Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.45 n.2 Pretoria 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/4493

ARTICLE

African Indigenous Churches for Black Africans: A Study of the Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN) Missiological Thrust in the Diaspora

Phillip Musoni

University of South Africa. emusonp@unisa.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4597-8526

ABSTRACT

This study is an attempt to reconstruct the missiological thrust of African Indigenous Churches (AICs) in the diaspora. It specifically focuses on a Zimbabwean church, the Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN). Today, most AICs have transitioned from being churches only for black Africans by accommodating other nationalities in their gospel economy, while outside African boarders. The best example of such African churches in the diaspora is probably the Zimbabwe Assemblies of God Africa (ZAOGA), which has transitioned from being a church only for Zimbabweans to being a global African church. By contrast, JMCN has seemingly remained a Zimbabwean church, even in the diaspora. Arguably, though JMCN has crossed Zimbabwean borders into other nations, this study maintains that JMCN in principle continues to be a black Zimbabwean church. To validate the above claim this study investigates JMCN's missiological thrust with a special focus on: how JMCN recruits church membership; how JMCN selects its sacred shrines; what language is used in JMCN-particularly in the diaspora; and where JMCN obtains sacred objects of worship such as its clay pots and wooden objects.

Keywords: African Indigenous Churches (AICs); diaspora; Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN); missiological thrust; Missio Dei; ZAOGA

Introduction

A new wave of African migrants to other continents seems to have opened the door for African Indigenous Churches (AICs) to be planted in Europe and America (Adogame 2013). According to Falola and Oyebade (2016, 27), in the 1990s Europe experienced a new wave of African immigration, particularly from central and southern Africa. This migration is rebranded as the "new wave" because the "old wave" was that of the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, which was characterised by Africans being displaced from Africa through the slave trade, and was thus involuntary (Adogame 2009, 488). However, this new wave is a voluntary move from one's country of origin in search of a better lifestyle. Today, most of these African migrations into the diaspora occur because of economic hardships in numerous African countries. Zimbabwe is one of the most economically troubled of these, in part due to the political policies of the ruling ZANU-PF party, a party which has remained in power since 1980. It is against this background that people migrate from Zimbabwe to other countries within Africa or to other continents for greener pastures. What is key in this study is the fact that African immigrants carry their religions with them into the diaspora. Likewise, AICs are becoming more and more evident in Asia, Europe and America. Against this background two Zimbabwean churches, Zimbabwe Assemblies of God Africa (ZAOGA) and Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN) have branches in other African countries and beyond. While ZAOGA demonstrated its determination to build local-global links and make non-Africans primary targets in its membership drives (Adogame 2013), this study discusses the missiological thrust of JMCN in the diaspora. The question raised in this study is: To what extent has this "African church" (JMCN) negotiated, assimilated and accommodated other nationalities, while maintaining its African identity? The phrase "African church in the diaspora" is thus used narrowly in this study to refer to any AIC founded by Africans in Africa, but now operating church branches outside its country of origin. Consequently, for one to understand JMCN's missiological thrust in the diaspora, an initial discussion on its membership recruitment drive is useful. The first section of this study offers a preamble on how ZAOGA transitioned from being a Zimbabwean/African Indigenous Church (AIC) to becoming an African International Church (AIC). Subsequently, the article discusses how JMCN's missiological thrust has prevented it from becoming an African International Church in the diaspora.

Transition from African Indigenous Church to African International Church

ZOAGA in the Diaspora

ZAOGA is one of the prominent, rapidly proliferating examples of an African church that has since crossed other borders. The church was founded by Ezekiel Guti in 1960 in Bindura township, Zimbabwe (Maxwell 2007). During this time ZAOGA was known as Assemblies of God Africa (AOGA). In 1980, when the country attained its independence which subsequently led to the renaming of the country from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe, AOGA also transitioned to become Zimbabwe Assemblies of God Africa (ZAOGA). In 1984 ZAOGA established branches in South Africa and in the United Kingdom. Consequently, in its effort to acclimatise to its new environment in the diaspora, ZAOGA was renamed ZAOGA-Forward in Faith Ministries International (FIFMI) (Adogame 2013). Outside South Africa and the United Kingdom FIFMI has spread not only to France, Portugal, Germany, Austria and Poland, but also to North America, Asia Australia and elsewhere (Adogame 2013, 273). Though FIFMI continues to have Zimbabwe as its international headquarters, the church has built centres of worship in these aforementioned countries and continents. FIFMI has also ordained bishops and archbishops to run FIFMI branches in their countries. For example, in the United States of America, FIFMI has appointed Reverend Edward Bianchi to run the church as a bishop, while the same church has appointed Elias Soko of South Africa and Matthew Simau of Mozambique to be archbishops of FIFMI in their nations, with several bishops working under them. This is an indication that though FIFMI started in Zimbabwe in Africa, it did not remain a Zimbabwean African Indigenous Church, but has transitioned to be an African International Church. FIFMI has also established centres to train pastors in those nations. It used to run one Africa Multination for Christ College (AMFCC) in Harare, Glen Norah suburbs. Nonetheless, because FIFMI has now expanded into the diaspora, many other AMFCCs have been founded whereby in the United States of America the college is called America Multination for Christ College (AMFCC). However, in other continents where FIFMI is still small their pastors are sent to Africa for training. To date FIFMI has ordained black, white, Indian and other races to minister in their own countries. Thus, the above cited AIC has demonstrated its determination to make African Christianity a global Christianity by means of its membership recruitment policy, which is not aimed solely at converting black Africans but all nationalities. Contrastingly, JMCN in the diaspora presents its missiology with a difference.

Historical Development of JMCN in Zimbabwe

JMCN is a group which split from the original Johani Masowe weChishanu (John of the Wilderness, that congregates on Fridays) (Musoni 2017). This JMCN emerged after the death of Johani Masowe (Shonhiwa Sixpence Masedza) who died in Zambia of a chronic headache (Mukonyora 2007). Because Johani died without choosing his successor, many splinter Johani Masowe Churches emerged upon his death (see examples of these Johani Masowe Chishanu Churches in Musoni [2017]). Thus, Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi (JMCN)-founded by Sanders/Sandros Nhamoyebonde-emerged in the same context. In 1990, Sandros Nhamoyebonde started this new Johani Masowe Church and rebranded it Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Church (JMCN), meaning the true followers of Johani, because Johani/Shonhiwa Masedza was known as the "star leading black people out of darkness" (Engelke 2007). Hence, rebranding his group Johani Chishanu Masowe yeNyenyedzi (of the star) was intended to show the world that his group was the authentic Johani Chishanu Masowe Church. Apart from naming it "of the star," Sandros went on to revive the old Johani Masowe sacred shrine Jurafin Santa/Nyatsime in Chitungwiza (Engelke 2007). It is important to note that Sanders/Sandros Nhamoyebonde was a close disciple of Sixpence Shonhiwa Masedza (Madzibaba Johani) (Engelke 2007, 114). JMCN grew and now has branches in other African countries and even some other continents. The question remains: To what extent has JMCN attempted to assimilate or accommodate other nationalities, particularly the light skinned populace? In other words, has JMCN transitioned from being an African "Indigenous" church/Zimbabwean church to an African "International" church in the diaspora? Accordingly, the study that informed this article, investigated the missiological thrust of JMCN. Scholars, who studied the trends of these AICs in the diaspora, have noted that most African churches have transitioned from being AICs to African International Churches in the diaspora. This is because these African churches have redefined their missiological thrust to accommodate all nationalities and are not only looking for Africans who migrated to Europe and America (Adogame 2013). With this as background, the following sections will investigate JMCN's missiological thrust in the diaspora.

Missiological Thrust of JMCN in the Diaspora

In this study, which investigated the missiological thrust of JMCN in the diaspora, it is cited as an example of an immigrant church which seems to lack a cross-cultural appeal. While other AICs are transitioning to be African International Churches, JMCN has remained a Zimbabwean church in other nations. To validate this claim, the sections below discuss the following missiological themes inculcated by JMCN in the diaspora:

• JMCN membership recruitment policy.

• JMCN places of worship.

• JMCN objects of worship.

• JMCN language of communication in Church in the diaspora.

JMCN Membership Recruitment Policy

To date, JMCN has managed to establish several branches in many countries, including: Botswana, Burundi, Namibia, South Africa, Angola, Tanzania, Mozambique and Malawi, all initiated from Zimbabwe. This Zimbabwean church does not use the Bible for its theology but is guided by tsananguro dzeMweya (the sayings of the Spirit), the Ten Commandments (gumi remitemo), and church regulations (miko ne mirariro) (Interview: Baba Thomas, 2 May 2018). It has branches in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom. Besides being sustained by the recorded sayings of the Spirit, JMCN has also been sustained by the teachings of its sacred leaders: Baba Johani Masowe (1915-1973); Baba Emanuweri Mudyiwa (1936-1989); and Baba Sandros Nhamoyebonde (Nyenyedzi) (1953-1994). We interrogated JMCN membership recruitment policy to compare it with the great commission: "Go ye therefore and make disciples of all nations ..." Matthew 19:28). The JMCN membership recruitment policy states that the religion was established specifically for black Africans/ndudzi yemutema ve vhudzi pfupi kumativi mana enyika. JMCN claims that Johani, Emanuweri and Nyenyedzi were all sent by God to black African communities, unlike John the Baptist and Jesus Christ who were sent by God to the white communities (Musoni 2018, 36). From participant observations in the Masowe Church branches in Mokopane and Tembisa of South Africa, it was found that 95 per cent of the members in those churches were Zimbabweans, with five per cent members being South African citizens. Moreover, all of its members were black Africans; no white people or even Indians were seen in these churches selected for study. During the interviews, Baba Thomas highlighted that JMCN was forbidden by the Spirit to preach repentance to whites/hatibati vachena pamusoro; only to black Africans (Interview: Baba Thomas, 2 May 2018). White people are regarded as enemies of this religion and cannot be accommodated in the gospel economy of JMCN (Interview: Madzimai Kutsirai, 3 May 2018). Members of JMCN are even taught that if one dreams of a white person it is a bad omen; one must seek the intervention of God through many days of praying and fasting (Interview: Madzimai Kutsirai, 3 May 2018). Some members of JMCN intimated that dreaming of a white person is a sign of witchcraft, attempting to bewitch one while asleep. One must seek God's intervention and consult a prophet during services at kirawa. It is according to this recruitment policy that all members of JMCN in the diaspora are black Africans. They claim that the Spirit forbade them to preach to white communities because the whites lost their opportunity as they killed John the Baptist and Jesus Christ who were sent by God to them (Musoni 2018). This black Zimbabwean church believes that the religion was raised for black Africans to address African problems, which are different from European ones (Interview: Baba Andrew, 6 July 2018). For instance, in Africa one finds ancestor veneration, witchcraft, sorcery and alien spirits; a different situation compared to overseas communities (Interview: Baba Andrew, 6 July 2018). JMCN clearly states that white people are enemies of their religion; hence no white person shall be accommodated in this church. This is the reason why, even in the United Kingdom, no whites are members of this particular African church.

Perhaps JMCN's membership recruitment policy was triggered by colonial imbalances between blacks and whites in Zimbabwe. During the colonial regime in Zimbabwe, blacks were repressed and manipulated (Ranger 1999). This repression and manipulation generated a negation theology, as displayed by the Johani Masowe Churches globally (Ranger 1999, 1-31). For Dodo, this Apostolicism as a religious movement emerged as a struggle against colonialism (Dodo 2014, 16). Mukonyora concluded that the Masowe Apostles practise a spirituality that accommodates only those who suffered from white oppression and marginality, translating their experiences into a religious quest for redemption, which they dramatised as part of their theology (Mukonyora 2008a, 62). Thus, this study argues that JMCN does not accommodate whites, probably due to the tension which was created between the black and the white races during the colonial regime in Zimbabwe. For Machingura, the Johani Masowe Churches advocated a total ban on all white inventions (Machingura 2014). In an attempt to achieve that objective, Johani Masowe discouraged his church members from reading the Bible and other religious books (Dillon-Malone 1978). The reason was that these had been brought in by whites (Musoni 2017). We also noted that all the Johani Masowe Church members were discouraged from joining the military and police forces (Dodo 2014, 6). This was done to prevent church members from serving in the white colonial government of that time. Thus, JMCN introduced basket-making as a means of earning a living, shunning formal employment (Dillon-Malone 1978). JMCN postulates a theology of resistance to colonialism. Like Black Theology in South Africa, this church is characterised by a theology of saying "no" to the white man's religion. This Masowe theology is likewise viewed in this study as a theology of saying "no" to everything a white man brought, including the white images of Jesus Christ (Mwambazambi 2010, 5). This is how Jesus Christ is rendered irrelevant for salvation in JMCN because for this church, Jesus was a white man. They argue that God could not have sent a white man to deliver black Africans (Interview: Baba Andrew, 6 July 2018). JMCN introduced a completely new religion, which does not use the Bible; a religion which does not believe in Jesus born from overseas; a religion which is radically, exclusively for black Africans, presenting a theology that does not believe in inter-racial cooperation but rather in racial separation. In addition to their recruitment policy, it is of value for this study to discuss JMCN's sacred places of worship in the diaspora.

JMCN Places of Worship in the Diaspora

To gain an understanding regarding the perspective of places of worship in JMCN in the diaspora, one needs to be acquainted with the origin of the concept; how JMCN chooses its sacred places of worship in Zimbabwe. This study noted that there were at least three factors that caused JMCN to congregate in open spaces during the colonial era and even in the post-colonial era: i) political protest; ii) JMCN theological protest; and iii) African traditional cultural protest.

Political Protest

JMCN's places of worship are the open spaces (Masowe). Thus, praying in the open air for this Zimbabwean church was not a coincidence or the result of a lack of resources to build church buildings, but a political protest. First, congregating in open spaces for JMCN demonstrates the founder's interest in liberation theology, a theology that protested land grabbing by the white government of the colonial era (Mukonyora 2000, 8). According to Mukonyora, the founder of this religious movement chose his surname (Masowe) to denote the difficult circumstances in which he developed his religious ideas and the marginalisation of the black people under white colonialism (Mukonyora 2007, 17). Thus, congregating at Masowe to some extent dramatises Africans' protest against colonial subjugation, displacement and marginalisation of black Africans by the colonial government, particularly in Zimbabwe (Mukonyora 2000, 9). It is a protest in a way because during the colonial period black Africans were deprived of their lands, given to mission churches and white farmers. Most black Zimbabweans were moved to unproductive lands referred to as rural areas (Mukonyora 2000, 9). It is during this colonial era in Zimbabwe that the mission churches in Zimbabwe were, so to speak, distanced from the people's existential problems. Mission churches were allocated large and rich lands at the expense of most Zimbabweans who were displaced into arid lands. Thus, Johani Masowe started a church that congregates in open spaces, which was like a peaceful demonstration against the whites who had robbed them of their lands (Mukonyora 2008b, 85). This is why JMCN is found in fringe, dry, poor areas where there is no agricultural production; in regions where no one can move them because such places are already condemned, unproductive lands. Thus, most JMCN places of worship are near rivers, crossroads, hills, and places where one cannot build or plant crops. We also noted that some Johani Masowe Churches in Zimbabwe were congregating near cemeteries/graveyards, places that indicate no life at all. All this is done to protest the injustice of land allocated by the (then) colonial government. Thus, congregating in open spaces is politically oriented. Ezekiel Guti also narrated how he struggled to find a place of worship when he and his protesting group were expelled from a white missionary church in Zimbabwe (Maxwell 2007). He was later given a space to build his Bible college on the outskirts/periphery of Glen Norah Suburb which was a waste dumping area (Guti 2011). It could be the case that JMCN did not forget that experience and continued to congregate in open spaces, even after the colonial government had been replaced. In addition, this study observed that despite political overtones, for JMCN congregating in open spaces is theologically motivated.

JMCN Theological Protest

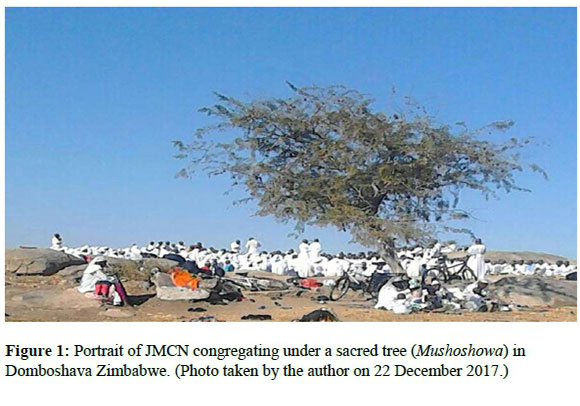

JMCN chooses its places of worship as a theological protest because Johani Masowe taught his members that God cannot be confined in a building, since God is a Spirit (Interview: Baba Nota, 6 July 2018). This kind of theology was a reaction to the missionaries' theory, which holds that Christians should congregate in church buildings. Johani argued that traditionally Africans had no temples of worship but converged under certain trees, mountains/hills and caves (Musoni 2016). It is against this background that African traditional sacred spaces, Masowe/renje, have become central to JMCN spirituality (Mukonyora 2000). Mukonyora (2000; 2007; 2008a; 2008b), who researched and wrote a significant number of articles on Masowe, posited that praying in open spaces does not signify Masowe churches' inability to construct houses of worship, but is a theological concept that needs to be decoded (Mukonyora 2007, 10). This study observed that several attempts were made by the Zimbabwean government to stop churches from congregating in open spaces, but they were all in vain. The first attempt was made in 2014 after several of the Johani Masowe members were struck by lightning during prayers at Masowe. A ruling was made that all churches must have proper building structures to protect their members from harsh weather conditions (Ndlovu 2014). Regardless of this ruling, today JMCN continues to congregate in open spaces. The second ruling to try and prevent Masowe churches from doing so was made in 2015 after the city councils had complained of poor sanitary conditions because members of these churches congregating in open places were using nearby bushes as toilets, causing health hazards in the cities (Ruwende 2015). Again, JMCN did not act on that ruling. Thus, the use of open spaces became a theological position for this church to the extent that even in the diaspora, JMCN does not use buildings for worship but prefers open spaces. For them God is Spirit and cannot be confined in a building. Thus, in an open space, God can freely move. Beside this theological position, JMCN has borrowed the sacredness of forests and open spaces from African Traditional Religion.

African Traditional Cultural Protest

This present study expressed the opinion that congregating in open space was an African traditional practice among most African traditional practitioners. In African traditional religion, places such as cross roads, riverbanks, caves and congregating under certain trees are sacred ones (Musoni 2016). This practice of congregating in an open space denotes appropriation of pre-Christian ways of celebrating and connecting to the divine. For Orobator, long before missionaries came to Africa, Africans had already developed ways of expressing and celebrating their experience of God (Orobator 2008, 142). These include worshipping God under trees and praying in specified caves (Mbiti 1975). Early Western scholars who studied African religions argued that Africans were animists because they had seen them praying under specific trees, hence mistakenly concluding that they were worshipping those trees and rocks (Awolalu 1976, 2). For instance, in Zimbabwe, trees such as Muhacha, Masasa, Mutarara and Mushoshowa are regarded as sacred trees by African traditionalists. The study argued that JMCN's congregating under such sacred trees or near dams and river banks constitutes a revival of pre-Christian approaches to the divine. This is why traditional sacred hills like Chivararira in Zimbabwe are being appropriated as sacred shrines for church services by JMCN churches in Zimbabwe (Musoni 2016). Mabvurira, Makhubele and Shirindi (2015) also emphasise that JMCN's sacred places are those places near water dams/rivers or near crossroads.

Traditionally, riverbanks were very significant because stillborn babies used to be buried there. In addition, Africans believe that water spirits inhabit certain dams and pools (Magaya 2015). Thus, in the event that they could not locate a river nearby, JMCN in Zimbabwe always planted water plants, known as kirawa, at their holy places so as to evoke water spirits and identify with the riverbank theology (Magaya 2015). Therefore, despite harsh cold weather, JMCN the world over congregates outside buildings, particularly near water locks or dams. This study noted that appropriation of river banks denotes a theology of "glocalisation." Glocalisation as a term in this study signifies going back to the origin. Traditional sacred places are being revived with the concept that Mwari is found in an open space, particularly in ancient sacred places such as near rivers. The study concluded that this notion of congregating in open spaces becomes an identity/a brand, a way of differentiating this religion from mission Christianity where services are being conducted in a church building mostly on Sundays, while JMCN conducted worship in open spaces on Fridays. This has become a trademark for this religious movement since it started in 1930 (Dillon-Malone 1978). Hence, congregating in open spaces represents an indication of being faithful followers of the teachings of Johani Masowe, even after he died. Although these Masowe Churches have established branches in the diaspora, the church continued to use Masowe/open spaces as places of worship. In such a manner this minority religion is visible and creates "open air churches," becoming a topical theme in African studies.

Furthermore, we noted in this study that JMCN also congregates at crossroads

(pamharadzanodzenzira). Crossroads in African Traditional Religion are sacred places. During the pre-Christian era and even at present in Zimbabwe, victims of evil spirits are sometimes instructed by a traditional healer to leave valuable objects such as money, live chickens or a goat there. The concept is that if one places a chicken at crossroads, when it moves it will wander in a direction denoting the location of evil spirits. Or victims may be asked by traditional healers to go and take a bath at the crossroads during the darkest hour of the night. This may be in order to confuse the evil spirits because the victims are instructed that after bathing they must leave the place moving backwards for a short distance before they face the direction they are taking. Against this backdrop most JMCN members congregate near crossroads, even in the diaspora.

JMCN Objects of Worship in the Diaspora

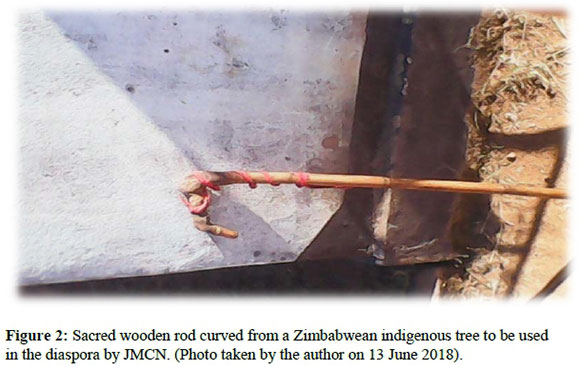

In an attempt to discuss the missiological thrust of JMCN in the diaspora, this study also grappled with the question of their objects of faith. JMCN's use of certain objects on one hand, and its rejection of other objects on the other hand in the diaspora, will assist us to arrive at a conclusion whether JMCN has transformed itself into an African "International" Church or has remained an African Indigenous Church for Africans, while in the diaspora. Thus, we shall examine the use of objects such as clay bowls/mbiya, wooden rods/svimbo, water from certain rivers, certain leaves and small stones/nhombwe for prayers. JMCN spirituality is closely linked to material objects such as water, leaves from certain trees such as Muhacha and wooden rods from certain sacred trees such as Mutarara, Mushenjere and Mutema masanhu. This researcher noted through interviews that because some of these trees are Zimbabwean indigenous ones, JMCN in the diaspora continues to rely on the Zimbabwean church to supply the objects to them outside Zimbabwean borders (Interview: Baba Jairos, 6 July 2018). According to interviews, the Spirit forbids JMCN to use any other wooden material except those crafted from the prescribed trees (Interview: Baba Jairos, 6 July 2018). This study also noted that pre-Christian Africans believed that certain trees' branches or the smells of certain types of wood being burnt, will drive away witches and sorcerers who always cause illness. For example, Mutarara branches are used as cover for recent graves to drive out witches who would want to come during the night to take away a buried corpse (Musoni 2017). Arguably, JMCN used Mutarara to carve wooden rods for church services while some members carve wooden crosses to place at their doorposts or in their cars in Zimbabwe. Thus, the fact that JMCN in the diaspora continues to use objects from Zimbabwean trees only, is a premise enough to argue that JMCN continues to be an AIC, particularly for Zimbabweans who are scattered abroad.

Mbiya is another object central to JMCN's spirituality. The Spirit forbids JMCN from using any other bowl to contain miteuro/prayers, either in the form of water or small stones, except clay pots, mbiya (Madzibaba Tawona 2015). Mabvurira et al. (2015) noted that these objects resemble African traditional objects of worship. Pre-Christian Zimbabwean people used mbiya to hold animal blood being sacrificed to their gods. Traditionally, clay bowls were also used to contain money during lobola ceremonies and rituals. JMCN regards the clay pots as central to its spirituality. We argue that every sacred place of the Masowe churches is marked by the presence of Mbiya or Makate/clay bowls or clay pots. These are produced from Zimbabwean mortar. JMCN does not use clay pots from other nations. Again, this ideology of Zimbabwean clay pots is both politically and religiously motivated. Politically, the use of clay pots from Zimbabwe in the diaspora denotes the church's spirituality being connected to its home country: vana vevhu/sons of the soil. Besides, there is a strong religious connection to varipasi/those who have departed. This study argues that Mbiya was traditionally used to link the living and the dead during traditional ceremonies and rituals. Metal pots were not used during such ceremonies and rituals in African Traditional Religion functions. All participants would be asked to remove objects such as wristwatches and shoes and would not be allowed to use perfume during such gatherings. We concluded that Mbiya denotes African cultures; hence because JMCN continues to use clay bowls from Zimbabwe, this represents preservation of a Zimbabwean culture in the diaspora.

JMCN Language of Communication in Church in the Diaspora

JMCN's missiological approach in the diaspora becomes irrational, especially when we consider the central language it uses for communication. This study observes that JMCN does not utilise English during its church services; rather, Shona is employed. We noted through participant observation that JMCN in South Africa (Tembisa and Mokopane) makes use of Shona as the means of communication in church services. Perhaps this language is used because most of its members are from the Mashonaland provinces of Zimbabwe, where the church started before it spread to other parts of Zimbabwe and later into the diaspora. Thus, this socialisation process of Zimbabwean immigrants, whereby they mix and interact mainly with fellow Zimbabweans in JMCN, is a barrier towards the realisation of multilingual phenomena in the church. In fact, JMCN can be simply labelled a Zimbabwean church in the diaspora. We noted in this study that because the churches use Shona as the lingua franca, most South African locals in the church were speaking Shona. Thus, JMCN in the diaspora is a replica of the "Church of Central Africa, Presbyterian" (CCAP), a Malawian church which was planted in the then Rhodesia/Zimbabwe in 1912 by a Malawian, Rev. T.C.B. Vlok (Juma 2003). This Malawian church was planted to cater for people who had migrated to Zimbabwe from Malawi. Thus, to achieve its missiological thrust:

• First, Chichewa, a vernacular language for the majority of Malawians, was adopted as the one language of communication in church.

• Second, it was agreed that all pastors should receive their training from Malawi.

• Third, the Bibles and hymn books were all in the Malawian languages (Juma 2003).

This comparison indicates that JMCN's missiological thrust focuses mainly on the preservation of the African/Zimbabwean religious culture, rather than propagating a universal gospel that realises the importance of gospel inculturation, making the local people feel at home in church (Shorter 1977). This deduction has been arrived at because JMCN uses only Shona as the lingua franca-even in the diaspora. To reiterate, according to the interviews the English language was forbidden by the Spirit because it is a language of colonialists (Interview: Baba Jairos, 6 July 2018).

Conclusion

This study sought to explore AICs in the diaspora, placing a special focus on their missiological thrusts. We found that some of these AICs have transformed their missiological thrust to accommodate other nationalities in their new territories. We noted that because of this transition the new tag "African International Churches" (AICs) is appropriate. However, we also established that JMCN has remained an AIC for black Africans in the diaspora: it was found that all members are black Africans in the diaspora. JMCN is using Shona as the main language for preaching, even in the diaspora with interpreters translating into vernacular languages, unlike other AICs which use English as the main language for communication in church services. The diasporic JMCN congregates in open spaces, as the Zimbabwean JMCN does, and uses objects of worship like Mbiya and wooden rods, all from Zimbabwe. We noted that JMCN does not use the Bible, does not accommodate whites and does not pray in buildings, among other features, because such were introduced by whites. It is against this background that the JMCN missiological thrust in the diaspora was mainly intended to bring Africans/Zimbabweans together for socialisation. Perhaps this is done to deal with the spirit of homesickness/nostalgia in a foreign land. This suggests that JMCN, as a minority religion in the diaspora, continues to mimic and preserve its African identity as it presents a theology cooked in an African pot. Thus, in a myriad of ways JMCN has drifted from Jesus Christ's imperative: "Go ye therefore and make disciples of all nations." Possibly, in its attempt to deal with cultural imperialism, the church has overlooked Jesus' missiological imperative and concentrated on recruiting black Africans in the diaspora. It is, therefore, recommended that AICs in the diaspora should open their doors to accommodate other nationalities into their gospel economy. The principles of breaking cultural barriers, acceptance and universalisation of the gospel, should be the key to Missio Dei.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Afe Adogame, Gerrie Te Haar, Ezra Chitando, Lovemore Togarasei and David Maxwell who studied AICs in the diaspora. Among these great scholars, I deem it important to mention that Lovemore Togarasei and Ezra Chitando were my university lecturers at the University of Zimbabwe, who have not only provided ready information about the given two Zimbabwean churches, but have family members who are members of either one or both churches. These two Zimbabwean Churches have attracted many people, as they both promise to provide solutions to many African social ills, including health and wealth-being.

References

Adogame, Afe. 2009. "African Christians in a Secularizing Europe." Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Religion Compass 3/4 (2009): 488-501, 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00155.x Journal. [ Links ]

Adogame, Afe. 2013. The African Christian Diaspora: New Currents and Emerging Trends in World Christianity. New York: Bloomsbury. [ Links ]

Awolalu, J. 1976. "What is African Traditional Religion?" Studies in Comparative Religion 10 (2): 247-249. [ Links ]

Dillon-Malone, Clive M. 1978. The Korsten Basketmakers: A Study of the Masowe Apostles An Indigenous African Religious Movement. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [ Links ]

Dodo, Obediah. 2014. "African Initiated Churches, Pivotal in Peace-Building. A Case of the Johane Masowe Chishanu." Journal of Religion and Society-The Kripke Center. moses.creighton.edu/jrs/2014/2014-9.pdf. [ Links ]

Engelke, M. 2007. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church. California: University of Colifornia Press. [ Links ]

Falola, T., and A. Oyebade. 2016. The New African Diaspora in the United States. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315544670. [ Links ]

Guti, E. H. 2011. ZAOGA FIF Guidance Rules and Policy of the Local and Autonomous Assemblies. Harare: EGEA Publications. [ Links ]

Juma, J. 2003. "Immigration and Its Effects on Our Church." REC Focus. http://www.ccaphresynod.com/papersonccap.htm. [ Links ]

Mabvurira, V., Makhubele, J., and Shirindi, L. 2015. "Healing Practices in Johane Masowe Chishanu Church: Toward Afrocentric Social Work with African Initiated Church Communities." Accessed 7 August 2018. https://www.krepublishers.com/.../S-EM-09-3-425-15-347-Mukhubele-J-C-Tx[17].pdf%3E. [ Links ]

Machingura, F. 2014. "Martyring of People over Radical Beliefs: A Critical Look at the Johane Marange Apostolic Church's Perception of Education and Health (Family Planning Methods)." In Multiplying in the Spirit: African Initiated Churches in Zimbabwe, edited by E. Chitando, R. M. Gunda, and J. Kugler, 175-98. Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press. [ Links ]

Madzibaba Tawona. 2015. "Vapositori, Mweya yetsvina and the Bible: A Response to Mr Walter Magaya." Accessed 22 March 2018. https://www.nehandaradio.com/2015/02/12/response-magaya-vapositori/. [ Links ]

Magaya, W. 2015. Marine Spirits/Mweya yemumvura-teaching by Prophet Walter Magaya. Harare: Yadah Press. [ Links ]

Maxwell, D. 2007. African Gifts of the Spirit: Pentecostalism and the Rise of Zimbabwean Transnational Religious Movement. Ohio: Ohio University Press. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J. S. 1975. African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann Press. [ Links ]

Mukonyora, I. 2000. "Marginality and Protest in the Sacred WildernessThe Role of Women in Shaping Masowe Thought Pattern." Southern African Feminist Review (SAFR) 4 (2): 1-21. [ Links ]

Mukonyora, I. 2007. Wandering a Gendered Wilderness: Suffering and Healing in an African Initiated Church. New York: P. Lang. [ Links ]

Mukonyora, I. 2008a. "Women of the African Diaspora Within." In Women and Religion in the African Diaspora: Knowledge, Power, and Performance, edited by R. Grifith and Barbara D. Johns. Maryland: Hopkins University Press. [ Links ]

Mukonyora, I. 2008b. "Masowe Migration: A Quest for Liberation in the African Diaspora." Religion Compass. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=reh&AN=ATLA0001654624&site=ehost-live. [ Links ]

Musoni, P. 2016. "Contestation of 'the Holy Places in the Zimbabwean Religious Landscape': A Study of the Johane Masowe Chishanu YeNyenyedzi Church's Sacred Places." HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72 (1). doi:10.4102/hts.v72i1.3269. [ Links ]

Musoni, P. 2017. "Inculturated African Spiriitual Elements in the JohaneMasowe WeChishanu YeNyenyedzi Church in Zimbabwe." PhD thesis, University of Pretoria. https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/61196/Musoni ... PDF file. [ Links ]

Musoni, P. 2018. "Re-Visiting Christology from AnIndigenous Perspective: A Study of the New Images of Jesu in AfricanChristianity in the Zimbabwean Context." In The Bible and Sociological Contours: Some African Perspectives. Essays in Honour of Professor Halvor Moxnes, edited by Z. Dube, L. Maseno, and E. Mligo, 1: 31-44. New York: Peter Lang. doi:10.1002/ejoc.201200111. [ Links ]

Mwambazambi, K. 2010. "A Missiological Glance at South African Black Theology." Verbum et Ecclesia. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, Lovemore. 2014. "The African Apostolic Church Led by Paul Mwazha as a Response to Secularization." In Multiplying in the Spirit: Africa Initiated Churches in Zimbabwe, edited by E. Chitando, 49-62. Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press. [ Links ]

Orobator, A. E. 2008. Theology Brewed in an African Pot. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Ranger, T. O. 1999. "Taking on the Missionaries' Task: African Spirituality and the Mission Church of Manicaland in the 1930s." Journal ofReligion in Africa 28 (1): 1-31. [ Links ]

Ruwende, Innocent. 2015. "Strict Rules for Open-Air Worship." The Herald. http://www.herald.co.zw/strict-rules-for-open-air-worship. [ Links ]

Shorter, A. 1977. African Christian Theology: Adaptation or Incarnation. London: Geoffrey Chapman. [ Links ]

Interviews

Baba Andrew, W. 70 years, a prophet. 6 July 2018, Tembisa, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Baba Jairos M. 38 years, a prophetess in Masowe yeNyenyedzi. 6 July 2018, Tembisa, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Baba Nota, C. 38 years, a member of Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Church. 6 July 2018, Tembisa, Johannesburg, South Africa. [ Links ]

Baba Thomas, G. 43 years, member of the Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Church. 2 May 2018, Mokopane, Limpopo Province, South Africa. [ Links ]

Madzimai Kutsirai, G. 43 years, a member of the Johani Masowe Chishanu yeNyenyedzi Church. 3 May 2018, Mokopane, Limpopo Province, South Africa. [ Links ]