

Both of these works reflect on how paradoxical discrepancies arise regardless of the essential synergy between sight and hearing, and the way the visual and the sonic inform3 each other within the constellation of each artist's situation. Inevitably, any intervention on matter will produce sound, and any occurrence of sound is inseparable from matter (Neumark 2017:1-30). The use of voice and other sonic elements acknowledge that an action and the sound it generates are one.

To fine-tune this general approach to the sonic aspects of artistic practices within the South African context, I single out three specific performative interventions: Donna Kukama's, Chapter F: The Free School for Art and All Fings Necessary (Until Fees fall) (2016), Lerato Shadi's Matsogo (2013) and Mbali Khoza's What difference does it make who is speaking? (2014). Each work is performed by the individual artist. Two happen in the presence of an audience, while the third is filmed to be viewed as a video. By closely observing the details of each artist's use of voice and the material aspects of the sonic elements in each performed action, I have positioned the works within the discipline of sound studies, a field of research accommodating occurrences of sound in the widest sense.4

In each intervention, the use of speech and voice differs widely, including the singing voice, the speaking voice, or a half-singing variation of speech. Kukama pits her voice against that of another, Shadi performs voices in polylogue, and Khoza enacts the silent recognition of another's voice. Speech renders a further layer of meaning by the particularities of language usage. My analysis of voice and language has developed in parallel with therapeutic approaches through the use of voice (as in the work of Ulrike Sowodniok 2013:7), practice-based approaches to media studies (as in the work of Norie Neumark 2017), an emphasis on the performative aspect of any occurrence of voice and of language (referring to Doris Kolesch 2006:40-64), and the philosophy of language (via the work of Barbara Cassin 2004 and 2016). The particularities of speech within a decolonial context are further situated with reference to Carli Coetzee (2013) and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (1988:271-313).

Kukama's, Shadi's and Khoza's interventions are interconnected with a complex web of socio-political references, namely the historical perspectives of recent events in South Africa. These include internal South African politics, South Africa's position in a multi-national economic system dominated by the legacy of colonial intervention in Africa, and pan-African informal relations/friendships. These social and historical dimensions constitute what may be referred to as the 'situatedness' of these performances, a term borrowed from Thembinkosi Goniwe (2006:91) when he identified situatedness as a crucial aspect of South African art, and drew attention to the specific problems which sustain these practices.5 More recently, the feminist context the expression was first used in is emphatically claimed in reminders as to the essential situatedness of any form of knowledge or imagination (Lieketso Dee Mohoto-wa Thaluki 2019:107-123).

To position the particularities of sound and voice - meaning their material and temporal aspects in constellation - I introduce the image of the 'fingerprint' from a reading by the language philosopher and philologer Barbara Cassin. It would appear that the process of making an imprint calls upon a material/temporal constellation similar to the one I have described in the use of voice.

Fingerprints and situatedness

Cassin (2016:24) uses the expression 'les empreintes digitales des langues' ('the fingerprints of languages') to refer to 'untranslatables',6 as her approach consists of thinking philosophy through languages (Cassin 2004:xvii) or in-between languages (Wismann 2012). Through her research,7 Cassin (2004:xvii) shows how untranslatables provide the philosopher with an opportunity to access the particularities of thought patterns that run deeply through language-cultures, and to grasp aspects of language within the dynamics of a dialectical situation. Her use of the fingerprint metaphor suggests that the phenomenon of the untranslatable remains recognisable even within successive layers of re-translation, and provides evidence of our own presence (meaning the speaker or the listener - in short, us, the users of language), the fact of our having been there, of our having left a trace.

To highlight the disruption of smooth translation is an act of resistance to the traditional hegemonic approach described by Lawrence Venuti (1995) as 'the translator's invisibility'. By drawing attention to the hypocritical artificialness and the political violence perpetrated through the determination to make the process of translation invisible, Venuti's line of thought is affiliated to Cassin's praise of the (un)translatable. Both point to an irksome detail within the allegedly unperturbed and unproblematic smoothness of the process of translation: a fingerprint.

The 'imprint' has also received attention in the field of semiology of the arts, for example, in the exhibition l'Empreinte (1997) curated by the philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman. He considered the imprint or trace to be a 'theoretical paradigm' (Didi-Huberman 2008:12), where it symbolises singularity (as each imprint is different). While Didi-Huberman remarked on the immediacy of the imprint (proof of direct contact), he also observed that it becomes part of a process: the moment an imprint appears then instantly the moment of contact is over. Thus, from Didi-Huberman's perspective, the imprint or trace is a form of 'anachronism'.

A fingerprint comes about when touch meets material substrate. In relation to the constellation of language and voice, three vectors must coincide to allow for resonation: sound, which needs matter to pass on the vibrations (air for example); time, to develop a reverberation or sound wave; and a form of receptor (mechanical or organic), to receive and decode them. Following this logic, then sound - like the anachronistic imprint - must be bound to time constantly, carrying always an intimation of its historicity. In other words, it can be considered to have an anachronistic aspect. Furthermore, when sound is recorded, it produces a tangible, material trace that can be captured and then reproduced by a sound-producing device, for example the needle of a phonograph or a digital laser beam.

For living beings, the emitting and receiving of sound implies the presence of a bodily structure or embodiedness. The praxis-based approach to the sounding voice developed by Sowodniok (2013:8,14) shows the extent to which the entire body resounds with each use of voice, especially through the nerve-ends of the gustative and tactile senses, which are closely connected to all parts of the vocal cords and produce the senses of taste and touch inside the body (Sowodniok 2013:87-121). Voice, born of breath, is simultaneously internal as the body vibrates with it and external in the public space. After Kolesch (2006:47), Sowodniok (2013:13) further points out that the voice becomes the tactile and aural trace of our body on two levels: experienced both in a bodily sense, and as a product of thought. This can result in individuated speech.

Voice as a combined tactile and aural trace of our body and thought can be found in the writings8 of Mladen Dolar (2006:22), who speaks of individuality by referring to the voice as a fingerprint,9 'We can almost unfailingly identify a person by the voice, the particular individual timbre, resonance, pitch, cadence, melody, the peculiar way of pronouncing certain sounds. The voice is like a fingerprint, instantly recognizable and identifiable.' From the outset, Dolar (2006:13) introduced the notion of 'intermediacy', in that voice manifests between the inner workings of the mind and the outside world, intimately linked to the body but reproducible through technology. He maintained that we are social beings by and through voice, stating, 'Voices are the very texture of the social, as well as the intimate kernel of subjectivity' (Dolar 2006:14) and, 'There is no voice without the other' (Dolar 2006:27).

Similarly, in her seminal essay Can the subaltern speak? (1988:271-313), Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak situates vocal expression as a prerequisite for recognition. She shows how the specific conditions around the sonic presence of an individual are substantiated by the voice, which signifies a contextual coherence and pertinence. Within Spivak's argument, the recognition of the subaltern in a male-dominated, occident-dominated, 'global' society culminates in the question: 'with what voice-consciousness can the subaltern speak?' (Spivak 1988:285).

In this article, I aim to describe the line of thought that leads from the particularities of each language to the recognition of each speaker's individuated use of language, with reference to the work of Carli Coetzee in Accented futures, language activism and the ending of apartheid (2013). The intention underpinning Coetzee's (2013:x) activism lies in her choice 'not to be ignorant'. Her book is a bid 'against translation' (Coetzee 2013:1-6), and for what she terms 'accentedness' (Coetzee 2013:7-16) or 'accented thinking'. By this she means the way an individual speaks and thinks with his/her own specific accent, bearing witness to where he/she speaks from, his/her 'address' (Coetzee 2013:79-95). Coetzee studies difference, disagreement and misunderstanding 'as possible sites for learning and transformation' (Coetzee 2013:167), where learning and transformation would be the desired outcomes once the recognition of the accented way of speaking and the situatedness of a constellation of thoughts has been obtained.

Revealing their own situatedness in their performances, Kukama, Shadi and Khoza assert their arguments by adding the filter of a language barrier, consciously producing a form of speech perfectly understandable for some members of the public but understood only with difficulty by others. This is a recurrent theme in South African art (Gentric 2016). In the context of the above sound-time-body constellation, the process of (sometimes failed) translation would seem closely related to mark-making. Extending Cassin's metaphor, if untranslatables are the fingerprints a language inevitably leaves, then a speaker's situatedness and his/her accented way of speaking would be just as relevant, and all three factors are components of the phenomenon that render both a language and an individual recognisable, and assert his/her right to individuated speech. It is no longer possible to erase these fingerprints from attempts at 'transparent' or 'unblinking' readings (Coetzee 2013:70-72)10 of the socio-economic conditions specific to the beginning of the twenty-first century.

However, the recognition that it seems impossible not to leave fingerprints - meaning that disrupting the glossy surface is inevitable in such a society - should not deny other aspects of resistance by translation. For example, in the epigraph to his publication 'Perfidious Fidelity' The Untranslatability of the Other (1994), Sarat Maharaj shares what he calls 'rough-gained sketch notes' penned on 27 April 1994, the day that South Africans first went to the ballot boxes as a democracy. Maharaj (1994:28) notes as follows: '27.4.'94: 'From Apartheid's dying grip, gently, gently ease the idea it turned against us with such murderous force - "the untranslatable other"'. Maharaj then defines the 'opaque stickiness' of translation, and how the idea that the 'other' might be untranslatable was a political construct used with 'murderous force' by the apartheid government.

Guided by the above researchers, I refer here to sound, time and matter as 'fingerprint' (Cassin; Dolar), 'accentedness' (Coetzee), and 'situatedness' (Goniwe; Mohoto-wa Thaluki). By using the notion of fingerprint, I argue for the right for an individual to be heard according to his/her personal means of expression, and, concurrently, that accentedness and situatedness should not lead to the assumption of the existence of an impenetrable 'epistemic barrier' (Maharaj 1994:29). The triad combining the use of language (individuated speech), the bodily voice, and the time-factor involved (which would include cultural situatedness) allows for a precise sonic fingerprint to evolve. This is encountered in the work of Kukama, Shadi and Khoza.

The new lives of struggle songs

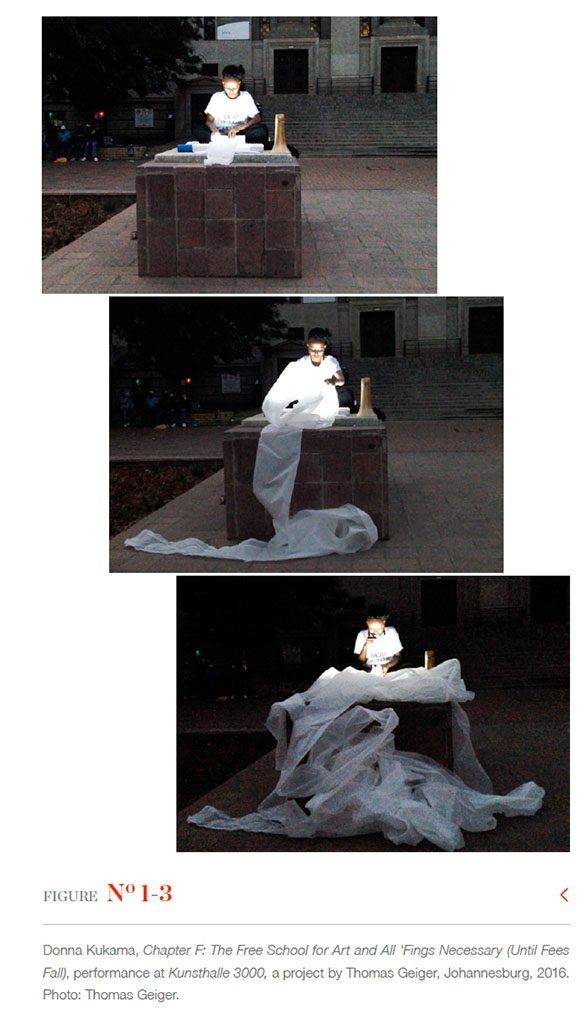

Since 2015, Kukama's Chapter F: The Free School for Art and All 'Fings Necessary (Until Fees Fall) (2016) has formed part of an on-going project of events, each referred to as a 'chapter' of a series. Chapter F was performed during the Kunsthalle 3000, a cycle of events initiated by Thomas Geiger in Vienna, Johannesburg, Geneva, Beirut, Paris, and Langenhagen. In Johannesburg, the selected venue was the Beyers Naudé Square outside the Public Library. Here, the Kunsthalle11comprised a hole in the paving where bricks had been removed during student protests. As a negative space rather than a construction, Geiger's Kunsthalle in Johannesburg represents a counter-institution, a space created by contestation and intended for contestation.

Chapter F was presented at dusk on 28 October 2016. To announce the event, the artist created flyers replicating the legendary blackboard used as a placard during the 1976 Soweto student protests. The original blackboard12 reads, 'To hell with Afrikaans', and signified that movement's thrust for the equal chance to be heard by refusing a language which was experienced as a threat to personal idiom. Kukama replaced the word 'Afrikaans' with 'Fees', thus re-situating the historical 1976 grievance within the context of the contemporary student movement and emphasising that students' struggles are ongoing.

The following transcription of my observation of the performance as it unfolded in the square allows for Kukama's performed action to intersect with my understanding around the materiality of sound that I deduced from her work. The stage for Kukama's performance is an empty brick plinth; and since Kukama is unaware of which public statue or monument it originally supported, it thus represents a generic monument and transfers monumental status to Kukama's performance. The artist sits down on the plinth with three items: a blue digital sound device, a roll of thin white paper, and a gilded megaphone.

As Beyers Naudé Square is a public space in the city centre, the sounds of the city (Mieszkowski 2017:11-31) function as part of the performance. In the documenting video made by Thomas Geiger using hand-held video camera,13 the sound captured by the inbuilt microphone gives indications on the surroundings. Without being able to see the square, the viewer of the video can establish a mental picture, he/she can for example fathom at the size of the square: the rattling wheels of a skateboard hitting the interstices between individual paving bricks; the ebb and flow of the voices of passers-by; the electronic jingle of music on a smart-phone; louder traffic sounds and hooters; the roaring engines of large trucks echoing among the buildings as they accelerate through a nearby intersection. When the artist switches on the sound device, a crowd is heard first chanting and then picking up the rhythm and the lyrics of Amakomanisi, an iconic song of the 1970s resistance movement. It is an equally popular chant of the current student movements because of both its historical significance, and the students' support of the current labour force - sometimes their parents - which, at that time, the university was intending to outsource (Mnqobi Ngubane 2017:38-39).

Kukama unravels the long strip of paper from the reel. This wide, translucent and brittle ribbon produces a bristling, rustling sound, almost like whispering, as it is caught by the evening breeze. Once the paper is fully unrolled, Kukama takes up her notebook and, using a small white megaphone, recites a text with short, rhythmic sentences and regular repetitions. Although both the rhythm and tune are reminiscent of a children's song (Kukama 2017), they steadily take on a political quality owing to the background struggle music. Kukama intones the sentences vigorously, half-chanting, as though completely immersed in the act of speech. Despite the aural association with nursery rhyme, the lyrics speak of 'the student movement and the struggles and violence that students faced in their plight for free, decolonized, quality education' (Kukama 22/08/2018).

At the end of the sound recording, Kukama leaves the plinth, announcing the inauguration of the 'Free school for Art and All 'Fings' Necessary. She calls for members of the public to sign up for the school, which is not intended to confer degrees or demand tuition fees, and which will convene at irregular intervals in varied locations under the auspices of anyone who wishes to organise a session at a venue of his/her choice. Such school 'performances' have been held since.14

Through this intervention, Kukama (2017) interrogates the meaning of real education, and how a true process of learning may be recognised beyond the mystifying ceremonial speeches of the university dons. By situating her performance on an existing empty plinth in a public square, Kukama further questions the extent of the capacity of a monument/institution. She has performed several such satirical comments on cultural institutions15 in other interventions that have functioned as counter-monuments.

Chapter F furthermore introduces the issue of the prominence of struggle songs in cultural heritage. While research on the performativity of struggle songs has included analysis of their appropriation by politicians for the advancement of their individual careers (Gunner 2015), within the context of the intergenerational student movements, the adoption of continually reshaped struggle songs16 adds to a complex cultural tradition.17

Kukama's contribution is of interest here as she introduces multiple layers of sound as part of the event. One layer is a recording of a male voice leading a struggle song, possibly a sonic trace from the 1970s, and another, her own voice, reciting live. These two voice tracks inform each other beyond the historical gap (hinged symmetrically on the date of 1994). By using her own live voice, the artist inserts her personal voice-track like a fingerprint amongst the soundscape on Beyers Naudé Square. By juxtaposing a recording and a live voice, Kukama creates a similar temporal lag between recording and action as Bruce Nauman. However, by the socio-historic specificity of her intervention, Kukama amplifies the experiments with the time-lag-effect of speaking "out of sync". Situated as the event is in central Johannesburg, further sonic layers claim the soundscape of the city. The metropolis in turn contributes an individuated sonic mark. In Chapter F neither the artist's words nor the male lead singer's are translated. In these several senses, Chapter F is particular to Johannesburg. In other chapters of the series, performed internationally, Kukama sometimes used two inverted translators, each speaking the language of the other (for example English and French),18 to explore the layered character of signification transmitted by voice and language specificity. In other chapters,19 Kukama has used allusions to the nursery rhyme and its situatedness to offset the absurdity of political speech, to reveal its underlying wisdom and thus claim it as a situated form of knowledge.

Nursery rhymes, songs from folktales and situated knowledge used for political effect address a larger political context in the work of Lerato Shadi: the plunder of territories gained in the colonial quest.

Sing-song beyond translation: the financial index and dialogue by storytelling

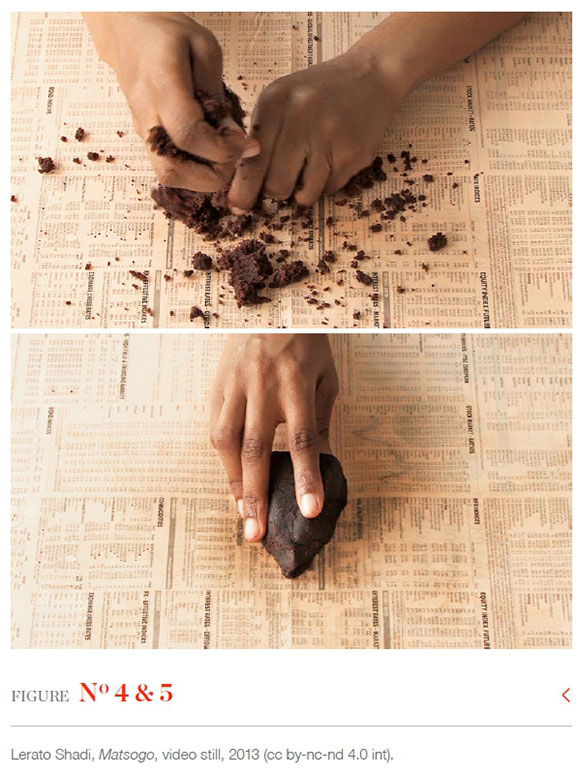

Shadi's Matsogo (2013) (intentionally not translated) is an action performed for a camera to be shown as a five-minute video. It has been signed by the artist, implying that all aspects of the use of sound and image may be read as intentional. As before, this detailed description of the video is meant to demonstrate parallels with the paradigm of the sonic fingerprint.

As the title of the video appears in white font on a black background, the artist is heard singing in Setswana. The singing continues as the image appears; in the centre of the frame stands a perfectly iced and sliced wedge of chocolate cake on sheets of discarded newspaper. The artist's hands enter the frame and, picking up the cake, reduce it to a pile of crumbs, the fingers moving to the rhythm of the song. Then kneading and pulping the crumbs, the artist crushes the greasy stickiness between her palms, pressing the dough into a lump of sugary brown matter. Gathering up the remaining crumbs, the hands reshape the dough into a rough cake-like form and with a calculated gesture of finality, place it back in the centre of the image.

Shadi has purposefully chosen newspaper pages featuring the foreign index: 'STOCK MARKET-RATIOS; HFR INDICES; EQUITY INDEX FUTURE ... BOND INDICES; COMMODITIES; BONDS INDEX-LINKED; FX-EFFECTIVE INDICES; INTEREST RATES - OFFICIAL ... EXCHANGE CROSSRATES' and so forth. This is a deliberate comment on the colonial powers who, during the Berlin Conference (1884-85), 'sliced up' Africa according to their own aspirations, subsequently exploiting the gains of the new territories, and devising rules to assist them in plundering the continent efficiently. The legacy of the uneven distribution of wealth globally is equally pervasive within the current neo-liberal system. When read critically, the foreign indices allude to gains earned from the everyday activities of the unprivileged, often to their detriment and against their will. Once a newspaper's written content has been consumed, its news is superfluous, and the paper is thrown out. At best, a discarded newspaper may become utilitarian, for example, to be used to wipe up messy spillages. As to the financial Index however, Shadi points to the way global economy affects each one on a daily basis.

While physically manipulating the dough in a meditative gesture, the artist sings to herself, two songs from Setswana folklore. As the two songs become interwoven, Shadi begins to create a new narrative with slippages of meaning. The lyrics are close variations of verbal sequences; to perform this polylogue the artist sings in contrasting voices: a 'tiny' hesitant voice then a 'tall', gruff voice. By not offering any translation, Shadi withholds any understanding of this polylogue from those who do not speak Setswana, although an informed viewer would be able to pick up two names in the songs - Tselane and Sananapo - that relate to popular traditional tales. Songs are a central feature of storytelling, and here they speak of food/eating, financial negotiations, envy, gluttony, the vulnerability of the body, betrayal, death but also loyalty and love.

Through her refusal to translate, Shadi intentionally problematises the reading of her interventions for her non-Setswana speaking viewers, and several of her performances strain the state of translation-without-correspondence to the limit. Shadi speaks openly of her relationship with the milieu of the galleries in South Africa where discrepancies between selective expectations concerning language skills are frequently showcased (Shadi 2018b:12-35). She then draws on this awareness gained in South Africa when effecting research or carrying out actions in public space in countries where she does not speak the main language,20 for example in Poland, France, Burkina Faso and Senegal. Matsogo was amongst others shown in Beijing.21 During these interventions, the engaged viewer must follow Shadi to the brink of the language abyss and experience the sense of vertigo that might occur just before translation (Gentric 2014). In Matsogo, Shadi's singing is outside the boundaries of interpretation, intoned as though in a private state of drifting pensiveness, beyond deliberate thought. Indeed, since this phase of regeneration is beyond translation, a new narrative may emerge. In more recent performances,22 Shadi considered voice in public space by pronouncing long lists of names, sanctioning the power of her voice to invoke (Goliath 2019) those who have gone before her: to bring them into our presence. Thus, in Shadi's work, while voice may be intensely intimate, it also enables empowerment in public use.

Once the dough has been reformed, Shadi gathers up the remaining crumbs scattered inadvertently across the paper, as though to hide the intervention. But however carefully she cleans, the paper remains greasy. It becomes impossible to undo the act. As the grease has penetrated the layers of paper, the newsprint has become translucent and now reveals the content of the underlying pages. Yesterday's frauds reappear just as the perpetrators believe that they have succeeded in covering up their traces. The kneaded dough, although roughly reshaped into the form of a slice of cake, is spoilt, drained of any victuals, and no longer appetising. The slice of cake, as a stand-in for the land and the bodies in the colonial process, has been worked though - it has been exploited beyond recognition and then given back, once all exploitable resources have been extracted. At the end of this intervention, Shadi presents physical matter that crudely apes the original pristine cake, but reveals a process of abuse, reshuffle and betrayal, highlighting questions around consumability and commodity (Shadi 2013b), ruthless depletion, and finally, refusal of translation.

While the hands seen in the image profoundly impress their fingerprints into the pliable but perishable matter, the voice weaves another trace - the soundtrack. Here, the songs morph from traditional heritage to contemporary relevance through the backdrop of the newspaper's foreign index, which inadvertently publishes everyday evidence of betrayals of trust and manipulated gullibilities. Furthermore, the kneading fingers and singing voice call upon a body (Tselane or Sananapo) in sacrifice, in erasure,23 in defiance and in agency.

Like Kukama's acknowledgment of the contemporary revitalisation of struggle songs, so Shadi's chosen songs are essential components of South Africa's oral heritage,24and her intervention shows how these traditional tales are continually updated, reactivated, and remain pertinent to current issues. The newspaper and its daily newsworthiness are also the concern of Mbali Khoza, the third artist, who enacts a fictive form of not translating.

On stitching and on not translating (tactility)

Presented at the Eastern Star Press Museum in Makhanda during the 2014 National Arts Festival, Khoza's What difference does it make who is speaking?25was one of four 'site-collaborative'26 performances curated by Ruth Simbao in a series of events titled Blind Spot. Khoza's MA dissertation (2016), a theoretical reflexion on authorship, shares the title of her 2014 intervention. Through the dialogue created between these two bodies of work, Khoza analyses the difficulties which may arise when claiming authorship in a (post)colonial context, where the question 'who has the freedom to act or to speak?' and the need for 'voice-consciousness' (Spivak 1988:285) must be critically scrutinised and the crucial necessity for fundamental change is indisputable. Khoza also highlights the singularities of artists' characteristic ways of treating authorship of written or spoken words.

The filmed video version of the performance, produced by Mark Wilby (2016), shows the artist seated on a high stool between antique printing presses and a table, which holds the tools of the nineteenth century mechanical printing trade. As the video opens, Khoza is already puncturing a long roll of heavy white paper with a thick needle, in response to a male voice27 speaking in Soninke.28 The recorded voice speaks patiently; pausing while Khoza meticulously enacts a process she devised to transcribe the words via the piercings. As the needle perforates the paper, irregular protrusions are created which mimic the intrinsic tactility of braille writing. A microphone set up beside the artist amplifies the sound of her tool piercing the paper.

The preparatory stage for the performance29 - not seen in the video piece - comprised Khoza's rewriting the words spoken in Soninke as she heard them, into phonetic isiZulu, which became a 'readable' but illegible text for the performance (Khoza [sa]). The performance itself produces a material trace. By means of the fictive signs, Khoza admits that she cannot understand words spoken by someone from her own continent. She can resort to phonetic interpretation (Khoza 2016:57) to transform them into a braille-like, tangible - though indecipherable - form, but cannot relate to the semantic content of the spoken words. Here, Khoza emphasises the notion of 'erasure that comes with translation' (Khoza 2016:104).

In her academic research, Khoza repeatedly defines erasure in different contexts, and ultimately, this notion comes to signify the impossibility of accessing the original voice (Khoza 2016:57, 61) and the 'desire by the West to re-author' (Khoza 2016:18) the subjects it has authority over.30 Khoza's approach explores erasure by translation as both a visual and a sonic process. The acoustic cyphers captured from the live, spoken voice, are transformed into a material residue by the artist's intervention, which comprises the sound recording, the phonetic transcription and the puncturing needle - the intervention leaves three kinds of traces: sonic, visible and tangible. These components merge into perforated paper rolled out on the floor among the printing presses, profoundly marked by the process of transcription, as according to the artist, 'erasure can also function as a form of mark-making' (Khoza 2016:104).

Sonic erasure may come in the form of noise: in the discipline of sound-studies, much attention has been given to noise - or 'unwanted sound' - as a semantic signifier.31Within the framework of colonial language dominance, the imaginary memory of the rattling of the printing presses, that used to fill the site where Khoza's performance is acted out, can be read as a form of erasure, a deafening out, the supplanting of an existing culture. This points to the significance of the relationship between the intervention and the site selected for its performance. The Eastern Star (founded in 1871) was one of the first English-language newspapers to be published in Makhanda (Simbao 2015:176), and owing to this colonial context, the printing room carries its own historicity. Khoza's intervention of piercing paper with a needle seems to re-enact the specific, aggressive gesture of the coloniser when, for the purposes of official business, the local languages were abolished, and the colonial occidental languages became dominant. The subtext of violence that pervades Khoza's performance is heightened by the situatedness inherent in the site.

By performing in the Eastern Star museum, Khoza not only draws attention to the coloniser's supplanting of local knowledge systems, but reminds her public that, even today, although only around 10% of South African citizens speak English as a mother tongue, it remains the dominant language in press and governmental institutions (Simbao 2015:176). Following Spivak (cited in Khoza 206:101), Khoza maintains that the effacing of identities continues, and the urgency to develop a voice-consciousness with which to speak has lost none of its exigency. Khoza has conducted her research with reference also to the Zimbabwean writer, Dambudzo Marechera. In his book The House of Hunger (Marechera 1978:39), he compares the process of writing to the gesture of re-stitching an open wound. All through Marechera's text, the reader encounters multiple other metaphors associated with that of 're-stitching' his 'torn' mind. Marechera identifies the situation of living with two languages (his mother tongue and the language of the coloniser, English) as a daily fight for his mental health. The gesture performed by Khoza draws its metaphorical strength from Marechera's text.

Khoza (2016:96-105) further links her work on erasure to Kemang Wa Lehulere's on amnesia. According to Khoza, Wa Lehulere 'demonstrate^] the authority that the author can possess over the voice and how this voice can easily be silenced through various gestures of erasure', for example in Remembering the future of a hole as a verb 2.1 (2012). Through the work of Tracey Rose, Khoza (2016:17,50,58,59), 'investigates how language through naming distorts identity', but also transcribes an 'imagined voice' whose 'source is unknown'. On the ambivalent character of erasure, Khoza's questions on authorship fluctuate; in her thesis, she asks: 'Who is speaking? Why does this matter? Who is speaking on behalf of whom?'.

These fluctuations are heightened by the fact that Khoza's theory is constructed around a conference by Michel Foucault (1969) on the role of author. Foucault's argument is deeply embedded in occidental tradition. Khoza (2016:16,19,60,89) however is also keenly sensitive to the South African context, in which authorship is questioned from a radically different point of view, and where the objective is to address the importance and the urgency of being recognised, the right to individuated speech, the right to claim a voice, a voice-consciousness. Beyond questioning the ways that authorship can be erased, disguised and distorted, Khoza considers the possibility of 'using the language of power in retaliation', or to show how language can be used not only 'to perform power but also to question and refuse power' - how might this be contrived?

The male voice heard throughout the performance pronounces the sentences attentively while Khoza reinterprets them with her needle. Speaker and listener are both aware that the latter does not understand, and the careful articulation of seemingly random phrases takes on the effect of a language lesson. The voice seems to be speaking into a certain emptiness, knowing that the words fall on 'un-hearing' ears (Goniwe 2006). In this context, the speaker's words become untranslatables, as do the listener's piercings. For any member of the public who does not understand Soninke, the spoken voice becomes a phonological sign from which he/she is unable to extract semantic meaning (as with Shadi's songs or Opalka's counting voice). Khoza's devised, Active intervention makes this inability tangible: the thick white paper32 carries the traces of her method of phonetic translation; and the labour of producing the untranslatable imprints becomes audible through the amplification of the sounds of the piercing needle, decoded into sound but not into decipherable words. As Khoza transcribes her speaker's words into invented, phonological braille,33 the sound matter of a spoken voice transgresses the borders between the visual, the tactile, the acoustic, and the gaps between languages in a pan-African context.

The gestures performed by Khoza, and the calm, concentrated quietness in the way she is seated, belie her difficulties in fathoming these words with the means at her disposal - just needle, paper, amplifier, rhythm, stitching, and mark-making; their quietness underlines the fact that she herself chooses not to communicate. Instead she becomes the medium, receiving audible signals, and producing a material, tangible inscription in return. The perforated paper stands for physical evidence, not of the content of the spoken words, but of her strife, hearing but unable to listen, a witness to her metaphoric attempt to pierce the language barrier, to grasp at something that resists easy understanding (i.e. control) - by not translating. By enacting repeated processes of (only partially fictive) interpretation, which concentrate on probing the initial moment of speech but resist the closure of a random equivalent in another language - which, as a final product, would be referred to as a translation - Khoza highlights the process, and finally the unquestionable importance of who is speaking, in a quest for individuated speech all the while questioning and refusing power.

Informing layers: the situatedness of performative interventions

The three works described here grow out of each artists' personal way of grappling with language, with acoustic and oral heritage, with language barriers and with individuated speech. Through their creative engagements, the artists generate new paradigms. The situatedness of these pieces is owing to South African legacies (struggle-songs, storytelling, the historically fraught question of the right to claim authorship),34 and how sound becomes part of public space as well as having significance at the sites of the interventions: a hole or negative space in the pavement on Johannesburg's Beyers Naudé Square, a discarded newspaper page showing the foreign index, and Makhanda's Eastern Star Museum.

The subtext of these works deals with certain realities that have been and still are covered up by state propaganda. It speaks of everyday protest actions and the xenoglossic leap an individual must perform when he/she cannot speak all the languages of his/her own country; as well as how struggle songs and folktales are never fixed but shift from one version to another, testing new ways to express grievances, of how they are endowed with the wisdom of situated knowledge. The way these songs are constantly reformed indicates both their anachronistic nature and the significance of the traces of time. These multi-vectored processes oblige the viewer to address questions around authorship and the right to individuated speech.

Voice encompasses the everydayness of the courageous gesture of overstepping the barrier between subject and world35 and encountering the unknown and unheard-of.36 These artists are aware of voice as fingerprint - time and matter - by allowing random, passing city noise to become part of a soundscape, through incorporating songs from two diverse aspects of South African cultural heritage, and by presenting the vulnerability of the individuated position in publishing or when speaking out. They capture situations where a language leaves a material trace. Voice manifests in these works as intimate and vulnerable but also as constituting 'world'. The sounds simultaneously refer to the momentous, the intimate and the everyday.

Despite the three artists appearing to play games of hide and seek with language, their works have in common the painful recognition that misunderstanding seems to be inevitable in the process that South Africa is currently experiencing. In a spirit of language activism (as described by Coetzee 2013), they have realised that these misunderstandings and the underlying violence must be worked through if the real 'process of ending'37 apartheid and global apartheid-like situations38 is to begin.

Untranslatability and accentedness can be imagined as hesitant, vulnerable fingers leaving imprints that penetrate layers of matter, sound, time, or thought. Are fingerprints nothing more than smudges on a fleeting surface layer? The layers encountered in Kukama's, Shadi's and Khoza's performative interventions interpenetrate, each leaving traces on the others, in-forming one another.

Sound, when recorded, leaves a tangible imprint on a sounding device, such as grooves to be followed by the needle on a turntable, or the fragile sound-tracks identified by a digital system - like a fingerprint. The vibrations of voice resonate in sound, time, and matter and either fade or are picked up by recording or receiving apparatus. They are fragile and fleeting, raising the question of how long they might remain legible and the circumstance that, in order for a sound wave to be recognised as voice, some form of listening needs to occur. Fingerprints are unfalsifiable and anachronistic. Let us not read them as a sign of the misleading construct referred to as 'untranslatability of the other' that Sarat Maharaj warned us against in 1994, but rather let us embrace them as a promise of recognition, as the imprint of each one's situatedness.

Acknowledgements

My sincere thanks to the artists for the generosity with which they have engaged in conversation as well as to the participants in the working-group Sound Unheard (Paris/ Rennes/Berlin). The research for this text was made possible first and foremost by a postdoctoral scholarship from the University of the Free State of South Africa and secondly an invitation from the Künstlerhaus Villa Romana in Florence. It furthermore benefited from funding by the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, Paris, and the Labex ArTec, Paris 8, for the project Yif Menga.

Notes

1 . In France in July 2018, during the finals of the soccer World Cup, as each new goal was scored, all the voices of the city seemed to add up to one single roar.

2 . For the context of the work of Nauman, within the nexus contemporary art/ sound art, see Seth Kim-Cohen (2009:36, 213-214).

3 . The concept of 'information' is used in the sense defined by Gilbert Simondon (1958).

4 . The recent conference Spectres de l'audible (2018) gave an idea of the extent of the questions addressed by this discipline. Amongst others, vibrations in architectural structures, procedures by which speech-hearing norms are established, a president wiping out tapes of evidence he himself commissioned, or sound used in riot control.

5 . Such as the way artists are reclaiming space through art, the historical and contextual construction of identities, the material conditions effective in the everyday experiences of individuals in social space, questions around bilingualism and multilingualism, and a critique of the marketing of the glossy ideal of post-apartheid South Africa (Goniwe 2006:84,88,89,98,120).

6 . Although for professional translators who wish to complete their job efficiently, untranslatables are merely an irksome reality of daily business, they have also prompted philosophers to doubt entirely any possibility for translation (Ost 2009:157-177).

7 . Cassin's research was published in 2004 as a 'dictionary of European untranslatables' and reveals the extent of this phenomenon.

8 . Dolar's Only one voice (first published in 2003) may be respected as a precursory text for sound studies.

9 . The fact that each voice is considered unique has led to its use in biometric voice recognition security technology (voiceprint) as a secure method to identify an individual, like a tangible fingerprint.

10 . Coetzee (2013:70-72) uses the expression in reference to Goniwe and to Okwui Enwezor.

11 . 'The term Kunsthalle is used in German-speaking countries and refers to a special kind of municipal museum, the historical aim of which was to make art accessible to all people' Kunsthalle 3000 [sa].

12 . This artefact is in the collection of the Hector Pieterson Museum.

13 . Geiger (2016), this video is an unedited audio-visual trace from the subjective point of view of a bystander.

14 . For example, at Keleketla! Library in Johannesburg by Masello Motana in September 2017 (Keleketla.org).

15 . At biennale openings (Kukama 2017).

16 . 'These instruments are our history books and these songs our encyclopaedia' (Koela 2017:30).

17 . It may be noted that a similar intergenerational recontextualisation of resistance through music occurred in Burkina Faso, by the passing on of songs between the Sankara generation of the early 1980s and the members of the 'balai citoyen' of 2014 (Degorce & Palé 2018). Also, Kukama's use of an audio-player to mediate the singing voices in her event touches on a different but vast discussion, namely the role played by media and the portable radio unit in the Algerian resistance in Frantz Fanon's (1959:303-330) text 'Ici la voix de algérie'.

18 . For example, in Lyon (2013).

19 . For example, in Säo Paulo (2016).

20 . Just as Roman Opalka has done in changing circumstances throughout his career, significantly complicated by the constraints of cold war politics.

21 . At Zajia Lab Beijing project space, as part of the project and exhibition Fast Forward (2014) curated by Olivia Anani.

22 . In Basupa Tsela (2017)

23 . Shadi's Masters dissertation is dedicated to the violence of historical erasure (Shadi 2018b).

24 . See Cassin (2016:80) on the notion of patrimoine immatériel in the African context and beyond UNESCO vocabulary.

25 . Khoza (2016:84) recognises Foucault's reference to Beckett's question 'What matter who's speaking?', (Qu'importe qui parle?).

26 . Simbao (2015:176) uses this expression 'in order to indicate that site has the agency to collaborate with a performer who is sensitive to concerns of "place". A performer does not simply "translate" what she or he sees in a particular place, but collaborates with place in order to co-create meaning.'

27 . See Kolesch (2006:56) on the particularities of the 'disembodied' voice as amplified by a loudspeaker.

28 . 'Soninke is located primarily in Mali and is a Mande language spoken by the Soninke people. It is also spoken to a lesser degree in Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Gambia, Mauritania and Guinea-Bissau' (Simbao 2015:176).

29 . Cited by Khoza (2016:103).

30 . In an earlier performance, 'Do it like this!' (2013), Mbali Khoza and Georgia Munnik build a complex argument on the function of language when the coloniser, with the intention of controlling the workforce, devised the instructional language, Fanakalo. This was interpreted as a sign of his ultimate disavowal of indigenous languages (Khoza 2016:24-26).

31 . Mentioned by Mieszkowski and Nieberle (2017). This may be compared with the thinking of John Peffer (2015).

32 . The paper is the type used as drawing-paper in the Fine Art context, whereby the mark-making of the piercing may be related to drawing.

33 . Braille is a tactile form of communication that may be 'read' without the sense of sight.

34 . The same could be argued within the specific contexts of the works of Bruce Nauman or Roman Opalka.

35 . As described by Sowodniok (2013:13,15).

36 . As described by Mieszkowski (2017:17).

37 . 'Understood as an activity' (Coetzee 2013:ix-x).

38 . See Cassin (2016:227-239) on the need for language-teaching in the migrant camps at Calais.

REFERENCES

Cassin, B (ed). 2004. Vocabulaire Europeen des philosophies, Dictionnaire des intraduisibles. Paris: Le Robert, Seuil. [ Links ]

Cassin, B. 2016. Éloge de la traduction, Compliquer l'universel. Paris: Ouvertures Fayard. [ Links ]

Coetzee, C. 2013. Accented futures, language activism and the ending of apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Degorce, A & Palé, A. 2018. 'Performativité des chansons du Balai citoyen dans l'insurrection d'octobre 2014 au Burkina Faso'. Cahiers dÉtudes Africaines 2018/1(229):127-153. [ Links ]

Didi-Huberman, G., 2008. La ressemblance par contact, archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l'Empreinte. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. [ Links ]

Dolar, M. 2006. A voice and nothing more. Cambridge & London: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Geiger, T (dir.) 2016. Chapter F: The Free School for Art and All 'Fings Necessary (Until Fees Fall) [Video recording]. [ Links ]

Gentric, K. 2014. Project Mine, les notes du traducteur. afrikadaa, special issue Be/ National: 65-69. [O]. Available: http://issuu.com/afrikadaamagazine/docs/be-national?e=4280787/6664408. Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Gentric, K. 2016. Traduire comme pratique artistique, cinq propositions-interfaces en Afrique du Sud. Marges, Revue d'art contemporain, Special issue Globalismes Fall/Winter 23:74-85. [ Links ]

Goliath, G. 2019. 'A different kind of Inheritance': invocation and the politics of mourning in performance work by Tracey Rose and Donna Kukama, in Acts of Transgression, Contemporary Live Art in South Africa, edited by J Pather & C Boulle, Johannesburg: Wits University Press:124-147. [ Links ]

Goniwe, T. 2006. Negotiating space: some matters in South African contemporary art, in Olvida quién soy/ Erase me from who I am, (Exhibition catalogue) edited by ED Ose. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Centro Atlántico De Arte Moderno:83-125. [ Links ]

Gunner, L. 2015. Song, Identity and the State: Julius Malema's 'Dubul' ibunu' Song as Catalyst. Journal of African Cultural Studies 27(3):326-341. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 2011 [1959]. Ici la voix de algérie..., in Frantz Fanon, CEuvres. Paris: Edition La Découverte:303-330. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1969. Qu'est-ce qu'un auteur? Bulletin de la Société frangaise de philosophie, 63(3) July-September:73-104. [ Links ]

Fréchuret, M. 2016. Roman Opalka, in Effacer, Paradoxe d'un geste artistique. Dijon: Les Presses du Réel:153-162. [ Links ]

Keleketla! Library. [O] Available: https://keleketla.org/2017/09/29/the-free-school-for-art-and-other-necessary-fings-maropeng-with-masello-motana-and-nape-motana/ Accessed 12 August 2018. [ Links ]

Khoza, M. [sa][video recording I:02 minutes] [O] Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5s9ngfgp-NQ Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Khoza, M. 2016. What difference does it make who is speaking? MA dissertation, Witwatersrand University, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Khoza, M, artist, 2018, Skype Interview by author, 24 January. Grahamstown & Paris. [ Links ]

Kim-Cohen, S. 2009. In the blink of an ear, toward a non-cochlear sonic art. New York & London: Continuum. [ Links ]

Koela, E. [sa] (November 2016). African Music, Education and Being Together: an Exchange between Ernie Koela and Asher Gamedze. Pathways to Free Education: From Pamphlets to Action Volume 2 (Strategy & Tactics) p28 [O]. Available: https://drive.google.eom/file/d/0B6dVO9Lj0oLkd1FSOE52aDZvOW8/view. Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Kolesch, D. 2006. Wer sehen will muss hören. Stimmlichkeit und Visualität in der Gegenwartskunst, in Stimme, Annäherung an ein Phänomen, edited by D Kolesch & S Krämer. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Taschenbuch der Wissenschaft: 40-64. [ Links ]

Kukama, D, artist, Studio Donna Kukama. 2017. Interview by author. 27 March. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Kukama, D. 22/08/2018. E-Mail to Katja Gentric. Accessed 22 August 2018. [ Links ]

Kunsthalle 3000. [O]. Available: http://www.kunsthalle3000.com Accessed 12 August 2018. [ Links ]

La Fabrique des arts sonores, Spectres de l'audible, Sound Studies, Cultures de l'écoute et arts sonores, 7-9 June 2018, Paris: INHA & Phiharmonie de Paris. [ Links ]

Maharaj, S. 1994. 'Perfidious Fidelity' The Untranslatability of the Other, in Global Visions, towards a new internationalism in the visual arts, edited by J Fisher. London: Kala Press/The Institute of International Visual Arts:28-35. [ Links ]

Marechera, D. 1978. The House of hunger. London: Heineman. [ Links ]

Mati, T. 2016. Understanding the Struggle Songs of Fees Must Fall, Media for Justice. [O]. Available: https://www.mediaforjustice.net/understanding-the-struggle-songs-of-fees-must-fall/. Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Mbhele, M & Walker, GR. 2017. Struggle songs let us be heard. Mail & Guardian. [O]. Available: https://mg.co.za/article/2017-10-13-00-struggle-songs-let-us-be-heard. Accessed 14 Mai 2018 [ Links ]

Mieszkowski, S & Nieberle, S (eds). 2017. Unlaute, Noise/Geräusch in Kultur, Medien und Wissenschaften seit 1900. Bielefeld: [transkript]. [ Links ]

Neumark, N. 2017. Voicetracks, attuning to voice in Media and the arts. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Ngubane, M. 2017. Workers' struggle with outsourcing at the University of the Western Cape 'The beginning of the end', Publica[c]tion edited by A Gamedze & LA Naidoo: 38-39. Johannesburg & Delhi: Publica[c]tion Collective + NewText. [O]. Available: https://www.amazon.com/PUBLICA-C-TION-New-Text-ebook/dp/B0799PYLLP and https://gorahtah.files.wordpress.com/2017/11/publicaction_ pdf-for-web_pages1.pdf Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Opalka, R. [sa]. Roman Opalka: Opalka 1965 / 1 - °° official website. Available online http://www.opalka1965.com/fr/cartesdevoyage.php?lang=en; http://www.opalka1965.com/fr/voix.php?lang=en. Accessed 9 April 2019. [ Links ]

Ost, F. 2009. Traduire, défense et illustration du multilinguisme, Paris: Ouvertures Fayard. [ Links ]

Peffer, J. 2015. Notes on cuts on censored records, in afrikadaa #10 2015/16, The politics of sound: 64-65. [O]. Available: https://issuu.com/afrikadaamagazine/docs/ politics_of_sound/64. Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Shadi, L. (dir.) 2013. Matsogo. [single channel HD-video duration: 5minutes]. [O]. Available: http://vimeo.com/leratoshadi/matsogo. Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Shadi, L. 2013. LShadi_DocCV-2.pdf [O] http://www.leratoshadi.art/_files/LShadi_DocCV.pdf Accessed. 13 August 2018. [ Links ]

Shadi, L, artist, Künstlerhaus Villa Romana, 2018a. Interview by author. 19 July. Florence. [ Links ]

Shadi, L. 2018b. Violence of Historical Erasure. MA dissertation, Weißensee, Kunsthochschule Berlin, Berlin. [ Links ]

Simbao, R. 2015. Editorial: Blind spots: Trickery and the 'opaque stickiness' of seeing, Image & Text 25:175-191 [ Links ]

Simondon, G. 2013[1958]. L'individuation ä la lumière des notions de forme et d'information. Grenoble: Editions Jérome Millon. [ Links ]

Sowodniok, U. 2013. Stimmklang und Freiheit, Zur auditiven Wissenschaft des Körpers. Bielefeld: [transcript]. [ Links ]

Spivak, GC. 1988. Can the Subaltern speak?, in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by C Nelson & L Grossberg. Pamshire & London: Macmillan Education:271-313. [ Links ]

wa Thaluki (Mohoto), LD. Corporeal HerStories: Navigating Meaning in Chuma Sopotela's Inkukhu Ibeke Iqanda through the Artist's Words, in Acts of Transgression, Contemporary Live Art in South Africa edited by J Pather & C Boulle, Johannesburg: Wits University Press:107-123. [ Links ]

Venuti, L. 1995. The translator's invisibility, a history of translation. London & New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Wilby, M. (dir.). Mbali Khoza, 'What difference does it make who is speaking?' [Video recording 9:52]. [O] Available: https://vimeo.com/126741901 Accessed 15 August 2018. [ Links ]

Wismann, H. 2012. Penser entre les langues. Paris: Albin Michel/Flammarion. [ Links ]