Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265

Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.42 n.2 Pretoria 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2412-4265/2016/622

ARTICLES

Religious pluralism and disability in Zambia: approaches and healing in selected Pentecostal churches

Nelly MwaleI; Joseph ChitaII

IUniversity of Zambia, Department of Religious Studies nelmwa@gmail.com

IIUniversity of Zambia, Department of Religious Studies chonochitajoseph@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Zambia has recently witnessed the growth of Pentecostal churches that publicly make the claim of being able to heal disabilities. This paper explores how some Pentecostal churches in Zambia's pluralist society claim to be healing disability. Interviews, documents and video recordings from three different Pentecostal ministries depicting healing and disability, were analysed. The paper observes that some Pentecostal ministries exemplify disability as that which could be healed through the work of the Holy Spirit; and disability is attributed to the work of the devil. The paper argues that these disability healing messages and miracles indirectly victimise people with disabilities, despite their potential to offer social capital. This has created a need for deconstructing views on disability. Disability issues in the church also have to go beyond healing and miracles, to appreciating the contributions that people with disabilities can make to the body of Christ.

Keywords: Zambia; disability; healing; Pentecostal; people with disabilities; religious pluralism

INTRODUCTION

Pentecostalism is one of the fastest growing movements worldwide (Burgess 2006) and some of its main attractions are miracles and healings. In Pentecostal healing services, paralytics arise from their wheelchairs, stiff knees become flexible, cancerous ulcers disappear, and headaches vanish, among other things. Speakers or preachers also foretell healings that are taking place in the audience, often prophesying the types of problems of the audience. Healings and miracles are therefore highly valued in Pentecostalism and the charismatic movement (Anderson 2002; Warrington 2006). Individuals bestowed with the gift of healing, as well as those divinely healed, enjoy 'high' status. The miracles and healing are said to be rooted in scripture (Isaiah 53:5 [By his stripes we are healed]; Matthew 8:1; or 1 Corinthians. 12:9, 28, 30) and are reported to be occurring on a regular basis, both in healing services and in everyday life in the public media.

Different scholars have since responded to this phenomenon and studied Pentecostalism from different perspectives. Anthropologists have largely focused on a descriptive and interpretive dimension of healing (Csordas 1988), and have mainly taken a positive view. Other schools of thought, especially the critical scholars (Thomas 1999), have critiqued this healing and depicted Pentecostal healings as fraudulent and socially harmful events. They have also questioned whether Pentecostal healing 'works', using biomedical criteria, resulting in negative descriptions of this healing.

In Zambia, healing and disability are themes, which have been neglected in Pentecostal scholarship, as studies have concentrated on other aspects. Pentecostalism became popular in Zambia after the 1990s and factors accounting for this growth have been studied (Cheyeka 2005; 2008; Udelhoven 2010; Kroesbergen 2013). There is, therefore, a dearth of both empirical and theoretical research on disability and healing in Pentecostal churches in Zambia. This paper attempts to make a contribution to disability and Pentecostal studies by arguing that the representation of disability and healing in the public space has implications for those seeking healing, as it can give them false hope or take advantage of them in the process. Without doubting whether the healing is real or not, the research on which this paper is based, sought to investigate Pentecostal approaches to disability and healing, and in turn will explore the implications in a religious pluralistic society like Zambia. The paper adds the concept of 'shopping for healing' to the Pentecostal healing discourse.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES

A qualitative research design was used with an interpretivist paradigm as a lens to analyse raw data. In this paradigm, the reasons for research are to understand and describe the meaning of social action, interrogate how the phenomenon is socially constructed and to ascertain how meaning is negotiated in the context of the study (Creswell 2007). Unlike starting with a theory (as is often the case with post-positivism), inquirers generate or inductively develop a theory or pattern of meaning (Lincoln and Guba 2000). Therefore, the aim of the study was to explore Pentecostal approaches to disability healing in a pluralist Zambian society and to examine the implications of such approaches.

Six video recordings from three different Pentecostal ministries (Healing Voice International Ministries of Prophet Elijah, B. Chali; Prophet Anointed Andrew of Christ Freedom Ministries; and Miracle Life Ministries of Prophet John General) - all depicting healing and disability - were analysed using a critical perspective (emancipation). This was supplemented by documentary analysis and interviews. The recorded interviews were drawn from people who had attended any of the mentioned three Pentecostal ministries' healing sessions in the previous six months. The purposively sampled interview respondents were six and represented both males and females. Pseudo names have been used to protect the participants' identity. The video recordings and the televised healing sessions of the three Pentecostal ministries from 2014 to 2015 were reviewed too.

The central question which the paper sought to address through the analysis of documents, videos, and interviews was centred on how selected Pentecostal ministries were depicting disability in the public space, and what approaches to disability healing were being used in the selected ministries in a religious pluralistic society. Emerging themes were categorised, interpreted and checked for consistence with the videos. The sample was drawn from Pentecostal ministries that had broadcast their healing sessions (videos) in the public media. The messages in the adverts pertaining to disability were examined, including the televised healing sessions. In order to overcome bias of what was presented in the televised healing sessions (owing to the editing effects), live broadcasts of the healing sessions were observed too. Being a case study which focuses on selected Pentecostal ministries in Zambia, the findings of this paper are not for purposes of generalisation, but may be used as stepping-stones in understanding the different representation of disability and healing in the public space.

CONCEPTUALISATION OF TERMS

Religious pluralism

The paper acknowledges that several scholars in varying contexts have defined religious pluralism differently. Broadly speaking, pluralism describes the fact that the neighbourhood of people of various origins, cultures, religions, and value-systems characterises society in the modern and global world. When applied to religion, it indicates the diversity of religious faiths in a given society and in the world (N'diaye 2008). Nash (1994) defines pluralism as the belief that Jesus is not the only Saviour, and this implies that there is not merely one way but a plurality of ways of salvation or liberation. In this paper, religious pluralism is therefore limited to the diversity of religious faiths in which adherents of these different faith traditions are free to express their beliefs (Boston College Centre papers) - and we focus on the denominational level.

Zambia, like many other countries, is a multi-faith society. Though Christianity is the dominant religion with its numerous denominations, other religions like Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Bahai, and African Traditional Religions also co-exist. Statistically, the 2010 census of population and housing reported 12 750 000 Christians of which 2 750 000 were Roman Catholic, 8 870 000 were Protestant, 20 000 were Orthodox, and 1 110 000 were various other Christians (CSO 2010). Cheyeka (2014) reported that of Zambia's population (14 222 000), 95.5 per cent were Christians, 0.5 per cent were Muslims, 0.1 per cent were Hindus, while other and non-affiliated categories accounted for 2 per cent and 1.9 per cent respectively.

In addition, Zambia was declared a Christian nation and this is enshrined in the Constitution as of 1996. This declaration has contributed to the growth of Pentecostal churches in the country in diverse ways, which have been extensively explored (Cheyeka 2005; Zulu 2013) among others. Zambia's Christianity is also spoken of in terms of mother bodies, which include the Evangelical Fellowship of Zambia (EFZ); Episcopal Conference of Zambia (ECZ); Council of Churches in Zambia (CCZ); and Independent Churches Organisation of Zambia (ICOZ).

Udelhoven (2010) in his study, Changing face of Christianity in Zambia, depicts the pluralistic nature of the Zambian society and notes that by 2010, Bauleni (one of the residential areas in Lusaka) was estimated to have had 82 different churches or denominations, seven of which were affiliated with the Christian Council of Churches in Zambia (the mother-body of Protestant churches in Zambia), 18 were affiliated with the Evangelical Fellowship of Zambia (EFZ), and at least one was affiliated with ICOZ (Independent Churches of Zambia) - the rest were Pentecostal. These developments, which occurred in Bauleni, were also acknowledged in other parts of the country. Suffice to state that Christianity has been pluralistic in Zambia from its beginning. This can be attributed to the missionaries who are said to have forced Africa to accept a divided God, since these messengers of God were already divided even before they came to Zambia, as Byamungu (2001) observed. The severe competition among the different missionary churches, therefore, laid a foundation on which pluralism thrives today.

However, Udelhoven (2010) argues that with reference to Zambia, a remarkable tolerance towards different Christian doctrines and traditions has been shown, since people never believed in a divided God. For most Zambians, God is not divided (Lesa aba fye umo! 'Mulungu ndi mmodzi!'), and therefore transcends any individual church. It is for this reason that people unite with each other and support each other far beyond the boundaries of any church.

Without historicising the growth of religious diversity in Zambia, this paper has focused on how religious pluralism contributed to the popularity of healing in Pentecostal churches. In order to limit our perspective, we have explored and situated disability and healing in the Pentecostal context in order to understand the implications of the status quo, vis-a-viz inclusiveness in the church. The paper will also seek to establish how Pentecostal portrayal of disability and healing has promoted 'shopping for churches' in the country's highly urbanised city, Lusaka.

DISABILITY

According to the World Health Organization estimates, about two million women and men in Zambia, or 15 per cent of the population, have a disability (World Bank 2011; 2012). A higher percentage of people with disabilities live in rural areas where access to basic services is limited. A 2 000 Population and Housing Census, which collected data on disability, reported that a large percentage of people with disabilities are self-employed in agriculture, making it by far the most common occupation (CSO 2000).

The majority of people with disabilities live in poverty, and generally with unproportionally low literacy levels compared to persons without disabilities. People with disabilities often have to resort to street begging as a means of survival. The government has since adopted a number of laws and policies pertaining to people with disabilities. These include: the Zambian Constitution; the Technical Education, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training Act 1998; The Workers' Compensation Act No. of 1999; the National Policy on Education 1996; Vision 2030; Sixth National Development Plan; and the Persons with Disabilities Act of 2012, including International treaties and conventions to which Zambia is a signatory.

Disability also has different definitions. In this regard, disability means a permanent physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairment that alone, or in combination with social or environmental barriers, hinders the ability of a person to fully or effectively participate in society on an equal basis with others (Zambia Disability, Act. No. 6 of 2012). Rapheal (2004) defines it as functional limitations that result from a combination of impairment and social environment. Disability is, therefore, an umbrella term covering impairment, activity limitations and participation restrictions. In this paper, disability was not limited to medical perspectives but was extended to social perspectives, which calls for advocacy and inclusiveness especially in relation to religious inclusiveness.

Concerning disability and inclusiveness in the mainline churches, persons with disabilities have often been neglected as reflected in disability-unfriendly church buildings, lack of sign language interpreters and other facilities. The mainline church buildings have not created room for people with disabilities and this is in contrast to the Pentecostal churches that seem to have embraced people with disabilities in the church. This is not to take away any credit from the mainline churches such as the Roman Catholic Church and others who have responded to disability by establishing home-care centres (Cheshire homes) and rehabilitation centres. The dilemma is that an examination of mainline church membership does not reflect inclusiveness. Again, this is not to say that the Pentecostal churches have successfully done this, for reports of stigma against people with disabilities have emerged from within the Pentecostal churches owing to the association of disability with sin, a curse, witchcraft, and demons (Mustwanga et al 2015). Therefore, Pentecostal response to disability in the context of an inclusive church is not without challenges. While we acknowledge that disability is diverse, we interrogate the physical disability depicted in selected Pentecostals churches.

HEALING

In common speech, the term 'healing' is usually used to mean the restoration of health and this raises the immediate question of the ambiguous concept of what is referred to as health. Wilson wrote: 'Health is a concept like truth, which cannot be defined, and to define it is to kill it' (Wilson 1975). Healing can also be understood as the restoration of the appropriate functional wholeness. Healing is further posed as restoration of a person's sense of his or her own wellbeing or the removal of that which prevents an individual from functioning according to society standards. Most importantly, healing takes place in a social context.

The place of healing in the Christian faith is as old as the faith itself. In the post-Pentecost church, the apostles did many signs and wonders among the people (the 'signs of a true apostle', 2 Cor.12:12; Rom. 15:19), and the sick and those afflicted with unclean spirits were healed (Acts 2:43; 3:6; 5:12-16; 28:9). Perhaps what has changed is its focus, justification and how it is done. Needless to note, the Pentecostal churches, from their beginnings at the turn of the century in the Holiness movements and the Welsh revival of 1904, have always included the 'ministry of divine healing' as part of their teaching. This came to particular prominence in the great evangelistic campaigns of the 1920s (the Albert Hall was filled each Easter Monday from 1926 to 1939 for such an event) in which divine healing was closely linked to evangelism. The Pentecostal doctrine that there is healing in the Atonement (that Christ bore our sicknesses as well as our sins on the cross) is central to this practice.

PENTECOSTAL HEALING APPROACHES

Pentecostalism is a Christian movement that takes its name from the event of Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit descended on Christ's first disciples and they were 'baptised in the Holy Spirit' (Johnston 2008). Pentecostalism, therefore, refers to the spirit type churches, which emphasise the doctrine of glossolalia; the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. At its core is usually a re-conversion experience called 'baptism in or with the Holy Spirit', whose origin is traced to the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the first Christians in Jerusalem on the day of Pentecost, or Shavuot (Acts of the Apostles 2-4), (Johnston 2008).

Today, Pentecostalism includes several subtypes and categories that reflect different emphases of belief and forms of organisation. As earlier alluded to, the development of Pentecostalism in Zambia has been explored at length, but perhaps the diversity and characteristics of the upcoming Pentecostal churches may need to be redefined in relation to the core values of Pentecostalism.

Literature on Christian healing suggests a variety of approaches to healing and these include: medical approaches; psychotherapy or pastoral counselling; inner healing or prayer counselling; Pentecostal healing or evangelism; charismatic or corporate ministry; deliverance ministry; holistic approaches; community care; and public health (Atkinson 1993). Others have categorised the healing forms into diaconal (especially taking place in mainline churches), faith healing in Pentecostal and charismatic churches and ritual healing associated with African Independent Churches (Landman 2015).

This paper focuses on Pentecostal healing or evangelism in order to understand how disability is represented and healed in the Pentecostal churches. In this paper, the concept of healing is limited to divine healing because it emphasises that God's love, rather than merely human faith or an impersonal spiritual force, is the source of healing. It also underscores the perceived need for supernatural intervention instead of implying that faith is a natural force that can be manufactured by human will; and it emphasises that the object of faith, not simply the degree of faith or spirituality, matters in receiving healing (Cox 1995).

Since the 1920s, Pentecostal doctrine has linked a public ministry of healing with public proclamation of the gospel with the understanding that Christ is saviour and healer, and healing is an essential part of evangelism. As early as the 1960s, Gee (1967) observed that though there were frequent testimonies to divine healing at Pentecostal campaigns, there were a small number of definite miracles of healing compared to the great numbers who sought for prayers. Pentecostalism also emphasises prayer for physical healing, as well as emotional and spiritual healing. This healing has been thought to be of benefit to the ill person, and it is also closely linked to public healing ministry and public proclamation (just as 'many signs and wonders were done among the people by the hands of the apostles' Acts. 5:12).

Contextualisation of the study

Disability and health in Zambia, and particularly Lusaka, are closely linked to a wider framework of religion and social reality (Mildnerova 2010). Disability is, therefore, conceived in broader terms as a sort of misfortune or bad luck caused by the intervention of different invisible powers such as spirits, demons, ghosts and witches. It is believed that the invisible powers penetrate the whole of life and significantly influence health, fertility, wealth and social relations. While to some extent the traditional total rejection and segregation of people with disabilities have been influenced by Christian values, the decline of traditional kinship solidarity networks in urban settings has had its own impact on disability and healing.

As Mildnerova (2010) notes, the kinship solidarity network seems to be in decline in contemporary Lusaka urban settings, and in this context, others like neighbours and church communities or groups play an important role in the negotiation and maintenance of a patient's health. It is here where the Pentecostal churches have found a role in responding to disability. The reasons for the disability are found in the relationship between human beings and their environments and ultimately God (Mbiti 1991). The physical environment, which is expressed in food prescriptions and sex taboos that pregnant women must observe, explains disability. By this reasoning, the non-observance of these taboos leads to disability. For example, pregnant women may not eat the meat of sheep as it can cause a child to be weak and unable to hold up the head (Personal interview, Mama Zimba, 28 January 2015). The conceptualisation of disability is, therefore, closely related to the African worldview.

Another cause for disability is sorcery and it is believed that disability is due to unsound relationships in the family, as it is understood that sorcerers attack in families where there are quarrels. In this way, disability comes as a punishment for their weak moral state and the occurrence of disability in the family is the starting point for inquiry into the relations of the family. In instances where a disability is obvious at birth, it is attributed to sorcery and to witchcraft only when there is a clear remembrance of bad family relations, as it is assumed that a sorcerer does not have access to the womb of a pregnant woman (Personal interview, Mama Tembo, 28 February 2015).

Therefore, the relationship with the ancestors becomes cardinal (Colson, 2006). Ancestors are thought to be respected during the burial rituals and one who is not buried with due respect can be reborn into a child with a disability to manifest anger. On the whole, when the ancestral rules are not well respected as in the case of adultery and theft, the ancestors may manifest their anger towards the members of the family through the birth of a child with a disability; here disability is seen as punishment for bad behaviour.

Bride wealth also explains the occurrence of disability in the family. In this instance, when the goods, which are given by the family of the man to the wife as part of the marriage arrangement, are not well-received, it will result in having a child with a disability. The disability in this case would also be due to the woman's family holding a grudge against the man.

Most importantly, and where the cause of the disability cannot be explained in social-familial terms, God as absolute and unknown force remains as the only possibility and final cause (Personal interview, Bwalya, 27 February 2015). God is considered as the source of everything, good and evil, and He can give a family a child with a disability. To show this presence of God in disability, many proverbs and wise sayings are used. For example Chewas say: 'seka pa munthu wosauka, osa kuseka pa munthu wolumala; Mulungu amalenga' (Laugh at a poor person; don't laugh at a disabled person; God still creates). The religious nature of Africans makes these sources of curses plausible (Mbiti 1970; Diop 1989). When examined, all the explanations for disability are centred on harmonious relationships with God, the ancestors and the present and future descendants, on the one hand; and that of parents, uncles and aunts, grandparents, children, siblings' children, neighbours and so on, on the other.

In this relationship, to dishonour the ancestors and or God is a major transgression and the belief in the retributive power of the ancestors and God to the present and future generations is strong to the point that when disability occurs, it means the ancestors and God are not happy (Albrecht 1999; Devlieger 1999). The human relationships can be broken, either through moral wrongdoing (for example not complying with sex taboos when a woman is pregnant, incest, etcetera) or bad personal relations (resulting in curses, sorcery) (Ogechi and Ruto 2002).

This understanding of disability in African religious cosmology is imperative in comprehending Pentecostalism's response to disability, because as Biri (2012) notes, Pentecostalism does not offer anything new completely; but that which it offers either resonates well with or is sourced from the historical religious and cultural background of the believers.

Findings and discussions

The research study that forms the basis of this paper focused on three Pentecostal church leaders (prophets and pastors) and their ministries in order to establish how they approached disability and healing in the public space. The selected Pentecostal church leaders were Prophet Elijah B Chali of Healing Voice Ministries; Prophet Anointed Andrew of Christ Freedom Ministries; and Miracle Life Ministries of Prophet John General. Healing Voice Ministry for All Nations (headed by Prophet Elijah Chali) was founded in 2005 and their mission is "total war against all forces of darkness for the Glory of the Kingdom of God almighty through the power of Jesus Christ of Nazareth". Christ Freedom Ministries started in April 2012, with their international headquarters in Imi State Nigeria under the leadership of Rev. Berthram Gabriel. Miracle Ministries International started Operations in 2008 by Prophet Bishop John Nundwe, known now as Bishop John General. All the prophets were persons without disabilities and they conducted their healing sessions in the public arena (stadiums and school grounds). However, healing sessions were not restricted to the aforementioned public spaces, but extended to admission wards at health institutions. Before the healing sessions, they all advertised the forthcoming healing sessions on billboards, television stations and social media.

The nationality of the prophets under consideration corresponded to the nature of Zambian Pentecostalism in which the majority of prophets are from West African countries. For example, Healing Voice International for All Nations and Christ Freedom Ministries were closely linked to Nigerian Pentecostalism. The foreign prophets have found fertile ground for growth in Zambia due to the religious pluralistic nature of the Zambian society, which has been attributed to the declaration of Zambia as a Christian nation, and social-economic conditions. As Soko (2013) argues, Zambia (dziko la chonde) has proved to be a fertile land for many new mushrooming churches.

These prophets were also young men who were not limited to a particular area in the country, but their works had a nationwide character as they operated in different parts of the country. The character and age of these prophets are not new in Zambia and this relates to Ranger's work on anti-witchcraft movements in which Ranger (1966) found that the administrators in the 1930s had argued that Mchape witch finders were primarily the result of severely depressed economic conditions - as they were held to be young, educated, and urbanised men who were thought to be victims of the slum. The movement was itself presented as one means by which these men, forced to return to their villages or unable to leave them, sought to acquire money and position. The high unemployment levels in the region and other African countries, resulting in an influx of prophets in the country, may suggest that some of these prophets are prophets for economic reasons. As Cheyeka (2004) observes, there has literally been an outbreak of churches in the country with some founders of these churches just trying to derive a livelihood at a time of high unemployment.

Disability in selected Pentecostal churches

Disability in the public space was depicted by the selected Pentecostal churches under consideration to be curable. The imagery was largely associated with the lame, blind, deaf, and large crowds witnessing and experiencing the healing power of God. For example, Bishop John Nundwe is cited to have prayed for a blind woman and her sight was instantly restored by the grace of God (www.mimi.org.zm/ministries), while Prophet anointed Andrew had raised a dead woman to life.

The different pictures of these forms of disability were found in the public advertising space such as billboards, newspapers, television stations and the Internet (social media). Technological advancements such as the Internet, television, radio and billboards had transformed the manner in which Pentecostal churches represented disability.

The televised church services demonstrated the different healing miracles, showing how people with disabilities were healed. While this could be viewed as giving attention to people with disabilities, this kind of representation contributed to seeing disability as that which should be done away with, instead of an inclusive approach to disability. This manner of representation further contributed to the belief that disability, like any form of illness, is the work of the devil, and Christians can be confident that it is God's will to heal. In this regard, a variety of biblical passages to justify this belief in healing are often cited, such as Isaiah 53:5, which is interpreted as prophesying Jesus' atoning death. Through the atonement God in love provided not only for forgiveness from sin, but also for healing from disease, since 'with his stripes we are healed' (Chestnut 1997).

The ministries also reflected disability as a social condition, which needed the support of others for healing. This was shown in the way all those healed claimed to have been brought by other people to the healing sessions. The reasons accounting for this representation ranged from showcasing the power of God to the people, so that more converts could join the particular church where healing of the disabled was taking place. This was reflected in the adverts for the healing sessions: 'if you want to be healed, come to our ministry'. This is as it has been reported in different parts of the globe where healing has been associated with the growth of Pentecostal churches (Espinosa 2004). The healing sessions, which were observed, were associated with large crowds though it cannot be ascertained whether the large crowds translated into stable church membership.

The representation of healed disabilities by the selected Pentecostal churches also indicated the strong belief in healing among Pentecostals. Stolz (2011) notes that divine healing, according to Pentecostals, can heal any illness whatsoever, be it a small ailment (for instance a headache), a mental problem (such as depression), or very serious physical maladies (such as cancer, AIDS, Alzheimer). Whether this healing is real or not, is not for us to judge. While Pentecostal healing is described as being holistic in nature, the observed healing sessions, including the adverts for the healing sessions, emphasised the physical disability overlooking the spiritual disabilities, which are taken care of during their sessions. This suggested the need for conscientisation among Pentecostal prophets and other church leaders on issues of disability.

The represented healing of disability depicted women as the mostly afflicted, crippled and possessed. The age group varied from young women to the elderly, with the majority being around 40 years and above - as heard from the testimonies. The elderly men in the context of healing were portrayed as a chosen generation through which God's works were revealed. In addition, the healing portrayed the dependence syndrome of those who sought help from the prophets, as was affirmed in the title of Papa (father).

Overall, while seeming to be responding to disability, the selected Pentecostal ministries were portraying disability negatively (stigma) as they paraded the disabled for healing in the adverts and sessions. Despite the widespread healing sessions in the city, one wonders why the society still has illnesses and different kinds of disabilities. As Mbewe noted, Zambia's council for the handicapped has revealed that not one actual healing has ever occurred among their members, thereby instructing people to stop going to these deliverance meetings (Live blogging, 18 October 2013).

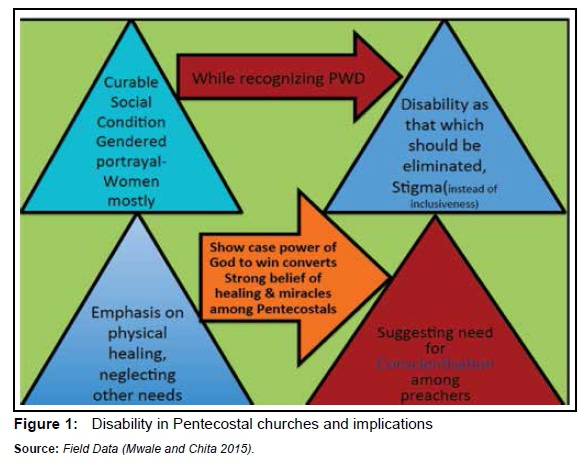

However, if healing is understood to be beyond the physical dimension, to include the spiritual and emotional, perhaps persons with disabilities in these healing sessions receive a different kind of healing beyond the physical healing. This status-quo challenges the current approaches to disability and calls for conscientisation. This interpretation of disability and healing is shaped by the interpretative paradigm. The representation and implications are summarised in figure 1 below:

Methods of disability healing in Pentecostal churches

Nkomazana and Tabalaka (2009) explain the methods that Pentecostals use in healing in Botswana. These methods equally apply to Pentecostals all over the world. They include laying on of hands, anointing with oil, worship, healing at a distance, healing by faith in the word, and through faith in the name of Jesus. The aspect of primal spirituality has a dogmatic formulation in classical Pentecostalism and Ukpong (2008) and Cox (1995) argue that healing is central among Pentecostals. Healing is, therefore, an essential element of the primary piety that Pentecostal worship brings to the surface (Johnston 2008). Ayegboyin (2004) also observes that healing is dominant among Pentecostals and notes that Pentecostals believe that one who is called to begin a ministry will also be equipped to perform signs and wonders, foremost of which is to heal the sick and deliver the oppressed. The themes on healing, deliverance and protection (maintaining deliverance) are stressed at conferences, seminars and conventions. From the studied churches, the most common methods of healing were laying on of hands, anointing with oil, and holy water - usually accompanied with prayer.

Those to be prayed for were required to sow a seed before the cause of the disability was to be made known to them. Usually, and as earlier alluded to, the causes were tied to broken human relations and curses, which needed to be healed. In this case, once the curses have been broken, people with disabilities would be made whole.

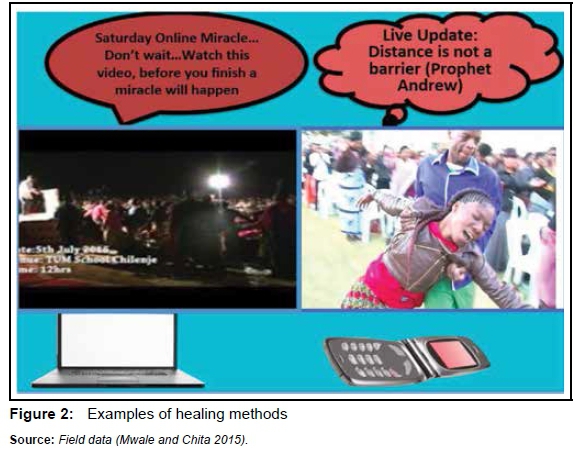

The study established that the methods of healing disabilities had also transformed with technological advancements as people with disabilities were promised healing even via radio, television, the Internet and phone, as shown in figure 2 below. This observation and interpretation of what was happening on the ground is consistent with the interpretive principles, which advance that subjective meanings of the participants of reality are influenced by historical and social contexts (Creswell 2007).

This is in line with Cox's arguments that Pentecostals envision healing to be contagious and in this framework, the Holy Spirit's anointing or oil-like spread of divine power and love is caught rather than taught and that it can be imparted or transferred to others through the laying on of hands, anointing with oil, close physical proximity, objects like cloths, or even through contact with modern communications media such as radio or television.

The technological advancements have transformed methods of depicting and healing disability in Pentecostal churches. Pentecostals have been known to bring technology into the service of healing, aggressively using print, radio, satellite television, cell phones and the Internet, and employing distinctively modern metaphors, such as electrical waves, to explain the invisible power of the Holy Spirit that they feel coursing through their bodies (Deiros and Bottari 1999).

Thus, Pentecostals pray for healing over cell phones, and urge those listening to television, radio or internet broadcasts to place their hands on the transmitting devices and their diseased body parts in order to better receive the tangible anointing into their bodies through the airwaves. For example, Prophet Elijah Chali advised those watching the live healing sessions to touch the screen of the television sets in order to be healed (healing broadcast).

IMPLICATIONS OF DISABILITY REPRESENTATION AND HEALING IN PENTECOSTAL CHURCHES IN A RELIGIOUS PLURALISTIC CONTEXT

Undeniably, the studied Pentecostal churches are addressing the often-neglected mission of the church. While the mainline churches have mostly resorted to helping people with disabilities through the provision of education, health and home care services, the Pentecostal ministries have responded by healing a condition, which is often thought to be incurable. Whether this is true or not, can only be left to the healed to ascertain. The representation of disability healing resulted in people 'shopping' for this cure as they moved from church to church in search of the healing. One person testified: 'I have gone from church to church, hospital to hospital but they have all failed to heal me...today, I have found healing for my legs.'

In the Zambian context this has also led to the growth of more churches, as some of those who are healed have resorted to forming their own churches. For example Cheyeka (2005) notes that some of the founders of these churches claim to have been healed. More so, the resulting 'shopping for healing' was not only 'physical' but also via technological tools, as there were accounts of people switching from one television and radio healing programme to the other. While this has been facilitated by the pluralist nature of the Zambian society, this scenario suggests the need for deconstructing views on disability in both the church and society as a whole.

People with disabilities are also offered an opportunity to participate in the community life differently; in this case religiously, because healing is that which is empowering especially if it is motivated by compassion, justice, and frees those who have been burdened by disease. The representation and healing as demonstrated by the Pentecostal preachers also seemed to make the patients see a meaning in their illness and suffering. This was demonstrated in the testimonies in which the healed began to see the hand of God in their conditions. As indicated by some scholars, meaningless pain is transformed into a manageable burden (Csordas 1988; Geertz 1993) through the healing sessions.

In addition, the patients may be empowered because before the healing they might have felt helpless and lost; and they now see themselves as individuals who can act to transform and overcome their disabilities (McGuire 1987; 1991). Patients may also be integrated into the religious group led by the healer, providing them with new social capital and recognition among others. For example, all those whose disabilities were healed were made to walk on the red carpet during the healing sessions and accorded an opportunity to sit in the so-called very important persons (VIP) section. All of these beneficial effects may furthermore have (though often limited) psychophysical effects, reducing or even eliminating the condition.

Unfortunately the Pentecostal ministries' approach to disability has led to conflicts between biomedicine and divine healing. For example, one of the prophets during a healing session challenged the effectiveness of modern (bio)medicine. Another example is when a family lost a patient and the prophet promised to raise the dead back to life. When this could not materialise, the prophet, family, police and the medical personnel were at loggerheads (Zambian Eye 17 August 2013). The condemnation of biomedicine depicted in the observed healing sessions contributes to the ongoing debate on biomedicine versus divine healing, though there are some schools of thought, which argue that these methods of healing should be complimentary. When closely examined, the emphasis in the healing sessions that modern medicine does not work, leads to misconceptions and implications, but is not limited to the following:

• Biomedicine does not work and that would deter people from seeking medical attention when faced with medical-related conditions, which can easily be cured.

• God's healing powers can only manifest in themselves (men of God). This thinking suggests that they are the only ones who have the power to heal, overlooking the understanding that God can use any person to bring about healing, including medical practioners.

In addition, the failed healing sessions are usually blamed on patients (they have no faith), which is detrimental to the patient. As Cox (1995) argues, the promises that God will heal whenever sickness surfaces, while not reducing the frequency of the need for healing, only encourages already suffering individuals to internalise blame for failures. This also makes the patients to be dependent on the men of God, making them move from one crusade to the other until they receive their healing. This has financial implications, especially in cases where they have to sow a seed for healing and beyond.

It can, therefore, be said that representation of disability and healing in the public space has been influenced by the religious nature of the society. While religion can be liberating and enslaving, the representation of disability and healing has been interpreted to have the potential to enslave those seeking healing from disability due to the prevailing understanding of what causes disability and how it should be addressed or handled.

CONCLUSIONS

The selected Pentecostal ministries represented disability not as a negative condition, but as that which could be healed through the work of the Holy Spirit and in Jesus' name. People's disabilities were attributed to the work of the devil, and as such, they could be healed. All three Pentecostal ministries in the study focused on the lame, crippled, blind, dead, and other conditions, which were described to be tormenting and afflicting the people. These terms of 'tormenting' and 'affliction' in themselves had spiritual connotations and were closely linked to spirit possession and the work of the devil.

The Pentecostal prophets advertised their healing sessions in the public space, and technological advancements had transformed the way this was done. They were largely using different technological tools, especially billboards, the Internet and television. The observed healing sessions, despite using different methods of healing, technological advancements (praying over the television and patients being instructed to touch the screens of their television sets) were reflected in the healing methods other than the use of laying on of hands, holy water, oil and others.

The way the selected Pentecostal ministries in the study represented disability and healing of disabilities, resulted in the 'shopping for healing' as people testified moving from one church to the other and from crusade to crusade in search of healing. While the healing sessions empowered the patients with social capital and recognition, healing sessions also encouraged misconceptions and contributed to the biomedicine and divine healing conflicts.

The paper advances that the religious pluralistic nature of the Zambian society has greatly contributed to the growing demand and popularity of spiritual healing of disability. The paper therefore argues that while all this representation of disability and healing was shaped by the fundamentals of religious pluralism, in which every person can express their beliefs freely, there is a need for awareness of disability issues among the church leaders and communities on the path to inclusiveness (disabilities are not to be used to attract converts to a particular church, as this perpetuates seeing people with disabilities as objects of charity).

The study also demonstrated the need for deconstructing views of disability so that even the healing sessions take into account the special needs of people living with disabilities, and that disability issues in the church need to go beyond healing and miracles, to appreciating the contributions that people with disabilities make to the body of Christ.

REFERENCES

Albrecht, F. 1999. The use of non-Western approaches for special education in the Western world; A cross-cultural approach. In Disability in different cultures: Reflections of local concepts. Edited by B. Holzer, A. Vreede and G. Weigt. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. [ Links ]

Anderson, A. 2002. Pentecostal approaches to faith and healing. International Review of Mission (XCI): 523-34. [ Links ]

Atkinson, D. 1993. The Christian Church and the ministry of healing. Anvil 10(1): 25-42. [ Links ]

Ayegboyin, D. 2004. Dressed in borrowed robes: The experience of new Pentecostal Churches in Nigeria. In Tradition and compromises: Essays on the challenge of Pentecostalism. Edited by K. Joseph and A. Anthony. Ibadan: Michael J Dempsey Centre, 79. [ Links ]

Biri, K. 2012. The silent echoing voice: Aspects of Zimbabwean Pentecostalism and the quest for power, healing and miracles. StudiaHistoriae Ecclesiasticae, Supplement, 38: 37-55. [ Links ]

Burgess, S.M. 2006. Introduction. Encyclopedia of Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity. New York: Routledge, xiii-xiv. [ Links ]

Central Statistical Office. 2010. Census of Population and Housing. Lusaka: Central Statistical Office. [ Links ]

Chestnut, R.A. 1997. Born again in Brazil: The Pentecostal boom and the pathogens of poverty. Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Cheyeka, A. 2004. An outbreak of charismatic churches. Challenge for Christian Living Today 6(2): 14-16. [ Links ]

Cheyeka, A. 2008. Toward a history of the Charismatic churches in post-colonial Zambia. In One Zambia, many histories: Towards a history of post-colonial Zambia. Edited by J. Gewald et al. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [ Links ]

Cheyeka, A.M. 2014. Zambia. World mark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices (volume 4), 556566. [ Links ]

Cheyeka, A.M. 2005. 'Charismatic Churches and their Impact on Mainline Churches in Zambia'. In Journal of Humanities. Vol. 5, 2005, pp. 54-71. [ Links ]

Colson, E. 2006. Tonga religious life in the twentieth century. Lusaka: Bookworld Publishers. [ Links ]

Cox, H. 1995, Fire from heaven. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Creswell, J.W. 2007. Qualitative inquiry and research design. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Csordas, T.J. 1988. Elements of charismatic persuasion and healing. In Medical Anthropology Quarterly 2: 121-142; [ Links ] Geertz, C. 1993. Religion as a cultural system. In The interpretation of cultures. Selected essays. Edited by C. Geertz. London: Fontana Press, 87-125. [ Links ]

Deiros, P. and Bottari, P. 1999. Deliverance from dark strongholds. In Power, holiness, and evangelism: Rediscovering God's purity, power, and passion for the lost. Edited by R. Clark. Shippensburg, Pa.: Destiny Image. [ Links ]

Espinosa, G. 2004. The Pentecostalization of Latin American and US Latino Christianity. Pneuma, 26(2), pp. 262-292. [ Links ]

Film by Anthony Thomas. A Question of Miracles. Documentary, 1999. [ Links ]

Gee, D. 1967. Wind and flame: Incorporating the Pentecostal movement, Assemblies of God. Croydon: Heath Press. [ Links ]

Gosbert T.M Byamungu. 2001. Constructing newer 'Windows' of ecumenism for Africa: A Catholic Perspective. Ecumenical Review 53(3): 341-353. [ Links ]

http://www.mimi.org.zm/ministries.html, accessed on 23 June 2016; Breaking News: Lusaka prophet raises woman from the dead. In Tumfweko 30 June, 2015. [ Links ]

Johnston, S. 2008. Under the radar: Pentecostalism in South Africa and its potential social and economic role. Johannesburg: The Centre for Development and Enterprise. [ Links ]

Kroesbergen, H. 2003. The Prosperity Gospel: A way to reclaim dignity? Word and Context Journal: 78-88. [ Links ]

Landman, C. 2015. Co-authoring enabling environments against social and institutional disablement. A paper presented at the ATISCA/EDAN Joint Conference at Chancellor College, University of Malawi, Zomba, from 20 to 25 July 2015. [ Links ]

Lincoln. Y.S. and Guba, E.G. 2000. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In Handbook of qualitative research. Edited by N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage,163-188. [ Links ]

Live blogging, 18 October, 2013, www.challies.com/liveblogging/strange-fire-conference-preachers-or-witch-doctors. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1970. African religions and philosophy. London: Heinmann [ Links ]

Diop, C.A. 1989. The cultural unity of black Africa: The domains of patriarchy and ofmatriarchy in classical antiquity. London: Karnak House. [ Links ]

McGuire, M.B. 1987. Ritual, symbolism, and healing. Social Compass 34: 365-79; [ Links ] McGuire, M.B. 1991. Ritual healing in suburban America. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Mildnerova, K. 2010. Local conceptualisation of health, illness and body in Lusaka, Zambia. Anthropologia Integra 1(1): 13-23. [ Links ]

Mustwanga, P., Makoni, E., and Chivasa, N. 2015. An analysis of stories of people with disabilities who experienced stigma in Pentecostal denominations in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Economic and Business Review 3(2): 173-81. [ Links ]

Mwale, N and Chita, J. field data, 2015.

N'diaye, M. 2008. Religious pluralism: Possibility and limitations of a dialogue respectful of biblical Christian identity. MA dissertation, South African Theological Seminary, South Africa. [ Links ]

Nash, R.H. Is Jesus the only savior? Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing House, 9. [ Links ]

O'Ranger, T. 1972. Mcape, paper read at the Conference on the History of Central African Religious Systems, University of Zambia (Institute for African Studies)/ University of California Los Angeles, Lusaka. [ Links ]

Oyeri Ogechi, N.O. and Ruto, S.J. 2002. Portrayal of disability through personal names and proverbs in Kenya: Evidence from Ekegusii and Nandi. Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien 3(2): 63-82. [ Links ]

Rapheal, R. 2004. 'Things too wonderful: A disabled reading of Job,' Perspectives in Religious Studies 31/4 (Winter): 399. [ Links ]

Soko, L. 2013. Zambia Dziko la Chonde. Word and Context Journal: 90-99. [ Links ]

Stolz, J. 2011. All things are possible: Towards a sociological explanation of Pentecostal miracles and healings. Sociology Of Religion 72: 456-482. [ Links ]

Tabalaka, A. and Nkomazana, F. 2009. Aspects of healing practices among Pentcostals in Botswana, Part 1. BOLESWA, Journal of Theology, Religion and Philosophy 2(3): 141-46. [ Links ]

The Boisi Center Papers on religion. In The United States on Religious Pluralism in the United States, nd. [ Links ]

The Government of the Republic of Zambia. 2012. Zambia Disability Act. No. 6 of 2012. Lusaka: GRZ. [ Links ]

The World Health Organization. 2011. World Report on Disability. [ Links ]

Udelhoven, B. 2010. The changing face of Christianity in Zambia. Fenza documents. [ Links ]

Ukpong, D.P. 2008. Nigerian Pentecostalism: Case, diagnosis and prescription. OH: Fruities. [ Links ]

Warrington, K. 2006. Healing, gifts of. In Encyclopedia of Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity. Edited by S.M. Burgess. New York: Routledge, 232-36. [ Links ]

Wilson, M. 1957. Health is for people. London: DLT, 117. [ Links ]

Zambian Eye. 17 August 2013. Drama at Choma hospital: Prophet fails to bring back a dead person to life, by Norma Kapata. [ Links ]

Zulu, E. 2013. Fipelwa na ba Yaweh: A critical examination of prosperity theology in the Old Testament from a Zambian perspective. In Word and Context Journal: 27-35. [ Links ]

Interviews

Personal interview, 27 February 2015 in Lusaka.

Personal interview, 28 February 2015 in Lusaka.

Personal interview, 28 February 2015 in Lusaka.