Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.42 n.2 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v42i2.12

ARTICLES

Finding oneself? Contemplating on paintings with a religious theme in clinical pastoral care

F. HermI; V. KesslerII; E. KloppersIII

IAltmühlseeklinik, Stiftung Hensoltshöhe,Bavaria, Germany. Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa. E-mail: friedbert.herm@gmx.net; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4104-024X

IIGBFE, Gummersbach, Germany; Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology,University of South Africa. E-mail: volker.kessler@gbfe.eu; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8420-4566

IIIDepartment of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa. E-mail: elsabekloppers@gmail.com; ORCID:https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8790-324X

ABSTRACT

This article is based on intra- and interdisciplinary explorative research on contemplating art with a religious theme in the context of clinical pastoral care. The study, done in a rehabilitation hospital in Bavaria, Germany, explores the emotions, feelings, and thoughts aroused by contemplating on Rembrandt's painting, The return of the prodigal son. It includes guided observations of the painting, voluntary feedback on forms, and eight interviews on what could be observed under the aspects of self-reflection, identification, and reorientation. Aspects of aesthetics, biography, religion, and emotion are also observed. The evaluation of the aesthetic reception shows two types of reactions, namely identification with a person or a theme of the painting. It is observed that self-reflection, an important factor for reorientation during the process of clinical pastoral care, is present in all interviewees. Each interviewee presents an individual characteristic related to their life situation. Core themes corresponding to the painting's content are guilt, forgiveness, mercy, and reorientation. The practice of contemplation on paintings with a religious theme, using methods common in the social sciences and empirical theology, represents one possibility among many in the field of clinical pastoral care. The study provides new information on the therapeutic possibilities of creative experiences, by contemplating on paintings that can be explored further.

Keywords: Clinical pastoral care, Pastoral therapy, Contemplating on paintings, with a religious theme, Sacred art

Trefwoorde: Kliniese pastorale sorg; Pastorale terapie, Nadenke oor skilderye met, 'n religieuse tema, Heilige kuns

1. INTRODUCTION

An interdisciplinary and explorative research study on contemplating art with a religious theme in the context of clinical pastoral care, done in a rehabilitation hospital in Bavaria, Germany, explored the emotions, feelings, and thoughts aroused by contemplating on Rembrandt's painting, The return of the prodigal son. It consisted of guided observations of the painting, voluntary feedback on forms, interviews on what could be observed under certain aspects, a qualitative analysis of the interviews, and a report of the specific findings. This article describes the process of empirical research in a context of pastoral therapy where art with a religious theme is used. The research design and methods of the study are given, followed by the report on the results, discussed in relation to the background and current research on the theme. It concludes with a summary of the research findings, as well as further possibilities to explore.

The importance of self-reflection and the therapeutic benefit of perceiving one's own emotions and needs are well-known in psychotherapy. It is acknowledged that self-reflection is sometimes difficult, but not impossible. In therapeutic processes, there are helpful tools to understand oneself and to work on personal needs and feelings (Fritsch 2012:63-71). Similar possibilities to lead people to self-reflection are found in clinical pastoral care. In the practice of contemplation on paintings and observing themes and figures in the paintings, pastoral care uses certain techniques from individual psychology to raise awareness on deeper layers of personal feelings and thoughts (similar to early childhood memories, dreams, and imaginative techniques) that could assist one in coming to a better understanding of oneself, one's life, and one's personal lifestyle. Paintings with a religious theme can be an important bridge to narrative language in pastoral discussions and, in certain contexts, an interface between biographical meaning and the experience of the sacred in everyday life (Grevel 2007:290-291). This approach could foster self-reflection by consciously striving for the possibility of gaining knowledge of oneself and one's own perception of things with a resulting broadened perspective (Otte 2018:106). Aiming to "support the shaping of life", the intervention by contemplation on paintings represents one concept among many in pastoral care (Pohl-Patalong 2007:676-677).

The research study, from which this article flows, focused on creative processes of experience of a cognitive and emotional nature that can be evoked by contemplating on a painting with a religious theme in the pastoral process, in this case The return of the prodigal son. Describing Rembrandt's paintings with a religious theme as "mysterious windows", through which the viewer can enter the kingdom of God, Nouwen (2016:15-31) gives a spiritual interpretation of The return of the prodigal son, accompanied by spiritual impulses and sociocultural interpretations that present therapeutic possibilities. The South African theologian John de Gruchy (2008:235) mentions Rembrandt's masterpieces as sacred art in the special sense that his paintings with biblical content touch on fundamental questions of human life, without the scenes depicted appearing religious or biblical in themselves. Rembrandt painted The return of the prodigal son, the Annunciation to Mary, and Simeon and the Infant Jesus with people dressed in the clothes of his time. The scenes are taken from everyday life and do not initially appear religious to the viewer. Only the reference to the biblical content and the people depicted make these paintings sacred art. The painting is thus open enough to be used in various contexts, even if one would not regard oneself explicitly as religious. These are all valid reasons for choosing the specific painting for a research project focusing on exploring the pastoral, spiritual and therapeutic effects of a painting with a religious theme on patients in a hospital.

2. BACKGROUND

Historical art research recognises that paintings with a religious theme have their own value. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the phrase "devotional paintings" came up. In contrast to historical paintings and representational paintings of the late Middle Ages, the devotional paintings allowed a contemplative immersion into the painting with a resulting emotional experience. The subject was offered the opportunity to unite spiritually with the object in contemplation. The devotional paintings often depicted scenes of the Passion and the intention was an emotional experience - "the eyes should imprint the painting on the heart" (Noll 2004:297).

The 1980s saw the starting point for the use of art with a religious theme and an aesthetic approach in religious education in Germany when, in the methodology of religious education, images as learning opportunities were described in a completely new way. This made it possible to engage deeper with works of art and take greater account of the findings of art studies in theological research, since the visual material was perceived as an independent medium. The German theologians and religious educators Rita Burrichter and Claudia Gartner (2014:18-19) believe that the confrontation and analytical examination of shape, form, and colour, as well as the specific conditions of perception of visual art present viewers with challenges that can be used constructively in terms of art didactics and religious education. Because visual objects break up viewing habits, show new perspectives, impress as well as irritate, they develop a "formative power" (Burrichter & Gartner 2014:19). The confrontation with works of art leads beyond aesthetic perception into a discourse about the theological tradition. Art didactics thus enable training in religious perception, reflection, and expression in religious education.

In 2001, the British sociologist Gillian Rose (2016:24-47) proposed researching visual materials that take into account four aspects of a critical methodology of the visual. Rose describes these four fundamental aspects in the production (creation) of the visual object, its optical representation (image), the publication (circulation), and the recipients (audience). Based on the techniques of production and composition of the visual object, an interpretation of the representation itself is possible (Rose 2016:56-84). Rose (2016:85-105) describes the method of step-by-step content analysis as well as a cultural analysis. The need for critical self-reflection on the part of the interpreter is particularly emphasised, since the selection of the objects, the choice of analytical methods, and their interpretation depend on the subjectivity of the researcher (Rose 2016:186-219). Finally, research with visual media should include a critical assessment of the audience, taking ethical aspects into account (Rose 2016:357-372).

According to another method for analysing the visual, developed by the Austrian sociologist Roswitha Brecker (2012:146), the generation of meaning is controlled by processes of symbolisation, of which language is an essential process, but not the only one. It is supported by other symbolisation processes such as music, images, and rituals. Images play a role in individual states and perceptions, background knowledge, concepts, and attitudes towards the environment both in the production process and in the process of reception. This results in individual perspectives for observation and interpretation, which unfold in a performative effect on the viewer, due to how they are symbolised. During the creation of a picture, perspectives, compositions, and structures are chosen, more or less consciously, which can be seen and recorded consciously or unconsciously in the perception of the picture, but they do not necessarily have to be perceived.

The theologian Jan Grevel (2007:282-291) describes three methodical steps of qualitative visual analysis in the context of empirical theology, with reference to methodology in the social sciences. In the pre-iconographic analysis, individual elements of the visual object are perceived, and components are described in the "sense of phenomenon", where the perspective of the producer, the so-called "point of view", is important. Visual components and aesthetic elements also play an important role on this level of analysis. In a second step of the qualitative method for interpretation of visual objects, the so-called reconstruction analysis examines the actual content with the aim of congruence between formal and content-related statements. On this level, the perception of the individual visual elements, accompanying ideas about the persons or objects depicted and the aesthetic components are analysed in terms of their meaning and reconstructed into a coherent symbolic form of expression of the visual object and text. Grevel (2007:284) calls this step of qualitatively approaching the object "analysis of meaning". In the last step of the qualitative analysis, there is a sociocultural interpretation, during which both historical and biographical information of the production, as well as social aspects of the reception of the visual object are brought into the process and discourse of the analysis (Grevel 2007:284-285).

Applied in the field of pastoral care, Steinmeier (2020:382) describes the correspondence between inside and outside in sacred art and images -anthropologically and spiritually - as follows:

In the search for representation, external images can show traces of one's own inner images, images of life, of oneself, of relationships with others, and God.

Visual art objects bring a different level into human interaction, which can open new horizons of interpretation, confrontation with the unknown, as well as consolation and hope. Paintings with a biblical theme, in particular, offer a symbolic language that can create "bridges of trust" and make an extended offer of communication, especially in a burdened life situation. Haussmann (2021:203-204) is also convinced that visual materials offer strong therapeutic power in spiritual and pastoral care. It requires, however, that a certain ambivalence of visual communication must be endured and constructively shaped.

3. METHODS AND RESEARCH DESIGN

The process of research on contemplating on a painting with a religious theme is dependent on the various methods for hermeneutically interpreting the relevant work of art, personal narratives, metaphors, life stories, and examples of lived religion (Grab 2006). Qualitative research methods, as suggested by Heimbrock and Meyer (2007:11-16), are used to interpret the narratives and accounts from the participants' world of experience in a methodically reliable way, make trustworthy analyses of the subjective individual responses, and draw solid conclusions about the reception and acceptance of the observed painting.

According to the authors from different disciplines (Rose 2016:24-27; Grevel 2007:282-285; Breckner 2012:145-151), it is necessary to avoid a premature and rapid interpretation of a painting in qualitative analysis. Perception should rather be delayed by various guided and controlled steps. In this regard, care was taken methodically to ensure that the perception of the painting and its interpretations were not rashly and solely limited to subjectivity, but in accordance with the analytical details of the painting. To ensure this, the contemplation sessions took place during four morning devotions in the rehabilitation hospital, which were at least a week apart, but were related to one another in terms of content. Rembrandt's The return of the prodigal son was presented, but each of the four sessions had a different focus on the visual aesthetics and content, according to the content of the book The return of the prodigal son - A story of homecoming (Nouwen 2016:31-139).

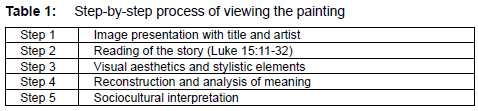

For the analysis of the painting, we used the explanations of Grevel (2007:279-291) from the theological research practice of empirical theology as a methodological basis. This method uses three modes of analysis in four steps. The first step approaches the aesthetics of the painting, by describing light and shadow, colours and stylistic elements, as well as techniques of the artist or producer. In a second step, the reconstruction analysis proposed by Grevel (2007) examines the actual content of the painting to establish congruence between formal and content-related image statements. Thirdly, the perception of the individual elements of the painting, ideas about the depicted people, and the spatial components are analysed and reconstructed into a coherent symbolic form of expression of painting and text. The last step of this method is the sociocultural interpretation, in which both historical information from the production of the painting and sociological aspects of the reception of the painting are brought into the analysis process (Grevel 2007:284-285). Table 1 shows the methodological sequence in four steps used for observation of the painting, with the additional step of reading the story of The return of the prodigal son:

Information for this study was obtained by collecting demographic and quantitative data from the participants through feedback forms with open questions and a focus on the thoughts and feelings experienced while viewing the painting. Sampling of participants for the interview was established via the feedback forms. Recruitment thus included stepwise sampling, by first offering the voluntary participation in the contemplation sessions and then evaluating the anonymous feedback forms, followed by offering the possibility of exploratory interviews. Access to the contemplation sessions and interviews were voluntary. For comparability and qualitative analysis of the answers, structured interviews were chosen with guideline questions that focused on the subjective world of experiences of emotion and thought of the participants (Flick 2012:194-202). The focus was on exploring the feelings and thoughts the participants had experienced and on the aspects of self-reflection, identification, and possible reorientation.

From an interdisciplinary approach, a psychologist, a counsellor, and a physician developed the methodically appropriate questions of the interviews together and tested these in a pilot study prior to the main interviews. These questions, in addition to an introductory question, followed by more in-depth questions and then a final question, enhanced each other to not only address the subjectivity of the individual, but also, through a deliberately open questionnaire, to encourage the interviewees to communicate as freely as possible in the sense of a productive narrative. The aim was to work out the supporting factors in the participants' creative world of experience in the responses to observing the painting. For this purpose, we carried out eight independent interviews with guided questions, made audio recordings, transcribed the answers, and then later analysed the content.

The systematic evaluation of the interviews took place in the form of a qualitative analysis of the content by category-forming text analysis of the transcripts. The categories used were obtained inductively in the mentioned pilot phase. The hermeneutic access to the collected qualitative data of the interviews was chosen again in a step-by-step analysis, as proposed by Kuckartz (2018:23) in the field of educational sciences. Methodologically, a structuring, evaluative, and type-specific classification was carried out in the following steps: transcription; individual analysis; generalised analysis, and control phase. The exploratory research project received the approval of the Research Ethics Review Committee of the College of Human Sciences at the University of South Africa in January 2021. It was envisaged that participation was voluntary, while the anonymity of the data collected was guaranteed to meet the requirements of the ethical code of the German Society for Sociology and the Professional Association of German Sociologists (Ethik-Kodex 2017).

The questionnaires were only given to the participants after explaining the voluntary nature, the guarantee of anonymity, and the advantage for participants of working more intensively with the painting after the end of the contemplation session. In addition, the participants in the interviews were informed on how the evaluation, presentation, and publication of the results were planned. They were also informed on how they could gain the opportunity for insight into the research results. The data collection, digital storage, and publication were carried out according to the German Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz 2018).

4. ANALYSING THE INTERVIEWS

Research started with the four contemplation sessions, followed by the eight interviews and feedback forms in the spring of 2021. The transcripts of the interviews contained a total of 56 narrative answers, analogous to the seven interview questions asked in eight interviews, which could be sequenced in terms of content and assigned to the mentioned categories. Each interviewee could also be assigned an individual, specific main characteristic or pseudonym related to his/her life situation. This was confirmed in each case by the three interviewers in a mutual comparison.

• Interview A (The Professional, 1,163 words, 3 pages, 115 lines) took place in a relaxed atmosphere with an interviewee, who seemed to be well versed in looking at paintings and Rembrandt motifs. This prior knowledge was addressed twice in the interview and the interviewee once reported on another Rembrandt painting related to the topic of the current contemplation session. He was repeatedly fascinated by Rembrandt's talent for explaining the story of the prodigal son with suitable details in a compact form. The father figure depicted had impressed him greatly and strengthened his relationship with God.

• Interview B (The Mourner, 869 words, 2 pages, 93 lines) took place in a quiet and relaxed atmosphere but was characterised by many pauses and phases of silence between the individual short statements by the interviewee, who spoke very softly. However, the interview conversation was kept flowing thanks to targeted additional questions, and the concrete circumstances of the interviewee were discussed. She expressed that she was very impressed by the story and the painting, especially the situation of the return appealed to her, because the son's search for his home was so clearly highlighted. That hit her, because she was still in the mourning phase after the death of her husband and was also seeking a new home at that stage.

• Interview C (The Artist, 794 words, 2 pages, 89 lines) was the shortest interview overall and took place in a relatively tense atmosphere, although the interview team went out to relax the person as much as possible with an informal conversation, the offer of a soft drink, and a comfortable seat. The interviewee later wrote in a letter that she was slightly overwhelmed with the somewhat sterile situation, the signature for consent, and the microphone, as she expected more of a pastoral context. In terms of content, however, she expressed herself rather positively about the experience of looking at the painting, the mercy of the father depicted and the thoughts she experienced that introduced her to the hidden details of the Rembrandt painting. She wanted to continue meditating on these details for herself and to work out further formulations for her life.

• Interview D (The Seeker, 817 words, 2 pages, 89 lines) began relatively calmly and relaxed, but turned out to be very personal and emotional. When the interview came to the subject of the life situation with the death of her sister, the interviewee urgently asked for confirmation that the conversation would be treated anonymously and confidentially before she made the very personal statement that, after the death of her sister, she had attempted suicide twice in the past year. She was very moved and tense, and expressed her constant doubts about God's willingness to forgive and whether God would accept her again, as depicted in the story and the painting.

• Interview E (The Lonely One, 1,713 words, 4 pages, 156 lines) was overall relaxed and calm; it took long and was the longest version in the transcript with many biographical passages, some emotional parts, few religious references, and many reflections. A core issue of the life situation and family constellation came to light, which, twice in the interview, led to emotional expression in the form of crying. The interviewee reported on her loneliness after the death of her husband, her isolation, and the deep pain of being rejected by her daughter and two grandchildren. She repeatedly reflected critically on her own behaviour and part in the situation. She was very moved by the painting and hoped - encouraged by the story - that her family relationships would be clarified soon.

• Interview F (The Thoughtful One, 1,048 words, 3 pages, 110 lines) was characterised by a very calm atmosphere, in which the interviewee looked thoughtfully at the painting behind the interviewer and formulated analytical details and reconstructed them from the painting. There was only a short phase with mentioning of emotions. In addition to the long passages of analysis, there were a few biographical inserts and short religious passages. Recurring in every answer were inserts of self-reflection. The interviewee had much sympathy and understanding for the older son and felt - from his own experience - that the older son was treated unfairly.

• Interview G (The Prodigal Daughter, 1,151 words, 4 pages, 150 lines) was slightly tense, but friendly, and the interviewee told a great deal about her experiences and memories and gave insights into her emotional world. Overall, the interview was fairly long, and the atmosphere relaxed towards the end. The topics covered were the family constellations of her own parental home and the current family, a break in life, and the relationship between the very religious interviewee and her heavenly Father. This transcript contained the most sequences, namely 38, which could be encoded in all five categories.

• Interview H (The Cool One, 877 words, 2 pages, 92 lines) was relatively short and in a friendly atmosphere. The interviewee gave specific, short, and well-considered answers, sometimes in a rather deftly way of expression, often referred to the painting, and only briefly gave a hint about his emotional experience twice. Gratitude to the forgiving father was expressed as the main emotion and theme of the painting. The transcript was divided into 24 sequences. The first version of the coding showed many parts of analysis and self-reflection and fewer emotions, religious references, or biographical parts. However, the main religious theme of "guilt" and "forgiveness" was clearly expressed.

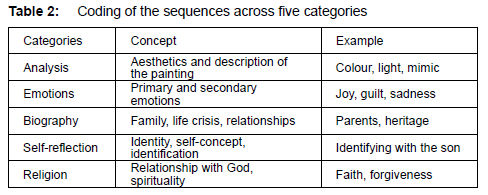

The coding of the interview transcripts (A-H) was done pragmatically in five colours to simplify the analysis and to identify specific patterns. By visualising the five categories of image detail, biography, self-reflection, religion, and emotion (Kuckartz 2018:117-121), core categories and one main category could be ascertained in all transcripts. In addition, types of reactions and a main topic of content were identified. The individual transcription steps were implemented according to the suggestions for transcription and text coding of audio recordings by Flick (2012:379-383). The categories are shown in Table 2 as an overview. The problem of the subjectivity of the categorisation by the main researcher was countered with a control by a second evaluator from the group of interviewers, thus a calculation of the reliability. A total of 243 sequences were assigned across all interviews. Of these, 81 were coded red, 51 black, 49 blue, 32 orange, and 30 green. Three sequences had a discrepancy between the two evaluators. The interrater reliability, calculated using weighted kappa, was considered to be extremely good with k = 0.98 (Landis & Koch 1977:159-174), so that a correction of the affected sequences was not necessary.

The comparative analysis of the eight transcripts (A-H) was carried out visually for similarities and differences, using the colour-coded, compressed versions of the interview transcripts. There were differences in both the main content-related themes and categories and the respective individual patterns that were already described in the individual analysis. However, there were also similarities regarding the religious theme and the regular change of categories that we saw in all transcripts. This was revealed most clearly in a direct comparison of the compressed interviews when we condensed each of them onto a single page for better presentation.

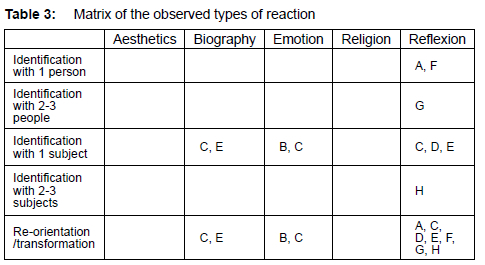

Using the statistical distribution of the categories on a matrix (Table 3), in addition to the core categories of biography and emotion, the main category of self-reflection was ascertained in the qualitative content analysis. All interviews included content-related sequences with a mental tendency towards reorientation, which overlapped with self-reflective thoughts. On the matrix shown in Table 3, the unambiguous result was a content-related weighting of the collected 56 analysis units in the direction of self-reflection and reorientation. In addition to reorientation, two main types of content emerged regarding the reaction to contemplation on the painting. These were the reaction type of identification with a person in the painting and the reaction type of identification with a theme of the painting. Identification with several people or themes of Rembrandt's painting could be regarded as their subtypes.

In the distribution on the selected matrix form with reference to the categories, the main reaction appeared to be reflective thoughts and a tendency towards reorientation (7 people), followed by reacting with reflective thoughts in identification with a single theme (3 people).

The main religious themes were "guilt" and "forgiveness", as well as "mercy" and "new beginning", which corresponded, as we had expected, with the subject of Rembrandt's The return of the prodigal son. Considering the rather unambiguous results, it must be noted critically that the questions in the structured interviews were already focused on the inductively ascertained categories. With this in mind, it seems that the formulation of the interview questions was already tailored to certain emotions, cognition, and self-reflection and was able to initiate the expected main categories in a certain way. This is not unusual in interviews with guideline questions or structured psychotherapy sessions. Subjectivity in the content analysis, done by the main researcher, was countered by a second "evaluator" from the group of interviewers checking the coding. In the qualitative content analysis of the guideline interviews, there was also an intermediate step of comparing the results of the interviews with the thoughts and emotions reported in the feedback questionnaires, which were evaluated anonymously and independently of the interview transcripts. In the intermediate step of comparison, we could demonstrate that the spontaneous, initial emotions and thoughts were later confirmed in the interview transcripts. Another critical point is that, although there was an indication of a reorientation or a change of perspective in all the interviews, this was mostly detected in a single sequence or a single sentence in the analysis units of the transcripts. This can still be regarded as a clear indication of self-reflexivity, leading to possible reorientation and new perspectives.

5. DISCUSSION WITH REFERENCE TO RELEVANT LITERATURE

In the field of pastoral care, it is accepted that dreams and images have the ability to reveal hidden layers in the minds of people and that they can enable a realistic self-assessment helping to promote the process of mental healing (Möller 1994:241). This implies that imagination techniques can help those seeking advice to identify and evaluate systemic constellations. They can be helpful in the treatment of clients with relationship crises, to perceive themselves and other persons differently. Weik (2018:66-76) refers to "suggestive power", which means that, in the area of conflict counselling, one could work with real and fantasised stories to use their suggestive power. The results of the present research work show that the presentation of the story of the prodigal son in connection with the Rembrandt painting made many of the participants perceive relationship crises in their own lives in critical self-reflection, helped to address them openly, and even suggested approaches to conflict and problem resolution. This seems to correspond with the idea of suggestive power that the participants could experience therapeutically through the intervention of viewing the painting. The therapeutic possibilities of contemplation on paintings can be viewed as comparable to the interventions of working with metaphors, dreams, and childhood memories, which are commonly used in individual psychology, as the contemplation on these paintings is also about relationship patterns, behaviour patterns, and attitudes (Otte 2018:106-107). In the explorative contemplation session of the Rembrandt painting, the metaphor of the father and the two sons could be interpreted as a family constellation. In the interviews, family constellations were indeed mentioned. As it was clear that none of the participants lacked a religious reference, the metaphor of the father and the two sons could also be interpreted as religious-ecclesiastical in the sense of God the Father and the children of God.

Metaphors are used in psychoanalysis, behavioural therapy, and schema therapy as tools for imparting insights (Schmitt & Heidenreich 2020:114-121). They represent a universal means of communication. Elementary human experiences such as "light and dark", "father and son", "above and below", "near and far", as well as "rich" and "poor" appear in the chosen Rembrandt painting as aesthetic details that both reveal and strengthen the history and imagination of the recipients. They are cross-cultural and cross-time metaphors for human life and thus easily accessible to a metaphor-reflexive approach (Schmitt & Heidenreich 2020:115). Metaphors and images can convey deeper insights and reflections in their expressiveness than linguistic forms of expression can achieve on their own (Niehls & Thömmes 2020:14). Dodge-Peters Daiss (2016:75-76) expresses her surprise at how often patients use metaphors to articulate the experience of illness and difficult life situations and argues that it shows the potential of works of art in hospital chaplaincy.

In clinical pastoral care, art and images with a religious theme seem to be helpful, because complex processes in one's own life can be captured and understood in images, actions, and symbols of another person or thing. It could enable people to gain a new view of themselves, the environment, as well as forming a better systemic perspective. The described approach creates favourable conditions for therapeutic work on lifestyle. This is according to individual psychology, where one assumes that problematic life situations, crises, and conflicts are not only certain constellations, but also processes that are related to the individual construction of reality, one's own thought patterns and biography, and that are, therefore, amenable to reorientation and a change of perspective. These experiences, which can be purposely modulated by certain interventions, were demonstrated among the participants in the interviews when analysing the transcripts. One interviewee expressed the hope that reconciliation with her daughter could become real because the father made this happen in the presented painting and the related story. Another interviewee found consolation in the fact that the father no longer resented his son's way of life, and she could transfer this situation to her sense of guilt towards God. Another participant was concerned about his own identification with the older brother and drew some first mental conclusions from this insight. Without exception, all interviewees in this empirical study identified themselves with one specific theme or person from the Rembrandt painting. Inspired by the feedback questions, they had, in the days after contemplating on the painting, constructively dealt with the painting and its content, as well as with the related story of the prodigal son. They had all experienced the process of intellectual and emotional transfer from the painting to their own biography and lifestyle during the intervention.

The method of individual psychology, as presented by Alfred Adler (Ansbacher & Ansbacher 2004:142-166), makes the symptoms of a problem understandable for the persons concerned in their lifestyle development, since these symptoms are accepted as an expression of their own lifestyle. Identifying feelings, beliefs, and certain behaviours can contribute to being no longer overwhelmed, embarrassed, or rejected. The aim of working on the lifestyle could contribute to liberating self-knowledge, which, with helpful self-reflection, can expand the narrow reality construction of a person's limited perspective on a specific life situation, so that beneficial attitudes towards life and social integration are gained. This also applies to attitudes that are difficult to grasp and explain when using language only (Otte 2018:104). Cilliers (2012:18-22) refers to the research of Bandler and Grinder (1979), who described reframing as a method to create an alternative form of behaviour and mentions that reframing could be accomplished by works of art. In pastoral care, reframing can be experienced by the encounter of the other, in the form of an image, a metaphor, or a dream. Palmer (2004:92-93, in Dodge-Peters Daiss 2016) describes this as third things - metaphors, poems, stories, a piece of music, or works of art - that represent neither the voice of the facilitator nor the voice of the participant, but that have voices of their own with which intense issues can be addressed. Spitzbart (2020:104-106) refers to "iconic pastoral care", where biblical images or icons are used both as allegories and as helpful interruptions in the pastoral counselling process, creating an opportunity to "let the images work" and opening up "spaces of thought for prudence". As the perception of spaces, images, and closeness, as well as distance can be decisive for pastoral care through iconic images, an empathetic approach to the client should be an essential part of the therapeutic relationship in clinical pastoral care.

Apart from conversations, prayers, and rituals, media such as music and images are forms of religious representation that have proven themselves in pastoral care (Wagner-Rau 2017:177). The numerous personal responses to the feedback forms and, at times, sobering candid revelations in the interviews, bear witness to this. Contemplating on paintings could be a bridge to narrative language in pastoral conversations and discussions. It could also be used in the broader pastoral sense, such as in pastoral sermons, devotions, and discussion groups, where a painting can initiate a conversation between image and viewers. Images and paintings can also have functions in the narrower sense of the phrase "pastoral care", namely in the protected environment of personal conversation.

Regarding the dimensions of pastoral care, the practical theologian Eschmann (2016:149-151) distinguishes the theological dimension of pastoral discussions from the individual life situation of the person seeking advice and the personal-communicative dimension. The latter dimension can be enriched by referring to a religious image or painting, by promoting the verbalisation of emotions and thoughts. The study also shows that the specific life situation of the individual participants was found easily in the transcripts and contributed to the individual assignment of a pseudonym with which the respective persons could clearly identify in their individual and sometimes problematic life situations. In identifying with a person or theme of the Rembrandt painting of the prodigal son, the life situation seemed to be presented to the individuals as in a mirror and thus gave them a greater understanding of their respective life situations, the necessary use of language, and the possibility of open conversation in the protected space of the interview.

Guilt and forgiveness are not only core issues in theology, but have also become the subject of discussion in psychological research (Worthington & Scherer 2004:385-405). The promise of forgiveness, as it is practised in the context of a worship service, for example, at the Lord's Supper, contains an existential value for the recipient that should not be underestimated, both mentally and emotionally. This is illustrated by research that examined both physical and mental health in relation to forgiveness (Berry & Worthington 2001:447-455). Although in the story of the prodigal son, as handed down in Luke's Gospel, the subject of guilt and forgiveness is treated in a culturally sensitive manner, it is presented very openly. Rembrandt tried to summarise this visually in his picture of the prodigal son. In this research, both "guilt and forgiveness" and "repentance and mercy" emerged as themes that are experienced. The almost desperate search for forgiveness was evident in two of the interviews. The relief and gratitude for God's forgiveness as well as past and present forgiveness in human interaction were found in further interviews. Gratitude for God's mercy as well as approaches for repentance, conversion, and reorientation were also clearly detected in the interviews and, together, made up the main religious theme of the study. When dealing with guilt and forgiveness in pastoral care, it is advised that the therapeutic constructive approach should always take place from the perspective of forgiveness and lead to salutary self-knowledge and a solution-oriented perspective. In the pastoral context, a moralising approach to the topic should always be avoided (Eschmann 2002:168-169). By using Rembrandt's painting, together with the story of the prodigal son, the participants of the contemplation session were confronted with the issues of guilt, forgiveness, and a new beginning, not in a moralising way, but in a solution-oriented manner. It was shown that it was possible to handle these sensitive topics impartially and openly in almost all interview situations. Open questions, such as willingness to forgive other people, doubts about God's willingness to forgive again and again, or the question of the severity of one's own guilt were revealed in the protected space of almost all the interviews. This testifies to the depth, honesty, and impartiality of all those involved, which must have had its origin in the devout contemplation on a painting with a religious theme.

In his book on image functions, the theologian Reinhard Hoeps (2020:1416) speaks of the lost functions of religious images in modern times and alienation between images and Christianity. The results of the present study in a rehabilitation hospital show possibilities for clinical pastoral care to revive the functions of images with a religious theme, even if these functions may seem to have been lost. In an article on religion and feeling, the practical theologian Jörg Herrmann (2013:208-209) describes the combination of audio-visual sensitivity and narrative structured meaning on four levels. These are the perceptual level with spontaneous sensations, the level of the depicted world, which can trigger situation-related emotions, the third level with the development of topics, and the last level of reflection on the aesthetic or moral experience of reception. In clinical pastoral care, special impulses for communication can thus emanate from visual media and images. As stated earlier, the practical theologian Jan Grevel (2007:290-291) believes that images are an important bridge for narrative language in pastoral discussions and, in some contexts, an interface between biographical meaning and the experience of the sacred in one's life.

6. CONCLUSION

Strictly following the steps of a qualitative analysis of visual materials, as described in the literature, had a positive effect on the cognitive learning possibilities and the emotional reactions of participants in a session contemplating on a painting with a biblical theme. These effects and reactions were systematically classified according to main topics or themes and reaction types. Essentially, two types of reaction to the painting presented were ascertained, which, in terms of aesthetic reception, are related to the theme and the main characters shown. Individually, the explored, creative experience processes showed different contents, but were concentrated on the main theme of the painting and could be demonstrated in all eight interviews without exception. All participants were Christians of various denominations, who, according to their own statements, had benefited personally from the intervention. In the guided interviews, a desire was expressed for further pastoral discussions and a further examination of the subject matter of the painting.

In all interviews, self-reflexivity and approaches to reorientation were found in varying degrees. These were overlapping and often only partially recognisable in a sentence or a marginal note. However, these findings explain the depth of the experience processes achieved in the interview with themes that are experienced as being existentially important for personal life. Based on the findings, this self-reflexivity is helpful and can be used for the intervention of contemplation on a painting with a religious theme in the current context. Following the results of the study, paintings with a religious theme and meditative contemplation on their contents are viewed as valuable instruments in clinical pastoral care if they are conceptually integrated into the organisational processes of pastoral support and advice as well as in subsequent discussions.

Scientific questions that arise from the exploratory study are primarily the aspects of the extent to which the findings apply to the specifically selected Rembrandt painting only and whether similar aesthetic reactions of reception would be recorded with other paintings and a different analytic approach. Furthermore, the question arises as to whether another sociocultural context outside of clinical pastoral care, for example, a church parish or a Christian educational institution, could have a modifying influence on the results of the outcome of the research. Therefore, a practical proposal is made for a further, comparative study that uses the results of this study, but that goes beyond the exploratory approach and compares the results with findings in a different sociocultural context also using other paintings with a biblical or religious theme.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The present research was carried out by the main author, F.B. Herm, as part of a Master of Theology dissertation at the University of South Africa. The two co-authors, Prof. V. Kessler and Prof. E. Kloppers, supported both the research proposal and the master's thesis from 2019 to 2021 as supervisors, with their comments, constructive suggestions, discussions, and references.

The psychotherapist, Dr K. Herm, and the clinical counsellor, Ms A. Albrecht, provided professional support in conducting the structured interviews. They reacted empathically and professionally to the participants in the interviews and provided the corresponding critical feedback to the author in the evaluation process.

The authors would like to express their thanks to the management board of the Altmühlseeklinik Hensoltshöhe, for the kind permission to carry out the explorative study in the rehabilitation hospital. The main author would also like to thank the pastoral care team of the Altmühlseeklinik Hensoltshöhe, for the appreciative support in the data collection and evaluation, in accordance with the guidelines of the Unisa Ethics Committee.

COMPETING INTERESTS OR FUNDING

The author declares that there is no personal or financial relationship or dependency that might have inappropriately influenced the outcome of the study or the conclusions. The presented research received no specific grant or funding from any public or commercial agency.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The presented exploratory research followed all ethical standards of the German Society for Sociology and received the approval of the Research Ethics Review Committee of the College of Human Sciences at the University of South Africa in January 2021. It was envisaged that participation was voluntary, and anonymity of the data collected was guaranteed to meet the requirements of the ethical code of the German Society for Sociology and the Professional Association of German Sociologists (Ethik-Kodex 2017) and the German Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz 2018).

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing other than the already presented data in the article is not applicable for this research, as the data collection, informed consent, and storage of the digital data must be handled in accordance with the German Federal Data Protection Act.

DISCLAIMER

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the three authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the involved hospital or university.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ansbahoer, H. & Ansbahoer, R. 2004. Alfred Adlers Individualpsychologie. Eine systematische Darstellung seiner Lehre in Auszügen aus seinen Schriften. 5. Aufl. München: Reinhardt. [ Links ]

Bandler, R. & Grindler, J. 1979. Frogs into princes - Neuro linguistic programming. Moab, UT: Real People Press. [ Links ]

Berry, J. & Worthington, E. 2001. Forgiveness, relationship quality, stress while imagining relationship events, and physical and mental health. Journal of Counseling Psychology 48:447-455. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48A447 [ Links ]

Breokner, R. 2012. Bildwahrnehmung - Bildinterpretation. Segmentanalyse als methodischer Zugang zur Erschlieβung bildlichen Sinns. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 37:143-164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-012-0026-6 [ Links ]

Bundesdatenschutzgesetz (BDSG) 2018. Bundesdatenschutzgesetz. [Online.] Retrieved from: www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bdsg_2018/BDSG.pdf [5 November 2022]. [ Links ]

Burrichter, R. & Gartner, C. 2014. Mit Bildern lernen. Eine Bilddidaktik für den Religionsunterricht. München: Kösel. [ Links ]

Cilliers, J. 2012. Fides quaerens imaginem: The quest for liturgical reframing. Scriptura 109(2012):16-27. https://doi.org/10.7833/109-0-121 [ Links ]

De Gruchy, J.W. 2008. Christianity, art and transformation. Theological aesthetics in the struggle for justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Dodge-Peters Daiss, S. 2016. Art at the bedside: Reflections on use of visual imaginary in hospital chaplaincy. Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling 70(1):70-79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1542305015618170 [ Links ]

Eschmann, H. 2016. Christliche Seelsorge. Spiritual Care 5(2):149-151. https://doi.org/10.1515/spircare-2016-0037 [ Links ]

Eschmann, H. 2002. Theologie der Seelsorge. Grundlagen - Konkretionen- Perspektiven. 2. Aufl. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener. [ Links ]

Ethik-Kodex 2017. Ethik Kodex der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Soziologie (DGS) und des Berufsverbandes der Deutschen Soziologinnen und Soziologen (BDS). [Online.] Retrieved from: https://soziologie.de/fileadmin/user_upload/dokumente/Ethik-Kodex_2017-06-10.pdf [4 November 2022]. [ Links ]

Flick, U. 2012. Qualitative Sozialforschung - Eine Einführung. 5. Aufl. Reinbek: Rowohlt. [ Links ]

Fritsch, G.R. 2012. Der Gefühls- und Bedürfnisnavigator. Gefühle undBedürfnisse wahrnehmen. Paderborn: Junfermann. [ Links ]

Grab, W. 2006. Religion als Deutung des Lebens. Perspektiven einer Praktischen Theologie gelebter Religion. München: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. [ Links ]

Grevel, J.P. 2007. Qualitative Bildanalyse. In: A. Dinter, H.G. Heimbrock & K. Söderblom (Hg.), Einführung in die Empirische Theologie: Gelebte Religion erforschen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), pp. 279-291. [ Links ]

Haussmann, A. 2021. Die Kraft der Bilder. Visuelle Kommunikation in sozialen Medien und ihre Potenziale für Spiritual Care und Seelsorge. Spiritual Care 10:198-207. https://doi.org/10.1515/spircare-2021-0037 [ Links ]

Heimbrock, H.-G. & Meyer, P. 2007. Praktische Theologie als Empirische Theologie. In: A. Dinter, H.-G. Heimbrock & K. Söderblom (Hg.), Einführung in die Empirische Theologie: Gelebte Religion erforschen (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), pp. 17-26. [ Links ]

Herm, F.B. 2021. Bildbetrachtungen im Kontext der Pastoraltherapie: eine explorative untersuchung in einer Rehabilitationsklinik in Bayern. Unpublished Master's dissertation. Pretoria: Univeristy of South Africa. [ Links ]

Herrmann, J. 2013. Zuflucht der Seele. Über Kino, Gefühl und Religion. In: L. Charbonnier, M. Mader & B. Weyel (Hg.), Religion und Gefühl (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), pp. 203-216. https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666624285.203 [ Links ]

Hoeps, R. 2020. Handbuch der Bildtheologie. Bd. 2. Funktionen des Bildes im Christentum. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. [ Links ]

Kukhartz, U. 2018. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. 4. Aufl. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa. [ Links ]

Landis, J.R. & Koch, G.G. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310 [ Links ]

Möller, C. 1994. Gregor der Groge. In: C. Möller (Hg.), Geschichte der Seelsorge in Einzelportrãts. Bd. 1 (Göttingen, Zürich: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), pp. 223-243. [ Links ]

Niehls, F.W. & Thömmes, A. 2020. 212 Methoden für den Religionsunterricht. Neuausgabe. 3. Aufl. München: Kösel. [ Links ]

Noll, T. 2004. Zu Begriff, Gestalt und Funktion des Andachtsbildes im spaten Mittelalter. Zeitschrift fürKunstgeschichte 67:297-328. https://doi.org/10.2307/20474254 [ Links ]

Nouwen, H. 2016. Nimm sein Bild in dein Herz - Geistliche Deutung eines Gemãldes von Rembrandt. Neuaufl. Freiburg: Herder. [ Links ]

Otte, M. 2018. Systemische Interventionen im Kontext der individualpsychologischen Lebensstilerarbeitung. In: M. Kessler, W. Schafer & M. Utsch (Hg), Menschen begleiten: Individuell - ganzheitlich - geistlich (Berlin: LIT), pp. 103-118. [ Links ]

Palmer, P.J. 2004. A hidden wholeness: The journey toward an undivided life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Pohl-Patalong, U. 2007. Seelsorge. In: W. Grab & B. Weyel (Hg.), Handbuch Praktische Theologie (Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus), pp. 675-686. [ Links ]

Rose, G. 2016. Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. 4th edition. London: Sage. [ Links ]

Sohmitt, R. & Heidenreioh, T. 2020. Metaphern-reflexives Vorgehen in der Psychotherapie. Psychotherapeuten Journal 2020(2), pp. 114-121. [ Links ]

Spitzbart, D. 2020. Ikonische Seelsorge. Bildern begegnen - Raume öffnen. 1. Aufl. Zurich: TVZ. [ Links ]

Steinmeier, A.M. 2020. "Sehenszeit". Zur Bedeutung des Imaginaren am Ort der Seelsorge. In: T. Erne & M. Krüger (Hg.), Bild und Text: Beitrage zum 1. Evangelischen Bildertag Marburg 2018 (Leipzig: Ev. Verlagsanstalt), pp. 379-403. [ Links ]

Wagner-Raü, U. 2017. Seelsorge. In: K. Fechtner, J. Hermelink, M. Kumlehn & U. Wagner-Rau (Hg.), Praktische Theologie. Ein Lehrbuch. 1. Aufl (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer), pp. 171-192. [ Links ]

Weik, G. 2018. Menschsein heilit in Beziehung sein. In: M. Kessler, W. Schafer & M. Utsch (Hg.), Menschen begleiten: individuell - ganzheitlich - geistlich (Berlin: LIT), pp. 63-78. [ Links ]

Worthington, E.L. & Soherer, M. 2004. Forgiveness is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can reduce health risks and promote health resilience: Theory, review, and hypotheses. Psychology and Health 19:pp. 385-405. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044042000196674 [ Links ]

Date received: 22 March 2022

Date accepted: 31 October 2022

Date published: 14 December 2022

1 Based on the Master's dissertation: Bildbetrachtungen im Kontext der Pastoraltherapie: eine explorative untersuchung in einer Rehabilitationsklinik in Bayern (Herm 2021).