Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.43 no.2 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/at.v43i2.7438

ARTICLES

Inequalities within Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa on gender, with special reference to lGBTQIA+: Imago Dei

L. Modise

Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa. E-mail: modislj@unisa.ac.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7206-2698

ABSTRACT

This article consists of five sections on equality within faith communities. First, the focus is on the creation of human beings as the image of God on an equal basis. The premise is that LGBTQIA+ people are created as human beings in the image of God, deserving to be welcomed in faith communities. Secondly, the article focuses on how missionaries have taught African converts to interpret the Bible on many serious human rights issues. Thirdly, the article discusses the position of the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA), using the contents of the General Synods, spanning from Pietermaritzburg (2005) to Stellenbosch (2022). Fourthly, this study reflects on the challenges faced by denominations that accept LGBTQIA+ people regarding marriage and their ordination. The challenge seems to be about the fundamental reading of the Bible, confession, and Church Order articles, as discussed in this article. Fifthly, recommendations are made to address this inequality. This article is approached from an anthropological-missional viewpoint when addressing this inequality within communities of faith.

Keywords: Inequality, Gender, LGBTQIA+, Imago Dei

Trefwoorde: Ongelykheid, Geslag, LGBTQIA+, Imago Dei

1. INTRODUCTION

In this article, the researcher focuses on Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and all others (LGBTQIA+), using the origin of human beings as a point of departure to the entire argument. If the church, in general, and the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA), in particular, accept LGBTQIA+ as human beings, then the creation of human beings in the image of God is a primary source to define their existence. The biblical texts that influence decision makers to think otherwise about the acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people as members with full privileges and a right to marriage, baptism of their children, and ordination, are discussed from different perspectives.

Enns et al. (2013:798) limit the definition to homosexuality, depicting a sexual relationship between people of the same sex. LGBTQIA+ is more than homosexuality.

When introducing the concept of 'binary' we introduce the idea that when talking about sex and sexuality there are people who are not able to find themselves inside the box. Sex refers to the 'division of species into either male or female' and has a specific emphasis on reproductive functions. 'Intersex' is a general term used for a variety of embodied realities where a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not seem to fit the 'typical definition of female or male' (Boonzaaier & Van der Walt 2019:104).

Boonzaaier and Van der Walt (2019:104) provide a detailed definition of LGBTQIA+ in the sense that there are more sexes than two sexes (male and female), according to biomedical science and research illustrating that some people are intersex. Furthermore, they argue that, currently, the topic of sex, sexuality, gender, and sexual orientation forms part of a difficult conversation because of the stereotypes of traditional theologians such as Enns et al.'s definition who lock sex and sexuality into one box. The complexity of the conversation is specifically when it relates to marriage and ordination in URCSA. Boonzaaier and Van der Walt (2019) provide the participant in conversations and dialogues with a wide range of definitions to understand the embodied realities that exist within the LGBTQIA+. They further argue that the conversation on sexuality has a history of excluding some people from the conversation because of the experience of their bodies, which is different from those who engage from the dominant position (Boonzaaier & Van der Walt 2019).

This study focuses on the one-sided use of biblical texts to justify the marginalisation and exclusion of LGBTQIA+ people. The researcher focuses on URCSA and its decisions regarding LGBTQIA+ people by the policymaking Synods (General Synods). The General Synods, used as focal points for this discussion, range from the General Synod of Pietermaritzburg in KwaZulu-Natal in 2005 to the recent General Synod of Stellenbosch in the Western Cape in 2022. Recommendations of Regional Synods to these General Synods are discussed, as well as the decision of the General Synod of Stellenbosch. The cardinal argument of this article is that the right to be a member of a congregation guarantees all privileges and rights in that denomination. The assumption is that any denial of one right to members of the denomination who belong to the LGBTQIA+ community would amount to an inequality within that denomination.

2. PROBLEM STATEMENT

The main problem statement in this article is the marginalisation and exclusion of LGBTQIA+ people from society, in general, and the URCSA community, in particular, specifically in terms of marriage and ordination. URCSA has accepted LGBTQIA+ people as members of their community, as per Articles 1 and 3 of the Church Order, although marriage and ordination are reserved (URCSA 2005; 2008; 2012; 2016). According to Devenish et al. (1992:138-139),

[h]omosexuals generally will say that to choose a lifestyle that is viewed with hostility, threatened by arrest, discrimination, rejection by family, friends and excluded from religion and the mainstream of society is sheer lunacy.

Devenish et al. (1992) have written with limited information. That is why they use terms such as "choice" instead of "actualisation". LGBTQIA+ people are living their God-given lives as images of God, with the Spirit of God in them. Their exclusion from marriage and ordination, mentioned by Devenish et al. (1992), is still relevant in the 21st century regarding URCSA, even though URCSA accepts them as members of denominations in terms of Article 3 of the URCSA Church Order (Plaatjies-Van Huffel 2017:83). In the Acta of General Synod of URCSA, Punt (2008) indicates that this marginalisation and exclusion by URCSA are carelessly based on, and encouraged by a fundamental reading of specific biblical texts that seemingly refer to homosexuality, without observing other social ills referred to in the Bible (URCSA 2008:121). Mbiti (2018:20) contends that the fundamental reading of the biblical texts seems to be adopted from the Western missionary seminars that were producing technicians (ministers and evangelists) to maintain the Western epistemology, while ignoring the African ontology and biblical anthropology. Ssekabira (2018:85) locates human dignity, which is rooted in the image of God, within the context of the summary of the Decalogue regarding love for God and the neighbour. The reading, understanding, and application of a biblical text ought, therefore, to be in line with the commandment of love for God and God's image.

3. HUMAN BEINGS ARE CREATED AS EQUALS IN THE IMAGE OF GOD

According to the decision of the General Synod in 2005, URCSA is an African and Reformed Church. It is, therefore, important to start the argument on the creation of human beings from the African and Reformed perspective. Mbiti (1969) and Setiloane (1975) agree that the creation or origin of humankind is only known by God. However, every nation has its distinctive myths about the origin/s of humankind. Setiloane narrates that the Tswana people argue that they originate from Ntswana-tsatsi (where the sun rises - in the east), while the Basotho people originate from Tintibane or Thobega (from the bed of reeds). Both Tswana and Basotho people come from the one-sided agent of Modimo (God), known as Loowe (The first person). Mbiti (1969) argues that the African people were made of clay (in fact, different colours of clay), referring to the different colours of African people. Setiloane and Mbiti argue that human beings originate from one direction (Ntswana-Tsatsi and Tintibane - one source), clay. People, therefore, stand as equals before God and the ancestors. Similarly, LGBTQIA+ people come from the very same source or direction, namely Ntswana-Tsatsi and Tintibane, or clay, according to Mbiti. Hence, they deserve equal treatment. God is also the source and origin of these people.

With the arrival of Western missionaries in Africa, the concept of human origin changed to be more biblical; the image of God became the centre of the origin of humanity. According to the Bible, human beings were created from the dust of the earth, closer to Mbiti's understanding of human origin. However, the Bible proceeds to indicate that human beings are created in the image of God, which gives humankind dignity (Seriti, according to Setiloane [1975:4]).

The Reformed tradition holds that human beings are created in the image of God. This image is set in a human being's soul. Calvin (2008:106) argues that human beings are created in the image of God, as God's divine glory is evident in their physical appearance, while the proper seat of God's image is in the soul. The likeness of God, which is contained or made conspicuous by the outward marks, is spiritual. According to Calvin (2008), outward looks are not that important, but what is inside the human being, namely the Spirit of God, does not have gender. LGBTQIA+ people should, therefore, not be judged by their outward appearance, but by their inside, which is the image of God.

A similar argument is used by feminist and liberation theologians to push their arguments against women's exclusion in the church and society. Nirmal (2012:545), arguing from Dalit theology, points out the following:

For a Christian Dalit theology, it cannot be simply the gaining of rights, reservations, and privileges. The goal is the realization of our full humanness, or conversely, our full divinity, the ideal of the Imago Dei, the image of God in us.

For the LGBTQIA+ people as a marginalised and excluded group in both church and society - like the Dalit Christians in India - the same argument is valid. As human beings, their humanness needs to be realised in full because of the Spirit of God who lives in them.

Christianity has in its New Testament foundations, traditions that would affirm the equality of a woman in the image of God and the restoration of her full personhood in Christ. But even the primarily marginalized traditions that have affirmed this view through the centuries have not challenged the socioeconomic and legal subordination of women. Equality in Christ has been understood to apply to redeemed order beyond creation, to be realized in Heaven (Ruether 2012:377).

Whereas women in church and society have fought for their full personhood in Christ for centuries, the other layer of the struggle for full personhood and human dignity in the image of God is the LGBTQIA+ community. The same argument by the feminist theologians is still valid for the LGBTQIA+ people in their struggle to be accepted as full members of the church, and to receive full participation in ministry and marriage, without restrictions. The public good is what is natural to humanity, the context in which they should exercise their freedom to realise the image of God within themselves (Williams & Weigel 2012:789). Human rights and human dignity are linked to the image of God. Neither the church nor society can give a person limited rights of existence and membership because their dignity and human rights are rooted in the Imago Dei.

The critical question, however, is: If human beings reflect the image of God, how far do they bear this reflection of God? The fact is that, although human beings are God's image, God is only somehow (partially) knowable, yet incomprehensible. Berkhof (1939:29) indicates that the Christian church confesses that God is incomprehensible, even though he can be partially known, and that knowledge of God is an absolute requisite for salvation. The emphasis in Berkhof's argument is that human beings cannot have exhaustive and perfect knowledge of God. Grudem (1994:149) points out that God is infinite, while human beings are limited. They can, therefore, not fully understand God because God is said to be incomprehensible. This means that human beings cannot understand God fully or exhaustively (Grudem 1994:149). Paul also refers to the incomprehensibility of God: "No one comprehends the things of God except the Spirit of God" (1 Cor. 2:10). If human beings are reflecting the image of God, one can deduct from the argument above that they cannot be fully understood. LGBTQIA+ people as human beings are on the same level as other human beings; they also reflect the image of God. It is, therefore, not easy to fully understand the things of God. Understanding the things of God is revealed in the Holy Scriptures, as written in the 66 books of the Hebrew Testament (Old Testament) and Greek Testament (New Testament). These books were written within specific and different contexts, urging the necessary interpretation to understand God's intent with human beings. Currently, the African converts are still relying on Western theology to interpret God's actions.

4. TRADITIONAL MISSIONARY IMPACT ON THE INTERPRETATION OF BIBLICAL TEXTS IN AFRICA

In Africa, the traditional missionary teachings on the interpretation and translation of the biblical texts did not focus a great deal on how to convert people to Christianity; rather, on how to de-Africanise the converts. Mbiti (2018:20) argues that

Westernization in Africa started largely with the Western missionary movement in the 19th century and accelerated with colonization. It did not end with the demise of colonialism. It continued and accelerated thereafter, with African countries and societies paradoxically welcoming it and quietly reconciling it.

Missionary teaching about creation, reconciliation (soteriology), renewal, and consummation in Africa mostly did not focus on the importance of African people as the image of God. The focus on creation was more on natural resources than on human beings. Music was one of the methods used to teach African converts. The famous hymn that missionaries used and loved, "How great thou art", emphasises the natural environment and salvation without the importance of human dignity and the rights of African people. The other method used for conversion is a selective reading of the Bible that emphasises salvation and consummation. Mostly, salvation does not include liberation from poverty and oppression of the people of Africa, but rather a submissiveness to the Western missionaries. Consummation focuses on punishment (a theology of hell) without hope. The purpose of this section is to re-emphasise the reading of the Bible within its context, or from below (to understand the ramifications of the Bible better).

Vengeyi (2012) argues that the Bible is not simply a historical document about the Israelites. When one re-reads the Scriptures within the social context of people's struggle for humanity, one discovers that God communicates to human beings amid their troublesome situations. The divine Word is not an abstract proposition, but an event in human beings' lives, empowering them to continue their fight for full humanity. In line with this, Mbiti (1986) argues that the Bible should respond to the current challenges in African languages. He contends that the interpretation of the current context's struggle is the conscious point of departure of the colonial missionary method of reading and interpreting the Bible that borders real issues such as land dispossession, economic marginalisation, racism, and gender, among others, with which the African people are struggling. This includes the LGBTQIA+ community, which is also one of the recently bordered real issues with which African people are struggling from a biblical and contextual perspective.

It is obvious that the process of Bible translation is not an innocent and objective mission. In many instances, it is exposed to influences from sectional interests such as race, class, gender, and ideology (politics and culture). In addition, through translation and interpretation, the Bible has been an influential weapon to subjugate and blind the African people to accept many bondages in life, such as being slaves in their land. Many African scholars maintain that this same Bible should act as a weapon to liberate the oppressed African masses from the intentions of the translators. The Bible is not only the product and record of class, race, gender, and cultural struggles, but also the site and weapon of these struggles. The Bible is the place where and the means whereby many contemporary struggles are waged (Vengeyi 2012). Similarly, the Bible needs to address the incorporation of the LGBTQIA+ community on an equal level, just as it has addressed the bordered real issues of gender and race.

In 2019, I attended a consultative meeting with ministries of URCSA in Kempton Park, where the Southern Synod reported that, in their Regional Synod in Secunda (2018), they endorsed the General Synod's homosexuality policy and added that they have decided to marry and ordain LGBTQIA+ congregants. Those who identify as having a different view from the 2008 report requested URCSA to justify the Southern Synod decision. These are the tendencies of how biblical texts are used to prevent or defend certain positions regarding difficult conversations and challenging issues. I will focus on the misrepresentation of the biblical texts to justify the exclusion and marginalisation of LGBTQIA+ congregants, and the switch in the understanding of the biblical texts according to the context of the reader.

The contexts in which the biblical text originated (for example, the pre-exilic texts) may carry the same message but a different context, compared to the post-exilic period. One book, chapter, or verse could be interpreted to emphasise or condemn a particular behaviour, while the readers and implementers of that biblical text could choose not to apply it to all behaviours. Levites 18 acts as a good example. This chapter condemns different behaviours, including patriarchal-heterosexual people having sexual intercourse with people of the same sex. The point of departure is most probably Genesis 19, where the concept of sodomy, as thought to be equivalent to homosexuality, originated in the Bible.

The first biblical text that needs a fresh interpretation of homosexuality is Genesis 19. This text can be read with one of four lenses, namely xenophobia; gang rape; homosexuality, or gender-based violence, and femicide.

In this context, we read about evil heterosexual males living in the context of a hetero-patriarchal society, using their power and privilege to show their authority over strangers through sexual intercourse with them as if they were women. However, this action is interpreted as homosexuality, while the text intends to demonstrate the power of people in authority over strangers. The acts in the text are based more on unwelcoming strangers and arrogance than referring to homosexuality. Enns et al. (2013:797) point out that this narrative about the condemnation of homosexuality can be dismissed as a case of gang rape, whereby the power over strangers or foreigners is demonstrated in sexual terms. It is, therefore, not that easy to single out homosexuality, as the sin that destroyed Sodom and Gomorrah.

West et al. (2021:10-11) reread Genesis 18 and 19 from the contextual theology perspective to verify whether the text was intended to discourage or oppose LGBTQIA+ or any other social ills such as gender-based violence, rape, or femicide. They further linked Genesis 19 to Genesis 18 regarding hospitality within the Old Testament context.

A significant interpretive shift in a second version ('homosexuality-CBS2') was to include Genesis 18 in the CBS, re-reading Genesis 19 within its literary-narrative context of Genesis 18. Linking Genesis 18 and 19 provided significant capacity for a community-based conversation about 'homosexuality' by posing the question of whether Genesis 19 had anything at all to do with 'homosexuality'. Genesis 18, so clearly a narrative about Abraham's rural hospitality to three strangers, provided the narrative frame for recognising Genesis 19 as equally clearly the story of Lot's urban hospitality to two of these very same strangers (West et al. 2021:10-11).

The above argument empowers communities of faith to enter into conversation with a clear contextual reading of the text, to assist the communities to address the xenophobia that is a challenge in South Africa and globally regarding migrants.

Xenophobia and gang rape can also be identified as a sin that is detestable in the Old Testament era and currently. In the General Synod Agenda, in the homosexuality report to the General Synod of 2008, Punt (2008:100) indicates that

[c]loser reading of the story brings some other issues to light. Careful reading makes clear that Genesis 19 is not a condemnation of homosexuality as such, but rather of an attempt at rape by the male population of Sodom, whose greater majority in all probability was heterosexual.

The major sin in this context was, therefore, the breaking of the law of hospitality regarding strangers and of protection, which are central to the godly life in the Old Testament, rather than homosexual conduct. The work of West et al. (2021) sheds new light on the interpretation of Genesis 19 from a homosexual perspective to a hospitality perspective, which Boonzaaier and Van der Walt (2019) term "inclusivity".

If one reads Genesis 19 from the perspective of gender-based violence (the abuse of children and women) in church and society, it becomes clear that daughters were released for sexual abuse at the cost of male visitors. This raises the question of justice, equality, and human dignity. When we read this text in the context of gender-based violence in South Africa, homosexuality will be secondary in our interpretation of the text, while gender-based violence will be more in focus. Enns et al. (2013:797) question the act of releasing daughters at the expense of visitors in the current situation, contemplating whether Western or African parents would release their daughters for abuse, in order to maintain the honour of guests. They strongly believe that what this passage refers to about homosexuality also reflects outdated remnants of texts. Some denominations can misuse this text as they perceive that girls can be abused for sexual or commercial reasons. However, this is beyond the scope of this research. About Judges 19, Enns et al. (2013:797), as well as Punt (2008:100) in General Synod Agenda, discussing the report to the General Synod of 2008, claim that the acts of the men of Gibeah were not homosexual by nature, but rather violent sexual deeds, as in Genesis 19.

In his presentation to the Cape Synod conference in 2020 on "The church and gender with a focus on sexuality", Cezula illustrates how time and context change in terms of exclusion in the Old Testament era. His illustration was on Deuteronomy 23:1 and Isaiah 56:3-5, using Eunuchs as examples of exclusion in terms of nationality and Jewish law. According to Deuteronomy 23:1, eunuchs were not allowed to enter the synagogue, but in Isaiah 56:3-5, they were allowed to enter (URCSA 2022a). For a man to access the synagogue, he had to be an Israelite by birth, and in the position to reproduce (pro-create); otherwise, he had to be a proselyte by circumcision.

According to Old Testament sources, the challenge of eunuchs was their inability to participate in procreation, due to the misfunctioning of their reproductive organs. The Jewish males were neither eunuchs, nor slaves, and no Jew could make another Jew a slave or a eunuch. It was easy for the lawmakers of the time to make the law that did not allow eunuchs to enter the synagogue because Jewish males were not eunuchs. In Isaiah 39, the prophet warns the Jewish communities that this comfort zone would disappear in future, when the Jewish young men would go into exile and be made eunuchs. Hence, in Isaiah 56:3-4, Isaiah prophesies that eunuchs may enter the assembly of God. Exclusion is simple when eunuchs are foreigners, but once they are insiders, different laws apply. According to the transgender society, a eunuch refers to a specific gender about LGBTQIA+. Likewise, it is easy to exclude LGBTQIA+ people when they are outsiders, but once they are congregants in the house of the decision makers, the interpretation should be different or has to change, in order to accommodate them. In URCSA, whenever decisions are made, decision makers must understand that, one day, the eunuchs or LGBTQIA+ people will be in the house.

5. THE POSITION OF URCSA ON LGBQTIA+ PEOPLE FROM 2005 TO 2022 GENERAL SYNODS

URCSA has discussed the full acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people for 18 years. In 2005, URCSA had already taken a positive step to open this difficult conversation about LGBTQIA+ people applying to become part of denominations. Theologians have started writing and speaking openly about LGBTQIA+. This topic is controversial, as indicated in the introduction, and may divide URCSA. Still, the church acts very openly about it. Hence, Senokoane (2019:1) defines URCSA as an "impossible community". The position of URCSA on LGBTQIA+ is captured in Decision 90 of the General Synod held in Pietermaritzburg in 2005. The Synod confirmed that the Bible is the living Word of God and the primary source and norm for the moral debate about homosexuality:

a. Synod acknowledges the diversity of positions regarding homosexuality and pleads that differences be dealt with in a spirit of love, patience, tolerance and respect.

b. Synod confirms that homosexual people are members of the church through faith in Jesus Christ.

c. Synod rejects homophobia and any form of discrimination against homosexual persons.

d. Synod appeals to URCSA members to reach out with love and empathy to our homosexual brothers and sisters and embrace them as members of the body of Christ in our midst.

e. Synod acknowledges the appropriate civil rights of homosexual persons.

f. Synod emphasizes the importance of getting clarity about the theological and moral status of homosexual marriages or covenantal unions.

g. Synod emphasizes the importance of getting clarity about the ordination of practising homosexual persons in ministry.

h. Synod assigns the following tasks to the Moderamen:

i. Do an extensive study on Christian faith and homosexuality while taking into consideration the abovementioned principles (URCSA 2005).

These points energised URCSA to do comprehensive research on the LGBTQIA+ community, while scholars from different institutions of higher education contributed positively to producing a 69-page report that cuts across the theological subjects of Biblical Studies, Church History, Systematic Theology, Practical Theology, and Missiology. Despite the theological perspectives contained in that report, which was tabled at the General Synod of Hammanskraal in 2008, full acceptance of homosexual people was not approved. Hence, Davids (2020:301) remarks:

For the past fifteen years, the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa made policy decisions and compiled research document that investigates the SOGIESC [sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and sex characteristics] of LGBTQ people. The URCSA failed multiple times to affirm the full inclusion of LGBTQ people.

Davids (2020) argues, at the hand of Article 3 of the Church Order, that the only condition to be a member of URCSA is to believe in Christ - that is the only condition. No other conditions are stated. The policy states: "Synod confirms that homosexual people are members of the church through faith in Jesus Christ." The following are the privileges and rights for members, according to the URCSA Church Order: baptism; confirmation; marriage; be a member of the church council; study theology to become an ordained minister; ordination; bereavement, and burial.

All these privileges are for all people who confess Jesus as Lord and Saviour, according to Article 3 of the Church Order.

What Davids termed "the failure of URCSA to some members of URCSA", seemingly turned out to be a success because this policy directs debate, as the LGBTQIA+ community feels that URCSA has failed to fully include them into the church. The church does not regard it as a failure, as it has put systems in place to clear certain stereotypes and misunderstandings regarding the LGBTQIA+ community; hence, the process decision in the General Synod of Kopanong (Benoni) in 2016. The process decision is that the matter should be discussed at the Regional Synods, and then be referred to the congregations for informing them about the decision of the Synods. The challenge is whether URCSA is capacitated enough at all levels to handle such a difficult conversation.

6. THE CHALLENGE FOR FULL INCLUSION OF LGBTQIA+ MEMBERS IN OFFICES AND MARRIAGE IN URCSA

A number of factors contribute to the challenges for full inclusion of the LGBTQIA+ community in the offices of the church and marriage. This is still based on the confirmation that the Bible is the living Word of God, according to the policy:

Synod confirms that the Bible is the living Word of God and the primary source and norm for the moral debate about homosexuality (URCSA 2005).

This confirmation leads to the fundamental reading and interpretation of the Bible from a traditional missionary approach. In URCSA, being the impossible community that consists of different people from different cultures, context plays an important role in the acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people.

Bosch (1991) indicates that the individual's understanding of God's Word is conditioned by the following factors, namely a person's ecclesiastical tradition; personal context (sex, age, marital status, and education); social position (social class, profession, wealth, and environment), as well as personality and culture (world view and language). These factors play an important role in reading and interpreting the Bible to justify marriage as God instituted it for a man and a woman. Any other form of marriage should be measured in terms of the abovementioned factors. Added to this is the person's ecclesiastical tradition. How does a particular Christian tradition such as being Reformed or Lutheran view God's revelation and accept it as authority? The church's interpretation of God's Word within its specific tradition constitutes its frame of thought about an authentic marriage. In this sense, a person's church tradition makes it difficult to understand marriage from an LGBTQIA+ perspective.

Balswick and Balswick (2007:231) contend that the vast majority of Christians worldwide - only a few in Africa - believe that a homosexual orientation is not abominable, although homosexual behaviour is still regarded as repulsive. Some Christians are tolerant of monogamous homosexual expressions, but with the view that this is not what God initially intended. This Christian interpretation is also a challenge for most of URCSA's Regional Synods. They fail to understand how the church can solemnise the marriage of LGBTQIA+ couples. URCSA accepts LGBTQIA+ people as members because their homosexual orientation is not regarded as abominable. However, URCSA does not have theological grounds - no biblical justification - to solemnise a marriage. On the other hand, they are compelled by the Constitution of South Africa to marry everybody who wishes to be married. Hence, the Cape Synod has recommended that ministers of the Word and sacraments should listen to their conscience when they are requested to marry these people (URCSA 2022b:416-422).

The other challenge is the biblical texts about marriage, as intended by God. As a Reformed institution, URCSA is anchored on God's Word for its doctrinal teaching and for addressing social issues such as marriages of LGBTQIA+ people. The fact is that the biblical texts support the institution of marriage as intended by God. The Bible was written within a context where males were very powerful, while females and people with different abilities were regarded as less human. Although the Bible seemingly favours male and strong human beings, the church's interpretation should always focus on the text and context (Modise 1997). The challenges faced by the people of the Old and New Testament eras are different from the current challenges. The current era, therefore, needs a fresh interpretation of the biblical text as explained in both of these Testaments. The critical challenge for the church lies in the current changing context. For example, regarding the institution of marriage, compared to the times of the Church Fathers.

7. FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATION

7.1 Findings

This section presents the recommendations of the Regional Synods to the General Synod of 2022 at Stellenbosch.

7.1.1 Findings from the Cape Regional Synod

According to the agenda of the General Synod of 2022, in the report of the Cape Regional Synod, it was found that there were engagements on LGBTQIA+, during the recess from the General Synod of 2016, in the form of conferences and discussions in different synodical commissions. The report indicates that the Cape Synod has decided to follow the process decision of engagement, a discussion on all levels of the church within the jurisdiction of the Cape Synod, coupled with research on marriage and ordination before the church would decide on full inclusion (URCSA 2022b:416-422). The most important step taken by the Cape Synod is Decision 70 of the Cape Regional Synodical Commission of 2019:

• We encourage congregations and presbyteries to create safe spaces for dialogue and conversation, which should include LGBTQIA+ people.

• The ministry for doctrinal and current affairs should be tasked to guide and help the Synod to move forward on the biblical and theological appraisal of homosexuality, as expressed in Proposals 1 and 2 from the Regional Synod 2018 which can also include

• an appraisal of which theological and hermeneutical shifts helped the church in dealing with the issue of slavery and the position of women as resources for our dealing with the issue of homosexuality;

• a guideline for congregations on how to understand the Bible today; and

• a guideline for congregations on how to understand Scriptural authority today (URCSA 2022b:421).

7.1.2 Findings from the Free State and Lesotho Regional Synod

According to the report of the General Synod agenda, there was no report on homosexuality from the Free State and Lesotho Regional Synod (URCSA 2022b:416-422).

7.1.3 Findings from the KwaZulu-Natal Regional Synod

According to the report to the General Synod agenda, there was no report on homosexuality from the KwaZulu-Natal Regional Synod (URCSA 2022b).

7.1.4 Findings from the Namibia Regional Synod

According to the report to the General Synod agenda, three presbyteries did not discuss the matter, while one presbytery agreed on full inclusion, and the other one rejected full inclusion of LGBTQIA+ people into the church. The mixture of feelings and thoughts about LGBTQIA+ people in the Namibia Regional Synod might be influenced by the demography of the Regional Synod, which is rural and urban. The northern part of the Regional Synod is cultural and traditional in its way of doing things, while the southern part has a more rural and urban mentality, including places such as Windhoek and Katikura. This multidimensional Regional Synod, therefore, tends to make multidimensional decisions (URCSA 2022b:416, 476-477).

7.1.5 Findings from the Northern Regional Synod

According to the report to the General Synod agenda, there was no report on homosexuality from the Northern Regional Synod (URCSA 2022b).

7.1.6 Findings from the Phororo Regional Synod

According to the report to the General Synod agenda, there was a report on homosexuality from the Phororo Regional Synod, which shows that a workshop was held a month prior to the General Synod sitting in Stellenbosch (URCSA 2022b:416, 503-504).

7.1.7 Findings from the Southern Regional Synod

According to the report of the General Synod agenda, the Southern Regional Synod decided on the full inclusion of LGBTQIA+ members in the offices of the church and that its ministers should marry LGBTQIA+ couples (URCSA 2022b:416, 519-520). The Southern Synod was convinced by the report tabled during the General Synod in Hammanskraal in 2008.

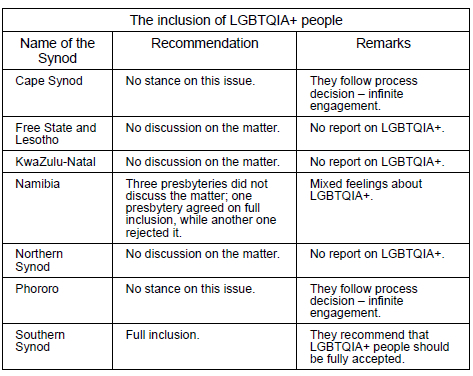

The following table summarises the recommendations from the seven Regional Synods of the URCSA on the inclusion of LGBTQIA+ people in denominations.

According to the analysis of the data provided above, 42.9 per cent of the Synods did not discuss the matter in their Regional Synods; 28.6 per cent discussed the matter at their Regional Synods, but they do not have a stance on the issue; 14.25 per cent have mixed feelings, while 14.25 per cent have decided on full acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people.

South Africa forms part of Africa with its culture and understanding of the Bible as authoritative in the African-Christian life. It was stated in the introduction that this topic is controversial and that it evokes difficult conversations. This finding was based on my observation and the report of the Namibia Regional Synod and cultural issues. Different biblical interpretations, coupled with cultural stereotypes, might contribute to the high percentage of Regional Synods that have negative or mixed thoughts on the LGBTQIA+ issue. The Namibia Regional Synod states in its report: "The large vacant congregations together with strong cultural views are the stumbling blocks in pursuing this discussion" (URCSA 2022b:416, 476-477).

LGBTQIA+ is a complex issue that needs resources ranging from human resources to financial resources. Capacity is the most needed in this regard in the Cape Synod, whereas the KwaZulu-Natal, Free State, and Lesotho Synods have financial constraints. A higher number of vacant congregations and cultural issues constrain an open conversation and formal engagement on all levels of the church.

8. CONCLUSION

The LGBTQIA+ community ought to be recognised as human beings created in the image of God before their rights can be discussed. I conclude this article by suggesting that theological anthropology should be the point of departure for a biblical interpretation of LGBTQIA+. URCSA finds itself in a dilemma where the acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community caused them to involuntarily reread and reinterpret the biblical texts anew, to have fresh theological grounds to allow LGBTQIA+ individuals to get married and be ordained. The article illustrated that there is a will to accept LBGTQIA+ fully, but there is no will to decide on a policy-level meeting. The Belhar Confession should be the guiding principle in empowering URCSA to fully accept LGBTQIA+ people. Finally, URCSA should allow its integrated ministries to discuss the matter and arrive at well-informed recommendations at the Synods.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Balswick, J.O. & Balswick, J.K. 2007. The family: A Christian perspective on the contemporary home. London: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Berkhof, L. 1939. Systematic theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Boonzaaier, M. & Van der Walt, C. 2019. Co-creating transformative spaces through dialogue: Inclusive and affirming ministries in partnership with the Faculty of Theology, Stellenbosch University. In: L.J. Claassens, C. van der Walt & F.O. Olojede (eds.), Teaching for change: Essays on pedagogy, gender and theology in Africa (Stellenbosch: SunPress), pp. 95-112. [ Links ]

Bosch, D.J. 1991. Transforming mission: Paradigm shift. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis books. [ Links ]

Calvin, J. 2008. John Calvin: Institutes of the Christian religion. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson. [ Links ]

Davids, H.R. 2020. Recognition of LGBTQ bodies in the Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa: An indecent proposal? Stellenbosch Theological Journal 6(4):301-317. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2020.v6n4.a12 [ Links ]

Enns, P., Longman III, T. & Strauss, M. 2013. The Baker Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker. [ Links ]

Devenish, C., Funnel, G. & Greathead, E. 1992. Responsible teenage sexuality. Pretoria: Academica. [ Links ]

Grudem, W. 1994 Systematic theology: An introduction to biblical doctrine. Amsterdam: Protestant Book Centre. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1969. African religions and philosophy. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 1986. Bible and theology in African Christianity. Nairobi: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mbiti, J.S. 2018. Translating the word. Equipping the disciples: Toward westernizing Bible translations into African languages. In: G.E. Lesmore & K. Jooseop (eds.), Conference on world mission and evangelism from Achimota to Arusha: An ecumenical journey of mission in Africa (Nairobi: Acton Publishers), pp. 18-25. [ Links ]

Modise, L.J. 1997. Feminist theology and masculine aspects of God's self-revelation in Scripture. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Polokwane: University of Limpopo. [ Links ]

Nirmal, A.P. 2012. Towards a Christian Dalit theology. In: W.T. Cavanaugh, J.W. Bailey & H.C. Craig (eds.), An Eerdmans reader in contemporary political theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans), pp. 537-552. [ Links ]

Plaatjes-Van Huffel, M. 2017. Acceptance, adoption, advocacy, reception and protestation: A chronology of the Belhar Confession. In: M. Plaatjies-Van Huffel & L. Modise (eds.), Belhar Confession: Embracing confession of faith for church and society (Stellenbosch: SunPress), pp. 1-96. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781928357599 [ Links ]

Punt, J. 2008. On homosexuality report in the Acta 2008 of Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa. Wellington: CLF Press. [ Links ]

Ruether, R.R. 2012. The new earth: Socioeconomic redemption from sexism. In: W.T. Cavanaugh, J.W. Bailey & H.C. Craig (eds.), An Eerdmans reader in contemporary political theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans), pp. 377- 393. [ Links ]

Senokoane, B.B. 2019. URCSA as an impossible community. Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 45(3). 13 pages. Pretoria: Unisa Press. https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6335 [ Links ]

Setiloane, G.M. 1975. The image of God among the Sotho-Tswana. Rotterdam: Balkema. [ Links ]

Ssekabira, V.K. 2018. Life with dignity from biblical perspective of divine creation. In: A. Karamanga (ed.), African Christian theology: Focus on human dignity (Nairobi: Acton Publishers), pp. 84-106. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) 2005. Acta of the General Synod. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) 2008. Acta of the General Synod. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) 2012. Acta of the General Synod. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) 2016. Acta of the General Synod. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) 2022a. Acta of the General Synod. [ Links ]

Uniting Reformed Church in Southern Africa (URCSA) 2022b. Agenda of the General Synod. [ Links ]

Vengeyi, O. 2012. The Bible in service of Pan-Africanism: The case of Dr Tafataona Mahoso's Pan-African biblical exegesis. In: M.R. Gunda & K. Kügler (eds.), The Bible and politics in Africa (Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press), pp. 81-114. [ Links ]

West, G., Zwane, S. & Van der Walt, C. 2021. From homosexuality to hospitality: From exclusion to inclusion: From Genesis 19 to Genesis 18. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa 168:5-23. [ Links ]

Williams, R. & Weigel, G. 2012. War and statecraft. In: W.T. Cavanaugh, J.W. Bailey & H.C. Craig (eds.), An Eerdmans reader in contemporary political theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans), pp. 787-800. [ Links ]

Date received: 28 June 2023

Date accepted: 27 September 2023

Date published: 13 December 2023