Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versión On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versión impresa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.49 no.3 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/14107

ARTICLE

"Medical Practice between Two Worlds": The Work of Samuel Gurney in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1903- 1924

Clement Masakure

University of the Free State, South Africa masakurec@ufs.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3683-9417

ABSTRACT

This article examines the experiences of the pioneer Methodist medical missionary, Dr Samuel Gurney, who worked for the American Methodist Episcopal Church (United Methodist Church) in Colonial Zimbabwe from 1903 to 1924. Gurney worked with an African assistant named Mr Job Tsiga. Based on archival and secondary sources and informed by the colonial encounter paradigm, this article notes the complex and contested nature of medical missionary work. Punctuated by rejections, acceptances and negotiations, their work demonstrates the fortunes of early medical missionaries. Medical missionaries, such as Gurney, laid the foundation for the present-day Western healthcare system. In the process, they set in motion the terms of debates over biomedicine, Western health practices, and healing amongst Africans in rural areas.

Keywords: Samuel Gurney; Job Tsiga; medical missions; United Methodist Church; Colonial Zimbabwe

Introduction

The extant literature on the history of Christian missions in early Colonial Zimbabwe has primarily examined missionaries and their work in converting Africans (see, e.g., Goto 1994; 2001; Mujere 2013; Zvobgo 1996). While there have been some discussions on medical missionaries and the healing services they offered, this discussion has been a broad overview of the mission stations established in the early colonial period (see, e.g., Gelfand 1988; Zvobgo 1996). A sustained discussion of missionary doctors and their assistants in establishing mission stations via their medical work has been missing from the literature. Yet, according to Goto (1994, 2), "Gurney pretty much single-handedly laid the foundation for the future development of the Methodist Episcopal church in the northern parts of Rhodesia". This article, therefore, examines the experiences and the work of the American pioneer Methodist missionary and medical doctor, Dr Samuel Gurney, assisted by Mr Job Tsiga, from around 1903 to 1924. Informed by the colonial encounter paradigm, the article also notes the complex and contested nature of medical missionary work. Gurney and Tsiga's work was wrought with rejections, acceptances and negotiations (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2009, 39). Further, I argue that medical missionaries and their assistants, through their work, were as crucial as other missionaries in evangelisation in Central Africa. Gurney and Tsiga were involved in "medical practice between two worlds"1 bridging indigenous and Western therapeutic practices.

In examining the experiences and work of medical missionaries, I not only engage with the literature on missionaries in Colonial Zimbabwe, but also the broader literature on medical missions in Central and Southern Africa. Scholars, such as Vaughan (1991), Ranger (1992), and Landau (1995), for example, have examined the centrality of medical missionaries to the mission project. In their respective works, while they do make a critique of medical missions, nonetheless they noted how biomedical practices were intimately tied to the evangelisation project. As Vaughan (1991, 56) notes, missionaries in the late 19th century and early 20th century "combined, sometimes uneasily, a belief in the powers of biomedicine with the conviction that those 'called' to the medical profession were servants of the 'Great Healer' of souls". Missionaries followed David Livingstone's path not to miss "the opportunity which the bed of sickness presents by saying a few kind words in a natural and respectful manner and imitate as far as you can the conduct of the Great Physician, whose followers we profess to be" (Vaughan 1991, 58). The article, therefore, builds on this literature in my examination of Gurney and Tsiga's experiences in Colonial Zimbabwe.2 Unlike the extant literature, which in most cases examine the connections between medical work and evangelisation through an analysis of entire missions, I focus on a medical missionary and his assistant, and explore their work as a window into examining the fortunes of missionaries in Central Africa.3 Examining their experiences enables readers to peer into early mission stations and expose the tensions at such stations. Furthermore, examination of their work introduces readers to early mission hospitals where medical encounters occurred and exposes medical missionaries' frustrations. In addition, an analysis of their experiences allows readers to appreciate the innovative ways medical missionaries provided medical care to Africans on the fringes of the colonial state.

Brief Biographical Sketch of Gurney

Samuel Gurney4 was born on 3 September 1860, in Long Branch, New Jersey, United States (US). A graduate of Drew Theological College, Gurney began his ministry serving pastorates on Long Island and Connecticut in the 1890s. In 1902, he was appointed by Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell as a medical and evangelistic missionary at Old Mutare (Zvobgo 1996, 72). In the following years, Gurney opened Murewa Mission (Zvobgo 1996, 205) and was among the missionaries who opened Nyadiri Mission in 1923 (Goto 1994, 19). Gurney passed away on 3 August 1924 in Salisbury, then Southern Rhodesia. It is not clear what the exact cause of his death was, but the records indicate that he had heart problems and internal pains and had undergone surgery in 1924, though they do not disclose the nature of the operation.5

Gurney entered the "field" at the time the colonial government was in the process of setting up the conditions for medical practice. During the early colonial period, for fear of unqualified and at times quack doctors and the need to standardise medical practice in the new colony, those who wanted to practise were expected to possess a medical certificate from a recognised British institution. The Liverpool and London schools of Tropical Medicine were at the top of the list, but colonial medical officials also accepted medical certificates from any university or college in the Commonwealth. In Southern Africa, the Licence to Practice was granted by the Cape Colonial Medical Council.6 At times, these conditions were suspended depending on the circumstances. There were two cases of medical doctors who practised medicine in the early years of colonialism without a certificate from a British college, namely Gurney and Dr Thompson, who was based at Mt Selinda Mission in the South-Eastern districts of the colony. The two were allowed to practise probably because they were the first doctors to provide medical services to Africans at a time when the government was more concerned with white settlers' health (Gelfand 1976, 17; Masakure 2020, 250). In 1923, Gurney reminisced that: "These exceptions are (were) probably due to the fact that we were registered long ago before the laws on this subject were rigidly enforced".7 Whatever the case, it is clear that in the early days of colonial rule, government policies were not carried out to their full conclusions. They were at times ignored and changed depending on circumstances on the ground. By the beginning of the First World War, the door for medical doctors with American educational qualifications was closed. Even so, Gurney was allowed to continue practising medicine, treating black and white patients, and would receive high praise for his work during the influenza pandemic.

The Tension of the Mission: The Disharmony between Gurney and Hartzell

Studies on missionaries have emphasised the tensions between missionaries and African communities they hoped to convert (see, e.g., Landau 1995; Ranger 1992; Zvobgo 1996). However, as with any other community, mission stations were not free from tensions and disagreements between missionaries. At Old Mutare, the dispute between Gurney and Hartzell, which exposed what I call "the tension of the mission", almost denied Gurney the opportunity to return to Colonial Zimbabwe from his furlough in the US. The day before Gurney left for the US, Hartzell told Gurney that his work at the mission was over.8 Hartzell claimed that he wanted to discontinue the medical work due to limited financial resources. According to Gurney, Hartzell reached this conclusion as he saw medical work to be of lesser significance than other branches of missionary work. Gurney was clear, Hartzell had told him that his work was being discontinued because of "the greater importance of industrial work, the greater willingness of the people to give money for that work and the impossibility of obtaining enough money for both".9 Surprised, Gurney conveyed the message to other missionaries. During the Finance Committee meeting on the same day, the members of the committee remonstrated against the decision. Hartzell retracted his decision, claiming to have been misunderstood.10 After the meeting, Gurney approached several people to correct "the mistake (?)".11 However, Gurney believed that Hartzell's initial statement towards him represented his feelings and purpose.12 Hartzell also approached Gurney in private, asking him to ignore what he had said before: "for when I was talking to you I had one of my terrific headaches on".13 The following day, Hartzell reiterated his desire for Gurney to return to Old Mutare. Gurney suggested that this might have been due to the rising dissatisfaction amongst other missionaries and other people in the town of Mutare, who were worried by the possibility that Gurney would not return.14

Eriksson (1963, 27) has suggested that Gurney was almost denied the opportunity to return to the mission station after a furlough due to "his presuming peculiarities of his temperament that he had displayed, and also because his wife refused to come out [sic] again". A graduate nurse, Mrs Gurney refused to return mainly due to the general conditions of affairs at Old Mutare. When Gurney and his wife were offered their positions at Old Mutare, they expected to oversee the running of the hospital. However, when they arrived, they "found that there was no hospital and apparently no intention of having one".15 On the whole, Mrs Gurney was unhappy during her sojourn in Central Africa. This is not surprising, since as pioneer missionaries, they had to forgo many comforts to get missionary work going. For some like Mrs Gurney, this was too much a sacrifice. Hence her refusal to return to Old Mutare upset Hartzell and he decided to use this as an excuse to prevent Gurney from coming back.

The issue of temperament can be contested. In fact, I argue that it was not about Gurney's temperament, but more about his critique of how the mission station was administered. Gurney criticised the mission administration because "it was out of harmony with the laws and usages of our church, and that his (Hartzell) representations of the work, as published in our church papers, are out of harmony with facts".16 Records consulted are silent on the dissonance between the administration and the laws and usages of the church. What is clear is that Hartzell, in his reports to the mother church, painted a positive picture of the work at the mission station. On the contrary, missionaries like Gurney relayed information that was at variance to what the administration provided. Indeed, on their first meeting in New York during Gurney's furlough, Hartzell accused Gurney of sending information to the Board of Managers without his knowledge and approval. This was the main reason why he had decided to terminate Gurney's medical work: "When you (Gurney) told me at Umtali that you assumed your full share of responsibility for that paper that was sent to New York I made up my mind that you could not come back".17 Gurney defended his stance. His decision to provide information without the administration's approval had nothing to do with him having a personal vendetta against Hartzell.18 However, "his [Hartzell's] methods have been such as to forfeit the confidence of all missionaries who have worked under him in Eastern Africa".19 While other missionaries opted to be silent on what was going on at the mission, Gurney argued that it was his duty to inform the mother church of the exact conditions on the ground. As he argued, "We (Gurney and others who supported him) believe that further silence is not justifiable and that it is imperative the Board of Managers shall no longer be kept in the dark to the real situation".20 Gurney was saved by other missionaries in the Eastern African circuit who supported his stance. Missionaries, such as Rev. R. Wodehouse, Rev. J. E. Ferris and Rev. E. H. Greely, sent Gurney letters of support and urged him "not to give up Africa". 21 Even other whites living within the vicinity of the mission stations supported Gurney. One mine proprietor, T. D. Maclene, urged Gurney to come back as he had great "appreciation of the good work you have done here". 22 Buoyed by their support, Gurney returned from his furlough and went on to establish medical missions for the Methodist Episcopal Church. This incident is a reminder of how at times mission stations were fraught with tensions and disagreements amongst missionaries.

Gurney's Medical Work

According to Hardiman (2006, 6), missionaries saw themselves as "providing a ray of hope in a surrounding darkness". For missionaries, this could be done through healing. Indeed, as Vaughan (quoted in Hardiman 2006, 6) argues, for many a missionary, mission medicine "was part of a programme of social and moral engineering through which Africa would be saved". In the case of the Methodist missions under discussion, a reading of the reports shows how this racist and paternalistic trope was emphasised time after time. As one missionary reported in 1909, a substantial time of medical missions was spent looking after the "bodily infirmities of these unfortunate and ignorant brothers of darkness and sin" (Goto 2001, 53).

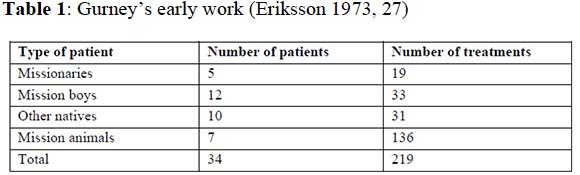

The social and moral engineering project - via medical men such as Gurney, rested on the availability of enough resources. In his appointment letter, Hartzell promised Gurney the necessary material to carry out his work. Not only would Gurney earn a modest sum of $1000.00 per annum, but he would also be provided for his work, "such outfit with medical instruments and supplies as the funds of the society will enable them to secure".23 Gurney had to act as a physician for missionaries, but most importantly he had to conduct medical work amongst Africans.24 Table 1 shows his early work in 1903.

At times inadequate resources affected the medical work. As early as 1904, Gurney articulated this major drawback in a letter to Hartzell. Not only was he disappointed by the failure of the church to furnish him with a hospital to practise his craft, but the relative lack of resources circumscribed his medical work.25 The case of a young man who was suffering from eye problems immediately comes to mind. He wrote in disappointment: "a young man, about 20, almost totally blind, home alone at Madedzura's about fifty miles ... eyes not inflamed ... I feel it is the nerve ... is at fault ... I have not the instruments for diagnosing and healing such cases".26 Fifteen years later, Gurney complained again concerning the relative inadequate resources and how this hampered his medical work. He wrote: "as the present condition of our mission does not present much of an opportunity for the work of a Medical Director ... sickness among the people has no check".27 The paucity of resources also made it difficult to attract helpers, especially nurses from the US who were willing to come and work at mission stations in Colonial Zimbabwe. As he noted in his report on the dispensary at Old Mutare, in most cases, medical work was at times left to the missionaries who did not have medical training and "as they have not understood the diseases they were treating nor the medicines used in their treatment and the results have not been very satisfactory".28 The so-called hospital at Old Mutare in the immediate post First World War era was a small brick building that consisted of small rooms that were poorly lit. Each of the rooms had a small window "large enough to admit some rays of light but not admitting light enough to permit proper examination of patients much less the proper treatment".29 It was, according to Gurney, "unsuited for the work required".30

Even though resources were limited, there were two major surgical operations that Gurney conducted which made him a household name within the Methodist community in Colonial Zimbabwe and abroad. The first took place three months after his arrival at Old Mutare Mission in 1903. According to one of the missionaries - Mrs H. Springer -Gurney:

had been walking on the path past a village five miles from Old Umtali Mission when he heard moans in a lonely hut in the fields. Going to see what was the cause of the crying, he found Shakeni's mother [Hamuchandiwoni] in dire distress. She had a large tumour which had to be operated upon and removed at once to save her life. Her family had taken her out to the fields to die, uncared for and unattended ... She had been there in the hut for nearly a week. The family had brought food and water which they had placed near the hut but none of them had dared to go near her. She had to crawl on her hands and knees in the dirt to get food and to care for herself. The "hospital" was an old ant eaten building and the doctor feared to perform such an operation in a place that could not be made antiseptic. So he phoned to the Government Doctor asking him to do the work, but he would not. So the doctor called us all in and it was decided that we go ahead. We must have made an amusing sight! I was the only lady missionary at the time and the only person who knew anything about surgical work besides the doctor. But we had to help. The doctor never wasted time lamenting the things he did NOT have, so having nothing else he sterilized five of his own night shirts and we all dressed up in them for the operation. That was 20 years ago and the patient is still alive.31

In 1968, Rev. E. L. Sells re-told the story of the surgery as "the major event that contributed the most to the development of Old Umtali (Mission)".32 In Sells' version, it becomes clear that Shakeni's mother, Hamuchandiwoni, came from a village in Chief Chikanga's Chiefdom. In addition, Gurney was not alone, but on that Sunday, he was with another missionary, Rev. Greely. When they found Hamuchandiwoni, they went to the next village, and after considerable discussions, they persuaded some of the men in the village to help. They made a stretcher of poles, covered it with an old blanket and carried her to the mission station. With inadequate instruments that included ordinary knives, he operated on her the following day.33

The second major operation took place near what became Murewa Mission. During the harvest season in Murewa District in 1909, a young girl was tossed into the air by an infuriated bull. The girl, Chemhunga, was about ten years old when the incident took place. Chemhunga narrated the events to Sells that she and her friends were playing near a hut, when:

We saw a large bull coming from a distance towards us ... Then the bull came towards us with its head down, bellowing and we all ran for a place of safety. I did not escape, he came directly at me. His sharp horn went through my side and he threw me up in the air. He picked me up on the horns when I came down and he threw me up in the air a second time.34

Chemhunga's mother and brother washed her wound, pushed the intestines in, and sewed it with a bark string and tied a white cloth over it. Her brother, Paul Bere, carried her for about five kilometres to the government office where a messenger, John Mukowero, was sent to call Gurney and his assistant, Tsiga. Chemhunga's narration continues:

Dr. Gurney placed me on a table and after examining the wound, gave me medicine that put me to sleep. Those who saw him opening the large wound said that he pulled the intestines as far as he could, washed them and after replacing them sewed the torn place using some kind of medicine to help it heal.35

The above anecdotes suggest several themes that are significant in analysing the pre-colonial practices of nursing and medical practices, for example, the building of isolation huts and sewing up the wound with a bark string and, of course, the position of missionary medicine in early Colonial Zimbabwe. But most importantly, the stories were narrated in such a manner that rendered these incidences as defining moments in Gurney's efforts at "civilising" Africans through biomedical practices.

Hamuchandiwoni's operation and her recovery were presented as the beginning of Gurney's 25-year career "of healing and preaching the gospel" in Colonial Rhodesia.36Most significant for Old Mutare Mission, the success of the operation was the beginning of a massive campaign in the conversion of Africans living within the vicinity of the mission station. As a sign of gratitude, Hamuchandiwoni brought her daughter, Tsvakeyi, to the mission. Tsvakeyi and a group of other girls were in the first cohort of African female pupils at Old Mutare Mission, and she was to play a critical role there.

It is possible to discern a similar trope with Chemhunga's operation. For Tsiga, the surgery opened space to engage with the locals in the process allowing the evangelisation of the locals and the ability of mission medical team to conduct medical work without hindrance. It must be noted that in 1908, Tsiga and Gurney were tasked with opening a new medical station in the northern parts of the colony. Hence, they moved to Murewa - where the current mission station is located - but they faced hostile chiefs and local leaders. Tsiga was clear, "when we arrived, they (chiefs/leaders) refused to give us a place to live or practice"37. There is no doubt that some chiefs saw the presence of missionaries within their areas of control as highly problematic. The missionaries' presence was considered at times as a nuisance that affected local politics. Others felt that the presence of the missionaries destabilised indigenous social relations, either within families or in the villages. One of these was the paramount Chief Nyajena who objected to the presence of Gurney and Tsiga within his realm. Nyajena's stance did not amuse the Native Commissioner (NC):

In the view of the great service which a medical mission such as Dr Gurney proposes to establish would be to the district, both the natives and to the white population I consider Nyajina's objection should be overruled and a site granted to Dr Gurney without the consent of Nyajina. I may state that in the vicinity of the site chosen by Dr Gurney there are several kraals in which there is great deal of syphilis, and I think Dr Gurney was greatly guided in his selection of a site by the hope of being able to help these unfortunate people, and under the circumstances I consider that the chief is working against the interests of his people.38

The NC was not concerned about evangelisation and the conversion of Africans. He was more worried about the increase in venereal diseases within the area and its impact on the availability of African labour on surrounding farms. An interview was arranged between Nyajena and Gurney, hoping to persuade the chief to allow Gurney to set up a mission station in his area. However, he could not be prevailed upon to alter his decision as he refused to depart from his original resolution of "no missions".39 Fearful that the missionaries would influence his people to abandon indigenous religious practices, as had happened with the Catholics at the Jesuit mission of Chishawasha, he was steadfast in his refusal of having a mission station in his territory. As Nyajena remarked: "The government can take all of my young men and make them work and I will be pleased but I want no mission to take away my young men".40 At Chishawasha, they "have the kraals there for young men ... (The young men say) government is my father and I want no other". 41 Nyajena's stance can also be viewed as part of the struggle to control the young men and the resources that came from the fruits of their labour. For him, the introduction of a third centre of power, the missionaries, would gradually erode his authority. While the NC tried to reason with Nyajena, he refused to budge. The government, nonetheless, promised to give Gurney the land to establish a mission station.

The missionaries used any opportunity available to express their frustration with the slow pace of conversions and the hostilities they faced. Gurney reported of the slow progress at the 1910 Conference thus:

It is a matter of profound regret to the missionary that so little has been accomplished. Others come up to the conference reporting many precious sheaves which they have gathered from the field in which they have labored, but the medical missionary can give no such glowing report. He can only tell of the uprooting of noxious weeds, the blasting of rocks and the preparation of the soil for seed. The harvest is as yet in the future. (Goto 1994, 18)

Chemhunga's operation cited earlier was considered by many within the Methodist circles to be a key turning point for Gurney and Tsiga. After the operation, as Tsiga narrated: "I was asked to start a school ... this is where Murewa Mission stands".42 Tsiga was very clear on the overall impact of the surgical operation. Not only did Chemhunga's people convert to Christianity, but the operation also opened space for Gurney's medical work to be accepted by Nyajena and his people. Using discourses couched in Christian missionary arrogance, the operation, as Tsiga stated, was a "triumph over darkness and barbarity".43 By 1921, church membership in Murewa District numbered 148 (Goto 1994, 20) and the numbers continued to increase.

There is no doubt that the above narratives are problematic. They were recorded and written for a particular audience - the missionaries and the congregants in the Global North who financed church operations. As part of missionary propaganda, meant for an audience in Europe and North America, such narratives produced images of white medical personnel who overcame obstacles in the so-called "dark continent" (Vaughan 1991, 155-177). Sells' 1968 version in Umbowo, the church run newsletter, was also written for a home audience that was beginning to take over the running of mission stations from the early missionaries in the 1960s. Constructed in a triumphalist missionary discourse, they exhibited missionaries' and their congregants' arrogance over the local cultures. Dismissive of alternative therapeutic systems, they were teleological - giving an impression that there was a direct correlation between a particular medical operation and the success in establishing medical missions. Problematic as they are - the narratives open space to peer into the early experiences of mission doctors who practised medicine on the fringes of the mission stations and the colonial health system. They give readers glimpses into the frustrations of men such as Gurney and Tsiga. As will be shown later, they also allow readers to examine how such men (and women) creatively adapted to their situation in a challenging environment.

Innovation at the Fringes of a Rudimentary Colonial Health System: The Case of Absent Treatment

Considering the limited resources regarding personnel and finances, Gurney had to improvise and be innovative in the provision of medical services to the Africans. While he had one trusted assistant, Tsiga, he also relied on a host of African converts to provide medicine in the outlying districts of the mission stations. Some of the medical assistants at Old Mutare travelled from village to village conducting first aid work. While this was in line with African conceptual ideas of healing - where at times the n'anga (traditional healer) visits the patient to administer medicine - the missionaries encouraged this due to the unavailability of enough resources, the problem of distance and of course, as a way of proselytising. In her 1926 report, a nurse at Old Mutare Mission - Miss Ellen Bjorklund - not only highlighted the problem of "pernicious malaria" in the area, but also praised one of the medical assistants for his "great talent in the care of the sick".44According to Bjorklund, David Sakutomba

Her Intestines. Rhodesia - the Methodist Church - Yesterday and Today. n.d.

has been walking from kraal to kraal (village to village) with a first aid box doing first aid work and preaching the gospel. This work has been much appreciated by our native friends, and many in this way have been brought under the influence of the word of God.45

The most innovative medical practice was what Gurney called "absent treatment", which meant family members were involved in the diagnosis and treatment of sick relatives. According to Gurney:

People come in the interest of others in their families or villages who are sick and ask for help. It is very difficult to know what to do with such cases for usually the messenger is unable to give those details of a condition that are necessary for a reliable diagnosis. Usually I get all the information possible and the advice treatment as best I can.46

It must be noted that Gurney was never comfortable with this system as it had its limits. He wrote in the 1923 report, "Long ago I lost confidence in this sort of medical work for so often both diagnosis and treatment are wrong and we have made the patient worse rather than better".47

It is not clear from the records I consulted for how long Gurney used this system. However, what can be gleaned from the sources is that by 1923, there were major problems with this kind of medical intervention. Besides being expensive on the part of the mission stations, there were huge drawbacks in relying on Africans who came on behalf of their relatives to request medicine. As Gurney argued:

With but a few exceptions natives cannot be relied upon to give medicine according to directions. To most of them medicine is only another sort of charms and if a little will do good why not give it all at once and so end the matter. Sometimes it does end the whole matter for I have known at least two cases of death by improper use of medicines that were taken to the kraal by natives.48

He also questioned the so-called the improper diagnosis made by Africans:

Natives cannot describe conditions with sufficient accuracy to enable a correct diagnosis and so in many cases the wrong medicine will be sent at a risk of the patient's health and the loss of our mission funds. I have tested the ability of the natives to describe the conditions in scores of cases at the dispensary and usually the diagnosis made at their statement are reversed on the examination of patients.49

There is indeed a high possibility that there was miscommunication regarding the exact nature of the diseases. The problem of Africans' alleged inability to describe afflictions according to Western standards continued well into the late 1970s (Munyaradzi and Muronda 1979, 104-107; Kavumbura and Mossop 1980, 111-114). To be sure, the problem was not Africans' so-called incapacity to explain affliction. Rather, the predicament rested on cultural differences and the language employed in explaining illness and disease causation. What is significant to highlight is that even though "absent treatment" had its own limits, an appreciation of this form of medical practice allows readers to analyse how medical practitioners, such as Gurney, in the early years of colonial rule, creatively adapted to their situation in their efforts to provide services to Africans in rural areas.

Conclusion

Gurney passed away in 1924. Without a shadow of a doubt, Gurney's death robbed the Methodist church of a dedicated missionary and the medical fraternity of a pioneer medical doctor in Colonial Zimbabwe. In one of the publications by the Methodist church, the editorial was clear, the Methodists had to be reminded of Gurney - "Lest we forget". For the Methodists, Gurney's work was central to establishing mission centres and the evangelisation project. For the state, the work of missionary doctors, such as Gurney, even though they did not possess medical certificates from the United Kingdom or the Commonwealth, laid the foundation for the future Western medical system in the colony. On the fringes of the colonial health system, Gurney's experiences were punctuated by rejections, acceptances and negotiations. An examination of such experiences provides an entry point into analysing medical missions and the provision of health services in the early colonial period. They also broaden the understanding of the innovation that came with it due to, inter alia, inadequate resources. It must be reiterated that this would have been impossible without the assistance of a host of African auxiliaries such as Tsiga.

References

Eriksson, K. 1973. A Sketch of the Life and Work of Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell, Missionary Bishop of Africa 1896-1916. Umtali: Rhodesia Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church. [ Links ]

Gelfand, M. 1976. A Service to the Sick: A History of Health Services for Africans in Southern Rhodesia (1890-1953). Gwelo: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Gelfand, M. 1988. Godly Medicine in Zimbabwe: A History of its Medical Missions. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Goto, N. 1994. "A Great Central Mission: The Legacy of the United Methodist Church in Zimbabwe." Methodist History 33 (1): 14-25. [ Links ]

Goto, N. 2001. African and Western Missionary Partnership in Christian Mission: Rhodesia- Zimbabwe, 1897-1968. Kearney: Morris Publishing. [ Links ]

Hardiman, D., ed. 2006. Healing Bodies, Saving Souls: Medical Missions in Asia and Africa. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789401203630 [ Links ]

Kavumbura, B. J., and R. T. Mossop. 1980. "Attitudes to Illness in Salisbury, 1980." Central African Journal of Medicine 26 (5): 111-114. [ Links ]

Landau, P. 1995. The Realm of the Word: Language, Gender and Christianity in a Southern African Kingdom. Portsmouth: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Masakure, C. 2020. "Government Hospitals as a Microcosm: Integration and Segregation in Salisbury Hospital, Rhodesia, 1890s-1950." In Tracing Hospital Boundaries: Integration and Segregation in Southeastern Europe and beyond, 1050-1970, edited by J. L. Stevens-Crawshaw, I. B. Latin and K. Vongsathorn, 246-269. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004429239013 [ Links ]

Mujere, J. 2013. "African Intermediaries: African Evangelists, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Evangelisation of the Southern Shona in the Late 19th Century." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 39 (2): 133-148. [ Links ]

Munyaradzi, O. M., and C. Muronda. 1979. "Some Attitudes of Patients Discharged from Harare Hospital." Central African Journal of Medicine 25 (5): 104-107. [ Links ]

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2009. "Mapping Cultural Encounters, 1880s-1930s." In Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008, edited by B. Raftopolous and A. Mlambo, 39-74. Harare: Weaver Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvk3gmpr.10 [ Links ]

Ranger, T. O. 1992. "Godly Medicine: The Ambiguities of Medical Mission in Southeastern Tanzania, 1900-1945." In The Social Basis of Health and Healing in Africa, edited by S. Feierman and J. M. Janzen, 256-282. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Vaughan, M. 1991. Curing Their Ills: Colonial Power andAfrican Illness. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [ Links ]

Zvobgo, C. J. M. 1996. A History of Christian Missions in Zimbabwe. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

1 Africa University Archives. 07 B3 F13 (hereafter AUA). E. Sells, Medical Practice between 'Two Worlds': A Woman Tells How Dr. Gurney Put Back Her Intestines. Rhodesia - the Methodist Church - Yesterday and Today. n.d.

2 I have used Post-colonial names in this article: Colonial Zimbabwe (Southern Rhodesia), Salisbury (Harare), Mutare (Umtali), and Old Mutare (Old Umtali).

3 The primary sources consulted are housed at the Africa University Archives, Mutare, Zimbabwe. These are files for the United Methodist Church. I would like to thank the archivist, Mr Shepherd Machuma, for granting me access to the files.

4 It is unfortunate that the records do not provide much information on Mr Job Tsiga except his connections with Dr Samuel Gurney. Hence, this article will focus more on Gurney's work. Perhaps future research will have to make a follow up through extensive interviews on Tsiga and his medical work.

5 AUA. W.W. Reid. Veteran Medical Missionary Passes Away; Rev. Samuel Gurney, MD., of the Rhodesian Conference, Had a True Pioneer Spirit. 1924.

6 AUA. Letter from the Medical Director, Andrew E. Fleming to Samuel Gurney. 12 November 1904.

7 AUA. Samuel Gurney. Report of the Conference Medical Director, Rhodesia Mission Conference Methodist Episcopal Church. June 1923.

8 It is not clear from the records consulted when Samuel Gurney went back to the US for his furlough. However, it must have been within his first five years as a missionary.

9 AUA. Samuel Gurney. Bishop Hartzell's Statements Concerning My Return, 1905.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid. Question mark is in the original document.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid. Gurney quoting Bishop Hartzell.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid. Gurney quoting Bishop Hartzell.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid. Gurney quoting Rev. R. Wodehouse.

22 Ibid. Gurney quoting T. D. Maclene.

23 AUA. Memorandum of Agreement between Bishop Hartzell and Rev. Samuel Gurney and His Wife. 23 December 1902.

24 Ibid.

25 AUA. Samuel Gurney. Diary entry, 6 September 1904.

26 AUA. Samuel Gurney. Diary entry, 24 September 1904.

27 AUA. Samuel Gurney. Medical Report for the Umtali Session Report of the Conference Medical Director, Rhodesia Mission Conference Methodist Episcopal Church. 1919.

28 AUA. Med G 6-15. Samuel Gurney. Write Up on Old Umtali Dispensary. 1921-22.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 AUA. H. Springer, More about Dr Gurney. 1924.

32 AUA. E. Sells. Methodist Pioneers in Rhodesia: Dr Gurney, Hamuchandiwoni and Tsvakeyi. Umbowo. 1968.

33 Ibid.

34 AUA. E. Sells. Medical Practice Between 'Two Worlds': A Woman Tells How Dr. Gurney Put Back Her Intestines. Rhodesia - the Methodist Church - Yesterday and Today. n.d.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 AUA. Miscellaneous Letters and Matters Relating to the Life and Work of Dr. Samul Gurney. Letter from Native Commissioner to Superintendent of Natives, Salisbury. 19 August 1909. I have maintained the colonial spelling "Nyajina" in the long quotation. The current spelling is "Nyajena" as it appears in the rest of the text.

39 AUA. Letter from Native Commissioner Mrewa to the Chief Native Commissioner. 18 October 1909.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 AUA. E. Sells. Medical Practice Between 'Two Worlds': A Woman Tells How Dr. Gurney Put Back

43 Ibid.

44 AUA. Ellen Bjorklund. Report of Medical Work at Old Umtali, Rhodesia Mission Conference Methodist Episcopal Church. November 1926.

45 Ibid.

46 AUA. Samuel Gurney. Report of the Conference Medical Director, Rhodesia Mission Conference Methodist Episcopal Church. June 1923.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.