Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Journal of the South African Veterinary Association

versión On-line ISSN 2224-9435

versión impresa ISSN 1019-9128

J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. vol.81 no.2 Pretoria ene. 2010

SHORT COMMUNICATION KORT BERIG

Yolk coelomitis in a white-throated monitor lizard (Varanus albigularis)

B R Gardner*; M G Barrows

Johannesburg Zoo Veterinary Hospital, Private Bag X13, Parkview, 2122 South Africa

ABSTRACT

Yolk coelomitis as a result of pre-ovulatory follicular stasis is a common disorder in captive reptiles, especially in captive lizards of various genera. The clinical signs are generally fairly non-specific and diagnosis is based on clinical signs together with most of the common diagnostic modalities. The condition is most likely a husbandry and environment-related reproductive disorder. It has not been reported in wild free-living specimens. This report describes the clinical presentation and post mortem lesions in a white-throated monitor lizard that died during treatment for non-specific clinical signs related to a severe yolk coelomitis.

Keywords: constipation, follicular stasis, white-throated monitor lizard, Varanus albigularis, yolk coelomitis.

INTRODUCTION

The white-throated monitor lizard Varanus albigularis, also known as the rock monitor or leguaan, is the second largest lizard found in Africa after the Nile monitor, reaching up to2min length. Yolk coelomitis, usually following follicular stasis (or pre-ovulatory egg binding), is common in many reptile species, causing disease and very often death2,3,5,7,8. It affects sexually mature females2,3,5,8 and causes varied, non-specific clinical signs1-3,5-8. The most common clinical signs are lethargy1-3,5-8, anorexia1-3,5-7 cutaneous discoloration8 and coelomic effusion or distension1-3,6-8. Clinical diagnosis is difficult3,8. Little is known about the aetiology of the condition and multiple factors are currently thought to be involved2,3,8. Husbandry1-3,5-8, including poor diet3, lack of hibernation3, lack of a substrate suitable for oviposition, lack of male stimulation, and poor temperature and humidity control, amongst others, have been implicated in this condition. The pathophysiology is also not completely understood. Yolk coelomitis can present prior to, during and after ovulation. In pre-ovulatory follicular stasis atretic follicles are either reabsorbed or they leak yolk into the coelomic cavity. The yolk is then reabsorbed from the coelomic cavity8. Vitellin is an irritant and can cause a massive sterile inflammatory response3,8. In snakes commensal gastrointestinal Salmonella species can cause a very mild bacteraemia during vitellogenesis, inoculating the follicles with potential pathogens that could spread into the coelom3. Various pathological manifestations have been seen and associated with the condition.

CASE HISTORY

A 3.2 kg sexually mature adult female white-throated monitor lizard (Varanus albigularis) was presented to the Johannesburg Zoo Veterinary Hospital from the zoo collection. She had previously suffered from dysecdysis and had a history of poor thrift. The presenting complaint was anorexia of 2-week duration, lethargy and coelomic distension. There was no history of successful breeding or recent reproductive behaviour. The monitor was maintained on a river sand substrate and was fed on a special feeding slab to avoid ingestion of substrate. Her body condition was poor, and there was moderate coelomic distension, although no eggs or follicles were palpable. There was some discolouration of the integument and dysecdysis. Generally lizards do shed the skin in pieces2,3, but this female had been shedding for an extended period. She was moderately dehydrated with a flattened body profile. On dorso-ventral whole body radiographs a large amount of gritty, opaque mineral material was visible compacted into the caudal intestinal tract causing colonic distension. A possible substrate-related impaction was first suspected. No follicles were visible on the radiographs. The monitor was treated with warmed intracoelomic lactated Ringers solution at a dose of 15 m /kg q 24 h, lactulose (Lacson® 3.3 g/mℓ, Aspen) at a dose of 0.5 mℓ /kg PO q 24 h, Lenolax Paediatric® enemas daily and daily lukewarm water soaks. After 4 days there was no response to treatment. The monitor was producing urates but no faecal material had been passed. She became more depressed and the mucous membranes became paler. Surgical intervention was planned but the patient died on the same day.

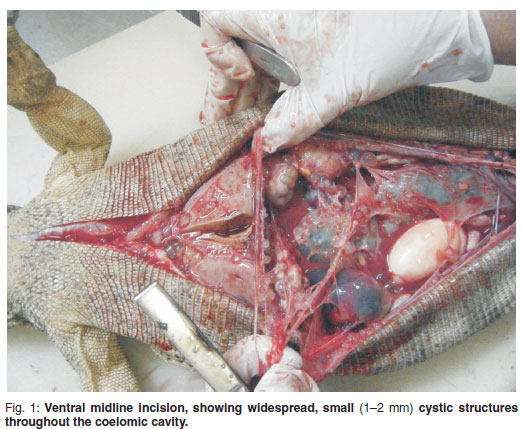

A post mortem examination was performed. Macroscopically there was severe generalized yolk coelomitis with a haemorrhagic purulent fluid distributed throughout the entire coelomic cavity. The liver, the entire length of the intestines, the reproductive organs and entire coelomic mesothelium were covered with multiple small 1-2 mm cystic structures containing clear fluid (Fig. 1). The ovaries were hard with large inspissated necrotic cores. Inspissated proteinaceous material in reptiles usually is fibrin, the common product of inflammation4. The liver was pale and friable. The colon was moderately distended with hard, dry sand-like material. There were multiple adhesions between the liver, gastrointestinal tract, oviducts and coelomic membrane. Samples for histopathology were collected in 10 % buffered formalin. Histopathological lesions included multifocal myocardial calcification, multiple ovarian cysts containing inspissated proteinaceous material, multifocal fibrin thrombi in the capillaries of the renal glomeruli, multifocal fibrin thrombi in the hepatic sinusoids with severe vacuolar hepatocyte degeneration, chronic granulomatous coelomitis with proteinaceous yolk accumulations in the pulmonary blood vessels and granulomatous serositis of the entire length of the intestines. All the lesions support a diagnosis of severe yolk coelomitis. The hepatic changes are indicative of prolonged starvation.

DISCUSSION

This condition is frequently diagnosed too late, either when the animals are moribund or as a post mortem diagnosis. In this case, diagnosis was only made post mortem. In Fiji Island banded iguanas with yolk coelomitis a histopathological relationship between the granulosa cells of the vitellogenic follicles and the reactive mesothelium has been reported8.In a green iguana bilateral cystic structures arising from the ovarian surface epithelium, with extensive metastasis along the serosa of the majority of coelomic viscera, have also been reported9. This was the result of a primary ovarian cystadenocarcinoma, but the lesions were not dissimilar to those observed in the whitethroated monitor. Both these cases have similar lesions to those encountered in the white-throated monitor, with a similar distribution of lesions. However, histologically there was no evidence of reactive mesothelium resembling ovarian granulosa cells in the present case.

A combination of clinical signs, gentle abdominal palpation, radiography, ultrasound, and biochemistry can be used to diagnose follicular stasis. Biochemistry might show elevated triglycerides3, hypercalcaemia3,5,8, hyperphosphataemia3,5,8 and hyperalbuminaemia3. These changes are associated with vitellogenesis3. Uric acid may also be increased due to dehydration secondary to the anorexia8. Follicles can be seen more easily on radiographs if the coelomic cavity is injected with air.

Ovariosalpingectomy or ovariectomy is the best method of preventing yolk coelomitis and the mainstay of treatment. The condition has not been diagnosed in free living reptiles and the aetiology seems to be multi-factorial. Providing optimal species-specific husbandry should allow for normal reproductive behaviour and possibly decrease the incidence of yolk coelomitis in captive reptile populations. Copious coelomic lavage to remove irritant vitellin and parenteral antibiotics, preferably selected according to antimicrobial sensitivity, should be used to increase post-surgical survival2,5.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors are grateful to Dr Thelma Meiring from Golden Vetpath for performing the histopathology examination on the submitted samples.

REFERENCES

1. Arenbjerg J, Ruelokhe M L, Aalbek B 2008 Infectious salpingitis and coelomitis in a spiny-tailed monitor lizard. Exotic DVM 4.2: 17-19 [ Links ]

2. Bennet R A, Mader D R 2006 Cloacal prolapse. In: Reptile medicine and surgery (2nd edn). Saunders/Elsevier, St Louis: 751-755 [ Links ]

3. Girling S J, Raiti P 2004 BSAVA manual of reptiles (2nd edn). BSAVA publications, Woodrow House, England [ Links ]

4. Huchzermeyer F W, Cooper J E 2000 Fibricess, not abscess, resulting from a localized inflammatory response to infection in reptiles and birds. Veterinary Record 147: 517-518 [ Links ]

5. Jacobson E R 2003 Biology, husbandry and medicine of the green iguana (1st edn). Krieger Publishing, Florida [ Links ]

6. Juan-Sallés C, Garner M M, Monreal T, Burgos-Rodriguez A G 2008 Ovarian torsion in a green iguana, Iguana iguana, and a rhinoceros iguana, Cyclura cornuta. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 18: 14-17 [ Links ]

7. Scheelings T F 2008 Pre-ovulatory follicular stasis in a yellow-spotted monitor, Varanus panoptes panoptes. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 18: 18-20 [ Links ]

8. Stacy B A, Howard L, Kinkaid J, Vidal J D, Papendick R 2008 Yolk coelomitis in Fiji Island banded iguanas. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 39: 161-169 [ Links ]

9. Stacy B A, Vidal J D, Osofsky A, Terio K, Koski M, de CockHEV 2004 Ovarian papillary cystadenocarcinoma in a green iguana (Iguana iguana). Journal of Comparative Pathology 130: 223-228 [ Links ]

Received: October 2009.

Accepted: April 2010.

* Author for correspondence. E-mail: trogrendrag@gmail.com