Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.43 supl.35 Bloemfontein 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.38140/at.v35i1.6559

ARTICLES

The experiences of currently and formerly incarcerated women in a time of pandemic: Implications for life-giving communities

D.T.M. Veloso

Department of Sociology and Behavioral Sciences, De La Salle University, Philippines. E-mail: diana.veloso@dlsu.edu.ph; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5964-3455

ABSTRACT

This article assesses the adequacy of the church's responses to women currently and formerly in conflict with the law in the Philippines and offers feminist theological reflections on the need for gender- and culturally sensitive pastoral services for them in a time of pandemic. Drawing upon case studies and interviews, this paper examines the lived experiences and social worlds of women who currently occupy or formerly held the status of persons deprived of liberty. The researcher discusses the common themes and nuances in the issues and challenges they confront from behind bars and in free society, and their struggles for survival throughout the pandemic. This paper also examines their service needs and, in the case of those released from the penitentiary, the salient factors that contribute to the risk of recidivism. The researcher discusses the implications of the issues and service needs of justice-involved women for building life-giving communities.

Keywords: Justice-involved women, Women in prison, Women and re-entry, Pandemic and women

Trefwoorde: Geregtigheid-betrokke vroue, Vroue in die tronk, Vroue en herbetreding, Pandemie en vroue

1. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to afflict many countries, some of which have even witnessed a second wave (Al Jazeera 2020a; BBC News 2020). The exponential rate of infections and deaths in many countries, particularly those with less developed healthcare systems, has engendered a health and humanitarian crisis, with multiple social, political, and economic upheavals (Kaul, Shah & El-Serag 2020; Pazarbasioglu & Kose 2020). Aside from enforcing health-related interventions such as the use of face masks and/or face shields and the observance of physical and social distancing, governments worldwide limited people's movement and contact at the height of the pandemic, by imposing travel bans, quarantine policies, lockdowns, school closures, restrictions on mass gatherings, policies on the limited operation of organisations and institutions beyond those providing essential services, curfews, and stay-at-home orders (Cepeda 2020; Taylor 2020). Countries with high rates of COVID-19 infections witnessed an increased demand for health services, which stretched hospitals and similar facilities beyond their capacity (Cavallo, Dnonoho & Forman 2020; Gai & Tobe 2020; Lema 2020). Civil society continues to grapple with survival strategies as the pandemic has dragged on. Numerous sectors, including educational institutions, business enterprises, travel and tourism, hospitality, and events industries, have been hit hard (Becker 2020; International Labor Organization [ILO] 2020; Pedersen & Ritter 2020; Richter 2020; Schleicher 2020).

Given the magnitude of COVID-19 cases in the global north and the global south alike, people experience the social and economic costs of the pandemic through limited safety nets, especially for low-income communities and other vulnerable populations, lost or displaced educational and employment opportunities, recession, and halted global trade arrangements (Bismonte 2020; World Bank 2020). The magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and its social and economic costs, particularly for marginalised groups, has been documented in various reports (Norwegian Institute of Public Health 2020; Searight 2020).

Philippine society is not above the hardships brought about by the pandemic. The country is known for imposing one of the longest and strictest lockdowns in the world (Hapal 2021; See 2021). The Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF) was designated as the policy-making entity of the government and issued recommendations pertaining to the quarantine classification, lockdown rules and regulations, and other pertinent protocols (Kabiling 2020; Mendez 2020; Vallejo & Ong 2020). Adopting the recommendations of the IATF, the then President Rodrigo Duterte placed the entire island of Luzon on enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) from 16 March to 15 May 2020, leading to restrictions on people's movement, public gatherings, travel, the closure of schools and non-essential businesses, as well as the deployment of military and law enforcement personnel to implement security and health protocols during the quarantine period (Esguerra 2020; Ranada 2020; Tomacruz 2020). Based on the recommendations made by the IATF, the government subsequently transitioned to less restrictive forms of quarantine such as modified enhanced community quarantine (MECQ) and general community quarantine (GCQ), which local government units (LGUs) implemented accordingly, depending on the extent of COVID-19 cases in their respective jurisdiction (Al Jazeera 2020a; Calonzo 2020; CNN Philippines 2020a; Madarang 2020a; Romero, Medez & Chrisostomo 2020). That said, this did not lead to notable reductions in the number of new COVID-19 cases after the pandemic broke out (See 2021; Stormer 2020; Yee 2020). The Duterte administration also relied heavily on the military and the police to manage checkpoints, ensure order, and implement health protocols, even to the point of authorising the use of force against people tagged as "troublemakers" for protesting against the restrictions while under community quarantine (Amnesty International 2020; Hapal 2021; See 2020).

The extended lockdown, which led to prolonged restrictions in people's mobility and employment, inevitably resulted in adverse economic impacts on the general population. Policies such as "no work, no pay" and restrictions in the operation of businesses beyond those providing essential services, among others, led to massive job losses and the displacement of economic opportunities, aggravated by limited or fragmented safety nets (Madarang 2020b; See 2020). As of August 2020, the unemployment rate in the Philippines rose to 46 per cent, impacting on 27.3 million people (Hapal 2021). While the effects of the pandemic on low-income communities and the informal sector have been discussed in media reports, academic research, and public debate, its consequences for other vulnerable populations have not been explored as much. In particular, the impact of the pandemic on individuals who currently occupy or formerly held the status of persons deprived of liberty (PDL or PsDL), the term for inmates in Philippine corrections parlance has received minimal attention.

Existing information about this population group is limited to the reports of the media and non-government organisations (CNN Philippines 2020a; Human Rights Watch 2020; International Committee of the Red Cross 2020). First-hand accounts of prison life in the time of the pandemic - and in public discourse, in general - focus on men, while women are treated as an afterthought and thus receive scant attention (CNN Philippines 2020b; CNN Philippines 2020c; See 2020). This is consistent with the historic invisibility of justice-involved women1 in academic and public discourse prior to the pandemic because of the focus on men in the criminal justice system, despite the advancements in feminist criminological research over the past 30 years (Chesney-Lind & Pasko 2004; Howe 1994; Nagel & Johnson 2004; Steffensemeier & Allan 2004; Thomas 2003). Research on the experiences of justice-involved women in the global south remains limited, due to the greater attention given to their counterparts in Western, industrialised nations (Jeffries, Chuenurah & Wallis 2019; Jeffries, Rao, Chuenurha & Fitz-Gerald 2021; Philippine Human Rights Information Center & Women's Education, Development Productivity and Research Organization [PhilRights & WEDPRO] 2006; Ransley 1999; Veloso 2016; Veloso 2022; Villero 2006). Studies on the reentry experiences and challenges of women formerly in conflict with the law are likewise limited (Davies & Cook 1999; Renzetti & Goodstein 2001; Richie 2001), as the literature often focused on the experiences of men (Petersilia 2003). Information about the experiences and challenges of currently and formerly incarcerated women in the time of the pandemic is still emerging. It is thus crucial to examine the issues and service needs of justice-involved women and the impact of an unprecedented emergency such as the COVID-19 pandemic on their situation.

2. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

This study assesses the adequacy of the church's responses to currently and formerly incarcerated women. It also offers feminist theological reflections on the need for gender- and culturally sensitive pastoral services for this marginalised population group. This study examines the social worlds and experiences faced by women who currently hold or once held the status of persons deprived of liberty in the Philippines. It assesses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their situation. This paper also examines the role of the church in serving as an agent of restorative justice and in providing interventions that promote the dignity of women currently or formerly in conflict with the law. The researcher discusses the implications of the issues and service needs of currently and formerly incarcerated women, for building life-giving communities.

To assess the adequacy of the church's responses to women in conflict with the law and the need for gender- and culturally sensitive pastoral services for them, this research seeks to answer the following questions:

• What are the experiences of incarcerated women in a time of pandemic? How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact on their situation in prison?

• What are the re-entry experiences of formerly incarcerated women in a time of pandemic? How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact on their transition to free society?

• What are the service needs confronting justice-involved women?

• How can the church provide pastoral services for justice-involved women in a time of pandemic?

• What are the implications of the women's issues and service needs for building life-giving communities?

3. METHODOLOGY

This article uses case studies of women with the status of persons deprived of liberty. The material for the case studies was culled from observations during regular visits to women deprived of liberty as part of the researcher's long-term volunteer work in prison, as well as telephone calls with women deprived of liberty after the pandemic escalated. Meanwhile, the researcher conducted interviews with 12 formerly incarcerated women, who resided in Metro Manila or provinces in the northern and southern Philippines. The researcher also engaged in field observation at the places of residence of some informants, whenever possible. Informed consent was obtained from the informants. The names of the informants are withheld to protect their privacy.

The researcher incorporated principles from Catholic Social Teachings (CST) in examining the situation of currently and formerly incarcerated women and the implications thereof for the promotion of life-giving communities. This paper uses the lenses of feminist and intersectional theology. As such, it reflects the dialogue of theology with feminist theories, intersectionality theory, and other perspectives in gender studies and sociology.

4. SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY

This study is intended to benefit currently and formerly incarcerated women, by promoting awareness about their experiences and issues. This paper also seeks to benefit pastoral groups and civil society organisations that seek to serve persons deprived of liberty, as well as individuals transitioning to independent living, as part of their ministries.

5. RESULTS

5.1 Demographic profile of the women

5.1.1 Profile of women in prison

For the purposes of the case study, the researcher focused on two women with the status of persons deprived of liberty at the Correctional Institution for Women (CIW), the main penitentiary for women, located in Mandaluyong City, Metro Manila, the capital of the Philippines. She selected these women on the basis of their regular contact as part of her long-term volunteer work in prison; she also had more contact with these women after the pandemic struck.

Both women were in their early to mid-40s. In terms of their ethnic background, one woman identified with a Christianised ethnolinguistic group, particularly Waray, and another identified with an Islamised ethnic group, particularly Maguindanaon.2 One woman identified as a Muslim, while the other identified as a Born-Again Christian; that said, the latter woman embraced Islam (balik-Islam or revert to Islam, in Filipino parlance) upon marrying a Muslim, but converted to Christianity three years prior to the pandemic.

With respect to their civil status, one woman was married and the other widowed. Both women had children, be these biological or adopted. One woman had an adopted child, while the other had three biological children and three stepchildren. In terms of their educational attainment, one woman was a high-school graduate, while the other had completed some years of elementary school. Both women were enrolled in classes as part of the Alternative Learning System (ALS) of the prison.

Both women were serving time in prison for drug charges. One woman had a daughter, who was incarcerated at the same penitentiary, also for drug charges, although they were not co-defendants.

5.1.2 Demographic profile of formerly incarcerated women

The women who formerly held the status of persons deprived of liberty were aged between 33 and 61 years at the time of the interviews; the median age of the women was 44.

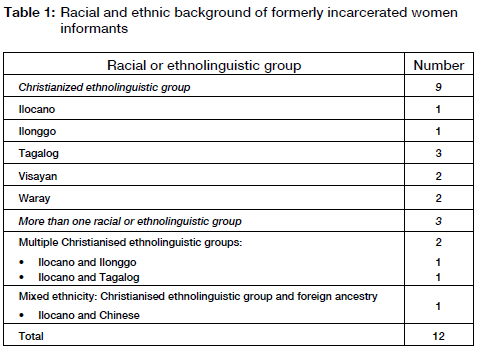

In terms of ethnic background, half of the informants (six women) belonged to Christianised ethnolinguistic groups that were considered minorities in the nation. Of this, one woman identified as Ilocano, one woman as Ilonggo, two women as Visayan, and two women as Waray. Meanwhile, three women identified as Tagalog, a Christianised ethnolinguistic group associated with the dominant culture in the context of Philippine society. The remaining three women traced their roots to more than one racial and/ or ethnic group. One woman identified as having Ilocano and Chinese ancestry. One woman was of Ilocano and Ilonggo descent, while another was of Ilocano and Tagalog descent (see Table 1).

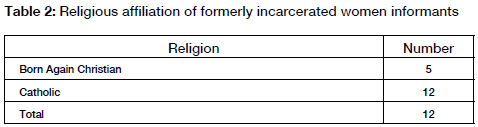

In terms of religion, all women were part of Christian denominations, in that five women identified as Born-Again Christians, while seven women identified as Catholics (see Table 2).

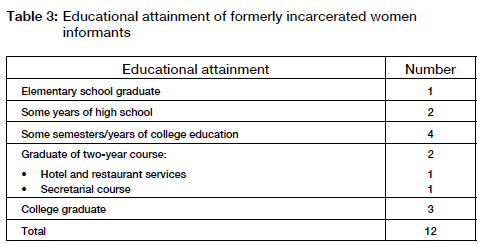

In terms of their educational attainment, one woman had completed elementary school, two women had completed some years of high school, and four women had completed some semesters or years of college education. Moreover, two women had completed two-year courses such as a secretarial course and a course in hotel and restaurant services. Three women were college graduates. Their majors included courses such as psychology, public administration, and tourism (see Table 3).

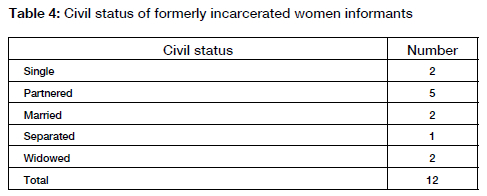

With respect to their civil status, two women were single; five women were partnered, and two women were married. One woman was separated and two women were widowed (see Table 4).

Seven out of the 12 informants were mothers, who had between three to seven children; the average number of children was three. Of this, three women had children who were minors. In the case of two informants, their dependent children lived with them, although one also lived with relatives, on occasion. One woman, who identified as a single parent, disclosed that her young children lived with their father's side of the family. Four women had no children at all.

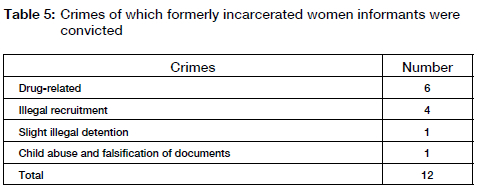

The researcher found that the majority of the formerly incarcerated informants ended up in prison for drug-related offences (6 women). A small minority were convicted of other crimes such as illegal recruitment (4 women); slight illegal detention3 (1 woman), and child abuse and falsification of public documents (1 woman). Upon the appeal of their cases with the higher courts, two informants were eventually acquitted of the criminal charges of which they had been convicted at the lower court. Five women insisted on their innocence and claimed to have been implicated in the offences of close associates or other significant networks through pathways of deception and betrayal (see Table 5).

5.2 Issues and challenges faced by justice-involved women

5.2.1 Incarceration in the time of the pandemic

The women PsDL faced multiple vulnerabilities in prison, which the COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated. Before the lockdown took effect, the researcher had visited CIW five times, between 13 January and 1 March 2020, and noted that low-income women, especially those without regular visitors, faced multiple difficulties in meeting even their basic needs in prison. The women included in this case study were not above this trend. Aside from performing odd jobs in prison, such as doing laundry for other PsDL with more resources and serving in a now-defunct organisation for PsDL who assisted prison staff on duty, these women often relied on donations from faith-based organisations, non-government organisations, and other benefactors.

As persons deprived of liberty, these women immediately felt the impact of the lack of safety nets when the pandemic struck, and President Rodrigo Duterte placed the entire Luzon on lockdown (Al Jazeera 2020b). During the second week of March 2020, a few days before the Luzon-wide lockdown took effect, visits to the penitentiary were suspended for security and health reasons. Some duty-bearers were earlier quoted generalising jails as "safe" and "COVID-free" (CNN Philippines 2020a). Yet the virus spread in both prisons and jails, and even claimed the lives of some PsDL (CNN Philippines 2020b; CNN Philippines 2020c).

To their credit, the prison staff immediately conducted disinfection activities and continued to do so regularly. The prison administration also permitted the delivery of care packages and donations, subject to strict inspection and sanitation protocols. Yet the women still felt the consequences of having limited resources from behind bars, exacerbated by the suspension of visits and the limited number of donations that initially arrived. One of the women, who frequently contacted the researcher, gave regular updates about the turn of events and the impact of the pandemic on their situation. She once disclosed that even her toiletries were severely limited. She revealed: "Even shampoo here is hard to come by. I haven't used shampoo in a month." The other woman, who had been diagnosed with hypertension prior to the pandemic, disclosed that she held on to the medicine donated to her by a religious volunteer. Although the infirmary had medicine for hypertension, the said woman PDL was worried about their supplies running out.

While the prison administration was able to obtain donations of face masks and alcohol, among other necessities, visible space constraints in prison made it difficult to observe health protocols implemented in free society. The policies relating to "social distancing" or "physical distancing" are a case in point, in that these are hard to enforce, due to the congestion of the penitentiary, which is linked to the increased rate of women's incarceration, mainly due to drug-related charges. Prior to the pandemic, it was common for two persons deprived of liberty in CIW to share a single bed. This meant that four people, instead of two, occupied a bunk bed. The same set-up continued, with the exception of PsDL, who had been isolated for demonstrating COVID-19 symptoms or who had been placed in quarantine as a result of contracting the virus. Such living conditions led to the imminent risk of the spread of diseases such as COVID-19.

One of the women, who was an officer at her dormitory and who was also part of the aforementioned organisation that assisted corrections officers on duty, spoke at length about her fear of contracting COVID-19. During one of her telephone calls to the researcher, she shared that those who had a cough were immediately moved to another comparatively "distant" spot in their dormitory, although the limited space made it unrealistic to refrain from close contact; this trend was also reflected in one of the documentaries released about the correctional facility in 2020. Moreover, the woman related how she avoided being confined at the prison chapel, which had been allotted for any PDL showing COVID-19 symptoms. She shared that medicine for fever, such as paracetamol, was more difficult to obtain, due to the restrictions surrounding the pandemic. As such, she took it upon herself to exercise whenever she felt feverish, which she deemed preferrable to being confined at the chapel, where she feared she would get even more ill upon exposure to other PsDL with fever, cough, and other COVID-19 symptoms.

The other woman, who washed the clothes of other PsDL and did other odd jobs to earn a living in prison, contracted COVID-19. She also contacted the researcher and disclosed that she was among the women PsDL transferred to a quarantine facility called "Site Harry"; the facility, created to decongest penal and detention facilities, was housed at the New Bilibid Prison (NBP), the main penitentiary for men, located in Muntinlupa City, Metro Manila (International Committee of the Red Cross [ICRC] 2020). She had stayed there for roughly one month. When asked about the treatment she received, she stated that she did not take any medicine, except for the maintenance medicine for hypertension given to her by a prison volunteer a few weeks before the pandemic broke out in 2020. Other than that, she said she simply rested and ate the food given to her during her time in recovery. She also disclosed that she got tired more easily and was often short of breath, even after she had been declared COVID-free and returned to CIW.

One of the women had a daughter in her early 20s, who was serving time at the same penitentiary. Prior to the pandemic, she had already taken it upon herself to support her daughter, by providing for her food and other necessities in prison, as both of them did not have any visitors to rely on. It can be inferred that the pandemic caused more economic hardship for herself and her daughter. The other woman likewise encountered more economic difficulties caused by the greater limitations in the supply of donations. Although she continued to engage in odd jobs in prison, this was halted for some time when she contracted COVID.

5.2.2 Re-entry issues and experiences of formerly incarcerated women

Most of the former justice-involved women informants came from low-income and working-class communities, to which they returned after their release from prison. For some women, particularly those who got involved in drug-related crimes, their histories of gendered violence and abuse, poverty, and family problems led to their involvement in illegal activity. As formerly incarcerated women, the informants in this study encountered multiple challenges in their reintegration into free society. The COVID-19 pandemic only exacerbated their re-entry challenges.

Some of the re-entry challenges encountered by women in this study include dealing with the stigma associated with being a former PDL; obtaining employment and/or education; accessing public transportation; finding affordable housing, and securing healthcare. It was not uncommon for the informants to have strained relations with their families, some of whom had even disowned them. Those who were acquitted of their criminal convictions were pressured to file claims with the Victims Compensation Program of the Department of Justice (DOJ) on the basis of their unjust imprisonment. That said, the maximum amount that could be given to claimants was Php 10,000 and there was no guarantee that they would immediately receive the funds in full; the failure to file a claim in a timely manner - that is, within a year from their release from prison - led to its forfeiture. This was the experience of one woman, who had been acquitted of drug charges but immediately left for her hometown in the southern Philippines upon her release from prison. She only learned about the Victims Compensation Program years after her release, at which point it was too late to file a claim. Another woman, who stayed at the houses of her siblings in Metro Manila and in Cavite province, was aware of this and claimed that she would immediately file a claim within roughly one month after her release.

Some informants faced tensions arising from the verbal instructions given by President Rodrigo Duterte in September 2019 regarding the "voluntary surrender" of people who had been convicted of heinous crimes and released from prison between 2014 and 2019. According to this directive, the failure of concerned individuals to "surrender" by 19 September 2020 would warrant "shoot to kill" orders (Abad 2019; Gavilan et al. 2019; Rapp/er 2019). This was related to the controversy regarding the implementation of the Good Conduct Time Allowance (GCTA) law, as it applied to persons deprived of liberty, and the disputes regarding the computation of sentence credits, following the near-release of former mayor Antonio Sanchez in August 2019. This development sparked massive public outrage, due to his and his security aides' conviction for the heinous crime of raping and murdering a woman college student, along with her friend, in 1993 (Balinbin & Villegas 2019; Cinco 2019; CNN Phi/ippines 2019).

Five informants, who had been released on parole, checked with their respective parole officers. One obtained an affidavit from the DOJ that declared that she was not among those mandated to "voluntarily surrender" to the nearest penal or detention facility. Yet this dilemma triggered immense anxiety on the part of the women. The fear of losing their jobs and/or dropping out of school, the trauma that they and their families had faced during their arrest, and the prospect of having no visitors if they would report back to prison were among the concerns they faced. One informant did report back to CIW, even if her crime was a drug offence and she had served her sentence, because she feared being targeted as part of President Duterte's "shoot-to-kill" orders. As such, she experienced the restrictions associated with being a "returnee" - that is, a former PDL under the custody of a penal institution - for a prolonged period. She also contracted COVID because she was still among the returnees who remained in CIW when the pandemic broke out, for which it took several months for her to receive clearance to go home.

The women faced other persisting unmet needs, namely further education and skills training, drug rehabilitation, and family reunification and family-related responsibilities. Others faced challenges such as the lure of the underground economy and the risk of recidivism. For instance, one informant experienced being pressured to return to illegal activity through the threat of blackmail by higher echelons in the underground economy.

The women commonly faced intensified challenges relating to their survival as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. This is related to nationwide trends regarding the difficulties in finding work, particularly in the informal labour market and the service sector. True to form, some informants experienced unemployment or sporadic employment. Losing a job or a job offer also impacted on some informants. One informant, who worked at a chocolate shop and as a research assistant to a professor, lost her job when the knowledge of her background as a former PDL surfaced three months or so prior to the pandemic. Her partner, who had worked as a driver for an online shopping company, was laid off within less than two weeks after the lockdown took effect. The recession on account of the pandemic led to immense difficulties in their ability to find work. Another informant, who had just been released from prison six months or so prior to the pandemic, had started working as a nanny for her neighbour. Her neighbour's financial hardships led to her losing her job. Meanwhile, an informant, who had a pending job offer in a nearby province, had to forego this, due to travel bans. She experienced being unemployed for several months before landing a job as a security guard at a school in her hometown. As for another informant, who once operated an internet café, government-imposed restrictions on the operation of non-essential businesses led to difficulties in sustaining her previous business. She and her partner later opened a food franchise, although its operation was also impacted by government regulations as to the level of community quarantine. Other informants, particularly those who were middle-aged or senior citizens, also experienced difficulties in finding work, aggravated by fears about their greater vulnerability to contracting COVID-19; as such, they relied on family members to support them and their daily needs.

The informants who were employed still faced challenges. For instance, one informant, who worked in a business process outsourcing (BPO) company, encountered difficulties in purchasing an extra laptop, which she could use in order to work from home, as her children used the laptop owned by her family for their online classes. Another woman, who was about to start working at a BPO before the pandemic struck, disclosed that she had to leave in less than a year, due to high blood pressure, among other health issues that were brought about by the pandemic, in large part. Others, such as a woman working as a security guard, were constrained by the lack of access to public transportation, leading some to walk to their workplace at the height of the lockdown. Meanwhile, a student-informant experienced the disruptions impacting on educational institutions when classes were suspended during her final semester prior to her graduation.

Hunger and the lack of food security and resources were common experiences among the informants. For instance, one informant was threatened with arrest and later ordered to perform community service for stealing malunggay (horseradish) leaves from the tree of a neighbour who was a barangay (village) official. She insisted that she had intended to ask the barangay official if she could get some malunggay leaves from his tree, but no one was home when she went to his house. She admitted that her desperation drove her to steal, as she and her partner, who had lost his job due to the pandemic, had not eaten for two days. Lacking safety nets, they were often among the people who were hit hardest by the pandemic.

5.3 Service needs

Women in prison face multiple service needs as they continue to serve sentences in a time of pandemic. Aside from basic needs such as food, hygiene kits, alcohol, and face masks, they also confront unique issues stemming from the pandemic. Some prison staff disclosed offhand that they needed people to provide seminars or motivational talks on such issues as anxiety, depression, anger management, and preparation for reentry, among other topics, as the need for these was more pronounced in the time of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, formerly incarcerated women encounter multiple challenges in their reintegration into society, such as returning to disfranchised communities, obtaining employment, finding affordable housing, and access to social services. They also face multiple unmet needs, namely further education, healthcare, drug rehabilitation, and family reunification. Counselling for unaddressed issues, such as gendered violence and abuse and drug addiction, is also crucial. As these issues most likely influenced their involvement in illegal activity, these festering concerns could thus impact on their ability to cope with other related challenges in their transition to independent living. The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified these issues and service needs. Comprehensive services are needed to address the issues of women who served time behind bars, especially drug rehabilitation and unemployment, so as to counter the lure of the underground economy and recidivism, especially as the pandemic continues to drag on.

5.4 Of liminality and shared vulnerability in the time of the pandemic

Being an unprecedented health and social emergency, the pandemic has magnified the vulnerability of justice-involved women, be they current or former persons deprived of liberty. The current situation of women in prison and women working to rebuild their lives in free society reflects much liminality, given the disorientation and ambiguity that characterise this time of pandemic and the unlikelihood of returning to pre-pandemic behaviours and lifestyles despite the ongoing preparations for the transition to the "new normal", and the improbability of simply resuming former statuses and relationships in the event of their release from prison. At the same time, these liminal spaces and situations present opportunities to rethink and recalibrate new ways of being human.

The liminality of the situation of currently and formerly incarcerated women renders them vulnerable. At the same time, it exposes people's shared vulnerability, as exemplified by the instances during which duty-bearers such as prison staff, family members and other significant networks of current and former women PDL, and other members of their communities contracted COVID-19 and/or experienced multiple hardships and constraints associated with the pandemic.

This sense of shared vulnerability compels concerned citizens, civil society, and the church and faith-based organisations to reflect upon new ways to cater to the needs of justice-involved women more effectively, especially in a period of metamorphosis. In this time of liminality, people's shared vulnerability can be channelled in an agentic way as a source of learning and as a catalyst for engaging in gender- and culturally sensitive responses and interventions that promote the dignity of currently and formerly incarcerated women and fostering compassionate, life-giving communities for their benefit.

6. THEOLOGICAL REFLECTIONS AND PASTORAL INTERVENTIONS

Visiting the imprisoned is one of the corporal works of mercy: "I was in prison and you visited me" (Matthew 25:36). In this time of the pandemic, reaching out not only to people behind bars, but also to formerly incarcerated individuals - a population group of which current and former justice-involved women are part - is a need to which the church and faith-based organisations are compelled to respond.

Some teachings that are part of Catho/ic Socia/ Teaching are essential in building and promoting life-giving communities for justice-involved women. One of the themes of Catho/ic Socia/ Teaching emphasises the life and dignity of the human person.

The Catholic Church proclaims that human life is sacred and that the dignity of the human person is the foundation of a moral vision for society. This belief is the foundation of all the principles of our social teaching. We believe that every person is precious, that people are more important than things, and that the measure of every institution is whether it threatens or enhances the life and dignity of the human person (USCCB 2021).

This viewpoint holds that each person is valuable, worthy, and deserving of dignity. As such, the moral fabric of society can be assessed based on the extent to which its institutions and its very structure promote the life and dignity of people, regardless of their social background. This teaching can be utilised to make the case for valuing and promoting the life and dignity of currently and formerly incarcerated women, to demonstrate that they matter, regardless of their legal transgressions. This resonates with biblical teachings that emphasise the avoidance of judging others. As part of one of the major social institutions that promotes social stability, the church is thus compelled to be an instrument of solidarity in upholding the dignity of current and former justice-involved women, particularly in the time of the pandemic, which has exposed numerous social inequalities at their core.

Another salient theme of Catho/ic Socia/ Teaching focuses on the preferential option for the poor.

A basic moral test is how our most vulnerable members are faring. In a society marred by deepening divisions between rich and poor, our tradition instructs us to put the needs of the poor and vulnerable people first (USCCB 2021).

This teaching is very timely in terms of responding to the call to be of service to justice-involved women. Women in conflict with the law are among the poorest of the poor, in the sense of being deprived of freedom -an essential resource for human flourishing - and are thus as vulnerable as they can get. Formerly incarcerated women remain vulnerable, given the multiple barriers they confront in their readjustment to free society and the stigma they face due to their background. The church is thus compelled to be an instrument of compassion in the face of multiple vulnerabilities that current and former justice-involved women confront, particularly in the time of a pandemic.

Feminist theology recognises the unique role of gender in shaping women's circumstances and opportunities, including the lived experiences of women involved in the justice system. Intersectional theology recognises overlapping inequities relating to gender, race, social class, and other social positions, and the impact thereof on people's opportunities (Kim & Shaw 2018). The nexus of feminist theology and intersectional theology can be used to build life-giving communities in areas where these are especially needed, such as among women currently or formerly involved in the criminal justice system. This entails recognising that women's conflicts with the law often occur because they are women, as a consequence of living in a society that grants them limited options or that compels them to exercise agency in ways that might lead to their involvement in illegal activity or implication in the offences of others.

The first version of the creation story in the Book of Genesis underscores the equality of women and men: "So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God, he created them; male and female he created them" (Genesis 1:27). The same passage can be used to emphasise the inherent dignity of women currently or formerly in conflict with the law. Meanwhile, a passage in St. Paul's Letter to the Galatians points to the abolition of social differences among people, so as to promote equality within the Christian faith: "There is no longer Jew nor Greek, there is no longer slave nor free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus" (Galatians 3:28). According to Schussler Fiorenza (1983:213), this biblical passage asserts that distinctions based on social position, including gender, social class, and perhaps even legal background, are insignificant, given the presumed equality of all people in the faith. These teachings can be used to eradicate cultural practices that perpetuate gender inequality and other interrelated oppressions and to empower women relegated to the margins of society not only because of their gender and other social locating factors, but also their history of legal transgressions. This need is especially vital in promoting a life-giving community, especially as the pandemic and its related effects continue to drag on.

Pastoral care for justice-involved women is a need that existed prior to the pandemic and is strongly felt as the pandemic drags on. The impact of social isolation, multiple disruptions in one's living situation, the strain of limited resources and safety net, and grief due to the death of loved ones to COVID-19 and related complications, are among the common concerns that people face as a result of the pandemic. Currently and formerly incarcerated women are not above these issues. It is important for pastoral interventions to take a non-judgemental approach and to promote inclusivity by extending such services, regardless of religious affiliation. It is hoped that this will pave the opportunity for the expansion of church services to include groups of women who have traditionally been overlooked, such as those with histories of involvement in the criminal justice system.

The link between the Catholic Church and state politics in Philippine society has been documented throughout history. This is evidenced by the mobilisation of the Catholic Church and other religious denominations in response to social and political issues (Bautista 2020; Buenaventura 2016). However, religious dynamics have also perpetuated patriarchal practices and views that impact on women. The entrenchment of faith in the cultural fabric and existing gender stereotypes that compel women to be morally upright and "pure", as exemplified by the Virgin Mary, among other factors, are likely to influence the limitations in responses that seek to ease the hardships experienced by justice-involved women, particularly in the time of a pandemic. The stigma attached to currently and formerly incarcerated women could possibly account for the hesitation of communities of the faithful to get involved - with the exception of faith-based organisations and pastoral agents that have assisted them through various programmes.

Given the restrictions in visiting prisons in the Philippines, the involvement of faith-based organisations over the past year has mainly taken the form of the delivery of donations for PsDL. However, some Catholic priests have continued to say Mass in prison, albeit in more confined settings. A possible area of intervention lies in pastoral services that religious and lay persons could provide virtually such as counselling, motivational talks, online recollections, and the like. These activities entail close coordination and consultation with the prison administration and staff, given the need to balance internet connectivity issues with security concerns in prison. Moreover, the church can serve as an agent in the promotion of restorative justice, by taking part in civil society initiatives, particularly advocacy work and lobbying activities that highlight the need for more humane responses, rather than punitive ones, toward people who commit legal transgressions, particularly those with limited histories of illegal activity and those involved in non-violent and non-heinous crimes. Such initiatives should include and benefit women in the criminal justice system, in view of their more vulnerable social positions and relational responsibilities and the vicious cycle of criminality that entraps their families.

Another area of intervention lies in support services to aid soon-to-be-released or formerly incarcerated women in their transition to independent living. The Catholic Church could help provide comprehensive pastoral and social services such as transportation, housing, healthcare, livelihood assistance, counselling, and spiritual or religious activities (as needed) to former PsDL. The formation of support groups for formerly incarcerated women is also essential as a source of encouragement in their readjustment to free society. All these initiatives are helpful in building life-giving communities for justice-involved women.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abad, M. 2019. Unqualified GCTA returnees lose jobs, are detained for months. Rappler 15 December. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/40EpaHC [6 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Al Jazeera 2020a. Duterte extends Philippines's coronavirus lockdown to April 30. 7 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3KtsUpR [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Al Jazeera 2020b. Timeline: How the new coronavirus spread. 20 September. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/9/20/timeline-how-the-new-coronavirus-spread [11 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Amnesty International 2020. Philippines: President Duterte gives "shoot to kill" order amid pandemic response. 2 April. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/43KzzTV [10 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Balinbin, A.L. & Villegas, V.M.M. 2019. Duterte ruled out Sanchez early release - aide. Business World 26 August. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3zptpe8 [2 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Bautista, J. 2020. Catholic democratization: Religious networks and political agency in the Philippines and Timor-Leste. SOJOURN: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 35(2), pp. 310-342. DOI: 10.1355/sj35-2e. [ Links ]

Buenaventura, M.I.T. 2016. The politics of religion in the Philippines. Asia Foundation 24 February. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://asiafoundation.org/2016/02/24/the-politics-of-religion-in-the-philippines/ [15 January 2023]. [ Links ]

BBC News 2020. COVID-19 pandemic: Tracking the global coronavirus outbreak. 11 October. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-51235105 [11 November 2021]. [ Links ]

Becker, E. 2020. How hard will the coronavirus hit the travel industry? National Geographic 2 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://on.natgeo.com/3K8A0id [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Berkley center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs 2013. The Philippines: Religious conflict resolution on Mindanao. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.berkleycenter.georgetown.edu [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Bismonte, C. 2020. The disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on migrant workers in ASEAN. The Diplomat 22 May. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3zpjYeT [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Calonzo, A. 2020. Philippines eases distancing rules, allows more airplane passengers. Bloomberg 10 September. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://bloom.bg/3MT6Ma6 [2 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Calonzo, A. & Jiao, C. 2020. Duterte expands Philippine lockdown to 60 million people. Bloomberg 15 March. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://bloom.bg/43GoByO [2 February 2022]. [ Links ]

Cavallo, J.J., Donoho, D.A. & Forman, H.P. 2020. Hospital capacity and operations in the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic - Planning for the patient. Journal of American Medical Association Health Forum 17 March. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3K9c7H4 [18 November 2020]. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0345 [ Links ]

Cepeda, M. 2020. Face masks, physical distancing: House bill sets "new normal" in post-lockdown PH. Rappler 28 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.rappler.com/nation/house-bill-require-face-mask-physical-distancing-after-lockdown [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Chesney-Lind, M. & Pasko, L. 2004. The female offender: Girls, women, and crime. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452232157 [ Links ]

Cinco, M. 2019. Public outrage stopped Aug. 20 Sanchez release, his family says. Philippine Daily Inquirer, 28 August. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1158325/public-outrage-stopped-aug-20-sanchez-release-his-family-says [2 February 2022]. [ Links ]

CNN PHILIPPINES 2019. Convicted ex-mayor Sanchez ordered released August 20, family says. 27 August. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3m2bBCJ [2 February 2022]. [ Links ]

CNN PHILIPPINES 2020a. Inmates are safer in our jails amid pandemic - BJMP 8 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/432rSZe [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

CNN PHILIPPINES 2020b. Eighteen inmates, one jail worker in Women's Correctional contract COVID-19. 21 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3Ksgsql [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

CNN PHILIPPINES 2020c. Two inmates from Women's Correctional die of COVID-19 - Bucor. 28 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3m2bebj [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Davies, s. & cook, D. 1999. The sex of crime and punishment. In: S. Cook & S. Davies (eds), Harsh punishment: International experiences of women's imprisonment (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press), pp. 53-80. [ Links ]

Esguerra, D.J. 2020. Metro Manila placed under 'community quarantine' due to COVID-19. Philippine Daily Inquirer 12 March. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/40yu2NP [8 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Gai, R. & Tobe, M. 2020. Managing healthcare delivery system to fight the COVID-19 epidemic: Experience in Japan. Global Health Research and Policy 5:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00149-0 [ Links ]

Gavilan, J., Buan, L, Talabong, R. & Abad, M. 2019. Fixing the Bureau of Corrections: Government walks a tightrope. Rappler 18 December. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3U7NKy3 [28 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Hapal, K. 2021. The Philippines' COVID-19 response: Securitising the pandemic and disciplining the pasaway (translation: violator of rules). Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 40:2. Pp. 224-244. DOI: 10.1177/1868103421994261 [ Links ]

Howe, A. 1994. Punish and critique: Towards a feminist analysis of penalty. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Human Rights Watch 2020. Philippines: Prison deaths unreported amid pandemic. 28 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3MbES8z [28 October 2020]. [ Links ]

International committee of the Red cross 2020. Halting the spread of COVID-19 in congested detention facilities. 10 June. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.icrc.org/en/document/halting-spread-covid-19-congested-detention-facilities-0 [28 October 2020]. [ Links ]

International Labor organization 2020. ILO sectoral brief: The impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3lVs23T [9 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Jeffries, S., Ohuenurah, C. & Wallis, R. 2019. Gendered pathways to prison in Thailand for drug offending? Exploring women's and men's narratives of offending and criminalization. Contemporary Drug Problems 46(1):78-104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450918818174 [ Links ]

Jeffries, S., Rao, P., Ohuenurah, C. & Fitz-Gerald, M. 2021. Extending borders of knowledge: Gendered pathways to prison in Thailand for international cross border drug trafficking. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. DOI: 10.1080/13218719.2021.1894263 [ Links ]

Kabiling, G. 2020. Multi-sectoral approach in COVID campaign cited. Manila Bulletin 5 August [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/41AJWb3 [8 September 2020] [ Links ]

Kaul, V., Shah, V.H. & El-Serag, H. 2020. Leadership during crisis: Lessons and applications from the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastroenterology 159(3):809-812. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.076. [ Links ]

Kim, G.J. & Shaw, S.M. 2018. Intersectional theology: An introductory guide. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jxtv47w2f6 [ Links ]

Lema, K. 2020. Like wartime: Philippine doctors overwhelmed by coronavirus deluge. Reuters 27 March. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-philippines-idUSKBN21E1X8 [10 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Madarang, C.R. 2020a. From ECQ to modified ECQ and modified GCQ, what do these phrases mean? Interaksyon 14 May. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/41hvBRn [10 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Madarang, C.R. 2020b. To help trike drivers, vendors, Robredo takes QC markets online as residents observe social distancing. Interaksyon 12 May. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3LjEWmd [10 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Mendez, C., Cabrera, R., & Talavera, C. 2020. IATF allows more activities under GCQ. Philippine Star 4 July. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3L7etYQ [8 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Nagel, I.H. & Johnson, B.L. 2004. The role of gender in a structured sentencing system: Equal treatment, policy choices, and the sentencing of female offenders. In: P.J. Schram & B. Koons-Witt (eds), Gendered (in)justice: Theory and practice in feminist criminology (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.), pp. 198-235. [ Links ]

Norwegian Institute of Public Health 2020. Social and economic vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3ZDicBs [12 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Pazarbasioglu, C. & Kose, M.A. 2020. Unprecedented damage by COVID-19 requires an unprecedented policy response. The Brookings Institution 10 July. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3nI4MqF [12 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Pedersen, C.L. & Ritter, T. 2020. Preparing your business for a post-pandemic world. Harvard Business Review 10 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://hbr.org/2020/04/preparing-your-business-for-a-post-pandemic-world [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Petersilia, J. 2003. When prisoners come home: Parole and prisoner re-entry. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Philippine Human Rights Information Center & Women's Education, Development Productivity And Research Organization [Philrights & Wedpro] 2006. Invisible realities, forgotten voices: The women on death row from a gender and rights-based perspective. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Human Rights Information Center. [ Links ]

Ranada, P. 2020. Luzon-wide lockdown after April 30 not needed, health experts tell Duterte. Rappler 21 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.rappler.com/nation/health-experts-tell-duterte-luzon-lockdown-after-april-30-2020-not-needed [8 September 2020] [ Links ]

Ransley, C. 1999. Unheard voices: Burmese women in immigration detention in Thailand. In: S. Cook & S. Davies (eds), Harsh punishment: International experiences of women's imprisonment (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press), pp. 172-188. [ Links ]

Rappler 2019. 1,525 returnees to spend Christmas in prison 3 months after GCTA controversy. 24 December. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3m7n6Zx [6 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Renzetti, C.M. & Goodstein, L. (Eds) 2001. Women, crime, and criminal justice. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury. [ Links ]

Richie, B.E. 2001. Challenges incarcerated women face as they return to their communities: Findings from life history interviews. Crime and Delinquency 47(3):368-389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128701047003005 [ Links ]

Richter, F. 2020. COVID-19 could set the global tourism industry back 20 years. World Economic Forum 2 September. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/42ZaLY9 [11 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Romero, A., Mendez, C. & Crisostomo, S. 2020. "Modified ECQ Versus GCQ: Why ECQ in NCR, Laguna, Cebu City Cannot Be Lifted." One News 13 May [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.onenews.ph/modified-ecq-versus-gcq-why-ecq-in-ncr-laguna-cebu-city-cannot-be-lifted [8 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Schleicher, A. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on education: Insights from education at a glance 2020. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3m4cSJq [15 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Schussler Fiorenza, E. 1983. In memory of her: A feminist theological reconstruction of Christian origins. New York: Crossroad. [ Links ]

Searight, A. 2020. The economic toll of COVID-19 on Southeast Asia: Recession looms as growth prospects dim. Center for Strategic Studies and International Studies 14 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3m4d5fG [15 November 2020]. [ Links ]

See, A.B. 2020. Hidden victims of the pandemic: The old man, the jail aide, and the convict. Rappler 22 June. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/40XleBl [10 October 2020]. [ Links ]

2021. Rodrigo Duterte is using one of the world's longest COVID-19 lockdowns to strengthen his grip on the Philippines. TIME 15 March. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/43JLfXm [8 March 2022]. [ Links ]

Steffensemeier, D. & Allan, E. 2004. Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. In Schram, P.J. & B. Koons-Witt (eds.) Gendered (in)justice: Theory and practice in feminist criminology (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.), pp. 95-125. [ Links ]

Stormer. C. 2020. Hope in short supply amid pandemic and economic collapse. Spiegel International 24 August. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3KGzh82 [10 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Taylor, D.B. 2020. A timeline of the coronavirus pandemic. The New York Times 6 August. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/article/coronavirus-timeline.html [10 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Thomas, J. 2003. Gendered control in prisons: The difference difference makes. In: B.H. Zaitzow & J. Thomas (eds), Women in prison: Gender and social control (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner), pp. 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781588269454-003 [ Links ]

Tomacruz, S. 2020. Duterte extends Luzon lockdown until April 30. Rappler 7 April. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3mIRMkh [15 September 2020] [ Links ]

Ty, R. 2010. Indigenous peoples in the Philippines: Continuing struggle. Focus Asia-Pacific 62:6-9. [ Links ]

United States conference of catholic Bishops 2021. Catholic Social Teaching: Challenges and directions. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3ZCbTOg [13 September 2021]. [ Links ]

Vallejo, B.M. & ong, R.A.C. 2020. Policy responses and government science advice for the COVID 19 pandemic in the Philippines: January to April 2020. Progress in Disaster Science 7: 100115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100115. [ Links ]

Veloso, D.T.M. 2016. Of culpability and blamelessness: The narratives of women formerly on death row in the Philippines. Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 16(1):125-141. [ Links ]

Veloso, D.T.M. 2022. Gendered pathways to prison: The experiences of women formerly on death row in the Philippines. In: S. Jeffries & A. Jefferson (eds), Gender, criminalisation, imprisonment, and human rights in Southeast Asia (Bingley, UK: Emerald), pp. 125-137. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80117-286-820221008 [ Links ]

Villero, J.M. 2006. Mothering in the shadow of death. Human Rights Forum 3(1&2):27-30. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3nEYUOG [9 April 2009]. [ Links ]

World BANK 2020. The global economic outlook during the COVID-19 pandemic: A changed world. 8 June. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3zrYw8X [16 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Yee, J. 2020. Longest lockdown, lost opportunities: PH COVID-19 cases go past 300,000. Philippine Daily Inquirer 27 September. [Online]. Retrieved from: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1340659/longest-lockdown-lost-opportunities-300k-cases [10 October 2020]. [ Links ]

Date received: 14 July 2022

Date accepted: 12 December 2023

Date published: 26 April 2023

1 A "justice-involved" person pertains to an individual who has been involved with the justice system, such as through incarceration or being on parole. For the purposes of this paper, the term "justice-involved women" will be used interchangeably with "women in conflict with the law" or "women formerly in conflict with the law".

2 In the Philippines, people are distinguished according to race, ethnicity, and religion. Race and ethnicity tend to overlap with religion because the Spanish and American colonial eras historically led to the institutionalisation of racial categories, namely Christian, Muslim, and indigenous peoples (IPs), depending on whether their ancestors had converted to Christianity and assimilated to colonialism, or embraced Islam or maintained their indigenous religion and thus resisted colonialism. Even people's ethnic heritage is associated with ethnic groups that had historically converted to Christianity or Islam or retained their ancestral religion. The stereotypes that are associated with being a Christian and a Muslim, as well as an indigenous person, tend to overlap with racial and ethnic stereotypes. In addition, people's ethnic groups are also termed ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippine context, in that their ethnicity is distinguished by the language/s they speak (Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs [2013]; Ty [2010:6-9]).

3 This is a kidnapping-related offence, but with a lighter penalty.