Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versão On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versão impressa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.39 supl.1 Pretoria Ago. 2013

A brief history of belief in the Devil (950 BCE - 70 CE)1

Izak Spangenberg

Department of Biblical and Ancient Studies, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

It is strange but true: belief in the Devil is alive. This fact is brilliantly argued by Robert Muchembled in his book A History of the Devil: From the Middle Ages to the Present (2003). He says: "In fact, for almost a thousand years, he had never really gone away. The devil has been part of the fabric of European life since the Middle Ages, and has accompanied all its major changes" (Muchembled 2003:1). This article presents a brief history of the origin and development of the belief in Satan from the First Temple period (950-586 BCE) to the Second Temple period (539 BCE-70 CE) in order to answer the questions: When did the belief in the Satan appear? Could Judaism and Christianity do without this character?

If you asked a theologian the question (...): Who is Satan? he would doubtless answer: Satan is the Commander-in-chief of the fallen angels. (Corte 1958:7)

Introduction

Almost thirty years ago, Jimmie Loader published an article in the Afrikaans newspaper Beeld titled "Liefs na die duiwel met ou Niek!" ("To Hell with Old Nick"). He argued that the Devil ("Old Nick") is a non-existent beast, since a truly monotheistic religion cannot accommodate two eternal forces responsible for events in the world (Loader 1984).2 His argument is similar to that of Cees den Heyer, who says: "Monotheism is a 'game' with no more than two players, God and human beings. The origin of evil and human suffering cannot be sought outside these two players" (1998:29). These may be good theological arguments encouraging modern-day Christian believers to discard belief in the Devil, but they are at variance with what we know of Second Temple Judaism. The present article argues that Second Temple Judaism, a monotheistic religion which evolved out of Yahwism (a polytheistic religion), could not satisfactorily explain the suffering experienced by the Jews during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Believers consequently resorted to belief in Satan (Belial/Lucifer/Devil) as a way of making sense of their world. This historical overview may help us to understand why some modern-day Christians still believe in the Devil. For some reason, they are unable to accept complete responsibility for things that happen to them or for which they are partly responsible. Think of Hansie Cronjé, the former South African cricket captain, who claimed that the Devil made him become involved in match-fixing. On the other hand, there are theologians like Carl Braaten who, contrary to Loader and Cees den Heyer, argue that "True Christianity is stuck with the Devil ..." Christianity cannot do without this character (cf. Oldridge 2012:92).

If one wishes to understand the origin of belief in Satan in Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity, one has to study the history of Israel's religion. The information presented in the following sections is not based on original research into the two religions but on recent research conducted by other biblical scholars. However, none of the latter focused exclusively on the introduction of Satan into the religion of Israel. This article is an attempt to dovetail their research with research into apocalypticism, Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity in order to gauge when Satan became an important character and why.3 Moreover, this article would like to engage with Braaten's statement that Christianity cannot do without this character.

A short history of Israel's religion and the belief in Satan

Preliminary comments

The first step in research into belief in Satan is to consider the use of the word satan in the Old Testament. Depending on the context, the Hebrew word satan can act as a noun or a verb. The verb is usually translated as "to bear a grudge"/"to cherish animosity"/"to oppose" (cf. Ps 38:21; 71:37; 109:4, 20, 29). The noun is usually translated as "opponent"/"adversary" and can refer to either a human or a heavenly being. There are only three books in the Old Testament in which the noun is used to refer exclusively to a heavenly being: Zechariah 3:1-2; Job 1:6-12; 2:1-7:1 Chronicles 21:1.4 However, none of these books characterises "Satan" as Yahweh's opponent; he is merely a member of the heavenly court. When it comes to the use of the noun in the three books, it is important to remember that none of the books originated during the First Temple period (950-586 BCE). They were all written during the Second Temple period (539 BCE-70 CE). This leads to the questions: Why do the earlier books not mention this character? Why do we read about him only in material written during the Second Temple period? If these questions are to be answered, recent research into the religion of Israel has to be consulted.

First Temple period (950-586 BCE)

Younger biblical scholars studying the religion of Israel are unanimous that this religion was not monotheistic from the start (Albertz 2009:374; 2011:37). Yahwism, Israel's religion during the First Temple period (950586 BCE), was, like other Northwest Semitic religions, polytheistic (Niehr 1995:71-72; Smith 2004:101-110). Even scholars who do not accept the current consensus viewpoint acknowledge that places and personal names of Iron Age I reflect polytheistic worship in Israel: "The place names and the personal names preserved from Iron Age I reveal the designations of at least five deities that were known in Palestine at this time" (Hess 2007:242). The five deities are: (1) Baal; (2) Astarte; (3) the divine sun (semes); (4) the moon deity Yerah; and (5) Anat (Baal's consort) (Hess 2007:242-245). The Israelites living during the First Temple period evidently believed in the existence of more than one god. In other words, they believed in a pantheon of gods. Some of the psalms give evidence of this:

God takes his place in the court of heaven

to pronounce judgement among the gods:

'How much longer will you judge unjustly

and favour the wicked?' (Ps 82:1-2).5

In the skies who is there like the LORD;

who like the LORD in the court of heaven,

a God dreaded in the council of the angels,

great and terrible above all who stand about him?

LORD God of Hosts, who is like you?

Your strength and faithfulness, LORD, are all around you (Ps 89:6-8).6

Like other Northwest Semitic peoples, the Israelites believed that there was a palace in heaven where a supreme deity lived with his wife and children. They were attended by a host of servants, some of whom had the task of communicating with human beings, keeping them informed about the plans and wishes of the supreme deity. The story of Jacob's dream reflects something of this. He saw a staircase, with angels descending and ascending and, although, he did not receive a message via these angels but directly from Yahweh, it is evident that Yahweh is accompanied by angels (Gen 28:1015). The story recounting how King Jehoshaphat consulted a number of prophets before he and Ahab, the King of Israel, launched an attack on Ramoth-gilead may also serve as an example. A prophet called Micaiah disagreed with the other prophets and warned the kings that an attack would lead to defeat. King Ahab was not impressed by this prophecy and accused the prophet of never having a good word for him as king. Micaiah then narrated a vision he had seen. He said:

I saw the LORD seated on his throne, with all the host of heaven in attendance on his right and on his left. The LORD said, "Who will entice Ahab to go up and attack Ramothgilead?" One said one thing and one said another, until a spirit came forward and, standing before the LORD, said, "I shall entice him". "How?" said the LORD. "I shall go out", he answered, "and be a lying spirit in the mouths of all his prophets." "Entice him; you will succeed," said the LORD. "Go and do it" (1 Kings 22: 19-22).7

It was now up to the kings to decide whether they should follow this advice or that given by the other prophets.

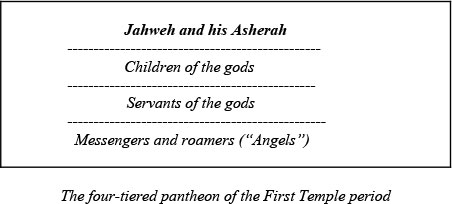

The Israelite divine pantheon was structured hierarchically, like all other pantheons. It had four tiers (Smith 2004:105-119). The top tier was inhabited by the supreme god and his consort. Below them were their children, often referred to as the "sons of God." The next tier was inhabited by the servants and caretakers. The lowest level was the home of the messengers and roamers. This group is called mal'ákîm in Hebrew, the standard translation for which is "angels". The angels had two tasks: (1) to keep the supreme god informed about what was happening on earth, and (2) to share his plans and desires with humans on earth. Those who kept the supreme god informed may be called "roamers", while those who carried his messages may be called "dispatchers". The supreme god was not omniscient, but, rather, was well informed by the angels roaming the earth. The angels who visited Abraham at the terebinth of Mamre, and later on, Lot at Sodom, may serve as examples of dispatchers (Gen 18:2, 22; 19:1, 12-13).

None of the angels are mentioned by name during this period in Israel's history. This may be because they were regarded as the lower-ranking members of the pantheon. This eventually changed during the Second Temple period and, more specifically, the Hellenistic period (Collins 1999:339).

There are two other groups of heavenly beings which readers will encounter in their reading of the Old Testament: (1) the seraphim, and (2) the cherubim. They probably belonged in the third tier of the pantheon. The seraphim were snakelike gods with six wings (Is 6:1-3; 14:29; 30:6), while the cherubim looked like winged lions. According to one tradition in the Old Testament, the cherubim guarded the entrance to the Garden of Eden which was located in the East (Gen 3:24; Ezek. 28:14). According to another tradition they had to guard the life in the divine garden (Ezek 41:17-25). Apart from this they were responsible for transporting the supreme god's throne. Yahweh is often referred to as "the LORD of Hosts who is enthroned upon the cherubim" (1 Sam 4:4; 2 Sam 6:2; Is 37:16; Ezek 10:20-22). The temple in Jerusalem had two statues of cherubim (1 Ki 6:29-35), beneath which stood the Ark of the Covenant (1 Ki 8:6-8).

The divine pantheon of the First Temple period (950-586 BCE) may be depicted as follows (Handy 1995:27-43; Smith 2004:110-114):

During this period, disasters, cataclysms, droughts, floods and illnesses were regarded either as acts of Yahweh or calamities brought about by one of the lower-ranking gods. Unlike monotheism, polytheism makes it easier for believers to explain and cope with disasters (Laato & De Moore 2003:viii, xxi). In a strictly monotheistic religion, only one god can be blamed and this often creates cognitive dissonance in believers' minds: Is God benevolent or malevolent? During the last years of the First Temple period and the early years of the Babylonian exile (586-539 BCE), many Judeans struggled to cope with the tumultuous events, which impacted on their religious beliefs.

In the century preceding the Babylonian exile (586-539 BCE), Kings Hezekiah and Josiah of Judah launched religious reforms. Hezekiah's reform was based on the Book of the Covenant (Ex 20:33-23:19), but "[t]his first monolatric reform was not very successful, since Hezekiah's revolt against the Assyrians failed in 701 BCE" (Albertz 2009:383). King Josiah's reform, although apparently more successful, also failed. It was prompted by the discovery of a scroll in the Temple during renovations (2 Ki 22:3-17). Scholars are of the opinion that this scroll was a copy of the Deuteronomic law code (Deut 12-26) or at least the kernel of the code (Nicholson 2002:15-17). Those who discovered the scroll were of the opinion that, if the Judeans were to worship only Yahweh, he could save them from the onslaught of the Babylonian forces. One could thus argue that, during the seventh century BCE, Israel's official religion changed from being polytheistic into one that can be classified as monolatric or henotheistic. Although the existence of other gods was acknowledged, only one was regarded as worthy of being worshipped (Becking 2001:192). Jahwism thus entered a transitional phase. The four-tiered pantheon remained intact but the Judeans were encouraged not to worship other gods.8

The Babylonian Exile (586-539 BCE)

The Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple in 586 BCE had an enormous impact on the Judean belief system. Their symbolic world suddenly collapsed. They had believed that Yahweh would protect them from the onslaught of the Babylonian army, as he had protected them during the reign of King Hezekiah (2 Ki 18-19). This did not happen, and they could not believe it when the forces of king Nebuchadnezzar conquered Jerusalem and demolished the temple.9 The Judeans who survived the attack struggled to come to terms with the events. The Book of Lamentations reflects something of their trauma (Renkema 2003). The closing verses of the book are most revealing:

Why dost thou forget us forever

why dost thou so long forsake us?

Turn us to thee, O LORD,

and we shall be turned;

renew our days as of old:

unless thou hast utterly rejected us;

and art exceedingly angry against us (Lam 5:20-22).10

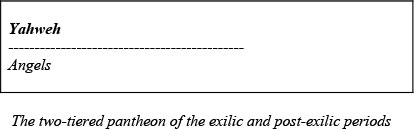

Various prophets and scribes tried to make sense of the events. Among them were the so-called Deuteronomists, a group of scribes who stood behind King Josiah's Deuteronomic Reformation. According to their interpretation, Yahweh was punishing the Judeans for breaking the stipulations of the covenant he had made with them when he promised to be their god and to bless them. The first stipulation stated explicitly that they should serve only Yahweh (Deut 5:6-7). The Deuteronomists compiled a history reflecting their perspective: the Deuteronomistic History (Joshua through Kings). According to their interpretation of the history, time and again the Israelites turned their backs on Yahweh and worshipped other gods. However, what became evident to scholars is that the Deuteronomists read their perspective into the earlier history of Israel, creating the impression that Israel's religion was monotheistic from the start.11 A critical study of the Old Testament books and archaeological excavations in Israel revealed that Jahwism was not monotheistic from the start (Smith 2004; Dijkstra 2001:17-44). In a sense, the Deuteronomists imposed a two-tiered pantheon onto the history of Israel, creating the impression in their rendering of the history that the ancestors of Israel were true monotheists. One may also argue that the four-tiered pantheon of the First Temple period "imploded" during the exile and what remained was a two-tiered pantheon consisting of only Yahweh and the angels (Smith 2004:114-119).

The exilic and post-exilic Jahwistic pantheon can be presented as follows (cf. Handy 1995:42; Smith 2004:119):

Nowhere else is the new pantheon as vividly presented as in Deutero-Isaiah (Is 40-55), the prophet who lived in Babylon among the exiled Judeans. In his message, he emphasises that Yahweh is the creator god and that he is responsible for everything that is happening in the world (Is 45:1-8). All the other so-called gods are non-entities created by humans without the power to control historical events (Is 41:6-7; 44:6-20; 46:1-13). Israel's religion was now on its way to becoming an exclusivist monotheistic religion. Yahweh is held responsible for everything that transpires in the world, be it good or bad. The following quotation from Deutero-Isaiah reflects this well (Is 45:5-7):

I am the LORD, and there is none else,

there is no God besides me:

I gird thee, though thou hast not known me:

that they may know from the rising of the sun, and from the

west,

that there is none beside me.

I am the LORD, and there is none else,

I form the light, and create the darkness:

I make peace, and create evil: I, the LORD, do all these things.12

It was only during the closing decades of the pre-exilic period and during the exilic period that Israel's polytheistic religion mutated into a monotheistic religion. Geza Vermes formulates this as follows (2013: xv):

It was only under the influence of the prophets of the exilic and post-exilic period in the sixth century BC that proper monotheism, the idea of a single God responsible for the creation of the world and mankind, entered Jewish consciousness ...

It should be evident by now that the idea of an opposing force existing along with Yahweh did not play any role during the First Temple and the Exilic periods in the history of Israel (950-539 BCE). However, the periods following the exile brought about major changes.

The Second Temple period (539 BCE - 70 CE)

- The Persian period (539-333 BCE)

When the Persians succeeded in conquering the Babylonian empire in 539 BCE, they allowed the exiled Judeans to return home (Gerstenberger 2005:13-35). The area of Palestine where they settled gained the name Jehud. Not all Judeans accepted the offer to relocate. However, those who returned to Jehud brought with them a new understanding of who Yahweh was and how he should be worshipped. The Persians also allowed the Jews to build a new temple in Jerusalem and to practise their religion according to their traditions, as long as they remained loyal subjects of the Persian kings. This temple was completed in 520 BCE. The exclusivist monotheism promoted by Deutero-Isaiah during the Babylonian exile was now established in the Persian province of Jehud. Circumcision, the celebration of the Sabbath and dietary laws, which became the identity markers of the Judeans in Babylon, were also introduced into Jehud. The pre-exilic religion of Israel, which scholars label Jahwism, became early Judaism during the early years of resettlement (Gerstenberger 2005:353-360). This is the religion practised by the Jews during the Persian, the Hellenistic and the Roman periods. For more than six centuries (539 BCE-70 CE) the Jews were sincere monotheists.13

One of the problems a monotheistic religion creates for its adherents is how to explain disasters, droughts, illnesses, and all other types of calamities and hardships. If there is only one God, and if he is responsible for everything that happens in the world, then he stands behind evil as well (Noort 1984). But believers found this conviction rather difficult to accept. Questions like: How could a benevolent God be responsible for evil? arose and different types of theodicies were developed to exonerate God from such acts. I have already referred to 2 Samuel 24, which narrates the same events as those in 1 Chronicles 21 (footnote 4). The author of 1 Chronicles introduced the character Satan since he could not believe that Yahweh would have prompted David to call a census and then punish him and his subjects. A second type of theodicy developed, which was the belief that there were forces in the cosmos which opposed God, preventing him from executing his good plans for the world and for humankind. The Book of Job reflects something of this development. Although the author did not introduce an evil force opposing God, he was of the opinion that one of the angels could play a rather malevolent role in accusing human beings of not serving God in all honesty. It was possible that human beings served God only because it benefitted them. The main character in the Book of Job is presented as an exceptionally wealthy man and a devoted and upright worshipper of Yahweh (Job 1:1-5). However, the Satan (a heavenly being) was of the opinion that Job paid mere lip service to God. If God were to take away all Job's possessions he would turn his back on God (Job 1:6-11). Yahweh then gave the Satan permission to test Job and to rob him of all his possessions. The outcome of the first test was negative, which astonished the Satan. Job remained loyal to God despite all the calamities which befell him (Job 1:1:20-22). He then challenged God a second time. He reasoned that if God allowed him (the Satan) to deliver blows to Job's body then he would definitely turn his back on God (Job 2:1-6). Yahweh again gave the Satan permission to do whatever he liked to his loyal servant Job - except kill him. Job eventually passed the second test as well. He remained loyal and refrained from cursing Yahweh (Job 2:9-10) (Illman 2003).

In one sense, the author of the book argued the case that Yahweh was not responsible for the evil, calamities and hardships that humans experience, but that there might be heavenly beings behind the scene who were responsible. According to this reasoning, Yahweh is exonerated and was not to be held responsible for evil. The Satan who stood behind the evil events in the book of Job was not yet Satan as he came to be known in later years.

The Book of Jonah, which, like the Book of Job, originated in the Persian period, may also be classified as a theodicy. Yahweh commissioned the prophet Jonah to go and preach to the people of Nineveh and tell them that Yahweh was going to destroy the city and its inhabitants because of their evil deeds (Jonah 1:1-2). Jonah initially tried to escape the command and fled to Tarshish. However, after an ordeal at sea he eventually went to Nineveh and delivered the message (Jonah 3:1-4). When the city and all its inhabitants repented, Yahweh forgave them and decided not to destroy the city. This disturbed Jonah, and the book closes with a dialogue between Yahweh and Jonah in which it transpires that Yahweh cares for the Israelites as well as for the whole world (Jonah 4:1-11). No heavenly being is involved in the drama and Yahweh is characterised as extremely benevolent (Jonah 4:10-11), as he is not inclined to take pleasure in death and destruction. It is as if the author of the Book of Jonah wanted to dissociate Yahweh from evil.

- The Hellenistic period (333-63 BCE)

The Persian period in Jewish history (539-333 BCE) was one of the most peaceful they ever experienced. As Horsley (2011:65) points out, "The Persian takeover of the Middle East had not involved a destructive conquest of Judea". However, with the arrival of Alexander the Great and his armies (333 BCE), this changed. In the space of a decade he had conquered the Persian Empire and, for the first time in history, a Western Empire had taken control of the Near East. The Jews, like all other Near Eastern nations, became subjects of the Greek-Macedonian Empire and its subsequent mini-empires. The empire was divided among his generals after Alexander's death in 323 BCE. Two of these mini-empires impacted on the history of the Jews: The Seleucid kingdom in the north and the Ptolemaic kingdom in the south. The Jews were once again trapped between two political forces (Haag 2003:33-62). Although things did not change drastically during the first century following Alexander's conquest, the Jews realised that their hopes of becoming independent had been dashed. Along with this realisation came the vexing question of whether evil forces did exist and whether they were able to prevent Yahweh from establishing his kingdom.

The Book of Daniel reflects a further stage in the development of ideas concerning evil forces at work in the cosmos. The book originated during the Hellenistic period, not during the exilic period, as some conservative scholars still believe. This becomes evident when one studies the second section of the book (Dan 7-12) critically and attentively.

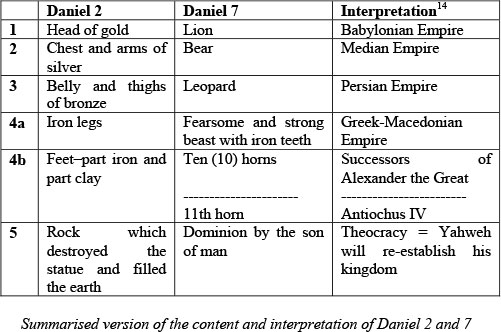

The first section of the Book of Daniel (Dan 1-6) reflects a reworking by an apocalyptic author who wrote the stories about Daniel and his visions (Dan 7-12). He believed, as many other apocalyptic authors did, that world history could be divided into four eras, to which specific empires were assigned. This can be gleaned from the dream of king Nebuchadnezzar (Dan 2) and Daniel's own vision (Dan 7). The different empires/kingdoms mentioned in the two chapters can be presented as follows (Koch 1980:182-213; Koch 1997:11-29):

The author of the book was more concerned with the fourth empire (4a; 4b of the table) than with the first three. This is because the fourth kingdom represents Alexander the Great and his successors. Moreover, the eleventh horn represents Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), who profaned the Jerusalem temple in 167 BCE (Portier-Young 2011:176-185). The other acts contributed to the outbreak of the Maccabean War, a war of liberation in which the Jews tried to regain independence. The author of the Book of Daniel lived during these years and cherished the hope that the Jews would once again establish a theocracy (Beattie 1988:82-83). This is reflected in the vision of the rock that rolled downhill and destroyed the statue (Dan 2) and in the vision of the son of man (a human being) who would rule (Dan 7).

Readers of the Book of Daniel come across the names of angels for the first time in the Old Testament. The angels Gabriel and Michael are mentioned in Daniel 9:21, 10:21 and 12:1. Moreover, readers will discover that the author was convinced that specific angels were to be associated with specific nations (Dan 10). The author of Daniel shared the conviction that some angels could misbehave and cause havoc on earth. The nameless angel who is linked to the Greek-Macedonian empire (Dan 10:20-21) was surely not pro-Jewish, and did not act in their interest. Other extra-biblical literature mentions even more angels by name. On this point, John Collins (1999:339) writes:

The names of angels proliferated in the Hellenistic period. The names themselves, however, are typically archaic theophoric names, ending with the name of the Canaanite god El, who was, of course, identified with Yahweh in the Hebrew Bible. There is no evidence, however, that these names are in fact older than the Hellenistic period.

One may thus conclude that the identification and naming of angels during the Hellenistic period made it easier for Jewish believers to come to terms with the events in the world and with the suffering they were experiencing. They assumed that these angels influenced world events.

As time passed, more and more stories circulated to explain the origin of demons, the Devil and their actions. Greg Riley (1999) identifies three major stories.15 The first is a story of how the sons of God had illegitimate intercourse with young girls (the daughters of human beings). They conceived and gave birth to giants who drowned during Noah's flood (1 Enoch 6-16; Gen 6:6-6; Jude 6; 2 Pet 2:4). Their disembodied souls eventually became demons. The leader of the demons, whose name was Asazel, was none other than the Devil (Jub 10:1-11). He was also called Baalzebub, the prince of the demons, and had once been the prime angel in heaven (Riley 1999:246). A second story is linked to the creation of Adam. When God commanded the angels to pay homage to Adam (since he had been created in God's image) one angel rebelled and refused to do so. He motivated his act by arguing that he had existed long before Adam, who should rather pay homage to him. Other angels joined in the rebellion and the rebellious angels under the command of the Devil were then expelled from heaven. This story is narrated in the book The Life of Adam and Eve (Chapters 13-15) (Riley 1995:246). A third story was inspired by two sections from prophetic books: Isaiah 14:4-20 and Ezekiel 28:11-19. These chapters concern the King of Babylon and the King of Tyrus respectively. However, the prophecies served as base texts for a story about the origin of the Devil: On the second day of creation, one of the archangels (the most important one) wanted to be treated equally with God and commanded the other angels to worship him in a similar way (2 Enoch 29:4-5, cf. 1 Jhn 3:8). This angel, along with those who worshipped him, were expelled from heaven. Later on he received the name Lucifer, the Latin translation of the Hebrew word for "morning star" used in Isaiah 14:12 (Riley 1995:246).

- The early Roman period (63 BCE-70 CE)

When the Romans conquered the Seleucid kingdom in 63 BCE, and Palestine became de facto part of their empire, the conviction that the Devil and his angels/demons were expelled from heaven and were creating havoc on earth was well-established among Jews. Some Jews believed that there were evil forces behind the Roman Empire, as had been the case with the Seleucids during the time of Daniel. "Explaining imperial violence as the result of rebel heavenly forces enabled them not simply to blame themselves as hopeless sinners" (Horsley 2011:71). However, the different factions and groups constituting early Judaism commenced with the practice of demonising others in order to present themselves as the only group of true believers. With this, we reach another stage in the development of the belief in the Satan/Devil. The Qumran community may serve as an example. Severing their ties with the rest of the Jewish community they proclaimed that they represented "true Israel". The others, they claimed, were colluding with the Devil and his entourage (Pagels 1996:56-61).

Looking at Jesus' message and acts as presented in the synoptic Gospels, it is evident that he did not share the Qumranites' opinion. Jesus was convinced that evil forces stood behind the Roman Empire and that he had the task of proclaiming the good news that Yahweh would soon establish his kingdom in Palestine (Mark 1:14-15). His exorcisms and healing of the sick should be understood as integral to his conviction that evil forces were at work in the world and that they were hampering the coming of God's kingdom: "Once the spiritual power behind Rome was bound, God's peacable kingdom would become a reality" (Le Donne 2011:89). Later Christians misunderstood Jesus' message and acts. The good news that main-line churches since the time of Augustine have proclaimed focuses on believers' spiritual life and not on the good news as Jesus understood it.16 Anthony le Donne convincingly argues that the historical Jesus' message had to do with political liberation:

Jesus was a prophetic voice for reform and political restoration in a time when the common sentiment was for violent uprising. Like Moses, Jesus aimed to liberate his people from oppression. But unlike Moses, Jesus' fight wasn't with the "Evil Emperor" but with the hand that moved the political puppets (Le Donne 2011:133).

Concluding remarks

The brief history of the development of the belief in the Devil and fallen angels presented here should serve as proof that this belief cannot be classified as a pure "biblical belief". In one sense, it could even be argued that "[d]evils, hell and the end of the world are New Testament rather than Old Testament realities" (Barr 1966:149). It is only during the Second Temple period (more specifically the Hellenistic period) that belief in Satan and the fallen angels developed. The events on the political scene contributed to this development. Furthermore, the historical overview may serve as an argument to counter the claim that belief in the Devil is a prerequisite for being a Christian. Jesus shared the convictions of his contemporaries that evil forces were behind the Roman Empire, but we do not have to make similar claims. Christians could, in fact, do without this character. To discard the belief in the Devil may even contribute to peace-initiatives on earth. Christians and Muslims too easily claim to be on the side of the good and point fingers at others as being on the side of evil and the Devil. Concerning this, Messadie makes the following observation:

In the mid-eighties, the world saw an odd and symbolic case of geographical transference. The president of the United States, Ronald Reagan, called the USSR "the Evil Empire" while the de facto leader of Iran, the Ayatollah Khomeini, called the United States "the Great Satan." Both flights of rhetoric indicate that hell, the kingdom of the Devil, doesn't appear to be situated in the same place for everybody - and that the Devil is a political useful figure (Messadié 1996:3).

Monotheistic religions need not be violent, as Rainer Albertz argues (2011), but monotheistic religions do become dangerous when their adherents cherish beliefs about the existence of a Devil and demons and start labelling others as being "children of the Devil".

Works consulted

Albertz, Rainer 2009. Monotheism and violence: How to handle a dangerous biblical tradition, in Van Ruiten, J. & De Vos, J.C. (ed.), The land of Israel in Bible, history, and theology. Leiden: Brill, 373-387. [ Links ]

Albertz, Rainer 2011. Does an exclusive veneration of God necessarily have to be violent? Israel's stony way to monotheism and some theological consequences, in Becking, B. (ed.), Orthodoxy, liberalism, and adaptation: essays on ways of worldmaking in times of change from biblical, historical and systematic perspectives. Leiden: Brill, 35-51. [ Links ]

Barr, James 1966. Old and New in interpretation: a study of the two testaments. London: SCM. [ Links ]

Beattie, D.R.G. 1988. First steps in biblical criticism. (Studies in Judaism). New York: University Press of America. [ Links ]

Becking, Bob 2001. Only One God: On possible implications for biblical theology, in Becking, B., Dijkstra, M., Korpel, MCA. & Vriezen, KJH., Only One God? Monotheism in ancient Israel and the veneration of the goddess Asherah. (The Biblical Seminar 77.) London: Sheffield Academic Press, 189-201. [ Links ]

Becking, Bob, Dijkstra, Meindert, Korpel, Marjo C.A. & Vriezen, Karel J.H. 2001. Only One God? Monotheism in ancient Israel and the veneration of the goddess Asherah. (The Biblical Seminar 77.) London: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Collins, John J 1999. Gabriel, in Van der Toorn, K., Becking, B. & Van der Horst, P.W. (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Leiden: Brill, 338-339. [ Links ]

Corte, N 1958. Who is the Devil? (Faith and Fact Books, 21.) London, Burns & Oates. [ Links ]

Den Heyer, Cees J. 1998 Jesus and the Doctrine of the Atonement: Biblical notes on a controversial topic. London: SCM. [ Links ]

Dijkstra, Meindert 2001. I have blessed you by YHWH of Samaria and his Asherah: Texts with religious elements from the soil archive of ancient Israel, in Becking, B., Dijkstra, M., Korpel, MCA. & Vriezen, KJH., Only One God? Monotheism in ancient Israel and the veneration of the goddess Asherah. (The Biblical Seminar 77.) London: Sheffield Academic Press, 17-44. [ Links ]

Dijkstra, Meindert 2001. El, the God of Israel - Israel, the people of YHWH: On the origins of ancient Israelite Yahwism, in Becking, B., Dijkstra, M., Korpel, MCA. & Vriezen, KJH., Only One God? Monotheism in ancient Israel and the veneration of the goddess Asherah. (The Biblical Seminar 77.) London: Sheffield Academic Press, 81-126. [ Links ]

Edelman, Diana V. (ed.) 1995. The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. (Contributions to Biblical Exegesis & Theology, 13). Kampen: Kok Pharos. [ Links ]

Gerstenberger, Erhard S. 2005. Israel in der Perserzeit: 5. und 4. Jahr-hundert v. Chr. (Biblische Enzyklopadie 8.) Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Haag, Ernst 2003. Das hellenistische Zeitalter: Israel und die Bibel im 4. bis 1 Jahrhundert v. Chr. (Biblische Enzyklopadie 9.) Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Handy, Lowell K. 1995. The appearance of Pantheon in Judah, in Edelman, Diana V. (ed.), The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. (Contributions to Biblical Exegesis & Theology, 13). Kampen: Kok Pharos, 27-43. [ Links ]

Hess, Richard S 2007. Israelite religions: an archaeological and biblical survey. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Horsley, Richard A 1993. The Liberation of Christmas: The infancy narratives in social context. New York: Continuum. [ Links ]

Horsley, Richard A. 2011. Jesus and the Powers: Conflict, covenant, and the hope of the poor. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

Illman, Karl-Johan 2003. Theodicy in Job, in Laato, Antti & De Moore, Johannes (ed.), Theodicy in the World of the Bible. Leiden: Brill, 305-333. [ Links ]

Koch, Klaus 1980. Das Buch Daniel. (Ertrage der Forschung, 144.) Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. [ Links ]

Koch, Klaus 1997. Europa, Rom und der Kaiser vor dem Hintergrund von zwei Jahrtausenden Rezeption des Buches Daniel. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Laato, Antti & De Moore, Johannes (ed.) 2003. Theodicy in the World of the Bible. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

Laato, Antti & De Moor, Johannes 2003. Introduction, in Laato, Antti & De Moore, Johannes (ed.), Theodicy in the World of the Bible. Leiden: Brill, vii-liv. [ Links ]

Le Donne, Anthony 2011. Historical Jesus: What can we know and how can we know it? Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Loader, James (Jimmie) A. 1984. Liefs na die duiwel met ou Niek! Beeld 4 Desember, 12. [ Links ]

Messadie, G. 1996. A history of the Devil. New York: Kodansha International. [ Links ]

Muchembled, R. 2003. A history of the Devil: from the Middle Ages to the present. Cambridge: Polity. [ Links ]

Nicholson, Ernest 2002. The Pentateuch in the twentieth century: the legacy of Julius Wellhausen. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Niehr, Herbert 1995. The rise of YHWH in Judahite and Israelite religion: Methodological and religio-historical aspects, in Edelman, Diana V. (ed.), The Triumph of Elohim: From Yahwisms to Judaisms. (Contributions to Biblical Exegesis & Theology, 13). Kampen: Kok Pharos, 45-72. [ Links ]

Noort, Ed 1984. JHWH und das Bose. Bemerkungen zu einer Verhaltnisbe-stimmung, in Prophets, Worship and Theodicy (Oudtestamentische Studiën 23). Leiden: Brill, 120-136. [ Links ]

Oldridge, Darren 2012. The Devil: Very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pagels, Elaine 1996. The origin of Satan: How Christians demonized Jews, pagans, and heretics. New York: Vintage Books. [ Links ]

Portier-Young, Anathea E. 2011. Apocalypse against Empire: Theologies of resistance in early Judaism. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Renkema, Johan 2003. Theodicy in Lamentations? in Laato, Antti & De Moore, Johannes (ed.), Theodicy in the World of the Bible. Leiden: Brill, 410-428. [ Links ]

Riley, Greg J. 1999. Devil, in Van der Toorn, K., Becking, B. & Van der Horst, P.W. (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Leiden: Brill, 244-249. [ Links ]

Smith, Mark S. 2004. The Memoirs of God: History, memory and the experience of the divine in ancient Israel. Minneapolis: Fortress. [ Links ]

The Holy Scriptures 2000. Jerusalem: Koren Publishers. [ Links ]

Theissen, Gerd 2011. Monotheismus und Teufelsglaube: Entstehung und Psychologie des biblischen Satansmythos, in Vos, Nienke & Otten, Willemien (ed.), Demons and the Devil in Ancient and Medieval Christianity. Leiden: Brill, 37-69. [ Links ]

The Revised English Bible 1989. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Vermes, Geza 2013. Christian Beginnings: From Nazareth to Nicaea. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

1 I dedicate this article to Cornel du Toit in celebration of his 65th birthday. He has served the theological fraternity at Unisa with distinction during his tenure as director of the Research Institute for Theology and Religion. We all benefitted from the annual seminars which he and his team at the RITR organised.

2 His article caused a furore. Afrikaans speakers from the Reformed tradition flooded the editor with letters criticizing Loader's viewpoint.

3 Gerd Theissen recently published an article on monotheism and belief in the Devil (2011). However, he is a New Testament scholar and his presentation does not engage the latest research into the religion of Israel.

4 It is important to note that 2 Samuel 24 narrates the same events found in 1 Chronicles 21. However, 2 Samuel 24, which is the older of the two narratives, does not mention Satan. Scholars are of the opinion that the author of 1 Chronicles introduced the character because he could not believe that Yahweh would have prompted David to call a census and then punish him and his subjects (Theissen 2011:42).

5 The Revised English Bible (1989).

6 The Revised English Bible (1989).

7 The Revised English Bible (1989).

8 Rainer Albertz differs from his younger colleagues. He still adheres to the view that the religion of Israel was monotheistic from the start, and says: "As well founded as the new position seems to be, it hides a problem. If Israel's religion originally was polytheistic like any other, the question arises: why in only this particular polytheistic religion did a monotheistic development occur at all?" (Albertz 2011:37-38). According to him there was a "polytheistic extension" during the establishment of the Israelite kingship during David and Solomon's time and a "re-education" or a re-introduction of monotheism during the reforms of Hezekiah and Josiah.

9 One needs no better explanation for the Judeans' willingness to discard other gods than Jeremiah's message of doom, the traumatic experience of the conquest of Jerusalem and the demolition of the temple. In my opinion Rainer Albertz (2009; 2011) ignored all this.

10 The Holy Scriptures (2000).

11 Meindert Dijkstra says: "Israel's exclusive monotheism as it finally took shape after the Babylonian Captivity was projected back into the life of Moses and the people of Israel as norm and rule" (2001:81).

12The Holy Scriptures (2000).

13 The word "Jew" refers to the people who lived in the Persian province of Jehud and in the rest of the Persian Empire. Jehud covered a small section of the erstwhile Southern Kingdom (also known as Judah).

14 Christians through the centuries have adhered to the interpretation that identified the fourth empire with Rome (Koch 1997). According to them, the first empire was the Assyrian-Babylonian, the second the Median-Persian, the third the Greek-Macedonian, and the fourth the Roman Empire. The fifth empire has then been linked to the second coming of Christ and the establishment of the eternal kingdom of God. Critical study of the Book of Daniel during the nineteenth century led to the abandonment of this interpretation and to the re-introduction of the Maccabean hypothesis which the philosopher Porphyry (232-304) promoted in the third century CE (Koch 1980:8-12).

15 Elaine Pagels shares similar views (1996:47-49).

16 Richard Horsley (1993:9) comments as follows: "Christ may now be born in our hearts, but little attention is given to the implications of Jesus having been born historically."