Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versão On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versão impressa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.47 no.2 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/8140

ARTICLE

Funnel Representation of Catholic Women in Church Councils

Edmore Dube

Great Zimbabwe University samatawanana@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6774-7094

ABSTRACT

This article problematises the low uptake of higher leadership roles by guild women of the Roman Catholic Church in Zimbabwe. This is despite the fact that they are "over-represented" in the small Christian communities, which they almost "own." They far outnumber men at the funnel base of the organisation, though they are grossly outnumbered by males from the parish council to national levels. Those that make it to higher positions in the church committees, are often relegated to clerical portfolios. What is intriguing, is the fact that the small Christian communities, which have meticulously absorbed more women in all lay ranks, are the foundational bases of the church. They are the praxis units exposing Catholic dogmas to the community; during celebrations and bereavements, in the absence of the top brass mainly comprised of their male counterparts. They are the conduits that help the catechumens live their faith, and the veins and arteries that feed the Catholic establishment with resources. A similar scenario of firm ecclesiastical control has been noted regarding the same sodality in South Africa. The Manyano/Ruwadzano sodality of the women of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Southern Africa (used as a control group for the research study that directed this article), presented an equally low uptake of leadership posts, despite the existence of women clergy. The disabling institutions were noted as the guild constitutions crafted or passed by male clergy against women, fear of scandal, inculturation and gender. The study recommends the fulfilment of church documents advocating parity between men and women in the election of office bearers. This article acknowledges the life work and career of the late Mary-Anne Elizabeth Plaatjies-Van Huffel, who dedicated all of her remarkable talents to promote gender-equality and social justice.

Keywords: church leadership; gender; guild women; Manyano/Ruwadzano, small Christian communities

Introduction

This article uses the guild/sodality of St Anne to discuss the underrepresentation of women in higher Catholic Church councils in Zimbabwe. Having obtained results from a specific empirical survey authenticating the thesis of the study, the article interrogates literature on the same sodality of St Anne in South Africa, which equally authenticates the funnel representation of sodality women. Using Manyano/Ruwadzano from the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Southern Africa as a control, has produced insignificant variance despite the presence of women ministers. In fact, the women ministers are as underrepresented in the important Methodist councils as the Manyano women. This presents the problem of women underrepresentation as much larger than just a Roman Catholic phenomenon, and its mitigation has to be sought by women across the denominational divide.

The article analyses the constitutions establishing sodalities in parishes, before particularising the guild of St Anne, comprising women with recognised marriages. An evaluation of the constitution of small Christian communities (SCCs) partially answers why women dominance is heavily felt at that level, as reflected in the survey. The motivation behind this article is to evaluate possible reasons for the low uptake of higher leadership posts by Catholic women, and to decipher possible mitigations. We acknowledge the profound body of research, academic work and theological influence in this regard by Mary-Anne Elizabeth Plaatjies-Van Huffel in the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA).

Defining Guilds in the Roman Catholic Church

Guilds are voluntary associations for the laity alone or the lay and the clerics who "strive in a common endeavour to foster a more perfect life" (Code of Canon Law [CCL] 2013, 98). The lay are "encouraged to form associations among themselves for the sake of living the Faith more deeply and spreading the Faith to others more effectively" (Burke 2007, 2). These associations with mutually agreed benchmarks ultimately mould the members into particular personalities, willing or unwilling to assume particular roles. In order to use the term "Catholic" as part of their nomenclature, guilds have to be authorised by a competent church authority (CCL 2013, 98). By using the name Catholic, the association submits itself to the authority of the Magisterium, which harmonises the group with the rest of the church in following the official church doctrine and liturgy (CCL 2013, 98). Only ecclesiastical authority can erect public associations endowed with the duties to propagate church doctrine and to evangelise in the name of the church. Depending on the scope of the association (universal, national, diocesan), the competent authority establishing it would be the Holy See, the bishop's conference or the diocesan bishop respectively (CCL 2013, 100). All associations of the faithful are kept under the watchful eyes of some competent ecclesiastical authority to make sure that they remain morally vibrant (CCL 2013, 99). To enhance that control, everyone has to be validly received into each association and remain thus, unless validly dismissed (CCL 2013, 99). As will become apparent in the next section, the guild of St Anne started as a private association by virtue of an agreement of married women and their lay advisor, before submitting its statutes for verification and validation by ecclesiastical authority. From then on, its activities were closely monitored by nuns and priests as spiritual advisors with the authority to vary or (in the case of nuns) recommend a variation of one's membership.

Establishment of the Guild of St Anne in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe)

The Guild of St Anne was established in 1932 at Gokomere Mission, in the then Jesuit Vicariate of Salisbury (Barr 1978,18), now Masvingo Diocese, after a novena of nine days to "St Mary the Mother of Ideas" (Marimazhira 1998, 10). It was started by lay women as an off-shoot of the Guild of St Theresa of the Little Flower, which had been brought to Gokomere by Emilio Muzira in 1928 as a youth guild, from Kutama Mission in north-western Rhodesia where he did his teacher's training. Fr Apel SJ, the priest in charge at Gokomere Mission, accepted it as the guild of women with canonical marriages, as expressly recommended by Emilio Muzira, then a wedded young man. In 1948 it was implanted at St Patrick's Mission in the Diocese of Bulawayo by Peter and Rita Mhazo from Gokomere Mission, with the express support of the priest in charge, Fr Joseph Kammerlechner. By 1977 it had gone regional by spreading into Zambia and pockets of other neighbouring countries (Marimazhira 1998, 15). It elected its first national executive in the new Zimbabwe, in 1981, under the watchful eyes of Fr Xavier Marimazhira of Gweru Diocese and Fr Groeger Francis CMM of Bulawayo. Ever since then the guild has been credited with resoundingly commendable work by the church leadership (Marimazhira 1998, 5).

The current constitution of the Guild of St Anne accepts membership from the canonically married and those with natural marriages (recognised traditional monogamous marriages of the canonically baptised) (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 2). By accepting the natural marriage, the guild constitution weighs into inculturation, a major trademark of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), which admitted local cultures into the orbit of the church (Knitter 1985, 129). By the same admission, the traditional gender roles also entered the church, "tying a filial knot" with church roles defined by an all-male celibate clergy with no place for women in its supreme governing structures. The guild constitution maintains an organogram from parish to national levels. Each level has spiritual directors including nuns and priests, with those at the parish level overseeing the fulfilment of the entry requirements, including preparations for a full year, and examination by a priest before reception into the guild (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 13-17). The clerical spiritual advisors have the powers to remove a member from a leadership post, thereby causing that post to be re-filled from within the elected members or by co-option; and if deemed necessary, the member is expelled from the guild altogether.

Of particular note are the following characteristics and expectations for the members of the guild. The leading notion is that all their praxes must fit into the cliche: "Better hearts, better homes, better fields" (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 1, 2). In a strongly patriarchal society blessed by inculturation, "better hearts" denote giving in to their male counterparts in many areas, as shall become apparent subsequently (Banana 1996, 70). "Better homes" and "better fields" inevitably confine the woman to the home-setting, conspicuously dominated by the two aspects. This is especially because the woman is encouraged to "pray with the family every day, especially the evening prayer" (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 35). She is also exhorted to accompany the family for Sunday services, and to love her children as her heritage. The local concept of giving children love has connotations of availability, since "it is blessed that you be at home with your family most of the time" (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 36). It is quite possible that this post Vatican II guild constitution was made with inculturation in mind. This is made much more real by the fact that an "all women" guild had to submit itself to the advice and mediation of Emilio Muzira, a man, before it could be accepted by the priest in charge of Gokomere Mission.

The foregoing precepts summarise the lifestyle expected of a guild woman with the "correct aptitude." Such a lifestyle is dominated by novenas, especially praying the rosary throughout the months of May and October each year. In that regard, the very first rule stresses that a member of the Guild of St Anne must be "a woman of prayer" (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 4). Rule three encourages guild women to be fully Christian by coming to church and "praying with others in small Christian communities' [own emphasis] (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 4). Rule six directs the guild woman to actively take part in church mission; especially converting nonChristians, re-invigorating those tiring away, supporting the church and its leadership, visiting the sick, the aged, and offering help to the poor and during funeral services. According to local praxes, all these specifications are mostly applicable within SCCs. This means the guild constitution has largely localised the activities of the women. As though that was not enough, they are encouraged to pay their subscriptions to the SCCs, which feed into the parish, deanery, diocesan and national fiscal policies (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 4).

The preceding discussion has demonstrated that the guild women are only expressly encouraged to participate in their own guild affairs up to national level. For the main body of the church, they are simply encouraged to take an active part in the SCCs, and to assist the leadership at the parish level. No guild precept encourages them to take up leadership roles in the main body of the church, as this may run in the face of their encouragement to be at home most of the time; rendering useless their motto hugely circumscribing their activities within the home loci.

Small Christian Communities

The Roman Catholic Church models its SCCs on the ancient paradigms presented by the early Christian communities (O'Halloran 2002, 166). Those pristine Christian communities were worried about the solidarity of the membership based on interdependence, which enabled them to deal with the needs of each member as they presented themselves (Acts 2:42-47; Acts 4:323-7). One core value of those apostolic communities was pooling resources, which they shared as each had need, with the result that they shared their "joys and sorrows, sufferings and struggles" as organic units (O'Halloran 2002, 167). The Catholic Development Commission (CADEC 1992, 28) encourages the faithful to give generously, "well-knowing that the act of giving is similar to the life-giving of Christ." The constitution of the Guild of St Anne discussed above invites the women to this kind of sacrificial giving without allocating them commensurate leadership roles. It is important to note from the onset that in "all the early Christian groups, it is people who are important. Organisation and buildings are secondary. The faithful meet in homes; there are no churches" (O'Halloran 2002, 169). This is why Paul sends greetings to the church which meets in the house of Pricilla and Aquila (Romans 16:5) and believing members in other households (Romans 16:11 and 16:14-15). What emerges here is the fact that Christians initially met in homes (now a gendered feminine space) as intimate groups, without any involving hierarchical order, a feature which emerged in the time of the Roman emperor Constantine (288-337).

With the establishment of the hierarchical order, the parish emerged as the communion of SCCs (Pelton 2002, 174). In that regard "the institutional church recognises small communities as 'the primary cells of the church structure' and praises them as 'responsible for the richness of faith and its expression as well as for the promotion of the person and development'" (Instrumentum Laboris for the Synod of America as quoted in Pelton 2002, 174). The Vatican relies on SCCs to create and maintain solidarity within the Church (Pelton 2002, 174). Pope Paul VI in Evangelisation of the Peoples (as quoted in O'Halloran 2002, 239) notes that the SCCs are vital if properly linked to the doctrine of the universal church, as essential cells of the universal church which must grow its missionary skills and zeal. O'Halloran (2002, 240) notes with respect to church praxis that "real history takes place at the grassroots ... reform comes from above, renewal from below." In that he credits the SCCs with renewal and revival of church fortunes. Pelton (2002) affirms their capacity at renewal by observing that in the Americas they revived the fortunes of the church, when attendance had reduced to 32% in the United States of America and 12% in Canada (Pelton 2002, 175).

The 1994 African Synod of Bishops held in Rome endorsed the SCCs as invaluable to the African context, standing as they did, as succinct representations of the African communitarianism, and a straight path to inculturation. Any pastoral strategy which ignored them was seen as a complete fiasco for the future church (O'Halloran 2002, 192). These Catholic perceptions of the SCCs are derived from the documents of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). The Lumen Gentium (1967, 62) stresses that "the Lord wishes to spread his kingdom by means of the laity also." It is clear from this Vatican Council document that without the activities of the laity, the church may not be able to open its doors widest for the salvation of humanity; and yet the same laity have to contend with enormous structural obstacles. The structural hurdles are introduced by paragraph 37, which stresses that: "With ready Christian obedience, laymen as well as all disciples of Christ should accept whatever their sacred pastors, as representatives of Christ, decree in their role as teachers and rulers of the church. Let laymen follow the example of Christ, who, by His obedience even at the cost of death, opened to all men the blessed way to the liberty of the children of God" [own emphasis] (Lumen Gentium 1967, 64). This article of the sacred Council opens the laity to docility by accepting "whatever" the clergy wills, in a sacrificial manner.

John Paul II (Paul 1995, 100) defines the parish as "the place which manifests the communion of various groups and movements, which find in it spiritual sustenance and material support" [original emphasis]. Guilds, movements or associations are encouraged, because through them the laity act as the "leaven in the dough (cf Mt 13:33), especially in areas concerned with the administration of temporal goods according to God's plan and the struggle for the promotion of human dignity, justice and peace" (Paul 1995, 101). The current article is particularly interested in their being encouraged, especially regarding the "administration of temporal goods." As already noted above, the administration of material sustenance for parishes is now largely in the hands of associations, and especially within the SCCs. It is within these SCCs that the guilds of women are most active, both in the leading structures and in the provision and administration of temporal goods. The following section deals with the procedures for getting members into executive committees from the SCCs to national levels.

Research Results: Women Representation in 2020 Church Councils

The SCCs are constituted from the parish, presided over by a priest in charge. The priest presides over the parish pastoral council, which demarcates the boundaries forming the loci of SCCs within the parish (CCL 2013, 148; Masvingo Diocese 2007, 2, 4). The said pastoral council only holds consultative authority and has no power to enforce its decisions, which remains the prerogative of the priest in charge. It is the priest in charge, as overseer of the parish, who determines how the elections to the various committees are to be done. He acts as the returning officer, with the authority to delegate that authority to other members of the clergy under him, or nuns if available in the parish. He may decide on secret ballot or nominations and hand-raising, but the general procedure in the Roman Catholic Church in Zimbabwe today centres on cumulative representations. One is selected or elected for a grassroots post first before being eligible for the next level of representation. That means one is first elected to a particular portfolio in a particular SCC and rises through the ranks of that particular post through the parish, deanery, diocese, to the national level. That means one who is elected as chairperson at the grassroots level can only contest the chairmanship up the ladder, unless it is deemed necessary by the presiding officer to alter that path. It is clear that the presiding priest has the final say at every level and the laity have to accept that as directed by the Second Vatican Council and canon law (CCL 2013, 148; Lumen Gentium 1967, 64). The general trend is to take only the holders of posts of chairperson, secretary and treasurer to contest the next set of elections, but as will become apparent, the presiding officer may change the style, as happened in two instances in the election of St Matthew's executive council discussed below.

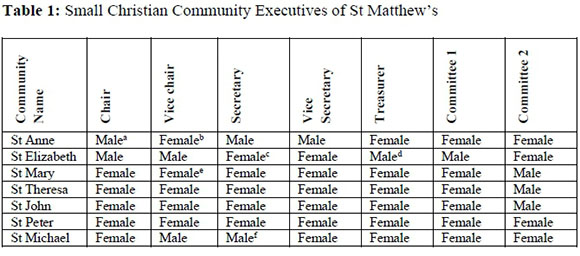

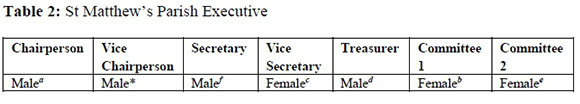

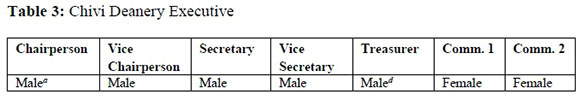

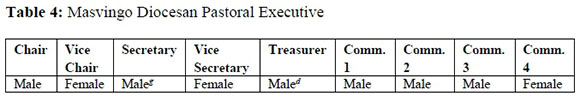

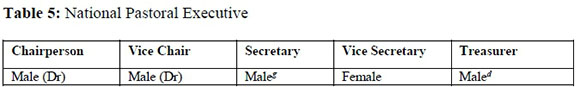

Below we present the current executive standings of the Catholic Church in Zimbabwe, utilising St Matthew's small Christian communities' executives and parish council as representative of other parishes, as the national executive results will ultimately show. Next in line we make use of the executives of Chivi Deanery and Masvingo Diocese, on the road to the national executive. Instead of real names we use male/female for the purposes of anonymity. We also use letters "a" to "g" against particular posts for easy tracking of particular members up to national level. Only St Matthew's treasurer designated with the letter "d" and the diocesan secretary from another parish, designated "g" clinched national posts.

Table 1 above shows that the ratio of female chairpersons to their male counterparts is 5:2. The same holds for vice-chairpersons and secretaries. The posts of treasurer and vice-secretary have the same ratio of 6:1 for females and males respectively, which places a lot of clerical work and community wealth in the hands of women. The overall female-male ratio in the seven executive committees is 37:12, just above 3:1. One would expect the next level to be equally representative of the female membership, considering that the 49 executive members formed the electoral college for the next level, but as the next table shows, the males have already overtaken the females in numbers. The males assume the custodianship of the registers and resources gathered mainly by the women at the grassroots; the women, arguably, surrender their posts and resources "gracefully" to their male counterparts.

First, the presiding officer allowed guild chairpersons to compete for the post of vice chairperson, which brought in the chairperson of St Joseph's Guild for canonically married men (marked by the asterisk *) despite the guild of St Anne being in the overwhelming majority. Vice chairpersons of the SCCs were also allowed to compete for two slots reserved for committee members. The overall result shows that the SCCs that elected males in the key posts of chairperson, secretary and treasurer were better rewarded in the parish council than the rest. Ss. Theresa, John and Peter, heavily dominated by women executives, were left out of the parish executive altogether.

Since the presiding officer at deanery level stuck to the law, it meant that for the female executives of St Matthew's, it was the end of the road. Only three males (a, d, f were eligible to contest the posts at deanery level, and the first two (a and d) made it into the deanery executive.

The table above shows that two members from St Matthew's (a and d) took key posts at deanery level, and on the whole no female from Chivi Deanery was eligible for a diocesan post. Just as women from St Matthew's were not represented in the deanery executive, so were all the women in Chivi Deanery not represented in the Diocesan executive, though they remained the key financiers of the very structures that refused to hear their voices. They were afforded more time to cultivate "better homes and better fields" to host and feed the church.

The table above shows that no single female was voted into any of the three key posts (chairperson, secretary and treasurer); and consequently, no female members from Masvingo Diocese were eligible for national executive posts. For them, it was time to go back home and attend to their cliche of belonging: "Better hearts, better homes, better fields" (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 1, 2).

The table above shows that Masvingo Diocese was represented in two key posts (secretary and treasurer) and that the treasurer of St Matthew's made it right up to national level. The national executive table shows that only one female made it into the top five, in a deputising capacity. The question is: Why such a funnel representation, from just above 3:1 at the grassroots to 1:4 at the national level? We discuss the possible reasons for such results skewed in favour of male executives, using both a literature review and empirical evidence, which observe all the necessary ethical considerations, including free consent and anonymity. It was particularly important to know why women voted in males despite their overwhelming numbers in the initial electoral colleges, and why there were no "Plaatjies-Van Huffels" ready to proclaim: "Here I am, send me"-challenging "embedded patriarchy camouflaged as cultural identity and the hegemony of male power in our church" (Plaatjies-Van Huffel 2019, 3). For Plaatjies-Van Huffel (2019, 8) it is quite sad when women partake "in voting their female counterparts out." With that we turn to South Africa for a documentary exegesis of St Anne sodality.

In South Africa and its littoral, as in Zimbabwe and elsewhere, public sodalities exist under the guidance of a priest at every level (parish, diocese, national). The sodality of St Anne follows the spirituality of Joachim and Anne, the parents of Mary the mother of Jesus. Though the devotion was popular from the third century (Hoever as quoted in Hlatshwayo 1997, 57), "the sodality itself was founded by Fr. R. Honorat OMI in Quebec, Canada, on the 4th of May 1850, and was brought to Lesotho by Bishop Cyprian Bonhomme OMI in 1934." By 1952 it had spread as far as Botswana. The sodality of St Anne, which has expanded since 1992 to include single mothers known as Barwadi ba Anna (daughters of Anne), is the "breeding ground for conversion" (Hlatshwayo 1997, 61). The women sodality has great influence in "community evangelisation," playing major roles in "catechising, visiting the sick, maintaining Catholic standards at home, educating their children in faith and so forth" (Bate as quoted in Ngcobo 2017, 14). They help propagate the motto-Community Serving Humanity-at the heart of the Southern African Catholic Bishops' Conference Pastoral Plan (Hlatshwayo 1997, 59). Moreover, they dedicate "their time and talents, sometimes even their wealth, to look after the Church" (Ngcobo 2017, 14). They channel these through SCCs, the Neighbourhood Gospel Groups (NGGs), and permanent local structures concerned with prayer, sharing and "communal action" (Hlatshwayo 1997, 59). These NGGs are coordinated by the Parish Pastoral Council. This close affinity to the Zimbabwean scenario makes a Protestant comparison more relevant.

Protestant Example: The Manyano/Ruwadzano

Manyano was an off-shoot of the Women' s Prayer Union of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of Southern Africa "which dates back to 1895" (Moss 1988, 19). The name was a derivation from the Xhosa verb "ukumanya" meaning "to join" or "unite"; symbolising the essence of African women's weekly prayer meetings (Haddad 2004, 4; Mkhwananzi, 2002, 31). Article 1 (one) of the Manyano Constitution emphasises the fusion of prayer and service in defining Manyano (Manyano Constitution 2017, 1), making its purpose missio Dei (Dlamini 2017, 4). Manyano was founded by the wife of a Methodist minister in 1907, and though it grew rapidly it was for a long time not represented on the national policy-making bodies at all (Mkhwananzi 2002, i). When recognition eventually came, male leadership only welcomed "one female representative ... so at an organisational level, unfair peripheralisation persists" (Gaitskell 2002, 387). Hinfelaar (as quoted in Frederiks 2002, 201) who compares Manyano and the Catholic Chita chaMaria in Zimbabwe, agrees with Gaitskell: "neither Ruwadzano nor Chita chaMaria have as organisations managed to become part of the policy making body of their respective churches. Though groups to count with and represented in their churches through the women's committee, neither of them has a direct say in the church leadership."

The Methodist Church spread to Zimbabwe from South Africa. Though Mrs Matambo, the wife of a black minister from South Africa, sowed the seed of Manyano (translated by Ruwadzano in Shona) in Zimbabwe in 1917, when the movement was adopted by the Synod in 1920, Mrs Emma White was appointed as president while Mrs Herbert Carter combined the posts of secretary and treasurer (Banana 1996, 69; Moss 1988, 19). Its first black President, Mrs Musa, was only elected in 1963. In Zimbabwe, synod "missionary supervision of the Ruwadzano was a tenuous one at best" (Moss 1988, 20), resulting in some resentment for synod control.

Unlike the Catholics, the Methodists resolved to ordain female ministers more than 40 years ago, but this has not improved Manyano representation in church councils, because the female ministers themselves are also discriminated against. They are not only excluded from viable circuits, but are forced to "fulfil the expectations and responsibilities normally carried by the minister's wife. In a black context, this would include chairing the Women's Manyano, attending conventions, superintendents' consultations and the Ministers' Wives Retreat" (Williams and Landman 2016, 159). Article 9.4 of the Manyano Constitution specifies that "the wife of the local Minister, being a member of the Manyano, shall be the Chairwoman of the Branch, and all other Ministers' wives who worship in the same Society shall also form part of the Branch Executive Committee provided that they are members of the Manyano" (Manyano Constitution 2017, 3). This puts the authority to lead and discipline other women in the hands of ministers' wives, leaving no space for ordinary Manyano fraternity (Mkhwananzi 2002, 30-5). This means in "normal" circumstances "the wives of male ministers automatically become leaders of the Women's Manyano and the Young Women's Manyano organisations" (Dlamini 2017, 7). Wives of ministers have the honour of paid annual retreats and such honorific titles as "Mfundisikazi or Mongamelikazi while spouses of female ministers do not have a term to be addressed with" (Dlamini 2017, 7). In this way, the church has maintained Wesley's notion of denying women the "right to elect their representatives" (Madhiba 2010, 77). Wesley's equivalence of SCC-the class-was led by men (Hinfelaar 2001, 44). At the fortieth anniversary of the ordination of the first woman, only "4% of our superintendents are women, and no women are Bishops" (Methodist Church of Southern Africa 2016 as quoted in Williams and Landman 2016, 160), because the Synod of 2016 "still elected male bishops and even in Districts where there was a female candidate" (Methodist Church of Southern Africa 2016 as quoted in Dlamini 2017, 6). Some circuits even loathed being ministered by female clergy.

Discussion

The first cause for the funnel representation of guild women appears to be male clergy, with overwhelming patriarchal authority to vary or ignore agreed procedures (CCL 2013, 148; Catechism of the Catholic Church 1994, 511; Dlamini 2017, 6). The Catholic executive councils have no power beyond being advisory, which leaves the celibate clergy with the authority to action or reject such advice. The learned members of the guild of St Anne expected to be the torch-bearers for the rest; they noted that their constitution tethers them to the SCCs, forcing them to elect males as key advisors of the clergy in higher councils. They find it a misnomer to spend hours on end with celibate priests, which they fear may attract insipient scandals. They would rather live quietly with their families at home, being honoured and respected by their communities (Hinfelaar 2001, 39). Besides, their motto: "Better hearts, better homes, better fields" deploys them to the home loci without delegation, for the flourishing of the family (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 1, 2). The guild constitution is definitive that the locus of their activities is the homestead, as bluntly stated: "It is blessed that you be at home with your family most of the time" (Nzanga yaAnna Musande 1986, 36). This tethering explains how an electoral college of 37 women against 12 men disenfranchises all the women from participating in the next round of elections (deanery level). The article tethering the women to their families for the attainment of "great respect" shows overt forms of gender insensitivity within the church, since the clergy determine what has to be "included or excluded" from guild constitutions (Plaatjies-Van Huffel 2019, 3). In reference to Manyano/Ruwandzano and Chita cha Maria, Hinfelaar (2001, 44) notes that "the missionaries formulated these prayer movements by writing their constitutions and incorporating them into the church." Hinfelaar (2001, 50-53) further notes that the sodalities' constitutions were highly infused with "domesticity" and specific uniforms as marks of "respect," "civilisation" and "discipline."

A learned member of St Anne guild vouchsafed that she was once chosen as secretary of St Matthew's Parish, but many fellow guild members could not take it because they thought her composure was meant to attract the priest, which forced her to hand over the announcement of the notices to her male deputy. In a similar manner, Plaatjies-Van Huffel (2019, 5) experienced a parish schism "because 120 congregants, mostly women, refused to accept the leadership of a woman minister," but Plaatjies-Van Huffel soldiered on and moved from strength to strength. The Catholic women, however, continue to cringe, rather than boldly move ahead. Manyano/Ruwadzano women equally fail to challenge the authority of the minister controlling them through his wife, who leads by right of constitutional provision and not competence. Both groups are humbled by a double-edged sword of culture and male authoritative clergy (Manyano Constitution 2017, 3).

The woman is "content" to remain at home because of musha mukadzi (she gives essence to the home). In that sense the women remain unheard, since they mainly operate without men at the grassroots (home/household churches) and get overwhelmed by men in councils that advise the major decision makers. Edet and Ekeya (1988, 4) absolve the women by putting the blame squarely on men: "The present malaise in the church might be due to the fact that it has refused to allow women to function normally in the church but has reduced them to all-purpose workers, for example, fund-raisers, and rally organisers. As such, the feminine image of God is overshadowed and is not utilised by the church or by humanity in most cases." This statement must be read in light of the guild women being the key fundraisers in the SCCs, with insignificant, peripheral representation in key recommendatory church bodies. When there are economic challenges, like the current hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, the few women are the first to default from council meetings, muzzling out the feminine voice for good. The treasurer sends them travel and subsistence money in local currency, which has to be changed into foreign currency (as demanded by transporters) at the "black market" where only "indecent women" can venture. For the love of reputation, the guild women offer flimsy reasons for not being able to attend; including ill-health, or some all-important family occasion in which their roles are key.

Women are often viewed as perpetually infantile, and consequently incapable of leadership. This exclusion has a gender bias, since women are the key originators and administrators of temporal goods sustaining the parishes. For Plaatjies-Van Huffel (2019, 3), gender bias is seen in "social roles allocated respectively to women and to men in particular societies and at particular times," irrespective of capability. The church has deliberately allowed women to dominate the level of resource mobilisation, which has no voice in policy formulation, a kind of structural exploitation. This is despite the fact that in Genesis 1:26-27 God gives dominion to both man and woman without gender discrimination (Scott 2011, 47). Gender discrimination is inadmissible on the basis that the Godly nature is shared equally by both males and females (Cowles 1993, 170). It is, therefore, necessary to emphasise those texts that recognise gender equality as Galatians 3:28, as well as those that advance joint ministry, such as Romans 16:1-2; Philippians 4:2-3; Acts 16 and Matthew 25:1-3. The inclusive ministerial texts may help salvage the place of women in lay administration in Zimbabwe. Cowles (1993, 173) suggests that emphasis on the original sin has created a major dent in the advancement of women in their quest for leadership in the various churches. This is particularly true for the Roman Catholic Church, whose major scholars, St Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, have made it an indelible mark of everyone born of woman; a condition that makes all humanity arrive in the world with a tendency towards sin (Chimhanda and Matikiti 2011, 53). Oduyoye reads the riot act upon the myth of the original sin, which is often combined with the spare-rib myth: "Christians have held on to the 'spare-rib myth' and 'apple myth' of the making of a woman and used its disempowering interpretations to do untold violence to the humanity of women" (Oduyoye 2007, 8).

More so, even religious nuns are counted among the laity and are omitted from the church hierarchy. In order to achieve a stable octet, there is a need for the serious deconstruction of such mentalities which tether women at home as beasts of burden (Dube 2019, 293; Oduyoye 2001, 17). It is unfortunate that "women are too ready to submit, thus neglecting initiative and leadership. In the pastoral work of the church, these attitudes ... would be enhanced by the priestly-hierarchical mentality that sees women as only fit to receive and obey" (Baur 1994, 265). The tendency towards obedience may explain why they are entrusted with securing the temporal goods for the church, which otherwise their male counterparts could abuse. Segundo, a Jesuit cleric, observes that one way to overcome this hurdle of female exclusion, is to note that "each new reality obliges us to interpret the Word of God afresh, to change reality accordingly, and then to go back and reinterpret the Word of God again and so on" (Segundo 1976, 41). This is only possible if we adopt the fickle hermeneutic circle, which effects timely changes to biblical interpretations as situations demand them. Plaatjies-Van Huffel (2017, 87), while noting some positive public posturing in the church, observed there was still a lot to be done to achieve gender parity. In her opinion, "in order to go forward, we should reflect on the acceptance of women ... in leadership positions of the church" (Plaatjies-Van Huffel 2019, 20). This statement comes in the wake of the realisation that there are "tremendous obstacles as they seek to lead the twenty-first century church" (Mazak 2016, iv). The Methodist Church example has shown that having women priests is not a panacea to female acceptance into leadership. More so, it is not possible to liberate them in the church without paying attention to their simultaneous liberation in society (Fiedler and Hofmeyr 2011, 39).

Conclusion

The research has noted the funnel representation of women in the executive structure of lay committees of the Roman Catholic Church in Zimbabwe, with the open end of the funnel within the grassroots SCCs, and the tip-end in the national executive. It has further noted that in the absence of women of Plaatjies-Van Huffel's calibre, Catholic guild women actually participate fully in their own disenfranchisement. The St Anne-Manyano/Ruwadzano comparison has shown that the problem goes beyond wholly male celibate clergy in the Catholic Church. The Wesleyan Methodist Church of Southern Africa has its women sodality equally disfranchised, despite the presence of women clergy in its ranks-who are themselves equally stifled. The problem here is gender, whose explanations are context based. For Catholics, the merging of biblical patriarchy in support of an all-male clergy with the traditional patriarchy-brought into the church orbit on a silver platter by inculturation-colludes to elbow guild women out of leading roles. The leading male clergy ratify guild constitutions that keep women in low profile positions, by making them vow to keep precepts prescribing the home loci, as against competing for top posts in the church. To begin with, women must say "no" to proscribing constitutions that keep male clergy controlling at all levels as spiritual advisors for Catholics, or through their wives for the Methodists. Acceptable constitutions must incorporate "transparency, integrity, fairness, equality and accountability" as a roadmap for achieving results based on fair representation on important pastoral councils (White 2020, 2).

References

Banana, C. S. 1996. Politics of Repression and Resistance: Face to Face with Combat Theology. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Barr, F. C. 1978. Archbishop Aston Chichester 1879-1962: A Memoir. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Baur, J. 1994. 2000 Years of Christianity in Africa: An African Church History. London: Paulines. [ Links ]

Burke, R. L. C. 2007. "The Blessings of Being a Public Association of the Faithful." The Tilma. Summer. Accessed July 22, 2020. https://mariancatechist.com/about/the-blessings-of-being-a-public-association-of-the-faithful/. [ Links ]

CADEC. 1992. A Self-reliant Church. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Chimhanda, F., and Matikiti, R. 2011. Systematic Theology 1. Harare: Zimbabwe Open University. [ Links ]

Code of Canon Law. 2013. Code of Canon Law: The only English Edition Updated up to Motu Proprio Magnum Principium. Nairobi: Paulines. [ Links ]

Cowles, C. S. 1993. A Woman's Place? Leadership in the Church. Kansas City: Beacon Hill Press. [ Links ]

Dlamini, N. 2017. "Ordination of Women to the Ministry of Word and Sacraments: A Turning Point in the History of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 43 (3): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/3162. [ Links ]

Dube, E. 2019. "The Ass-load: A Symbolic Re-appraisal of the Bible and Gender Troubles in Africa." In The Bible and Gender Troubles in Africa-BiAS, edited by J. Kügler, R. Gabaitse and J. Stiebert, 293-308. Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press. [ Links ]

Edet, R., and Ekeya, B. 1988. "Church Women of Africa: A Theological Community." In With Passion and Compassion: Third World Women Doing Theology, edited by V. Fabella and M. A. Oduyoye, 1-13. Maryknoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Fiedler, R. N., and Hofmeyr, J. W. 2011. "The Conception of the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians: Is it African or Western?" Acta Theologica 31 (1): 39-57. https://doi.org/10.4314/actat.v31iL3. [ Links ]

Frederiks, M. 2002. "Review of Respectable and Responsible Women: Methodist and Catholic Women's Organisations in Harare, Zimbabwe (1919-1985)" by Marja Hinfelaar. Exchange 31 (2): 200-201. [ Links ]

Gaitskell, D. 2002. "Whose Heartland and which Periphery? Christian Women crossing South Africa's Racial Divide in the Twentieth Century." Women's History Review 11 (3): 375394. https://doi.org/10.1080/09612020200200327. [ Links ]

Haddad, B. 2004. "The Manyano Movement in South Africa: Site of Struggle, Survival, and Resistance." Religion and Spirituality, no. 61: 4-13. [ Links ]

Hinfelaar, M. 2001. Respectable and Responsible Women: Methodist and Roman Catholic Women's Organisations in Harare, Zimbabwe (1919-1985). Zoetermeer: Uitgeverij Boekencentrum. [ Links ]

Hlatshwayo, B. G. 1997. "Understanding Christian Conversion in a Black Township Parish." MTh. diss., University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Knitter, P. F. 1985. No Other Name? A Critical Survey of Christian Attitudes Toward the World Religions. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Lumen Gentium. 1967. In The Documents of Vatican II, edited by W. M. Abbot, 56-65. London: Geoffrey Chapman. [ Links ]

Madhiba, S. 2010. "Methodism and Public Life in Zimbabwe: An Analysis of the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Zimbabwe's Impact on Politics from 1891-1980." DPhil. diss., University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Marimazhira, X. S. 1998. Tsanga ye Masitadhi: Rungano rweNzangayaAnna Musande (The Mustard Seed: The Story of the Guild of St Anne). Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Manyano Constitution. 2017. Accessed October 24, 2020. http://clients.wikidigital.co.za/mcosa/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Womens-Manyano-1.pdf. [ Links ]

Masvingo Diocese. 2007. Parish/Mission Pastoral Constitution. Masvingo: Pastoral Communications. [ Links ]

Mazak, V. 2016. "A Call to Excellence: Leadership Training and Mentoring Manual for Women in Ministry in the Twenty-First Century." DPhil. diss., Liberty University. [ Links ]

Mkhwananzi, F. S. 2002. "Mission and the Role of the Women's Manyano Movement in the Methodist Church of Southern Africa 1907-1997." MTh. diss., University of Durban. [ Links ]

Moss, B. A. 1988. "Holding Body and Soul Together: Utilizing Women's Options in a Changing Zimbabwean Society." University of Zimbabwe History Department, Paper no. 74: 1-29. [ Links ]

Ngcobo. G. N. 2017. "The Evangelisation of the Catholic Church in Southern Africa: Community Serving Humanity." MTh. diss., University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Nzanga yaAnna Musande. 1986. Nzanga yeMadzimai echiKatorike yaAnna Musande (The Guild of Catholic Women of St Anne). Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Oduyoye, M.A. 2001. Introducing African Women's Theology. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Oduyoye, M. A. 2007. "Culture and Religion as Factors in Promoting Justice for Women." In Women in Religion and culture: Essays in Honour of Constance Buchanan, edited by M. A. Oduyoye. Ibadan: Oluseyi Press. [ Links ]

O'Halloran, J. 2002. Small Christian Communities: Vision and Practicalities. Dublin: The Columba Press. [ Links ]

Paul, J. II. 1995. The Church in Africa: Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation Ecclesia in Africa of the Holy Father John Paul II. Nairobi: Paulines. [ Links ]

Pelton, R. S. 2002. "North America (USA and Canada)." In Small Christian Communities: Vision and Practicalities, edited by J. O'Halloran, 174-183. Dublin: The Columba Press. [ Links ]

Plaatjies-Van Huffel, Mary-Anne E. 2017. "Acceptance, Adoption, Advocacy, Reception and Protestation: A Chronology of the Belhar Confession." In Belhar Confession: The Embracing Confession of Faith for Church and Society, edited by Mary-Anne E. Plaatjies-Van Huffel and L. Modise, 11 -96. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781928357599. [ Links ]

Plaatjies-Van Huffel, Mary-Anne E. 2019. "A History of Gender Insensitivity in URCSA." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 45 (3): 1-22. https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6250. [ Links ]

Scott, M. 2011. "For such a Time like this: Liberation for All through Christ." Accessed July 10, 2020. http://www.ebay.com.au/itm/. [ Links ]

Segundo, J. L. 1976. The Liberation of Theology. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

White, P. 2020. "Review of A Wild Donkey Has no Bands" by Selaelo Thias Kgatla. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 46 (2): 1-2. https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6696. [ Links ]

Williams, D. and Landman, C. 2016. "The Experiences of Thirteen Women Ministers of the Methodist Church of Southern Africa." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 42 (1): 159-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/2016/1099. [ Links ]