Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Image & Text

versão On-line ISSN 2617-3255

versão impressa ISSN 1021-1497

IT no.31 Pretoria 2018

That Which We Do Not Remember

Candice Allison

Independent curator and writer, Cape Town, South Africa. candice.allison@outlook.com

A solo exhibition by William Kentridge at Goodman Gallery Cape Town, 30 November 2017 - 13 January 2018.

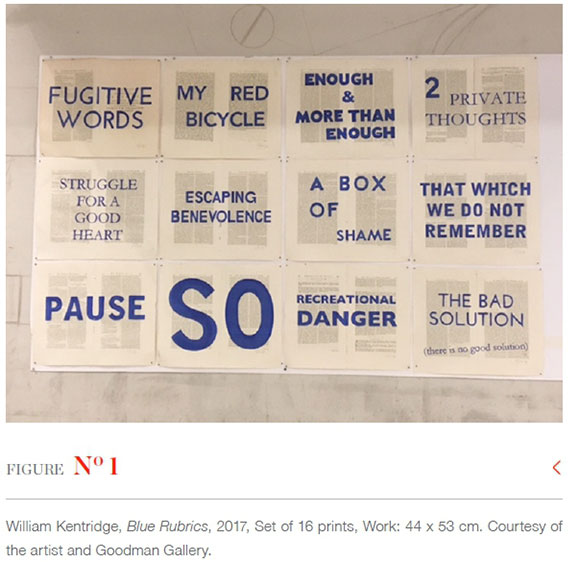

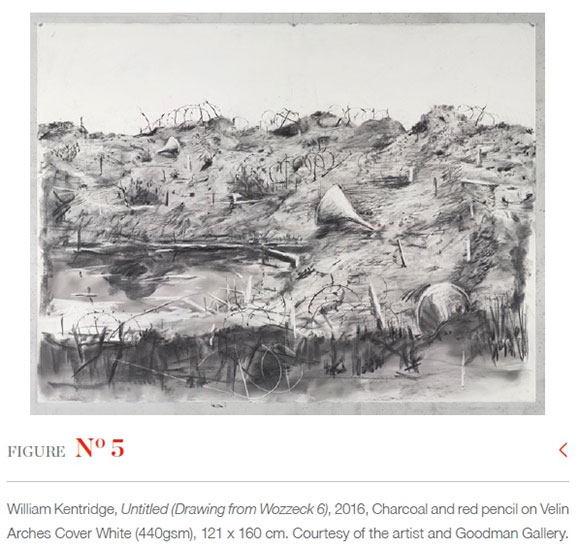

That Which We Do Not Remember presents new work from two of William Kentridge's recent opera productions, Lulu and Wozzeck, alongside several major projects he worked on in between, including the ambitious Tiber river mural project in Rome, and a new series of prints, titled Blue Rubrics (Goodman Gallery 2017:1). It is a rich and dense show, revealing of the artist's approach to discarding, abandoning, and returning to ideas and the very processes of thinking and creating, time and again.

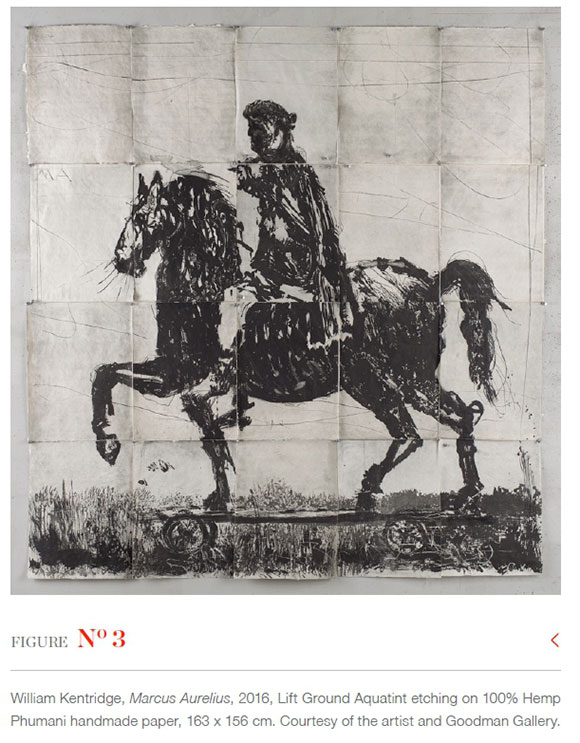

In the prologue of Lulu, the Animal Tamer appears from behind the curtain; whip in hand, inviting the audience to 'step right up, lively ladies and distinguished gentlemen, into the menagerie' (Ross 2007:227). If we imagine Kentridge's exhibition as a menagerie, we will find an array of opulent characters and mysterious creatures, brought together from various territories - the typical tigers and panthers you would expect to find; the cast from two opera productions; a procession of characters who shaped the history of Rome; some founding members of the African National Congress; a boat overflowing with refugees; and the esteemed Madame et Monsieur Manet. The barren, charred landscape - smoky charcoal sketches rendered in Kentridge's signature gestural style, that disregard a start or end point - is constructed to reflect the intention of this menagerie; for entertainment, of course, but the kind of noir, sombre entertainment of the "tragedy" variety. The boundaries of the gallery space(s) - this exhibition is staged across the third floor gallery, viewing room, and ground floor video room - much like the tall stone walls of a zoo, or barbed electric fences of a safari park, confine the characters, and the ideas they represent, into a vast, yet clearly navigable space. With exhibit guide in hand, the audience can move from one character to the next, looking and pointing (petting is not allowed in this zoo), learning the traits and behaviours of each exotic breed. Here, we have Marcus Aurelius: Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher; persecutor of Christians.

There, General Giuseppe Garibaldi: Hero of the Two Worlds; unifier of Italy. Kentridge's cast of characters, for their part, play out the routines they have each been ascribed, over and over, day after day, until the exhibition comes to the end of its run and they are carefully returned to the wooden crates they arrived in and moved on to the next location.

It is at the moment, when you don the headset for Love Songs from the Last Century, the 360° virtual reality video that immerses you in the bleak hyperreal landscape of this world, and you look up to see the artist himself hovering over the scene, that you begin to realise that you, the "viewer", are fulfilling your role as a character in the menagerie of this production. In the final scene, pieces of torn sketches and props depicting fragmented phrases begin swirling around you as Kentridge, the Puppet Master, lowers a fan into the set in a seemingly indifferent act of chaos and destruction. One of the phrases catches my eye before it blows away: 'IT IS NOT TRUE, IT IS NOT TRUE, IT IS NOT TRUE'. And yet, looking beyond the frame of the stage and the text, we are reminded of the power external influence can have on the shaping of how ideas are received; a tension between real life and fiction; and the perceived danger and fear of ideas. Another phrase blows past: 'THE DEAD, THE AWAKE, THOSE ASLEEP'. Which one are you?

Wozzeck is the first opera by the Austrian composer Alban Berg, composed between 1914 and 1922. The opera is based on the drama Woyzeck, which was left incomplete by the German playwright Georg Büchner at his death. From the fragments of unordered scenes left by Büchner, Berg selected fifteen to form a compact structure of three acts with five scenes each (Walsh 2001:61-63). This powerful tragedy tells the story of Wozzeck, a psychologically disturbed soldier who endures ridicule from his superiors and undergoes bizarre medical experiments for payment. His struggles with jealousy and poverty eventually drive him to murder the mother of his child, and accidentally drown himself while trying to dispose of the weapon (Hall 2011:26-38). It was first performed in 1925, initially achieving great success (Perle 1995:67). During the 1930s however, the rising tide of Nazi antisemitism and conservative cultural ideology impacted greatly on Berg, who was professionally persecuted for his association with Jewish composer Arnold Schoenberg. Theatres refused to produce the opera, while sets and scenery were systematically destroyed (Jarman 1989:78-80). Wozzeck was also banned in the Soviet Union as "bourgeois", and in September 1935 his music was prohibited in Germany as 'degenerate music', under the label 'Cultural Bolshevism' (Perle 1995:68).

Despite oppressive cultural censorship, Berg set to work composing Lulu, his second opera in three acts, from 1929 to 1935. It is a bleak rags-to-riches, and eventual return-to-rags story of Lulu, a street waif turned dancer and femme fatale; an object of desire for all men, she exploits and is exploited by their desires and inferiorities. Berg died suddenly before completing the third and final act, and it was premiered incomplete in 1937 (Hall 1997:2). His widow Helene approached Schoenberg to complete the orchestration, which he accepted, but later changed his mind. She subsequently forbade anyone else from completing the opera, and for over forty years only the first two acts could be given complete, with the Act 3 portions of the Lulu Suite symphony played in place of Act 3, usually accompanied by a silent film depicting Lulu's downfall, "liberation" into a life of prostitution, and ultimately, her death at the hands of Jack the Ripper (Kentridge decided to follow Berg's multimedia instruction to shoot a film to go with the palindromic, two-and-a-half-minute Act II interlude). Helene Berg's death in 1976 paved the way for a new completed version of the opera to be made by Friedrich Cerha. The Cerha production was published and premiered in 1979; it received sensational reviews and the recording won the Gramophone Award that year (Huscher 2006:112-114).

In retelling the accounts of how these two operas were created, I can't help but wonder what drew Kentridge to these works. Was it a fascination for the similarities between the combination of manipulation and self-destruction that condemns the protagonists in each story? Did he identify with Berg's envy for the failures experienced by some of his contemporaries, which he seemed to value more than his own (initial) successes (Ross 2007:226)? This appreciation for failure in itself would resonate with Kentridge and the ethos behind his Centre for the Less Good Idea. At any rate, Berg went on to experience his fair share of condemnation at the time of these works by the authorities and music world at large. Did Kentridge select these works, rather, out of his curiosity for the incomplete works, the picking up and reshaping of fragmented ideas that each production represents? A series of rudimentary hand-carved busts, for example, are constructed from what could be woodcut print blocks stained black with ink, portraying characters form Lulu, alongside John Dube and Pixley Ka Isaka Seme, both founders and presidents of the African National Congress. Speaking to Mashabela (2017:[sp]) about the exhibition, Kentridge expands on this fascination: 'Walter Benjamin wrote that it is time to write history as collage, and that collage is the preserve of artists. He understood that in fact there is a coherence to be found in fragments, and that coherence is to be found rather than constructed from these fragments'. It is in the remembering of these seemingly fragmented moments in history, and the reflecting on what we consider, now, to be the absurd and fascist suppression of ideas, that asks us to step outside of the rhetoric of current debates around which artworks, literature, music, or political philosophies should be considered "harmful", and to consider what our love songs from this century will be to the next. What will we choose to remember, and what will we choose to forget?

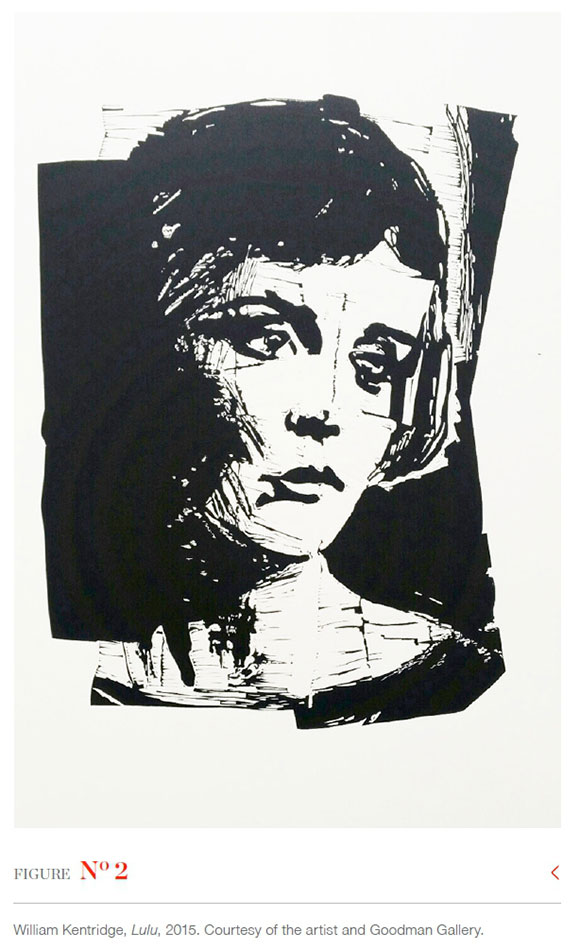

The title of this exhibition is drawn from a new series of words and phrases printed in Lapis Lazuli pigment on found Latin Thesaurus paper, titled Blue Rubrics (a continuation of Kentridge's 2012 Rubrics print series). Here, 'rubric' refers to instructions printed in prayer books, conventionally in red ink. Kentridge perceives these phrases as 'a prod, a goad to the activity of thinking, of understanding how we have to make sense of the world from contradictory fragments' (Goodman Gallery 2017:1). Some of the words appear straightforward and may hold specific meanings - 'history on one leg' is a reference to the toyi-toyi (Mashabela 2017:sp) - but for the most part, the words symbolise Kentridge's attempt to create scenarios where 'completion of meaning' cannot be attained. Speaking to Walls (2015:sp) ahead of his Lulu premier at the New York Metropolitan Opera, Kentridge described in detail how his set design and staging of the show - a whole world constructed by projections of ink drawings representing fragments of thoughts and images, largely of people, collaged one on top of the other to reveal the full drawing - suggested in itself a fragmentation of the object of desire. His question - how do you hold 'who is Lulu' together? (Walls 2015:[sp]) - is mirrored throughout the exhibition by the multiple depictions of Lulu, 'the most captivating creature in the menagerie' (Ross 2007:227), as the many personas attributed to her by others. In keeping with his spirit of unconventionality, Kentridge allows us to keep an open mind about Lulu's character, and who she may eventually turn out to be: 'It's not as if we start with a Lulu and then just execute her' (Walls 2015:[sp]).

Personally, I like to believe that I found Lulu in the kinetic model theatre entitled Right Into Her Arms, comprised of film material made while developing the production of Lulu, projected onto two white mechanically operated canvases interacting with each other in a passionate and violently forceful dance that reveals the anxieties that would have left Lulu feeling compelled to remain in one abusive relationship after the other. The irony of the title in contrast to the action played out, further insinuates that Lulu was not the serpent temptress others made her out to be, as Kentridge seems to point us to the fine line between love, desire, and destruction.

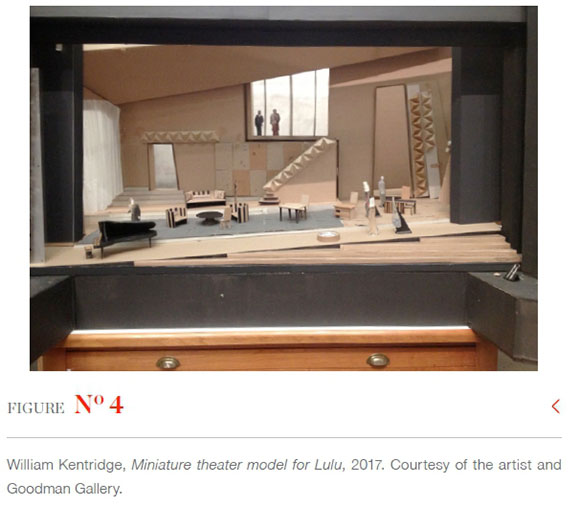

In returning to the introduction of this review, the metaphor of a menagerie as an entry point to making sense of this exhibition seems particularly apt, as the works grouped together are taken from various notable, yet disparate projects that Kentridge has worked on in recent years. Each of the drawings, characters, sculptures, and prints, are simply stand-ins for the real thing. They are samples of ideas, of preparatory sketches; progress snapshots of finished or unfinished works. In their one-dimensional simplicity, or distorted scale (such as the miniature theatre model for Lulu), the viewer is held at arm's length from the monumentality of Kentridge's projects as they appear "in real life". Speaking about 'the stage as a showplace and the drama as a showpiece', Treitler (1989:275) describes how Berg's specifications that actors play multiple roles, along with references in dialogue and musical score to Berg's other opera Wozzeck, as theatrical components, 'sets up in the viewer's mind a perception of the characters as stage creatures'. Just as the prologue to Lulu establishes the separateness of characters and actors, the stage and the world of daily life, this exhibition achieves the same purpose. We know, for example, that a 163 x 156 cm etching of Marcus Aurelius is only one part of an epic 550-meter frieze along the banks of the Tiber River. The exhibition offers an interesting partial view into the working mechanisms of the artist's mind, but it left me wanting more than ever to experience these projects in the flesh. And therein lies the crux - the punchline - by nature of its creation, projects like the Tiber River Mural, "painted" using the reverse process of removing dirt and algae from the river bank walls, ensures their ephemerality (Friedman 2015:[sp]). The real works too will eventually disappear, or in the case of his operas, they will reach the end of their run. All that will be left are the creatures which were plucked from their "natural" environment in order to titillate us with the possibility that they were once wild and free.

REFERENCES

Friedman, J. 2015. William Kentridge Plans Massive, Vanishing Mural in Rome. [ Links ] [O]. Available: https://hyperallergic.com/233209/william-kentridge-plans-massive-vanishing-mural-in-rome/. Accessed: 20 January 2018.

Goodman Gallery. 2017. William Kentridge: that which we do not remember. Press Release. [ Links ]

Hall, P. 1997. A view of Berg's Lulu through the autograph sources. California: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Hall, P. 2011. Berg's Wozzeck, in Studies in musical genesis, structure, and interpretation. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Holden, A. 2001. The new Penguin opera guide. New York: Penguin Putnam, Inc. [ Links ]

Huscher, P. 2006. The Santa Fe opera: an American pioneer. Santa Fe, NM: The Santa Fe Opera. [ Links ]

Jarman, D. 1989. Alban Berg, Wozzeck. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Mashabela, K. 2017. 'Words and Urges': William Kentridge's That Which We Do Not Remember. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.adjective.online/2018/01/11/words-and-urges-william-kentridges-that-which-we-do-not-remember-by-khanya-mashabela/. Accessed: 20 January 2018.

Perle, G. 1995. The right notes: twenty-three selected essays on twentieth-century music. Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press. [ Links ]

Ross, A. 2007. The rest Is noise: listening to the twentieth century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [ Links ]

Treitler, L. 1989. Music and the historical imagination. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Walls, SC. 2015. William Kentridge on Lulu: 'You know there's going to be a body on stage'. [ Links ] [O]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/oct/31/william-kentridge-lulu-opera-metropolitan. Accessed 12 December 2017.

Walsh, S. 2001. Alban Berg, in The new penguin opera guide, edited by A Holden. New York: Penguin Putnam. [ Links ]