Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Acta Theologica

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versión impresa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 supl.32 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup32.22

ARTICLES

From desperation to adoration: Reading Psalm 107 as a transforming spatial journey

G.T.M. Prinsloo

Department of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria. E-mail: gert.prinsloo@up.ac.za. ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4126-0311

ABSTRACT

Critical spatiality opens avenues to investigate the transforming power of the authors/redactors of the Hebrew Bible's spatial imagination. I read Psalm 107 as a spatial journey bridging the divide between the desperation of the exile and the longing of the Psalter's post-exilic authors/ redactors for Israel's complete restoration and the universal adoration of Yhwh. Psalm 107 plays a crucial role in the transition between Books IV (Pss. 90-106) and V (Pss. 107-145) and acts as a "bridge" between the desperation of the exile and the call to the universal adoration of Yhwh in the post-exilic period. Psalm 107 hints at a continuous transforming spatial journey between present realities and the longed-for eschatological establishment of a universal, divine kingdom.

Keywords: Psalm, Transformation, Spatial journey

Trefwoorde: Psalm, Tranformasie, Ruimtelike reis

1. INTRODUCTION

As the first poem in Book V of the Psalter, Psalm 107 plays an important role in the book's overall architecture (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:101-102). The connection between the urgent prayer for salvation, in order that Yhwh may be thanked and praised by his people in Psalm 106:47, and the call to thanksgiving by those who experienced his acts of salvation in Psalm 107:1-3 speaks for itself. The command הודו ליהוה (Ps. 107:1a) also occurs in Psalms 105:1 and 106:1. In both Psalms 106 and 107, the call is accompanied by a double motivation כי־טוב and כי לעולם חסדו). The same call frames Psalm 118 (vv. 1, 29) and introduces Psalm 136 (v. 1). The phrase כי לעולם חסדו also occurs in Psalm 118:2-4 and Psalm 136:2-26. Psalm 107 thus has links backward to Book IV and forward to Book V (Leuenberger 2004:283-285) and acts as a "bridge" between the two books (Stone 2013:40).1

The Psalter's narrative plot confirms this bridging function (Kratz 1996:21-28; deClaissé-Walford 2004:56; Stone 2013:41). Books I-III (Pss. 3-89) reflect on the establishment, flowering, and failure of the Davidic monarchy. Book III concludes with a prayer that Yhwh should not hide his presence (Ps. 89:47-49), but remember his former deeds of loyalty (חסדיך, 89:50) and the faithfulness he promised to David in the face of his servant's humiliation (89:50-52). Book IV (Pss. 90-106) focuses on the universal kingship of Yhwh (Pss. 93-100). It reflects the situation of Israel in exile. In Psalms 101-102, the poet addresses the dashed hopes of the exilic community and prays for the restoration of Zion. In Psalms 103-104, he gives voice to the hopes of the exiles, grounded in Yhwh's חסד (Ps. 103:4, 8, 17) as the creator and sustainer of life (Ps. 104). Psalms 105-106 focus on Yhwh's wonderful deeds (,נפלאותי, 105:5) on behalf of Israel and his acts of loyal love (חסד, 106:7; , 106:45) towards his people, in spite of their constant disloyalty towards him. Book V (Pss. 107-145) is concerned with the rebuilding of the post-exilic community. Psalm 107 resumes the theme of Yhwh's deeds of loyal love (נפלאותיו, 107:1, 8, 15, 21, 31, 43) and his wonderful deeds (נפלאותיו, 107:8, 15, 21, 31) on behalf of his people. He ended the desperation of exile (107:2-3). Israel is obliged to give thanks (107:1) and contemplate the implications of Yhwh's deeds of loyal love (107:43).

Psalm 107's bridging function surpasses the literary and compositional levels to include a spatial perspective. Critical spatiality and narratology provide useful avenues to investigate the transforming power of the authors/ redactors of the Hebrew Bible's spatial imagination. Critical spatiality's notion of "lived space as a strategic location from which to encompass, understand, and potentially transform all spaces simultaneously" (Soja 1996:68),2 and narratology's notion of

verbal story space [as something] the reader is prompted to create in imagination ... on the basis of the characters' perceptions and/or the narrator's reports (Chatman 1978:104)3

enable us to read Psalm 107 through an imaginative spatial lens. It describes a spatial journey bridging the divide between the desperation of the exile and post-exilic Israel's longing for its complete restoration and the universal adoration of Yhwh. Psalm 107 transforms the historical realities facing inhabitants of the Persian province of Yehud, the oppressive imperial-colonial ideology of the Persian empire, and the adverse lived experiences of Yehud's marginalised inhabitants (Tucker 2014:59-68, see §6). Psalm 107 re-imagines post-exilic Israel's place in the world as a spatial journey under the guidance of Yhwh, the universal king. He accompanies his people, and all peoples, on their voyage between desperation and adoration.

My analysis of Psalm 107 is informed by cultural semiotics, notably by Yuri Lotman's insistence that textual interpretation depends on the deciphering of a complex network of codes that are socially determined. Literary analyses address "questions of content, meaning, the social and ethical value of art and its ties with reality" (Lotman 1977:32). Comprehension demands an analysis of a text's intricate intratextual and all its extratextual relations, both literary (intertextual) and non-literary (extratextual) (Lotman 1977:103). I combine textual analysis (intratextuality; see §3 and §4) with an analysis of Psalm 107's literary (intertextuality; see §5) and socio-historical context(s) (extratextuality, see §6). My intertextual analysis is informed by Fishbane's (1988) notion of inner-biblical allusion and exegesis (i.e. author-intended intertextuality).4 My extratextual analysis focuses on concepts of place, space, and ancient Near Eastern world view(s) and spatial orientation(s). This analysis is informed by theoreticians in the field of narratology (Genette 1980) and critical spatiality (Tuan 1977; Lefebvre 1991; Soja 1996; see §2).

2. ON SPATIAL READINGS OF HEBREW BIBLE TEXTS

In previous publications, I elucidated theoretical approaches towards space and spatiality and applied them to Hebrew Bible texts (see Prinsloo 2005:457-477; 2006:739-760; 2013a:132-154; 2013b:3-25). In this article, I refer to three perspectives on spatiality that are essential for my reading of Psalm 107.

First, I interpret spatial references in the poem as examples of narrative space.5 The act of narration creates a world of words that is related to the real world, but not identical to it (Thompson 1978:3-4). In this world, references to space are not mere descriptions of physical locations (settings); they are representational spaces intended to affect and change the perspective of the reader/listener (focal spaces) (Van Eck 1995:137-139).

Secondly, I interpret spatial references in the poem in light of critical spatiality's notion of space as a "three-dimensional" concept.6 Lefebvre (1991:1) argued that "space" is not a geometrical concept, but a social phenomenon produced in the interaction between human beings and their environment. It is at the same time a physical, mental, and social construct.7 For this trialectic of spaces, Soja (1996:66-67) coined the terms "Firstspace", "Secondspace", and "Thirdspace". Soja (1996:68) regards Thirdspace as

the terrain for the generation of 'counterspaces,' spaces of resistance to the dominant order ... to lived space as a strategic location from which to encompass, understand, and potentially transform all spaces simultaneously.

Spatial references in Psalm 107 are representations of lived experiences. My spatial analysis is a thirdspatial exercise highlighting the transforming power of the poet's (re)imagination of Israel's place in the world.

Thirdly, spatial references in Psalm 107 are interpreted in light of ancient Near Eastern world view(s) and spatial orientation(s),8 which - in broad terms - can be plotted along a horizontal and vertical axis (Wyatt 2001:35-40). Horizontally, orientation is towards the east. "In front" is east, "behind" is west, "right" is south, "left" is north. "Far" and "near" are key concepts: to be far is negative, to be near is positive. Vertically, the cosmos is imagined as consisting of three building blocks: heaven, earth and netherworld (Horowitz 1998:xii).9 Earth

lies as a flat plate ... horizontally at the centre of a great sphere. Outside this sphere, above, below, and around ... lies the 'cosmic ocean' (Wyatt 2001:55),

which symbolises the primeval waters of chaos and is an extension of the netherworld. "Up" and "down" are key concepts: to ascend is positive, entering the realm of the gods; to descend is negative, entering the realm of the netherworld and cutting off contact with the divine sphere (Wyatt 2001:40). The cosmic centre, usually conceptualised as a mountain, lies at the intersection of the horizontal and vertical axes. This cosmic mountain "is the point of access to heaven" (Wyatt 2001:147), where the temple of the high god stands. It represents sacred space, the meeting point of the divine and human spheres (Janowski 2002:34-37). The far-near and ascend-descend dichotomy leads to the idea of boundaries between spaces. The city is regarded as a safe space, the steppe outside as unsafe, an area where robbers and demons lurk. The temple in the heart of the city is a holy place, the world outside is unholy (Berlejung 2006:66-67).

For Israel, the temple in Jerusalem represents the spatial centre of the universe. On the horizontal plane, to be in Jerusalem is to be at the centre, to experience peace and life; to be far from Jerusalem is to be on the periphery, in the realm of chaos and death (Janowski 2002:42-46). On the vertical plane, to ascend to the temple mountain is positive and is associated with Yhwh and his deliverance. To descend is negative, to leave Yhwh and his saving presence, to sink into the depths of Se'ôl (Thompson 1978:59-60). Humankind is depicted either at the centre and thus "properly orientated to his world", or off-centre "in chaos and disorientation" (Thompson 1978:13).

3. PSALM 107: TEXT, TRANSLATION AND NOTES10

1 .1 1 הֹד֣וּ לַיהָו֣ה כִּי־ט֑וֹב 1a Give thanks to Yhwh for (he is) good,

כִּ֖י לְעוֹלָ֣ם חַסְדּֽוֹ׃ b because forever (is) his loyalty.

.2 2 י֭אֹמְרוּ גְּאוּלֵ֣י יְהָו֑ה 2a Let the redeemed of Yhwh say (so),11

אֲשֶׁ֥ר גְּ֜אָלָ֗ם מִיַּד־צָֽר׃ b those that he redeemed from the hand of an adversary,12

3 וּֽמֵאֲרָצ֗וֹת קִ֫בְּצָ֥ם3 a and from lands he gathered them,

מִמִּזרְָח֥ וּמִמַּֽערֲָב֑ b from east and from west,

מִצָּפ֥וֹן וּמִָיּֽם׃ c from north and from sea.13

2 .1 .1 4 תָּע֣וּ בַ֭מִּדְבָּר בִּישִׁימ֣וֹן דָּ֑רֶךְ 4a They staggered in the wilderness on a tangled road,14

עִ֥יר מ֜וֹשָׁ֗ב ל֣אֹ מָצָֽאוּ׃ b a habitable city they could not find.

5 רְעֵבִ֥ים גַּם־צְמֵאִ֑ים5a Hungry, also thirsty,

נַ֜פְשָׁ֗ם בָּהֶ֥ם תִּתְעַטָּֽף׃ b their life in them ebbed away,

.2 6 וַיִּצְעֲק֣וּ אֶל־יְה֭וָה בַּצַּ֣ר לָהֶ֑ם 6a but they cried to Yhwh in their adversity,

מִ֜מְּצֽוּקוֹתֵיהֶ֗ם יַצִּילֵֽם׃ b from their distress he delivered them,

7 יּדְֽרִיכֵם בְּדֶ֣רֶךְ יְשָׁרָ֑ה 7a and he led them on a straight road,

לָ֜לֶ֗כֶת אֶל־עִ֥יר מוֹשָֽׁב׃ b to go to a habitable city.

.3 8 יוֹד֣וּ לַיהָו֣ה חַסְדּ֑וֹ 8a Let them give thanks to Yhwh (for) his loyalty,

וְ֜נִפְלְאוֹתָ֗יו לִבְנֵ֥י אָדָֽם׃ b and his wonderous deeds for the sons of man,

9 כִּי־הִ֭שְׂבִּיעַ נֶפֶ֣שׁקֵקָ֑ה9a for he satisfies a parched person,

וְנֶ֥פֶשׁ רְ֜עֵבָה מִלֵּא־טֽוֹב׃ b and a hungry person he fills good.

.2 .1 .1 10 יֹ֭שְׁבֵי חֹ֣שֶׁךְ וְצַלְמָ֑וֶת 10a The dwellers of darkness and deep gloom,

אֲסִירֵ֖י עֳנִ֣י וּבַרְֶזֽל׃ b prisoners of misery and iron (fetters),

11 כִּֽי־הִמְר֥וּ אִמְרֵי־אֵ֑ל 11a because theyrebelled (against) the words of God,

וַעֲצַ֖ת עֶלְי֣וֹן נָאָֽצוּ׃ b and the counsel of the Most High they despised:

.2 12 וַיַּכְנַ֣ע בֶּעָמָ֣ל לִבָּ֑ם 12a He humbled by trouble their heart,

כָּ֜שְׁל֗וּ וְאֵ֣ין עֵֹזֽר׃ b they stumbled and there wasno helper,

.2 13 וַיִּזְעֲק֣וּ אֶל־יְה֭וָה בַּצַּ֣ר לָהֶ֑ם 13a but they called upon Yhwh in their adversity,

מִ֜מְּצֻֽקוֹתֵיהֶ֗ם יוֹשִׁיעֵֽם׃ b from their distresses he saved them,

14 יֽ֭וֹצִיאֵם מֵחֹ֣שֶׁךְ וְצַלְמָ֑וֶת 14a he brought them from darkness and deep gloom,

וּמוֹסְר֖וֹתֵיהֶ֣ם יְנַתֵּֽק׃ b and their chains he tore (apart).

.3 15 יוֹד֣וּ לַיהָו֣ה חַסְדּ֑וֹ 15a Let them give thanks to Yhwh (for) his loyalty,

וְ֜נִפְלְאוֹתָ֗יו לִבְנֵ֥י אָדָֽם׃ b and his wondrous deeds for the sons of man,

16 כִּֽי־שִׁ֭בַּר דַּלְת֣וֹת נְח֑שֶֹׁת 16a for he shatters gates of bronze,

וּבְרִיחֵ֖י בַרְֶז֣ל גִּדֵּֽעַ׃ b and bars of iron he cuts through.

.3 .1 17 אֱ֭וִלִים מִדֶּ֣רֶךְ פִּשְׁעָ֑ם 17a Fools they were because of their sinful way,15

וּֽ֜מֵעֲוֹֽנֹתֵיהֶ֗ם יִתְעַנּֽוּ׃ b and their iniquities brought affliction over them.

18 כָּל־אֹ֭כֶל תְּתַעֵ֣ב נַפְשָׁ֑ם 18a All food - their throat abhors it,

וַ֜יַּגִּ֗יעוּ עַד־שַׁ֥עֲרֵי מָֽוֶת׃ b and they reached the gates of death,

.2 19 וַיִּזְעֲק֣וּ אֶל־יְה֭וָה בַּצַּ֣ר לָהֶ֑ם 19a but they called upon Yhwh in their adversity,

:מִ֜מְּצֻֽקוֹתֵיהֶ֗ם יוֹשִׁיעֵֽם׃b from their distresses he saved them.

20 יִשְׁלַ֣ח דְּ֭בָרוֹ וְיִרְפָּאֵ֑ם20a He sent forth his word, and he healed them,

וִֽ֜ימַלֵּ֗ט מִשְּׁחִיתוֹתָֽם׃ ׆ b and he rescued (them) from their humiliations.

.3 21 ׆ׄ יוֹד֣וּ לַיהָו֣ה חַסְדּ֑וֹ21a Let them give thanks to Yhwh (for) his loyalty,16

וְ֜נִפְלְאוֹתָ֗יו לִבְנֵ֥י אָדָֽם׃ b and his wondrous deeds for the sons of man,

22 ׆ׄ וְ֭יִזְבְּחוּ זִבְחֵ֣י תוֹדָ֑ה 22a Let them sacrifice sacrifices of thanksgiving,

וֽיסַפְּר֖וּ מַעֲשָׂ֣יו בְּרִנָּֽה׃ b and let them proclaim his works with a shout of joy.

.4 .1 .1 23 ׆ׄ יוֹרְדֵ֣י הַ֭יָּם בָּאֳנִיּ֑וֹת 23a Those going down to the sea upon ships,

עשֵֹׂ֥י מְ֜לָאכָ֗ה בְּמַ֣יִם רַבִּֽים׃ b those doing work upon mighty waters,

24 ׆ׄ הֵ֣מָּה רָ֭אוּ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י יְהוָ֑ה24a they - they saw the works of Yhwh,

וְ֜נִפְלְאוֹתָ֗יו בִּמְצוּלָֽה׃ b and his wondrous deeds in a depth.

.2 ׆ וַיּ֗אֹמֶר וַֽ֭יַּעֲמֵד ר֣וּחַ סְעָרָ֑ ה25a Yes, he spoke, and he raised a wind of storm,

וַתְּרוֹמֵ֥ם גַּלָּֽיו׃ b and she raised high his waves.

.3 26 ׆ יַעֲל֣וּ שָׁ֭מַיִם יֵרְד֣וּ תְהוֹמ֑וֹת 26a They ascended (to) heavens, they descended (to) depths,

נַ֜פְשָׁ֗ם בְּרָעָ֥ה תִתְמוֹגָֽג׃ b their life - in peril she melted away.

27 יָח֣וֹגּוּ וְ֭יָנוּעוּ כַּשִּׁכּ֑וֹר 27a They reeled and staggered like the drunkard,

וְכָל־חָ֜כְמָתָ֗ם תִּתְבַּלָּֽע׃ b and all their wisdom - she proved herself confused,

.2 .1 28 וַיִּצְעֲק֣וּ אֶל־יְה֭וָה בַּצַּ֣ר לָהֶ֑ם 28a but they cried to Yhwh in their adversity,

וּֽ֜מִמְּצֽוּקֹתֵיהֶ֗ם יוֹצִיאֵֽם׃ b and from their distresses he brought them.

.2 29 יקָם סְ֭עָרָה לִדְמָמָ֑ה 29a He stilled a storm to a whisper,

וַ֜יֶּחֱשׁ֗וּ גַּלֵּיהֶֽם׃ b and their waves were hushed.

30 וַיִּשְׂמְח֥וּ כִֽי־יִשְׁתֹּ֑קוּ 30a And they rejoiced because they grew silent,

וַ֜יַּנְחֵ֗ם אֶל־מְח֥וֹז חֶפְצָֽם׃ b and he guided them to their desired place.17

.3 31 יוֹד֣וּ לַיהָו֣ה חַסְדּ֑וֹ 31a Let them give thanks to Yhwh (for) his loyalty,

וְ֜נִפְלְאוֹתָ֗יו לִבְנֵ֥י אָדָֽם׃ b and his wondrous

deeds for the sons of man,

32 וִֽ֭ירֹמְמוּהוּ בִּקְהַל־עָ֑ם , 32a and let them exult him in

the assembly of people,

וּבְמוֹשַׁ֖ב זְקֵנִ֣ים יְהַלְלֽוּהוּ׃ b and in the council of elders let them praise him.

3 .1 .1 33 יָשֵׂ֣ם נְהָר֣וֹת לְמִדְבָּ֑ר 33a He turns rivers into a wasteland,

וּמֹצָ֥אֵי מַ֜֗יִם לְצִמָּאֽוֹן׃ b and flowings of waters into thirsty ground,

34 אֶ֣רֶץ פְּ֭רִי לִמְלֵחָ֑ה 34a a land of fruit into a salt waste,

מֵ֜רָעַ֗ת יֹ֣שְׁבֵי בָֽהּ׃ b because of the evil of those who dwell in her.

.2 35 יָשֵׂ֣ם מִ֭דְבָּר לַֽאֲגַם־מַ֑יִם 35a He turns a desert into a pool of water,

:וְאֶ֥רֶץ צִ֜יָּ֗ה לְמֹצָ֥אֵי מָֽיִם׃ b and a land of waterlessness into flowings of waters.

.2 .1 36 וַיּ֣וֹשֶׁב שָׁ֣ם רְעֵבִ֑ים36a He caused to live there hungry (people),

וַ֜יְכוֹנְנ֗וּ עִ֣יר מוֹשָֽׁב׃ b and they founded a habitable city.

.2 37 וַיִּזְרְע֣וּ שָׂ֭דוֹת וַיִּטְּע֣וּ כְרָמִ֑ים 37a And they sowed fields and they planted

וַ֜יַּעֲשׂ֗וּ פְִּר֣י תְבֽוּאָה׃ b and they produced a yield of fruit.

38 וַיְבָרֲכֵ֣ם וַיִּרְבּ֣וּ מְאֹ֑ד38 a And he blessed them, and they increased greatly,

וּ֜בְהֶמְתָּ֗ם ל֣אֹ יַמְעִֽיט׃ b and their cattle he did not let diminish.

.3 39 וַיִּמְעֲט֥וּ וַיָּשֹׁ֑חוּ39a And they decreased and became humbled

מֵעֹ֖צֶר רָעָ֣ה וְיָגֽוֹן׃ b because of oppression, calamity and sorrow.

.3 .1 40 ׆ׄ שֹׁפֵ֣ךְ בּ֭וּז עַל־נְדִיבִ֑ים r 40a It is he who pours contempt upon nobles.

וַ֜יַּתְעֵ֗ם בְּתֹ֣הוּ לאֹ־דָֽרֶךְ׃ b and he made them stagger in a wasteland without a road.

41 וַיְשַׂגֵּ֣ב אֶבְי֣וֹן מֵע֑וֹנִי 41a But he lifted a poor from affliction,

וַָיּ֥שֶׂם כַּ֜צּ֗אֹן מִשְׁפָּחֽוֹת׃ b and he made like a flock (their) clans.

4 .1 42 יִרְא֣וּ יְשִָׁר֣ים וְיִשְׂמָ֑חוּ 42a Upright people will see and they will rejoice,

וְכָל־עַ֜וְלָ֗ה ק֣פְצָה פִּֽיהָ׃ b but every injustice - she shuts her mouth.

43 מִי־חָכָ֥ם וְיִשְׁמָר־אֵ֑לֶּה 43a Who (is) wise? Let him consider t hese things,

וְ֜יִתְבּֽוֹנְנ֗וּ חַֽסְדֵ֥י יְהָוֽה׃ b and let them gain insight into Yhwh's acts of loyalty.

4. PSALM 107: AN INTRATEXTUAL READING

Psalm 107 commences with an exhortation (v. 1) that also occurs at the end of Book IV, permeates Book V and, together with verbs from the sematic field "praise" (וירממוהו and יהללוהו, v. 32), set the tone for the entire collection (Tucker 2014:59).18 The poem is surprisingly vague. It displays a "they-he" communicative pattern between an unidentified group of people and Yhwh.19 Behind the scenes, a third character lurks, namely multiple manifestations of powers of chaos and death. The lack of specificity indicates that Psalm 107 "is a programmatic opening" to Book V, developing

the message of the rescue of Israel from exile that is already happening and its miraculous restoration as Yhwh's people, Yhwh's household and family (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:112).

According to Tucker (2014:59), the poem is "a didactic meditation on Israel's deliverance from exile" (see §5).

Verbs associated with the "they" group belong to the semantic fields suffering/distress, sin/transgression, salvation/restoration, and thanksgiving/devotion,20 while verbs associated with the fields salvation/ care, punishment, and acts in nature/history characterise Yhwh's actions.21Psalm 107 describes the collective experiences of people in distress. They suffered severely, often due to their own sinful behaviour. However, when they called upon Yhwh for help, he displayed his loyalty by saving them. They are now under an obligation to perform acts of thanksgiving and devotion.

Four stanzas can be demarcated (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:99-103; Kartje 2014:145-146):

Stanza 1:Vv. 1-3: Call to thanksgiving and motivation

Stanza 2:Vv. 4-32: Narration of four groups in distress, their cry for help, and subsequent salvation

Stanza 3:Vv. 33-41: Hymnic celebration of Yhwh's transformative power

Stanza 4:Vv. 42-43: Admonition to pay close attention to YHWH's deeds and become wise.

Repetition of keywords ensures close cohesion between the stanzas (Van der Ploeg 1974:225). The lexemes יהוה "Yhwh" (vv. 1, 2, 6, 8, 13, 15, 19, 21, 24, 28, 31, 43) and חסד "loyalty" (vv. 1, 8, 15, 21, 31, 43) link Stanzas 1, 2 and 4 and create an inclusio between Stanzas 1 and 4. Stanzas 1 and 2 are linked by the repetition of ידה "to give thanks" (vv. 1, 8, 15, 21, 22, 31), טוב "good" (vv. 1, 9), and צר "adversary/adversity" (vv. 2, 6, 13, 19, 28). Water, as symbol of chaos and death, appears in Stanza 1 (ים "sea", v. 3). The theme is developed in Stanzas 2 and 3 by the repetition of ים "sea" (v. 23) and the related terms מים "water" (vv. 23, 33, 35); מצולה "deep" (v. 24); סערה "tempest" (vv. 25, 29); גלים "waves" (vv. 25, 29); תהום "primeval ocean" (v. 26), and נהר "river" (v. 33). The repetition of תעה "stagger" (vv. 4, 40); מדבר "wilderness" (vv. 4, 33, 35, 40); דרך "to walk" as verb (v. 7) and noun (vv. 4, 17, 40); the notion of עיר מושב "habitable city" (vv. 4, 7, 36) and the related phrase מחוז חפצם "their desired place" (v. 30); ישב "to dwell" (vv. 10, 32, 34, 36); רעב "to be hungry" (vv. 5, 9, 36); רעה "evil" (vv. 26, 34, 39); צמא "to be thirsty" (vv. 5, 9, 33) and עני "misery, poor" (vv. 10, 41) marks further links between Stanzas 2 and 3. Finally, the repetition of ראה "to see" (vv. 24, 42); חכם / חכמה"wisdom / wise" (vv. 27, 43), and שמח "to rejoice" (vv. 30, 42) creates thematic links between Stanzas 2 and 4.

Stanza 1 (vv. 1-3) is introduced by a call to praise (Strophe 1.1, v. 1). It contains the command הודו ליהוה "give thanks to Yhwh", and two motivations (כי־טוב"for he is good"; כי לעולם חסדו "because forever is his love"; v. 1). Strophe 1.2, verses 2-3 provides the reason for the call to praise. The אולי יהוה "the redeemed of Yhwh" who experienced redemption מיד־צר "from the hand of an adversary" (v. 2) when Yhwh "gathered them from the lands" (ומארצות קבצם, v. 3) are obliged to give thanks to him. Two antithetical word pairs (ממזרח ומערב "from east and from west"; מצפון ומים "from north and from sea")22 suggest that this ingathering occurred from the extremities of the universe. On the horizontal (ממזרח ומערב) and vertical (מצפון ומים) levels, verse 3 expresses a complete spatial "transportation" - people who were far away, off-centre, at the universe's extremities, in danger, and confronted by death are redeemed by Yhwh and gathered at the centre (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:104).

Three themes from this stanza also resonate in Stanzas 2 (vv. 4-32) and 3 (vv. 33-41), namely the obligation to thanksgiving (ידה); Yhwh's enduring loyalty towards his people (חסד), and his redemptive transportation of the people from life-threatening distress to being saved and at the centre (גאל). Stanza 1's emphasis on the loyalty of Yhwh (חסד, v. 1) resurfaces in Stanza 2 (vv. 8, 15, 21, 31) and echoes Stanza 4 (vv. 42-43). An obligation rests upon those who experienced salvation to take Yhwh's acts of loyalty ((חסדי יהוה to heart and act wisely (v. 43).

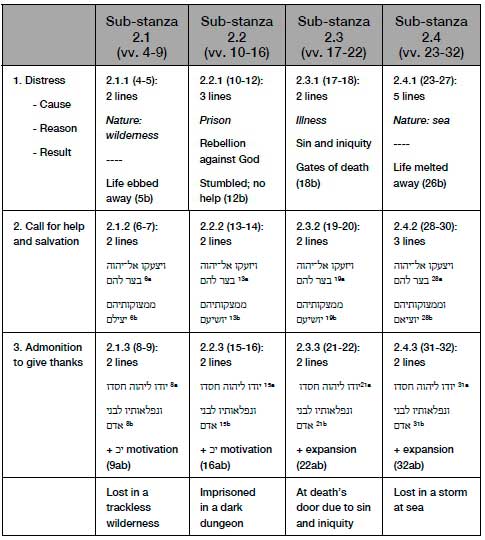

In four sub-stanzas, Stanza 2 (vv. 4-32) expands the notion that Yhwh gathered people from four dangerous extremities of the universe (v. 3).23The stanza contains symbolic scenes of mortal danger inflicted upon people and Yhwh's salvific intervention when they called for help (Goulder 1998:117). The following table notes subtle similarities and differences between the sub-stanzas:

Each sub-stanza reflects the spatial movement hinted at in Stanza 1. Those who were far from Yhwh, in distress, confronted by hardship and death and off-centre called upon Yhwh and he saved them. They are now close to Yhwh, at the centre. For this reversal of fortunes, they should thank him. The stylised form of the sub-stanzas warns against attempts to identify specific and different historical situations behind each scene. They represent the extremities of creation, where םדא ינב "human beings" (vv. 8, 15, 21, 31) discovered the saving and protective presence of Yhwh at the centre (Weber 2003:206).24

Sub-stanzas 2.1 (vv. 4-9) and 2.3 (vv. 17-22) contain six lines; sub-stanza 2.2 (vv. 10-16) seven lines, and sub-stanza 2.4 (vv. 23-32) ten lines. Gradually, the people's distress receives more emphasis, and as the distress increases, so does the grace of Yhwh (Van der Ploeg 1974:225).

On the one hand, the sub-stanzas display a linear development towards a climax. Sub-stanzas 2.1 (vv. 4-9) and 2.2 (vv. 10-16) contain a motivation for the call to thanksgiving introduced by the particle כי (vv. 9, 16). In the case of sub-stanzas 2.3 (vv. 17-22) and 2.4 (vv. 23-32), the call to thanksgiving is followed by an expansion with spatial implications (vv. 22, 32), suggesting that thanksgiving is due in the public sphere. The "experience of the saving power of Yhwh requires public thanksgiving and praise" (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:100). The sub-stanzas simultaneously display a concentric pattern. Sub-stanzas 2.1 (vv. 4-9) and 2.4 (vv. 23-32) are concerned with natural phenomena and calamities in spaces associated with danger and death - the "wilderness" (vv. 4-9) and the "sea" (vv. 23-32). Both units contain the phrase ויצעקו אל־יהוה בצר־להם (vv. 6, 28). However, in verse 6, the saving intervention of Yhwh is described in general terms (ממצוקותיהם יצילם "from their distress he delivered them"), while a term suggesting a spatial journey occurs in verse 28 (וממצוקתיהם יוציאם "and from their distress he brought them"). Sub-stanzas 2.2 (vv. 10-16) and 2.3 (vv. 17-22) are both concerned with distress suffered, due to the people's own doing (vv. 11, 17). The call for help is identical (ויזעקו אל־יהוה בצר להם "but they called upon Yhwh in their trouble", vv. 13, 19) (Weber 2003:208). A single theme, namely a complete reversal of fortunes, links all four sub-stanzas, but "two acts of salvation from sin are framed by two acts of salvation from chaos" (Mejía 1975:58).

Stanza 3 (vv. 33-41) shares links with the first and last sub-stanzas of stanza 2. With both, it shares the intervention of Yhwh in nature. With sub-stanza 2.1, it shares the themes of wandering in a wilderness, but in the end finding a habitable city. With 2.4, it shares the theme of water, both as a life-giving and sustaining gift, as in sub-stanza 2.1, and as a negative and life-threatening force, as in sub-stanza 2.4. Stanza 3 applies the theme of the reversal of fortunes in general terms with reference to Yhwh's absolute power over nature and history. Yhwh turns positive situations into negative and negative situations into positive. Strophe 3.1 (vv. 3335) illustrates Yhwh's power over creation. The movement is from negative (sub-strophe 3.1.1, vv. 33-34) to positive (sub-strophe 3.3.2, v. 35), with an inclusio created by the repetition of שים (שם, vv. 33, 35).25 A negative turn is always a real possibility מרעת ישבי בה "because of the evil of those who lived there" (v. 34). In strophes 3.2 (vv. 36-39) and 3.3 (vv. 40-41), Yhwh's transformative power is applied to the history of Israel.26 Yhwh enabled רעבים "hungry people" to establish עיר מושב a habitable city" (sub-strophe 3.2.1, v. 36), where they experienced Yhwh's positive intervention (sub-strophe 3.2.2, vv. 37-38), but ultimately Yhwh reverses their fortunes to negative space (sub-strophe 3.2.3, v. 39), when they "became humbled by oppression, calamity, and sorrow". In strophe 3.3 (vv. 40-41), this negative turn of events finds a stark ethical application.27 The historical calamity also becomes a divine judgement upon נדבים "noble people" who are forced to wander בתהו לא־דרך "in a waste without road" (v. 40, note the flashback to vv. 4-8), while Yhwh's transformative creational power (וישם, v. 41) is directed towards אביון "a poor person". Yhwh lifts the poor from affliction and makes their clans like a flock (v. 41).

The first three stanzas share the theme of a reversal of fortunes in spatial terms, while the last stanza urges the readers/listeners to take this phenomenon to heart and learn a lesson from it. Stanza 4 (vv. 42-43) resumes the theme of strophe 3.3 (vv. 40-41), by depicting a clear contrast between the fate of upright ones (ישרים) who experience joy, and every single form of injustice (וכל־עולה), which cannot open its mouth to express praise (v. 42). This should inspire the wise (חכם) to contemplate (ויתבוננו) Yhwh's actions of loyalty (חסדי יהוה). The one who is praised for his acts of salvation (v. 1) is the God of the reversal of fortunes. Praise, thanksgiving, and devotion should become a permanent way of life, unless their salvation is reversed again (v. 43).

5. PSALM 107: INTERTEXTUAL ACCENTS

The intratextual reading of Psalm 107 raises the question as to in what kind of social-historical context such a text would have communicated effectively. The immediate and remote literary context(s) suggest that the experience of exile and restoration resonates in Psalm 107 (Goulder 1998:119).

In its immediate context, multiple intertextual connections confirm a close connection between Psalms 106 and 107 (Weber 2003:209; Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:101-102). Apart from the identical opening words (Pss. 106:1; 107:1), Psalm 106:47's prayer for salvation and ingathering from dispersion is "answered" in Psalm 107:2-3 (קבץ, 106:47; 107:3). In Psalm 106:41, Yhwh gives his people "in the hand of the nations" (ביד־גוים), but in Psalm 107:2, he has already redeemed them "from the hand of the foe" (מיד־צר). In Psalm 106:41-42, Yhwh hands his people over to their foes, but in Psalm 107, he delivers them from their distress (vv. 6, 13, 19, 28). Psalm 106:14 states that Israel tempted Yhwh in the wilderness, while Psalm 107:4-9 suggests that he delivers those who are lost in the wilderness (,מדבר, 106:14; 107:4; ישימון, 106:14; 107:4). In Psalm 106, Israel is accused of sacrificing to idols (vv. 7, 13, 21, 28, 37), while Psalm 107 exhorts the redeemed to offer-up sacrifices of thanksgiving (v. 22). Psalm 106 suggests that Israel suffered hardships, due to their sin and rebellion (vv. 7, 13, 3343), and Psalm 107 ascribes hardship to people's rebellion and sin (vv. 1011, 17). In both poems, the sinners are humbled (כנע, 106:42; 107:12) and can only be saved by Yhwh (ישע, 106:4, 8, 10, 47; 107:13, 19). At the end of Psalm 106, the people in exile pray for deliverance; in Psalm 107, they look back upon Yhwh's acts of redemption and thank him for it. Psalm 107 bridges exile and restoration.

Intertextual links between Psalm 107 and the closing poems of Book IV and poems in Book V, emphasising the notion of universal thanksgiving, have already been noted (see §1). Significant are the exact parallels between Psalm 107:1 and Psalms 118:1, 29 and 136:1. With a slight variation, the verse also occurs in Psalm 136:26. The phrase כי לעולם חסדו (Ps. 107:1b) also occurs in Psalms 118:2-4 and 136:2-25. These repetitions create a "hermeneutically significant" compositional "arc" between Psalms 107, 118 and 136 (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:110). Psalm 118 is the closing poem of the Egyptian Hallel (Pss. 113-118), and the twin poems Psalms 135-136 conclude the Songs of Ascents (Pss. 120-134). Psalms 107, 118 and 136 become part of

a great literary (fictional) liturgy of thanksgiving for Israel's rescue, restoration, and renewal that had begun as a second exodus (Psalms 113-118) and continues in the pilgrimage to Zion as the center of Israel (Psalms 120-134) (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:110).

Six themes in Psalm 107 set the tone for the remainder of Book V: the notion of praise/thanksgiving (Zenger 1998:77-82; see הדו, v. 1; יודו, vv. 8, 15, 21, 31; וירממוהו, v. 32; יהללוהו, v. 32); the emphasis on Yhwh's acts of loyal love (Zenger 1998:88; see חסדו, vv. 1, 8, 15, 21, 31; חסדי יהוה, v. 43); the notion that Yhwh takes particular interest in the plight of the poor who are completely dependent upon his (Ro 2002:200-206; Bremer 2016:387-391; see אביון, v. 41); the interest in wisdom as instruction for a blessed way of life (Kartje 2014:69, 138-164; see חכם, v. 43); the poem's universal-eschatological orientation (Zenger 1998:82; see לעולםv. 1; לבניאדם, vv. 8, 15, 21, 31), and the notion that Yhwh is the universal king who suppresses all powers of chaos (see vv. 4-32), overcomes the imperial tendencies of foreign and domestic "powerful" people, and uplifts the poor from affliction (Zenger 1997:96-97; Tucker 2014:62-65, see v. 40-41). These

themes resurface in Psalm 145, suggesting that Psalms 107 and 145 serve as a deliberate frame for Book V (Zenger 1998:88-89). Psalm 107 thus links Books IV and V and becomes the paradigmatic text outlining post-exilic Israel's historical, eschatological, transforming, and still incomplete spatial journey between desperation and adoration (Bremer 2016:387).

Texts from the prophetic corpus serve as source texts for Psalm 107, notably Jeremiah 33:1-11 (Beyerlin 1979:26-27) and texts from Isaiah 40-66 (Roffey 1997:72-73; Tucker 2014:63-65). In Jeremiah 33:1-3, Yhwh assures the prophet, while he was restrained in the court of the guard (33:1; see Ps. 107:10-16), that he will reveal to him hidden things of which he is unaware (33:3; see Ps. 107:8, 15, 21, 24, 31). Jeremiah 33:4-9 promises doom and destruction for "this city" (,עיר הזה 33:4; see עיר מושב in Ps. 107:4, 7, 36) at the hand of the Chaldeans because of Judah's wickedness (,כל־רעתם, 33:5; see Ps. 107:11, 17, 34, 39). It also promises hope and healing in the future (33:6; see Ps. 107:17-22). Yhwh will reverse the fortune of Judah and Israel (והשבתי את־שבות, 33:7; see Ps. 107:6-7, 13-14, 19-20, 28-30), cleanse them from their iniquity (מכל־עונם, 33:8; see Ps. 107:10), and pardon the sins (,לכול־עונותיה, 33:8; see Ps. 107:17) they committed against him (,ואשר פשעו בי, 33:9; see Ps. 107:17). Yhwh's redemptive intervention will increase Jerusalem's reputation among the nations of the earth (־ לגויי הארץ, 33:9), while Psalm 107 lauds Yhwh's "wonderful deeds for humankind" (ונפלאותיו לבני אדם, 107:8, 15, 21, 31).28

Jeremiah 33:10-11 resonates in Psalm 107:1-3. According to Jeremiah 33:10, in "this place" (במקום־הזה), i.e. in the "cities of Judah" (בערי יהודה) and "the streets of Jerusalem" (ובחצות ירושלם), people are now saying (אמרים) that the place is a wasteland, void of human and animal habitation. Yet, verse 11 states that sounds of joy will be heard again, when people will say (אמרים):

הוֹדוּ֩ אֶת־יְה ֙ והָ צְבָא֜וֹת "Give thanks to Yhwh Sebãôt,

כִּֽי־ט֤וֹב יְהוָה֙ כִּֽי־לְעוֹלָ֣ם חַסְדּ֔וֹ because good is Yhwh, yes forever is his loyalty,"

מְבִאִ֥ים תּוֹדָ֖ה בֵּ֣ית יְהוָ֑ה while they bring a thank-offering in the house of Yhwh.

כִּֽי־אָשִׁ֧יב אֶת־שְׁבוּת־הָאָ֛רֶץ כְּבָרִאשֹׁנָ֖ה אָמַ֥ר יְהוָֽה׃ "Indeed, I will restore the fortune of the land it was at first,"says Yhwh.

These words appear in abbreviated form in Psalms 106, 107, 118 and 136. Psalm 107:2 encourages the "redeemed of Yhwh" (גאולי יהוה) to say (יאמרו) these words. What Yhwh promised in Jeremiah 33, transpired in Psalm 107 (Kirkpatrick 1921:639).

Psalm 107 shares several general themes with Isaiah 40-66, notably the notion of Yhwh as redeemer (גאל, 107:2-3; Isa. 41:14; 43:1, 14; 44:6, 22, 23, 24; 47:4; 48:17, 20; 49:7, 26; 51:10; 52:3, 9; 54:5, 8; 59:3, 20; 60:16; 62:12; 63:3, 9, 16) and of Yhwh preparing a way for the redeemed through the desert (107:4-7; Isa. 40:3-4; 42:16; 43:19-21; 48:17). Yhwh delivers those who are imprisoned (107:10-16; Isa. 42:7, 22; 45:2; 49:9-12) and heals the afflicted who are then called upon to sacrifice thank-offerings (107:17-22; Isa. 51:12; 53:10-12; 54:10). He controls the sea as symbol of chaos and grants salvation (107:23-30; Isa. 43:16; 50:2; 51:10, 11, 15; 54:11). Yhwh dries up fertile land (107:33-34; Isa. 44:27; 50:2), but also turns the desert into fertile land (107:35-36; Isa. 41:17-18; 43:19-21; 44:3). תהו "wasteland" occurs but once in the Psalter (107:40). In Isaiah 40-66, the nations and their gods are described several times as תהו (40:17, 23; 41:29; 44:9), while Israel is not destined for תהו, but to enjoy the produce of a habitable land (45:18-19). Psalm 107 can be read in the context of the return from exile and the restoration of the post-exilic community (Stone 2013:44-45). Three specific examples suggest that Psalm 107 is dependent on material in Isaiah 40-66.

First, Isaiah 62:12 and Psalm 107:2 are the only instances in the Hebrew Bible where people who experienced Yhwh's salvific intervention are referred to as "the redeemed of Yhwh" (גאולי יהוה). In Isaiah, it occurs in the context of hope for the future restoration of Jerusalem and, in the psalm, in the context of already experienced redemption (Kartje 2014:147; Tucker 2014:60; Bremer 2016:388).

Secondly, the expression ממזרח וממערב מצפון ומים "from east and from west, from north and from sea" occurs only in Psalm 107:3 and Isaiah 49:12. In Isaiah, the exiles are gathered from the ends of the earth, delivered from prison (לאסורים, 49:9; see Ps. 107:10), darkness (בחשך, 49:9; see Ps. 107:10), and hunger and thirst (לא ירעבו ולא יצמאו, 49:10; see Ps. 107:5). Yhwh leads them (ינהגם) and brings them to fountains of water (,ועל־מבועי מים ינהלם, 49:10; see Ps. 107:30). Hence, the entire universe is called upon to praise Yhwh for his compassion upon his afflicted (ועניו, 49:13; see Ps. 107:10, 41). What is promised in Isaiah has already transpired in Psalm 107 (Tucker 2014:62).

Thirdly, an almost exact parallel exists between Psalm 107:16 and Isaiah 45:2. Isaiah 45:1-6 is a divine promise that Yhwh will enable Cyrus to subjugate nations and conquer cities, in order that the Judean exiles might be delivered. In the process, Yhwh will break down gates of bronze דלתות נחושה אשבר), 45:2c; Ps. 107:16a) and cut through bars of iron (,ובריחי ברזל אגדע, 45:2d; Ps. 107:16b). What is promised to Cyrus in Isaiah 45 becomes a universal attribute of Yhwh in Psalm 107 (Tucker 2014:64).

In Isaiah 40-66, the royal oracles

reflect perhaps the earliest attempt in the Hebrew Bible to blend Persian imperial ideology . with that of Judean royal ideology (Tucker 2014:55).

In Psalms 107-150, "the psalmists provide a thoroughly negative assessment of political power in toto" (Tucker 2014:58). Psalm 107 utilises the language of Isaiah 40-66 to introduce Book V of the Psalter

metaphorically by associating empires and powers with places of chaos and destruction, but, nevertheless, places that are not beyond the חֶסדֶ of Yahweh (Tucker 2014:62).

Psalm 107 also shows an affinity for texts influenced by wisdom epistemology. This is particularly apparent in sub-stanza 2.4 (vv. 23-32) and stanzas 3 and 4 (vv. 33-41 and 42-43). In sub-stanza 2.4 (vv. 23-32), Psalm 107 shares with the non-seafaring Israelite culture the view that "those going down to sea upon ships" (v. 23) witness Yhwh's "wonderful deeds" (ונפלאותיו, v. 24) in the deep. In Proverbs 30:18-19, the wisdom teacher expresses his astonishment (המה נפלאו ממנ "these things are too wonderful for me") about דרך־אניה בלב־ים "the way of a ship in the midst of the sea" (see Ps. 107:23-24). Stanza 3 (vv. 33-41) shares with stanza 2 (vv. 4-32) the prominent theme in wisdom literature of Yhwh's active role in the reversal of fortunes. However, it deviates from stanza 2's narrative style to "offer a timeless reflection upon Yhwh's חסד" (Kartje 2014:146).

The notion of wisdom's educational value in Psalm 107:42-43 (see Prov. 9:4, 16; 10:17; 13:18; 15:5) displays general points of contact between the psalm and the wisdom corpus. Two phenomena, however, indicate the presence of a more pronounced and nuanced wisdom epistemology. First, in the closing strophe of stanza 3 (vv. 40-41) and in stanza 4 (vv. 42-43), there is a clear contrast between an in-group and an out-group, reminiscent of the צדיק־רשע opposing pair in the Hebrew Bible's wisdom

corpus (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:101; Tucker 2014:66). Yhwh pours contempt on the "nobles" (נדבים, 107:40), who are relegated to perpetual desert wandering (see vv. 4-5). By contrast, he lifts "a poor person" (אביון) "from affliction" (מעוני, 107:41) and grants them prosperity. It provides joy to "righteous people" (ישרים) and brings an end to all injustice (,וכל־עולה, 107:42). In these references, Bremer (2016:390-391) detects the growing social stratification in Yehud in the late (post-400 bce) Persian period. The Persian yoke upon Yehud became harsher and conflict arose between the Judean elite in favour of Persian hegemony (see נדבים in v. 40; Tucker 2014:66) and members of priestly groups (Levites), who were marginalised and identified themselves with the "poor" (אביון in v. 41). The close connection between the fate of the נדבים (v. 40) and the desert-wanderers in sub-strophe 2.1 (v. 4) indicates that the experienced salvation, upon which the call to thanksgiving rests (v. 1), is not perpetual, nor unconditional. The נדבים "appear to be held responsible for the disaster of the exile" (Tucker 2014:66). Salvation is reserved for those who identify with the plight of the אביון and live as ישרים in complete dependence upon Yhwh.

Secondly, Psalm 107:43 is a typical wisdom exhortation comparable to the closing verse of the book of Hosea (Hos. 14:10). The exhortations share the noun חכם "wise" and the verb בין "to understand". Hosea 14:10 adds that contemplating "wisdom" reveals that "the ways of Yhwh are straight" (כי־ישרים דרכי יהוה; see Ps. 107:42) and that the act of contemplation also distinguishes the "righteous" (צדיקים) from the "transgressors" (פשעים; see Ps. 107:42). These similar closing lines are indicative of the growing "sapientalisation" of the Hebrew Bible in the post-exilic period (Roffey 1997:62). In Hosea, the closing admonition is a redactional addition actualising the message of the pre-exilic prophet in new socio-historical circumstances, urging post-exilic Israel to take a lesson for right living from her past sinful behaviour and adverse experiences. In Psalm 107:4243, the admonition is part of a deliberate composition exhorting the post-exilic community to thank Yhwh constantly for the already experienced, but yet incomplete (see Pss. 126; 137) restoration of Israel and the nations (Sheppard 1980:129-136; Stone 2013:41).

Psalm 107's bridging function is enhanced by the fact that it influenced other texts, notably in the "pessimistic" application of phrases in the poem's closing lines in the book of Job and in subtle allusions to the storm-at-sea images (vv. 23-32) in the book of Jonah. Three parallels with Job are noteworthy. First, the phrase חשך וצלמות "darkness and deep gloom" (107:10, 14) occurs elsewhere only in Job 10:21. Secondly, Job 12:21a quotes Psalm 107:40a, and Job 12:24b quotes Psalm 107:40b. Thirdly, Job 5:16b alludes to Psalm 107:42b, and Job 22:19a to Psalm 107:42a. Some interpret these parallels as an indication that Psalm 107 is dependent upon Job (Beyerlin 1979:13-14). A more nuanced approach suggests that Psalm 107 served as source text for the parallels in Job (Clines 1989:287; Kynes 2012:80-97) and that they are significantly reinterpreted in Job. In Psalm 107:10-16, those in חשך וצלמות are "brought out" (יוציאם, v. 14) by Yhwh, while that possibility does not exist in Job. The Job passages expand, qualify, and reinterpret Psalm 107:40 and 42. Job 12 contains a speech by Job where he argues that Yhwh acts arbitrarily when he reverses fortunes. Psalm 107 displays an "optimistic depiction of divine deliverance", while Job "challenges the norm" (Kynes 2012:96). In Job 5:16 and 22:19, Eliphaz uses Psalm 107:42 as "proof text" to reprimand Job for his pessimistic views and to support the optimistic depiction of divine deliverance (Kynes 2012:96-97). Psalm 107 highlights the positive possibilities of Yhwh's providence, while Job exploits its dark side.

Psalm 107:23-32 contains a general description of a storm at sea and its effect on עשי מלאכה במים רבים "those doing work upon mighty waters" (v. 23b, see מה־מלאכתך, Jonah 1:8). Many of these general images find specific application in the book of Jonah's narrative about a recalcitrant Israelite prophet (Kirkpatrick 1921:643). In both contexts, characters "go down" (ירד, Ps. 107:23; Jonah 1:3, 5; 2:1) to the "sea" (Ps. 107:23; Jonah 1:4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 15; 2:4) in "ships" (אניה, Ps. 107:23; Jonah 1:3, 4, 5). A "wind" (רוח, Ps. 107:25; Jonah 1:4) whips up a "storm" (סערה, Ps. 107:25; -po, Jonah 1:4, 12, 13) that traps the sailors in an "evil" plight (רעה, Ps. 107:26; Jonah 1:7, 8). When they "cry out" for help (צעק, Ps. 107:28; זעק, Jonah 1:5), Yhwh "stills" the storm (עמד, Ps. 107:25; Jonah 1:15). From the intestines of the big fish (Jonah 2:1), the prophet prays, because Yhwh cast him in the "deep" (מצולה, Ps. 107:24; Jonah 2:4) where "waves" threatened to overwhelm him (גלים, Ps. 107:25, 27; Jonah 2:4), "waters" encompassed him (גלים, Ps. 107:23; Jonah 2:6), and the "primeval waters" engulfed him (מים, Ps. 107:26; Jonah 2:6). These are "rich textual connections". It is conceivable that "Jonah is a figure of Israel in exile" (Stone 2013:46). As the closing verses of the next book in the Book of the Twelve (Mic. 7:18-20) suggest (in words strongly resembling Jonah 2:4), this Israel will experience that Yhwh "casts"(שלך, Mic. 7:19; see Jonah 2:4) not them, but their sins, "in the depths" (במצלות, Mic. 7:17; see מצולה, Jonah 2:4) (Stone 2013:47).

6. READING PSALM 107 AS A SPATIAL JOURNEY

The intertextual reading suggests that Psalm 107 serves as bridge between the desperation of exile and the hopes of the restored post-exilic community. A spatial reading confirms this bridging function. The experiences of the post-exilic community become a continuous and transforming journey between desperation and adoration. The firstspace and secondspace realities of the authors/redactors of Book V of the Psalter are decidedly negative. Their firstspace reality is that of a marginalised, small, exploited group in a vast and all-powerful Persian empire. Their secondspace context is the prevailing Persian ideology of a benevolent, universal dictatorship (Tucker 2014:26-40). Psalm 107 introduces Book V, by focusing on the world at large and on Yhwh's salvific intervention in the universe as the only benevolent, universal king (Tucker 2014:68).

Psalm 107 never mentions Israel by name, nor does it contain any specific reference to Jerusalem, Zion, or the temple (Jarick 1997:283).29Yhwh's salvific acts are directed לבני אדם "towards humankind" (vv. 8, 15, 21, 31) and aimed at them finding עיר מושב "a habitable city" (vv. 4, 7, 36) and מחוז חפצם "a place of their desire" (v. 30). Psalm 107 confronts its first-and secondspace realities and creates a world of words that transforms this world into another, indeed an other world, a world directed by חסדי יהוה "Yhwh's loyal deeds" (v. 43). Intertextual relations leave little doubt

that the house of the Lord is the implied setting for the thanksgiving, and it is equally clear that the deliverance depicted in all four stanzas is deliverance from death (Jarick 1997:283).

Yet, in the poet's spatial imagination, Yhwh's power extends beyond the uniquely Israelite to include the entire universe. In his world of words, Psalm 107 bridges the divide between Israel and the nations.

This world of words opens avenues for new thirdspatial applications in the poet's spatial imagination. Psalm 107:1 and 43 acts as key to unlock this imagination. The poet departs from the חסד יהוה (v. 1) and the multiple manifestations of this חסד in nature and history (vv. 4-32; 33-41). He can, therefore, conclude his poem with reference to the חסדי יהוה (v. 43). Between these two bookends, Psalm 107 contains a call for the thankful contemplation of Yhwh's numerous deeds of salvation experienced by גאולי יהוה "the redeemed of Yhwh" (v. 2). As the link with Isaiah 62:12 suggests, it alludes to those redeemed from the Exile (Bremer 2016:388), but as the poem's deliberate "vagueness" implies, Yhwh's loyal love is directed towards Israel as a collective, towards individual members of his people, and towards humanity (לבני אדם, vv. 8, 15, 21, 31), in general. Everybody can confidently call upon him for help in present circumstances and build his/her hope for the (eschatological) future upon this foundation.

The central conceptual metaphor permeating the entire poem is the notion of Life is a Journey30 (Kartje 2014:157). The journey is characterised by the already and the not yet, by Yhwh's absolute power to turn fortunes from negative to positive and, conversely, from positive to negative (vv. 3341). The wise would contemplate this (v. 43), in order to make life's journey a meaningful exercise with a desirable outcome (Kartje 2014:138-164).

As verses 2-3 suggest, in the poet's spatial imagination he is at the centre. The exhortation to thanksgiving in verse 1 is given from the perspective of already experienced salvation and an already arrived-at destination (Weber 2003:206). It becomes the confession of the already redeemed (גאולי יהוה, v. 2) gathered (קבץ) from the dangerous horizontal and vertical extremities of the universe (v. 3; Bremer 2016:388). The redeemed already experienced the transforming spatial journey between desperation and adoration. They contemplate the חסדי יהוה (v. 43) from their at-the-centre perspective!

The suggestion of spatial movement and arrival at a destination deserves special recognition. In sub-stanza 2.1 (vv. 4-9), the גאולי יהוה of stanza 1 (v. 2) is depicted as initially staggering in the wilderness on a desolate road, unable to find a habitable city (v. 4). Echoes of Israel's desert wandering at the time of the Exodus, and similarly of their state of desolation during the Exile are impossible to ignore. However, upon their cry for help (v. 6), Yhwh transformed their aimless wasteland wandering into a purposeful journey. He led them on a straight road to a habitable city (v. 7). They have already reached the desired at-the-centre destination. It is impossible not to regard the allusion to a habitable city as a veiled reference to Jerusalem, the centre of Israel's spatial universe. This stanza suggests a horizontal journey from far to near, from off-centre to at the centre.

The following two sub-stanzas (2.2, vv. 10-16; 2.3, vv. 17-22) contain four important spatial motifs. First, they emphasise the notion of an aimless journey, of people stumbling about without any helper (v. 12), of aimless travelling causing the travellers to arrive at the ends of the earth - literally at death's door (v. 18). A more off-centre location can hardly be imagined!

Secondly, both sub-stanzas suggest that the people's predicament is the result of their own wrongdoing. They rebelled against the words of God (v. 11) and were suffering affliction because of their iniquities (v. 17). There are clear echoes of prophetic warnings to Israel of dire consequences, should they not heed Yhwh's warnings against their apostasy and stubbornness.

Thirdly, upon the people's call for help in their adversity, Yhwh intervenes by actions suggesting spatial movement. He brought them from darkness and deep gloom (v. 14), saved them from their distress (v. 19), sent forth his word and healed them (v. 20), and rescued them from their graves (v. 20). In this instance, movement is suggested on the vertical sphere, from the depths of the netherworld to the dizzying heights of Yhwh's salvific presence, from the extremes of being off-centre to the joy of being at the centre.

Fourthly, echoes of Jerusalem and thanksgiving ceremonies in the temple are unmistakeably present. Those who experienced Yhwh's transforming intervention should give thanks to Yhwh for his loyalty (vv. 15, 21), and the thanksgiving should find specific expression in thank-offerings (v. 22) and the proclaiming of Yhwh's transforming works with shouts of joy (v. 22).

Significantly, in sub-stanza 2.4 (vv. 23-32), a dangerous and life-threatening journey upon the chaotic waters of the sea is described in vivid detail. People experience the works of Yhwh and his wonderful deeds (v. 24) when they are in the gravest danger. The omnipotence of Yhwh is revealed in the life-threatening storm. He raises the tempest by simply speaking (v. 25) and renders human wisdom useless (v. 27). Yet, he stilled the storm to a whisper (v. 29a) and guided the people to their desired place of calm and safety (v. 30).

Stanza 3 (vv. 33-41) again emphasises the omnipotent transforming power of Yhwh. He turns rivers into a desert (v. 33), and - conversely - a desert into pools of water (v. 35). He brings the hungry there and enables them to establish a habitable city (v. 36), where they can flourish (vv. 3738), but Yhwh's omnipotence also implies that he can reverse the situation. They can be decreased and humbled by oppression, calamity, and sorrow (v. 39). This should act as a warning to the nobles (v. 40). They can again be dispersed to wander in a wasteland without a road (v. 40). The poor, however, can expect to be uplifted and to thrive (v. 41).

In stanza 4 (vv. 42-43), the admonition to pay close attention and become wise turns all references to space in the poem into "focal space" intended to change behaviour. It serves as a commentary on, and application of Yhwh's חסד and salvific acts described earlier in the poem. It is a

summons for the wise . to reflect upon the profound dialectic of God's grace and steadfast love (חֶסדֶ) extolled in the hymn. In this way, the hymn depicts the unresolved tensions between wrath and grace, which precipitate a final wisdom evaluation and an invitation to seek further understanding (Sheppard 1980:131-132).

Life at the centre implies to be aware of the חסדי יהוה and of his all-powerful ability to reverse fortunes. Only he can bring the אביון "poor" (v. 41) אל־מחוז חפצם "to the place of their desire" (v. 30). This stanza transforms the poem into

a psalm of instruction based on thanksgiving: beginning with our memories of redemption, inviting a response of thanksgiving and finally moving towards reflection on the nature of God's steadfast love (Roffey 1997:74).

The poet of Psalm 107, indeed the authors/redactors of Book V, resisted Achaemenid imperial ideology. Yhwh "usurps" the universal powers of the Achaemenid king and the Persian gods - only Yhwh can turn rivers into a desert and flowing waters into thirsty ground (107:33). Israel can attest to collective and individual experiences of unbearable distress and unexpected salvation when they called for help (107:4-32; 33-41). Hope for the future does not reside in the perceived benevolent Persian hegemony, but in the often experienced and ever-present חסדי יהוה (107:1, 43).

Yhwh's people were (and often are) dispersed to the extremities of the world, in grave danger. They indeed experienced (and constantly experience) horrible, life-threatening circumstances. Their lived experience was (and is) negative to the extreme. Lost in the wilderness, locked in a dark dungeon, abandoned at death's door, exposed to the powers of chaos, they called for help and Yhwh saved them! God is the ultimate agent of change, the one who reverses fortunes. However, this goes both ways -he changes the negative to positive and the positive to negative. It is cause for careful reflection. Redemption elicits response and responsibility. The upright, those who experienced Yhwh's deeds of loyal love, should live life's journey with thanksgiving and public devotion.

7. CONCLUSION

On the levels of literary composition, redactional placement, and narrative representations of place and space, Psalm 107 bridges the divide between desperation and adoration. The opening verses (vv. 1-3) hark back to Psalms 104-106 and the closing verses, notably the contrast between various social groups in verses 40-41 and 42-43, point forward to the remainder of Book V. An intertextual and spatial reading reveals that Psalm 107 reminds the post-exilic community - at the same time -of their past deliverance and of a destination reached (see עיר מושב, vv. 4, 7, 36; מחוזחפצם, v. 30), and of a yet to be arrived at final destination of the universal adoration of Yhwh as the only recognised king. The אביון (v. 41) and the ישרים (v. 42) are engaged in a constant journey between desperation and adoration. Psalm 107 is a bridge on the often-travelled road between exile and restoration. The poem builds upon the experience of Yhwh's acts of loyalty (חסדי יהוה) in the past. It reminds the post-exilic community to call constantly upon Yhwh in their present plights. It provides them with the courage to live life confidently on their journey towards their future final destination. The closing wisdom admonition makes the חסדי יהוה an ever-newly experienced reality in the lived experience of the "poor" for all times. Yhwh's acts of loyal love are "not limited by space but extend throughout the world" (Jarick 1997:286).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, L.C. 1983. Psalms 101-150. Waco, TX: Word Books. WBC 21. [ Links ]

Ballhorn, E. 2004. Zum Telos des Psalters: Der Textzusammenhang des Vierten und Fünften Psalmenbuches (Ps 90-150). Berlin: Philo. BBB 138. [ Links ]

Berlejung, A. 2006. Weltbild/Kosmologie. In: A. Berlejung & C. Frevel (Hrsg.), Handbuch theologischer Grundbegriffe zum alten und neuen Testament (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft), pp. 65-72. [ Links ]

Berquist, J.L. 2002. Critical spatiality and the construction of the ancient world. In: D.M. Gunnand & P.M. McNutt (eds), "Imagining" biblical worlds. Studies in spatial, social and historical constructs in honor of James W. Flanagan (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, JSOTSup 359), pp. 14-29. [ Links ]

Beyerlin, W. 1979. Werden und Wesen des 107. Psalms. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. BZAW 153. [ Links ]

Black, J., George, A. & Postgate, N. (Eds) 2000. A concise dictionary of Akkadian. Second corrected printing. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. SANTAG 5. [ Links ]

Booij, T. 1994. Psalmen Deel III (81-110). Nijkerk: Callenbach. POT. [ Links ]

Bremer, J. 2016. Wo Gott sich auf die Armen einlässt: Der sozio-ökonomische Hintergrund der achämenidischen Provinz Yahüd und seine Implikationen für die Armentheologie des Psalters. Bonn: Bonn University Press. BBB 174. [ Links ]

Briggs, CA. & Briggs, E.G. 1907. A critical and exegetical commentary on the Book of Psalms. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. ICC. [ Links ]

Chatman, s.B. 1978. Story and discourse: Narrative structure in fiction and film. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [ Links ]

Clines, D.J. 1989. Job 1-20. Dallas, TX: Word Books. WBC 17. [ Links ]

Crüsemann, F. 1969. Studien zur Formgeschichte von Hymnus und Danklied in Israel. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. WMANT 32. [ Links ]

deClaissé-Walford, N. 2004. Introduction to the Psalms: A song from Ancient Israel. Nashville, TN: Chalice. [ Links ]

Deissler, A. 1979. Die Psalmen. Düsseldorf: Patmos. Die Welt der Bibel. [ Links ]

Deist, F.E. 1978. Towards the text of the Old Testament. Translated by W.K. Winckler. Pretoria: D.R. Church Booksellers. [ Links ]

Fishbane, M. 1988. Biblical interpretation in Ancient Israel. Oxford: Clarendon. [ Links ]

Genette, G. 1980. Narrative discourse: An essay in method. Translated by J.E. Levin. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Goulder, M.D. 1998. The psalms of the return (Book V, Psalms 107-150): Studies in the Psalter, IV. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. JSOTSup 258. [ Links ]

Gunkel, H. 1986. Die Psalmen. 6. Aufl. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. HKAT II/2. [ Links ]

Horowitz, W. 1998. Mesopotamian cosmic geography. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. Mesopotamian Civilizations 8. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F.-L. & Zenger, F. 2011. Psalms 3: A commentary on Psalms 101-150. Translated by L.M. Maloney. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. Hermeneia. [ Links ]

Houtman, C. 1993. Der Himmel im Alten Testament. Leiden: Brill. OTS 30. [ Links ]

Janowski, B. 2001. Das biblische Weltbild. Eine methodologische skizze. In: B. Janowski & B. Ego (Hrsg.), Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck), pp. 3-26. [ Links ]

Janowski, B. 2002. Die heilige Wohnung des Höchsten. Kosmologische Implikationen der Jerusalemer Tempeltheologie. In: O. Keel & E. Zenger (Hrsg.), Gottesstadt und Gottesgarten. Zu Geschichte und Theologie des Jerusalemer Tempels (Freiburg: Herder, Quaestiones Disputatae 91), pp. 24-68. [ Links ]

Jarick, J. 1997. The four corners of Psalm 107. Catholic Biblical Quarterly 59:270-287. [ Links ]

Kartje, J. 2014. Wisdom epistemology in the Psalter: A study of Psalms 1, 73, 90, and 107.Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. BZAW 472. [ Links ]

Kirkpatrick, A.F. 1921. The Book of Psalms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kratz, R.G. 1996. Die Tora Davids: Psalm 1 und die doxologische Fünfteilung des Psalters. Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 93(1):1-34. [ Links ]

Kraus, H.-J. 1989. Psalms 60-150. Translated by H.C. Oswald. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg. Continental Commentaries. [ Links ]

Krüger, A. 2001. Himmel - Erde - Unterwelt. Kosmologische Entwürfe in der poetischen Literatur Israels. In: B. Janowski & B. Ego (Hrsg.), Das biblische Weltbild und seine altorientalischen Kontexte (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck), pp. 65-83. [ Links ]

Kynes, W. 2012. My psalm has turned into weeping: Job's dialogue with the Psalms. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. BZAW 437. [ Links ]

Leuenberger, M. 2004. Konzeptionen des Könogtums Gottes im Psalter: Untersuchungen zu Komposition und Redaktion der theokratischen Bücher IV-V im Psalter. Zürich: TVZ. AThANT 83. [ Links ]

Lefebvre, H. 1991. The production of space. Translated by D. Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Lotman, J. 1977. The structure of the artistic text. Translated by R. Vroon. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan. Michigan Slavic Contributions 7. [ Links ]

Mejía, J. 1975. Some observations on Psalm 107. Biblical Theology Bulletin 5(1):56-66. https://doi.org/10.1177/014610797500500103 [ Links ]

Miller, G.D. 2011. Intertextuality in Old Testament scriptures. Currents in Biblical Research 9(3):283-309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476993X09359455 [ Links ]

Prinsloo, G.T.M. 2005. The role of space in the – (Psalms 120-134). Biblica 86:457-77. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, G.T.M. 2006. Se'öl " Yerüsãlayim ! Sãmayim: Spatial orientation in the Egyptian Hallel (Psalms 113-118). Old Testament Essays 19(2):739-760. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, G.T.M. 2013a. From watchtower to holy temple: Reading the Book of Habakkuk as a spatial journey. In: M.K. George (ed.), Constructions of Space IV: Further developments in examining social space in Ancient Israel (London: Bloomsbury T. & T. Clark, LHBOTS 569), pp. 132-154. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, G.T.M. 2013b. Place, space and identity in the ancient Mediterranean world: Theory and practice with reference to the Book of Jonah. In: G.T.M. Prinsloo & C.M. Maier (eds), Constructions of Space V: Place, space and identity in the Ancient Mediterranean world (London: Bloomsbury T. & T. Clark, LHBOTS 576), pp. 3-25. [ Links ]

Rimmon-Kenan, S. 2002. Narrative fiction. Contemporary poetics. Second edition. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Ro, J.U. 2002. Die sogenannte "Armenfrommigkeit" im nachexilischen Israel. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. BZAW 322. [ Links ]

Roffey, J.W. 1997. Beyond reality: Poetic discourse and Psalm 107. In: E.E. Carpenter (ed.), A biblical itinerary. In search of method, form and content. Essays in honor of George W. Coats (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, JSOTSup 240), pp. 60-76. [ Links ]

Seybold, K. 1996. Die Psalmen. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr. HAT I/15. [ Links ]

Sheppard, G.T. 1980. Wisdom as a hermeneutical construct: A study in the sapientalizing of the Old Testament. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. BZAW 151. [ Links ]

Soja, E.W. 1996. Thirdspace. Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Oxford: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Stone, T.J. 2013. Following the Church Fathers: An intertextual path from Psalm 107 to Isaiah, Jonah, and Matthew 8:23-27. Journal of Theological Interpretation 7(1):37-55. [ Links ]

Thompson, L.L. 1978. Introducing biblical literature: A more fantastic country. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Tov, E. 2001. Textual criticism of the Hebrew Bible. Second edition. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Tuan, Y. 1977. Space and place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [ Links ]

Tucker, W.D. 2014. Constructing and deconstructing power in Psalms 107-150. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. SBLAIL 19. [ Links ]

Van der Ploeg, J.P.M. 1974. Psalmen Deel II: Psalm 76 t/m 150. Roermond: Romen. BOT. [ Links ]

Van Eck, E. 1995. Galilee and Jerusalem in Mark's story of Jesus. A narratological and social scientific reading. Pretoria: Promedia. HTS Supplementum 7. [ Links ]

Weber, B. 2003. Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 bis 150. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer. [ Links ]

Westermann, O. 1961. Das Loben Gottes in den Psalmen. 2. Aufl. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [ Links ]

Wyatt, N. 2001. Space and time in the religious life of the Near East. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Zenger, E. 1997. Der jüdischen Psalter - ein anti-imperiales Buch? In: R. Albertz (Hg.), Religion und Gesellschaft: Studien zu ihrer Wechselbeziehung in den Kulturen des Antiken Vorderen Orients (Münster: Ugarit Verlag, AOAT 248), pp. 95-108. [ Links ]

Zenger, E. 1998. The composition and theology of the fifth book of Psalms, Psalms 107145. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 80:77-102. [ Links ]

Date received: 20 January 2021

Date accepted: 07 June 2021

Date published: 10 December 2021

1 Ballhorn (2004:127-146) regards Psalms 105-107 as a triptych. The doxology In Psalm 106:48 Interrupts the original unity between the three poems and transforms Psalm 107 into the opening poem of Book V. Leuenberger (2004:186) regards Psalm 107 as a Fortschreibung of Psalms 105106, deliberately composed as the opening poem of Book V.

2 Emphasis original; see §2.

3 My emphasis, see §2.

4 For the distinction between reader-oriented and author-intended approaches to intertextuality, see Miller (2011:283-309) and Kynes (2012:17-60). For author-intended intertextuality, Kynes (2012:59) provides useful criteria for determining the direction of influence.

5 For narrative theory, see Genette (1980:25-27); Rimmon-Kenan (2002:1-5).

6 For critical spatiality, see Berquist (2002:14-29). Critical spatiality can be defined as "those theories that self-consciously attempt to move beyond modernist, mechanistic, essentialist understandings of space. Critical spatiality understands all aspects of space to be human constructions that are socially contested" (Berquist 2002:15)

7 See Lefebvre (1991:38-39). Lefebvre calls physical space "perceived space", i.e. nature, cosmos, place. Mental space is "conceived space", i.e. representations of space or conceptualised space. Social space is "lived space", i.e. spaces of representation, space as experienced.

8 For ancient Near Eastern world view(s), see Berlejung (2006:65-72). Janowski (2001:3-26) warns against over-simplified attempts to reconstruct the biblical world view. Views on ancient Near Eastern cosmology developed and changed over time and no single, systematic description of this cosmology ever existed (Houtman 1993:283).

9 See also Krüger (2001:65-83).

10 Spatial constraints prohibit a detailed exegetical discussion of Psalm 107. For brief reviews of the poem's research history, see Beyerlin (1979:1-6) and Allen (1983:60-63). On form-critical grounds, Westermann (1961:76) regards the poem as a literary unit combining a "berichtende Lobpsalm des Einzelnen" (vv. 1-32) and a "beschreibende Lobpsalm" (vv. 33-43; see also Pss. 18, 118, 138). Others regard Psalm 107 as an anthology from different Sitzen im Leben. Verses 1, 4-32 constitute a pre-exilic liturgy of thanksgiving performed during a ceremony in the sanctuary (Gunkel 1986:470; Crüsemann 1969:73; Beyerlin 1979:8-9; Kraus 1989:326327; Seybold 1996:427). Verses 2-3 are a post-exilic insertion linking Psalms 106 and 107. A hymn commemorating Yhwh's power over nature and history (vv. 33-43) was added in late post-exilic times. It contains numerous wisdom motifs and does not have a cultic Sitz im Leben (Gunkel 1986:472-473; Crüsemann 1969:73-74; Beyerlin 1979:10-11; Kraus 1989:331; Seybold 1996:427-428). According to Roffey (1997:66), Psalm 107's poetic language indicates that it should "be read symbolically, with only a second-order reference to reality". It has a specific Sitz in der Literatur as the deliberately composed opening psalm of Book V (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:101-102).

11 It is not immediately apparent what the "redeemed of Yhwh" should say (Allen 1983:58). Some regard verses 2-3 as a later addition (Briggs & Briggs 1907:358; Beyerlin 1979:21-26). If יאמר (v. 2a) is interpreted as a jussive, the preceding call to praise becomes an obligation for everyone who experienced Yhwh's acts of salvation (Booij 1994:267).

12 The pairing of מיד and צר suggests that "enemy" is an appropriate translation for צר (Gen. 14:20; see צרר II "treat with hostility"). The construction יד־צר thus refers to "historical-political enemies" (Tucker 2014:60; see Beyerlin 1979:69). In verses 6, 13, 19, and 28, צר refers to "distress" (צרר I "wrap up, tie up, lock up") (Allen 1983:58; Kartje 2014:142). To retain the Hebrew wordplay, I translated -s in verse 2 with "adversary" and in versesand 6, 13, 19, 28 with "adversity".

13 Some emend מים "from sea" to מימין "from the south" to retain the four cardinal compass points (Deissler 1979:427; Kraus 1989:325). However, the same expression occurs in Isaiah 49:12. צפון "north" often serves as "historical-mythical metaphor for evil and chaos" (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:104; see Jer. 50:41-42; Ezek. 38:6, 15; 39:2). Similarly, ים serves as symbol for powers of chaos (Jarick 1997:279-280). ממזרח ומערב represent the horizontal extremities of the biblical world view, while מצפון ומים point to the vertical extremities (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:104). ים anticipates the extended narrative of the plight of seafarers in verses 23-32 (Jarick 1997:272-273; Kartje 2014:143).

14 Literally "on a wilderness of road". For ישימון "wilderness", see Numbers 21:20; 23:28; 1 Samuel 23:19, 24; 26:1, 3. It often occurs in conjunction with the synonym מדבר, suggesting the exodus from Egypt (Deut. 32:10; Pss. 68:7; 78:40; 106:14) or Israel's return from exile (Isa. 43:19, 20). Some commentators ignore the atnãh with דרך and read the word with the next colon, i.e. "a way (to) a city for dwelling they did not find" (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:97; Kartje 2014:143).

15 Some argue that אולים "fools" does not suit the context and emend it to חולים "sick people" (Briggs & Briggs 1907:360) or אמללים "weak people" (Kraus 1989:325). Kartje (2014:144) argues against the emendation. אויל does not necessarily refer to intellectual inability, but to moral corruption. This interpretation fits well with the exhortation in verse 43 that a חכם should pay careful attention to חסדי יהוה "Yhwh's acts of loyalty".

16 Masoretic manuscripts mark some verses by so-called inverted nüním (Tov 2001:54-55). Codex Leningradensis "brackets" verses 21-26, 40 and Codex Aleppo verses 23-28, 40 in this fashion. In Numbers 10:35-36, inverted nüním supposedly mark the passage as "misplaced". The function of the inverted nüním in Psalm 107 is not clear (Deist 1978:59).

17 מחוז is a hapaxlegomenon usually translated by "harbour". I take the concentric pattern between sub-stanzas 2.1 (vv. 4-9) and 2.4 (vv. 23-32) into account and regard מחוז חפצם as a poetic variant for עיר מושב "habitable city" (see vv. 4b, 7b, 36b). I translate it by the neutral term "place" (see Akkadian mãhãzu "(market) city", derived from the root ahãzu "to take"; Black et al. 2000:190).

18 See Psalms 100:5; 105:1; 106:1 in Book IV and Psalms 107:1; 118:1, 29; 136:1, 2, 3, 26 in Book 5. The root ידה appears 11 times in Book I, 15 times in Book II, seven times in Book III, seven times in Book IV, and 27 times in Book V. or- in the sense of exulting Yhwh occurs three times in Book I, once in Book II, twice in Book IV, and three times in Book V. הלל in the sense of praising Yhwh occurs six times in Book I, 11 times in Book II, twice in Book III, eight times in Book IV, and 57 times in Book V. Elsewhere, the phrase occurs in Jeremiah 33:11, Ezra 3:11 and 1 Chronicles 16:34-36 (quoting Ps. 106:1, 34-36). It "signals the rebuilding of Jerusalem and the renewal of the Temple cult" (Hossfeld & Zenger 2011:103).

19 A single exception is the second person plural imperative (mn, v. 1a) at the beginning of the poem. It sets the tone for the entire poem. The "they" group should give thanks to Yhwh.

20 Suffering/distress: verses 4, 5, 12, 17, 18, 24, 26, 27, and 39; sin/transgression: verses 11, and 17; salvation/restoration: verses 6, 13, 36, 37, and 38; thanksgiving/devotion: verses 1, 2, 8, 15, 21, 22, 30, 31, 32, 42, and 43.

21 Salvation/care: verses 2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 13, 14, 16, 19, 20, 28, 30, 36, 38, and 41; punishment: verses 12, and 40; acts in nature/history: verses 25, 29, 33, and 35.

22 Weber (2003:207) indicates that ממזרח refers literally to the "rising (of the sun)" and, in this instance, symbolises the eastern desert (see vv. 4-9). מערב refers to the "setting (of the sun)" and symbolises darkness and the realm of the netherworld (see vv. 10-16). מצפון refers to the north, historically associated with attacks upon Israel (Jer. 1:13-14; 4:6-7, 15-17; 6:1, 22-23), but mythologically associated with the mountain of the gods and the location of the final battle between forces of chaos and the divine (Ezek. 38-39, see vv. 17-22). Finally, מים refers to the sea, a well-known symbol of powers of chaos (Ex. 15:8; Ps. 18:16-17; 29:3; 77:17020; 114:3, 5; 144:7, see vv. 23-32).

23 Four is a symbolic number suggesting completeness (Jarick 1997:284).

24 Goulder (1998:123) notes that Psalm 107:4-32 shows a preference for imperfect verbal forms that adds a note of ambivalence to the poem. The poem is concerned with adversity already avoided, yet still experienced.

25 Note the imperfect forms, suggesting that Yhwh is constantly at work in the world in this way.

26 The transition from nature to history is suggested by a series of waw consecutive + imperfects v. 36a; בשויו, v. 36b; וננוכיו, v. 37a; ושעיו, v. 37b; םכרביו and ובריו, v. 38a; וצעמיו and וחשיו, v. 39a; םעתיו, v. 40b; בגשיו, v. 41a; םשיו, v. 41b).

27 The participle (v. 40a) amidst the series of waw consecutive + imperfects suggests this turn from historical events to ethical application.

28 נפלאות usually refers to "the great miracles God performed for the benefit of his people when he was taking them out of Egypt (Mejía 1975:58; see Pss. 78:4, 12; 106:7, 22).

29 This is extraordinary in a collection of poems with an intentional focus on Jerusalem, Zion, and the temple, as can be clearly noted in the two "pilgrimage" collections, Psalms 113-118 and 120-134. Zenger (1998:99-101) argues that Book V of the Psalter is ultimately post-cultic and propagates a "spiritual" pilgrimage to Zion. Psalm 107's opening exhortation to thanksgiving (v. 1) suggests that temple imagery is present behind the scenes, but the lack of any specific mention of Jerusalem/ Zion/temple in the poem underlines its universal intent.

30 As is convention - the basis metaphor is consistently capitalised.