Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

versión On-line ISSN 2412-4265

versión impresa ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.39 no.2 Pretoria feb. 2013

MISSIONARY HISTORIES

African intermediaries: African evangelists, the Dutch Reformed Church, and the Evangelisation of the southern Shona in the late 19th century

Joseph Mujere1

History Department, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

ABSTRACT

Although some Christian denominations employed more African evangelists than others, African evangelists were quite indispensable in evangelisation of many African communities in the late 19th century. In the end, it was often the case of Africans evangelising other Africans rather than a purely European enterprise. Apart from working as evangelists and lay preachers, early African converts also worked as translators, porters, guides, and aides among other jobs. This article analyses the role played by African evangelists in the evangelisation of areas to the north of the Limpopo River in the period before the colonisation of what is now Zimbabwe. It pays particular attention to the work of African evangelists working with the Dutch Reformed Church and the Berlin Missionary Society. This article also attempts to recover the voices of the African men and women through whose efforts the Dutch Reformed Church and the Berlin Missionary Society were able to establish mission stations and spread Christianity among the southern Shona prior to the colonisation of Zimbabwe.

Introduction

Works on Christian missions and evangelisation in Africa have largely focussed on the role played by European missionaries as propagators of the gospel and Africans as recipients. However, there has been a recent upsurge in works analysing the roles played by African evangelists in evangelising their fellow Africans. Such works have shown evidence of how Africans adopted Christianity and also how African evangelists became vanguards in the spread of Christianity in southern Africa. It is therefore important to recognise the roles played by both European missionaries and African agents in the evangelisation of Africa.2 This article analyses the role played by African evangelists in the northwards expansion of Christianity in the late 19th century. It argues that although some Christian denominations employed more African evangelists than others, African evangelists were quite indispensable in European missionaries' efforts to evangelise Africans in the late 19th century. In the end, it was often the case of Africans evangelising other Africans rather than a purely European enterprise. Apart from working as evangelists and lay preachers, early African converts also worked as translators, porters, guides, and aides among other jobs.

In analysing the role played by African evangelists in the evangelisation of areas to the north of the Limpopo River, this article pays particular attention to the work of African evangelists working with the Dutch Reformed Church and the Berlin Missionary Society. This article also attempts to recover the voices of the African men and women through whose efforts the Dutch Reformed Church and Berlin Missionary Society were able to establish mission stations and spread Christianity among the southern Shona prior to the colonisation of Zimbabwe. It thus uses the case of Basotho evangelists to explore African agency in the evangelisation of the Shona people in the late 19th century.

Although a number of African evangelists, among them Zulu, Venda, and Xhosa, played a critical role in the evangelisation of the southern Shona in what is now Zimbabwe, the Basotho were arguably the ones who played the greatest role. The Basotho in particular had a longer history of participation in evangelisation work. As Weller and Linden argue, "the Sotho Christians had an early opportunity to act independently, for the missionaries were expelled from the country by the Boers in 1865; their converts rose admirably to the challenge and 'gave themselves up to preaching the Gospel most zealously, and with remarkable results'.3 The converted Basotho took the initiative to evangelise fellow Africans to Christianity.

The reason why African evangelists became the vanguards of evangelisation among the Shona was that a number of them had gone into Mashonaland before the missionaries had been to the area. For example, the Buys brothers were quite familiar with the area to the north of the Limpopo because they had visited the area on hunting expeditions. In this regard, these African evangelists had a better understanding of the geography of Mashonaland and some of them were proficient in the Shona language.

Missionaries, evangelisation and Basotho evangelists

The history of the Basotho community in the Dewure Purchase Areas in Gutu district is greatly linked to the history of evangelisation of the Shona people in southern Zimbabwe. Basotho in Lesotho and in the Transvaal region of South Africa were some of the earliest Christian converts in the region. As early as 1842, the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society (PEMS) mission at Morija had 28 converts and by 1848, they were 251.4 According to Maloka, although it was not successful in converting Moshoeshoe and his court, "the PEMS managed to style itself as the 'church of Moshoeshoe'".5 The PEMS carried evangelisation work among Basotho in Lesotho and also in the mine compounds of South Africa.

Over the years, a number of Basotho converts and other Africans became trusted evangelists aides of missionaries in a number of protestant churches which include the PEMS, Berlin Missionary Society (BMS) and the Dutch Reformed Church (DRC). According to Coplan, "in the mid 19th century, the Basotho (sing.: Mosotho) were lauded by missionaries and resident British officials for their courtliness, ingenious adaptability, and eagerness for the 'progress' they believed would come from the adoption of European ways".6 In the end, most missionaries who set off to carry out evangelical work among the southern Shona (then generally referred to Banyai) from South Africa and Lesotho took with them some Basotho and other African converts who became quite indispensable as guides, porters and, most importantly, evangelists. Hence, in tracing the history of Basotho who are in the Dewure Purchase areas and surrounding areas, it is imperative to examine it in the light of the general history of the establishment and development of mission stations among the Shona in the southern parts of Zimbabwe and the evangelisation of these areas.

The development of mission stations among the southern Shona can be divided into two broad phases. The first phase began in the 1870s and ended in 1883. This phase saw the DRC, the PEMS and the Swiss "Mission Vaudoise" making some first steps towards establishing mission stations among the southern Shona, especially in Chivi and Zimuto areas.7 Although the missionaries did not have much success in that period, they worked closely together and shared experiences and information about the area. The second phase, from 1883 to 1894, saw the BMS and the DRC go on expeditions among the southern Shona people. This culminated in the establishment of Morgenster and Chibi Missions by the DRC and BMS respectively.8 During both phases, African converts played an important role in aiding and spearheading missionary penetration among the Shona.

Although initial efforts at establishing mission stations had been made by several groups and their African allies, greater missionary penetration was achieved in the second phase of missionary activity among the Shona. It was during this phase that missionaries began to establish more permanent mission stations across the Limpopo River. That period saw the DRC, BMS and PEMS missionaries commissioning no less than 21 expeditions from South Africa into the southern Shona to the north of the Limpopo River. It is important to note that although the expeditions were directed by the white missionaries, most of them were conducted by African evangelists, among them Venda, Pedi, and Basotho, thus underlining the importance of African evangelists in the missionary activities.9

The establishment of a mission station at Goedgedacht in Transvaal in February 1865 by Rev Stephanus Hofmeyr, a DRC missionary, was a key development in the evangelisation of Shona people in the late 19th century.10 It became a launch pad for evangelisation of the southern Shona. Although Rev Hofmeyr's objective was the conversion of the Venda and Sotho people in Zoutpansburg, he was soon making enquiries about sending people to the north of the Limpopo among the southern Shona. As Mazarire argues, the establishment of the DRC mission at Goedgedacht constituted the major first step towards the evangelisation of the "southern Shona".11 At Goedgedacht, Rev Hofmeyr was ably assisted by the Buys brothers and a number of African evangelists. The Buys brothers were coloured members of the DRC congregation at Goedgedacht who were descendents of Coenraad de Buys and his many African wives.12

Soon after the establishment of the Goedgedacht mission, Hofmeyr began to make enquiries about the possibility of evangelising the Shona people to the north of the Limpopo River after hearing about them from the Buys brothers who had ventured there a couple of times.13 He quickly sent off Simon Buys and an African evangelist to Mashonaland to inform them that missionaries would come to work among them. Rev Hofmeyr is also credited for realising the need to recruit African evangelists for the evangelisation of the Shona (then referred to as Banyai) to the north of the Limpopo River.14 This saw Africans playing a more important role in the evangelisation work.

The late 1860s and early 1870s saw a number of evangelists crossing the Limpopo and making contacts with some Shona chiefs. They also took the opportunity to lay the ground for more permanent mission stations. In 1872, Gabriel Buys left Goedgedacht and began preaching in Chief Zimuto's area until 1876 when he went back.15 Gabriel Buys was a coloured member of the DRC congregation who periodically went north of the Limpopo River on hunting expeditions during which he would take some time to preach to the Shona people.16 Gabriel Buys' expedition was followed by that of his brother Simon who was accompanied by Asser Sehahabane, a Sotho evangelist. The expedition was jointly organised by the PEMS, DRC and the Swiss "Mission Vaudoise". Asser Sehahabane, together with Jonathan, a Pedi, and Simon Buys, left Goedgedacht in 1874 and crossed the Limpopo River to carry out evangelisation among the Shona, reaching as far north as chief Zimuto's area.17 They returned with the news that the Shona were very keen on receiving evangelists in their areas.

Having received encouraging news from Sehahabane and others about the Shona's reception of Christianity, the PEMS resolved to send missionaries and African evangelists on an evangelisation mission among the Shona. Hofmeyr had problems in mobilising human and material resources to launch mission activities beyond the Limpopo.18 However, Sehahabane and the other Africans, who had accompanied him to Mashonaland, preached to the other Basotho about their expedition and the need to gather human, financial and material resources for the establishment of a mission station among the Shona.19 They received so much support from other Basotho who agreed that there was a great need to support the evangelists who were carrying out evangelising expeditions among the Shona. According to Mashingaidze, "not only did the Basotho give whatever they could, but many also volunteered to go and work among the people of Zimbabwe. Some, who were too old to volunteer, offered their young sons for missionary work".20 The main reason why Basotho were so keen to contribute towards the spread of Christianity among the Shona was that as converts to Christianity, they felt that they had to contribute towards the evangelisation of other Africans.

Consequently, the PEMS resolved in their 1875 conference in Lesotho to send a team led by Asser Sehahabane to Mashonaland. Unfortunately, they were denied passage by the Boer Transvaal government in Pretoria and were arrested.21 In 1876, Rev Dieterlen made another attempt to visit the Shona and received similar treatment from the Boers. In spite of these setbacks, the missionaries continued to make concerted efforts to establish mission stations in Mashonaland. Upon their release from custody by the Boers, Sehahabane and other evangelists and their PEMS missionaries organised another expedition to go into Chivi and Zimuto areas.

In 1877, Francois Coillard, who belonged to the French Calvinist Missionary Society, which was part of the PEMS, left for Mashonaland. According to Weller and Linden, a key feature of Coillard's expedition was that several of its members were Sotho evangelists and the venture had come from African Christians.22 Coillard was accompanied by four Basotho evangelists who included Asser Sehahabane and Aaron who were to carry out evangelisation work to Chivi, Azael and Andreas who were to work among the people in Chief Zimuto's territory.23 Hofmeyr also gave them three of his best evangelists, Simon and Jesta Buys and their cousin, Michael. According to Mashingaidze, "the Coillards and Hofmeyr's three men were to return to the south as soon as it was clear that the missions were established. In other words, the Basotho were going to settle in Zimbabwe permanently-Sehahabane and Aaron in Chivi's and Azael and Andreas at Zimuto".24 This underlined the significance of the role of Basotho evangelists as frontiersmen in the spread of Christianity among the southern Shona.

Missionaries' preference for Basotho can be argued to have been a result of the fact that Basotho were some of the earliest converts to Christianity and also that they showed great interest in evangelisation work. According to WJ van der Merwe, Basotho evangelists, among them, Lucas Mokoele, Joshua Masoha and Micha Makgatho were some of the greatest African evangelists during the early period of evangelisation in Transvaal and Mashonaland, rivalled only by Isaac Khumalo (a Zulu) and Gabriel Buys (a coloured) who worked with DRC missionaries.25 Therefore, African evangelists and lay preachers, especially from South Africa and Lesotho, were quite indispensable in the evangelisation of the areas to the north of the Limpopo. After the death of Gabriel Buys, however, the significance of the Buys family in the evangelisation work dropped because he had been the most zealous member of the family and the leading figure.26 However, after the death of Gabriel Buys, Africans working with the DRC and the BMS took over the task of evangelisation, although they went to other areas.27

The BMS established two missions among the Venda in Transvaal which they used as launch pads for their own expeditions to the north. The mission at Chivasa was established in 1872 and the Tshakona Mission was established in 1874.28 The first expedition which was not very successful was carried out by Buester in 1884. This was followed by another expedition, this time led by David Funzane, a Venda evangelist. The expedition was more successful than the first one with the team going as far as Bikita among the Duma people in southern Zimbabwe.29 According to Weller and Linden, these African evangelists preached among the Shona until they were later joined by two German missionaries, Schwellnus and Knothe.30 They also got help from Shona migrant workers who were returning from mines in South Africa. In 1888, the BMS, led by Knothe and Schwellenus, launched their own evangelisation mission among the Chivi people, which culminated in the establishment of Chibi Mission in 1894.31

The DRC in particular employed a number of African evangelists who eventually laid the ground for the establishment of more permanent stations. As highlighted earlier, a number of missionary expeditions sent off by the DRC from Goedgedacht were actually led by African evangelists. According to Beach, in 1887, five Basotho men, who included Micha Makgatho, Joshua Masoha, Zacharia Ramushu, Simon Nyt and Michia Choene, crossed the Limpopo River and reached Nyajena where they were well-received by the chief who showed some interest in Christianity.32 This party reported favourably about the possibility of the Shona people receiving the Gospel and converting to Christianity. The expedition was followed by yet another in 1889 led by Makgatho, Masoha and Lucas Mokoele who visited Murove, Madzivire and Nyajena areas. They also paid a courtesy call to Chief Mugabe.33 These three Basotho men visited Chief Mugabe again in 1890 when they guided Reverend SP Helm, who when he talked to Chief Mugabe, realised that the chief was keen to have a mission station established in his area.34 These expeditions thus set the stage for the establishment of the DRC mission station in Chief Mugabe's area.

Meanwhile, the BMS was negotiating with Chief Zimuto for the establishment of a mission station in his area. This culminated in the establishment of Zimuto Mission in 1892. Chief Zimuto also granted the Jesuits permission to establish a Roman Catholic Mission at Gokomere in 1893. In 1894, the BMS established another mission in Chief Gutu's area. However, most of these missionaries were welcomed not because the chiefs wanted their subjects to convert to Christianity, but for their potential usefulness as allies in local conflicts and also as trading partners.

When the 1890 expedition led by Rev SP Helm returned to Goedgedacht, they made a very impressive report to Rev Hofmeyr on the possibility of establishing a mission station in Chief Mugabe's area. Rev Hofmeyr immediately began to make enquiries on who could be sent to establish a mission station among the Shona people. As a result of that, AA Louw set out from Goedgedacht on 8 April 1891 to Chief Mugabe's area.35 His objective was to establish a permanent DRC mission station in Chief Mugabe's area. According to Van der Merwe, AA Louw left Kranspoort (Goedgedacht) with some seven Basotho volunteers who included Micha Maghatho, Joshua Masoha, Jeremiah Murudu, Petros Murudu and Lucas Mokoele.36 These Basotho volunteers worked as evangelists, guides and interpreters since some of them had knowledge of the area as they had been to these areas before. On 9 September 1891, AA Louw and his Basotho evangelists arrived in Chief Mugabe's area and established a mission station at Mugabe hill which became the first DRC mission in colonial Zimbabwe and the centre of DRC missionary work among the southern Shona people.37

As they had become trusted partners in the evangelisation work, Rev AA Louw sent out the Basotho evangelists to different communities where they had to carry out their evangelical work. Jeremiah Murudu and his brother, Petros Murudu, were posted at Matibi and Neshuro respectively, Isaac Khumalo went to Vurumela amongst the Hlengwe, Lucas Mokoele went to Madzivire, Joshua Masoha to Ruvanga and Micha Makgatho to Nyajena. David Molea and Petrus Khobe were posted in the territories of Mugabe (where Morgenster Mission was located) and Shumba Chekai.38 David Molea also acted as AA Louw's interpreter since he could speak chiKaranga, the language spoken by the locals, further cementing the reputation of Basotho as people who were quite conversant with the local languages.39 David Molea had been to this area in several evangelisation and hunting expeditions and had learnt the languages spoken in the area during these expeditions. Apart from carrying out evangelical work in the communities they had been posted, Basotho also served as teachers and opened schools in these communities.

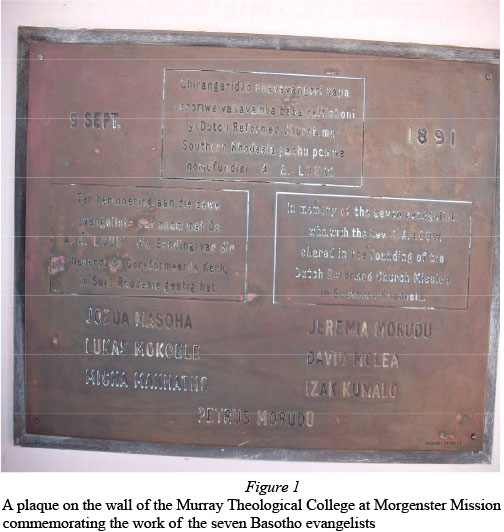

In commemoration of the role played by the seven evangelists who worked with Rev AA Louw a plaque was placed on the Henry Murray Theological College at Morgenster Mission. The plaque has the inscription, "in memory of the seven evangelists who, with Rev AA Louw, shared in the founding of the Dutch Reformed Church Mission in Southern Rhodesia". This was a great recognition of the central role played by African evangelists not only in the establishment of Morgenster Mission but also in the spread of Christianity in the whole country. Morgenster Mission was established on 9 September 1891 through the efforts of a couple European missionaries and several African evangelists who were then sent out to various communities to preach, to convert people, and to even establish schools.

In 1907, the DRC took over the mission stations which had been established by the BMS. These included Gutu which was established in 1892, Chibi established in 1894 and Zimuto established in 1904. Chibi Mission was nearly closed because there was no European missionary to run it for several years. The mission was only saved from closure by Joseph Mboweni, a Shangaan evangelist who persevered on his own until 1911 when Rev Hugo and his wife joined him. The fact that Chibi Mission was saved from closure by an African evangelist after it had been abandoned by the BMS in 1907 demonstrates the central role that African evangelists played in the establishment and running of many mission stations and in the evangelisation of their fellow Africans.

Apart from PEMS, DRC and BMS, Wesleyans also had a number of African evangelists who assisted them in their evangelical work among the Shona. When the Wesleyan pioneer missionaries Owen Watkins and Isaac Shimmin went to colonial Zimbabwe in 1892, they employed a number of African evangelists. Within a short space of time, the Wesleyan missionaries had a large contingent of African evangelists. According to Mashingaidze, having arrived in 1892, within a year of their settlement, "the Wesleyan Society was by far the largest employer of black evangelists from the south [South Africa]. About ten more evangelists arrived. These were Josiah Ramushu, Mutsualo and John Molimeli Molele (Basotho); and seven Xhosas - Tutani, Belesi, Mutyuali, Mulawu, Fokasi, Shuku, and James Anta".40 Just as they did with the DRC, Basotho again formed a large part of the African evangelists who worked with the Wesleyans missionaries. In fact, Josiah Ramushu, who was the oldest among the ten African evangelists working with the Wesleyans, "was given the task of starting a school at Chiremba (Epworth) and the rest were sent to areas such as Gambiza's and Kwenda among the Njanja".41

However, in spite of the almost indispensable role of African Evangelists, some missionaries such as the German Jesuits, who founded Chishawasha Mission in 1892, did not employ African evangelists until about 1911. This was mainly because of Roman Catholic conservatism coupled with the fact that the team was composed of a large number of missionaries.42 Be that as it may, African evangelists continued to play a key role in the evangelisation of their fellow Africans. The first converts became ambassadors of the new faith.

Apart from their desire to spread the gospel among their fellow Africans, however, evangelical work had other attractions for Africans such as providing them with opportunity to advance their education and also to accumulate wealth. A number of Africans who worked as evangelists managed to advance their education, got employed as teachers, clerks and interpreters among other jobs. This enabled them to accumulate wealth and became members of an emerging group of African elites during the early colonial period. As Ranger argues, within the context of colonial rule, "Christian converts used Christianity as a means of surviving or succeeding in the economic and social realities of colonialism."43

The role played by African evangelists was described by Mashingaidze as that of "frontiersmen" or the vanguard of the advance of Christianity in the African interior.44 More often than not, it was the African evangelists who were the first to preach to the Shona people and to convert them to Christianity before the missionaries came and established permanent stations.45 According to Beach, though the missionaries usually assumed that a mission station and evangelisation began with the permanent settlement of European missionaries among the local people, "for the Shona, their experience of Christianity at first hand often began when an African evangelist arrived to preach and lay the foundation for a later mission".46 Therefore, most of the missions established among the Shona in the late 19th century were largely a result of the work of African evangelists. It can thus be argued that Basotho evangelists and other African evangelists were, to a greater extent, the ones who laid the ground for the establishment of mission stations among the Shona people and also ran some missions for a considerable period of time before the coming of European missionaries.

African evangelists also controlled the way the gospel was spread and played a pivotal role in the translation of the Bible. Using the Tswana case study, Volz argues that "although European missionaries introduced Christianity to Batswana, they had little control over the different ways that early Tswana converts perceived, adapted and proclaimed the new teaching".47 He further argues that whilst it was likely to simply accept the teaching of a white missionary, Christians under African evangelists were more independent and engaged in robust debate.48 Therefore, Africans were not just recipients of the Gospel, but active participants in its propagation through preaching, teaching and translating the Bible.

Furthermore, there is evidence to show that as early as the late 19th century, African evangelists already out-numbered white missionaries and played a crucial role in the northward expansion of Christianity.49 Consequently, it would be misleading to identify the spread of Christianity in Africa with just white missionaries or view white missionaries as propagators of the religion and Africans as mere recipients.

Settling in the mission field

Most of these Basotho and other African evangelists and their families settled permanently in Zimbabwe and continued to play a crucial role in the evangelisation of the communities around Morgenster Mission and a number of other centres. Gradually, Basotho began to coalesce in Fort Victoria district. Friends and relatives of the original Basotho evangelists continued to settle around Morgenster Mission.

It should be highlighted that although the core of this community was composed of those Basotho who had worked with the DRC, PEMS and the BMS at various levels and were pioneer missionaries in their own right, the community was also joined by other Africans from South Africa who had come there with the Pioneer Column in 1890. These Africans or "colonial natives", as they were called, included the Xhosa, the Zulu, the Mfengu, and the Basotho among others.50

Therefore, gradually, Basotho evangelists and their families were joined by other Basotho families, together with a few other non-Basotho Africans from South Africa. This led to the emergence of a community of African immigrants in Fort Victoria. In 1907, Jacob Molebaleng and three other Sothos purchased Erichsthal Farm in the Victoria district from the Posselt Family for £1000.51 The farm measured 14202 acres for £1000 and was located between the Shagashe and Mutirikwi rivers.52 It was owned in four equal, but undivided shares, which meant that they lived on the farm as a community rather than as individual private owners. The four owners of the farm were Jacob Molebaleng, Ernest Komo, Matthew Komo and Jona Mukula.53 The other group of Basotho bought Niekerk's Rust Farm which was located close to Harawe Hill in Ndanga District just a few kilometres from Erichsthal Farm. The farm originally belonged to Mr HC van Niekerk, but was later sold to WB Richards.54 Richards in turn sold the farm to Basotho immigrants who stayed on this farm until early 1930s.55 The farm was purchased in 1909 by Ephraim Morudu, together with nine other Basotho. The purchase price of the farm was £900 and it measured 3.249 acres.56 Like Erichsthal, Niekerk's Rust was owned in undivided shares; so, it was run more or less like a small village though the part owners had title deeds to the farm.

By 1924, there were about fifty adult Basotho men living on Erichsthal and Niekerk's Rust farms with their families. As the community grew, colonial officials began to discuss ways through which these "alien natives" could be administered. Unlike indigenous Africans, Basotho did not have any traditional authority, a factor which placed them on a very ambiguous position in the colonial set up. Some members of the community recognised that they needed to have their own traditional authority in order to fit into the schema of the colonial state. The Superintendent of Natives for Fort Victoria noted that Basotho "desired to have a recognised mouthpiece, through whom they may approach the government, and through whom notification of new legislation or government orders can be conveyed to them".57 After some deliberations and with the support of the Superintendent of Natives, Cornelius Magoba was appointed headman (or chief) of the Basotho community on the 1 October 1924.58 Unfortunately, Magoba died just ten days after his appointment and he was replaced by Jacob Molebaleng on the 1 April 1925.59 Jacob Molebaleng was given the title of chief or headman of the community and was addressed as such in many government correspondences.60 As the leader of the community, Jacob Molebaleng coordinated most of the activities of the community and made representations to colonial officials. The creation of a "customary authority" for Basotho was part of the colonial administration's way of dealing with the ambiguous position of Basotho as colonial subjects. Generally, all "natives" were supposed to be under some form of customary authority such as a chief so that they could be easily administered and monitored. However, as "alien natives", Basotho did not fall under any traditional authority in Victoria District hence the need to create one for them. This development caused a lot of discord within the community.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the evangelisation of the southern Shona was as much a result of the efforts of European missionaries as it was of those of African evangelists and lay preachers. It was often the African evangelists who, sojourned to the north of the Limpopo, first made initial contacts with the local communities. Although the histories of various missionary groups which carried out evangelical work in what later became Rhodesia in the late 19th century often celebrated the role played by the so-called pioneer missionaries, African evangelists were often indispensable in those early years. Apart from preaching to local communities, they also worked as teachers, interpreters, translators, clerks, and builders among other jobs. They thus mediated the process of evangelisation in a number of ways. In the end, it was a case of Africans evangelising other Africans rather than it being a purely European missionaries' enterprise. Hence, the history of the spread of Christianity among the southern Shona would not be complete without an examination of the role played by these African intermediaries.

Works consulted

Beach, DN. 1973. The initial impact of Christianity on the Shona: the Protestants and the Southern Shona, in Dachs, AJ. (ed.), Christianity south of the Zambezi. Gwelo: Mambo Press, 28-29. [ Links ]

Coillard, F. 1897. On the threshold of Central Africa: a record of twenty years' pioneering among the Barotsi of Upper Zambesi. London: Hodder & Staughton. [ Links ]

Coplan, DB. 1991. Fictions that save: migrants' performance and Basotho national culture. Cultural Anthropology 6(2), 164-192. [ Links ]

Couzens, T. 2003. Murder at Morija. Johannesburg: Random House. [ Links ]

Gray, R. 1990. Black Christians and white missionaries. New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Maloka, ET. 2004. Basotho and the mines: a social history of labour migrancy in Lesotho and South Africa c.1890-1940. Dakar: Codesria. [ Links ]

Mashingaidze, EK. 1978. Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward outreach: black evangelists and the missions' northern hinterland, 1869-1914. Mohlomi: Journal of Southern African Historical Studies 2, 5-27. [ Links ]

Mazarire, GC. 1999. A right to self-determination! Religion, protest and war in South-Central Zimbabwe: the case of Chivi District 1900-1980. MA dissertation, University of Zimbabwe, Harare. [ Links ]

Mutumburanzou, AR. et al. 1989. Ten years of development in Reformed Church in Zimbabwe 1977-1987. Masvingo: Morgenster Mission. [ Links ]

Ogbukalu, U. (ed.) 2005. African Christianity: an African story. Pretoria: Department of Church History. [ Links ]

Palmer, R. 1977. Land and racial domination in Rhodesia. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Ranger, TO. 1975. Introduction, in Ranger, TO. & Weller, J. (eds.), Themes in Christian history of Central Africa. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Roberts, RS. 1978. The settlers. Rhodesiana 39, 55-61. [ Links ]

Sayce, K. 1978. A town called Victoria or the rise and fall of the Thatched House Hotel. Bulawayo: Books of Rhodesia. [ Links ]

Shutt, AK. 1995. "We are best poor farmers": purchase area farmers and economic differentiation in Southern Rhodesia c. 1925-1980. PhD thesis. University of California, Los Angeles. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, WJ. 1981. From mission field to autonomous church in Zimbabwe. Transvaal: NG Kerkboehandel. [ Links ]

Van der Merwe, WJ. 1987. Kuvamba nokukura kwekereke yeReformed muZimbabwe (Reformed Church in Zimbabwe). Masvingo: Morgenster Mission. [ Links ]

Volz, S. 2008. Written on our hearts: Tswana Christians and the "word of God" in the mid-nineteenth century. Journal of Religion in Africa 38(2), 112-140. [ Links ]

Weller, J. & Linden, J. 1984. Mainstream Christianity to 1980 in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Gweru: Mambo Press. [ Links ]

1 Joseph Mujere is a Research Associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute (SWOP), University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

2 See U. Ogbukalu, (ed.) African Christianity: an African story, (Pretoria: Department of Church History, 2005).

3 J. Weller and J. Linden, Mainstream Christianity to 1980 in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, (Gweru: Mambo Press, 1984), p.27.

4 T. Couzens, Murder at Morija (Johannesburg: Random House 2003), p.91.

5 E.T. Maloka, Basotho and the mines: a social history of labour migrancy in Lesotho and South Africa c.1890-1940 (Dakar: Codesria, 2004), p.158.

6 D.B. Coplan, 'Fictions that save: Migrants' performance and Basotho National culture', Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 6, No. 2 (1991), p.164.

7 D.N. Beach, 'The initial impact of Christianity on the Shona: the Protestants and the Southern Shona' in A. J. Dachs (ed.) Christianity south of the Zambezi (Gwelo: Mambo Press, 1973), p.27.

8 Ibid, p.27.

9 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward outreach: Black evangelists and the missions' northern hinterland, 1869-1914', Mohlomi: Journal of Southern African Historical Studies, Vol. 2 (1978), p.68.

10 W.J. van der Merwe, From mission field to autonomous Church in Zimbabwe (Transvaal: N. G. Kerkboehandel, 1981), p.37.

11 G.C. Mazarire 'A right to self-determination! Religion, protest and war in South-Central Zimbabwe: The case of Chivi District 1900-1980' (M.A. in African History Thesis, History Department, University of Zimbabwe, June 1999), p. 19.

12 D.N. Beach, 'The initial impact of Christianity on the Shona: The Protestants and the southern Shona', p.28.

13 Ibid, p.28.

14 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward outreach: Black evangelists and the missions' northern hinterland, 1869-1914', p.68.

15 K. Sayce, A town called Victoria or The rise and fall of the Thatched House Hotel (Bulawayo: Books of Rhodesia, 1978), p.59.

16 W.J. der Merwe, From mission field to autonomous Church in Zimbabwe, p.37.

17 D.N. Beach, 'The initial impact of Christianity on the Shona: The protestants and the southern Shona', p.28.

18 Ibid, p.28.

19 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward outreach: Black evangelists and the missions' northern hinterland, 1869-1914', p.69.

20 Ibid.

21 Ibid, p. 70; see also F. Coillard, On the threshold of Central Africa: A record of twenty years' pioneering among the Barotsi of Upper Zambesi (London: Hodder and Staughton, 1897), p.xxviii.

22 J. Weller and J. Linden, Mainstream Christianity to 1980 in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, p26.

23 D.N. Beach, 'The initial Impact of Christianity on the Shona: The protestants and the Southern Shona', p.29.

24 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward outreach: Black evangelists and the missions' northern hinterland ,1869-1914', p.70.

25 W.J. van der Merwe, The day star arises in MaShonaland, p. 13.

26 D.N. Beach, 'The initial impact of Christianity on the Shona: The protestants and the southern Shona', p.31.

27 Ibid.

28 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward outreach: Black evangelists and the missions' northern hinterland ,1769-1914', p.73.

29 Ibid.

30 J. Weller and J. Linden, Mainstream Christianity to 1980 in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, p.27.

31 National Archives of Zimbabwe File (NAZ) Hist. Mss BE2/1/1 Diary of Knothe, Entry of 19 May 1777.

32 Ibid, p.32.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid, p.33.

35 W.J. van der Merwe, The day star arises in Mashonaland, p.13.

36 W.J. van der Merwe, Kuvamba nokukura kwekereke yeReformed muZimbabwe (Reformed Church in Zimbabwe) (Masvingo: Morgenster Mission, 1977), p.22.

37 A.R. Mutumburanzou et al., Ten years of development in reformed Church in Zimbabwe 1977-1987 (Masvingo: Morgenster Mission, 1989), p.4.

38 W. J. van der Merwe, From mission field to autonomous Church in Zimbabwe, p.52.

39 Ibid.

40 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward Outreach', p.80.

41 Ibid.

42 Ibid, p.81.

43 T.O. Ranger, 'Introduction', in T. O. Ranger and J. Weller, (eds.) Themes in Christian history of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1975), p.86.

44 E.K. Mashingaidze, 'Forgotten frontiersmen of Christianity's northward Outreach', p.78.

45 A number of these African evangelists had learnt the local languages during their early evangelisation missions across the Limpopo or when they went on hunting expeditions. Because of their knowledge of the local languages some of these evangelists also worked as interpreters for the missionaries.

46 D.N. Beach, 'The impact of Christianity on the Shona', p.25.

47 S. Volz, 'Written on our hearts: Tswana Christians and the "word of God" in the mid-nineteenth century' Journal of Religion in Africa Vol. 38, Vol 2 (2008), p.113.

48 Ibid.

49 R. Gray, Black Christians and white missionaries . New Haven, Yale University Press, 1990, p.16.

50 R.S. Roberts, 'The settlers' Rhodesiana, Vol. 39 (1977).

51 NAZ AT1/2/1/10 Land owned by Natives in 1924.

52 R. Palmer, Palmer, R. Land and racial domination in Rhodesia, London: Heinemann, 1977., p.270 (appendix II)., A. K. Shutt, '"We are best poor farmers": Purchase area farmers and economic differentiation in Southern Rhodesia c. 1924-1970', (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 1994).

53 NAZ S1042 Superintendent of Natives (Fort Victoria) to C. N. C, 20 December 1927, S1747 Distribution of Estate: Joseph and Johanna Komo (No Date).

54 NAZ S1442/F2/1 Superintended of Natives (Fort Victoria) to C. Bullock Assistant Chief Native Commissioner Salisbury, 2 August 1933.

55 Ibid.

56 R. Palmer, Land and racial domination in Rhodesia, p.270. Although the farm owners were generally viewed as Basotho there were some members like Jona Mukula who was a Hlengwe and Isaac Khumalo who was a Zulu or Ndebele.

57 NAZ S1461/10/7 The superintendent of natives Victoria to CNC 4 September 1924.

58 NAZ S1461/10/7 The superintendent of natives Victoria to CNC 1 October 1924. Magoba was also spelled as Maqula, Makola although the most appropriate spelling was Mmakola.

59 NAZ S1461/10/7 The superintendent of Natives Victoria to CNC 21 March 1924.

60 NAZ S924/G33/App.2 Superintendent of Natives (Fort Victoria) to CNC, 14 October 1927.