Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versão On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versão impressa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.49 no.2 Pretoria 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/12876

ARTICLE

Church Life amid Two Pandemics: Similarities and Differences between Covid-19 and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic on Congregational Life in the Dutch Reformed Church, South Africa

Leslie van Rooi

Stellenbosch University, South Africa lbvr@sun.ac.za. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0295-1761

ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic continues to affect congregational life in South Africa, and churches across the globe are still contemplating the impact of the (ongoing) pandemic, owing to experiences of pain, loss, and absence of direct interaction on the one side, and new possibilities linked to technology and innovative practices amid a global pandemic, on the other. Much has been written about similarities between this pandemic and other global pandemics, specifically on similarities and differences between the Covid-19 pandemic and the 1918 influenza pandemic. This comparison has also emerged in ecclesial studies and reflections. This article will reflect on similarities and differences between congregational life during the Covid-19 and the 1918 influenza pandemics in the context of South Africa. Specific mention will be made of necessitated congregational adjustments linked to practices and rituals during these pandemics in the context of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa. In relation to both pandemics and periods, the official mouthpiece of the Dutch Reformed Church, Kerkbode, will be used as a primary source through which the similarities and differences between the mentioned pandemics will be discussed. Other church archival material and relevant church historical studies will be used to reflect on the 1918 period. Recent publications linked to this topic, as well as general congregational experience and reflections, will be used to explore the 2020 period. As such, this article makes use of various research methods, including archival research and textual and comparative analysis.

Keywords: Covid-19; 1918 influenza pandemic; Dutch Reformed Church; Kerkbode

Introduction, History, Historians and the Two Pandemics

Historians often remind us that we should be wary of thinking about major global occurrences as "once-in-a-lifetime" events and that we should refrain from referring to seismic events as unique or specific to an era or generation. This is good, especially when it comes to studies and perhaps comparisons on the effect of global pandemics on our lives (Hartley, Danielson, and Krabill 2021, 7). It also applies to a study on the impact of global pandemics on congregational life. History guides us in assessing the similarities and differences in our experiences during these major occurrences. This, after all, is its role.

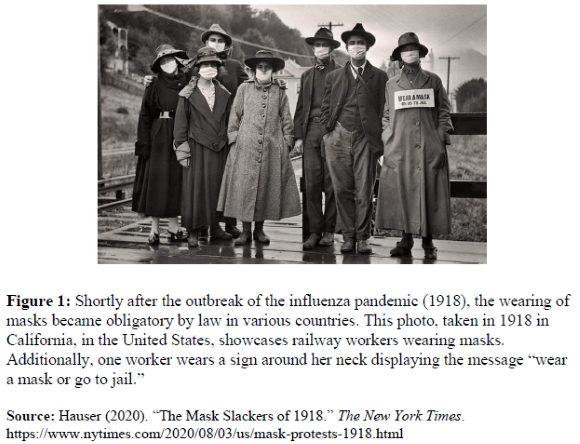

Vosloo (2007), engaging with the work of Paul Ricoeur, reminds us that it is not the entire role of historians.1 The other is to help us understand how and what we remember. This is important in a study that compares two pandemics that had a major influence on the societies of the time because, although there are similarities in history, we never have a completely identical repetition of, for example, a pandemic. Our memory is influenced by our experience(s) and is tainted by other ongoing experiences. However, it remains important to remind ourselves that the world has dealt with major pandemics throughout its history and measures like social distancing and mask-wearing are not unique to the Covid-19 pandemic.2 This holds true when it comes to congregational life during major global pandemics. Numerous examples of similarities and differences can be found when studying the congregational impact and effect of the influenza pandemic of 1918 and the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020 and beyond.3

In 1918, the world was rocked by one of the most severe pandemics in contemporary history. The origin of the influenza,4 caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin, remains contested. What is certain is that the virus spread worldwide and had far-reaching effects.

The effects of this virus were no less moving in South Africa. Phillips (1987) reports that the influenza not only caused the death of more than 300 000 South Africans, but that it also compounded the social-psychological effects caused by the South African War (also known as the Anglo-Boer War) and World War 1. The failed rebellion of 1914, droughts of 1914-1916, and even the floods of 1916-1917 contributed to the high levels of social anxiety, reported to be rife in South African society (see Tongwane, Ramotubei, and Moeletsi 2022; Wessels 2015).

The same can perhaps be said of the Covid-19 pandemic. The unexpected coronavirus pandemic (SARS-CoV-2), commonly known as Covid-19, was initially noted in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in December 2019 (World Health Organisation [WHO] 2022). Both highly contagious and dangerous in nature, the illnesses spread quickly around the world. Little knowledge of how Covid-19 spread meant preparedness was substandard, compounded by the fact that its severity was underestimated until WHO proclaimed a public health emergency and a health crisis (WHO 2022). After that, Covid-19 preventive strategies were thoroughly improved, signalling the start of widespread concern and leading the WHO to enact physical seclusion and self-isolation (WHO 2022).

As with the influenza pandemic, the origin of Covid-19 is still contested in many circles to the present day. Also, similar to the influenza period in South Africa, the effect of Covid-19 on South Africa has been compounded by high unemployment, social instability, poor education and a struggling healthcare system (Spaull et al. 2021).

This article seeks to revisit the effects of the influenza pandemic on congregational life in the context of the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC).5 The DRC, which established its foothold in South Africa with the arrival of Dutch Settlers in the mid-17th century, was a particularly relevant role player in the lives of many South Africans of the time, particularly after its expansion in the late 19th century.6

Kerkbode7 will be used as a basis document and primary source of information for church- and congregation-related events during the period of the influenza pandemic.8A publication edited by Nell (2021) will be used as a reflective research source that highlights thinking, engagement and praxis in congregational life during the Covid-19 pandemic. Both sources focus on congregations in the context of the DRC. Shared experiences are not limited to congregational life in the mentioned church, but this is perhaps a different reflective study.9

In the following sections, themes like medical advances, the effect of lockdown on congregational life, the focus on sermons and biblical reflection during the two pandemics, as well as general, adjusted practices and rituals, will be detailed comparatively. The effect and understanding of the influenza pandemic (1918) will be discussed, followed by that of the Covid-19 pandemic (2020).

Medical Advances and the Effect of Lockdown on Congregations

One of the most significant differences between the two pandemics is the massive expansion of medical science and its impact on supporting lives during the Covid-19 pandemic. Medical advances, linked with stronger international collaboration owing to the advances of technology, have reshaped some of the experiences that were just out of reach during the time of the 1918 influenza, when pharmaceutical means of combating the virus were extremely limited. The lack of vaccines to treat the virus and its effects meant that non-pharmaceutical practices were employed worldwide to try to curb or control the spread of the virus. The most well-known practice remains that of isolation.

In the context of the DRC, this was no less true since many churches were ordered by local and municipal government bodies to close their doors.

Public reception of these orders from government seems to have been mixed, with some parties grasping the now well-understood importance of isolation, and others stubbornly speaking out against it. Notably, and somewhat unsurprisingly, records from Kerkbode suggest that not everyone in the DRC was pleased with these government instructions (Kerkbode 1918a, 17 October). Kerkbode (1918a, 17 October) contains a subsection named Gesloten Kerken (closed churches), which includes a document vehemently condemning the fact that churches were closed while bars, the races (horse racing) and other social venues remained open. Later that same month, the then Cape Town Municipality ordered bioscopes and theatres to be closed.

In a similar instance, Kerkbode (1918a, 17 October) criticises those who went into isolation, stating that such acts reflected an attitude that could not be reconciled with Christianity. This type of resistance was not common but aligns with other reactions of Capetonians at the time (Phillips 2018). A clear sense of indignation is felt by some at the uninvited intrusion into their lives. In some cases, this led to overt resistance, like hiding bodies to prevent them from being buried in a mass grave, or when the Council's cleaning gangs were harassed, impeded, and even attacked while attempting to remove trash from backyards as part of their clean-up campaign (Phillips 1984, 58).

Some similarities exist between the influenza and the Covid-19 pandemic. Congregations grappled with the implications of church closures by law. Kerkbode serves as a catalyst illustrating this through articles voicing church members' thoughts on the subject (Kerkbode 2020b, 12 June, 3-4). There are those who praised government regulations and the church' s compliance, arguing the safety of church members to be paramount (Kerkbode 2020b, 12 June, 3-4). It seems younger members of the church adapted more easily to digital churchgoing, as indicated by Kerkbode (2020a, 29 May, 6). Some claimed there were few differences between attending church services and passively attending a service digitally, pointing out that some churches had actually adopted this strategy before the pandemic (Kerkbode 2020a, 31 May, 6).

Others argued that in-person church meetings were more important than ever as church members struggled with the loss of loved ones and the general uncertainty accompanying the pandemic (Kerkbode 2020b, 12 June, 16). As lockdown restrictions were eased, the South African Council of Churches requested bigger and more regular gatherings, more financial aid, and an exemption from taxes (Kerkbode 2020a, 29 May, 15).

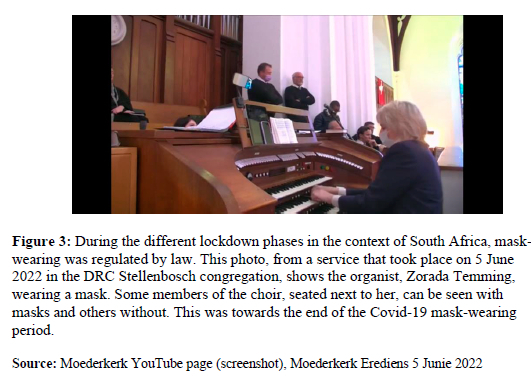

Wepener and Cilliers (2021) remind us vividly of the following: "Sunday, 15 March was the last Sunday during which churches were allowed to celebrate liturgies in their church buildings because of Covid-19 restrictions" (Wepener and Cilliers 2021, 30). They continue that the period following saw various lockdown phases, each with particular implications for church services, amongst others.

Between 22 March and 31 May 2020, worship gatherings were prohibited during levels 4 and 5 of the national lockdowns. The situation changed during level 3 lockdown that commenced in June 2020 when a maximum of 50 people were again allowed to gather for worship but under very strict conditions. (Wepener and Cilliers 2021, 31)

Clearly, government regulations had a direct effect on congregational life during the two pandemics. Time will tell to what extent Covid-19 will continue to affect congregational experiences beyond regulated periods of isolation and lockdown.

Funerals and Burials: A Painful Effect of Pandemics

Covid-19 brought "new" images of individuals on ventilators in ICU, numerous deaths, often in isolation in hospitals, and horrific images from all over the world of storing bodies and mass funerals. Think of the situation in 2020 in Italy, Spain, India and parts of South Africa.10 As horrific as these scenes were, we could be tricked into believing that this was the first of its kind. Hence, it is worth looking at practices during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

A prominent issue was the practicalities concerning the disposal of those who died owing to the influenza pandemic. As South Africans dealt with thousands of fatalities, the burial of the deceased, the burial rites that would typically accompany such ceremonies, and the locations of such burial rites were impacted. The following extract from a letter written during the pandemic provides some context to the exact gravitas of what South Africans experienced:

Whole families in a cottage were deceased and nobody would know about it. And so whole houses, whole families just died out. ... Now we don't know how many people died, but we do know that not all of them were buried [in cemeteries]. I believe that thousands of them were simply buried in graves dug on the beach in the sand and that they are still there. Long trenches were dug, and bodies wrapped; they couldn't use coffins-there were no coffins. ... They couldn't keep up (the supply of coffins). Can you imagine. (Siebörger and Firth 2020)

This was also a profound issue for the DRC. Cemeteries quickly filled up and were deemed unusable when the isolation-related regulations prevented large groups of people from gathering at funerals. Kerkbode11 (1918a, 17 October, 993) reported that some church members were buried on their own property, attended by family and a minister. Indeed, as shown above, large numbers of deceased were buried in shallow graves without any funeral or burial rites.

There are reports of ministers being assigned extra rooms at various buildings, such as the house of the then Superintendent of Cape Town, so that funerals could be conducted at all hours.12 Phillips (1984) quotes an elder of the DRC who remarked that the influenza pandemic was so strange that it felt like the end of times:

Dit het vir my gesmaak of die end van die mensdom daar was. Daar was meer begrafnisse op een dag as in gewone omstandighede in 'n hele maand. Dit het gelyk of die aarde oopgeploeg was.13 (Phillips 1984)

Cape Town Municipality promised a "decent" funeral for all Whites, with payment to be made after the epidemic was done, to calm concerns among the poor that some "flu victims" would only receive paupers' graves. Research shows that such promises were of little value. Phillips (1984) reports that Whites did receive their coffins, but that there was little to no ceremony surrounding these funerals. As conditions worsened and undertakers broke under the strain of so many deaths, coffins were eventually just stacked upon one another and transported to cemeteries or mass graves (Phillips 1984). Towards the end of the influenza pandemic, the remains of both rich and poor people were wrapped in sacks as ministers of religion stood by to perform funeral rites. Wood ran out, preventing the construction of coffins. The deceased were spread out on the streets, and a wagon carried them to their final resting place.

It should be noted that, unlike in 2020, churches did not close officially during the influenza pandemic. At least, there was no national regulation prohibiting church gatherings. During the time of the influenza pandemic, gatherings were postponed or adjusted (e.g., sermons preached outside). Kerkbode (1918c, 31 October) notes, as shared by a correspondent from a local newspaper, that the mayor of Cape Town requested churches to be closed during the pandemic (Kerkbode 1918c, 31 October, 1034).

According to Kerkbode, data on deaths and burials in Kimberley were better recorded during the influenza pandemic compared to those in Cape Town (Kerkbode 1918a, 17 October, 993). This probably has to do with significant mining activity in and around Kimberley at the time. Significantly, there was a sharp increase in death notices linked to the influenza pandemic in Kerkbode of 1918 from full pages (Kerkbode 1918d, 7 November, 1068-1071) to notices stating that there was no longer enough space to share these notices (Kerkbode 1918f, 21 November, 1107).14

Wepener and Cilliers (2021, 32-42) help us to understand the significance of lockdown during Covid-19 on general congregational practices and funerals. Funerals were allowed, albeit under strict, often-changing regulations that had an impact on liturgical practice. Mbaya (2021) points out that the government played an interesting role in society during this period. Through the intended outcome of restricting the number of people who could attend a funeral during lockdown, the government wanted to save lives. In so doing, the government was acting as an agent in the mission of God (Missio Dei) in the context of South Africa (Mbaya 2021, 210).

As Wepener and Cilliers (2021, 32-33) point out, congregational rituals continued to the extent that they were possible. "Sunday services were recorded and shared online via social media, weddings were postponed, large events (including funerals) were adjusted. " How congregations adjusted was influenced by, amongst others, the economic realities of congregations and of members, technical skills, and the liturgical tradition of the congregation (Wepener and Cilliers 2021, 32).

With regard to the use of social media during rituals such as funerals, Matthee (2021, 151) contextualises this matter. He notes that this is not a completely new phenomenon but that it was used more explicitly during Covid-19 compared to the period(s) before. However, he notes that social media was used complementarily to in-person gatherings at, e.g., funerals by a smaller number of individuals, often the most direct members of family (Matthee 2021, 151). The use of digital memorial pages came into being during the Covid-19 pandemic. The In Memoriam page on the website of Kerkbode is interesting in the context of the theme of this study. According to Matthee, this page was used to celebrate the lives of prominent members of the DRC and other related denominations (Matthee 2021, 154).15

First-hand accounts from Kerkbode (2020a,b,c) illustrate the unique strangeness of memorials and funerals during the Covid-19 pandemic. Dalene Flynn, theologian and consultant (Flynn 2020), notes that it struck her poignantly when she attended a memorial online that there was no serving of "tea and funeral sandwiches" afterwards (Kerkbode 2020a, 29 May, 12). There are also notes on how severely strange it was trying to comfort those who had lost loved ones without being able to offer any physical touch or the fact that all conversation had to take place from behind masks.

It can be concluded that Covid-19 had a dramatic influence on the way funerals and burials took place during the pandemic. The strangeness, pain, and sudden adjustments during the two pandemics will be remembered.

Cancelling Church Meetings and Gatherings

Another similarity between the two pandemics is the fact that church gatherings and services of all forms were cancelled, specifically services inside church buildings where congregants would be in close contact. Some services were held outside.16

Various issues of Kerkbode in 1918 mention the postponement or cancellation of official church meetings owing to the influenza pandemic. These include the postponement of the annual closing of the Theological Seminary (Kerkbode 2018a, 17 October, 985), postponement of the presbytery meetings of Paarl (Kerkbode 2018a, 17 October, 985), Albany, Britstown, Queenstown and Colesberg (Kerkbode 1918b, 24 October, 1005), Cape Town and George (Kerkbode 1918c, 31 October, 1025), and Stellenbosch (Kerkbode 1918d, 7 November, 1050) as well as the postponement of the 1918 admissions exam of the university (Kerkbode 1918d, 7 November, 1049).

Then the news changed. From Pearston in 1919 came the message: "De Griep is, Gode zij dank, verdewenen. Die plaatsen echter van sommige dierbaren zijn ledig17" (Kerkbode 1919b, 30 January, 107). As the year progressed, it was clear that things started to return to "normal" (see Kerkbode 1919c, 12 June, 569), albeit a "new normal"-a phrase often used in the "post-Covid" period.

There are frequent references in Kerkbode (2020a,b,c) to pleadings both of members and ministers to cancel gatherings and church meetings. Johan Brink, chairman of the DRC Synod Goudland, argued that such a sacrifice would be necessary to protect one's loved ones and would thus fall in line with Christian principles. Brink pointed out that they could not assure anyone's safety during the pandemic and would need to carry legal liability if gatherings were held. As the pandemic ran its course, this sense of alarm did not dissipate when churches were opened to the public again. Many spoke out against the dangers and complexity of measures the church would face (Kerkbode 2020a,b,c).

Some felt churches should never have closed their doors. Some church members spoke out against the fact that they were excluded from the decision to close doors, while others questioned the mandate of those who made the decision (Kerkbode 2020a,b,c).

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, there seems to be a difference of opinion between how churches and congregations saw the request for churches to cease activities and for congregations not to worship together. Phillips (2020) reminds us that, especially in Calvinist churches, congregations did not take kindly to declarations against public worship during the influenza pandemic (Philips 2020, 440-441). This while churches in general, at least at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, accepted that congregational worship would not be possible (Phillips 2020, 441). Hence, adjustments were made where possible.

The use of social media during the Covid-19 pandemic was unique-also in congregational life. Technology in the 21st century and the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution are, unsurprisingly, two of the main reasons for the significant distinctions between the effects of the influenza and the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly the increased connectivity, accessibility, and communication made possible by the internet, social media, Zoom, YouTube, Microsoft Teams, and so forth (Phillips 2020, 441), granting access to many, even if only virtually, during this time of isolation. Such connectivity also allowed one to stream church and burial services.

At the time of writing this article, things seemed to be back to "normal," albeit differently. No government-regulated restrictions were in place anymore, but some congregations still made use of a blended model by which in-person services were being streamed.18

The Wrath of God: Finding an Image of God to Better Understand Strangeness and Fear

As noted, the origin of the influenza pandemic was a challenge. Not only did this play out in terms of medical research and world politics, but it also led to conversations in congregational circles.

One of the first published articles alluding to the effect of the influenza in the DRC is found in a sermon in Kerkbode (1918a, 17 October, 985-993). This sermon on the pestilence (Pestilentie) makes it clear that this pandemic is God-sent and is necessitated by a sinful life (Kerkbode 2018a, 17 October, 992-993). The minister draws striking parallels between the pandemic and the myriad of divine penalties visited upon the Israelites. The readers are guided to understand that the pestilence can be stopped through prayer (Kerkbode 2018a, 17 October, 993). This sentiment is shared in an editorial in Kerkbode (1918b, 24 October, 1005).19 From this perspective, one can interpret the sentiment of the time in the context of some theological circles of the DRC.

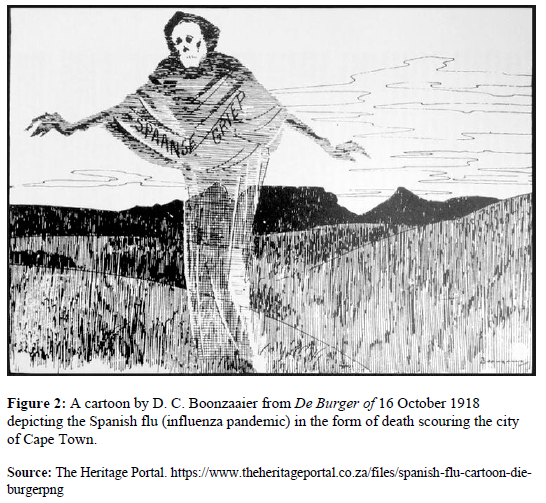

In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, Phillips (2020) notes pertinently that fearful people have used a form of theodicy for most of recorded history to explain catastrophes by attributing them to the deeds of some strong, supernatural entity, whether benign, malicious, or ancestral. Phillips (2020) echoes renowned epidemic historian Charles Rosenberg in arguing that this is true in the context of pandemics. The demand for such an explanation increases drastically when a tragedy manifests itself as a deadly pandemic spreading rapidly and unchecked.

According to Phillips (1987), it is not unexpected that plagues give birth to several messianic prophecies because these predictions typically materialise during periods of extreme societal hardship. In the South African context, according to Phillips, the influenza pandemic:

... was one of numerous calamities and illnesses that inspired such apocalyptic prophesies. The prophetess Nonketha Mekwenke rose to prominence as the head of a movement that preached of apocalypse and redemption that blended elements of traditional Xhosa religion and Christianity in the King Williamstown area, which had been devastated by the plague. (Phillips 1987, 79)

As this prophetess so accurately indicates, the above-mentioned argument is by no means a novel one in the context of Christianity. Plagues and pandemics are commonplace in the Bible-the term plague occurs approximately 100 times in the scriptures, depending on the translation (King James Bible Dictionary 2022). Tales of plague and sickness are usually underscored by God's displeasure or wrath. Tales of Noah's ark, the Israelites' struggle against Pharoah, and much of the book of Revelation come to mind when one reflects on this issue, with these stories similarly supporting the argument of God's wrath in 1918 and 2020 (Lietaert Peerbolte 2021).

Phillips (2020) points out that this necessity to explain and connect a tragedy like a pandemic to evil, sin or wrath does not only have religious connotations. Linked to the effect of the 1918 influenza pandemic, he notes:

Equally untouched by the scientific breakthroughs of the preceding seventy years were most Africans who were neither Christian nor Muslim. These traditionalists started from a quite different explanatory premise, rooted in this case in both the human and spiritual world, namely that death on such scale was unnatural and so must be the product of the actions of ill-intentioned people, namely witches or wizards driven by anger, envy, or selfishness. (Phillips 2020, 438).

However, this is compared to those who will be missed the most, namely young men and women who still had the power of life (free translation by the authors) (Kerkbode 1918b, 24 October, 1005).

The idea of the wrath of God was interpreted differently in different church traditions. Phillips (2020, 439) shows that the Dutch Reformed Calvinist tradition, also in the context of the influenza pandemic in South Africa, was particularly focused on the belief that the wrath of God was responsible for the pandemics In contrast, Phillips (2020, 439-440) notes that the Methodists and the South African Congregationalists were coming to terms theologically with developments in medicine and science; thus, they had a different view on the matter.

Community Interaction and Relations in Times of Dire Need

There are numerous similarities and differences in terms of community interactions and relations during the times of the two world pandemics mentioned that plagued South Africa. In nature, such parallels range from small instances of communities pulling together to striking manifestations of stereotyping and discrimination. Kerkbode (1918f, 21 November, 1109) continually refers to the solace provided in seeing South Africans acting with kindness and fraternity.

As mentioned, the content of sermons and the nature of rituals linked to congregational life were adjusted during the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the mentioned socioeconomic circumstances and complexities that played out in South Africa in 1918, it is important to ask what role the church, specifically the DRC, played in the midst of socioeconomic distress during the influenza pandemic.20

Perhaps most notable in the context of the 1918 influenza epidemic is that the DRC was concerned with the many children left destitute after their parents had died of the pandemic. The well-known Ds. A. D. Lückhoff, on behalf of the DRC, requested church councils to submit names of orphans left destitute, to be shared with the church office (Kerkbode 1918g, 28 November, 1131).21 From historical documents, we know that this helped to expand the growing focus of the DRC on establishing orphanages as part of its role in society.22

Issues of Kerkbode published during the first waves of the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa (2020) make it clear that church members not only stood together during the pandemic but also reminded each other of the fact that the church, particularly the DRC, has survived similar circumstances. An opinion piece in Kerkbode (2020a, 29 May) reminds others that the church survived multiple wars, catastrophic events and, indeed, another pandemic (Kerkbode 2020a, 29 May, 16). Articles speak of charity runs organised to raise money for food, while others speak of the positives that the pandemic offered, including a time for reflection, more time to help those in need and more time with close family (Kerkbode 2020a, 29 May, 10; 2020b, 12 June, 12).

Hancox and Bowers du Toit (2021, 163) remind us that the Covid-19 pandemic was a particularly difficult time for the church. Severe economic distress brought about increased hunger for millions. The church also had to adhere to strict lockdown restrictions and, like all other grassroots faith-based organisations, could not serve communities as usual during times of community-based distress. Organisations like the church could not use their networks and resources to support the poorest of the poor.23As the need grew and as restrictions eased, organisations partnered to form wide-reaching platforms to support the most vulnerable. A newly formed Stellenbosch-based umbrella organisation, Stellenbosch Unite, is one such example that grew out of need and out of the impact of the dire situation that confronted various communities.24

Clearly, the church remains an agent of change and a key role player in enhancing the well-being of individuals across our country. The work of the organisation Badisa, jointly managed by the DRC (Western Cape Synod) and the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (Cape Synod), is a moving example of this.25

Church Rituals

Days of prayer are often scheduled by churches within the so-called Family of Dutch Reformed Churches, especially in times of crisis (e.g., droughts) or to give thanks (e.g., when droughts are broken). Examples of these rituals were also found during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Kerkbode (1918c, 31 October, 1019-1026 shares the news that the DRC in the Cape called for a day of "verootmoediging en gebed" (coming before God in prayer) and by the DRC in Transvaal. This request was again shared-all congregations of the DRC were asked to join in the day of "verootmoediging en gebed." The day, scheduled for 10 November 1918, called on congregants "met diepe verootmoediging en zonde-belijdenis voor dan Heere te stellen en Hem ootmoediglijk te smeeken zijn slaande hand terug te trekken" (Kerkbode 1918d, 7 November, 1049).26

Writing from the perspective of the church in the South, specifically from Indonesia, Darmawan, Giawa, and Budiman (2021) help us to understand both the positive and negative with regard to the effects of Covid-19 on congregational life in their context. They note:

It is undeniable that the negative impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic are great and complex since it impacts church activists, members and ministry in relation to mental state, spirituality, economic state, social life, and other aspects. The pandemic has changed patterns, characters, approaches, cultures, and other aspects in understanding the true Church. A majority of the congregation tends to assess the situation very negatively. On the other hand, it is necessary to have logical awareness that the existence of Covid-19 has positive value and meaning. Therefore, the situation should be assessed with an open and positive view. (Darmawan et al. 2021, 96).27

The above authors have referred to sermons reflecting on the origin of the influenza pandemic. Covid-19 brought about changes in the content and liturgical practice linked to sermons shared during the various phases of lockdown in certain churches and congregations. Steyn and Wepener (2021) led a research project in the DRC to analyse 63 sermons delivered by 23 preachers in 12 Dutch Reformed congregations between March and July 2021 (Steyn and Wepener 2021, 53-71). They indicate that the content of sermons, linked to the liturgical year, was largely influenced by the pandemic, including a focus on comforting and calling congregants into action in supporting one another (Steyn and Wepener 2021, 71).

Most interesting at the end of the 1918 influenza pandemic was that the practice of communion started to change. Congregations started to move away from drinking from one cup, and single communion glasses became practice in the DRC, as in many other Reformed Churches, until the present day. In this regard, Kerkbode published an article from a different newspaper on the matter (Kerkbode 1919b, 30 January, 112-114).28

There were a number of changes to rituals and even in relation to the content of sermons during the two pandemics. Both pandemics brought about rituals that saw temporary and permanent changes in congregational life. Matthee (2021, 145) reminds us that "rituals have evolved with humanity over the ages. Therefore, it is not strange nor threatening that rituals change over time." These changes and additions, although "unique" to the context of the two pandemics, should also be understood within the context of the ever-evolving space of rituals.

Conclusion

Although this is not an in-depth study focusing on specific rituals, practices, and impact, clearly, there are numerous similarities between the Covid-19 and influenza pandemic in church life in the context of the DRC.29 This reflective knowledge has been shared in other disciplines, e.g., economic history, but reflections from within a church historical perspective have been limited. As such, this article draws our attention to the lessons, perspectives, similarities, differences and varying viewpoints, from a church historical perspective, on the two pandemics as they played out in church life in two very different eras.

Although further reflection is needed, this article also notes some differences when congregational life is compared during the two pandemics. These can, amongst others, be attributed to contextual differences (e.g., the nature and use of technology) and an understanding of faith and congregational life. Kerkbode (2020c 31 July, 5) included an article speaking of the reliance people formed on social media applications throughout the pandemic. Understandably, this was unthinkable in the time of the influenza since these platforms, and most of what enables them, just did not exist.

Given the dramatic impact of the two world pandemics in the context of South Africa, church and congregational life were largely influenced in the periods during and closest to the centre of the pandemics. It remains to be seen whether and what the possible (if any) lasting effects of changes in practices will be post-Covid-19. But since churches and congregations are still reflecting on their experiences, many congregations are clearly still figuring out their "new" role in society.

In this regard, Barney Pityana reminds us:

Covid-19 is ultimately never just about the person affected or dying in isolation at a point in time. It is about community and family. The work of caring, of assurance and hope, is an ongoing task for those who understand the dynamism of community that is formed and shaped by a selfless community. (Pityana 2020, 10)

Perhaps this is the sign of the largest impact on congregational life, not only during the Covid-19 pandemic but also during the influenza pandemic.

References

AVBOB. 2021. AVBOB 100 Facts. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://m.avbob.co.za/Articles/Avbob100Facts. [ Links ]

Badisa. 2022. Badisa Home Page. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://badisa.org.za. [ Links ]

Boonzaaier, D. C. 1918. "Spanish Flu Cartoon." Die Burger.png: The Heritage Portal (n.d.). Spanish Flu Cartoon-Die Burger.png | The Heritage Portal. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.theheritageportal.co.za/files/spanish-flu-cartoon-die-burgerpng. [ Links ]

Coertzen, P. 2002. 350 Years Reformed: 1652-2002. Bloemfontein: CLF Publishers. [ Links ]

Darmawan, I. P. A., N. Giawa, and S. Budiman. 2021. "Covid-19 Impact on Church Society Ministry." International Journal of Humanities and Innovation (IJHI) 4 (3): 93-98. https://doi.org/10.33750/ijhi.v4i3.122. [ Links ]

Flynn, D. 2020. "Hartseer, Vrees en Protokol." Kerkbode, 29 May, 12. [ Links ]

Gaum, F. M. 2010. "Kerkbode ná 160 Jaar." Dutch Reformed Theological Journal 51 (1): 95-103. [ Links ]

Hancox, D., and N. Bowers Du Toit. 2021. "Faith-based Organisations as Key Role Players during Covid-19. The Need to Challenge Dominant Ecclesiologies in the Context of Covid-19 Socio-economic Distress." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell, 1163-1181. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi. [ Links ]

Hartley, B. L., R. A. Danielson, and J. R. Krabill. 2021. "Covid-19 in Missiological and Historical Perspective." Missiology: An International Review 49 (1): 6-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091829620972386. [ Links ]

Hauser, C. 2020. "The Mask Slackers of 1918." The New York Times. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/03/us/mask-protests-1918.html. [ Links ]

King James Bible Dictionary. 2022. Reference list-plague, King James Bible Dictionary. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://kingjamesbibledictionary.com/Dictionary/plague. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1918a, 17 October, 993-994. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1918b, 24 October, 1005-1006. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1918c, 31 October, 1019-1035. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1918d, 7 November, 1049-1071. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1918f, 21 November, 1107-1109. [ Links ]

Kerkbode 1918g, 28 November, 1131 [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1919a, 2 January, 1-3. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1919b, 30 January, 107-115. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 1919c, 12 June, 569. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 2020a, 29 May, 1-20. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 2020b, 12 June, 1-20. [ Links ]

Kerkbode. 2020c, 31 July, 1-20. [ Links ]

Lietaert Peerbolte, B. J. 2021. "The Book of Revelation: Plagues as Part of the Eschatological Human Condition." Journal for the Study of the New Testament 55 (1): 75-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0142064x211025496. [ Links ]

Matthee, N. 2021. "Do Funerals Matter? Grieving during Covid-19." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell, 144-162. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi. [ Links ]

Mbaya, H. 2021. "Covid-19 and Missio Dei. Opportunities and Challenges for the Church." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell, 201-218. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi. [ Links ]

Mouton, D. 2021. "New Wineskins. Re-thinking Faith Formation in Light of the Covid-10 Pandemic." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell, 238-259. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi. [ Links ]

Nell, I. (Ed.). 2021. Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi. [ Links ]

Nederduits Gereformeerde (NG) Kerk. 2022. Instansies van die NG Kerk. Gemeentegeskiedenisargief. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.gemeentegeskiedenis.co.za/instansies-van-die-ng-kerk/. [ Links ]

Phillips, H. 1984. "Black October: The Impact of the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918 on South Africa." PhD thesis, University of Cape Town. [ Links ]

Phillips, H. 1987. "Why Did it Happen? Religious and Lay Explanations of the Spanish Flu of 1918 Epidemic in South Africa." Kronos: Journal of Cape History 12 (1): 72-96. https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA02590190_574. [ Links ]

Phillips, H. (Ed.). 2018. In a Time of Plague. Memories of the "Spanish" Flu Epidemic of 1918 in South Africa. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society. [ Links ]

Phillips, H. 2020. "'17, '18, '19: Religion and Science in Three Pandemics, 1817, 1918, and 2019." Journal of Global History 15 (3): 434-443. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1740022820000315. [ Links ]

Pityana, B. 2020. "More Eyes on Covid-19: Perspectives from Religion Studies: How Christian Theology Helps Us Make Sense of the Pandemic." South African Journal of Science 116 (7/8): 10-11. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2020/8498. [ Links ]

Siebörger, Rob, and Barry Firth. 2020. "Teaching about Dying and Death: The 1918 Flu Epidemic in South Africa." Yesterday and Today (24): 176-190. https://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2223-0386/2020/n24a9. [ Links ]

Spaull, N., R. C. Daniels, N. Branson, G. Bridgman, T. Brophy, R. Burger, D. Casale, G. Espi, K. Ingle, A. Kerr, T. Köhler, B. Maughan-Brown, L. Patel, D. Shepherd, D. Stein, M. Tomlinson, I. Turok, J. Visagie, and M. Wittenberg. 2021. Synthesis Report NIDS-CRAM Wave 5. South Africa, Stellenbosch University. https://cramsurvey.org/. [ Links ]

Steyn, M., and C. Wepener. 2021. "Pandemic, Preaching and Progression. A Grounded Theory Exploration and Homiletical Praxis Theory." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell, 51-74. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi. [ Links ]

Taylor, A. 2020. "An Unimaginable Toll." The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2020/04/coronavirus-unimaginable-toll-photos/609652/. [ Links ]

The New York Times. 2020. Accessed 10 September 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/03/us/mask-protests-1918.html. [ Links ]

Thomas, A. 1996. Rhodes. The Race for Africa. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. [ Links ]

Tongwane, M. I., T. S. Ramotubei, and M. E. Moeletsi. 2022. "Influence of Climate on Conflicts and Migrations in Southern Africa in the 19th and early 20th Centuries." Climate 10 (8): 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli10080119. [ Links ]

Van Rooi, L. B. 2015. "Identity, Boundaries and the Eucharist. In Search of the Unity, Catholicity and Apostolicity of the Church from the Fringes of the Kalahari Desert." Dutch Reformed Theological Journal 51 (12): 176-185. [ Links ]

Vosloo, R. 2007. "Reconfigurating Ecclesial Identity: In Conversation with Paul Ricoeur." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 33 (1): 273-293. https://doi.org/https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/4468/Vosloo.pdf;sequence=1. [ Links ]

Wepener, C., and J. Cilliers. 2021. "Lockdown Liturgy in a Network Culture. A Ritual-liturgical Exploration of Embodiment and Place." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi, 30-50. [ Links ]

Wessels, A. 2015. "Afrikaner (Boer) Rebellion (Union of South Africa)." In 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, edited by U. Daniel, P. Gatrell, O. Janz, H. Jones, J. Keene, A. Kramer and B. Nasson, 1-10. Berlin, Germany: Freie Universität Berlin. [ Links ]

World Health Organisation. 2022. "Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19)" Accessed November 15, 2022. file:///C:/Users/janha/Downloads/who -china-joint-mission-on-covid- 19-final-report-1100hr-28feb2020-11mar-update.pdf. [ Links ]

1 See Vosloo (2007). "Reconfigurating Ecclesial Identity: In Conversation with Paul Ricoeur." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 33 (1): 273-293. https://doi.org/https://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/4468/Vosloo.pdf;sequence=1.

2 For a historian, it is interesting to read through history books as this allows for various perspectives on history in context. Linked to the focus of this article, it is interesting to read historical documents highlighting contextual similarities. One such example is the book on Rhodes by Anthony Thomas, where Rhodes highlights the outbreak of the smallpox epidemic and its impact on the mining industry of the time in Kimberley, South Africa. The striking similarities with, e.g., vaccination requirements then and during the Covid-19 pandemic, are of interest. See Thomas (1996). Rhodes. The Race for Africa. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball Publishers. As with similar publications, this book should be read as a resource, albeit limited, of its time.

3 Last mentioned still affects the world in various ways as the virus remains present amongst us.

4 In this article we use the term influenza to refer to the pandemic of 1918. We acknowledge different terms for this pandemic, including Spanish flu, black flu or the great flu. As with the Covid-19 pandemic, different strands of the virus initially acquired regional names. In an attempt to delink the name of the virus and its strands from regions, these were deliberately replaced by scientific names. This should be seen as a reaction against the names given to the influenza pandemic of 1918.

5 The focus on the DRC in this article is predetermined by the primary source used, Kerkbode, especially in a historic sense. It can be assumed that some of the challenges shared in the context of the DRC are similar to those of other churches within the so-called family of Dutch Reformed Churches, namely the DRC, the Dutch Reformed Mission Church (DRMC), the Dutch Reformed Church in Africa (DRCA) and the Reformed Church in Africa (RCA); also, that the effect of the two pandemics would be similar in the history and congregational life of these churches.

6 For an overview of the history of the Dutch Reformed Church and other reformed churches in the context of South Africa, see Coertzen (2002). 350 Jaar Gereformeerd, 1652-2002. Bloemfontein: CLF.

7 Kerkbode, loosely translated as the Church Gazette, is a publication in South Africa that serves as the official newspaper of the Dutch Reformed Church. As such, it provides news, articles, and information relevant to this church and its members. Kerkbode has a long history and has been in circulation since 1869. It is one of the oldest newspapers in South Africa and has played a significant role in the communication and dissemination of information within the Dutch Reformed Church community.

8 Surprisingly, very little has been written of Kerkbode as primary source for church history-related studies of the DRC and churches within the broader so-called Dutch Reformed Family of Churches. See Gaum (2010). "Kerkbode ná 160 Jaar." Dutch Reformed Theological Journal 51 (1): 95-103.

9 In the publication by Nell (2021), Dawid Mouton writes on faith formation, and the complexities and lessons learned during the Covid-19 pandemic. He focuses on experiences in the Uniting Reformed Church in South Africa (URCSA), and on the churches within the so-called family of Dutch Reformed Churches. See Mouton (2021). "New Wineskins. Re-thinking Faith Formation in Light of the Covid-19 Pandemic." In Covid-19 in Congregations and Communities: An Exploration of the Influence of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Congregational and Community Life, edited by I. Nell, 238-259. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Naledi.

10 See Taylor (2020). "An Unimaginable Toll." The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2020/04/coronavirus-unimaginable-toll-photos/609652/.

11 Kerkbode is used consistently throughout this article. For a long period of its history, the name De Kerkbode was used.

12 One of South Africa's largest undertakers, AVBOB, was established in 1918 in the aftermath of World War 1 and the influenza pandemic in the context of South Africa. See AVBOB 100 Facts. 2021.) AVBOB. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://rn.avbob.co.za/Articles/Avbob100Facts.

13 The remarks of the elder focuses on the number of burials that took place during the time of the influenza pandemic and the strangeness of what he saw playing out before him.

14 Also see Kerkbode (1918f, 21 November, 1107-1109) .

15 This page is still active on the website of Kerkbode. https://kerkbode.christians.co.za/category/inmemoriam/.

16 An anecdote from the Northern Cape shares something of the history of the DRC congregation of Keimoes. In front of the church building of this congregation a large Camel thorn tree is known as the church tree (kerkboom in Afrikaans). The name of the tree arose after church services were held under the tree during the influenza pandemic. The congregation was established in 1916.

17 Translation by authors: Thanks be to God; the influenza is gone. The places of some of our beloved are, however, empty.

18 See the practices of the DRC Stellenbosch (Moederkerk). https://moederkerk.co.za/.

19 This editorial acknowledges the death of people of colour owing to the influenza pandemic.

20 Refer to references in the introductory section.

21 See the report of the inland mission in Kerkbode (1919a, 2 January, 2).

22 For an overview of the history of the established orphanages of the DRC, see Nederduits Gereformeerde Kerk, Instansies van die NG Kerk (2022) Gemeentegeskiedenisargief. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://www.gemeentegeskiedenis.co.za/instansies-van-die-ng-kerk/.

23 The same was true for other community-based organisations, which could not gather under the strict lockdown regulations that played out in stages during Covid-19 in the context of South Africa.

24 See https://stellenboschunite.org/ for more information on Stellenbosch Unite, the partners involved and its impact during Covid-19 in the context of the broader community of Stellenbosch. After the hardest lockdown of Covid-19, partners under the umbrella of Stellenbosch Unite continued with joint activities linked to economic recovery and development.

25 See Badisa (2022). Badisa Home Page. Accessed December 5, 2022. https://badisa.org.za/.

26 The Dutch is freely translated by the authors: to confess their sins and to plead that God will retract his beating hand.

27 See the reference to other global pandemics including the bubonic plague, cholera, Spanish flu, Asian flu, Hong Kong flu (Darmawan et al. 2021).

28 The issue of segregation around the communion cup had many dimensions in the context of the DRC. For an overview of the complexities of separation at the holy communion table in the context of the so-called family of Dutch Reformed Churches, see Van Rooi (2015). "Identity, boundaries and the Eucharist. In search of the Unity, Catholicity and Apostolicity of the Church from the Fringes of the Kalahari Desert." Dutch Reformed Theological Journal 51 (12): 176-185.

29 Although it was not the focus of this study, it would be interesting to compare pandemic-related practices and adjustments between the DRC and the other churches within the so-called family of Dutch Reformed Churches.