Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.43 suppl.36 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/at.vi.7026

ARTICLES

"If I forget you Jerusalem" (Ps. 137:4). The transmission of sacred discourse in the Bible and in African indigenous sacred texts

M.K. Mensah

Department for the Study of Religions, University of Ghana, Legon; Research Associate, University of South Africa. E-mail: mikmensah@ug.edu.gh, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2959-7969

ABSTRACT

African biblical scholars have long advocated a shift in existing exegetical and hermeneutical approaches. The reasons include not simply the inadequacy of these approaches in dealing with the existential questions of contemporary African societies, but also their lack of effectiveness in transmitting the results of the exegetical process to receptor cultures in Africa, partly to be blamed on their colonialist legacy. One pathway to resolving the above challenge, which remains insufficiently explored, is to engage in a dialogue between the biblical text and African indigenous sacred texts. This paper, using a dialogical approach of African biblical hermeneutics, brings Psalm 137 into dialogue with the Adinkra amammerε (tradition), an indigenous text of the Akan of Ghana. It argues that reading these texts together uncovers their complementary views on the preservation and transmission of sacred discourse and could facilitate reception of the biblical message in contemporary Ghanaian society.

Keywords: Sacred texts; Psalm 137; Adinkra; African biblical hermeneutics

Trefwoorde: Gewyde tekste; Psalm 137; Adinkra; Afrika Bybel hermeneutiek

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the mid 20th century, African theologians have increasingly advocated for a paradigmatic shift in the methods and approaches used to read the Bible on the continent (Gatti 2017:47). The reasons for this shift were due to the inadequacy of the traditional hermeneutica! methods to address the real existential concerns of African peoples. Mbuvi (2017:154) asserts that African biblical hermeneutics was developed as an approach to reading the Bible in Africa in resistance to those methods which view the Bible "simply as an ancient text", without any real influence on the life of the African reader.

Another important issue that contributed to the rise of African biblical hermeneutics was the historical colonial baggage which had accompanied traditional methods of biblical exegesis. African theologians argued that the kind of biblical interpretation, which was inherited from Western missionaries, was largely coloured by European imperialism. Adamo (2015:34) asserts that biblical interpretation of the continent was essentially colonial, and consisted of a number of processes which alienated the African and his existential reality from the Bible. These processes included the use of the Bible to inculcate foreign values and the systematic repudiation of African values, the justification of violence against Africans, and the discrediting of African oral traditions, among others (Adamo 2007:22). Similarly, Meenan (2014:269) notes that traditional hermeneutical approaches mainly paid no attention to Africa's sociocultural context; hence, the need for a new approach understood from the perspective of the African, which stands in contrast or even in opposition to those methods inherited from the West.

The above concerns about the inadequacy of traditional methods of biblical interpretation in Africa relate to the more fundamental problem of the nature of discourse and its transmission. In his classical work, The archaeology of knowledge, Foucault (1972:216) argues as follows:

In every society the production of discourse is at once controlled, selected, organised and redistributed according to a certain number of procedures, whose role is to avert its powers and its dangers and to cope with chance events, to evade its ponderous, awesome materiality. In a society such as our own we all know the rules of exclusion. The most obvious and familiar of these concerns what is prohibited. We know perfectly well that we are not free to say just anything, that we cannot simply speak of anything.

Foucault's observations regarding the processes of knowledge production and its transmission suggest that there might have been nothing coincidental about the processes of interpretation engaged in by some of the earliest interpreters of the Bible on the African continent. While West (2016:2-6) suggests that Africans were significant protagonists in shaping the reception of the Bible in Africa, Mothoagae argues that every one of the processes involved with the production of biblical knowledge was in the hands of the colonial elite. From the translation of the Bible to the writing of commentaries on it, from preaching on these texts to the composition of hymns, and even to the training of the first Africans as ministers of the Bible, the colonial power found mechanisms of subjecting indigenes and "converting them into docile cooperative subjects" (Mothoagae 2021:1).

Beyond the question of the problem of colonialism, Mignolo (1999:235-236) warns of the further threat of coloniality. Ramantswana (2015:807) describes the concept as an "invisible structure of global power structures that sustain the colonial relations of domination and exploitation" which survives colonialism. Ossom-Batsa and Apaah (2018:277) assert that, even today, for many in Africa,

the transmission of Christianity essentially entails the complete elimination of the pre-Christian primal religions of Africa, 'giving the new means taking away the old'.

For this reason, African scholars such as Mothoagae (2022:2) agree with Mignolo on the need for an urgent and deliberate de-linking from the colonial epistemologies, by critiquing them and by applying a decolonial lens, while engaging with the Bible and biblical discourse.

2. DECOLONISING THE DISCOURSE ON SACRED TEXTS IN AFRICA

One of the consequences of the colonial experience was the belittling of Africa's textual traditions. Foucault (1972:220) observes that

there is barely a society without its major narratives, told, retold and varied; formulae, texts, ritualized texts to be spoken in well-defined circumstances.

The problem, as Arthur (2017:7) explains, is that texts were viewed as alphabetic and linear, such that

non-linear and non-phonetically-based writing systems have come to be seen as inferior attempts at the real thing and thus, have been marginalized.

Western agents engaged in narrowing the definition of texts to suit a very restricted narrative. Danzy (2009:18) observes:

The pattern that prohibitionists have in thinking and writing speech is 'writing represents speech, speech represent ideas and ideas represent things' ... This rigid pattern allows writing to be linked to speech directly, while it is linked to ideas and things indirectly. Western linguists adhere to this pattern rigidly and are not willing to regard the possibility that writing systems that do not operate this way should be considered writing. Therefore, systems like Adinkra are unrecognized and cannot exist.

The above situation means that colonialist standards exclude a good number of what Africans rightly define as texts. Amenga-Etego (2023:1), however, points out that African scholars have always viewed texts in Africa broadly, including

myths and legends, proverbs and sayings, music and dance, symbols, amulets and charms, totem and taboos, shrines and sacred places, and rituals,

thus demonstrating the inclusiveness of what constitutes sacred text in the indigenous African religions. Similarly, Labi (2009:45) notes that these proverbs and wise sayings, which are intangible, are sometimes expressed in "clear, visible, tangible, symbolic forms, thereby making the them 'readable'", such that these texts become important forms of visual communication that reveal historical, social, religious, and political dimensions of traditional societies.

Taking seriously Africa's indigenous sacred texts as real textual traditions implies creating a new awareness that the biblical text exists within a pluri-textual context in Africa. In much the same way that scholars have argued that the sociocultural context provides a hermeneutical lens through which the Bible may be interpreted, Africa's rich textual tradition provides an opportunity for another approach to the biblical text. Indeed, as I argue in this paper, African indigenous sacred texts could even become a more effective vehicle for the transmission of biblical discourse to Africans, since texts such as the Adinkra of the Akan people of Ghana and Ivory Coast have always been used as modes of communication

to offer pieces of advice, warnings and prohibitions [and to] transmit images and translate thoughts and ideas about values, norms and beliefs to guide people live accepted ways of life (Wilson 2021:203).

In light of the above, this study proceeds in three steps. First, by adopting the canonical approach to Psalter exegesis (Mensah 2016:6-12; Zenger 2003:37-58; Barbiero 1999:19-30), the study examines Psalm 137 as an example of a biblical text that illustrates the struggle of the transmission of sacred discourse in Israel within the context of the Babylonian exile. Secondly, the study turns to the question of transmission of sacred discourse through the Adinkra text, an African indigenous sacred text. Thirdly, by bringing the two textual traditions into dialogue, conclusions are drawn regarding the importance of reading the biblical text, conscious of its pluri-textual context in Africa.

3. PSALM 137: MY TRANSLATION FROM THE HEBREW MASORETIC TEXT

1By the rivers of Babylon

There we sat and wept while remembering Zion,

2Upon poplars in her midst we hung up our harps.

3For there, our captors asked us for words of a song

And our oppressors for joy.

Sing for us one of the songs of Zion!

4How shall we sing the Song of YHWH on foreign soil?

5If I forget you Jerusalem, let my right hand forget.

6Let my tongue cling to my palate if I do not remember

If I do not raise up Jerusalem above the first of my joys.

7Remember, O YHWH, the day of Jerusalem against the sons of Edom, Who said 'Rase it down! Rase it down to her foundation!'.

8Daughter of Babylon, Devastator! Happy the one who destroys you!

The one who repays you with what you repaid us.

9Happy the one who seizes and dashes your infants against the rock!

4. THE STRUCTURE OF PSALM 137

While scholars do not all agree on the strophic division of the psalm (Van der Lugt 2013:462; Savran 2000:43), it is possible to divide Psalm 137 into three strophes: Strophe I: verses 1-4; Strophe II: verses 5-6, and Strophe III: verses 7-9.

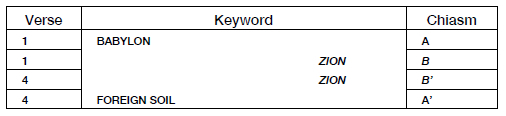

Strophe I (vv. 1-4) is framed by a chiastic ABB'A' arrangement based on certain opposing political designations as follows:

The frame of the strophe in verses 1 and 4 thus points to a certain tension between two political opponents. Moreover, the integrity of the strophe is maintained by the fact that the term (song) and its cognates appear five times in this strophe and in no other strophe. Besides, the psalmist uses the first-person plural

(song) and its cognates appear five times in this strophe and in no other strophe. Besides, the psalmist uses the first-person plural nine times in these four verses with no further occurrence in the succeeding strophe.

nine times in these four verses with no further occurrence in the succeeding strophe.

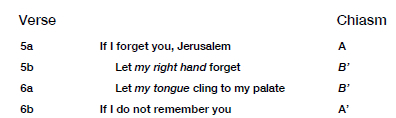

Strophe II (vv. 5-6) shows a break from the preceding by the sevenfold use of the first-person singular, thus "I forget", "my right hand" (v. 5); "my tongue", "my palate", "I raise up", "I remember", "my joys" (v. 6). Moreover, the political designation "Zion" changes in this strophe to the more religiously inclined "Jerusalem". Bellinger (2005:12) rightly notes the chiastic structure of the strophe as follows:

Strophe II is framed by two conditional sentences in verses 5a.6b which contain the contrary terms to forget  and to remember

and to remember  . In the centre of the strophe are verses 5b.6a, which contain references to body parts, the hand (v. 5b), with which the musician plays the harp referred to in verse 2, and the tongue (vv. 3-4) with which he sings.

. In the centre of the strophe are verses 5b.6a, which contain references to body parts, the hand (v. 5b), with which the musician plays the harp referred to in verse 2, and the tongue (vv. 3-4) with which he sings.

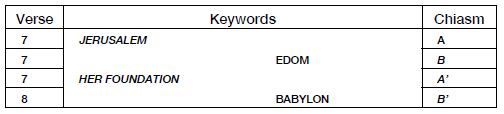

Strophe III (vv. 7-9) returns to the theme of the opposing cities. While in Strophe I, Babylon appeared alongside the non-explicit "foreign soil" as opponents of Jerusalem, this time Edom is specifically mentioned. The references to the nations in the strophe are thus arranged in an alternating ABA'B' sequence as illustrated below:

It remains clear that all three strophes are linked with the repetition of the term  (to remember) in verses 1, 6, and 7. All three strophes have some reference to Jerusalem or Zion (vv. 1, 3, 5, 6, 7), the capital city of Israel and the centre of Israel's worship.

(to remember) in verses 1, 6, and 7. All three strophes have some reference to Jerusalem or Zion (vv. 1, 3, 5, 6, 7), the capital city of Israel and the centre of Israel's worship.

4.1 Strophe I: The oppression of the exiles in Psalm 137

There is a certain level of consensus that Psalm 137 is set around the time of the Babylonian exile. Kraus (2003:501) asserts that Psalm 137 is the only psalm that can be dated with certitude to the exile. Other scholars, however, argue for a post-exilic date (Mays 1994:421; Weiser 1987:794; Kellermann 1978:52). While the above questions remain important, my attention is focused for now on the canonical text of Psalm 137, in an attempt to discern the nature of the oppression these forced immigrants protest in the psalm.

In Strophe I (vv. 1-4), the psalm opens with a spatial description of the exiles in Babylon. The term  (v. 1) has been variously understood as rivers or even irrigation canals (Ahn 2008:276), the latter suggesting that the exiles had been subjected to forced labour. The use of the term

(v. 1) has been variously understood as rivers or even irrigation canals (Ahn 2008:276), the latter suggesting that the exiles had been subjected to forced labour. The use of the term  (to sit) could otherwise refer to "dwelling", suggesting that the weeping, described in this instance, does not tell of some momentary emotional distress. For as long as they were forced to dwell in a foreign land, the exiles were in a constant state of emotional distress. Within this context, the psalmist speaks of the exiles hanging up their harps

(to sit) could otherwise refer to "dwelling", suggesting that the weeping, described in this instance, does not tell of some momentary emotional distress. For as long as they were forced to dwell in a foreign land, the exiles were in a constant state of emotional distress. Within this context, the psalmist speaks of the exiles hanging up their harps  the stringed instrument often associated with praise in the Temple (Pss. 33:2, 147:7, 149:3, 150:3). Rather than being an act of protest, this gesture denotes what Ahn (2008:280) describes as a reversal of power: "Stripped of artistry and musicianship, these temple elites were now reduced to irrigation ditch diggers." The first form of abuse the immigrant protests in Psalm 137 is the physical abuse of forced labour.

the stringed instrument often associated with praise in the Temple (Pss. 33:2, 147:7, 149:3, 150:3). Rather than being an act of protest, this gesture denotes what Ahn (2008:280) describes as a reversal of power: "Stripped of artistry and musicianship, these temple elites were now reduced to irrigation ditch diggers." The first form of abuse the immigrant protests in Psalm 137 is the physical abuse of forced labour.

The next point of interest in Strophe I is the request of the captors in verse 3a. They demand  literally "the words of a song". The expression is found nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible. In verse 3b, however, the request of the captors seems to be clarified. The song they demand from the captives should be a song of joy

literally "the words of a song". The expression is found nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible. In verse 3b, however, the request of the captors seems to be clarified. The song they demand from the captives should be a song of joy  Lenowitz (1987:155-157) suggests, for instance, that this song is understood as a mocking song sung to deride a defeated enemy, in which case it would be absurd for the exiles as captives to have sung it. The seemingly harmless request, however, might reveal a more sinister motive than it immediately suggests. The captors explicitly dictate three elements in the request: the words of a song, hence, the lyrics; the emotion with which the song is sung

Lenowitz (1987:155-157) suggests, for instance, that this song is understood as a mocking song sung to deride a defeated enemy, in which case it would be absurd for the exiles as captives to have sung it. The seemingly harmless request, however, might reveal a more sinister motive than it immediately suggests. The captors explicitly dictate three elements in the request: the words of a song, hence, the lyrics; the emotion with which the song is sung  and the subject of the song, the destroyed city of Zion.

and the subject of the song, the destroyed city of Zion.

The first element in the request, the words of a song, suggests particular interest in the lyrics of the song by the captors. The demand for the lyrics could be understood as some form of censorship. Granted that the captives would ordinarily sing in their mother tongue, it is instructive that their captors seek to understand what they are saying. What emerges from the request probably denotes a denial of the right of the captives to freedom of speech.

The second element in the request is joy. The demand for this particular emotion against the background of the weeping, described in verse 1, is at least curious. The foregoing might thus suggest that the request is a calculated attempt to deny the captives their freedom of expression and a stifling of their true emotions of sadness. This would constitute psychological abuse.

The third element in the request is that the captives sing songs of Zion. Bellinger (2005:10) points out three different possibilities of what this could mean. These could refer to songs to amuse the tormentors, or songs sung in worship in the Temple in Jerusalem, or even a category of songs such as the Zion Psalms found in the Psalter. It seems, however, plausible to hold that the nature of these songs of Zion has already been clarified through the rhetorical question posed in verse 4. These "songs of Zion" are the same as the "songs of YHWH", that is, songs used in worship probably in the Temple in Jerusalem (Alter 2007:591). The above is further underlined by the observation of Stolz (1997:1343), who notes that, in particular, "Zion designates Jerusalem as the city of Yahweh and his dwelling, the temple".

The above could only mean one thing, namely that the captors sought not simply to request a song, but also to dictate the lyrics, the emotions, and even the religious expression of the captives. The three requests suggest complete control of three cardinal faculties of the exiles: their intellect, their emotions, and their psyche. The rhetorical question in verse 4 is to be understood as a protest against this invasion of the personal space of the exiles, who, though forced immigrants, maintain their rights to sing, that is, to fully express their thoughts, desires, and hopes of redemption by the invocation of the name of YHWH. Strophe I thus underlines a conflict between those who would control the transmission of discourse, namely the Babylonian oppressors, and those who would resist such control, demanding the freedom to preserve and hand down their sacred tradition, namely the exiles of Israel.

4.2 Strophe II (vv. 5-6): The reassertion of the rights of the exiles

As noted earlier, Strophe II is signalled by the change of number in the person who speaks. The individual exile now speaks in the first-person singular. A close observation reveals the repetition of three concepts that emerged in Strophe I. First, the concept of speech, which was expressed by the phrase "words of a song" (v. 3), is now replaced in Strophe II by the instruments of speech, namely the tongue  and the palate

and the palate  in verse 6. Secondly, the term referring to emotions, joy

in verse 6. Secondly, the term referring to emotions, joy  , is also repeated in verse 6. Finally, reference to Zion, as the locus for religious expression in Strophe I, receives a response through the repetition of the synonym Jerusalem in verses 5 and 6. The exile's protest of Strophe I is thus turned into a fierce defiance in Strophe II. The psalmist asserts the right to freely speak, that is to use tongue and palate devoid of any dictation by the captors. Moreover, the exile asserts his right to joy but only when and where he chooses to express it. Finally, the exile defends his right to employ his own words and emotions within the context of that religious expression symbolised by Jerusalem, the dwelling place of YHWH. If in Strophe I, the rights of the exiles were threatened, in Strophe II, the same rights are reasserted. Thus the exiles' assertion of the right to preserve and transmit their sacred tradition is re-echoed in Strophe II.

, is also repeated in verse 6. Finally, reference to Zion, as the locus for religious expression in Strophe I, receives a response through the repetition of the synonym Jerusalem in verses 5 and 6. The exile's protest of Strophe I is thus turned into a fierce defiance in Strophe II. The psalmist asserts the right to freely speak, that is to use tongue and palate devoid of any dictation by the captors. Moreover, the exile asserts his right to joy but only when and where he chooses to express it. Finally, the exile defends his right to employ his own words and emotions within the context of that religious expression symbolised by Jerusalem, the dwelling place of YHWH. If in Strophe I, the rights of the exiles were threatened, in Strophe II, the same rights are reasserted. Thus the exiles' assertion of the right to preserve and transmit their sacred tradition is re-echoed in Strophe II.

4.3 Strophe III (vv. 7-9): The defiance of the exiles

As noted earlier, Strophe III responds structurally to Strophe I. The tension between the two cities Babylon and Zion in Strophe I returns in the mention of Jerusalem and Babylon in Strophe III. Beyond these structural indicators, however, it is possible to discern a thematic development which builds on the thought pattern of the preceding strophes. In Strophe I, the poet lays bare the nature of the oppression the exiles suffer, namely intellectual, emotional, and religious. In Strophe II, the exiles reassert their rights to free speech, to express sentiments of joy, all within the religious context of the Jerusalem cult.

In Strophe III, the same three elements re-emerge, but in the reverse order. In verse 7, the Psalmist calls on YHWH to remember against Edom "the Day of Jerusalem". This is clearly a reference to the destruction of the city by the Babylonians in 587 BC. Vesco (2006:1282) notes that the great crime of "the Day of Jerusalem" was the destruction of the Temple, and the city where YHWH dwelt, and the subsequent cessation of the cult to the deity. The charge of the exiles against Babylon and their allies, Edom, is the continual attempt to stifle their religious liberty.

The next element emerges in verses 8 and 9, with the repetition of the macarism  . Cazelles (1974:446) observes that the expression is a liturgical cry that "points to an act in which the believers seek happiness". In what appears an ironical twist, the psalmist, instead of responding to the captor's request for joy

. Cazelles (1974:446) observes that the expression is a liturgical cry that "points to an act in which the believers seek happiness". In what appears an ironical twist, the psalmist, instead of responding to the captor's request for joy  in verse 3, rather declares happy

in verse 3, rather declares happy  , the one who would avenge the exiles for the evil they have suffered at the hands of their oppressors. In a sense, those who denied the captives a genuine expression of sentiments of joy would suffer the same fate.

, the one who would avenge the exiles for the evil they have suffered at the hands of their oppressors. In a sense, those who denied the captives a genuine expression of sentiments of joy would suffer the same fate.

The third element is that of freedom of expression. The attempt to censor "the words of a song" (v. 3) appears to have collapsed under the defiance of the exiles. The words employed by the psalmist in Strophe III are among the harshest imprecations recorded anywhere in the Hebrew Bible. Alter (2007:592) even suggests that the words would have been uttered in Hebrew such that the captors would not have understood them. It is clear that these were not the words of the song the captors would expect from their captives. As Bellinger (2005:17) notes, this poem is a paradox. On the one hand, the exiles refuse to sing the words of the songs of Zion requested by their captors. On the other, the exiles are anything but silent. They will speak, but only what they want to speak and not what their captors want to hear! What this represents is the exiles' right to determine the content of their sacred discourse, and a resistance against the oppressors' invasion of that content.

The transmission of sacred discourse is clearly an important theme in Psalm 137. On the one hand, the aggression of the Babylonian oppressor is not only limited to physical oppression, but also extends to a manifest desire to control the discourse of the exiles. This attempt is made by seeking to dictate what genre of song the exiles sing and even the content of what is sung. This reaffirms Foucault's view of the way in which society organises, selects, and distributes discourse. The resistance of the exiles, on the other hand, resists the attempt by the Babylonians especially to control sacred discourse by refusing to sing YHWH's song. This reflects an insistence by the exiles on de-linking sacred tradition from the power of the empire. I suggest that the resistance of the exiles could become paradigmatic for contemporary attempts to preserve indigenous sacred textual traditions as vehicles for approaching the biblical text.

5. THE ADINKRA TEXT AND THE TRANSMISSION OF SACRED DISCOURSE IN AFRICA

Danzy (2009:31) describes the Adinkra as an "ideographic writing system", composed of visual metaphors that

carry, preserve, and present aspects of the beliefs, history, social values, cultural norms, social and political organization, and philosophy of the Akan (Arthur 2017:12).

The origin of the text is contested, with some scholars tracing its arrival in Asante to the prisoners of war deported from the kingdom of Gyaman in present-day Ivory Coast, following the triumph of King Bonsu Panyin in the 19th century (Marfo et al. 2011:64). Others argue in favour of a much earlier origin among the people of Denkyira, Asante, and Takyiman in present-day Ghana, while a third school of thought credits Muslim migrants with the more abstract ideographs (Adom 2016:1154).

Owusu identifies three functions of the Adinkra textual system in traditional Akan society. The first is to euphonise or memorialise historical incidents. Thus, the text Kontre ne Akwamu is used specifically to preserve the memory of the incorporation of the Denkyira and Akwamu people into the Asante Kingdom, while the text Gyau Atiko recalls the bravery of Gyau, the sub-chief of Bantama (Owusu 2019:49). The second is to represent certain cultural values. These texts, according to Owusu (2019:50), "are built on the collectively-shared traditions of origins and social responsibilities", and are explained by means of the parables, aphorisms, proverbs, popular sayings, myths, and oaths that accompany the texts. Thus, the funtumfunafu, the twin crocodiles with a single stomach, denotes the striving for the common good, while bi nka bi (one does not bite the other) denotes social harmony. The third is the artistic media that "embody figurative and proverbial observations" (Owusu 2019:49). In this regard, shapes of inanimate or man-made objects, plants and animals, architectural designs, or even abstractions such as Gye Nyame (the omnipotence of God) are used both as works of art and to communicate beliefs of values of Akan society.

Many Christian theologians and churches in Ghana have recognised the theological patrimony of the above indigenous text tradition. Ossom-Batsa and Apaah (2018:275-277) have shown how the Adinkra text has been incorporated into the architecture, logos, vestments, and other religious objects of Christian churches, not without the resistance of those who, perhaps influenced by years of Western influence, remain opposed to any such rapprochement between African indigenous traditions and Christianity. These efforts notwithstanding, a great deal more remains to be done, particularly in studying the complementarity between these sacred texts and the biblical tradition.

5.1 The Adinkra amammerεand the sacredness of tradition

The text amammerε(heritage or tradition) is one of the least studied in the collection of the Adinkra textual system. According to Amanquandor (2020:50-51), the term "amammerε" among the Akan refers to "a behavioural instruction or an imperative which has been passed on from one generation to another", through proverbs, songs, stories, or social interactions. Arthur (2017:285-286) identifies the saying which accompanies the Adkinra text amammerεas, Wokכ kurow bi mu a, dwom a εho mmכfra to no, wכn mpaninfoכ na εto gya wכn, literally,

when one goes to a village, the song the children there would be singing is the song their elders once sang.

This corroborates the fact that tradition is handed down. The saying illustrates a series of concepts relating to tradition in the Akan societies.

Key to the handing down of tradition is the role of the mpaninfoכ (elders). Van der Geest (1996:110) rightly notes that the ancestors are held as the authors of traditional wisdom, the reason why the formal citing of a proverb begins, mpaninfoכ bu bε sε... (the elders have a proverb which says). On the other end are the mmofra (children or youth), whose responsibility is to learn the lessons handed down. Thus, an Akan proverb, abofra kotow opanin nkyεn (the child squats beside the elder), describes a posture that denotes learning and assimilation of the wisdom of tradition.

The importance of the tradition itself is expressed in proverbs such as se wo were fi na wo sankofa a yenkyi (it is not a taboo to return and fetch what you have forgotten). Willis (1998:189) explains the proverb as a rediscovery of "an old tradition that links a people to the discovery of their past". This proverb, which has its own representation in the Adinkra text as a mythical bird with its head turned backwards towards its tail, is

an expression of self-identity and of the fact that the survival of society depends on the defence of its common heritage (Arthur 2017:274). Similarly, the proverb, tete wכ bi ka, tete wכ bi kyerε(the ancients have something to offer posterity), articulates the view that the heritage must be passed on.

6. TRANSMITTING BIBLICAL DISCOURSE IN CONTEMPORARY AFRICA

The above discussion of the transmission of sacred discourse in Psalm 137 and in the Akan traditional society reveals points of contact, upon which some dialogue is made possible. In Psalm 137, the insistence by the exiles on their total freedom, but especially their freedom to retain and to express their religious beliefs, without censorship or coercion, finds expression in their refusal to sing politically themed songs chosen by their captors. On the contrary, the exiles maintain their fidelity to Israel's religious and cultural heritage, while reserving the harshest imprecations for those who would attempt to deprive them of these liberties. A similar view of tradition is noted in the Adinkra text amammerε, which envisages children literally learning to sing the same songs their ancestors sang, or, in other words, carrying on the heritage passed on by their forebears. In both texts, the importance of a sacred tradition is underlined, which tradition must be learned, committed to memory, and transmitted to another generation whose solemn duty is to defend it and to further propagate it.

The foregoing suggests the possibility of appropriating the Adinkra text amammerεfor the purposes of complementing the message of Psalm 137 in the contemporary Ghanaian context. The reason for the psalmist's seeming inflexibility to the suggestions of his oppressors is because of what is really at stake. In the same way as the Akan understands it, the very survival of Israel's society depended on the exiles' fidelity to the heritage they had received. Similarly, the attitude of the exiles becomes a paradigm for the contemporary Ghanaian reader, emphasising the need to protect our cultural heritage, as a means to better understand the biblical text.

7. CONCLUSIONS

The transmission of discourse, as Foucault observed, is structured in every society in ways that seek to regulate who may speak, to whom, when, and what should constitute the contents of the discourse. In Africa, the colonial experience interrupted and corrupted indigenous engagement with the Bible through the imposition of a hermeneutical lens which sought to promote the culture of the empire at the expense of Africa's rich traditional heritage. While these processes still persist as a result of coloniality, African biblical scholars have begun to reclaim their turf, by insisting on a decolonial reading of the Bible and biblical discourses. In light of these earlier studies, this study demonstrates that such an effort could also harness African indigenous sacred texts, particularly the Adinkra text system of the Akan, as a way of approaching the biblical text. By reading Psalm 137 canonically, it is clear that the biblical text advocates the defence of Israel's religious heritage against attempts of encroachment by the oppressor. These same sentiments of preservation and propagation of one's traditions emerge in the Adinkra text amammerε, which charges the younger generation to sing the same song the elders sang and to pass on this heritage to future generations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adamo, D.T. 2007. Decolonizing the Psalter in Africa. Black Theology 5(1):20-38. https://doi.org/10.1558/blth.2007.5.1.20 [ Links ]

Adamo, D.T. 2015. The task and distinctiveness of African biblical hermeneutic(s). Old Testament Essays 28(1):31-52. doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n1a4 [ Links ]

Adom, D. 2016. The influence of European elements on Asante Adinkra. International Journal of Science and Research 5(7):1153-1158. https://doi.org/10.21275/v5i7.ART2016318 [ Links ]

Ahn, J.J. 2008. Psalm 137: Complex communal laments. Journal of Biblical Literature 127(2):267-289. https://doi.org/10.2307/25610120 [ Links ]

Alter, R. 2007. The book of Psalms: A translation with commentary. New York: W.W. Norton. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=lsdar&AN=ATLA0001625742&site=ehost-live&custid=ns083164 [6 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Amanquandor, T.D.L. 2020. Amammerε ne Amannee: Towards the indigenisation of the sociology of law concept of norms. Master of Arts. Lund University. [ Links ]

Amenga-Etego, R.M. 2023. Unpacking toolluum as a sacred text: Understanding a religio-cultural concept of preparedness. In: A. Somé, M. Mensah & G. Nsiah (eds), Interpreting sacred texts within changing contexts in Africa (Presses ITCJ: Abidjan - G&B Press: Rome, Kitabu na Neno 2), pp. 7-25. [ Links ]

Arthur, G.F.K. 2017. Cloth as metaphor: (Re)reading the Adinkra cloth symbols of the Akan of Ghana. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse. (Kindle edition. [ Links ])

Barbiero, G. 1999. Das erste Psalmenbuch als Einheit. Eine synchrone Analyse von Psalm 1-41. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. Österreichische biblische Studien 16. [ Links ]

Bellinger, W.H.J. 2005. Psalm 137: Memory and poetry. Horizons in Biblical Theology 27(2):5-20. https://doi.org/10.1163/187122005X00077 [ Links ]

Cazelles, H. 1974. , shrê In: G.J. Botterweck & H. Ringgren (eds), Theological dictionary of the Old Testament II. Translated by J.T. Willis (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans), pp. 445-448. [ Links ]

Danzy, J. 2009. Adinkra symbols: An ideographic writing system. Master of Arts thesis. Stony Brook University. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. 1972. The archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language. Translated by Sheridan A. M. Smith. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. [ Links ]

Gatti, N. 2017. Toward a dialogic hermeneutics: Reading Gen. 4:1-16 with Akan eyes. Horizons in Biblical Theology 39(1):46-67. https://doi.org/10.1163/18712207-12341344 [ Links ]

Kellermann, U. 1978. Psalm 137. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 90(1):43-58. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.1978.90.L43 [ Links ]

Kraus, H.-J. 2003. Psalmen. 60-150. 7th edition. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. BK 15.2. [ Links ]

Labi, K.A. 2009. Reading the intangible heritage in tangible Akan art. International Journal of Intangible Heritage 4:42-57. [ Links ]

Lenowitz, H. 1987. The mock-śimhâ of Psalm 137. In: E.R. Follis (ed.), Directions in biblical Hebrew poetry (Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Academic Press), pp. 149-159. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=lsdar&AN=ATLA0001154975&site=ehost-live&custid=ns083164 [10 January 2023]. [ Links ]

Marfo, C., Opoku-Agyeman, K. & Nsiah, J. 2011. Symbols of communication: The case of Àdïńkrà and other symbols of Akan. Language Society and Culture 32:63-71. [ Links ]

Mays, J.L 1994. Psalms. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary. [ Links ]

Mbuvi, A.M. 2017. African biblical studies: An introduction to an emerging discipline. Currents in Biblical Research 15(2):149-178. doi.org/10.1177/1476993X16648813 [ Links ]

Meenan, A.J. 2014. Biblical hermeneutics in an African context. The Journal of Inductive Biblical Studies 1(2):268-272. doi.org/10.7252/JOURNAL.02.2014F.11 [ Links ]

Mensah, M.K. 2016. I turned back my feet to your decrees (Psalm 119,59): Torah in the fifth book of the Psalter. Frankfurt a. M.: Peter Lang. Österreichische biblische Studien 45. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-653-06762-0 [ Links ]

Mignolo, W.D. 1999. I am where I think: Epistemology and the colonial difference. Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies: Travesia 8(2):235-245. doi.org/10.1080/13569329909361962 [ Links ]

Mothoagae, I.D. 2021. Reception of biblical discourse in Africa. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 77(1):1-2. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i1.7204. [ Links ]

Mothoagae, I.D. 2022. Biblical discourse as a technology of "othering": A decolonial reading on the 1840 Moffat sermon at the Tabernacle, Moorfields, London. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 78(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i1.7812. [ Links ]

Ossom-Batsa, G. & Apaah, F. 2018. Rethinking the Great Commission: Incorporation of Akan indigenous symbols into Christian worship. International Review of Mission 107(1):261-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/irom.12221 [ Links ]

Owusu, P. 2019. Adinkra symbols as "multivocal" and pedagogical/socialization tool. Contemporary Journal of African Studies 6(1):46-58. https://doi.org/10.4314/contjas.v6i1.3 [ Links ]

Ramantswana, H. 2015. Not free while nature remains colonised: A decolonial reading of Isaiah 11:6-9. Old Testament Essays 28(3):807-831. https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2015/v28n3a14 [ Links ]

Savran, G. 2000. "How can we sing a song of the Lord?". The strategy of lament in Psalm 137. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 112(1):43-58. https://doi.org/10.1515/zatw.2000.112.1.43 [ Links ]

Stolz, F. 1997. Zion. In: E. Jenni & C. Westermann (eds), Theological lexicon of the Old Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson), pp. 1071-1076. [ Links ]

Van der Geest, S. 1996. The elder and his elbow: Twelve interpretations of an Akan proverb. Research in African Literatures 27(3):110-118. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, P. 2013. Cantos and strophes in biblical Hebrew poetry. Psalms 90-150 and Psalm 1. V. III. Leiden: Brill. OTS 63. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004262799_002 [ Links ]

Vesco, J.-L. 2006. Le psautier de David. Traduit et commenté. V. II. Paris: Cerf. LeDiv 211. [ Links ]

Weiser, A. 1987. Die Psalmen. Psalm 61-150. 10th edition. Zurich: Göttingen. ATD 15. [ Links ]

West, G. 2016. The stolen Bible. From tool of imperialism to African icon. Leiden: Brill. Biblical Interpretation 144. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004322783 [ Links ]

Willis, B.W. 1998. The Adinkra dictionary: A visual primer on the language of Adinkra. Washington, DC: The Pyramid Complex. [ Links ]

Wilson, A.J. 2021. Adinkra symbols and proverbs as tools for elucidating indigenous Asante political thought. In: E. Abaka & K.O. Kwarteng (eds), The Asante world (London: Routledge, Routledge Worlds), pp. 201-224. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351184076-14 [ Links ]

Zenger, E. 2003. Dimensionen der Tora-Weisheit in der Psalmenkomposition Ps 111-112. In: M. Faßnacht (ed.), Die Weisheit - Ursprünge und Rezeption. FS K. Löning (Münster: Aschendorff, NTA.NF 44), pp. 37-58. [ Links ]

Date received: 18 January 2023

Date accepted: 3 October 2023

Date published: 30 November 2023