Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.33 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n33a5

ARTICLES

Do not make Africa an object of exploitation again

Laura Burocco

Post-doctoral candidate at the School of Visual Arts, Federal University of Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil lburocco@gmail.com | https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7767-4941

ABSTRACT

This article aims to present the audience reception of Black Panther by an Afro-Brazilian public. It raises questions about the autonomous appropriation of the film's messages by an Afro-Brazilian diasporic community. It also questions the construction of a black identity, present and future, linked to an apparent rediscovery of the African continent by the global cultural industry. The theoretical framework is Afrofuturism. The methodology is audience reception studies as well as thematic content analysis.

Keywords: African diaspora; cultural industry; Afro-Brazilian identity; black movement; cognitive capitalism; Black Panther; Afrofuturism.

Introduction

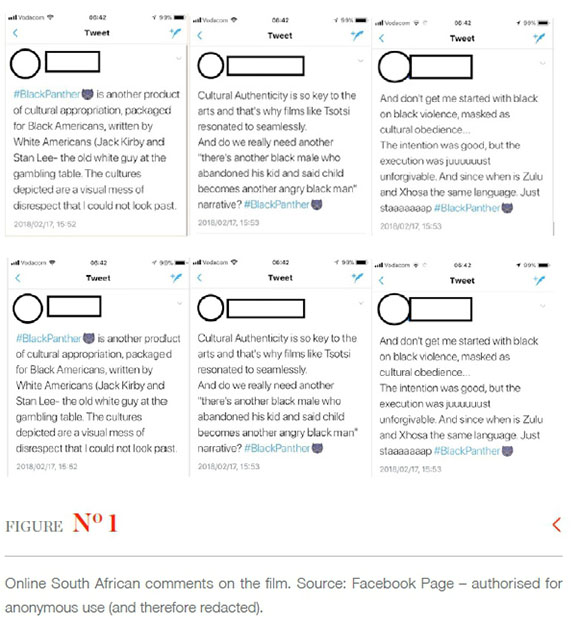

The Marvel mega-production, Black Panther, directed by Ryan Coogler (2018), was received with great enthusiasm both globally and, equally, in Brazil. In recent years, the Brazilian black movement is finding its voice. While human rights violations, racism and similar issues, have for too long remained silenced in Brazilian society, they are now denounced and claimed publicly. In addition to these causes, there has been a rediscovery of the African continent by various sectors, mainly cultural and intellectual. This is evidenced by projects such as: Episódios Do Sul: Novos Pontos De Vista by the Goethe Institute SP; Conversation in Godwana by Juliana Caffé e Juliana Gontijo; Africa Hoje curated by the Museum of Art of Rio MAR; several films festivals; and the South South programme curated by the Goodman Gallery. The euphoria that accompanied the debut of the film Black Panther was not surprising, but it raised questions about the inability to articulate a critical discourse in relation to the film. My attention was drawn to posts I saw on Facebook by South African women criticising the film, one of them going as far as to demonstrate serious offence.

A cursory search on the internet revealed that, in South Africa, it was possible to find voices that were critical of the movie, something that was almost impossible to find in my Brazilian social media network. One of the Brazilian posts that caught my attention was by a black man, poet and writer, activist and human rights defender from a well-known favela in Rio de Janeiro, Acari. In his post, Deley Wanderley Cunha, presented a list of hypothetical questions that, if he was the representative of Brazil at the United Nations, he would make to King T'Challa.1

Inspired by this post, I decided to "follow" the women who commented on the film, checking their public posts regarding the film and eventually contacting them by email. At the same time, I did online research based on comments on the film that appeared in the so-called "rolezinhos" or "online pages"; comments following articles referring to the film; and Brazilian responses to the hashtag #WhatBlackPantherMeansToMe.

I also reviewed a series of articles by Brazilian and international scholars that were spontaneously translated and posted on some engaged Brazilian websites. Based on this data, the article aims to present the film's reception by a predominantly Afro-Brazilian public. The data is not exclusively Afro-Brazilian however, owing to the fact that the author, besides not being Brazilian, is also not black, and because not all the commentators as part of the sample have declared their own race. The theoretical framework is embedded in Latin American decolonial theories and the aim of the article is to apply these theories to the reading of Black Panther from a largely Afro-Brazilian diasporic perspective. Particular attention is given to the 'coloniality of power', defined by Quijano (2000) as a type of colonial inheritance that persists and multiplies even when colonialism is supposedly overcome by modernity, and affects the sphere of power, knowledge and being. This theoretical field is placed in dialogue with a context of post-Fordism productive relations, where the transformation of work - from tangible to intangible (Lazzarato & Negri 2001) - shifts the production of value reinforcing new economies and cultural industries.

The article is divided into three parts: the first is based on the comments found online, unedited but translated, to provide an overview of the tone of the online conversation. This opening part of the article sets the scene for the subsequent dissection of various aspects of the film and its reception. It aims to give a Brazilian panorama of the reception of the movie and maintain, as much as possible, the personal impressions of the commentators, without adding an interpretation by the author. Following this section, a general reflection on the film is presented. It does not aim to address a critical analysis of the film due to space constraints, but aims to focus on three key points: the black representation in the audio-visual; the representation of women; and the insistence on the reproduction of a binary vision of wrong/right that is understood as functional to the interests of the film. To conclude, the third section attempts to provide a Brazilian Afro-diasporic analysis of Black Panther, framing the film within the Brazilian socio-political context; placing the criticism of the film within discourse that covers the appropriation of social struggles by the cultural industry as a strategy of cultural imperialism that attend only to market interests. Originally, these analyses were a collaboration with Deley Wanderley Cunha, but owing to his personal situation, which has been under a protocol of personal security since the murder of council woman Marielle Franco in Rio in March 2018,2 further collaboration was not possible. Even so, it is important to record our attempt and include his comments, which were the starting point for the reflections in this article, especially in relation to the representation of women.

Media reception in Brazil: online comments

Deley de Acari posted the following:

I have doubts about whether all African elites are concerned with combating racism. As much as it maintains genocidal conflicts against other African peoples. Or that they are in some way reduced to the business and privilege that inequalities or extreme poverty guarantee. Hence to worry about racism in the world or in the black diaspora? Utopia is worth in a story that I invite to write.

Halooo the film is made in the USA by Marvel. Even at this time we worry about assaulting ours. And a commercial film that like everyone has some topics of everyday life, in the case some principles maintained until today by and in communities. Now let's not turn fiction into contemporary reality.

The king of Wakanda, I do not know ... left, right, center or Wakandense of the white line? From the White House ... .

Patience ... A cool step was taken ... Black majority cast (and black director) in a Disney over production.

Rhaysa Ruas, a militant, researcher and black lawyer, and a member of the Black Collective Patrice Lumumba, one of the women who commented on Deley's post, answered my email by sending this comment:

I find the film a disservice. I think it puts Africa and the diaspora in a situation of rivalry, competition and humiliation for whites' entertainment. I think it is essentialist, idealistic and bourgeois. I think hetero normative. I think it strengthens the nation-empire state. I think it disrespects the history of struggle and resistance both in the African diaspora and in Africa. I think it brings a representativeness that only reinforces the status quo and creates conflicts between us using a legitimate shortage/ need of ours and in that sense is cruel. I think the end of the film, the UN, the NGO, says a lot about the message he wants to get through.

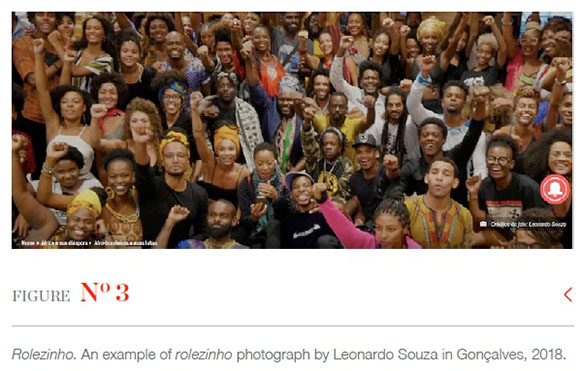

Comments were also collected from the "rolezinhos" (online) pages; in Brazil, the word "rolezinho"3defines specific occupation of public spaces and shopping centres organised through online mobilisation, mainly on Facebook, by groups of thousands of young, mainly black people from the periphery. Since its initial occurrence in 2013, rolezinhos quickly spread throughout Brazil's largest cities, raising both criticism and support. The criticism reflects the strong prejudice and racism that link the gathering of young black people from the periphery to criminal events such as riots, theft and aggression. The supporters, in turn, defend the phenomenon as a form of resistance by young people from the periphery to the social apartheid in Brazilian metropolises, denouncing the socio-economic and racial inequality in the country.

In relation to Black Panther, the "rolezinhos" were organised by young blacks and activist groups in order to promote communal sessions, even bringing together up to 275 people in a session in Sâo Paulo, and 185 people in Porto Alegre. In Rio, one of these "rolezinhos" happened at the Shopping Leblon, one of the most affluent neighbourhoods in the city; its impact was both symbolic and physical. The lack of black bodies, except to perform service functions, in these places is noticeable, so their massive imposition during a "rolezinhos" represents an affirmative occupation by black people of the Leblon territory, where many are marginalised because the neighbourhood is understood to belong to the city's white elite (Gongalves 2018).

The commentators wrote very positive responses to film. They felt that the film was finally giving "space" to black voices and bodies; that the representations were positive; and although they admit that the progress being made is small ("homeopathetic doses") it is still progress. They also felt that the film was opening a "space" for which they could gain actual transformation and empowerment in Brazil. They also acknowledged that to be black in Brazil is dangerous, irrespective of where one lives; and ultimately viewing the film allowed them to embrace their "blackness" with pride.4

The article, Two Black Panthers by Slavoj Zizek (2018), was translated and published on the Bontempo website, receiving sophisticated and critical comments by the spectators, including:

It has never been so easy to root for the villain as Black Panthers. The cynicism of Wakanda's black aristocracy is scandalous. They cannot help their articulate and strategic periphery, which must thus remain to guarantee the existence of paradise on earth. As Zizek already points out, those who advocate the socialization of advanced technology in favor of the struggle of the oppressed are the film's villains. When this socialization happens, it happens via UN. That is, world dominating order. Just another haunting narrative that teaches us to be orderly, peaceful and collaborative: there is room for all in capitalism;

Every perspective of this film is really interesting! It is important to say that all this production strongly exposes a worldview, i.e., a way of seeing the world in all areas of life; and that the whole script was designed to convince the audience of it. It's worth watching? Yes! The graphic of the film is jaw-dropping, the action scenes are very electrifying, and the rituals symbolizing the African tribal traditions carry us to a reality totally different from ours. The performances of the actors are sensational, they masterfully incorporated the roles [...] The way the technology was perfectly integrated into the African culture was simply incredible. The visual effects and the aggregation of the modern with the old were undoubtedly fantastic. One of the best and most creative films I've ever seen';

Wakanda reminds us of Russia a little when Zizek says that it is a balanced country, without social problems, rich and happy, but without contact with the rest of the Earth. It is impossible to live on Earth and not depend on anyone. No one on earth is rich alone. The problem with Hollywood is that the films and their stories are poor but full of minor details. The speech of the characters is poor and instead of a good speech Hollywood prioritizes the movement of people, automobiles, airplanes and weapons. We even want to have a position in the film which is impossible because there is no talk to show the reason why actions and attitudes. Hollywood wants to make films on subjects where the conversation should be long;

Hollywood would never make a movie against the establishment, even more with a degree of notoriety equal to the Black Panther;

Hollywood, has no more subject matter, and is now exploiting the blacks. Hollywood is more concerned with what its next market is going to be, because matters are exhausted;

My 13-year-old daughter liked the movie. She felt identified;

I've been a Black Panther and Luke Cage reader since I was 9 in the 70's, and as a reader I felt immersed in the HQ narrative of that time. We had few black heroes with whom we could identify. The film bothered me not to swallow the viewer into the narrative. At crucial moments the jokes worked like an anti-climax and had doubtful content (the sister asks to accelerate the ceremony because the clothes bother !!!!). By the time they cut the CIA agent's word I thought the movie would turn into an episode of "Everybody Hates Chris" or another American bullshit. Some passages reminded me of 007 movies (showing the technologies he would use in South Korea). In the South Korean scene, I thought maybe Tarantino would be a better option to direct this film in the action scenes, choice of soundtrack and what he did in "Jackie Brown." Just as the drink takes away the Black Panther's strength from the main hero, I think the film as a whole is coldly calculated to take away whatever venom it may have in a narrative about blacks in the US. The characters are emptied of content to such an extent that a CIA agent becomes only a skilful pilot.

In addition, "Black Panther": a "black nation" emerges by Achille Mbembe (2018) was translated and published by Medium, which also received a number of responses:

The film was unexpected; the best Marvel has done so far. Michael B. Jordan is incredible;

Thank you for translating and posting this text. I have not even seen the film yet, but I was distressed at how many white academics were criticizing the film without any deep knowledge about the work or about Africa. These criticisms I only see as a possibility, that of non-representativeness. For the first time in the history of Blockbusters, blacks are not the slaves, but the protagonists, the heroes, the spies, the scientists, the warriors. It is something so surreal to white academic, capable of generating so much perplexity, that his intellect only gets a justification for his lack of understanding, that "the movie is not so good", "contains flaws", "have language errors, of grammar", or even more obscure things coming out of old dictionaries: "This text was a balm. Thank you!

The hashtag #WhatBlackPantherMeansToMe/#CosaBlackPantherSignificapormim created by the American Kayla Marie, also received the following responses in Brazil:

I'm amazed, touched and shocked! The strength of Wakanda took me over and gave me even more strength in the fight!;

Seeing that thousands of children now have a super hero who looks like them;

To see my father, with nearly 50 years, want to cry to finally be seeing one of his favourite characters from comics on the movie screen, something that he never thought to happen.

A general overview of three selected issues with regard to the film

The film allows a critical analysis from various perspectives. Hence, this article focuses on three aspects: black representation in the audio-visual; representation of women; the repetition, which is functional to the interests of the film, as well as the use of binary divisions of wrong/right and good/bad.

Undoubtedly, one of the aspects most positively commented on was that the movie promotes black representation in Hollywood cinema and, consequently, worldwide. Tillet (cited in Cardoso 2018) reiterates that 'since Malcolm X by Spike Lee in 1992, there was no such hype and hope surrounding a film in the African American public'. According to Freitas (2018), 'with a mostly black cast, a black director, screenwriter and costume designer, as well as a speculative fiction based on a narrative of black experience, the movie can be considered as an example of Afro-Futurist production'. Considering this achievement, the movie becomes an important tool to denounce the lack of black professionals in the audio-visual world.

With regard to the representation of women, despite a positive first impression, a more in-depth analysis can raise some doubts. Although women take a spectacularly emancipated and autonomous position, a deeper observation reveals that they continue to be represented within a hetero-normative stereotype, reproducing a patriarchal vision of society. The attitude of the bald warrior, declaring herself faithful to the throne, regardless of who occupies it, in her unquestioned and submissive execution of pre-established orders is familiar. It may refer to Hanna Arendt's The banality of evil (2013) or, for a Brazilian public, to the short film The day in which Dorival faced the guard (1986) by Jorge Furtado, where a prison guard cannot give any justification for his behaviour, except for the execution of orders coming from anybody the guard is able to identify.5 The only moment for the women warriors to make an autonomous decision is when they venture on a strenuous path to ask for help from the lord of the mountains. He will be the one who solves the situation, repositioning them in their place: on the side of a strong man, whether a brother, a husband or a son. The hetero-normative view is also reinforced by the wholly unnecessary narrative of the romance between the good king and the rebellious fiancé. As Oliveira (2018) observes, 'Shuri - the good king's sister - represents the jumpy joviality of the scientific ideal, but without mention the relations between race and science (and, I would add gender) in the century'. This issue is not even raised through the use of bitter and subtle irony, as is the case throughout the film, for example, in the phrases uttered by some of the characters in the film such as '[i]t is not magic, it is science'; 'the wig is a disgrace'; and 'we do not eat you, we are vegetarians'.

The movie is organised entirely through the right/wrong polarisation embedded not only through the two main black characters, but also by the two white co-adjutant characters. This polarisation is strategically used to leave the viewer constantly in a dubious position, functional to the development of the film's plot. Equally, at the very beginning of the film, the photo of Huey Newton, one of the founding leaders of the Black Panther Party (BPP), is visible in the apartment of the future panther/villain's father, seeming to suggest his closeness (and implied closeness with the BPP) to the "bad side" of the story. The true revelation should therefore be at the beginning of the film, where the one represented as the villain for the duration of the movie, is rescued in one of the last scenes, reminiscent of imagery of Christian redemption. The indecision of the viewer is mirrored by that of the hero/good panther, attending to the following interests of the movie: leaving everything in its place, not revolutionising anything, and thus fulfils its pacifying role in a particularly tense context like the one of the United States in 2018. The true revolutionary continues to die, like his enslaved ancestors, while the black community around the world, diasporic and not, exult at being represented by a black hero, a symbol of prosperous negritude, embedded in all the neoliberal values proper to the American Empire. As Zizek (2018) says, 'with T'Challa leading the helm, todays powerful can continue to sleep in peace'. Actually the film, far from being revolutionary, is not only not challenging, but also de-characterising the figure of the revolutionist, delegitimising, in a tortuous way, what the Black Panther Party really was (Almeida 2018). It is important, therefore, to keep alive an awareness about the appropriation of social struggles by the Hollywood cultural industry that, through manipulation, generates a cultural domination that allows the maintenance of its market and its ideological power.

Attempting an Afro-Brazilian reading

If, according to Kenya Freitas (2018), 'Black Panther is a north American black film about an imaginary country in Africa, representing a north American radical afro-diasporic perspective', it is important to undertake a film analysis according to a reading that lies within the Afro-Brazilian context. Regarding the black representation in the Brazilian audio-visual, the situation is not different from the one denounced in North America. A survey by the Brazilian National Cinema Agency - Ancine, launched in January 2018, shows that only 7% of film professionals in the country are black, evidencing unequivocal data on the extreme racial economic disparity within the sector.6

The issue of black representation in Brazilian cinema was the subject of a fierce debate a few months before the release of Black Panther, in October 2017, at the launch of the film Vazante. The movie by a white director, Daniela Thomas, portrays slavery in Brazil through the eyes of a 12-year-old white girl.7 The film was, in my opinion, rightly criticised for subjugating the black protagonists to mere movie extras, without voice, nor subjectivity of their own, simply an enslaved black mass. Contrarily, as demonstrated by the commentaries of most of the black people presented in the first part of this article, Black Panther evidences the empowerment given through cinematic representativeness. It spreads an urgent need to "take over the territories" and to call for collective action, to ensure that this moment is not temporary, as stated in the comments to Gongalves' article. In recent years, the Afro-Brazilian community has increasingly taken up voice and denounced the existing, but denied and hidden, racism in the country. A young man goes so far as to say, '[i]t is dangerous to be black in Brazil', alluding to the murder rate of young black men owing to police violence. South Africa and Brazil have many trajectories in common. Brazil was the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery in 1888, and had a military dictatorship that ended in 1985. Similarly, the South African apartheid regime ended in 1994. The two, therefore, began their processes of democratisation in neighbouring years, dealing with the highest rates of racial economic inequality in the world. Boaventura Santos (2003), whose text Between Prospero and Caliban: Colonialism, Post-Colonialism and Interidentity mobilised the discourse on post-colonial studies in Portuguese, argues that, in the Anglo-Saxon colonisation, the relation between coloniser and colonised is a relation of polarisation, unlike the Portuguese colonisation which is based on the practice of miscegenation. For the English coloniser, the other simply does not exist. Portuguese colonialism, on the contrary, is based on the ambiguous practice of miscegenation, which, while it does not produce less racist forms of coexistence, allows 'the other, colonized by the colonizer, to be not completely different. There are two that neither come together, nor separate, only interfere in the impact of each other on the identity definition of the colonizer and the colonized' (Santos 2003:27). On this different organisation lies one of the main divergences regarding the manifestation of racism in the two countries: if in South Africa it is clearly stated, in Brazil it is hypocritically hidden. Owing to these reasons, it is not surprising that the film has been received positively, especially within the context of the urgent need, by the Brazilian black movement, of taking up voice.

On one hand, the film undoubtedly generates positive effects on the self-esteem of children, as well as adults, who finally see themselves as protagonists of a good story. On the other hand, the answer to any criticism of the film is: 'the film is a marvel superhero, and as such, we cannot expect it provides any in-depth socio-political analysis'. This type of response, highly diffused among the public, becomes problematic in denying the socio-political role of entertainment produced in the United States, which, owing to its incomparable possibilities of funds, media, technologies and visibility, has a global effect. The spectacularity of costumes, scenery and special effects seems to confirm Debord's (2003:17) thought that 'the spectacle presents itself as grandiose, positive, indisputable and inaccessible. Its only message is 'what appears is good, what is good appears'. The attitude that it requires, in principle, is one of passive acceptance which, in fact, it has already obtained, insofar as it appears without reply, led by its monopoly of appearance'. As in the Situationist framework, the final effect of Black Panther is to silence the viewer. I cannot deny, for example, that I wasn't personally dazzled by the scenery and the costumes, and that this magnificence had contributed to a misinterpretation of first impressions regarding the role attributed to women and their representation. This silencing effect is also echoed in the statement that 'Black films also deserve large budgets'. There is no doubt about the legitimacy of this demand, but the question remains whether the magnificence of appearance is sufficiently responsive to the urgent demands of black women and men around the world. The uncritical reception by some parts of the black movement and the lack, in most cases, of a more politically complex response, is surprising. Rhaysa Ruas, a militant researcher and black lawyer, shared the following sentiment: 'see the comments on the internet, especially by our 'black movement' clapping the film, made me sick. Depressive. We are dying and they are applauding to this. So much struggle, to end applauding this. I was so devastated that I stopped writing and express my thoughts about it'.

Another positive aspect was the fact that the film offered a useful instrument to be used by teachers in classrooms to address racial issues in Brazil. The article 5 ways of talking about "Black Panther" in your class (Peres 2018) lists at least five subjects that can be introduced and discussed in middle and high school classroom: one, African myths and respect for ancestry; two, African reigns; three, the strength of women; four, African colonisation in the nineteen century; and, five, black movement:

self-preservation or armed struggle? Unfortunately, although the initiative is appreciable, it also provides a clear example of the North American entertainment industry's ability to direct thought, at the same time emphasising the Brazilian urgency of deepening its own discourse on race and diaspora. The ambiguous polarisation between right/ wrong, reinforced opportunistically in the film, is reproduced in the way the article suggests one should treat the black movement topic. Martin Luther King (MLK) and Malcolm X's (MX) divergent approaches are highlighted by the use of a question mark in the title 'self-preservation or armed struggle?'. The article states, '[w]hile MLK was a pastor and sought dialogue with the institutions that oppressed blacks in the 1960s, MX had a more extreme view and believed that white supremacy should end through direct conflict'. The polarisation between hero/villain and right/wrong continues. I believe it would be more challenging to raise a classroom debate that contextualises rather than pacifies MLK's vision, recalling one of his iconic phrases pronounced in 1966 in an interview with Mike Wallace: 'Riot is the language of the unheard', but also the contemporary oppression of black people. Agreeing that Black Panther is a North American black film, about an imaginary country in Africa, representing a North American Afro-Diasporic perspective, what impresses is the lack of an autonomous appropriation by a Brazilian diasporic voice and view. For example, by relating this topic to the police brutality and the mortality index that characterises the treatment of the black population in both the United States and Brazil.

Oliveira (2018) remarks how the 'vastness of the diaspora is replaced by a univocal view'. He denounces the lack of religious diversity, making specific references to the Candomblé, an Afro-Brazilian religious tradition originating in Salvador, Bahia at the beginning of the nineteenth century.8 He argues, 'there is no Exu, nor Elegbara ("the force's owner" in the Bantu ontology, present in umbanda and quimbanda), much less elements derived from the jeje-nago cultural complex [...] there is no Babalaös ("the secret's father"), the readers of the oracle of Ifá were replaced by a priest'. There is a lack of any reference to knowledge transmitted by oral communication and the characteristic griots of Mali and Ghana were dispensed. There is no food sharing, or communion ritual. The only collective actions presented in the movie are violent, choreographed battles, subject to the logic of a winning masculinity that, again, reinforces the polarity between the winner and the loser.

The notion of time is completely western, giving no room for any possibility of recovering other afro-descendent temporalities. To conclude: 'In the game of representations proposed by Black Panther, the majority perspective massacres the minority' (Oliveira 2018). The question by Hannah Beachler, costume designer of the movie, who asks: 'What it means to be African and how, being African Americans, can we identify ourselves? How do we connect?' (Interview with Bruney 2018), shows the dilemma that Afro-descendants share around the world. The issue is not so much that the movie offers a univocal vision, framed in the north American society, rather that the non-north American afro-descendants appropriate it, as if it were theirs. There is widespread enthusiasm amongst the global black community regarding the fact that Wakanda and the movie itself, offer a place where blacks have the possibility to "just exist", and not exist in relation to a white ontological social violence. However, what does this 'Afrofuturist Eden', as defined by Bruney (2018), represent and offer?

Wakanda is an African country that was able to avoid European colonisation and became one of the most developed on the continent, embodying African modernity. At the same time, Wakanda is a romantic kingdom of extremely closed warrior kings, whose richness comes from a mineral. These elements demonstrate the lack of space in Wakanda, for a different project. The future/modernity binomial gives continuity to a perception of history as linear, progressive, cumulative; where progress, development and fundamentally richness, become two sides of the same western modernity. There is no way for a rhizomatic modernity, different from the one derived or counterfeited from a Euro-American origin. Alternatively, a multiple modernity is one that demands to be apprehended and directed in its own right (Comaroff & Comaroff 2012) and that originates from the recognition of the uniqueness of history, and "other" individuality. On the contrary, reference to a tribal vision of Africa perpetuates a vision that is halfway between the romanticism of the 'sense of community', and the primitive state to which African society must be relegated. To crown this distortion, the reference to a mining economy reproduces exactly the same organisation of the extractive colonial economy, even going as far as the racist power relations. This racism reverberates in the words of the bald warrior's boyfriend when he states that 'by opening our borders to the refugees, we will bring their problems into the kingdom'. The use of the word 'refugees', in a world like the current one, affected by several crises of humanitarian exodus (into the Mediterranean Sea but also at the border of the USA) cannot go unnoticed. The division between us/others on the basis of colonialist thought becomes clear. The possibility of imagining a different black future, vastly different and legitimated by Afrofuturism, is completely lost. Rather than being interested in contributing to a black unity, Marvel's Black Panther seems to be interested in reinforcing the dominance of US cultural imperialism, be it white or non-white, operating for the interests of the market (Fagundes 2018) to sell to any potential consumer, whether white or black. Black Panther's Afrofuturist vision does nothing more than replicate the current global value system, simply reversing the colours of the skin of the power holders. Thus, it becomes important to remember what Steve Biko (1978:48) defines as black consciousness:

Being black is not a matter of pigmentation. Being black is a reflection of a mental attitude [...] The fact we are all not white does not necessary mean we are all black. Non-whites do exist and will continue to exist for quite a long time. If one's aspiration is whiteness but his pigmentation makes attainment of this impossible, that that person is a non-white.

The phrase is mirrored in the poem Negros by Solano Trindade, among the founders of the first Afro-Brazilian congress in 1934, who, as remembered by Deley (1961:61), states, 'Blacks who enslave and sell blacks in Africa are not my brothers. Black lords in America in the service of capital are not my brothers'.

In conclusion I would like to situate my criticism of the film into two wider critical discourses. The first, regarding the appropriation of social struggles by the cultural industry. The second, the suspicious renewed interest in the African continent in order to satisfy the need of capital to continuously find new frontiers of accumulation (from raw resources to subjectivities). As a result of the present rediscovery of the African continent, not only in Brazil, and of which Black Panther represents just one manifestation, we must keep alive that critical reflection that Oliveira (2018) describes so well (I would say, by cognitive capitalism):

Africa, it does not exist properly, is more a strategic myth, reiterated by privileged intellectuals of the academic jet-set and run by an entertainment empire that uses the tensions of the moment to spread the exaltation of the forces of war, bureaucracy and science run by corporate capitalism.

As Almeida (2018) remarks,

blacks started to identify themselves with their history, they become proud of their physical traits, their culture and they fight against racism, which is a very positive movement. However, the goal of the cultural industry is make profit, and cultural expressions and social struggles often become attractive to anyone who knows how to spot market trends.

There is no intention in this article to dismantle this movement. On the contrary, it is about demanding a reparation process proportional to the gravity of the injustices suffered and that continue to be perpetrated.

Thereafter, Kobena Mercer (quoted in Eshun 2004), comparing the work of the Black Audio Film Collective (active in the eighties) with that of young successful black artists of the 1990s, declares that 'younger artists no longer feel responsible for a blackness that is itself increasingly hypervisible in the global market of multicultural commodity fetishism. [...] Artists today evince a coy slipperiness of address, aesthetic, and self-fashioning, an elusive approach that can be understood as a protective response' (Eshun 2004:39) to "diversity increasingly administered as a social and cultural norm in postmodernity (Mercer 2000:57)".

In this respect, the definition of Afrofuturism proposed by Mark Dery becomes delicate. He argues that Afrofuturisms are 'speculative fictions that address African-American themes and African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century techno-culture' (Dery 1994:180). Its origin is bound to the American context but comes, over the last 20 years, from a widening black diasporic interpretation worldwide.

The emersion of the Afrofuturism concept into the Brazilian context reveals some difficulties owing to, on one hand, the fact that the term is still reserved for an academic and artistic niche audience; and, on the other hand, owing to the voguish nature of the term. In my opinion, it needs a critical theoretical deepening, as well as a translation, owing to the scarcity of Portuguese literature, in order to make it more accessible.9A number of instances show how the term can be used in a simplistic way. Artists define themselves (or are being defined) as Afro-Futurists, without an appropriation of the term that goes beyond the current fad of the moment. Some examples of definitions by Brazilian artists include: 'Afrofuturism is freedom of expression.10 This idea of futurism (...) we are trying to touch what we do not know' (Vasconcellos);

'Afrofuturismo, which I think is very important. It is the past, the present and the future: what came from the ancestors, what is happening now that will reflect in the future' (BNegâo); 'I have been studying Afrofuturism for four years and I am thinking of how to bring this entire universe to the surface. I am an inheritance, a descendent and a promise of this lineage. In the album, we stroll through the traditional, Afro-Brazilian rhythms' (Oléria); 'It starts with hip-hop, discovers funk, soul, jazz, Brazilian and Jamaican things. A lot of stuff. At the end all these references refer to Africa' (Mamelo Sound System). In the use of the term, there appears to be a willingness to participate in a global contemporary media movement, making extensive use of modernising imagery of black representation.

The urgency of this deepening is directly linked to the promotion of a critical position in relation to the mythical vision of a unified Africa, especially coming from outsider visions. This has already been demystified by some issues presented in this article by linking the definition of multiple diasporic identities and the relation between tradition/ modernity implicit into the concept of Afrofuturism. The vision of a united Africa, often idealised - especially by the diasporic black movement - through the use of Pan-Africanism as one of the political-intellectual paradigms that dominate the African discourse, must be revisited. Referring to the effect of the maintenance of this paradigm in a world in transformation, Mbembe (2015:68) affirms,

These distances between the real life of societies, on the one hand, and the intellectual tools by which societies apprehend their fate, on the other, imply risks for the thought and for culture [...] In addition, they block any form of renewal of cultural criticism and artistic and philosophical creativity, besides they reduce our ability to contribute to contemporary reflection on culture and democracy.

We can transfer this alert to the kind of black future that Black Panther wants to promote. Following Mbembe's definition of Afropolitanism, a concept in contrast with Pan-Africanism and associated with Afrofuturism, looking at who would be the depository of this black future, Mbembe (2007) states that 'this "open spirit" (the becoming-black of the world ) is perceived even more profoundly among many artists, musicians and composers, writers, poets, painters - workers of the spirit - who awaken from the depths of the post-colonial night'.

Afrofuturism, a claimed black future, therefore, seems to be in the hands of a small intellectual elite who, according to the author 'are fortunate enough to have had the experience of several worlds and have practically never ceased to come and go' (Mbembe 2015:71). We are far from the reality of the majority of black people in the world, diasporic or not. The reference to a black future becomes only a symbolic value to which the market appeals as an infinite field of exploration offered by the cultural industry, confirming 'culture (and I would add entertainment) is expanding, like never before, into the political and economic spheres' (Yúdice 2013:34). The result is the economic empowerment of a minority of the black population, and the maintenance of the exclusion of the black majority within a world organised around the supremacy of white values and the reinforcement of new forms of exploitation.

Conclusion

I believe that the main service Black Panther provides to the Brazilian audience is to point out the need to reinforce the discourse on African diaspora and the autonomy of Afro-Brazilian identity. It can also offer a starting point for critical reflection on the link between renewed interest in the African continent, and issues linked to cognitive capitalism and cultural appropriation. Through the deepening of this type of analyses, the aforementioned film may become an instrument to strengthen the struggles of the black Brazilian population. Consistent with the alert that Cesaire (1971:26) already launched, that 'the great historic drama of Africa was less that it has only tardily been put in contact with the rest of the world, but rather the manner it has been done'. It becomes crucial, from an empowered afro diasporic perspective, within the contemporary economic power relations, to challenge a distorted view of development and modernity. This view seems to lead to a normative assimilation of aesthetic concepts and subjectivities, functional to the new cognitive capitalism and favourable only to its beneficiaries (Burocco 2018).

Terms such as Afropolitanism and Afrofuturism cannot be received as neutral terms, without contextualising them in a larger discourse on positive and negative responses, or by electing some references as the sole bearers of knowledge. I am referring, for example, to the extended debates around Afropolitanism/cosmopolitanism introduced by Selasi (2005) to Mbembe (2007) and the almost unique translation of some authors. The uncritical reception of Black Panther by some parts of the Afro-Brazilian black movement and the lack, in most cases, of the articulation of a politically more complex response, shows the decolonisation of knowledge and thought requires serious commitment with an enlargement of clarification that can fortify a critical discourse. As seen in the analysis for this article, the absence of translation of texts into Portuguese, for example, confirms the academic English-speaking imperialism and proves to be a problem for decolonial practices. It allows some of the most fashionable authors, who Oliviera (2018) calls 'academic jet set[ters]' to become the only voice heard. This is owing to the absence of tools that can sustain a critical reception. If there is no doubt about the need and the urgency to spread the attention about decolonial issues, and the denunciation against white and Eurocentric ideologies, we must be careful that this decolonial turn does not legitimise the reproduction of similar unbalanced power relations. To conclude, this article emerged from the spread of new economies of services and knowledge into post-colonial societies that are still strongly marked by economic and racial inequalities. As well as the renewed interest shown by African and African diasporic cultural investors, which lead us to remark on the need to pay attention to the silencer effect of the show machine, especially when the economic and symbolic forces brought into play are largely unbalanced and ambiguous.

Notes

1 . The list of questions can be found in Appendix A.

2 . See Greenwald 2018.

3 . Literally translated as 'take a little walk'.

4 . Examples of some of the comments include:'Exotic is to And exotic the non-exotic. Could you understand?'; 'The person begins to read the article with eyes full of tears. It is so good to see our peeps gaining space, even if it is in homeopathic doses, but one day we get there'; 'Very excited. We know that these homeopathic doses are very visible. But we will also get there, yes, we are occupying everything. Now the world will not hold us!'; 'Very happy for the actions and representations!! UBUNTU!'; 'Very happy to see our community embraced. This union and this empowerment must be around everything. We have to take advantage of this moment to occupy more spaces. We cannot let this feeling go by with the film's debut, but rather take this opportunity to gain more strength'; 'Yes, we need to talk about it, unfortunately, it is dangerous to be black in Brazil, either in the ghetto or in the inner city'; 'We left the theater with great pride of being black. Beautiful, exciting'.

5 . See Machado (2017).

6 . See Ancine (Agência Nacional do Cinema) 2018: presents a study on gender and race diversity in the audio-visual market.

7 . See Genestreti and Almeida (2017).

8 . Candomblé is an Afro-Brazilian religious tradition originated in Salvador, Bahia at the beginning of the nineteenth century, developed in a creolisation of traditional Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu beliefs. As an oral tradition, it does not have holy scriptures. Music and dance are important parts of Candomblé ceremonies, since the dances enable worshippers to become possessed by the orishas. In the rituals, participants make offerings like minerals, vegetables, and animals. Candomblé does not include the duality of good and evil; each person is required to fulfil their destiny to the fullest, regardless of what that is.

9 . Among some texts: the movie review catalogue: Afrofuturismo: Cinema e Música em uma Diáspora Intergaláctica (Afrofuturismo: cinema and music in an intergalactic diaspora), available online: http://www.mostraafrofuturismo.com.br/catalogo; the article by Kênia Freitas and José Messias, O futuro será negro ou näo será: Afrofuturismo versus Afropessimismo as distopias do presente (Or future will be black: Afrofuturismo versus Afropessimism - as dystopias), which is available online at: http://www.asaeca.org/imagofagia/index.php/imagofagia/article/view/1535; and the catalogue of the cinematographic review "The cinema of John Akomfrah", available online at: http://mostraakomfrah.com.br/Akomfrah_atalogo.pdf

10 . See: Ocupagäo Afro Futurista em Salvador (Occupation Afro Futurista - Salvador), available online at: https://www.terra.com.br/noticias/dino/ocupacao-afro-futurista-reune-em-salvador-protagonistas-brasileiros-e-estrangeiros-nos-segmentos-de-tecnologia-arte-e-empreendedorismo,ca83af527b9e54f5d6b8f12236717a48ci2qttyb.html. Also: Afrofuturismo: um movimento social, artístico eprincipalmente cultural (Afrofutourism: a social, artistic and mainly cultural movement), available online at: https://social.shorthand.com/mgramigna4L/3y7J9FilaY/afrofuturismo. Examples of Afro-Brazilian artists found in the media, such as: Naná Vasconcelos; Ellen Oléria; BNegão; Mamelo Sound System; Zaika dos Santos; Senzala Hi-Tech (music); Adirley Queirós (cinema); Fábio Kabral (literature); o Grupo da Página Afrofuturista, on Facebook.

REFERENCES

Almeida, E. 2018. "Pantera Negra" e o partido Panteras Negras ("Black Panther" and the Black Panther Party). [O]. Available: https://esquerdaonline.com.br/2018/02/28/pantera-negra-e-o-partido-panteras-negras/ Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Amaral Cardoso, J. 2018. "Black Panther", filme de super-heróis esplendidamente negro ("Black Panther", splendidly black superhero movie). [O]. Available: https://www.publico.pt/2018/02/14/culturaipsilon/noticia/black-panther-1802877 Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Ancine (Agência Nacional do Cinema). 2018. Presents study on gender and race diversity in the audiovisual market. [O]. Available: https://www.ancine.gov.br/sites/default/files/apresentacoes/Apresentragao%20Divers idade%20FINAL%20EM%2025-01-18%20HOJE.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Anonymous. 2018. Facebook. [O]. Available: https://www.facebook.com/ Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Arendt, H. 2013. La banalitk del male. Eichmann a Gerusalemme (The banality of evil. Eichmann in Jerusalem). Italy: Feltrinelli Milano. [ Links ]

Biko, S.1978. I write what I like. Johannesburg: Heinnemann. [ Links ]

Boaventura de Sousa, S. 2003. Entre Próspero e Caliban: colonialismo, pós-colonialismo e interidentidade (Between Prospero and Caliban. Colonialism, postcolonialism and inter-identity). Novos Estudos 66:23-52. [ Links ]

Bruney, G. 2018. Conhega a mulher por trás da utopia Africana em "Pantera Negra" (Meet the woman behind the African utopia in "Black Panther"). [O]. Available: https://www.vice.com/pt_br/article/3k7aj9/conheca-a-mulher-por-tras-da-utopia-africana-em-pantera-negra Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Burocco, L. 2018. Creative hubs of coloniality in the South. Thesis (Doctorate in Technology of Communication and Esthetic). School of Communication, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

Burocco L. 2019. Não torne a Africa um objeto de exploração novamente. Revista Vazantes, 3(1):[s.p. [ Links ]].

Césaire, A. 1971. Discurso sobre o colonialismo, cadernos para o dialogo, porto (Discourse on colonialism. Notebooks for dialogue). Lisbon: Poveira. [ Links ]

Comaroff, J, & Comaroff, JL. 2015. Theory from the South: or, how Euro-America is evolving toward Africa. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cunha, DW. 2018. Facebook. [O]. Available: https://www.facebook.com/ Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Deleuze G, & Guattari, F. 1987. Tratado de nomadologia: a máquina de guerra, em Mil platós: capitalism e esquizofrenia (Treaty of nomadology: the war machine, in A thousand plateaus: capitalism and schizophrenia), edited by G Deleuze & F Guattari. Volume 5. Rio de Janeiro: Ed:11 -110. [ Links ]

Dery, M. 1994. Black to the future: interviews with Samuel R Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose, in Flame wars: the discourse of cyberculture, edited by M Dery. Durham: Duke University Press:735-78. [ Links ]

Eshun, K. 2004. Untimely meditations: reflections on the black audio film collective. Journal of Contemporary African Art 19: 38-45. [O]. Available: http://www.essayfilmfestival.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/19.eshun_.pdf Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Freitas, K. 2018. A ancestralidade futurista de "Pantera Negra" (The "Black Panther" futuristic ancestry). [O]. Available: https://www.revistacontinente.com.br/secoes/critica/a-ancestralidade-futurista-de-pantera-negra Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Genestreti, G & Almeida, MR. 2017. 'Vazante', film about slavery in Brazil, becomes a target of criticism. Folha de S. Paulo. [O]. Available: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2017/10/1926283-vazante-filme-sobrea-escravidao-no-brasil-vira-alvo-de-criticas.shtml Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Greenwald, G. 2018. Marielle Franco: why my friend was a repository of hope and a voice for Brazil's voiceless, before her devastating assassination. Independent. [O]. Available: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/marielle-franco-death-dead-dies-brazil-assassination-rio-de-janeiro-protest-glenn-greenwald-a8259516.html. Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Gongalves, J. 2018. "Pantera Negra" leva "publico exótico" ao Shopping Leblon („Black Panther" takes „exotic audience" to shopping leblon). [O]. Available: https://www.geledes.org.br/pantera-negra-leva-publico-exotico-ao-shopping-leblon/ Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Lazzarato, M & Negri, A. 2001. Trabalho Imaterial: formas de vida e produgâo de subjetividade (Intangible work: forms of life and production of subjectivity). Rio de Janeiro: DP&A. [ Links ]

Machado, 2017. The day in which Dorival faced the guard: police, racism and the banality of evil in Brazil (O dia em que Dorival encarou a guarda: polícia, racismo e a banalidade do mal no Brasil). [O]. Available: https://medium.com/o-sétimo-blog/o-dia-em-que-dorival-encarou-a-guarda-pol%C3%ADcia-racismo-e-a-banalidade-do-mal-no-brasil-f75a1b6667b Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

M bembe, A. 2018. "Pantera Negra": uma "nação negra" emerge ("Black Panther" a "black nation" emerges. [O]. Available: https://medium.com/@yasmimdeschain_4591/pantera-negra-uma-nagäo-negra-emerge-achille-mbembé-d3d8c3846ea1 Translated by Y Yonekura. Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Mbembe, A. 2007. Afropolitanism, in Africa remix: contemporary art of a continent, edited by S Njami & Durán. Johannesburg: Jacana Media: 26-30. Translated by Cleber Daniel Lambert da Silva, 2015, in Áskesis 4(2): 68-71. [ Links ] [O]. Mercer, K. 2000. Ethnicity and internationality: new British art and diaspora-based Blackness. Third Text 13(49):51-62. [ Links ]

Mignolo, W. 2011. The darker side of western modernity: global futures, decolonial options. Durham: Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Pantera Negra recebe onda de elogios e críticas positivas em sites (Black Panther receives praise and positive reviews on sites). 2018. The Globe. [O]. Available: https://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/filmes/pantera-negra-recebe-onda-de-elogios-criticas-positivas-em-sites-22373912 Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Oliveira, B. 2018. De que "negritude" se fala em Pantera Negra? (What blackness does Black Panther talk about"?). Feitigo sem Farofa, Revista Cinética. [O]. Available: http://revistacinetica.com.br/nova/feitico-sem-farofa/ Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Peres, P. 2018. 5 maneiras de falar sobre "Pantera Negra" na sua aula (5 ways to talk about "Black Panther" in your class). [O]. Available: https://novaescola.org.br/conteudo/10143/cinco-maneiras-de-falar-sobre-pantera-negra-na-sua-aula Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Quijano, A. 2000. Coloniality of power and social classification. Journal of World-systems Research 11(2):342-386. [ Links ]

Selasi, T. 2005. Bye-bye Babar. The Lip, March 3. [O]. Available: http://thelip.robertsharp.co.uk/?p=76 Accessed 25 April 2019. [ Links ]

Silva Fagundes, R. 2018. A apropriagäo das lutas sociais pela indústria cultural (The appropriation of social struggles by the cultural industry). Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil. [O]. Available: https://diplomatique.org.br/a-apropriacao-das-lutas-sociais-pela-industria-cultural/ Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

Trindade, S. 1961. Cantares ao meu povo (Sing to my people). São Paulo: Fulgor. [ Links ]

Yúdice, G. 2013. A conveniência da cultura: usos da cultura na era global (The convenience of culture: uses of culture in the global age). Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG. [ Links ]

Zizek, S. 2018. Dois panteras negras (Two black panthers). Blog da Boitempo. [O]. Available: https://blogdaboitempo.com.br/2018/02/27/zizek-dois-panteras-negras/. Accessed 19 August 2018. [ Links ]

https://www.facebook.com/vanderleydacunha.vanderley/posts/1566535026735788

I SAW THE BLACK PANTHER! WHAT I WOULD ASK TO KING T'CHALLA IF I REPRESENTED BRAZIL IN THE UN:

King T'Challa (Black Panther) ended his speech at the UN promising that Wakanda would undertake an international cooperation program putting its mineral wealth at the disposal of all the nations. He closed his speech by saying that the world is one tribe.

Before he left the pulpit a white sir, probably, a representative of some European country makes a question: what a nation of farmers can do for the world? King T'Challa makes an ironic face and the film ends.

If I were a representative of Brazil at the UN and I was there during his speech, I would have some questions. For example:

• Why did not Wakanda first choose to help the countries of Africa that are suffering for misery and wars? There are millions of people in the continent dying of hunger and AIDS.

• Since vibranium is used to cure serious diseases, why does Wakanda not use it to heal hundreds of millions of Africans from AIDS, Ebola, and Cholera?

• Why does Wakanda not use his military power to end wars in Africa, defeat Boko Haram and sweep Africa's dictatorships by helping these countries to have democratic and popular governments?

• Why does not Wakanda use its military power to compel the great colonial, and neo- colonial, and post-colonial powers to promote real reparation by returning to Africa all the material and cultural wealth plundered from Africa and the Americas during 400 years of slavery?

• What in the movie symbolizes your bastard brother? That every diasporic black is a bastard and not a real Afro-descendant?

• It is unlikely that Africans from southern Africa, where the kingdom of Wakanda is located, were brought to the United States as slaves. Why, then, to buy a building and create a super-equipped international center for black children and young people in an American ghetto, and not in Soweto, which should be closer to Wakanda than New York, or in Kinshasa/Congo, or Nairobi/Kenya?

• In the cartoon your sister tries to be one of the challengers to be the next black panther but she has been stuck, was not?

• So, does the Wakanda Kingdom is a macho patriarchy where women cannot reign and their destiny is only to be noble and coadjuvant servant?

(Por hora essas seriam as perguntas que gostaria de perguntar o rei T'Challa, se eu,como afrodescedente, fosse embaixador do Brasil na ONU).

These would be the questions I would like to ask to King T'Challa if, as an Afro-descendant, if I was at the UN as a Brazilian ambassador.

Or should I ask these questions to the film director, producer and screenwriters?