Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.43 supl.35 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/at.v35i1.6374

ARTICLES

Pandemic oasis: Popular piety as women's life-giving communitas

K.F. Chan

Macao Polytechnic University, China. E-mail: t1685@mpu.edu.mo, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-8053-5823

ABSTRACT

This article argues and explores how popular Catholic piety can serve as an agent to create life-giving communitas for women in Macao, China. This research uses the narratives of six Catholic women about how their immersion in various public and private devotional practices creates solidarity and communities that are inclusive, empowering, and nurturing during the outbreak of COVID-19. Besides petitioning their long-lasting devotional images such as St Roch and Our Lady of Fatima, women learn and move on to a new model of online and live stream religious response and ritual innovations at the time of coronavirus in Macao. The digitisation of gathering strengthens the global connection among women to the rest of the world, shaping a new form of devotional culture and community ties that are not necessarily institutionalised. Devotional practices act as a spiritual oasis, personally and communally, for women coming together and bring hope, strength, and consolation to this unprecedented time.

Keywords: Popular piety, Asian feminist theology, Communitas, COVID-19

Trefwoorde: Gewilde pieteit, Asiese feministiese teologie, Communitas, COVID-19

1. INTRODUCTION

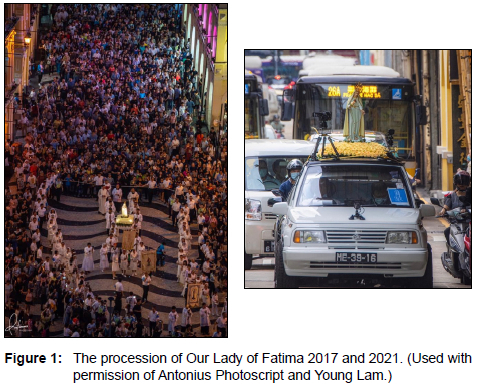

In May 2021, Pope Francis launched a month-long rosary request to the world to invoke the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary for the end of the pandemic. Each day, 30 Marian Shrines around the world take turns leading prayers and rosary. Whether the faithful gather together physically or virtually, the rosary recitation acts as an agent to create a communitas1 of solidarity, hope, and trust to invoke Divine intervention. Popular piety, such as religious processions, recitations of the rosary, and petition prayers to the saints are flourishing during the pandemic outbreak. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2019, many countries forced the execution of lockdown policy. The economy was halted, government buildings were closed, and most of the religious sites were closed to physical worship services. The digitisation of worship seems to be the new normal for the faithful. In Macao, a southern city in China and a former colonial city of Portugal, the long-lasting tradition of the procession of Our Lady of Fatima has been on hiatus for two years. The physical walking pilgrimage to the local Marian shrine has changed to live streaming of a pilgrimage to the statue of Our Lady of Fatima by car (Figure 1). This article argues and explores how popular Catholic piety serves as an agent to create life-giving communitas for women of faith from an Asian feminist perspective. First, I introduce the methodology, followed by the sociological data of the study. Then, I discuss the nature of the devotions and their correlation with the findings. The study concludes with a vision of women's faith and contribution to the local community.

2. METHODOLOGY

As this study aims to understand Catholic women's experiences in Macao during the pandemic, I employ interdisciplinary research that combines the disciplines of sociology, visual art, and theology. My methodology includes small-scale qualitative research as well as material and historical analysis. The interview subjects include six women from three leading ethnic groups - three Chinese, two Macanese,2 and one Filipina. Their ages range from 35 to 71 years, and the names given in this study are pseudonyms. I interviewed subjects at a place of their choosing such as their home, parish, or coffee shop. In most instances, I had one interview per subject, but three interviewees agreed to the option of more than one encounter, a follow-up interview after one year. The interviews were open-ended, and each lasted approximately one to two hours. All subjects agreed to have notes taken, and audiotaping was given permission. All interviews were transcribed into either Chinese or English. I rely on a "snowball" technique for my selection method, mainly on parishioners' referrals. Once identified, the subjects self-select by agreeing or refusing to be interviewed. In addition, I interviewed some people to obtain the historical narrative of Macao Catholicism, including the priests, nuns from the religious orders, and the emeritus bishop at Macao.

3. WOMEN, POPULAR PIETY, AND COMMUNITAS

In Macao, Catholic women constitute the most active participants in liturgy, events, and religious practices. How do women live as a community of faith during this pandemic? During the intensive phase of the lockdown (from February to May 2020), our women interviewees conducted much of their devotion through sacred objects, petition prayer, and visual participation in online liturgy and meditation.

3.1 Personal devotion and pandemic

In her early forties, Esther, a Chinese Catholic, created a home altar with a batch of devotional items on the top of the piano in the living room; she made it at the beginning of the outbreak in 2020. Most of the devotional items are gifts from friends, family, and souvenirs from her pilgrimages (Figure 2). She dug up her statue of St Roch, given to her by a parish priest decades ago. She said: "When we are in trouble, we want to find something to help."3 During the lockdown, she recited the prayers of St Roch daily and followed the 3 p.m. online prayers for Divine Mercy led by the local bishop. Esther recalled: "I encountered Divine Mercy when I went on a pilgrimage to Poland and visited the house of Sr. Faustina." Devotion to Divine Mercy and St Roch has been the focus of her devotion during this unprecedented time. When Esther attended an online mass in her room during the pandemic, her parents and other members respected her faith and turned down the television's volume. Esther now does much of her devotional prayers online without being physically present with others in the church. The unavailability of receiving the Eucharist creates a stronger desire for Esther to treasure the time she is freely and regularly having communion and connection with her fellow community of faith. However, the online devotional format enables Esther to reach out to more unfamiliar fellow Catholics at Macao that did not happen previously.

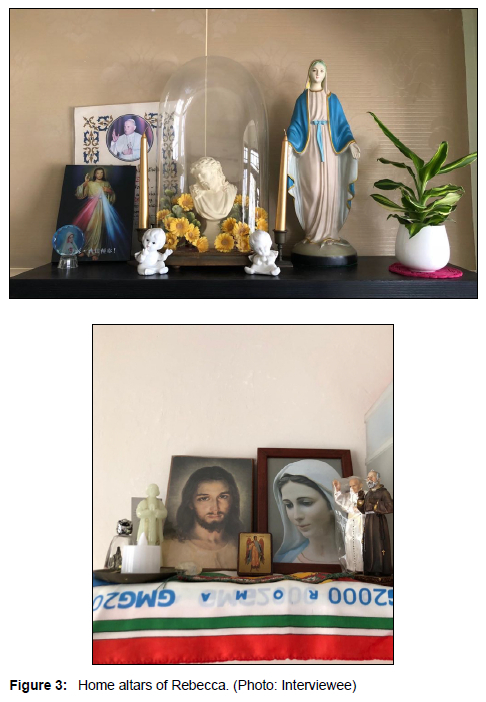

Rebecca, a Chinese in her early fifties, also has two fixed altars, one in her living room and one in her bedroom (Figure 3). There are several holy images, angels, and plants on the altars. She is a faithful devotee of Divine Mercy; both altars contain the image of Divine Mercy, and Rebecca recites her Divine Mercy prayer daily. During the pandemic, when most of the churches were locked down from January to March 2020, she followed Mass online every Sunday and joined the diocese for the live-stream prayers to Divine Mercy at 3 p.m. every day. Rebecca recalled one of her devotional experiences with the Divine Mercy while she was on a pilgrimage in Poland:

When I went to Poland, our pilgrimage group stopped amid a commercial area reciting the prayer of Divine Mercy at 3 pm. The pilgrimage guide taught us to sing a short phrase of Divine Mercy in Polish, and we were joyfully singing while we continued to walk on the street. I found it was an evangelization, especially in Europe; many Catholics were not going to church anymore.4

Memories and consolation associated with her experiences in the past have created positive strength and support for her in these two years. Before the outbreak of COVID-19, Rebecca had joined a church choir and several devotional groups. Since she prefers to pray with holy images of the Virgin Mary, her devotional prayer groups are all related to the devotion to Our Lady. She started to join the prayer group of Our Lady of Medjugorje after her pilgrimage to Medjugorje in 2007. She receives the image of Our Lady of Fatima once a year for two weeks, organised by a devotee to Our Lady of Fatima. Rebecca also receives the portrait of Our Lady of Guadalupe monthly for three days. This circulation of the images of Our Lady of Guadalupe is organised by two laywomen who have a personal devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe. They started to invite Catholics from different parishes to join the household rotation of receiving the image. Every time Rebecca receives Our Lady at home, she creates a unique altar space for Mary (Figure 4). Rebecca mentions that Virgin Mary is the most popular circulated image among the Chinese and Macanese Catholics at Macao; her prayer and circulation groups are often composed of ethnic Chinese and Macanese members, primarily women. In the post-pandemic interview, Rebecca stated that she continues to keep the online and physical group prayers. She related that the circulation of the Marian images ceased only for the lockdown period. Soon after the lockdown had lifted, the circulation started again and is still continuing. She said: "We had been putting on masks for two years, and the life stress continued; I also got some health issues, and rosary is the only thing that keeps me going."5 Rebecca's devotion to Virgin Mary and her devotional community have continued to be her solid support.

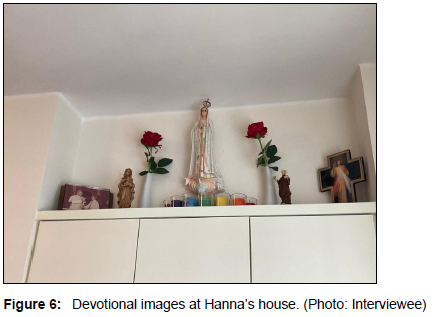

Two of the Macanese interviewees, Felicia and Hanna, stressed the importance of a home altar at the Macanese households as their generational and communal support for their religious practices. Felicia and Hanna are in their early seventies; both were professionals before they retired. They have been active in the parish for decades. Their households are full of religious pictures, statues, and icons (Figures 5 and 6). Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Hanna and Felicia could not go to church for rosary and liturgy. They relied on praying more in front of the altar and attended the online liturgy and prayers group from Macao and Portugal. Felicia mentioned: "We, Macanese, truly believe the petition power of St. Roch. That is why Macao has so few cases; we are well protected by St. Roch and Our Lady of Fatima."6 Hanna emphasised:

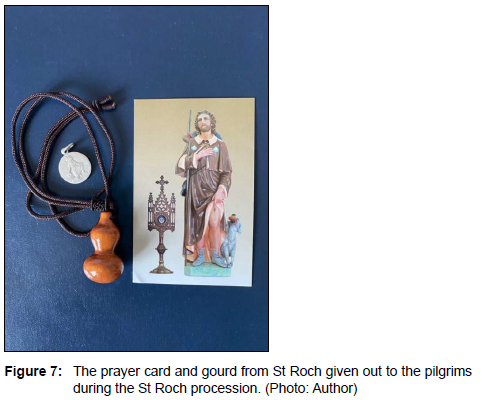

All Macanese are very faithful to St. Roch. Since I was a child, I carried the gourd as shown in the image of St. Roch. During the recent processions of St. Roch in the St. Lazarus Church, the gourds were given out for the pilgrims, but there is never enough for all the participants (Figure 7).7

The need for the physicality of the religious objects is the sacramentality of daily life.

Creating home altars with personal devotional objects is essential to help these women and their families through this difficult time. Home altars provide an "in-between" space for women to restore themselves, heal, and be comforted. Nevertheless, women have specific roles in the practice of devotion. Our interviewees stressed that their petition prayers are not only for themselves. Most of the prayers are for their families, for those who suffered and were affected by the pandemic, and for the global church. Women join communitas of prayers, even though they are not physically together.

3.2 Community devotion and pandemic

During the various phases of pandemics, women create communitas through their community bonding and personal gifts. Communitas is a term coined by anthropologist Victor Turner to refer to a spontaneously generated human bonding to experience liminality together (Turner & Turner 2011:250). Liminality means "being on a threshold" and is "the experience of being betwixt and between" (Turner & Turner 2011:249). The liminal, or in-between, is a space in which transformation can take place. Gina, an active Chinese parishioner in her mid-fifties, utilises her gifts and talents to create various small communitas to live out the pandemic liminality. Gina related:

Praying rosary and reading the Bible become my main support during the pandemic. I follow through the online liturgy and find myself more focused and calmer.8

Soon after her parish lockdown was lifted, Gina created an art crafts group to raise funds for the parish and local Caritas (Figure 8). Gina said:

On the one hand, we are encouraged to follow social distancing during the pandemic. On the other hand, I found people are longing for community and closeness during this difficult time. Since there is no place to go for a holiday or out of Macao, I organized three art workshops, including flower arrangement, English calligraphy, and Zen drawing, to provide communal support for the parishioners. Many people want to join some volunteers who work at the parish but don't know how. I utilize these workshops to invite parishioners to join us and build a stronger community.

Gina made it in a local newspaper report about her art craft group and has attracted more parishioners to join her solidarity support during the pandemic (Figure 9).

Emma, in her sixties, a Filipina working in Macao for thirty years, is a founding member of the Filipino Legion of Mary at Macao; their association started to circulate the statue of Our Lady of Perpetual Help among Filipino households twenty years ago. They signed up households to receive the image and gathered to pray the rosary, which they name Block Rosary in this religious practice (Figure 10). Emma finds that keeping her Catholic faith is very important, opening her home to family, friends, and fellow Filipinos far away from the church and inviting them to join the circulation prayer group of Our Lady. However, during the lockdown period, social distancing made circulation and physical fellowship difficult. The Block Rosary stopped during the lockdown period and resumed as soon as the restriction was lifted.

Filipino migrants are the most vulnerable population hit by this recent pandemic. Many Filipino migrants lost their jobs; were laid off during the lockdown, and cannot return to the Philippines because of travel restrictions. Many were trapped in Macao without adequate financial support. The Philippine Consulate General in Macao SAR had nearly 4,200 Filipinos repatriated to the country by way of a repatriation programme over the past two years (The Philippine Consulate General in Macao SAR 2021). The number of Filipino non-resident workers in the Macao SAR dropped by 15 per cent between January 2020 and June 2021, to almost 28,988 (Macao Labour Affairs Bureau 2021). Emma, also a working committee member of the Commission on Social Action of the Pastoral Center for Filipino Migrants at Macao, together with other Filipina migrants, collaborated with the local parishes and donors and obtained resources to distribute grocery items to migrant workers who lost their jobs or migrants who had only a few days of work in a month. Emma said:

We started to give out milk last March, and after the need was enlarged already, the priest in the pastoral center began to use some mission funds to buy something. Then we helped to pack the rice, coffee, something like that. And then there was a time when we have nothing anymore because I have a little amount. I told the priest that I could buy the rice for distribution next Saturday. When I started doing that, all my members from my devotional group began to give too. You know, when we have the initiative, people follow. One of my Portuguese friends phoned me when he knew that I was contributing, he gave some funds too. When an action is started, it attracts people, then donors continue and keep coming. Another Chinese university student interviewed me for his graduation thesis and knew our situation; he connected to other groceries stores he knew. Later, we got some fresh vegetables too.9

Emma realises that their devotion to Our Lady is important during the pandemic. She collaborates with the Filipino Pastoral Center to have weekly devotion to Our Lady of Perpetual Help and petition Our Lady's help for the strength of the Filipino community at this difficult time (Figure 11).

Hanna and Felicia obtain communal support not only in Macao, but also in Portugal. During the pandemic, some Macanese communities of faith were connected to the live stream of liturgy and praying online the Rosary at Fatima, Portugal. They joined different groups to connect and pray with their fellow Macanese in their native language. Gina also mentioned that, over the past two years, she often receives text messages from other prayer groups to designate a time to pray for a specific intention. She finds that praying together adds to the strength of facing the global pandemic, especially since many people have died, lost their jobs, and got trapped in certain places.

Women's roles are not only confined to their homes; they can contribute meaningfully to both society and the church through their participation in the most diverse professional disciplines and ecclesial leadership roles. Our interviewees' narratives show how women and their related devotional practices act as vehicles for women's spirituality and missioning. Popular piety serves as an agent of incarnation in the present and continues to provide God's presence as a safe space of grounded faith to people of all races, classes, and all those in need. Women's remarkable sensitivity and empathy for others promote and nourish the growth and development of the whole human person for themselves, their families, and their colleagues. Their participatory and personally oriented approach are the unique gifts that women bring to the church in Asia.

4. NATURE OF DEVOTION AS ACTS OF PIETY AND SPIRITUALITY

As indicated by the interviewees, the nature of devotion to the images of St Roch, Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Our Lady of Fatima and more, acts as piety that was inherited from, and influenced by the Iberian colonisation since the 16th century. Until the present day, Macao Catholic popular piety remains strong on novena, veneration, and devotion to Virgin Mary and the saints, and religious processions.

The term 'popular piety' designates those diverse cultic expressions of a private or community nature which, in the context of the Christian faith, are inspired predominantly not by the Sacred Liturgy but by forms deriving from a particular nation or people or from their culture (Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments 2001:9).

The Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments' Directory emphasises that acts of piety are distinguished from the liturgy: "While sacramental actions are necessary to life in Christ, the various forms of popular piety are properly optional" (Directory 2001:11). It is clear that the Directory indicates that popular piety and devotions should not replace the official liturgy, and that devotions should be undertaken in accordance with the official liturgy. The focus should be on how the practices can enrich the spiritual life of a Christian. Exercises of popular devotion should be undertaken as a positive means of expanding the church's mission to proclaim the kingdom of God (Phan 2005:46).

In his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis (2013:122-126) spoke at length about "the evangelizing power of popular piety". Pope Francis (2013:123) sees how

[p]opular piety enables us to see how the faith, once received, becomes embodied in a culture and is constantly passed on.

Being the first Pope from Latin America, Francis was influenced by several prominent Latin American theologians, whose theological approach emphasises the preferential option for the poor and inculturation of faith in popular piety (Deck 2016:36-61). Their pastoral-praxis approach to theologising has been called La Teologia del Pueblo (The theology of the people). It is contextual and not a top-down theology; it is a theology from the ground. When we relate to a ground-up approach to theology, daily devotional practices and popular piety play a crucial role in people's (interviewees') expression of faith.

In his book, The Catholic imagination, Catholic sociologist Andrew Greeley coins the phrase "Catholic imagination". He shows how God dwells in the world through material reality such as "a world of statuses, holy water, stained glass, votive candles, saints and religious medals, rosary and holy pictures" of the faithful's life (Greeley 2001:1). To Greeley, the Catholic faith is rooted in the sacramentality of everyday life. This perception of enchantment that God is present in the world means that

there is a propensity among Catholics to take the objects and events and persons of ordinary life as hints of what God is like, in which God somehow lurks (Greeley 2001:1).

This Catholic imagination enables devotees to be deeply connected to their devotional imagery. Objects tell stories: the statue of Our Lady of Fatima, St Roch, and holy pictures of Jesus of the Divine Mercy serve as visual icons that tell us the stories of the divine. According to Greely (2001:1-3), religion and faith communicate via experiences to imagination. Faith is the experience, while imagination, narratives, and the community develop from them. According to anthropologist Victor Turner (2011:143),

every symbol has a signifier and a signified. The signifier is the sensorial perceptible vehicle of a conception. The personifying process here involves a changing relation between signifier and signified.

St Roch's gourd is a signifier that is meant to represent not only the historical legend of St Roch's healing power, but also a continuation of St Roch's tradition of protecting the ill during the plague. These devotional expressions are performative, embodied, and lived in the everyday life of the faithful.

In her classic work Lived religion: Faith and practice in everyday life, McGuire (2008:98) defines spirituality as "the everyday ways ordinary people attend to their spiritual lives", pointing out that devotions provide a central significance in spirituality. McGuire views the expressions of cultic devotion as related to the specific needs of everyday life: a mother may practise devotions to saints known for protecting and healing children; farmers might seek help with the patron saints of farmers, and so forth. The act of devotional practice can be self-transcendent, deepening the experience of the presence of the Divine. Jesuit theologian Dorian Llywelyn (2017:171-187) views popular religiosity and devotional spirituality as the manifestation of sensus fidelium, explaining that

[l]ex vivendi, and lex orandi ontologically precede lex credendi and in that order, they underpin lex theologizandi. This means engaging deeply with the sensus fidelium.

Llywelyn argues that popular devotion can both inaugurate and nourish theology; popular devotional practice is the manifestation of the sensus fidelium, one that embraces the daily lives and local circumstances of Christians, embodying the spirituality of the devotees.

The above discussion of the nature of popular piety and its devotional practices shows the pietistic, performative, embodied, and spiritual expressions of their faithful, which are personal, communal, and culturally embedded in everyday life. Nevertheless, popular piety is not a substitution for the official Liturgy which is the "action of Christ the Priest and of his Body, which is the Church, it is a sacred action surpassing all others" (Directory 2001:11).

5. POPULAR PIETY, FAITH EXPRESSION AND ASIAN FEMINIST THEOLOGY

The different waves of the COVID-19 epidemic have restricted Macao citizens for several periods of time since 2019. Residents were forced to keep social distancing from each other, and the local churches were closed several times following the local public health policy. Faith expression through popular piety is valuable and significant, particularly during the pandemic.

From our interviewees' narratives, one of them started to build a home altar, and others utilised the altar space for daily devotion and prayers in this worldwide restriction cycle. The physicality of the material form of the home altars is another embodied and material practice that expresses the inner conviction of these women. Pastoral theologian Mary Clark Moschella (2008) stresses that visual piety of devotions offers security, comfort, and familiarity, fostering solitude and self-examination, which help the faithful experience growth. Through this embodied and performative form of spirituality, the embodied faith of the women is manifested by praying the rosary, meditating, or venerating an image, and touching and kissing the material form of the devotional objects. Robert Orsi, scholar of religious studies, explains that the Catholic devotional culture supports religious experience, gives meaning and identity to a Catholic world view, and gives meaning to the most difficult aspects of human existence such as pain, illness, and trial (Orsi 1985). These devotions create a sacred, safe, and embodied space for women devotees that embraces, consoles, and dwells in the Divine, and that offers healing and protection in everyday life. Devotions serve as a form of liberation for these women, allowing them to have their personal way of connecting with the Divine.

In our study, women devotees gather together in household prayer groups or during congregational devotional hours online or offline to constitute a communal act of healing and comfort. In his book Thank you St. Jude, Orsi (1998) views devotionalism as providing women with agency, finding their voices and space to act on their desires and hopes. The hope of ending the pandemic and living through the sufferings and pains became urgent. In his book On Job: God-talk and the suffering of the innocent, Gutierrez relates that Job starts with a "disinterested faith". However, Job gradually gains an understanding of God during his time of suffering.

The ethical perspective inspired by consideration of the needs of others and especially of the poor made him abandon a morality of rewards and punishments, and caused a reversal in his way of speaking about God ... [He] finally surrendered to God's presence and unmerited love (Gutierrez 1987:93-94).

The unwanted sufferings or restrictions during the pandemic speak well to our doubts, our complaints, and the injustice about life, but Job went "out of himself and help other sufferers to find a way to God" (Gutierrez 1987:48). Very similar to our interviewees, these women not only focus on their restrictions or suffering, but they also make use of what is available to welcome and build up communities and be with their fellow sojourner.

Popular devotionalism serves as an agent of welcoming and transformation, fostering the mission of welcoming and evangelising. The devotion to Our Lady of Fatima, as practised by nearly all of our interviewees, welcomes the faithful from all different ethnic groups, economic statuses, and educational levels. The household veneration of the image of Our Lady of Fatima, which circulates among the Chinese, Macanese, and Filipino faithful, has created solidarity among women of all ethnic identities. One interviewee related the story of an Indian family who had come to Macao for work; the wife asked if the family could also join the circulation of the image of Our Lady. Including and inviting the fellow faithful to join in a particular form of devotional practice or a household prayer group is a mission of hospitality. Private and public, online or offline devotionalism can build bridges for people to feel welcomed.

Korean feminist theologian Hyun Kyung Chung (1990:8) emphasises the awareness of the relationship between women's own experiences and contexts of cultural and social plurality in Asia in her "feminist liberation-orientated theological consciousness". Chung (1990:109-114) prioritises women's experiences and stories and accentuates that "[w]e [women] are the text". Virginia Saldanha, the Indian former executive secretary of the Women's Desk of the Federation of Asian Bishop's Conferences (FABC), continued her ministry of advocacy and empowerment even after her retirement. In her interview with the National Catholic Reporter (2011:n.p.), she stated the following:

The women's group has been a powerful tool in women's empowerment. It provides strong support for women as it creates an environment to help them to take action together ... I ardently believe that women coming together locally and in solidarity internationally can be a solid force to bring about change.

The powerfulness of women's groups became particularly precious during the global pandemic. From our interview data, women initiated support groups such as the group circulating the statue of Our Lady, groups run by women for the online rosary, and so on. These self-organised and self-initiated popular piety groups are founded on the women's culture and devotion in the local context of Macao. Besides, some interviewees mentioned that they had gathered funds to buy medical masks to send to other parts of the world such as Brazil, the Philippines, especially at the time of the global outbreak in 2019. They realised the unequal distribution of medical devices such as surgical and non-surgical masks, facial shields, gloves, and so on. Saldanha trusts that women coming together locally and internationally convey a solid force to make changes, such as safeguarding the distribution of pandemic medical resources.

Besides asserting women's voices and experiences, and constructing women's solidarity, we also need to pay attention to the cultural context of Asia. What does this everyday life devotion mean to the local faithful in the Asian context? The Indian Jesuit theologian, Michael Amaladoss [s.a.], suggests that a symbolic-hermeneutical method is more useful in the Asian context than the conceptual-logical way of theologising. It is a twofold hermeneutic or interpretation following experience: to reinterpret the tradition in the context of one's knowledge and find a new meaning in the experience considering one's tradition. Our Chinese interviewee Rebecca claims:

I don't feel the need to have a statue of Mary in Chinese style; that looks strange to me, I like what I have inherited from the Church. Since Macao is a place of East and West, we are used to having Western influences.

It appears that, for centuries, Chinese Catholics in Macao have welcomed all foreign images, statues, and iconography without questioning their foreign derivation. Rebecca pays more attention to her devotion and prayer life rather than to the look of Mary; she finds new meaning in what she has inherited from her family and the local church. Gina, another Chinese interviewee, focuses on her Bible reading and identity as Catholic, rather than following through with any particular devotion:

I got baptized through my husband's family who is generational Macanese. I can say I inherited their faith, but more important is to tell others that I am a Catholic and I have a strong sense of being part of the Church.

Being a nexus of Eastern and Western cultures, Macao's social, political, and economic changes have not affected this long-inherited generational faith.

Since Asia embraces rich and diverse faith traditions, the theology of people in the Asian context must respond to the multi-faith phenomenon, that is, to maintain harmony through dialogue with people of a different faith and dialogue is a mode of evangelisation. Dialogue and deeds must be carried out with harmony, which is crucial in the interreligious context. In places such as Macao, Christianity accounts for only about five per cent of the entire population. Every day, Macao Catholics meet and work with people of different faiths. One of our interviewees was baptised through her husband's faith. The Filipina interviewee invited workers on short-term stays in Macao to join their household devotion to Our Lady. A Chinese interviewee recounted her experiences of asking non-Christian friends to have a meal at her home and answering their questions about the devotional items on her home altar, a conversation that itself acted as an agent of dialogue. At this particular time of the pandemic, often restricted by the social distancing policy, people are more vulnerable and need substantial communal support. Dialogue in harmony becomes a good mode of missioning and care for the common good of humankind.

Despite the significance of maintaining harmony in many Asian contexts, the realities of significant disharmony - brought about by humankind through the economic exploitation of the poor, oppressive forms of government and social control, religious, cultural, and communal conflicts, ecological and environmental crises, and the abuse of science and technology - all threaten, weaken, and diminish the life of Asians (Tirimanna 2007:112-119). Nevertheless, in this pandemic, with the unequal distribution of vaccines, the poor and the oppressed become the victims, due to the gap between the poor and the rich. According to UNESCO's data, women made up 70 per cent of healthcare professionals and researchers working on COVID-19:

The plethora of burdens that women have borne during the pandemic has been very heavy, including the increase of sexual and gender-based violence against women and inequalities in access to the labor market, the gender pay gap, and the job loss, linked mainly to women's occupation in the informal economy. The pandemic has had a regressive effect on gender equality, with women undertaking more household responsibilities . Women are disproportionately affected in all crises, with COVID-19 as no exception, while they are the backbone of society and should be safeguarded and empowered (UNESCO 2021:n.p.).

UNESCO's statement on Women's Day in 2021 emphasised the need for unity in advancing gender equality and the essential role of women at the frontlines of the pandemic.

The first step towards achieving societal harmony and gender equality is to be aware of the long-lasting forces of patriarchal domination and to commit acts that reclaim space for women. As represented by the yin force that governs all nature, women need to obtain their space before they can optimise it as a harmonious partner to the yang of men; each party needs space to flourish. This insight is crucial, because it points to the fact that both men and women must be involved in changing thinking. Filipina theologian Mary John Mananzan understands that focusing only on women's issues cannot uproot all the problems women face in their societies. She writes the following (Mananzan & Park 1996:14):

The emerging Asian women's spirituality longs for freedom from exploitation - a free society for themselves and the men and the children. The liberation framework of Asian women includes and is included in the overall people's movement to be free. It brings a qualitatively different vision and interpersonal relationship from the traditional male way of constructing communities.

Achieving freedom for both men and women is an essential step towards the success of harmony between men and women, between religious traditions, between cultures, and between marginalised people and people in power within society. Pope Francis' address to the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue in 2017 affirms that dialogue "is a path that man and woman must accomplish together" (Hitchen 2017:n.p.). This path of accomplishment, as suggested by Pope Francis, resonates with the yin-yang ideology of harmony. Women and men are not competitors but collaborators with equal opportunities and status, fostering growth in working for the oppressed and the marginalised.

The experiences of the interviewees show a theology that is from the ground; many of them are self-directed and organised by women. Women initiate actions such as circulating devotional images to households, praying together, and working for the needs of the others through their gifts and their time. This is the lived theology that can transform the world. The contextual nature of the theology of the people in Asia also stresses the dialectic nature between different faiths, genders, and status. Throughout history, dialogue between cultures, religions, and everyday people has been a key to solving problems and resolving differences. The Federation of Asian Bishop's Conferences highlights the importance of dialogue as the mode of missions in Asia. Once again, women's participatory and personally oriented approaches have contributed to fruitful dialogues between people of different faiths and religious traditions that are most needed in this global crisis.

6. CONCLUSION

This study explored the relationship, during the global pandemic, between women, popular piety, and community building, using the Asian feminist perspective. By interviewing six women from three major Catholic ethnic groups - Chinese, Filipino, and Macanese -, we learn how popular piety, as shown on their home altar and their pietistic expression, creates hope and trust. We see how devotional practices act as a spiritual oasis personally and communally in this worldwide challenge.

Popular piety in this study is a significant force in people's lives. Popular piety has a rich theological meaning, constituting an integral part of spirituality for people of faith. This faith embodies a powerful sense of the transcendent, is strongly linked to the local culture, and draws devotees to the sacramentality of everyday life. Popular piety differs from the official Liturgy, which cannot be replaced by any form of religiosity. Our interviewees' pietistic devotion reveals that the nature of devotions is performative, embodied, and acts as an agent of evangelising and community building.

Women facing different realities at each stage of life require spiritual support through their religious tradition, culture, and society. Devotional practices facilitate meeting the needs of the faithful. Women pray for what they believe, and prayers change the women devotees into what they believe, constituting a devotional spirituality. Its role for women is a rich and important one, helping them through difficult stages in their lives and creating space for all people to cry out in their pain and maintain hope in the face of the realities of life.

7. ILLUSTRATIONS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amaladoss, M. [s.a.]. The Asian face of theology. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://michaelamaladoss.com./the-asian-face-of-theology [15 May 2020]. [ Links ]

Chung, H.K. 1990. Struggle to be the sun again: Introducing Asian women's theology. New York: Orbis Book. [ Links ]

Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments 2001. Directory on popular piety and liturgy: Principles and guidelines. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3IRtq03 [15 December 2021]. [ Links ]

Deck, A.F. 2016. Francis, Bishop of Rome. New York/Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press. [ Links ]

Greeley, A. 2001. The Catholic imagination. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520928053 [ Links ]

Gutierrez, G. 1987. On Job: God-talk and the suffering of the innocent. New York: Orbis Books. [ Links ]

Hitchen, P. 2017. Pope Francis: Central role of women interfaith dialogue. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3EBQDAF [28 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Liywelyn, D. 2017. Devotion, theology and the sensus fidelium. New Blackfriars 1074, 98, (March 2017):171-187. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://0-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.grace.gtu.edu/doi/epdf/10.1111/nbfr.12268 [5 March 2020]. [ Links ]

Macao Labour Affairs Bureau 2021. Statistics on labor force. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.dsal.gov.mo/en/standard/download_statistics/folder/root.html [23 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Mananzan, M.J. & Park, S.A. 1996. Emerging Asian spirituality. Women in Action 3:13-18. [ Links ]

Moschella, M.C. 2008. Living devotions: Reflections on immigration, identity and religious imagination. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publication. [ Links ]

McGuire, M.B. 2008. Lived religion: Faith and practice in everyday life. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

National Catholic Reporter 2011. Voices from women. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.ncronline.org/news/global-sisters-report/voice-women [23 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Orsi, R. 1985. The Madonna of 115th street: Faith and community in Italian Harlem, 1880-1950. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Orsi, R. 1998. Thank you St. Jude: Women's devotion to the patron saint of hopeless causes. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Phan, P. C. (Ed.) 2005. The directory on popular piety and the liturgy: Principles and guidelines, a commentary. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press. [ Links ]

Pope Francis 2013. Evangelii Gaudium. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papafrancesco_esortazione-ap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html [15 December 2020]. [ Links ]

Tirimanna, v. (Ed.) 2007. Sprouts of theology from the Asian soil. Bangalore, India: Claretian Publication. [ Links ]

The Philippine Consulate General in Macau Sar 2021. Consulate conducts 21st repatriation flights. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://macaupcg.dfa.gov.ph [23 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Turner, v. & Turner, E. 2011. Image and pilgrimage in Christian culture. New York: Columbia University Press. [ Links ]

UNESCO 2021. COVID-19: Women in the era of the pandemic. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3xNd9mz [4 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Date received: 26 May 2022

Date accepted: 8 December 2022

Date published: 26 April 2023

1 Communitas is a term coined by anthropologist Victor Turner to indicate that people are experiencing an unstructured society, based on relations of equality and solidarity.

2 Macanese is an ethnic group with a Portuguese ancestor from Macau.

3 Interview with the author, 25 July 2020.

4 Interview with the author, 25 July 2020.

5 Interview with the author, 24 August 2021.

6 Interview with the author, 23 August 2021.

7 Interview with the author, 23 August 2021.

8 Interview with the author, 3 September 2021.