Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versão On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versão impressa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.39 no.2 Pretoria Fev. 2013

HISTORIES OF THE IMPACT OF CHRISTIANITY

The role played by Church and State in the democratisation process in Mozambique, 1975-2004

Júlio André Vilanculos

Department of Church History and Church Polity, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The political action of citizens individually or collectively is always determined by a multiplicity of factors. These are first, political socialisation; second, the logic of the dominant political culture in the society; third, factors of an ideological nature; and fourth, religious factors. In the particular case of Mozambique it can be seen that from independence in 1975, the political and religious dimensions went through several changes. In the political area, the changes were observed more profoundly after the independence of the country under the orientation of FRELIMO, the political party in power. From that moment until 1990, the country was governed by the domination of one political party under a Marxist system of socialism. In the religious arena, the domination of the Roman Catholic Church was observed prior to independence since it was working together with the dominators (Portuguese), and other Christian religions were persecuted by this church. However, after independence another dimension became a changing force within the country. First of all, the relationship between FRELIMO and the church was poor. Second, from 1982 the relationship started to take on a more positive nature. The questions that then arose were the following: What are the factors that might have contributed to this changed situation? How can this dimension be explained? What are the implications of these changes?

Introduction

This article seeks to discuss the role played by the church and the state in the democratisation process of Mozambique and the role of external powers in bringing an end to civil war. It starts by exploring the general background of Mozambique where issues such as liberation, civil wars and eventually peace negotiations are discussed. It also discusses the church and state relationship highlighting the contribution from the Protestant churches towards Mozambican independence. It then discusses and explains the reasons why the church should be participating in political issues in order to build a good and decent democracy for all the people in Mozambique. Thereafter, it demonstrates and looks at some of the activities undertaken by different churches who have sought collaboration with civil society and political authorities for the edification of peace, democracy. It also deals with some issues, both positive and negative, regarding the elections that have occurred in Mozambique.

The Mozambican background

Portuguese domination

The history of Mozambique1 did not begin from the time of Portuguese domination. Different empires dominated Mozambique long before the Portuguese arrived in the country. Many attractive resources were found in the whole Indian Ocean litoral and in the rivers that meander through the country with the Zambezi River being one of great importance.2 These natural resources (rivers and the flat litoral) facilitated straightforward penetration into different communities along these rivers and the seashore.

The first contact for the Portuguese with Mozambique was on 10 January 1498 when Vasco da Gama passed through Inhambane.3 Da Gama's ships anchored in Mozambique Island in the North of Mozambique on his way to India. In Inhambane, because of the good hospitality that Da Gama and his team received, they called that place Terra da boa Gente - land of good people. As a result of that warm reception, Vasco da Gama offered the traditional chief of Inhambane four objects - a jacket, red trousers, a cap and a drain-pipe.4 There is no doubt that on these two stops, one in Inhambane and another in Nampula, Da Gama and his vessels were more interested in exploring the diversity of the products from the Indian Ocean (including fish and prawns) and the fertile land for agriculture as well as the natural resources. In addition, the Portuguese were astonished at the stone buildings and the atmosphere of prosperity.5 In the opinion of the researcher, this situation motivated the Portuguese to think of applicable modalities to explore the richness of Mozambique, not only that, but to Christianise the people of the country. In order to fulfil their intent, they started by fighting the Arabs (who were Muslims) that had already settled in the country. From the above situation, it can be seen that when the Portuguese came to Africa (and Mozambique in particular) they were interested in commerce, evangelisation and a crusade against Muslims. It was because of these projects that in the 1530s more Portuguese penetrated into the interior of Mozambique to places such as Sena, Tete, Luabo and Quelimane.6

One of the major strategies that accelerated the domination of the Portuguese over Mozambicans was the introduction of Prazos.7 The project of Prazos began in the 17th century when the Portuguese started sending settlers to occupy the country with the objective of turning the occupied land into their own property. As argued by Henriksen, "the prazo masters relied on Africans for defence, trade, food and women. Using African techniques as well as labour in mining gold, hunting elephants, raising food and building houses and forts, they gradually became Africanised".8 According to Eduardo Mondlane, three major techniques were applied by the Portuguese for controlling these territories. First, Portuguese business people were sent to Mozambique on the pretext that they were only coming for commercial purposes, but later on the Portuguese then sent troops to eliminate any kind of resistance from local chiefs. Second, the Portuguese came to Mozambique and requested land for agricultural purposes, but later on they claimed that the land was theirs. Third, the Portuguese missionaries came as peacemakers and were involved in evangelisation, which was used to mislead Africans while the Portuguese troops were occupying and controlling the Mozambican land.9 It was from this last technique the following saying originated: "When white people came to our continent they had the Bible and we 'blacks' (indigenous) had the land. They said 'let us pray' and we closed our eyes to pray. At the end of the prayer 'whites' had the land and Africans had the Bible."10

Portuguese missionary work in Mozambique

The arrival of Vasco da Gama in Mozambique in 1498 marked the first missionary contact with the inhabitants, because he came with some Dominicans, Augustinians and Jesuits who gave spiritual guidance to the soldiers and seamen who were part of his force.11 Evangelisation gained momentum between 1514 and 1612 when the first missionary team came to Mozambique from Goa (India) and it was made up of the following priests: Gonçalves da Silveira, André Fernandes and Brother Fernando André da Costa who came to Inhambane.12 Unfortunately, this first stage of evangelisation was unsuccessful and this situation prompted a furious Portuguese scholar named A da Silva Rego to write the following statement: "[T]he virgin forest was not ready yet for the people to peacefully accept the Gospel ... because it is dominated by the absolutism of chiefs and the interest of the blacks (indigenous)."13 After this failure in Inhambane, the Portuguese missionaries decided to penetrate into the interior of the country and in Sena-Sofala Province about five hundred people were baptised.14 The second missionary expedition in Mozambique began in January 1612 after the papal bull was issued by Pope Paulo V, who elevated Mozambique to a "Prelature Nullius".15 This period is considered to be the time when some people in Mozambique started welcoming the Portuguese missionaries because some of the chiefs, related to Monomotapa, went to Dominican seminaries in Goa to be trained as priests. Consequently, as we can see, there were three orders of missionaries in Mozambique - Dominicans, Augustinians and Jesuits- who later on changed their evangelistic motifs and became more interested in trade, particularly gold, ivory and slaves. This situation created a crisis between the Portuguese state and the Roman Catholic Church and it culminated in the chasing away of Portuguese missionaries from Mozambique and the three orders were abolished and only four priests from Goa were left in Mutarara-Tete.16 Despite the problems between the Portuguese government and the Roman Catholic Church, missionaries continued coming to Mozambique with their campaign of evangelisation. According to Ferreira, 1940 became a very significant year, because the Roman Catholic Church began to implement a systematic plan of evangelisation in Mozambique. As a result, three dioceses were founded in the country, : Maputo, Beira and Nampula. Later on, the dioceses of Pemba, Lichinga, Inhambane, Xai-Xai, Tete and Quelimane were also created.17

Critical examination of Portuguese domination

It is true that the majority of Mozambicans have the idea that the Portuguese colonised some countries in Africa in general and Mozambique in particular. Hence, the majority argue that there is no need to explain what positive effects they may have effected for colonised countries. However, the Portuguese presence in Mozambique had both negative and positive impacts. In this manner, it is significant to appreciate the positive things that the Portuguese did because the positive works outweigh the negative. The impact of Portuguese domination in Mozambique can be understood as threefold: social, political and economic, and were both negative and positive. Negatively, the major objective for the Portuguese who came to Africa was to civilise Africans and they wanted them to accept everything they were doing on the continent. In fact, the Portuguese were the source of the exploitation and oppression of Mozambicans and they are the ones to blame for the poverty in Mozambique and other African countries which were colonised by them. Colonial education was the main channel used to exploit the Mozambicans mentally. At worst, education was not available to everybody but only to a few and the majority remained illiterate. The fact is that the few people who were accepted had the status of assimilado.18 With this principle, Mozambicans were taught to look down upon their own culture which was considered to be backward, uncouth, barbaric and heathen. Even the very few educated people had to learn Portuguese as a means of alienating them from their own language and culture. The problem of alienating people from their own language is still perpetuated in Mozambique today as there are still people in the country who cannot speak their own local language because they were not taught by their parents. This affirms that it is a language for old people (this is a sad reality that is experienced nationally) and it retards the minds of the speakers. This situation was motivated by the policy that was adopted by FRELIMO soon after independence in 1975. Since this new party wanted to eliminate tribal diversity, this meant eradicating local languages and adopting Portuguese as the language of unity for the entire country. However, it is recognised that during the time of Portuguese domination in Mozambique, girls were neglected by being barred from education and other facilities. As a consequence, until the present, girls from Mozambican rural areas do not go to school, allegedly because there is no need to avail them of an education because they are only waiting to get married. The Portuguese were of the view that the majority of girls only needed to learn how to take care of their husbands and children. It was from this context that some years ago the Mozambican government made a decision to promote education for girls, arguing that the percentage of boys enrolled in schools has to be at least the same as that of girls or the ratio of the enrolled girls has to be higher than that of boys.

In the social arena, the impact of Portuguese was felt in intermarriage with Mozambican women, thus creating from the children of these marriages a class of Afro-Portuguese where some of them did not even have a chance to know their fathers. In addition to that, Portuguese colonisation brought chaos within Mozambique because of the issue of the slave trade which had a negative impact on the families and nation. Treaties for contract labour with South Africa and Southern Rhodesia were introduced by the Portuguese and this had a social influence; for instance, Mozambique lost thousands of people from the rural areas, thus creating serious social demographic imbalances.19 Some of these people were taken to work in the gold mines of South Africa, while others were taken to work on the farms and mines in Southern Rhodesia as well as in the construction and maintenance of the railways connecting Mozambique, Southern Rhodesia and South Africa. In addition to that, many Mozambicans were sold as slaves to some western countries like North America, Brazil, France and Spain;20 many people died or were killed while on the ships and others were thrown alive into the ocean if they complained of being sick. This situation contributed significantly to the depopulation of the nation and the immediate effect was indeed the loss of the most productive human resource; increasing famine, debt and disease just to mention a few.

In the political arena, the coming of Vasco da Gama to Mozambique opened a way for the coming of Portuguese masses into the country as well as opening a way for the introduction of colonial domination of the land that, according to them, they had discovered. It was with the arrival of the Portuguese that Mozambique and other African states came to be independent. It was the presence of Europeans that caused the boundaries of Africa to be demarcated according to which European countries colonised particular areas.21 Economically, from the time the Portuguese started exporting raw materials found in the country to Portugal in order to be manufactured, they brought back some of the manufactured goods to Mozambique to be sold at exorbitant prices as a way of draining the few economic resources the Mozambicans had.

On the positive side, the presence of the Portuguese in Mozambique was very important because they provided the country with basic infrastructures such as roads, railways, harbours/ports, telephones and airports. In addition, in 1965 the Portuguese discovered a vast deposit of natural gas at Pande in the Inhambane province. Another important project that was started during the colonial era was the Cahora Bassa hydroelectric dam. It was during the same period that most of the mineral potential of Africa was discovered, which required the introduction of a mining system and the Portuguese carried this out very well. During the same period, new cash crops were introduced into Mozambique and other African countries including cotton, peanuts, palm oil, coffee, tobacco, rubber and cocoa.22 The introduction of these crops was very important for the lives of Mozambicans since they were utilising them for their survival. Some areas of Mozambique still have some coconut plantations left by the Portuguese which now have reverted to Mozambicans. Concrete examples are the three coconut plantations that exist in the Massinga District.

Similarly, it was during the same period that hospitals and schools were introduced into the country. As the population grew, the colonisers launched campaigns against some epidemic diseases by providing medical facilities. The same systems were adopted by the Mozambican authorities after the nation attained independence and up to the present day, whenever there is an epidemic, the government has carried out campaigns against the disease by awakening people to the dangers of such diseases. It was through the coming of the Portuguese to Mozambique that urbanisation began. Some towns were expanded, while at the same time new ones were established. The Portuguese presence in Mozambique was very important in the religious area since Christianity had been introduced. It was through Christianity that western education was introduced into the whole country. As a result, primary, secondary and university education appeared for the first time for the nation.23

Protest and the liberation war

The experience of Mozambicans under Portuguese domination was dire. This was characterised by different adjectives like: "indolent, incapable and incompetent".24 This state of affairs infuriated the Mozambicans to such an extent that they felt it necessary to do something in order to change the situation, despite any consequences it may bring to the country. In the beginning, resistance was manifested in different forms, namely: rural protests, the struggle of urban workers, poetry and members of the independent churches who, in the name of God, felt the need to take part in the protests25, since the domination was considered by Christians from those churches as hypocrisy. Henriksen also claimed that Chope26 songs and Makonde27 wood carvings were other forms of protest against colonial oppression in Mozambique. Later on, three movements of resistance (UDENAMO-National Democratic Union of Mozambique, MANU-Mozambican African National Union and UNAMI-National Union for Mozambican Independence) were formed by Mozambicans who had been in exile for several years and far from the Portuguese. 28

Strategies applied and external support

Strategies like petitions, protest letters and nonviolent demonstrations29 were applied in order to curb Portuguese exploitation of Mozambique. The most remembered specific manifestation was that of Makonde members of MANU in Mueda which ended in a disastrous massacre. Moreover, it is of paramount importance to highlight that common people (those who did not know anything about politics) had a strategic role to play, that of transporting material, producing and supplying food for FRELIMO armed forces, providing information and recruits for the struggle. Consequently, "on September 25th 1964, FRELIMO soldiers, with logistical assistance from the surrounding population, attacked the Portuguese administrative post at Chai in Cabo Delegado province".30

Concerning external support for Mozambique, two African leaders deserve special consideration whenever dealing with the liberation war namely, Julius Nyerere and Kwame Nkrumah, the presidents of Tanzania and Ghana respectively who worked tirelessly for the unification of the three movements into one (FRELIMO).31 Other African nations like Egypt, Al geria and Zambia were also FRELIMO partners with the provision of arms and training. Some socialist countries like the United Arab Republic, Soviet Union, Cuba and China were major financial sources for weapons and diplomatic support to FRELIMO.32 Furthermore, some nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), like the American Committee on Africa, the Lutheran World Federation, Oxfam and the World Council of Churches supported the Mozambican struggle with the supply of books, blankets and other supplies for Mozambicans who were in Tanzania.33

Result of the liberation war

The first result of the liberation war was the Lusaka Agreement signed in Lusaka on 7 September 1974 between Mário Soares (the Portuguese Foreign Minister) and Samora Moisés Machel (the president of FRELIMO). The second was that the government and military structures were divided between the Portuguese state and FRELIMO which was called the transitional Government of Mozambique.34 It was installed on 20 September 1974 with the composition of eleven ministers (six appointed by FRELIMO and five by the Portuguese Government). The third and very significant result was the independence achieved on 25 June 1975.

Civil war

Soon after Mozambique attained independence in 1975, a civil war erupted in the country involving FRELIMO and RENAMO. The war was motivated by disagreements between the freedom fighters within FRELIMO's political system of governance. Moreover, the top leadership in the newly formed government was more from the Southern part of Mozambique, and that distorted the primary inception of FRELIMO which fostered nationalism rather than the regionalism that existed before. The Mozambican conflict was characterised by the involvement of both external and internal forces. These two forces were very influential to the starting and development of the civil war in Mozambique. David Hoile stresses one of the major factors for the civil war in the country as "the lack of a proper definition of who the enemy was and what the goals to be achieved were, and the lack of common strategy".35

The civil war had both a negative and positive impact on people's lives. The negative impacts are the following: loss of moral and social values, proliferation of weapons in inappropriate hands being used to perpetrate different kinds of crimes, increased poverty and depopulation of rural areas and at the same time urban areas becoming overpopulated. People who ran away from their homes no longer produced their own food and sometimes the quarrelling sides (RENAMO and FRELIMO) destroyed or grabbed the population's produce. Positively, this act paved the way for the establishment of a multi-party democracy. It also stimulated people's minds to develop a positive outlook with which they can challenge every life situation. Before the civil war in Mozambique, it was the men who were more active in finding solutions to cope with the pressing needs of life. Now women are also involved actively in finding solutions for the common good of the family and society as a whole. For example, before the end of civil war there were very few women who crossed the Mozambican border to South Africa for work, but nowadays there are thousands working in South Africa. Furthermore, it stimulated different organisations to fight poverty and it led churches to have an interest in political issues. Finally, it permitted cultural exchange between people from different areas within the same country.

The General Peace Agreement for Mozambique

The Mozambican peace process involved the intervention of different forces seeking to bring peace, stability and reconciliation to the nation. There were regional, religious organisations (Roman Catholic and the Christian Council of Churches) and international interventions. The intervention of different actors for peace negotiation in Mozambican culminated in the establishment of a document which constituted the General Peace Agreement. This document comprised of seven protocols and this marked the introduction of a multi-party democracy in Mozambique.

Church and state relationship in Mozambique

The history of the relationship between the Roman Catholic Church and other churches or religions (Protestant, Pentecostals, Independents and Muslim) on the one hand, and the relationship between all the churches and state on the other hand, was an experience which had both bitter and positive aspects from 1975 onwards in Mozambique. Rossouw and Macamo Jr stress that, "in the development of modern church-state relations in Mozambique, there are two distinct phases: the first from 1975 to 1982, the second from 1983 to the present".36 In the first phase, the relationship between church and state was extremely tense and unfriendly, while in the second period the relationship between them became more comfortable and friendly.

The relationship between the Roman Catholic Church and Protestant churches

The strategies applied by the Protestant churches (use of local languages, giving importance to the capacity of local people, accepting them in leading positions, acknowledging their skills and the translation of some Bible passages into local languages) contributed significantly to increasing the credibility of these churches in the country even though their counterpart, the Roman Catholic Church, did not appreciate their good work. Consequently, the Roman Catholic Church created barriers preventing the introduction of Protestant churches to Mozambique, arguing that these churches were not supporting the Portuguese colonial presence in the country as well as ensuring that Mozambique remains Catholic.37

The contribution of the Protestant churches towards independence

The contribution of the Protestant churches towards the independence of Mozambique has many different aspects. Primarily, the influence and contribution from these churches was seen through the introduction of mission schools in the 19th century in Inhambane (Cambine Mission), Lourenço Marques (Khovo Lar Secondary School and St Cipriano) and in Gaza (Chicumbane and Maciene Missions). They encouraged literacy amongst the local people. For instance, these churches were the first to start ministering and teaching the population in vernacular languages and culture. They also encouraged Mozambicans to think about their own culture (anthropology), and this was very significant since Mozambicans were rehabilitating their own personality, self-esteem and self-respect as well as their own dignity. Some distinguished figures in the history of FRELIMO were trained in mission schools such as: Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane the first president of Mozambique who was trained first in a Swiss Mission, currently called the Presbyterian Church School in Lourenco Marques - Maputo then he studied agriculture at Cambine Mission. Graca Simbine and Daniel Mbanze were educated at Cambine Mission of Methodist Episcopal Church. Later on, Graca went to Chicuque Mission of the same Church.38 Besides that, different Protestant churches were able to offer scholarships to African students to pursue higher education in Mozambique39 and others were sent overseas. This situation motivated Mozambicans to think deeply about the necessity and importance of independence.

The attitude of FRELIMO government towards the church in Mozambique after independence

Rossouw and Macamo Jr claimed that when the FRELIMO government came into power in 1975, the relationship between church and state in Mozambique seriously deteriorated. The deterioration was caused by the policies of the new state in the light of the difficult life that people experienced in Mozambique, as well as the action and reluctance of the Roman Catholic Church.40 The relationship between church and state can be explained in several ways including the experiences of religion and churches and nationalist ideologies. Regarding the experience of religions, the revenge against the church was of course perpetrated by Mozambican nationalists coming from religious families. However, their experiences with the church were different - some had positive experiences with the church and others negative. Nationalist ideologies also contributed to the attitude of the government towards the church in Mozambique. On this note, Morier-Genoud argues that regarding nationalist ideology two factors have to be considered. First, the conspiracy between the Roman Catholic Church and the Portuguese state was such that when a nationalist rejected colonialism, he or she was influenced to become at least a critic of the Catholic Church, if not of all churches and religion.41 This was the situation in Mozambique. The formation of FRELIMO culminated in the rejection of the principles and values of the dominator. Consequently, the Catholic Church had to be rejected too because there was no way of denying one and accepting the other. Otherwise, all religions were to be subjected to the same conditions. The rejection did not come from nowhere, the nationalists raised several questions about the conditions that were distorted by the coloniser in alliance with the Roman Catholic Church and the issue did not only end with questioning but everything that was not going well was opposed and criticised. This attitude towards the church was adopted because all actions of any Christian denomination were seen as a hindrance to the revolutionary transformation of society.

The rejection of the church and traditional religion in Mozambique had its consequences. Helgesson pointed out as the first consequence the fact that many church buildings were closed by official order allegedly because they were nearby schools and hospitals. Many missionaries, pastors and laity belonging to different Christian denominations were expelled from the country and others were persecuted and sent to detention camps (re-education centres), some were imprisoned or even murdered.42 Cabrita estimates that in the first year of independence about six hundred missionaries left the country because they found it difficult operate under the new conditions.43 In the United Methodist Church, Bishop Ralf Dodge who was considered a revolutionary leader was obliged to return to America his home country because of the persecution he suffered along with other leaders from different Christian denominations. Not only that, Christians were compelled by FRELIMO militants to renounce their faith and religious practices; automatically they had also to reject missionaries and missions too. All church properties were nationalised and Baur makes this issue of nationalisation very clear by saying that all educational and health facilities were nationalised and religious instruction replaced by political indoctrination. Seminaries, novitiates and catechist schools were closed and many missionary residences confiscated and reverted to the party and state institutions including the armed forces.44

It was only in 1982 that it was noticeable that the hostile relationship between the state and church started to change. The first stance taken by the government was to call together different religions operating in the country for a deliberation. It was realised that there was a need for reconciliation and change within the prevailing situation, mainly because the Mozambican government had discovered that the accusations thrown against traditional, Christian religions and Muslims were not true as it is declared by Hall and Young who stressed that:

The government abandoned much of its marxisant truculence towards organised religion in the wake of a meeting with the church leaders in December 1982, where demands were voiced for the restoration of church buildings, and the right to train religious personnel and to import or produce religious material. In 1983, as requested by almost all the religious delegations to the meetings, a Department of Religious Affairs was created in the Ministry of Justice, removing such matters from the hands of militants. Further small symbolic concessions were made such as reinstating Christmas Day as 'Family Day'.45

The reconciliation included the following six factors. First, there was "the vital role that the churches were playing in Mozambican society".46 The second factor was the involvement of different churches in the area of social services.47 Third, the churches could help the government to relieve the economic crisis in the country. Fourth, the government had to improve relations with the church since churches had better infrastructures in the rural areas. The fifth factor was the calamitous situation of the Mozambican economy, and the sixth factor was the war waged by RENAMO against the government. The government had to find ways of resolving these challenges partnering together with churches.

Towards democracy in Mozambique

The word "democracy" comes from the Greek words "demos" meaning "the people" and "kratein" meaning "to rule" and signifies "rule by the people". The origin of democracy comes from Athens and its direct democracy, where all citizens took an active part in decision-making through general assemblies or direct elections".48 Mozambican democracy can be discussed dwelling on the one-party and multi-party regimes of democracy.

One-party regime

The democratic atmosphere of Mozambique can be discussed in terms of its evolution. There are three periods representing the development of politics in this country. More importantly, "each of the periods is characterised by new forms of state-society relations, innovation in politics and the economy, as well as progress and regress in some development aspects".49 The first period starts from the formation of the FRELIMO party in 1962 in Dar-es-Salaam under the leadership of Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane. The second period begins from 1970 through to 1986 with Samora Moisés Machel in the top position. The third period is from 1986 up to 2004 under the leadership of Joaquim Alberto Chissano. Each of these periods had its own specific characteristic. For instance, Mondlane was a democratic man who can be compared with a republican president in America whose ambition was that politics be developed in a positive manner. With his death, the challenging issue was to find somebody with the same characteristics of those of Mondlane who would continue with his ideology.

The replacement of Mondlane was a dilemma because within the FRELIMO party there were different influences (socialist and pro-capitalist) and the plan of these forces was to turn Mozambique into a neo-colonial country despite its independence so that their ideologies would continue dominating the country. It was within this context that Samora Moisés Machel a simple military commandant came to the forefront as the person that could lead the destiny of the party after Mondlane's death. His nomination was influenced by Marcelino dos Santos a socialist within the party and of course Machel was to respect and obey the governing system of the person who suggested him as the leader. In this context, FRELIMO became a socialist party and, consequently, socialist policy was introduced and led the governing of Mozambique. It was with this perspective that the democratic centralism was constructed in the country following the system that the new leader had chosen. According to Hall and Young, democratic centralism meant the subordination of the lower to higher state bodies as well as the subordination of any state body to a higher state body and to the assembly at this level. This last principle was also called "double subordination".50

With democratic centralism governing, people were given the chance to bring their ideas for discussion at the grassroots level and some important suggestions were conceived. After the discussion, the same ideas were taken to the political bureau which in turn had the responsibility of selecting the ideas that came from the people. These issues were brought back to the people for its accomplishment, but at this level every person was supposed to obey since it came from a higher body and in a case of neglect there were sanctions or punishment. In other words, the same ideas that came from the people now were coming from the government as laws to be obeyed. It was in this framework that in 1978 there was a flood of legislation dealing with the Council of Ministers, provincial and local government and judicial system to regulate and maintain discipline of the people, public service and in addition attack liberalism.51

Multi-party regime

By their very nature, from the beginning, Mozambicans had in their mind the adoption and implementation of multi-party democracy. It is clearly shown from the formation of the three organisations, UDENAMO, MANU and UNAMI, which was amalgamated during the formation of FRELIMO with the assertion that these organisations were dividing Mozambicans. Perhaps the ruling group suspected that if the three organisations were to be accepted, it could represent the acceptance of a foreign type of ruling opposed to self-rule, considering that some of the people that started these organisations were outside Mozambique. However, the introduction of the multi-party democracy that is actually celebrated was in 1990 with the approval and publishing of the new Mozambican constitution allowing the creation and validation of the opposition parties. The multi-party system was introduced automatically and was also fulfilled by the first multi-party election held in 1994.52 Apart from the 1990 constitution, the GPA (General Peace Agreement) signed in Roma in October 1992 by the Government of Mozambique (FRELIMO) and RENAMO constituted a significant jump in the history of Mozambican democracy. It did not only bring peace to the country, but it also allowed changes to the constitution including the freedom to establish political parties and the introduction of elections as the only mechanism for achieving political power.53

• The Mozambican multi-party elections

The major objective of this analysis is to seek the pitfalls of the democratic process in Mozambique with more emphasis on the abstentions that were always observed in the elections within the range of analysis that took place in the country.

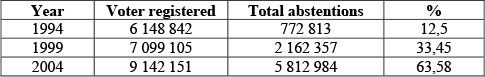

Summary of abstentions

The above table shows the situation of abstentions in the Mozambique elections. In 1994, elections had a better participation of people when comparing with the participation of 1999 and 2004 which were characterised by a high number of abstentions. For Mazula, the abstentions convey a strong message from the people that their conscience decided either to vote or not to vote.54 Because of this situation, two or more questions should be raised. First, what contributed to the participation of many people at the first election? Second, what are the reasons for the abstentions in the other two elections under discussion? Also, why does FRELIMO always win the presidential and legislative election in Mozambique?

• The impact of abstentions

The researcher bears with the words of Lundin when criticising abstention in Mozambican elections by saying that abstention is serious because something is lacking in the process.55 The issue of abstentions has to be taken into consideration for both Mozambique and for those countries56 that supported the elections financially. This is because of the impact that it has for the countries (the givers and the receiver). A lot of money spent on elections comes from donors as well as from local government. Therefore, from this perspective a high number of abstentions from the elections caused left-over ballots which cost a lot of money to produce. In the researcher's opinion, there is a lot of money that is wasted which could be used within the countries of the donors or within Mozambique to run useful projects in the Mozambican context. That amount would be better used to build schools and hospitals as well as run sustainable projects for Mozambicans for the development of the country.

This demands that something has to be done (on the electoral law, procedures, habit of respecting and fulfil what is written on law by the electoral organs, the ways of governing or even the way democracy is being understood from the side of the citizens) in order to change the scenario. The revision of electoral law that RENAMO is always demanding and other aspects of the political arena (depoliticisation, professionalism of the electoral organs, parity of members in CNE (Comissão Nacional de Eleições - National Electoral Commission) from parties that are represented in parliament) are some of the issues that deserve special attention in order to avoid problems such as mistrust among the political parties, and this of course will continue paving the way for genuine Mozambican democracy. To avoid a high number of abstentions from other elections taking place in Mozambique, political parties and their members and the electoral organs (the STAE or Secretariado Técnico da Administração Eleitoral - Technical Secretariat for Electoral Administration and the CNE) are called to be more serious regarding the following issues: The way civic education is conducted, the winners of elections are called to correspond towards the solution of the problems of people who had voted for them, seeking to fulfil what they have promised during the campaign for the election. In addition to that, the winners are to make sure that people feel they contribute to the process of constructing Mozambican democracy.

The contribution of the state towards Mozambican Democracy

The contribution of the state towards Mozambican democracy can only be seen through analysing the development of the political history of the country. It is recognised that the political regime, which was previously called the Mozambican revolution, started reflecting about its activities and philosophy - which was called Marxist philosophy - as well as reflecting about the national and international consequences of this philosophy. With independence and the nationalism of the country, Mozambique entered into the international community which also had a role to play. One of the aspects that marked this period was the fact that the late president Samora Moisés Machel gained influence and a reputation at an international level. This situation contributed and opened ways for reflection on Mozambican philosophy, its applicability and the consequences at national and international level. The first stage of the reflection, which is considered very important by religious people, was when president Machel invited a meeting involving personalities from the government and religious institutions (Roman Catholic Church, Christian Council and Muslim Community). At that meeting different challenging issues facing Mozambican religions were discussed concerning the new revolutionary regime in the country. The discussion came to the satisfactory conclusion that the religious institutions in Mozambique had an important role to play in the new Mozambique. This conclusion for every Mozambican came as a surprise considering that from independence up to that moment there was a declared opposition between the two (the state and religion). From that moment onward the religious institutions had a role to play, especially in the area of moral and patriotic education of the citizens. It clearly shows that the regime started to think afresh about the relation between the church and religion in Mozambique, not only at national level, but also at international level. The consequence of that reflection was the initiative of revising the Constitution of Mozambique which happened in 1990 and a lot of changes in the constitution came as a surprise for many people in Mozambique. With the new constitution democracy was officially established in Mozambique, not only centralised democracy but a multi-party democracy. It was from this perspective that the Mozambican state through the new constitution recognised Mozambique as a pluralist society. At the same time the new constitution was published, negotiation for peace also started in Mozambique. This happened in July 1990. During the negotiation for peace, the issue of a multi-party democracy was discussed significantly and the GPA established a multi-party system in Mozambique which recognises the liberty of citizens. On this note, either the new constitution or the GPA agreed that a multi-party democracy was to be introduced in Mozambique. Therefore, "[t]he state should be one of the models of organising an overall public- a community in which the members of groups will find, experimentally, a harmony between their objectives."57 Wittrock adds that the state is always faced with two broad political projects, namely that of reconstituting identity and a culture in terms of nationhood; the state has to work on politically emancipating or integrating the new working class of industrial society as well as the people at grassroots.58

The contribution of the church towards Mozambican democracy

The church has the spiritual and moral resources to contribute towards Mozambican democracy and of course it has to be awakened to its spiritual and moral responsibility, otherwise its presence in society would be meaningless. De Gruchy, when seeking to bring the contribution of the church for nation building and democracy, highlighted the following:

Democracy implies the acceptance of religious pluralism and tolerance at the very least, but it also requires that people of different faiths learn to co-operate in bringing about the just democratic transformation of society.59

The quote above makes it clear that there is no way of separating democracy and the church; the two have to work together for the benefit of society and this constitutes the major project of democracy. The involvement of the church in a situation that constrains society was observed before democracy was introduced. It was the church (Protestants) that worked hard at fighting illiteracy in different countries in Africa. Then the church cooperated significantly in the process of liberating countries that went through colonial domination and Mozambique was a particular example. The crucial question to be considered is how the church should continue contributing in this democratic era. The writer found the ideas of two different scholars when analysing this matter crucial. The first one is by De Gruchy, who wrote the following:

The primary contribution of the churches to democratisation has undoubtedly been their ability to mediate between warring factions, and facilitate national reconciliation and reconstruction . churches are in a unique position to influence political developments, providing social cohesion at a time of national fragmentation and gathering international support in the struggle for justice and democracy. But even more, they are in daily touch with people, they often have a larger and more committed membership than political parties and, in many instances, their understanding of the situation on the ground is better than of the politicians ... it is at local community level that the church is often strongest and able to make the greatest difference in democratic transformation.60

Critical findings

Considering that Mozambican democracy is still very young in a situation where people were used to a one-party democracy, confusion is noticeable amongst political parties especially with the ruling party. They tend to mix activities that belong to the party itself and those that are specifically for the state.

Another characteristic of the Mozambican democracy is the fact that the top leaders of different parties and their followers make the mistake of promising what they cannot deliver and this makes Mozambican democracy very weak since people no longer trust the words of political parties.

State departments labelled with different parties, lack of transparency in the electoral process, and the use of mineral resources for the benefit of a few people, are some of the examples of the negative issues that people claim are practiced in the country, which ends up removing the merit of our democracy in Mozambique. Here the researcher refers as examples the police, judiciary system and different ministries that exist in the country. The problem is that to some extent they are used for the benefit of one party and sometimes are even to promote the ruling party when they should be working for all Mozambican citizens. This demonstrates a clear lack of separation of power between the state and ruling party. Some of those belonging to the ruling party who were elected to serve in the name of the state still deliver speeches that demonstrate that they still work for the interest of the party, forgetting that they were elected to work for Mozambicans.

A deep analysis of Mozambican democracy illustrates that there is still a lot to be achieved, especially when it is related to practical democracy, there are many faults that still need to be corrected so that Mozambique can enjoy a true democracy. For instance, the written democracy is acceptable to some extent but the way it is implemented is not acceptable as the following examples illustrate.

The political persecution still prevalent in Mozambique rubs off the value of democracy and, on the one hand, causes people to be afraid of joining other political parties from the ruling party and, on the another hand, causes people to be enrolled as members of two different parties (one being the ruling party as a guarantee of employment and other benefits and the other the party which is of his/her choice). Automatically, these people will hold two different membership cards, the red card (identifying people as members of FRELIMO) to be displayed for matters of employment since this is considered the basic instrument to be used in Mozambique if somebody is to be employed and the other card for the political party they truly belong to. In the researcher's view, this situation sometimes deludes the ruling party into thinking that it has many supporters in some areas while there are really few.

Another critical issue in Mozambican democracy is related to the type of speeches coming from the Mozambican political parties. For instance, it is common to hear some top leaders of the Mozambican state saying that FRELIMO has done this and that or even to auto proclaim as the better people and better party. In addition to that, leaders of RENAMO are also calling themselves the father of democracy. The researcher considers this as negative since people in the state are now working for the interest of all Mozambicans and being state leaders, they represent all Mozambicans including those that belong to the opposition. This kind of pronunciation makes the smaller political parties feel excluded in Mozambican democracy. But if Mozambique is to experience democracy, the members of political parties have to learn to respect each other's opinion knowing that every party is aspiring for pure democracy in Mozambique.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study observed that the introduction of democracy in Mozambique is a result of bloodshed (civil war) as well as the involvement of different organisations that were negotiating with FRELIMO and RENAMO. However, evaluating Mozambican democracy from a critical perspective it is clear that there is still a lot to be achieved in this democracy and it really needs the involvement of every Mozambican in the process.

On the one hand, if the Mozambican state is to do well concerning democracy, it should re-evaluate the ways of Mozambican democracy since its introduction in 1990 and try to find its weaknesses and open space for dialogue. On other hand, the opposition parties are also called to do the same so that a true democracy can be implemented in the country.

Finally, churches and other religious organisations are called to get involved in the democracy implementation in Mozambique.

Works consulted

Baur, J. 1994. 2000 Years of Christianity in Africa. Nairobi: Paulines Publications. [ Links ]

Boahen, AA. 1987. African perspectives on Colonialism. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Publisher. [ Links ]

Cabrita, JM. 2000. Mozambique: the tortuous road to democracy. New York: Palgrave Publisher [ Links ]

Carvalho, EJM. 1983. Teologia e Prática do Metodismo: Uma Experiência da Igreja em Angola. SP: Imprensa Metodista. [ Links ]

Chamango, S. 1982. A Chegada do evangelho em Mozambique. Maputo: Ricatla Seminary: 1-36. [ Links ]

De Gruchy, JW. 1995. Christianity and democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ferreira, LC. 1987. Igreja Ministerial em Mozambique: Caminhos de Hoje e de Amanhá. Maputo: Imprimi Potest. [ Links ]

Hall, M. & Young, T. 1997. Confronting Leviatan: Mozambique since independence. Atnes: Ohio University Press. [ Links ]

Henriksen, TH. 1978. Mozambique: A History. Cape Town: Rex Collings with David Philip Publisher. [ Links ]

Hoile, D. 1994. Mozambique, resistance and freedom: a case for reassessment. London: Mozambique Institute. [ Links ]

Isaacman, A. & Isaacman, B. 1983. Mozambique: From Colonialism to Revolution, 1900-1982. England: Westview Press. [ Links ]

Jenset, IS. 2005. Democratization as development aid in Mozambique. (no further details available). [ Links ]

Lundin, IB. 2006. Eleifoes Gerais 2004- Um Eleitorado Ausente, in Mazula, B. et al (ed.), Mozambique: Eleições Gerais 2004 Um olhar do Observatório Eleitoral. Maputo: Imprensa Universitária, 51-122. [ Links ]

Maluleke, TS. 1998. Black Theology as public discourse. Available at: http://web.uct.ac.za/depts/ricsa/me99/docs/maluleke.htm. Accessed on 11 November 2010. [ Links ]

Mazula, B. 2006. Voto e Urna de costas voltadas: Abstenzáo Eleitoral 2004. Maputo: Imprensa Universitária. [ Links ]

Mittelman, JH. 1981. Under development and the transition to socialism: Mozambique and Tanzania. New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Molutsi, P. 2004. Botswana: the path to democracy and development, in Gyimah-Boadi, E. (ed.), Democratic reform in Africa: the quality of progress. London: Lynne Rienner Publisher, 159-181. [ Links ]

Mondlane, E. 1995. Lutar por Mozambique. Maputo: Centro de Estudos Africanos Publications. [ Links ]

Morier-Genoud, E. 1996. Of God and Caesar: The relation between Christian and the State in Post-Colonial Mozambique, 1974-1981. (no further details available). [ Links ]

Nuvunga, A. 2005. Multiparty democracy in Mozambique: strengths, weaknesses and challenges. Johannesburg: EISA. [ Links ]

Parry, G. 1994. Making democrats: education and democracy, in Parry, G. & Moran, M (ed.), Democracy and democratization. London: Routledge Publisher: 47-68. [ Links ]

Reibel, AJ. 2011. An African success story: civil society and the 'Mozambican Miracle'. Available at: http://africanajournal.org/PDF/vol4no1/vol4no13Aaron%20J.%20Reibel.pdf. Accessed on 21 January 2011. [ Links ]

Rossouw, GJ. & Macamo, Jr. E. 1993. Church-State Relationship in Mozambique. Journal of Church and State 35(3), 537-546. [ Links ]

Serapião, LB. 2010. The Catholic Church and conflict resolution in Mozambique's post-colonial, 1977-1992. Available at: http://jcs.oxfordjournaisa.org. Accessed on 26 July 2010, 364-387. [ Links ]

Sindima, HJ. 1994. Drums of redemption: an introduction to African Christianity. London: Praeger Publisher. [ Links ]

Vines, A. & Wilson, K. 1995. Churches and the peace process in Mozambique, in Gifford, P. (ed.), The Christian Churches and the democratisation of Africa. Leiden: EJ. Brill, 130-147. [ Links ]

Wittrock, B. 1998. Rise and development of the modern sate: democracy in context, in Sainsbury, D. (ed.), Democracy, State and justice: critical perspectives and new interpretations. Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 113-125. [ Links ]

1 According to Henriksen, the name 'Mozambique' derives from one Musa al Bique, a sheikh or a prominent person on the island.

2 T.H. Henriksen, Mozambique: a history, Cape Town: Rex Collings with David Philip Publisher (1978), 1.

3 S. Chamango, Sumário da História da Igreja em Mogambique (1991), 10.

4 Chamango, Sumário da História da Igreja em Mogambique, 10.

5 Henriksen, Mozambique, 21.

6 H.J. Sindima, Drums of redemption: an introduction to African Christianity. London: Praeger Publisher, (1994), 56.

7 For detailed information on Prazos, the research recommends a book written by TH Henriksen entitled Mozambique: a history, Cape Town: Rex Collings with David Philip Publisher, (1978).

8 Henriksen, Mozambique, 55.

9 E. Mondlane, Lutar por Mozambique, Maputo: Centro de Estudos Africanos Publications, (1995), 33.

10 Extrated from T. Maluleke, Black theology as public discourse. Concept Paper for the Academic Workshop Cape Town, 30 September - 2 October 1998 in http://web.uct.ac.za/depts/ricsa/me99/docs/maluleke.htm (accessed on 11 November 2010).

11 L.C. Ferreira, Igreja Ministerial em Mozambique: Caminhos de Hoje e de Amanhã, Maputo: Imprimi Potest (1987), 31.

12 Fereira, Igreja Ministerial em Mozambique, 72.

13 Fereira, Igreja Ministerial em Mozambique, 72.

14 H.J. Sindima, Drums of redemption, 56.

15 Prelature Nullius means a certain area of Roman Catholic Church that is functioning without a Prelate/Bishop. In such a situation, the Pope chooses an Administrator to run the activities of the Church.

16 Ferreira, Igreja Ministerial em Mozambique, 72-74.

17 Fereira, Igreja Ministerial em Mogambique, 74.

18 A Portuguese term that immerged as a reply to the accusation thrown by indigenous to the Portuguese as racists. The Portuguese gave this status to some Africans arguing that from the moment they are given this status, they belong to the Portuguese community with the same privileges as those of the Portuguese. They were the most Christinised, civilised Africans compared to their counterparts. Looking deeply at what was going on with these assimilados; it was not true that they had the same privileges. The only thing is that they escaped some of the restrictions that the indigenous people experienced. Even with the status of assimilado, their economic situation was totally different from that of the Portuguese, even in terms of education the assimilado needed to make more effort than the white in order to pass; in most cases the assimilado did not use the same toilet as the Portuguese. To be assimilado meant not to be accepted as an African but to identify with Portuguese people. This was really a cultural, political and economic identity prejudice for colonised people.

19 A. Isaacman and B. Isaacman, Mozambique: from colonialism to revolution, 1900-1982, Boulder: Westview Press (1983), 53.

20 A.J. Reibel, An African success story: civil society and the Mozambican miracle's in http://africanajournal.org/PDF/vol4no1/vol4no1_3_Aaron%20J.%20Reibel.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2011).

21 A.A. Boahen, African perspectives on colonialism, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, (1987), 96-99. The researcher adds that it is important to note that in 1885 most countries in Europe met in Berlin and demarcated Africa without setting a foot on this continent.

22 Boahen, African perspectives on colonialism, 100.

23 Boahen, African perspectives on colonialism, 104.

24 Isaacman and Isaacman, Mozambique, 61-62.

25 Isaacman and Isaacman, Mozambique, 61-73.

26 Mozambican tribe living in Southern Mozambique in Inharrime and Zavala district in Inhambane province.

27 Mozambican tribe in Cabo Delgado province in the North of Mozambique.

28 M. Hall & T. Young, Confronting Leviathan: Mozambique since independence, Athens: Ohio University Press (1997), 12.

29 Isaacman and Isaacman, Mozambique, 81.

30 Isaacman and Isaacman, Mozambique, 84.

31 Isaacman and Isaacman, Mozambique, 81.

32 Isaacman and Isaacman, Mozambique, 172.

33 J.H. Mittelman, Underdevelopment and the transition to socialism: Mozambique and Tanzania, New York: Academic Press (1981), 38.

34 M. Hall & T. Young, Confronting Leviathan, 43.

35 D. Hoile, Mozambique resistance and freedom: a case for reassessment, London: Mozambican Institute, (1994), 15.

36 G.J. Rossouw and E. Macamo Jr, Church-State relationship in Mozambique, http://jcs.oxfordjournals.org (accessed on 26 July 2010), 537.

37 L. Brito Serapião, The Catholic Church conflict resolution in Mozambique's colonial conflict, 1977-1992, http://jcs.oxfordjournaisa.org (accessed on 26 July 2010), 372.

38 Hall and Young, Confronting Leviathan, 8.

39 This was possible in Mozambique because by 1970 the 'Colégio Pedro Nunes- Pedro Nunes College' was opened in Lourenço Marques, now Maputo under the leadership of the first graduate of the Mozambique Methodist Episcopal Church, Dr. Almeida Penicela.

40 Rossouw and Macamo, Jr. Church-State relationship in Mozambique, 538.

41 E. Morier-Genoud, Of God and Caesar: he relation between Christian Churches and the State in post-colonial Mozambique, 1974-1981 (no further details available), 17.

42 E.J.M. Carvalho, Teologia e Prática do Metodismo: Uma Experiência da Igreja em Angola, SP: Imprensa Metodista, (1983), 34.

43 J.M. Cabrita, Mozambique: the tortuous road to democracy, New York: Palgrave Publisher, (2000), 21.

44 J. Baur, 2000 Years of Christianity in Africa, Nairobi: Paulines Publications, (1994), 439.

45 Hall and Young, Confronting Leviathan, 156.

46 Rossouw and Macamo, Jr. Church-State relationship in Mozambique, 539.

47 Rossouw and Macamo, Jr. Church-State relationship in Mozambique, 541.

48 I.S. Jenset, Democratisation as development aid in Mozambique: which role does education for citizenship play? (2005), 43.

49 P. Molutsi, Botswana: the path to democracy and development, London: Lynne Rienner Publisher, (2004), 164.

50 Hall and Young, Confronting Leviathan, 72.

51 Hall and Young, Confronting Leviathan, 72.

52 A. Vines and K. Wilson, Churches and the peace process in Mozambique, Leiden: E.J. Bril Publisher, (1995), 140.

53 A. Nuvunga, Multiparty democracy in Mozambique: strengths, weaknesses and challenges, Johannesburg: EISA, (2005), 1.

54 B. Mazula, Voto e Urna de costas voltadas: Abstengdo Eleitoral 2004, Maputo: Imprensa Universitária (2006), 7.

55 I.B. Lundi, Eleições Gerais 2004- Um Eleitorado Ausente, Maputo: Imprensa Universitária (2006), 101.

56 Countries like Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and European Union were supporters of the Mozambican elections in 1999. The total budget of ,000.00 was spent for the elections in the following programs: transport, communication, material, training, civic education, salaries, subsidies, investments (acquisition of vehicles and computers), technical assistance and miscellaneous.

57 G. Parry, Making democrats: education and democracy, London: Routledge Publisher (1994), 57.

58 B. Wittrock, Rise and development of the modern State: democracy in context, Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksell International Publisher (1998), 116.

59 J.W. de Gruchy, Christianity and democracy, New York: Cambridge University Press (1995), 185.

60 De Gruchy, Christianity and democracy, 187.