Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.47 n.1 Pretoria 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/8933

ARTICLE

The Apocryphal Paul as Divided Martyr: The Rhetoric of Schism and Legitimacy in Early Christian North Africa

David L Eastman

McCallie School and Universität Regensburg, dlekodak@gmail.com; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4880-9602

ABSTRACT

Neither the epistles of Paul (authentic or disputed) nor the Acts of the Apostles address the death of the apostle, but this is a focus in the later apocryphal acts. This article examines the importance of this image of Paul as a martyr for the development of early Christianity in North Africa. Evidence from Tertullian, from texts describing the death of Cyprian of Carthage, and from the writings of Augustine, demonstrates that Paul was the model martyr for the African church. Paul's status as such became a major point of contention in the competing claims to authority and legitimacy during the Donatist Controversy. The article analyses rhetorical claims to the Pauline legacy from the Caecilianist side (the writings of Optatus of Milev and Augustine) and the Donatist side (a mosaic from Uppenna and the Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs). Each side claimed that their martyrs were the true successors of Paul, and therefore they were the true Christians in Africa.

Keywords: Apostle Paul; martyrdom; Donatist Controversy; Tertullian; Augustine; Optatus; apocryphal acts; Cyprian

Introduction

In Paul's first surviving letter to the Corinthian church,1 the initial issue he addresses is division. The Corinthians have divided into various factions: "For it has been reported to me about you by Chloe's people, my brothers, that there are conflicts among you. I mean that each of you says, 'I am of Paul,' 'I am of Apollos,' 'I am of Cephas,' 'I am of Christ.' Has Christ been divided?" (1 Cor 1:11-13). This was not the only letter in which Paul addresses Christian division, whether that be division within a community or other Christian leaders standing against him. Division was an issue that hounded Paul throughout his career and brought him deep pain and frustration.

Unfortunately, division also followed Paul after his death, for the contested reception of his legacy contributed to schism in a fierce ecclesiastical dispute that shook the very foundations of the early church in North Africa for several centuries-the so-called Donatist Controversy.

In this article, I will focus on the analysis of key textual traditions from the North African context in the third and fourth centuries. I will begin by establishing the importance of Paul as the model martyr for the African church, as shown by evidence from Tertullian, from texts describing the death of Cyprian of Carthage, and from the writings of Augustine. The article then demonstrates that Paul's status as such became a major point of contention in the competing claims to authority and legitimacy during the Donatist Controversy. The rhetorical claims to the Pauline legacy from the Caecilianist side (the writings of Optatus of Milev and Augustine) versus the Donatist side (a mosaic from Uppenna and the Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs) show that each side claimed that their martyrs were the true martyrs and successors of Paul, and therefore they were the true Christians in Africa.

While this is primarily a literary study, it contributes to the broader social historical analysis of how the sometimes disputed legacy of Paul impacted the development of early Christian identity in ways that went beyond the interpretation of his letters.

Paul as Model Martyr in the North African Tradition

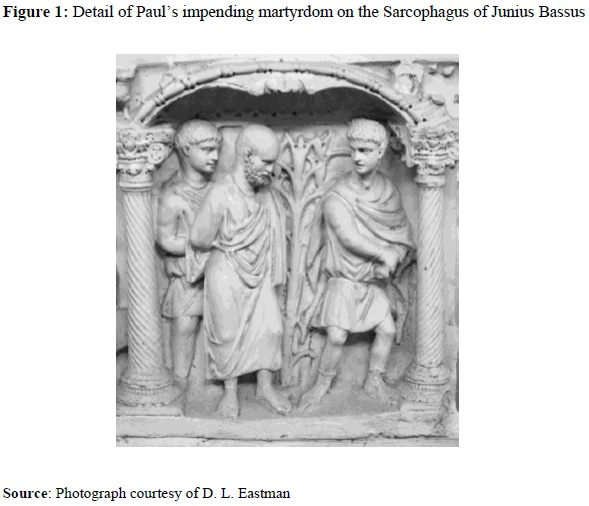

Historians recognise that persecution was not the norm for all early Christians. There was not constant or pervasive persecution, and most early persecutions were sporadic and localised-even little more than mob violence. That said, some Christians truly did suffer (see e.g., De Ste. Croix, Whitby, and Streeter 2006; Moss 2012). The apocryphal acts recount that the apostle Paul was among the first to endure martyrdom during the reign of the emperor Nero, probably between 60 and 67 CE (Eastman 2011; Eastman 2015a; Snyder 2013). There are multiple accounts of Paul's death, and they do not all tell the same story about why or precisely where Paul died (Eastman 2019); but they do agree that he was decapitated somewhere outside the city of Rome.2 While Paul was known as many things-apostle, letter writer, theologian-Eastman has demonstrated that the dominant image of Paul in the iconography of the ancient church was as a martyr. This is reflected on numerous sarcophagi, such as the famous sarcophagus of the Roman prefect Junius Bassus, who died in 359 CE [Figure 1].

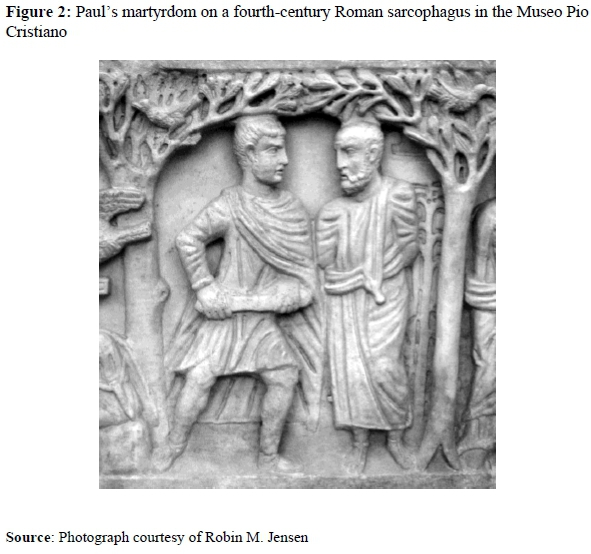

Here Paul is bound and being led away by soldiers, including one with his hand on the hilt of his sword. This scene, with some minor variations, shows up frequently in early Christianity [Figure 2], so the image of Paul bound and about to be decapitated was the primary visual image that would have come to mind when the name of Paul was evoked (Eastman 2011, 43-46).

Even in scenes where Paul is pictured without soldiers, he is often shown holding a sword-the symbol of his martyrdom. Thus, from the earliest centuries of Christianity, Paul was linked with martyrdom; and in turn, the Christian martyrological tradition was linked to Paul (Eastman 2016).

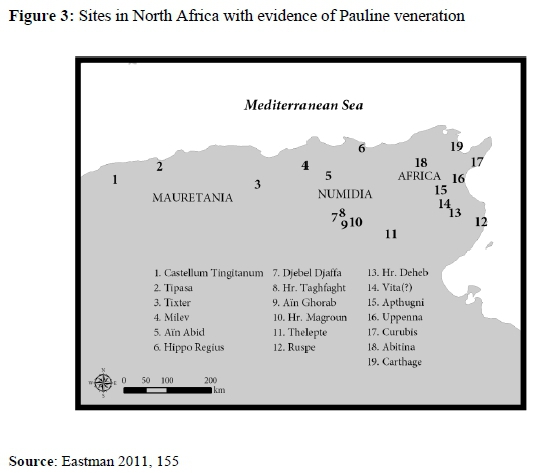

The cult of martyrs was a prominent feature of Christian piety in North Africa, a region that encompassed portions of modern Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco (Moss 2016). Christians here suffered under persecutions by the Roman imperial government in the second, third, and fourth centuries, so they felt an affinity with Paul, who had likewise been victimised by a malevolent emperor. From the large coastal cities of Proconsular Africa-Carthage, Hippo, and others-to the small towns in outlying areas of Numidia and Mauretania [Figure 3], Paul was a revered figure, honoured with churches, funerary inscriptions, relics, and other tangible, even monumental witnesses to his importance for Christian identity in the region.3

As far as we know from the sources, Paul never visited the shores of North Africa. Neither the New Testament accounts nor the apocryphal literature of ancient Christianity includes any reference to a Pauline mission in this region. Nonetheless, Paul's reputation and letters made an impact in North Africa, for he is an important figure for some of the region's most notable authors writing on martyrdom.

Tertullian was one of the most influential authors in North Africa in the early years of the third century CE, and he speaks of Paul with great reverence (Eastman 2011, 159- 60; Still and Wilhite 2013). In his work On the Prescription against Heretics, he attacks those who esteem Paul above Peter because of his superior, nobler death. This brings to centre stage the traditions surrounding the deaths of the apostles in Rome. Tertullian counters that this argument is foolish, for both apostles are martyrs and therefore enjoy equal status in the spiritual hierarchy: "Pay no attention to those who pass judgment concerning the apostles. Rightly is Peter made equal to Paul in martyrdom" (Praescr. 24.4). Paul's prominent status as a martyr was agreed upon by all; he was the standard for a martyr. Tertullian's strategy is to restore apostolic equilibrium not by tearing down Paul but by raising up Peter to Paul's level. Peter is made greater by being compared to Paul, which is a clear indication of Paul's status in Tertullian's mind.

Tertullian wrote his Antidote for the Scorpion's Sting against those Christians who, in his mind, were trying to find a way to avoid persecution by justifying the offering of sacrifice to the Roman gods. Tertullian has no patience for such apostasy and argues that martyrdom is not just a good practice but is in fact a divine command. If any doubt this, they need only look at the examples of suffering and self-sacrifice provided by the apostles: "That Peter is beaten, that Stephen is crushed, that James is sacrificed, that Paul is dragged away-these things are written with their own blood." Their sacrifice was so great that even Roman sources acknowledge it: "We read the lives of the caesars. Nero was the first who stained in blood the rising faith at Rome. Then Peter is tied around the body by another when he is bound to the cross. Then Paul obtains the birth of Roman citizenship, when in that place he is born again by the nobility of martyrdom" (Scorp. 15). Tertullian is almost certainly referring to Suetonius' Lives of the Caesars, in which the author records that Nero undertook "torture of the Christians, a class of men following a new and mischievous superstition" (Nero 16). Although Suetonius does not list the apostles by name, Tertullian assumes that they died during this persecution. Indeed, the accounts of the apostles' deaths that Tertullian would have known-as recorded in the Acts of Peter and Acts of Paul-certainly support this historical connection to Nero's reign, even if the emperor was not personally involved in Peter's execution (Eastman 2015a).4

In these treatises defending Christian belief and practice from degradation and asserting the importance, even necessity, of martyrdom, Tertullian offers Paul as a prime example. He stood firm for the faith in the corridors of imperial power at the cost of his life, even facing the famously bloodthirsty Nero. How different were some of Tertullian's opponents in his own time, "who oppose martyrdoms, interpreting salvation as destruction" (Scorp. 1). Such people failed to follow the example of Paul, who by this time was seen in North Africa as a model martyr, one worthy of admiration and imitation.

Paul stood in African thought as a model martyr, but the region's most illustrious martyr after the middle of the third century was Cyprian, who became bishop of Carthage in 248 CE and died during the Valerian Persecution in 258 CE. Several authors produced accounts of his death, and in the Life of Cyprian, the bishop is explicitly connected and compared to Paul. According to Jerome, the author of this text was a certain Pontius, one of Cyprian's deacons in Carthage (Jerome, Vir. ill. 68). Pontius adds gravity to Cyprian's story by giving the bishop an apostolic and martyrological pedigree: "Since his passion was thus accomplished, it came about that Cyprian, who had been an example to all good men, was also the first example in North Africa who drenched [in blood] his priestly crown. He was the foremost (prior) after the apostles to undertake being such an example" (Vit. Cypr. 19). Paul (along with Peter) stood as a model martyr, and Africa's foremost martyr followed his example. Cyprian stood in line behind the apostles for veneration and commemoration, yet at the same time he stood in the front of the line as "the first example in North Africa." He was, of course, not the first African martyr chronologically, but he was symbolically "first"-most prominent-because of the comparison to Paul and Peter.5

Augustine of Hippo received and promoted a similar view of Paul as a model martyr. We find this in his collected sermons, particularly those delivered for the annual celebration of the June 29 feast of Peter and Paul (Eastman 2011, 163-64; Lapointe 1972).6 In 410 CE, Augustine opens his festival sermon by acknowledging the status of Paul and Peter as martyrs: "This day has been consecrated for us by the martyrdoms of the most blessed apostles Peter and Paul. It is not some obscure martyrs we are talking about. Their sound has gone out into all the earth, and their words to the ends of the wide world. These martyrs had seen what they proclaimed; they pursued justice by confessing the truth, by dying for the truth" (Serm. 295.1).7 Paul and Peter are "not some obscure martyrs," for their fame as preachers and martyrs had spread "into all the earth" and "to the ends of the wide world." This of course included Africa itself, where Paul as a martyr was anything but obscure.

Augustine highlights Paul's status as a martyr in another sermon preached in honour of the annual feast (likely in 418 CE). Augustine sets the annual celebration in the context of 2 Tim 4:6-8, where Paul (or someone writing as Paul)8 looks forward to the apostle's looming death:

Turn your attention to the apostle Paul, because it is also his feast today. [Peter and Paul] both led lives of harmony and peace, they shed their blood in companionship together, together they received the heavenly crown, they both consecrated this holy day. So turn your attention to the apostle Paul, call to mind the words which we heard a short while ago, when his letter was being read. "I," he said, "am already being sacrificed, and the time for me to cast off is at hand. I have fought the good fight, I have completed the course, I have kept the faith ..." The just judge ... will award the crown to these merits. (Serm. 297.5)

This passage had been read earlier in the liturgy, and Augustine invites his audience to contemplate the apostle's words. Paul knew what soon awaited him, yet he faced his death with confidence, knowing that he had been faithful to the end. He was a hero of the faith, but not an irrelevant one; instead, his example rang down through the ages to inspire even Augustine's audience to higher levels of faithfulness and courage. Later in the same sermon, Augustine encourages his audience to strive for the same reward given to Paul, namely a crown: "To whom will he award it? To your merits, of course. You have fought the good fight, completed the course, kept the faith; he will award the crown to these merits of yours" (Serm. 297.6). Even though Augustine's listeners were not facing Roman imperial persecution, they still had a race to run and a battle to fight. He admonishes them to pursue these with the same vigour and perseverance as the apostle, their model in faith and, if necessary, suffering.

Tertullian, Pontius, and Augustine all portray Paul as a model martyr. This made Paul a key figure for Christian self-identity in North Africa, a region in which Christians experienced so much bloodshed over the centuries. Linking Cyprian to Paul continued the line of martyrs on their own shores, and it opened the door for others to extend this process by viewing Paul as a standard and associating later martyrs with Paul as proof of their faithfulness and legitimacy, particularly in the context of conflict.

Paul and True Martyrdom: The "Caecilianists" versus the "Donatists"

In one sense, the veneration of Paul as model martyr was a point of unity for North African Christians. On the other hand, it became contested ground for rival groups in the context of the "Donatist Controversy," the most significant ecclesiastical debate in this region in antiquity.9 The roots of this fracture within the church lay in the persecutions of the early fourth century, when the emperor Diocletian issued an edict ordering the demolition of churches and the burning of Christian books. Diocletian then issued further edicts to suppress clergy and enforce sacrifice to the Roman gods. The punishments were severe, and the clergy found themselves in a difficult situation. If faced with the option of surrendering their lives or surrendering their books, which would they choose? Some chose the latter. When the persecution abated, a split developed within the North African church concerning the fate of these traditores, "those who handed over" the books. Some said that they should be forgiven, while many others thought that the traditores had betrayed the church and were no longer fit to hold church office or ordain other clergy.

The dispute came to a head in 311 CE, when Mensurius of Carthage died and Caecilian was elected to be his successor. Many rejected him on the grounds that one of the bishops who had consecrated him, Felix of Apthugni (modern Henchir es-Souar, Tunisia), 10 was accused of being a traditor. Felix was also suspected of having conspired to prohibit aid to Christian prisoners, as we will see below. If Felix was not a legitimate bishop, as some claimed, then Caecilian's ordination was invalid, for an illegitimate bishop could not make another bishop legitimate. With the support of many bishops of Numidia, the protestors elected Majorinus as a rival bishop. Majorinus died a few years later and was succeeded by Donatus, whose followers and successors were labelled Donatists11Popular sentiment strongly favoured Donatus and his successors, but Caecilian and his successors12 enjoyed the support of the Roman church and the imperial government. For several centuries, the North African church remained divided between these competing ecclesiastical hierarchies. 13 Each had its own bishops and buildings, sometimes right across the street from each other. Augustine even tells us that his congregation in their basilica could hear singing coming from the church of their rivals (Ep. 29.11).

Martyrdom was central to North African Christian identity in general, but it was especially so for the Donatists (Dearn 2016, 70-100). They traced their movement directly to those who, like Paul and Cyprian, had faced torture or death rather than submitting to the secular government (by handing over sacred books, for example).14From 316 to 321 CE, Donatist leaders even faced persecution from a government led by an emperor favourable toward Christianity. Constantine punished them not because of their theology but because they were seen as threats to social harmony. Their movement only grew in strength. In their minds, this suffering confirmed the correctness of their position (Hoover 2018, esp. Ch. 4).

Laying claim to famous Christian martyrs like Paul as "their own" was a powerful tool in the polemics exchanged between the Donatists and the Caecilianists, and both sides cited the Pauline writings as prooftexts in their literary war of words (Frend 2000). We see this in a number of places in the literature of the time, but here I will focus on the writings of two Caecilianist bishops, Optatus of Milev and Augustine.

Bishop Optatus of Milev (modern Mila, Algeria) represents one of the prominent voices on the Caecilianist side. Between 370-374 CE, he composed six books Against the Donatists in which he defended the Caecilianists against charges levied by a Donatist named Parmenian. Parmenian had asserted that the Caecilianists were "betrayers" of the faith, but Optatus retorts that Paul had warned against people like Parmenian: "Concerning you the most blessed apostle Paul said, ' Some have turned aside to vain speech, desiring to be teachers of the law, but understanding neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertions'" (Adv. Donat. 1.28.1, citing 1 Tim 1:6-7). Optatus proceeds to bolster his attack on Parmenian by appealing to sacred sites as proof that the Donatists were the true schismatics. In previous times, some Donatists had gone to live in Rome and had unsuccessfully attempted to establish a congregation in the city:

Victor of Garba was sent first. ... He was there as a son without a father, as a beginner without a master, as a disciple without a teacher, as a follower without a predecessor, as a lodger without a home, as a guest without a guest-house, as a shepherd without a flock, as a bishop without a people. For neither a flock nor a people can those few people be called, who rushed between the more than forty basilicas in Rome, but did not have a place where they could gather. Thus, they enclosed with a wooden frame a cave outside the city, where they were able to have a meeting place right away. For this reason they are called "Mountaineers." (Adv. Donat. 2.4.4-5)15

The inability to find a home among the recognised basilicas in Rome was proof of the illegitimacy of the Donatists and their bishop. They were, therefore, forced to resort to a makeshift chapel in a cave outside the city.

Optatus adds another allegation that includes a direct appeal to the holy places of the Pauline cult. As the Donatist bishop, Victor of Garba also did not have access to the famous shrines of the martyrs: "Behold, in Rome are the shrines of the two apostles. Will you tell me whether he [Victor] has been able to approach them, or has offered sacrifice in those places, where, as is certain, are these shrines of the saints?" (Adv. Donat. 2.4.2). The Constantinian basilicas for Paul and Peter were the greatest Christian martyr monuments in the West. The Donatists were not permitted to offer sacrifice- that is, to celebrate the Eucharist-in these places, and this spatial prohibition proved that they were not true inheritors of the apostolic legacy. In the view of Optatus, this separation from Rome was indisputable evidence that the Donatists were in schism from true Christianity. The Roman legacy of Paul and Peter was the mark of "Catholic" Christianity in the West (Marone 2001, 471), and the shrines in Rome were the recognised centres of the apostolic cult. The Caecilianists alone had access to these holy sites. Therefore, in North Africa it was only their churches and monuments, not those of the Donatists, that could be legitimate centres for the Pauline cult.

Augustine, North Africa' s most famous bishop and theologian, was also firmly in the Caecilianist camp and set out to separate the Caecilianists from the Donatists. In fact, his anti-Donatist polemics have been the object of multiple recent studies (Bass 2018; Bruce 2019; Ebbeler 2012, esp. 151-90; Ployd 2015; Toczko 2020). One of his strategies was to distinguish the true martyrs of the church, including Paul, from what he considered the false, Donatist ones:

Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his just ones. Therefore the death of Peter is precious; therefore the death of Paul is precious; therefore the death of Vincent16is precious; therefore the death of Cyprian is precious. On what account are they precious? Because of a pure affection and a good conscience and a faith that is not false. That snake, however, sees this. That ancient serpent sees that the martyrs are honored and the temples are deserted. He carefully concocted cunning and poisonous plots against us, and because he was not able to wield influence over Christians by false gods, he created false martyrs. But oh you, catholic sprouts, compare with us a little those false martyrs with the true martyrs, and by pious faith discern that the devil is trying to cause confusion by a poisonous fraud. (Oboed. 16)17

Augustine opens with a short list of the West's most famous martyrs: Peter and Paul in Rome, Vincent in Spain, and Cyprian in North Africa. Although he had been critical of Cyprian earlier in his career (Dupont 2016), Augustine now includes the martyred bishop of Carthage among this illustrious group for his own polemical and political reasons. Their examples fanned the flame of the Christian faith, causing it to grow and overshadow traditional Greco-Roman religious practices. When the devil failed to undermine Christianity by reasserting the pagan gods, he created a line of "false martyrs" in order to confuse and deceive. These pseudo-martyrs were drawing away the gullible, who mistakenly thought that they were in the line of Paul, Cyprian, and others. Augustine here draws a clear distinction between "us" and "them," between those who venerate the true martyrs ("us") and the Donatists ("them"). He warns his audience to shun this "poisonous fraud." Any who want to honour true martyrs such as Paul-and the true martyrs who follow in their footsteps-should do so in the company of the true Christians, the Caecilianists.

In another sermon preached on the festival of Peter and Paul between 403 and 406 CE, Augustine again appeals to the apostles in order to distinguish the Caecilianists from the Donatists. Augustine had been under attack from Donatist sympathisers, and he takes the opportunity on this festival day to claim Paul and Peter for his side of the conflict. The bulk of the sermon focuses on separating true from false worshippers of God. Augustine then bases the summation of his argument on an interpretation and application of 2 Tim 4:6-8:

Today, brothers, we honor the memory of those who have sown the seed, through whom God exhibited what he promised to them and what he has promised to us through them. What did he promise them? "There remains for me the crown of justice, which the Lord, the righteous judge, will present on that day." ... What will the heretics [i.e., the Donatists] read aloud against these things? I think that even they celebrate the festival of the apostles. They indeed strive to celebrate their day, but they do not dare to sing this song. (Dies nat. Pet. Paul. 9)

The bishop reiterates the Caecilianist claim to Paul and Peter and asserts that his congregation could look forward to receiving their own crowns at the final judgment. The Donatist "heretics" also observe this festival day and consider themselves heirs of the promises, but their efforts are futile. Though they may "strive," they cannot sing the hymn of the true martyrs like Paul. The Donatists venerate and appeal to the apostles in vain, because the great martyrs are absent from their churches. The legitimate song of praise for the apostles, according to Augustine, rises only in the basilicas of the Caecilianists.

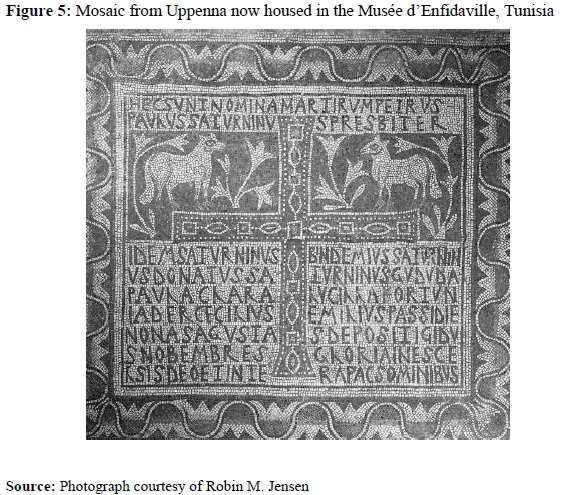

The Donatists, from their perspective, saw a clear parallel between their own plight and that of Paul. Like the apostle, they suffered persecution for their beliefs at the hands of the emperor but had not relented from their convictions. (Unfortunately for the Donatists, imperially sanctioned persecution would continue well into the fifth century.) They therefore claimed Paul, along with Peter, as their own legacy and sought to link their own martyrs-the "true" martyrs-to the apostle. This connection between the apostles and Donatist martyrs is made explicit in the dedication of a church in Uppenna (modern Henshir Fraga, Tunisia). A mosaic in the eastern apse of the basilica [Figure 5] reads: "Here are the names of the martyrs: Peter, Paul, Saturninus the presbyter. Likewise, Saturninus, Bindemius, Saturninus, Donatus, Saturninus, Gududa, Paula, Clara, Lucilla, Kortun, Iader, Caecilius, Emilius, who died and were buried on November 8" (Duval 1982, 1:63-67, no. 29; Frend 1940, 33; Monceaux 1903, 334-35).18

The original mosaic dates from the fourth century but was replaced in the sixth century by the dedication in its current form. Archaeologists have suggested that the fourth-century version included only the names of the final 13 martyrs, beginning with the second Saturninus in the list. Only these 13 were believed to be buried in the basilica. The names of the apostles and Saturninus the presbyter were added in the later mosaic as part of a renovation project. The later addition is the key to understanding how this mosaic functioned for the Donatists. A few words are in order, therefore, about the background to "Saturninus the presbyter."

The Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs19tells the story of this presbyter Saturninus and a group of Christians from Abitina, a village near Carthage (modern Chahoud el-Batin, Tunisia). According to the story, they were arrested in 304 CE during the persecution under Diocletian on the charge of performing the Christian liturgy. They were sent to Carthage, where the proconsul questioned and tortured them. He then threw them into prison and expected them to die there. At this point in the story there appears to be a later insertion by a Donatist hand.20 In this Donatist addition, when these martyrs-to-be were in prison, family members and friends came at night to bring them food and drink. They were rebuffed and beaten away not by Roman soldiers but by agents of the bishop, including a deacon named Caecilian. This was the very same Caecilian who was elected to succeed Mensurius but was rejected by the party supporting Donatus.

This modified version of the Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs becomes a story about some North African martyrs in which a Donatist hand condemns Caecilian himself for betraying other Christians. If there had been any doubt that he was illegitimate, surely the story of the Abitinian martyrs would show that he was false and corrupt. In the same story, on the other hand, is featured Saturninus the presbyter, who followed the example of faithfulness set by the apostles. Saturninus is the hero of this Donatist martyr story.

The sixth-century addition to the Uppenna mosaic was likely influenced by this altered form of the Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs. Saturninus-the Donatist hero, the one who was betrayed by Caecilian himself-stands alongside the apostles as the heir to their legacy. Paul and Peter were the greatest Christian martyrs, and Saturninus was the leader of some of the greatest Donatist martyrs.21 By extension, the 13 local martyrs buried in the church also shared in this apostolic lineage. They were connected to Saturninus because they had also given their lives to defend the true (Donatist) faith in North Africa. They represented the continuation of the Donatist line of true martyrs that went back through Saturninus to Paul and Peter. This line of succession gave the Uppenna basilica legitimacy as a holy site. As the Donatist redactor of the Acts of the Abitinian Martyrs had commented: "One must flee and curse the whole corrupt congregation of all the polluted people and all must seek the glorious lineage of the blessed martyrs, which is the one, holy, and true church, from which the martyrs arise and whose divine mysteries the martyrs observe" (Pass. Dat. Saturn. 23; trans. Tilley 1996, 45). For the Donatists at Uppenna, the true veneration of Paul took place in their church, where the "glorious lineage" of the apostles and other true martyrs was honoured, not in the churches of the illegitimate Caecilianist bishops and their "corrupt congregations," where they honoured their own false martyrs.

Conclusion

Paul was the model martyr for many African Christians. His courage, his suffering, his resolve in the face of repeated persecution-and ultimately his death for the cause of Christ-earned him a lofty place in the minds of his admirers, many of whom also sought to be his imitators. He was the epitome of what it meant to die for Christ purely and truly. This profound reverence for Paul, however, was later fashioned into a weapon, when appeals to Paul concerning "true" martyrdom took on a polemical edge in the debate between the Caecilianists and the Donatists. The Caecilianists argued that only they could claim Paul, because their bishops had been properly elected and had the support of Rome and the government. Their churches in North Africa were the only legitimate places for Pauline veneration on the annual feast days of the apostles. The Donatists countered that legitimacy came through an unbroken succession of faithful bishops and martyrs that went back directly to the apostles and was not dependent on the approval of Rome or the emperor or any other human authority. They saw themselves as standing in this line of succession. Paul belonged to them, and they invoked his name as an endorsement of their martyrs and their basilicas. Theirs were the true martyrs, heirs and successors to the apostle Paul.

References

Bass, Alden. 2018. "Ecclesiological Controversies," 145-52. In Augustine in Context, edited by T. Toom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316488409.019. [ Links ]

Bruce, Joshua Michael. 2019. "Coercive Precedents: The Place of Donatist Appeals in Augustine's Anti-Donatist Polemic." PhD diss., University of Edinburgh. [ Links ]

De Rossi, G. B. 1878-1879. "Epigrafe d'una chiesa dedicata agli apostoli Pietro e Paolo." BArC 3 (3): 14-20. [ Links ]

De Ste. Croix, G. E. M., Michael Whitby, and Joseph Streeter. 2006. Christian Persecution, Martyrdom, and Orthodoxy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199278121.001.0001. [ Links ]

Dearn, Alan. 2004. "The Abitinian Martyrs and the Outbreak of the Donatist Schism." JEH 55 (1): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022046903008923. [ Links ]

Dearn, Alan. 2016. "Donatist Martyrs, Stories and Attitudes," 70-100. In The Donatist Schism: Controversy and Contexts, Edited by Richard Miles. TTH Contexts 2. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [ Links ]

Dupont, Anthony. 2014. Preacher of Grace A Critical Reappraisal of Augustine's Doctrine of Grace in his Sermones ad Populum on Liturgical Feasts and during the Donatist Controversy. Studies in the History of Christian Traditions 177. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004278646. [ Links ]

Dupont, Anthony. 2016. "Cyprian in Augustine: From Criticized Predecessor to Uncontested Authority," 33-66. In The Normativity of the History: Theological Truth and Tradition in the Tension between Church History and Systematic Theology, edited by L. Boeve, M. Lamberigts, and Terrence Merrigan. BETL 282. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Duval, Yvette. 1982. Loca sanctorum Africae: Le culte des martyrs en Afrique du IVe au Vile siècle. 2 vols. CEFR 58. Rome: École française de Rome. [ Links ]

Eastman, David L. 2011. Paul the Martyr: The Cult of the Apostle in the Latin West. WGRW Sup 4. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Eastman, David L. 2015a. The Ancient Martyrdom Accounts of Peter and Paul. WGRW 39. Atlanta: SBL Press. [ Links ]

Eastman, David L. 2015b. "Confused Traditions? Peter and Paul in the Apocryphal Acts," 245-69. In Forbidden Texts on the Western Frontier: The Christian Apocrypha in North American Perspectives, edited by Tony Burke. Eugene: Cascade. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvz0hc01.21. [ Links ]

Eastman, David L. 2016. "Paul as Martyr in the Apostolic Fathers," 1-19. In The Apostolic Fathers and Paul, edited by Todd D. Still and David E. Wilhite. London: Bloomsbury/T & T Clark. [ Links ]

Eastman, David L. 2019. The Many Deaths of Peter and Paul. Oxford Early Christian Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198767183.001.0001. [ Links ]

Ebbeler, Jennifer. 2012. Disciplining Christians: Correction and Community in Augustine's Letters. Oxford Studies in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195372564.001.0001. [ Links ]

Frend, W. H. C. 1940. "The Memoriae Apostolorum in Roman North Africa." JRS 30 (1): 3249. https://doi.org/10.2307/296944. [ Links ]

Frend, W. H. C. 1985. The Donatist Church: A Movement of Protest in Roman North Africa, revised edition. Oxford: Clarendon. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198264088.001.0001. [ Links ]

Frend, W. H. C. 2000. "The Donatist Church and St. Paul," 91-133. In Le epistolepaoline nei manichei, i donatisti e ilprimo Agostino, 2nd edition. Rome: Istituto Patristico Augustinianum. [ Links ]

Garbarino, Collin. 2011. "Augustine, Donatists and Martyrdom," 49-61. In An Age of Saints? Power, Conflict and Dissent in Early Medieval Christianity, edited by Peter Sarris, Matthew Dal Santo, and Phil Booth. Brill's Series on the Early Middle Ages 20. Leiden: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004206595_005. [ Links ]

Hill, Edmund (trans.). 1994. The Works of Saint Augustine: A Translation for the 21st Century. Vol. III/8. Brooklyn: New City Press. [ Links ]

Hoover, Jesse A. 2018. The Donatist Church in an Apocalyptic Age. Oxford Early Christian Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198825517.001.0001. [ Links ]

Josi, Enrico. 1969. "La venerazione degli apostoli Pietro e Paolo nel mondo cristiano antico," 149-98. In Saecularia Petri et Pauli. SAC 28. Vatican City: Pontificio Istituto di Archeologia Cristiana. [ Links ]

Lapointe, Guy. 1972. La célébration des martyrs en Afrique d' après les sermons de saint Augustin. CCommChr 8. Montreal: Communauté chrétienne. [ Links ]

Maier, Jean-Louis. 1987-1989. Le Dossier du Donatisme, 2 vols. TUGAL 134-135. Berlin: Akademie. [ Links ]

Marone, Paola. 2001. "Pietro e Paolo e il loro rapporto con Roma nella letteratura antidonatista," 457-72. In Pietro e Paolo: il loro rapporto con Roma nelle testimonianze antiche:XXIXIncontro di studiosi dell'antichita cristiana, Roma, 4-6 maggio 2000. Rome: Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum. [ Links ]

Marone, Paola. 2008. "Cristianesimo e universalità nella controversia donatista," 323-35. In La natura della religione in contesto teologico. Atti del X Convegno Internazionale della Facoltà di Teologia, Pontificia Università della Santa Croce, Roma 9-10 marzo 2006. Edited by S. Sanz Sánchez. Rome: G. Maspero. [ Links ]

Masqueray, E. 1878. "Ruines anciennes de Khenchela (Mascula) à Besseriani (Ad Majores)." RAfr 22: 465-66. [ Links ]

Monceaux, Paul. 1903. "Enquête sur l'épigraphie chrétienne d'Afrique." MPAIBL 12 (1): 161- 340. https://doi.org/10.3406/mesav.1908.1092. [ Links ]

Moss, Candida R. 2012. Ancient Christian Martyrdom: Diverse Practices, Theologies, and Traditions. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Moss, Candida R. 2016. "Martyr Veneration in Late Antique North Africa," 54-69. In The Donatist Schism: Controversy and Contexts, edited by Richard Miles. TTH Contexts 2. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [ Links ]

Perlmann, Moshe (trans.). 1987. The History of al-TabarT, Volume 4: The Ancient Kingdoms. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Ployd, Adam. 2015. Augustine, the Trinity, and the Church: A Reading of the Anti-Donatist Sermons. Oxford Studies in Historical Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190212049.001.0001. [ Links ]

Ployd, Adam. 2018. "Non poena sed causa: Augustine's Anti-Donatist Rhetoric of Martyrdom." AugStud 49 (1): 25-44. https://doi.org/10.5840/augstudies20173926. [ Links ]

Shaw, Brent. 2011. Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511762079. [ Links ]

Snyder, Glenn. 2013. Acts of Paul: The Formation of a Pauline Corpus. WUNT 2/352. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [ Links ]

Still, Todd D., and David E. Wilhite (Eds). 2013. Tertullian and Paul. London: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Tilley, Maureen A. 1996. Donatist Martyr Stories: The Church in Conflict in Roman North Africa. TTH 24. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. https://doi.org/10.3828/978-0-85323-931-4. [ Links ]

Tilley, Maureen A. 1997. The Bible in Christian North Africa: The Donatist World. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Toczko, Rafal. 2020. Crimen Obicere: Forensic Rhetoric and Augustine's Anti-Donatist Correspondence. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666567223. [ Links ]

Toulotte, Anatole. 1894. Geographie de l'Afrique chrétienne: Byzacène et Tripolitaine. Montreuil-Sur-Mer: Notre-Dame des Prés. [ Links ]

1 1 Cor 5:9 tells us that 1 Cor is actually the apostle's second letter to the Corinthians: "I wrote to you in my epistle not to associate with perverse people."

2 According to Eastman (2015b, 263-64), the only exception to the decapitation story appears in a tenth-century Islamic chronicler, Abü Ja'far Muhammad b. Jam al-Tabarl: "Nero ruled for fourteen years. He slew Peter and crucified Paul head down" (Perlmann 1987, 126).

3 Many such sites have been identified in the region (Duval 1982, 1:142-18; De Rossi 1878-1879; Josi 1969; Masqueray 1878; Monceaux 1903).

4 Nero is traditionally associated with the deaths of both Peter and Paul, but this does not reflect the earliest Petrine traditions. According to the second-century Martyrdom of Peter (last section of the Acts of Peter) and the fourth-century Martyrdom of Blessed Peter the Apostle of Pseudo-Linus, Peter dies by the order of a prefect named Agrippa, and Nero learns of this only after the fact (Eastman 2019, 40-41). Cf. Tacitus Ann. 15.44, who also refers to Nero's excessive torture of Christians but does not refer to the apostles specifically.

5 See Eastman 2011 (160-2) on other comparisons of Cyprian to Paul as a model martyr in the Acts of Cyprian and the Pseudo-Cyprian text On the Glory of Martyrdom.

6 We know from the letters of Cyprian that the church in North Africa had a liturgical calendar for the martyrs at least the middle of the third century (Ep. 12.2.1; 39.3.1).

7 Augustine uses similar opening references to this festival in Serm. 297 and 299A-C. Translations of Augustine's sermons in this section come from Hill 1994.

8 Debates over the authorship of 2 Timothy are well known but not critical to our discussion here. What matters is that Augustine believed these to be the words of Paul.

9 The primary sources are collected in Maier 1987-1989. See also Frend 1985; Tilley 1996; Shaw 2011.

10 Apthugni is probably the correct form of the city's name, not Aptunga, which is typically given in secondary literature (Toulotte 1894, 264).

11 This name appears to have been given by their opponents. Shaw (2011, 5-6) settled on the term dissidents, instead of Donatists, as an attempt at more historical neutrality. However, even this term assumes that the Donatists are the ones breaking off, rather than the centre from which others diverge. Indeed, it has proven difficult for historians to agree upon value-neutral terms for the parties involved in this dispute.

12 Following Marone (2008) and Eastman (2011, 180), I will refer to this party as the Caecilianists, although they referred to themselves as "Catholics." This self-designation constituted a claim to fellowship with Rome and the broader Christian world.

13 Hoover (2018) correctly reminds us that the Donatists were not a monolithic group. There was variety of belief and practice among those labelled with that name.

14 As Tilley (1997, 155) states: "Paul, in his sufferings and patience, joins Jesus as a figure for Donatists to emulate."

15 This reference to the Donatists in Rome as "Mountaineers" also appears in Jerome (Chron. 2370) and Augustine (C. litt. Petil. 2.108).

16 Vincent was a deacon of Saragossa in Spain who died during the persecution under Diocletian.

17 Augustine has in mind the Donatists in general, but probably the Circumcellion sect in particular. Members of this group reportedly jumped off cliffs in order to make themselves martyrs. Shaw (2011, 630-721) argues that they were from the migrant farmer class, famous for its brutality and unpredictability. For other perspectives on Augustine's anti-Donatist rhetoric specifically related to questions of martyrdom, see Ployd 2018; Dupont 2014, esp. 137-98; Garbarino 2011.

18 There are two errors in the reproduction in Frend 1940: The burial date of VI idus nobembres is misprinted as IIII idus nobembres, and the final word ominibus (for hominibus) is given as omnibus. The martyrs among the 13 named Saturninus and Donatus, of course, must not be confused with the other, more famous figures by these names who were involved in the Donatist Controversy.

19 This is the common name for this account, although the Latin title is Passio ss. Dativi, Saturninipresb. et aliorum.

20 Dearn (2004) has argued that the text in its current form dates from after the Council of Carthage in 411 CE (at which the Donatists were condemned) and is perhaps a response to it.

21 Also among the Abitinian martyrs was a lector named Emeritus (Pass. Dat. Saturn. presb. 11-12). The name Emeritus is linked to the site of the apostolic basilica at Aïn Ghorab, as well as to a "memorial of the apostles" at Henchir Taghfaght near Khenchela, Algeria (Duval 1982, 1:151-54, no. 70; 1:16364, no. 77). However, Duval (1982, 1:164; 2:686-87) considers the identification of this Emeritus with the Abitinian lector "very problematic."