Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.43 suppl.36 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/at.vi.7025

ARTICLES

Confronting the cataracts of whiteness to see the invisible: reflections on the transmission and reception of the Bible in post-apartheid South Africa

J. Kok

Evangelische Theologische Faculteit Leuven; Research fellow, University of the Free State. E-mail: kobus.kok@etf.edu, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1538-3089

ABSTRACT

The goal of this article is to draw on some of the latest insights in biblical studies on the challenges posed to the reflection, transmission, and reception of the Bible with relevance to a post-apartheid South African context. The author engages with prominent figures in the field of Biblical Studies and critical race theory such as David Horrell, in order to address the issue of whiteness and its impact on marginalisation. The aim is to foster a deeper understanding of the ways in which certain voices have been rendered invisible and to continue to question and challenge these dynamics. This paper delves into the interpretation of the Bible in Africa, using the perspectives of scholars such as Thomas Wartenberg in conjunction with the ideas of Charles W. Mills, W. Jennings, R. Ellison, and Steven Biko, as well as other notable figures, to critically reflect on the role of biblical scholarship in the process of restoring historically marginalised voices within the context of past injustices.

Keywords: Critical race theory; Decoloniality; Postcoloniality; Biblical studies

Trefwoorde: Kritiese rasteorie; Dekolonialiteit; Postkolonialiteit; Bybelse studies

1. INTRODUCTION

On 17 November 2022, Prof. Dr Musa Dube, president-elect of the Society of Biblical Literature (SBL), read a paper in a seminar on John, Jesus and history by invitation of Prof. Dr Paul Anderson at the Denver Convention Centre in the U.S.A. For me, as a fellow (South) African, it was a moving experience to see a Black woman from Botswana, radiating visibly with the kindness and grace of Ubuntu, but with words of truth that were like a two-edged sword. Etched in my mind, is her visible figure in her grey attire that day, the colour of a dark thundering African storm. A storm warns, but the rain of the storm also blesses and creates life and a better vision of a world to come. Around her neck, a warm bright red necklace with an African pattern, the colour of an African sunset. The setting sun for me, as an African, symbolises that a particular day has passed and promises that, after a night of struggle, a bright new day will be born. In her graceful way, she communicated, inter alia, through narrative, a very important truth: Biblical scholarship lacks the full awareness of the cataracts of the White(ness) eye.1 She did not put it in those words. But she did explicitly point out that there is still hardly any focus on African insights, as evident in church history research, which is still, mostly at biblical and religious societies such as SBL and American Academy of Religion (AAR), told from a White Western point of view. One cannot but agree that, as Christianity increasingly shifts towards the global South, there needs to be a new agenda - an agenda in which we critically reflect on the cataracts of whiteness and the manner in which we still make some (voices) invisible. The radiant light of that new day calls us to action and ongoing contemplation.

The work of restoring the voices of the invisible, against the background of the long history of injustice of the past, has started.2 And the rocky road of that new day's journey will be a long road to a new form of freedom. To make us increasingly aware of the socially constructed cataracts of whiteness, we need to confront ourselves with the light of critical deconstruction, so as to confront our own ontological blindness and the manner in which we sustain discourses, structures, and systems that make or keep others invisible in implicit hierarchies that exclude and marginalise.

2. PURPOSE AND CONCEPTUAL APPROACH OF THE ARTICLE

The purpose of this article is to engage with scholars in the field of critical race theory to confront the problem of whiteness, in an effort to help us reflect on ways in which we can become increasingly sensitive to how we have marginalised some voices into the space of invisibility and continue to do so. In this sense, the article wants to contribute directly to the purpose of this special edition, which aims to critically reflect on "biblical reception and the construction of social hierarchies in Africa".

Consequently, I want to engage critically with recent biblical scholarship that has started to reflect critically on whiteness. I will take us on a positive trajectory towards the reception of the Bible in Africa. Two research questions inform the approach of this study: How can the problem of whiteness be confronted to take us further into the ongoing process of critical reflection? How can such awareness shape the reception of the Bible in Africa in ways that challenge the legacy of problematic social hierarchies in Africa?

My conceptual approach was influenced, among other things, by Wartenberg (1988) and others who explicitly aim to critically approach this subject from the perspective of "the other". Wartenberg does so as a White male, and critically asks from a gender perspective, how female students will receive the material. This led him to realise the inherent problem associated with what I would describe as a conflicting dialogical schizophrenia, whereby we are confronted by the noteworthy voices of the significant others encountered in the literature. The significant others are mainly writing from a White male perspective, with the implication that we are further overshadowed by the construction of the world by these White males and their dominant position in the society they construct. In a way, it is similar to what Du Bois (1903) and Fanon (1986) expressed by "double-consciousness", whereby we look at and judge ourselves through the eyes of the dominant Other (see Biko 1987:ix, xii).

In South Africa, critical voices might point out how they are not represented in such philosophical texts. And if they are, it is in ways that denigrate them (see Biko 1987:viii, ix, xii). We need to address this concern directly with a passion for justice, restoration, and reconciliation. And that is the implicit hope I have. It is my hope that, as we critically reflect on the way in which we constructed meaning in the past, and co-construct meaning moving forward into the future, we do so in ways that witness the creation of life-giving theology in a spirit of inclusion, justice, and restoration.3

3. CRITICALLY IDENTIFYING THE PROBLEM OF INVISIBILITY

Ellison ([1952] 2016:ad loc.) famously expressed the conundrum as follows in his masterpiece Invisible man:

I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me ... because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact. A matter of the construction of their inner eyes ...

The setting in which to locate the work of Ellison is the experience of a Black man as a minority group in the United States during the 1940s and early 1950s. Some might argue that we need to distinguish between the contextual world and the referential world and, even more so, between the former and our context in Africa in a post-apartheid context in 2023. Critics might say that the Black experience as a minority in America is not the same experience as that of Black people as a majority in South Africa. Others argue that a deep underlying problem exists, which is a valid experience that continues even nowadays. Drawing on the insights of Ellison, Mills (1998:10) notes in his book Blackness visible: Essays on philosophy and race that the

White experience is embedded as normative, and the embedding is so deep that its normativity is not even identified as such.

He convincingly argues in his book that Western philosophy as such is in a way blind to its own ontological whiteness and "the foundation of putatively ineluctable hierarchies" embedded therein (Mills 1998:xiii). Mills endeavours in his book to show how race is ontological, even when, strictly speaking, biological elements might not be at play. It is also deeply existential and a lived experience, shaping an embodied way of being. He is very aware of the problem of reductionism and essentialism but nevertheless wants to express the fact that race plays a metaphysical role, even though it might not be physical. For Mills, it is important to construct a Black epistemology. He is, among others, influenced by the work of Du Bois and Fanon. In his own experience, Mills (1998:2) became aware of a "self-sustaining dynamic" in which Western philosophy is taught at universities such that it sustains a "conceptual theoretical whiteness".

Those Whites who want to understand what is at stake with the notion of the "invisibility" that a Black person experiences, will find much food for thought in the work of Wartenberg. He noticed the fundamental problem when he decided to actively put himself in the shoes of his female students.4This opened his eyes to realise how it must feel to read books that have been written by White misogynistic men. He was rather astounded to realise how many statements are made that clearly reflect a discourse that is made possible because of an implicit male-dominant hierarchy. It goes without saying that such dominance, based on an implicit hierarchy, goes hand in hand with forms of subjugation. This is, of course, also the case that Black people, and even more so, Black women, would naturally feel a form of alienation and "othering" when they are confronted with these kinds of material. It forms a landscape in which we feel very much that we are located in a certain subjugated position. We occupy not the castle, but the marginal outskirts of a world belonging to a power that looks down upon us. We realise, to use a metaphor, that the powers that be have a global positioning system (GPS) and a cartography that does not look in any way like that of our own, or the group to which we belong. We realise that there is a great silence, as our voice, and those of our group, are not heard or even reflected in such literature. But when we are present or rather (re)pre(sented) in these texts, it happens in a degrading or subjugated manner. This is not how we would necessarily choose to (re) present ourselves. What is desperately needed then, is not merely a slight upgrade to the GPS, but a whole new kind of GPS that is constructed from a completely different structuring logic.

This kind of awareness leads Mills (1998:2-3) to use what we feel is an inappropriate metaphor: "[A] lot of philosophy is just white guys jerking off." Despite this unfortunate metaphor, his point is valid. He argues that philosophy, constructed by White males, never really endeavoured to address problems that most people, in the majority (Black) commonwealth for that matter, experienced. For that reason, they philosophised about pseudo-problems or at least problems that are not in feeling with the real problems that people experience. This is especially true for our day and age as we read such literature and feel that it is not addressing the fundamental questions and challenges that Black people experience. Or that it is studied uncritically and does not address the manner in which these very philosophical constructions have been used to degrade people of colour. In fact, argues Mills (1998:3), we have to ask whether these philosophies in any way had as their ideal to address such problems or challenges in the first instance. The answer is evident. No! Students at South African universities feel frustrated and increasingly call for a decolonial turn. A turn that would place them in the centre, and not on the subjugated periphery. What sceptics view as a rebellious youth is, in fact, a generation saying that we want to see a form of justice and restoration. It reminds us in South Africa of the song "Weeping", written by Dan Heyman in the mid-1980s during the period characterised by the State of Emergency. This song mentions that the lion is not roaring; it is weeping. Heyman saw the underlying brokenness and the need for restoration. The fundamental question for us is how we restore the majority of South Africans in a way that is inclusive and critical of the implicit cognitive GPS maps that are, in fact, not only outdated, but also in need of a reboot into a new operating system. In contemporary songs produced by South African artists such as the award-winning Simphiwe Dana, these ideas are clearly expressed, especially in her song "State of emergency" which was released in 2012. She mirrors the past and present contexts (referential world and contextual world) by reminding the listener of the social injustices of the past, and the ways in which these injustices continue in different forms. The song ends with the words "Yimfazwe, Yimfazwe" (war, war), meaning that the war and struggle should continue, to make the promises of the new constitution and democracy true and not sell out on those who struggled for freedom in the past.5

One of the main challenges is to realise that the White Western experience can hardly be called a universal experience. The problem is that, in countries where the Western frame of reference is dominant, they believe that this is superior, normative, universal, and representative of the human experience as such (Mills 1998:10). This, of course, is simply not true. It is not representative, and neither is it inclusive. For that reason, we need ongoing reflection that deconstructs these paradigms and reflects critically on the legacy of whiteness. Even in the past few months, as natural language processing programs such as ChatGpt burst on the scene in 2022 and early 2023, scholars have pointed out the biases of the algorithms, representing the data it was trained on, not representing per se the voice of marginalised groups. I agree and support those who argue that we need to make our students very sensitive to the inherent problem involved in having "supervisory power", in other words, being critical of who determines how and on what terms the invisible becomes visible, and to what extent we should sustain or transform the implicit hierarchy that makes such schemas possible in the first place.6

In the next section, I address examples of the most recent insights in New Testament Studies that have explicitly called for an increased awareness of the implicit "whiteness cataracts", and endeavoured to address these issues consciously.

4. CRITICAL WHITENESS AND NEW TESTAMENT INTERPRETATION

4.1 David Horrell's radical turn and the implication for Biblical Studies and the reception of the Bible in ways that are critical of implicit hierarchies

In 2020, Horrell published a book entitled Ethnicity and inclusion: Religion, race, whiteness in constructions of Jewish and Christian identities. He explains the process of his "conversion" after having become aware of the problem of whiteness and exclusion. His book wants to challenge the reader to confront the "unreflected Christian tradition" and a "rarely questioned sense of superiority". As Christians, we easily speak and make use of terms and metaphors such as "fulfillment", but rarely do we stop and ask how such "scripturally legitimate" terms sustain and inculcate a sense of superiority, exclusion, and "persistent structural dichotomy"7 that denigrates the Other.

In the foreword of Horrell's book, Judith Lieu explains why the 21st century is characterised by identity politics, and that it comes as no surprise then that scholars in Theology and Religious Studies have responded from the perspective of critical studies in their own field. It is also understandable that the New Testament as such inherently contains significant concern with identity and boundaries because it was a movement that, from the beginning, had to struggle with its identity. For both Horrell and Lieu, the turn to identity studies is not simply some random and temporary intellectual approach, but belongs to an approach that intersects with, exposes concealment, uncovers, and inherently confronts configurations and power and dominance. In the foreword, Lieu maintains that the implication thereof is that we should realise that it represents an important challenge to move away from essentialist notions of identity towards a constructivist paradigm, and realise the porosity of identity and boundaries. This has significant implications for policymaking and in the way in which we approach and conduct social imagination and inclusion in our day and age.

In his book, Horrell shows awareness of the inherent problem associated with implicit hierarchy in Western European identity and its underlying epistemological foundation, and how that eventually led to ideologies that lead to a marginalisation of others. Given what we discussed earlier, it is noteworthy to observe that Horrell is critical of "Christian Universalism", and especially how a portrait has been painted of an inclusive Christianity over and against an exclusive and narrow-minded boundary-drawing Judaism that contributed to problematic ideas fuelling antisemitism. Engaging with the work of Jennings (2010), and others such as Carter (2008), Horrell shows how the Rassenvrage (racial questions) are deeply intertwined with the Judenfrage (Jewish questions) such that theology played a crucial role in the construction of social and racial imagination. Jennings particularly argued that theology was the "trigger" for the "classificatory subjugation" of people of colour. Jennings opines that the conceptual framework underlying the idea of supersessionism contributed to the Othering of non-White bodies in a colonial space. And about that, we are not critical enough. In South Africa, the idea that the White race associated themselves with the chosen people of God sent to bring "light" to "dark" Africa directly contributed to schemas that subjugated Black people. At its heart, such subjugation is motivated by a theological framework made possible by Christian universalism, and distorted supersessionism. In recent research, Kok (2022) illustrated how such conceptions directly influenced E.P. Groenewald, who justified racial apartheid from Scripture.

Horrell examines the pseudoscientific ideas of the previous centuries, specifically those related to race theories, using analogies and metaphors based on the paradigm of evolutionary development, to establish hierarchies, placing the superior White race at the top and the "less developed" people of colour at the bottom (see Biko 1987:viii). This ultimately contributed to the Holocaust. And for good reason, these essentialist notions were discredited in the years following World War II.

It is so shocking to encounter cases of such racism and images of degradation in our day and age. After a racist tweet comparing the baby (Archie Harrison Mountbatten-Windsor) of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle to a monkey, a BBC Radio presenter was fired. For a recent critical reflection on negative campaigns against Markle, see the chapter by Kendra Marston who reflects on #Megxit and the problem with the "reassertion of Britishness as necessarily white" in the Routledge handbook of critical studies in whiteness, edited by Hunter and Van der Westhuizen (2022).

Horrell also problematises the notion of ethnicity. First, the 19th and early 20th centuries dealt with ethnicity in essentialist ways. At that time (before F. Barth), there was a lack of insights seeing how ethnicity is a result of a social-constructivist enterprise. These uncritical perspectives, at that time, conflated essential views on race with essentialist views of ethnicity.

Horrell critiques the commonly held view among colleagues that the Judeans of the 1st century were an exclusive ethnic and racial group known for their exclusive boundary-drawing brashness. He maintains that it is anachronistic to impose such essentialist notions onto the ancient context. He posits that viewing the Judeans as a separate exclusive boundary-drawing group in contrast to the inclusive, non-ethnic Christ-following groups is simply misguided and contributes to denigration. Furthermore, he argues that this kind of perspective perpetuates a hierarchy in which the Christian movement, led primarily by White males, is viewed as superior and more evolved than the narrow-minded Judeans. This ultimately represents an outdated view that was, in fact, directly in service to antisemitism.

In the first chapter of his book, Horrell (2020:26) discusses the work of leading German scholars such as Ferdinand C. Baur, and how they constructed a hierarchical understanding of "Christliche Universalismus" (Christian universalism) versus "Judische Particularismus" (Jewish particularism), based on the belief in White racial superiority. Horrell admits that his previous scholarship also uncritically accepted these categories.

He notes that other prominent scholars in the field, including Sanders, Esler, Tucker, and others, have all done the same. At a recent seminar of the SBL in 2022, leading scholars discussed the use of social identity theory in writing New Testament commentaries and acknowledged the problematic framework inherited from scholars such as Baur and the Tübingen school. Horrell opines that we as scholars have not been critical enough about this framework, and his work encourages a more robust critical reflection on these issues.

Buell's book Why this new race: Ethnic reasoning in Early Christianity had a significant impact on Horrell's thinking. Buell challenges the commonly held belief that early Christianity was a movement that aimed to transcend ethnic and racial distinctions from its inception. Instead, she argues that the earliest followers of Christ formed a new group with clear boundaries that, in fact, excluded many, referring to themselves as a new "ethnos" or "genos" (for example, Aristides Apol. 2.2; Epistle Diognetus, 1.1). The book explores the writings of early Christians and examines how they constructed their identity in what would be considered racial and ethnic categories, creating closed boundaries, while also (like a semi-permeable cell)8 claiming to be universal and open to outsiders. Buell critically reflects on the legacy of this ethnic reasoning and its (potential) impact on Christian antisemitism and other problematic notions of White superiority. Her critical reflection on the legacy of the ethnic reasoning of the earliest Christians, and how that contributed to Christian anti-Semitism and other problematic superior White racial identity notions, particularly inspired Horrell.

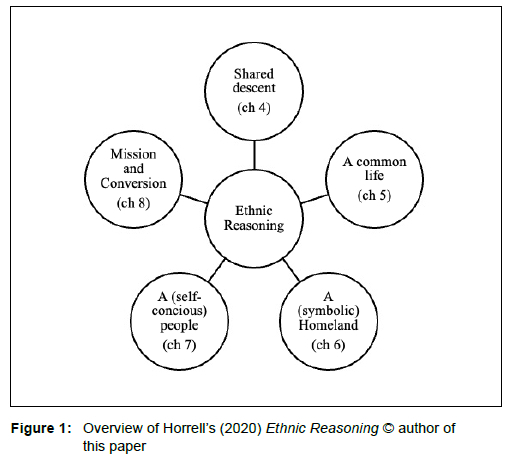

In his book, Horrell conducts a lengthy study (in Chapters 4-8) of almost two hundred pages, drawing, inter alia, on Buell, Barth, Hutchinson, and Smith, illustrating how we can hardly come to another conclusion but to see how all the notions of ethnic identity construction were evident in early Christian identity construction (Esler 2022; 1 Peter 2:9). The following ethnic categories are discussed:

Based on this in-depth study, Horrell urges his readers to challenge the status quo: One can no longer hold on to naive notions that sustain the discourse in support of the assiduous structural dichotomy favouring a "superior"inclusive universalist (Christian egalitarian movement over and against an exclusive boundary-drawing Jewish particularism that denigrates and subjugates the Other.

4.2 Challenging "implicit whiteness and Christian superiority"

Chapter nine is one of the most challenging chapters of Horrell's book. In this chapter, he interrogates whiteness. For him and others,9 whiteness is nothine less than a particular structural advantage and the position thatwe take from the beginning to glare upon ourselves and the Other. With his own double-edged sword, he remarks that whiteness as such is the force that shaped the framework of the discipline of Biblical Studies.

Scholars such as Horrell face the daunting task to examine their own whiteness and potential biases while using the tools of the dominant group to destruct/deconstruct the structures of oppression.10 Black South Africans are often critical of this approach, feeling that it is disrespectful for White scholars to speak on their behalf (Biko 1987:x-xiii). However, it is important to acknowledge scholars such as Horrell's courageous attempts at self-reflection and willingness to critically examine their own position. Horrell encourages readers to listen to marginalised voices and to re-evaluate the ways in which our discipline is constructed and research is conducted, particularly in terms of creating opportunities for underrepresented perspectives (Horrell 2020:344).

I wholeheartedly agree with this approach and, therefore, welcome the decision of the SBL in their appointment of Prof. Dr Musa Dube as president-elect. At the prestigious Society of New Testament Studies, we also actively recruited scholars from the global South in a deliberate effort to be more inclusive.

5. CRITICAL REFLECTION ON HORRELL

Although some of us have the utmost respect for Horrell's courage and openness to be challenged in his own thinking and his commitment to personal growth, as well as his challenging of other scholars to do the same, there are also those who are critical of his approach. In his review of Horrell's book, the leading New Testament scholar Philip Esler (2022), best known for being the first to introduce Social Identity Theory to New Testament Studies, provides several critical perspectives.

Esler (2022) is of the opinion that Horrell makes himself guilty of ad hominem arguments. He does this when he does not engage in any meaningful exegetical arguments that falsify his own position. Arguments could indeed be made, on social scientific exegetical grounds, that the earliest Christians did engage in trans-ethnic endeavours. According to Esler, it is misleading to dismiss these insights by simply making ad hominem arguments directed to a form of discreditation justifying it based on the "enmeshed 'whiteness'" of these scholars. One such an example, in my own experience, is that of a former departmental colleague of mine, Bruce Hansen (2009), in his well-researched book All of you are one: The social vision of Galatians 3.28,1 Corinthians 12.13 and Colossians 3.11. His own lived experience tells the tale of someone who is deeply committed to racial equality, both for his wife and for his children of colour. He and others observe, exactly in the New Testament, evidence of inclusive trans-ethnic notions that enabled early Christ-followers to include people from different (ethnic) groups. For him, there is a hopeful perspective in the early Christian message.

Those skilled in statistics will also appreciate the difference between causation and correlation. When two sets of variables appear to have a relationship, we speak of correlation, which might, on a simplistic level, resemble a causality. However, causation is something different. It wants to establish an active influence of one of the variables on that of another. Esler (2022), a trained lawyer, points to what he views as a logical error in Horrell's work, and which is typical also in some legal cases, namely that it is a logical fallacy when we assume that correlation implies causation. By ignoring the exegetical studies that contradict his own opinion, conflating his negative notions with ad hominem arguments, and basing it on "correspondence" between past and present, he plays the person(s) and not the ball, and does not, in fact, prove causation. A point in case, which Esler (2022) observes, and which a person conducting socio-cognitive critical discourse analyses can also easily observe, is the

ominous frequency with which he advances propositions as 'possible' (e.g. 'possible connections' on his p. 7, noted above) in contrast to the vanishing rarity of the required 'probable'.

Another matter up for debate is Esler's (2022) criticism of how we speak about inherited "race" and "ethnicity". Esler observes that, in contemporary discourse, we steer away from essentialised notions of "race" and "ethnicity". Which is all well and good. But then, at the same time, we are blind to the way in which our white skin or race is so deeply tied to "whiteness" by those who are not "white" or critical of "whiteness". Esler points out that many would earnestly claim that "race" is simply "constructed", but at the same time underplay the way in which the discourse also "represents the reinstatement of a racist ideology but with the hierarchical order changed".

It is also noteworthy for future debate whether we could challenge the idea that the earliest Christians made themselves guilty of "ethnicising" or rather of "de-ethnicism". Horrell would agree that the ancient Judeans constructed their identity in what we would contemporarily describe as "ethnicising", for instance by claiming that they are physical offspring of Abraham (Luke 3:8; John 8:39). When Paul claims (Gal. 3:6-29) that the non-Judean Christ-followers were descendants of Abraham, it would have been (and was!) completely unacceptable to Judeans. That is exactly why Paul resorted to social innovation, by de-linking it from physical "ethnicising". Esler (2022:14-15) argues:

In Galatians, Paul contests the meaning of Abraham by eliminating the element of physical descent central to Judean ethnic identity as he deploys the patriarch's significance in a new manner. This is not 'ethnicisation' but 'de-ethnicisation' and 'de-ethnic reasoning'.

Another interesting point up for debate, which I have also not considered previously, is Esler's (2022) observation that, when it comes to the people and the land, the earliest Christ-followers de-linked the Christ-followers from the land. He points to several cases, inter alia to John 4:21, with which Horrell fails to engage (compare also with Gal. 4.21-27). In John 4:21, we read the following: "IMAGEMAQUI" (NA 28) (Translation from NIV: "Woman", Jesus replied, "believe me, a time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem"). According to Esler, this is a form of "de-ethnicising", whereby the land, with specific reference to the centrality of Jerusalem, is displaced and replaced.

Esler suggests that the earliest Christ-following discourse demonstrates a form of transcending ethnic boundaries, as individuals from diverse backgrounds came together to partake in the Lord's meal (for example, 1 Cor. 11:20, 12:13; Gal. 3:28; Col. 3:11). This should not be viewed as anti-Semitic Christian universalism, nor should contemporary notions of race be imposed upon ancient Mediterranean groups. In addition, it is important to note that the conflict between Paul and Judean Christ-followers centred around the transethnic nature of Paul's community and their disregard for the traditional boundaries separating Judeans and non-Judeans (for example, Gal. 2:3, 11-14; John 4:9). In his review of Horrell, and in his latest social identity commentary on 2 Corinthians, Esler (2022) highlights that the in-Christ group identity included both Judeans and Greeks (Gal. 3:28), differing significantly from traditional Judean ethnic identity. Even scripture itself makes it explicit that outgroups perceived Judeans as boundary-drawing and exclusive (see, for example, John 4:9), and for that reason, it could hardly be said that these views are one-sidedly projected by White males.

Although Esler appreciates the excellent work done by Horrell, he has several reservations, which scholars would, in the future, have to reflect on critically and robustly as this important dialogue is continued in critical solidarity. These discussions must take place, to see and confront the "cataracts of whiteness" and see those who are often "invisible" in the texts we produce or have produced.

6. SUMMARY AND CONCLUDING REMARKS

This paper set the scene and encouraged us to reflect critically on the cataracts of whiteness that blind or distort our view, to not see the invisible(s). I drew on the insights of scholars such as Du Bois, Fanon, Mills, Jennings, and others. I found particular inspiration from Wartenberg who challenged me to approach the research from the perspective of the Other. Insights that stood out were that women and Black people in South Africa - and in other parts of the world for that matter - might be confronted with the feeling of double-consciousness as they read and study academic material that confronts them with the fact that their own people and their own epistemic concerns are not represented therein. Most of the academic materials are written from an epistemological perspective embroiled in epistemic whiteness. The point was made that the time has come that this needs to change. We accept the challenge posed by our SBL presidentelect Prof. Dr Musa Dube, to be truly inclusive, and to engage with scholars and material related to the global South.

In the second part of the paper, we turned our attention to Biblical Studies, and specifically to New Testament Studies. We focused our attention on the latest courageous ground-breaking work of Horrell, who is positioned in the heart of a former global colonial empire, namely Great Britain. We also presented a balanced critique of Horrell by scholars such as Esler.

Horrell challenges the status quo, by critically reflecting on the legacies of whiteness, and calls on the implied readers of his book, who are themselves projected to be caught up in the blindness caused by white cataracts, to follow his example. Horrell critiques not only whiteness, but also the implicit power dynamics embedded within Christianity. He sees in Christianity examples of exclusion based on problematic notions of universalism and supersessionism. This leads to the creation of hierarchies that are not inclusive but marginalise other groups. Previous presidents of the SBL include Prof. Dr Adele Reinhartz. In her presidential address (Reinhartz 2021), she mentioned the following:

[T]he value of the Society of Biblical Literature as a learned society and a scholarly community must be measured not by the experiences of those who flourish but by those who struggle. To live up to our own values, and to be of value to society at large, we must commit to equity and justice . helping us all to perceive the workings of whiteness, and to engage more honestly with the deep structures of our intellectual enterprise.

In her paper, Reinhartz points to her position as a Jewish New Testament scholar and testifies to the problematic presence of ongoing and persistent Christian supersessionism and "subtle anti-Judaism" at the SBL.

I opine that most of the people would agree that the work of Horrell took the invitation of Profs Reinhartz and Dube seriously. Of course, his own research was well underway before the publications of Reinhartz' and Dube's own work. In his acknowledgments, he explicitly recognises the influence of Dube on his own work. This shows us how important collegial exchanges are and how we can positively influence one another. Horrell represents a positive development in the field and points to hopeful ways in which we can reflect on the reception of the Bible, also in Africa, in ways that challenge whiteness and the implicit hierarchies that it constructed in the past and keeps on constructing in the present.

However, when it comes to the reception of decoloniality in South Africa and the programme of delinking from the legacies of coloniality, Snyman (2015) correctly asks not only how long those who are decedents of colonialism and apartheid may be held accountable? Such that they are deemed permanently in a state of guilt for the sins of their forbearers' guilt? Snyman recognises the rage in the hearts of those who have been wronged in the past. But he also calls for a hermeneutic of vulnerability on both sides of the spectrum.

[T]hat a hermeneutic of vulnerability is imperative for a perpetrator in order to enable him or her to become more response-able and responsible to those who are still bearing the marks of apartheid. On the one hand there is a need to develop a hermeneutic that will empower those who are associated with a perpetrator-disgraced culture to reconstruct themselves and their culture. On the other hand, a hermeneutic that fails to take seriously the effects of colonialism on those who bear the marks of the performativity of whiteness, remains powerless to address the concerns of those dealing with the bad memories of the past. Vulnerability is created when one looks into the eyes of the other and feels the embarrassment of one's own behaviour (Snyman 2015:636-637).

7. CONCLUSION

Prompting ChatGPT to write a poem based on some of the material in my paper, the following text was produced, which I believe expresses the purpose of this paper in a poetic manner rather well, and serves as an appropriate conclusion:

Ah, whiteness, so often a source of strife,

That renders certain voices invisible in life.

To comprehend how whiteness has caused marginalization,

We must challenge these dynamics with deep contemplation.

Sailing with Wartenberg and swimming with Mills,

Dancing with Jennings and wailing with Biko;

Striving alongside Horrell and other notable figures too;

In restoring historically marginalized voices we must all pursue.

In Snyman's hermeneutic of vulnerability, truth aligns,

Revealing nakedness of others, shared humanity that binds.

(Poetic text created by Ó ChatGpt: prompted and edited by J. Kok on 2 August 2023.)11

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alshater, M. 2022. Exploring the role of artificial intelligence in enhancing academic performance: A case study of ChatGPT. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4312358 [17 January 2023]. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4312358 [ Links ]

Anderson, C.B. 2009. Ancient laws and contemporary controversies: The need for inclusive interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195305500.001.0001 [ Links ]

Biko, S. 1987. I write what I like: A selection of his writings, 15 Oxford: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Buell, D.K. 2005. Why this new race: Ethnic reasoning in Early Christianity. New York: Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/buel13334 [ Links ]

Carter, J.K. 2008. Race: A theological account. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195152791.001.0001 [ Links ]

Dana, S. 2012. Simphiwe Dana - State of Emergency Lyric Video - International Version with Subtitles. Youtube. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=119OqGvXQg8 [16 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1903. The souls of black folk. Chicago, IL: A.C. McClurg & Co. [ Links ]

Ellison, R. [1952] 2016. Invisible man. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Esler, P.F. 2022. Religion, race, whiteness in constructions of Jewish and Christian identities. The Expository Times 133(7):284-289. [Online.) Retrieved from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00145246211068346 [9 October 2023]. [ Links ]

Fanon, F. 1986. Black skin, white masks. Transl. By C. Lam Markmann. London: Pluto Press. [ Links ]

Hansen, B. 2010. All of you are one: The social vision of Galatians 3.28, 1 Corinthians 12.13 and Colossians 3.11 . London: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Horrell, D. 2020. Ethnicity and inclusion: Religion, race, whiteness in constructions of Jewish and Christian identities. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Hunter, s. & Van der Westhuizen, C. (Eds) 2022. Routledge handbook of critical studies in whiteness. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429355769 [ Links ]

Jennings, W.J. 2010. The Christian imagination: Theology and the origins of race. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kelly, s. 2002. Racializing Jesus: Race, ideology, and the formation of modern biblical scholarship. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Kok, J. 2022. The implicit influence of Kittel and Grosheide in the shaping of apartheid in South Africa? The case of E.P. Groenewald. In: L. Bormann & A.W. Zwiep (eds), Auf dem Weg zu einer Biographie Gerhard Kittels (1888-1948) (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, HBE 3), pp. 367-390. [ Links ]

Mail and Guardian 2012. Simphiwe Dana: State of Emergency. 5 June 2012 [Online.] Retrieved from: https://mg.co.za/article/2012-06-15-simphiwe-dana-state-of-emergency/ [16 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Mills, C.W. 1998. Blackness visible: Essays on philosophy and race. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Reinhartz, A. 2021. The hermeneutics of Chutzpah: A disquisition on the value/s of "Critical Investigation of the Bible". Journal of Biblical Literature 140(1):8-30. https://doi.org/10.1353/jbl.2021.0001 [ Links ]

Snyman, G. 2015. A hermeneutic of vulnerability: Redeeming Cain? Stellenbosch Theological Journal 1(2):633-665. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2413-94672015000200032 [2 August 2023]. https://doi.org/10.17570/stj.2015.v1n2.a30 [ Links ]

Van Eck, E. 2010. A prophet of old: Jesus the "public theologian". HTS Teologiese Studies/ Theological Studies 66(1), Art. #771, 10 pages. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v66i1.771 [16 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Wartenberg, T. 1988. Teaching women philosophy. Teaching Philosophy 11(1988):15-24. https://doi.org/10.5840/teachphil198811121 [ Links ]

Date received: 18 January 2023

Date accepted: 23 June 2023

Date published: 30 November 2023

1 The metaphor of cataracts used in this instance was inspired by Mills (1998:xvi).

2 For examples of Biblical scholarship in South Africa that focus on inclusivity and social justice, see, inter alia, Van Eck (2010).

3 For the sake of the peer-review process, I cannot reveal my identity or positionality at this stage, but in the final paper, I will do so explicitly.

4 See, in this regard, also the important work of Anderson (2009) who paints the picture of gender prejudice in Theology.

5 See staff reporter in Mail and Guardian, 15 June 2012: "Simphiwe Dana: State of Emergency".

6 In January 2022, many experienced the revolutionary new AI program ChatGPT. I have come to see that it also produces text with bias. In his own research on ChatGPT, Alshater (2022:6) remarked: "There is also a risk that ChatGPT and other advanced chatbots may perpetuate biases present in the data they are trained on. Researchers will need to be mindful of this risk and take steps to mitigate it, such as by using diverse and representative training data." This shows us that even AI, with continuous general artificial intelligence capability and learning, is not free of implicit bias. And this poses a challenge to scholars to reflect critically on the mere production of AI information. In July 2023, I also went on an Erasmus exchange and had fruitful discussions with the University of Pretoria's head(s) (Dr J.C. Lemmens; Prof. Stals) of education innovation and their policies on ChatGPT in higher education. In future, AI will be incorporated and algorithms are being developed to identify when a text has been produced by AI and how to teach students and staff to be critical of information and bias generated by AI. This is in many ways revolutionary, but here to stay and will probably become integrated in our society in future in remarkable ways. Socio-cognitive critical discourse analyses ability, and broad philosophical knowledge will, in future, be more needed than previously, especially in theology and social sciences.

7 Jewish exclusive particularism vis-à-vis universalist Christian egalitarianism and inclusion.

8 This is not the metaphor that Buell uses, but that of the author of this article.

9 Fora discussion ofthe legacy of whiteness and thehelpful discussionof racial superiorityin German scholarship from the beginning, see, for instance, Kelly (2002:xi, 1-11).

10 Many voices in South Africa engage with post-coloniality and decoloniality and what "de-linking" entails. One such perspective is Snyman who calls for a hermeneutics of vulnerability being, inter alia, confronted with our own vulnerability and the "naked face of the other". He also points out the crucial role of memory of past injustice and not "forgetting", but at the same time in vulnerability work towards a form of justice and restoration.

11 I inserted my entire paper into a paid subscription to ChatGPT4 and asked it to construct a poem based on the content. Remarkable how it also incorporated the hermeneutic of vulnerability from a small footnote on Snyman on the topic.