Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of the South African Veterinary Association

On-line version ISSN 2224-9435

Print version ISSN 1019-9128

J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. vol.82 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2011

SHORT COMMUNICATION KORT MEDEDELING

Seroprevalence of Brucella abortus and B. canis in household dogs in southwestern Nigeria: a preliminary report

S I B CadmusI,*; H K AdesokanI; O O AjalaII; W O OdetokunI; L L PerrettIII; J A StackIII

IDepartment of Veterinary Public Health and Preventive Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

IIDepartment of Veterinary Surgery and Reproduction, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

IIIDepartment of Bacteriology, Veterinary Laboratories Agency, New Haw, Addlestone, Surrey KT 15 3NB, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

A preliminary serological study of 366 household dogs in Lagos and Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria, was carried out to determine antibodies due to exposure to Brucella abortus and B. canis, using the rose bengal test (RBT) and the rapid slide agglutination (RSA) test, respectively. Results showed that 5.46 % (20/366) and 0.27 % (1/366) of the dogs screened were seropositive to B. abortus and B. canis, respectively. Of all dogs, 36 had a history of being fed foetuses from cows and 11 (30.6 %) of these tested positive in the RBT. Our findings, although based on a limited sample size and a dearth of clinical details, revealed that dogs in Nigeria may be infected with Brucella spp. given the wide range of risk factors. Further studies are recommended to elucidate the epidemiology of brucellosis in dogs and its possible zoonotic consequences in the country.

Keywords: Brucella canis, Brucella abortus, brucellosis, clinics, cow foetuses, Nigeria, seroprevalence, zoonoses.

Brucellosis is an infectious disease caused by the genus Brucella ; traditionally bovines are host to B. abortus and B. canis is associated with canine brucellosis. Brucellosis as a zoonosis poses serious human health hazards worldwide6,11,13. While some countries have eliminated or substantially reduced the disease by extensive eradication programmes, it remains endemic in many areas of the world, including Nigeria5, 16. The economic burden associated with brucellosis is substantial, mainly the result of abortion or infertility, and the costs of attaining and maintaining a disease-free status.

Various serological studies have documented the prevalence of brucellosis in livestock in Nigeria, with rates falling between 0.2 % and 79.7 %5,8,12. The same cannot be said of dogs, because of limited studies in the country. However, the isolation of B. canis from infected dogs has been reported14and serological reactions to B. abortus and B. canis documented1,15. The disease is insidious and many dogs are asymptomatic9. Infected dogs shed the organisms via urine, vaginal secretions, ejaculates, aborted foetuses and faeces4.

The increase in dog ownership in Nigeria is associated with some risk factors that render them vulnerable to brucellosis. Firstly, many exotic breeds are imported that are not screened before entry into the country. Secondly, some household dogs are fed with foetuses from cows and remnants from slaughtered cattle with a history of bovine brucellosis from abattoirs5. In addition to these factors, some household dogs roam around freely, placing them at greater risk of exposure to brucellosis. Reports have shown that infection with B. abortus last for up to 42 days after abortion or parturition in vaginal discharges of infected cows7.

Given the increase in ownership and associated risk factors in Nigeria, coupled with scanty information about brucellosis in dogs, we conducted a small study to determine whether dogs were likely to have antibodies to B. abortus and B. canis. This comprised 366 household dogs in Lagos and Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria. Samples were collected from dogs brought in for routine physical examination, vaccination and routine complaints over a period of 4 months from 5 veterinary clinics, 3 of which were in Lagos and 2 in Ibadan. The dogs were identified on the basis of breed, sex, age, history of abortion, consumption of foetuses, number of dogs in the household and cohabitation with other animals. The assays were performed using antigens prepared from B. abortus S99 and B. canis RM6/66 on each of the samples according to previously described methods2,10.

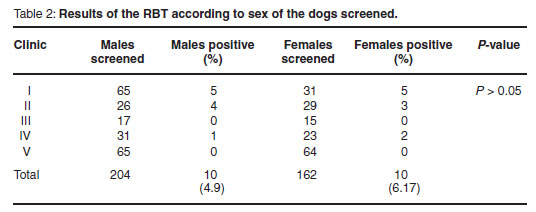

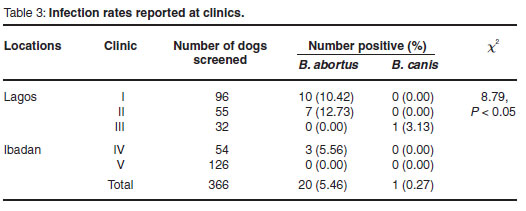

In all, 204 males and 162 females of different breeds and ages (median age 2.1 years) were screened. Serum samples from 20 animals (5.46 %) were positive for B. abortus by RBT and 1 (0.27 %) for B. canis by RSA. Of 36 dogs with a history of being fed foetuses from slaughtered cows, 11 (30.6 %) were positive for B. abortus by RBT. Adults (>1 year) and females were the most affected (Tables 1, 2), while the Alsatian breed yielded most positives (55 % = 11/20). A higher seropositive rate, which was significantly different from the rates at clinics in Ibadan, was recorded in Lagos (χ2= 8.79, P < 0.05) (Table 3).

The results of our study are in agreement with the reports of other workers1,3,15,17, who also demonstrated the presence of B. abortus agglutinins in dog sera using RBT. The higher prevalence of 5.46 % recorded by RBT compared to 0.27 % (only 1 animal) by RSA could be attributed to the practice of feeding dogs with foetuses from slaughtered cows or meat at abattoirs as the prevalence of brucellosis is 6 % in cattle in Nigeria5.

Although not conclusive, our data suggest that young adult dogs (<1 year ) are most affected (Table 1). This is corroborated by a report of higher rates in this age group1and a study that suggested that Brucella infection in dogs is age-dependent15. In addition, we recorded higher prevalences in females (Table 2) but in another study a slightly higher rate in males (29.6 %) than in females (26.7 %) was recorded1. A contributing factor to higher rates in females could be that a single male dog, if infected and used to mate with several females, can transmit the infection via infected semen. Most of the RBT-positive dogs in our study were Alsatians (55 % = 11/20). Although some authors have suggested that infection is breed-dependent15, our finding may be related to the fact that Alsatians constituted the dominant breed in the population sampled (50.55 % = 185/366). Finally, when the dogs in the 2 cities were compared, a significantly (χ2=8.79, P < 0.05) higher seropositive rate was recorded in Lagos (Table 3). This may be attributable to the feeding of dogs with abattoir foetuses in Lagos, a practice that is less common in Ibadan.

From an economic and public health point of view, brucellosis constitutes a threat to dog breeding in Nigeria, along with possible zoonotic implications. The dogs in our study were kept either as companion animals or as guard dogs. Regular contact with people increases the risk of brucellosis transmission to humans.

The findings of this study should, however, be viewed in the light of its limitations. The sample size was small and the study was carried out in a restricted part of the country, hence the results may not be a reflection of the situation in Nigeria as a whole. Clinical details of the dogs sampled were scanty, therefore limited conclusions could be drawn. The serological tests used were inconclusive in the sense that there was no bacteriological confirmation of cases that were serologically positive. The only reported B. canis isolation in dogs in Nigeria to date was due to the importation of dogs14, and it is therefore possible that the single RSA-seropositive result reflects a cross-reaction with other bacteria and not B. canis.

In spite of these limitations our findings are in general agreement with those of other workers1,3,15,17. Further studies are needed to provide a more detailed insight into the epidemiology of brucellosis (both B. abortus and B. canis ) in dogs in Nigeria. Such studies should include samples for bacteriology as well as serology from dogs that are not kept as 'household' (i.e. kennel, stray and rural dogs) given the far-reaching public health implications of this problem in humans.

REFERENCES

1. Adesiyun A A, Abdullahi S U, Adeyanju J B 1986 Prevalence of Brucella abortus and Brucella canis antibodies in dogs in Nigeria. Journal of Small Animal Practice 27: 31-37. [ Links ]

2. Alton G G, Jones LM, AngusRD,Verger JM 1988 Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Paris [ Links ]

3. Baek B K, Lim CW, RahmanMS, Kim C-H, Oluoch A, Kakoma I 2003 Brucella abortus infection in indigenous Korean dogs. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 67: 312-314 [ Links ]

4. Brooks W C 2006 Brucellosis in dogs.Veterinary Information Network Inc. Online at: http://www.VeterinaryPartner.com (accessed June 2008) [ Links ]

5. Cadmus, S I B, Adesokan H K, Adedokun B O, Stack J A 2010 Seroprevalence of bovine brucellosis in trade cattle slaughtered in Ibadan, Nigeria, from 2004-2006. Journal of South Africa Veterinary Association 81: 50-53 [ Links ]

6. Cadmus S I B, Ijagbone I F, Oputa H E, Adesokan H K, Stack J A 2006 Serological survey of brucellosis in livestock animals and workers in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research 9: 163-168 [ Links ]

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2007 Brucellosis. Online at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/brucellosis_t.htm (accessed May 2009) [ Links ]

8. Esuruoso G O 1974 Bovine brucellosis in Nigeria. Veterinary Record 95: 54. [ Links ]

9. Ewalt D R, Bricker B J 2000 Validation of the abbreviated Brucella AMOS PCR as a rapid screening method for differentiation of Brucella abortus field strain isolates and the vaccine strains, 19 and RB51. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 38: 3085-3086 [ Links ]

10. George L W 1978 Development of a RB stained plate test antigen for the rapid diagnosis of Brucellosis infection. Cornell Veterinary Journal 68: 530-543 [ Links ]

11. Hamidy M E R, Amin A S 2002 Detection of Brucella sp. in the milk of infected cattle, sheep, goats and camels by PCR. Veterinary Journal 163: 299-305 [ Links ]

12. Ishola O O, Ogundipe G A T 2000 Seroprevalence of brucellosis in trade cattle slaughtered in Ibadan, Nigeria. Bulletin of Animal Health and Production in Africa 48: 53-55 [ Links ]

13. Maloney G E, Fraser W R 2004 Brucellosis, Omaha, Nebraska, eMedicine, 2004 Online at: http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic883.htm (accessed 1 October 2006) [ Links ]

14. Okoh A E J, Alexei I, Agbonlahor D E 1978 Brucellosis in dogs in Kano, Nigeria. Tropical Animal Health and Production 10: 219-220 [ Links ]

15. Osinubi M O V, Ajogi I, Ehizibol O D 2004 Brucella abortus agglutinins in dogs in Zaria, Nigeria. Nigerian Veterinary Journal 25: 35-38 [ Links ]

16. Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, Christou L, Tsianos E V 2006 The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet Infectious Diseases 6: 91-99 [ Links ]

17. Sardari K, Kamrani A R, Kazemi K H 2003 The serological survey of Brucella abortus and melitensis in stray dogs in Mashhad, Iran. Proceedings of the 28th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association, Bangkok, Thailand, 24-27 October 2003. Online at: http://www.vin.com/proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2003&Category=&PID=6791&O=Generic [ Links ]

Received: June 2010.

Accepted: February 2011.

* Author for correspondence. E-mail: sibcadmus@yahoo.com