Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.43 n.2 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/at.v43i2.7791

ARTICLES

Shall we dance? Choreographing hospitality as key to interpersonal transformation

G.W. Marchinkowski

Research Fellow, Department Practical and Missional Theology, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: george@swuc.co.za; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3145-4342

ABSTRACT

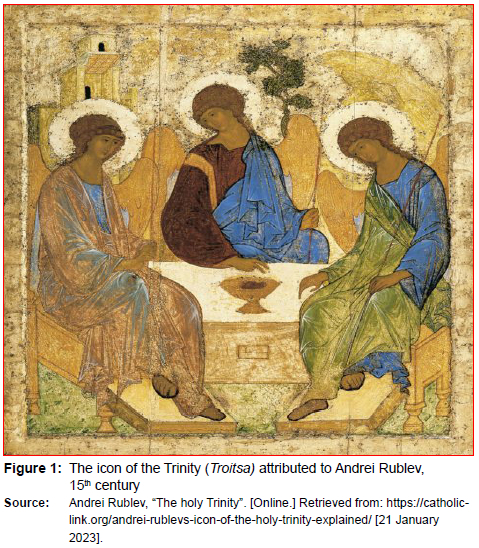

The icon of the Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev (1425) is a celebration of hospitality. This article contemplates the icon through Henri Nouwen's eyes, using his methodology, and shows how the spiritual practice of hospitality is key to interpersonal transformation. The article considers Nouwen's proposition that hospitality involved creating a space of true freedom in which the stranger can become a friend. It discusses Beatrice Bruteau's view that such a free space required a communion paradigm in interpersonal relations, before investigating Nouwen's unique metaphor for interpersonal transformation, a movement from hostility to hospitality. Finally, the article formulates principles for the spiritual practice of hospitality for ordinary people in everyday life, by considering the contributions of contemporary spiritual writers, Barbara Brown Taylor and Christine Pohl. Brown Taylor believes that the practice of hospitality began with paying attention, and Pohl warns against the challenges associated with its practice.

Keywords: Andrei Rublev, Henri Nouwen, Hospitality, Spiritual practice

Trefwoorde: Andrei Rublev, Henri Nouwen, Gasvryheid, Geestelike praktyk

1. "BIG MEN DO NOT DANCE": LIVING IN A HOSTILE WORLD

In a world of polarities, how will contemporary Christians find community? Examples of increasing distance between people and communities across the world abound. In the United States of America (USA), Donald Trump's presidency resulted in a wide gulf between liberal and conservative politicians, making bi-partisan consensus in Congress and society more difficult to achieve. In Europe, in recent years, right-wing political parties have captured the public imagination,1 in some instances experiencing massive growth in support. Russia's war on Ukraine has resulted in the political marginalisation of Russia on the world stage, entrenching negative attitudes in Russia toward the West. The continued conflict in Israel/Palestine has created an environment in which there is a reluctance to find common ground. The polarisation between the Muslim world and the secular West has intensified, especially after commitments about the education of women and girls in Afghanistan have not been honoured (British Broadcasting Corporation 2022).

In my own South African context, twenty-eight years of a new democratic era have not achieved the national unity and reconciliation which fired the great hope that propelled us into the general election of 1994. The looting of businesses and retail outlets in the winter of 2021 serves as a shocking reminder of the huge and widening gap between the "haves" and the "have-nots". The event caused huge anxiety among the middle class and wealthy about how quickly our society can devolve into a situation of utter lawlessness on such a wide scale. It served to create a distance between the classes. How will contemporary Christians face the challenges of our country and our world when we are so polarised? In this context of hostility, I will investigate Henri Nouwen's proposal that the Christian spiritual practice of hospitality is a means and a mechanism to create community among strangers which may transform individuals from a state of hostility to the joy of beloved community (see Herstein 2009:91-107).

2. PORTRAIT OF A DANCE: A WINDOW TO THE DIVINE

An icon is a gateway to the divine (Nouwen 1987:10) but it is also a powerful tool to conjure up memory. To illustrate this: The Catholic priest and author Henri Nouwen wrote about the connection between a Chagall painting that hung on the wall of his childhood home and the memory of his deceased mother. The sight of the painting could conjure up a flood of memories of her for him and, in so doing, become a source of consolation. In the glow of such consolation and with the aim of finding comfort in the Divine, Nouwen (1987:13) turned to icons:

By giving icons long and prayerful attention - talking about them, reading about them, but mostly just gazing at them in silence - I have gradually come to know them by heart. I see them now whether they are physically present or not. I have memorized them as I have memorized the Our Father and the Hail Mary, and I pray with them wherever I go.

Nouwen adopted the practice of gazing,2 a Byzantine discipline, in which he gave his complete attention to the visual medium, tried to see with his heart, and in the process was drawn into a mystical embrace wherein God communicated God's love (Nouwen 1987:14). In this article, I use the motif of a dance to describe the interplay between hospitality and the mystical embrace into which humanity is invited. The dance is appropriate first, because hospitality involves at least two partners, engaged in reciprocal activity which may turn out to be something beautiful for all. I will explain that the motif of the dance may also express the inner relationship of the Trinity.

Icons are often difficult to understand and sometimes even jarring to look at. They may include obscure geometric shapes and dark colours. They may not immediately make sense and may not even be aesthetically pleasing, with elongated characters and stern expressions. It may take time to uncover their beauty and meaning but as one gazes at them, in a prayerful disposition, icons begin to communicate their truth. Nouwen believed that icons communicated more with the Spirit than with the five senses. What was most significant was that icons could offer access to God's inner life. Behind the icon's two-dimensional surface lay "the garden of God, which is beyond dimension or size" (Nouwen 1987:15).

2.1 Rublev's icon: In Mamre, an act of basic hospitality

The story of Abraham, Sarah and the visitors at Mamre is an ancient story of hospitality. Three strangers arrived at the place where Abraham was encamped "near the great trees of Mamre" (Gen. 18:1 [NIV]). Abraham saw them, and even though they were strangers, unknown and unrelated to him, he responded with warm and generous hospitality. It was the oriental way. He hurried out to greet them, treating them "as God-sent" (Kamperidis 1990:5), and invited them into his home and his company, to share a meal. He offered them an experience of basic decency but ended up producing a lavish meal. First, water was brought for washing, and a shady place was offered for the guests to rest in the heat of the day. Bread was baked and a young calf was prepared for eating. All this was served with curds and milk. The strangers accepted the hospitality and perhaps in gratitude, as a reciprocal gift, they offered their hosts some good news - a prophecy about the birth of a son. After the meal, they left because they had other business and, besides, Abraham did not want to delay them.

The story is simple, of a kind often repeated in these ancient communities. (Kamperidis 1990:5). Hospitality was widely accepted in antiquity as an "important sign of civilization" (Richard 2000:5). In this case, however, the text identifies the three visitors as "the LORD", and therefore, the story takes on a deeper mystical meaning because it has become a story about the Jewish God (perhaps the Christian Trinity) visiting with humanity, being invited into a human home (Richard 2000:11) and, in an ultimate "turning of tables", Divinity received hospitality from human hosts. Kamperidis (1990:6) explains the profound mystical event as follows:

The Godhead is received as a guest in his own home, and clad in corruptible form, partakes of the food that will be transformed, through his own extension of hospitality, into incorruptible nourishment, his own flesh and blood, distributed symbolically to the whole hospitable domain of his creation.

It seems that Abraham had entertained angels without knowing it (Heb. 13:2b [NIV]). At its core, the story has all the hallmarks of ancient hospitality: A shared meal, honouring the stranger, and accepting the outsider.

2.2 Shall we dance? An invitation to venture deeper

Andrei Rublev chose this story as the subject of his famous and revered icon.3He "wrote"4 a table on which there was a chalice or a cup. The three visitors were arranged around it. The tree above the second guest, in the centre, was reminiscent of those great oak trees at Mamre (Reimer 2008:170). There they sat, enjoying the hospitality of Abraham and Sarah. It is interesting to note all the elements of the Genesis story that Rublev omitted from his icon: there was no food on the table, no Abraham or Sarah. "All that is left are the three angels, the table, the Eucharistic chalice, the oak of Mamre, the house and the rocks" (Lazarev 1996:96). At this first level of interpretation, one can observe what Rublev included and what he did not. The absence, in the icon, of Abraham and Sarah invites a deeper contemplation.

At another level, Rublev seemed to "write" the unknown guests as the Holy Trinity. (Reimer 2008:170; Evdokimov 1990:246) The characters around the table were set in an eternal moment of solitude (Evdokimov 1990:247; Reimer 2008:174), in which all movements were frozen and there was a sense of deep, quiet peace and calmness (Reimer 2008:171; Strezova 2014:197). The guests looked neither male nor female, with slender, elongated bodies (Evdokimov 1990:247; Lazarev 1996:98) of equal standing (Voloshinov 1999:110) but each guest looked different, unique (Evdokimov 1990:248). The two on the right inclined their heads toward the first character on the left who, in turn, faced the central character. If they are the persons of the Trinity, then identifying who is who is a challenge.5 Some scholars argue that the central character is the Father (Strezova 2014:194-195) and that the Son sits to the Father's right, as in the Creed, while the Spirit sits to the Father's left. They point to clues in the icon which assist in identifying the characters. Each character has a sceptre that points somewhere. One view is that Christ's sceptre (left) points to the body of Christ, the Church, whereas the Father's sceptre (centre) points to the tree of life, as Creator, while the Spirit's sceptre points to the rocks, traditionally a symbol of ecstasy and contemplation (Evdokimov 1990:249). Another school of thought regards Christ as the central character (Lazarev 1996:97) with the Father (Ouspensky & Kossky 1982:202) coming first on the left and the Spirit on the right (Ouspensky & Kossky 1982:202; Reimer 2008:172). The colours are also symbolically revealing. The Father's outfit is pale and indefinite since no one has ever seen the Father, which makes the Father difficult to describe (Evdokimov 1990:256; Strezova 2014:196). The Son, however, is depicted in bold colours, maroon (or dark crimson) for his humanity and blue for his divinity (Quenot 1991:114-115; Evdokimov 1990:256; Strezova 2014:196).

The Spirit's green robes symbolise fullness of life and renewed growth (Ouspensky & Lossky 1982:202; Strezova 2014:196). The characters were connected in a circle (Evdokimov 1990:251) of movement (Quenot 1991:105; Reimer 2008:172; Strezova 2014:197), conjuring up visions of a perichoretic dance6 (Reimer 2008:174), "which if sped up will blur the distinctions between them" (Strezova 2014:197).

The circular movement signifies that God remains identical with Himself, that He envelops in synthesis the intermediate parts and extremities, which are at the same time containers and contained, and He recalls to Himself all that has gone forth from Him (Dionysius the Areopagite, quoted in Ouspensky & Lossky 1982:202).

If the strangers are the persons of the Trinity, then a more mysterious dance is happening in this instance - perhaps the everlasting dance within the very inner life of God?

2.3 A shared meal at the centre

No observer can deny that Eucharistic imagery pervades (Reimer 2008:168; Kamperidis 1990:7). Is the Eucharist not the ritualised meal, the offer of divine hospitality, in which Christians repeatedly remember7 that community between human and divine was accomplished by an act of self-giving love? Spiritual transformation and the establishment of beloved community is celebrated in the Eucharist, a meal, a hospitality event (Louw 2019:4). The cup on the table, the shape of the cup made up by the inner outlines of the angels, and the shape of the cup made up by the outer contours of the angels and seats (Voloshinov 1999:110) saturate the icon with eucharistic imagery and extends the hospitality motif from Mamre to Calvary, to the experience of God's hospitality in the sacrament and, ultimately, to the inner communal life of God.

The tree of Mamre becomes the tree of life; the house of Abraham becomes the dwelling place of God-with-us, and the mountain becomes the spiritual heights of prayer and contemplation (Nouwen 1987:21). How the story has been transformed! An act of human hospitality is turned around, transformed into the supreme gracious act of divine hospitality.8

There is more: Rublev painted the table as open. There is space and an implicit invitation to those who gaze upon the icon to attend and participate in the perichoretic dance (Louw 2019:1), the most mysterious inner life of God.

The artist has created a space that enfolds, yet permits discernment. Hence, this icon makes room for the observer, and offers hospitality to him as a fourth guest (Strezova 2014:201).

Rublev is inviting the contemplator into a mystical experience in which she is coaxed forward to attend the table (Louw 2019:1) and, by so doing, enter into eternity, and experience the embrace that exists at the centre of God's life (Reimer 2008:171).

3. HOSPITALITY AS ACCESS TO INTERPERSONAL TRANSFORMATION

Contemplation on the icon raises an important question: Is it possible that an act of hospitality or a sustained commitment to the human spiritual practice of hospitality might result in a reciprocal mystical act of hospitality on the part of God? Is it possible that practising such a spiritual practice might facilitate access to, or consciousness of a greater and deeper phenomenon, the continuous and eternal invitation of God who seems to want to share God's self with us? Is hospitality transformative? Are we continuously invited into the perichoretic dance of love, the inner life of God? Does an act of hospitality on Abraham and Sarah's part, directed at perfect strangers, result in a mystical invitation on the part of the Trinity to participate in the perichoretic inner life of God?

In his contemplation on Rublev's icon, Nouwen points out that the road to participation, accepting God's invitation to attend the table and to dance in the divine life, is neither simple nor easy. The small cavity that can be seen on the open front of the altar table is the place where traditionally the bones of the martyrs were kept. This illustrates that the road to mystical union is paved with suffering, as spiritual seekers are called to carry their own cross as Christ carried his. But martyrdom is, after all, a witness to God's love. As spiritual seekers give up their lives, pouring them out kenotically for the stranger, they are enveloped in the house of love where no one is any longer a stranger (Nouwen 1987:25-26).

3.1 Dancing with strangers?

In his book, Reaching out, Nouwen describes three transitions, three movements toward spiritual wholeness. The second of these describes a movement toward the other (the stranger), a step toward interpersonal transformation. Nouwen calls this the movement from hostility to hospitality.

Nouwen began his study of interpersonal transformation by observing that, from the perspective of individuals in the West, the world seemed full of strangers, people estranged from their own history and culture but who also lived alienated from their neighbours, friends, and family. This alienation was not simply a utilitarian matter, it extended to their own deepest sense of self (Nouwen 1975:65). It is not hard to find evidence of such a pandemic of hostility in contemporary society. The introduction to this article lists some of the contemporary alienations which threaten to drag individuals, communities, and nations into hostile postures, possibly resulting in violence and war. Another experience of such a reality can be added. As a stranger in the USA, the author observed the run-off elections in Georgia in the winter of 2022, when a seat in the US Senate was being contested. The television commercials9screened in the week of the election were polarising at best and openly hostile at worst. What could possibly emerge from such a dehumanising campaign other than polarisation and hostility?

Might Christians offer an open, safe, and hospitable space in such a context? Nouwen proposes the Dutch word for hospitality, gastvrijheid (literally "offering the guest freedom") as an illustration of the necessity of freedom for/ of the guest in hospitality.

Hospitality, therefore, means primarily the creation of a free space where the stranger can enter and become a friend instead of an enemy. (Nouwen 1975:71).

This may sound simpler than it turns out to be. An act of hospitality is not a space in which the guest should be manipulated into thinking like the host or into adopting the host's world view. Surely, that would be a form of torture? Rather, hospitality (like dancing) should be a free space (Pohl 1999:13) in which the guests are safe to be themselves within the generous hospitality of the host. It is not easy to get our heads around this concept because we are so well practised in a "no free lunch" culture that always requires something (even subconsciously) in exchange for our hospitality (Nouwen 1975:72).

An inviolable rule of the hospitality offered to strangers is to accept them unconditionally. No questions concerning their origins or their station in life are permitted, and nothing is expected in return (Kamperidis 1990:5).

Both the Hebrew and the Christian scriptures contain numerous examples of incidences where acts of hospitality yielded unexpected consequences. Two examples are the Widow of Zarephath in 1 Kings 17:7-16 [NIV] and the pilgrims to Emmaus in Luke 24:13-35 [NIV]. Nouwen (1975:67) believed that a concrete action of welcoming the stranger but also a deep world view change from being hostile to the stranger to being hospitable was required. But the act (or practice) of hospitality also needed to be accompanied by personal solitude, lest the hosts perpetrate their psychological wounds on their guests (Nouwen 1975:102). This was a kenotic action in which hosts became less fearful and defensive and more open to strangers and their world (Nouwen 1975:108-109). The movement from hostility to hospitality also involves a renewed world view in which hosts view life as a gift that was not theirs exclusively but for sharing with others (Nouwen 1975:109).

Real hospitality is not exclusive but inclusive, requires a radical openness, and creates space for a wide range of human experience (Nouwen 2010:91).

As a result of his movement away from hostility toward hospitality, Nouwen's own understanding of community expanded from the safe, familiar place of belonging in The Netherlands to a far more open and inclusive space:

I came from a Dutch Catholic family where it was clear who we were and who they were. They were all non-Catholics. They were nonbelievers. They got divorced, or were gay. While we were okay because we believed the right teachings and lived a moral life. My family, my community, my seminary, and my church felt very safe and secure because the patterns and expectations were so clearly defined. Gradually, while I was teaching at Yale and Harvard, my fences (and defences) began falling away ... When I arrived at L'Arche, bang, bang, bang, my whole worldview crumbled (Nouwen 2010:92-93).

One can appreciate how difficult such a radical world view change could be, but one can also conjecture how freeing. For Nouwen, the beloved community he discovered became a place of forgiveness and celebration, in which human similarity was now far more apparent and compelling than difference (Nouwen 2010:93).

Hospitality performs a transformation of the way one thinks. Hospitality questions one's ways of thinking about oneself and the other as belonging to different spheres; it breaks down categories that isolate. Hospitality decentres our perspective, my story counts but so does the story of the other. In hospitality, the stranger comes vulnerable, not at home, often in need of sustenance and shelter. To welcome the other means the willingness to enter the world of the other, to let the other tell his or her story. So listening becomes a basic attitude of hospitality (Richard 2000:12).

4. "DANCING" AS UNLEARNING DOMINATION AND EMBRACING COMMUNION

Since hospitality is seemingly a key to interpersonal transformation, it is important to investigate the deeper dynamics at play when one changes one's approach to others from a hostile domination-oriented paradigm to a hospitable, community-building one. Rublev's icon invites those who gaze on it into a mysterious embrace and Nouwen clarifies that those who wish to step over the threshold and into the divine life are on the brink of interpersonal transformation. The Christian philosopher and pioneer of interspirituality, Beatrice Bruteau (Bourgeault 2014), explores the dynamics of such spiritual transformation that takes place when this transition is made.

Bruteau (1980: 123) believes that reaching out to the other has the potential to facilitate a personal and interpersonal transformation in the person exercising such a practice. The key for Bruteau (1980:124), writing to a Christian audience, was that spiritual pilgrims would consider the significance both of their being "in Christ" and other human beings being "in Christ" and how this might facilitate a deeply spiritual connection or unity. She then links this to the hard spiritual work of confronting power relations within the human person. Bruteau proposes that a shift in self-identity or the embrace of being a "new creation" necessitates a movement away from the "domination paradigm" toward a "communion paradigm". She explores the role of freedom in interpersonal power relationships, and to illustrate, she narrates the story of Jesus and his use of hospitality in the well-known biblical story of the Last Supper.

Jesus begins his destructive and creative action by washing the feet of his companions. This is a menial task ordinarily performed by a servant. For Jesus, the master, to execute this function is a shocking reversal of the proper roles of the Rabbi and his disciples, or servants. What makes it so shocking is that it concretises an inversion of the social relations that themselves reflect what we may call the metaphysical relations of the beings involved.

In a world structured by the domination, or lordship, paradigm, foot washing is a non-reciprocal relation. Servants wash the feet of their lords. Lords do not wash the feet of their servants (Bruteau 1980:125).

The level of investment that the human race has made in the domination paradigm is evident from Bruteau's interpretation of the Last Supper narrative. This is illustrated by the vehemence with which Peter resists the reversal Jesus has introduced (Bruteau 1980:125). Jesus had to make an ultimatum to reorientate Peter. Unless Peter allowed the domination world view to be destroyed, he could not embrace the new dispensation that Jesus was introducing. Only when Jesus turned the prevailing social structure upside down, thereby inverting the relationship between Peter and himself, could the new way of seeing things (relating to each other) be properly understood. Jesus explained the change in simple terms:

Do you realise what I have done? The one who is supposed to be lord has washed the feet of those who are supposed to be servants. My intention is to transform your whole world. I will no longer call you servants but friends (Bruteau 1980:125).

The Last Supper narrative reveals an entirely different paradigm of interpersonal relationship, an exploration of what true hospitality and true love for the stranger is. Jesus is modelling this with his close friends but as the community of faith grows, the same will have to be modelled with people who are truly unknown to each other.

The work of the Messiah, a true revolutionary, is showcased as he systematically exposes the prevailing world order based on domination and seeks to replace it with a new model of human and divine/human relationships. He does this by introducing a ritual, an eternally repeatable spiritual practice which has become known as Holy Communion or the Eucharist.

Jesus shares his own life substance and energy with his friends in this simple everyday ritual. In doing so, he introduces the prospect that life can be experienced more fully and deeply, even abundantly, if the new communion paradigm he is illustrating is embraced. He makes a contribution to such a future by giving himself as nourishment into their lives. At the start of the story, he creates a new set of personal relational dynamics and now, in the meal, he ritualises these principles in an embodiment of self-giving. What remains is for his followers to integrate this vision, to appreciate its great consequences, and to devise ways of putting it into practice in an uncompromising way. This subversive task will underly the declaration of the Good news of the coming of God's kingdom (Bruteau 1980:126).

Bruteau (1980:128) believes that

the difference between domination and communion is not merely of moral attitudes in which sympathy and generosity replace pride and selfishness.

Rather, it is a mutual and reciprocal relationship in which strangers may become friends, deeply connected, symbiotically tied for the sake of the enhancement of being. Persons are "in" one another, not "outside" or "other". It is, therefore, self-destructive to consider the other as alien or outside (Bruteau 1980:128-129). A reciprocal relationship of communion and being "in" one another produces unity, a deeper and different kind of unity. It is a unity that arises from the most basic spiritual centre of humanity and a connection facilitated by Christ's salvific and restorative work (Bruteau 1980:129).

Bruteau points to the Trinity as the ultimate example of this unity, an archetype of the many and the one. The inner life of God showcases the intention and the outcome of hospitality. In the Trinity, the three persons are described as freely choosing to give themselves to one another in such a way that results in an eternal and permanent interchange of energy and movement that constitutes their unity in one being. Theologians call this the perichoresis or circumincession of the three persons of the Trinity, in which they live and relate to each other "where each is, not a static being, but a living process of further life-donation" (Bruteau 1980:141).

The perichoresis is a theological (and contemplative) picture of God's inner life. This picture is powerfully descriptive of the ultimate outcome of hospitality. A primary and eternal act of hospitality on the part of one member of the Trinity meets with a warm and hospitable reciprocal response on the part of another and what emerges is a dynamic, powerful, and eternal movement10that continually communicates life.

And since each Person becomes most truly the self that Person is by performing this characteristic act of giving self-life to the other Persons, the sporadic act of self donation has the unique property of creating simultaneously both unity and differentiation (Bruteau 1980:141-142).

The contribution of Bruteau was to elucidate the mechanics of hospitality while not even using the word! Using the well-known Christian narrative of the Last Supper, she pointed to the subversive and revolutionary work of Jesus in destroying the prevailing domination world view which characterises human relations and replacing it with a communion paradigm with hospitality at its core. Having pointed this out, Bruteau does what Rublev also accomplished with his icon. She connects hospitality and its paradigm with the inner life of the divine. Having traced the mechanics of hospitality and having connected it with the inner life of the divine, let us now make some practical suggestions for how hospitality might be practised in everyday life.

5. CHOREOGRAPHING HOSPITALITY AS A SPIRITUAL PRACTICE IN EVERYDAY LIFE

In discussing Rublev's Trinity icon, Kamperidis (1990:5) begins with a story of simple and practical hospitality:

In my childhood, at Christmas dinners, a place was always reserved for the stranger and the wayfarer. A few days later, on New Year's Eve, a slice of St Basil's bread was set aside for the stranger. Even if not physically present, a stranger occupied a special place in the household. In case he or she materialized, usually brought by a friend, the stranger would be treated as a member of the family and entertained in a most cordial way.

Similarly, Volf (2002:245-263) offers a memory from his childhood, an expression of hospitality to a stranger on the part of his parents, to illustrate the dialogical relationship between beliefs and practices. He connects the practice of the sacrament of Holy Communion with a family meal into which a stranger is invited and shown how his parents' belief about Holy Communion shaped their practice of hospitality.

By giving generously of what has been bestowed on us to the stranger, by sharing the fruits of the earth, we render to God our thanksgiving for what has been generously offered to us (Kamperidis 1990:5).

In a previous article, I argued, on the basis of Michel de Certeau's writing, that

the Christian faith is, at its core neither an institution nor a set of doctrines and beliefs but rather an open, yet reproducible, set of practices (Marchinkowski 2022:5).

De Certeau changed the location of mysticism by proposing that mysticism is social and not personal and interior. It affects and transforms the world, while belonging not to the decision-makers of the world but to ordinary people who practise it in simple, everyday practices such as dancing, for instance (Marchinkowski 2022:5).

The spiritual dance of hospitality discussed in this instance should, therefore, be understood in the context of the ordinary and everyday albeit with a transcendent, mystical quality.

5.1 The mechanics of the practice in everyday life

In her exploration of hospitality as a spiritual practice in everyday life, Brown Taylor (2009:94) connects it with the so-called greatest commandment:

At its most basic level, the everyday practice of being with other people is the practice of loving neighbor as the self.

She then gives simple practical advice on how to practise it in everyday life and in ordinary ways. She suggests that we start with a very simple practice: to notice strangers. Individuals who pass us by, usually unnoticed, may become the focus of our practice of hospitality. Spiritual practitioners can focus on these everyday strangers by simply and deliberately noticing them, considering who they might be outside the present interaction and by appreciating them and what they are doing. An expression of affirmation crowns the spiritual practice. This is the simplest form of hospitality.

Brown Taylor (2009:95) warns her readers of a sense of inner resistance to the practice and counsels that the practitioner may come up with all kinds of reasons such as time pressure or innate hostility for not carrying through with it. Our inner xenophobia (fear of the stranger) may be so much stronger than our inner philoxenia (love for the stranger or "hospitality"), but when practitioners remember that they have at some time been strangers themselves, it might provide the requisite motivation to carry through.

Importantly, Brown Taylor opines that the actual nature of the encounter is not as important as the need for the practitioner to treat it as holy, sacred, and practised in the presence of the divine. Such an encounter might well turn out to be transformative for one or both parties involved (Brown Taylor 2009:104).

The assignment is to get over yourself. The assignment is to ... love the neighbor you also did not make up as if the person were your own strange and peculiar self (Brown Taylor 2009:105).

5.2 Locating hospitality in a home

Pohl makes the important connection between the spiritual practice of hospitality and the space called "home". She reminds her readers that, in the practice of hospitality, strangers are invited into the home of their hosts (Pohl 1999:150). In contemporary Western culture, this involves overcoming barriers of privacy and concerns about safety, including many personal and communal commitments. In the home, the stranger may feel safe and welcome and may even become a friend. The home need not be luxurious or elaborate - for Abraham and Sarah, their home was a tent. Pohl (1999:152) lists some characteristics of hospitable places, including "comfortable and lived in", "people are flourishing", "cared for", "shelter and sanctuary", "safe and stable", where "life is celebrated" and then, significantly, she agrees with Nouwen: "Hospitable places are alive with particular commitments and practices; however, guests are not coerced into sharing them." (Pohl 1999:153).

5.3 Dancing is not easy: Challenges faced in the practice of hospitality

Pohl (1999:127) cautions her readers of the challenges and limitations experienced by practitioners of hospitality. It may be valuable to take note of these so that perceived failure in being able to render hospitality may not result in disappointment and reluctance to persevere. One of the most experienced challenges is, of course, limited resources. Practitioners And it hard to deny hospitality even when faced with challenges of capacity. This is often because of the perceived link between human hospitality, which relies on limited resources, and divine hospitality, where resources are infinite. Failure to deliver may feel devastating (Pohl 1999:129).

In offering hospitality, practitioners live between the vision of God's kingdom in which there is enough, even abundance, and the hard realities of human life in which doors are closed and locked, and some needy people are turned away or left outside (Pohl 1999:131).

There are other challenges to be faced. The link in Western culture of hospitality with entertainment and commerce has resulted in the spiritual practice being undervalued or misunderstood. Some would much rather invite a stranger to a commercial place of hospitality than into their own homes. Guests may misunderstand the motives of those who would pay for them to receive hospitality from hotels or restaurants as being held at arm's length rather than embraced within a human home. The value of privacy has meant that people are reluctant to invite the stranger into their safe and cloistered homes. Finally, the misuse of hospitality as a means of manipulating the guests, of persuading them to be like the host or adopt the host's values or choices is also a profoundly important temptation to confront. A safe space is always a free space, where the guests are free to be truly themselves.

6. SHALL WE DANCE?

This article began with the exploration of a visual expression of hospitality. An icon is a picture, sometimes beautiful and sometimes not, but it offers a window into the divine life. Rublev's icon of the Holy Trinity is a showcase of hospitality in motion and in flight. Hospitality pervades the narrative from the simple and typical Middle Eastern story of Sarah and Abraham who welcomed three strangers without fear and apprehension, providing shelter, and serving them a meal, to the grand invitation of the icon to participate in the inner dance of love at the centre of the Godhead.

Nouwen was the initial guide, as the reader gazed on the icon and explored his methodology. The three strangers became the Trinity, God in the motion of a perichoretic dance of love, and the serendipity was that humanity was invited into this dance. This article illustrated the proposition that hospitality, a human spiritual practice, is a key to interpersonal transformation because it is reciprocated and fulfilled by a divine act of hospitality.

Before examining the practical side of the spiritual practice, this article explored Bruteau's examination of the physics of Jesus' actions at the occasion of the Last Supper, introducing hospitality as an antidote to dominant power relations. Communion replaced the prevailing domination paradigm of interpersonal relationships.

Hospitality involves an action, reaching out and creating a free space for the stranger to become a friend and may result in interpersonal transformation, a movement from hostility to hospitality. Finally, the article formulated some practical guidelines for the spiritual practice of hospitality as a living action and behaviour for ordinary people in everyday life.

The contribution of contemporary American writers Brown Taylor and Pohl were showcased to provide simple and practical steps to practise hospitality as "love", expressed in a particular and focused way. Hospitality is accomplished through the sharing of self, the giving away of self, and the vulnerable receiving from an Other that results in transformation, creating community.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Askew, J. 2022. European politics beginning another lurch to the right? Euronews. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/10/24/is-european-politics-beginning-another-lurch-to-the-right [23 December 2022]. [ Links ]

Bourgeault, C. 2014, Interspiritual pioneer Beatrice Bruteau loomed large in the contemplative universe. National Catholic Reporter. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.ncronline.org/news/people/interspiritual-pioneer-beatrice-bruteau-loomed-large-contemplative-universe [6 December 2022]. [ Links ]

British Broadcasting Corporation 2019. Europe and right-wing nationalism: A country-by-country guide. BBC. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36130006 [23 December 2022]. [ Links ]

British Broadcasting Corporation 2022. Afghanistan: Taliban ban women from universities amid condemnation. BBC. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-64045497 [23 December 2022]. [ Links ]

Brown Taylor, B. 2009. An altar in the world. A geography of faith. New York: HarperCollins. [ Links ]

Bruteau, B. 1980. Freedom: "If anyone is in Christ, that person is a new creation". In: F.A. Eigo (ed.), Who do people say I am (Villanova, PA: Villanova University Press), pp. 123-146. [ Links ]

Dale, D. 2022. Fact check: Herschel Walker falsely claims Raphael Warnock lied about having a dog. Cable News Network. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/08/27/politics/fact-check-walker-warnock-dog-ad/index.html [6 December 2022]. [ Links ]

Evdokimov, P. 1990. The art of the icon: A theology of beauty. Redondo Beach, CA: Oakwood Publications. [ Links ]

Hales, C. 2017. Why icon writing and not painting? American Association of Iconographers. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://americanassociationoficonographers.com/2017/02/28/why-icon-writing-and-not-painting/ [16 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Herstein, G. 2009. The Roycean roots of the beloved community. The Pluralist 4(2):91-107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20708980. https://doi.org/10.1353/plu.0.0013 [ Links ]

Kamperidis, L. 1990. Philoxenia and hospitality. Parabola 15(4):4-13. [ Links ]

Keller, T. 2008. The reason for God: Belief in an age of scepticism. New York: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Lazarev, V.N. 1996. The Russian icon. From its origins to the sixteenth century. Edited by G.I. Vzdornov. Translated by C.J. Dees. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J. 2019. The infiniscience of the hospitable God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob: Re-interpreting Trinity in the light of the Rublev icon. HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 75(1), a5347. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i1.5347 [ Links ]

Marchinkowski, G. 2021. In the grip of grace. Henri Nouwen's perspectives on the unitive stage of the mystical path. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 7(1):1-24. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2021.v7n1.a34 [ Links ]

Marchinkowski, G. 2022. Where "the unbelievable and obvious collide": Spiritual practices and everyday life. Verbum et Ecclesia 43(1), 7 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v43i1.2654 [ Links ]

Martin, M. 2022. What the recent wins for far-right parties in Europe could mean for the region. National Public Radio. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2022/10/01/1126419403/what-the-recent-wins-for-far-right-parties-in-europe-could-mean-for-the-region [23 December 2022]. [ Links ]

Nouwen, H.J.M. 1975. Reaching out. The three movements of the spiritual life. New York: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Nouwen, H.J.M. 1987. Behold the beauty of the Lord. Praying with icons. Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press. [ Links ]

Nouwen, H.J.M. 2010. Spiritual formation. Following the movements of the spirit. Edited by M.J. Christensen & R.J. Laird. New York: HarperOne. [ Links ]

Ouspensky, L. & Lossky, V. 1982. The meaning of icons. Translated by G.E.H. Palmer & E. Kadloubovsky. Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. [ Links ]

Pohl, C.D. 1999. Making room. Recovering hospitality as a Christian tradition. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing. [ Links ]

Quenot, M. 1991. The icon: Window on the kingdom. Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. [ Links ]

Reimer, J. 2008. The spirituality of Andrei Rublev's icon of the holy Trinity. Acta Theologica Supplementum 11:166-180. [ Links ]

Richard, L. 2000. Living the hospitality of God. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. [ Links ]

Rublev, A. [n.d.]. The holy Trinity. [Online.] Retrieved from:.https://catholic-link.org/andrei-rublevs-icon-of-the-holy-trinity-explained/ [21 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Strezova, A. 2014. The icon of the Trinity by Andrei Rublev. In: A. Strevoza (ed.), Hesychasm and art. The appearance of new iconographic trends in Byzantine and Slavic lands in the 14th and 15th centuries (Canberra: Anu Press), pp. 173-232. https://doi.org/10.22459/HA.09.2014 [ Links ]

Volf, M. 2002. Theology for a way of life. In: D.C. Bass & M. Volf (eds), Practicing theology. Beliefs and practices in Christian life (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing), pp. 245-263. [ Links ]

Voloshinov, A.V. 1999. "The Old Testament Trinity" of Andrey Rublyov: Geometry and philosophy. Leonardo 32(2):103-112. https://doi.org/10.1162/002409499553082 [ Links ]

Date received: 22 March 2023

Date accepted: 24 October 2023

Date published: 13 December 2023

1 In Italy, Giorgia Meloni and her party, the Brothers of Italy, "a far-right group with neofascist roots, claimed the greatest percentage of votes in that country's election" in September 2022. In Sweden, "a far-right group called the Sweden Democrats won big" (Martin 2022). See also Askew (2022). The BBC lists Germany, Spain, Austria, France, Finland, Estonia, Poland, Hungary, Slovenia, and Greece as European countries in which support for right-wing political parties has significantly increased (British Broadcasting Corporation 2019).

2 For a description of Nouwen's methodology, see Marchinkowski (2021:6-7).

3 The icon was created as a tribute to St Sergius of Radonezh (1313-1392) (Strezova 2014:189). Serguis' "whole life was dedicated to the Holy Trinity" (Evdokimov 1990:244). The icon is admired in Russia as a "perfect example of iconic art" (Quenot 1991:114-115; Evdokimov 1990:256; Strezova 2014:68). In 1551, the Muscovite Council of 100 Chapters recognised it as such (Evdokimov 1990:246). Andrei Rublev was canonised by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988. (Reimer 2008:167).

4 Icons are apparently written and not drawn or painted (Hales 2017).

5 "But the wisest opinion in this matter seems to be that of G. Pomerantz, a modern philosopher and culturologist: The man who really feels Rublyov's Trinity is sure to feel that the question 'Who is who?' is idle and digressing from the main point, that Non-Amalgamation and Inseparability of the angels is the very essence of the matter; and if we try to see a difference between them we are sure to turn the Trinity into 'three goats,' as Meister Eckhart said." (quoted in Voloshinov 1999:107).

6 Some scholars object to the notion of a perichoretic "dance" believing it to be, despite its allure, a human invention. See Keller (2008:213, 280).

7 There is a potential word play in this instance: To remember is to recall something and to remember is to put back together that which was once divided.

8 Divine hospitality can, of course, not only be conceived from the perspective of being triggered by the human spiritual practice. It is an ontological divine reality which may be perceived as inviting the human spiritual practice.

9 See, as an example, the commentary on CNN about the bizarre series of assertions in political television commercials for the campaigns of both Raphael Warnock and Herschelle Walker in Georgia, November and December 2022 (Dale 2022).

10 Louw (2019:2) defines "presencing" as "a kind of encounter wherein the past, the present and the future intersect in such a way that sensing (experience) and present moment (state of being) coincide in order to create a sense of meaningfulness and purposefulness".