Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.31 Pretoria 2018

The caretaker of wounds: pictures of the deposition of Christ in the work of Marcus Glaser

Bronwyn Law-Viljoen

Department of Creative Writing, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. bronwyn.lawviljoen@wits.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The South African artist Marcus Glaser (1936-2007) created several prints of the Deposition of Christ, seemingly to understand, through this important iconographical image, his own position in relation to the western art canon. The works reveal the predilections and anxieties of an artist trained in the classical tenets of high modernism in South Africa of the 1950s and 1960s, and shed light on the ways in which some artists of Glaser's generation responded to the political and art-historical landscape in which they found themselves. The paper considers Glaser's images as exemplary prints in a long line of Deposition prints and paintings, beginning with Albrecht Dürer's (1471-1528) seminal works on the same theme. It also explores the aesthetic anxieties of this individual artist and suggests that they are symptomatic of a particular moment and ethos in South African art of the late-twentieth century.

Keywords: Deposition of Christ, Marcus Glaser, South African art, Printmaking, Albrecht Dürer, Christian iconography.

Exegetical Experiment

let's bandage him

let's hide his wounds

said the old mother.

let us protect him

from the cold cold shrouds

of daylight day.

let us protect him

said the caretaker of wounds

let us hide him hide him

far away

where the beetles

callous as undertakers

shall nip bits off him

bits of flesh

and dry them in the marketplace

and sell them as curios.

- Marcus Glaser (1996:[sp])

This essay extends out of a creative project that I began several years ago when I came into possession, by a series of coincidences, of a collection of work by an obscure South African artist named Marcus Glaser (1936-2007). This unlikely "inheritance" simmered in boxes in my house for a long time - perhaps five years - before I embarked on my more formal engagement with it.1 It is something of an archival and academic windfall to be given, out of the blue, the entire artistic oeuvre of a single artist - the thing that one always hopes will happen and thereby provide one with grist for several academic pursuits over a number of years. It comes, however, with a peculiar burden of responsibility, which I studiously avoided for as long as I could.

Glaser was little known in South African commercial art circles, and so a judgement of his work remains more or less suspended despite his prodigious output over thirty years. His presence in the art world is officially, but tenuously, valorised by a single line in Esmé Berman's Art and artists of South Africa (1969), by one image in FL Alexander's South African graphic art and its techniques (1974) and by a mention in the list of printmakers in the back of Philippa Hobbs and Elizabeth Rankin's book, Printmaking in a transforming South Africa (1997). He appears in no recent histories of South African art, and will no doubt remain largely absent from any future histories, his impact being little felt beyond his own immediate circles.

I did not know Glaser, and had not encountered his work before the moment in which this "story" begins. My desire to look more closely at his artistic output was also not out of any sense of obligation to his memory, but I could not escape its insistent (and, to me, moving) presence in the world.

I had a sense that Glaser, probably like many other artists of his generation, could make art in South Africa only within the private space of his own studio. Setting aside for a moment the specific constraints of Glaser's personal circumstances and the complexity of his intellectual and emotional engagement with the world, the classical training that Glaser had received as a student left him, to some extent, aesthetically and politically stranded (though not unable to make images, as we shall see). That he chose to be primarily a printmaker seems apt, given the inevitable, relative isolation to which his training and his personal and aesthetic predilections would help to confine him.

Glaser's story, for all of its particularities, is a common one in twentieth-century South African art history. Trained in the afterglow of European modernism, and at the same time politically isolated from various African modernisms, South African artists coming of age in the 1950s and 1960s would have had to negotiate their relationship to a set of competing aesthetic and political movements. At the same time, as political and social repression gained traction in this period, "struggle" or "protest" art emerged as the dominant aesthetic register to which artists had to respond. Transcendence of their classical, Eurocentric training would have required assimilation into some imagined "African" idiom, a turn to protest art, or a complete reinvention of themselves and the traditions that they had inherited.

In this context, then, this particular body of work was exemplary not only because of its size and scope, and the remarkable fact that it was largely intact, but also because of its peculiar representation of a matrix of anxieties encountered by white South African artists trained in the 1950s and 1960s and then encountering, as adults and as artists, the socio-political chaos of a country moving towards a possible bloody overthrow of a repressive and racist regime.

The work of Marcus Glaser seemed, at first glance, idiosyncratic, weird, accomplished in many ways, but also representative of an inability to engage either with this regime or with the forces that were seeking to replace it with a just, humane and democratic dispensation.

But despite - or perhaps because of - its "failure", the work, situated as it is on the fringes of South African art history, is worth considering. Of course, there is something quite compelling not only about the impulse of an artist to continue making images in the face of overwhelming political and social forces that he either has not been trained or has no inclination to confront, but also about the way in which the art world relates to and attempts either to absorb, disguise or expel the aesthetic values that such work represents. At the same time, the work itself - the images and writing - poses a number of important questions about the moment in which an artist like Glaser was making art, and sheds light on the reinterpretations by subsequent generations of artists of the images and aesthetic compulsions that Glaser's art epitomises.

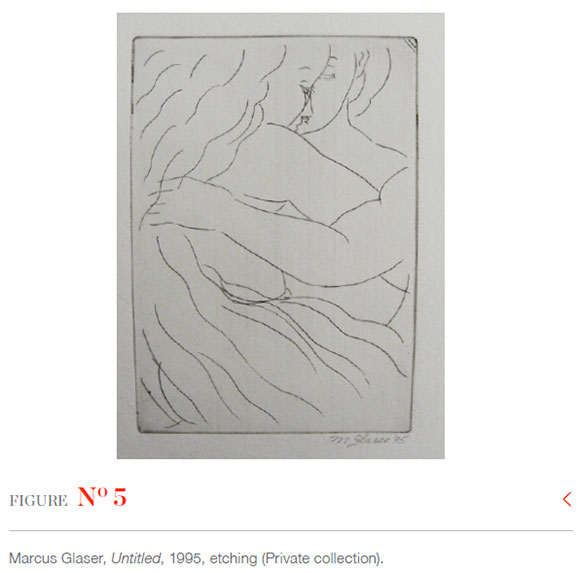

In considering such questions, I did not want, however, to attempt an analysis of the entire oeuvre of Glaser: several dozen paintings, a body of literary work and over five thousand prints and drawings. There is, no doubt, a dissertation on Glaser still to be written, but it is not my intention to do so here. Instead, what I propose is to pursue a thread suggested to me by two prints in Glaser's oeuvre, both representing an important moment in the Christian Passion narrative: the Deposition of Christ. In studying his archive, I had become particularly interested in his representation of classical religious - Christian - iconography. This is a slender but insistent thread in his sizeable body of images, and my encountering it in his earliest paintings and again in several prints sent me to his substantial art library to try to understand how he might have read such images. This in turn led me to contemplate his etchings of the Deposition of Christ as a way of finding some answers to the questions I had begun to pose about Glaser, his milieu and those who came immediately after him.

The literary and artistic preoccupations of this minor Johannesburg artist, evidenced by his own artmaking and writing as much as by his impressive library, point to a desire to inherit a tradition and to find a place in a canon. This might have been achieved by any number of means, but the presence of at least two works on the Deposition theme is not incidental in the oeuvre of an artist like Glaser. In my attempt to understand the significance of this work I turned to other examples of the same image in Glaser's contemporaries, and to my surprise found relatively few treatments of the Passion narrative, and even fewer of the Deposition. This was surprising because of the rich tradition in South African art, and especially in printmaking, of biblical themes and images. But a search through the work of artists like John Muafangejo, Eric Mbatha, Cecil Skotnes and others yielded surprisingly little on the Passion. Notable exceptions were Azaria Mbatha's etching and aquatint, Crucifixion (1966); Nathaniel Mokgosi's etching, Crucifixion (1971); Diane Victor's drawing, The Ultimate Adoration (1989); Charles Nkosi's four linocuts, Pain on the Cross I-IV, from his 'Crucifixion' series (1976); and Eric Mbatha's etching, Composition for Relief Sculpture (1972), which looks like a Deposition, but is probably a Crucifixion.2

I am not attempting to argue that the image of the Deposition of Christ is any more or less important than any other image in Glaser's oeuvre. I can infer its importance through its several appearances in the thirty-year trajectory of the artist, but this may simply be part of a more general impulse to repeat images, to try variations on a theme. What I am suggesting, however, is that the Deposition of Christ - as an image that appears in Glaser, as a key image in the western canon and with a particular place in the history of printmaking - is a point of entry, a test case. It allows me to consider a number of questions about the psychic inheritance with which South African art has had to contend.

The Deposition has an important place in western art, but it is not the same as the image of the Crucifixion, as we shall see. In the iconographic hierarchy of western art, it is the less understood of the Passion images, the less easy to contend with, the more ambiguous.

One fairly obvious place to begin if one wants to consider Christian iconography in western art in general and in printmaking in particular, is with Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).3And if one is looking for something emblematic in Dürer's many representations of the Deposition of Christ as a moment in the larger Passion narrative, then The Descent from the Cross from his 1510 series of woodcuts 'The Small Passion', is surely a work that bears considering. I have no idea if this image was of any particular interest to Glaser (more than any other pictures that he looked at in his books and on his visits to European museums and galleries in his twenties). He did, however, own copies of The complete engravings, etchings and drypoints of Albrecht Dürer (Strauss 1972) and Erwin Panofsky's seminal The life and art of Albrecht Dürer (1945). He also owned many books on Renaissance art as well as on the history and techniques of printmaking, in several of which the work of Dürer features.

These facts do not serve as evidence for anything other than a general interest in Renaissance art and in printmaking, but the point is not to try to establish anything factually true about Marcus Glaser the artist. Rather, it is the image itself that interests me, and how this particular work, in its multifarious and long history, might shed some light on how this South African artist (and no doubt others of his generation) thought of himself in relation to the European tradition that he inherited and into which he was inserted, by choice or training or exposure, or simply by the vagaries of history. Glaser's interpretation of the Deposition provides insights into the ways in which South African art, more generally, has absorbed, assimilated and deconstructed European Christian iconography.

Some Depositions

... Can't you see the magic of it? Here is a man who is not a magician - and yet he had us all believing that he was one. Right until the very end. It was the supreme performance of magic .

- Marcus Glaser (from 'The Magician', Glaser 2001:54-55)

The Deposition of Christ in western art - also called the Descent from the Cross - refers to the moment in the Passion narrative in which Christ's body is removed from the cross, just prior to its being placed in the tomb, though the latter is also often referred to as the Deposition. The usual order of images in a Passion sequence is the Crucifixion, the Descent from the Cross (the Deposition), the Lamentation, the Entombment (also the Deposition), and then the Harrowing of Hell, in which Christ is shown descending to hell just before his resurrection. In Passion iconography, the Deposition is the thirteenth station of the cross. In Greek the word for it is Apokathelosis.

In addition to paintings and prints, there are countless frescoes, mosaics, figurines, relics and sculptures of the Deposition. There were also Deposition rites and plays performed throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, fading from view in the late sixteenth century. These rites tended to encompass the descent of the body of Christ from the cross, the Lamentation and the Entombment.4

Amy Knight Powell (2012:143) notes that 'pictures of the deposition first appeared in the ninth century, some four hundred years later than the first images of the crucifixion'. This fact is of some significance, since it would suggest that the iconography of the removal of the dead body of Christ from the cross opened up a different set of questions than the Crucifixion itself about the relationship of the human to the divine, both in the person of Christ and in the devotee looking at an image of Christ. These questions might not have been possible prior to the period in which images of the Deposition began to appear and they suggest that the Deposition sets in motion an entirely different emotional and intellectual response in the believer/viewer (as well, of course, in the artist depicting the image). Here is the body of Christ now confirmed in its corporeality. It passes out of reach of the divine into an earthly realm represented by those who carry the body from the cross, who must, quite literally, hold the human weight of Christ in their arms. It is a moment, prior to the "sensational" mourning (with all of its aesthetic possibilities) such as is represented by the Pietà, in which the emptied body of Christ5 is present without the mediation either of the mechanism of the cross or of the mourning of the mother figure. It is a moment between other more clearly significant or symbolically charged liturgical moments.

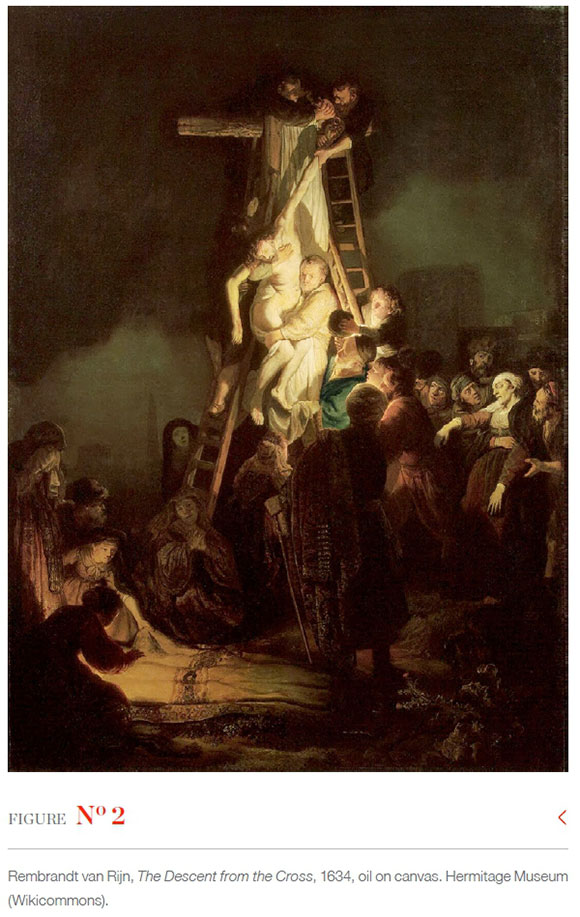

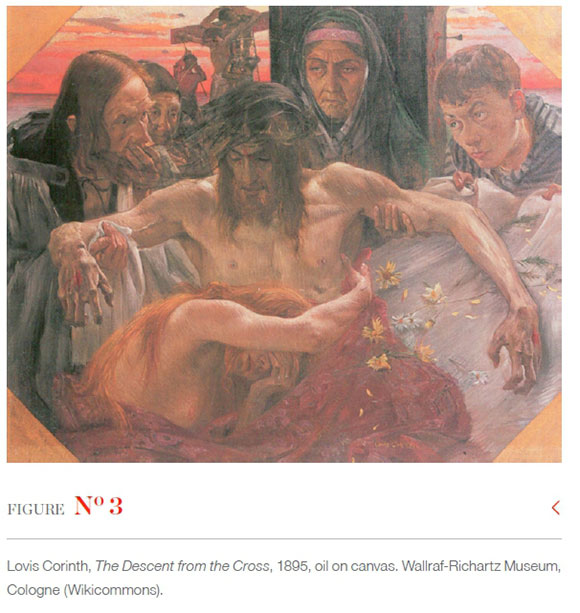

Put in a slightly different way, the Descent from the Cross shows us the people around Christ struggling with the pure physics of his deadweight body, with its failure to cooperate (as it cooperated, so to speak, in the Crucifixion). The artist representing this event must have in mind the particular complexities of movement in such a situation: they must consider the distribution of weight of a falling, earth-bound body upon and across the bodies of those who must manage this distribution from below and positioned awkwardly on a ladder. The artist must weigh up these considerations against the symbolic potential (and perils) of the idea of a dead God.

The artists who painted, drew or printed Deposition images are scattered across various canons. Here are some (perhaps to be read as a kind of prose poem of/on the image):

Enrico di Tedice, c. 1260s, oil on canvas; Corso di Buono, c. 1280, tempera on panel; Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1308-1311, tempera on panel; Simone Martini, 1333, tempera on panel; Hans Memling, c. 1400s, oil on panel; Jacquemart de Hesdin, prior to 1402, ink and tempera on parchment; Limbourg brothers, c. 1411-1416, tempera and gold leaf on vellum; Giovanni di Paolo, 1426, tempera and gold leaf on panel; Fra Angelico, 1432-1434, tempera on panel; Rogier van der Weyden, 1435, oil on panel; Bartolome Bermejo and Martin Bernat, c. 1480, oil on panel; Andrea Mantegna, c. 1465, engraving; Martin Bernat, c. 1487, oil on canvas; Master of the St Bartholomew Altar, c. 1490, oil on panel; Benozzo Gozzoli, 1491, oil; Hans Holbein, 1494-1500, oil on panel; Gerard David, 14951500, oil on linen; Master of the St Bartholomew Altar, c. 1500, oil on panel; Filippino Lippi and Pietro Perugino, 1504-1507, oil on panel; Raphael, 1507, oil on wood; Jan Sanders van Hemessen, c. 1500-1550, oil on canvas; Albrecht Dürer, 1508-1510, woodcut; Il Sodoma, 1510-1513, oil on panel; Luca Signorelli, 1516, oil on wood; Ugo da Carpi, c. 1518-1520, woodcut; Jan Mostaert, c. 1520, oil on panel; Marcantonio Raimondi, 1520-1521, woodcut; Fiorentino Rosso, 1521, oil on wood; Lucas van Leyden, 1521, engraving; Ugo da Carpi, c. 1520-1527, chiaroscuro woodcut from three blocks; Fiorentino Rosso, 1528, oil on wood; Jacopo Pontormo, 1528, oil on wood; Agnolo Bronzino, 1540-1545, oil on wood; Pieter Coeck van Aelst, c. 1540-1545, oil on panel; Francesco Salviati, c. 1547, oil on wood; Jacopo Tintoretto, 1559, oil on canvas; Antonio Noguiera, 1564, oil on panel; Alessandro Allori, c. 1563-1567, oil on wood; Simone Peterzano, 1584, oil; Diana Scultori, 1588, engraving; Karel van Mander, 1596, pen and ink on paper; Jacques de Gheyn II, 1596-1598, engraving; Christoph Murer, 1599, pen and ink wash; Caravaggio, 1600-1604, oil on canvas; Peter Paul Rubens, 1612-1614, oil on panel; Anthony van Dyck, 1615, oil on panel; Peter Paul Rubens, 1617, oil on panel; Anthony van Dyck, 1619, oil on canvas; Lucas Vorsterman, c. 1622, engraving; Anthony van Dyck, 1629-1630, oil on panel; Nicolas Poussin, 1630, oil on canvas; Cornelis Schut, 1630, oil on canvas; Rembrandt van Rijn, 1633, etching and drypoint; Rembrandt van Rijn, 1632-1633, oil on panel; Anthony van Dyck, 1634, oil on panel; Charles le Brun, 1642-1645, oil on canvas; Eustache Le Sueur, 1651, oil; Rembrandt van Rijn and Constantijn van Renesse, 1650-1652, oil on canvas; Rembrandt van Rijn, 1654, etching and drypoint; Lucas Giordano, c. 1659, oil on canvas; Jean-Baptiste Jouvenet, 1697, oil on canvas; Thomas Gainsborough, 1766-1769, oil on canvas; Giovanni Tiepolo, 1772, oil on canvas; Corrado Giaquinto, c. 1754, oil on canvas; Jean-Baptiste Regnault, c. 1789, oil on panel; Pavel Djurkovic, 1801, oil on canvas; Richard Parkes Bonington, c. 1820s, oil on panel; Eugene Delacroix, c. 1839, drawing; Gustave Doré, 1865, woodcut; Arnold Böcklin, 1876, tempera on panel; James Tissot, 1886-94, watercolour and graphite on paper; Paul Gauguin, 1889, oil on canvas; Jean Béraud, 1892, oil on canvas; Lovis Corinth, 1895, oil on canvas; James Tissot, c. 1884-1896, gouache and watercolour on paper; Karoly Ferenczy, 1903, oil on canvas; Lovis Corinth, 1907, oil on canvas; Gustav Jagerspacher, c. 1908, oil on canvas; Emil Nolde, 1915, oil on canvas; Max Beckmann, 1917, oil on canvas; Otto Baumberger, 1918, lithograph; Max Beckmann, 1918 (published 1919), drypoint; Ludvig Karsten, 1925, oil on canvas; Waldemar Flaig, 1925, oil on canvas; Sybil Andrews, 1932, linocut; Marc Chagall, 1941, ink and gouache on paper; Graham Sutherland, 1946, oil on board; Bernard Brussel-Smith, 1948, linocut; Salvador Dalí, [sa], etching; Rico Lebrun, 1950, Duco on board; Albert Adams, c. 1955, etching; Albert Adams, c. 1955, etching and aquatint; Albert Adams, c. 1955, etching; Albert Adams, c. 1955, etching; Tim Ashkar, 1956, oil on canvas; Albert Adams, 1959, oil on canvas; Bob Thompson, 1963, gouache and watercolour on paper; Azaria Mbatha, [sa], linocut; Eric Mbatha, 1972, etching; Marcus Glaser, c. 1974, etching with aquatint; Marcus Glaser, [sa], etching with aquatint; Diane Victor, 1989, charcoal and pastel on paper; Jacek Andrzej Rossakiewicz, 1990, oil on canvas; David Folley, 1995-1996, mixed media on canvas; Alena Antonova, 1997, drypoint; Diane Victor, c. 2001, etching and aquatint; Diane Victor, 2002, charcoal and pastel on paper; Graeme Mortimer Evelyn, 2006, acrylic and ink; Nonye Ikegwuoha, 2012, oil on canvas.6

Biography: Marcus Glaser

I can actually remember being born. - There was a sudden burst of bright light - I was alive, aware - I was howling blue murder - I was lifted up - a babble around me - utter chaos. Nothing had been fed into me - no human mores, taboos, hatreds, loves - I was purely an empty shell. - Marcus Glaser ([sa]o:1)

I am the great Alberto, indeed. Though you would not think so now. I am, or was, the world's greatest escape artist ... I became very famous indeed. I started off in front of le Centre Pompidou, you know; the great "piped" highrise; that monstrous structure that some consider very beautiful ... - Marcus Glaser (from 'The Escape Artist', Glaser 2001:64)

Glaser was born on 24 June 1936 in Johannesburg. His father, of whom he apparently never spoke, though there is one mention of him in his incomplete memoir, was German and his mother's parents were from Latvia (Glaser notes in his memoir that his parents spoke Yiddish at home).7 He took art lessons as a child with the famous Roza van Gelderen, a Dutch Jewish woman who, with her partner Hilda Purwitsky, was a pioneer of liberal school education in Cape Town.8 In the late 1950s, he was enrolled in Art History and Fine Art at the Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town (UCT) for about a year (studying sculpture under Lippy Lipshitz).9 Then he registered for a BA (Fine Art) at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) and although he studied for two or three years (interrupted by a stint in the army in Potchefstroom) he did not complete his degree. In about 1958, on a trip to London, he enrolled at the Chelsea Polytechnic for Sculpture, but stayed only two days because 'there was too much else to do'.10

Glaser seems to have had a few exhibitions early in his career: some while a student at Wits, one at Vredolyak House at the Zionist Offices in Johannesburg, and one with Joe Wolpe in Cape Town in the mid 1960s.11 He mentions, in passing, other exhibitions in Johannesburg and Cape Town, but provides little detail in his memoir.

He worked as an illustrator for the Cape Argus, sketching mostly for the arts pages of the newspaper in the days before photographic illustration.12 Later he did illustrations for the poetry journals New Coin, Contrast and Carapace. Several of his own poems were also published in these journals over the years.

Beginning at least as early as 1965, Glaser self-published eighteen books, most of them illustrated by himself. These contain stories, plays, poetry and "literary vignettes". In 1993, he published a collection of short stories, The unquiet love, with Snailpress, and in 1996 a volume of poetry with Firfield Press called Unmitigating circumstances.

Glaser's visual art comprises mostly drawings and prints (etchings, lithographs and linocuts), but also some paintings, the earliest of which are the most interesting. He destroyed a number of paintings he was working on just before his death, and the few that do remain from that period are unexceptional.

By all accounts, Glaser was an extremely quiet and shy man. He had strong opinions about art and literature, which he expressed in his memoirs and in one or two essays published in newspapers (but only mentioned in his memoirs), and his own artistic work was deeply influenced by the European artists he had studied at art school and whose work he had seen in museums in London and Paris in 1958. He amassed a substantial library, which included an impressive collection of art books, as well as many volumes of poetry and short stories. His own art suggests the influence of European Renaissance painters, of important nineteenth-century engravers and illustrators (Corot, Doré, Cruikshank, Beardsley), and of the Impressionists, Dadaists and Surrealists (Max Ernst in particular). There were few, if any, books on contemporary art in his library.13

That Glaser was primarily a printmaker is key to making sense of his work. Making prints by hand on a press is a very particular kind of artistic and technical process involving far more than just drawing on paper. The artist who prints his or her own work has to master a range of skills. They must know, if they are etching, engraving or doing drypoint, how to draw in reverse on copper or zinc plates with sharp instruments, how to soak, cut and press paper (an organic and by no means inert material), how to mix and roll out inks, how to use acids and other volatile liquids and substances. Most artists interested in making prints collaborate with a printmaker and seek the assistance of a publisher to finance the production of the work and to sell the editions. The history of printmaking is full of stories of such collaborations, and many famous printmakers and publishers have acquired some of their own celebrity through their associations with even more famous artists.14

Glaser, however, seems never to have sought such relationships. He worked in his studio at the back of his house in a suburb of Johannesburg, doing all of these things completely alone for three decades. He benefited neither from the technical assistance of a fellow printmaker, nor the marketing skills of a good publisher. Indeed, he seems hardly to have had an audience at all for much of his visual work (except the drawings published in poetry journals - for which he would not have been paid very much - which had a relatively small readership).

Glaser's eighteen self-published books were produced in small editions, and almost all of them combined images and text. The books have a homemade feel to them: Glaser photographed his own prints or drawings, did the layout of the books himself, and had them locally printed in small quantities (editions of 200, 100 or 80) on inexpensive paper. In respect of contemporary design, they are unremarkable. They are, however, a record of an artist's obsession with words and images. He seems to have considered the two elements of equal importance in his publications, and one is hard pressed to say which came first. Some of the books display a coherent relationship between image and text (his play The dream of Rosita, for example). But in others, the relationship appears random, as though Glaser simply gathered up what verse and pictures he had made and put them all together in book form. Indeed, in a press clipping that Glaser kept, the books are described as "annuals" by an admiring critic who suggests that he had simply collected in them all the work that he had done during the year.

Glaser's publications are not so much illustrated books - words with accompanying/ illustrating images - as artist's books, though it is not clear whether he himself would have described them in this way, or whether he intended them to have the artistic "valency" one might associate with an "artist's book". But certainly they were important enough for him to devote effort and not inconsiderable expense to making them. At the same time, Glaser's texts (even without the images) are surprising. He never wrote a novel but did produce poetry and full-length plays (whether or not he intended the latter ever to be performed is unclear, though he does record the performance by the UCT drama school of two of his plays - he was, at this point, working as an illustrator at the Cape Argus and was no longer a student) (Glaser [sa]o:56). In addition to these, he wrote many literary "fragments", or what I have called "vignettes", which have much in common with his visual work in terms of their aesthetic sensibility and oddness.

The Influence of Anxiety

The room was broken into. The cupboards were full of moths. You heard an eerie cry. It was as if the room were wounded and bled and cried.

Taxis, they had said. Taxis or drab grey cars ... That took you and never brought you back. Bandaged patients or patients whole or sound - it made no difference.

If you look into the cupboard there, you see the moths' lantern eyes. Listen close. A myriad moths' teeth munching. Silently devouring your wedding gown. All falling to pieces.

The bride shall be naked. The groom shall be stripped bare.

The wounded room. The room of forgetmenots. The patent tears. (They too shall be forgotten .)

- Marcus Glaser (from 'The Wounded Room', Glaser 2001:1)

Despite his own excellent draughtsmanship and his artistic idiosyncrasies, Glaser returned time and again to the artists he admired. It may well be that, quite apart from his personal inhibitions, Glaser never escaped his artistic fathers enough to emerge as an artist in the contemporary "public" sense of the word. In an uncanny echo of his apparent anxiety about his artistic longevity, the poem in the epigraph at the start of this part of the essay contains a reference to Duchamp. Glaser appropriates here Duchamp's 'bride stripped bare' in a text that reflects on the fragility of the aesthetic object (as suggested by the wedding dress). The anxiety about disintegration and forgetting expressed in the poem is prescient in respect of his own myriad works on paper.

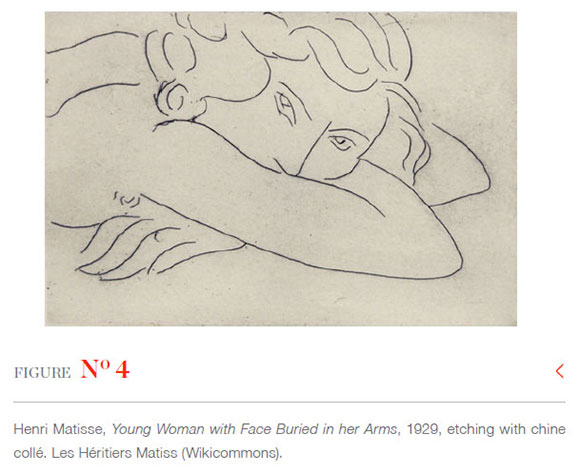

Glaser's drawings and prints evince an extraordinary ability not so much to plagiarise as to imitate line, mood and gesture. There are, amongst his many monochromatic sketches, for example, images that borrow from the minimalist drawings of Henri Matisse (1869-1954): Glaser's nudes and portraits in particular imitate the fluidity and dexterity of Matisse's.

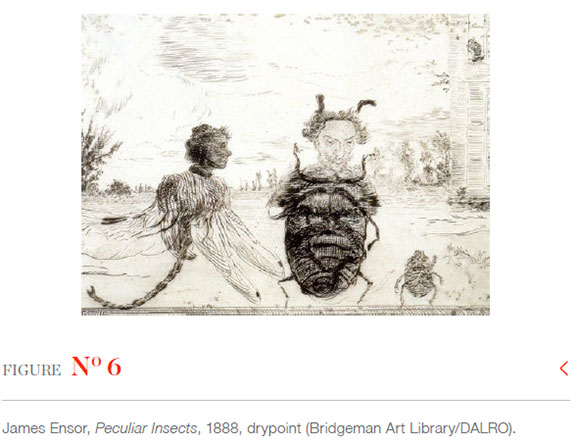

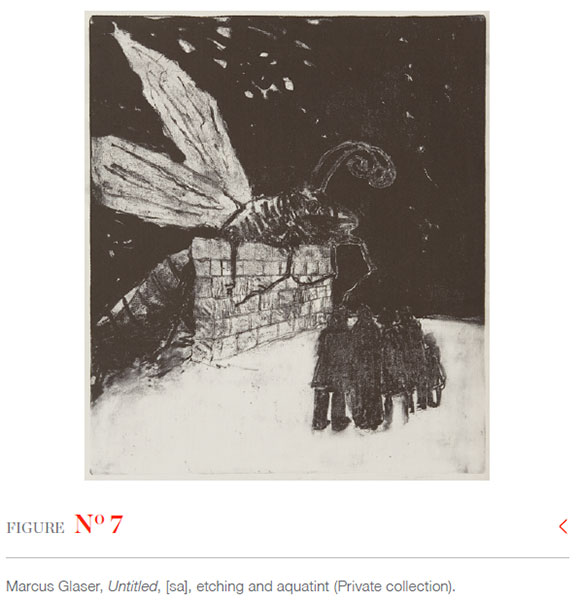

There are imitations of Francisco Goya's (1747-1828) tortured prints from 'The Disasters of War' series and of the Belgian artist James Ensor's (1860-1949) grotesque figures, masks and insects.

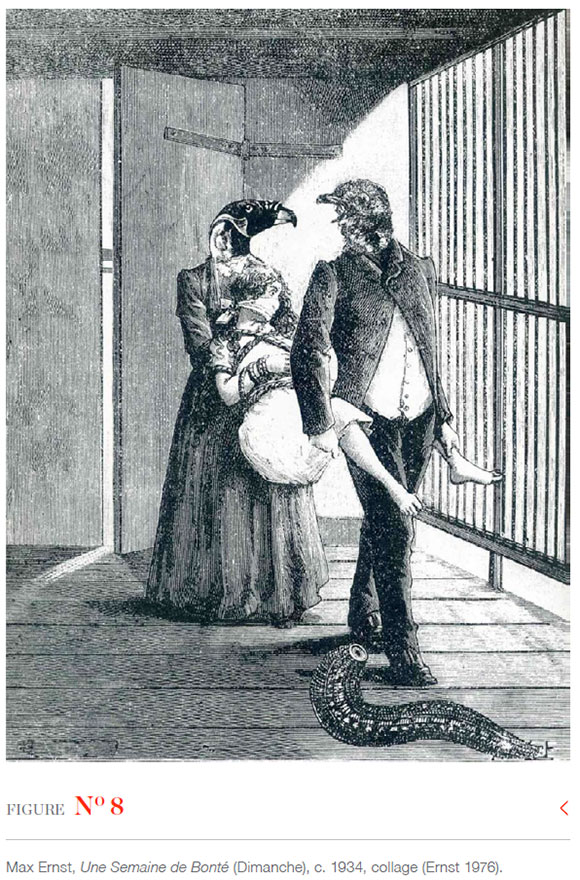

The surrealist collages of Max Ernst (1891-1976) were an important preoccupation in the many prints of figures with strange bird heads and stork-like legs. Glaser owned well-used copies of Ernst's important surrealist books, The hundred headless woman (made with André Breton and published in 1924) and Une semaine de bonté: a surrealistic novel in collage (1934). The images in these publications seem to have provided Glaser with a legitimate language into which he could channel his formal, aesthetic and psychic preoccupation with fantastical figures. He was able to experiment formally with surrealism without necessarily being fully wedded to the aesthetic philosophy of Breton and his peers. He seems, nonetheless, to have been interested in the psychology of the surreal, and particularly in the psycho-sexual imagery in the work of artists like Ernst (which is also given particular expression in Glaser's literary work).

This ability to imitate the work of influential artists bears thinking about in relation to Glaser as a printmaker. The history of printmaking is partly about its function as a copying or reproductive art. Indeed, three or four broad strands in printmaking as an art form can be traced: the print as a fair likeness of something; the print as a direct reproduction of another image; the print as a counterfeit of something (standing in for, or as witness to, the real thing); and finally the print as a form separated from all of the above - as an artwork on its own terms. While likeness, reproduction and counterfeit seem, to the contemporary reader, hardly worth distinguishing from each other (except that the last has its own particular history in relation to crime), it is important to note that the evolution of these terms and their relationship to images are deeply implicated in how we have come to think of artistic representation over the last four hundred years: what we accept as a "natural" relationship between an object and its possible representation in an artwork was by no means self-evident in the sixteenth century. Peter Parshall (1993: 554) observes:

Throughout the Renaissance and beyond, the various senses of imitation, illusion, likeness and reflection continued to be discussed in their contingent and perplexing relation to the problem of artistic invention. And there can be no doubt that the more sophisticated Renaissance thinkers recognized early on the immense practical and metaphysical complexity underlying this issue.

An analysis of this complexity and the evolution of each of these terms is beyond the scope of this essay,15 except to note that a printmaker working in the twentieth-century, particularly one who, like Glaser, oscillates between (quite legitimate) claims to originality on the one hand and imitation on the other, inherits the multifarious functionality and intention of printmaking as an artmaking medium. This in turn makes his own tendency to imitate the gestures of his forebears a more complicated matter. It could not reasonably be argued that Glaser deliberately set out to copy, reproduce or counterfeit (in the Renaissance sense of these terms), but rather it seems likely that he was constantly seeking a language that he could make his own, and in the process, he often made art like the other artists with whom he was most familiar or he most admired. (It is ironic that one of the few moments in which Glaser engaged publically with the art world was in an essay in which he expressed ire that a sculpture by another artist was copied from an etching he himself had made in 1972).16

Also beyond the scope of this essay is of course the dense theoretical history of copying, stretching from Plato's conception of illusion or reflection all the way through Baudrillard's postmodern notion of the simulacrum or the hyperreal (essentially his rescuing of the copy from its supposed inferior relationship to the original). For the printmaker, difference, repetition and copying are closely allied notions, each expressing the relationship of the printed image to the thing it represents and to the print's ongoing "double" repetition of that thing and of itself as an image. Glaser's imitations of other artists lack the irony of Baudrillard's simulacrum, but are not without a certain art-historical reflexivity and an aesthetic self-consciousness.

Glaser's Depositions

hold the transparent faces

up to the sun,

let the sun burn through.

tame the lightning, in the eyes,

the thunder in the mouth.

press ear to ears ...

hear music within? ...

it is a dolorous sound .

0 mother, mother,

1 go to bed late.

I rise up early

for fear of the fate

of listening to you.

ah, then the tears .

of your insufferable death

-Marcus Glaser (1996:[sp])

Glaser produced a number of religious artworks, mostly with Christian themes, though he himself was Jewish. One of the earliest paintings (c. 1965, oil on board) is a stark and haunting Christ figure done in grey and deep scarlet. He seems to have made such works not out of any religious sensibility, but rather through a desire to include in his oeuvre references to a tradition of religious painting and printmaking. Mastery of such subjects might have been a way of confirming to himself his own place in this tradition and hence in the western canon in which his 1950s art education, and his own aesthetic predilections, had immersed him.

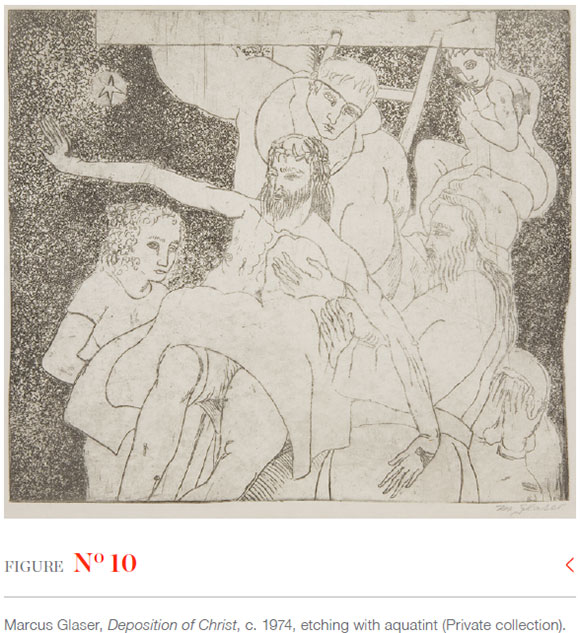

In 1974, FL Alexander's seminal book on South African graphic art and its techniques was published by Human & Rousseau. The section on 'deep etching' is illustrated by Glaser's etched representation of the Deposition of Christ. Given the dearth of material on Glaser, it is remarkable that this image makes it into the first major book on graphic art in South Africa, and its presence here suggests that for a short time Glaser was regarded, at least amongst printmakers, as a noteworthy proponent of the mediums of printmaking.

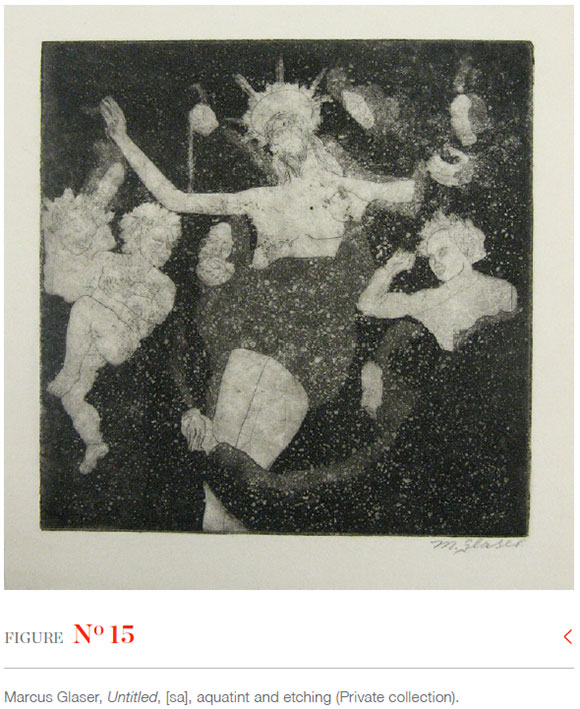

Glaser's Deposition owes much to the western iconography of the image and shows him working to represent the broken body of Christ and the drama of this significant moment in the Passion story. This, however, is not a devotional print, but rather a working through of Glaser's own concerns as a draughtsman and printmaker. There are elements of the image that suggest his recollection of important Deposition pictures in the canon. The halo, present in western art from as early as the fourth century, is common in fifteenth century Netherlandish painting and in later Renaissance works, after which it begins to disappear. It is represented in Glaser's Deposition as a circle emanating from the back of Christ's head, and transecting the face of the figure behind him. Unusually, though, the circle of the halo is echoed in a lopsided pentagram or star in the top left corner of the print, the significance of which is difficult to guess at.17

The five figures surrounding Christ, however, bear little resemblance to the characters of the Passion in the classical images with which Glaser would have been familiar: the paintings of Rogier van de Weyden, Tintoretto, Caravaggio, Rubens and Rembrandt, and the sixteenth-century prints of Dürer. Instead, Glaser seems to use them partly as exercises in figure drawing. This is particularly evident in the floating nude in the top right quadrant of the print.18 Glaser would appear to be intent here on a consideration of the Deposition in purely aesthetic terms, as an exercise in clustering a group of figures around a central drama whose import is already known. In other words, the Deposition is important to Glaser because it allows him to appropriate a visual and symbolic language that has long been associated with this image in the western canon. At the same time, he can insert into the historical image his own interpretation of the tableau, using iconographic elements for some parts and ignoring the iconography elsewhere.

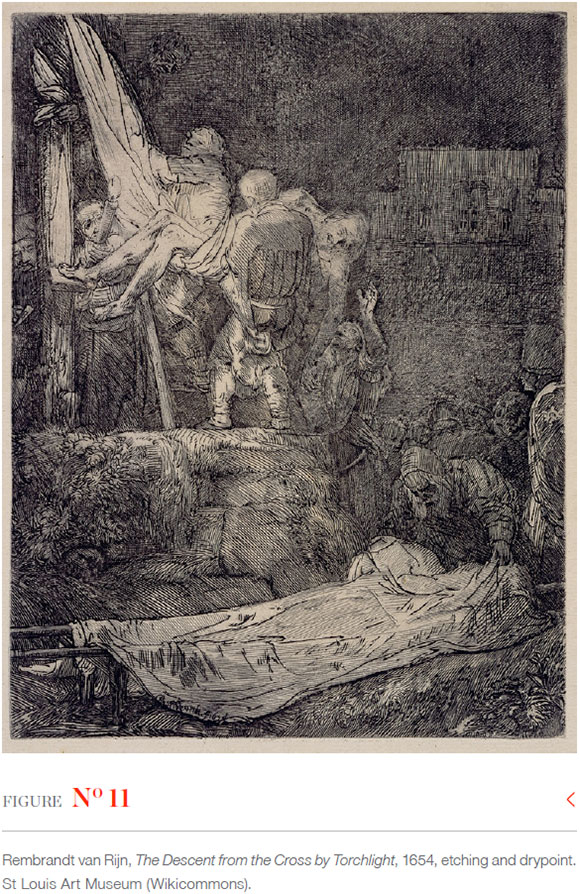

Glaser's printmaking technique looks nothing like the nineteenth-century representations of the famous illustrators of that period such as Gustave Doré, whose work he was clearly interested in. Rather, it is images like Rembrandt's late etching and drypoint version of the Deposition, The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight (1654), that are more obvious precedents for Glaser, but more for questions of technique than of composition and symbolism. Rembrandt's view of the scene is at a slight remove and the pathos is generated through the mood and the placement of figures rather than through the emotion depicted on the faces of the participants. By contrast, Glaser is up close to the faces of Christ and those surrounding him and he suggests emotion through the way the body of Christ is carried and through the gesture of the figure in the bottom right corner.

Glaser works into the background of the print in order to create something like the dark mood of Rembrandt's scene, but where a deep network of etched lines creates a dense black background in the Rembrandt print, Glaser relies on aquatint to give an atmospheric stippled effect (no doubt in reference to the aquatint backgrounds of some of the etchings in Goya's The Disasters of War series).

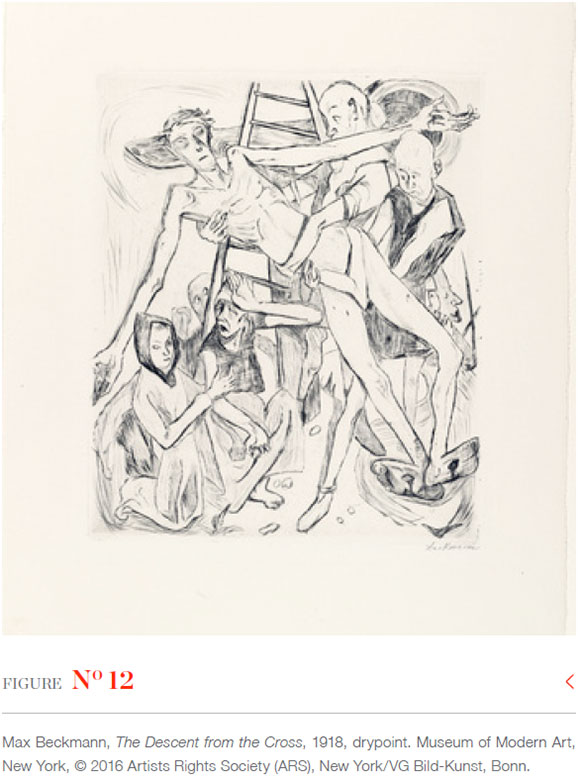

Unlike the highly detailed figure and facial drawing in the Rembrandt (achieved through a drypoint line scratched directly onto the plate) Glaser's rendition of the figures in etched (rather than drypoint) lines owes more to the schematic and gestural lines of modernist interpretations of the image, such as he knew from Max Beckmann's 1918 drypoint, Descent from the Cross (produced after Beckmann's oil of 1917). Indeed, there is a striking similarity in the arm gestures of the Christ figures in Beckmann and Glaser and a similar emphasis on the linear clarity of the central figures.

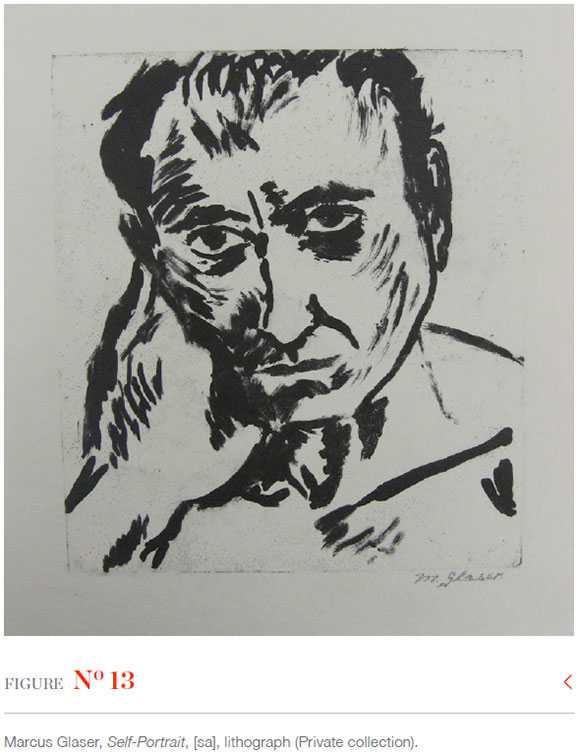

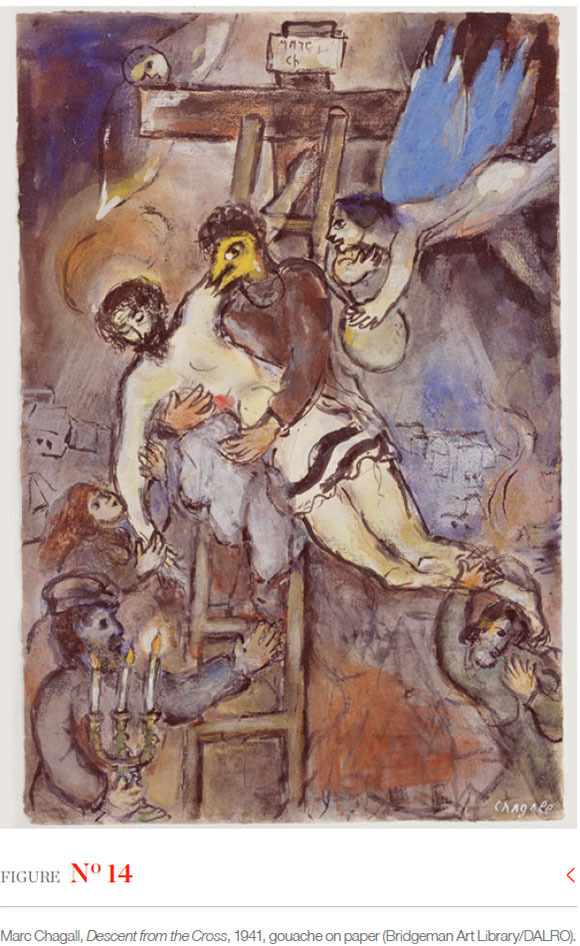

Glaser retains the iconography of the ladder leaning against the top of the cross (a blocked-out rectangle of creamy paper) but leaves out the label usually attached to the top of the cross with the lettering INRI.19 Interestingly, in the 1941 gouache Deposition by another Jewish artist, Marc Chagall, who is represented in Glaser's library, the lettering on the cross is replaced by the artist's own name. My speculation is that Glaser's insertion of himself into the image comes by way of the figure directly behind Christ (usually Joseph of Arimathea in traditional versions of the image), who bears some resemblance to Glaser himself, particularly the version of him presented in an undated zinc lithograph.

There is little in Glaser's image, however, that makes reference to the overt Jewish symbolism of Chagall's Deposition, except that perhaps Glaser's five-pointed star is a reference to Kabbalah, in which both the pentagram and the seven-pointed hexagram are important. (There is, it must be said, scant evidence to suggest an overt interest in Kabbalah in Glaser's other literary and visual works).

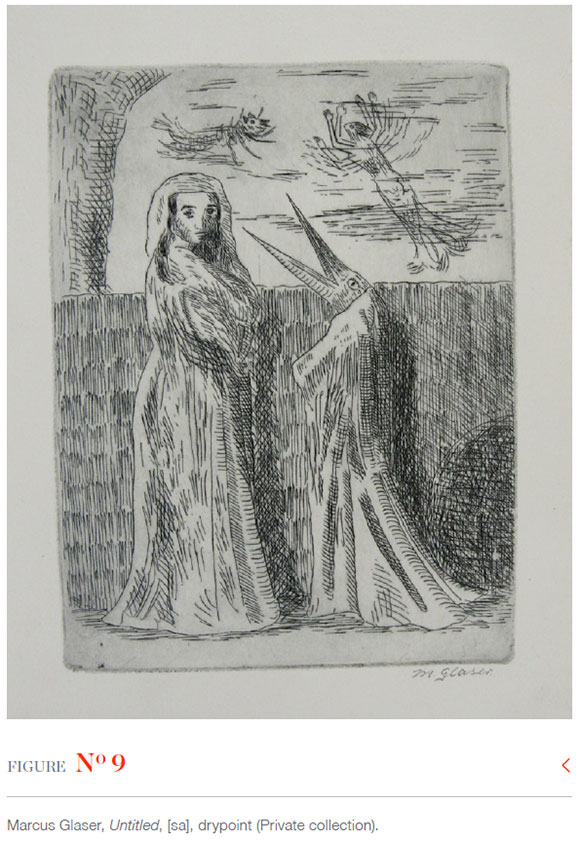

Glaser made a second Crucifixion print that seems to combine elements of the iconography of the Deposition with aspects of the Lamentation of Christ, and even the Transfiguration.20Since both are undated it is not possible to say which came first. I am tempted, however, given the rather more experimental and impressionist look of the aquatint, to place it as later than the etching. Here, Glaser abandons all pretence at classical representation and instead plays freely with perspective and compositional logic. The figures surrounding Christ now float off the ground and Glaser suggests their connection to the central figure not through any particularly emotional content but rather through the positioning of the heads, all of which are turned towards Christ, and the circle of arms around the latter's legs. The exaggerated halo in this image and the raised arms of Christ (the left hand showing the stigmata quite clearly) show Glaser making explicit reference to the medieval roots of the Deposition image. These overtly religious signals in his image are a display of his immersion in the history of western painting going back to thirteenth- and fourteenth-century oils, frescoes, mosaics and altarpieces.

Glaser's representation of the Deposition has less to do with the image itself than with its function as a synecdoche for the canon of western art. He paints two Crucifixions some time in the 1960s and then later prints at least two Depositions because he clearly has a sense of his own work in relation to that canon. His chosen artistic forebears are almost entirely European and if he is to have any place in the great panoply of western artists he has to insert himself into a very long European tradition in which the Passion plays a central role.

For Glaser and other artists, the Deposition represents, in the way of a Janus figure looking back and forward at the same time, a visual starting point for contemplation of what one inherits and what, then, to do with this inheritance. Glaser's image is a quotation of the Deposition in order to work out his relationship to the past, to the images he has looked at again and again. His gesture is to quote the formal and emotive aspects of the image as a contemplation of simultaneous belonging and separation.

REFERENCES

Alexander, FL. 1974. South African graphic art and its techniques. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

Baudrillard, J. 1994 [1981]. Simulacra and simulation. Translated by S Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Belling, V. 2013. Recovering the lives of South African Jewish women during the migration years, c. 1880-1939. PhD thesis. University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Berman, E. 1969. Art and artists of South Africa. Cape Town: Balkema. [ Links ]

Ernst, M. & Breton, A. 1981 [1929]. The hundred headless woman. New York: George Braziller.

Ernst, M. 1976 [1934]. Une semaine de bonté: a surrealistic novel in collage. New York: Dover Books.

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]. 1965? The flower of love. Self-published (play and illustrations).

Glaser. M. 1993. The unquiet love. Cape Town: Snailpress. [ Links ]

Glaser. M. 1996. Unmitigating circumstances. Cape Town: Firfield Press. [ Links ]

Glaser. M. 2001. The unquiet haven. Johannesburg: The Purloined Geranium Press. [ Links ]

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]a. A collection of verse and pictures. Self-published (poems and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]b. The dream of Rosita. Self-published, edition of 200 (play and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]c. The enchanted city. Self-published (poems and etchings).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]d. Les gens horribles. Self-published (play and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]e. Happy happy beautiful. Self-published (short story and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]f. The harbor. Self-published (poem and woodcuts).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]g. Impressions. Self-published (poems and etchings).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]h. Look at the sea, Harriet. Look at the sea. Self-published (with etchings).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]i. The mysterious city. Self-published (poems, collages and etchings).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]j. Notebook: pictures and semi-verse. Self-published (poems and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]k. Plays. Self-published (with etchings).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]l. Three plays. Self-published (with illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]m. Three stories. Self-published (with etchings).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]n. The unquiet love: the world of Marc Glaser. Self-published (poems, short stories and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]o. unpublished memoir.

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]p. untitled book. Self-published (plays, poems and short stories with illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]q. untitled book. Self-published (etchings, drawings and woodcuts with short story, play and poem).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]r. Verse. Self-published, edition of 80 (poems and illustrations).

Glaser. M. [ Links ] [Sa]s. Verse II. Self-published (poems and drawings).

Hobbs, P & Rankin, E. 1997. Printmaking in a transforming South Africa. Johannesburg: David Phillips. [ Links ]

Krüger, K, Schalhorn, A & Werner, EA (eds). 2015. Double vision: Albrecht Dürer/William Kentridge. Munich: Sieveking Verlag. [ Links ]

Law-Viljoen, B. 2016. The printmaker. Cape Town: Umuzi. [ Links ]

M iles, E. 1997. Land and lives: a story of early black artists. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. [ Links ]

Panofsky, E. 1955 [1945]. The life and art of Albrecht Dürer. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Parshall, P. 1993. Imago Contrafacta: images and facts in the Northern Renaissance. Art History 16:554-570. [ Links ]

Powell, AK. 2012. Depositions: scenes from the late medieval church and the modern museum. New York: Zone Books. [ Links ]

Strauss, WL (ed).1972. The complete engravings, etchings and drypoints of Albrecht Dürer. New York: Dover Books. [ Links ]

1 One outcome of this project was my novel The Printmaker (Law-Viljoen 2016). The protagonist, March Halberg, is based partly on Marcus Glaser.

2 Particularly tantalising are the Deposition prints, made in the same period as Glaser's, by the black South African artist Albert Adams (1929-2006), who, at the time he made these prints, was on the verge of leaving South Africa permanently for England. Here, once again, is the appearance, in the work of a classically trained South African artist, of this key image in the western canon. A full discussion Adams is material for another essay.

3 There is a larger thesis still to be written on the relationship of South African art to Renaissance printmaking particularly as exemplified by Dürer. A recent study of Dürer and William Kentridge is the start of such an undertaking. See Krüger et al.

4 See Amy Knight Powell (2012) for a full discussion of Deposition rites.

5 In New Testament theology, this 'emptied' body has undergone kenosis, a self-emptying set in motion by Christ's willingness to be sacrificed. The term is used in Philippians 2:7 and is often translated as 'made himself nothing'.

6 I should note that at the tail end of this list are a few images that might not count as traditional Depositions.

7 'I come from a line of twelve rabbis on my mother's side. I am related to the rabbi Feuchtwanger's 'Jew Süss' [Joseph Süss Oppenheimer]. My mother's brother's wife was Katie Gluckman, the head of the South African Women's Zionist Association. On my father's side I am related to Sir Solly Zuckerman, and to Harry Ravel, who composed music for Shirley Temple' (Glaser [sa]o:65).

8 Hilda Purwitsky and Roza van Gelderen were a well-known Jewish lesbian couple in Cape Town whose lifestyle and teaching philosophy were to have an important impact on the teaching of art in Cape Town schools. Van Gelderen taught the architect Denise Scott Brown in the 1940s, and the two women included in their circle Sarah Goldblatt, the executor of the poet CJ Langenhoven, and the artists Irma Stern and Wolf Kibel. After teaching art in Cape Town schools, van Gelderen opened a children's art studio on Breda Street in 1941, which came to be called The Yellow Windows Studio. She opened a second, similar institution in Johannesburg, which is where both Glaser and Scott Brown would have been taught (see Belling 2013).

9 Lipshitz took up a position at Michaelis in 1950 and remained there until the mid 1960s. In Cape Town, he was part of a group of artists that included Maurice van Essche, Cecil Higgs, Irma Stern, Maud Sumner and others.

10 (Glaser [sa]o:39).

11 In his memoir, Glaser credits himself with suggesting to Wolpe that he turn his famed framing shop into a gallery ([sa]o:51).

12 Glaser makes special mention in his memoir of his sketches of the French ballerina and actress Zizi Jeanmaire who appeared in a revue at The Empire Theatre on Commissioner Street in Johannesburg in 1964.

13 By the time I gained access to Glaser's substantial library, some of the books had already been sold, so while I can judge what might have been in the complete library from the tenor of what remained, I cannot be certain of everything he had collected.

14 The long relationship of Picasso and his publisher Ambroise Vollard is an example of this. In South Africa, the art dealer David Krut has published William Kentridge's prints since the 1990s. The role of the publisher has, to a large extent, now fallen away, with the printmaker or the studio acting in this capacity. The South African printmakers Malcolm Christian and Mark Atwood are examples of this newer category of printer-publishers.

15 Parshall (1993: 554-555) himself points out the complexity of such a discussion: The notion that in some way or another art served to reflect the natural world had the consequence of setting it in opposition to nature as something of distinctly human manufacture. What, then, was the proper role of the artist? The varied responses to this question constitute the substance of art theory from the Renaissance onward, a history that can hardly be summarized here. Suffice to say that during the sixteenth century the importance of artistic invention migrated to the center of critical debate, and in certain circles the classical model of mimesis came to be reformulated in such a way that for a time the operations of art and nature were paralleled to one another and their separate products esteemed on similar and equal terms.

16 Glaser goes on at some length about this incident in his memoir. The sculptor was Bruce Arnott who, said Glaser, plagiarised the etching of 'a man running with a walking stick, chasing someone'. The sculpture was installed in Joubert Park.

17 The pentagram is common to freemasonry, but there is no evidence to suggest any interest on Glaser's part in the occult or in esoteric wisdom (except perhaps in his practice of judo). Indeed, this apparent pentagram may also be read quite simply as a representation of a star.

18 Ivan Vladislavic has suggested to me the possibility that this nude might be an angel figure, and that there is a similar figure, although winged, in the top right corner of Chagall's Deposition (1941).

19 In Christian hagiography, there is a long tradition of the Scala coeli and the Scala paradisi (ladder to heaven), represented in works of art such as the twelfth-century icon by Johannes Climacus in the Monastery of St Catherine of Sinai in Egypt. Many painted Depositions and Crucifixions of the Renaissance make reference to this element of the Passion that conveys the idea of the connection to the divinity.

20 In representations of the Passion, this image is given either in place of the Deposition or following it in the visual narrative. In Dürer's series The Small Passion, the image is of the Deposition, but in his The Engraved Passion from the same period, the Deposition is replaced by the Lamentation of Christ, which shows the body of Christ already removed from the cross and surrounded by mourners.