Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.44 n.3 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/4059

ARTICLE

Messianic characterisation of Mugabe as rhetorical propaganda to legitimise his authority in crisis situations

Menard Musendekwa

Reformed Church University revmusendekwa@yahoo.co.uk. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6644-8727

ABSTRACT

Messianic expectations in Zimbabwe follow the biblical trends where messianic promises were intended to stimulate hope for ancient Israel during socio-economic, political and religious crises. The Zimbabwe situation during the early 2010s was characterised by socio-economic, political and religious crises. This research explores the circumstances in which Robert Mugabe was hailed as national Messiah. While it was genuine prophetic promises for a better future in ancient Israel, the messianic characterisation of Mugabe was used as political rhetoric and propaganda to legitimise the role of Mugabe as the sole liberator and candidate for leadership of the nation of Zimbabwe. This research responds to the question: What triggers messianic characterisation like that popular in Zimbabwe? This research has proved that such messianic characterisation intends to fill the gap where the nation's expectation of a Messiah constitutes the response to socio-economic, political and religious crises.

Keywords: crises; messianic expectation; messianic characterisation; propaganda; hope; social crisis; economic crisis; political crisis; religious crisis; political independence

Introduction

The colonial era of Zimbabwe informs later messianic figuration of the former President of the Republic of Zimbabwe, Robert Gabriel Mugabe. The liberation struggle for the independence of Zimbabwe was amidst hope for a deliverer from the social, economic, political and religious crises, as shall be explored in this paper. The hard-earned independence of 1980 saw Mugabe having assumed the role of the messianic figure. The impact of Christianity among the learned, established views and appreciation of Christian leaders as playing messianic roles. The establishment of the new government was also informed by religious ideologies. Mugabe assumed the messianic role of liberating the nation; despite his later failures. The fact that Mugabe failed the nation of Zimbabwe triggered new hopes for a deliverer. This paper assumes that messianism in pre-colonial and post-colonial eras is a result of the failure of the purported leaders to fulfil the national expectations. This paved the way for the formation of other political parties in a situation where people had been thinking of a one party state. Observations reveal that Mugabe's loyalists declared Mugabe as the Messiah. Messianic characterisation in this regard was stimulated by perpetual resistance. This helped Mugabe to remain in power for over 32 years. It could have been because the post-colonial era raised new expectations when the most needed expectations were not met. President Mugabe was later considered rhetorically as the Messiah to regain support for the ruling party.

Zimbabweans have been living in a political crisis for close to two decades and messianic expectations have been very high. There is continued resuscitation of memories of the pre-liberation struggle when the nation was expecting the coming of a political liberator anointed to release the nation from political oppression. The independence attained in 1980 was the climax where Mugabe was elected as prime minister and later as president of the newly established government. However, once again the nation was immersed in a socio-economic and political crisis when Mugabe accepted the policy of land redistribution. This is when the sympathisers of Mugabe declared him the Messiah, to downplay any opponents and legitimise him as the sole anointed national leader.

The expectations for a liberator may have been brought up by the Shona faith traditions, which associated all social crises with some external spiritual forces. This could be countered by some diviners who could liberate people from spiritual and social bondage. The economic and socio-political crises have triggered the emergence of a new phase of messianic expectations. The fragile economic conditions, social degradation and injustice have triggered a rise in messianic expectations in Zimbabwe. The nation hoped for a change of government. This could have been the reason why the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) gained support during the late 1990s.

The Development of Messianism in the Bible

The Bible is the basis of messianic expectations. Ringgren (1956, 7-10), in the introduction to his book The Messiah in the Old Testament, defends the idea that the Old Testament reference to the Messiah was based on the historical situation of Israel. The New Testament passages reflect the idea that some Old Testament prophecies were fulfilled at a later stage. However, modern biblical scholars have provided different interpretations of those passages. This has created a great gap between the historical-critical understanding and the interpretation of the biblical passages; that is, we have two interpretive contexts-the historical and the theological. Some scholars defend the messianic interpretation of the Old Testament texts in the New Testament. In this way, the historical exegesis would in a way support the traditional Christian interpretation. Ringgren's book, in principle, outlines this understanding. Considering that the Psalms were hymns of ancient Israel, it would be made clear that its content is of pre-exilic origin. Some of these hymns portray enthronement festival, covenant festival or New Year festival, for example, Psalms 24, 47, 96 and 99, which refer to God's enthronement and kingship. Also considering that similar festivals were held in ancient Near East, Israel could not be exempted from such festivals. These festivals were also found in Babylon as New Year festivals and equally dealt with victory over powers of darkness and death and the creation of a new order of life. In this regard, it is shown that the Babylonian New Year festival was a reinterpretation of the former. This paves the way for the New Testament reinterpretation of the theme of messianism considering the Old Testament.

According to De Jonge (1992, 777), the use of the term "Messiah" was not initially for an expected future agent of redemption, but it was developed in later Jewish writings of between 200 and 100 BCE. He claims that it could simply mean any figure that could bring eternal bliss. The terms "messianism" and "messianic" are generally used to denote change in history, not necessarily brought about by a future redeemer. Historians and social anthropologists use these terms to discuss later development in Western history and other cultural contexts-mostly in relation to Western colonial, missionary and modern influences. Messianic expectation becomes the expectation of a saviour called Messiah. De Jonge further warns that the treatment of messianism considering eschatology needs to be taken seriously. Eschatological expectation, however, is described as based on the conviction that God would inaugurate a new era using human or angelic mediators.

Messianic movements are rooted in the social context of a group of people. Messianism entails eminent expectation by a group of people of a hero who will usher them into a golden age. However, it is difficult to distinguish between distinctly religious messianic expectations and secular expectations (Assimeng 1969, 2).

In other words, as Neusner (1984, xi) puts it in the preface of his book Messiah in Context, "the Messiah is an all blank screen unto which the given community would project its concerns." As a result, various points of divergence could be recognised.

Daneel (1984, 40) rejects the negative judgment of messianic movements in Africa, which Western scholars view as non-Christian or post-modern. Based on empirical facts relating to the Shona Independent Churches in Zimbabwe, Daneel (1984) contends that the black Messiah figures are concerned with a legitimate contextualisation of the Christian message related to their own socio-cultural and religious backgrounds.

In an exploration of Derrida's work in the Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Reynolds (2010) observes the late Derrida as a well-known philosopher of the twentieth century. According to Derrida, the Messiah is the wholly other "to come," who is not a fixed or identifiable "other" of known characteristics. His "wholly other" cannot be determined and can never actually arrive. He claims that even when the Messiah is "there," he or she is still regarded as "yet to come." The messianic structure of existence is open to the coming of an entirely ungraspable and unknown other, but the concrete, historical messianic expectations are open to the coming of a specific other of known characteristics. The "messianic" refers predominantly to a structure of our existence that involves waiting in ceaseless openness for a future.

Auffarth (2010, 290) defines messianism from the perspective of the history of religions. The term Messiah referred generally to an anointed one. The term derived a new meaning in the sixth century when Jews expected the Messiah who would deliver them from foreign rule and establish an eschatological age of salvation. The meaning of the word was further expanded in the thirteenth century when it was used as a technical term in Christian theology. During the twentieth century, the term Messiah became applicable to all other religions. In this instance, a redeemer could be an expected political leader, while political religion and cults of personality become the main subjects of messianism. Messianism is associated with a social movement within a specific historical situation which envisions the eschatological culmination of history. Such is the view of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. However, in a situation where colonial powers enforce social, economic, political and religious norms accepted by the elites, the social groups that do not benefit from the privileges respond by seeking an alternative to the existing leadership. In this instance, the messianic figure becomes a charismatic hero leader of a movement, and is designated as the Messiah. The concept "Messiah" developed a new meaning as it portrayed movements which developed in the late colonial and post-colonial periods. The prophecy against the colonial masters would be: "The first shall be the last."

According to Bock (2005, 503-506), the term "Messiah" simply refers to "the anointed one," but in theology it refers to the "promised one" hoped for by the Jews, not necessarily the eschatological figure. It is rooted in the hope for an ideal king, as in Psalms 2:2. Only in Daniel 9:26 is the term Messiah used in a more technical way. While Jewish hopes were there during the time of Jesus, Judaism had four major portraits of a Messiah, as can be traced in other ancient records. These were: 1) a David-like figure; 2) a transcendent figure in the likeness of "the son of man"; 3) a priestly figure; and 4) a prophetic teacher. Most of Bock's discussion focuses on Jesus as the Messiah, which seems to be his main point of reference.

Most definitions of messianism have a thin allusion to a crisis which raises the expectation of salvation. Such human consciousness of a better future is triggered by a crisis, which could be social, economic, political and religious in nature. This definition will be considered in this paper.

Social Crisis (1960-2008)

Among Africans, Christianity suggests a dialogue between the gospel and the African culture. The proclamation of the gospel by people of a different cultural context provided lenses to the understanding of scriptures. The gospel and culture are highly compatible, and the gospel can only be proclaimed from and to a people of alternative cultural backgrounds.

Culture can be defined as the manifestation of the people's way of life and self-understanding (Mugambi 1995, 30). Culture can also be defined as the total process of human activity and the total results of such activity (Moyo 1996, 1). Culture comprises language, habits, customs, social organisation, inherited artefacts, technical process and values. These definitions complement each other. People's way of life is not static but continues to change through life experience.

The social changes which resulted from colonisation led to the marginalisation of the indigenous people. They lost their tribal fertile land to the white minority elites. As a result, there was an increase of resistance movements as people desired to seek modification through spiritual agencies. There were mainly two types of movements. The first is the nativistic type, which sought to return to earlier modes of life that promised stability, happiness and social security. This group aimed at the restoration of land to the owners that could create a sense of satisfaction.

The second is the syncretistic type like the African Watchtower movements and the African Independent Churches (Assimeng 1969, 8-12). This follows the pattern of the post-exilic Jews who developed into various categories. The Pharisees concentrated on the keeping of the Law, so that the experience of the past would not repeat. The Qumran decided to leave the city and concentrate on the study of scriptures, and the Zealots believed they could restore the kingdom through warfare.

Some groups of indigenous Zimbabweans resisted the disparity in land ownership between the Europeans and indigenous people. The Land Tenure Act of 1969 aimed at eliminating racial friction which emanated from the ownership, occupation and use of land. The Land Tenure Act called for the division of land almost "equally" between the European colonial settlers and the indigenous people. 44 952 900 acres was allotted to 250 000 Europeans and 44 944 500 acres was reserved for nearly five million indigenous Africans-clearly not equal at all. It is undeniable that most of the best farms with the best water supply, fertile soil, good terrain and road network were owned by European settlers. Such disparity was spearheaded by the Land Tenure Act of 1969, which had a purpose of forcing Africans to work harder for subsistence in a cash economy which was quite unfamiliar (Creighton 1972, 302-303).

Under this Act, the minister had the right to authorise people of one race to occupy land which was formally designated to another race, or prohibit them from doing so. The Act specified that regular attendance or employment at a school, hospital, clinic, hotel, and so forth, does constitute occupancy. The minister of lands explained in parliament that patronising a store or attending a theatre did not normally constitute occupation. However, in some cases admission to such a place could be controlled to avoid racial friction (Creighton 1972, 302-303).

Economic Crisis (1960-2017)

Messianic hope in ancient Israel was not only triggered by deteriorating social conditions, but also economic challenges. Similarly, from the deteriorating economic conditions in Zimbabwe, arose messianic expectations. Having been hard hit by economic crisis, Zimbabweans yearned for improvements in living conditions.

The Zimbabwean social, economic, political and religious environment during the colonial rule of the 1960s stimulated the liberation struggle, which resulted in attainment of political independence in 1980. It was after a decade when the situation started deteriorating. The ruling government introduced policies that led to the development of an elite community of those loyal to the ruling party, with most of the population languishing in poverty. Hope for a better future was invested in the election of a new multi-party government. In most cases these became beneficiaries of the Land Reform Programme.

It is well understood that-for it to be meaningful-political freedom and independence should be accompanied by economic and social justice. One will always find that the few native aristocrats replace the foreigners. Such practices of economic disparity were condemned by the prophets of the Old Testament in their contemporary society. Yahweh explicitly denounced such economic injustices and He desired equitable distribution of natural and national resources, as is clearly stated throughout the Holy Scriptures (Banana 1979, 419-420).

The Smith regime claimed to be a Christian government on a mission to civilise the "Dark Continent"; yet, they denied indigenous people to be at equal footing with their European counterparts. Indigenous people were treated as sub-human and were denied free citizenship in their own land (Zvarevashe 1982, 13). Zimbabweans remained subordinates of the white colonial government.

During the time of the Federal Government (before 1965) Zimbabwe had a population of about 3.6 million indigenous people; yet the country was ruled by Europeans totalling about 221 000. While Europeans accounted for at most one per cent of the country's population, they dominated national resources. To respond to internal and external criticisms, the colonial government adopted a principle of partnership which Lord Marvin likened to "partnership between a black horse and a white rider." This principle was linked to multiracialism and political gradualism, where indigenous Africans were only permitted a full share of the government once they had reached higher educational and economic standards. The indigenous people regarded this principle of partnership with great resistance, which resulted in the formation of indigenous opposition parties (Hapern 1963, 1141).

Sundkler (1961, 330) observes: "The burning desire of the African for land and security produces the apocalyptic patterns of the Zionist messianic myths, whose warp and woof are provided by native-led policy and Christian or at least Old Testament material." In Zimbabwe, this further stimulated the rise of the liberation spirit.

The formation of the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) became a great threat to the European government. The executive chairman of ZAPU, Ndabaningi Sithole, wrote a petition which out-rightly rejected multiracialism for aggravating inequalities between the indigenous people and European colonialists. Partnership was rejected for it maintained disparity between the concerned parties, giving more advantage to the Europeans. Gradualism was rejected for it aimed at educating indigenous people at a time which made education unthinkable and impossible. Economically the principle of "equal pay for equal work" could not be universally applied. This would also suggest that Africans were to develop at the pleasure of their colonial masters (Hapern 1962, 1141).

In 1971 a government publication was released proclaiming that the maximum this country could afford for African education was two per cent of the gross national product. Equal pay for equally qualified teachers was the rule in Rhodesia until 1971. But in that same year the government announced a new teachers' wage scale, with a difference of up to $1 764 between African and European teachers. At once churchmen condemned this ruling as unfair, unjustifiable, and immoral. If Africans accepted this position of permanent inferiority in society; they would in effect have no desire to rise according to their ability, character and integrity (Creighton 1972, 302).

The ZANU-PF government which was inaugurated in 1980 would soon follow a similar path. The native national elite community inherited the injustices of the colonial masters. Zimbabwe significantly inherited injustices which the natives needed to address in the name of black empowerment. However, such programmes conferred privileges on certain individuals-an environment that compensates natives who were previously excluded from accumulating wealth would now not permit all natives to become entrepreneurs. The challenge is how to determine who should benefit from group empowerment. The Zimbabwean experience reveals the danger of privileging individuals while pursuing a group agenda (Raftopoulos and Savage, 2004). Mutumbuka (1981, xiii) had this to say:

The transition from colonialism in the third world countries is the temptation and pitfall. One of the most obvious is the entry of colonialism in a new guise-in the guise of neocolonialism. This is a more subtle guise and will mean the growth of the black Zimbabwean comprador class which will entrench neo-colonialism. It is this sad truth that African countries are often worse off after independence because of the cruel and ruthless exploitation of neo-colonialism. Corruption and self-enrichment replace the search for freedom and truth, the masses continue to suffer as before.

The crises in Zimbabwe are believed to be multifaceted. However, some scholars believe the referendum of February 2000 was the watershed and a downward shift on the political, economic and social landscape. The first 20 years of independence was encouraging, considering that land redistribution was carried out through the principle of willing-seller-willing-buyer, which had some substantial constraints but was remarkably successful. Resources were unevenly distributed. The adapted economic policies had crippled the economy. The Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP), which called for workers to bargain for salaries, ended in public protests. In fact, 1990 saw growing public protest because of a series of corrupt scandals brushed aside by those in power; yet the response was authoritarian. In contrast, the lobby for political recognition, progress in land redistribution and compensation by the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association (ZNLWA), was positively responded to. The decision to take the country into war in the Congo exacerbated the already fragile economy. The land invasion, which was not planned for, turned the country which used to be the bread basket of Africa, into abject poverty (Hammer, Raftopoulos and Jensen 2003, 1-7).

These social, economic, political and religious reasons led to the rise of protesting voices, which were in favour of the marginalised group of people. Most striking is that those who opposed were mostly church leaders and prominent members of the church. This presupposes that the church leaders were the bearers of the prophetic voice that gave hope for a future liberation.

Political Crisis (1963-2015)

Acquisition of political independence in African countries has resulted in the political leaders being adorned with messianic powers. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah became the Messiah to his followers, among which were those who were alienated from the leadership by colonial masters. His inauguration came after he had a dream of the mother of Ghana bathing in the blood and wounds of her sons and daughters who were fighting to prevent her from colonial domination. He claimed that in the dream he heard a voice saying: "Seek ye first the political kingdom and all things shall be added unto it." After acquisition of political independence, he promised to usher an earthly millennium paradise through establishment of technological projects (Assimeng 1969, 16, 17).

Zimbabwe experienced a period of stability after independence under the leadership of Robert Mugabe. The situation changed and during the past decade Zimbabwe has been experiencing an economic and socio-political crisis. The independent Zimbabwe has been the world record holder of inflation. There is also gross human rights abuse which has caused thousands of Zimbabweans to go into exile.

The liberation struggle, which led to the independence of Zimbabwe, earned hero status for those who were in the forefront. It is important for this paper to briefly reflect on the situation which led to the political struggle in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe, as it is known today, came into being because of the endeavours of Cecil John Rhodes, who championed British supremacy in Africa. It was then named Southern Rhodesia. He subjected the area north of the Limpopo covering the present Zimbabwe and Zambia, which was also named Northern Rhodesia. He aimed at acquiring land by means of land purchase contracts and illegal expropriation under the British South Africa Company (BSAC). Initially, the British government was not enthusiastic to colonise, therefore the BSAC ruled until 1923 when Southern Rhodesia finally became a British protectorate. Following the rising call for independence in Africa, Southern Rhodesia was joined with Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland (present day Malawi) to form the Central Africa Federation in 1953. The Federation collapsed when Northern Rhodesia gained its political independence from the British, as Zambia and Malawi (Van Dijk 2006, 176-177).

The national movement was dominated by Joshua Nkomo's Zimbabwe African Union split. Ndabaningi Sthole led the new group, called Zimbabwe National Union (ZANU). However, it did not take long before Nkomo and Sthole were detained and both parties were banned. ZANU survived under the leadership of Robert Mugabe, who led a more militant form of politics. Eventually both ZANU and ZAPU went into liberation struggle (Freund 1984 279). The liberation struggle was initially hampered by the rivalry between the ethnic groups between the Ndebele under Joshua Nkomo and the Shona under Robert Mugabe, who were fighting for supremacy. They were at the same time facing the well-equipped white minority government (Van Dijk 2006, 177).

Some Zimbabweans think that the "Great God" will come from heaven and take away every challenge. This Messiah complex of hoping for an easy one-man solution to complex challenges applies not only in politics, but also in many other aspects. Various religious sects have emerged in the recent past. Many churches are being led by individuals, whom the followers relate to a virtual god. One would wonder whether they worship God or an anointed reverend, bishop or apostle (Makunike 2009).

Many articles in the mass media have hailed the former President Robert Mugabe as the political Messiah for Zimbabwe. Rev. Obadiah Musindo, president of Destiny for Africa Network, claimed that the president is a black political Moses ("Mugabe God Given-Church Leaders," thezimbabwean.co.uk 2011). He also described him as a God-given leader who cannot be driven out of office, even by elections.

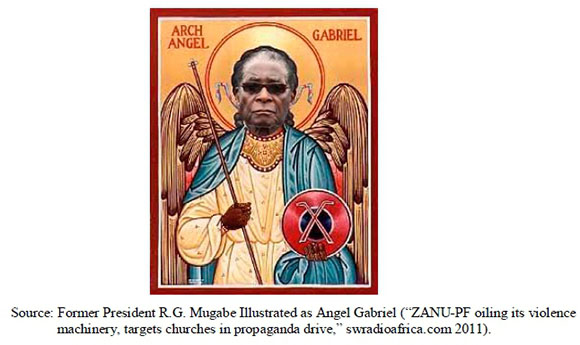

The figure above was posted online after Edward Raradza, Muzarabani Member of Parliament claimed Robert Gabriel Mugabe to be the real Angel Gabriel ("ZANU-PF oiling its violence machinery, targets churches in propaganda drive," swradioafrica.com 2011).

The minister of housing and local government called President Mugabe "God's Other Son" (Mugabe Praise Singer Tony Gara Dies, http://www.newzimbabwe.com 2017). The words of a Christian song have been changed for political ends. The name of Jesus was replaced with vaMugabe ("Mugabe God Given-Church Leaders," thezimbabwean.co.uk 2011).

First they used to call him "the son of God," and then one minister publicly said "Mugabe is our Jesus Christ." Next the minister of education and culture has recently designed and installed a "throne" in parliament, for "King Mugabe." Then the minister of local government would not be outdone. He has decided to build "a shrine" in Mugabe's home village. A shrine is a place of worship. So the president has become a god who deserves a "shrine." Thus, from VaMugabe ndibaba' (Mugabe is our father) to "the son of God" to "Jesus Christ" to a "shrine" a place of worship, God. (Pambazuka.org. 2011)

In Matabeleland North, villagers were living in fear during the period towards the elections of 2002 because of the war veterans. This fear was caused by the claims by war veterans that they were disciples of the Messiah-President Mugabe (Kunene 2002).

Madzibaba Godfrey Nzira, a self-styled prophet who was once detained on seven counts of rape charges in 2003, was recently pardoned by the President of Zimbabwe to coerce members of the apostolic sect and other churches in Muzarabani district to support ZANU (PF) ahead of possible elections in 2011. He claimed that President Robert Mugabe was appointed King of Zimbabwe and none should dare to challenge him. In mid-2010 the president attended Johanne Masowe Apostolic sect, putting on the church garment as a strategy by assimilation ("Zanu PF Activates Its Brutal Campaign," Sokwanele.com 2011).

While in South Africa, President Mugabe lifted the ANC membership card as a ticket to heaven in what many had claimed to be a rhetorical campaign strategy; in Zimbabwe the party card can earn one food. In Nharira village in the Chivhu district, a certain man had to register for food aid but could not get it because he was not in possession of the party card (http://www.innews.org/).

All this deification of political leaders reminds of the former president Canaan Banana, who claimed the need of rewriting the Bible to the Zimbabwean context where we acknowledge our own heroes rather than the Western heroes. He suggested replacing names such as Abraham with Mbuya Nehanda (Reed 2009). The youth leader, Chipanga, is quoted by Maveriq (2018) as saying:

Truly speaking, in heaven there is God and here on earth there is an angel called Robert Gabriel Mugabe. You are representing God here on earth.

But he is an angel. Who doesn't know that God's angels are called Gabriel? I promise you, people, that when we go to heaven don't be surprised to see Robert Gabriel Mugabe standing beside God vetting people into heaven. Gushungo, you are an angel.

Amai Mugabe, you are a wife of an angel so when people enter heaven and when it's Zimbabwe's turn, you will be seated there, with secretary for administration Chombo having names, while you will be vetting those whom you know.

Many Zimbabweans never made any public comment on such characterisation of the political leader. It is currently believed that this was the rise to his downfall. Kudzanai Chipanga was not even satisfied for having said all this. He continued by claiming that Mugabe "is our Messiah," second in command to Jesus. "He is our liberator. We honour God and we have our Jesus ... we honour President Mugabe. He is our liberator. When Jesus came, he liberated this world. When President Mugabe came, he liberated us during his lifetime. So, why not honour him?" (Saunyama 2017).

The circumstances that resulted in his resignation demonstrate that messianic characterisation was going uncriticised because the future of individual citizens required them not to openly criticise him. Instead of luring more support, even members of his political party were privately resisting his authority. Any messianic characterisation was in the first place intended to manipulate people by using religious propaganda.

Religious Crisis

Traditional thought does not permit direct communication with God. The Shona people believe that the departed are little higher than the living and hence act as intermediaries between the living and the supreme. Death of a beloved is not an end but just a change of status and form of being (Moyo 1996, 6). Therefore, the living dead participate in family rituals. Whosoever does not participate, bring misfortune to themselves and their entire families. This puts pressure on every family member to participate. It implies that those who become Christians while others remain traditionalists, are creating serious problems for their communities.

In the same vein, although the missionaries protested the actions of the colonial government, they identified with them in their policy of separate congregations based on race and separate ministry for the converts. Moreover, indigenous communities in mission stations were separated from the elite missionaries. Even if the missionaries employed the natives as domestic servants, they did not entertain them in their dining rooms (Mutumburanzou 1999, 113). As a result, the native church members participated in the liberation struggle.

The rise of African Independent Churches is an expression of resistance to the idea that accepting the gospel means completely rejecting traditional cultures (Moyo 1996, 27). African Independent Churches originated in South Africa and spread among the Shona people. They continued to multiply because African people feel at home by giving a voice to their Christianity in African symbols and images (Moyo 1996, 28).

Another factor that contributed to the establishment of African Independent Churches was the translation of the Bible into African languages. This marked the beginning of translating the gospel into African culture and developed the indigenous African spirituality, as is evident in the African Independent churches (Moyo 1996, 28-31).

The reluctance of missionaries to relinquish top leadership positions to indigenous people, disagreement on faith healing, prophecy and speaking in tongues and their negative attitude towards polygamy, ancestor veneration and use of traditional religion are other factors that helped to create a conducive climate for Africans to seek for a kind of worship that could relate to their own political ambitions (Moyo 1996, 32).

The Rise of Ethiopianism 1910-1977

Ethiopianism is a movement that can be traced back to history and the Bible. Ethiopia resisted against the Italian colonial power in 1896, which impressed the black people in other African countries. This scenario emerged also in the church in Africa. Some black leaders resisted the Western mission churches and formed the Ethiopian churches. An Ethiopian Church was found in South Africa by a Methodist minister, Mangena M. Mokone, in 1892. Their manifesto was based on Psalms 68:31 where it says: "Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands to God." To Mokone it meant self-governance of the church in Africa under African leadership. The Ethiopian churches had no messianic or prophetic elements in them. While messianism started as a religious movement, it ended up being political (Ndiokwere 1981, 28).

The rise of Ethiopianism promoted the spirit of African nationalism in the mission churches. The Wesleyan minister, N. Sithole, who became one of the leaders of African nationalism in Zimbabwe, claimed that nationalism in Africa is based on biblical principles. He also understood that the Bible, which liberated the nation from spiritual bondage, can also liberate the nation from colonial bondage (Martin 1964, 154).

Ethiopianism could have been brought to Zimbabwe from South Africa during the period before 1910 by migrant labourers, and started to spread among the Ndebele and the Shona-speaking people. Among the Shona, Mupambi Chidembo established the First Ethiopian Church. He once worked as a migrant labourer in the Transvaal. He established churches in Bikita, Gutu and Zaka (Daneel 1987, 52-53).

The Rise of African Independent Churches (1930-2015)

African Independent Churches (AICs) could have originated as revolutionary movements, which had quite a variety of secularised forms of biblical hope of God's kingdom as messianic movements. In Zimbabwe, like in many African countries, the movements were political. The leaders as political liberators led their people from slavery to the promised freedom. They could achieve their goals either violently or non-violently (Martin 1964, 151).

This paper briefly discusses four African Independent Churches in Zimbabwe, which have been described by some scholars as messianic. These are: the Zion Christian Church (ZCC), which was founded by Samuel Mutendi; the African Apostolic Church by Johane Marange; the Apostolic Church of John Masowe; and the City of God Church (Guta raJehova), founded by Mai Chaza.

Zion Christian Church: Samuel Mutendi

Originally ZCC was a branch of Lekhanyane's church in the Transvaal. Mutendi had also worked as migrant labourer in South Africa. He expanded the church through faith healing and performing miracles (Daneel 1987, 14). Mutendi was a Christ-like figure to his followers. As a result, many of his followers expected the death of their leader to be followed by signs for them to be reassured of his presence. Some of his followers gave testimony that he had also promised that his death was going to be followed by a sign. It is a popular belief of the Zionists that within three days after his death, Mutendi went into a star which reflected his appearance. A month after his death was declared as a period of awaiting comfort by the Holy Spirit. His followers testify that during that time the Holy Spirit descended upon them with power (Daneel 1988, 270).

African Apostolic Church: Johane Marange

Johane Marange was different from Samuel Mutendi. The African Apostolic Church was a nationwide movement since 1930. It originated in Mutare when Johane Marange broke from the Apostolic Methodist Mission. He identified himself with biblical figures, especially Joseph and Moses (Daneel 1987, 56).

Apostolic Church: John Masowe

John Masowe was originally named Shonhiwa when he was a still young. In 1932 he fell ill and died. While his grave was being prepared he resurrected and told the people that he had been before God. He went into the mountain to pray. When he returned he claimed to be John the Baptist, proclaiming the gospel of the hour. He has won many adherences among the Shona and the Ndebele people. He believed that the dead will wait for John Masowe at the gate of heaven so that he will come and allow them to enter the kingdom of heaven (Sundkler 1961, 324). His followers believed that John Masowe was a secret Messiah who was not known to many, though he was in their midst (Ndiokwere 1981, 42).

City of God Church (Guta raJehova): Mai Chaza.

The messianic church of Mai Chaza was founded by a married woman, Mai (Mrs) Chaza. In 1953 she became ill and later passed on. She is believed to have been resurrected by God on account that her death was premature. When she went to the mountain to pray, she became a faith-healer. The mountain was renamed by the spirit "Sinai" because that is where Mai Chaza, who was claimed to be the new Moses, received power and revelation from God. Her village was renamed the City of God. People travelled here from as far as South Africa, Mozambique, Zambia and Malawi for healing (Ndiokwere 1981, 42).

The place of a leader among the African Independent Churches and Ethiopian Churches was more that of a tribal chieftainship. Mutendi's leadership was even higher than that of a tribal chief. He had established the church within a wide area with many tribal chiefs. Mutendi could now resemble a Rozvi king. Mutendi dressed himself like a king. He also served as a prophetic leader (Daneel 1988, 15).

While the Bible plays a significant role in the African Independent Churches, a liberation theologian and politician, Canaan Banana, argued for the re-writing of the Bible so that it can be relevant to post-colonial societies. He claimed that oppressive texts should be removed.

Banana was also concerned by the Revelation, which is related to only one nation. He advocated for the inclusion of religious experiences of other nations (Reed 2009).

One is compelled to understand why some preachers have inclined themselves to supporting President Mugabe to the extent of claiming his supremacy and to be a carrier of the blood of Jesus Christ. They also use the propaganda by some of the Mugabe loyalists, who claim him to be anointed by Mbuya Nehanda (spirit medium and former liberation heroine) ("ZANU-PF oiling its violence machinery, targets churches in propaganda drive," swradioafrica.com 2011).

In a different note, the president and a delegation from his political party graced the Apostolic Church of Marange Passover festival, putting on religious vestments. Despite the fact that they were not members of that church, they stood to address the congregation (Zimeye.org).

After the visit of the president to the Passover meeting, some leaders of the same church were calling for all members to buy membership cards for ZANU (PF) as a reciprocal response to the two tractors which were donated at this meeting. Madzibaba Shadreck Kwembeya, at a church service at one of the churches in Tshabalala, is quoted as telling his members that at the Passover meeting church leadership had agreed to render their support for ZANU (PF) by insuring that all members are in possession of party cards, failure of which one was to leave the church and form his or her own (Saunyama 2017, zimbabwesituation.com 2010).

President Mugabe also visited ZCC shrine, where he was officially opening an 18 000 seat multipurpose conference centre at Mbungo Estate. Nehemiah Mutendi, who earlier had praised the president and assured support from his huge following, called President Mugabe a God-given leader (zimeye.com).

An Anglican Church Bishop, Dr Kunonga, said that Mugabe is the prophet of God. Dr Kunonga is also well known for saying that President Robert Mugabe is a better Christian than him (Meyer 2008). Kunonga was one of the beneficiaries of the land redistribution programme. He recently broke away from the Anglican Church and is refusing to surrender church property. In his claim of President Mugabe as an instrument of divine justice, Conger (2008) quoted him saying:

As the church we see the President with different eyes. To us he is a prophet of God who was sent to deliver the people of Zimbabwe from bondage ... God raised him to acquire our land and distribute it to Zimbabweans; we call it democracy of the stomach. There is no Government without soil.

Messianic figures were always associated with Christ-like character. We have noted how closely related the spiritual and political leaders are in the Zimbabwean context. The religious groups have become political leaders within their various places. The Bible, which is used to liberate people from spiritual bondage, is the same Bible which raises the spirit of expectation for political deliverance.

Conclusion

Messianic expectations and messianic type of characters in Zimbabwe have emanated from the social, economic, political and religious crises. These expectations benefited the nation of Zimbabwe by stimulating the liberation spirit through which hope for a deliverer became high. This does not embrace the eschatological expectation founded in scriptures that provides hope for the resurrection of the dead, and judgement and the consummation of a divine plan with this world. One would come to realise that the rise of messianic expectations was founded on the need for liberation from the minority rule of the colonial powers, which robbed the dignity of most of the native community. The once united nation was divided into tribal trust lands which comprised of poor soils, while the great productive land was possessed by few commercial farmers. Politically the natives had no right to vote and limited right to education. Liberation spirit was bred in the religious understanding of scripture, which regards the need for a human liberator who assumed a messianic position. While the spirit started in the church, it proceeded to the advocacy for political liberation which led to the attainment of independence.

Messianism in current political circumstances would, rather than being literarily relevant, become rhetorical strategy of legitimisation. This would be related to circumstances beyond those who were once purported to be messianic characters.

The Zimbabwean context can particularly influence how Zimbabwean natives can deal with the theme of messianism. Looking at how some religious and political figures have depicted President Robert Gabriel Mugabe as a messianic figure, one would rather be aware that such is a response to the crises which the nation is encountering.

This paper did not analyse whether the term "messianism" was used in true biblical sense and as to whether those who figured Mugabe as messianic character were truly basing their interpretation on the theological sense. This paper did not provide answers as to who could have been expected by the people as the new messiah to counter the crisis situation which the nation was facing. The media resources might also have been biased and might have limited historical truth, since they might have many other reasons than historical.

References

Assimeng, M. 1969. "Religious and Secular Messianism in Africa." Institute of African Studies Research Review. 6 (1): 1-19. [ Links ]

Auffarth, C. 2010. "Messiah/Messianism." In Religion Past and Present: Encyclopedia of Theology and Religion. Vol. III, edited by H. B. Bertz. Leiden: Brill, 290. [ Links ]

Banana, C. 1979. "The Biblical Basis for Liberation Struggle." International Review of Missions 68 (272): 417-423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-6631.1979.tb01332.x. [ Links ]

Bock, D. 2005. "Messiah/Messianism." In Dictionary of Theology: Interpretation of the Bible, Van Hoozer, K. et al., 503-506. Grand Rapids: Baker. [ Links ]

Conger, G. 2008. "Bishop Says Mugabe Is Moses." Accessed 17 May 2017. http://geoconger.wordpress.com/2008/03/14/bishop-says-mugabe-is-moses-cen-31408-p-8. [ Links ]

Creighton, L. 1972. "Christian Racism in Rhodesia." Christian Century 89 (11): 301-306. [ Links ]

Daneel, M. L. 1984. "Black 'Messianism': Corruption or Contextualisation?" Theologica Evangélica 17 (1): 40-77. [ Links ]

Daneel, M. L. 1987. Quest for Belonging: Introduction to the Study of African Independent Churches. Gweru, Mambo. [ Links ]

Daneel, M. L. 1988. Old and New in Southern Shona Independent Churches. Gweru: Mambo. [ Links ]

De Jonge, M. 1992. "Messiah." In The Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. 4, edited by D.N. Freedman et al. Doubleday: New York, 777-778. [ Links ]

Freund, B. 1984. The Making of Contemporary Africa: The Development of African Society since 1800. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [ Links ]

Hammer, A., B. Raftopoulos, and S. Jensen. 2003. "Zimbabwe Unfinished Business: Rethinking Land the Context of Crisis." In Zimbabwe Unfinished Business: Rethinking Land the Context of Crisis, edited by B. Raftopoulos. Harare: Weavers, 1-43. [ Links ]

Hapern, J. 1962. "White Hopes and Fears in Southern Rhodesia." Christian Century 79 (38): 11401142. [ Links ]

Kunene, T. 2002. "Living by the Veterans' Book." Accessed 26 November 2016. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/2500089.stm. [ Links ]

Makunike, C. 2009. "Overcoming Zimbabwe 'Messiah Complex'." Accessed 16 April 2017. http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/chido8.12573.html. [ Links ]

Martin, M. 1964. Biblical Concept of Messianism in Southern Africa. Morija: Sesotho Book Depot. [ Links ]

Maveriq. 2018. "Mugabe is an angel, and he will be helping God to vet the people who go to heaven: Chipanga." Accessed 13 March 2018. https://news.pindula.co.zw/2017/06/03/mugabe-angel-will-helping-god-vet-people-go-heaven-youth-leader-chipanga/. [ Links ]

Meyer, E. C. 2008. "Robert Mugabe as 'Prophet of God'? Police break up Eucharist in Zimbabwe." Accessed 27 June 2018. https://ericdarylmeyer.wordpress.com/2008/05/16/robert-mugabe-as-prophet-of-god-police-break-up-eucharist-in-zimbabwe/. [ Links ]

Moyo, A. 1996. Zimbabwe: The Risk of Incarnation. Geneva: WCC Publications. [ Links ]

"Mugabe Praise Singer Tony Gara Dies." 2017. Accessed 16 May 2017. http://www.newzimbabwe.com/pages/zvobgo21.14983.html. [ Links ]

"Mugabe God Given-Church Leaders." 2011. Accessed 16 Ay 2017. http://www.thezimbabwean.co.uk/news/37835/mugabe-god-given-church-leaders.html. [ Links ]

Mugambi, J. 1995. From Liberation to Reconciliation: A Christian Theology after the Cold War. Nairobi: Eastern African Publishers. [ Links ]

Mutumbuka, D. 1981. "Zimbabwe's Inheritance." In Zimbabwe's Inheritance, edited by S. Stonman. London: Macmillan, xiii. [ Links ]

Mutumburanzou, A. 1999. "A Historical Perspective on the Development of the Reformed Church in Zimbabwe." Unpublished DTh thesis. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Ndiokwere, N. I. 1981. Prophecy and Revolution: The role of Prophets in the African Independent Churches and in Biblical Traditions. SPK. [ Links ]

Neusner, J. 1984 Messiah in Context: Israel's History and Destiny in Formative Judaism. Philadelphia: Fortress. [ Links ]

Raftopoulos, B., and T. Savage. 2004. Zimbabwe: Injustice and Political Reconciliation. Cape Town: Institute for Justice and Reconciliation. [ Links ]

Reed, S. 2009. "Critique of Canaan Banana's Call to Rewrite the Bible." Accessed 7 April 2016. http://www.unisa.ac.za/Default.asp?Cmd=ViewContent&ContentID=7366. [ Links ]

Reynolds, J. 2010. "Jacques Derrida (1930-2004)."Accessed 13 May 2011. http://www.iep.utm.edu/derrida/. [ Links ]

Ringgren, H. 1956. The Messiah in the Old Testament. London: SCM. [ Links ]

Saunyama, J. 2017. "Mugabe Angel Turns Devil Incarnate." Accessed 13 March 2018. http://www.zimbabwesituation.com/news/mugabe-angel-turns-devil-incarnate/. [ Links ]

Sundkler, B. 1961. Bantu Prophets in South Africa. London: Oxford University. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, L. 2006. A History of Africa. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

"Zanu PF Activates Its Brutal Campaign." 2011. Accessed 26 January 2017. http://www.sokwanele.com/thisiszimbabwe/archives/6313. [ Links ]

"ZANU-PF oiling its violence machinery, targets churches in propaganda drive." 2011. Accessed 15 May 2017. http://www.swradioafrica.com/pages/angelgabriel120511.htm. [ Links ]

Zvarevashe, I. M. 1982. "A Just War and the Birth of Zimbabwe." AFER 24 (1): 13-15. [ Links ]

Electronic sources

http://www.zimeye.org/?p=19931. Accessed 28 July 2011.

http://www.pambazuka.org/en/category/comment/4040 Downloaded 2017-06-10

http://www.innews.org/. Accessed 10 July 2017.