Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versión On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versión impresa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.40 no.1 Pretoria may. 2014

A community's struggle to recapture sacred tradition and reoccupy ancestral land: the case of the Barokologadi

Masilo Molobi

Research Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article discusses the Barokologadi tribe in the Northwest Bushveld who split from the Bapedi Community and sought refuge among Bakgatla Ba Kgafela in 1700. They lived in the Lengwana (Ramatlabama) Village until 1870 when they settled at Mankgopi near Ramotswa in Botswana. On their departure from Mankgopi they settled at Melorane which is now the Madikwe Game Reserve. The Barokologadi tribe, who owned this land, was forcefully removed in 1950. Since they were living outside their historical space, they felt the disjuncture and the lack of space, time and linkage to their ancestral land. After the 1994 democratic election in South Africa they applied for land restitution which was granted to them. They have since started an annual pilgrimage to pacify their ancestors in Melorane. The article has drawn information from oral sources including interviews; literature and the use of own observation on the actual sites and experiences from the people who lived there.

Introduction

The Barokologadi of Melorane settled at first at Melorane in the Northwest Province in the 18th century before the Transvaal Boer Republic imposed its rule over the Western Transvaal in 1936. The community was removed forcefully in 1950 and the land was distributed to white farmers. Those farms were later incorporated into the Bophuthatswana Homeland under the Bantu Authority Act 68 of 1951. Today the ruins of Melorane are situated inside the Madikwe Game Reserve in the Northwest Province.

The community was split into four groups1 and settled in four different villages. One village was incorporated into the area under the Batlokwa chief during the Bophuthatswana governance. This was for administration purposes. Other disparate communities were under the original BaRokologadi new villages. The motive for incorporation had nothing to do with customary law or association of the people but it was how the homelands were clustered and organised during the Bophuthatswana government.

This article is divided and discussed in three parts. The first section deals with the history of Barokologadi until forced removal from Melorane in 1950. Information on the early history of the community came from Breutz (1953) in "The tribes of Rustenburg and Pilansburg districts." The second part discusses the period from 1994 and after they have successfully regained their land. There were a number of legal disputes which emerged concerning the utility of the land acquired. What would it be used for, who would lead the project if any and what would be the future way forward? The third part deals with the underlying arguments and the conclusion.

A brief history of the Barokologadi of Melorane

In addition to the stories collected from the Barokologadi community elders, some written literature was also helpful in confirming the told stories and history of the Barokologadi of Melorane under Kgosi (Chief) Maotwe. For example PL Breutz (1953:22) described the history of the Barokologadi of Maotwe as follows: "The Barokologadi became a section of the Bakgatla tribe in the first half of the 18th century."

In addition Schapera (1965:45) retains that Kgwefane ruled circa AD 1760 to AD 1770 and settled at Saulspoort (Moruleng). During his reign, the Barokologadi (who were at war with the Kgafela since the time of Kgosi Masellane) were finally conquered and inducted into the Kgafela of which they still form a section (though a part left in 1870 and re-settled at Melorane, Zeerust District) (Breutz 1953:252).

In an interview2 with Maeba and Seladi, they stressed that Barokologadi from Mangkgopi settled in Mochudi and the surrounding areas. This happened because they were searching for grazing land for their livestock. I travelled with Mr Ishmael Nkele to the areas of the Barokologadi linked to the Mochudi in Botswana. These people are some of the members of the community of Melorane whom decided to relocate to Botswana willingly after the forced removal. All the communities we visited had a very strong link with the village of Mochudi.3 The Bakgatla of Botswana viewed Mochudi as their capital. The south east of the Mochudi extension is known as "Morokologadi" a name of the community of Melorane that sought asylum there. We were told that Melorane was given to Kgosi Maotwe and declared autonomous after Kgosi Kgafela of the Bakgatla had recognised their sovereignty in early 1800.

Melorane was prominent because of the Hermannsburg Mission Station which was already there in 1863. It was not only a spiritual education centre, but also a hub of circular education. In those days, studying up to standard five was a highly ranked level of education. The highest level of education in Melorane Mission School was standard five and for further education one had to either study in Botswana or at other tertiary institutions in South Africa. Melorane was viewed as the land of milk and honey for those who lived in it. Being forcefully removed from there was unfortunate, according to the progenies, because people were humiliated and disgruntled.

The history of the Barokologadi in Melorane was well summarised by Tsholofelo Zebulon Molwantwa and the Barokologadi Communal Property Association (BCPA) on the Traditional Courts Bill Β1-2012, dated 4 September 2012. Mr Molwantwa summarises it as follows:

I, TZ Molwantwa, was born in 1944 at Melorane near Zeerust. My grandmother, Baitse Ngwatoe (1880-1967) was the first child of Kgosi Thari (1800s-1930s). She would have been the Kgosigadi (Queen) if we had a democratic constitution at the time. I do not want to be a Kgosi but I am telling you this to show that I am rooted in the community.

When I was six years old our community was forcefully moved from Melorane to four different villages of Misgund, Davidskatnagel, Pitsedisulejang and Debrak. I remember some of the events and my family still talk about it. The forced removal process included the impounding of cattle ... I saw this fencing across the village and arrests for trespassing when crossing the fence to fetch water. Government trucks came to load our people and their possessions and relocated them to different places, away from their ancestral land. We started with nothing in the new villages.

At the time of the forced removal of the community in 1950, the community was split into four groups and settled in four villages. There were four other villages4 (apart from those mentioned on footnote 1) with no real connection with the Barokologadi that were incorporated into two tribal authorities under the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951. According to government records this was done for "administrative feasibility purposes.

Short tour in Melorane

Since the focus of this article is on recapturing the tradition and land, 1 decided to take a brief excursion to the Melorane ruins. 1 was accompanied by Mr Nkele, a senior official of the Community Property Association (CPA) which was part of a recommended body to represent the land claim for the community.

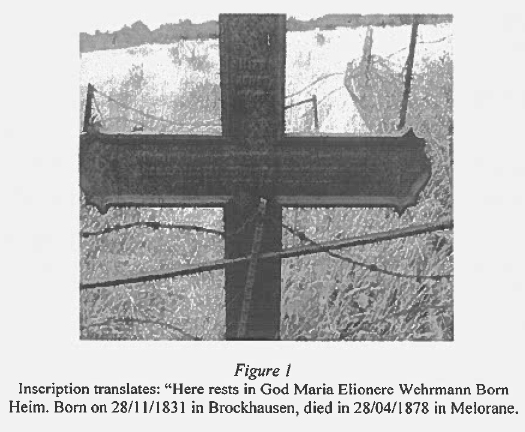

We took pictures while Mr Nkele explained the stories and history in different sections. We visited the grave yard where missionary graves of relatives were situated. On one of the graves, there was information about the missionaries who worked there. The information was clearly engraved on iron crosses.

Maria Elionere Wehrmann was the first wife of Ernst Friedrich Wehrmann and their mission station was based in Kroondal. They arrived in South Africa in 1866.

Apart from the Kgosi priestly status, missionaries were often educators and the introducers of the Gospel. The iron cross symbolised just that. I was told that after the last missionary died in Melorane it became very easy for the people to be forcefully removed in 1950.

There is bit of confusion when explaining the history of the community in Melorane, as they are also linked to their totem, the monkey porcupine. The totem signals the fact that the Kgabo (blue monkey) or Noko (porcupine) that African ancestors are not dead but survive as spirits (Schapera 1934:66). Thus the African moral power which sustains the tribal law is in the hands of the most powerful ancestral spirits, and the spirit of chiefs.

The chiefs in their male descendants form the direct link between the people and the ancestral gods. It is their privilege to worship them whenever occasion demands to honour them at the festival of the first fruits, and offer sacrifices on behalf of their followers so as to appease them whenever they are angered when the tribal laws are breached. Thus every chief is also viewed as a priest to his or her tribe and much of authority is derived from this priestly office. The ruins of Melorane in the Madikwe Game Reserve are still showing clearly where the Lutheran Hermannsburg church was built.

The significance of Melorane to the Barokologadi

At this stage we should take note of the following words by David Suzuki (1999:72) (the ecological scientist on indigenous communities) that indigenous people's very survival has depended on their ecological awareness and adaptation. These communities are the repositories of a vast accumulation of traditional knowledge and experience that links humanity with ancient origins. Their disappearance is also a loss for the larger society, which could learn a great deal from traditional skills which is sustainably managing very complex ecological systems. It is a terrible irony that as formal development reaches more deeply into rainforests, deserts, and other isolated environments; it tends to destroy the only culture that has proven to be able to thrive in these environments.

The interview of Mr Mishack Nkele (2013/06 /27) and many that I have heard before contained facts that stated that:

• Melorane (Rooderand Farm) was our Garden of Eden where we were eating and drinking while living there. There were benefits from natural supplements such as wild fruits, hunting and crop farming.

• There were wild fruits and game all over the area. People were also known for stock farming as well. Interesting was that their livestock was kept at the cattle post which stretched over many kilometres inside the Madikwe Game reserve. They were known as the Sebele and Tshwaane cattle-posts on the banks of the Madikwe River where the Barokologadi kept their livestock. Sebele is a mountain with fountains that kept the area green throughout the year. It is fenced into a huge farm encompassing several square meters.

• People were also able to make artefacts from copper stone in nearby caves, (some families were gifted as regards this skill). There were people who were able to make mortars and pestles to grind sorghum, maize, beans and dry fruits. They were also used to grind some dried medicinal plants and herbs.

• I was also shown where the Hermannsburg Lutheran church was situated. There was a mission school up to grade five. People would go to the South African tertiary institutions and to neighbouring Botswana. There were families who were viewed as being educated as they had completed a diploma course.

• There is a dry Morula tree which dates back to 1950 growing next to the road near the mission station. This tree was where the choirs from surrounding villages gathered to celebrate Christmas and New Year every year. This was not strange as there was a church structure nearby. There is a gravel road that leads to the Botswana Sikwane border post which is about 25 km long.

• Soil like cement was found in the area and it was used to build houses. The types of buildings were made out of stones and cement like soil. You will drive lengthwise for about 10 km across the village of Melorane and the area was about five km wide.

• There is an in-scripted concrete surface from the cement soil that was dugged from there dating back to 1950 when the Barokologadi were forcefully removed from that area.

• Water from the Melorane area was enough to supply in the needs of every household.

From Melorane we went to what used to be their cattle post in Tshwaane, south of Melorane. Tshwaane is a mountain which is not supposed to be climbed during the middle of the day because it is known as the mountain of ancestors. I was told by Mr Rantleru (a local shepherd) that there was a yoke and a pestle and mortar on top of the mountain. We climbed the mountain. When we were almost at the top, our guide refused to proceed, telling us that it was dangerous. According to him that mountain was only climbed by the traditional healers. In the past when seen on top of that mountain, one would be punished because the belief was that ancestors would be angered, resulting in bad consequences.

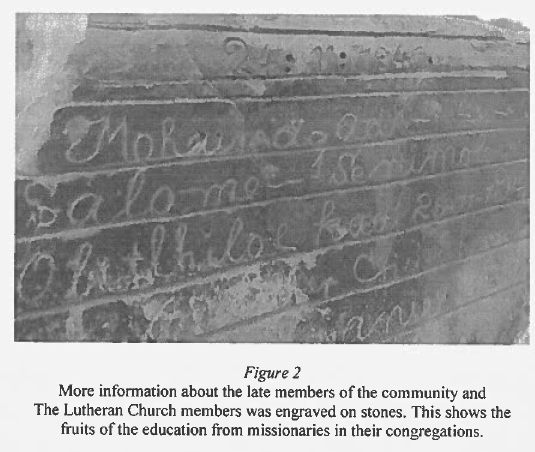

Rev H Dehnke gave some interesting details about the origin of the school in Bethany. In 1870 benches were made at the mission. The Bethany mission made the first attempt to train Batswana teachers, of which the first three were employed in 1874. People then used a small stone slate to write on. Later the only school book became a little Setswana primer of 20 pages. A year later the mission prescribed that school children were to come to school clothed. The student teacher took Bible lessons, catechism, singing, reading, and writing Setswana, arithmetic, geography, Dutch and method. Shortly a number of schools were built on White farms. It is wide spread error that school education could suddenly be developed all over the country in perhaps one modern generation. During the times of missionaries in Melorane education developed until it was taken over by government educational departments (Breutz 1989:77-78).

Ancestral land

We view ancestral land as residential land owned and used by individual families and clans, living in indigenous cultural communities from the very beginning of the time span discussed in this article. Ziegler (1942:10) defines culture as follows:

It is sum of all that is artificial in the life of a group of people. It is their complete outfit of tools and habits invented by man and women and then passed from one generation to other generation. Culture expresses the beliefs, the selective awareness, the aesthetic preferences and the sensibilities of the group. There are elements of social structure such as the system of laws, relationships within family etc. There are sentimental elements such as approval of cleanliness and un-viability of monogamous marriage. There are activity elements such as weaving, farming, dancing etc. There are symbolic elements such as codes, gestures and initiation rites.

Ancestral land is very important, even the Bible portrays such significance when Bethlehem, Capernaum, the town of Jesus, the Jordan River, Mount of Olives, Nazareth and the Christian Quarter among others.5 All of these different cities offered unique points of interest. In similar ways the indigenous and tribal peoples have unique ways of life, and their worldview was based on their close relationship with the land. The lands they traditionally used and occupied were critical to their physical, cultural and spiritual wellbeing. This unique relationship with traditional territory may be expressed in different ways, depending on particular indigenous people involved in specific circumstances; it may include traditional maintenance of sacred or ceremonial sites, settlements or sporadic cultivation, seasonal or nomadic gathering, hunting and fishing, the customary use of natural resources or other elements characterising indigenous or tribal culture.6 Pilgrimage and ancestral veneration are linked to this.

The significance of local indigenous existence and knowledge

It is amazing how much damage can be caused when people are forcefully removed from their place of birth. They lose not just the richness of knowledge of the local people, but more crucially their creative and analytical abilities (Chambers 1997:128). To this Barsch (1999:73) paints the following picture of the significance of indigenous knowledge:

Traditional ecological knowledge of indigenous and tribal people is scientific in that it is empirical, experimental and systematic. However it differs in two ways from Western science: firstly, knowledge is highly localised. It focuses on the complex web of relationships between humans, animals, plants, natural forces, spirits and landforms within a particular locality or territory. Secondly, although reluctant to generalise beyond their own field of observations and experiences, indigenous people can make better predictions about the consequence of physical changes or stresses within a particular ecosystem than scientists who base their focus on generalised models and field observations of relatively short duration, often restricted to the university break season.

In addition local knowledge had important social and legal dimensions. Every ecosystem is conceptualised as a web of social relationship between specific groups of people (family, clan or tribe) and the other species with which they share a particular place. Ecological models often appear in stories of marriages or alliances among species. Hence the structure of an ecosystem is regarded as a negotiated order in which all species are bound together by kinship and solidarity.

Legal outcome of social conception of ecology

Individual human and non-human in the ecosystem for instance, bears a persona; responsibility for understanding and maintaining their relationship. Knowledge of ecosystems is moral and legal knowledge; skilful people are not only expected to teach their ingrained knowledge to others, but also to mediate conflict between humans and other species. Knowledge must be transmitted personally to an individual apprentice who has been properly prepared to accept the burdens and to use the power with humility. Teaching is preceded by the moral development of people's courage, maturity and sincerity (Barsh 1999:74). If people are forcefully removed, a gap will always result and it will impair the correct development of that specific community.

Law of marriage

Another example will be the law of marriage:

Among the Barokologadi culture and tradition are very important. Tswana rules are not written down in book form to be read by everybody. At the same time the laws do not work according to the age of a person. If you are not married you will never know the laws of marriage, even when you can marry at the magistrate's court of law. If you are not counselled by relevant elderly people, you will never know those laws, except the "white" laws which were available to you both. There are laws which govern the situation when a couple enters their new home, and those laws are kept secret. It is not everybody who observes that ritual. There is another law of succession. If you didn't attend an initiation school for men or women, you will never know what is going on there, whether you are an old man or old woman.7

We were told that through the coming of missionaries in South Africa, the role of initiation schools declined very fast among the Barokologadi.

The role of the mission school

According to Breutz (1989:76) the Transvaal Government invited the Hermannsburg Evangelical Lutheran Mission, from northern Germany and from Abyssinia to Natal in 1854. The society began mission work on the western border of Transvaal and first established the stations in Dithejane in Botswana in 1857, Dinokana in 1859, Soshong and Dimao in 1863, and later in the west. The Melorane station was established by Wehrmann in the north eastMarico in 1872.

Emst Friedrich Wehrmann was bom on 23 October 1833 in Lintorf, Osnabruck Land, in Germany and arrived in South Africa in 1866. He died on 31 August 1912 at the mission station in Kroondal, in Rustenburg. Wehrmann was married to Marie Elionere who was born on 28 November 1831 in Brockhausen, and died on 23 April 1878 at the Melorane mission station in the Transvaal. His focus was to teach the local Barokologadi community how to read the Bible and write. In those days education was a great factor for missionaries.

A number of mission stations that were established were an indication of how far the early schools were available to the tribal elite of which several grandfathers of the later chiefs generation learnt to read and write in their own language. The great grandchildren received primary education and in the 1950s the secondary schools in the tribes prepared many for university education, modern leadership and administration. Basic education took three to four generations to develop until parents understood the value of education for the so-called civilised world and labour. The Batswana earlier received school education than other language groups, except the Xhosa in the south (Breutz 1989:77). During the last century people of all ages attended schools, and the missionaries taught the people of all ages together in one classroom.

Literature published by Hermannsburg

The following books were published: Montsamaisa Bosigo by NG Mokone; Bukaya go buisa, a reading book, by Ρ Lesenyane; Mopele and Mogorosi 11 were all published by the Hermannsburg mission in 1863. These books had a great impact on Melorane education. Later they also published series of Matlhasedi I and VI by Ntsime, Roussenn and Mampie.8 Somehow the Hermannsburg mission station was a source of civilisation to the community of Melorane among others. Testimonies and the impact of the educational initiative from the mission station were heard near and far. I have met another elder Setou who was so excited when I visited Melorane for the second time. I asked him how life was while he was still at Melorane. Because he is 90 years old, he was able to relate stories about his friends in the village who were educated in those days. He himself is a retired principal of the village of Kaitnagel where he has been staying since after the removal in 1950.

Annual pilgrimage to pacify their ancestors

The pilgrimage festival is held every year in November to appease their ancestors. Since they are Hermannsburg Lutherans, they will sing some of the most common Lutheran church hymns like Ο nkgoge ka diatla mo tsamaong literally meaning "Carry me by your hands as we move along."

Because of the new era of occupation, people no longer have free movement since the government through Parks Board is a shareholder. An arrangement was made with the Parks Board for the people to visit the area every year in September or October to pacify their ancestors. The difficulty with this arrangement is that people sometimes do need privacy in consulting their ancestors. The Parks Board has rules that seem to protect animals more than the people. Since rhino poaching was recently so rife it has had a negative effect on the people because of more stringent laws that were introduced.

A large section of Melorane forms part of the Madikwe Game Reserve. In fact the village of Melorane is situated inside the Game Park. As a result the challenge in giving land will be geared more to job creation and boosting the economy than anything else. Previously the indigenous economic system had a very low impact on biological diversity because they tended to utilise a great diversity of species, harvesting less of the protected species.

There is an environmental necessity from the sacred sites. In many parts of Africa where there are not many buildings, many protected species survive in sacred areas as they are protected. For instance, people were not allowed to climb Mount Tshwaane during midday or at night as the ancestors will be provoked and may bring danger. We identified different kinds of trees, shrubs and took pictures. On that mountain we identified more than sixty five different species of trees and shrubs. The reasons for this were that people were tribally prohibited, also with mythical repulsive stories, restricted from going to that place. Tshwaane was viewed as a sacred mountain, and only Kgosi and certain senior members of the community could visit and no one else.

The period from 1994 to the present

In the post 1994 constitutional era, part of the original Melorane land was restored to the community, but the settlement agreement by the Land Claims Commission requires that the Madikwe Game Reserve continue to be under co-management. Community members may not return to their ancestral land. The problem was that apartheid and the homelands government incorporated communities under the tribal authorities in terms of the Bantu Authorities Act 68 of 1951.

The imposed system continues under the new Traditional Leadership Governance Framework Act (TLGFA) 41 of 2003 and the Northwest Governance and Leadership Act. The National Commission on Disputes and Claims under the TLGFA and the North West House of Traditional Leaders do not have the statutory powers to resolve the issue. In fact the new laws made the situation worse because they frustrate the rightful claim of the community to govern itself on customary matters in terms of customary law.

The Barokologadi of Melorane fought and won the restitution of their ancestral land concerning the Madikwe Game Reserve and now holds that land under the Barokologadi Communal Property Association (BCPA). The incorporated communities try to use the new laws to stay separate. To date this has been problematic and without success.

The Traditional Leadership and Government Framework Act (TLGFA) 41 of 2003 9 and the Northwest Leadership and Governance Act (NLGA) 2 of 2005 were used to complain to the premier about the apartheid and homeland incorporation of the four groups under different tribal authorities. The answer was that the Traditional Authority cannot be dismantled as new administrative problems would be created then.

The Barokologadi of Melorane community expected more of the new laws under democratic constitution. The wrongs done under the Bantu Authorities Act (BAA) must be undone so that not only the land could be recovered but also the community who lived in that land. Indeed it is impossible to get all the people back into their ancestral land. This could be blamed on the Land Act 27 of 1913 which has disadvantaged so many communities in South Africa.

Influence of the Land Act 27 of 1913

The British and Afrikaner landowners and industrialists set in motion a process that would consolidate their wealth while excluding black people through legislative means.10 The community of Melorane was also affected by the Land Act of 191311 and were forcefully removed from their native land. This had negative consequences for the displaced community of Melorane to date. And the following were the reasons for that:

a) Firstly, it was the idea of an individual to apply for the reclaiming of the land. In this case it was Mr Zebulon Molwantwa, who by virtue of his application, acquired a position of becoming an important community leader and the driver of the process. This was somehow outside the scope of the Kgosi. As a result he was to decide the position of the Kgosi in the process.

b) In that again the Kgosi was now at the mercy of his members. The House of Traditions also finds itself in a very awkward position where the local municipality with its services became a teaser to the livelihood of the king and his people. The local municipality will appoint a mayor who also has power to regulate and control the agenda of the central government.

c) The Parks Board as a main shareholder for the government was always going to be a major decision-maker. Barokologadi could no longer go free in Melorane; they had to go by appointment. Some of the areas they used to move freely in to appease their ancestors could no longer be freely accessed because those areas were regarded as danger zones for the people because of the wild life and rhino poaching. A clear example of this was reflected in several meetings in which the Parks Board did not agree with Barokologadi community on issues of land expansion inside the game reserve and financial agreements were not paid in time or not yet paid to the community transactions.

d) The Department of Water Affairs and Forestry could not be left out. The Molatedi dam is a serious challenge since from the past homelands government of Bophu-thatswana it supplied Botswana with water. In a democratic South Africa, that has not changed and when the Barokologadi claimed back their land, it became difficult to benefit from the arrangements of payments that were done before their claim.

All these listed items above suggest a new social order and context in which the future of traditional communities will be continuously constrained, and the role of the Kgosi and subjects overshadowed. The obvious factors which may hamper the initial intention of reclaiming the dispossessed land may give reason to consider the fact that times are changing and that the future is never the same as in the past. Modern social life settings are political and economic and religious changes are obvious. The new constitution may suggest new and different governing arrangements including democracy. Having said that, what will be the implication in a democratic situation?

Argument contents

The early South African government creation of fixed boarder lines which unfortunately incorporated Melorane has created a permanent problem. People could no longer visit the area as before as it had become someone else's property. The Barokologadi community became defragmented and division into four separate villages estranged them with the Kgosi losing his unitary control on them. A community which was removed from its original place will automatically be disorientated. Posey et al (1998:4) calls this a sacred imbalance.

Turner (2013:514 15) confirms that over time and space the limitations of the ancestry and articulation of tribal collectivism and identity are tremendously affected. Yet those who articulate a more inclusive, residence-focused approach to Barokologadi membership also draw selectively from customary practice. Schapera's (1970:118) classic description of Tswana practice is consistent with numerous Barokologadi informants' depiction of their customs. He writes: "Membership of a tribe ... is defined, not in terms of birth, but of loyalty to the chief."

It is possible for people not to be bom into a tribe but to become subjects of its chief, either by conquest or by placing themselves voluntarily under his rule. Schapera's description of Tswana conceptions of membership emphasises the importance of allegiance. During colonialism, segregation, and apartheid, customary practices were substantially transformed as authority became tied to specific territories rather than to the people (Delius 2008).

Apartheid and Bantustan officials often granted traditional leaders authority over places where most people had no allegiance to these chiefs and little sense of membership in these "traditional communities". This happened in the Barokologadi case (Turner 2013:215). After Kgosi Olefile Maotwe and his followers settled in Pitsedisulejang, the Bophuthatswana government created the Barokologadi Tribal Authority and granted the chief jurisdiction over seven settlements in 1958 (Bophuthatswana Government Gazzette 1993:4). The government's action gave the Kgosi authority over Davidskat-nagel (farm) and Debrak, which had their own leaders, and extended his authority to four settlements that were not previously subject to the Barokologadi.

Kgosi Maotwe has tried to solve these problems since his 2003 appointment. Despite his statement, "You are all Barokologadi", the Kgosi has used place-focused languages electively to welcome those who identified themselves as Barokologadi while refraining from imposing Barokologadi identity on his subjects in Nkaipaa, Ramokgolela, Ramotlhajwe, and Sesobe. In response to requests for self-governance, Kgosi Maotwe has met with leaders in each subject's area, permitted each village to establish separate financial accounts, and advised those seeking independence to file petitions with the Commission on Traditional Leadership Disputes and Claims as he lacks the power to decide this matter.12

Assessment

The discussion reflects tension in the power struggle within the community of Barokologadi, taking advantage of the separate disjointed villages. Some members had allegiance with the Kgosi but were not members of the Barokologadi tribe by birth. This placed the Kgosi in a dilemma. The issues of post 1994 relate to what to do with the land and how to organise the Barokologadi community members into shareholders. The community will never experience their heritage land like in the past. Then what should be done with the new land? The government was clear on the issue that the community of Melorane, though given the land, will never relocate back to it.

The land could only be used in partnership with government departmental structures on equal basis. This meant that the Municipalities, Water Affairs and Forestry Department, Rural Development and Agriculture among others will have more "say" since they are the main source of income for development. Above all, the issue of profit sharing from acquired income for developments in some villages posed a question of representation in important committees supposed to lead the community. It is still a tussle regarding who should be members of the committees, since the educational levels of different villages differ in terms of suitable representatives to committees that will run the project.

Conclusion

We should be very disturbed by the forceful removals which has largely destroyed the Barokologadi identity at the expense of unforgiving segregation laws caused by the Anglo-Boer war. The community of Melorane could have been one of the most interesting in the rural northwest area. The information given regarding culture, tradition and indigenous knowledge suggests a loss and not a complete recovery. The contribution of the mission school in Melorane for instance was outstanding. Mr Setou and Mr Nkele as members of the CPA express their appreciation that missionaries in Melorane have brought in civilisation to Barokologadi, in terms of education.

The role of democracy brought about freedom of land claims, but also has its limitations in terms of freedom of occupation and expression. The fact that it is the government that determine how the people should live in their ancestral land has challenges. The house of traditions faces constant problems in terms of who was the Kgosi and who was not. Many communities in South Africa have suffered from the same problem that cannot be righted with money alone. However this should be a lesson for the future generations. They should be aware that they are not the only people who exist in the land; there are still more generations to come and they will want to know what had happened in the past.

Works consulted

Barsh, RL. 1999. Indigenous knowledge and biodiversity, in Posey, DA. (ed.), Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity (UNEP).Nairobi: Intermediate Technology Publications, 73-76. [ Links ]

Breutz, PL. 1953. The tribes of Rustenburg and Pilanesberg districts. Pretoria: Government Printer. [ Links ]

Breutz, PL. 1989. History of the Botswana and origin of Bophuthatswana: a handbook of survey of the tribes of the Botswana, S. Ndebele, QwaQwa, and Botswana.Margate: Thumbprint. [ Links ]

Chambers, R. 1997. Whose reality counts? Putting the first last.London: Intermediate Technology Publications. [ Links ]

Claasens, A. & Ngubane, S. 2008. Women, land and power: the impact of communal land rights Act, in Claasens, A. & Cousins, B. (eds.), Land, power & custom: Controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act.Cape Town: University of Cape Town and Legal Resource Centre, 154-183. [ Links ]

Claasens, A. 2011. Resurgence of triballevies: double taxation of rural poor. South Africa crime quarterly,11-16. [ Links ]

Delius, P. 2008. Contested terrain: land rights and chiefly power in historical perspective, in Claassens, A. & Cousins, B. (eds.), Land, power and custom: controversies generated by South Africa's Communal Land Rights Act.Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press and Legal Resources Centre, 211-237. [ Links ]

Posey, DA. 1999. Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity(UNEP). Nairobi: Intermediate Technology Publications. [ Links ]

Schapera, I. 1965. Praise-poems ofTswana chiefs.Oxford: Clarendon Press. [ Links ]

Schapera, I. 1970. A handbook ofTswana law and custom,London, F. Cass. [ Links ]

Schapera, I. 1934. Western civilisation and the natives in South Africa. London, [ Links ]

Suzuki, D. 1999. Linguistic diversity, in Posey, DA. (ed.), Cultural and spiritual values of biodiversity (UNEP).Nairobi: Intermediate Technology Publications, 50. [ Links ]

Turner, RL. 2013. Continuing divisions: traditional land restitution and Barokologadi communal identity. Available at The Journal of Modern African Studies50(3), August, 507-531. [ Links ]

Ziegler, JH. 1942. A social-psychological study of changing rural culture. Washington: Catholic University Press. [ Links ]

Internet source

Molwantwa, TZ. & Mogale, C. 2010. Barokologadi Communal Property Association and Land Access Movement of South Africa. "Submission to the Portfolio Committee on Rural Development and Land Reform for the Public Hearing on the Black Authorities Act Repeal Bill." Available: http://www.pmg.org.za/files/docs/amosa.pdf. Accessed: 18 July 2010. [ Links ]

Interviews

Mishack Nkele, 12 March 2010. Chairperson of Barokologadi Communal Property Association (CPA) in Debrak. [ Links ]

Mr Maeba Mochudi, 31 May 2010. He was a resident of Melorane until forced removal in 1950, but moved to Botswana. [ Links ]

Tsholofelo Zebulon Molwantwa, 27 August 2010. Barokologadi Communal Property Association Chair, in Krugersdorp, and Melorane. [ Links ]

Elder Lephogole, 20 July 2012. He was a resident of Melorane until forced removal in 1950, but now stays in Botswana. [ Links ]

Mogatusi, Mochudi, 21 July 2012. He had a close relationship with members of the Melorane Community. He informed us about the relationship of the Morokologadi section in Mochudi and Melorane. [ Links ]

Mr Seladi, 15 August 2012. Community informant, Malolwane. He was a resident of Melorane until forced removal in 1950, but moved to Botswana. [ Links ]

Ishmael Nkele. Field work guide to Barokologadi Communities in Botswana, between 2009-2013. He stays in Debrak. [ Links ]

Elder Setou from Kartnagel. He was a resident of Melorane until forced removal in 1950. He studied at the Melorane Mission School. [ Links ]

Archival material

Bophuthatswana, Government Gazette of2/04/1993, Vol. 22, no. 59. [ Links ]

1 Pitsedisulejang, Debrak, Kartnagel and Obakeng were later placed under the formal jurisdiction of the Batlokwa Tribal Authority.

2 Interview was conducted on 31 May 2010 in Mochudi and Malelwane in Botswana respectively.

3 Some villages in Botswana include Mabalane, Sikwane, Mmathibudikwane, Ramonaka, Malolwane, Dikwididing, Modipane, Odi, Bokaa, Pilane, Phaphane, Morokologadi, Mochudi, and Tlokweng up to Gaborone and share a common culture and traditional experiences.

4 Villages of Nkaipaa, Ramokgolcla, Ramotlhajwe, and Sesobe.

5 http://www.tourstotheholyland.com.

6 www.oas.org/en/iachr/indigenous/docs/pdf/AncestrlLands.pdf.

7 With reference to Kgomotso Mogapi's "Selso le ngwao. http://tlhalefang.com/setswana/setso.html.

8 Kgomotso Mogapi {2009) http://tlhalefang.com/setswana/setso.html.

9 More information about TLGFA is on http://www.customcontested.co.za/laws-and-policies/traditional-leadership-and-govemance-framework-act-tlgfa/.

10 http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/natives-land-act-1913.

11 By the time the Land Act of 1913 was enacted, South Africa was already moving in the direction of spatial segregation through land dispossession. One of the key legislations that laid down the foundation for a spatially divided South Africa was the Glen Grey Act passed in 1894. After the end of the South African War, the British and Afrikaners began working on establishing the Union of South Africa, which was accomplished in 1910. However, black people were excluded from meaningful political participation in its formation and future.

12 Separate accounts provide the settlements with greater autonomy while they await action from the Commission. Several informants asserted that their villages had not benefited from the tribal levies they were forced to pay during apartheid. Although the North West Provincial Parliament passed legislation in 2005 that forbade traditional councils from imposing levies without first obtaining the consent of community members at the kgotla or by canvassing all members, Claassens (2011) argues that there's been a recent "resurgence" of levies across the former homelands.