Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.44 n.2 Pretoria 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.25159/24124265/3245

ARTICLE

https://doi.org/10.25159/24124265/3245

Church involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade: its biblical antecedent vis-à-vis the society's attitude to wealth

Emmanuel Kojo Ennin Antwi

Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi-Ghana. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0542-6492. kojoantwi999@yahoo.de

ABSTRACT

Slavery existed in most ancient cultures and continues to exist indirectly in some societies in its various forms. Though slavery was used openly in the past by ancient cultures to create wealth, it is today regarded as an act of injustice against humanity. The trans-Atlantic slave trade between the fifteenth and nineteenth century is no exception. Christians who claimed to have the love of God and humanity at the centre of their religion were involved in such atrocious trade practices to create wealth. The church's involvement in this economic venture seems paradoxical and contrary to its mission of love for all humanity. This paper assesses the church's involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade to unravel the motives of such a paradox. It traces the biblical antecedent to the slave trade vis-à-vis the society's attitude to wealth. It explores how the Judaeo-Christian scriptures and the Greco-Roman world shaped the church's understanding of slavery to see how the church perceived its practice and the motives for its involvement.

Keywords: slavery; slave; slave master; Ancient Near East; Israel; church; trans-Atlantic slave trade

Introduction

Slavery has existed in most ancient cultures and continues1 to be experienced indirectly in most modern societies in its various forms as an economic venture to create wealth. My visit to the Cape Coast and Elmina castles in Ghana on 10 December 2015, with my visitor from Germany, brought me face to face with the realities of the slave trade. The glaring chapels in the centre of the castles seem to suggest that the church was at the centre of the activities in the castles.2 The tour guides' total condemnation of the church's involvement in the slave trade made me ask questions on the subject. How could Christians be worshiping in chapels, under which human beings languished to death in dungeons? How could Christians who claimed to have the love of God and humanity at the centre of their religion commit such atrocities to human beings of different race? The seemingly unsatisfactory answers that came from the tour guides, made me reflect on several aspects of the slave trade-with particular reference to the church's involvement.

At the end of the tour of the Cape Coast castle we arrived at a resolution, which was clearly spelt out on a plaque in the forecourt of the castle:

In everlasting memory

of the anguish of our ancestors

may those who died rest in peace

may those who return find their roots

may humanity never again perpetrate

such injustice against humanity

we, the living vow to uphold this.

This statement admits that the slave trade was injustice to humanity. In that case, all participants in the events are perpetrators of this crime. The church's involvement in such atrocious economic venture seems paradoxical and contrary to its mission of love for humanity. Hence, the church's contribution to the trans-Atlantic slave trade needs a thorough discussion to unravel the motives of such a paradox. Examining the biblical antecedent to slavery helps illuminate the socio-historical context of the Judaeo-Christian faith that shaped the church's understanding of slavery and the motives for its involvement.

The Slave Trade as Injustice against Humanity

The discussion of the extent to which slavery has been unjust and inhuman to the society cannot be exhausted. Slavery denied people of their freedom and rights to live as human beings. Some of the plaques in the castles are evidence of the denial of the human rights of the slaves.3 One of them points out how these slaves were kept in such a dirty and unfavourable environment. The slaves were given little food just to sustain them. We discovered small conduits on the floor of the dungeons, which, according to the tour guides, were meant to carry their faeces and urine into the sea. The statement, "may humanity never again perpetrate such injustice against humanity," on the plaque in the Cape Coast castle, declares the consequence of the slave trade.

Many slaves died in the dungeons. Some slaves were put in condemned cells in the castles to die for acts that were seen by the slave masters to be punishable. Some female slaves were sexually abused in the castles.4 The slaves were treated and transported like wares of trade. They were "shackled in chains like beasts, underfed"5 before and during transportation through the hazards of the seas. Men, women and children were crammed in the decks to such an extent that the slave ships became "floating coffins" and half of the slaves died of disease and mistreatment.6 Some slaves committed suicide in the crossing of the Atlantic.7On arrival at the ports of destination, the slaves were rendered commercial commodities. They had to be displayed in the slave markets to attract buyers. The slaves were conscripted to inhuman and oppressive labour on their arrival in the home of the slave masters.8

The slave trade deprived people of their original religious practices, alienated them from their cultural roots and "deprived them of their sense of place in the world."9 The slaves were uprooted from their cultures and introduced to the alien cultures of their masters. They eventually recognised their non-belongingness to the culture of their slave masters. They suffered social and racial discrimination that haunted them for so long. The slave masters' interest was only in the acquisition of wealth at the expense of the human rights of the slaves.10

It was not only the slave masters who benefited from the slave trade, but also some indigenous leaders of the African communities where the slaves were taken. The slave trade promoted wars on the home of origin, as war became a means by which people got more slaves to sell to the slave merchants. To this, Buah bemoans: "The wars and raids for slaves generated callousness among African slave dealers, their agents and escorts, who became active instruments of barbarism against their fellow Africans."11 The slave trade also affected the population of the home of origin, denying it of young and energetic human resources as well as natural resources.12 The nature of the journey across the Atlantic Ocean was such that only the very strong and energetic ones could survive the journey. The memories of the slave trade and the atrocities committed against the slaves from their capture to their transportation to the Americas are such that the descendants of the slaves cannot but to cry their emotions out when going through the dungeons of the castles.

The Bible and Oppression of Peoples

The Judaeo-Christian scriptures have contributed to the transformation of most societies of the world. The impact of the Judaeo-Christian religious practices on Europe was such that it influenced the cultures of their colonies.13

The influence of the Bible regarding oppression of other peoples was not one-sided. Whilst the oppressors sought reasons for the oppression of others, the oppressed also looked for motives for liberation.14 The Bible, which was the basis of Christian social teachings, was at the same time responsible for the unequal relations that existed between a master and a slave in the Americas.15 The missionaries who arrived on the African soil labelled the African cultural and religious practices as fetish and pagan.16 They used the Bible to justify their subjugation of Africans to such an extent that the white Christians who arrived in South Africa felt they were God's chosen people on a divine mission.17 Such attitude on the part of the Christians made them not to recognise apartheid as morally wrong and sinful.

Slavery and the oppression of people of other nations, particularly the Indians and Africans, were justified with Old Testament (OT) texts.18 Notably among them is Genesis 9:24-27, concerning the curse of Ham, from which the Hamitic hypothesis and attitudes towards slavery were developed.19 This text seeks to explain that slavery was not willed by God in creation, but was rather as a result of a curse of Noah on Canaan, the son of Ham.20 This interpretation implied that the submission of the slave to his master was a divinely approved practice.21

The slave owners did not initially introduce the slaves to the Bible for fear that they might learn about the liberation stories in them and begin to rebel for their freedom.22 When the colonised and exploited Africans were exposed to the Bible, they found revolutionary potential in it that they used to authenticate their fight against oppression.23 They began to find in some characters of the Bible (such as Moses, Joshua and Daniel), a source and sense of liberation.24 The Bible in this context becomes a tool of slavery and liberation at the same time.

Biblical Antecedent to the Slave Trade

The Slave as Economic Asset in the Ancient Near East (ANE)

Israel lived among its neighbours who shared similar cultures. Knowledge of the life and thought of the cultures of the ANE illuminates some cultural practices of Israel.25 Slavery in the ANE could be traced partially through archaeological findings, ANE texts such as the code of Hammurabi, Assyrian Documents and the Nuzi texts.

Slavery was a common practice in the ANE. It was such that both free men and the enslaved never sought for its abolition.26 It began around the fourth millennium BC and was another means of labour, alongside free-hired labour.27 Slavery was practised in diverse situations with economic significance. Ethical and legal provisions were made with regards to the acquisition, the sale and the treatment of slaves.28 In the code of Hammurabi, we find a statement bearing witness to the legal possession of slaves by the individual and the state.29The state as well as private individuals could own male or female slaves. The state owned slaves in the palaces and the temples. The temple received prisoners of war as slaves, as well as through donations and dedications from slave owners.30 Free persons could freely donate their children to the temple for fear of starvation. In some situations, slaves could be allowed to acquire property.31 Helping slaves to escape was punishable by death.

Most of the slaves in the ANE were foreigners who were usually captives of war used as labour in the victors' nations.32 These could even be paraded in the slave markets for sale.33The enslavement of enemies, though it was regarded as social death, was preferred to killing them.34 Among the ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Hittites, and other oriental rulers, only an insignificant number of prisoners of war became slaves and the rest were settled in the land as palace and temple serfs.35

Debt-slavery was another means of acquiring slaves.36 People sold themselves freely into slavery with the reason that they would be catered for by the slave masters. These slaves could, however, be released at a certain period depending on the laws regarding debt-slavery in the country. Among the Babylonians, before the period of Hammurabi, there was a self-sale of people into slavery.37 From the third to first millennium BC, it was permissible in Babylonia, Sumer and Assyria to sell one's children and relatives into slavery and parents who could not feed their children abandoned them to be adopted or enslaved by anyone who desired them.38 Evidence of how people willingly sold themselves into slavery is found in a Mesopotamian legal document, in which it is evident that Sin-balti decided on her own accord to become a slave of Tehip-tilla.39 Consequently, if she decided to enter a different house to become a slave of another person apart from her master, then she would be punished accordingly.

Though slavery was used as labour, it was not the preferred form of labour due to its economic "non-viability."40 Using slaves as labour was not viable due to the fact that the slaves were unwilling to work and some even escaped. Most of them were unskilled and lacked the required skills for the services. As a result, there was always the need to keep constant supervision over the slaves, which was costly. Hired labourers, who were free persons, were used in most cases, and the slaves served as domestic labour that did not require much supervision and skill.

The slaves were considered movable properties that could be inherited and some were given as dowries. Slaves were branded for easier identification in such a way that some had their ears pierced and others had their masters' names written on their hands with red-hot iron.41 Children born to slaves, whose wives were provided by the slave owners in the ANE, remained the property of the slave owner and the liberation of the slave parent did not necessarily imply the liberation of the slave children.42 In some cases, male and female slaves were mated in order to get more slaves from the children for the slave owners. These slaves born to the slave owners had special status as members of the family and in the case whereby the owner of the slave had no son as heir to his estate, the male slave born to him could inherit from him. Children born to slaves and slave-owners or free citizens, were considered free citizens.43

Impact of Ancient Israel's Experience of Slavery

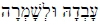

Just as it was among the people of the ANE, slavery was practised among the Israelites.44 The slaves in ancient Israel were an economic asset and legal property.45 For instance, in Genesis 24:35, slaves were counted as part of Abraham's wealth. The system of slavery in Israel was unique and different from those of its neighbours and other ancient empires.46 The slaves in Israel were mostly purchased slaves, debt-slaves,47 and captives of war.48 The good treatment of slaves by Israel was influenced by its personal experience of slavery in Egypt.49 Israel enshrined the rights of the slave in its legal codes in the sacred scriptures. Slavery was not condemned in the Old Testament (OT) as such, except in few texts in the prophetic literature such as Amos 2:6 and Isaiah 50:1, with the former condemning the selling of the righteous and the poor and the latter being used figuratively in reference to Israel.50 Exodus 21:1-11 attests that slaves could be sold in Israel. The word used for "selling" in these texts is " which does not solely imply the acquisition of a possession through payment, but also the handing over of a property51 and the selling of an item with the hope and the right of later redemption.

The experience of Israel as being enslaved in Egypt and its call to observe the ordinances of Yahweh became a point of reference in their treatment of other slaves. Israel is referred to as a slave  in the land of Egypt.52

in the land of Egypt.52  is used in the OT to translate "slave" though not precisely and it is related to

is used in the OT to translate "slave" though not precisely and it is related to  , to work.

, to work.  meant a "bonded worker" and it could be used for a royal servant,53 servant, vassal, loyal, and their related terms. The Qal verb derivatives or cognates are used to imply "to work" which according to the creation narratives, is in line with the purpose of God's creation of man in Genesis 2:15.54 The purpose of putting man in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:15 is given in the consecutive phrases

meant a "bonded worker" and it could be used for a royal servant,53 servant, vassal, loyal, and their related terms. The Qal verb derivatives or cognates are used to imply "to work" which according to the creation narratives, is in line with the purpose of God's creation of man in Genesis 2:15.54 The purpose of putting man in the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:15 is given in the consecutive phrases  (to work and to take care of it).

(to work and to take care of it).  is an infinitive construct of the verb

is an infinitive construct of the verb  with third person feminine singular suffix referring to the Garden of Eden. Working was destined in creation and was part of mankind, however, after the fall of man the land became burdensome to work on as a result of the curse recorded in Genesis 3:17-19.55

with third person feminine singular suffix referring to the Garden of Eden. Working was destined in creation and was part of mankind, however, after the fall of man the land became burdensome to work on as a result of the curse recorded in Genesis 3:17-19.55

One instance whereby enslavement was used against the Hebrews is seen in Exodus 1-2, in which Egypt used slavery to reduce their number. This was contrary to God's mandate to mankind to increase and multiply.56 According to the biblical history of Israel, the Israelites became slaves themselves in Egypt and later became captives in Babylon, which was described in some texts as a yoke of slavery. 57 This experience of slavery became the basis for Israel in its treatment of slaves. In the instructions concerning the jubilee year in Leviticus 25, the Israelites were enjoined not to treat fellow poor Israelites-who sell themselves-as slaves but rather as bonded workers. They were to set them free in the year of jubilee.58 They were not to treat the slaves with harshness.59 These instructions rather concerned fellow Israelites. In Leviticus 25:44-46, the Israelites could, however, make slaves out of other nations and foreigners residing among them.

Deuteronomy 24:7 decreed slave-raiding of fellow Israelites to be punishable by death. 1 Kings 9:20-22 indicates that Solomon made the Amorites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites that the Israelites were not able to destroy completely, during the conquest, into slaves. He did not make slaves out of the Israelites. This points to the fact that most slaves in Ancient Israel were non-Israelites.60 The slaves which were bought were branded and became the permanent property, being listed among other possessions, of the owner and could be passed on as inheritance to later generations.61

Israel had temple slaves  (netinim)62Ezra 8:20 affirms that some were appointed by David to serve the Levites.63 These were the temple slaves that were given to assist the Levites in their cultic duties in the sanctuary.64 Those who could not settle their debt were forced to become slaves of their creditors to serve them in place of the debt.65 In the second temple period, the enslavement of debtors by their creditors was the main source of slavery due to the excessive interest rates.66 These debt-slaves could, however, be redeemed through repurchase. They could as well be set free in the seventh year after they had served their creditors for six years.67 They had the option to decide to remain perpetual slaves for their masters.68 These were usually domestic workers who had legal rights and protection and were considered as part of the household of their creditors and worked together with the family members.

(netinim)62Ezra 8:20 affirms that some were appointed by David to serve the Levites.63 These were the temple slaves that were given to assist the Levites in their cultic duties in the sanctuary.64 Those who could not settle their debt were forced to become slaves of their creditors to serve them in place of the debt.65 In the second temple period, the enslavement of debtors by their creditors was the main source of slavery due to the excessive interest rates.66 These debt-slaves could, however, be redeemed through repurchase. They could as well be set free in the seventh year after they had served their creditors for six years.67 They had the option to decide to remain perpetual slaves for their masters.68 These were usually domestic workers who had legal rights and protection and were considered as part of the household of their creditors and worked together with the family members.

Initially, Israel never had prisoners of war since it was believed that wars were fought under Yahweh's orders and they did not claim the glory for themselves.69 All prisoners of war were to be annihilated.70 Israel later developed the consciousness of showing pity to their captives of war and it was a better choice for them to sell them instead of killing them.71 David's wars provided many slaves, some of which were kept as "perpetual household servants, wives (Deuteronomy 21:10-14) or concubines, and construction workers (2 Samuel 12:31)."72

Though the slaves did not enjoy equal rights with free persons, they were recognised as human beings and were protected by the customs and laws of the land.73 The slaves were put in a good picture in the covenant and the Deuteronomic codes.74 The slaves were not excluded from socio-religious activities. They were included in the celebration of the Sabbath, the Passover and other festivals, provided that they were circumcised.75 They enjoyed some rights with regard to their relationship with their masters.76 It was forbidden to beat a slave to death. This was meant to ensure their human security and to protect them from dehumanising and exploitative attitudes of their masters.77 It was legislated that the slaves were to be set free in the seventh year, as explained above.78 A ceremony of piercing the ear as a mark of perpetual enslavement was done according to the wish of the slave.79

Despite these rights of the slaves, there are instances of possible maltreatment. Some texts attest to maltreatment of slaves. Notably among them are 2 Samuel 8:2; Numbers 31:9-18 and Deuteronomy 20:11-14. In 2 Samuel 12:31, some prisoners of war from Moab were executed for the purpose of instilling fears into the Moabites.80 Numbers 31:9-18 and Deuteronomy 20:11-14 permit the Israelites to kill captives of war. These texts reflect ANE practice whereby some captives of war, men, boys and even women could be put to death leaving the girls to be enslaved.81 In 1 Samuel 25:10 we hear of slaves breaking away from their masters, reflecting the inhuman treatment to them and their desire for freedom.

Slavery in the Greco-Roman World

The New Testament (NT) could best be understood from the background of the first and second century Greco-Roman culture. The ancient Greeks and Romans took advantage of the captives of war to establish a slave economy whereby slaves were used as labour "to maintain Greco-Roman culture and society."82 The Greeks harboured the idea that slavery could not be stopped.83 The possession and the use of slaves by individuals, families, the state and even religious temples became "morally justified and regarded as normal."84 Thus the Roman laws considered slavery to be legitimate and morally right, though it was against nature.85 Slavery continued to be a profitable economic venture in the Ptolemaic period in the whole of Palestine.86 There were slaves of various backgrounds in the region during the Greco-Roman period. It was legal to own slaves like property87 and to have them in the family, though they did not enjoy equal rights and status with family members.88

Some women slaves took care of children, carried out domestic tasks and worked in the sex trade.89 Some of the slaves were treated well by their masters and served in a bond of friendship, whereas others were badly treated and served in a bond of fear.90 Trickery, fawning and fraud became the means by which some slaves obtained their needs from their masters and these vices were to be transferred on the children entrusted into their care. 91As a consequence, slavery bred corruption among even the free citizens. The desire to have more slaves made the slave owners encourage unions between slaves to raise their children as additional slaves.92 Female slaves, though they lacked marketable skills, were treated differently from the male slaves as long as their sexual honour was compromised.93

The slaves were subjected to different forms of inhuman treatment, such as the separation "from their families, tribes, identities, sense of honour and dignity, self-determination over their bodies and time" and denied the same legal rights enjoyed by free persons.94 To inflict physical violence, such as beatings and torture, on a slave was seen to be the right of the slave owner.95 Nonetheless, other emperors such as Augustus, Claudius I, Domitian and Antonius Pius tried to limit the inhuman treatment against the slaves.96 The value of the slave was put on his profitability and not on his human dignity to such an extent that slaves were educated to add value to their profitability. Most of the Greek slaves were learned and rendered services in the areas of medicine, education and business; and they sometimes held sensitive positions like accountants, personal secretaries, administrators and municipal officials.97Though some of these positions had good social status, the value of their services was in the profitability of the functions that they performed. Slaves educated the children of their owners and performed other functions such as writing of documents.98 In some cases, labourers who had no job security willingly sold themselves into slavery to obtain the basic necessities of life.99 Among the Romans, slaves could be freed according to the will of the owner. 100

Douleia and Doulos in the New Testament

The use of δουλεία, (douleia) meaning slavery and  (doulos) meaning slave in the NT gives us indications of slavery in the NT times. Douleia and doulos are used in the Septuagint to translate

(doulos) meaning slave in the NT gives us indications of slavery in the NT times. Douleia and doulos are used in the Septuagint to translate  and its cognates, and on few occasions

and its cognates, and on few occasions  pe'ullāh meaning work, recompense or reward.101Doulos is attested 124 times, occurring mostly in Matthew and the Pauline letters, translating servant and slave in the English versions.102 Servant and slave are not strictly synonymous and the two must be clearly distinguished.103 A slave is owned and he subjects his will to his master, but a servant could not be owned perpetually. The servant only performs service for the master at an agreement. Servant is rendered in the Septuagint sometimes as παις (pais) and διάκονος (diakonos).104These are used a few times in the Septuagint to translate ~ΙΪ73 (servant) and the substantive form of n*1U7 (to minister, serve) in Proverbs 10:4 and five times in Esther 1:10; 2:2; 6:1, 2, 5.

pe'ullāh meaning work, recompense or reward.101Doulos is attested 124 times, occurring mostly in Matthew and the Pauline letters, translating servant and slave in the English versions.102 Servant and slave are not strictly synonymous and the two must be clearly distinguished.103 A slave is owned and he subjects his will to his master, but a servant could not be owned perpetually. The servant only performs service for the master at an agreement. Servant is rendered in the Septuagint sometimes as παις (pais) and διάκονος (diakonos).104These are used a few times in the Septuagint to translate ~ΙΪ73 (servant) and the substantive form of n*1U7 (to minister, serve) in Proverbs 10:4 and five times in Esther 1:10; 2:2; 6:1, 2, 5.

In all the NT texts in which douleia occurs, one identifies its usage as imagery.105 The notion of slavery is used, but not in the same context as that of a person being owned by another. The Pauline usage in the negative sense is employed in antithesis to freedom. Through the Spirit, the Christians are no more slaves to their past but are free.106 Sin and death do not control their will like a slave owner controls his slave. The figurative use of douleia in the NT implies "the state or condition of being subservient, servility."107 Though the term sounds negative on the secular level, when it is used in the figurative sense, it assumes a positive connotation doing away with its compulsive undertone.108

Doulos is used to refer to a slave in both the secular and religious senses. The religious sense is used metaphorically. Some of the texts allude to its secular meaning referring to "slave."109The occurrence of doulos and its cognates in the NT signal the presence of slavery at that time. Doulos is used on the religious level to indicate the relationship between Christians and the Lord. The Pauline epistles exhibit the relationship between Christian slaves and their masters.110 Slaves were integrated into the early Christian community and the status of being either a slave or master did not matter much in the community, but rather their relationship to the Lord was of utmost importance.111 However, in 1 Corinthians 7:21, the slaves were to take the opportunity for their freedom when offered.

In 1 Timothy 1:10,  (kidnappers, slave raiders) are mentioned as being the immoral people. This implies that kidnapping people to sell into slavery was known at that time.112 The text condemns the act of kidnapping based upon the OT notion that kidnapping of fellow Israelites was unacceptable.113 Ephesians 5:21-6:9 and Colossians 3:18-4:1 list slaves with family members.114 In Philemon, Paul recommends for the acceptance of the runaway slave Onesimus, not as slave but a brother. The epistle was meant to restore the relationship between Philemon and his slave Onesimus.115 Though slavery is not condemned in the NT,116 Paul neither recommends the institution.117 Paul had to face an institution, which the early Christians could not change, but to harbour it.118 Some texts bear witness to the fact that slaves were included in the early house churches and were encouraged to be obedient to their masters in the flesh.119

(kidnappers, slave raiders) are mentioned as being the immoral people. This implies that kidnapping people to sell into slavery was known at that time.112 The text condemns the act of kidnapping based upon the OT notion that kidnapping of fellow Israelites was unacceptable.113 Ephesians 5:21-6:9 and Colossians 3:18-4:1 list slaves with family members.114 In Philemon, Paul recommends for the acceptance of the runaway slave Onesimus, not as slave but a brother. The epistle was meant to restore the relationship between Philemon and his slave Onesimus.115 Though slavery is not condemned in the NT,116 Paul neither recommends the institution.117 Paul had to face an institution, which the early Christians could not change, but to harbour it.118 Some texts bear witness to the fact that slaves were included in the early house churches and were encouraged to be obedient to their masters in the flesh.119

Church and State as Partners in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

The trans-Atlantic slave trade in the fifteenth to nineteenth century was begun by the Portuguese, when they took slaves from Africa to work in Brazil.120 Slavery had existed already in Africa.121 The church and the state were seen directly and indirectly to be partners in the trans-Atlantic trade.122 Both enacted laws to support each other. The state relied on the Judaeo-Christian scriptures and ecclesial pronouncements as impetus to the trade. Some used Leviticus 25:46 in which the Israelites could buy and keep slaves and the fact that the apostles never asked for the emancipation of slaves to justify the trade.123 They found the trade as something that was divinely prescribed in the sacred scriptures.

Pope Nicholas V issued the bull Dum Diversas in 1452 allowing the Portuguese to make slaves.124 Some felt that the slave trade was necessary for the existence of the state.125 Some missionaries, monks and nuns indulged in the trade.126 Slave raiders brought along their chaplains to the castles to minister to them. These chaplains witnessed the atrocities that were meted out to the slaves before they were taken to the Americas. The monasteries and the nunneries treated their slaves with justice and humanity but tried in vain to convince other slave owners to do the same.127 The church regarded Sundays as a free day of resting for the slaves to care for their spiritual welfare, whereas the governments insisted that the slave owners must take their slaves to catechism and church.128

The slave trade in Africa was supported through factors from home and abroad. On the part of the slave masters, there was the need to have slaves to work on the tobacco and sugar plantations in the Americas.129 The West African kingdom of Ghana had already traded in slaves before it fell to the Muslims in the eleventh century.130 The market for slaves did not cease with the intervention of the Muslims, but increased in numbers into the twelfth century.131 In other West African countries like Ghana, there were purchased slaves, war captives and hardened criminals who were subjected to various forms of servitude.132 African rulers and raiders found the slave trade business very lucrative and brought captives from the hinterland to the coast to be exchanged for goods like textiles, tobacco and gunpowder.133

In the colonisation of Virginia in North America by the British in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Church of England did little in terms of the conversion of the slaves since there were "ancient principles prohibiting Christians from holding fellow believers in slavery."134 In order to avoid such situations, the slave owners did not want their slaves baptised, which eventually led the church to enact a law in 1667, declaring that baptism did not change the status of a slave.135 This law did not make much impact on the conversion of the slaves. Some denominations remained indecisive on the issue.

Though slavery was the order of the day during the colonial times, with political institutions harbouring and participating in it, slavery bordered the conscience of many.136 The decision to abolish slavery had always been met with both agreement and disagreement. Previously, before the trans-Atlantic trade began, St Anselm (1033-1109) who was an archbishop of Canterbury, had tried to suppress slavery.137 Some thought it was inhuman to have slaves and to be slaves, whilst others felt it was normal and natural to be a slave and to own a slave.138

This debate lingered on among the state and the church. Some began to deliberate on the issue of whether being a slave and owning a slave was morally wrong or not. Pope Paul III issued Sublimis Deus in 1537, declaring that all peoples are human beings and have the right to their freedom and must not be enslaved.139 This bull met the dissatisfaction of Emperor Charles V of the Roman Empire at the time and he called for its cancellation. Priests who preached boldly against the practice were reported to the authorities. In similar vein, Pope Urban VIII's pronouncement against slavery in 1639 was met with opposition by the Portuguese government.140

Back at the place of departure, there were attempts to end the lucrative business but the efforts were met with opposition. Some African traditional rulers who objected to it and wanted to stop it could not attain any success.141 Affonso I of Kongo (1456-1543), who was tutored by the Portuguese missionaries, came to the awareness that slave trade was evil and intended abolishing it, however, the trade became more lucrative to such an extent that more Portuguese as well as some local chiefs took part in the trade. Some of the local chiefs in Senegal protested against the attempt of Almamy of the Futa Toro (late 1700s) to abolish the trade. Some chiefs sold slaves in order not to starve their people.142

In the wake of the independence of the United States of America in 1776, there was agitation for the end of slavery in the new nation that was met with opposition.143 Some denominations began to take measures against slavery, with the Quakers expelling from their midst those who insisted on holding slaves in 1776, and the American Methodists and the Baptists banning slave holding among their members.144 This decision of these denominations was not strictly adhered to in the course of time, since around 1843 some ministers and preachers owned slaves. Some denominations remained indecisive on the issue to end slavery. The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in 1818, for instance, declared that slavery was against the law of God, but opposed its abolition.145 The Catholic Jesuits did not tolerate slavery and did not want slaves in their settlements.146

The Americans were divided on the issue of the abolition of slavery. Those in the south were of the view that slavery was sanctioned by God and it gave the African slaves the advantage of being removed from their pagan and uncivilised environment and "given the advantages of the gospel."147 However, the abolitionist movements in the north advocated that slavery was not in accordance with the will of God.148 The irony is that in the north, slavery was becoming less lucrative and less economically viable, whereas the south depended so much on slave labour. The economic advantages of slavery for those in the south accounted for their stance for the practice of slavery to the extent of seeing it as being willed by God.

Although the church was a partner in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Christian denominations created the awareness of its atrocities to humanity. Taking the decision to end the slave trade in the United States of America became very controversial for the Christian denominations to such an extent that, apart from the Catholics and the Episcopalians, most other denominations suffered schism.149 Concern for the needy and the zeal of the British Christian denominations such as the Anglicans, Quakers and the Methodists to evangelise and to get rid of the evils in the society was to be instrumental in putting an end to the slave trade in Britain and its colonies in the nineteenth century.150 The movement to ban slavery in the British colony and to ensure social justice was initiated by individual Christians from the evangelical revival with prominent men like Grenville Sharp and William Wilberforce.151 Grenville Sharp sought to impress on the courts to set slaves who entered the country to be set free. William Wilberforce, the English Christian evangelical parliamentarian, influenced the British government in 1807 to enact laws that ended the slave trade in 1833.152

Conclusion

Slavery has existed in most cultures as a source of labour. Its profitability blinded the ancient cultures to overlook its injustice against mankind. The ANE cultures permitted it and enacted laws to protect it. Ancient Israel, however, permitted it but toned down its atrocities based upon its own experience of slavery. The NT writers did not explicitly condemn its practice but there are few indications to point to its evils. The societal desire to create wealth eventually got the church involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The importance and profitability of the trade in wealth creation at that time, like in the other ancient cultures, blinded both the church and the state to overlook its injustice and atrocities against mankind. The church did not have enough grounds from the sacred scriptures to abolish it and so tolerated and supported it. The relationship between the state and the church from the early beginning of its establishment accounted for this development. With time, the consciousness against the practice of slavery as unjust against humanity bordered the conscience of many in the church. This resulted in pro- and anti-arguments for the slave trade, both in the state and the church. The atrocious business was later abolished through the instrumentality of some individuals within the church.

References

Adamo, David Tuesday. 2010."The Bible in Twenty-First Century Africa." In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel's Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page (Jr.), 25-32. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Adamo, David Tuesday. 2015. "The Task and Distinctiveness of African Biblical Hermeneutic(s)." Old Testament Essays 28 (1): 31-52. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n1a4. [ Links ]

Bartchy, S. Scott. 2013. "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World." In The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts, edited by Joel B Green and Lee Martin McDonald, 169-178. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Brown, Colin. 1985."Anselm." In A Lion Handbook: The History of Christianity, edited by Tim Dowley, 276-280. Icknield Way: Lion Publishing. [ Links ]

Brown, Francis, and Briggs Charles A. Driver S. R. 2012. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

Buah, F. K. 2011. A History of Ghana. Oxford: MacMillan. [ Links ]

Byrne, Brenden. 2007. Romans. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Carpenter, Eugene. 1997. bd. Vol. III, in New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, edited by Willem A. VanGemeren, 304-309. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Chadwick, Owen. 1995. A History of Christianity. New York: St Martin's Press. [ Links ]

Chupungco, Anscar J. 2006. A Cultural Adaptation of the Liturgy. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers. [ Links ]

Clifford, Richard J. 1998. The Wisdom Literature. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Cohick, Lynn H. 2013. "Women, Children, and Families in the Greco-Roman World." In The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts, edited by Joel B Green and Lee Martin McDonald, 179-187. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Dandamayev, Muhammad A., and S. Scott Bartchy. 1992. Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament. Vol. VI, in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 58-73. New York: Doubledey. [ Links ]

Danker, Frederick William. 2000. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature. Chicago: The University of Chicago. [ Links ]

Davidson, Steed Vernyl, Justin Ukpong, and Gosnell Yorke. 2010. "The Bible and the African Life: A Problematic Relationship." In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel's Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page (Jr.), 39-44. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Debrunner, Hans W. 1967. A History of Christianity in Ghana. Accra: Waterville Publishing House. [ Links ]

Dovlo, Elom. 2017. "'The People of God': Scripture, Race and Identity in African Perspective." Ghana Journal of Religion and Theology 7 (1): 5-29. [ Links ]

Ellis, Elisabeth Gaynor, and Anthony Esler. 2005. Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era. Boston: Pearson Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Fiero, Gloria K. 1995. The Humanistic Tradition: On the Threshold of Modernity: The Renainsance and the Reformation. Madison: Brown and Benchmark Publishers. [ Links ]

Fiore, Benjamin. 2009. The Pastoral Epistles: First Timothy, Second Timothy, Titus. Collegeville: Liturgical. [ Links ]

Gonzalez, Justo L. 1985. The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day. Vol. II. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. [ Links ]

Harill, J. Albert. 2000. "Slavery." In Dictionary of New Testament Background, edited by Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter, 1124-1127. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [ Links ]

Hatch, Edwin, and Henry A. Redpath. 1954. Concordance to the Septuagint. Graz: Akademische Druck-U. Verlagsanstalt. [ Links ]

Hengel, Martin. 1974. Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period, translated by John Bowden. Vol. I. Philadelphia: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Hillel, Daniel. 2006. The Natural History of the Bible: An Environmental Exploration of the Hebrew Scriptures. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

Hobgood, Mary E. 2007. "Slavery." In An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies, edited by Orlando Espin and James B. Nickoloff, 1294. Dublin: The Columba Press. [ Links ]

Izak, Cornelius. 1997. mkr. Vol. II, by New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, edited by Willem A. VanGemeren, 937-939. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Koehler, Ludwig, and Walter Baumgartner. 1994. The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament. Leiden: E. J. Brill. [ Links ]

Kwamena-Poh, Michael Albert. 2011. Vision and Achievement: A Hundred and Fifty Years of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana (1828-1978). Accra: Waterville Publishing House. [ Links ]

Law, Robin. 2009. "The 'Hamitic Hypothesis' in indigenous West African Historical Thought." History of Africa. Cambridge University Press XXXVI: 293-314. https://doi.org/10.1353/hia.2010.0004. [ Links ]

Leslie, James R. 2010. "The African Diaspora as Construct and Lived Experience." In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel's Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page (Jr.), 11-18. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Link, Hans-Georg, and Rudolf Tuente. 1986. Slave. Vol. III, in The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, edited by Colin Brown, 589-598. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House. [ Links ]

Lust, Johan, Erik Eynikel, and Katrin Hauspie. 2003. Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. [ Links ]

Matthews, Victor H. 1988. Manners and Customs in the Bible. Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers. [ Links ]

McKenzie, John L. 1965. Dictionary of the Bible. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Merrill, Tenney C. 1987. New Testament Survey. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press. [ Links ]

Peschke, Karl H. 2000. Christian Ethics: Moral Theology in the Light of Vatican II. Vol. I. New Delhi: John F. Neale. [ Links ]

Pritchard, James B., ed. 1973. The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Vol. I. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Rengstorf, Karl Heinrich. 1978. doulos. Vol. II, in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, edited by Kittel Gerhard, translated by Geoffrey W. Bromiley, 261-280. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Ringgren, Helmer. 1999. 'bd. Vol. X, in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, edited by G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren and Heinz-Josef Fabry, translated by Douglas W. Stott, 376-390. Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Ryken, Leland, James C. James Wilhoit, and Tremper Longman III. 1998. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity. [ Links ]

Sadler (Jr.), and Rodney S. 2006. Africa, African. Vol. I, in The New Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, edited by Katherine Doob Sakenfield, 60-62. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Schmoller, Alfred. 2002. Handkonkordanz zum griechischen Neuen Testament. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. [ Links ]

Shelley, Bruce L. 1995. Church History in Plain Language. 2nd Edition. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers. [ Links ]

Streett, Daniel R. 2009. "Philemon." In Theological Interpretation of the New Testament: A Book-by-Book Survey, edited by Kevin J. Vanhoozer, 182-185. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Tomko, Josef Cardinal. 2006. On Missionary Roads. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. [ Links ]

Witherington III, Ben. 2013. "Education in the Greco-Roman World." In The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts, edited by Joel B Green and Lee Martin McDonald, 188-194. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Wood, Skevington A. 1985. "The Methodists." In A Lion Handbook: The History of Christianity, edited by Tim Dowley, 450-455. Icknield Way: Lion Publishing. [ Links ]

Wright, Christopher J. H. 2004. Old Testament Ethics for the People of God. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [ Links ]

1 E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era (Boston: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005), 96.

2 Josef Cardinal Tomko in sharing his experience of his visit to the Elmina castle, on seeing the chapel, put a few questions to himself: "How could those 'Christians' have been so insensitive? How far will people stoop for money, and how easily can they calm their conscience...! [sic.]" J. C. Tomko, 2006, On Missionary Roads (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006), 80-81.

3 We found at one of the corners of the Cape Coast castle a statement that reads: "Once slaves arrived at the various forts and castles they were led to the dungeons to await the arrival of the slave ships. There were separate dungeons for men and women and both places were small, dark and dirty."

4 The tour guides explained to us that the slave masters abused some of the female slaves. They used them to satisfy their sexual instincts. They raped some of them in the castles. Women who strongly resisted rape were maltreated and punished. One of them informed us that those who got pregnant had to be released.

5 G. K. Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition: On the Threshold of Modernity: The Renainsance and the Reformation (Madison: Brown and Benchmark Publishers, 1995), 138.

6 E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 97.

7 B. L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language. 2nd Edition (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1995) 405.

8 G. K. Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition: On the Threshold of Modernity: The Renainsance and the Reformation, 138.

9 Cf. B. L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 405.

10 In the words of Hobgood, slavery in the United States was an economic institution "built on racism and sexism, for the systematic attempted brutalization and the super-exploitation of kidnapped Africans" who were denied many human rights. M. E. Hobgood, "Slavery," in An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies, edited by Orlando Espin and James B. Nickoloff, 1294 (Dublin: The Columba Press, 2007), 1294.

11 F. K. Buah, A History of Ghana (Oxford: MacMillan, 2011), 72-73.

12 Cf. F. K. Buah, A History of Ghana, 71-73.

13 Cf. A. J. Chupungco, A Cultural Adaptation of the Liturgy (Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2006), 75.

14 D. T. Adamo, "The Task and Distinctiveness of African Biblical Hermeneutic(s)." Old Testament Essays 28/1 (2015): 31-52, 34.

15 J. R. Leslie, "The African Diaspora as Construct and Lived Experience." In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel's Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page (Jr.), 11-18 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010), 11.

16 F. K. Buah, A History of Ghana, 139.

17 S. V. Davidson, J. Ukpong and G. Yorke, "The Bible and the African Life: A Problematic Relationship." In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel's Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page (Jr.), 39-44 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010), 40.

18 S. V. Davidson, J. Ukpong and G. Yorke, "The Bible and the African Life: A Problematic Relationship," 43. Cf. E. Dovlo, "'The People of God' Scripture, Race and Identity in African Perspective." In Ghana Journal of Religion and Theology 7 /1, (2017): 5-29, 6-7.

19 R. Law, "The 'Hamitic Hypothesis' in indigenous West African Historical Thought." History of Africa (Cambridge University Press) XXXVI (2009): 293-314, 294-296.

20 Cf. C. J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2004) 337.

21 Cf. S. V. Davidson, J. Ukpong, and G. Yorke, "The Bible and the African Life: A Problematic Relationship," 42. Sadler comments that the Europeans transferred the curse on Canaan in the text on Ham "to theologically justify the enslavement of all African people as Ham's descendants." R. S. Sadler (Jr.), Africa, African. Vol. I, in The New Interpreter's Dictionary of the Bible, edited by Katherine Doob Sakenfield, 60-62 (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2006), 61.

22 B. L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 405.

23 Cf. D. T. Adamo, "The Bible in Twenty-First Century Africa." In The Africana Bible: Reading Israel's Scriptures from Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by Hugh R. Page (Jr.), 11-18 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2010) 27.

24 S. V. Davidson, J. Ukpong, and G. Yorke, "The Bible and the African Life: A Problematic Relationship," 42.

25 R. J. Clifford, The Wisdom Literature (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1998): 24-25.

26 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 58-73 (New York: Doubledey, 1992), 61.

27 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 58.

28 Cf. J. L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible (Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1965), 823.

29 J. B. Pritchard, ed, The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Vol. I. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973), 141. "If a seignor has helped either a male slave of the state or a female slave of the state or a male slave of a private citizen or a female slave of a private citizen to escape through the city-gate, he shall be put to death."

30 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 59; J. L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible, 824.

31 H. Ringgren, 'bd. Vol. X, in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, edited by G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren and Heinz-Josef Fabry, translated by Douglas W. Stott, 376-390 (Grand Rapids: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1999), 389.

32 H. Ringgren, 'bd, 389; D. Hillel, The Natural History of the Bible: An Environmental Exploration of the Hebrew Scriptures (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006) 105; M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 59. Cf. 1 Samuel 4:9.

33 Cf. J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, 333.

34 S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World." In The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts, by Joel B Green and Lee Martin McDonald, 169-178 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013), 169.

35 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 59.

36 H. Ringgren, 'bd, 389; M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 59.

37 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 59.

38 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 59.

39 J. B. Pritchard, ed, The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, 170. "Sin-balti, a Hebrew woman, on her own initiative has entered the house of Tehip-tilla as a slave. Now if Sin-balti defaults and goes into the house of another, Tehip-tilla shall pluck out the eyes of Sin-balti and sell her."

40 Cf. M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 60.

41 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 60.

42 J. L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible, 823.

43 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 61.

44 V. H. Matthews. Manners and Customs in the Bible (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 1988), 122; J. L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible, 824.

45 L. J. C. Ryken, J. Wilhoit and T. Longman III, Dictionary of Biblical Imagery (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity, 1998), 797.

46 Cf. M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 58.

47 Leviticus 25:44-45.

48 Joshua 9:18-27.

49 D. Hillel, The Natural History of the Bible: An Environmental Exploration of the Hebrew Scriptures (New York: Columbia University Press), 45.

50 Cf. H. G. Link and R. Tuente. Slave. Vol. III, in The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, edited by Colin Brown, 589-598 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1986), 594.

51 Cf. C. Izak, mkr. Vol. II, in New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, edited by Willem A. VanGemeren, 937-939 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1997), 937.

52 Deuteronomy 5:15; 15:15; 16:12; 24:18, 24.

53 C. J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, 333. The term could be used metaphorically to imply one who renders special service and not necessarily as "slave." Instances are found in texts whereby a superior speaks to his inferior. Cf. J. L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible, 825.

54 Genesis 2:5, 15.

55 Cf. E. Carpenter, 'bd. Vol. III, in New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis, edited by Willem A. VanGemeren, 304-309 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1997), 304-305.

56 Genesis 1:28

57 Cf. Jeremiah 25:11; 27:7. Dandamayev explains that Israel, being slaves in Egypt, did not imply slavery in the exact meaning of the word but rather they "were only obliged to perform forced labour for the pharaoh." M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 62.

58 Leviticus 25:38-41

59 Leviticus 25:43.

60 Cf. L. J. C. Ryken, J. Wilhoit and T. Longman III, Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 797.

61 Cf. M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 64-65. Cf. Genesis 12:16; 24:35 and 30:43

62 Cf. 1 Chronicles 9:2; Ezra 2:58, 70 and Nehemiah 7:72.

63 As to whether or not netinim constituted temple slaves remains a scholarly debate.

64 Ezra 8:20, cf. L. Koehler and W. Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1994), 641; F. Brown, C. Briggs and S. R. Driver, The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon (Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, 2012), 682.

65 V. H. Matthews. Manners and Customs in the Bible, 23; cf. 2 Kings 4.

66 L. J. C. Ryken, J. Wilhoit and T. Longman III, Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 797; S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 173.

67 Cf. Deuteronomy 15:12; Leviticus 25:39-11.

68 Cf. J. L. McKenzie, Dictionary of the Bible,. 823

69 H. G. Link and R. Tuente. Slave, 590.

70 Cf. Joshua 8:24-26.

71 H. G. Link and R. Tuente. Slave, 590.

72 V. H. Matthews, Manners and Customs in the Bible. Peabody, 122.

73 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 65.

74 Exodus 21-23 (23:9; 22:21).

75 Cf. Exodus 12:44 and Deuteronomy 16:11-14.

76 Cf. Exodus 21:1-11; 20-21.

77 Cf. C. J. H. Wright, Old Testament Ethics for the People of God, 334-337.

78 Cf. Exodus 21:2

79 Cf. Exodus 21:5-6 and Deuteronomy 15:16-17.

80 V. H. Matthews, Manners and Customs in the Bible, 122.

81 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 63.

82 S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 169. The Roman Empire depended so much on its conquered prisoners of war as slave labour to create more wealth to fund the empire. J. A. Harill, "Slavery." In Dictionary of New Testament Background, edited by Craig A. Evans and Stanley E. Porter (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 1126; S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 171.

83 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity (New York: St Martin's Press, 1995), 242.

84 S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 169-170.

85 J. A. Harill, "Slavery," 1124.

86 M. Hengel, Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in their Encounter in Palestine during the Early Hellenistic Period, translated by John Bowden. Vol. I. (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1974), 40-43.

87 M. A. Dandamayev and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 66.

88 Cf. L. H. Cohick, "Women, Children, and Families in the Greco-Roman World." In The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts, edited by Joel B Green and Lee Martin McDonald, 179-187 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013), 179.

89 L. H. Cohick, "Women, Children, and Families in the Greco-Roman World," 181.

90 T. C. Merrill, New Testament Survey. Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1987, 50.

91 T. C. Merrill, New Testament Survey, 50.

92 L. H. Cohick, "Women, Children, and Families in the Greco-Roman World," 182.

93 L. H. Cohick, "Women, Children, and Families in the Greco-Roman World," 183.

94 S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 169. Cf. J. A. Harill, "Slavery," 1125. They suffered "social death" being alienated from their families and being denied of their freedom and dignity as a person.

95 Cf. S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 171

96 Cf. S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 175-176.

97 T. C. Merrill, New Testament Survey, 15-16; S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 173.

98 Cf. B. Witherington III, "Education in the Greco-Roman World," In The World of the New Testament: Cultural, Social, and Historical Contexts, edited by Joel B Green and Lee Martin McDonald, 2013, 188194 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic), 188-194.

99 S. S. Bartchy, "Slaves and Slavery in the Roman World," 173.

100 J. A. Harill, "Slavery," 1126-1127.

101 E. Hatch and H. A. Redpath, Concordance to the Septuagint. Graz: Akademische Druck-U. Verlagsanstalt, 1954, 345.

102 Cf. A. Schmoller, Handkonkordanz zum griechischen Neuen Testament (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2002), 131-132; F. W. Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: The University of Chicago, 2000), 259-260; J. Lust, E. Eynikel and K. Hauspie. Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2003), 160-161; H. G. Link and R. Tuente. Slave, 595.

103 F. W. Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature, 260.

104 Cf. A. Schmoller, Handkonkordanz zum griechischen Neuen Testament, 116; F. W. Danker,. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature, 230; J. Lust, E. Eynikel and K. Hauspie. Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint, 139.

105 Douleia occurs five times in the NT in Romans 8:15, 21; Galatians 4:24; 5:1 and Hebrews 2:15.

106 Cf. B. Byrne, Romans. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2007, 249.

107 F. W. Danker, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature, 259.

108 H. G. Link, and R. Tuente, Slave, Vol. III, in The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, 589.

109 Matthew 6:24; Luke 16:13; John 4:51, I Corinthians 7:20-24; 12:131 Timothy 6:1-2; Titus 2:9 and Philemon 16. Cf. Galatians 3:28; 4:1; Ephesians 6:5ff; Colossians 3:22ff; 4:1.

110 Cf. K. H. Rengstorf, doulos. Vol. II, in Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, edited by Kittel Gerhard, translated by Geoffrey W. Bromiley, 261-280 (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1978), 270.

111 Cf. K. H. Rengstorf, doulos, 272.

112 M. A. Dandamayev, and S. S. Bartchy, Slavery in Ancient Near East, Old and NewTestament, 67.

113 Cf. B. Fiore, The Pastoral Epistles: First Timothy, Second Timothy, Titus (Collegeville: Liturgical, 2009), 44.

114 Cf. L. J. C. Ryken, J. Wilhoit and T. Longman III, Dictionary of Biblical Imagery, 797

115 From the fourth century AD, Chrysostom, Jerome, and Theodore of Mopsuestia and from the reformation period, Luther and Grotius recognised that the epistle was not intended to abrogate slavery but to restore the relationship between a slave and his master. D. Streett, "Philemon." In Theological Interpretation of the New Testament: A Book-by-Book Survey, edited by Kevin J. Vanhoozer, 182-185 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009), 183.

116 T. C. Merrill, New Testament Survey, 50-51.

117 Cf. K. H. Peschke. Christian Ethics: Moral Theology in the Light of Vatican II. Vol. I. (New Delhi: John F. Neale, 2000), 80.

118 Cf. K. H. Peschke. Christian Ethics: Moral Theology in the Light of Vatican II, 80

119 Ephesians 5:21-6:9; Colossians 3:18-4:1.

120 G. K. Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition: On the Threshold of Modernity: The Renainsance and the Reformation, 138-139.

121 In the Arab empire, captives from Africa were used as slave labour. E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 96-97; H. W. Debrunner, Hans W., A History of Christianity in Ghana (Accra: Waterville Publishing House, 1967), 39-40. M. A. Kwamena-Poh, Vision and Achievement: A Hundred and Fifty Years of the Presbyterian Church of Ghana (1828-1978) (Accra: Waterville Publishing House, 2011), 60. The missionaries identified traces of the practice of slavery in the African culture.

122 The trans-Atlantic slave trade took place within the pre-Reformation and the post-Reformation period. The Reformation did not end the slavery. The church in this paper must be seen in the context of the church before and after the Reformation.

123 B. L. Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, 405-406.

124 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 189.

125 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 189.

126 Cf. E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 98.

127 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 189.

128 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 189.

129 E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 97.

130 G. K. Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition: On the Threshold of Modernity: The Renainsance and the Reformation, 129.

131 G. K. Fiero, The Humanistic Tradition: On the Threshold of Modernity: The Renainsance and the Reformation, 129-130.

132 F. K. Buah, A History of Ghana, 49-50.

133 E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 97.

134 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day. Vol. II. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1985), 219.

135 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 219-220.

136 Cf. J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 250.

137 C. Brown, "Anselm." In A Lion Handbook: The History of Christianity, edited by Tim Dowley, 276-280 (Icknield Way: Lion Publishing, 1985), 276.

138 Strangely enough, it was discovered that African chiefs sold slaves in order not to starve their people and stopping the slave trade might also not do good to the black Africans from whom the slaves were taken. Cf. O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 274.

139 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 190.

140 H. W. Debrunner, A History of Christianity in Ghana, 50.

141 E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 98.

142 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 274.

143 Cf. J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 250.

144 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 250.

145 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 250-251.

146 O. Chadwick, A History of Christianity, 242.

147 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 251.

148 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 251.

149 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 251.

150 J. L. González, The Story of Christianity: The Reformation to the Present Day, 272.

151 A. S. Wood, "The Methodists." In A Lion Handbook: The History of Christianity, edited by Tim Dowley, 450-455 (Icknield Way: Lion Publishing, 1985), 455.

152 C. Owen, A History of Christianity, 242. In the United States it was the civil war, which eventually helped end the slavery. The economic situation at the time as well as the problem with the slavery had already begun to divide the north. This situation together with Abraham Lincoln's opposition to slavery was some of the factors leading to the war Cf. E. G. Ellis and A. Esler, Prentice Hall World History: Connections to Today the Modern Era, 309.