Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versão On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versão impressa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.39 supl.1 Pretoria Ago. 2013

Agonies of structural and leadership formation in responding to HIV and AIDS between 1990 and 2000: A historiorganisational perspective

Stephen Muoki Joshua1

Pwani University, Kilifi, Kenya

ABSTRACT

In 1990, the Southern Africa Catholic Bishops' Conference (SACBC) resolved to respond urgently to the contextual crisis brought about by HIV and AIDS. It envisioned a new structure and leadership that would spearhead this response. However, the bishops did not foresee that this process would be marred by condom controversies, protracted labour court cases and financial donor withdrawals. In this article, I unravel a deluge of archival materials from SACBC's archive located at its headquarters in Khanya House, Pretoria, South Africa, as well as a number of oral interviews from relevant Catholic clerics and practitioners. I argue that, whereas causes for the delay in the process of establishing a structure and leadership were multifaceted, the persistent determination of the hierarchy to protect a traditionally held sexual ethos of the Catholic organisation in the midst of a fast-changing context on account of HIV and AIDS was a key factor. The power interplay thereof and the suppression of dissenting voices are not unique to the SACBC as a formal religious organisation.

Introduction

The factors that caused a paradigm shift and a sense of urgency in the Catholic Church's response to HIV and AIDS in Southern Africa in the early 1990s were many and varied. Firstly, the demise of apartheid, which was partly a victory for the church following its many years of involvement in the struggle for justice and freedom, had major implications for the church's response to HIV and AIDS. The first signs of democracy in February 1990 -with, among other things, the release of Nelson Mandela, the lifting of the ban against major political parties such as the ANC, and the apartheid government's invitation to all political parties to came to the negotiating table - as well as the birth of a democratic state in 1994 - called for a major organisational transition on the part of the Catholic Church in South Africa. Indeed, the "Catholic Indaba"2 - a historic gathering of 120 bishops and religious superiors held between 9 and 13 July 1990 at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg3 - was dedicated to "re-envisioning the role of the Catholic Church in the New South Africa".4 It was the first time in the history of the Catholic Church in Africa, arguably in the rest of the church, that such a meeting had been held. It brought together male and female church leaders from South Africa, Namibia, Swaziland and Botswana with the sole purpose of "finding a new role in the new situation and reorganising herself [Catholic Church]".5 One participant summarised it well: "The church is agonising about her role in a new South Africa".6 According to Father Paul Decock, who attended the conference as a representative of the Theological Advisory Commission, there was a lengthy deliberation on the church's response to AIDS as one of the major social ills facing the Southern Africa region.7 The demise of apartheid therefore not only created room for the church to focus on other previously neglected issues in the society - HIV and AIDS being top on that list - but also became a strong vindication and motivation for the Catholic Church's involvement in alleviating social ills, given its role in the fight against institutional apartheid and oppression. This partly explains why HIV and AIDS suddenly became the church's top priority in the early 1990s.

Secondly, in 1990, the rates of both HIV infections and of AIDS mortality were increasing - despite the media's efforts to raise HIV and AIDS awareness. This, inevitably, gave rise to renewed urgency and focus in the church's response to the pandemic. The onset of the 1990s came with an unexpected dynamism in the spread of HIV. Not many in South Africa had foreseen that AIDS would become predominant among heterosexuals, the black population, "innocent" children, prisoners, household wives, haemophiliacs and the youth. The cruelty of the virus in infecting professionals such as judges, healthcare professionals, teachers and even priests, as opposed to its 1980s association with the "immoral groupings" such as prostitutes, homosexuals and drug abusers, not only came as a shock to the greater population but more so as a challenge for the church's preconceived notions about AIDS. Father George Vitello, a prominent

Catholic speaker who was at that time based at the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, spoke of this shocking realisation at a workshop held in South Africa. The Southern Cross of 8 April 1990 reported as follows:

Promiscuity alone could not be blamed for the spread of the [AIDS] disease. For instance, nine percent of AIDS sufferers were under five. No one was immune. He added: "Worst of all, it is a disease which affects not only individuals but the whole family. About 1.5 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are infected with AIDS. Apart from the 250 000 children who will die of the disease in the region, another 750 000 will be orphaned as a result of AIDS". The disease initially affected only homosexuals but the number of heterosexuals with it was increasing - as was the number of women. Father George Vitello said the church had a vital role to play in the struggle against AIDS. The needs of AIDS sufferers had to be recognized.8

The year 1990 thus became a watershed as far as the response of the Southern Africa Catholic Bishops' Conference (SACBC) on the issue of HIV and AIDS was concerned.9 AIDS became too obvious for the church to ignore. Indeed, it was in the 1990s that AIDS became increasingly visible to the general population as a disease. The 1990s were, therefore, characterised by the vivid realities of an AIDS epidemic - an increase in the number of AIDS orphans, an overwhelming number of sick people in hospitals and homes, and many burial services. Contrary to the 1980s where AIDS was more or less mystified, AIDS became much more tangible in the 1990s. The urgent need for the church to re-examine and respond to the AIDS disease in the early 1990s was heightened by the increasingly overwhelming presence of AIDS in the church's spheres of operation.

Thirdly, political changes in the country during the early 1990s opened up South Africa to the rest of the continent and to the world at large. This meant easy dialogue and exchange with other parts of the continent. Although the same factor has been used by some to argue for the increase in HIV transmission in the early 1990s,10 I find that the SACBC took advantage of the opportunity to explore parallel responses to HIV and AIDS in other parts of the globe. For instance, in 1992 and 1994, the Catholic Church in South Africa sent delegations to East Africa, where the AIDS epidemic had advanced to catastrophic stages.11 Another delegation comprising two SACBC bishops was sent to the USA in 1999.12 The aim of the missions was to learn how their counterparts in these regions had responded to the disease and, thereafter, do the same in South Africa.13 The example of Catholics in other parts of the world, most specifically Uganda and the USA, became a wake-up call for the South African Catholic Church in responding to AIDS in the early 1990s.

The Southern African Catholic Church's urgency to respond to AIDS in the early 1990s was also born out of its new impetus to become a "community serving humanity". In May 1989, the SACBC launched its ambitious pastoral plan, "to become a community serving humanity", in which it endeavoured to become relevant to the plight of South Africa and become a more inclusive church. This comprised an educational programme that was intended to follow the teachings of Vatican II and to respond to the contextual needs of the South African society. Hence at the beginning of the 1990s there was a conscious and internal effort by the Catholic Church in Southern Africa to reform. HIV and AIDS therefore became the "litmus test" for the programme. How could the church become a "community serving humanity" while ignoring an epidemic of catastrophic proportions?

Although the church's hierarchy had by 1991 resolved to respond to HIV and AIDS, it neither had a clearly outlined plan of action nor a working policy on HIV and AIDS.14 Besides, there were no leadership structures through which to address the epidemic. In this article, I will argue that the entire period between 1990 and 2000 was characterised by random and experimental initiatives in forming leadership and structures that would spearhead the response to HIV and AIDS. Whereas many lessons were ultimately learnt, with minimum progress nevertheless, I shall demonstrate that leadership in the SACBC's response to HIV and AIDS struggled to find its feet in the entire 1990s. During this period, the SACBC's response to AIDS staggered with minimal financial resources, untrained staff and a general lack of purpose and direction.15 The hierarchy had too much to protect, especially when it came to HIV prevention methods and did not relent in using its power to punish dissenting voices, a key characteristic of formal organisations.

The SACBC's structural response to HIV and AIDS

No sooner had the church resolved in 1990 to become actively involved in responding to HIV and AIDS, than it realised the acute lack of reliable leadership structures, trained personnel and a budget to facilitate AIDS work. Shortly before they released the Pastoral Letter on AIDS in January 1990, the bishops unanimously agreed that "there was a grave duty on the part of organisations and individuals to prevent HIV spread".16 The bishops observed further that "this will require not only money, but even more importantly suitably trained and compassionate personnel".17 The church therefore immediately embarked on forming a structural response to HIV and AIDS as a matter of urgency and continued to do so until 1999. The AIDS leadership structure that was formed by the conference took the forms of two bodies, namely the SACBC AIDS Office and the diocesan AIDS committees.

The SACBC AIDS Office

Prior to 1990, AIDS was administratively a "minor issue" in the SACBC leadership structures. It was seen as a health issue and simply one among many other diseases that the Catholic Health Care Association (CATHCA) addressed and reported on to the Conference. However, between 14 and 16 March 1990, two months after the bishops' release of the Pastoral Letter on AIDS, Cecilia Moloantoa, the secretary of the Health Care and Education Department of the SACBC, organised a national Catholic HIV and AIDS consultative conference.18 The consortium, which had been called upon by the bishops,19 was meant to "discuss the pandemic and to advise the SACBC on the course of action to be taken by the church".20 It constituted representatives from 20 dioceses with a mandate to establish the Catholic AIDS Network (CAN), steered by the interdiocesan AIDS committee.21 It recommended the following:22

- the establishment of a centre for inter-regional coordination of resources, efforts and services for the 30 dioceses;

- the prevention of the spread of HIV/AIDS infection through educational programmes conducted in conjunction with organisations, solidarities, and other commissions within the Catholic Church and in the broader communities;

- the development of educational programmes for target audiences particularly in schools and among youths groups;

- the development of comprehensive, relevant and culture-sensitive educational materials for dissemination through appropriate communication channels;

- the development of programmes for the training of trainers, that is, youth groups, leaders, priests, teachers, and so on, who will operate within specific groups, church organisations and communities;

- the setting up of CAN structures and resources for HIV prevention through education and caring and support systems for HIV-infected people and their families; and

- the development of care programmes for people with AIDS and their families.

It was also agreed that the committee should be elected annually by the annual interdiocesan conference on AIDS. Doctor D Sifris, an HIV and AIDS consultant in a private clinic in Johannesburg who was both HIV positive and gay,23 was also appointed as a committee member.24 The Associate General Secretary of the SACBC, Father Emil Blaser, was appointed as the chair of the committee. Cecilia Moloantoa was appointed as director of the CAN which was to be steered by the 12 member committee. According to a summary report that was tabled before the conference in January 1991 plenary session, the emphasis was on three areas, namely education, care and counselling.25

The interdiocesan AIDS committee met on June 1991 and received reports of the diocesan AIDS activities. It was this meeting that suggested the appointment of an AIDS coordinator and an administrative secretary as a matter of urgency. The committee heard that the Catholic Association for Overseas Development (CAFOD), a British Catholic donor agency, had invited funding proposals from the AIDS programme with a running budget comprising salaries, a vehicle and its maintenance costs.26 The National Department of Health and Population Development had also agreed to give a grant of R100 000 to the SACBC in order to facilitate a response to HIV and AIDS. Since "AIDS is so much more a social/pastoral issue that broadly links with all the SACBC departments and personnel", the committee recommended that "the AIDS Coordinator should not be specifically linked to any one department within SACBC but should liaise with all departments".27 These recommendations were presented, discussed and passed by the conference. As a result, Chrys Matubatuba was hired as the first Interdiocesan AIDS Coordinator in September 1992. His task was, among other things, to assist the dioceses in setting up and developing their diocesan HIV/AIDS programmes and to facilitate networking and training for Catholic HIV/AIDS field workers. He was expected to become a resource person to the conference on matters of HIV and AIDS, to produce AIDS educational materials and to represent the conference in relevant meetings and gatherings. During the first four months following his appointment, Matubatuba attended an HIV and AIDS training programme with the South African Institute for Medical Research (SAIMR) under the tutorship of a Dominican sister, Alison Munro.

Matubatuba had served as the SACBC AIDS coordinator for nearly three years when he was dismissed on 9 May 1995. According to his reports to the SACBC and to the chief financial donor (CAFOD),28 he had managed to organise two annual interdiocesan AIDS conferences, on 16-18 July 1993 and 22-25 July 1994. He had attended exposure tours in East Africa (Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania) and the USA. He had organised and facilitated educational workshops in dioceses such as Pretoria, Durban, Bethlehem and Kroonstad.29 He had organised awareness materials such as T-shirts, a pamphlet and posters. He had taken his awareness campaigns to schools, parishes, conferences and tertiary institutions. He had also facilitated a "train the educator" workshop in the diocese of Umtata. Although his efforts had been rather thinly spread across many awareness activities, his success had been contingent upon the structures and objectives laid down for him. Apparently, his main contribution had been that of sensitising the dioceses towards a response and the creation of awareness.

Matubatuba's efforts during his term of office did not impress the conference; hence his dismissal long before the expiration of his contract. The circumstances following his dismissal, which were pertinent to this research, attracted wide media coverage and put the Catholic AIDS response, the SACBC's specifically, in the public spotlight. Among the many complaints put forward against Chrys Matubatuba was the issue of administrative incompetence. The auxiliary bishop of Cape Town who was a member of the interdiocesan AIDS committee, Bishop Reginald Cawcutt, put his official complaint in writing: "My complaint about Chrys is his inefficiency which has resulted in an amazing waste of time and money in the establishment of our AIDS department".30 This statement was in response to a letter by Father Emil Blaser, the Assistant General Secretary, requesting bishops' guidelines on the AIDS coordinator.31 The statement concluded that "Chrys is just not able to cope with the task given him". Bishop Cawcutt demanded that the AIDS Coordinator be replaced. However, the minutes of the plenary session immediately preceding this statement, the internal correspondence letters, as well as Matubatuba's own report to the conference on January 1995, not withstanding the numerous media reports following his dismissal, are indicative that a lot more was at stake.

It all began at the January 1995 SACBC plenary session. Some bishops had overheard that the AIDS Coordinator was distributing condoms and that he not only encouraged the use of condoms but also "demonstrated their use in one of the workshops using a plastic made penis".32 During a discussion that ensued after his report to the conference, Matubatuba denied the allegations but conceded that he had once demonstrated the use of condoms.33 He indicated that there was no clear guideline on this matter and that he had repeatedly asked for a policy on the matter. The bishops concluded that "he lacked judgement" and that "his employment with the conference should be terminated at the earliest opportunity with due regard to labour regulations".34 The secretary general found this to be a "difficult decision to implement because no disciplinary action or warning had been taken" on this matter.35 Although the bishops' statement on the dismissal had no mention of condoms and the conference minutes remained silent on the cause for the dismissal,36 it was clear to both the Star newspaper and Matubatuba himself37 that he lost his job somewhat unfairly and on account of his use of condoms in HIV prevention, which was viewed by the hierarchy as unconventional.38 According to Emil Blaser39 and the Star40 newspaper, Matubatuba took the battle to the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) charging the conference with unfair labour practice in his dismissal.41 Because his lawyer had failed to show up in subsequent court hearing sessions, the case was dismissed.

In any case, the events leading to and emanating from the dismissal of Matubatuba dealt a major blow to the establishment of AIDS leadership structure in the church.42 Joe Masombuka, a member of the Catholic Church who had gone public on his HIV positive status, volunteered to coordinate the AIDS work before a new coordinator could be hired. However, the absence of a hired coordinator was also an opportunity for the conference to evaluate its performance on HIV and AIDS matters. The creation of the Catholic AIDS Network (CAN) committee was "one of the pre-emptive steps taken by the Catholic community in South Africa towards combatting the many problems associated with AIDS".43 The SACBC AIDS Awareness Programme had facilitated a network in matters relating to HIV and AIDS between the 17 dioceses actively involved in responding to the epidemic. However, it had not made any significant impact on KwaZulu-Natal dioceses. As compared to the 1991 report where Durban was the only diocese in KwaZulu-Natal with an AIDS programme, the 1994 report indicated that three dioceses from KwaZulu-Natal had an AIDS programme. The 1991 report described the Durban Home-Based Care Programme as being "slow in getting off the ground"44, whereas the 1994 report included Durban, Eshowe and Mariannhill in its list of dioceses involved in the AIDS response.45 A total of 14 dioceses in the SACBC region,46 including Kokstad, Dundee and Umzimkulu of KwaZulu-Natal did not have any AIDS programmes. There is no evidence that directly links the initiation of AIDS response in the three dioceses (Durban, Eshowe and Mariannhill) to the work of the interdiocesan programme. The most that can be said is that the programme had only discovered what was already happening in the dioceses. It is no surprise that in 1996, Dr Linda Maepa, the successor of Matubatuba, would observe the following after a thorough situational analysis:

The AIDS office of the SACBC has had a rather chequered history right from its establishment in 1992. The activities carried out by the office seem to have depended on the interest of whoever was at the helm. While in annual reports there is mention of projects and activities such as training workshops, there is no documentation that shows clearly the specific objectives of these, and the procedures for evaluating their impact. There is very little evidence on the ground of the work of the SACBC AIDS office.47

Therefore, prior to 1995, the SACBC AIDS Awareness Programme, had concentrated on incoherent awareness activities with little to show-off in terms of co-ordination, funding and capacity building. Hence one may assume as does Maepa, that it is the realisation of this situation - that CAN was not achieving the intended objectives - and the need to give the office some direction that the interdiocesan conference formally established the Southern African AIDS Programme (SACAP) in 1995.48 SACAP went ahead appointing a new committee of which Liz Towell of Sinosizo, Durban became the executive chairperson.49 Following these changes and the abeyance of the SACBC AIDS Awareness Programme for approximately a year (February 1995 - June 1996),50 a new coordinator was appointed in June 1996.51

Maepa's first task was to gather information.52 She was also asked "to analyse the situation and suggest the way forward in the Catholic Church's response to the AIDS situation".53 Maepa indicated to me in an interview that she understood very well what was expected of her and that she worked hard to achieve the SACAP objectives within her job description.54 The first item in her job description was "to study and propagate the teaching of the church with regard to issues related to HIV/AIDS and to seek clarification from the Catholic moral theologians, where needed".55 A more detailed responsibility of the co-ordinator was "to initiate education and training programmes within the local churches and the general community on HIV and AIDS, home-based care and other related issues and empowerment skills training to ensure that they are equipped to educate others".56 This was in line with the SACAP objective "to provide training, resources, information and direction to diocesan AIDS departments and workers functioning in the area of the SACBC".57 The proposal to CAFOD for funding of 27 September 1995 put it even more pragmatically as "to have home care teams in the 30 dioceses".58 The emphasis of the SACBC leadership had shifted from AIDS awareness to care and training.

Maepa was well equal to the task relating to her training and experience. As an educationist with long years of service at the University of Swaziland, she visited various dioceses and parishes and on the basis of "very few responses from the chanceries" went ahead preparing a situational analysis.59 She recommended that the Catholic response to HIV and AIDS should not primarily focus on establishing institutions of care, but rather venture into educating the population on primary health care regarding risky sexual behaviours. She later learnt that this had not been well received by most of the bishops who were interested in visible institutional responses such as hospices and orphanages. She told me that she had faced a lot of opposition from the chanceries. According to her, most chanceries were not supportive and very few showed any interest in responding to the epidemic. A major shift in the CAFOD leadership in 1997 exacerbated the situation when the new leadership insisted on revising the financial budget. CAFOD withdrew its financial support in the area of salaries and administrative costs. This unforeseen move by CAFOD meant that there was no salary for Maepa and other junior staff in the SACBC AIDS Office. The financial crisis that emanated from this situation created certain tension in the administration and operation of the AIDS ministry. Certain leaders, such as Bishop Cawcutt, insisted that the office had to operate under the health department of the SACBC. Father Emil Blaser, however, felt that alternative funding should be sought. These factors made Maepa's work difficult.

However, it was the condom controversy that exacerbated the working relations leading to Maepa's immediate dismissal. According to her, she had "asked the bishops difficult questions regarding condoms" during one of her reporting sessions.60 She had demanded a Catholic policy on the use of condoms. She had added her voice to that of Chrys Matubatuba,61 her predecessor, and that of Cecilia Moloantoa,62 a coordinator of the SACBC's Department of Health and Education, on this extremely controversial issue by way of highlighting certain pragmatic concerns.63 During his defence on 17 January 1995 before the Bishops' Conference, over an alleged "lack of judgement" in the handling of the condom issue, Matubatuba had lamented that, while the bishops' Pastoral Letter on AIDS was admirable, he had often requested a ruling by the conference on the use of condoms and this had never been forthcoming.64 Indeed, Matubatuba's 1993 annual report had highlighted the use of condoms as one of the greatest obstacles to the programme. He reported to the bishops as follows:

The lack of our church's policy on condom use is another obstacle. The Catholic Church is well known to be the strongest and consistent opponent of the condoms as a contraceptive. However, there is seemingly no clear stand on condoms with regard to the prevention of infection. There seems to be some difference of opinions even from highly placed authorities of the church. The subjectivity in dealing with the issue places one who is supposed to implement the programme in dilemma especially when faced with a question on the stand of the church.65

On 18 January 1994, Cecilia Moloantoa told the bishops that "certain health issues such as the legislation on abortion and the HIV/AIDS epidemic were challenging the teaching of the church on moral values".66 Maepa was aware of this history67 when she exclaimed: "All I am requesting here is that the bishops issue a pastoral letter on condoms that takes into account the various dimensions of contemporary Southern African life".68 Arguing that people were confused, especially Catholics and not the least their priests, Maepa pressed the issue further saying, "Here is a situation where one particular mode of contraception has assumed a universal and larger than life significance, not as a contraceptive, but a life saver".69 According to Maepa, many bishops told her after the meeting that they admired her courage and that they were simply too shy to deal with the issue.

Maepa was aware of the bishops' reluctance in addressing the condom issue. She did not, however, foresee that her persistence in requesting a "statement on condoms" could, as in the case of her predecessor, cause her to lose her job. Her contract was suddenly terminated in 1997, only a few months after her insistence on a statement on the use of condoms. The "AIDS desk", as it was popularly known by then, officially closed down. This came as a big surprise to both Maepa70 and the only financial sponsor, CAFOD.71 The January 2008 SACBC plenary minutes did not fail to capture this second demise of the AIDS Office:

The AIDS Office had been closed and the co-ordinator had received a retrenchment package. However, the Administrative Board had dealt with correspondence received from the funders, CAFOD, as well as the coordinator who were dissatisfied with the decisions taken.72

As indicated above, the termination of Maepa's contract was partly for financial reasons. Although, CAFOD had just sent R49 000 in support of the programme,73 the executive committee had felt that this money was not enough, in view of the fact that the South African government had turned down its application for funding of January 1996.74 CAFOD was willing to extend its financial support for the programme except in the area of administrative costs.75 However, there is no indication in the minutes of the executive meetings that the National AIDS Programme had such a serious financial crisis to necessitate a closure of the programme. On the contrary, there was a balance of R68 000 by August 1998, following the closure of the office and the subsequent payment of all outstanding bills.76 It is clear from CAFOD's correspondence with the Conference that, even though CAFOD was not happy with the bishop's decision to lay off Maepa, it hoped that the two parties would resolve their differences amicably without its intervention. On 8 April 1998, CAFOD wrote as follows:

Greetings from London! Please find enclosed a copy of a fax sent today to Father Buti Tlhagale which we hope explains CAFOD's position with regard to the current situation between the SACBC and Linda Maepa. Although CAFOD is the major funding source for the National AIDS Programme, we feel that the conciliation process is a private matter between the two parties.77

During an earlier visit by CAFOD executives, it was made clear that CAFOD had "no fixed viewpoint on what the programme should look like".78 The breakdown of relations between the two parties had something to do with the manner in which Maepa had conducted the AIDS programme. According to Maepa, both CAFOD and the SACBC secretariat were happy with her work in the office. The fact that her employment had been terminated a few months after she had tabled her report in which she strongly demanded a statement on condoms suggests that her position on condoms had something to do with the bishops' decision. On 12 August 1998, the bishops were relieved to hear that "nothing further has been heard of the claim of unfair dismissal of Linda Maepa".79 Apparently, this was short-lived because, according to Maepa, she took her grievances to the CCMA and won the protracted legal case of unfair labour practice. Five years later, she was fully compensated.

The relationship between the bishops' conference and CAFOD, especially with regard to funding and the running of the AIDS Office, staggered on through 1998 and ultimately collapsed in 1999. In August 1998, the bishops were told that "CAFOD was concerned about a perceived lack of commitment for AIDS".80 CAFOD was even hesitant to allow a transfer of the R68 000 budgetary balance to CATHCA, the organisation that had taken up the conference's matters relating to AIDS.81 The "push and shelve" continued as bishops' efforts to hire a new coordinator were adamantly opposed by CAFOD. Instead, CAFOD demanded an AIDS workshop with the bishops during their January 1999 plenary session. CAFOD complicated the matter further by pegging their support on this request. The bishops were told that the "funding for CAFOD [seemed] contingent upon compliance with this request".82 A turn of events is indicated in the report of 11 August 1999 that "things changed [for the worse] after contradictory messages had been received from CAFOD about the availability of funds".83 The bishops' response was not unexpected: "The bishops discussed the difficulties experienced with CAFOD and it was agreed that CAFOD should be kept informed about developments".84 The bishops had again underestimated the effects of a hurried termination of the coordinator's contract. They found themselves starting all over again with neither a running office nor a willing financial sponsor.

Maepa's two years at the SACBC "AIDS desk" were not entirely fruitless. Her term of office differed from that of Matubatuba in that it did not fall under the SACBC's Department of Health and Education, but was rather an independent establishment belonging to the SACBC. It was not a department of the SACBC either since the coordinator did not report to the Secretary General as was the case with the other SACBC departments. The Southern Africa AIDS Programme's (SACAP) executive committee was responsible for the AIDS programme during that period. SACAP in turn was owned by the SACBC.85 SACAP did not survive for long; it collapsed with the closure of the AIDS programme in 1997. However, Maepa had managed to tour the various dioceses and compile a database of all HIV and AIDS projects in the region. The database, comprising 30 active dioceses, was a build-up of Matubatuba's 17 diocese databases. Six out of the seven dioceses in KwaZulu-Natal, which constitute the special focus area of this study, were found to be either actively responding to HIV and AIDS or at the stage of initiating a response to the epidemic.86 Moreover, the influence of Maepa and SACAP in KwaZulu-Natal facilitated the mushrooming of home-based care activities such as in Centocow Mission Station in the Umzimkulu diocese, Holy Cross Mission in the Eshowe diocese, and on a much smaller scale, the training and care in the Dundee diocese.87 Two personnel from Kokstad and one from Dundee were trained in home-based care and counselling at the Durban's Sinosizo project in Amanzimtoti.88 To her credit, an inter-diocesan consultative workshop was held in May 1997; three national workshops on home-based care were conducted in the course of 1997; and home-based care training materials were developed with a strong co-relation with the Zambian and Ugandan models.89 The SACAP AIDS programme therefore introduced the home-based care programme and capacitated volunteers' training. By so doing, the SACAP AIDS ministry made a departure from that of CAN in the sense that "it acknowledged the need for a less random, more focused programme" with a relative degree of autonomy, a constitution and an executive leadership body comprising diocesan representatives.90

The two previous failures of the SACBC AIDS Programme91 did not deter the bishops from trying again. In 1999, they set up another initiative geared towards establishing an AIDS leadership structure for the church's response to HIV and AIDS - with outstanding success this time. It all begun in a January 1999 AIDS workshop that brought together various departments of the SACBC. At that workshop, Bishops Cawcutt and Dowling "were appointed to take forward the work of the AIDS study day".92 They appointed a committee that met twice, on 19 March and 30 July 1999.93 On 5 August 1999, Bishop Cawcutt reported to the plenary session of the SACBC in Mariannhill that "he and Bishop Dowling had been involved with a committee reviewing a Catholic response to the issue of HIV/AIDS".94 The committee consisted of three bishops and representatives from three SACBC departments: the Catholic Development and Welfare Agency (DWA), the Catholic Health Care Association (CATHCA) and Catholic Institute of Education (CIE).95 According to Bishop Cawcutt, its chairperson, the committee was in the process of drawing up a constitution. The committee proposed that a part-time clerical cum administrative person be appointed to run the office from Khanya House for an initial period of six months. The conference endorsed the proposal and indicated that the person's work had to constitute, among other things, fundraising - identifying funding organisations and preparing fundraising proposals.96 According to Bishop Cawcutt, during the six-month period, "the management committee would meet quarterly to review progress".97 Meanwhile, representatives from the CIE, CATHCA and DWA would meet monthly in order to monitor and supervise the work of the part-time employee. It was agreed that the primary task of the office would be "to act as a monitor of developments and an information conduit".98 Information on the issue of HIV and AIDS from the government and agencies working in the field would be passed on to the dioceses from this office. It was proposed that an amount of R60 000 be allocated from the Lenten Appeal to cover the costs of running the office for six months. Bishop Orsmond agreed to join the management committee.99

Following the approval of the proposal by the bishops, the management committee moved speedily to implement it. A new body was created with a new name: the SACBC Catholic National AIDS Office, “to emphasize that it is a conference initiative”.100 The committee was expanded to include representatives from PLWA, the Youth Office and the Gender Desk of the Justice and Peace department. It was confirmed that although regarded as an office, the SACBC National AIDS Office was not to be “typical of SACBC offices as it reports through this committee and not the Secretary-General”.101 Sister Alison Munro was appointed as the new coordinator. Her office was in Khanya House, Pretoria. She was on a sixmonth contract. She was to work under the watchful eye of two committees: the management committee and the supervisory committee.102 The former consisted of representatives of the three SACBC departments (CATHCA, DWA, and CIE), whereas the latter was largely comprised lay representatives of church groups operational at parish level such as donor agencies, women, youth, PLWA103 and health practitioners. 104 Figure 4.1 gives a timeline of the Catholic AIDS leadership in the 1990s.

Meanwhile, the Catholic Medical Mission Board (CMMB) - a well-established body in the USA, which sends medicines, medical supplies, volunteers and funding to developing countries with a view to providing quality health care to the world's poorest - was looking for a partner organisation in Africa for its HIV and AIDS work.105 The CMMB had strong links with many donor organisations, including the Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) which had just announced a five-year programme, the Secure the Future Programme. BMS was willing to spend $100 000 000 in five Southern African countries for HIV and AIDS community-based programmes, with a special emphasis on care and support of women and children. In October 1999, "CMMB approached the SACBC with a proposal to work in partnership with it to fight against HIV/AIDS".106 Subsequently, CMMB wrote to the SACBC National AIDS Office on 10 November 1999 with a proposal that the SACBC sign a partnership in agreement in terms of which CMMB would provide financial support to HIV and AIDS projects in the SACBC region (South Africa, Swaziland and Botswana) under the umbrella of the Bristol Myers Squibb's Secure the Future programme, to the tune of US$1 000 000 per annum for five years.107 The timing could not have been better. The next six months were spent laying the logistical groundwork for what would become by far the most important and successful Catholic AIDS initiative in responding to HIV and AIDS and that would irreversibly change the Catholic's response to HIV and AIDS in South Africa, and indeed in the entire Southern African region.

There is no doubt that Bishop Kevin Dowling had the history of the AIDS Office in mind when in 7 September 2000 he recounted the following:

A lot of time and effort has been invested in setting up this structure staffed at present by Sister Alison Munro and by Johan Viljoen, the Project Officer. It has already established personal links with all the care initiatives of the Church at grassroots level. It is known and recognized at all levels, from the communities to the bishops, as the structure which fulfils the Church's mandate. The office can now co-ordinate projects and programmes, and can monitor and accompany initiatives on the ground thus ensuring accountability to our donors ... Our AIDS Office is functioning efficiently, and we place it at the disposal of CRS and all of those who wish to serve the people of South Africa through the Catholic Church network.108

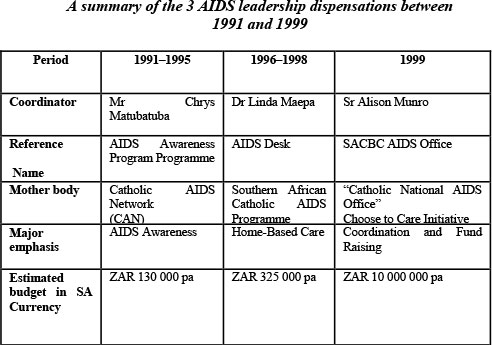

Bishop Cawcutt of Cape Town echoed similar sentiments in a speech reported in the Southern Cross under the title: Bishops' new AIDS view: office to centralize strategy, save money.109 "Our failures have cost us a fortune" conceded Bishop Cawcutt, noting that the new office would have a coordinating role and would not set up projects or train people as had been the aim in the past. A new dispensation in the Catholic response to HIV and AIDS had surely begun. The SACBC had given up attempts to set up new AIDS projects around the country and would instead play a supportive role for projects that already existed through the new national office.110 The characteristics of the three AIDS leadership dispensations discussed in this section are summarised in Table 4.1 below.

Diocesan AIDS committees

Closely related to the AIDS office was another arm of the AIDS leadership structure, the diocesan committees. During the AIDS consultative conference from 14-16 March 1990, organised by the SACBC's Department of Health Care and Education, whose goal was "to set out policy and action guidelines regarding the handling of HIV and AIDS and related issues through the structures of the Catholic Church", the 20 diocesan representatives recommended that AIDS committees be established in each diocese in order to coordinate work at grass-root levels and liaise with the recently formed CAN.111 As a result of a CAN initiative, the first Annual Interdiocesan AIDS Conference was held between 16 and 18 July 1993 at Koinonia Retreat and Conference Centre, Johannesburg. At this conference, the Interdiocesan AIDS Committee was born.112 The main purpose of the conference, which was attended by 45 participants from 24 dioceses, was "to bring the diocesan AIDS coordinators together in order to know one another, exchange ideas, establish links and form an effective Catholic network".113 The idea was to have diocesan committees coordinating AIDS activities at diocese level and link up these at the SACBC level as the interdiocesan committee in order to facilitate a coordinated national and regional response to HIV and AIDS. It was agreed at the 1993 conference that such conferences would be held annually.114

In spite of these measures at national level, only a few dioceses managed to form a committee. The dioceses were to raise funds and hire a full-time diocesan AIDS Coordinator to work with the committee. The challenges facing this initiative were many. Lack of funding, scarcity of information, denial and logistical difficulties were raised as the key ones in 1993.115 In fact, three quarters of the 45 diocesan representatives who had attended the 1993 interdiocesan conference were attending on a voluntary basis. Sister Ancilla Doran of the Tzaneen diocese had been working on AIDS information at the diocese for a year with hardly any budget. Sister Philippa Mamba of the Manzini diocese had a committee of four with whom they had been actively doing AIDS awareness campaigns since her attendance of the March 1990 consultation. They were still in the process of applying for funds.

The archdiocese of Cape Town was more creative in organising its AIDS leadership structure. Under the leadership of the late Father Jack Gillick of the St Mary's Cathedral and Sister Margaret Craig of the Nazareth House, the archdiocese established an AIDS networking body parallel to the national one by the name Catholic AIDS Network-Cape Town.116 According to Craig, the body, which is still operative today, "was a care support system that brought together all Catholic organizations involved in care and treatment of PLWHA in the metropolitan province of Cape Town".117

During the time of CAN (March 1990-May 1995), only the archdiocese of Durban, out of the seven KwaZulu-Natal dioceses, had a full-time diocesan AIDS coordinator and a committee.118 Although the Durban committee had been in existence since 1986, it was not until 1991 that Liz Towell was appointed as the archdiocesan coordinator. In 1990, the committee intensified its efforts in care and AIDS education under the name of the Durban Archdiocesan AIDS Care Committee.119 In 2000, the committee acquired a new name - the Catholic Archdiocese of Durban AIDS Commission (CADAC).120 This was in order to accommodate the new changes in the leadership as well as the change in the church's response to HIV and AIDS. The replacement of the word "care" with "commission" is significant in that care of the sick and the dying was no longer the chief task of the committee; a broader and multifaceted task was envisaged.

The formation of SACAP in May 1995 and the consequent support for diocesan organisation led to the formation of more committees. In Eshowe, Father Gerard Tonque (Clemens) Lagleder was appointed as the diocesan coordinator in March 1996121, whereas in Mariannhill, Sister Jennifer Boysen became the diocesan coordinator in November 19 9 5.122 Several dioceses in KwaZulu-Natal did not have a diocesan committee. At the time of this research, Kokstad, Ingwavuma, and Umzimkulu had neither AIDS committees nor coordinators. Instead, they had AIDS projects that by default were involved with coordinating AIDS activities in the diocese. Nevertheless, coordinators and committees became valuable assets in facilitating networking, exchange and capacity building in the Catholic Church's response to HIV and AIDS during the 1990s.

The Dynamics of AIDS leadership in a complex organisation

There is no simple answer as to why the AIDS leadership structure in the Catholic Church took so long to get on its feet. I found that several factors contributed to this failure. According to the auxiliary bishop of Cape Town, Reginald Cawcutt, the failure was due to administrative reasons. In November 1999, he told the Southern Cross that "seven years ago the SACBC started a national response to the AIDS pandemic in South Africa, but it failed because its projects were led by people who either lacked administrative skills or 'were given no direction'".123 Bishop Kevin Dowling of Rustenburg, an executive member of the new AIDS Office steering committee, blamed the lack of financial resources. He said that he had "been trying for four years to get a community-based response to the AIDS pandemic" in his diocese, where the disease was rampant among men working in the platinum mines, but financing was his biggest problem. He said that he had hoped to have enough money to start a "comprehensive outreach in the villages around the mines" in his diocese in 2000, including a small hospice for those with no one to care for them.124 CAFOD strongly felt that there had not been enough commitment on the part of the Bishops' Conference towards an AIDS response to HIV and AIDS during the 1990s and that had led to the failures.125 Matubatuba indicated to me in an interview that the main hindrance was poor personal relations in the SACBC secretariat, something that became manifest in the manner in which the conference had handled the condom controversy.126 Maepa accused male chauvinism in the Catholic leadership that amounted to differences of opinion, especially in the administration of the National AIDS Office and in the use of condoms as an HIV prevention method.127 This list is by no means complete; various factors had their share, with some, such as the lack of finances and the condom controversy playing a greater role than others.

Nevertheless, I found that organisational tensions in the Catholic Church were the fundamental cause for the delay in setting up AIDS leadership structure. As indicated earlier in this study, since the 1980s, there has been tension between the lay practitioners and the hierarchy in the manner in which the church ought to respond to HIV and AIDS.128As an "open system" the Catholic Church has been an organisation constantly responding to the changes effected by the presence of HIV and AIDS. In line with Kowalewski's analysis, various elements in the church such as medical practitioners, social workers and bishops have differed with regard to AIDS-related statements and activities.129 In the words of Seidler, the Catholic response to HIV and AIDS has developed as a "contested accommodation".130 While the spread of HIV, for instance, pressured the church to allow the use of condoms, other forces in the church such as its moral teachings led it to resist accommodating such a practice.

Similarly, change in the church's AIDS-related activities and discourses were negotiated within the organisational power structures. On the one hand, the hierarchy, represented by the bishops, maintained a hard line position on the church's moral teachings and thereby opposed the use of condoms. In other words, as the higher-level officials, the bishops defended the official charter of the organisation. On the other hand, the laity, represented by nurses, counsellors, medical doctors and care givers, was willing to compromise the church's official teachings at individual level.131 Meanwhile, the priests, as the lower-level officials acted as conciliatory intermediaries.

The entire AIDS leadership, from the SACBC AIDS coordinator down to the diocesan committees, notwithstanding the AIDS project leadership, found itself confined between opposing ends in the church's response to HIV and AIDS. Because the majority of leaders in the AIDS ministry were lay persons, the bishops often felt disregarded and disobeyed. They therefore exercised their formal organisational power, and in the end, the entire AIDS structure became frustrated. This partly explains why on two separate occasions the bishops relieved National AIDS coordinators of their duties without prior warning.

Arguably, the failures of the SACBC AIDS Office during the 1990s had something to do with the lack of representation of the lay leadership in policy making. In 1993, the Pastoral Forum132 was created, in which lay delegates would have the possibility of deliberating key issues together with the bishops.133 Consultations for creating the Steering Committee for this forum were completed at the end of 1998 and the delegates from the SACBC provinces met with the relevant episcopal members to form the committee for the first time in March 1999. The creation of the Steering Committee of the Pastoral Forum as a new structure for the church in Southern Africa on 17 March 1999 meant that the laity could participate in decision making on pertinent issues such as HIV and AIDS at the highest level. The creation of this structure was in the spirit of Lumen Gentium of Vatican II in 1965 as well as the recommendations of the World Synod of Bishops in 1985, which categorically stated the following: "Because the Church is a communion, there must be lay participation and co-responsibility at all of her levels."134

As I have argued elsewhere,135 the entire leadership and response of SACBC to HIV and AIDS changed considerably for the better from 2000 onwards. This coincided with the influx of large sums of monies, notably, the five-year PEPPFAR funding contract. In the recent past, however, AIDS funding has decreased, a trend that is not unique to SACBC.136 Nevertheless, it is significant that the successful establishment of SACBC AIDS leadership structure coincided with the inclusion of the lay leadership in policy-making matters. To argue that the reason why AIDS leadership failed during the 1990s is solely due to a lack of representation of the lay people in policy making would be oversimplifying a much more complicated matter. These are, however, not unrelated. The inclusion of lay people in top leadership might have eased power tensions in the organisation. It is significant that in 1999, the National AIDS Office was for the first time supervised by two committees, one entirely consisting of lay representatives. It is also significant that around the same time, the bishops agreed for the first time to re-examine their stance on the use of condoms in HIV prevention.137 Arguably, the inclusion of the lay leaders in the SACBC created a new attitude and unanticipated willingness to listen to the concerns of lay practitioners.

Conclusion

In this article, I have enumerated various measures undertaken by the SACBC in its new and urgent endeavour to respond to the AIDS crisis between 1991 and 1999. The strong determination by the hierarchy to put up a "responsible" AIDS leadership was marred by internal conflicts over the use of condoms in HIV prevention. The lack of coordination in the AIDS response not only frustrated willing donors, leading to financial inadequacies and regular closures of the AIDS office, but more so, delayed the much-needed support for creative responses by ordinary members at the grass-roots level.

The tensions that ensued may be seen in the context of an organisation caught in between what Kowaleski termed "contested accommodation" and "impression management" organisational principles.138 The bishops as the official custodians of institutional power attempted to maintain the status quo in policy as well as organisational equilibrium in leadership by allowing limited accommodation of the controversial lay demands. Meanwhile, they managed the public perception of the church in relation to the AIDS crisis by tactfully maintaining a hard-line position, while at the same time promising to be relevant to the host social environment. This explains why, by the end of 1999, the bishops had started seeing the monster they had created by fighting the use of condoms; to bless the use of condoms, however, would mean an organisational crisis. The church had lost a great deal of public trust, especially with regard to its intrinsic interests in HIV prevention, whether a protection of a traditionally held ethical code or the saving of people's lives at risk on account of the AIDS disease. In any event, the SACBC had to simultaneously juggle loyalty to its official teachings, its identity, and a contextual relevance in the face of HIV and AIDS. It had to maintain organisational equilibrium or risk schism; it had to carefully navigate its post-conciliar139 identity in a post-apartheid context. By and large, the period under review depicted a Catholic Church more in reaction than in response to HIV and AIDS.

Works consulted

Abell, P. 2006. Organization theory: an interdisciplinary approach. London: University of London Press. [ Links ]

Ackerman, D. 2005. Engaging stigma: an embodied theological response to HIV and AIDS. Scriptura 2, February, 385-395. [ Links ]

African Religious Health Assets Programme (ARHAP). 2005. International Case Study Colloquium: background and conceptual framework for contributors. Cape Town: ARHARP. [ Links ]

Bate, S. (ed.) 2003. Responsibility in a time of AIDS: a pastoral response by Catholic theologians and AIDS activists in Southern Africa. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Bate, S. (ed.) 1996. Serving humanity - a Sabbath reflection: the pastoral plan of church in Southern Africa in Southern Africa after seven years. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [ Links ]

Bate, S. 2003. Catholic pastoral care as a response to HIV/AIDS pandemic in Southern Africa. Journal of Pastoral Care and Counselling 57(1), Spring, 197-209. [ Links ]

Denis, P. 2009. AIDS and Religion in sub-Saharan Africa in a Historical Perspective. Unpublished paper, Sinomlando Centre for Oral History and Memory Work, University of KwaZulu-Natal, May. [ Links ]

Denis, P. 2008. The ethics of oral history, in Oral history in a wounded country, edited by P Denis & R Ntsimane. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press. [ Links ]

DeYoung, K. 2001. AIDS challenges religious leaders. Washington Post, August, 23-33. [ Links ]

Dilger, H. 2009. Religion, the virtue-ethics of development and the fragmentation of health politics in Tanzania in the wake of neoliberal reform processes and HIV/AIDS. Africa Today 56(1), 89-110. [ Links ]

Douna, S. & Schveuder, H. 2002. Economic approaches to organizations. London: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Dowling, K. 2001. The church's response to AIDS. Grace and Truth 18(2), August, 16-21. [ Links ]

Dowling, K. 2000. Address to the CRS assessment team: a foreword to the Joint Southern African Catholic Bishops' Conference and Catholic Relief Services HIV/AIDS Assessment, September 7-19, Durban, South Africa. [ Links ]

Dube, M. 2002a. Theological challenges: proclaiming the fullness of life in the HIV/AIDS and global economic era. International Review of Mission XCI(363), 535-549. [ Links ]

Dufour, F. 1999. Condom strategy: a failure. Catholic Y Link 67, September, 4-7. [ Links ]

Emmanuel, C. 2001. Small Christian Communities. Break the silence: community serving humanity. Pretoria, SACBC. [ Links ]

Epprecht, M. 2009. Heterosexual Africa? The history of an idea from the age of exploration to the age of AIDS. Toronto: Swallows Press. [ Links ]

Fuller, J & Keenan, J. 2000. Tolerant signals. America, September, 23-40. [ Links ]

German Bishops Conference. 1993. Bevölkerungs-wachstum und Entwicklungsforderung (Population Policy and Development). [ Links ]

Goffman, E. 1959. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Grele, R (ed.) 1985. Envelopes of sound: the art of oral history. Chicago: Precedent. [ Links ]

Grele, R. 1985. Movement without aim: methodological and theoretical problems in oral history, in Envelopes of sound: the art of oral history, edited by G Ronald. Chicago: Precedent Publishing. [ Links ]

Grootaers, J. 1994. Humanae Vitae, encyclique de Paul VI. Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Geographie ecclesiastique 25, February, 328-34. [ Links ]

Gusman, A. 2008. HIV/AIDS and the "FBOisation" of Pentecostal Churches in Uganda. Conference: Religious engagements with AIDS in Africa, Copenhagen, 28 and 29 April. [ Links ]

Haddad, B. 2002. Gender violence and HIV/AIDS: a deadly silence in the Catholic Church. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 114, November, 93-103. [ Links ]

Haddad, B. 2006. 'We pray but we cannot heal': theological challenges posed by the HIV/AIDS crisis. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 125, July, 80-90. [ Links ]

Hastings, A (ed). 1991. Modern Catholicism: Vatican II and after. London: SPCK. [ Links ]

HEARD. 2005. Faith-based organisations and HIV/AIDS in Uganda and KwaZulu-Natal: a final report. Durban: HEARD. [ Links ]

Henriques, A. 1997. Vatican II in the Southern Cross. Bulletin for Contextual Theology in Southern Africa and Africa 4(1), January, 31-39. [ Links ]

Hurley, D. 1991. Pastoral plan: where to now? The Archdiocese of Durban evaluates the renew process after two year period. Internos 3(2), April/May:19-20. [ Links ]

Iliffe, J. 2006. The African HIV/AIDS epidemic: a history. Athens: Ohio University Press. [ Links ]

Inter-Regional Meeting of Bishops in Southern Africa (IMBISA). 2008. http://www.africaonline.co.zw/imbisa/index.html. Accessed on 13 February 2008. [ Links ]

John Paul II. 1981, Familiaris Consortio. Washington: United States Catholic Conference. [ Links ]

Joinet, B. 1994. Survivre face au SIDA en Afrique. Paris: Karthala. [ Links ]

Joshua, S. 2006. The history of AIDS in South Africa: a Natal ecumenical experience in 1987-1990. Unpublished Thesis Dissertation. University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Joshua, S. 2007. Memories of AIDS: a critical evaluation of Natal Cleric's reflections on their AIDS experiences between 1987 and 1990. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae XXXIII(1), May:107-132. [ Links ]

Karim, S. Abdool & Karim, Q. Abdool (eds.) 2007. HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kark, S. & Kark, E. 1999. Promoting community health: from Pholela to Jerusalem. Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Keenan, J. (ed.) 2000. Catholic ethicists on HIV/AIDS prevention. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Kelly, K.T. 1998. New directions in sexual ethics: moral theology and the challenge of AIDS. London: Geoffrey Chapman. [ Links ]

Kowalewski, M.R. 1994. All things to all people: the Catholic Church confronts the AIDS crisis. Albany: State University of New York Press. [ Links ]

Liebowitz, J. 2004. The impact of faith-based organizations on HIV/AIDS prevention and mitigation in Africa. Unpublished paper, HEARD, University of Natal, October 2002; Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division, Faith-Based Organisations and HIV/AIDS in Uganda and KwaZulu-Natal: a final report Durban: HEARD. [ Links ]

Lindholm, T. (ed.) 2004. Facilitating freedom of religion on belief: a desk book. Leiden: Berkeley. [ Links ]

Marcus, T. 2004. To live a decent life: bridging the gaps. Pretoria: SACBC. [ Links ]

Mathews, D, Larson, D. & Barry, C. 1998. The faith factor: an annotated bibliography of clinical research on spiritual subjects, Vols 1, 2 & 3. Rockvile: National Institute for Healthcare Research. [ Links ]

Mbali, M. 2009. Progressive health worker AIDS activism in South Africa (1982-1994) Unpublished doctoral dissertation. London: Oxford University. [ Links ]

McSweeney, W. 1980. Roman Catholicism: the search for relevance. New York: St. Martins. [ Links ]

Messer, D. 2004. Breaking the conspiracy of silence: Christian churches and the global AIDS crisis. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Moloantoa, C. 1991. The AIDS pandemic: a challenge to the Christian community. Internos 3(5), September/October, 12-13. [ Links ]

Mudau, Z. 2000. An evaluation of the HIV/AIDS ministry in Umgeni Circuit of ELCSA. Unpublished Master's Dissertation. University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

Munro, A. 2013. Response of the Catholic Church to AIDS: an SACBC AIDS office perspective. Grace & Truth 30, July to August, 6-37. [ Links ]

Natal Witness. 2002. The sacredness of life: A Catholic opinion on condoms and AIDS by a group of Dominicans in Pietermaritzburg, 20 February. [ Links ]

National AIDS Convention of South Africa. 1992. Facsimile Transmission from R van Heerden (NACOSA) to Ms Cecilia Moloantoa of SACBC on 16 September 1992, Ref: Invitation to act as a work group facilitator at the National AIDS Convention of South Africa (NACOSA): 23 and 24 October: NASREC. [ Links ]

New Mexico Bishops. 1990. A pastoral statement on AIDS and the religious. Released on 18 June. [ Links ]

News and Bulletin of Catholic Archdiocese of Durban. 1992. Catholic AIDS Care programme: Youth Trainers Programme, 280, June, 48-49. [ Links ]

News and Bulletin of Catholic Archdiocese of Durban. 1992. AIDS Care Committee - Youth Programmes, 284, October, 86. [ Links ]

News and Bulletin of Catholic Archdiocese of Durban. 1998. The Renew Programme, 330, October, 98. [ Links ]

News and Bulletin of Catholic Archdiocese of Durban. 1998. Christmas, a time of hope, 352, December, 73. [ Links ]

Nicolson, R. 1995. AIDS: a Christian response. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster. [ Links ]

Nicolson, R. 1996. God in AIDS: a theological enquiry. London: SCM Press. [ Links ]

Oppenheimer, G. & Bayer, R. 2007. Shattered dreams? An oral history of the South African AIDS epidemic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Parker, W. & Birdsall, K. 2005. HIV/*AIDS, stigma and faith-based organisations: a review. Johannesburg: DFID/Futures Group. [ Links ]

Pick, S. 2006. HIV/AIDS: our greatest challenge yet! The road ahead for the Church in South Africa. London: Paarl Print. [ Links ]

Pope Paul VI. 1968. Humanae Vitae. New York: Paulist. [ Links ]

Pope Pius XI. 1930. Encyclical letter Casti connubi. AAS 22, 560. [ Links ]

President Mbeki's letter to world leaders. 2000. 3 April. http://wwwvirusmyth.net/net/AIDS/news/lettermbeki.htm. Accessed 7 March 2005. [ Links ]

Rakoczy, S. 2005. Catholic theology in South Africa: an evolving tapestry. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 122, July, 34-106. [ Links ]

Richardson, N. 2006. A call for care: HIV/AIDS challenges the Church. [ Links ]

Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 125, July, 38-50. [ Links ]

Saayman, W & Kriel, J. 1992. AIDS: the leprosy of our time? Johannesburg: Orion. [ Links ]

SACBC. 1984. IMBISA - First plenary session: concern, consultation, cooperation. Internos 2, September/October, 3-9. [ Links ]

SACBC. 1989. Community serving humanity: pastoral plan of the Catholic Church in Southern Africa, vision statement. Pretoria: Southern Africa Bishops Conference. [ Links ]

SACBC. 1990. The Bishops Speak Vol.5 (1988-1990). Pretoria: SACBC. [ Links ]

Sadie, D. 1990. A Catholic Indaba: 120 bishops and religious superiors plan future role of church. Internos 2(3), July/August, 6-7. [ Links ]

Schmid, B. 2006. AIDS discourses in the Church: what we say and what we do". Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 125, July, 91-103. [ Links ]

Scorgie, F. 2001. Virginity testing and the politics of sexual responsibility: implications for AIDS intervention. African Studies 61(1), 55-76. [ Links ]

Scorgie, F. 2005. What religious leaders and communities are doing about HIV and AIDS: reflections on the work of the Roman Catholic Mission of Centocow. Unpublished paper. [ Links ]

Seidler, J. & Meyer, K. 1989. Conflict and change in the Catholic Church. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [ Links ]

Selznick, P. 1966. Foundations of the theory of organization. American Sociological Review, 13(1), February, 25-35. [ Links ]

South Africa Medical Research Council. 2001. The impact of HIV/AIDS on adult mortality in South Africa. http://www.mrc.ac.ta/bod. Accessed on 22 June 2006. [ Links ]

South African Catholic Bishop's Conference. 2002. Statement on prevention of mother to child transmission, 10 April. [ Links ]

South African Medical Research Council. 1994. HIV surveillance - what grounds for optimism? South African Medical Journal, 90(11), November, 1, 62-4. [ Links ]

Southern Africa Catholic Bishop's Conference. 2005. Minutes of the Plenary Session held between January 1984 and December 2005. [ Links ]

The Mercury, 1984-2005, yearly bound volumes by the Natal City Library, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

The Natal Witness, 1984-2005, yearly bound volumes by the Natal City Library, Pietermaritzburg. [ Links ]

The Southern Cross, 1984-2005, preserved in the St. Joseph's Theological Institute's Library Archives, Cedara. Available: (http:www.scross.co.za/contact.htm). [ Links ]

Trinitapoli, J. & Regnerus, M.D. 2006. Religion and HIV risk behaviours among married men: Initial results from a study of rural Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45(4), 505-528. [ Links ]

UNAIDS. 2006. A faith-based response to HIV in Southern Africa: the choose to care initiative. Geneva: UNAIDS. [ Links ]

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Called to Compassion and Responsibility: A Response to HIV/AIDS Crisis (Washington: National Conference of Catholic Bishops, 1989), ff. [ Links ]

USCC Administrative Board. 1987. The many faces of AIDS: a gospel response. Origins 17(28), 482-489. [ Links ]

Viljoen, J. 2000. Comments on the government Gazette No 21089 of 25 April 2000, 1 November 2000. [ Links ]

Vitillo, R. 1993. Ethics considerations in testing for HIV. An address to the Caritas Internationals working group on AIDS meeting held at Kampala, Uganda in September. [ Links ]

Weinreich, S. & Benn, C. 2004. AIDS - meeting the challenge: data, facts, background. Geneva: WCC Publications. [ Links ]

Whiteside, A. & Sunter, C. 1997. AIDS: the challenge for South Africa. Cape Town: David Philip. [ Links ]

Whiteside, A. 1991. HIV infection: the nature of the economic impact - an overview. Paper presented at the Economic Impact of AIDS in South Africa Workshop held on 22 and 23 July in Durban. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. 2006. Appreciating assets: the contribution of religion to universal access in Africa, Report for the World Health Organization, in De Gruchy, Steve et al. Cape Town: ARHAP. [ Links ]

Archival Sources

AIDS Executive meeting, Minutes, 13 January 1996. [ Links ]

AIDS Executive meeting, Minutes, 4 May 1996. [ Links ]

Catholic Diocesan Magazine, 20 June 1995. [ Links ]

Catholic National AIDS Office, Minutes of Management committee, 13 October 1999. [ Links ]

Centre for South-South Relations.

EB/as625g, Letter to Mr Lucan Coetsee, 29 March 1996. [ Links ]

Interdiocesan AIDS Committee, AIDS Report, August 1991. [ Links ]

Interdiocesan AIDS conference, Report, 23 July 1993. [ Links ]

Letter (email) to Eileen Walsh, 10 November 1999. [ Links ]

Letter to Cathy Corcoran, 8 April 1998. [ Links ]

National AIDS Committee Meeting, Minutes, 13 October 1999. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pietermaritzburg, 4 January 1990. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pietermaritzburg, 6 January 1990. [ Links ]

SACBC, A Pastoral letter on AIDS, 1990. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS project, Funding proposal 1991. [ Links ]

SACBC, Interdiocesan AIDS Committee, minutes of meeting on 14 June 1991. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report to CAFOD 1993/1994. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report 1993. [ Links ]

SACBC, Department of Health Care and Education, Annual Report, 1993. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pretoria, 18-25 January 1994. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report 1995. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pretoria, 17-24 January 1995. [ Links ]

SACBC, Letter from Chrys Matubatuba, 13 March 1995. [ Links ]

SACBC, Letter from Secretary General, 17 March 1995. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS project, Funding proposal 1995. [ Links ]

SACBC, SACAB Constitution, 1995. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pretoria, 16-23 January 1996. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS office, Report 1996. [ Links ]

SACBC and SACAP Report, 7-17 August 1996. [ Links ]

SACBC, Report of SACAB AIDS desk to SACAB administrative Board, August 1997. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pretoria, 18-25 January 1998. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Marianhill, 6-12 August 1998. [ Links ]

SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at Marianhill on 5-11 August 1999. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS Management Committee, Minutes, 30 July 1999. [ Links ]

SACBC, Catholic National AIDS Office Proposal, 13 December 1999. [ Links ]

SACBC, AIDS Management Committee, Minutes, 25 April 2000. [ Links ]

SACBC and CRS HIV/AIDS assessment report, 7-19 September 2000. Star, 15 June 1995. [ Links ]

World Synod of Bishops, Final Relatio C.6, Rome, 1985. [ Links ]

Interview

Boysen, 23/11/2007.

Craig, Margaret, 26/06/2009. [ Links ]

Lagleder, 10/10/2007. [ Links ]

Maepa, Linda, 21/07/2009. [ Links ]

Matubatuba, Chris, 11/07/2009. [ Links ]

Mlambo, 10/07/2008. [ Links ]

Ndlovu, Immaculata, 15/09/2007. [ Links ]

Neil, Bikinia and Ross, Douglas, 15/10/2007. [ Links ]

1 Dr Stephen Muoki Joshua is a research fellow at the Research Institute for Theology and Religion, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa.

2 "Indaba" is the Zulu word for "a meeting". It is often used in South Africa to denote a significant gathering.

3 David Sadie, "A Catholic Indaba: 120 bishops and religious superiors plan future role of church," Internos Vol 2, No 3 (July/August 1990), 6-7.

4 David Sadie, "A Catholic Indaba: 120 bishops and religious superiors plan future role of church," Internos Vol 2, No 3 (July/August 1990), 6-7; Southern Cross, SACBC Press Release, August 1990.

5 Sadie, A, Catholic Indaba, 6.

6 Cited in David Sadie; see Sadie, A Catholic Indaba, 6.

7 Paul Decock, digital recording, interview conducted by author at Cedara, Pietermaritzburg on 10 July 2006.

8 Southern Cross "AIDS", 8 April 1990.

9 See Stephen Joshua, "Memories of AIDS: a critical Evaluation of Natal clerics' reflections on their AIDS experiences between 1987 and 1990." Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae: Journal of the Church History Society of Southern Africa Vol. XXXIII No. 1 (May 2007), 107-132.

10 Mandisa Mbali, Progressive health worker AIDS activism in South Africa (1982-1994), unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oxford University, 2009.

11 Centre for South-South Relations (CSSR), AIDS and the Church: Report of visit to Uganda and Tanzania (Athlone: CSSR, 1994), 7; See also an interview with Philippe Denis, a Dominican brother who visited Uganda and Kenya in 1994 to learn more about HIV and AIDS in children, Philippe Denis, digital recording, interview conducted by author at his home in Scottsville, Pietermaritzburg, 12 October 2008.

12 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at Mariannhill on 5-11 August 1999.

13 SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report to CAFOD 1993/94, prepared by Chrys Matubatuba, the interdiocesan AIDS Coordinator.

14 Cecilia Moloantoa, "The AIDS pandemic: a challenge to the Christian Community," Internos Vol. 3 No.5 (September/October 1991), 12 and 13.

15 Southern Cross, "The church is doing nothing about AIDS? Think again!" 26 November 2000.

16 SACBC, Minutes of a plenary meeting held in Pietermaritzburg 4 January 1990.

17 SACBC, A pastoral letter on AIDS (Pretoria: SACBC, 1990).

18 SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report to CAFOD 1993/94, prepared by Chrys Matubatuba, the interdiocesan AIDS Coordinator.

19 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held on 6-13 January 1989 in St John's Vianney Seminary, Pretoria.

20 SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report to CAFOD 1993/94, prepared by Chrys Matubatuba, the interdiocesan AIDS Coordinator.

21 SACBC AIDS project, proposal for funding for the Catholic AIDS Network project in Southern Africa, prepared by Mrs CM Moloantoa, Coordinating Secretary, Department of Health Care and Education, SACBC, Khanya House, Pretoria, June 1991, 1.

22 SACBC AIDS project, proposal for funding for the Catholic AIDS Network project in Southern Africa, prepared by Mrs C.M Moloantoa, Coordinating Secretary, Department of Health Care and Education, SACBC, Khanya House, Pretoria, June 1991, 1-2.

23 Oppenheimer and Bayer, An oral history of the South African AIDS Epidemic, 39-40.

24 The members of CAN's executive Committee included: Mrs C. Moloantoa (coordinator), Fr E Blaser (executive member of the Justice and Peace Commission), Sr S M Waspe (secretary), Dr R King (Catholic Doctors Guild), Dr S Browde (Witwatersrand Hospice and NAMDA member), Dr D Sifris (consultant on HIV/AIDS clinic in Johannesburg), Sr P Mbambo (coordinator for the AIDS Project in Manzini Diocese, Swaziland), Mrs R Selema (representative for Gaborone Diocese), Mrs S Mlambo (representative for Durban Diocese and Catholic Nurses Guild), Mr G Pugin (representative for Cape Town Diocese), Mr P Battison (representative for People Living with AIDS - Johannesburg), and Mrs V Hanorich (Witwatersrand Hospice). See SACBC AIDS project, proposal for funding for the Catholic AIDS Network project in Southern Africa, prepared by Mrs CM Moloantoa, Coordinating Secretary, Department of Health Care and Education, SACBC, Khanya House, Pretoria, June 1991, 1-2.

25 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held on 6 January 1990, in Pretoria.

26 SACBC, Interdiocesan AIDS Committee, Minutes of a meeting held on 14 June 1991 at Khanya House, Pretoria.

27 SACBC, Interdiocesan AIDS Committee, Minutes of a meeting held on 14 June 1991 at Khanya House, Pretoria.

28 SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, Report to CAFOD 1993/94, progress, 2.

29 The dioceses of Bethlehem and Kroonstad are in the Freestate province.

30 Reginald Cawcutt, Statement on Mr Chrys Matubatuba, presented to the SACBC Secretary General, Bro Jude Pieterse on 27 March 1995.

31 SACBC, Letter written by the Secretary General to all conference members, Re: Mr Chrys Matubatuba - AIDS Coordinator, 17 March 1995.

32 SACBC, Letter from Chrys Matubatuba, AIDS Programme Coordinator to Bro Jude Pieterse, Secretary General, Response to your two letters addressed to me and both dated 4 March 1995, 13 March 1995.

33 SACBC, Letter from Chrys Matubatuba, AIDS Programme Coordinator to Bro Jude Pieterse, Secretary General, Response to your two letters addressed to me and both dated 4 March 1995, 13 March 1995.

34 SACBC, Letter written by the Secretary General to all conference members, Re: Chrys Matubatuba - AIDS Coordinator, 17 March 1995.

35 SACBC, Letter written by the Secretary General to all conference members, Re: Chrys Matubatuba - AIDS Coordinator, 17 March 1995.

36 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at St Peter's Seminary, Pretoria on 17-24 January 1995.

37 Chrys Matubatuba, a telephonic interview conducted by the author on 10 July 2009.

38 Star, "Condom workshop irk bishops", 15 June 1995.

39 Correspondence Letter, written by SACBC Associate Secretary General, Emil Blaser, ref.: EB/as625g, to Mr Lucas Coetsee, 29 March 1996.

40 Star, "AIDS campaigner fights dismissal," 26 March 1996.

41 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at the St Peter's Seminary, Pretoria on 16-23 January 1996.

42Catholic Diocesan Magazine (Johannesburg), "Condoms not fitting, say bishops", 20 June 1995.

43 SACBC AIDS project, proposal for funding for the Catholic AIDS Network project in Southern Africa, prepared by Mrs CM Moloantoa, Coordinating Secretary, Department of Health Care and Education, SACBC, Khanya House, Pretoria, June 1991, 1-2.

44 Interdiocesan AIDS committee, AIDS report presented by Cecilia Moloantoa to the August 1991 SACBC plenary session.

45 SACBC, AIDS Awareness Programme, report presented to the January 1995 plenary session by the coordinator, Mr Chrys Matubatuba.

46 The SACBC region covers South Africa, Swaziland and Botswana.

47 SACBC AIDS Office, Annual Report 1996, Prepared by Linda Maepa, 1.

48 SACBC AIDS Office, Annual Report 1996, Prepared by Linda Maepa, 1.

49 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at the St Peter's Seminary, Pretoria on 16-23 January 1996.

50 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at the St Peter's Seminary, Pretoria on 16-23 January 1996.

51 SACBC, Minutes of the plenary session held at the St Peter's Seminary, Pretoria on 15-23 January 1997.

52 Linda Maepa, e-mail interview conducted by the author on 21 July 2009.

53 SACBC AIDS Office, Annual Report 1996, Prepared by Linda Maepa, 4.

54 Linda Maepa, telephonic interview conducted by the author on 24 July 2009.