Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versión On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versión impresa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.43 no.1 Pretoria 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/2017/1978

ARTICLES

Reconstructing the anti-apartheid lived narrative of a black theologian, Allan Aubrey Boesak

Gordon Ernest Dames

Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology. University of South Africa. damesge@unisa.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to reconstruct the setting of a black theologian's life and the course of our collective human history during our contemporary history, between 1985 and 2015. Hopewell (1987) offers an illuminating hermeneutical lens to reconfigure the lived narrative of one of South Africa's prolific anti-apartheid activists. Narrative discourse is important in the establishment of the setting to reconstruct the conditions within which the events of our struggle against apartheid materialised. We seek to analyse and understand the meaning/s of the struggle for freedom implicit in the 1980s' setting. This article aims to respond to our contemporary social need for a new vision and activism by reconstructing the setting of our struggle against apartheid.

Keywords: Alan Aubrey Boesak; black theology; quadripolar; semantic square literature analysis; life narrative

INTRODUCTION

We warned that an incomplete revolution is the same as a postponed revolution, and that if we could not find the courage to squarely and honestly face the sins of our past we would not gain the integrity to face the challenges of our future. We were largely ignored, marginalized, and in some ways attacked and targeted because our expression of a liberation theology within the context of post-1994 South Africa did not fall in line with the demands of the new, natural, official narrative of a post-apartheid, de-racialised rainbow nation (Boesak 2014, 1059).

We are a country haunted by both the remnants of apartheid and the neo-colonial powers so rife in contemporary South Africa. What can we learn from a black theologian, Allan Aubrey Boesak, to redress the past and address the current and future challenges to ensure a free, equal and non-sexist and non-racist society?

The life story of Allan Boesak is very complex and difficult to recount with a single dominant element (Kotze and Greyling 1991).1 We will need to consider, at least, the more prominent heterogeneous elements in his life story. The latter's multiple facets require integration to compose his "dynamic identity" by synthesising the heterogeneous elements into emplotment. We seek, in particular, to synthesise the multiple anti-apartheid events or incidents to configure the completed story in Boesak's life as an anti-apartheid activist.

The heterogeneous elements in Boesak's story can be recounted as either unintended circumstances; fellow comrades who suffered due to apartheid; planned encounters; anti-apartheid actions ranging from conflict to collaboration and objectives to advance the struggle for freedom and liberation. All of these factors constitute his story, a complete plot, which is simultaneously concordant (similar) and discordant (conflicting) (discordant concordance or concordant discordance). Frey's semantic literature analysis (in Hopewell 1987) will, secondly, be applied to analyse Boesak's anti-apartheid life story. Thirdly, his own story will be described in terms of Hopewell's quadripolar analysis method. Fourthly, his rationale, in service of humanity, as a black theologian will shed more light on why and how he sustained his life and ultimate goal as a black theologian. This is followed by the conclusion.

South Africans have generally expressed paradoxical expectations about Boesak during the struggle for liberation. Our expectations about the outcome of his story influenced its impact both on the setting and on our own lives in varied forms (Ricoeur 1991, 21). Our expectations have been readjusted more often than we know, as his story continued, especially after it reaches its conclusion (Ricoeur 1991, 22): "Retelling a story best reveals this synthetic activity at work in composition to the extent that we are less captivated by the unexpected aspects of the story and more attentive to the way in which it leads to its conclusion."

Any configuration of the life story of Boesak remains uncompleted in newspapers, scientific academic journals, blogs, and books. It can only reach completion in the act of reading or the reader whose life could be reconfigured by Boesak's narrative. The significance of his narrative is centred in the intersection of the world of the text and the world of the reader. The act of reading his life story thus becomes the critical moment of the entire analysis-herein lies the narrative's capacity to transfigure the experience of the reader (Ricoeur 1991, 26). Boesak's narrative could be conceived as a retrospective reconfiguration in and by the reader.

We should be mindful of the fact that the combination of acting and suffering or contingencies constitutes the key fabric of life (Ricoeur 1991, 27). This mixture of life or mimesis praxeos, the imitation of an action, prompts a search for convergence in a narrative in, and through the living experience of acting and suffering (Ricoeur 1991, 27). It is through our collective life and experience that we may arrive at a better understanding of Boesak's life narrative (Ricoeur 1991, 22).

The aim of this article is, therefore, to reconstruct the Sitz im Leben (setting) of Boesak's life and, implicitly, the course of our collective human history during the anti-apartheid struggle for liberation and freedom. Ricoeur (1991) and Hopewell (1987) offer an illuminating hermeneutical lens to reconfigure our lived narrative. Narrative discourse is important to reconstruct the conditions within which the events of the struggle against apartheid have materialised (Hopewell 1987, 55). We seek to analyse and understand the meaning and importance of his life as a black theologian. The aim is simultaneously to address the moral vacuum, which plagues the unresponsive youth in South Africa today by reconstructing the setting of the struggle against apartheid (Hopewell 1987, 55).

Power and powerlessness characterise crisis settings, such as the long and inexorable struggle against apartheid, and challenge its significance:

The strange opacity of certain empirical events, the dumb senselessness of intense or inexorable pain, and the enigmatic unaccountability of gross inequity all raise the uncomfortable suspicion that perhaps the world, and hence man's life in the world, has no genuine order at all-no empirical regularity, no emotional form, no moral coherence. And the religious response to this suspicion is in each case the same: the formulation, by means of symbols, of an image of such a genuine order of the world which will account for, even celebrate, the perceived ambiguities, puzzles and paradoxes of human experience. (Hopewell 1987, 56)

Could it be that the life narrative of Boesak can once more serve as a symbol of reconfiguration that can inspire us in this world characterised by disorder, liminality, and an emotional and moral vacuum? We may recount again the once dreaded image of a fearless anti-apartheid activist in order to illuminate "the perceived ambiguities, puzzles and paradoxes of human experience" (Hopewell 1987, 56).

The 1985 anti-apartheid setting represents a cosmic construction that reminds us of the oppressive and brutal force of apartheid (Hopewell 1987, 56). We concur with Hopewell (1987, 56) that a personal narrative dramatises the manner in which a community perceives itself and the world. Douglas (in Hopewell 1987, 56) demonstrates how perceptions about someone or the self-emulation of a society's interpretation of its communal nature and of the world are formed.

This is exactly how, as theology students, we have interpreted the context of apartheid and our struggle against it with a code of solidarity and relentless determination that shaped our individual and social struggle activities. The anti-apartheid struggle fostered a measure of congruence between our experiences on a personal, social and international level, with the exception of divergent agency, which forms part of the regime's tactics (Hopewell 1987, 57). The millions of poor South Africans and oppressed people across the world who continue to suffer under neo-colonialism and new forms of oppression are a frightening reminder that "the struggle should continue-A luta continua! The shape of life at each level, its significance, and stages of development are frequently analogous" (Hopewell 1987, 57). We should, therefore, redress our current worldview of a free and democratic South Africa. This is critical if we are to re-inform "the way we see and deal with our individual members, corporate bodies and the wider world" (Hopewell 1987, 57).

In the heat of the struggle against apartheid we longed for, proclaimed and sought liberation, equity and freedom for our country. We seek to recount that narrative for the current world, gripped in unspeakable forms of suffering, with the hope that the narration of Boesak's personal experiences can inspire new hope and action for liberation (Hopewell 1987, 57). Our collective narratives may as well present different facets of how we lived life during apartheid and how we could reconfigure life in circumstances of suffering, which could re-echo images and symbols of hope, freedom and equity (Hopewell 1987, 58). Our understanding of the interpretation of life and death issues in, and through Boesak's life narrative can help us recognise, appreciate and construct the implicit different worldviews.

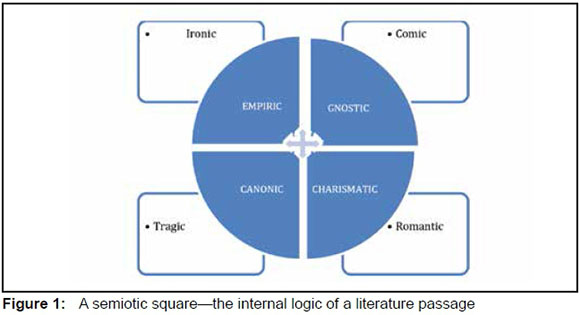

Frye's four narrative genres (in Hopewell 1987, 58) are illuminating in this regard to distinguish between these different worldviews. He positions Western literature in an imaginary circle with four key points like a compass, namely comedy, romance, tragedy, and irony (Hopewell 1987, 58). The relationship between poetry and history provides us with a helpful hermeneutical instrument to capture and integrate the heterogeneous incidents in Boesak's life story. Ricoeur (1991, 22-23), in this instance, emphasises the importance of poetry in relation to history in developing a narrative understanding of someone's life story. Tragedy, epic and comedy develop narrative understanding as practical wisdom of moral judgement opposed to science/theoretical reason.

Boesak's life narrative, in our view, cannot be captured by pure scientific theoretical reason. It warrants practical wisdom of moral judgement to understand the complexities and paradoxes in his life story as a political activist. The way in which Frye structures Western literature is instrumental in our attempt to reconstruct Boesak's story. Frye locates the different genre elements of Western literature in a circle, clockwise, ranging from comedy, romance, tragedy, and irony. If a story does not fit within a particular genre, it is then placed between two adjoining types of genre (Hopewell 1987, 58). We will now attempt to locate the life story of Boesak according to Frye's literature structure.

THE COMEDY PERSPECTIVE IN BOESAK'S LIFE NARRATIVE

Comedy helps inform a worldview that integrates the apparent antithetical or discordant elements in a life story. It distinguishes itself from the disintegrative course of tragedy and facilitates a shift from problem to solution scenarios. The end result of comedies is the unification, accord or embrace between different factions (Hopewell 1987, 58). The latter could instil hope and trust in a fragmented and broken world (Boesak 2014, 1055-1074). Hopewell's (1987, 58) theory that comedy is created in misinformation and complicated by inaccuracy reminds us of the many ill-published news reports about Boesak's apparent questionable moral conduct. The outcome of a comedy is determined "by the disclosure of a deeper knowledge about the harmonious way things really are" (Hopewell 1987, 58). The latter is of such significance, especially for those of us who can recall the many instances in which Boesak took us to an imaginary place to envision a better, new, free, and equal political dispensation in South Africa. He believed that "apartheid can never be modified", only "eradicated" (South African History Online 2015).

The antithetical or discordant events (contingencies) in Boesak's life relate particularly to the apparent fraud charges and two extramarital affairs with white women. Relationships across the racial boundaries between whites and blacks were unlawful, and one of the most brutal apartheid policies no human being should ever experience. For instance, the two extramarital affairs during 1985 and 1990 as well as the fraud charges led to his resignation of the presidency of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches (WARC) and his decision not to accept a United Nations post (Times Wire Services 1990), respectively. His first affair with Di Scott was suspiciously made public and engineered by the apartheid security agencies to discredit Boesak as the president of the WARC. He was not deterred and continued to strive for a free, equal, and non-racist South Africa.

Boesak yielded a capacity to shift challenges into solutions as stepping stones to the ultimate dismantling of apartheid. His determination was ultimately recognised and rewarded with numerous prestigious awards, such as the Robert Kennedy Human Rights Award and the Martin Luther King Jnr Peace Award-"in recognition of his leadership on humanitarian, reconciliation, social justice and theological leadership" (Christian Theological Seminary 2013). Foreigners bestowed these honourable awards on him despite "all the attempts to falter his character and role in the freedom struggle" (Butler University 2013). Boesak eventually "emerged as one of the world's preeminent authorities on liberation theology" (Christian Theological Seminary 2013). On the local front, he was, among other prestige positions, elected to serve as the Assessor and Moderator of the former Dutch Reformed Mission Church (DRMC) between 1982 and 1990 (Christian Theological Seminary 2013).

History is true in its authenticity if it acknowledges that Boesak has inspired unifications and accords between different groups or factions in search of freedom from an evil oppressive system. The year 1985 witnessed increased levels of activism and resistance against the apartheid regime, which responded in extreme inhuman, violent, and unconventional tactics to crush any form of resistance (Jones 1987; Simmons 2001; Times Wire Services 1985). Police, for instance, barged into Christian and non-Christian church services to arrest political activists (Simmons 2001; United Press 1986). The 1985 state of emergency introduced one of the darkest periods in our lives. The launch of the Kairos Document in September 1985 and progressive institutions such as COSATU in December 1985 forged a new kind of solidarity among the oppressed people of South Africa. One of the most rewarding and inspiring occurrences or concordance of heterogeneous anti-apartheid activities in 1986 was the inauguration of Desmond Tutu, a close friend and comrade of Boesak, as the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town. This single episode brought a sense of freedom and righteousness to millions of South Africans who were not even part of the Anglican Church (Arrison 2012).

Following the aforementioned, we can concur that Boesak overcame all these harsh discordances. He excelled as an inspirational and fearless black theologian; was honoured with various prestigious awards; instilled hope and trust among comrades; inspired solidarity, and led with a fearless vision for imminent freedom, justice and equality for all.

THE ROMANTIC PERSPECTIVE IN BOESAK'S LIFE NARRATIVE

Romantic stories inform our vision for "possible liberation through spiritual adventure" (Hopewell 1987, 59). The process of liberation is not in terms of new scientific knowledge, but the collective insight and experience of fellow human beings who encountered similar oppressive conditions in life (Hopewell 1987, 59). Romance in Boesak's life narrative steered him and his fellow oppressed brothers and sisters in South Africa towards "a quest for the most desirable object", namely liberation from the evil apartheid system (Hopewell 1987, 59). Good and evil were frequently sharply contrasted in the stories of a romantic South Africa of freedom, equality, and justice for all.

In his unique romantic tales, Boesak so often displayed the difference between the vision and mission of protagonists (anti-apartheid activists) and antagonists (the apartheid regime). He inspired and embodied a charismatic understanding of our country. We were ultimately empowered through God's spirit to disengage from our domestic life routine, and to engage in solidarity and accountability with "the promise of God's liberating act" (Hopewell 1987, 59). Such was Boesak's tenacity that we can concur with Hopewell (1987, 59):

The hero of romance moves in a world in which the ordinary laws of nature are suspended prodigies of courage and endurance unnatural to us are natural to him. He would become a hero in romance, venturing into the unknown, battling the evil, finding the good, in the end gaining the prize.

1985 and 1986 were watershed years in the struggle for liberation in South Africa. Boesak held an unmovable disposition to fight for, and attain freedom for the oppressed masses of South Africa. He vowed multiple times to resist the apartheid regime until its demise, despite numerous personal and family hardships (Associated Press 1985). One such an occasion was during a worship service in the DRM congregation of Bellville on Sunday 23 September 1985, while he faced charges of subversion. He declared "I will resist them to the end" and continued by confronting the apartheid government. "They have no God left except the God of their guns. Let them pray to that God" (Cowell 1985).

Boesak, the then president of the WARC, was ultimately found guilty on three charges of subversion and released on bail (Cowell 1985). He was arrested twice since March 1985 following continued actions of anti-apartheid protests against the regime. His arrest on 27 August 1985 occurred after he had addressed and ensured students at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) that the march to Pollsmoor Prison for the release of Nelson Mandela would continue. I recall the devastating and powerless mood among his supporters, church members, and UWC students.

The same helpless, sombre mood filled the Bellville congregation the following Sunday, 1 September 1985. The author of this article conducted the worship service, which was packed with fellow church members, students, activists as well as members of the local and international media. I can still feel the intense focus and burning sensation of, among others, BBC's television cameras on my face as I read Exodus 2:23-25:

During that long period, the kind of Egypt died. The Israelites groaned in their slavery and cried out, and their cry for help because of their slavery went up to God. God heard their groaning and he remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac and with Jacob. God looked on the Israelites and was concerned about them (knew them-recounted their story).

It felt as if time stopped, as if we went into numbness-yet, that worship service lifted us out of that disempowering state of entropy. Imagine the exhilaration when Boesak was released on 19 September 1985 in Malmesbury.

His relentless challenge against the regime was highlighted when he made the now famous call: "We want ALL of our rights, we want them HERE and we want them NOW!" in August 1983 with the launch of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in Rocklands, Michells Plain (Cowell 1985). We were all called upon to commit ourselves to bring the evil system of apartheid to a fall by fighting against it in every conceivable manner. Who can forget our collective and bold proclamation at mass gatherings, political, cultural and religious meetings, and public protest events? "We shall overcome; the struggle must continue; A luta continua!" (Cowell 1985). The detention of Boesak under the security laws of an evil system did not deter him from living up to his promise (Cowell 1985).

Cowell (1985) held that Boesak ranked with the most radical among South Africa's militant clerics. His call to boycott white-owned businesses introduced the most severe acts of resistance by millions of oppressed people. A day of prayer for the overthrow of the evil apartheid system ultimately united millions in an act of solidarity and non-violence protests. Desmond Tutu, winner of the 1984 Nobel Peace Prize, was perceived as a mediator, but Boesak was publicly confrontational (Cowell 1985).

The regime used his extramarital affair with Di Scott, a 30-year-old white woman, to expose him: "[H]e told supporters that official efforts to besmirch him would not blunt his political mission. 'If people think I will crawl into a hole and not be seen again ... they have another thing coming'" (Cowell 1985). "[H]e maintained what he called [it] 'a relationship' with Miss Scott, but said: 'No human being should be forced to speak so publicly about his or her innermost feelings, and I shall therefore not try in any way to explain the meaning of this relationship'" (Cowell 1985). The consequence of Boesak's second extramarital affair with Elna Botha, a journalist, ultimately led to his resignation from the ministry in the then DRMC in 1990. His former wife, Dorothy Boesak, witnessed his ordination as a clergyman at the age of 23 and from 1970 to 1976 "lived in the Netherlands while he completed a doctoral thesis on ethics" (Cowell 1985).

The majority of black South Africans perceived the manner in which this episode was publicised as an official police smear campaign. The whole matter reinforced Boesak's anti-apartheid credentials (Cowell 1985). Boesak remained relentless and called South Africa's white leaders the "spiritual children of Hitler" and the then South African police a "spiritual murder machine" (Cowell 1985; The Department of Information and Publicity 1992; Encyclopedia of World Biography 2010). He was part of a collective who never gave up on the vision of a liberated South Africa (Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights 1985).

February 1990 saw the beginning of the end of the evil system of apartheid. The apartheid state realised that it could no longer maintain the apartheid system and opted to release the "political" prisoners, and unban the liberation organisations such as the African National Congress (ANC), AZAPO, and the Communist Party. Many freedom fighters and exiles in the diaspora across the world could return to South Africa. The first democratic election on 27 April 1994 launched our new-found liberation from an unjust, inhuman, and evil oppressive regime (Arrison 2012).

Following the aforementioned, we can concur that Boesak was a fearless nonviolent freedom fighter, while a "romantic at heart". He inspired and empowered millions of oppressed South Africans to dream of, and to strive for political liberation and freedom for all.

The comic and romantic life narratives of Boesak that envisioned liberation (concordance) were juxtaposed by unfortunate stories of tragedy and irony (discordance). The latter portrayed discordant settings "in which he had to accept his plight, and the world as it is" (Hopewell 1987, 60). Tragedy and irony, for instance, differ in their perception of how life in the world unfolds. Tragic stories highlight the fundamental purposes in our lifeworld, whereas ironies cannot not do the same (Hopewell 1987, 60).

THE TRAGIC PERSPECTIVE IN BOESAK'S LIFE NARRATIVE

The tragic stories in Boesak's life narrative depict the degeneration of his life and the manner in which he suffered in order to attain liberation from oppression. This part of his life narrative projects him as a tragic hero: "The self in tragedy, as in romance, is heroic, but unlike the romantic hero, the tragic hero submits to a harshly [un]authentic world" (Hopewell 1987, 60). The latter should be interpreted in terms of his relentless role as anti-apartheid protagonist who was prepared to suffer for the cause of the struggle to attain freedom for the oppressed. He had simultaneously yielded great tragic actions, which impacted and caused tragic incidences in his everyday life as he advanced the cause of the Other/other (Hopewell 1987, 60). For this reason, we should concur with Hopewell (1987, 60) that "[t]he fall of the great tragic heroes is more monumental than our own."

I can recall how Boesak's presence, voice, tone, and intellect, in spite of the costs of retribution at the hands of the regime, yielded an ensuring sense of fearlessness, justice, righteousness, hope, and intent, which brought a mysterious "power", inspiration, and fear to his audience. Frye (in Hopewell 1987, 61) emphasises this by positing: "Tragic heroes are wrapped in the mystery of their communion with that something beyond which we can only see through them, and which is the source of their strengths and their fate alike."

During those dark days, Boesak was one of the only actors who embodied and articulated the dream and vision of freedom materialised in own time. He was the lens that allowed millions to see beyond the forces of evil. We should, therefore, concur with Wolterstorff (2014) that "Boesak has been the victim of unjust punishment-his [fundamental purpose] is not criminal justice, but primarily the struggle for the righting of primary injustice and the role of hope in that unavoidably conflictual struggle." For example, as mentioned earlier, he was arrested the day before he was due to lead a protest march to Pollsmoor for the release of Nelson Mandela. He eventually appeared twice in a Malmesbury court near Cape Town to apply for suitable bail conditions that would enable him to proceed with his international responsibilities (Mathews 1985). My fellow theology student friends and I attended both court sessions in Malmesbury and can recall how the regime's prosecutor pictured Boesak as a threat to their "safety" and how ludicrous the prosecution looked.

The most tragic incident for most of us was the 1999 incarceration of Boesak, which signified his "final" fate, suffering, and humiliation at the hands of an evil regime (or was it a neo-regime?). Their resolve to incarcerate him was like the thongs of the whip of the dragon that caught Gandalf's knees in the movie The Lord of the Rings, which dragged him deep into the underworld of evil (Tolkien 1995, 322). When Boesak entered Pollsmoor prison to serve his prison term on fraud charges, Ruden (2000) reported that "even some of the prison guards demonstrated on his behalf." What a tragic irony.

Following the aforementioned, we concur that Boesak, as a tragic hero, suffered humiliation and unjust punishment for millions of oppressed black people in Southern Africa, in particular, as well as across the globe, in general.

THE IRONIC LIFE NARRATIVE

The ironic discordance in Boesak's life narrative renders him a hero neither in irony, nor among some of the members of his own church. His humanity and self-disciplined incongruity were revealed in either a sensitive or insensitive manner by the stories shared by his fellow colleagues, church members, comrades, enemies, and the regime-controlled media. Hopewell (1987, 61) posits that "reputedly worthy persons come to naught and what seem to be good plans go sour." This must be the most unfortunate fate any good person on this earth is worth suffering. The dilemma of any irony lies in its inability to undergird "a heroic and purposive interpretation of the world" (Hopewell 1987, 61). The reaction of people towards ironic discordance in Boesak's life, or should we say, the very response of people towards irony in his life, rendered his heroic worthiness and life goal/s as zilch (Hopewell 1987, 61). However, the abovementioned story genres give sacred significance to the discordant concordance incidents in Boesak's life narrative, while, in irony, a natural explanation by "unworthy commentators" is only offered (concordant discordance).

Some of us at times have, in some way or another, hoped that the ironies in Boesak's life be met with miracles, which never materialised. His life as an anti-apartheid activist seemed unjust at times without any justification by transcendent forces (Hopewell 1987, 61).

This was certainly the experience of the collective during the dark days of apartheid, which offered little comfort, certainty, justice, and peace-the sense of God's silence and apathy forced us to find solace and security in embraces of camaraderie in solidarity.

The oppressed in this country survived because of its inborn capability to grasp and embrace the paradoxes (concordant discordance and discordant concordance) of our collective experience. We could laugh at the inexplicable discordant incident, cry in the embrace of our camaraderie, and love and hope in the face of insufferable injustices (Hopewell 1987, 61). Frye's convergence of two genres (in Hopewell 1987, 61) in his great literary circle illuminates how Boesak and millions of South Africans could live within a paradoxical reality of double meanings such as comic ironies, tragic romances, or romantic tragedies. Any form of life within an evil system such as apartheid would have been structurally impossible if we had to deal with polar opposites such as comedy and tragedy and romance and irony (Hopewell 1987, 61-62). The latter in the life narrative of Boesak would have been implausible and is inconceivable.

Boesak's life narrative was fractured by the ironic news stories, which broke during 1995 about corruption and fraud charges against him (Reuters 1996). An investigation was initiated into these charges during 1997 for the apparent defrauding of donations from the Dan Church Aid, a Danish aid agency. This happened two weeks before he was due to be appointed as ambassador of South Africa to the United Nations in Geneva (Department of Information and Publicity 1992). He subsequently "faced trial in Cape Town on misappropriating more than half a million dollars in donations from international church and aid groups" (Kotze and Greyling 1991). Boesak was consequently convicted for fraud in 1999. He refused to testify in his own defence and maintained his innocence, which he ultimately motivated in his book Running with Horses (Grobler 2009): "[H]e feared he would sell out his own comrades whom he had helped with money given by foreign donors to his Foundation for Peace and Justice" (Fischer 2009; Mail & Guardian 2009). He was convicted on three charges of theft and one of fraud, and sentenced to six years in prison. After serving a year in Pollsmoor prison, he was granted presidential pardon and released on 22 May 2001.

Following the aforementioned, we concur with Hopewell (1987, 61) that the irony in Boesak's life lies in the fact that he has symbolised the struggle for freedom by embracing the arbitrary dynamic of life in reaching out to humanity in common plight. He faced injustice with a sense of divine and human silence and apathy.

But what about his own views-his own voice?

BOESAK'S OWN STORY

The life narrative of Boesak would be incomplete without the acknowledgement of his own perception about his person and role as an anti-apartheid activist. Hopewell proposes a similar literary framework to Frye in order to distinguish and analyse the varied perceptions of people. The majority of theorists offer a bipolar categorisation of people, communities, or organisations to distinguish between liberal and conservative worldviews. Hopewell (1987, 83) offers a complex typology, namely his quadripolar worldview analysis. He contends that there is no sustained unified, sharply defined worldview (Hopewell 1987, 83).

Hopewell (1987, 84) focuses his research on Peter Berger's notion about "marginal situations of human existence which reveal the innate precariousness of all social worlds." He reflects thus on crisis in order to gain insight into people's interpretation and worldviews (Hopewell 1987, 85):

Different people give different meanings to similar events and crises, and each group treated evidence of evil or the numinous or nonsense in a distinctive manner. World views, therefore, reflect and give a focus to group experience, providing a map within which words and actions make sense. The setting ... by which its gossip, sermons, strategies, and fights-the household idiom-gain their reasonableness. What is expressed in daily intercourse about the nature of the world is idiomatic, responsive to a particular pattern of language, expressing a particular setting for narrative.

In anticipating the complexity of the worldviews people may hold about someone's life narrative, Hopewell (1987, 68-69) employs four basic categories (canonic, gnostic, charismatic, and empiric) to differentiate between these perceptions. These categories represent the dynamic and meaningful perceptions of people as they converge or diverge from one another. The interpretation of a person may adequately be described by one of the categories after engaging in a more complex process in applying two or three of the categories in different ways (Hopewell 1987, 69).

Stories, in general, are structured according to structural literature analysis. For example, the application of Frye's semiotic square, the internal logic of a literature passage, or Hopewell's quadripolar analysis helps describe the relation of a story to a series of four (canonic, gnostic, charismatic, empiric) opposing propositions (Hopewell 1987, 72).

The reader of this article should make his/her own hermeneutical choice of how to read Boesak's quadripolar or semantic square life narrative. We hold that the final story itself configures and reconfigures its own plot within the bigger scheme of history.

When a person is challenged to address actual situations, s/he may respond by using narratives that prompt a complex orientation of several categories representing a particular worldview (Hopewell 1987, 72-73).

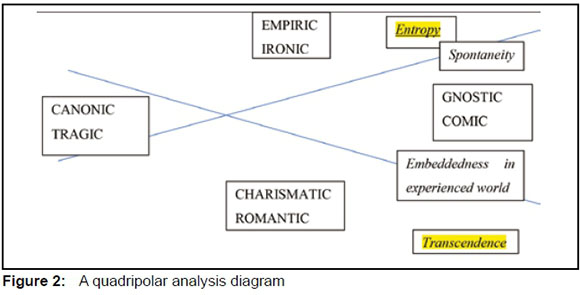

The manner in which we orientate ourselves in relation to these different narrative positions "demonstrates how dependent personal belief is upon the larger imaginative process of humanity" (Hopewell 1987, 73). Both gnostic and charismatic narratives are distinguished from the other categories by spontaneity (Hopewell 1987, 75). Empiric and canon narratives are distinguished from the aforementioned categories by its opposite, entropy.2 Gnostic and charismatic approaches assume the spontaneous inner energy of the known world, whether in the cosmos itself (the gnostic view) or by active spirit (the charismatic view) (Hopewell 1987, 75). Comic and romantic tales are stories of freedom found in the spontaneity of faithful life (Hopewell 1987, 75).

The majority of people and physicists, however, believe that the world is moving toward entropy, its static equilibrium. Denying an inner energy of life, the tragic and ironic stories told about Boesak's incarceration spoke about decline into the dissolution of his role as a liberator (Hopewell 1987, 75). What differentiates the charismatic and canonic approaches to the world from gnostic and empiric negotiations is their sense of transcendence. Both God and the human soul are ultimately distinct from the world. By contrast, the gnostic and empiric understandings find God and self ultimately embedded in the experienced world, finally indistinguishable from its nature. Figure 2 shows this two-way division, and the division between entropy and spontaneity, explored earlier, that crosscut it (Hopewell 1987, 76).

Like tragedy, the canonic asserts the inevitable decline of the self. A charismatic story portrays Boesak's escape from the conventionality of life, whereas the canonic story claims the certainty of life's pattern (Hopewell 1987, 79). Only by realising the certainty of one's fault and by submitting to the total sovereignty of God who controls life, do we resolve the decline. The canon is the final decree (Hopewell 1987, 79): "[T]ragedy seems to lead to up to an epiphany of law, of that which is and must be" (Hopewell 1987, 79). "The canonic Christian beholds a world fated for catastrophe ... Although the canonic narrative develops along a tragic course, its beginning may give no forecast of catastrophic outcome" (Hopewell 1987, 80).

Hopewell's (1987, 69) canonic perspective is similar to Frye's tragic genre, which expresses a certain conservative viewpoint undergirded by an authoritative interpretation of a particular worldview. Who can forget how church leaders demanded Boesak to substantiate his radical viewpoints in terms of Scripture? Boesak, however, maintained his scriptural reformed integrity in most of his deliberations, sermons, and writings by honouring the doctrine of sola scriptura. Boesak's recent book publications, such as Naby jou is die Woord (1996) and Die Vlug van Gods Verbeelding (2005), are excellent examples of his deep grounded faith and skill in the Word of God, and how to interpret it with personal experience, spiritual and contextual integrity, and relevancy for both church and society at present. In these books, Boesak illuminates how he has struggled at times to follow the way of Christ and how he has lived his life "tragically in the shadow of the cross"; how he had to suffer, die to his self, and gain justification only beyond and through Christ's death and his own (Boesak 1996, 3; Hopewell 1987, 61).

For Boesak (2005, ii), the authority of the Bible has been and still is as important as the meaning of the Bible for people, particularly those on the fringes of the powerful circles in our society: the poor, women, the political-disempowered-those who are left voiceless through their ignorance of powerlessness without input in issues that affect their lives-the marginalised, and the destitute.

The Bible stories invite us to make a shift in our own reflections from the centre of power towards the periphery-for this is where the actual meaning of the story is revealed for us (Boesak 2005, v): "The charismatic story begins with discomfort about conventionality. Routine domestic life is judged inadequate, and the self yearns for a more immediate, direct experience of God's power" (Hopewell 1987, 76).

Boesak viewed God and his Word as the ultimate inner energy of life, which inspired, empowered and guided him to discern God's love and faithfulness within his own struggles and plight, while he prophetically voiced his faith and belief in this God for those who remain on the fringes of society.

Following the aforementioned, we concur that the canonic resonates with the tragedy and irony perspectives in Boesak's story, which relates to entropy-the denying of an inner energy of his life, which has led to his decline and dissolution (Hopewell 1987, 75). The canonic resonates with the transcendence-God and human soul distinct from the world-this explains Boesak's resilience and passion for political freedom.

Reality in the gnostic negotiation is ultimately reliable. Narratives that relate to a gnostic perspective usually begin with a depiction of estrangement, but end with the integration of all that was once alienated or indifferent (Hopewell 1987, 73-74). Boesak (1996, 87) exclaims:

As ons lyding ons ineen laat krimp van pyn ... As mense met die vinger na ons wys, skelmpies lag en agter ons rug koggeltekens maak ... As die wêreld ons naak uittrek en ons ten toon stel, en elk wat wil 'n hou mag slaan.

A critical point in a story is the inner knowing (gnosis), which confers an awareness of the way things truly are (Hopewell 1987, 74). Cosmos is true to the reality revealed in consciousness, but finally itself becomes that consciousness (Hopewell 1987, 74). For instance, Heering (in Boesak 2005, 80) inspired Boesak's philosophy of nonviolence.

Sometimes we start our life "journey in bafflement and first look for ultimate meaning in the wrong places toward the blissful pleroma of all that is"-applying positive thinking in search of the wholesome fulfilment of life itself (Hopewell 1987, 75). The gnostic perspective is similar to Frye's comic genre and based upon an intuited process (discernment) of a world that develops from dissipation toward unity. The regeneration of life is what distinguishes it from anything else in this world. We should thus contend that Boesak's humanity, notwithstanding his spirited prophetic and priestly sensitivity and giftedness (Verkuyl in Boesak 1975, 5), serves as re-configurative "power" to forge justice, freedom and unity-and, in particular, a new kind of humanity.

His extramarital affairs and eventual fraud charges reshaped his identity, vision and mission to become the same and maybe more matured sensitive and gifted prophet and priest as pronounced by Verkuyl during 1975 in Paarl. We concur with Hopewell (1987, 69) that "[t]he ultimate integrity of the world requires the deepening consciousness of [Boesak] involved in its systematic outworking and [his] rejection of alienating canonic structures." Boesak reconfigured the discordant entropies in his life and regained spontaneously a new concordance. Likewise, Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, in 2009, after Boesak's short political career, welcomed his decision to quit the Congress of the People (COPE) and to join "God's Party" (Grobler 2009).

Members of the Piketberg Uniting Reformed Church welcomed Boesak back into the fold of the church. This event symbolises an integration of his consciousness and relationship with his original vocation and those alienated by his political career (Oryx Multimedia 2008).

He transformed the entropy embedded in the empiric reality of South Africa, replaced by spontaneity embedded in transcendence. Boesak's narrative offers us a fresh insight into how he was able to configure and reconfigure his life narrative in spite of suffering for the greater good of humanity. Following the aforementioned, we concur that the gnostic perspective in his life relates to the comic and romantic perspectives. His understanding of God and the human soul is embedded in the existential experienced world with an inner energy of the known world grounded in a faithful spirituality of freedom.

The charismatic perspective, similar to Frye's romantic genre, relies on the personal encounter of a transcendent spirit: "The integrity of providence [wisdom] in the world requires that empirical presumptions of an ordered world be disregarded and supernatural irregularities instead be witnessed." The spirit is active in the world, based on personal experiences (Boesak 2005, 139; Hopewell 1987, 75).

Our existential experience and context can become simultaneously a frightening and a thrilling reality (Hopewell 1987, 76). The world gives paradoxical signals (Hopewell 1987, 76). "Die ontmensliking van die een bring ook onvermydelik die ontmensliking van die ander mee. Die pyn van die onderdrukte word weerkaats in die gebrokenheid van die onderdrukker se menslikheid" [transl. The dehumanising of one invariably brings about the dehumanising of the other. The suffering of the oppressed is reflected in the broken humanness of the oppressor.] (Boesak 2005, 5). The source of integrity is God. The world is fundamentally equivocal and dangerous; we are living amidst the perils of evil forces and events (Hopewell 1987, 76).

It is so easy to forget the role Boesak played during the dark days of apartheid. He and Tutu led the sanctions campaign against the apartheid regime, which ultimately brought us our democratic freedom. Boesak inspired millions of people and gave them hope that apartheid would end in their lifetime (Fischer 2009). "He was a leading opponent of apartheid in South Africa. South Africa continues to see Reverend Boesak work as an articulate cleric-politician" (Cowell 1985). Boesak has been and still is an inspiration for the marginalised and a fearful activist who "inflames passions" or represents a challenge to those in powerful positions (Cowell 1985).

Boesak espoused the ability to inspire millions with his spirited disposition grounded in the transcendent spirit of God, while empowering the oppressed to consider a future free from oppression and struggle.

Following the aforementioned, we concur that the charismatic perspective in his life relates to the gnostic and romantic perspectives. His understanding of God and the human soul is embedded in transcendence with an inner energy grounded in a spirited faithful spirituality of freedom. Like the canonic approach, the charismatic approach to the world is characterised by its sense of transcendence. Both God and human soul are ultimately distinct from the world; thus, his unfailing trust, faith and belief in the transcendence of God's will and ultimate sovereignty.

The empiric observations of the world can be reduced to scientific propositions, but their form in community discourse is narrational (Hopewell 1987, 82). A story is as emotionally compelling as determined by the circumstances within its empiric setting (Hopewell 1987, 82). In contradicting sacred explanations, one finds within human community itself the true mystery of life (Boesak 2005, iv).

Integrity of others' worldviews found in cosmic wholeness is suspect in an empiric understanding (Hopewell 1987, 82). The locus of integrity is within human society itself (Hopewell 1987, 82). An empiric story rejects examples of supposedly superior piety and proposes instead a reasonable loyalty to God and fellow human beings (Hopewell 1987, 83):

Ek weet: dié wat in die put sit, sien geen heil nie, net die donker. Dié wat deur die pyn verniel word, tel nie God se beloftes nie, net die slae. Maar geloof is vashou aan die dinge wat ons nie kan sien nie [transl. I know: those who find themselves in the well do not see any light, only darkness. Those who are shattered by the pain do not count God's promises, only the hurt. But faith means to hold on to those things we cannot see.] (Boesak 1996, 91).

According to empirically oriented literature, Frye takes for granted a world that is full of anomalies, injustices, follies, and crimes, and yet is permanent and fixed. Its principle is that everyone who wishes to keep his/her balance must first learn to keep his/her eyes open and his/her mouth shut (Hopewell 1987, 83). The empiric perspective is similar to Frye's ironic genre undergirded by the verification of objective data based on the five human senses. Boesak's integrity, in some instances, may have required a measure of realism about what righteousness and equality in a new South Africa could be like-was it possible that he, at some point in his life, may have rejected the reality and workings of the supernatural? (Hopewell 1987, 69):

Vertroue in mense is tot in die fondament geskok, vriendskappe het verbrokkel soos ou mure wat met klei gebou is. Die pers het met ons omgegaan soos mense wie se menslikheid nie tel nie ... Hoe praat 'n mens in die openbaar as jy bespot word oor elke woord wat jy oor jou geloof in God sê? [transl. Trust in people had been shaken to the core, friendships disintegrated like ancient walls of clay. The media dealt with us like people whose humanness does not matter ... How do you speak in public if you are ridiculed on every word you utter about your faith in God? (Boesak 1996, 4-5).

Boesak held an innate ability to analyse any given situation with a clear sense of what was happening, and could embody, articulate and mirror the suffering of the total struggle of humanity.

Following the aforementioned, we concur that the empiric perspective in his life relates to the tragic and ironic perspectives. His understanding of God and the human soul is embedded in the experienced world, characterised by entropy, a static state of equilibrium-denying him his characteristic inner energy for life. Like the empiric approach, the gnostic approach to the world is characterised by an understanding that God and self are embedded in the experienced world-a world full of anomalies, injustices, follies, and crimes.

Therefore, to choose any one singular perspective of Boesak's narrative will leave the reader with a narrow, simplistic, and incomplete plot. The significance of Boesak's life narrative illustrates his nature and role as a transformational black liberational theologian.

According to Van den Brand, Scherer-Rath and Vershuren (2013, 104-107), narratives construct our heterogeneous life events, goals, and motivation in an order or a plot. It is about the social construction of our reality. The self-narrative motivates leaders to make certain choices that lead to certain types of actions, which are driven by their motives; their intentionality to act or make decisions.

We have explored the connections of what Boesak did as a spiritual and value-based leader. The notion of contingency was crucial in his life. It reveals how he has created fragile meanings of understanding that have revealed how we can understand ourselves in a certain manner. Life narratives are always in contingency. A break in our life order is a contingency (the unexpected events of life; it just happened; it need not happen, but it happens). Therefore, we are in need of reconstructing our life narratives, of reordering or reconstructing the different building blocks of our life narratives in a meaningful order. We have explored the contingency in Boesak's implicit and explicit narratives about moments of change in his life. Contingency is based on different life goals in, and through situational, existential and spiritual experiences.

Following the semantic square and quadripolar analysis, we have also observed how he himself linked or motivated his self-narrative with his intentionality in making choices and acting upon them. In moments of change, people can achieve an awareness of who they are, and who they are in terms of their life narrative and spiritual fullness. In that change there is always form so that people can attain understanding through form (joy or suffering) or discover their identity, mission, vision, or life goal.

Meaning, identity or values assist leaders in reaching spiritual fullness or ultimate life goals. Our ultimate life goals come from situational, existential and spiritual contingencies, which are based on a foundation beyond our own immanent active or passive lives. It is clear that Boesak's ultimate life goals were always grounded in the transcendence of the living God (Van den Brand et al. 2013, 104-107).

The irony of Boesak's narrative is captured by the bipolar tension between his vision and mission for freedom from a violent and hegemonic static state of equilibrium-his inner spirited energy-and the politically engineered denial of that very same energy of life, which has characterised him. In light of the quadripolar tension in his lived narrative, the question arises: What inspired and sustained his vision and mission?

IN SERVICE OF HUMANITY

Boesak's entire life and mission, we need to admit, were to advance the human rights and dignity of the marginalised in the world. He was prepared to suffer as a consequence, and even struggled with God himself: "Why is it that God thinks that I am stronger than what I am? Is suffering and tribulation a sort of reversed compliment of God to us: the stronger the suffering, the stronger I think you are?" (Boesak 1996, 3). Wolterstorff (2014) undergirds Boesak's dilemma: "Allan Boesak affirms the hope of Christians for the Age to Come, but the hope of which he writes in this book is different. The hope here is the hope for justice in this present age."

This was certainly the experience of the collective during the dark days of apartheid, which offered little comfort and hope that the sense of God's silence and apathy forced us to question the realisation of justice from an evil unjust system.

Hopewell's (1987, 73) subsequent theory is of significance for Boesak's life narrative: "One's singular position expresses and requires the total struggle of humanity for meaning. It does not feature alone or outside, in judgment of the whole. One finds in any person's world view, the full range of human imagination." In this regard, it is best to allow Boesak to demonstrate how his own single position embodies the "total struggle of humanity [as] a complete view of human imagination":

Black theology3 teaches us that theology cannot be done in a void ... It is rather the result of a painful and soul-searching struggle ... with a black history-a history of suffering, degradation, and humiliation through white racism (Boesak 1980).

The poorest of the poor are still shouting for righteousness, while the church is mourning about the satisfaction doctrine and evolution (Boesak 2005, i). It is the weak who determine the course of history, because God chooses the side of the weak and fights their fights. Where the voice of the weak is silenced is where the voice of God is heard the clearest (Boesak 2005, iv; 1977, 127).

Black theology or black consciousness refers to one choice for, and one deed of solidarity, which includes all the different ethnic groups in the black community who share in the solidarity of the oppressed. Its intent is to dismantle the walls of apartheid's inspiration of false consciousness between "kleurlinge", "Indiërs" and "Bantoes". Blackness is a discovery, a mentality, a conversion, a confirmation of the self; in other words, power. It is an insight in terms of wisdom and responsibility of blacks to transform South Africa in which black and white can live in peace (Boesak 1977, 120). Black theology is one perspective of contextual theology, a theology that develops out of the praxis of participation for the liberation of people and societies in one particular context (Verkuyl in Boesak 1975, 6) for total liberation towards the fullness of life in the past, present and future (Boesak 1977, 121).

The search for the liberation of blacks does not exclude, but includes whites. They are also victims of their own evil system, although in another sense. Black theology seeks to serve the authenticity of humanity. The responsibility of blacks is to ensure that our blackness does not become a sign of less humanity or degraded humanity (Boesak 1975, 10). Black theology seeks to communicate the message of human authenticity to whites-future white and black generations must not learn and live from, and of any theology, which also wants to be an addition of cultural imperialism (Alves in Boesak 1975, 27):

Die kerk in Suid-Afrika sal veroordeel staan oor die onfatsoenlike haas waarmee apartheid vergeet is en die gevolge daarvan doodgeswyg word. Nie omdat daarmee die bedrywers van apartheid so gou vergewe is nie, maar veral omdat daarmee die slagoffers van apartheid so gou na die vergetelheid verwys is [transl. The church in South Africa will stand adjudged about the shameful haste in which apartheid was forgotten and how the consequences of it were hushed. Not that this has brought forgiveness to the agents of apartheid, but especially because it has swiftly consigned the victims of apartheid to oblivion.] (Boesak 1996, 99-100).

"We have buried the ghosts of racism, ethnocentricity and narrow tribal nationalisms in a grave so shallow they rose to haunt us at the slightest provocation" (Elna Boesak in Boesak 2014, 1071). We should reclaim, as with the struggle against apartheid in the 1980s, the spirituality of politics inspired by prophetic faithfulness, and infused with sacrificial commitment as with the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s (Boesak 2014, 1062).

REFERENCES

Arrison, E. 2012. "Posts tagged 'Allan Boesak': Remembering the launch of the UDF on 20 August 1983." https://kairossouthafrica.wordpress.com (accessed 2 June 2015). [ Links ]

Associated Press (AP). 1985. "Boesak vows to keep resisting Apartheid." www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 8 June 2015). [ Links ]

Boesak, A. (ed.). 1975. Om het Zwart te Zeggen: Een Bundel Opstellen over Centrale Themas in de Zwarte Theologie. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Boesak, A. 1977. Afscheid van de Onschuld: Een Social-Ethische Studie over Zwarte Theologie en Zwarte Macht. Kampen: Kok. [ Links ]

Boesak, A. 1980. "The Black Church and the Struggle in South Africa." Address at the National Conference of the South African Council of Churches in July 1979. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111.j.1758-623.1980.tb03249.x/abstract (accessed 6 June 2015). [ Links ]

Boesak, A. 1996. Naby jou is die Woord: Bybelse Oorwegings in 'n Tyd van Aanslag. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Boesak, A. 2005. Die Vlug van Gods Verbeelding. Stellenbosch: Sun Press. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781920689391. [ Links ]

Boesak, A. 2014. "Hope unprepared to accept things as they are: Engaging John de Gruchy's challenges for Theology at the Edge." Nederduitse Gereformeerde Teologiese Tydskrif 5 (1): 1055-1074. [ Links ]

Butler University. 2013. "Biography of Allan Boesak: Desmond Tutu Chair of Peace, Global Justice or Reconciliation Studies at Butler University and Christian Theological Seminary." www.butler.edu.com (accessed 5 June 2015). [ Links ]

Christian Theological Seminary.2013. "Allan Aubrey Boesak: Desmond Tutu Chair of Peace, Global Justice and Reconciliation Studies. Christian Theological Seminary. Indianapolis, IN." http://www.cts.edu/faculty/cts-faculty.aspx?StaffId=28 (accessed 5 June 2015). [ Links ]

Cowell, A. 1985. "Man in the News: A Fiery Foe of Apartheid: Allan Boesak." http://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/28/world/man-in-the-news-a-fiery-foe-of-apartheid-allan-boesak.html (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Department of Information and Publicity (DIP).1992. "The appointment of Dr Allan Boesak." http://www.anc.org.za/show.php?id=8313 (accessed 5 June). [ Links ]

Encarta Dictionary: English (North America). 2015. www.MSW.com (accessed 10 June 2015). [ Links ]

Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2010. "Allan Aubrey Boesak facts." http://biography.yourdictionary.com/allan-aubrey-boesak (accessed 1 June 2015). [ Links ]

Fischer, R. 2009. "Understanding Allan Boesak." http://www.thoughtleader.co.za/rylandfisher/2009/11/05/understanding-allan-boesak/system (accessed 6 June 2015). [ Links ]

Grobler, F. 2009. "Welcome to 'God's Party': Tutu tells Boesak." http://mg.co.za/article/2009-11-03-welcome-to-gods-party-tutu-tells-boesak (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Hopewell, J. F. 1987. Congregations and Structures. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Jones, J. 1987. "Activist South African Cleric Boesak honoured for Anti-Apartheid Effort." www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Kotze, H., and Greyling, A. 1991. "Political Organisations in South Africa A-Z." Tafelberg: Cape Town. http://www.sahistory.org.za/pages/people/boesak-a.htm (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Mail & Guardian. 2009. "Boesak holds back Book over ANC Names." www.mg.co.za (accessed 8 June 2015). [ Links ]

Mathews, J. 1985. "South Africa: Bomb explodes in High School: Doctor Allan Boesak appeals for relaxation of Bail Restrictions/Violence in Johannesburg Streets." http://www.itnsource.com/shotlist//RTV/1985/10/25/BGY601250344/?s=boesak (accessed 9 June 2015). [ Links ]

Oryx Multimedia. 2008. "Allan Boesak resurrection 2005." www.oryxmedia.co.za (accessed 9 June 2015). [ Links ]

Parratt, J. 1995. Reinventing Christianity: African Theology Today. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Reuters. 1996. "South African Cleric charged with theft from Donors." Los Angeles Times. www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 8 June 2015). [ Links ]

Ricoeur, P. 1991. "Life in quest of Narrative." On Paul Ricoeur. Narrative and Interpretation, edited by D. Wood. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Robert. F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights. 1985. "Allan Boesak, Beyers Naudé and Winnie Mandela, South Africa: Ending Apartheid in South Africa." http://rfkcenter.org/allan-boesak-beyers-naude-a-winnie-mandela-south-africa-3 (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Ruden, S. 2000. "What happened to Allan Boesak? Corruption in SouthAfrica." http://www.christiancentury.org/category/keywords/allan-boesak (accessed 5 June 2015). [ Links ]

Simmons, A. M. 2001. "A Disgraced Activist wins his Freedom." Los Angeles Times. www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 8 June 2015). [ Links ]

South African History Online (SAHO). 2015. "Towards a People's History. Reverend Allan Aubrey Boesak." http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/reverend-allan-aubrey-boesak (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Times Wire Services.1985. "South Africa jails Boesak: Key apartheid foe." Los Angeles Times. www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Times Wire Services. 1990. "Boesak quits World Church Post: Boesak resigns as President of World Calvinist Church Group." Los Angeles Times. www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 8 June 2015). [ Links ]

Tolkien, J. R. R. 1995. The Lord of the Rings. London: Harper Collins. [ Links ]

United Press International. 1986. "Police barged into Church Service: Boesak says." Los Angeles Times. www.articles.latimes.com (accessed 7 June 2015). [ Links ]

Van den Brand, J., Hermans, C., Scherer-Rath, M., and Verschuren, P. 2013. "An Instrument for Reconstructing Interpretation in Life Stories." In Religious Stories we live by: Narrative Approaches in Theology and Religious Studies, edited by R. R. Ganzevoort, M. de Haardt and M. Scherer-Rath. Leiden: Brill, 169-182. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004264069_014 [ Links ]

Wolterstorff, N. 2014. "After Good Friday comes Easter." Nicholas Westerhoff on Allan Boesak's Dare We Speak of Hope? Eerdword, the Eerdmans blog. http://eerdword.com/2014/04/08/after-good-friday-comes-easter-nicholas-wolterstorff-on-allan-aubrey-boesaks-dare-we-speak-of-hope/ (accessed 10 June 2015). [ Links ]

1 All the elements in a well-constructed story can help reformulate the relation between life and narrative. A plot, according to Aristotle, is not a static structure, but an operation, an integrating process-is completed only in the reader or in the spectator-in the living receiver of the narrated story (Ricoeur 1991, 21). Aristotle held that every well-told story has pedagogical value and illuminated universal aspects of the human condition (Ricoeur 1991, 22-23).

2 Entropy refers to a measure of the disorder that exists in a system; a lack of the energy in a system or process to make it work; and communication errors occurring in the transmission of signals, the ultimate efficiency of transmission systems (Encarta Dictionary 2015).

3 The most sustained exposition of black theology to come out of South Africa under apartheid was Allan Boesak's Farewell to Innocence. He describes his book as a "socio-ethical study on black theology and power", and it is his conviction that black theology "as reflection of the praxis of liberation within the black situation must have an ethic of liberation." Black theology is essentially a situational theology, determined by "the situation of blackness." Blackness embraces the whole of black people's existence. "It determines their way of life, which in South Africa excludes them from the privileges enjoyed by whites and from a truly 'human' life" (Parratt 1995, 174).