Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.32 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2018/n32a13

ARTICLES

Minna Keene: a neglected pioneer

Malcolm Corrigall

Postdoctoral Research Fellow with the DST-NRF South African Chair in South African Art and Visual Culture, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa. malcolm.corrigall@protonmail.com

ABSTRACT

Born in Germany in 1861, Minna Keene lived in Cape Town during a prolific phase of her photographic career. Whilst at the Cape (1903-1913), she achieved international acclaim as a pictorialist photographer. Her photographs of South African subject matter were shown at exhibitions across the world. She was quick to recognise opportunities to translate her photographic success into financial profit and was one of very few women to operate a photographic studio in early-twentieth century South Africa. Keene actively circulated reproductions of her photographs as self-published postcards and in popular publications. Through these interventions, she made a substantial contribution to popular visual culture at the Cape and was celebrated by local and international audiences. Despite her pioneering status, she has been overlooked in the existing literature on South African photography, and, although she has received limited attention in Euro-American histories of photography, much remains unknown about her life and work, especially in relation to her time in Cape Town. Drawing on multi-sited research, I present a biographical account of Keene which analyses the ambivalent gender politics in her photographs as well as her uncritical adoption of colonial categories of race.

Keywords: Photography, South Africa, pictorialism, gender, racism, Cape Town.

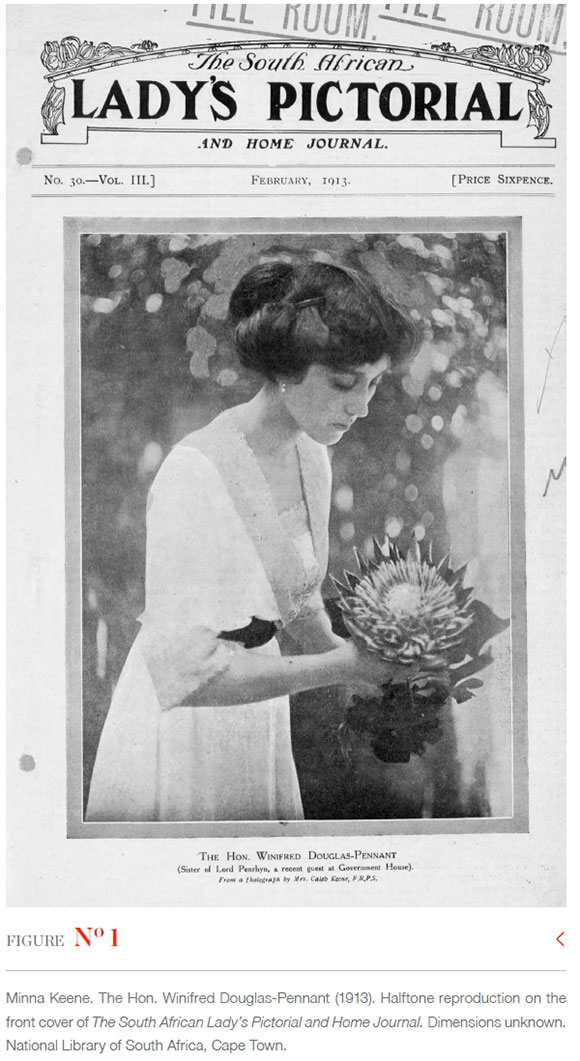

In February 1913, Minna Keene's photograph of Winifred Douglas-Pennant appeared on the front cover of The South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal (est. 1910) (Figure 1). It was one of a number of Keene's portraits of eminent women from colonial society that were reproduced on the magazine's covers between 1911 and 1913. This publication was amongst the first women's magazines in the country and rapidly found a wide readership of white, English-speaking South Africans (Venter 2014). The portrait of Douglas-Pennant, a guest of the Governor General of South Africa, was taken at Keene's 'garden-studio' on the grounds of her family home in the Cape Town suburb of Rondebosch (The South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal 1913:1). An avid gardener as well as a respected botanical photographer, Keene utilised horticultural elements to design her portraits of female clients (Lewis 1913:151). Douglas-Pennant's demure pose and downward gaze, along with the protea flower delicately clasped between her hands, implied qualities of submissiveness, beauty and grace commonly associated with patriarchal notions of femininity. On the wall in the background, the shadow of a tree, mottled with piercing sunlight, provided a glimmering canvas against which the subject was planted. This representation reflected a visual culture in which women were often rooted in the vegetable world, associated with nature as opposed to culture. Tellingly, despite the fact Keene produced portraits of both men and women, the bucolic environs of her 'garden studio' were exclusively reserved for white, female sitters.1

Yet, despite such connotations, the gender politics of The South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal were by no means one-dimensional. The publication carried news of the women's suffrage movement in South Africa as well as profiling trailblazing local women who, despite considerable opposition, were pursuing careers in a range of historically male professions (Miss Madeline Wookey 1912; An Industrial Exhibition 1911). As I demonstrate, Keene was herself a pioneer, being one of the few professional women studio-operators in South Africa at the time, and having achieved a level of international recognition, which was then unprecedented for a photographer based in Cape Town, whether male or female. Her trajectory as a photographer is a testament to her ability to navigate photographic, commercial and social networks that were overwhelmingly male-dominated. Keene's enterprising character is apparent in the various ways she sold and disseminated her photographs. Furthermore, as I reveal in this article, the gender politics reflected in her work were on occasion more ambivalent than her portrait of Douglas-Pennant might suggest. Harder to admire are Keene's portraits of "racial types" in South Africa. Keene uncritically adopted colonial categories of race, which had been used by her artistic predecessors at the Cape, and translated them using visual conventions associated with the pictorialist movement in photography. She recognised a voracious appetite amongst white audiences for such imagery and turned this to her commercial and professional advantage. In particular, Keene enthusiastically participated in a local tradition of orientalism centred on the Muslim population of Cape Town. Through these interventions she helped shape white visual culture at the Cape and, in so doing, achieved a celebrated status amongst local and international audiences.

Considering the esteem in which she was held by her contemporaries, it is curious that Keene has not received more scholarly attention. Indeed, for someone once described as 'one of the greatest women photographers in the world', this neglect is puzzling (Vail 1925).2 She is not mentioned at all in any general or specific work on the history of photography in South Africa. However, owing perhaps to her migratory life, she has received brief mention in European and North American texts (Harker 1979:188; Rosenblum 2000:156; Koltun 1984:46). Short, but valuable, biographical sketches have outlined aspects of Keene's life and career, mainly concentrating on the reception of her work in Britain and the time she spent in Canada (Rodger 1987; Hudson 2014). One of her photographs was recently included in an exhibition examining the interplay between western schools of painting and Euro-American trajectories of photography (Jacobi & Kingsley 2016:126). Despite such insights, much remains unknown. This is particularly true of Keene's long residence in South Africa, which has largely been ignored or treated as entirely incidental to her practice, despite the fact that she produced her most widely circulated photographs there (Rosenblum 2000:156; Jacobi & Kingsley 2016:126). There has also been no consideration of local audiences in South Africa, nor any understanding about how historical contexts and visual discourses particular to the Cape Colony shaped her output.

In order to correct this neglect, I have conducted extensive primary research into Keene's life and career. I have drawn on material in archives and private collections in South Africa and England that have not been considered before, shedding light on previously unknown aspects of Keene's personal and professional trajectory, not only in South Africa, but also in England and North America. Where original photographs have not survived, I have located reproductions within a range of printed publications and ephemera.3 Of course, Keene's archive remains incomplete and is peppered across several continents, a state of affairs complicated by the fact that not all of Keene's photographs would have been reproduced elsewhere or preserved in institutional or personal collections. However, as I demonstrate, such traces - even in their fragmented state - are a testament to the wide-reaching popularity of Keene's work during her lifetime and reflect the diverse historical contexts she was situated within.

Minna Keene was born Minna Bergmann in Arolson, Germany in 1861 (Lewis 1913:151; Rodger 1987:12). Her family were descendants of French Huguenots who fled to Germany during the persecutions of the late seventeenth century (Sun Pictures 1910). She moved to England around the late 1870s or 1880s to work as a governess, probably in the Scarborough area (Rodger 1987:12; Keene & Sturrup 1981). It was there she met Caleb Keene, an artist and decorator, whom she married in 1887 (London Metropolitan Archives P74/TRI; Keene & Stirrup 1981). Caleb was from a Quaker family and studied at the Scarborough Art School in the early 1880s (McAllister-Ross & Butt 2010:5-6). They moved to Bath, then Bristol, where Caleb managed a firm of painters and decorators (Western Cape Archives and Record Service Vol 3/227). They had three children, Louis (b.1888) and Violet (b.1893), as well as Mona (b.1890), who died in infancy (General Register Office; Green 1893:110). Minna embraced the Quaker faith and was a member, along with her family, of the Bristol and Frenchay Monthly Meeting of Friends (University of Cape Town Special Collections BC749).

Minna inherited a camera from Caleb, a once 'ardent photographer' who had gradually lost interest in the medium, and it was not long before her photographic accomplishments surpassed those of her husband (Sun Pictures 1910). She began successfully submitting photographs to magazine competitions and camera club exhibitions from the late 1890s onwards (Hudson 2014). In 1900, she authored an article on flower photography for the journal Photography, a subject that seems to have dominated much of her early output (Keene 1900:334-336). Many female photographers of the period began their careers by specialising in this genre (Hudson 2014). Several of her botanical and natural history studies, which she registered for copyright protection at the Stationer's Office in January 1903, were selected for publication in a series of textbooks used in schools across Britain and its colonies (Hudson 2014; New Apparatus &C. 1905). She displayed further commercial acumen by self-publishing Keene's Nature Studies in the same year, which she appears to have reprinted in 1905 and 1906. This slim volume contained photographic plates depicting 'budding plants, flowers, fruits and seeds in various stages of growth' and 'birds and their nests and other natural history subjects' (New Apparatus &C. 1905).

These photographs were highly praised in the press for their veracity and artistry, as well as their utility as reference works for students and artists (Reviews 1903). Photo Era went further in identifying this branch of photography as especially suited to women, and in so doing reinscibed discourses regarding the "separate spheres" appropriate to men and women:

It is quite obvious... that she performs her task con amore, and the extraordinary success marking her efforts in this important domain of science is proof of our contention that certain phases of photography belong emphatically to woman's sphere (The Work of Mrs. Caleb Keene 1906).

On 17 September 1903, Minna Keene and her children set sail for Cape Town to join Caleb, who had emigrated earlier in the year (National Archives BT27). Caleb arrived in Cape Town without any capital but soon obtained a decorating contract from Lloyds & Co. After completing the contract to the satisfaction of the firm, they loaned him the money needed to start his own painting and decorating business on Long Street (Western Cape Archives and Records Service Vol 3/227). Not long after her arrival, Minna continued to pursue her interest in botanical photography, now focusing on the distinctive flora and fauna of the Cape (A Note Concerning our Illustrations 1907). By this time, the Cape Colony could boast a rich history of botanical imagery dating back to the seventeenth century (Blake 2001:4). Women artists made significant contributions to this genre, and by the early twentieth century, a number of women were, like Keene, producing botanical art on a professional basis (Arnold 1996:71).

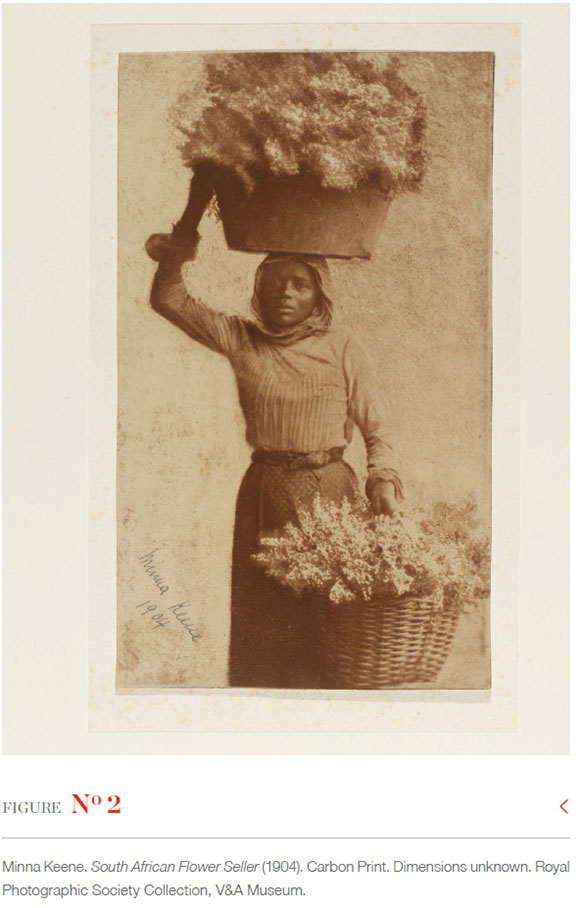

However it was also during this period that Minna Keene broadened her repertoire and began producing portrait studies of so-called "racial types", as well as picturesque landscape photographs taken in and around Cape Town. Her photography of "racial types", produced from 1903 onwards, were especially popular with white audiences in South Africa and Europe who praised both their artistic qualities and their supposed scientific value (Mrs. Caleb Keene's Pictures at the Lyceum Club 1907; Mrs. Caleb Keene's Exhibition 1910). Photographs such as South African Flower Girl (1904) (Figure 2) display a curious mix of conventions derived from the pictorialist movement in photography, which at the time was at the height of its influence, and typological approaches to portraiture then common to much of white South African visual culture.

This portrait belonged to a wider body of photographs that earned Keene fame and recognition within transnational networks of pictorialism. In 1906 Photograms of the Year celebrated Minna Keene as a 'new force' in pictorialism whose 'decidedly increased powers' were evident in her photographs of South African subject matter (The Work of the Year 1906:69). Her photographic prints were widely exhibited at salons across the world, and reproduced as half-tone illustrations in the leading photographic periodicals. Keene was also welcomed into the ranks of leading pictorialist institutions. In 1908, Keene was elected a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society - the first woman from South Africa and one of only five women worldwide to have achieved this distinction (Pictorial Photography 1908). In 1909, her name was put forward for admission to the Linked Ring Brotherhood,4 and by 1911, she had been elected a member of the prestigious London Salon of Photography (The London Salon of Photography's Exhibition 1911).

Pictorialism was a movement that sought to assert photography's status as an art form by foregrounding the skill and creativity involved in hand printing high-quality photographs. It was initially led by groups of European and American photographers who seceded from established photographic clubs and societies in the 1890s and early 1900s in protest at a perceived bias towards scientific and commercial photography. Its rapid dissemination was facilitated by an international network of camera clubs, periodicals and salon exhibitions. Pictorialists drew inspiration and subject categories from recent developments in western painting, drawing, design and etching, as well as a variety of local art-making traditions across the world. Although pictorialism has sometimes been narrowly conflated with the use of diffusion and soft focus, Young (2008:252-253) has argued that the aesthetic practices associated with pictorialism were in fact highly diverse. What united pictorialists was instead their shared emphasis on conveying beauty and sentiment, and, similar to the arts and crafts movement, their veneration of craftsmanship. For the pictorialist, each hand-printed photograph was conceived of as a unique, auratic work of art, capable of communicating subjective experiences of emotion and pulchritude. Photography was seen as a pliable process that relied on the creative labour of the artist-photographer, rather than simply being an automatic product of mechanical processes (Nelson 2017).

Keene's exposure to pictorialism is discernible in the meticulous care with which she hand-printed South African Flower Girl. The photograph demonstrates her mastery of the carbon process, a printing technique popular amongst pictorialists. Carbon prints were composed of a specially treated mixture of gelatine and pigment which hardened when exposed to light. This gelatine mixture, sensitised to light by using potassium dichromate, was applied to the surface of photographic paper. Light was then projected onto this paper under a negative. The areas exposed to less light remained more soluble, and were washed away using hot water, leaving an image made up varying degrees of hardened, coloured gelatine (Bennett 1904). Carbon printing was a highly malleable process that provided scope for artistic intervention. Often described as a control process, it required the pictorial worker to employ great dexterity as they used brushes and other hand-based tools to wash away the soluble gelatine as well as emphasise or alter aspects of the image surface during different stages of development (Peterson 1989:239). By opting for this technique, Keene was able to perform her technical mastery of the carbon process, and create a material object that demonstrated, in its uniqueness, her creative labour and the singularity of her artistic vision. In other words, this was clearly an image that had been worked on by hand with thought and care. The plush texture of the carbon print envelops the subject within a dreamlike atmosphere, evoking the interiority and emotional life of an individual. The delicate rendering of subtle distinctions in tone, the washed out background and the softly focussed sentimentality of the floral baskets all function to imbue the subject with a romantic glow. The thoughtful, assessing gaze of the subject forces the viewer to register her as an autonomous psychic presence. As with many pictorial photographs, the portrait reveals Keene's desire to capture the inner life of the subject as well as communicating sentiment and beauty.

This intimate effect is at odds with the impersonal nature of typological portraiture, in which the individual identity of the subject was commonly supressed. The "type" photograph was first developed in the 1860s and early 1870s by anthropologists who sought to use the emergent technology of photography as a systematic means of collecting data. This was not a uniform endeavour and different methods of using the camera to record information were attempted. Such "types" were taken as representative of the general physical and cultural characteristics of a designated group. However, "type" photography was also practiced in a much looser form by commercial photographers in the nineteenth century (Edwards 1990). Studio photographers in South African towns and cities, for instance, commonly produced carte de visite and cabinet cards of "racial types" (alternatively referred to as "native types") in their studios, utilising stereotypical props, costumes and painted backgrounds. There was a widespread market for such images amongst white publics (Garb 2013:56-58). Alongside the photograph's pictorialist conventions, the subject of South African Flower Seller thus also belonged to a popular trajectory of "type" photography in South Africa.

The anonymous "type" in Keene's Cape Flower Girl would have been widely identified by contemporaneous white audiences as the racialised figure of the "Malay" flower seller. Flower sellers had been trading in central locations in Cape Town since the mid-1880s, comprising a diverse range of black business people that would have been described or classified as either "Coloured" or "Malay" by white observers and government officials (Boehi 2013). They commonly featured in popular visual representations of Cape Town and formed part of a stereotypical visual lexicon that came to be associated with the city (Bickford-Smith 2012:141-142; Boehi 2016). The foregrounding of distinctive aspects of occupation and religious dress (such as the Islamic headscarf), as well as the presentation of the subject against a plain background, reveal anthropological attempts to highlight the distinctive racial, sartorial, cultural and occupational features of a supposedly discrete "type". Despite essentially being a sojourner at the Cape, Keene displayed a startling degree of entitlement in claiming knowledge of so-called "types" in the region (see Keene 1909). This is reflective of a widespread trend during the first decade of the twentieth century whereby self-styled "experts" played a crucial role in popularising notions of racial difference amongst white publics (Dubow 1995:92). The purportedly objective viewpoint of her typological portraits existed alongside - but also in tension with - pictorialist ideas and practices that emphasised the subjectivity of artistic perception.

The photograph inadvertently records some of the contradictions of the "type" photograph in colonial visual culture. The flower seller is wearing a dress made from blueprint fabric, which is typically distinguished by white motifs on a cotton fabric dyed with indigo (Leeb-du Toit 2017:5-6). The majority of blueprint sold in South Africa around the turn of the century was manufactured in either Germany, Holland or Belgium - blaudruck or blauwdruck in German and Dutch, respectively - as these textiles were of a much higher quality than blueprint produced in Britain (Leeb-du Toit 2017:62-64). Although one of the likely intentions of the photograph was to highlight the distinctive sartorial choices of "Malay" flower sellers, and by doing so amplify the exoticism of the subject, the photograph inadvertently attests to a longstanding trajectory of intercultural borrowing and adaptation. It also reflects a local preference for blueprint that had been common to working class women across racial divides since the seventeenth century, thereby exposing the artificial nature of a visual culture which assumed social groups were culturally hermetic and wholly defined by racial difference (Leeb-du Toit 2017:32-65).

The titles of Keene's wider corpus of South African "types" are replete with racial epithets. Examples include Basuto Girl (1907), Indian Fruit and Vegetable Seller (c.1906), Zulu Mother (c.1906) and Coloured Children (c.1906). She also photographed 'Boers' and 'Huguenots' as a discrete "type" (Sun Pictures 1910). Of course, Keene did not invent these visual categories, but rather uncritically adopted racialised portraiture conventions which already had a long trajectory in the Cape Colony. Despite operating within this longstanding tradition, her photographs were also taken and circulated during a specific historical moment in which contemporary scientific discourses of race were articulated across imperial intellectual networks with increasing frequency. The growing influence of scientific racism across the British empire coincided with political imperatives at the Cape to further codify and institutionalise racial segregation in the build up to the political union of South Africa in 1910 (Dubow 1995:120-165). A narrated lantern slide show Keene presented to the Royal Photographic Society in London in 1909, entitled 'Racial Types in South Africa, and the 'Flora of the Country', shows how much of the popular discourses of race she had absorbed by this point. In a wide-ranging talk she referenced colonial categories of race, displayed a preoccupation with the supposed physical and cultural differences of her portrait subjects, regurgitated widespread myths that Great Zimbabwe was built under the direction of architects from Sheba, and described the language of 'Bushmen' as having 'a wonderful resemblance to the different cries of the baboon' (Keene 1909). Many of these convictions mirrored popular discourses of race and civilisation which were frequently repeated at the time. For example, the quest to attribute the ruins of Great Zimbabwe to a Middle Eastern civilisation became somewhat of an obsession amongst public intellectuals at the time, whose ingrained belief in the inferiority of sub-Saharan Africans could not accommodate the idea of an African civilisation (Dubow 1995:68-69).

By far the most numerous and popular of all Keene's "types", however, were her studies of so-called "Malays". From around the 1850s onwards, the term "Malay" was used by white observers to describe the Muslim population of the Cape Colony, and from the 1870s onwards there is evidence that Muslims began to refer to themselves as Malays, at least in their dealings with whites (Bickford-Smith 1994:298). Islam was adopted by a heterogeneous slave population that had been brought to the Cape by the Dutch East India Company from 1658 onwards. Islamic practice provided this diverse group with a source of psychological pride and religious autonomy. Following the emancipation of slaves in 1834, the heterogeneity of the Muslim population was gradually overwritten by colonial discourses of race. "Malay" came to no longer connote a pan-racial faith identity but an illusory category of racial fixity, purity and distinctiveness (Baderoon 2014:9-15). Titles of Keene's photographs include Malay, Malay Woman, Old Malay, and Malay Laundry. These studies found favour with both local and international audiences, becoming somewhat of a signature for Keene. The African World Annual's appraisal of Keene's photographs reflect the prominence given to Keene's "Malay" portraits within her wider range of typological studies: 'Mrs. Keene's [...] wonderful figure studies of picturesque Malays will make an especial appeal' (Pictorial Photography 1908).

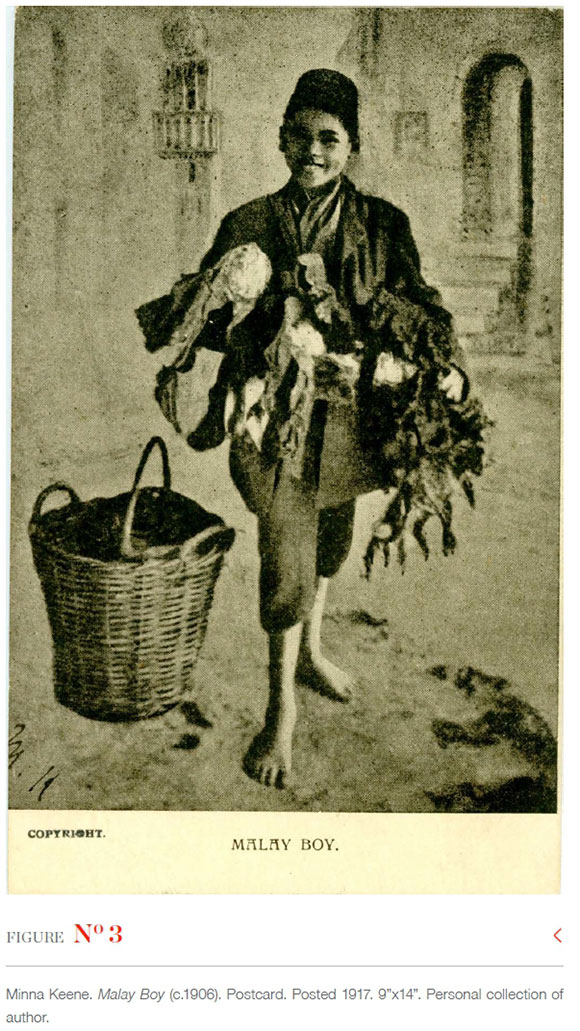

Keene's heavily-retouched photograph, Malay Boy, reflects the saccharine sentimentality of her wider corpus of Malay portraits (Figure 3). It circulated widely, having been published by Keene as a postcard in 1906 and reproduced in the Cape Times' Christmas Number of the same year. It depicts a "Malay" boy, identifiable by his characteristic Fez, selling vegetables - an occupation strongly associated with the so-called "Malay" community. The child's broad smile and demeanour reinforced stereotypical notions of the cheerful and servile nature of "Malays", tropes which abounded in colonial visual culture. Baderoon (2014:26-27) argues that picturesque images of pliant "Malays", happily at work, were popular precisely because they alleviated white guilt regarding the historical and ongoing exploitation of the Muslim population. Keene also seems to have intentionally drawn out particular details of the architecture which stand in relief against an otherwise blurred background, enveloping the surroundings in a nostalgic haze. The lines and edges of these buildings may have been emphasised by applying hand tools to the print surface during development. This was probably done to locate the photograph in the so-called "Malay Quarter" of Cape Town, also referred to as Bo Kaap, and to appeal to the civic pride of her local audience. Keene took a number of her portraits in this neighbourhood, where the vernacular architecture of its homes and mosques attracted many white artists and photographers during the 1900s. Such picturesque images of the "Malay Quarter" and its inhabitants were frequently used in Capetonian visual culture as a shorthand for the cultural distinctiveness of the city (Bickford-Smith 2012).

Minna Keene was widely regarded in metropolitan centres of artistic photography as the leading light of South African pictorialism. The Amateur Photographer saw Keene 'as representing the best in pictorial photography in South Africa' (Exhibition of Pictorial Photographs by Colonial Workers 1909). However, Keene remained largely aloof from local networks of pictorialist photographers that had emerged in Cape Town during the 1900s. By the mid-1900s, pictorialism was a core feature of photographic discussion and production amongst members of the Cape Town Photographic Society. However, detailed minutes taken at the society's meetings and news clippings related to the development of the society show no record of Keene having been a member, nor of her attending any of their events. It could be assumed that membership was restricted to men, but the Society's minutes show that there were women members during this period (National Library of South Africa MSB124). Furthermore, Keene did not participate in the Society's International Photographic Exhibition of 1906, a pictorialist exhibition so large and costly to organise that it burdened the Society with debts for years to come (Vertue 1960:363). Another landmark event in early South African pictorialism was the publication of The South African Photographic Annual in 1909. Here, again, Keene is strangely absent. Reviewing the publication, the British Photographic Journal was also surprised by this omission: 'curiously enough, we can find no representation of the only South African photographer whose work is at all known here - Mrs. Caleb Keene' (New Books 1909). It is difficult to say for certain why Keene chose to keep her distance from local pictorialists, but judging by the publication and exhibition practices outlined below, she focused on reaching popular audiences in Cape Town, and on achieving international recognition. This is not to say that local pictorialists were unaware of her. On the contrary, an annual summary of pictorialism in South Africa, written by one of its leading figures, highlighted a solo exhibition of Keene's work in Cape Town as a major event which provided 'examples and encouragement' to local pictorial photographers (Thompson 1908:89).

Keene's growing popularity from the mid-1900s onwards coincided with the increased prominence of women in transnational networks of pictorial photography (Ward 1906; Hines, Jr. 1906). Along with figures such as Adelaide Hanscom, Zaida Ben Yusuf and Emma Barton (to whom her work was often compared), Keene was part of a group of women who achieved international success as pictorialist and professional photographers during the 1890s and 1900s. In order to accommodate this influx of women into the photographic field, and to alleviate any anxieties such competition might have introduced, male commentators sought to recast photography as a vocation as well suited to women as it was to men, albeit for fundamentally different reasons. In so doing, they were able to celebrate their female contemporaries without discarding patriarchal notions of femininity or hierarchical conceptions of sexual difference. Writing in Photo Era, Richard Hines, Jr. (1906:143-144) observed that:

There is no more suitable work for women than photography, whether she takes it up as with a view of making it a profession or simply as a delightful pastime to give pleasure to herself and others. She is by nature peculiarly fitted to the work, and photography is becoming more and more recognised as a field of endeavour particularly suited to her. There is scarcely a woman who has not some inborn artistic feeling, latent though it may be before brought out by study and training. Nevertheless, it is there, and its presence, in greater or less degree, is promise of success in photography. Cleanliness and patience are two of the cardinal virtues necessary to the successful pursuit of photography. The first seems to be a God-given attribute to most women; while if they have not the latter in sufficient amount, it is a virtue that can be cultivated. The light, delicate touch of women, the eye for light and shade, and their artistic perception, render them admirably fitted to succeed in this work.

Keene often reproduced her salon prints in a variety of different material forms. Such webs of intertextuality activated a range of meanings for diverse audiences in disparate contexts of publication. They also show that Keene not only circulated her work in rarefied pictorialist networks, but also directly addressed local South African audiences, thereby contributing to popular visual culture at the Cape. In 1906, Keene registered a company in order to publish her photographs as postcards, and in November that year took out advertisements in the Cape Times announcing the availability of 24 picture postcards for sale. These 'wonderful reproductions of Mrs. Keene's best work', which illustrated 'Cape Folk and Scenery', were printed in England and sold to local consumers in Cape Town, who either collected them or posted them to friends and family within Southern Africa or across the world (Picture Postcards by Mrs. Caleb Keene 1906). Their publication coincided with a worldwide boom in the production and dissemination of the picture postcard. A quick and affordable means of communicating with people across the world, picture postcards were also material objects with visual appeal, and were widely collected by consumers for their aesthetic qualities (Geary 2013:71-72).

Keene also frequently contributed to the annuals and "Christmas Numbers" of local newspapers and magazines. Early annuals such as the Cape Times Christmas Number, published under various names between 1891 and 1941, were light and accessible in tone and presented their white, English-speaking readers with content that celebrated the diversity and distinctiveness of Southern Africa and cultivated a shared white national identity. As well as publishing work by local authors, poets, artists and historians, such annuals were lavishly illustrated with half-tone reproductions of work by Capetonian photographers (Bradlow 1976). The photographs chosen for inclusion were often studies of "types" in Cape Town. For example, a montage of Keene's "Native Types" appeared in the African World Annual 1908/09 (Figure 4). The framing of the half-tone reproductions with art nouveau stylings reflect the decorative role that photographs of "native types" often played in colonial visual culture. The portrait subjects remain nameless, and no context is provided in the accompanying article, which reports solely on Keene's photographic credentials. In this page layout, and throughout the publication, the black population of Cape Town are included as an aesthetic spectacle and to provide a sense of place, while remaining essentially voiceless. A selection of Keene's South African photographs, which had previously appeared as salon prints and postcards, were also published in the Cape Times Christmas Number of 1906 and the Cape Argus Christmas Number of 1911 (Keene 1906; Keene 1908; Keene 1911).

In many of her photographs, Keene displayed a fascination with the social institution of motherhood. Such photographs constituted a study of maternal practices across different cultural groups. This body of work was presented in ways which highlighted cultural difference, but ultimately stressed the supposed universality of women's maternal instincts. They are thus part of a long trajectory of artistic practice that presents childcare as the "natural" province of women (Nochlin 1991:19). Keene's postcard Zulu Woman and Her Baby (Figure 5) depicts a woman standing in profile carrying a baby on her back, highlighting to European audiences the unfamiliar way in which some African women transported their children using a sling. Like similar postcard images of isiZulu-speaking mothers, Zulu Woman and Her Baby would have appealed to European audiences in that it contained a mixture of familiar and exotic elements; familiar in terms of a recognisable concept of motherhood, but peculiar and curious in the method of carrying children (Geary 2013:70-71).

On 26 January 1907, Minna Keene arrived in London from Cape Town for an extended stay in Europe (National Archives BT26). Keene's movements during this period reflect her participation in transnational networks of photography and religion. In April 1907, she held an exhibition in London at the Piccadilly branch of the Lyceum Club, a show which later travelled to Copenhagen and elsewhere on the Continent (Photographs by Mrs. Caleb Keene 1907; What Friends are Doing 1908:10). In England, Keene also enrolled her daughter Violet at Sidcot School, a Quaker institution, and in May 1907 represented Cape Town's Quaker community at the Yearly Meeting of Friends in London (What Friends are Doing 1907:9).

On 21 October, 1909 Keene set sail from Liverpool to Cape Town with her daughter and arrived back in Cape Town to find her husband's finances in dire straits (National Archives BT27). Since opening shop in 1903, Caleb's business did not seem to have generated a profit and he relied heavily on creditors for finance. By 1906, he had accrued a significant amount of debt (£3,500) and in November 1908, he voluntarily surrendered the firm for liquidation, having all but abandoned the business in September of that year (Western Cape Archives and Record Service Vol 3/227). Undoubtedly, the severe depression which afflicted Cape Town's economy in the mid-1900s would have contributed to his financial woes. In 1911, he used his son's name to obtain the necessary credit to open another decorating showroom and antique furniture dealership on Parliament Street, at which he assumed the position of manager (Juta's 1911 [sa]:253; Keene's 1911). It appears unlikely that this venture was a runaway success as on 2 October, 1912 Caleb set sail for England to 'spend a short holiday and take a much needed rest', after which he permanently emigrated to Montreal, Canada a few months later (News of the Day 1912; Library and Archives Canada). Evidently, Caleb's insolvency prevented him practicing business under his own name in South Africa and compelled him to emigrate once again.

Her husband's changeable financial circumstances may have influenced Minna Keene's decision to go into business as a professional studio photographer, a vocation which, according to Photograms of the Year, she took to with 'conspicuous success' (Mortimer 1912:7). By 1912, Keene was already operating two studios in Cape Town, one, the aforementioned garden studio at her family home in Rondebosch and the other located within the same premises as her husband's resurrected showroom on Parliament Street (Juta's 1913 [sa]:248). Keene's international reputation, and the favourable coverage of her exhibitions in the Cape press, would have immediately bestowed a certain prestige on this new enterprise. Keene evidently had a knack for ingratiating herself with powerful and high-profile individuals in colonial society. Such connections served her well as a studio photographer and many well-known individuals from local and visiting colonial elites patronised her studios.5 Keene's studio also specialised in child portraiture, a genre often associated with the handful of women studio photographers practising in South Africa at the time (Children of the Cape Province from Photographs by Mrs. Caleb Keene FRPS 1913).6 Keene closed her thriving studios when she left South Africa in May 1913 in order to join her husband in Canada.

These photographic practices also give a sense of the extensive social networks Keene had cultivated in Cape Town by the time she opened her studios. It is clear that she was part of artistic circles. She exhibited alongside Nita Spilhaus, Constance Penstone and Allerley Glossop in the art section at the S.A. Women's Industrial Union Exhibition in 1912, as well as photographing artists such as Churchill Mace (S.A. Women's Industrial Exhibition 1912; Portraits at Perry's 1913). Local artists Ruth Prowse, Beatrice Hazell and Edward Roworth attended her exhibitions, as well as prominent patrons and collectors of Cape art, such as Dr. James Luckhoff (Mrs. Caleb Keene's Exhibition 1910; Mrs. Keene's Pictures 1912).7 In addition, she enjoyed the support and friendship of a number of political and diplomatic figures. For example, she befriended Annie Botha, wife of Prime Minister Louis Botha. The Keene family would often visit Groote Schuur, the official Cape residence of the South African Prime Minister, for coffee with the Botha family, nearly all of whom she photographed (Keene & Sturrup 1981). A Cape Argus profile stated that the former Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, John X Merriman, and the prominent politician, Dr JH Meiring Beck, showed 'the greatest interest in her work' (Sun Pictures 1910). She was sufficiently well connected within the local elite to escort visiting British aristocrats, the Earl and Countess of Meath, around the city, having met them on their arrival at Cape Town Harbour in February 1911. On their first few days in Cape Town, Keene introduced the visiting dignitaries to the editorial staff of the Cape Argus, as well as Agnes Merriman, a philanthropist and wife of John X Merriman (Reginald 1924:183-184). As this suggests, she was also well connected with local journalists, and counted Edith Woods, a fulltime reporter for the Cape Argus and a campaigner for women's suffrage, amongst her close friends. Keene was an avid letter-writer and managed to maintain such friendships long after she emigrated to Canada in 1913.8

Whilst running her studios, Keene continued to stage frequent exhibitions of her work in Cape Town. These exhibitions provided another means of generating income through selling prints and advertising her services as a professional portraitist. On 19 August 1910, over a hundred guests attended a private view at her Rondebosch home, where they could also buy the work on display (Sun Pictures 1910; What Friends are Doing 1910). This was followed shortly after by another exhibition of her photographs at Darter's Gallery on 29 August 1910, which included a number of portraits of eminent figures, such as Captain Scott of the Antarctic, who also opened the exhibition in person (Art in Photography 1910). In January 1912, she held an exhibition at her home where she sold works and took a 'large number' of commissions from the assembled guests (Mrs. Keene's Pictures 1912). Later in the year, she held an exhibition at her Parliament Street studio, mainly comprising studio portraits of women and children (Camera Portraits 1912). Her final Cape Town exhibition, 'Men of Cape Town', opened at Perry's Gallery in March 1913, and included portraits of politicians such as Abdullah Abdurahman, leader of the African Political Organization, and the former prime minister of the Cape Colony, Leander Starr Jameson (An Exhibition of Camera Portraits 1913; Portraits at Perry's 1913). Keene also displayed and sold her photographs at the depot of the South African Women's Industrial Union in Cape Town, as indeed did fellow artist Constance Penstone (Reginald 1924: 183-4; Women's Interests 1910).9

In the press coverage of these exhibitions, there are hints that some of Keene's photographs expressed a radicalism at odds with the conservative gender politics discernible elsewhere in her work. The Cape Times' review of Keene's 1910 exhibition at Darter's Gallery referred to two photographs on display that were 'essentially interesting to suffragettes' (Mrs. C. Keene's Art Exhibition at Darters 1910).10 The article's short description makes clear that these were photographs of political protests staged by women's suffrage activists in London. According to the article, one photograph depicted a group of women waiting to confront British Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, outside parliament, whilst the other was a portrait of a woman with 'a petition under her arm busy knitting away the time' until Asquith arrived (Mrs. C. Keene's Art Exhibition at Darters 1910). These photographs would have been taken at some point between 1908 and 1909, coinciding with Keene's time in London and Asquith's tenure as British Prime Minister (1908-1916). I have been unable to locate extant copies of these photographs. The Cape press reported on these two prints with interest,11 albeit in a somewhat dismissive tone that skirted around the possible political connotations of the images by focusing on the seeming contrast between political activism and normative conceptions of gender:

Mrs. Keene finds artistic material in the "Suffragette" on guard at the House of Commons, waiting for the unwary minister, the inevitable petition tucked into her shoulder strap. A stalwart college-bred woman, is this, and miracle of miracles, she is knitting in a sweetly feminine way the while she waits. An artless shadow of a coming man has been cast across the picture. Another militant group includes ladies of title, smiling but vigilant (Sun Pictures 1910).

One could instead interpret this juxtaposition as a visual strategy whereby Keene appropriated patriarchal notions of women's patient, respectable natures and deployed them ironically as evidence of their eligibility for the franchise.

These photographs suggest that Keene may have been involved in the women's suffrage movement; a movement that was very much international in character. Women's suffrage campaigns in South Africa first emerged within the temperance movement in Cape Town, which established a suffrage branch in 1895. From 1902 onwards, a dedicated suffrage organisation, the Women's Enfranchisement League (WEL), established branches in cities nationwide. There was cooperation and tension between women's suffrage activists in the Cape Colony and the imperial metropole, as well as with women's suffrage movements elsewhere in the world (Dampier 2016). The suffrage movement in South Africa was dominated by white English-speaking women who were resolutely pro-imperial in outlook, and whose progressivism in matters of gender did not translate into non-racialism. In 1911, following the Union of South Africa in 1910, the WEL came under the auspices of a newly formed organisation, the Women's Enfranchisement Association of the Union (WEAU), who made it clear that they would be campaigning for voting rights to be extended to white women only (Dampier 2016).

In May 1912, Minna and Violet Keene are recorded as having attended a meeting of the WEL in Cape Town (Women's Enfranchisement League 1912). Beyond this, I have been unable to find further evidence of Keene's participation in suffrage organisations at the Cape. However, Keene's attendance at this particular meeting suggests she was at the very least a sympathetic follower of the movement, if not an active member. Furthermore, there is evidence that her time in London was a period of political awakening. Whilst in London she staged an exhibition at the Lyceum Club in April 1907, of which she was a member (Photographs by Mrs. Caleb Keene 1907). The Lyceum Club was a women's social club that attracted an artistic and intellectual membership and had branches across the world. It was also a feminist organisation whose leadership included prominent suffragettes, such as Jane Maria Strachey, and which hosted regular meetings and lectures on suffrage topics and campaigns (Women's Library Archives GB 106 7JMS). It is likely here that Keene was politicised, met fellow suffragettes and attended demonstrations at which the aforementioned photographs were taken.

On May 16 1913, friends and admirers gathered at Cape Town Docks to bid a last farewell to Minna and Violet Keene, as they set sail aboard the Persic. They made a brief stay in England and Germany before joining Caleb and Louis, who were by then settled in Montreal (Social Notes 1913:5; News of the Day 1913). Personal Letters sent by Minna to Edith Dawson, an artist and old friend from England, are a useful source of information about Keene's life in North America between 1914 and 1918. Soon after her arrival, Minna set up a studio in Montreal which she operated with the assistance of Violet. In the summer of 1914, the Canadian Pacific Railway commissioned Minna to produce publicity photographs of the Rockies. Minna and Violet spent almost four months in the Rockies taking photographs 'amongst the wildest & most beautiful scenery in the world' (University of Leeds Special Collections LIDDLE/WW1/DF/009).

During her stay in the Rockies, Keene met the multi-millionaire newspaper tycoon, William Randolph Hearst, a man regarded as the inspiration behind Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941). Evidently impressed by Keene, Hearst paid for her to visit New York in 1914 and offered her a role at a photographic studio he owned on 6th Avenue. She was briefly employed to create an 'artistic atmosphere' for the studio and to produce portraits of society women and children in her own inimitable style (University of Leeds Special Collections LIDDLE/WW1/DF/009). However, Keene's letters reveal that the First World War (1914-1918) was a period of great personal distress. Not only was her son Louis serving in the Canadian forces, but two of her brothers were German soldiers fighting on the opposing front. Her anxiety about the war, coupled with disillusionment over Hearst's prevaricating support for the Allies (she wrote of Hearst that 'he really is no friend of England but goes just as the wind blows & is considered the most unscrupulous man in America.'), led her to desert her position, leave New York and resume her studio practice in Montreal, despite Hearst sending a representative to Canada to implore her to return (University of Leeds Special Collections LIDDLE/WW1/DF/009).

By 1918, Keene was running two studios in Montreal and Toronto and seems to have permanently relocated to Toronto by December of that year, leaving Violet in charge of the Montreal operation (University of Leeds Special Collections LIDDLE/WW1/ DF/009). By 1921, she and her family had relocated to Oakville, Ontario, where she again opened a studio (Social Events 1921; Irwin 1926). Keene continued to print and exhibit her photographs of South African subject matter in international salons well into the 1920s (Tilney 1924:549; Twenty Five Nations send Photos to Fair 1926). Furthermore, the circulation and reproduction of some of her studio portraits within Cape society continued long after her departure for Canada. For example, in 1925, people were still asking Edith Woods for a copy of a photograph produced by Keene in 1913. Woods wrote to Minna that: 'My dearest friends [...] are still begging me for copies for that fancy picture you took me in ringlets all heaven knows how many years ago now [sic]' (Woods 1925).

Archival traces relating to Keene's life and career remain scattered and incomplete. However, taken together, and when considered within the various localised historical contexts in which she operated, an image of Keene as a tenacious historical actor emerges. She displayed an aptitude for mastering a range of genres and, from an early stage, was quick to recognise opportunities to translate her interest in photography into financial profit. She first gained a foothold by gaining proficiency in spheres of photography that were then deemed appropriate for women. In Cape Town, however, she perceived an insatiable appetite amongst local and international white audiences for portraits of "racial types", and broadened her repertoire accordingly. Although deeply problematic, and indicative of the ways in which Keene benefited from and reproduced colonial racial hierarchies, these portraits nevertheless indicated her ability to both gauge and shape popular visual culture. She also used her status within the pictorialist movement as artistic currency when advertising her services as a postcard publisher and, later, as a professional portraitist and, in all likelihood, the breadwinner in her household. Although at times the content of her work reinforced patriarchal notions of femininity, there were, as I have argued, hints of a more progressive zeal in some of her images.

Keene's life and career therefore reveal some of the challenges and opportunities faced by white female photographers in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, as well as their complicity in the colonial project. The patriarchal gender relations in Britain and the Cape mitigated against the success of many aspiring women photographers, and as such, Keene's accomplishments were a testament to her agency and creativity. She is also a remarkable figure in part because there were so few other women practising with a comparable degree of success in South Africa at the time; something which, in itself, is a sobering reminder of the institutional and discursive constraints that prevented many women from pursuing their artistic and commercial ambitions (Arnold 1996:13-14).

REFERENCES

A Note Concerning our Illustrations. 1907. Photography 23(963), 23 April:339. [ Links ]

An Exhibition of Camera Portraits. 1913. Cape Times, 24 March:7. [ Links ]

An Industrial Exhibition. 1911. South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal 2(16), December:18. [ Links ]

Arnold, M. 1996. Women and art in South Africa. Cape Town & Johannesburg: David Phillip. [ Links ]

Art in Photography. 1910. South African News, 30 August:5. [ Links ]

Baderoon, G. 2014. Regarding Muslims: from slavery to Post-Apartheid. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Bennett, HW. 1904. Practical introduction to carbon printing. The Practical Photographer (13):6-29. [ Links ]

Bickford-Smith, V. 1994. Meanings of freedom: Social position and identity amongst ex-slaves and their descendants in Cape Town, 1875-1910, in Breaking the chains: slavery and its legacy in the nineteenth-century Cape Colony, edited by N Worden & C Crais. Johannesburg: Wits University Press:288-312. [ Links ]

Bickford-Smith, V. 2012. Providing Local Colour? "Cape Coloureds", "Cockneys", and Cape Town's identity from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s. Journal of Urban History 38(1):141-142. [ Links ]

Blake, T. 2001. South African botanical art: a study of nineteenth- and twentieth-century imagery. MA dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Bradlow, FR. 1976. The Cape Times Annual: A Survey. Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Library 31(2), December: 20-31. [ Links ]

Boehi, M. 2013. The flower sellers of Cape Town: a history. Veld & Flora 99(3):132-136. [ Links ]

Boehi, M. 2016. Being/Becoming the Cape Town Flower Seller: The Botanical Complex, Flower Selling and Floricultures in Cape Town, MA Dissertation, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Camera Portraits. 1912. Cape Times, 18 December:10. [ Links ]

Children of the Cape Province from Photographs by Mrs. Caleb Keene FRPS. 1913. South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal 3(31), March:13. [ Links ]

Dampier, H. 2016. Going on with our Little Movement in the Hum-drum Way Which Alone is Possible in a Land Like This: Olive Schreiner and Suffrage Networks in Britain and South Africa, 1905-1913. Women's History Review 25(4):536-550. [ Links ]

Dubow, S. 1995. Scientific racism in modern South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [ Links ]

Edwards, E. 1990. Photographic "Types": the pursuit of method. Visual Anthropology 3(2-3): 235-258. [ Links ]

Elliott, P. 2015. Nita Spilhaus (1878-1967) and her artist friends in the Cape during the early twentieth century. Cape Town: Peter Elliott. [ Links ]

Elliott, P & Delbridge, C. 2018/08/26. Emails to author. Accessed 2018/08/26. [ Links ]

Exhibition of Pictorial Photographs by Colonial Workers. 1909. Amateur Photographer 50(1293), 13 July:36. [ Links ]

Garb, T. 2013. Colonialism's Corpus: Kimberley and the Case of the Carte de Visite, in African Photography from the Walther Collection: Distance and Desire. Encounters with the African Archive, edited by T Garb. Göttingen: Steidl:55-69. [ Links ]

Geary, CM. 2013. "Zulu Mothers" and their children travelling around the world: from photograph to picture postcard, in African Photography from the Walther Collection: Distance and Desire. Encounters with the African Archive, edited by T Garb. Göttingen: Steidl:70-80. [ Links ]

General Register Office, London. England & Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index, 18371915 [O]. Available: http://www.ancestry.com Accessed 21 May 2017. [ Links ]

Green, JJ (ed). 1893. The annual monitor for 1894: or, obituary of the members of the Society of Friends in Great Britain and Ireland. London: W. Alexander. [ Links ]

Harker, M. 1979. The linked ring: the secession movement in photography in Britain, 1892-1910. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Hines, Jr., R. 1906. Women in Photography. Photo Era: The American Journal of Photography 17(3), September:141-9. [ Links ]

Hudson, G. 2014. Minna Keene (1861-1943): Pictorial Portraitist. [O]. Available: https://mattersphotographical.wordpress.com Accessed 25 April 2015. [ Links ]

Irwin, AM. 1926. How a woman found fame with a camera. MacLean's Magazine 39(7), April:72-74. [ Links ]

Jacobi, C & Kingsley, H (eds). 2016. Painting with light: art and photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Modern Age. London: Tate Publishing. [ Links ]

Juta's Directory of Cape Town, Suburbs and Simon's Town 1911. [Sa]. London: J. C. Juta. [ Links ]

Juta's Directory of Cape Town, Suburbs and Simon's Town 1913. [Sa]. London: J. C. Juta. [ Links ]

Keene, M. 1909. Racial Types in South Africa, and the Flora of the Country. Photographic Journal 49(5):249-52. [ Links ]

Keene, Mrs C. 1900. On flower photography. Photography 12(601), 17 May: 334-6 [ Links ]

Keene, Mrs C. 1906. The Cape: indoors and outdoors (Photographic Studies by Mrs. Caleb Keene), in Cape Times Christmas Number 1906. Cape Town: Cape Times:9, 12, 20. [ Links ]

Keene, Mrs C. 1908. Clever Photographic Studies of Cape Town Native Types. African World Annual 1908/09 (6), 12 December:272. [ Links ]

Keene, Mrs C. 1911. Cheerful character studies from life, in Cape Argus Christmas Number 1911. Cape Town: Argus:2-3. [ Links ]

Keene's. 1911. Cape Times, 2 September:4. [ Links ]

Keene, V & Sturrup, M. 1981. Interview by Andrew Rodger. [Transcript]. 5 January, Oakville, Canada. [ Links ]

Koltun, L. 1984. Art Ascendant: 1900 - 1914, in Private Realms of Light: Amateur Photography in Canada, 1839 - 1940, edited by L Koltun. Markham: Fitzhenry & Whiteside:32-64. [ Links ]

Leeb-du Toit, J. 2017. isiShweshwe: a history of the indigenisation of blueprint in Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press. [ Links ]

Lewis, TH (ed). 1913. Women of South Africa. Cape Town: Le Quesue & Hooton-Smith. [ Links ]

Library and Archives Canada. Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935 [O]. Available: http://www.ancestry.com. Accessed 21 May 2017. [ Links ]

London Metropolitan Archives, England. P74/TRI, Item 018. Register of Marriages, Holy Trinity, Chelsea. [ Links ]

McAllister-Ross, H & Butt, S. 2010. Elmer Ezra Keene. Newsletter: The Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society (81), Spring:5-6. [ Links ]

Miss Madeline Wookey. South Africa's First Lady Lawyer. 1912. South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal 2(24), August:3. [ Links ]

Miss Marian Maxwell. 1912. Rand Daily Mail, 5 December:6. [ Links ]

Miss Marion Barnard: Photographic Artist. 1906. Cape Times, 13 March:4. [ Links ]

Mortimer, FJ. 1912. This Year's Work: A Retrospect and Some Comments, in Photograms of the year 1912, edited by FJ Mortimer. London: Hazell, Watson & Viney:3-10. [ Links ]

Mrs. C. Keene's Art Exhibition at Darters 1910. Cape Times, 30 August:8. [ Links ]

Mrs. Caleb Keene's Exhibition. 1910. Cape Argus 30 August:2. [ Links ]

Mrs. Caleb Keene's Pictures at the Lyceum Club. 1907. Photographic News 51(593), 10 May:381. [ Links ]

Mrs. Keene's Pictures. 1912. Cape Argus, 20 January:13. [ Links ]

Murphy, M, private collector. 2017. Interview by author. [Transcript]. 30 March, Cape Town. [ Links ]

National Archives, England. BT27. UK Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960. [ Links ]

National Archives, England. BT26. UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960. [ Links ]

National Library of South Africa, Cape Town. MSB124. Cape Town Photographic Society Collection. [ Links ]

Nelson, A. 2017. The subtle beauty of platinum and palladium prints, in Platinum and alladium photographs" technical history, connoisseurship and preservation, edited by C McCabe. Washington: American Institutte for Conservation:15-27. [ Links ]

New Apparatus, &C. 1905. British Journal of Photography 52(2365), 1 September:695. [ Links ]

New Books. 1909. British Journal of Photography 56(2548), 5 March:183. [ Links ]

News of the Day. 1912. Cape Times, 4 October:7. [ Links ]

News of the Day. 1913. Cape Times, 17 May:9. [ Links ]

Nochlin, L. 1991 [1988]. Women, Art, and Power, in Women, art, and power and other essays, edited by L Nochlin. London: Thames & Hudson:1-36. [ Links ]

Peterson, CA. 1989. José Ortiz-Echagüe and his Lino de Duelo. History of Photography 13(3):235--240. [ Links ]

Photographs by Mrs. Caleb Keene. 1907. British Journal of Photography 54(2451), 26 April:317. [ Links ]

Pictorial Photography. 1908. African World Annual 1908/09 (6), 12 December:273. [ Links ]

Picture Postcards by Mrs. Caleb Keene. 1906. Cape Times, 13 November:4. [ Links ]

Portraits at Perry's. 1913. Cape Argus, 26 March:8. [ Links ]

Reginald, 12th Earl of Meath, K.P. 1924. Memories of the twentieth century. London: John Murray. [ Links ]

Reviews. 1903. Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art 30(127), October:87-8. [ Links ]

Rodger, A. 1987. "Minna Keene, F.R.P.S.," Archivist 14(1): 12-13 [ Links ]

Rosenblum, N. 2000. A history of women photographers. New York, London: Abbeville Press. [ Links ]

S.A. Women's Industrial Exhibition. 1912. Cape Argus, 5 March:7. [ Links ]

Social Events. 1921. The Globe (Toronto), 14 September:7. [ Links ]

Social Notes. 1913. South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal 3(34), June:4-5. [ Links ]

Sun Pictures. 1910. Cape Argus, 22 August:3. [ Links ]

The London Salon of Photography's Exhibition. 1911. Photography and Focus 32(1193), 19 September:234. [ Links ]

The South African Lady's Pictorial and Home Journal. 3(30), February:1 [ Links ]

The Work of Mrs. Caleb Keene. 1906. Photo Era: The American Journal of Photography 17(5), November:341. [ Links ]

The Work of The Year. 1906. Photograms of the Year 1906. London: Dawbarn & Ward:40-74. [ Links ]

Thomson, M. 1908. Photography in South Africa. Photograms of the Year 1908. London: Dawbarn & Ward:80-92. [ Links ]

Tilney, FC. 1924. Portraiture and Figure Studies at the London Salon. British Journal of Photography 71(3358), 12 September:547-549. [ Links ]

To our readers. 1910. The South African Photographic Journal 3(3), March:42. [ Links ]

Twenty Five Nations Send Photos to Fair. 1926. The Globe (Toronto), 11 September:19. [ Links ]

University of Cape Town Special Collections. BC 749. Quaker Collection. [ Links ]

University of Leeds Special Collections. 1914-1918. LIDDLE/WW1/DF/009. Jessica Barry Papers-File B (iii). Letters from Minna Keene to Edith Dawson. [ Links ]

Vail, F. 1925. Minna Keene Photographs. Camera 30(1):42. [ Links ]

Venter, IJ. 2014. The South African Lady's Pictorial as a subtle agent of change for British South African women's view of race relations in Southern Africa. Critical Arts 28(5):828-856. [ Links ]

Vertue, E. 1960. Our seventieth year: a short history of the Cape Town Photographic Society. Camera News 5(12):358-363. [ Links ]

Ward, CW. 1906. Woman in Photography. Photographic Monthly 13(154), October:316-7. [ Links ]

Western Cape Archives and Record Service, Cape Town. Vol 3/227, Reference 739. Caleb Keene's Insolvent Liquidation and Distribution Account, 1915. [ Links ]

What Friends are Doing. 1907. South African Friend 1(1), June:9-10. [ Links ]

What Friends are Doing. 1908. South African Friend 1(2), January:9-10. [ Links ]

What Friends are Doing. 1910. South African Friend 1(10), October:2. [ Links ]

Women's Enfranchisement League. 1912. Cape Times, 2 May:10. [ Links ]

Women's Interests. 1906. Cape Times, 1 May:6. [ Links ]

Women's Interests. 1910. Cape Times, 30 November:4. [ Links ]

Women's Library Archives, London School of Economics. 1907-1913. GB 106 7JMS. Papers of Jane Marie Strachey. [ Links ]

Woods, E. 1925 Letter to Minna Keene, 2 Jan. Courtesy of Clive Delbridge. [ Links ]

Young, WR. 2008. The Soft-Focus Lens and Anglo-American Pictorialism, PhD. Dissertation, St. Andrews, Scotland. [ Links ]

1 It is difficult to say for certain whether this 'garden studio' was outdoors or whether it was constructed using a painted background, but having looked at a range of Keene's studio portraits I'm inclined to believe that it was outside. A pattern of mottled light recurs in the background of many portraits but always in a unique arrangement, and with varying degrees of light and shade, suggesting an open air space that was subject to the vagaries of climatic conditions rather than a fixed, painted representation. Furthermore, the features of a garden are often discernable, where a stone wall, fruits, flowers and trees were utilized in the design of the photograph.

2 This appraisal was made following an exhibition of her work displayed at the Smithsonian Museum in 1924. Significantly, this exhibition drew heavily on photographs Keene produced in Cape Town between 1903 and 1913.

3 For example, Keene reproduced many of her photographs as postcards. Research by Malcolm Murphy (2017) attributed a series of picture postcards to Keene that were not widely known to have been published by her. Murphy's insights have been complemented by my own research, and, after meeting with Murphy, I have located other extant examples of Keene's postcards.

4 Already in the process of splitting, the Brotherhood held its last meeting on February 1910, before a decision on Minna Keene's membership could be taken (Harker 1979:121-123, 188).

5 For example, individuals known to have been photographed by Keene include Sir Hely-Hutchinson, the Governor General of the Cape Colony, Viscountess Gladstone, philanthropist and wife of the Governor General of the Union of South Africa, Captain Scott, the arctic explorer, Sir David Gill, Royal Astronomer at the Cape, and John X Merriman, Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. Invariably, the subjects in her "type" photographs remained anonymous.

6 Marian Maxwell, who advertised herself as 'South Africa's Leading Children's Photographer', operated at studio in Johannesburg from at least 1912 (Miss Marion Maxwell 1912). Marion Barnard, operating from Adderley Street in Cape Town in 1906, also specialised in children's portraiture (Miss Marion Barnard: Photographic Artist 1906). Neither of these photographers were nearly as well-known or celebrated as Minna Keene.

7 For an excellent account of early-twentieth century Cape artists and their patrons see Elliott (2015:3975).

8 Keene also photographed Edith Woods at her 'Garden Studio' around 1913 (Elliott & Delbridge 2018/08/26).

9 Established in 1906, the depot provided a commercial space where women could exhibit and sell artistic works as well as culinary and artisanal produce (Women's Interests 1906).

10 Darter's gallery was a fine art gallery located on Adderley Street that had also staged exhibitions of the work of prestigious artists like Ruth Prowse and Constance Penstone during the 1900s.

11 This exhibition occurred shortly after the Conciliation Bill was debated in British parliament, which, if implemented, would have granted women the vote. This may explain why the article chose to dwell on these two images. Women's suffrage was frequently discussed in Cape newspapers, and was evidently of interest to readers.