Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.31 Pretoria 2018

Gazing upon the mother giving birth: anxieties and aliens in Ridley Scott's Prometheus (2012)

Samiksha Laltha

School of Arts, Pietermaritzburg Campus, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. samikshalaltha@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article explores the female hero and more significantly, the female alien - the Trilobite - in Ridley Scott's science fiction film, Prometheus (2012). The female alien reveals social, cultural and sexual anxieties that are projected onto the audience. Using a feminist film analysis, this article explores how horror in the science fiction film responds to gendered cultural shifts that disrupts the view that cinema is constructed for the viewing pleasure of a patriarchal society. Through a particular scene in the film, and through gazing at the mother alien giving birth, this article explores how cinema wields potential to disrupt the male gaze, and identify with female sexuality and the female body. Employing a feminist psychoanalytic framework, the article shows the film's potential to grapple with the issues of the female unconscious, revealing the female alien as a site of power through her procreative potential. The Alien franchise has garnered significant attention from feminist film theorists, focusing predominantly on the alien Xenomorph. This analysis instead focuses on the alien Trilobite, as the mother and progenitor of the Xenomorph.

Keywords: Alien; female gaze; science fiction film; castration; abjection.

Aliens are necessary because the human species is alone. The lack that creates them is an Other to whom we can compare ourselves. Many fundamental qualities of spirit/mind appear to exist only in us, so we have nothing to measure them with, to allow us to see our limits, our contours, our connections (Csicsery-Ronay 2007:5).

Introduction

This paper provides an analysis of the figure of the alien in Ridley Scott's Prometheus (Scott 2012) to reveal the social anxieties related to female biology, sexuality and reproduction, through the female alien, the Trilobite. Analysed through a feminist lens, the horror scene in Prometheus where the Trilobite procreates, functions to unsettle Laura Mulvey's (1975:804) contention that cinema is constructed as a site 'where men can live out his phantasies and obsessions'.

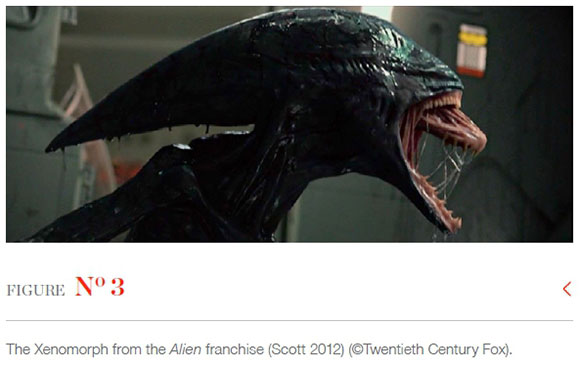

Prometheus1 functions as a prequel to the Alien franchise which places significance on the Xenomorph, the 'most famous hostile alien of all film' (Grech, Vasallo & Callus 2015:53). Both Ridley Scott and James Cameron have created a franchise revolving around the Xenomorph as an exemplary form of intelligent design and evolutionary perfection, so much so that it has become the alien that 'we've come to love' (Sobchack 2012:34). Its superior evolutionary biology is depicted through its acidic blood, pharyngeal jaws and predatory nature. While significant attention and discussion has been devoted to the Xenomorph, this study provides an analysis of the Trilobite, the mother of the alien Xenomorph species.

The film takes place in the year 2093 when a scientific vessel named Prometheus arrives at planet LV-223, in search of the progenitors of the human race: giant extra-terrestrial male beings, who are referred to as engineers. The research team is spearheaded by Dr Elizabeth Shaw. David, the android aboard the ship, curious about his creative potential, indirectly impregnates Shaw with an alien child. Shaw evicts the parasitic alien from her womb via surgery performed by a robotic capsule. She attempts to kill the face-hugger, without success. When David awakens an engineer from a sleep-pod, the engineer embarks on a killing-spree, setting his sights on Shaw. While attempting to escape his clutches she encounters the Trilobite, the monstrous-feminine, who has grown to gigantic proportions since its birth. Shaw successfully manages to push the engineer into the tentacle arms of the Trilobite to save herself. The sexual contact between Trilobite and the engineer gives rise to the Xenomorph.

Science fiction is often viewed as gendered territory, favouring the masculine (Booker & Thomas 2009:86). In an interview, Ridley Scott discusses the male engineers and their purpose in the narrative. He grapples with the creation of the universe and of humankind, conjuring up the fictional engineers as seeders of life. He asks, 'for us to be sitting here is actually mathematically impossible without a lot of assistance. Who assisted? Who made the right decisions?' (Schafer 2001).

Through representing the engineers as creators, Scott also provides an alternate theory of creation, albeit a fictional one. This stands in contrast to the popular notion of Darwinian evolutionary theory, as in the film, an alternate version of creation is offered. Scott builds his narrative around the theory of life that he proposes at the beginning of the narrative in a conscious effort to foreground the wider themes of creation that are evident in the film. This theory places an emphasis on science and creation as masculine domains, structured to attribute creative potential to the male, thereby, excluding the female. In contrast to this, the end of the narrative explores the creative potential of the Trilobite, foregrounded in the feminine. Scott also revamps the notion of male genesis by depicting the creative power of the female, over the male; using his body as a mere vessel of transportation for her offspring. Through the Trilobite, female creative and destructive capacity is foregrounded. Towards the end of the narrative the Trilobite defeats the engineer and uses his body to implant her offspring. The sexual union gives rise to the Xenomorph.

This act of creative power differs from the Christian patriarchal order of creation. The 'dominant pattern in human history ... gives greater power and privilege to males' (Martos & Hégy 1998:3). This is explicitly seen within Christianity through 'a divine "son" of a divine "Father"' (Reuther 1998:92). The physiology of the female alien sees her bringing forth life by impregnating a male body and using this vessel to give rise to her child. This counters the Christian depiction of the female body impregnated and being used as a vessel by a male God. This depiction of female creative power stands in contrast to women as represented by the 'bodily realm' to be 'ruled over by the male in systems 'of dominance and subjugation' (Reuther 1998:90).

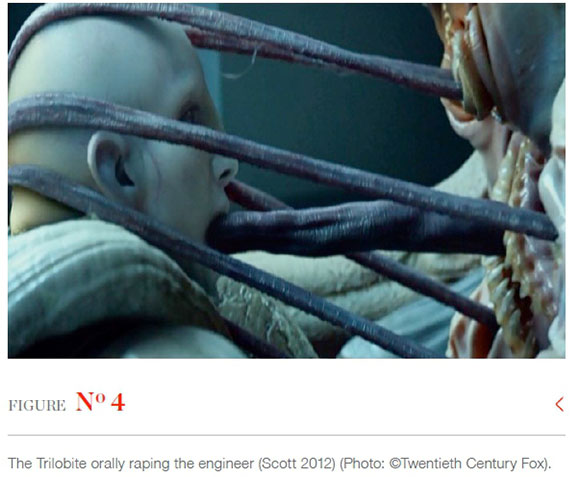

Cinema wields the potential to produce 'meanings about women and femininity' (Smelik 1998:9). In "reading against the grain", a feminist analysis centres on a 'strong sexual female' character, issues pertaining to women, or issues that 'explicitly address a female audience' (Smelik 1988:15). Using a feminist analysis, I discuss how the Trilobite and the procreation scene creates identification with the feminine by destabilising the male gaze through this particular scene in the film. In reading against the grain, I elaborate on how this scene refuses to fulfil the voyeuristic desires of a patriarchal culture, which places an emphasis on masculinity, through the oral rape and castration of the engineer.

Lynda K Bundtzen (1987) and Barbara Creed (1990) focus their feminist film analyses on the Xenomorph-queen in the Alien franchise. Using their commentary, I explore how the Trilobite is a far more explicit representation of the feminine, fecundity, sexuality and biology than the Xenomorph-queen because the Trilobite embodies a far more explicit sexual representation of the monstrous-feminine than the Xenomorph-queen.

To centre a discussion of the Trilobite as mother, I employ psychoanalytic theories advanced by Bracha Ettinger who, in also reading against the grain, highlights a feminist paradigm which stands in contrast to a Freudian and Lacanian emphasis on the phallus and the notion of lack. Representation is moved 'away from the dominance of patriarchal, Eurocentric and heterosexist normativization' (Rogoff 2002:26), and towards an exploration of the female, her sexuality and identity.

Laura Mulvey advances an argument for the construction of cinema in patriarchal society. In a follow-up to her 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' Mulvey (1975) explores films that have a female hero at their core. Prometheus represents creation by both male (engineer) and female (Trilobite) entities. While the film encapsulates a vision of male genesis through the engineers it also depicts creation by the powerful female figures, which are discussed through a feminist analysis centred on the female body, desire and psyche. These include the woman as 'sexually mature woman [and] as non-mother' (Mulvey 1975:804), represented through the female hero, Elizabeth Shaw, maternity outside the signification of the phallus' (Mulvey 1975:804), as seen through the Trilobite and her sexual reproduction, and 'the vagina' (Mulvey 1975:804), explicitly represented by the monstrous-mother. Through reading against the grain, using a feminist lens, multiple points offer an alternate view to the patriarchal order of creation.

The alien anxiety and the female hero

The presence of a female hero in Prometheus further establishes the narrative within a feminist framework. Feminist science fiction narratives deconstruct 'sex and gender' so that the 'modes of reproduction and parenting are re-envisioned compared to traditional forms' (Damarin 2004:57). Prometheus envisages the birth of the alien from a human mother, further disrupting the approach to reproduction and birth. Science fiction texts that feature a female protagonist provide 'sophisticated commentary on the gender issues that shape and inform our contemporary existence', making it an attractive 'medium for feminist concerns' (Booker & Thomas 2009:95). In her afterthoughts on 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' Mulvey (1999:122) puts forth a case for film instances that explore 'a female character occupying the centre of the narrative arena'. This alters the narrative discourse where woman does not equal sexuality but rather becomes a signifier of sexuality (Mulvey 1999:127).

Although Shaw experiences the 'unthinkable horror' (Bundtzen 1987:15): the 'impregnation with the alien other' (Csicsery-Ronay 2007:15), she escapes death and takes back her power and agency with the help of technology, accomplishing a feat that Ripley was unable to in the Alien franchise. In the Alien franchise, 'Labour and delivery are horrendous, unnatural expulsions of monsters that burst, screaming, from the writhing female' revealing that 'death is preferable to labour and birth' (Yunis & Ostrander 2003:20). In Prometheus, Shaw performs her own Caesarean section to evict the alien and save her life. The scene is difficult to watch as it creates discomfort through the pain experienced by the protagonist. As a laser sears through her flesh and mechanical, surgical arms remove the alien from her womb (see Figure 1). The blood and resultant discomfort may force the male viewer to look away from the woman who is 'signifier for the male other' (Mulvey 1975:804), thus inverting cinema's function to fixate and suture the gaze on the screen. The 'suturing processes are momentarily undone while the horrific image on the screen challenges the viewer to run the risk of continuing to look', so that the viewer, 'unable to stand the images of horror unfolding before his/her eye, is forced to look away, to not-look, to look anywhere but at the screen' (Creed 1990:137).

In the Alien franchise, 'woman's reproductive capacity is a potential threat', not just to herself, but also to 'civilization [and] technological progress' (Bundtzen 1987:16). However, in Prometheus the threat of the alien is temporarily overturned when Shaw uses technology to take back her agency from the alien within her. The film projects a preference for birth aided by technology, avoiding the gore and death that accompanies the natural process of birth, explicitly depicted through the 'chest-busters' in the Alien franchise. While painful, the surgery is quick and moderately clean. While Shaw does manage to save the human civilisation from the alien threat, the threat is not completely eradicated due to the fecundity of the Trilobite.

The Trilobite and the female gaze

The Trilobite in Prometheus takes its name from a creature that lived approximately 570 million years ago (Levi-Setti 1995:1), making them the oldest fossil arthropods (Levi-Setti 1995:3). The Trilobite possessed remarkable levels of 'functional complexity', displayed through accelerated biological evolution (Levi-Setti 1995:1). It is a befitting name for the mother-alien at the centre of Scott's narrative as she possesses the ability to grow to a grotesque size in a short period of time, reproduce with another alien species and bring forth a new species from the union, which also occurs in a short interval of time.

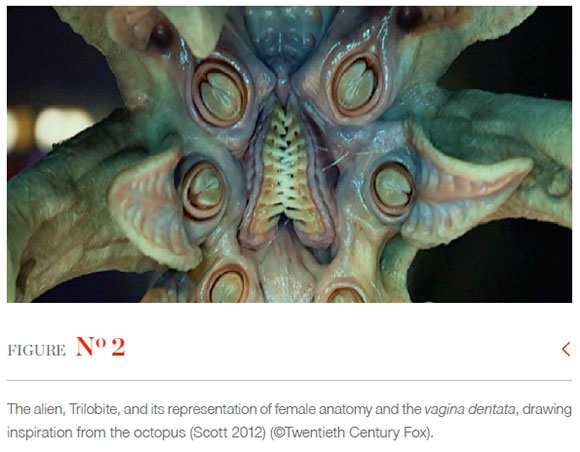

The form of the alien in the popular imaginary is influenced by animals and 'any animal form known to exist on Earth will eventually become an entry in SF's [science fiction's] xenomorphological catalogue' (Csicsery-Ronay 2007:13). The Trilobite bears resemblance to an octopus-like creature, with her many tentacle-arms (Figure 2). The octopus is a depiction of 'other-worldliness here on Earth' (Seth 2016:47). Aliens possess 'strange body shapes, unusual abilities and uncanny intelligence' just like the octopus, which is 'our very own terrestrial alien' (Seth 2016:47). The tentacles of this creature are central to the alien and the science fiction genres (Seth 2016:54), largely because, unlike humans who have their neurons concentrated in the central brain, the octopus has its half a billion neurons in 'its semi-autonomous arms which are like independent animals' (Seth 2016:47). In Prometheus, the Trilobite uses its many arms to draw the engineer into its vagina dentata where he is suffocated. Amia Srinivasan (2017) discusses the octopus and its ability to threaten boundaries. Like Seth, she also observes the octopus's likeness to an alien, observing that it is the closest encounter to alien life which humans can experience.

Srinivasan (2017) also makes reference to a piece of artwork from 1814, created by Hokusai which depicts a women sexually entwined with two octopi, while one performs oral-sex on the woman. This early image of art fuses female sexuality with the octopus. This art shows a 'mutual sexual desire' (Vargas 2011:3) between the octopus and the woman and it is not a rape scene as some have suggested. This wooden block print {shunga}2 celebrates 'female sexuality' as the woman is not in a state of distress (Stockins 2011:6). The octopus is depicted in a positive light, and the 'relationship between the woman and the octopus develops over time as a lover, companion, and a figure of protection' (Stockins 2011:138). As a Japanese cultural export to the west, the figure of the octopus has been perverted, illustratively, culturally and socially, through graphic depictions of tentacle pornography appropriated from hentai.3 Ridley Scott adapts the image of the octopus to represent the powerful female alien at the centre of his narrative.

Like the Xenomorph-queen in Aliens (1986), the Trilobite possesses both male and female organs; however, she is not androgynous. Her vagina dentata is far more explicit than her phallic arms and this 'is confirmed by' the 'graphic display of female anatomy', her 'vulva and labia' (Bundtzen 1987:12), which reside inside her cavity. Csicsery-Ronay (2007:9) observes how '[t]he alien cannot be completely different because it is different in significant ways. The alien is fated to signify. It must have a mind, because if it does not, neither do we'. The Trilobite's sexual organs are far more explicit than those of the Xenomorph-queen's as they are much larger. The exaggeration of female sexual organs depicts a paradigm shift in contemporary Hollywood science fiction film as there is a lack of 'skilled and satisfying manipulation of visual pleasure' (Mulvey 1975:805). This lies in contrast to woman as the prime object of the voyeur, denying the pleasure of scopophilia.4 The image of the Trilobite works instead to create discomfort in place of pleasure. The 'voyeuristic phantasy' (Mulvey 1975:806) is shattered, and the 'fascination with likeness and recognition' of human face and body (Mulvey 1975:807) is replaced by horror and discomfort.

In a similar fashion to the Xenomorph-queen, the Trilobite depicts 'female fecundity' which is 'prolific and devouring' (Bundzen 1987:11). She is 'juicy femaleness, nature gone wild, not technology gone awry' (Bundzen 1987:15). Her biological drive and fecundity are emphasised through her attempt at killing her mother, Shaw. Comparable to the Xenomorph she embodies 'woman's reproductive powers' (Bundzen 1987:14). Her orifice on her underside harbours tendrils which are used to implant a host species into the engineer. This orifice bears explicit resemblance to the vagina dentata which is modelled on the primordial image of the 'vagina-with-teeth' (Raitt 1980:415). Although the image of the vagina dentata is rooted in mythology (Raitt 1980:416), it became popularised in twentieth-century culture where it embodied male fears of the female anatomy (Raitt 1980:416) and the threat of castration. The terror embodied by the Trilobite evokes anxieties for a male audience as the threat of castration is imminent. The Trilobite is similar to the aliens that Csicsery-Ronay (2007:3) describes, in that she is driven by herself and she exists for herself.

The earlier reference to the Trilobite and the species of cephalopoda invokes Sigmund Freud's (1993:23) mythological notion of the 'phallic mother'; the 'horror of the female genitals' and its psychoanalytical association to the arachnid. Freud draws a distinction between the mother and the spider, making reference to and stemming from the mythological Medusa, having snakes in place of hair (Freud 1993:23). Like the octopus, the spider also has eight limbs extending from its body. Freud links this horrifying mythological image of the spider to the fear of castration (Freud 1993:23). Maureen Murdock (1990:18) also uses the image of the gorgon to describe what she refers to as the 'Terrible Mother' who represents 'stasis, suffocation and death'. She is both 'womb and tomb', and in as much as she is able to give life she also takes it away (Murdock 1990:20). The Trilobite, like the Xenomorph-queen, arouses 'primal anxieties about women's sexual organs' as she emerges as the 'phallic mother of nightmare' (Bundtzen 1987:14).

Laura Mulvey has unravelled the ways 'in which narrative and filmic techniques in cinema make voyeurism an exclusively male prerogative' (Smelik 1998:10). According to Laura Mulvey (1975:808), the gaze in cinema is split between 'active/male' and 'passive/female', where the 'male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female figure'. Through the impregnation scene involving the Trilobite and the engineer, Prometheus challenges this dichotomy through the phallic mother and her 'monstrous vagina' (Creed 1990:135). Confrontation with the phallic mother causes the male viewer to look away. Not only does the horror of the Trilobite and her explicit vagina dentata unravel the suturing processes, the Trilobite also performs a double castration on the engineer, first by raping him orally with her tendrils, and then by suffocating him with her monstrous vagina dentata. The engineer's dead body becomes the vessel for her offspring: the horror that is the Xenomorph (see Figure 3).

Shaw and her contaminated husband produce the Trilobite, and the Trilobite and the engineer produce a Xenomorph. The 'representations of alien sex confront the problem of the unrepresentability of a nonoedipal desire' (Rogan 2004:443), as it 'exists outside lack and appropriation' (Rogan 2004:444). The Trilobite and her fecundity are representative of procreative potential and power. Her offspring lives within her womb and only requires the engineer as a vessel for its gestation. Bracha L Ettinger (2006:218), using a psychoanalytic framework, discusses the notion of the 'matrixial stratum of subjectivization', which places signification on the 'womb' as opposed to the 'weight of the phallus' (Ettinger 1997:426), proposed by both Jacques Lacan and Sigmund Freud. For Freud the 'Western symbolic order derives its coherence from the phallus or paternal signifier', creating a dialogue centred on 'phallocentricity' (Silverman 1983:131). For Lacan, the phallus 'designates the privileges of the symbolic', where the word 'lack' denotes the absence of the penis in females (Silverman 1983:139), denying them access to the power and privileges afforded by the phallus. As an alternative to this discourse, Ettinger (2001:103) designates that the womb functions as a 'complex psychic apparatus modelled upon this site of feminine/prenatal encounter'. Her argument places an emphasis on 'connections with female bodily specificity' (Ettinger 1997:427), where the matrixial gaze 'rolls into several eyes, transforms the viewer's point of vision and returns through his/her eyes to the Other of culture, transformed' (Ettinger 2001:111).

The Trilobite places an emphasis on the signification of the feminine, the vagina and the womb, and this shifts the gaze from serving the pleasures of the male to addressing issues of femininity and female power. The Trilobite is representative of the 'the body of the mother' as 'other' (Ettinger 2001:89). Patriarchal culture constructs the womb as 'abject' (Ettinger 2001:76). Ettinger (2004:69) refers to the importance of the archaic mother. She explores the potential of the womb for 'female development' by placing 'value on the subject' (Ettinger 2004:70). The 'matrixial womb stands for a psychic capacity for shareability created in the border linking to a female body' (Ettinger 2004:76). The womb thus has the capacity to become a 'major signifier' (Ettinger 2004:79).

The castration anxiety is a central concern of the horror film (Creed 1999:256). Discussing Creed, Shohini Chaudhuri (2006:100) observes that woman in film can be representative of the woman as castrator or the femme castratrice. The Trilobite can be described as the 'castrating mother' and the 'real source of horror' (Chaudhuri 2006:100). The femme castratrice is 'an all-powerful, all-destructive figure' who awakens both the fear of castration and the fear of death in men (Chaudhuri 2006:101). In films that feature the femme castratrice 'it is the male body, not the female body that bears the burden of castration' and the 'spectator is invited to identity with the avenging female castrator' (Chaudhuri 2006:101). The female audience of Prometheus is thus called to identify with the Trilobite and her power to procreate from the castration enacted on the body of the male engineer.

The scene where the Xenomorph is born is a depiction of what Julia Kristeva (1982) refers to as abjection. The female alien Trilobite and its excessiveness evoke what Kristeva describes as 'abjection', the place 'where meaning collapses' (Kristeva 1982:2). Abjection occurs when identity systems and order are disrupted (Kristeva 1982:4). The abject does not respect 'borders, positions, [or] rules' (Kristeva 1982:4). Kristeva observes, 'the abject is perverse because is neither gives up nor assumes a prohibition', it 'kills in the name of life' (Kristeva 1982:15). The Trilobite exists for the sole purpose of reproduction. Her phallic arms are in constant search for a vessel in which she can implant her offspring for gestation.

In an analysis of abjection within the Alien franchise, Creed (1999:252) explores whether the genre of horror can cause the male spectator to embody the abject, causing alterations in one's physical state when confronted with the monstrous-feminine (Creed 1999:252). The amniotic fluid seen in a representation of the primal scene when the Xenomorph emerges from the dead body of the engineer 'signifies a desire [...] to throw up, throw out, eject the abject (from the safety of the spectator's seat)' (Creed 1999:253). Abjection fills the spectator with 'disgust and loathing' while simultaneously pointing 'back to a time when a "fusion between mother and nature" existed; when bodily wastes, while set apart from the body, were not seen as objects of embarrassment and shame' (Creed 1999:256).

Susan Hayward (2013:143), employing a psychoanalytic angle on feminist film theory observes how, often in film, the Elektra complex5 for the female is confirmed even when the phallic mother is present, as the female hero kills the mother and marries the father. Prometheus works to unsettle this contention as Shaw does not successfully kill the phallic mother, and she does not unite with the symbolic father; in fact, the film establishes that Shaw lost her father at a young age and she is also tragically widowed when her husband comes into contact with alien DNA. The agency that she achieves through escaping the phallic mother, killing the engineer and saving the entire human race establishes her as a powerful female figure, who does not require a union with a male counterpart. Shaw's state of maturity is achieved before her encounter with the phallic mother, as is visible through her success as an academic and a professional.

Making use of a feminist analysis of Prometheus, the female viewer of the film is given the opportunity to employ a resistant view which refutes the prevailing male gaze. Zoe Dirse (2013:27) discusses the multi-layered nature of the female gaze where the bearer of the look is female and the subject is female, creating a situation where the subject subverts the gaze and gazes at herself. The Trilobite and its graphic display of female sexual organs creates a situation where the female viewer confronts her own femininity in and through the female sexual organs of the Trilobite.

Mulvey (1975:809) cites the function of woman in cinema as being expected to hold the look of the audience, play to, and signify male desire. The images of the female entities in Prometheus have the opposite effect, forcing the male viewer to confront a metaphorical castration through the physical oral rape and symbolic castration occurring on the screen. In James Cameron's Aliens (1986) the viewers were not permitted a proper look at the Xenomorph-queen. Employing a similar tactic, the viewers of the Trilobite are not permitted a thorough look at the alien-mother. This, in addition to the intentional lack of proper lighting in the scene, functions to amplify the anxiety and discomfort for the audience. Not only is the audience denied a proper viewing, the audience may look away from the discomfort created by explicit sexual nature of the Trilobite's orifice.

For Mulvey (1975:810), the woman in Hollywood cinema and her 'lack' of a penis implies a 'threat of castration and unpleasure' for the male audience. The Trilobite has both phallic arms and a vagina dentata, signifying simultaneously the fear of rape and castration. Considering that the engineer (as a male) is her first victim and that his capture is brought about by her multiple tendrils and oral rape, the scene evokes increasing anxieties of castration and rape for the male audience (figure 4). The 'voyeuristic or fetishistic mechanisms' (Mulvey 1975:815) are removed, making the threat of castration unavoidable. Within Cameron's film the terror evoked by the Xenomorph-queen is 'grounded in archetypal fears of woman's otherness, her alien body and its natural functions' (Bundtzen 1987:16). The Trilobite amplifies this anxiety further through its explicit and graphic display of female sexual organs.

Prometheus, its female hero and the scene that depicts the fecundity of the Trilobite directly address issues pertaining to the female body and sexuality. During the course of the narrative the audience learns that Shaw is infertile. She therefore fulfils the role of the 'mature woman as non-mother' (Mulvey 1975:804), and this is further emphasised when she attempts to murder her alien child on two separate occasions. Following Mulvey (1975:804), 'maternity outside the signification of the phallus' is necessary to disrupt the male gaze in cinema. The Trilobite as the mother-alien becomes representative of Shaw's desire to be a mother. Her desire to be a mother turns into a nightmare when she becomes pregnant with the alien. Csicsery-Ronay (2007:3) notes that the alien 'may be what we oppress and repress', and '[t]hey may arrive only to draw attention to our incompleteness, or they may represent our other halves, our heart's desire'. Shaw's maternity occurs 'outside the signification of the phallus' (Mulvey 1975:804). Her husband is killed shortly after she is impregnated, and she alone performs the Caesarean section. The absence of the "father" and the alien child's ability to grow rapidly shifts the attention from the phallus, as a signifier of power, to the alien-child and its mother. Sex with the alien is representative of 'a female sexuality that does not depend on its relation to or alienation from the phallus' (Rogan 2004:446).

Both Shaw and the Trilobite compete for power and their respective survival, with neither reigning victorious over the other. The female entities (human and alien) in Prometheus create a paradigm shift that removes an emphasis on the female as 'iconic (image)' and places significance on the female as 'diegetic (storyteller)' (Dirse 2013:18). In addition to the absence of males in Shaw's birthing scene, the Trilobite as a representation of femininity results in castration for the engineer. Shaw also pushes the male engineer into the Trilobite's clutches creating a scenario where the feminine is far more powerful than the masculine. The punishment seems befitting in the face of the engineer's overwhelming hubris. The engineer becomes the sacrifice offered by Shaw to the mother-alien; and used by the mother-alien for her offspring. These instances of female power favour a female gaze by placing significance on the female and femininity as sentient and active principles.

More explicitly than the Xenomorph-queen, the Trilobite evokes the 'mythological narratives of the generative, parthenogenetic mother - that ancient archaic figure who gives birth to all living things. She exists in the mythology of all human cultures as the mother-goddess who alone created the heaven and earth' (Creed 1990:131). Since Prometheus is the prequel to the Alien franchise, the Trilobite is the more powerful mother of the Xenomoprh-queen. The Trilobite and her act of procreation result in the live birth of her offspring, unlike the Xenomorph-queen who exists within a hive-system. Her claim to power to brought about by her numerous offspring. The Trilobite, on the other hand, exists to create just one perfect creature. This is reiterated through the notion that in each successive film of the Alien franchise, the Xenomorph displays evolved features when comparing it to earlier models of the creature. The Trilobite projects a female desire to create and nurture, through reproduction. The generative mother also represents the qualities of the mysterious feminine symbol who is 'cavernous, unpredictable, dangerous', and simultaneously 'life-bearing and death-dealing' (Raitt 1980:419). The desire to reproduce is also reflected by the female hero, who is infertile.

The notion of the ancient creator with generative potential is a theme that features within the film through the creative potential of the engineers. In contrast to the male engineers as creators, the female Trilobite also wields the potential to create and destroy. The female desire to create life is one that is not fully understood by males as reflected through Shaw's husband, Dr Holloway, who makes an insensitive remark about creation being effortless. Like Shaw, the Trilobite also expresses a desire to reproduce, and in doing so, she displays her creative potential, linking this with the mythological narrative of creation and destruction. In order for the Trilobite to reproduce, the engineer must die. The mother-alien represents autonomous thinking and she is driven by her need to procreate.

The Trilobite, analysed through a feminist framework, is representative of the phallic mother and her threat of castration. She is a reminder of 'the Alien other in our own nature' (Bundtzen 1987:16). She also represents 'the limitations of our bodies, our creatureliness, our biological functions' (Bundtzen 1987:17). The realm of science fiction literature is 'misogynistic' (Booker & Thomas 2009:86). The feminine alien Other in science fiction film functions to threaten 'male dominance' (Booker & Thomas 2009:86). Contributing to a counter-discourse, the feminine alien other is '[i]mbued with the ominous power that many male writer bestowed upon her' and she has thus become a 'tool designed to disrupt the sexual hierarchy and challenge the construction of "woman"' (Booker & Thomas 2009:86).

This discussion has engaged with the figure of the female alien - the Trilobite - in Ridley Scott's Prometheus, to reveal the anxieties associated with this entity, grounded in a feminist analysis of science fiction film. The Trilobite represents the anxieties of sexuality, biology, the feminine and castration. The presence of a female hero and a female alien shift a psychoanalytical paradigm from the phallus to the matrix, activating a female gaze in and through Prometheus. As Mulvey has discussed, cinema constructs the ways in which women are viewed. Through a feminist film analysis, the Trilobite's procreation with the engineer unsettles woman as the object of the voyeur, while simultaneously depicting a castration anxiety through oral rape and her vagina dentata.

The vagina-with-teeth also 'visualizes, for males, the fear of entry into the unknown, of the dark dangers that must be controlled in the ambivalent mystery that is woman' (Raitt 1980:416). The failure to achieve this control is reflected through the Trilobite's successful reproduction of the Xenomorph. Scott's narrative charts a journey into the unknown universe, in addition to traversing the depths of an alien planet which houses a malicious, fertile, prolific alien-mother with an insatiable desire to create.

Acknowledgements

This article arises from research supervised by Professor Cheryl Stobie as part of the author's doctoral thesis on the Pietermaritzburg campus of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

REFERENCES

Berry, P. 2004. Rethinking 'Shunga': the interpretation of sexual imagery of the Edo Period. Archives of Asian Art 54:7-22. [ Links ]

Booker, MK & Thomas, A. 2009. The science fiction handbook. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [ Links ]

Britt, R. 2012. Ridley Scott explains Prometheus, is lovably insane. [ Links ] [O]. Available at: https://www.tor.com/2012/10/10/ridley-scott-explains-prometheus-is-lovably-insane/ Accessed: 30 August 2017.

Bundtzen, LK. 1987. Monstrous mothers: Medusa, Grendel, and now Alien. Film Quarterly 40(3):11-17. [ Links ]

Cameron, J. (dir). 1986. Aliens. [ Links ] [Film]: 20th Century Fox.

Cohen, J & Stewart, I. 2004. What does a Martian look like? The science of extraterrestrial life. London: Ebury Press. [ Links ]

Creed, B. 1990. Alien and the monstrous feminine, in Alien zone: cultural theory and contemporary science fiction cinema, edited by A Kuhn. New York: Verso:128-141. [ Links ]

Creed, B. 1999. Horror and the monstrous feminine: an imaginary abjection, in Feminist film theory: A reader, edited by S Thornham. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press:251-265. [ Links ]

Csicsery-Ronay Jr, I. 2007. Some things we know about aliens. Modern Humanities Research Association 37(2):1-23. [ Links ]

Damarin, S. 2004. Feminist sci-fi and post-millennial curriculum. Counterpoints 158:51-73. [ Links ]

Dirse, Z. 2013. Gender and cinematography: Female gaze (eye) behind the camera. Journal of Research in Gender Studies 3(1):15-29. [ Links ]

Ettinger, BL. 1997. Reply to commentary. Psychoanalytical Dialogues 7(3):423-429. [ Links ]

Ettinger, BL. 2001. Wit(h)nessing trauma and the Matrixial gaze: from phantasm to trauma, from phallic structure to Matrixial sphere. Parallax 7(4):89-114. [ Links ]

Ettinger, BL. 2004. Weaving a woman artist with-in the matrixial encounter-event. Theory, Culture and Society 21(1):69-93. [ Links ]

Ettinger, BL. 2006. Matrixial Trans-subjectivity. Theory, Culture and Society 22(2-3):218-222. [ Links ]

Fincher, D. (dir). 1992. Alien 3. [ Links ] [Film]: 20th Century Fox.

Freud, S. 1933. New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. Volume XXII (1932-1936):1-182. [ Links ]

Grech, V, Vassallo, C & Callus, I. 2015. The deliberate infliction of infertility in science fiction film. World Future Review 7(1):48-60. [ Links ]

Hallberstadt-Freud, HC. 1998. Electra Versus Oedipus: femininity reconsidered. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 79(1):41. [ Links ]

Hayward, S. 2013. Cinema studies: the key concepts. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kristeva, J. 1982. Powers of horror: an essay on abjection. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Levi-Setti, R. 1995. Trilobites. London: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Martos, J & Hégy, P. 1998. Equal at the creation: sexism, society and Christian thought. London: University of Toronto. [ Links ]

Mulvey, L. 1975. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema, in Film theory and criticism: introductory readings, edited by L Braudy and M Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press: 803-817. [ Links ]

Mulvey, L. 1999. Afterthoughts on 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema' Inspired by King Vidor's Duel in the Sun, in Feminist film theory: a reader, edited by S Thornham. Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh:122-129. [ Links ]

Murdock, M. 1990. The heroine's journey: women's quest for wholeness. Colorado: Shambhala. [ Links ]

Raitt, J. 1980. The "Vagina Dentata" and the "Immaculatus Uterus Divini Fontis". Journal of the American Academy of Religion 48(3):415-431. [ Links ]

Reuther, RR. 1998. Introducing redemption in Christian feminism. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Roberts, A. 2000. Science fiction. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Rogan, AMD. 2004. Alien sex acts in feminist science fiction: heuristic models for thinking a feminist future of desire. Modern Language Association 119(3):442-456. [ Links ]

Rogoff. I. 1998. Studying visual culture, in The Visual Culture Reader, edited by N Mirzoeff. London: Routledge:24-36. [ Links ]

Schaefer, S. 2011. Ridley Scott Talks 'Prometheus' Philosophy, Space Jockey, and 'Alien'. Screenrant. [ Links ] [O]. Available at: http://screenrant.com/ridley-scott-prometheus-space-jockey/ Accessed: 27 February 2017.

Scott, R. (dir). 1979. Alien. [ Links ] [Film]: 20th Century Fox.

Scott, R. (dir). 2012. Prometheus. [ Links ] [Film]: 20th Century Fox.

Seth, A. 2016. Aliens on earth: What octopus minds can tell us about alien consciousness, in Aliens: science asks: is there anyone out there?, edited by J Al Khalili. London: Profile Books:47-54. [ Links ]

Shelton, R. 1993. The utopian film genre: putting shadows on the silver screen. Utopian Studies 4(2):18-25. [ Links ]

Silverman, K. 1983. The subjects of semiotics. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Smelik, A. 1998. And the mirror cracked: feminist cinema and film theory. New York: Palgrave. [ Links ]

Sobchack, V. 2012. Between a rock and a hard place: How Ridley Scott's Prometheus deals with impossible expectations and mythological baggage. Filmcomment:30-34. [ Links ]

Srinivasan, A. 2017. The Sucker, The Sucker! London Review of Books. [ Links ] [O]. Available: https://www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n17/amia-srinivasan/the-sucker-the-sucker7utm_source=LRB+themed+email&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=20171021+themed&utm_content=ukrw_nonsubs Accessed: 1 November 2017.

Stockins, JM. 2009. The popular image of Japanese femininity inside the anime and manga cultures of Japan and Sydney. Master's Thesis. University of Wollongong. [ Links ]

Vargas, R. 2011. In loving memory of the pearl diver. University of Jyväskylä [ Links ].

Yunis, S & Ostrander, T. 2003. Tales your mother never told you: "Aliens" and the horrors of motherhood. Journal of the Fantastic Arts 14(1):68-76. [ Links ]

1 The Alien franchise consists of four Alms that chart the female hero's encounter and battle with extraterrestrial lifeforms. These films include Alien (Scott 1979), Aliens (Cameron 1986), Alien 3 (Fincher 1992) and Alien: Resurrection (Jeunet 1997).

2 Shunga literally translates to 'spring pictures' (Berry 2004:7). This Japanese word refers to erotic art that is painted or printed onto wooden blocks.

3 Hentai refers to erotic images and pornography in manga (comics in the Japanese language) and anime (hand drawn or computer generated images originating in Japan); both are sub-genres of Hentai.

4 The 'pleasure in using another person as an object of sexual stimulation through sight' (Mulvey 1975:808).

5 In psychoanalysis, the Elektra complex, proposed by Carl Jung, stands in contrast to the Freudian concept of the Oedipus complex where the girl-child has to grapple with the obsession with her father and the hatred of her mother. This 'paradigm for female development' is particularly interesting for feminist concerns as it 'grants central place to the mother-daughter relationship' (Hallberstadt-Freud 1998:41).