Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.32 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n32a14

ARTICLES

Black mirrors and zombies: the antinomy of distance in participatory spectatorship of smart phones

Landi Raubenheimer

Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. landir@uj.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Spectatorship has been investigated in film and media studies, aesthetics and art history, and has gained prominence from the 1990s with the focus on digital media. In this article, I investigate the implications of two notions of contemporary spectatorship for viewing moving images on smart phones, by studying how they are depicted in popular representations: television series, an advertisement and social media. The first notion is participation, with new technologies such as smart phones linked to supposedly more empowered participatory practices than those that preceded these technologies. The second notion is the cinema dispositive, which in current theory is often dismissed as leading to passive spectatorship. I aim to interrogate the complexity and contradictions inherent in both concepts and how they have recently been theorised in film and media studies, by focusing on two aspects that seem to facilitate participation through smart phones. The first is distance, where I investigate whether and how it is reconfigured as a factor that may feature in participatory spectator practices. The second is mobility, where I consider some limitations of the physical body-screen relationship between spectators and smart phones.

Keywords: Spectatorship, smart phones, participation, cinema dispositive, distance, mobility.

Introduction

With the advent of mobile media such as smart phones and tablets, as well as viewing practices influenced by the internet on platforms and channels such as YouTube and Netflix, there has been a need to research how spectators adapt their viewing practices to the new media (Christie 2012; Chateau & Moure 2015; Fossati & Van den Oever 2016; Greif, Hjorth, Lasén, Cobet-Maris 2011; Snickars & Vonderau 2012). This has particularly been in relation to established viewing regimes such as those found in cinema and television. An important question seems to be whether new practices depart dramatically from previous conventions. Do viewers still view moving images in manners based on the cinema dispositive, for example? Recent film and media theory considers how spectatorship has changed and how it may be theorised appropriately in terms of new mobile screen media. This question is not only concerned with the literal interpretation of how films, as moving image texts, are viewed in cinema theatres, but also the influence that notions such as the subject position have had on other viewing practices such as television and now newer forms of spectatorship of moving image texts, some of which allow for the recording of everyday life as such a text.

This article is a development of previous research where I focused on how interactivity and sensual effect simulated agency in zombie-like spectatorship of contemporary screen media in general (Raubenheimer 2013). In this article, I focus on smart phone spectatorship. I consider the manner in which contemplative distance is collapsed when events are experienced as image texts in the depictions under discussion. I also look at how mobility is imagined as less than realised when using phones in this manner, further employing the zombie metaphor. I draw on two science-fiction television series, an Apple iPhone advertisement, an Instagram photograph depicting people using smart phones, and the loading screen of the mobile phone game Pokémon Go (Niantic 2016). Hence, these include fictional and real depictions, which are understood as part of popular discourse on the use of phones. The texts provide an indication of some of the anxieties that accompany society's use and understanding of smart phones. The reader should also take note that this article is not a wholesale judgement of smart phone spectatorship and that the particular depictions of smart phones under discussion here portray and imagine only isolated aspects of how smart phones are used as viewing media; namely how spectators use phones to simultaneously view and record events, and how spectators move around while using their phones to do so. These aspects seem underacknowledged in current discourse on smart phones and considering them could contribute nuance and complexity to current theories.

Media theorists such as Ingrid Richardson and Larissa Hjorth (2011), Mark Hansen (2004) and Nanna Verhoeff (2012) have made important contributions to the field of media studies in arguing that mobility and embodiment allow digital and mobile media such as smart phones to empower spectators through a collapse of distance between the spectator and the screen, because mobile screens are hand-held and thus attached to the body.1 Film studies models of spectatorship that entail aspects of participation have furthermore often come to be framed in contrast to the passive cinematic model of spectatorship from apparatus theory2 (Metz 1977; Baudry 1974-75, 1976), which resembles the Cartesian subject position of aesthetics (Pierce 2012), and which relies on distance between spectator and screen. Film theorist Abraham Geil (2013:58-82) remarks on the tendency in film theory from the 1970s onwards, towards critical approaches that aim to subvert this passive, universal (and distanced) spectator figure.

Contemporary theories purport to refute the binary of active and passive, and often insist that spectatorship is varied, individualistic and dependent on socio-political factors, based on the work of Stuart Hall (1973), John Fiske and John Hartley (2003:120), and David Morley (1993), who wrote on now established media such as broadcast television. Previously, I referred to the broader developments in spectatorship as a practice across media, moving from a supposedly passive mode of spectatorship in cinema through the modernist notion of the death of the author and the decentering of the subject in postmodern thinking, allowing spectators to take on authorial roles and become more empowered in participatory spectatorship (Raubenheimer 2013; Oudshoorn & Pinch 2003:1-14). Along with these ideas around agency however, theories of subsequent media technologies such as smart phones seem to suggest a problematic technological determinism, implying that new technologies necessitate new forms of spectatorship, and that these are better than supposed older forms (Geil 2013). This could ironically reinforce the binary notion of spectatorship. In order to complicate the reductive binary, I pay close attention to how contradictory the notion of distance is in smart phone spectatorship. As a concept linked to supposedly older models such as cinema, I consider how and why different forms of distance might appear in participatory practices of smart phone spectatorship.3 I also consider the role of mobility as an aspect often linked to such practices. Distance in particular is a loaded concept in relation to film and spectatorship, and I refer to three different manners in which distance has been interpreted in relation to film. Walter Benjamin relates it to the experience of the aura of authenticity, which mass media technologies such as film destroy according to his interpretation of distance in the 1930s. In the 1970s, distance is not seen in this manner but in the physical and conceptual distance of the cinema dispositive, which necessitates a seemingly passive cinema experience. Newer forms of spectatorship are often posited in contrast to this passivity, as they seem to subvert or alter the cinema dispositive,4 but I argue that distance remains a factor in new configurations of spectatorship. I am not however implying that Benjamin's aesthetic distance is the same as the physical or conceptual spectatorial distance that was theorised in 1970s apparatus theory around the cinema, although in both a formulation of subjectivity is employed. Apparatus theory tended to demonise subjectivity (the subject position), but Jacques Rancière (2009) has suggested that regarding aesthetic experience in this manner is reductive and simplistic. Therefore, when I take issue with the purported participation engendered by smart phones I am not demonstrating that distance remains in order to suggest that this spectatorship is passive. Instead, I seek to complicate the notion of distance and the notion of mobility, in order to complicate spectatorship itself in relation to smart phones and moving image texts.

Black Mirror: a depiction of spectatorship of smart phones

Black Mirror5(2011-2017) is a science-fiction television series produced for Channel Four in the United Kingdom by Charlie Brooker, known as writer for Nathan Barley (2005) and as presenter for satirical review shows such as Screenwipe (2006). The series has four seasons (the last of which has recently been produced by Netflix) with three episodes each; the series explores screen media in a near-future context as well as how such technologies empower or disempower spectators and users. I focus here on one particular episode from season two, entitled White Bear6(Tibbets 2013). In the episode, two things strike me as important: first, the influence of established cinematic conventions on how spectators behave in the episode, and second, how much they resemble zombies, both of which are surprising in the light of recent theory on smart phones I mentioned above. This is all ironically set within the context of an apparently participatory mode of spectatorship in the episode, with the audience conflating the acts of viewing their phone screen and filming something. Pivotal to their behaviour is the seeming eradication of a spectatorial distance between the events and the spectators, and their bodily involvement in looking on.

In the episode, a woman named Victoria Skillane is depicted as the subject of a criminal justice system, which displays her for the entertainment of spectators in a theme park entitled White Bear Justice Park. She is unaware that she is the infamous star of a reality television show. She is drugged, violently hunted down and encounters spectators and actors who appear to either pursue or help her. She is also forced to look at footage of her crime, which involved filming her fiancé torturing and killing a little girl, although she seems to have no memory of this. At the end of the episode, the facts of her situation are revealed to her on a stage to the delight of the spectators who shout abuse at her.

The spectators depicted in the episode indeed seem zombie-like, interacting only with their phones. Victoria tries repeatedly to get them to respond, but it is as if there is an invisible barrier between them. One of the "characters" named Jem explains to her that the onlookers have been turned into passive observers by a signal broadcast via television, although this is not actually true, but part of a script.

Participation and the smart phone

How are smart phones in White Bear (WB) related specifically to participation then? Participation in various disciplines is founded upon the notion that spectators were not empowered by aesthetic formulations of subjectivity as they manifest in modern art, theatre and cinema. Theories of participation seek to rectify that by politically enabling the spectator. As I have mentioned above, this has broadly developed through the postmodern notion of the decentering of the subject. It is also currently theorised in relation to media convergence (Jenkins 2009), relational aesthetics7within the context of contemporary art (Bourriaud 2002), in the context of the so-called ethnographic turn in contemporary art-making (Siegenthaler 2013), as well as in its own right as an emerging field of study (Delwiche & Jacobs Henderson 2013:133). Participation lends itself to being an umbrella-term for many different iterations of spectatorship, but it seems too often used to herald "new" practices, and to highlight the differences between such practices and what came before.

In terms of mobile screen technologies, Hjorth and Richardson (2011:96-126) have argued that smart phones allow the spectator to challenge previous more static formulations of spectatorship, and Verhoeff (2012) has argued for a new mobile regime of navigation. Richardson (2010:1-15) has written about the manners in which previous formulations of spectatorship are changing with new technologies of looking. She calls for new theories to interpret how the body and the screen interact, arguing that older "regimes", such as that of the cinema do not apply to how users interact with mobile screens, such as smart phones. Much of her writing focuses on how mobile media enable the body to become part of the viewing experience, in effect subverting the static body (or in effect disembodied experience) of the cinema dispositive. Considering some of the yet unacknowledged tensions within such a theorising of mobility, I discuss the body-screen relationship briefly in the section on zombification below.

Verhoeff (2012) also focuses on mobility and proposes a new viewing regime of navigation, which she ascribes to mobile screen media. Her understanding of this is also of the mobility of the screen as something inherently different from regimes that precede mobile screens. Media theorist Hansen (2004) has made another notable addition to theorising mobile screens in his comprehensive account of digital media and its embodied character.

What these theories (and numerous others) have in common is their emphasis on the importance of the mobile body in these practices, and their assertion that this leads to "new" and "better" forms of spectatorship than the cinematic model. Most of these theories furthermore seem to construe spectatorship of mobile screens as loosely participatory, based on the potential of the media technology's material characteristics that relate to the body, such as it being hand held, mobile, and manipulable by touch screen. The symbolic and physical distance of the cinema dispositive is shattered when one can hold the screen oneself, watch a film text in any geographical location on one's phone, and have control over when to pause and play the text. One becomes an active participant in how the text is viewed (Odin 2012, 2016). In short, such a mode is more participatory than viewing broadcast television at home or seeing a film in the cinema. Despite the merit of such an argument, it seems to have given rise to the problematic notion that participation is always inherently more empowering as a mode of spectatorship than aesthetic formulations that predate it, such as the cinema.

Not all the discourse on participation is positive in outlook, however. Rancière (2009) has argued that the fundamental binary of supposed passivity and activity in aesthetic formulations of spectatorship needs to be reconsidered. Media critical theorists Aaron Delwiche and Jennifer Jacobs Henderson (2013:1-33) mention that it must even be considered whether participation may in fact cloak fundamental passivity in society. This question comes to the fore in WB, where participation is depicted in a critical manner rather than as a form of empowerment.

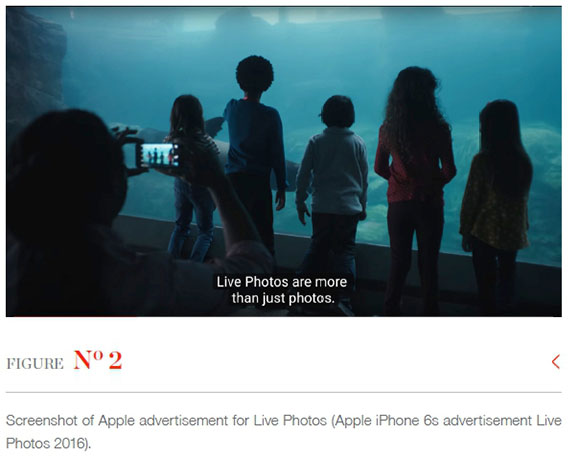

The episode presents a parody of various forms of participatory spectatorship; audience members inside a set as "actors", as well as audience members in a "play" where the stage is a theme park, audience members facing a stage where the "star" is presented for them to heckle and film, and a "set" which looks like a suburb, where televisions broadcast signals to influence the supposed population. In short, the theme park is like being inside of a television or film set, and the spectators freely wander around, able to take their own video footage or merely observe what they choose to. They appear to participate as they follow the character of Victoria around, but in effect observe her without response. Their phones play a large part in this as many of them look simultaneously at her, and at the recording of her on their phones. I have been wondering about this depiction of using one's phone to view the world. An example that illustrates this phenomenon is Apple's advertising campaign for the iPhone 6.

The antinomy of distance in the use of smart phones

On their website Apple claim that their iPhone 6 allows one to experience more of the world (Apple [sa]). The phone brings the world "closer" to viewers, through the Live Photos function. Live Photos are photographs that seem to move when viewed on the phone screen and are activated by a prolonged touch of one's finger.8 They are short bursts of video, which, because they are not static, seem more life-like than conventional photos taken on phones. Brief in duration, they are somewhere between photography and video, almost like GIFs.9 The manner in which the function is depicted in Apple's advertising campaign for the iPhone 6, however, relates to the way in which users already tend to employ many different smart phones; as filming and viewing devices of their everyday lives.

It is worthwhile here to refer to Walter Benjamin's (1936) formulation of distance in relation to film. For him, film and photography function primarily in collapsing the distance that is inherent in aesthetic experience of the world. On the other hand, he argues that one's experience of distance is also what lends an aesthetic experience authenticity. The further away something is, physically and temporally, the more authentic one's experience of it. Benjamin (1936) argues that film and photography disdain this function of aesthetics, and instead make things attainable through their mass representations in what he terms exhibition value. In fact, he says that authenticity (immediate reality) would become the rare 'blue flower in the land of technology' as he sees the future of film and photography in the 1930s (Benjamin 1936:804).

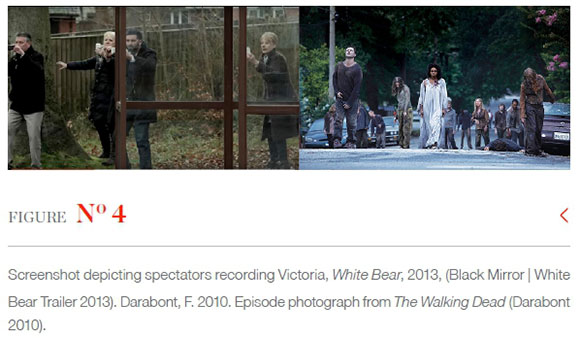

The Live Photos function seems to endorse the notion that the phone allows one to take part in one's life to a greater extent. One can bring experiences closer, and carry their record around, although one sacrifices the aura of authentic experience. Conflating filming and viewing is also evident in WB (Figure 1), highlighting the participatory nature of smart phones; in this instance, spectators are also videographers.10 They are each making their own film of the event, and are the authors of what they are watching in a manner that resembles the reformulation of authorial roles in the context of participation theories such as relational aesthetics (Bourriaud 2002). The spectators in WB perform this action quite naturally, echoing the now common practice at music or theatre performances, of watching the performance on one's phone while also recording it, such as captured by an audience member in a local bar in Johannesburg, as seen in Figure 3. The potential of every person with a phone also being a videographer has had some interesting implications that relate back to Benjamin's notion of authenticity. Over the past few years (2014-2017), musicians have been instituting bans on the use of smart phones at their concerts. Various international newspaper articles11 report how artists have banned the use of phones at their shows, because they felt that the audience was more focused on filming the concert than experiencing it in the moment. While in a postmodern sense "we" are now all potential authors of our own image texts, this seeming act of agency also implies a doubled role of merely looking on (Sontag 1977), or indeed the notion of the experience of reality as hyperreality and thus as a visual text has been taken to the extreme (Hart 2004:47-66).

Hyperreality is a postmodern concept that is used to explain the pictorial turn in literature, art and popular media. It is often related to Jean Baurdrillard's (1981) use of the term simulacrum, where images are so important in daily life that they compete with experiences. In other words, images of experiences are regarded in the same manner as the experiences themselves. Both images and experiences are regarded as equally "real". Theorists such as Guy Debord (1970), Baurdrillard (1981) and Paul Virilio (1998) have argued that this has in turn distanced people from their experiences, and resulted in a mediated society, where people behave towards reality as if they are spectators of it rather than experiencing it first-hand.

Distance here is thus twofold; one aspect of distance is its collapse, and has to do with the media technology of the smartphone. Using smart phones to view events collapses the "distance" between the event and its representation, and allows one to experience aspects of immersion in the medium. The second aspect of distance occurs in the process of viewing rather than a characteristic of the medium and how the spectator has to "step away" from the event in order to view it as a representation, which reinforces a distancing from the event. This is facilitated by the way spectators have to hold phones at eye level and at arm's length in order to record and view the event.

One of the most complex aspects of how the phone is conceived of in this context (by Apple and in WB) is thus that the smart phone paradoxically reinforces a material distance or dispositive of its own, while seeming to destroy Benjamin's auratic distance. Thus, there seems to be a fundamental antinomy that is played out in how distance in its various formulations becomes contradictory. While participation through mobile media allows ubiquitous access to experiences (through exhibition value), bringing them closer to the user, it seems that the phone needs to step between the spectator and the experience of the event, an interloper of sorts, which ironically cements the role of the spectator as one that does not participate in the experience, but instead watches in a participatory manner. Distance is collapsed in one sense and reinforced in another, constituting a complex contradiction in how distance itself is formulated in relation to the act.

The adult holding the phone in the iPhone advertisement is presumably filming his or her own children. While the children are experiencing a moment of spectatorship themselves, looking at the aquarium, the parent is making a "home video", taking Live Photos. One could argue that hand-held video cameras have allowed this since the 1970s with Super8 film (Sapio 2014:39-46), but the difference here is that smart phones are always with people, whereas home movies had to be planned in advance for special occasions, since the portable video camera was not always on hand. Furthermore, it is interesting that here the adult is watching the phone screen, and not the children. This indeed was also already facilitated with the viewfinders of early video cameras, but the ubiquity of this simultaneous viewing and recording gives the smart phone text a different character to home video. Here the act of watching itself is facilitated, and perhaps even necessitated by the phone. Very clear in this depiction is also the physical distance between the adult and the children. This is again not a new phenomenon in camera media, and has been theorised extensively in critical accounts of the gaze and of the violence of photography and film (Mulvey 1975:833844; Sontag 1977). The distancing effect imposed by smart phone spectatorship here is, however, always potentially available to transform one into a spectator of every banal event playing out in daily life. The advertisement implies furthermore, that viewing the world in this way is superior to just experiencing it. Juxtaposing a cat with a Live Photo of a cat, the matter of fact voice-over suggests that the depiction is obviously equal or even superior to the real cat. In some senses the world of banal experience now becomes one that has cinematic potential.12

The cinema dispositive and aesthetic formulations of spectatorship, an alternative to passive audiences

Why would I refer to cinematic potential and not the home video? Cinema is here regarded as the blue print for spectatorship; its well-theorised dispositive remains a point of comparison for understanding new forms of spectatorship (Geil 2013:53-82). Furthermore, the depiction of smart phone spectatorship in the iPhone advertisement has much in common with cinema. The viewer (the adult) is static in relation to what is depicted. The viewer remains at a set distance to the screen (here the distance may vary with one's arm length and whether one wants to move one's arm, but it remains limited by one's bodily limitations), and one has to intermittently withdraw from the event one is viewing, regarding it as potential text rather than "reality". This process is contradictory and seems characteristic of how complex or duplicitous the notion of distance is in smart phone spectatorship. While it seems that as a viewer, spectator or user of the phone one is more immersed within the "scene" one is viewing, one is less involved and becomes a bystander of sorts in the event itself. This dynamic may sound like the same functions performed by a videographer, however the implied purpose here is not only to record footage, but also to view a text as it is being made, and thus to be a spectator while also being a participant in the event to some extent. Of course, the advertisement suggests that one will view the Live Photos after the event, sentimentally bringing them to life with a touch of one's finger, but much of the advertisement depicts users recording the photographs, like the spectators viewing the performer do, as seen in Figure 3. While a physical distance associated with spectatorship is reinforced, Benjaminian distance in space is collapsed in "bringing" the experience into one's pocket, but time is also affected. Here the exhibition value of Live Photos not only collapses time in bringing the past into the present as one expects from photographs. In the simultaneous viewing of events while recording them, they are instead also immediately projected into the past. In treating the present as a finished image, text time is inverted. This aspect of using phones could be investigated further in relation to the notion of time and nostalgia, as Gil Bartholeyns (2014:51-67) and Elena Caoduro (2014:67-82) do in relation to digital photography, but I do not pursue this here.

In WB, the most obvious connection to cinema is an instruction sign shown towards the end of the episode. Presumably, this is shown to spectators when they arrive in the park. It instructs them to refrain from talking, to keep their distance and to enjoy themselves. This behaviour bears a strong resemblance to the cinematic dispositive of Hollywood cinema with the emphasis on distance remaining intact. Distance here is not the same as Benjamin's formulation of it in relation to authenticity, but rather the subsequent formulation from the 1970s, in apparatus theory's critique of cinematic spectatorship. The "cinematic dispositive" encourages specific behaviour for the spectator in the context of the cinema theatre. As Christian Metz (1977) and Jean-Louis Baudry (1974-75, 1976) wrote about it in the 1970s, it entails the darkness and static position of sitting in the cinema, facing a large elevated screen, so that spectators look up. This engenders a seemingly passive relationship between the spectators and the screen, and a distance and hierarchy between the screen and the bodies of the viewers. Furthermore, the editing of the film text itself shapes the experience by cueing audience response in predictable manners (Bordwell & Thompson 2010:223268). Many theorists have argued since that this configuration of the environment and the film text allows the spectator little agency.

The notion of cinematic spectatorship is thus easily reduced to this reading of the dispositive as a disempowering "subject position", especially in theories of spectatorship that favour participation as the "better" form of spectatorship (Geil 2013:55). Rancière (2009), however, argues for the revisiting of the aesthetic model of interpreting spectatorship. Though he deals with the more generalised realms of the theatre and art, he identifies seemingly corresponding debates in these fields, than Geil (2013:53) identifies in film studies. Geil (2013:53) argues in fact, that the critical approaches taken in film studies since the 1970s; feminist theories revising psychoanalysis, cultural studies approaches, cognitivist approaches, historicist reinterpretations of early cinema and phenomenological accounts of embodied viewing, all apply this thinking of favouring active, and therefore "better" spectatorship, instead of the "bad" passive spectatorship of the cinema dispositive. Geil (2013:55) furthermore interprets Ranciere's writing on spectatorship as an alternative to theories that aim to identify "better" and "worse" forms of viewing film. In terms of smart phones, this approach of "better" spectatorship seems to be most often concerned with participation (see Hjorth & Richardson 2011; Richardson 2010; Greif, Hjorth, Lasén, Cobet-Maris 2011; Snickars & Vonderau 2012).

In WB, diverse forms of spectatorship are shown as problematic, indicating that newer forms of spectatorship and new media technologies do share some aspects with the cinematic dispositive, most notably the imposition of a bodily (arm's length) distance between the spectator and the screen being viewed, or indeed the event being viewed. To my mind the contradictory aspect of distance, as something that is purportedly counter to agency, but yet remains in so-called participative practices in smart phone spectatorship, is at least indicative that aesthetic formulations, or the cinema dispositive may still influence how new technologies are thought of in popular discourse.

Zombification: the question of the mobile body in smart phone spectatorship

In order to problematise the notion of participation in relation to mobility, I now consider in which manners the spectators in WB are depicted as impeded by their use of phones. Richardson (2010:11-12) mentions the need for appropriate metaphors to describe this new relationship, and it seems that the metaphor of the zombie as counterpoint to more celebratory notions of mobility allows one to consider the often-disregarded problems inherent in the participatory model of smart phone spectatorship.

When considering WB, it is immediately noticeable that viewers in the show, as shown on the left in Figure 4, are unaware of their own behaviour as strange, as if it is the most natural thing in the world to observe a woman being hunted down. They indeed become onlookers, as Jem explains to Victoria in the trailer. The phones do not seem to bring them closer to acting upon the events they are watching, although they are physically close as "participatory" spectators.

The spectators in WB furthermore seem to be ambling along rather stuntedly. This seems to be because one cannot easily walk and look at one's phone screen at the same time. Many theories of how the smart phone is changing spectatorship for the better are premised upon the importance of mobility. This is owing to the fact that being mobile is an obvious and symbolic contrast with the static body required by the cinema dispositive. It is ironic that the phones in WB hinder spectator mobility, in some ways limiting their ability to participate in the show. The spectatorship they are performing accords with my suggestion that participation or mobility in itself, is not a guarantee of agency, simply because it appears different from the cinematic regime. Of course, embodiment is indeed a manner in which the contemplative and cerebral distance of the cinematic dispositive may be subverted,13 but this is not apparent in WB's satirical depiction.

Visible in the comparison between the still images in Figure 4 is to what extent spectators in WB resemble zombies in The Walking Dead, who aimlessly stumble onwards, automatically reacting to stimuli, and unable to consider their actions. They are immersed in the experience of the world as an image text through their physical attachment to their phones. These "zombies", colloquially referred to as "walkers" in The Walking Dead, also bring to mind the media theory term 'lurkers', used to refer to internet users who do not contribute to the creation of content but merely consume it (Fortunati 2011:23). This seems to address the inherent danger and violence in looking mindlessly. In WB, participation is depicted as indiscriminate mass consumption, and distance has mutated into a contradictory set of parameters. This distance is thus in contrast to what Rancière regards as the emancipatory potential in every spectator's experience, and in contrast to Benjamin's distance of the aura of authenticity, which can empower the spectator or result in an aesthetic experience.

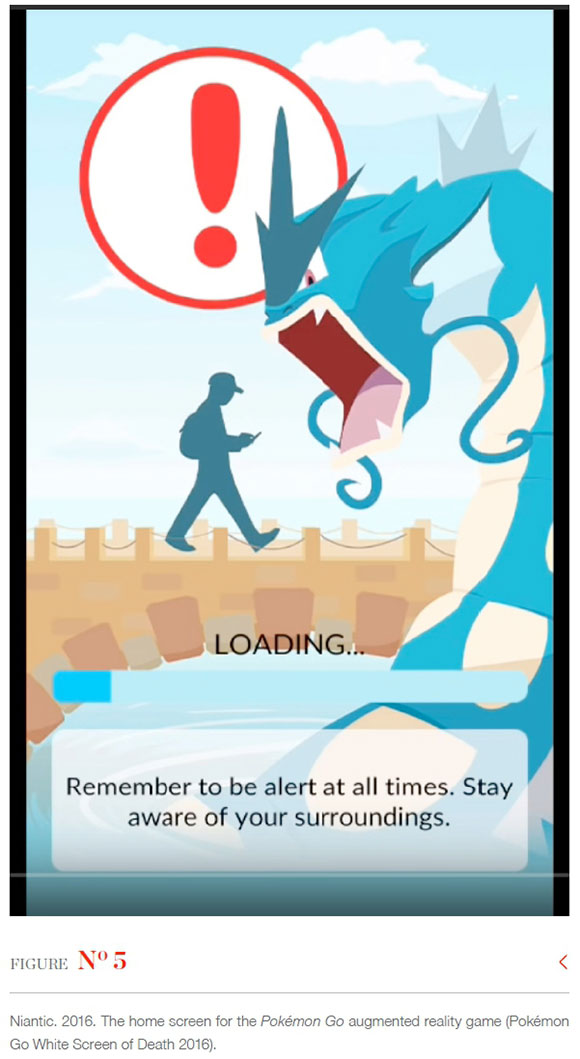

WB is a fictional depiction of how spectators behave, but do spectators of smart phones really act like zombies? The release of the augmented reality game Pokémon Go (Niantic 2016) sparked public debate along this line, as players of the game stopped traffic and caused large-scale accidents on the roads due to distractedly playing the game on their phones.14 It seems that the creators of the game are aware of the difficulties one may experience in looking at one's phone and walking around, as the loading screen of the game, visible in Figure 5, warns one to be aware of one's surroundings. The screen shows an unwitting player being stalked by a "Pokémon" he does not see, and also demonstrates how one could be unaware of one's surroundings if one is engaged in looking at the world through the screen. The posture of looking at one's phone means that one cannot look around without looking away from the screen, presenting the player with a fundamental paradox. One may agree that the embodiment (through mobility) of looking represented by the phone may be conceptually emancipatory through participation (an argument I have not engaged with in depth here), but it seems difficult to deny that pragmatically it also seems to restrict the spectator. This is echoed in the anxiety-ridden depictions of spectatorship in WB, where spectators seem to withdraw behind and into their phones.

Conclusion

Mobile screen media technologies have clearly posed a challenge for how spectatorship is understood in terms of the viewing of moving images. One of the main questions that I referred to here is whether spectatorship would depart dramatically from the cinematic model. Participation theory seems to indicate such a development, but I have questioned whether this is entirely the case. I have referred to Ranciere's thinking around spectatorship to question some of the premises upon which participation theory bases its claims, suggesting that perhaps the basic notions of active and passive spectatorship need to be reconsidered before concluding that we are indeed in a new era of emancipation through participatory practices. Instrumental to how spectatorship of smart phones may be understood are the notions of distance and mobility. Both of these factors are depicted in WB as problematic and unresolved, often resulting in spectatorship that not only resembles cinema in some regards in a reductively negative manner, but that seems to entirely refute the possibility of agency and emancipation. Rather than asserting that cinema does lead to passive spectatorship, however, I aimed here to complicate how spectatorship is understood in relation to new mobile screen technologies, and to pose the question of whether the cinematic dispositive may still contribute as a construct that informs how spectators use new technologies to view the world. The notions of distance and immobility, as they appear in the cinematic dispositive, seem to play a role rather than being completely irrelevant in the spectatorship of smart phones, and the exact terms of this interaction between cinema and contemporary spectatorship of new media technologies need to be investigated and complicated in order to develop theory's understanding of what smart phones mean for spectatorship.

REFERENCES

Apple iPhone 6s ad Live Photos 2016. [YouTube video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IBiZlFSs0-o&ab_channel=MozzaCreations Accessed 22 February 2018. [ Links ]

Ashcroft, B, Griffiths, G & Tiffin, H (eds). 2000. Postcolonial studies. They key concepts. Second edition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Bartholeyns, G. 2014. The instant past: nostalgia and digital retro photography, in Media and nostalgia. Yearning for the past, present and future, edited by K Niemeyer: 51-67. [ Links ]

Baudrillard, J. 1981. Simulacra and simulations, in The precession of simulacra, translated by SF Glaser. Michigan: University of Michigan Press:1-42. [ Links ]

Baudry, JL. 1976 (2004). The apparatus: metapsychological approaches to the impression of reality in cinema, in Film theory and criticism, edited by L Braudy & M Cohen. Oxford: Oxford University Press:207-239. [ Links ]

Baudry, JL. 1974-75 (2004). Ideological effects of the basic cinematographic apparatus, in Film theory and criticism, edited by L Braudy & M Cohen. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 355-365. [ Links ]

Benjamin, W. 2004 [1936]. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, in Film theory and criticism, edited by L Braudy & M Cohen. Oxford: Oxford University Press:791-811. [ Links ]

Bishop, C. 2006. Participation. Documents of contemporary art. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Bishop, C. 2005. Installation art. A critical history. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Black Mirror | White Bear Trailer [YouTube video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2spS4Lc3CM&ab_channel=Channel4 Accessed 22 February 2018. [ Links ]

Bourriaud, N. 2002. Relational aesthetics. Translated by S Pleasance, F Woods, M Copeland. Dijon: Les presses du réel. [ Links ]

Bordwell, D & Thompson, K (eds). 2010. Film art. An introduction. Wisconsin: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Borland, S. 2016. Don't Pokemon Go and drive! More than 110,000 road accidents in the US were caused by the game in just 10 days, Daily Mail Online 16 September [O]. Available http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3793050/Don-t-Pokemon-drive-110-000-road-accidents-caused-game-just-10-days.html Accessed on 13 March 2017. [ Links ]

Bowman, P (ed). 2013. Rancière and film (critical connections). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [ Links ]

Braudy, L & Cohen, M (eds). 2004. Film theory and criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Brown, K. 2014. Interactive contemporary art. Participation in practice. London: I. B. Tauris. [ Links ]

Brooker, C. prod. 2011-2017. Black Mirror, [Television series]. London: Zeppotron. [ Links ]

Caoduro, E. 2014. Photo filter apps: understanding analogue nostalgia in the new media ecology. Networking knowledge 7(2):67-82. [ Links ]

Chateau, D & Moure, J (eds). 2015. Screens. Key debates series no 6. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

Christie, I. 2012. Audiences. Defining and researching screen entertainment reception. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

Darabont, F. (prod). 2010. The walking dead, [Television programme]. New York: AMC Studios. [ Links ]

Darabont, F. (prod). 2010. Episode photographs from season 1 of The walking dead. Available: http://blogs.amctv.comthe-walking-deadphoto-galleriesthe-walking-dead-season-1-episode-photos#2 Accessed 23 March 2017. [ Links ]

Debord, G. 1970 [1967]. The society of the spectacle. Translated by D Nicholson-Smith. Kalamazoo: Black & Red. [ Links ]

Delwiche, A & Jacobs Henderson, J (eds). 2013. The participatory cultures handbook. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Driver convicted over fatal accident linked to 'Pokemon Go'. 2017. The Japan Times 17 January. [O]. Available: http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/01/17/national/crime-legal/driver-convicted-fatal-accident-linked-pokemon-go/#.WMZlDxKGPMV Accessed on 13 March 2017. [ Links ]

Fiske, J & Hartley, J. 2003 [1978]. Reading television. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Fortunati, L. 2011. Online participation and the new media, in Participation in broadband society volume 4: Cultures of participation: media practices, politics and literacy, edited by H Greif, L Hjorth, Lasén, C Cobet-Maris. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Europaischer Verlag der Wissenschaften:19-34. [ Links ]

Fossati, G & van den Oever, A. 2016. Exposing the film apparatus. The film archive as research laboratory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press/ EYE Filmmuseum. [ Links ]

Geil, A. 2013. The spectator without qualities, in Rancière and film (critical connections), edited by P Bowman. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press:58-82. [ Links ]

Greif, H, Hjorth, L, Lasén, A, Cobet-Maris, C (eds). 2011. Participation in broadband society volume 4: Cultures of participation: media practices, politics and literacy. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Europaischer Verlag der Wissenschaften. [ Links ]

GIF [sa]. Merriam-Webster dictionary [O]. Available: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/GIF Accessed 23 March 2017. [ Links ]

Hall, S. 1973. Encoding and decoding in the television discourse. Birmingham: University of Birmingham. [ Links ]

Hansen, M. 2004. New philosophy for new media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Hart, K. 2004. Postmodernism, a beginner's guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Hjorth, L & Richardson, I. 2011. Playing the waiting game: complicating notions of (tele) presence and gendered distraction in casual mobile gaming, in Participation in broadband society volume 4: Cultures of participation: media practices, politics and literacy, edited by H Greif, L Hjorth, Lasén, C Cobet-Maris. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Europaischer Verlag der Wissenschaften:96-126. [ Links ]

Hopton, A. 2016. Put that phone away! Locking cellphone pouch puts focus back on the live show. CBC News, Entertainment 14 November. [O]. Available: http://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/locking-cell-phones-yondr-concerts-comedy-school-1.3845465 Accessed 13 March 2017. [ Links ]

Inada, M. 2016. 'Pokémon Go'-Related Car Crash Kills Woman in Japan. The Wall Street Journal 25 August. [O]. Available: https://www.wsj.com/articles/woman-killed-in-pokemon-go-related-car-crash-in-japan-1472107854 Accessed 13 March 2017. [ Links ]

Jenkins, H. 2009. Convergence culture. Where old and new media collide. New York & London: New York University Press. [ Links ]

Lee. D. 2013. Should music fans stop filming gigs on their smartphones? BBC News, Technology 12 April. [O]. Available: http://www.bbc.com/news/technology-22113326 Accessed 13 March 2017. [ Links ]

Macu, M. 2016. Julian Gomes album launch, Kitcheners Carvery, Johannesburg, 14 August. [O]. Available: https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=1587781664580745&set=gm.552178338305641&type=3&theater Accessed 22 February 2018. [ Links ]

Metz, C. 1977. Psychoanalysis and cinema. The imaginary signifier. Translated by C Britton, A Williams, B Brewster & A Guzzetti. London: The Macmillan Press. [ Links ]

Morley, D. 1993. Television, audiences and cultural studies. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mulvey, L. 2004 [1975]. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema, in Film theory and criticism, edited by L Braudy & M Cohen. Oxford: Oxford University Press:833-844. [ Links ]

Niemeyer, K (ed). 2014. Media and nostalgia. Yearning for the past, present and future. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Odin, R. 2016. Cinema in my pocket, in Exposing the film apparatus. The film archive as research laboratory, edited by G Fossati & A van den Oever. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press/ EYE Filmmuseum:45-53. [ Links ]

Odin, R. 2012. Spectator, film and the mobile phone, in Audiences. Defining and researching screen entertainment reception, edited by I Christie. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press:155-169. [ Links ]

Owen, C. 2016. Apple has patented an infrared blocker to stop people taking pictures and videos at concerts. Wales Online 30 June. [O]. Available: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/wales-news/apple-patented-infrared-blocker-stop-11546478 Accessed 13 March 2017. [ Links ]

Pokémon Go White Screen Of Death. 2016 [YouTube video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4qBergR8B0Y&t=35s&ab_channel=playingparagonOG Accessed 22 February 2018. [ Links ]

Niantic (developer). 2016. Pokémon Go [game]. San Francisco. [ Links ]

Peirce, GB. 2012. The sublime today: contemporary readings in the aesthetic. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [ Links ]

Prince, S. 2011. Digital visual effects in cinema: the seduction of reality. London: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Ranciére, J. 2009. The emancipated spectator. London: Verso. [ Links ]

Richardson, I. 2010. Faces, interfaces, screens: relational ontologies of framing, attention and distraction. Transformations 18:1-15. [ Links ]

Sapio, G. 2014. Homesick for aged home movies: why do we shoot contemporary family videos in old-fashioned ways?, in Media and nostalgia. Yearning for the past, present and future, edited by K Niemeyer:39-50. [ Links ]

Siegenthaler, F. 2013. Towards an ethnographic turn in contemporary art scholarship. Critical Arts 27(6):737-752 [ Links ]

Snickars, P & Vonderau, P. 2012. Moving data. The iPhone and the future of media. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Solon, O. 2016. Put it away! Alicia Keys and other artists try device that locks up fans' phones. The Guardian UK, 20 June. [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/20/yondr-phone-free-cases-alicia-keys-concert Accessed 29 March 2017. [ Links ]

Sontag, S. 1977. On photography London: Penguin. [ Links ]

Tibbets, C. dir. 2013. White Bear. Black Mirror, episode 2, season 2, [Television programme]. London: Zeppotron. [ Links ]

Verhoeff, N. 2012. Mobile screens: the visual regime of navigation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

- Virilio, P. 1998. Open sky. London: Verso. [ Links ]

1 It should be noted that this is a very broad simplification of what each of these theorists have argued, the notion of embodiment as a subversion of problematic subjectivity and spectatorship does seem to be the common basis for many arguments that suggest that new media enables an "improved" spectatorship.

2 Apparatus theory became popular in the 1970s in film theory when Jean-Louis Baudry (1974-75, 1976) and Christian Metz (1977) applied Louis Althusser's theory of ideological state apparatuses to the cinema.

3 Participation is not a coherent theory in film studies or any other discipline yet, but publications such as Theparticpatory cultures handbook (Delwiche & Jacobs Henderson 2013:1-33) have begun to trace the importance of the concept across media studies and other disciplines. The term occurs in discourse on media technologies, such as in Henry Jenkins's book Convergence culture (2009), the Participation in broadband society (Greif et al. 2011) series, and also in relational aesthetics, which is discussed later in this article (Bourriaud 2002). I thus sometimes refer to participation theory as if there is a coherent theory, but I base this on the principles that seem to unite these different instances of the term.

4 The cinema dispositive is discussed in detail in the section dedicated to this, but relates to a mostly critical understanding in film theory, of how the cinema and the film text predicts and shapes the spectator's experience of watching a film.

5 Hereafter referred to as BM. A trailer for the series is available on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2spS4Lc3CM&ab_channel=Channel4. I would encourage the reader to watch this short trailer, as I make visual reference to how spectators are specifically depicted here holding their phones and ambling along.

6 Hereafter referred to as WB.

7 Relational aesthetics is formulated by Nicholas Bourriaud as a mode of art making that subverts the autonomy of the author and the art object by enabling the spectator to participate in the making of the work. It has become very influential in contemporary practice, and has given rise to much renewed awareness of the social implications of art. The theory has also been critiqued in the work of Claire Bishop (2006, 2005) and books such as Interactive contemporary art (Brown 2014).

8 An interesting implication is that Apple seems to realise or suggest that photographs are thus not only taken with the phone, but also viewed there, rather than on one's computer or somewhere else. The phone is thus both a capturing and viewing device.

9 The graphics interchange format was developed for internet use as it allows image files to be compressed in a lossless manner and they can also be animated (GIF [sa]).

10 I use this term loosely to refer to someone operating a camera that can record video footage, as contemporary smart phones can. The term also refers to someone recording digital video, whether for film or television, or indeed another form of video text. The term digital video likewise refers to the medium of recording moving images since the digitalisation of film and television from the late 1980s (Prince 2011:1-10).

11 The BBC news reported on 12 April 2013 that the UK band, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, banned fans from watching the show through their phones or smart devices (Lee 2013). Wales Online reported on 30 June 2016 that Apple has released an infrared blocker to stop fans from recording live concerts (Owen 2016), and The Guardian UK reported on 20 June 2016 that American singer Alicia Keys also banned filming of her concerts on smart phones (Solon 2016). There are countless more references to this in international media such as on Canadian broadcasters's CBC's website (Hopton 2016).

12 Roger Odin (2012:155-169, 2016:45-53) discusses the phone as a 'cinema in [the] pocket', in an article where he relates how people use smart phones to view moving images in a cinematic manner.

13 I refer here to the different critiques of the subject position that Geil (2013) discusses. Among these are arguments that suggest that looking is not in fact Cartesian, and reinforcing of the mind/body split it is associated with. Accordingly, many of the theories that do critique the subject position turn to embodiment in order to discuss the spectator as embodied and not distanced from the body and its sensual presence, such as in phenomenology. Furthermore, the spectator in these formulations is also often mobile and not static as she would be in the cinema (Geil 2013:53-82). While it has been considered across many disciplines that embodiment offers strategies of resistance to the Cartesian notion of subjectivity, I do suggest that this is not guaranteed.

14 The tabloid Daily Mail in the UK featured an article on the staggering amount of road accidents since the launch of the game in the US (Borland 2016). Interestingly, these accidents are not linked only to drivers playing the game, but also pedestrians, who become unaware of their surroundings. The Japan Times featured an article about a driver who ran over a woman while playing the game. (Driver convicted ... 2017). The Wall Street Journal also reported on 15 August 2016 that two women injured by a driver playing the game while driving in Japan (Inada 2016).