Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.46 n.1 Pretoria 2020

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6588

ARTICLE

Religious Artefacts, Practices and Symbols in the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Church in Zimbabwe: Interpreting the Visual Narratives

Philip MusoniI; Attwell MamvutoII; Francis MachinguraIII

IUniversity of South Africa, emusonp@unisa.ac.za; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4597-8526

IIUniversity of Zimbabwe, amamvuto@yahoo.co.uk; http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2644-338X

IIIUniversity of Zimbabwe, fmachingura@yahoo.com; http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5161-5369

ABSTRACT

This study was carried out at a time when most African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in southern Africa were busy rebranding their spirituality and theology. This rebranding was as a result of serious competition in an environment where a new church was emerging every day. Thus, we argue that, due to this religious contestation, the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN) Church has inculcated/borrowed certain religious artefacts, symbols and practices which had never been part of African Christianity in Africa. As a result, this religious movement has inculcated certain African/Islamic religious objects of faith in a bid to demonstrate inclusivism and religious tolerance. In this paper, we discuss the JMCN Church's religious artefacts, symbols and practices such as clay pots (mbiya), big clay pots (makate), the wooden staff, decorated religious flags, congregating on Fridays and the use of crescent and star as its religious symbols. Artefacts, symbols and practices are borrowed from both African Traditional Religions (ATRs) and Islam. However, what remains critical in this study, is whether the JMCN Church, after its inculcation of such African traditional religious and Islamic religious elements of faith retains the tag, "a Christian church," in the rightful sense of the traditional taxonomy of the term, "Christian church," even though the movement itself claims to be a Christian church in Zimbabwe.

Keywords: artefacts; inclusivism; spirituality; symbols; religious tolerance; theology

Introduction

Religion in its variants is a critical facet of human social culture, transcending historical epochs the world over. In the different religions, art and artefacts have been used as mantles of social interactions and identities (De Gruchy 2014). Of late, a variety of cultural artefacts has increasingly become instrumental among the variants of emerging and fast-growing African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in southern Africa, such as in Zimbabwe and South Africa. The churches are imbued with ceremonial tools that range from boldly imposing multi-coloured flags and elaborately decorated divine regalia. This also includes bangles and incised pit-fired earthenware/clay pots, which are linked to a variety of elaborately decorated altars (makirawa); exquisitely decorated gates and territories bordering the items used to cover prayer shrines. The artefacts have increasingly become vehicular modes that transcend the spiritual realm. However, limited documentation of religious practices based on interpretations of meanings associated with the use of other religious artefacts, has been done using visual analysis. Visual hermeneutics, as an alternative analytic method to archiving historical events, has not been significantly utilised in historicising religion. It embodies critical discourse that reveals the social interactions of any social grouping. This paper deconstructs the institutionalisation of selected religious artefacts that are associated with the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN) Church in Zimbabwe, which invariably seems closely related to those used in the African Traditional Religions (ATRs) and Islam. Examples of these religious artefacts and symbols alluded to in this study, include: clay pots (mbiya); small stone pebbles from sacred pools (matombo emuteuro); wooden rods from sacred trees such as the wild gardenia (svimbo yemutarara); congregating on Fridays; the use of crescent moon; and the wearing of white garments during church ceremonies. In order to engage the religious artefacts, practices and symbols in the JMCN Church, we have used some selected methods.

Methodology

The study used a hermeneutic qualitative study of social narratives by members of the JMCN Church and the interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA). IPA aims at understanding the life experiences of the participants through visual analysis of cultural products (Denzin and Lincoln 2011). We followed church protocols that included initially identifying key members deemed to be custodians of church dogmas (gatekeepers), who then helped us navigate our way to the other participants. The snowball sampling technique was then used to select the participants. Critical to the overt referral methodology was the need for triangulation to ensure the authenticity of data that we generated. A sample of the participants was drawn from the JMCN Church, which uses a variety of artefacts in their worship. Data were generated mainly through oral interviews. Visual hermeneutic analytic methodology (Tulloch 2004) was used to examine the type of artefacts, practices and symbols' origin, physical attributes, purpose, (how they are administered or utilised and the meanings attached to their use), among other issues. Hermeneutical analysis was also guided by Denzin and Lincon's (2003) semiotic narrative analysis, discourse analysis and the Foucauldian historical discourse analysis. Accordingly, data analysis was qualitative, where coding and thematic indexing were used to generate themes (Denzin and Lincoln 2003). The study discusses the JMCN Church's inculturation of central spiritual elements of ATRs and the Islamic faith into its church spirituality. Evasion of harm, informed consent, voluntary participation, privacy and anonymity were some of the ethical considerations that were employed in the study. Accordingly, names that appear throughout this study as interviewees and informants are pseudonyms.

As background to our analysis of religious artefacts, practices and symbols in the JMCN Church, it is important to present a brief history of the JMCN Church.

Formation of the JMCN Church in Zimbabwe

The JMCN Church is an off-shoot group from the original Johane Masowe Chishanu ("John of the Wilderness") Church that congregates every Friday (Musoni 2017). There are several branches of the same church which mushroomed in Zimbabwe after the death of its founder, Johane Masowe (Dillon-Malone 1978). If one enquires into the causes of continuous breakaways of this Johane Masowe Chishanu Church, the leader of the congregation, who is usually a male prophet, is accused of deviating from the original teaching of mutumwa, Johane Masowe (Sixpence Shonhiwa Masedza) (Musoni 2017). The leader started his own church (Engelke 2007). After the death of Johane Masowe, in 1973, Mudyiwa Dzangara, whose religious name was "Emanuweri," took over the leadership of the church. During the last days of his leadership, Emanuweri deviated from the teachings of Johane, by encouraging church members to drink beer and practice veneration of ancestors (Mr Pondo, interview 17/07/2018). Before he died in 1989, Emanuweri had renamed the church, from Johane Masowe Chishanu to Mudzimu Unoyera ("Sacred Ancestor Church"). This renaming of the church, to Mudzimu Unoyera Church, did not sit well with Sandros Nhamoyebonde, one of the senior disciples of Johane Masowe (Musoni 2017). Accordingly, in 1990, Sandros embarked on a religious pilgrimage, from Guruve to Chitungwiza, a district situated on the south-eastern side of Harare, the capital city of Zimbabwe (Mukonyora 2007). Chitungwiza is significant, because that is where the original name of the Johane Masowe Chishanu Church came to settle after being excommunicated from Port Elizabeth in South Africa on 7 June 1962 (Dillon-Malone 1978). Johane Masowe originally fled to South Africa to start a church, since the Rhodesian government was against this religion (Dillon-Malone 1978).

In 1990, during a prayer meeting held at the Nyatsime pool in Chitungwiza, Sandros claimed that he had seen a bright star leading the people, converting them from the brewing of beer and ancestor veneration. As a result of that vision, his name was changed to Mutumwa Nyenyedzi ("Star Angel") (Engelke 2007). However, during this time, the Chitungwiza branch had maintained the Johane Masowe Chishanu Church while the Guruve branch was now using Mudzimu Unoera. The name JMCN became popular after the death of Sandros, in July 1994. This name was popularised by Baba Antony Ndaedza of Chirumhanzu, Midlands province, during the annual muteuro ("prayer"), which took place in October of the same year when Sandros died, at the Nyatsime shrine in Chitungwiza (Musoni 2017. During that annual prayer, there arose a heated debate on who was qualified to take over the leadership of the church from the late Sandros. It was in the midst of this heated debate that Baba Antony stood up to announce that "those who want to follow Nzira, those who want to follow Wimbo and those who want to follow Micho, can do so, but the rest will follow the star" (Musoni 2017). Baba Antony further declared that the time of human leadership has gone, and it was time for the spirit, Nyenyedzi, to lead the church (Musoni 2017). This is how the Johane Masowe Chishanu Church was divided into many splinter groups, with some following Madzibaba Godfrey Nzira, who rebranded their church to be Johane Masowe Chishanu Nguvo Chena Church; some following Madzibaba Micho, who rebranded themselves into the Johane Masowe Chishanu Nguvo Tsvuku Church; some following Wimbo, who rebranded their church into the Johane Masowe Chishanu Vadzidzi Church; and some following Antony, who rebranded themselves into the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN) Church (Mr Makopa [not his real name], interview 04/04/2018). In the historical evolution of the different African churches, the role of religious artefacts, symbols, and practices has been prevalent.

Inculcated African Traditional Religious Artefacts

The JMCN Church inculcated other religious artefacts, practices and symbols to inform its church spirituality. The question raised through this study is: Can the inculcating of other religious artefacts, practices and symbols be described as inculturation, or as syncretism? The term "inculturation" is used in this study to refer to the ratio at which the JMCN Church accommodated the traditional African/Islamic religious elements of faith to the ratio it accommodated traditional Christian spiritual elements of faith to shape its church spirituality. Aylward Shorter defined inculturation as "the creative and dynamic relationship between the Christian messages and culture or cultures" (Shorter 1988, 11). Duncan contends that inculturation in church history refers to the "manifestation of the Christian message in particular cultural context" (Duncan 2014, 2). Further, Duncan defined inculturation as the process whereby cultural values are transformed through their exposure to the "Christian message" and the insertion of "Christianity" into indigenous cultures (Duncan 2014, 2). With these definitions quoted, Musoni summarised inculturation as the "baptism" of the Christian gospel into African cultures so that Christianity became an African religion without losing its global identity (Musoni 2017). Thus, the question raised throughout this article is: Does the JMCN Church's accommodation of other religious artefacts, symbols and practices make Christianity an African religion, but without losing its global identity? Or, does its inculcation and accommodation of other incompatible religious artefacts, practices and symbols turn this Christian movement into a syncretic movement falling out of the bracket of Christian churches in Zimbabwe? The following paragraph discusses the notion of syncretism.

For Oosthuizen, syncretism started very early in Christian history (Oosthuizen 1968). Syncretism is where the culture and traditions of the local people are preached to influence the Gospel, with the result that the world enters the church in an impure way (Oosthuizen 1968, 52). Thus, syncretism has been defined as a combination of two or more religious belief systems into a new system, or the incorporation into a religious tradition of beliefs from unrelated traditions (Oosthuizen 1968, 91). Syncretism can be summarised as the incorporation of incompatible spiritual elements of another religion to inform one's religious spirituality (Musoni 2017, 89). With this definition, Musoni tries to draw a distinction between inculturation and syncretism. While, inculturation is the inculcation of other religion' s compatible religious elements of faith in order to make Christianity a local religion, syncretism is the inculcation of other religion's incompatible elements of faith to inform one's religious spirituality. A comparison can be drawn between compatible and incompatible religious elements of faith. Incompatible religious elements of faith are religious elements that cannot be shared among religions as means of religious dialogue. These are the very religious elements that define and distinguish one religion's identity from other religions. For example, in Christianity such elements as belief in Jesus Christ, belief in the Bible, belief in the Trinity of God, among others, are the undisputed Christian spiritual elements of faith (Burridge 2001, 11) which cannot be inculcated by any other religion in this process of religious tolerance and dialogue.

The discourse on inculturation versus syncretism is essential, since it is factual in this global village that no religion can survive in isolation of other religions. With that in mind, religious dialogue is unavoidable. In the process of contextualising Christianity, only compatible religious elements of other religions can be inculcated to make Christianity at home in Africa. Examples to retain this Christian religious character, are: translation of the Bible into local languages (Dickson 1995, 45); accommodation of local musical instruments in church services (Mbiti 1976, 27); and accommodation of the African worldview of ancestors to explain that Jesus Christ is the "Proto Ancestor" (Bujo 2003, 113). African theologians, such as Appiah-Kubi (1979, 56), believe that AICs took a major step in contextualising Christian gospel by inculcating African spiritual elements into their church liturgies. Appiah-Kubi, who studied AICs in Ghana, observed that most AICs in Ghana, such as the Church of Christ in Africa, Church of Messiah and the Celestial Church of Christ, have made a conscious attempt to inculcate certain compatible aspects of local cultures to inform their church spiritualities (Appiah-Kubi 1979, 56). However, it is key that, while other AICs inculcated compatible African religious spiritual elements to inform their church spiritualities, the JMCN Church does it differently. The JMCN Church inculcated incompatible African traditional religious and Islamic spiritual elements to inform its church spirituality. A number of religious symbols from ATR and Islam have been inculcated by the JMCN Church in Zimbabwe.

Clay Pots

In trying to Africanise Christianity, the JMCN Church ended-up inculcating some religious artefacts, symbols and practices that are not grounded in any Christian epoch.

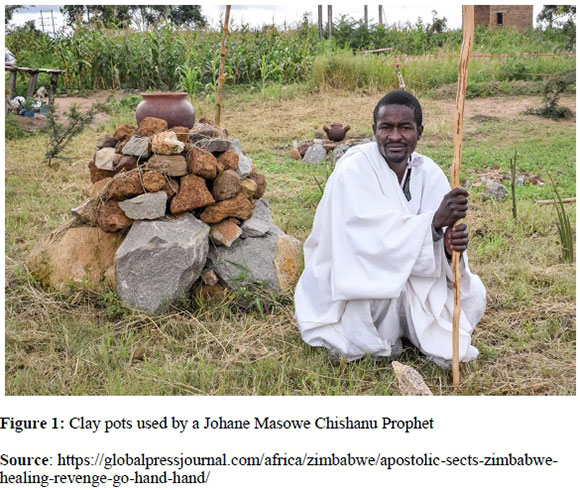

The clay pot (mbiya) was one of the common artefacts used mostly in the Masowe churches, including those in the diaspora. Figure 1 shows a Johane Masowe Church praying with a clay pot on a stone altar (Kirawa). Embracing African traditional artefacts at the level of iconological analysis, in our view was part of the JMCN Church' s attempt to Africanise Christianity.

The mbiya plays a significant role in defining the Johane Masowe Church's spirituality. The mbiya is an African traditional household utensil used either as a storage container for products such as animal blood or sacred water during Shona traditional religious ceremonies (Shoko 2011). These clay pots are made from anthill clay by old women who have passed the menstrual circles. The clay pot is fired using a pit kiln to maintain their natural aesthetic appeal. During marriage ceremonies, money for lobola is ritually put in the clay pot or on a wooden plate. Clay pots are kept at the foot of the kitchen shelf (chikuva) where plates and pots are displayed in a typical rural Shona kitchen. Chikuva is an axis-mundi where African prayers are offered (Gelfand 1982). During these traditional rituals, family elders ritually put traditional tobacco/snuff into a clay pot and kneel (pachikuva) in a bid to offer prayers to their divine (Gelfand 1982). Children are not allowed to sit in this sacred area. In some Shona communities of Zimbabwe, if a family member dies, the body of the deceased is placed pachikuva over night before burial.

Likewise, the JMCN Church members use clay pots as they offer prayers. Small stones/pebbles (nhombo), collected specifically for religious rituals, are kept in these clay pots (Dodo 2014). Using clay pots for prayers by the JMCN Church is a ritual that was borrowed from traditional African spirituality. During JMCN Church prayer meetings, all the members kneel facing east (kumabvazuva), and those with spiritual problems will be given small pebbles to use from the mbiya (Dodo 2014). Just as in a traditional African setting, water for prayers (muteuro) is also kept in these clay pots. From the interviews conducted during this study, it was noted that these pebbles and water were collected from African traditional sacred rivers (nzizi dzinorura) and pools, such as those in the Chinhoyi caves, namely the Chirorodziva, Gonawapotera, Nyatsime and Hokoyo for religious rituals (Musoni 2017).

Our interviewees, Mr Majoni and Mrs T Mazondo, intimated that "the Karanga people of Masvingo are forbidden to use metal utensils during a religious gathering but only clay pots and wooden utensils" (interview, 04/03/2018). They reiterated that "because the Holy Spirit admired our culture, our household utensils and our old way of worshipping the divine; hence, during prayers, only clay pots can be used" (Mr Svondo [not his real name], interview 04/03/2018). Besides small clay pots, the JMCN Church also uses big clay pots (makate). Big clay pots are usually non-decorated and their function and meaning can be approached at the level of iconological interpretation. These big clay pots are used for brewing beer by the traditional Karanga people of Masvingo. The JMCN Church members imitated the Karanga, who regard big clay pots as symbolising a theology brewed in an African pot. Big pots, for the JMCN Church, signify a transition from a theology cooked in Western pots to a theology brewed in an African pot (Orobator 2008). The uses and functions of traditional African artefacts seem to define the JMCN Church's attempts to Africanise Christianity. Some would take such attempts in the JMCN Church as inculturation or syncretism.

Besides big pots, they also use wooden rods.

Wooden Rods

Wooden rods are popular artefacts with the Shona. They are regarded as sacred. It is another African religious artefact believed to have been borrowed by the JMCN Church. In the Bible, there are many examples of the use of rods like the wooden rod of Aaron that buds (Numbers 17). What is interesting with the JMCN Church, is its selection of particular traditional African religious trees from which they carve the wooden rods for church rituals. The wooden rods are not crafted from every tree found in the bush. They have selected trees for that. There are four types of trees used for rods in the Masowe churches, depending on what the spirit instructs. For instance, there are rods from a traditional tree called the wild gardenia (mutarara) used by vakokeri vomweya (no equivalent English phrase). Normally in ATR, branches of the mutarara tree are used to cover graves immediately after the burial. It is believed by the Shona people, particularly the Karanga, that the mutarara branch on the grave will wade off witches or evil spirits who may want to take away the deceased's body during the night. For the Johane Masowe Church, the rod from the mutarara branch denotes the traditional concept of driving away evil spirits. Thus, the use of the mutarara rod is a borrowed phenomenon from African spirituality. Besides wading away evil spirits, the mutarara leaves are used to count the number of days after the burial. It is a common belief among the Karanga that the leaves of this tree only turn brown after 21 days of burial because the tree is believed to resist drought. It is not surprising that, for the Karanga, the body of the deceased starts to decompose after 21 days. Thus, when the mutarara leaves turn brown, it is a reminder to the community to start preparing for the doro rehonye ritual, which normally takes place after the body has decomposed. The doro rehonye ritual is done to comfort the spirit of the dead. The Karanga believe that, soon after burial, the spirit of the deceased will be meandering around the grave with the intension of inhabiting the body again. It is when the body decomposes that the spirit will start to look for new habitation. Thus, the doro rehonye is a ritual to bring the spirit back into the homestead awaiting magadziro. Once the leaves turn brown, the Karanga will conduct the first ritual after the burial, namely the doro rehonye or "bringing home" ceremony. Accordingly, the use of the mutarara, to carve the sacred wooden staff by the JMCN Church, indicates a nexus between African traditional beliefs and African Christianity. The mutatara wooden staff is used by the Masowe prophets to wade away the mweya yekumadokero ("evil spirits of the West"). The same beliefs are found in African traditional beliefs. During a JMCN Church service, the prophets will be seated facing the west, holding their hands on the svimbo yemutarara, while everybody else at the Kirawa will face the east.

Another type of a wooden rod that the Johane Masowe Church uses is the bamboo (mushenjere). According to the JMCN Church, this rod is for a specific individual according to the directives of the spirit. Unlike the mutarara, where 3-5 people will have a mutarara rod at a church service, only one person will have a svimbo yemushenjere among hundreds of congregants. This is the most sacred rod for the JMCN Church. The rod is usually held by church leaders and prophets. It is a rod that is popular with traditional leaders and healers. Before one holds that rod, there are certain expectations, rules and regulations to be adhered to in order for one to continue having such a rod. The study observed that the rod itself is made of a plant plucked from the riverbank, namely the bamboo plant. Historically, Africans from the Karanga tribe were discouraged from using the bamboo rods for firewood or any other household chores as this plant is regarded as sacred. The belief behind this practice stems from the belief that such trees are associated with water spirits. The Johane Masowe Church uses this bamboo rod as a point of contact with mysterious water spirits for curative powers. This bamboo rod is popular with African spirit mediums known for healing powers on any ailments or sickness. We find the same African beliefs being evoked in the JMCN Church-evidence of syncretic tendencies.

The third rod the Johane Masowe Church uses, is the one carved from a Mutema Masanhu (no English or botanical name could be ascertained). This tree is normally found near mountains and hills. It grows into a big tree where birds use it as protection against bad weather conditions. The tree does not bear any fruit but it is a very good sanctuary from unfavourable weather conditions. The Mutema Musanhu tree is associated with goodness and peace. One will not find any dangerous snakes in this tree. Only harmless snakes such as house snakes (shanga nyoka) can be found in this type of tree. The Karanga people of Chivi, in particular, believe that this snake represents one's immediate ancestor. For the Karanga people, ancestors are believed to take different forms, as they communicate with the living (Taringa 2014). Some Shona beliefs were meant to protect the environment from danger. Thus, the JMCN Church understands the connectedness between the living and the dead. Similarly, it is a belief within the African worldview that there exists a relationship between the dead and living people. Accordingly, every August the JMCN Church holds a three-day conference commonly known as the kupitsikwa kweMadzinza. From the interviews we gathered from six people that the purpose of this conference was to plead with the ancestors to grant permission to those who want to be members of the JMCN Church. The JMCN Church believes that unless the ancestors grant permission, anyone who wishes to be a member of this church will not enjoy the full benefits of becoming a mupositori. Thus, during this kupitsikwa kweMadzinza ceremony, all members are encouraged to seek forgiveness from their ancestors, followed by a prayer from the prophet, begging the Madzinza to accept the request. This ceremony indicates that the JMCN Church-just as in the African belief-in a way acknowledges that the spiritual world of ancestors has a bearing on the day-to-day living of its members. The JMCN Church still acknowledges and inculcates African traditional religious beliefs into their teachings.

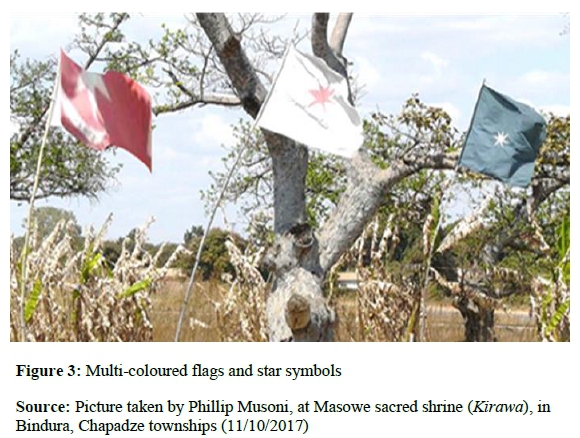

Inculcated African Religious Symbols and Practices

Apart from these artefacts, the findings of this study show that the JMCN Church had other art and symbols that are central to its spirituality. Two significant symbols are the star and a crescent (half-moon image) on church fabric and materials such as the church flag and gown. Mr Petros Chivenge and Mrs Florence Chivenge (not their real names) argue that "church flags play a significant role for JMCN spirituality as they act as antennas connecting them to the spiritual world" (interview, 04/03/2018). These flags are hoisted high above all the other objects, so as to connect to the spiritual realm. Each flag has a star image and a crescent moon printed on it. The star and crescent moon on the flag were primary symbols of the JMCN Church. The selection of the star and crescent moon symbols is an indication of the JMCN Church borrowing from African indigenous spirituality. Zimbabwean traditional beliefs have assigned religious symbolisms and meanings to images such as stars, the moon and the crescent shape.

The crescent moon is symbolic of misfortune in ATR (Mwedzi Mutete). The Shona traditional religious belief is that, when the moon is half-shaped and appears only a little; many misfortunes will happen due to spiritual warfare. The belief is that most mental disorders during this period are because of Mwedzi Mutete. According to the Shona, a star is symbolic of either fortunes or misfortunes. When an unmarried individual sees a star moving very fast, it is an indication that the individual's life partner will come from the direction the star goes. Seeing a group of stars going in a certain direction could mean that there will be a drought during the following summer. People are encouraged to prepare for it. One can, therefore, safely argue that JMCN spirituality is influenced by African traditional religious spirituality. As a result, the church's spirituality can be seen as having been brewed in an African pot by incorporating African beliefs and practices. The JMCN Church, as a Christian institution, is characterised by its contemporary approach to the integration of African traditional culture, practices, beliefs and artefacts to inform its church spirituality. The cultural tools and symbols are familiar to most members of the church, as they are derivatives from societal practices. The members even understand the meaning of the symbolic colours as regards their beliefs, practices and artefacts.

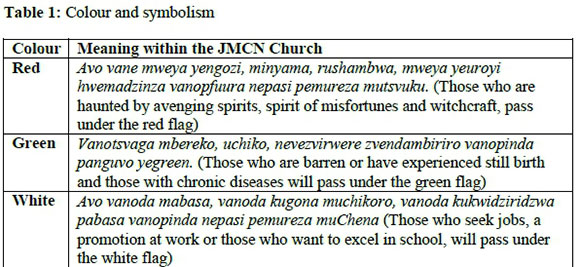

JMCN Church, Colour Symbolism

For the JMCN Church, colour plays a significant role, especially at their sacred places. Many Johane Masowe churches have mushroomed and continue to mushroom since the death of its founder, Johane Masowe in 1973 (Dillon-Malone 1978). Since the church's split, one branch is identified by their red garments, namely the Johane Masowe renguvo tsvuku; another by their white garments, namely the Johane Masowe renguvo chena; and the other by their red, white and green regalia. These colours serve to identify the church and distinguish it from the many Johane Masowe churches in Zimbabwe. In an interview, Mrs Sibanda and Mrs Choto (05/04/2018) intimated that colours such as red, green and white had deep spiritual meanings beyond identity. These colours represent four main spiritual problems that most Africans battle with during their lifetime namely: avenging spirits (ngozi), chronic diseases (zvirwere zvinorambirira), barrenness (kushaya mbereko) and misfortunes (minyama, nerushavashava).

Thus, under each flag, a prophet will be standing, dressed in the same colours as the flag, and there will be a long cloth, also in the colour of the flag, on which church members will walk as they approach the prophet.

Besides influences from ATR beliefs and practices, the JMCN Church shares or borrows some Islamic beliefs and practices, thereby making it become a syncretistic church. Our assumption is that they possibly want to boost numbers by merging religious practices and beliefs of different religions as shown through the religious artefacts, symbols and practices borrowed from Islam.

Inculcated Islamic Religious Artefacts and Symbols and Practices

The JMCN Church developed a spirituality that accommodates other religions such as Islam regarding religious artefacts, symbols, traditions and practices. Muslims pray five times a day and Masowe do the same. The JMCN Church member always starts the day with an early morning prayer, which starts at 3 am, followed by the mid-morning prayer at 9 am. After the mid-morning prayer, all the Masowe members observe the midday prayer, followed by the 6 pm prayer, as the sun goes down. After the 6 pm prayer, the JMCN Church member will pray at 9 pm, which marks the end of day prayers. Though the prayer times are different from that in the Islamic religion, their praying five times a day is borrowed from Islamic spirituality. Muslims observe prayers five times a day (Zaman and Zaman 2012). Besides praying five times a day, the JMCN Church has borrowed the Islamic attire of a full dress for both men and women during religious ceremonies. Men in the JMCN Church usually wear garments that may be worn like a dress, usually with trousers underneath. They also have a long rectangular scarf usually worn over the shoulders. All the women cover their heads and are not allowed to wear any make-up. This dress code was borrowed from the Islamic tradition. This is why, perhaps, Muslims are allowed to attend Masowe churches, regardless of them not being black Africans. Figure 4 shows Muslims in traditional attire attending a Masowe religious ceremony. A number of JMCN followers cannot tell their difference in beliefs with Muslims because of the syncretistic nature of the church teachings, beliefs, practices, artefacts and symbols.

The JMCN Church inculcated other Islam symbols such as the crescent and the star. The crescent and the star are found on their church garments and on their church flags. Besides this, like the Muslims, the JMCN Church congregates on Fridays, while most sabbatical AICs congregate on Sundays. Friday, for the JMCN Church, is sacred and holy and, therefore, members of the church are not allowed to work on Fridays since it is also their sacred day of worship. Friday is a sacred day and a holy day for Masowe churches. Most members of this church are individual entrepreneurs who shun any form of employment other than that created by them. To avoid working for organisations that will require them to work on a Friday, church members opt to make baskets (Hallencreutz 1998), or choose carpentry and tailoring for a living. This allows them to worship and attend services on Fridays.

During their prayer meetings, like Muslims, JMCN Church members are not allowed to wear shoes or use perfume. Members of the JMCN Church wear simple white garments for their church services. They also observe a month-long period of prayer and fasting annually, just as the Ramadan in Islam. The month of praying and fasting ends with what they call the muteuro wegore conference, where all those participating in the fasting and praying converge at one place to receive tsanangudzo dzegore (spiritual blessings). One can be forgiven to conclude that the month of prayer and fasting among the JMCN Church members is borrowed from the Islamic Ramadan. Another similarity that was observed was the ritual to face east during prayer. Muslims face Mecca when they pray, and the JMCN Church members always face the east during their prayer meetings. Other Christian denominations do not have particularities on which direction to face during prayer. Thus, due to its inculcation of ATR and Islamic incompatible religious artefacts, symbols and practices, the JMCN Church has transitioned from being a Christian church to a syncretic religious movement.

Inculcated Western Christian Religious Artefacts, Symbols and Practices by the JMCN Church

The JMCN Church members do not use the Bible or any other Christian books. Interestingly, there are several borrowed artefacts, symbols and practices that mimic Western Christianity. The JMCN Church uses the cross widely and avidly. The cross is seen on church garments; carved wooden crosses are placed at the door posts or entrance. During prayer, the JMCN Church members would start and close the prayer with a cross sign. This practice of a cross sign by touching the forehead, the heart and the shoulders is common practice in the Roman Catholic Church and other mainline churches. However, while these churches do the sign of the cross once, when opening a prayer, the JMCN Church repeats the cross sign thrice, in what they refer to as the michinjiko mitatu. For this church, repeating the sign of the cross three times represents their doctrine of mutumbi mitatu, the three sacred black African Masowe leaders, namely Baba Johane, Emanuweri and Nyenyedzi (Musoni and Gundani 2016).

The JMCN Church observes Easter commemorations like other Christian denominations. Easter celebrations among the JMCN Church commences on the Thursday before Easter Friday, with what they call the choto chaIsaka ("fire place for Isaac") (Musoni and Gundani 2016). Thus, every Easter, like other Christian churches, the JMCN Church converges. Though the church does not observe the crucifixion of Christ, they share stories on how God sent Johane Masowe-followed by Emanuere and then Nyenyedzi-to black Africans, to preach repentance. All these church leaders are purported to have been sent by God in the same way God sent John the Baptist and Jesus Christ (mhiri yegungwa) (Musoni and Gundani 2016).

The JMCN Church also observes sacraments such as water baptism, the Lord's Supper and children dedication, as we find in other Christian churches. What is different is that their baptism is not conducted in any pool, river or dam but only in selected pools which they regard as sacred. These selected pools are professed to be inhabited by water spirits (Njuzu) (Musoni 2016) and include pools such as the Nyatsime in Chitungwiza; the Gwehava/Hokoyo in Gokwe; and the Ndarikure pool in Chirumhanzu, which have been identified as African traditional religious sites.

Conclusion

Christian religious artefacts and symbols have taken a new form among AICs in southern Africa. The emergence of the JMCN Church has altered the face of Christianity, particularly in southern Africa. The inculcation of traditional African and Islamic religious artefacts, symbols and practices such as African traditional clay pots; wooden staffs, made from traditional sacred trees; baptising new converts in certain sacred pools such as the Nyatsime, Gwehava and Gonawapotera; the adoption of Islamic symbols such as the crescent and the star; and praying five times a day, among others, suggest that the JMCN Church has presented a disputed church spirituality. Though the church has accommodated certain Christian symbols such as the cross, praying like the Catholics by touching the forehead, chest and shoulders in the sign of the cross, wearing white robes, like most Catholic priests and observing Easter celebrations, its inculcation of most central/incompatible religious elements of ATR and Islam to a larger extent justifies why this religious movement has been categorised as a syncretic religious movement rather than a Christian church in this study.

References

Appiah-Kubi, K. 1979. "Indigenous Christian Churches: Signs of Authenticity." In African Theology En Route, edited by K. Appiah-Kubi andTorres. New York: Maryknoll, 117125. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjp.12040. [ Links ]

Bujo, B. 2003. African Theology in the 21st Century:The Contribution of the Pioneers, 1st edition. Nairobi: Paulines Publication. [ Links ]

Burridge, R. 2001. "Jesus and the Origins of Christian Spirituality." In The Story of Christian Spirituality:Two Thousand year from East to West, edited by G. Murshell. Oxford: Lion Publishing, 11 -30. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, John W. 2014. "The Quest for Identity in so-called Mainline Churches in South Africa." In The Quest for Identity in so-called Mainline Churches in South Africa, edited by Ernst M.Conradie and John Klaasen. Stellenbosh: Sun Press, 15-31. [ Links ]

Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds). 2003. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds). 2011. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Dickson, K. 1995. "Theological method." In Reiventing Christianity, edited by J. Parratt. Michigan: Wn.B.Eerdmanns, 47. [ Links ]

Dillon-Malone, C. 1978. The Korsten Basketmakers: A Study of the Masowe Apostles An Indigenous African Religious Movement. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Dodo, O. 2014. African Initiated Churches, Pivotal in Peace-Building A Case of the Johane Masowe Chishanu, Journal of Religion and Society-The Kripke Center. Accessed September 3, 2016. moses.creighton.edu/jrs/2014/2014-9.pdf. [ Links ]

Duncan, G. 2014. "Inculturation: Adaptation, Innovation and Reflexivity. An African Christian Perspective." Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies. Accessed June 11, 2015. www.hts.org.za > Home > Vol 70, No 1 2014. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2669. [ Links ]

Engelke, M. 2007. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Gelfand, M. 1982. The Spiritual Beliefs of the Shona, 2nd edition. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

Hallencreutz, C. 1998. Religion and Politics in Harare 1890-1980. Uppsala: Swedish Institute of Missionary Research. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J. S. 1976. "Christianity and African Culture." Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 10 (13): 27-38. [ Links ]

Mukonyora, I. 2007. Wandering a Gendered Wilderness: Suffering and Healing in an African Initiated Church. New York: P. Lang. [ Links ]

Musoni, P. 2016. "Contestation of the Holy Places in the Zimbabwean Religious Landscape: A Study of the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Church's Sacred Places." HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72 (1): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i1.3269. [ Links ]

Musoni, P. 2017. "Inculturated African Spiritual Elements in the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyeyedzi Church in Zimbabwe." University of Pretoria. http://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/61196/Musoni_Inculturated_2017.pdf?; https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM187303060881006. [ Links ]

Musoni, P., and P. Gundani. 2016. "Easter Celebrations with a Difference : A Critical Study of the Johane Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Approach to the Event." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 42 (1): 1-14. http://scielo.org.za/pdf/she/v42n1/02.pdf.; https://doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/2016/422. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen, G. 1968. Post-Christianity in Africa. Michigan: Wn.B.Eerdmanns. [ Links ]

Orobator, A. E. 2008. Theology Brewed in an African Pot. Mary Knoll, NY: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Shoko, T. 2011. " Shona Traditional Religion and Medical Practices : Methodological Approaches to Religious Phenomena." African Journals Online (AJOL) XXXVI (2): 277292. [ Links ]

Shorter, A. 1988. Towards a Theology of Inculturation. Mary Knoll: Orbis. [ Links ]

Taringa, N. 2014. Towards an African-Christian Environmental Ethic. Bamberg:University of Bamberg [ Links ]

Tulloch, J. 2004. "Art and Archaeology as a Historical Resource for the Study of Women in Early Christianity: An Approach for Analysing Visual Data." London: The Continuum Group. https://doi.org/10.1177/096673500401200303. [ Links ]

Zaman, A., and N. Zaman. 2012. How to Pray Salah. Canada: Institute of Social Engineering. [ Links ]

Oral material

Oral interview: 17/07/2018

Oral interview: 04/03/2018

Oral interview: 04/04/2018

Oral interview: 04/03/2018

Oral interview: 04/03/2018

Oral interview: 04/03/2018

Oral interview: 04/03/2018

Oral interview: 05/04/2018