Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.42 supl.33 Bloemfontein 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup33.11

ARTICLES

Peace in the spirituality of Thomas á Kempis. An aesthetic perspective on the Imitatio Christi 4.25

P.G.R. de Villiers

Prof. Pieter G.R. de Villiers, Professor Extraordinaire, Department of Old and New Testament Studies, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. E-mail: pgdevilliers@mweb.co.za, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7047-299X

ABSTRACT

The Imitatio Christi of Thomas á Kempis reflects the transformative contribution of the Devotio Moderna as a reform movement from the 14th to the 16th century to the religious discourse up to modern times. This contribution focuses on the theme of peace in the Imitatio Christi 4.25 as a key to Thomas' spirituality and the Devotio Moderna. The first section of this article scrutinises the unique aesthetical nature of the text in terms of its spiritual impact and its contribution to an adequate understanding of the chapter. The article then analyses the two main aspects of peace that emanate from an aesthetic analysis of the chapter, namely its divine nature as spiritual gift. A second section analyses the interiorising of peace as the human response to the divine gift and, finally, examines the mystical quality of the chapter in its discussion about the heart of peace as resting in God.

Keywords: Thomas á Kempis, Devotio Moderna, Spirituality, Mysticism, Peace

Trefwoorde: Thomas á Kempis, Devotio Moderna, Spiritualiteit, Mistisisme, Vrede

1. INTRODUCTION

The Imitatio Christi 4.25 addresses a key theme in the mystical1 book on Inner Consolation that concludes the Imitatio Christi of Thomas á Kempis, one of the best-known spiritual classics in the history of Christianity.2 Its heading reads, In quibus3firma pax cordis et verus profectus consistit (What consists of firm peace of the heart and true progress). Peace is linked in the heading with the notion of progress. Both are, in turn, qualified by "firm peace from the heart" and "true" progress. The notion of progress is again noted in verse 12, which refers to the "way of peace" (via pacis) that one walks (ambulas). Peace thus involves a journey towards an authentic form of peace that involves finding what should and what should not be sought in the quest for spiritual growth.

The chapter begins with the introduction of peace as a divine gift (section 1). This is followed by an explanation of what this peace is and is not (sections 2 and 3). In section 1, Christ speaks of his unique peace as a gift, quoting John 14:7. In response, the disciple asks what peace comprises, whereupon Christ tells him, in section 2, not to focus on anything but Christ alone, not to interfere in others' business, and to accept suffering as part of the earthly spiritual journey. The disciple then again asks Christ what are the things that give peace, whereupon Christ asks him to subject himself to the divine will, to remain equanimous, to seek self-negation, and to remain hopeful and joyful in adversity and prosperity.

The aesthetic density of Chapter 4.25 is already evident from its heading that functions to prepare the reader for, and to order the contents of the Imitatio. Thomas listed the headings of all chapters at the beginning of the Imitatio, when he made the authorised texts available for further dissemination in 1441.4 He also inserted the chapter heading in red ink as rubric before the chapter itself in his own hand.5 Thomas, therefore, recorded the same heading twice himself, at different moments in time. This happens also in 4.25. The heading signals that the chapter is about "the things of which (in quibus) peace and progress consist". This phrase is placed in the sentence initial position, emphasising that peace has various dimensions. Peace is then also foregrounded right from the beginning of the chapter, where the Lord's vocative address of the Son (fili) in verse 1 mentions and assumes peace three times.

Chapter 4.25 is not an isolated discussion about peace. The motif appears repeatedly elsewhere in the book. On the highest level, the theme of peace is determined and informed by the mystical, intimate nature of the book of consolation, in which it is integrated.6 This mystical nature in this fourth book of the Imitatio is illuminated by other spiritual themes such as love (Ch. 5), holiness, obedience, patience, humility, and trust that are part of humanity's spiritual transformation and progress towards the spiritual notion of perfection. All of them reveal the special contents of the book that develop the inner consolation that the encounter with the divine gives and that forms the theme of the Imitatio's final section (Van Dijk 2008:13). Peace contributes significantly to the consolation of the spiritual pilgrim.

Peace is an important motif among these themes.7 Chapter 4.25 also fits in well within the immediate context of 4.25. Peace is, for example, mentioned in 4.23, which discusses four aspects that bring much peace, namely

Strive to do the will of others rather than your own, choose to have less rather than more, search for the lowest place/part, desire to have the divine will be done in you (23.3-4).

Renouncing one's own will, simplicity, humility, and doing the divine will are thus highlighted and are prominent in the mind of readers when they start reading Chapter 25. These four aspects reappear in some way or other again in Chapter 25. They all complement and develop the contents and meaning of the spiritual progress that is mentioned in the heading and provide valuable insights into the meaning of peace.

This contribution begins with an analysis of the unique aesthetic nature of the text. It is scrutinised in terms of its contribution to an adequate understanding of the chapter, but also because of its spiritual impact that reveals the underlying spiritual dynamics of the chapter. It then analyses the two main aspects of peace that emanate from an aesthetic analysis of the chapter, namely its divine nature as spiritual gift and, in a second section, the interiorising of peace as the human response to the divine gift. The contribution concludes with an analysis of the mystical quality of the chapter in its discussion about the heart of peace as resting in God and spells out its relevance for the book as a whole.

2. AN AESTHETIC CHAPTER8

Chapter 25 has, like the remainder of the Imitatio, a striking aesthetic character, confirming its poetic, lyrical and rhythmic nature.9 This aesthetic nature of the text is, for example, clear from the neat pattern in the contents of Chapter 4.25. The chapter is organised in three main sections, as the formal indicators clearly show. The three sections (1-5; 7-9; 11-13) are separated by two short questions: "What must I do?" (verse 6) and "In what then Lord?" (verse 10).10 The contents are structured in such a way as to enhance the flow of the text, optimise the understanding of the text, and help the reader experience it fully. At the end of this contribution, a close reading of the text is inserted to illustrate visually the organising of the contents in units and the various aesthetic qualities. The following discussion often refers to this close reading.

Not only its contents have a beautiful pattern, but literary markers and techniques further organise the form of the text and establish it as an attractive work. Such an insight and competence of an author in the intricate shaping of a text never fail to impress. They indicate the constitutive elements of the text, the emphases in its pronouncements, and the flow of the argument. Thomas carefully considered the formal aspect of his composition,11 paying attention to literary techniques such as ring composition that links phrases and sections, and other devices such as homoioteleuton, homoiooptoton, parallelism,12 focalisation, alliteration, rhyme, and assonance.13 It is an impressive array of aids that are employed to express the content in an attractive form. These formal aspects are also helpful in promoting an optimal communication of the text with its audience.

Such literary features also serve the spiritual effect of the text. This happens, for example, through the technique of characterisation. The contents of Chapter 4, with its pattern of three sections separated by two brief responses of the son, characterise him as a receptive listener who responds positively to the Lord as protagonist and initiator of the dialogue. The disciple is a rather flat character, but the narrative unfolds and progresses through him. In addition, the character of the son refines or illuminates the meaning of the chapter's contents. They prefigure and announce what follows, reflecting the notion of progress (verus profectus) that was announced in the heading. The Lord is guiding the son in the process of seeking spiritual growth. This aspect subtly indicates the desire of the son to journey on the spiritual way and to find more spiritual maturity.

These literary techniques also help confirm and explain the function of the text to express the theme of progress in peace optimally. The order and pattern in which the text has been composed assist the reader in experiencing its intended impact. Thomas composed the text with the function that it had to be read orally within a meditative or liturgical context within a communal setting, primarily for his monastic community in their spiritual exercises. He is explicit with prescriptions to the reader for this oral presentation of his work that would effectuate this function.14 This performative function of the text is to provide spiritual support to its audience in their quest for a fulfilling and uplifting human existence. This function is supported by the explicit references in the text that underline the interiorising of the contents, such as the need for the disciple to act "from the heart" (for example, verse 11).15The techniques thus reveal that the Imitatio functions as a mystagogical aid that would inspire readers to a contemplative life coram Deo.

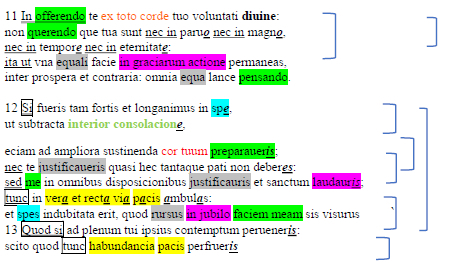

One example from the close reading illustrates the density of aesthetic elements in the chapter.16 Its first section (1-5), which comprises an appeal by the Lord to the disciple to pursue true peace, for example, has an ABBA pattern, created through strict rhythm and intensified by foregrounding phrases and word endings. For example, vobis in the sentence final position of phrases in verse 1 groups the first three phrases together (marked in italics). The omnes desiderant / omnes curant in the sentence final position in verse 2 creates a unit (B; marked with double underlining). The pax mea / tua in the sentence initial position in verse 3 forms a second unit (B'; marked in bold), and the audieris / fueris pattern binds verse 5 (A'; marked with a block). All five verses mention the word "peace" explicitly, highlighting its significance as the theme of this chapter. The word is repeated seven times in key places. A visual representation of the first five verses illustrates this pattern:

1 Fili. Ego locutus sum pacem relinquo vobis A

pacem meam do vobis:

non quomodo mundus dat ego do vobis.

2 Pacem omnes desiderant: B sed quae ad veram pacem pertinent non omnes curant.

3 Pax mea cum humilibus et mansuetis corde. B'

4 Pax tua erit in multa patientia.

5 Si me I audieris A'

et vocem meam secutus fueris: poteris multa pace frui.

The remainder of the chapter also reflects such an organised, neat pattern.17

Finally, and on the deepest level of interpretation, an investigation into the aesthetic quality that is evident in its form, contents, and function, ultimately uncovers the beauty of the text, and, in tandem with it, also of the spiritual journey. My previous investigation into the seemingly mundane book 1.17 of the Imitatio, with the heading De monastica vita, which discusses the simple realities of the ideal monastic life, indicated how, on a deeper level, the dense aesthetic quality of the chapter celebrates the beauty of the monastic life with its dense aesthetic quality.18As will become clear later in this contribution, a close reading of Chapter 4.25 reveals the same aesthetic quality with similar contents, function, and form. They illuminate the beauty of the spiritual quest for peace in a comprehensive manner. In both instances, the chapters speak about a lived experience that ennobles, empowers, and transforms the reader from a superficial lifestyle to a fulfilled existence as the purest form of beauty, as the following analysis shows. There is nothing pretentious or superficial about the aesthetic quality of the text. Thomas' composition is beautiful, because it opposes sophistry and speculative contents. He writes in Chapter 5:1: "Truth is to be sought in the Holy Scriptures, not skill in words", and in 5:3-4: "We must seek rather usefulness in the Scriptures than subtlety of speech" (see also Kubsch 2018:17-18). Empty pretentiousness and verbose speech would be counterproductive to a transformative relationship with God, because it would stand in the way of a meditative life that seeks to be in the presence of God and that is not self-centred.19 In fact, the chapter is so beautiful exactly because of its sober, but ornate and effective language.

3. A DIVINE PEACE

The aesthetical reading of the chapter unmistakably shows how Thomas stresses the divine nature of peace. Peace finds its origins neither in humanity nor in an institution. It comes to people from God as its only source. Thomas begins the first unit in verses 1-5 with an address by the Lord that comprises a direct quotation of Scripture - a technique he uses elsewhere to mark important sections.20 The quotation begins in verse 1 with "I have said" (locutus sum), emphasising that it is about words of the Lord. The last unit (A' in verse 5) ends with the condition: if you listen and follow my voice. The first unit (A) thus coheres with the last unit (A') in section 1 (1-5), creating a ring composition and thus underlining Christ as the benefactor of peace.21 There is, however, also progression in verses 1-5 in the portrayal of peace. Verse 5 notes that those who heed the Lord's voice will enjoy (fueris) "great" peace (multa pace). Jesus is the one who actively and committedly gives peace, as is emphasised repeatedly by the expressions "I bequest", "I give peace", and "my peace" that delineate the Lord as source and active giver of peace in verses 1-5.22 All this underlines the divine authority that determines the contents of the chapter on peace and the special nature of peace as a divine gift.

A ring composition creates even greater coherence in the chapter as a whole (verses 1-13). Verses 12 and 13 end the chapter with the motif of peace, by referring to abundant (habundancia) peace for those who come to complete self-negation. Those who walk in the way of true peace (verse 12) will see "my face" (verse 12). The spiritual journey begins and ends with the divine.

The conclusion of the chapter thus intensifies the focus on the divine nature of the peace mentioned in the first unit. From "listening" and "hearing" the voice of the Lord, there is movement and progress to the ultimate end of actually seeing the face of the Lord. This emphasis on peace as divine and as that which cannot be found in the "world" (verse 1) is also strengthened by the other additions that underline its beauty. It is overflowing, consisting of "much" peace and of "abundant" peace. This peace reflects the transformation in glory that is also typical of spiritual texts: it will ultimately be experienced in the presence of God. So special is this glorious end that it will bring the disciple in ecstasy: the faithful will be in jubilation when they see God's face. The motif of the visio Dei is placed in the conclusion as the climax of the life in peace (verse 12). Even hardships, struggles, and challenges cannot detract from this beauty.

The beauty of all this is expressed also elsewhere in the Imitatio in, for example, the lyrical Chapter 4.22. This passage underlines the desire for a virtuous life that the Lord gives to the faithful who wish to progress in the way of faith. It reflects an awareness of blessings, of the generosity, greatness, the divine goodness, and mercy. It also underlines the divine nature of peace by emphasising the unworthiness of humanity. The passage indicates an ecstatic and mystical experience of the divine presence in the quest for peace:

Open my heart, O Lord, to your law and teach me to walk in the way of your commandments. Let me understand your will. Let me remember your blessings - all of them and each single one of them -with great reverence and care so that henceforth I may return worthy thanks for them. I know that I am unable to give due thanks for even the least of your gifts. I am unworthy of the benefits You have given me, and when I consider your generosity my spirit faints away before its greatness. All that we have of soul and body, whatever we possess interiorly or exteriorly, by nature or by grace, are your gifts and they proclaim your goodness and mercy from which we have received all good things.

4. THE HUMAN POLE: INTERIORISING PEACE23

Although the chapter begins with an emphasis on peace as a divine gift, it also speaks in detail about the human reception of peace. Spirituality is about a transformative relationship of the divine with humanity. If Chapter 4.25 excels in its description of the divine source and gift of peace, it is equally attentive to the role of humanity in this relationship. It is, therefore, not a quietist response of humanity to the divine gift of peace. In this chapter, peace is also about a quest for peace. It is closely linked with renewal of the inner being of a person and with the quest for virtue.

The active role is indicated in one word in Chapter 4.25.9, where the disciple is informed about what characterises the "true lover of virtue" (amator virtutis). The chapter explains virtue in verses 3-4, stating that the Lord's peace is with the humble and meek. The phrase "in their hearts" immediately follows these well-known and traditional phrases of humility and meekness. It states, Pax mea cum humilibus et mansuetis corde. Pax tua erit in multa patientia. Corde is foregrounded by its place in the sentence final position. At the same time, interiority is explained in terms of perseverance and patience (in multa patientia; verses 3 and 12). Interiority and the heart are also highlighted later at the beginning of the last part in verse 11, where the Lord reveals to the disciple that "real" peace is to be found in submission to the divine will from the whole heart (ex toto corde) and in not seeking one's interest.24

The remainder of the Imitatio confirms this focus on interiority. The divine touch affects a person in the innermost of his or her being. It sets in motion a process of transforming the self, the feelings, and thoughts to display virtues (Van Dijk 2011:29). Book 2, for example, introduces the interior life already in its first chapter with a reflection on meditation. It begins with the striking remark that God's kingdom, "which is peace", will come to those who let go of external things. The Lord of peace gives peace to his followers who become peaceful to the core of their being. This passage, therefore, reflects the mutuality that is characteristic of the mystical experience.25 The peace of the Lord enters and transforms people:

Christ will come to you offering his consolation, if you prepare a fit dwelling for him in your heart, whose beauty and glory, wherein he delights, are all from within. His visits with the inward person are frequent, his communion sweet and full of consolation, his peace great and his intimacy wonderful indeed.26

This passage eloquently expresses how the Lord's presence transforms the inner being of a person, clothing it with attractiveness and beauty. It is an example of how the Imitatio reveals a recalibration of the interior life (Van Dijk 2014). Inner peace is thus recognised through the virtuous life of those who follow the Lord and appropriate his will.

The chapter thus illustrates how the encounter with the Lord kindles the desire for and brings peace to his followers.27 The peace is about patience and perseverance, that is, to "create a fit dwelling" for Christ that is characterised by peace. Followers of Christ place themselves in the life and words of Christ to then be transformed in their innermost being into a state of peace. The goal, in this instance, is not merely to imitate the life of Christ in the sense of becoming like him, but to be conscious of the divine, and not promote oneself (Waaijman 2002:187; see also further below). The longing for a virtuous life suggests a certain passivity of the disciple who, in the first instance, receives peace from the Lord, as was spelled out earlier.28 The virtue, of which Thomas speaks, is, therefore, not a collection of properties that one possesses (Huls 2006:73). The disciple is made virtuous by God through surrender to the divine power that moves from within.

Yet, such an "active" passivity reflects a transformed mindset and disposition that is actively involved in responding. Those who receive peace are those who "care" (curant) for it (verse 2), so that it becomes their peace that they own (see tua; verses 3 and 4). What exists in a mindset of humility and kindness in the Lord's ("my") peace must become "your" peace that is pursued by the disciple "in much patience".29

Finally, interiorisation is characterised by three important insights. Verse 9 states that true peace is, first, not found in devotion and sweetness. Ecstatic experiences, religious feelings, should not be equated with peace.30 Secondly, peace is about a complete surrender to the divine will, which means, as verse 11 indicates, the complete and total disregard for oneself. Thirdly, the process of transformation has social ramifications: the relationship with the divine affects that changes the individual in his/ her inner existence, affects also the mutual relationships with others. It means, for example, not judging others rashly or interfering in what they do and say (verse 7).

5. DELIGHTING IN ABUNDANT PEACE: A MYSTICAL TEXT

In Chapter 25, peace is inextricably linked with an awareness and consciousness of the divine presence. This is said in the first unit in verses 1-5. Disciples will "enjoy much peace" if they listen to the Lord and follow his words (verse 5). This intimate face-to-face relationship is again mentioned in verse 7, where the disciple is called to direct all attention on "pleasing" (placeas) "only me" (michi soli) and to desire or seek nothing (nihil) "apart from me" (extra me). Even more intense is the final reference to the issue in verses 11-13. The strong and patient disciple can live in the indubitable hope to see in jubilation the Lord's face.

Other contemplative words in verses 11-13 confirm this mystical motif. There is reference in verse 12 to "inner consolation" that speaks of the consoling presence of the Lord, even though such consolation may be withdrawn at times. How radical this is, becomes clear in light of what Thomas writes about consolation in Book 2.1. This passage has an ecstatic nature and is linked with several positive words, among them the notion of peace, that describe the special nature of consolation.

Christ will come to you offering His consolation, if you prepare a fit dwelling for Him in your heart, whose beauty and glory, wherein He takes delight, are all from within. His visits with the inward man are frequent, His communion sweet and full of consolation, His peace great, and His intimacy wonderful indeed.

Consolation has, therefore, to do with beauty and glory; it is about a beautiful and intimate mystical experience.

Even more radical is that a disciple, who walks in the way of true and right peace (verse 12) and is deprived of consolation, will be able to prepare his heart to sustain even harder things in his spiritual journey and will do so joyfully. He will be able to praise the Lord as just and holy and would not think of blaming him for adversity. Note how the Lord does not speak of praising all "the" or "my" dispositions, but of praising "me" (laudaris me) in all dispositions. This speaks of a face-to-face relationship between the disciple and the Lord. This remark is then combined with a pronouncement that reflects a transformation in glory that is also a recurrent motif in spirituality and an important aspect of the transformative relationship with the Lord. The disciple, who walks the spiritual way, can expect to see the Lord's "face" (faciem) in jubilation (in jubilo) again. It reflects an ecstatic experience for those who encounter the Lord.

All these positive terms about peace confirm its mystical quality: someone who believes with such complete, even ecstatic commitment to the Lord and desires the divine presence is walking in "the true and right way of peace".

Another seemingly obscure detail deserves more attention. The climactic end of the first unit (verses 1-5) informs followers that they will enjoy (frui) much peace if they listen to the Lord and heed his words. An aesthetic analysis reveals how the conclusion in verses 11-13 also culminate in peace, but only then more intensely than previously. Verse 13 concludes the chapter with the remark that the one who comes to complete self-contempt and seeks self-annihilation will delight (perfrueris) in abundant peace (habundancia pacis). The motif of annihilation is an important indication of the mystical nature of this chapter. It is one of the words in a configuration that indicates the awareness of nothingness. Waaijman (2003:63) points out that the motif of annihilation ("nietiging") is prominent in the mystical experience. It is about letting go of oneself in order to be transformed, noting that grace enters where mystics forget about themselves. Giving up a self-focused existence or a lifestyle that is sold out to the material and external - described in detail and eloquently in verse 11 - is the result of, and creates space for a complete focus on the Lord and for the Lord to inhabit in him. It is about detachment, about a prayerful longing for interiority, for the deeper, mystical life that is grounded outside and despite of oneself. The total and absolute dedication to the Lord and the submission to his will has as counterpart the giving up of one's own interest - which is spelled out in great detail in the remainder of this chapter. This relinquishing of own concerns is spelled out most strongly and mystically in verse 13. The disciple who comes to "complete self-contempt" will delight in "abundant" peace. This insight is confirmed and explained in much detail elsewhere in the Imitatio, for example, in Chapter 4.23:

Grant, most sweet and loving Jesus, that I may seek my repose in You above every creature; above all health and beauty; above every honour and glory; every power and dignity; above all knowledge and cleverness, all riches and arts, all joy and gladness; above all fame and praise, all sweetness and consolation; above every hope and promise, every merit and desire; above all the gifts and favours that You can give or pour down upon me; above all the joy and exultation that the mind can receive and feel; and finally, above the angels and archangels and all the heavenly host; above all things visible and invisible; and may I seek my repose in You above everything that is not You, my God.

A further illuminating example of the mystical nature of the Imitatio is to be found in Book 4.42:

Deepen Your love in me, O Lord, that I may learn in my inmost heart how sweet it is to love, to be dissolved, and to plunge myself into your love. Let your love possess me, and raise me above myself with a fervour and wonder above all imagination. Let me sing the song of love. Let me follow you, my Beloved, into the heights. Let my soul spend itself in your praise, rejoicing for love.31

6. CONCLUSION

The Imitatio Christi is a text that inspired readers time and again everywhere. This contribution reflected on this beautiful impact of the text in terms of its subtle indications that portray the spiritual journey as beautiful and fulfilling, despite hardship, struggles, adversity, and uncertainty. It also guides the reader to look beyond superficial attractiveness and prettiness that religious experiences may generate. Peace is not about sweetness and happy feelings. The deeper, true peace that is found outside oneself transforms even the most difficult challenges in the spiritual journey and feelings of total abandonment. When the spiritual journey is focused on the beautiful gift of peace from the divine, one's own concern and fate is of hardly any interest and consequence.

Finally, not only the spiritual contents of peace are attractive. Peace found in Christ inspires one to talk about peace in beautiful language so that it enchants the listener. Even one's language and one's speech reflect the attractiveness of true and real peace. Once one has interiorised true peace, to become a matter of the "whole heart", and once one then inhabits the space of peace in Christ as an integral part of the spiritual journey, one talks and lives in such a way, so that the reader and listener are also enthralled by it and filled with longing to live in this peace.

The Modern Devotion was a bookish movement, as was briefly noted in footnote 9. It set up libraries, sought to educate its followers, and promoted the study of biblical and spiritual books to the extent that it even concretely indulged in a culture of producing the most beautifully ornate texts. Even its many adherents, who could not read, were exposed to readings and discussions of the wisdom in their spiritual documents in communal meetings and deliberations. This bookish culture nurtured a deep understanding of the spiritual way. It illuminates and helps explain the aesthetic nature of the Imitatio. Whether directly or indirectly, authors and readers were exposed to aesthetical conventions as they were used to write and produce their spiritual literature. Not only its contents, but also its language and its presentation contributed to the great impact that the Imitatio had and has on generations of spiritual pilgrims. Its beauty was the reason for its profound influence.

7. A CLOSE READING OF IMITATIO CHRIST 4.25

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Becker, E-M. 2020. Paul on humility. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press. Baylor-Mohr Siebeck Studies in Early Christianity. [ Links ]

Becker, K.M. 2002. From the treasure house of Scripture. An analysis of Scriptural sources in "De Imitatione Christi". Turnhout: Brepols. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.IPM-EB.5.112153 [ Links ]

Betz, H-D. 1975. The literary composition and function of Paul's Letter to the Galatians. New Testament Studies 21:353-378. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500009619 [ Links ]

Breck, J. 2005. Imitation of Christ. In: J.-Y. Lacost (ed.), Encyclopedia of Christian Theology 3 (New York/London: Routledge). [ Links ]

Delaissé, L 1956. Le manuscrit autographe de Thomas a Kempis et 'Limitation de Jésus-Christ': Examen archéologique et edition diplomatique du Bruxellensis 5855-61, Les publications de Scriptorium, 2, vol. 2: Texte. Amsterdam: Standaard-Boekhandel. [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2008a. Towards a spirituality of peace. Acta Theologica Supplementum 11:213-251. [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2008b. Peace in Luke and Acts. A perspective on Biblical spirituality. APB 19:110-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/10226486.2008.11745790 [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2009. Peace in the Pauline letters. A perspective on Biblical spirituality. Neotestamenica 43(1):1-26. [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2014. Union with the transcendent God in Philo and John's Gospel. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 70(1), Art. #2749, 8 pages. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v70i1.2749 [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2016. Re-enchanted by beauty. On aesthetics and mysticism. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 72(4), 7 pages. [Online.] Retrieved from: doi:https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v72i4.3462 [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2019a. Beauty in the Book of Revelation. On Biblical spirituality and aesthetics. Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 19(1):1-20. https://doi.org/10.1353/scs.2019.0001 [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2019b. Apocalypses and mystical texts: Investigating prolegomena and the state of affairs. In: J.J. Collins, P.G.R. de Villiers and A. Collins (eds.), Apocalypticism in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity (Berlin: De Gruyter), pp. 7-59. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110597264-002 [ Links ]

De Villiers, P.G.R. 2021. The beauty of the monastic life. The Imitatio Christi 1.17 from an aesthetical perspective. Ons Geestelijk Erf 91(3/4):352-384. [ Links ]

Harrap, D.A. 2016. The phenomenon of prayer: The reception of the Imitatio Christi in England (1438-c.1600). Unpublished doctoral thesis, London: Queen Mary University of London. [ Links ]

Hiertaranta, P.S. 1984. A functional note on topicalization. English Studies 65(1):48-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00138388408598302 [ Links ]

Hofman, R. 2003. Het rumineren van de De Imitatione Christi in Thomas van Kempen en zijn navolging van Christus. Ons Geestelijk Erf 77(1/2):30-42. https://doi.org/10.2143/OGE.77.1.504902 [ Links ]

Huls, J. 2006. The use of Scripture in The Imitation of Christ by Thomas A. Kempis. Acta Theologica Supplementum 8:63-83. [ Links ]

Kennedy, G.A. 1980. Classical rhetoric and its Christian and secular tradition from ancient to modern times. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1770910 [ Links ]

Koopman, W.F. 2010. Topicalization in Old English and its effects. Some remarks. In: R. Hickey and S. Puppel (eds), Language history and linguistic modelling: A festschrift for Jacek Fisiak on his 60th birthday (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), pp. 307-322. [Online.] https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110820751.307 [ Links ]

Kubsch, F. 2018. Crossing boundaries in Early Modern England: Translations of Thomas a Kempis' De Imitatione Christi (1500-1700). Münster: LIT. [ Links ]

Lorenz, B. 2017. Parallelism. LitCharts LLC. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.litcharts.com/literary-devices-and-terms/parallelism [ Links ]

Peters, G. 2021. Thomas á Kempis. His life and spiritual theology. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books. [ Links ]

Peters, L 1900. Taal en stijl der Imitatio Christi. Katholiek 118:277-295; 461-473. [ Links ]

Ruelens, C. 1885. Thomas a Kempis, Thomas van Kempen, The Imitation of Christ: Being the Autograph Manuscript of Thomas ä Kempis, De imitatione Christi. Produced in Facsimile from the Original Preserved in the Royal Library at Brussels, facs. by Charles Ruelens (London: Elliot Stock). [Online.] Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/imitationofchris00ruel/page/n47 [ Links ]

Schepers, K. 2010. Literary style as cultural code. A case study of the Early Ruusbroec translations by Willem Jordaens and Geert Grote. In: K. Schepers and F. Hendrickx (eds.), De letter levend maken: Opstellen aangeboden aan Guido de Baere bij zijn zeventigste verjaardag (Leuven: Peeters), pp. 525-558. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, M. 2014. The Devotio Moderna, the emotions and the search for "Dutchness". Bijdragen en mededelingen betreffenden de geschiedenis der Nederlanden 129:20-41. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.9540 [ Links ]

Van Dijk, R. (Ed. and Tr.) 2008. Navolging van Christus. Kampen: Ten Have. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, R. (Ed. and Tr.) 2011. Gerard Zerbolt van Zutphen: Geestelijke opklimmingen. Een gids voor de geestelijke weg uit de vroege Moderne Devotie. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2002. Spirituality: Forms, foundations, methods. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2003. Mystieke ervaring en mystieke weg. In: J. Baers, G. Brinkman, Auke Jelsma et al. (eds.), Encyclopedie van de mystiek. Fundamenten, tradities, perspectieven (Kampen/Tielt: Kok/Lannoo), pp. 57-79. [ Links ]

Waaijman, K. 2006. What is spirituality? Acta Theologica Supplementum 8:1-18. [ Links ]

Date received: 22 April 2022

Date accepted: 29 April 2022

Date published: 20 June 2022

1 Early Jesuit interpreters of the book were, for example, critical of the Imitatio, because they regarded it as a mystical text (Van Dijk 2008:10). This contribution argues that the book is indeed mystical in nature, especially because of the arrangement of its four books from Book 1 about ammoniciones for all, Book 2 on the interior life, and Book 3 on being invited to become a disciple of Christ, up to the climactic Book 4 on inner consolation that speaks of interaction between the Lord (Domine) and the Son (fill). See the important remarks in Van Dijk (2008:13).

2 For a recent discussion about Thomas' influence in his time and his ongoing relevance, see Peters (2021:67-138).

3 The "In quibus" in the heading reappears in verse 9 and confirms its function to summarise the chapter's contents. In verse 9, the phrase systematises the preceding and following verses as the main components of the chapter.

4 He did so carefully - in some instances, writing them in rhyme, as is the case with the heading in 1.10: De monastica vita. There are other striking literary techniques such as alliteration in the heading of 4.25: In quibus firma pax cordis et verus profectus consistit as well as the rhythmic assonance in verus profectus consistit. Peters (1900:279) refers to other passages in 1.4, 11, 4.1, 59 and in 3.7, 10, 13, 18, 38, 45-48, 51, 52, 55, 57 and 59.

5 For detailed information about the headings in the Imitatio, see the careful study of the autograph by Delaissé (1956:18-21, 146, 179-180).

6 This contribution is part of my wider interests in aesthetics as an important new development that complements existing paradigms of research and provides new insights for the interpretive task. For a full discussion, see De Villiers (2016, 2019, 2021). It further continues my previous research on the Imitatio as an aesthetic text (De Villiers 2021), but it also fits into my broader investigation of key themes in spirituality (for example, De Villiers 2008a, 2008b, 2009). I am indebted to Kees Waaijman for his groundbreaking research on key themes in spirituality that characterise spiritualities and that inspired me to engage in this research. Through his paradigmatic analyses, he distilled four of the most prominent themes in all forms of spiritualities, namely awe of God, holiness, perfection, and mercy (Waaijman 2002:315-331). He indicates that the spirituality of various faith traditions would have more such key themes, given their particular time and context. Peace is a key theme in Christian spirituality.

7 The importance of peace in the book as a whole is already evident from many references to peace as a motif. The following random selection of some passages from the Imitatio, in which peace is extensively and thematically discussed, confirms the significance of peace: 1.11: Obtaining peace and of zeal for spiritual progress; 2.3: Of a good, peaceable person; 4.2: How our peace must not be set on human beings; 1.3: The pure, simple, and steadfast spirit is not distracted by many labours, for he does them all for the honour of God. And since he enjoys interior peace, he seeks no selfish end in anything; 1.4: A good life makes a person wise according to God and gives experience in many things, for the humbler one is and the more subject to God, the wiser and the more at peace the person will be in all things; 1.6: the person who is poor and humble of heart lives in a world of peace. True peace of heart, then, is found in resisting passions, not in satisfying them. There is no peace in the carnal person, in the person given to vain attractions, but there is peace in the fervent and spiritual person; 1.9: Such become discontented and dejected on the slightest pretext; they will never gain peace of mind unless they subject themselves wholeheartedly for the love of God.

8 This does not come unexpectedly, since the Devotio Moderna was also a textual community. Van Dijk (2014:25) refers in this regard to work by Stock who notes how reading and writing were regarded "as indispensable in learning to focus on God and preparing for meditation and prayer". Though lay members were unable to read "customary readings at table, manual labour and at religious services ensured that they would also be immersed in texts".

9 The history of Biblical Studies as a discipline displays a constant interest in the way in which texts are composed, as is, for example, evident in the many reflections on linguistic and literary theories such as structuralism, formalism, narratology, and generative grammar, but also source criticism and redaction criticism. For this, see among others, the well-known publication of Kennedy (1980) and for biblical texts, Betz (1975). The recent interest in the Bible and aesthetics is partially a logical extension of these interpretive traditions. It also reflects the growth of aesthetics as a discipline in recent times. For a full description, see De Villiers (2016).

10 It is sometimes alleged that the Imitatio lacks coherence. Recent research shows that arguments against the continuity of contents and the coherence of the Imitatio are not convincing. See, for example, Van Dijk (2008:12-13) and Hofman (2003:21-25) who remarked that Thomas' meticulous application of style is matched by the ordering of the Imitatio in a harmonious structure. Not only the macrostructure of the book displays coherence, but the individual passages are also carefully composed - as will be discussed in the remainder of this contribution.

11 Peters (1900:468-470) notes how Thomas modified words for the sake of rhyming. This meticulous attention to aesthetic nature is one reason why it took twenty years to complete the Imitatio (Hofman 2003:30).

12 See, for example, Lorenz (2017), who notes how parallelism is an important tool at any writer's disposal and can be used for a variety of purposes: "To emphasize the relationship between two or more sentences in a paragraph, or two or more ideas within a single sentence; to compare or contrast two different things or ideas; to create a stronger sense of rhythm in a text; to drive home a point through repetition; to elaborate on an idea." Especially insightful is the remark that parallelism is "one of the rules of grammar that makes ideas (both simple and complex) easier to understand".

13 Two examples of the many assonances are cupias uel queras (verse 7) and prospera et contraria: omnia equa (verse 11).

14 Recently, Breck (2005) drew attention to the fact that the rhythmic sentences enable the easy memorising of the Imitatio.

15 See the discussion about interiorising further below.

16 For a fuller description of interpreters who recognised the text's aesthetic quality, see De Villiers (2021:3-4). Of special importance is a remark by Ruelens (1885:13) that the aesthetic form wanted to "effect that cadence, that charm which speech requires to make it penetrate into the hearer's soul". He refers to the unique style of the Imitatio, noting that the external structure of the sentence "marks its outline and establishes a complete harmony between the internal structure of the ideas". He compares the style to that of mystical authors from the school of Ruysbroek and Groote. For the various understandings of style in different context and times, and its impact on the reception of the Imitatio, see Schepers (2010:525-558). Harrap (2016:27-28) argues that the Imitatio has a highly artificial style that is focused on syllabic balance and repetition. All these remarks confirm the aesthetic nature of the text.

17 Space does not allow a detailed analysis of the whole chapter, but the general remarks in the remainder of this contribution are founded on such an analysis.

18 This chapter starts with the remark: "If you wish peace and concord with others." See further De Villiers (2021:352-384).

19 See the discussions in Becker (2002:224) and Hofman (2003).

20 All four parts of the Imitatio Christi begin with quotations from the Bible. Thomas thus frames his reflections on peace by using biblical language. Even more so, he uses words of Christ, thus continuing his focus on the imitation of Christ. He began the Imitatio in Book 1.1 with a quotation from John 8:12, "Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness"; Book 2.1 with a quotation from Luke 17:21, "The kingdom of God is in you", and Book 3.1 with a collection of five quotations from Matthew 11:28; John 6:52; Luke 22:19, and John 6:56, 6:64.

21 This link between the two units is further underlined through the rhyme in which the words all end in -is.

22 Note the emphatic ego do vobis, inserted three times in the sentence final position of each of the three phrases in verse 1. In addition, peace is linked with the possessive nouns to "my" peace (pacem meam; pax mea).

23 For this section, see Van Dijk (2011:127) on the early author from the Devotio Moderna, where he discusses its author Geert Zutphen's views on virtues and vices. For Zutphen, one overcomes vices through the quest for virtues. This includes three phases: "Dit betekent dat men, ongeacht om welke ondeugd het gaat, altijd drie fasen moet doormaken: die van de beginnelingen (incipientes), die van de gevorderden (procientes) en die van de volmaakten (perfecti)." It is, therefore, about a process of interiorising virtues and overcoming vices.

24 Note, for example, the following passage from the Imitatio (4.7), where this relationship of interiority with virtues is formulated extensively as follows: "For a man's merits are not measured by many visions or consolations, or by knowledge of the Scriptures, or by his being in a higher position than others, but by the truth of his humility, by his capacity for divine charity, by his constancy in seeking purely and entirely the honor of God, by his disregard and positive contempt of self, and more, by preferring to be despised and humiliated rather than honored by others."

25 Space does not allow an extensive description of mysticism. Helpful in this regard is the overview in Waaijman (2003:64-68). See the discussion about Waaijman's view and the following remark in De Villiers (2014:1) "His analysis, based on a phenomenological investigation of mystical experiences, lists certain characteristic elements that mystical experiences have in common. These characteristics include (1) a human longing and desire for God that (2) shifts to an awareness of a divine presence, (3) is experienced in ecstasy, (4) brings about feelings of unworthiness and nothingness, (5) is received in passivity and is encountered directly, (6) brings about unity with, (7) contemplation and (8) indwelling of the divine, (9) in a relationship of mutuality (10) that is brought to fruition in everyday practice and life."

26 My italics. This quotation is again a special example of the aesthetic quality of the Imitatio.

27 Book 4.31, where virtues are closely linked with devotion, also illuminates this interiority: "People are wont to ask how much a man has done, but they think little of the virtue with which he acts. They ask: Is he strong? rich? handsome? a good writer? a good singer? or a good worker? They say little, however, about how poor he is in spirit, how patient and meek, how devout and spiritual. Nature looks to his outward appearance; grace turns to his inward being. The one often errs, the other trusts in God and is not deceived."

28 See Waaijman's (2006:57-79) useful analysis of the mystical way and experience. His discussion is a rare and systematic attempt to provide a firm grounding for any debate on the mystical experience. Its strength is to be found in the paradigmatic methodology that supports his insights.

29 Verses 1-5 are framed by the reference to the Lord who promised peace and end with the promise of much peace to those who heed him. The middle section (B/B') focuses on those who receive true peace as the humble and meek who will be in much patience. The middle of the ring composition in section 1 is a double parallelism (B and B'; verses 2-4). In this smaller unit, peace is again topicalised when it is placed prominently in the sentence initial position. In this instance, foregrounding (or topicalisation) intensifies the cohesion of the first section and focuses the attention in more depth on the theme of peace. "Topicalization is a mechanism of syntax that establishes an expression as the sentence or clause topic by having it appear at the front of the sentence or clause. This involves a phrasal movement of determiners, prepositions, and verbs to sentence-initial position." (Koopman 2010). Hiertaranta (1984:48-51) notes that the effect of topicalisation is not to emphasise or create contrast, but rather to link different parts of a discourse. It enhances the cohesion of a text.

30 See Huls (2006:73). Rather than being some false form of self-humiliation, humility is a fundamental religious category that has to do with our willingness to be led. The proud think that they can grasp the world by means of their own logic, while those who are called by God know from experience that there is no other logic than to follow the trail of that by which they have been possessed. Becker (2020) resists the urge to cheapen humility by equating it with mere moralism. In Paul's opinion, the humble individual is one immersed in a complex, transformative way of being. The path of humility does not constrain the self; rather, it guides the self to true freedom in fellowship with others. Humility, he notes, is thus a potent concept that speaks to our contemporary anxieties and discomforts. On the importance of humility, see Peters (1900:466ff.).

31 Note, also, the contemplative Chapter 26 that follows the short, instructive Chapter 25.