Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.46 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/7467

ARTICLE

Controversial Contradictions in Testimonies about Manche Masemola: The Challenge of Variability in Oral History

S Mokgoatšana

University of Limpopo, South Africa Sekgothe.Mokgoatsana@ul.ac.za https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3224-2341

ABSTRACT

This paper argues that although efforts have been made to construct Manche Masemola's martyrdom to enforce and consolidate the church's religious gains in Sekhukhuneland, her story represents a complex relation of voices that (un)wittingly contradict each other. The voices range from primary to secondary sources that continue to tell Manche Masemola's story, especially on the internet. The narrative of her martyrdom is riddled with contradictions and conflicting oral evidence. This paper explores these variations, which are a feature of oral tradition, and explains how such contradictions complicate the establishment of factual evidence based on oral history. Oral and secondary data were used, as well as available documentary materials published on various websites, to explain how these contradictions have been employed to create a religious martyr in the person of Manche Masemola. The available narratives were subjected to textual analysis, borrowing from folklore and poststructuralist literary theoretical approaches to understand the controversies embedded therein.

Keywords: variability; Manche Masemola; martyrdom; controversial; contradictions; variations; variability; testimony; oral history

Introduction

Variability is a key feature of oral narratives and tends to complicate oral testimonies in the construction of oral history. Oral historical accounts, which are products of memory, become plausible in the hands of different commentators and narrators. Each narrator moulds and recounts the story to suit the purpose and audience. Testimonies of the life and death of Manche Masemola, who died circa 1928, are characterised by such reconstructions. All the available narratives about her deal with her life and death as a special martyr in the calendar of the Anglican Church (Moffat 1928; Parker 1937). In addition, scholarly examinations of the narrative have foregrounded Manche Masemola's death except for the intertextual aspects of the narrative (Goedhals 1998; Goedhals 2000; Goedhals 2002; Kuzwayo 2013; Mokgoatsana 2019). The details of Manche Masemola's death have become the subject of debate, even as her tomb has become a shrine at which congregants gather every year. The available narratives are fraught with variations that not only contradict each other but also present a problem with the validation and reliability of the historical evidence advanced. This study explores these narrative variations, which are common in the field of oral tradition, and explains ways in which such contradictions complicate the establishment of factual evidence from oral history. Contradictory statements were extracted in order to compare them, to examine how they restate particular angles of the "truth," and to determine the extent to which they complicate the rendition of factual data.

These contradictions and variabilities have not been explored by previous research on the subject of Manche Masemola and are analysed here in terms of the contexts and audiences that shaped them. A dominant discourse on Manche Masemola is shaped by two primary archival resources to which I refer, namely a published version of the story of the then recent death of Manche Masemola by missionary wife, Mrs Mary Moffat, in 1928 in The Cowley Evangelist Magazine. I also explore the record of a later interview by the Anglican bishop in the area where Manche Masemola lived and died, namely Bishop Wilfred Parker, with Manche Masemola's cousin, Lucia Masemola, in 1937. The former seems to have recorded the verifiable facts more closely than the latter. Hospital records indicate that Mrs Moffat was an employee of the Jane Furse Memorial Hospital when Manche Masemola died in 1928. In essence, she and Fr Moeka were closer to the Manche Masemola story than any collector or commentator in the church; not discounting Lucia and Elsiena. Elsiena Masemola was a close relative to the Masemola family. Her account is not distinguishable from that of Lucia Masemola because the Bishop handles both testimonies as one, treating her as an alibi to explain Manche Masemola's persecution.

Another published version informing the Manche Masemola narrative is Maud Higham's (1937) edited book, entitled Torches for Teachers: Stories, Anecdotes, and Facts illustrating the Church's Teaching. I also analyse several Anglican Church websites that seem to project the same views as Moffat and Parker. Finally, I examine other secondary websites that seem to retell the story without regard to the earlier versions, but that generally recount the story as it is told by Mrs Moffat and Parker's recorded versions. My study focuses on the variations and contradictions, as such influenced largely by post-structuralist scholars who have shaped my understanding of intertextuality in my writings deliberately not cited here. I chose dominant Anglican Church websites such as Diocese of St Mark the Evangelist; and the Westminster Abbey websites. Other websites used to show these contradictions and variations include, but are not limited to The Politics of Martyrdom in the Context of Vatican "Politics" (Mashaba 2019). In addition, there are Makele's (2019) efforts to develop a documentary from the Manche Masemola narrative, "Baptised in Blood: Saint Manche Masemola: Documentary Idea," and other websites unrelated to the church.

Contradiction

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, contradiction refers to a fact or statement that is the opposite of what someone has said or that is so different from another fact or statement that one of them must be wrong. Contradictions, therefore, are combinations of statements, ideas or features that are opposed to one another. Something is a contraction if it is completely or somewhat different from other aspects of the case, making it difficult to determine the actuality, be it a date, place, event or even a manner of doing something. Contradictions entail propositions that offer alternative, mutually exclusive confirmations or affirmations of facts. This implies that when attempting to resolve a contradiction, the purpose of each alternative should be pursued, and the implications for meaning determined.

In the context of this article, contradictions allude to statements of fact with regard to what happened, when an event happened, how particular actions happened in a given time and place, and even the purpose for which actions happened or did not happen. I cite statements from different sources that appear contradictory, subject them to textual analysis, and compare them. This will help to determine why variable versions exist and how they complicate the narrativisation of history. In addition, it will amplify debates on the reliability of evidence and its validity in terms of known "truths" about the story.

Variability

Variability characterises all oral traditions, including oral history. Generally, if a story is told by more than one narrator, the result would be different versions. Even the same storyteller would not tell the same story in exactly the same manner as before, with variations that include, but are not limited to, content, mimicry, gesticulation and facial expression. All these aspects are important textures of the historical text that are missed when the text is presented in print form, and are often ignored in interpretations.

Something is variable if it represents a version of something and does not pretend to be its opposite. Versions, therefore, represent variations in form, content or structure, or genre, but do not move away from what is considered to be the original. Adger (2006, 1) aptly defines variability as follows:

What does it mean for something to be variable? The usual notion is that a single unit (at some level of abstraction) can come in a variety of forms; so, for example, we might think of pea-plant seeds showing variation in whether they are smooth or wrinkled, or clover varying in whether it has three leaves or four. The variation in form can be thought of as involving categories that are either discrete (how many leaves) or continuous (perhaps level of wrinkledness).

Variability means that the text that we know takes different forms, or yields versions or aspects that change from one testimony to another. Different commentators or interviewees present a common narrative that has elements that vary. These may be dates, events, actions of characters, or any other part of the main story. Ruth Finnegan (2012), a leader in the field of oral narratives, observes that oral evidence can never be handed down word for word and that each rendition will inevitably have variations. The verbatim handing down of oral tradition is impossible, so the concept of exact transmission may be misleading. She goes on to suggest that:

... many of the characteristics we now associate with a written literary tradition do not always apply to oral art. There is not necessarily any concept of an "authentic version" and when a particular literary piece is being transmitted to an audience the concepts of extemporization or elaboration are often more likely to be to the fore than that of memorization. There is likely to be little of the split, familiar from written forms, between composition and performance or between creation and transmission. A failure to realize this has led to many misconceptions-in particular the presentation of one version as the correct and authentic one-and to only a partial understanding of the crucial contribution made by the performer himself [my emphases]. (Finnegan 2012, 12)

This view presents oral historical narratives as necessarily variable, in which each piece becomes a product of the narrator's composition and extemporisation. Each rendition, therefore, becomes a reworking of another as the narrator extemporaneously creates a new narrative for a new audience and/or purpose. No rendition is expected to be the same as any other although it recreates the same proto-form, with various versions. Archival records emanating from oral sources have the same potential to vary from one interviewee to another and at times from the same interviewee after a long period following the event. Junod (1913), an authority on Thonga lore, observes similarly that contents of oral narratives as handed down by oral transmission will change, and that this would include even the sequences of the narrative details:

... my experience leads me to think that, in certain cases, the contents of the stories themselves are changed by oral transmission, thus giving birth to numerous versions of a tale, often very different from each other and sometimes hardly recognizable. (Junod 1913, 200)

These versions in history challenge the veracity of facts and their validation. In this study, I explore such variations and attempt to explain why they are constructed and textualised, either consciously or otherwise. Specifically, I show that the core Manche Masemola narrative features the following contradictions:

a) Manche Masemola's dates: there is contradicting evidence about her date of birth and death.

b) There are conflicting testimonies regarding who killed Manche Masemola, who witnessed her killing, how and by whom she was killed, and where and how she was buried. This is summarised in a table and then analysed.

All these contradictions emanate from various renditions that purport to tell the story of a teenage martyr.

Methodology

The design of this article is poststructuralist, drawing from intertextual hermeneutics. Data for this article are drawn from a wide range of secondary data in news reports and websites. In addition, the study confines itself with archival records; print and digital. Recorded interviews constitute the grounding of the primary data, triangulated with secondary data available. As explained, I use the primary and secondary sources to explore the ways in which these variations and contradictions are employed to create a religious martyr in the person of Manche Masemola. The narratives are subjected here to textual analysis. I borrow from folklore and intertextuality; a post-structuralist literary theoretical approach to understanding fully the controversies emerging from the variations. I examine the Manche Masemola narrative(s) to reach a comprehensible understanding of her story. I also examine it in order to explore types of complexity that arise when creating a story from oral sources.

Introducing Manche Masemola

Manche Masemola is a heroine, martyr and saint of the Anglican Church. She was born circa 1913 in GaMarishane village in Makhuduthamaga Municipality. GaMarishane, geographical co-ordinates 24° 43' 0" South, 29° 44' 0" East; stands 15 kilometres from the old Jane Furse Hospital. The Jane Furse Memorial Hospital was established in 1921. Jane Furse became the fulcrum from which the Anglican Church sowed the seeds of religion. When the planting of the seeds proved difficult, GaMarishane became a fertile ground from where to catch young people, especially teenage girls; with a view to joining the Wayfarers, and eventually the Community of Resurrection.

Manche Masemola and other young people as targeted responded to Fr Moeka's teachings. Her desire to join the Anglicans courted trouble with her parents. She is reported to have suffered constant beating. Manche Masemola, who died at the age of 14, had contact with the church for only a year, 1927-1928. Her attraction to the church and her exploits to resist renouncing her culture is a story that the church treats fleetingly. The power of her story lies in her death, which is graphically described to graft a martyr out of her body. Her death is clouded in controversy which continues to attract the world's attention. She was believed to have been killed by her mother, Masegadike, who 40 years later in 1969, was eventually baptised. This incident is also a subject of debate. Manche Masemola's death was first reported by Mrs Moffat, the wife of the local priest. Several testimonies exist that account for Manche Masemola's life and death.

The village GaMarishane, a home of the Batau (of Swazi historical roots) in Makhuduthamaga, stands about 15 kilometres from Jane Furse. This village was the focal point of the church's programme to convert local people into the Anglican religion. Jane Furse, then under the overlordship of Geluks location, was no fertile ground for English power and domination, because the scars of the British invasion of Sekhukhune were still fresh. GaMarishane, just outside the diminished territorial authority of Kgolane, a descendant of Kgoloko, was relatively easier to court. That being said, it still did not make penetration easy. It is here where the St Peters church was established. They lived in the hospital property, with the Daughters of Mary at the Priory where the present-day St Marks College is situated, and shuttled between Jane Furse and GaMarishane.

Contradicting Versions Testifying Manche Masemola's Birth and Death

Although there are several versions in the public domain, the dominant discourse on Manche Masemola is shaped by Bishop Parker's interview with Lucia Masemola in 1937, and Mrs Moffat's publication of Manche Masemola's death in The Cowley Evangelist Magazine published in 1928. The Diocese of St Mark and the websites of Westminster Abbey, where Manche Masemola's statue was unveiled in 1998, seem to project the Church's dominant narrative. All other versions, as we shall show, tend to paraphrase, pastiche or parody the earlier works without regard to their factual accuracy.

Whereas I accept that Manche Masemola's date of birth is an approximation, it is unthinkable that a person may have variable dates of birth or death without justification for the variation. It is common knowledge that local magistrate offices did not have records of births of black people at that time, but one might expect that the approximations should not differ too widely from each other. Kuzwayo (2013, 50) estimates that Manche Masemola was about 13-15 years of age when she was murdered by her parents, providing a variation of two years. The Diocese of St Mark the Evangelist explains that Manche Masemola was only 14 years old when her parents killed her because they did not understand the holy transformation in her. The BBC timeline estimates that Manche Masemola was born around 1913, which makes her 15 years old when she died. The Diocese of St Mark's estimate is also accepted by the Westminster Abbey citation commemorating Manche Masemola. The estimation of St Gregory of NYSSA Episcopal Church, however, is based on what it expresses as a fact-that she was born in 1910 and flogged to death in 1928, and that, therefore, she was 18 years old at the time of her eventful death. These various historical representations are based on memory and recollections, ushering into posterity contradictory evidence of Manche Masemola's date of birth. On the balance of probabilities, however, Manche Masemola is most likely to have been around 14 years old when she died.

Reports regarding Manche Masemola's death are also contradictory. The actual date on which she died is made plausible in the hands of whichever narrator moulds and reconstructs the events of that year. On interviewing Lucia Masemola in 1937, Parker recorded the information to hand, together with his doubts about the veracity of the testimony:

The thrashings began in October 1927 and went on till March 1928. [There is obviously some mistake here; the Cowley Evangelist Magazine's account written much nearer the time states that Manche died on February 4th; this would seem to agree with Lucia's statement that it was the New Year when the persecutions began to be bad]. (Parker 1937)

The interviewee continued to inform the bishop that Manche Masemola died on a Saturday in March. Parker did not treat her record presented to him with the respect due to a historical version handed down by a genuine "eye witness." His voice wields authority over the transmitted text. His colonial position and position in the church elevates him above reproach. There is no way that Lucia Masemola, in her position, could wrestle with the bishop for the truth. That Manche Masemola, according to Lucia, died on a Saturday in March 1928 contradicts the accepted view that she had died on 4 February of that year-which date itself also seems to be an estimation, as the Westminster Abbey site explains: "then, on or near 4th February 1928, her mother and father took her away ... and killed her" [my emphasis]. Two further dates are provided for Manche Masemola's death: the first, by The Politics of Martyrdom in the Context of Vatican "Politics " (Mashaba 2019), which states that Manche was killed by her parents on 4 February 1924 at the age of 14; and the second, two years later as described in Jordaan's (2011, 65) doctoral thesis, which quotes a message on the tombstone where Manche was buried in GaMarishane: "Masemola yo o kolobitswego [sic]£a madi a gagwe February 4, 1926. O re rapelele" (Masemola who was baptised with her blood on 4 February 1926. Please pray for us). From these testimonies, it is difficult to tell exactly in which year Manche Masemola died.

Bishop Parker interfered with Lucia Masemola's narrative rendition, subjecting it to critical validation. Rightly or wrongly, his choice of the date of death was influenced by his previous knowledge of Moffat's version of the story, which records the killing as having happened on 4 February 1928. The crossing over of voices where Lucia's testimony is corrected in the moment of collecting it and interspersed and substituted by that of Mrs Moffat, is a problem for the reliability of the handed-down historical narratives and their allomorphs (variants). Mokgoatsana (2019) claims that this juxtaposition of voices complicates the veracity of oral testimonies and subjects them to potential manipulation by those who collect them.

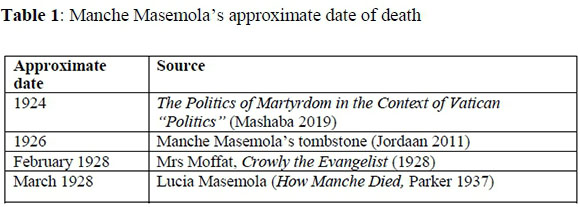

The following table shows the different versions describing Manche Masemola's approximate date of death:

The concern is that all these texts assume historical importance, hoping to represent Manche Masemola's life as honestly as possible. Religious convictions may have blinded the manner in which her history is represented. There is no evidence of effort having been made to verify facts from earlier texts by Parker, Moffat or even Higham (1937), or to give credence to earlier records; instead, each narrator has assumed the responsibility to provide a truthful account but without citing oral sources or archives. The resultant misrepresentation of historical facts, such as dates, impoverishes historical memory. In this manner, oral history is susceptible to bias or manipulation by those who reconstruct the memory of the past. Some elements of cross validation and triangulation would have assisted the narrators, especially those who chose writing as a medium to capture the past.

Parker (1937) seems to be aware of factual inaccuracies as expressed by Lucia Masemola's testimony. The story has several gaps that show Lucia's version to be a recollection over time. In addition, her version is reported as testimony by Elsiena Masemola, who at the time of telling this story, was already dead. Elsiena Masemola lived in GaMarishane during Manche Masemola's death, and her death denies us an opportunity to examine the veracity of her version. Her version and that of Lucia Masemola have become fused into one, indistinguishable unit. Parker speaks of records that seem like a single story happening at the same chronological time, and of narrative time, thus complicating distinct narratives in terms of time order and narrative time. This emphasises a distinction between chronological time and narrative time, where chronological time refers to time as it unfolds from the past to the present, and narrative time is how the story is told, how events follow each other in respect of how it is narrated, not how it happened chronologically.

This textual weaving (concept borrowed from Julia Kristeva, see Gerry Snyman [1996, 445] and Mokgoatsana [1996, 153]) is complicated by Fr Moeka's role as interpreter, narrator and a sympathetic listener to the story. Fr Moeka is a conduit for cultural imperialism and Christianisation. His testimony is influenced by what the church wants to do with the story (Moffat 1928). It is concerning that he was attached to the institution for all the years but never bothered to collect the story, even at the time when the interview was conducted by the bishop and Fr Moeka's role as the interpreter was not limited to language but also included the translation of culture. Coplan (1993, 83) acknowledges Miller's belief in the importance of social agency and process in the transmission of oral texts when he says:

Western and Western-educated interpreters are social agents themselves when it comes to the production of written transcriptions and/or translations of oral texts, and their perspectives and projects become part of the process of transmission.

This-as illustrated by the role of Fr Moeka as the interpreter of Lucia Masemola's testimony about Manche Masemola-means that the production of oral texts and transcriptions is vulnerable and amenable to distortion by interpreters. This may happen consciously or unconsciously because of the power of the colonial enterprise to give the African convert a European window onto reality. Such a gaze is shaped by what is believed to be Christian faith, even when in essence it is clothed in European wisdom. Coplan (1993, 83) further suggests that the question of who receives, recomposes and performs the history, as well as why the material is collected, is crucial in the composition of history.

Following this argument, Fr Moeka received the story in Sepedi and told it to the bishop in English. Fr Moeka fits well into Monica Wilson's description of the concept of "interpreters," who, she argues, are bilingual Christian coverts who had learnt literacy and communicative skills on mission stations and then worked as translators (Bank and Bank 2013, 7). He could sway the story in any direction because he possessed language as a tool to subvert and transform the narrative. Lucia Masemola would not be able to control how the text is being transformed because her knowledge of English, if any, is at best limited. In essence, Lucia's testimony is effectively counterpoised and recreated by Fr Moeka. Neither Lucia Masemola nor Fr Moeka was present when Manche Masemola died. Their testimony, therefore, is based on secondary reflections that are already coloured by interpretations over time.

Inaccuracies in the testimonies about Manche Masemola are a result of a story told many years after the incidents happened. Testimonies reflecting fresh memories of the time are surprisingly absent, and it is hard to understand why Lucia Masemola's version was not collected soon after her cousin's death. Memory betrays historical records, especially when the storyteller is unable to present his or her version without a translator or interpreter. Lapses of time and memory, as well as the influence of intermediaries, combine to deny history the authenticity that history pursues. These factors have largely affected meaning and reliability of the handed down recollections of the past, rendering the interpretation of historical time, facts and opinions complicated.

The timing of the collection of Lucia Masemola's story in 1937 raises fertile ground for concern about the politics of collection and the purpose for which this story was acquired. This was the year when the Anglican Church decided to commemorate a special list of eminent people. The Episcopal Synod of that year agreed to revise the list to include Mother Cecile (the Foundress of the Community of Resurrection in South Africa, in Grahamstown) and Manche Masemola (Parker 1937). The bishop's interview with Lucia Masemola was possibly conducted to legitimise a decision already taken to memorialise Manche Masemola. Since 1929, her life had already been unofficially celebrated, and pilgrimages had been organised to her tomb as a shrine. The Westminster Abbey records indicate that, in 1935, a small group of Christians had made a pilgrimage to the grave and two subsequent visits were reported in 1941 and 1949.1The bishop's fact-finding interview seems to have been timed to endorse existing pilgrimages, commonplace among local congregants; what it achieved was to expand the pilgrimage further to the external world and make them official going forward.

The construction of the physical and spiritual shrine at GaMarishane predates the church's decision on commemoration. Memorial practices connected with martyr cults in South Africa involve construction in two senses: construction of the past in the guise of remembering it, and construction of a physical shrine that is later officially built by the South African Heritage Resources Agency. In essence, Manche Masemola's grave has been a subject of commemoration and celebration long before the Anglican Church's endorsement of the pilgrimages. These celebrations memorialised Manche Masemola's life in actions and words. There is a strong possibility that Lucia Masemola's narrative is a complex set of textualisations, (re)contextualisations and multiple strands of the narrative. Silences, omissions and selective memories of the narrative are possible when the story is collected post facto 10 years later. This narrative is trapped in the politics of memory in terms of why the story is important after the fact, and what would it have mattered if the story had not been collected. The polemics of power are clear: Manche Masemola's narrative was essential to plant the seed of the church, and for that, even her mother's conversion many years later, after Manche's death, was part of that metanarrative.

Moffat's view that the church had already chosen to have a martyr rather than a murder victim complicates the veracity of Lucia Masemola's version even further (Goedhals 2000, 110). Lucia was Manche Masemola's cousin who claims to have witnessed all the beatings because she was staying with Manche Masemola's family. She was also attending hearers' classes with Manche. Standing before the awe-inspiring figure of the bishop and the priest, Lucia Masemola is likely to have retold the story to suit the needs of the hearer, both bishop Parker and Canon Moeka. Her version is not crystal clear how Manche Masemola was eventually killed. One can only infer that the constant beatings ("thrashing") may have caused her death, yet her recorded statement is not conclusive.

In Lucia Masemola's testimony, Manche Masemola's mother began to thrash her (Parker 1937). Her father used a reim while the mother thrashed her with a stick. The mother tried to pierce her with a spear in the grain hut and wanted to burn the hut with a firebrand. Another version with the detail of the spear was also included in Kuzwayo's interviews, where it was claimed that Manche Masemola hid in the barn, where the mother stabbed her several times with a spear. For her master's dissertation, Kuzwayo (2013) who is a descendant of the Masemola family, conducted interviews with Seji Mphahlele (Lucia Masemola's daughter); Mr Choshane, a retired inspector of schools, and a lay preacher at the St Peters Anglican Church in GaMarishane; Mmamating (Manche Masemola's sister-in-law); and Namane Dickson Masemola, a politician, Member of Executive Council in Limpopo, and a close relative of the Masemola family. Kuzwayo (2013) quotes Mason who proclaimed that "the more Manche grew in her faith, the more disappointed her parents became, and her mother tried to spear her and set her on fire, but she ran away." This narrative not only describes Manche Masemola as a victim but also presents her mother as a heartless assassin. Attempting to set Manche Masemola on fire is, on the face of it, bizarre and incredible. It represents a cruel, gruesome and heinous act beyond the bounds of human, let alone maternal, compassion. How a mother would have access to a spear is also questionable. The Bapedi world is sexually segregated, even in terms of the use and ownership of tools, utensils, and domestic animals. Spears in Sepedi culture represent masculine power and authority. No woman would touch or own a spear of her own, just as a man would not own brooms, calabashes, maize, sorghum, and barley. Utensils are segregated on gender lines because they are ascribable to particular chores traditionally defined by culture. As much as the woman owns and controls the barn, she would not control tools of warfare and slaughter such as assegais, shields and other weaponry.

What is not reported in all archival records and websites is the reaction of family members other than Lucia Masemola because, in the period under discussion, Bapedi lived in communes populated by related households. These households shared a common sacrificial fire. Should we conclude that they were accomplices to the attempted murder? It is unlikely that a special fire could be made to burn her alive. It is also strange that a mother could be so enraged that she would risk burning her child and her barn. The barn has cultural significance for every member of the community. Other than storing food for the current yield, the barn serves as storage for an unknown future prospect of starvation. To destroy a barn is to threaten the food security of a family and would risk exterminating her own family.

Agnes, the last surviving interviewee, told Dr Hodgson that Manche Masemola died of ill-treatment by her parents, with regular beatings especially from her mother who was especially hard on Manche (Hodgson, 1986). Higham (1937, 252) confirms the beatings-going further, suggesting that she was flogged to death. Although these beatings are reported to have happened over time, there is no record or report detailing Manche Masemola's bruises or visible injuries; this is more especially puzzling since, by that time, Bapedi clothing for girls revealed most of the torso. The absence of visible signs of the beatings on Manche Masemola's body casts doubt on the authenticity of the story, especially as the Jane Furse Memorial Hospital provided medical mission work for adjacent communities such as GaMarishane where the church had already established itself.

Kuzwayo (2013, 77) interviewed Seji Mphahlele, Lucia Masemola's daughter, in 2013, and asked her about allegations that Manche Masemola was killed by beatings. Mphahlele was asked to describe the part of the body that was struck and led to Manche's death:

I do not know, what I remember is that my mother told me that Manche was once admitted to Jane Furse Hospital, suffering from typhoid fever. I cannot confirm the dates then, because my mother does not know when that was.

Mphahlele's evidence corroborates Kuzwayo's view that declaring Manche Masemola as a martyr suggests conflicting interests that led to variations in the recorded evidence. Moffat's view was that Manche Masemola's hospitalisation could have been considered in determining circumstances around her death, but the church was determined to declare her a martyr and had, therefore, ruled out even the possibility of her being a victim of illness (Goedhals 2000, 102). Moffat, who lived on the premises of Jane Furse hospital, goes on to testify that Manche Masemola was taken ill, as many were, in the rainy season; a fact somewhat conveniently ignored by other reporters who perhaps wished to play down her illness, as detracting from her death for her faith. Moffat's view differed from that of other reporters (Goedhals 2000). These testimonies contain multiple variations that, amongst other things, craft Manche Masemola's parents as senseless murderers, and project Manche as an extraordinary human being with the capacity to withstand heinous acts of bodily violation that dehumanise her. All the texts, however, as shall be shown, present as central to the narrative of physical mutilation, the sacrifice of and violent attack on the person of Manche Masemola and her wishes, and her death at the hands of the assassins.

Lucia Masemola's testimony should be compared with other versions of Manche Masemola's story that explain how she was killed. These modes of killing vary, even if they purport to describe the same persecution and death of the same victim. The South African Broadcasting Corporation' s (SABC 3) news reported on 25 and 26 November 2017 that Manche Masemola was stoned to death by her parents. The parental "flogging" or "stoning" of their daughter in this way is horrendous and callous. Other accounts (Manyaka 2017; and Makele's 2019 blog) describe how Manche Masemola was killed with a (bewitched) hoe, while some ascribe her death to being hacked with a machete.

Manche Masemola is not only "beaten to death" (Lucia Masemola's testimony), but "hacked" with a machete (Makele's 2019 version). The narrators deliberately choose to graft Manche Masemola as a helpless victim in the hands of her parents and change the dangerous weapons to kill her as murderously as it would suit the ear of the coverts and their masters. The Manche Masemola story, like other myths that are told to support a particular belief, is told in the church's version to reinforce a commitment to faith, in line with traditional narratives about persecution and martyrdom.

Another view suggests that Manche Masemola died because a spell had been cast on her or because she had been made to drink a poisonous concoction. An anonymous writer on Makele's 2019 blog dismisses the popular view that Manche Masemola was killed by her parents, but suggests that she died as a result of witchcraft.2 This writer claims to have obtained this version of the story from his father (1929-2009) and from his two aunts (born in 1915 and 1918, respectively, of whom the first died in 2011), all of whom grew up in the same village as Manche Masemola's mother, Masegadike:

Though Manche has gone through lot of assault by her mother, Masegadike, she did not die that way. The truth is, her mother prevented her and her sister, Mabule, one Saturday to go to church the following sunday [sic], they were helping their mother to cultivate in the field. Their mother told them that she was far behind schedule and they must help her that sunday [sic] to catch up with cultivation instead of going to church. The two girls were not in favour of that, but did not tell their mother. Late that Saturday afternoon when their mother went home, they left behind and told their mother that they would first go and fetch wood before coming home. Their mother put her hoe on the palce [sic] they are used to put and left for home. The girls remained. Instead of going to fetch wood as they promised, they continued with cultivation (hoeing). The following day their mother found that the whole field is fully cultivated and suspected that a zombi did that over the night. She looked for the girls to ask them, but they already gone to church. They put the hoes on a different place. Their mother went to a traditional sankoma [sic] to work on the girls' hoes. When the girls came back from church, they picked up their hoes which were already worked on by the sankoma and were infected with the muti, so they later died.

This version ascribes Manche Masemola's death to witchcraft, further claiming that the other girls involved also died. It does not attempt to name the girls, but common knowledge dictates that they were from the same village and were attracted to the teachings of the church. This version cannot be verified and triangulated because all the informants who held views that differed from the popular and accepted narrative are dead. Without written evidence, death becomes a veil that blurs the margins of truth and validity. Towards the end of her testimony, Lucia Masemola concludes by saying: "They went on beating her until she drank the stuff. Then she died." This introduces ambiguity; it suggests poison, and thus encourages conflicting interpretations. It is not clear from Lucia Masemola's version whether Manche Masemola died of the constant beatings to which she was subjected, or because of the "stuff" that she was compelled to drink. According to Lucia, the parents believed that Manche Masemola was bewitched and called a healer to remedy the situation and return her to the child they had always known, who respected them and their culture. The healer prescribed medicine, which Manche Masemola refused to drink, and they saw this as strange behaviour that needed corrective action. Lucia Masemola's transitional term "Then" seems to introduce an action resulting from Manche's drinking of the medicine. In this context, she died either of the "beating" or of the potion she had been forced to drink.

The various versions of Manche Masemola's death present different instruments used to kill her. These conflicting memories can be read as deliberate distortions to memorialise a heroine for the church and to demonise the community in GaMarishane. The causes of Manche Masemola's death range from the use of implements such as hoes and machetes, to physical floggings, and the use of muti to cast a spell on her fortunes. Goedhals (2000, 109) opines that the decision not to report a case of murder after Manche Masemola was killed by her parents was deliberate. She poses the question: "But why did the church not act when Manche Masemola was beaten to death? One explanation is that the church was looking for a martyr, not a murder victim." This matter, together with the failure to prosecute Masegadike-Manche Masemola's mother-demands further investigation which falls outside the scope of the present study.

Who Killed Manche Masemola?

As to who killed Manche Masemola, Lucia Masemola's testimony is unclear, not specifying who was an active participant, accomplice or accessory. In general, it has been inferred that both parents had collective responsibility for Manche Masemola's death because they were the last to be seen with her alive before they "secretly buried" her body. Whereas most testimonies (Westminster Abbey; SABC News 2017; Makele's 2019 blog; and Richard's Historical Bytes) blame both parents for the murder, some ascribe the killing largely to the mother, and some describe the community as accomplices to the crime. Richard's History Bytes goes to the extent of blaming the parents, with the father shovelling her into the grave, watched by Manche Masemola's mother and the dead girl's cousin, Lucia Masemola:

Her parents had murdered her. Her father dug his shovel into the golden soil and buried her beside a rock that would mark her grave. Her mother and a terrified cousin, Lucia, stood by. Each parent had played a role in her murder.3

Whereas Manche Masemola's parents are equally blamed for her killing, the father seems to be the active assailant responsible for the killing, preparing the ground for burial, and the actual burial, while the mother watches without mention of remorse or emotion. That Lucia Masemola is "terrified" suggests her innocence, in contrast with Manche Masemola's parents depicted as heartless and callous. In this version, Lucia and Manche are indirectly presented as blameless victims of heinous crimes committed by Manche's parents. Lucia, as a minor, witnesses the grotesque image of death and her emotions are bruised by the senseless and insensitive killing of her cousin: this is the understanding left by the church's version. While Manche Masemola's parents are generally blamed for the killing of their daughter, other versions extend the blame to community members (Sekhukhune News 2017). How this blame is transferred to the community is inexplicable, and not even contemplated by those who accuse the community.

All testimonies allude to Manche Masemola's burial. They describe its location as a "lonely place"; "a remote hillside"; and a "secret place" in the yard. The last reference should be understood within the cultural construction that is embedded in local funeral rites. In Sepedi custom, men are buried in the kraal in the front of the courtyard while women are buried in the shed housing the calves, beside the main kraal where men are buried. Women, except older ones, are forbidden to enter the kraal, which is a sacred site in the homestead. Children, on the other hand, are buried in the house. Older girls and divorced women are not allowed to be buried within the homestead but in the yard at the back. As an older girl, following Sepedi custom, Manche Masemola would suitably have been buried in the backyard as it happened. The manner in which Manche Masemola's burial, and the choice of burial site are chosen seem to be interpreted negatively to suggest that it was "hurried" and done in a "secret" place, notwithstanding the cultural decorum it followed. This story erases cultural memory, thus chosen and remembered to plant the seed of the church.

Overall, contradicting testimonies are in evidence regarding Manche Masemola's death: 1) her parents killed her, in some versions, but in other versions "other community members" were also involved; 2) the instruments involved in her death vary in the different versions, and include flogging, stoning, a machete, a spear, and a hoe.

In summary, the variations found in this study in the different versions are represented graphically in Table 2.

The Bapedi cultural milieu is constructed as a satanic world to be conquered by a strong Christian faith when the community is made to remain silent about Manche Masemola's murder, and no effort seems to have been made to hear the side of their story. Instead, the Manche Masemola story was spread all over the world without questioning even the alleged perpetrator, Masegadike, Manche Masemola's mother. Bapedi culture is maimed and butchered at the altar for religious gains. The local community is described as assassins, mercenaries, and heathens. These descriptions are constructed from a particular segment or class position. Fr Moeka occupies a class position outside the uncivilised, uneducated, heathen, and impoverished Africans who have not yet seen the light. For lack of a better description, he was a "clever Bantu" of the time. Missionaries used educated or converted Africans as interpreters and translators. Their versions became authoritative texts informing history and ethnography. They became "official" commentators for the outside world. As commentators and interpreters of the Western world, African priests, therefore, provided the connection between the two worlds, and their mediation was never perfect because it was informed by the hegemonic discourses of the West seeking domination.

In addition, other commentators taking advantage of the digital media rushed to report the life and death of Manche Masemola without regard or reference to existing archival records. Exuberance, coupled with a sense of eagerness to report on the "newly found" story, and a quick instrument to authenticate the voice of the church led these commentators to create versions that are at times antithetical to what they are intended to achieve. Instead of pursuing their proselytic zeal, their narratives bordered on questionable histories that face criticism and raise questions on the role of memory in the construction of historical narratives.

Conclusion

The paper has examined various versions accounting for Manche Masemola's birth and death. Testimonies explain when she was born, and how she was murdered. To do this, testimonies are variant, creating at times conflicting and contradictory evidence as to events related to Manche Masemola's life. As products of oral tradition, the variations are subject to variability, which is key to extemporaneous compositions, especially when reliance is on the verbal accounts rather than archival records. It has been observed that the Manche Masemola story is generally passed down by word of mouth. Although versions are closely related to the original story as captured by Bishop Parker and Mrs Moffat, the versions continually differ from one rendition to another, depending on who tells the story. These variations, which are a feature of oral tradition, explain how such contradictions complicate the establishment of factual evidence based on oral history. Although Lucia Masemola's testimony is eventually recorded in 1937, the story has been in circulation since 1928, such that many versions are competing with her version to construct a variable narrative.

The pursuit to construct a martyr in the person of Manche Masemola seems to have given rise to contradicting evidence and testimonies, which make historical memory of this young woman questionable. Commentators who focused on the theme of martyrdom tended to neglect Manche Masemola's temporal and spatial situation. As a result, little was done to understand the local community's reflections of the past or to contextualise Manche Masemola within Bapedi and their culture. Manche Masemola then, becomes a product of the English world, more than her local community.

Whereas the benefit of earlier records exists, such as Moffat and Parker's interview with Lucia Masemola, later commentators do not seem to have consulted with these versions. In addition, Lucia's testimony is never corroborated by any other participant. She was used as a window to witness and to interrogate the behaviour of the GaMarishane community outside the church.

Numerous challenges characterise the study of Manche Masemola. Commentators and researchers are not privileged with Fr Moeka's interactions and personal observations in this community. It is mainly through the voice of Elsiena and Lucia Masemola that the Manche Masemola narrative is constructed. The power to (re)formulate the narrative, transmit it in order to shape further discourse and action, lies with Fr Augustine Moeka. Fr Moeka's position in the Imperial world should not be ignored. He is the actual mouthpiece of the Church (of England). He is the interpreter of both local culture and foreign religion and culture.

Furthermore, the contradictions in the Masemola narrative help us to understand how context, audience and the narrator may be embroiled in the narrative, such that they would not be able to stand out of the text. Understanding the triad, namely place, occasion, and performer, will assist us to interpret memory and understand how complex it is to document memory, especially when the collectors of memory are connected to such a memory.

Dependence on orality for the dissemination of the "original text" defies any possibility of a transcendent text, a text from which all other origins may be traced. The burden of history and the search for an authentic text becomes cumbersome, especially when the archival record is a product of a story that was already in circulation, such that its record (in the case of Lucia Masemola's version in 1937) is not necessarily the primary text in the true sense of the word, but a weaving, a fusion, a multi-layered tapestry of previous versions in the sense Junod (1913) and Finnegan (2012) explain. This defies the historian's effort to pursue a trustworthy text which can be considered an authentic representation of the past, something to be handed down to the future, as a remnant-a relic of the historical past. To study the story of Manche Masemola is to journey into these complex relations of versions, which are produced in the hands of various narrators whose purposes for constructing and disseminating the story are not always possible to decipher. As a result, it is a challenging task to reconcile the contradictions of facts in the form of acts of persecution, manner of killing, dates, and even who actually killed Manche Masemola.

Issues of power and powerlessness cannot be ruled out in the construction and memorialisation of the text, making oral history malleable in the hands of the narrator. The role of interpreters has also shed light on their power to influence the story, both its rendition and meaning; subjecting the narrator to tactful selections and omissions.

It would be interesting to examine the versions of the Manche Masemola family, in the church and outside, to obtain a balanced view of the testimonies that are currently dominant in versioning the Manche Masemola narrative. Already from the versions of Seji Mphahlele, it has become apparent that the church narrative is challenged by family members. Perhaps, it is the reason why Kuzwayo, who is a descendant of the Masemolas, has pursued a master' s degree investigating the conflicting initiation processes that Manche Masemola was engaged in.

References

Adger, D. 2006. "Combinatorial Variability." Journal of Linguistics 42 (3) (Nov): 503-530. Cambridge University Press Stable. Accessed 26-09-2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4177007. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002222670600418X. [ Links ]

Bank, A., and L. J. Bank. 2013. Inside African Anthropology: Monica Wilson and Her Interpreters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/contradiction. [ Links ]

Coplan, D. 1993. "History is Eaten Whole: Consuming Tropes in Sesotho Auriture." History and Theory 32 (4): 80-104. https://doi.org/10.2307/2505633. [ Links ]

Finnegan, R. 2012. "Oral Literature in Africa." In World Oral Literature Series, Vol. 2. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. http://www.openbookpublishers.com. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0025. [ Links ]

Goedhals, M. 1998. "Imperialism, Mission, and Conversion: Manche Masemola of Sekhukhuneland." In Terrible Alternative: Christian Martyrdom in the 20th Century, edited by Andrew Chandler. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-08264-4844-6. [ Links ]

Goedhals, M. 2000. "Colonialism, Culture, Christianity and the Struggle for Selfhood: Manche Masemola of Sekhukhuneland, c.1913-1928." Alternation 7 (2): 99-112. [ Links ]

Goedhals, M. 2002. "A Pair of Carved Saints." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae XXVlll (1) (June): 25-53. [ Links ]

Higham, M. 1937. Torches for Teachers. Stories, Anecdotes, and Facts illustrating the Church's Teaching. [ Links ]

Hodgson, J. 1986. "Field Trip to Manche Masemola Celebrations, Sekhukhuneland." A Research Report. [ Links ]

Jordaan, J. C. 2011. "History of the Dutch Reformed Church in Sekhukhuneland." Unpublished PhD thesis. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Junod, H. A. 1913. The Life of a South African Tribe, Vol 2. Neuchatel: Imprimerie Attinger Freres. [ Links ]

Kuzwayo, M. 2013. "A Church and Culture Exploration of the Ga-Marishane Village Rite of Initiation in Contestation with the Anglican Initiation Rite of Baptism of Adults: A Manche Masemola Case Study." Master's Degree in Biblical and Historical Studies. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal. http://hdl.handle.net/10413/11215. [ Links ]

Makele, B. 2019. "Baptised in Blood: Saint Manche Masemola: Documentary Idea." Accessed September 26, 2019. https://www.desktop-documentaries.com/baptised-in-blood-saint-manche-masemola-documentary-idea.html. [ Links ]

Manche Masemola. "A Timeline." Accessed September 26, 2019. http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/re/3todiefor_man_time.pdf . [ Links ]

Manyaka, P. 2017. Martyress Manche Masemola Stage Play Set to Hit Marble Hall. http://greatertubatsenews.co.za/2017/11/23/matyress-manche-masemola-stage-play-set-to-hit-marble-hall/. [ Links ]

Mashaba, G. 2019. "The Politics of Martyrdom in the Context of Vatican 'Politics'." Accessed February 25, 2020. https://uncensoredopinion.co.za/the-politics-of-matrydom-within-the-context-of-vatican-politics/. [ Links ]

Moffat, G. N. 1928. "The Seed of the Church. A True Story from the Sekhukhuniland Mission, Transvaal. Cowley the Evangelist November: 249-251. Native Economic Commission. ... The Death of Manche Masemola." AB393f Notes of 1937. Interview ... The Cowley Evangelist Magazine. [ Links ]

Mokgoatsana, S. 1996. "Some Aspects of N. S. Puleng's Works." Unpublished MA dissertation. Pretoria: Unisa. [ Links ]

Mokgoatsana, S. 2019." Of Prophecy, Mythmaking, and Martyrdom in Manche Masemola Narrative: 'I will be baptised in my blood'." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 45 (2). [ Links ]

Parker, Wilfred. 1937. "1883-1966 (Bp. of Pretoria 1933-1950). The Death of Manche Masemola." 2l.Ts. AB393f. Wits Historical Papers. [A1][A2]. [ Links ]

Richard's History Bytes . "Telling the Stories Behind the Story of Our Faith." Accessed September 25, 2019. http://richardshistorybytes.ca/the-20th-century/the-courage-of-of-manche-masemola/. [ Links ]

Sekhukhune News. Official External Newsletter of Sekhukhune District Municipality, April 2017, 3rd Quarter 2016/17. [ Links ]

Snyman, G. 1996. "Who is Speaking? Intertextuality and Influence." NeoTestamantica 30 (2): 427-449. New Testament Society of Southern Africa Stable. Accessed 05-03-2020 03: 58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43048274. [ Links ]

"St Gregory of NYSS. An Episcopal Church. Saints by Name: Manche Masemola." Accessed on 20 May 2020. https://www.saintgregorys.org/saints-by-name.html. [ Links ]

1 www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey=commemorations/commemorations/manche-masemola

2 https://www.desktop-documentaries.com/baptised-in-blood-saint-manche-masemola-documentary-idea.html.

3 http://richardshistorybytes.ca/the-20th-century/the-courage-of-of-manche-masemola/, accessed September 25, 2019.