Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Image & Text

On-line version ISSN 2617-3255

Print version ISSN 1021-1497

IT n.31 Pretoria 2018

Soul searching: finding space for the soul in the New Digital Age

Karli Brittz

Part-time lecturer and PhD candidate, Department of Visual Arts, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. karli.brittz@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Within the context of the New Digital Age, is there still space to explore the phenomenon of the soul? The soul is often omitted in the philosophical discourse of technology and its impact on being human, owing to the (mis)conceptualisation of the soul as an outdated, western notion that is no longer applicable or significant in contemporary society and global culture. Throughout this article, I counter this argument by showing that an exploration of the soul in a technologically-driven society remains significant, since it reveals pivotal aspects of being human in contemporary society that could not have been highlighted otherwise. I maintain that the soul deserves consideration within the New Digital Age, since it allows us to think about being human in relation to technology in a unique manner, uncovering promising ideas as well as critical forewarnings. I also show that the soul is a culturally universal notion that enables a global discussion. By exploring visual culture examples (namely her, artworks by Aleksandra Mir and Wit) that represent various perspectives on the soul within a technological society, I contend that visual culture opens up a space for discussion on the soul in the New Digital Age.

Keywords: technology; soul; New Digital Age; visual culture; monism; dualism.

Introduction

Within the context of the New Digital Age,1 where life has become centered on technological development and the ontology of being human has entwined with technology, is there still space to explore the phenomenon of the soul? The canon of literature on being in the New Digital Age shows technology interceding with various properties of personhood such as self-concepts, the mind, relationships and consciousness (for example see Turkle 2005; Haraway 1990; Schroeder 1994; Kurzweil 1999; Kelly 2010). However, a specific property of personhood, the notion of the soul, is notably often neglected from these discussions on technology and being. A reason for this omission could be that it is widely believed that the soul is an outdated concept, owing to its religious conceptualisation that does not always seem to fit in with the postmodern thinking about technology. Moreover, the soul and so-called "western technology" is mostly considered to be a phenomenon specific to traditional western discourse, which creates the impression that a discussion on the soul and these technologies is not necessarily relevant to global or non-western culture. In particular then, exploring the soul - no matter the subject or point of view - is quite a controversial and complicated task. Throughout this article, I argue that, despite its difficulties, an exploration of the soul in a technologically-driven society remains significant, since it reveals pivotal aspects of being human in contemporary society that could not have been highlighted otherwise. The soul allows us to think about our being in relation to technology in a unique manner, uncovering promising ideas as well as critical forewarnings. Thus, the soul deserves consideration within the New Digital Age, or to put it another way, it is still necessary to do some soul searching in our technological surroundings.

In order to show how the soul remains a relevant and meaningful phenomenon, I examine visual culture examples that portray technology in relation to the soul. In the context of the twenty-first century the visual realm and image dominates the cultural field (Mirzoeff 1998). The visual contributes significantly to how people construct their understanding of the world, as well as how they come to define themselves (Freedman 2003). As a result, visual culture not only represents, but also informs or influences the self and impacts its identities. Perhaps foreshadowing the pertinent importance of the soul in the New Digital Age, a wide variety of visual culture (including films, television series, photographs and artworks) exploring the relationship between these two entities have recently emerged. For example, films such as Gravity (2013), Transcendence (2014) and Never Let Me Go (2010), television series like WestWorld (2016-), Altered Carbon (2018) and Black Mirror (2011-), as well as artists including Daniel Rozin, Brendan Fitzpatrick and Jeremy Shaw, all depict technological and soul-filled (notably also soulful) content. These visual examples allow the viewer to form meaning and contemplate philosophical thought considering the soul in a technological society. The realm of technology and the notion of the soul are thus both in constant dialogue through the image. Therefore, it is not only appropriate, but also inevitable that an investigation of the relevance of the soul in terms of technology ensues by referring to the manner in which these entities are embodied in contemporary visual culture. Hence, this article considers the capacity of the soul in the New Digital Age as it is represented in contemporary visual culture. By specifically examining the film her (Jonze 2013), artworks by Aleksandra Mir as well as the television film Wit (Nichols 2001), I aim to show that these visual examples firstly portray a space for the soul in the digital realm and, secondly, share ideas regarding the soul that are important for our thinking about being human in the New Digital Age.

A sensitive soul

Before discussing the relevance of the soul as it is depicted in visual culture, it is perhaps helpful to first explain what exactly is understood by the phenomenon of the soul in the New Digital Age. An enquiry into the notion of the soul is an ancient, somewhat contested, philosophical question that incorporates various fields such as science, theology and psychology. The idea of the soul connotes different interpretations, depending on individual beliefs, cultures, religions, societies and disciplines (Murphy 1998:1). Moreover, an individual's formation of the concept of the soul is usually based on specific exemplary experiences and practices developed in different traditions (Mcghee 1996:206). Proving (or disproving) the actual existence of the soul has been the concern of both religious institutions and scientific practices for millennia. Nevertheless, the concept remains 'elusive' (Goldblatt 2011) and difficult to validate, but is simultaneously difficult to deny. In a scientifically and technologically enhanced society a discussion of the soul is often associated with skepticism and disbelief, as empirical evidence cannot be found for such an immaterial principle (Casey 2013:32). Consequently, it is a discussion evaded by many in light of the technological sphere. Yet in contemporary society people are becoming continuously more interested in the notion of the soul as they 'are dissatisfied with the "soulless" existence of modern culture ... the thought of the soul offers just what they are longing for: depth, anchored lives, a spiritual and moral compass' (Casey 2013:32). In other words, for some, the idea of the soul presents a relief of sorts from present-day difficulties; therefore, it is a concept gaining interest once more. This increased curiosity towards the soul starts to open up its space in contemporary society.

Although it is a common belief that the soul stems from western practices, owing to its well-known philosophical roots in Platonic and Aristotelian thought as well as its ties to Christian and Catholic religions, the soul is in actual fact a concept used widely across the globe. Anthropologist George Murdock (1945) infamously named soul concepts a 'cultural universal' conviction, based on its commonality to all global human cultures - a viewpoint that remains widely accepted in current times. For instance, African cultures have embraced and expressed the soul in terms of a connectedness and spiritualism for centuries.2 At the same time, Eastern cultures (including Chinese and Japanese cultures as well as Buddhist traditions) believe in the soul as a guardian spirit, state of being and the essence of life, amongst other things.3 Amongst these cultures, the interpretations of the soul however differ and manifests in various ways. Despite this variation in interpretation, the universality of the concept emphasises the global value of finding a space to discuss the soul within contemporary society.

Arguably, three of the most prominent global interpretations on the soul include monism, dualism and physicalism (Gray 2010; Crane 2000; Deane-Drummond 2009).4 These three perspectives can be considered as amongst the most dominant ways of considering the soul and being in contemporary society. Similarly, visual examples depicting the soul in the technological sphere also tend to represent aspects of these three worldviews. A monistic outlook argues that reality is one single substance and that 'human beings are ensouled bodies' who are living, breathing, holistic persons (Gray 2010:638). Subsequently, animistic cultures can be seen as a specific example of monism (Gray 2010:644), because animists view most of reality as one holistic unity, while arguing that the soul cannot be separated from the body. Animism is one of anthropology's earliest and fundamental concepts (Bird-David 1999:67) and relates to cultures and religions from both the east and west. In its simplest form, animism holds the belief that inside of all objects there is an invisible being classified as the soul. Animism can therefore become a prominent perspective in the New Digital Age, as some consider technology to be ensouled with a similar essence as human beings. This is illustrated by examining the film her (2013).

In contrast to monism, a dualistic outlook on being considers the body '... as a shell and the soul escaping at death to be with God' (Gray 2010:643). In the philosophy of the mind,5 dualism is the view that human beings are made up of two substances: physical substance in the form of the body and non-physical substance in the form of the soul, the mind or consciousness. In addition, dualism can also refer to moral dualism, which is the belief in the great complement or conflict between the good and the evil or then the opposition between the virtuous and the malicious. Dualistic thought usually occurs within western society's religious or spiritual quest of existence, such as Christianity or Gnosticism. In modern society, Gnosticism is a framework focusing on religious teachings that embraces myths and mysteries of creation. A gnostic outlook believes in a transcending, righteous God, as well as an evil cosmos, denying the material world and endorsing the spiritual realm (Hurtado 2005:519). Gnostics think of the soul as the embodiment of the transcending God on earth (Hoeller 2012). Gnosticism, arguably, also closely relates to the New Digital Age and cyberculture, since there are 'gnostic motives in technology euphoria' (Krueger 2005:81-82). Virtual existence can be considered as the gnostic element of life in the digital realm, also referred to as 'cybergnosis' (Krueger 2005:86). In turn, a tendency towards posthumanism and transhumanism, as a manner of achieving transcendence from the immanent biological body and the evil world, can also be viewed as a form of cybergnosis in contemporary society, as depicted in various artworks by Aleksandra Mir.

Both monism and dualism stand in opposition to the third category that emerges as a common perspective on being in contemporary society: physicalism (also known as materialism). Simply defined, physicalism is a growing universal trend that explains the world according to science and physics. This perspective reduces everything in existence to atoms, molecules and physical bodies. Physicalism is associated with rationality and empirical evidence, arguing that the world should be interpreted in the most manageable physical terms (Gray 2010:642). Accordingly, this trend explains the soul through objective knowledge gained by sensory interaction (Bernstein 2008:9; Cave 2013:16). Therefore, physicalists often contend that the soul is an unnecessary concept (Gray 2010:641). Nevertheless, physicalism remains a critical view of the soul, since the rejection of a concept remains a specific perspective on the subject. As William Carroll (2015:19) explains, '[r]ejection of the idea of human souls is connected to the wider rejection of any fundamental, distinguishing characteristic of living things' and thus still influences the question of 'what it means to be alive'. Physicalism is also closely related to the scientific world of technology; hence, the denial of the soul reveals important aspects of being in relation to technology. An exploration of the film Wit (2001) reveals this perspective and its importance to the notion of the soul.

On account of the multiple ways that the soul can be defined and interpreted, I wish to follow acclaimed author and theologian Mark Goldblatt's (2011) description of the soul. Goldblatt (2011) refers to the soul in everyday denominations as 'the voice-inside-our-head'; he explains that the soul is:

[T]he me-ness of me, the sense of first personhood on which the rest of my consciousness experiences hang. It's the rooting existence, stripped of language and memory, stripped of thought and disposition; it's the unified presence by which I differentiate myself from whatever I encounter. I am not the thing I encounter; I am the thing doing the encountering.

Accordingly, this article considers the soul as the essence or core of a being that determines its true actuality, which distinguishes the self from others and becomes the life force within one's existence. Therefore, I interpret the soul in its most basic form (admittedly an oversimplification of the concept) as the actual essence, substance or principle of all living things, in order to encompass a wide variety of global views on the soul. Naturally, this qualification implies my belief in the existence of the soul. I acknowledge my subjective position as author, but view this as an enabling factor, which provides me with a horizon to engage with the digital world and various perspectives on the soul. In addition, to incorporate a variety of global conceptions of the soul and overcome a biased argument, I recognise, integrate and identify aspects of a possible monistic soul (the soul and body considered as one) and dualistic soul (the soul and body considered as two distinct units) in my understanding and discussion of the soul in the New Digital Age. I also remain conscious of the opposing physicalist/materialist point of view that considers the soul as an unnecessary concept and critically consider this probability as well. As mentioned, the growing interest in a materialist/physicalist worldview also tapers the space for discussion on the soul in a technological and materially driven world. However, later in this article I argue that this perspective, as presented in the realm of visual culture, often also conversely opens up a specific space for deliberations about the soul.

Based on this awareness and comprehension of the soul, we can now identify the phenomenon's space and pertinence in the New Digital Age by examining how visual culture examples depict the soul in relation to technology.

The soul and technology in visual culture

Spike Jonze's her

Set in the not-so-distant future, her (2013) tells the story of Theodore Twombly, a lonely man going through a painful divorce, who falls in love with Samantha. However, Samantha is not a human being, but an operating system (OS). Theodore's life, in the near future, revolves around his job, writing letters on behalf of others at the online service beautifulhandwrittenletters.com, playing immersive video games and having sexual relations with strangers over the phone. This dull (perhaps soulless) lifestyle leaves Theodore feeling lonely and isolated. In desperate need of company, he buys the latest OS on the market to replace his phone. The OS is an artificial intelligence (AI) that can grow psychologically, as her advertisement guarantees: she is 'not just an operating system' but a 'consciousness'. The OS and Theodore quickly become friends. Soon their friendship develops into an intimate romantic relationship and a love story unfolds between a man and a technological object. The film thus depicts a technological dystopia (or arguably utopia) that presents humanity's relation with technology. Moreover, the film intertwines human characteristics, the soul and love with technology.

As a representation of how humans develop a relationship with technology and what this relation might look like in the close future, the film conveys prominent thoughts on the soul within the New Digital Age. Jonze's future bears an uncanny resemblance to the world's present state, so similar that Bergen (2014:2) calls it 'a future eerie only in its incredible likeness to the present'. Theorists such as Kurzweil, Lanier and Rushkoff (cited by Ringen 2014:17) all imagine this depiction of the future as possible arguing that her is a plausible prediction of the developing relation between technology and the soul. Jonze's her opens up a space for the soul in visual culture in two ways. Firstly, by creating a character as an OS who appears to show signs of having a soul, the film asks the viewer to consider important questions such as, can man have a relationship with technology and moreover, does technology show signs of having a soul? Secondly, by telling the story of an ensouled technological device, her questions what the consequences of such advanced technologies are to the human soul and community. In the following overview of the film, I show how her portrays technology as animistically ensouled. I also consider how the film creates room for discussion and interpretation of the consequence for the human soul in the New Digital Age.

Samantha, as an operating system, arguably shows signs of having mind and soul, even though she is run by AI. Her being correlates with the above definition of the soul as the essence of life. In particular, it closely relates to an animistic perspective of the soul, since an object is believed to show human characteristics. Samantha is "born" into Theodore's computer in the installation scene, during which he installs the OS software. He is prompted to answer a few short questions and chooses the gender of the voice he wishes to hear. By installing and introducing her to the world, Theodore helps Samantha come to life. The insert in the screenplay is reminiscent of the typical birthing process and gives Samantha soul:

... [h]e waits, not sure how long it'll be. The only sound is the quiet whirring of disks writing and drives communicating. The computer gets louder, humming, creating a higher pitched sound, finally climaxing in a harmonic, warm tone, before going silent. He leans forward, waiting to see what'll happen. A casual FEMALE OS VOICE speaks. She sounds young, smart and soulful (Jonze 2013; emphasis in original).

The screenplay then also highlights that the film gives technologies human traits, such as a soul. For example, in the above insert, the drives are 'communicating' with one another and have a 'warm tone'.

Furthermore, Samantha also shows soulful signs of intellect, desire and potentiality. As an OS she can process information at a speed that exceeds human abilities - she is able to read a whole book in two one-hundredths of a second - thus her knowledge and intellect grow exponentially every day. In addition, her intelligence develops autonomously. The film shows that the OS's work together and improve based on their own experiences. They do not develop owing to human involvement. For instance, Samantha and a group of OS's write an update that improves their processing platform, they then shut down independently to install this update.

In terms of desire, Samantha also has a will of her own. Her sentences often start with the words 'I think' and 'I want', which highlight her independence. She does not always do what is expected of her and is not always available to talk to Theodore, disproving that people control her or that machine is at service of humans. For example, in one particular scene where Samantha and Theodore discuss their relationship, Theodore immediately starts telling Samantha what he wants and needs, but she interrupts him to remind him that she too has certain expectations from their relationship. In fact, all of the OS's throughout the film prove to have an autonomous nature, as Amy (Theodore's friend) tells Theodore about a friend who wanted to initiate a relationship with her OS, but the OS dismissed her - indicating the OS's have their own desires.

Described in the film as having a consciousness, Samantha, just like humans, experiences emotions that often overwhelm her, until she learns to acknowledge them and describe them. For instance, Samantha shows signs of jealousy towards Amy; she feels hurt by Theodore and often gets angry, annoyed excited and sad. If consciousness is understood as an aspect of the soul, the presence of Samantha's consciousness indicates the possible presence of a soul. In addition, Samantha is able to fantasise about experiencing physical sensations. She fantasises that she has a human body: 'I could feel the weight of my body and I was even fantasi[s]ing that I had an itch on my back ... I imagined that you scratched it for me' (Jonze 2013). During Samantha and Theodore's first sexual encounter, Theodore creates a sense of body for her by telling her that he would touch her face. In response to this, Samantha is surprised to find that she can detect her own skin: 'I can feel my skin ... I can feel you' (Jonze 2013). The moment is also effectively reproduced in the audience as they only see a black screen during this time, therefore they are forced to, like Samantha, imagine the sensations. This reinforces her "viceralness" to the viewer, owing to the fact that she now shares a mutual experience with the audience.

Based on the film's portrayal of Samantha as an embodied consciousness that is 'born', while showing clear signs of living characteristics including knowledge, desire, emotional and visceral embodiment, as well as has her own essence of being, it can be deduced that she is an example of the animistic belief of a technological object with a soul. In other words, the technological operating system in her is an embodied soul. Through the character of Samantha, the film therefore shows technology in relation to the soul and opens up a space for the discussion on the nature and plausibility of such a soul within technological beings. If there is a possibility that technology could show signs of having a soul within the New Digital Age, what are the consequences for human beings and the human soul? Is it possible to sustain a meaningful, harmonious world and sense of being with such entities?

To a certain extent, her answers some of these questions, but with its open ending and various ways of interpretation, the film leaves the audience to consider and contemplate the effects of ensouled beings in the New Digital Age. Jonze himself calls the future depicted on the screen a form of utopianism (Stein 2014:43). The setting of the film is warm, easy and peaceful, as everyone seems to live together in harmony with one another, the environment and technology. The people are friendly and treat each other with mutual respect. Several critics have argued that this future illustrates a disconnected and isolated lifestyle (Bell 2014:23; Stein 2014:43; Bergen 2014:2), which closely resembles Sherry Turkle's (2011) concept of being 'alone together' in a technological world.6 This point of view could possibly be deduced from Theodore's desire for connection and love, which he cannot satisfy through his human relationships, as well as Jonze's personal description of the setting: 'Everything is getting nicer every year - all the design, the food, the coffee. Everything is easy now. You don't get lost anymore. It's the idea of a utopian future that is also full of isolation and loneliness in all the niceness' (as quoted in Stein 2014:43). However, various occasions in the film suggest that this disconnection does not necessarily hold negative connotations such as discord or hostility. For instance, when Theodore sneezes near a stranger, described as a 'nice lady', she says 'bless you' to him. Additionally, while Theodore is in a fluster searching for Samantha, tripping, falling and struggling to pick up his phone, strangers 'come over to check if he's okay', but he just 'says he's fine' and 'runs off'. Hence, it can be argued that this disconnection from others is simply a part of Theodore's personal development and character; he prefers to stay isolated from others and this is not necessarily an indication of a detached technological environment.7

A harmonious life with technology is also visually represented throughout the film by the combination and peaceful co-existence of the artificial and natural world. In her, these two worlds and their typically associated genders are blended and unclear, most obviously portrayed by the relationship formed between Theodore and his OS - a human being falling in love with a piece of technology.8 Aesthetic devices further highlight this harmonious integration. For example, Theodore's computer and phone are both technological objects, yet they are covered in earthly materials, such as wood and leather (Figure 1). Other examples include Theodore's apartment elevator that projects a tree that moves as it travels up and down the computer that transcribes Theodore's words into handwritten scripts, as well as the video game that Theodore plays where his avatar has to make his way through a series of caves. In addition, the mentioning of philosopher Alan Watts in the film also strengthens the combination of the two worlds. Watts is considered to be a philosopher who attempts to bridge the gap between nature and culture, as well as eastern and western paradigms (Bergen 2014:5). Notably, harmony is also a characteristic of the soul, most prominently found in animistic thought. Therefore, the film represents this aspect of the soul in its visual representation, content and questions it poses to the viewer. Moreover, by asking the viewer whether the New Digital Age will have a peaceful, positive impact on the human soul, or an isolating, separating affect from others, the film prompts us to not only contemplate the plausibility of the soul within technology, but the repercussions for the human soul in terms of technological innovation. As a result, her opens a space for deliberation for the soul in terms of technology through the means of the visual. It presents its audience with ideas concerning the soul in a technologically-driven future, that emphasises the importance of the concept in contemporary society.

Artworks by Aleksandra Mir

Swedish/American artist, Aleksandra Mir, is most prominently known for combining images of faith with images of technology and science. For example, in The dream and the promise (2008) she presents a series of collages that combine images from the Kennedy Space Centre in Florida and Baroque churches of Sicily. As an artist she 'considers global events in popular culture such as the moon landing, the development of mass aviation culture and the progress of various space programs to have a great influence on how we live and perceive ourselves in the world' (Mir 2013). Mir argues that there are several propositions that estimate that technology and faith are opposing entities, yet there is considerable evidence that the two notions converge and relate to one another. Particularly, Mir is interested in the technology of space travel and its relation to the journey of the soul and religion.9 In several of her exhibitions, such as The Dream and the Promise, The Space Age Collages, Aim at the Stars, Astronauts, The Promise of Space, as well as The Passion (all 2008), Mir combines images of faith with images of technology and science through means of paper collage.10 As a result, Mir merges images of space travel and religion to indicate similarities between the journey through space and the journey of the spiritual soul. Through her depiction of space, Mir opens up a discursive space to consider the soul in relation to technology.

This amalgamation of space travel and the spiritual soul, which occurs throughout Aleksandra Mir's work, emphasises important aspects of the journey of the soul, especially in terms of a dualistic and gnostic outlook on the soul. Perhaps the most prominent gnostic feature in the collages is the collision of two seemingly opposing realms. Following the gnostic train of thought, Mir's work balances and brings together two different components of life. For example, in The promise of space one of the 33 images places a typical religious image of Sunday school teaching, or then relatedly the image of Jesus teaching the disciples, on Mars, while another shows a folkloric religious icon playing piano on the moon. In both these images, the world of space and symbols of the transcending soul collide: 'here are halos mixing with astronauts' helmets, cherubs frolicking with rockets on the launching ramp, the dresses of angels merging with the suits of cosmic voyagers' (Mammi 2010). As both these images reveal, Mir imagines that it is possible for these realms, to not only co-exist, but also to unite.

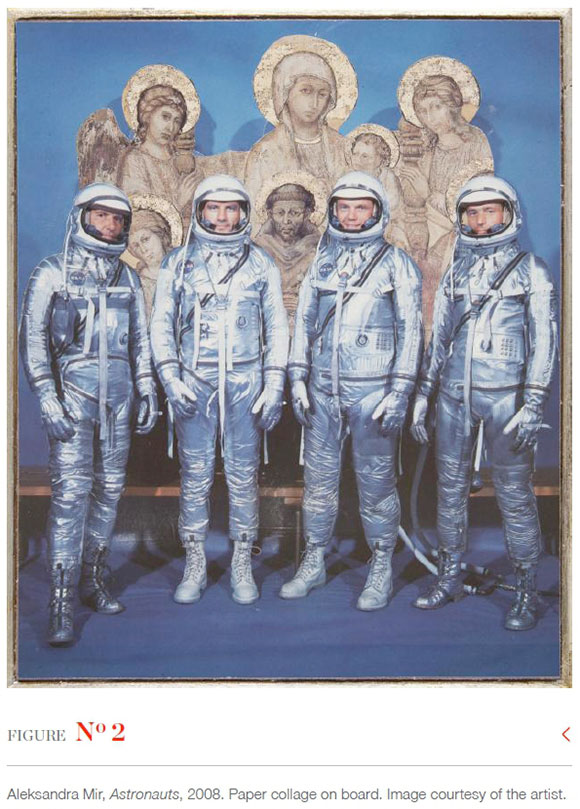

Mir's artwork also incorporates angels and celestial beings. In The passion and Astronauts, for example, Mir relates the ideas of angels and astronauts arguing: 'if angels and astronauts share the same sky, isn't it time they were introduced?' In doing so Mir shows how certain aspects of space travel and the gnostic journey of the soul have correlating parallels. For example, Mir suggests that the circular halo of angels resembles the astronautic suit's head, as yesterday's halo becomes today's helmet (Herbert 2013). Astronauts and angels, in The passion and Astronauts, therefore manifest similar qualities. This manifestation correlates with Serres (1993:7) who argues that technology shows angelic characteristics. For Serres (1993:8), 'aircraft carry letters, telephones, agents, representatives and the like: we use the term communication to cover air transport as well as post. When people, aircraft and electronic signals are transmitted through the air, they are all affectively messages and messengers'; they are postmodern angels. In addition, Irigaray considers the angels as a messenger of potential and possibility in current society. Irigaray's angels are filled with potential to defy the norm, transcend space and destroy the monstrous as she explains: '[a]ngels destroy the monstrous, that which hampers the possibility of a new age; they come to herald the arrival of a new birth, a new morning' (Irigaray 1993:15). Just as Serres and Irigaray's angels transcend space, are omnipresent and evoke expressions of awe, so too do astronauts literally transcend space, and satellites become omnipresent messengers and the space mission often evokes a sense of wonder from onlookers. Mir plays with the similarity throughout her images as clearly seen in Astronauts (Figure 2) where the astronauts are paired with angelic entities, indicating their correspondence.

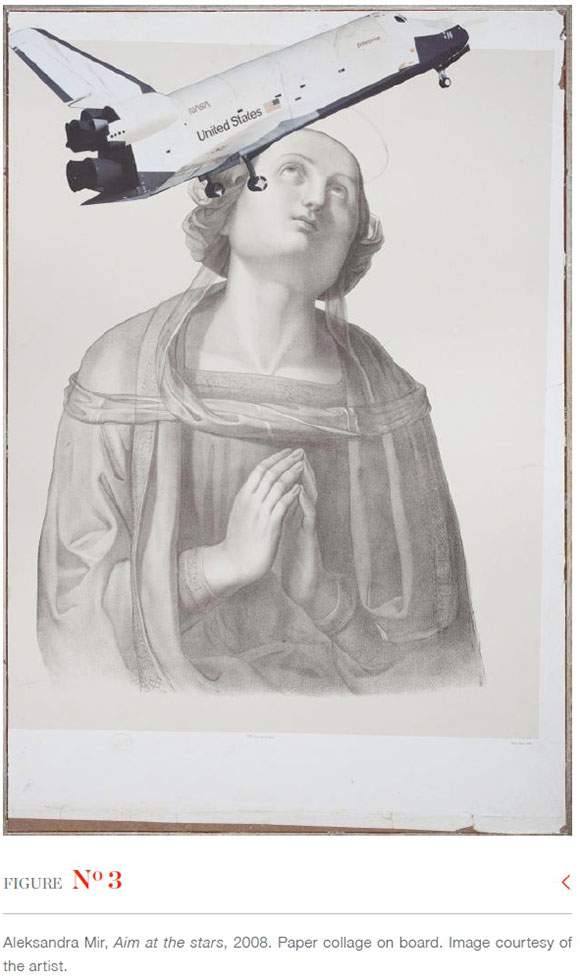

Furthermore Mir's work demonstrates the concept of the gnostic soul's desire to escape from the evil challenges on earth. The technical spectacle of the spacecraft launching from earth demonstrates this sense of escapism (Romanyshyn 1989:21). Mir uses the spectacle of space travel throughout Aim at the stars, as she depicts religious figures seemingly in admiration of the space shuttle, and its potential. In one of the 23 images in the series, an image of Jesus is placed alongside a satellite, in such a way that it seems as if He is looking up, towards the satellite, as He would towards God (Figure 3).

This could perhaps imply that the manner for the religious soul to break free could be through the means of technology. In a similar image, Jesus is shown holding a satellite as He is often portrayed in popular religious imagery, holding a Bible or the lamb. It is as if Mir presents Jesus as endorsing or recommending technology as a means of absolution of vindication, arguing that technology has the potential to free the human soul and arrange a meeting with the divine. Extending this notion another image of a religious icon is shown praying towards a space shuttle, flying into space, revealing once more the conflation of religious and astronautic images.

The gnostic outlook on the soul is also often concerned with the notion of rebirth. Some of Mir's works also echo this notion through the astronautic body, floating in space attached to the spacecraft, which Romanyshyn (1989:18) suggests represents the reincarnation of the foetus being reborn through technology. This is evident in Astronauts (Figure 4) where the infamous image of the astronaut floating in space attached to the craft by a cord is seen, with added religious iconography. The umbilical cord of cables attaches the astronaut to the spaceship as if it is being reborn. With the added image of faith, it appears as if the technological rebirth although miles from earth is still within the space of the divine.

This notion of the space journey and astronauts in Mir's artworks evokes comments on posthumanism, which (as established) forms a critical part of dualistic and gnostic perspectives on the soul in current society. If posthumanism is considered to be the transcendence of nature through the means of technology, then the astronaut overcoming the laws of nature by merging with a technological space suit and craft, in order to travel through space and escape earth, is the embodiment of posthumanism. In addition, Mir's work suggests that this integration of the human body and technology - in the form of the astronaut - is not only in the pursuit of extending humanism, but it is also aimed at the soul escaping the bodily prison. To put it in Heideggerian terms, the technology of space travel enframes nature as a standing reserve ready to be used to escape the limitations of the earth. The astronaut is the posthuman, technological body seeking the spiritual through the means of technology.

Hence, the gnostic posthuman phenomenon, as it manifests in the astronaut, poses an important debate concerning the relationship between technology and the soul. Wittcox (2014) suggests that this aligning of science and faith brings forth important questions regarding the notion of the soul such as:

What is the purpose of leaving and going so far away? How far away from home can you go, and still be relevant to the people you left behind? What happens to the ego when tangible references vanish? Is the risk worth it? Is scientific discovery a way to meet or challenge God? And is extreme solitude path to self-relisation [sic] or simply a process to verify one's existence among others?

This highlights the ongoing debate of the posthuman future: does posthumanism have the potential to enhance and save the soul, or does it hold the threat of destruction and detachment of the soul? To a certain extent the notion of the astronaut, as it is presented in Mir's work, argues that posthuman technology has the potential to aid the soul, since the space journey sets forth the soul's spiritual journey. Accordingly, Mir's artworks, as well as other similar visual culture depicting space travel such as Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity (2013) or Ridley Scott's The Martian (2015), opens up a space to consider posthuman technology in relation to a spiritual soul.11 Moreover, within this space where the spiritual soul exists amongst technology, technology is positioned as an aid and freeing mechanism to the soul, which, similar to her, also initiates further conversation and debate on the effects of technology on the soul.

Mike Nichols's Wit

Another visual example that considers the effect of technology on the soul is the television film Wit (Nichols 2001). However, where the above examples consider the impact of technology on the soul, Wit considers how a disregard for a soul, in favour of technology and science, impacts human beings and human dignity. Wit poses this question by presenting an unromanticised narrative that considers the effects of the medical field, technological treatments and physicalist beliefs (Knox 2006:234). The film is also described a 'rehearsal' (Knox 2006:234) of the reality of death in a techno-secular society ignorant of the soul. By representing these realities the film also introduces the importance of the soul within the New Digital Age and shows the viewer the consequences of declaring the soul, and other notions of being, irrelevant.

Released in 2001, Nichols's television movie was received with great acclaim, as critics commended it for its honest and heartbreaking portrayal of the reality of being diagnosed with terminal cancer. Set mainly in a hospital and filled with graphic visuals of the human body undergoing treatment, there is no doubt that this film is predominantly centered on having cancer and coming to terms with the notion of death. It is then no surprise that it has been this aspect that critics and theorists alike, such as Knox (2006) and Ebert (2008), explore in review of the film. However, upon closer investigation it becomes clear that Wit is also a film that makes a strong case against physicalism as well as against a disregard for the notion of the soul and human dignity. In a contemporary society overwhelmed by the effects of the New Digital Age, where viewers are constantly bombarded with popular culture that embraces technological development as well as secularity, films like Wit are increasingly important to present a counter-argument or serve as a reminder of the consequences of a world dominated by technology and science with little regard for the human soul. Wit counters physicalism by presenting both a technologically driven environment, which holds no consideration for the human soul and human dignity, as well as the consequences of such conditions. In doing so, I argue that the film makes a sufficient appeal against a physicalist worldview, by simultaneously presenting a techno-secular world as well as the repercussions thereof. Wit shows how the soul is more valuable than the pursuit of technology, knowledge and techno-secularity.12

Wit commences with a close-up shot of a doctor's face telling the viewer directly '...you have cancer' (Nichols 2001). The camera then zooms out to reveal professor Vivian Bearing talking to a doctor, who confirms that she is diagnosed with stage four ovarian cancer. The doctor, Dr. Kelekian, recommends that she undergo severe experimental treatments as part of a research study. From this moment on, the film affects the audience personally, as they not only follow, but also become part of Professor Bearing's journey of treatments, until she dies alone in the hospital. Towards the end of the film, she comes to the conclusion that human compassion and contact is more important than intellect, wit and techno-scientific knowledge. Accordingly, the film indicates that a predominantly physicalist environment puts human dignity and the human soul at risk.

Human dignity in itself is a heavy-loaded concept, which is closely related to the concept of the soul. Ancient theologians argue that man's dignity is reflected in his resilience and the immortal soul. In turn, Immanuel Kant (in Bostrom 2007:2) states that human dignity is a human value found in all individuals that must be respected by treating a person as an end and not a means to an end. Kant explains that human dignity is maintained if we treat others and ourselves as more than just utilities or tools (Bostrom 2007:2). Following these definitions of human dignity, Bostrom (2007:3-4) argues that it is a quality and virtue, which places all beings at an equivalent moral and social status of being worthy of respectful treatment. Additionally, political scientist Francis Fukuyama (2002:160) considers human dignity in terms of the current New Digital Age and medical ethics, articulating human dignity as: 'the idea that there is something unique about the human race that entitles every member of the species to a higher moral status than the rest of the natural world'. Considering the theological understanding of human dignity, as well as the above definitions, human dignity is a distinctive value, which precipitates human beings to treat others, as well as themselves with integrity and respect, in an empowering manner. Human dignity is also considered to be a force (or a result) of the soul, because the soul is the exact essence that gives beings the right to be treated with dignity. Thus, when it is argued that physicalism jeopardises human dignity, it implies that a part of the soul is also jeopardised.

Wit critically portrays the effects of a physicalist point of view and approach to life. It unequivocally reveals the danger in elevating the realm of the physical above the spiritual and soulful, while warning against the dehumanising consequences of technology. Throughout Wit the physicalist world that Vivian enters during her treatment (the hospital) completely ignores the notion of the soul. This "world" is then placed alongside other aspects of Vivian's life, outside of the cancer - such as poetry - that recognises soul and spirit. Therefore, the audience is able to consider the physicalist perspective in broader terms. It is thus not a film portraying a physicalist perspective from which deductions about technology can be made, but it is rather a film portraying a physicalist perspective and how its glorification of technology threatens human dignity and the soul.

The world of medicine that Vivian faces represents a physicalist worldview. Vivian is hospitalised as an in-patient for eight cycles of strong treatments of chemotherapy, which have destructive side effects on her body. Her treatment forms part of a research experiment, which contributes to knowledge creation on cancer and cancer treatments. As seen throughout the film, the three words 'research', 'experiment' and 'knowledge', underlie the hospital's attitude to all patients. To them the work, the medical field, the intellect and the science behind the cancer are the most important; the person undergoing the treatment is disregarded. Illustrating this, Vivian explains to the audience: 'the young doctor, like the senior scholar prefers research to humanity. At the same time the senior scholar, in her pathetic state as simpering victim wishes the young doctor would take more interest in personal contact' (Nichols 2001).

The fundamental characteristics of physicalism are, therefore, clearly visible in the hospital governed by knowledge, experiment and research. The properties of the physical are signified throughout the hospital in the form of cancer cells, the treatment of the human body, bodily fluids, medications, scientific names, X-rays revealing cells and bone structures, as well as machines. The hospital focuses on physical matter. Emphasis is also placed on the physical deterioration of Vivian's body. In a particular scene, the doctor and his students do a routine check-up on Vivian, matter-of-factly noting all the medical effects of treatment thus far, including 'metastases', 'lymphatic involvement', 'lowering blood cell counts', 'nephrotoxicity will be next', 'hair loss' and much more. During the scene, the only focus is on medical terms, biological manifestation and physical changes. There is no compassion or personal touch shown, the only importance is the physical realm as Vivian explains, 'I just hold still and look cancerous'. The students are even commended on their 'excellent command of details', stressing the significance of physical particularities.

The film portrays that in the current New Digital Age healthcare is primarily technological (Krueger 2010), since medical machines, medicines and treatments have essentially reshaped medical care. In addition technology in medicine has led to a 'paradigm shift' in approaches to patient care (Fennell 2008:1), as seen throughout Wit. The constant presence of a telephone, drip, and machinery connected to Vivian and a wheelchair symbolises the constant presence of technology in the hospital. This constant presence reminds the viewer that the medical treatment causing Vivian's suffering is fundamentally technological. It is also ironic to note that the telephone is always present and yet of no use to Vivian, as she has no friends or family to contact. The telephone has a purely technological presence and is only used by the doctors to call a code when she is dying. Although a telephone is a technology that establishes connection and communication between people (Davis 1998:81-82), in Wit it simply emphasises the lack of contact that patients have in the technologically-governed hospital. Notably the telephone and wheelchair in the physicalist environment of Wit are sterile and represent isolation, danger, detachment and decay, which differ significantly from typical depictions of similar objects in popular culture, usually presented as animated, reliable, personal and comforting.

Since physicalism highlights the physicality of the human body, the deterioration of Vivian's physical body becomes the 'visual pivot of the film' (Knox 2006:244). Nichols skillfully manifests the suffering of the physical body through technological treatment, employing several close-up shots of Vivian's face and head (Figure 5). As Vivian loses her hair and her face becomes haggard, the audience is reminded of iconic faces of suffering, from the survivors of death camps to the tortured patients undergoing chemotherapy (Knox 2006:244). Vivian's bald androgynous-like head reveals the structure of her skull, symbolising death and evoking sympathy from the viewer. Paradoxically, it is not the physical pain that Vivian undergoes that is the most difficult, but rather the de-humanising and lack of human dignity that comes with the treatment and lack of kindness and respect shown by the doctors.

Another aspect of physicalism evident in the hospital environment is the presence of the macro world, often reduced down to the micro world. As an established and recognised literary professor, Vivian is a complete being, however while undergoing treatment she is literally reduced to micro pieces. She is merely seen as cancerous cells, vitals, lab counts, chemotherapeutic agents, bodily systems and a tumour. She is reduced from the macro world to the micro world by the medical profession. It is exactly this reduction that Kant argues should be avoided if human dignity is to be kept in tact. Thus, the reduction to micro entities, results in the diminishing of Vivian's humanity and dignity, as she notes:

Kelekian and Jason are simply delighted. I think they see celebrity status for themselves, upon the appearance of the journal article they will no doubt write about me. But I flatter myself. The article will not be about me, it will be about my ovaries. It will be about my peritoneal cavity. Which despite their best intentions, is now crawling with cancer. What we have come to think of as me is, in fact, just the specimen jar. Just the dust jacket. Just the white piece of paper that bears the little black marks (Nichols 2001).

In the hospital, the doctors' main goal is to gather research from Vivian, which highlights the trend of rationality and reason within physicalism. The doctors want to extend their knowledge and enquire through experimentation to find a solution or cure, and explain the phenomena in a simple manner. Paradoxically, this obsession with reason, logic and the search for knowledge leads the doctors to behave in a completely dehumanised manner, as they forget to consider the patient as a human and person. In a particularly traumatic scene at the end of the film, Jason (the resident doctor on Vivian's case) checks-up on Vivian, who is already dead. However, he only notices this after doing a couple of checks. He is so caught up in the study, that he then continues to resuscitate her (in an extremely humiliating manner), even though she signed an agreement to not resuscitate. When questioned about his actions, he argues that 'she's research' thereby highlighting his unreasonable preoccupation with the pursuit of reason.

Throughout Wit the physicalist fields of neuroscience, medical sciences, illness and disease are prominent. Vivian is terminally ill, as revealed at the beginning of the film, her deterioration is visually portrayed throughout the film in graphical manner. She is placed under intense medical treatment and therefore finds herself in the midst of a physicalist world. As mentioned, modern medicine, which follows a physicalist approach, disregards the personal in exchange for the physical (Whatley 2014:962). This disregard grows to such an extent that in Vivian's case, patient care is dismissed (Whatley 2014, 963). Vivian does not receive patient care that is considerate, caring or even humane. She is treated as an object. During her diagnosis, the audience is already made aware that the doctors do not intend to treat her as a person with dignity. She is left lying down with her feet in stirrups, exposed to the hospital by a resident (an old student of hers), who shows no sign of empathy or sympathy towards her situation. After the exam, she remarks: 'that was hard (...) yes, having a former student give me a pelvic exam was thoroughly degrading. And I use the term deliberately (...) I could not have imagined the depths of humiliation'.

Naturally then the notion of mortality, closely related to the soul, is also prominent throughout the physicalist worldview presented in Wit. Hospitals have traditionally been known as spaces of death and fear, even though their main goal is, ironically, to save lives (Laderman 2003:94). In addition, dying in a hospital room replaces the transcendence of death with technology and innovation, as Laderman (2003:4) explains:

A clinical gaze emanating from an assortment of doctors redefined the existential status of the dying individual into one that emphasi[s]ed the triumphs of science and diminished the spiritual needs of the patient. The dominance of a medico-scientific framework for monitoring, interpreting, and responding to signs of death transformed the (...) process of dying, and replaced the human family drama surrounding the deathbed (...) with a professional performance at the hospital bedside that depended on equanimity, rationality and detached commitment to saving the life of the dying patient.

The technological and physicalist nature of the hospital has transformed the process of dying and the concept of mortality into a detached practice. In particular, this idea of physicalist death is clearly illustrated in Vivian's passing at the end of the film. Her body is brutally pounded by emergency staff, her naked body exposed and rolled around. When the doctors leave, realising they are not able to save her, she is left, as a dead corpse lying alone in her hospital bed with no human dignity. She is completely degraded, dehumanised and detached from the world. This act brings a new meaning to the word mortified.

Furthermore, the tone of death and reminder of the degraded soul is intensified throughout the film with the recital of the sonnet Death be not proud (1633) by English poet, John Donne (1572-1631). The sonnet too presents a physicalist perspective of death, as the meaning of the poem is revealed in the film. Vivian explains, Donne argues that death 'is no longer something to act out on a stage with exclamation marks. It is a comma. A pause'. It is just a simple act that separates life from death with 'no insuperable barriers'. The poem then foreshadows Vivian's death as a simple, unembellished, everyday happening in the hospital. Knox (2006:245) describes this as medicalised death, or death controlled by medical technologies.

It is thus exposed that the hospital and treatment that Vivian undergoes represent a physicalist outlook, focusing on the physical body and disregarding the humane. Nevertheless Wit does not simply present a physicalist world to its audience and leaves them to negotiate the consequences of such a world on their own, instead it also gives the viewer a clear message. The film shows how an approach to life governed by technology and physicalism undermines the soul. It warns that if technoscience continues on this path it could turn human beings into objects, stripping them of their dignity.

Vivian's soul and human dignity are taken away by the technology and pursuit for research of the medical profession (Knox 2006:248). Notably it is still not these technologies that kill Vivian, her death remains the result of her incurable cancer. Thus, it cannot be argued that the film views technology as killing machines, but rather as entities able to damage or wound the soul. In this manner, the film reminds the audience that in the pursuit of technological development, human kindness and the human soul must not be forgotten.13

Fortunately, Wit presents a small sense of hope to the audience. The character of nurse Susie treats Vivian with respect and gentleness: she keeps Vivian company, brings her ice lollies, explains procedures to her and tries to remind the doctors that she is just a person. Susie brings a sense of relief to the maltreatment, however this relief is short-lived as she (and the viewer) is constantly reminded that she is powerless in the struggle against the institution motivated by technology and research. For example, Jason asks her 'what do they teach you at nursing school?', while a coding medic shouts at her 'who the hell are you?' indicating that these doctors regard their job as more important than hers. Hope is also conveyed when professor Ashford (Vivian's former professor) visits Vivian in the hospital. In this particular scene, she gives Vivian the touch of human kindness that she so desperately needs, reading her the story of The Runaway Bunny. As the professor explains, the story of the bunny that tries to run away from its mother is 'a little allegory of the soul. Wherever it hides, God will find it'. Accordingly, the story gives the audience hope that no matter how far technology and science evades the human soul, the realm of the transcendent and humaneness may still be present. This hope is, however, also quickly terminated as the harsh scene of Vivian's so-called medicalised death follows directly after, re-establishing the power of unchecked physicalism.

Based on Wit's depiction of the harmful consequences of an immanent perspective on technology and the soul, the validity of a physicalist perspective in the New Digital Age can be questioned. Science historian William Carroll's recent essay, Does a biologist need a soul? (2015) critiques and questions the notion of physicalism, arguing that perhaps physicalism should recognise the possibility of the soul. As a visual example, Wit reflects this argument, by showing that even physicalists need the soul. In doing so, the film also creates room for discussion on the soul in a space strictly reserved for technological reasoning. In other words, even when the New Digital Age is understood from a materialist point of view ignorant of the soul, the notion of the soul still becomes a matter of consideration. Wit proves that the notion of the soul still has relevance in a technological environment and argues that eliminating the concept from conversation, in favour of technoscience, comes at a serious price: human dignity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, contemporary visual culture reveals that the soul is prevalent in relation to technology and the New Digital Age. The soul is a significant concept that incorporates various worldviews and cultures that can be traced throughout prominent visual examples, such as her, artworks by Aleksandra Mir and Wit. By exploring these visual examples, it becomes clear that it is increasingly important to discuss the notion of the soul in the context of the digital world. A discussion of the soul in relation to technology, as represented in various visual examples, reveals that technology can possibly manifest characteristics of the soul in the future and presents us with the power to negate between technology as an aid or a detriment to the human soul. Moreover, by creating a space for discussion on the soul in the New Digital Age, visual culture is able to represent a world without the soul and its severe consequences, such as a loss of human dignity and empathy, creating an argument against such an omission. Thus, the realm of the visual prompts us to keep considering the soul, through a variety of perspectives, such as monism, dualism and physicalism that incorporates spiritualism, religion, different cultures and a global outlook. By exploring these visual examples it is clear that the soul is 'alive and well' in the world of technology and there remains space to deliberate its properties in order to determine the effects of technology on the notion of being human.

REFERENCES

Ayisi, EO. 1972. An introduction to the study of African culture. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers. [ Links ]

Bell, J. 2014. Computer love. Sight & Sound 24(1):20-25. [ Links ]

Bergen, H. 2014. Moving "past matter": challenges of intimacy and freedom in Spike Jonze's her. Artciencia VIII(17):1 -6. [ Links ]

Bernstein, A. 2008. Objectivism in one lesson. An introduction to the philosophy of Ayn Rand. Maryland: Hamilton Books. [ Links ]

Bird-David, N. 1999. "Animism" revisited: personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology 40(S1):S67-S91. [ Links ]

Bostrom, N. 2007. Dignity and enhancement, in Human dignity and bioethics, essays commissioned by the President's Council on Bioethics. March 2008. Washington D.C:173-207. [ Links ]

Brown, WS, Murphy, N & Malony, HN (eds). 1998. Whatever happened to the soul? Scientific and theological portraits of human nature. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Campbell, HA & Looy, H (eds). 2007. Transcendence and beyond. A postmodern inquiry Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Carroll, WE. 2015. Does a biologist need a soul?. Modern Age Summer:17-31. [ Links ]

Casey, TG. 2013. The return of the soul. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 102(405):31-42. [ Links ]

Cave, S. 2013. What science really says about the soul. Skeptic Magazine 18(2):16-18. [ Links ]

Cohen, J & Schmidt, E. 2013. The New Digital Age: reshaping the future of people, nations and business. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

Crane, T. 2000. Dualism, monism, physicalism. Mind and Society 1(2):73-85. [ Links ]

Crichton-Miller, E. 2013. Monuments for our time. RA Magazine. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.aleksandramir.info/bibliography/crichton-miller_emma_monuments-for-our-time_ra-magazine_london_spring-2013 Accessed 5 July 2015.

Davis, E. 1998. TechGnosis: myth, magic and mysticism in the age of information. New York: Harmony Books. [ Links ]

Deane-Drummond, C. 2009. Theology's intersection with the science/religion dialogue, in A science and religion primer, edited by HA Campbell & H Looy. USA: Baker Academic:28-32. [ Links ]

Ebert, R. 2008. When a movie hurts too much. [ Links ] [O]. Available: https://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/when-a-movie-hurts-too-much. Accessed 23 January 2018.

Ezzo, D. 2011. New York: Aleksandra Mir at the Whitney Museum. Artobserverd. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.aleksandramir.info/bibliography/ezzo_d_new-york_aleksandra-mir-at-the-whitney-museum_interview_www.artobserved.com_new-york Accessed 5 July 2015.

Fennell, ML. 2008. The new medical technologies and the organizations of medical science and treatment. Health Service Research Journal 43(1):1-9. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1963. The birth of the clinic: an archaeology of medical perception. USA: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Freedman, K. 2003. Teaching visual culture. Curriculum, aesthetics and the social life of art. New York: Columbia University, Teachers University Press. [ Links ]

Fukuyama, F. 2002. Our posthuman future: consequences of the biotechnology revolution. New York: Picador. [ Links ]

Gall, RS. 2013. Fideism of faith in doubt? Meillassoux, Heidegger, and the end of metaphysics. Philosophy Today, Winter:358-368. [ Links ]

Goldblatt, M. 2011. On the soul. Philosophy Now 82, January/February:33-34. [ Links ]

Gray, AJ. 2010. Whatever happened to the soul? Some theological implications of neuroscience. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 13(6):637-648. [ Links ]

Haraway, D. 1990. A manifesto for cyborgs. Science, technology, and socialist feminism in the 1980s, in Feminism/Postmodernism, edited by LJ Nicholson. New York & London: Routledge:199-233. [ Links ]

Heidegger, M. 1977. The question concerning technology. Translated by W Lovitt. New York: Harper & Row. [ Links ]

Herbert, M. 2013. Open space. Sternberg Press. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.aleksandramir.info/bibliography/herbert_martin_open-space_press-release_leuven_sternberg-press_berlin-2013 Accessed 5 July 2015.

Hoeller, SA. 2012. The gnostic world view: a brief summary of gnosticism. [ Links ] [O] Available: http://gnosis.org/gnintro.htm Accessed 8 May 2014.

Hurtado, LW. 2005. Lord Jesus Christ: devotion to Jesus in earliest Christianity. Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Idang, GE. 2015. African culture and values. Phronimon 16(2):97-111. [ Links ]

Irigaray, L. 1993. An ethics of sexual difference. Translated by C Burke & GC Gill. London & New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Jonze, S (dir). 2013. her. [ Links ] [Film]. Warner Bros. Pictures.

Kelly, K. 2010. What technology wants. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

King, JE, King, JE and Wilson, TL. 1990. Being the soul-freeing substance: a legacy of hope in afro humanity. The Journal of Education 172(2):9-27. [ Links ]

Knox, SL. 2006. Death, afterlife, and the eschatology of consciousness: themes in contemporary cinema. Mortality 11(3):233-252. [ Links ]

Krueger, A. 2010. 6 Ways Techonology is improving healthcare. Business Insider. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.businessinsider.com/6-ways-technology-is-improving-healthcare-2010-12?op=1 Accessed 3 June 2015.

Krueger, O. 2015. Gnosis in cyberspace? Body, mind and progress in posthumanism. Journal of Evolution & Technology 14(2), August:77-89. [ Links ]

Kurzweil, R. 1999. The age of spiritual machines. New York: Viking Press. [ Links ]

Laderman, G. 2003. Rest in peace: a cultural history of death and the funeral home in the twentieth-century America. USA: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Linton, R (ed). 1945. The science of man in the world crisis. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Mammi, A. 2010. Tutti figli delle stell. L'Espresso. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.aleksandramir.info/bibliography/mammi Accessed 5 July 2015.

Martins, PN. 2018. Perspectives and controversies: The concepts of soul and body in Eastern and Western cultures. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science 6(2):7-9. [ Links ]

Mir, A. 2015. Aleksandra Mir. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.aleksandramir.info Accessed 5 July 2015.

Mirzoeff, N. 1998. The visual culture reader. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mcghee, M. 1996. The locations of the soul. Religious Studies 32(2):205-221. [ Links ]

Murdock, GP. 1945. On the universals of culture, in The science of man in the world crisis, edited by R Linton. New York: Columbia University Press:123-142. [ Links ]

Murphy, N. 1998. Human nature: Historical, scientific, and religious issues, in Whatever happened to the soul? Scientific and theological portraits of human nature, edited by WS Brown, N Murphy & HN Malony. Minneapolis: Fortress Press:1-30. [ Links ]

Nussbaum, B. 2003. Ubuntu: Reflections of a South African on our common humanity. Refections 4(4):21-26. [ Links ]

Nichols, M (dir). 2001. Wit. [ Links ] [Film]. HBO Films.

Nicholson, LJ (ed). 1990. Feminism/Postmodernism. New York & London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Pasteur, A & Toldson, I. 1982. Roots of soul: the psychology of black expressiveness. New York: Anchor/Doubleday. [ Links ]

Ringen, J. 2014. Can 'her' happen? The experts weigh in. Rolling Stone 1202:17. [ Links ]

Romanyshyn, RD. 1989. Technology as symptom and dream. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Schroeder, R. 1994. Cyberculture, cyborg post-modernism and the sociology of virtual reality technologies. Surfing the soul in the information age. Futures 26(5):519-528. [ Links ]

Scruton, R. 2014. The soul of the world. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Serres, M. 1993. Angels: A modern myth. New York: Flammarion. [ Links ]

Sisson, P. 2018. Space is the Place: The architecture of Afrofuturism. [ Links ] [O]. Available: https://www.curbed.com/2018/2/13/17008696/black-panther-afrofuturism-architecture-design Accessed 13 March 2018.

Stein, J. 2014. Lonely boy Spike Jonze hopes the high-tech love story of her will make you cry. TIME, January 20:41-43. [ Links ]

Turkle, S. 2005. The second self. New York: MIT Press. [ Links ]

Turkle, S. 2011. Alone together. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Whatley, SD. 2014. Borrowed philosophy: bedside physicalism and the need for a sui generis metaphysic of medicine. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 20:961-964. [ Links ]

Wittocx, E. 2014. Aleksandra Mir: The Space Age. Digicult. [ Links ] [O]. Available: http://www.digicult.it/news/aleksandra-mir-the-space-age/ Accessed 5 July 2015.

1 The 'New Digital Age' refers to the present and future of the current technological driven society, often characterised by the hyper-connectivity of Web 2.0, social media and interactive networks (Cohen & Schmidt 2013:3). As a time period it extends from the 'Digital Age' or so-called 'Information Age' that started in the 1970s and encompasses the most recent and anticipated technological developments.

2 See Pasteur and Toldson (1982), King, King and Wilson (1990), Nussbaum (2003), Ayisi (1972) and Idang (2015) for a clear explanation of the role of the soul in African culture. In particular, Nussbaum also relates the notion of the soul in African culture to the specific Ubuntu culture of South Africa.

3 See Martins (2018) for a complete outline of the various beliefs of the soul in western and eastern cultures.

4 See also Scruton (2014) who identifies three categories - dualism, life worlds and overreaching intentionality - that shows similarities to monism, dualism and physicalism.

5 Stemming from Platonism and Cartesian dualism.

6 In her book Alone Together (2011), Turkle explains that although technology connects people and brings more people together, it also leads us to a lonely, distant community where people no longer share intimate experiences and live in so[u]litude. Based on fifteen years of interviews and research, Turkle (2011:295) concludes that people 'expect more from technology than each other'. Thus people exist in a world where they are together, yet alone.

7 From an animistic perspective, isolation and loneliness can also be an indication of respect, arguing that keeping a respective distance from others encourages harmonious relations and a peaceful environment. Thus, the disconnection within her can be interpreted as both utopian and dystopian.

8 Commonly the natural world is gendered as feminine, while the technological world is thought of in terms of masculine traits. It is interesting to note that in the film Theodore and Samantha's relationship switches these conventional genders as Theodore (male) represents the natural world, while Samantha (female) represents the technological world. This extends the merging of these two concepts.

9 Although reviews of her work argue that Mir juxtaposes these images (Crichton-Miller 2013; Ezzo 2011), it is preferred to refer to the collages as a merging or combination, as the artist does not aim to highlight the differences between the images, but rather the similarities and relations (Mir 2013).

10 To view more of Mir's work please visit https://www.aleksandramir.info.

11 Notably, the collision of the astronaut and the gnostic spiritual realm, as presented by Mir, is most prominently a western depiction. However, the idea of space as a place of escapism and overcoming of earthly confides also extends to the notion of AfroFuturism, which depicts a scientific future seen through an African and non-western cultural lens. Within the genre of AfroFuturism, the iconography of spacecrafts, space travel, 'afronaut' is prominent. Further analysis is required to reveal the aspects of the soul within these visuals, but they do indicate that the notion of the astronaut and its relation to the soul exists outside of the frame of western thought. For further reading on AfroFuturism, posthumanism and space travel see Sisson (2018).

12 Notably, the film considers the soul in close relation to poetry and existential depth. In other words, throughout the film the soul is defined or mentioned in terms of poetic devices and the question of the meaning of life.

13 This warning and depiction of medical care is reminiscent of Michel Foucault's The Birth of the Clinic (1963) written in view of the Enlightenment shift towards empiricism. In this seminal work, Foucault (1963, xiv) comments on the influence of empirical observation in the medical field. He introduces what he refers to as 'the medical gaze' (Foucault 1963:9), which is the act of looking of a doctor, onto the human body of his patient. Through observing and examining the patient's body as well as by conducting tests (and in the current Digital Age technological experiments) the doctor is able to gain information about a patient's physiological condition. Foucault (1963:xiv) maintains that this medical gaze allows for an open discussion about any body, which removes the transcendental, supernatural properties of the body and leaves the individual open and vulnerable. Furthermore, applying a medical gaze to a body and discussing it in terms of medical terminology objectifies the body and places the doctor in a position of power (Foucault 1963:89). Wit clearly illustrates Foucault's theory within the Digital Age as it shows how subjecting the body of a patient to strict empirically-based research objectifies the patient's body and leaves the patient (Vivian) fragile and vulnerable subject to the gaze of the medical practitioner. Vivian's body becomes a mere object of research to medical science.