Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 suppl.32 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup32.21

ARTICLES

Transformation of war language in the worship of all the earth in Psalm 100

D.G. Firth

Trinity College, Bristol; Research fellow, Department Old and New Testament Studies, University of the Free State, South Africa. E-mail: d.firth@trinitycollegebristol.ac.uk; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0347-4490

ABSTRACT

Though often read as a discrete poem, Psalm 100 is read within the context of Psalms 93-100 in this article. Such a reading helps expose how language, which had been rooted in warfare, has been transformed into the language of worship. The background in warfare is explored through intertextual links within this collection and then against the background provided by the book of Joshua as a sample text. As the conclusion to this collection within the Psalter, Psalm 100 transforms this language, so that Yahweh's kingship over all the earth is expressed not in the violence of conquest, but rather in the joyful submission of freely given worship.

Keywords: Psalms, Joshua, Intertextuality

Trefwoorde: Psalms, Josua, Intertekstualiteit

1. INTRODUCTION

Psalm 100 is one of the best known hymns in the Psalter. Despite its brevity, it has inspired numerous hymns and worship songs in contemporary Christian worship,1 while its language in various ways continues to shape the discussion about biblical patterns of worship (Hill 1993). Yet for all the ways in which this poem continues to find a welcome reception in the modern world, it is still a text that is deeply rooted in the ancient one. That rootage can be noted in how its language interacts with both the small collection, of which it is a part within the Psalter (Pss. 93-100), and other texts within the Old Testament. Although this can be explored in numerous ways, for the purposes of this short paper, this investigation is limited to the ways in which it evokes the language of warfare from Psalms 93-100 and the book of Joshua, while transforming it to apply to the act of joyful worship. Ultimately, the psalm demonstrates Yahweh's kingship over all the earth, a domain that is expressed not in the violence of conquest, but rather in the joyful submission of freely given worship. The language is liturgical (Seybold 1996:391), but it is not only liturgical.

Demonstrating this claim involves working through three main stages. First, attention is paid to Psalm 100 as a discrete poem to understand its language in its internal relationships (Prinsloo 1994a), a process that includes consideration of its text and translation. A poem's language is internally referential, so that the semantic domains assigned to terms that might otherwise be ambiguous are controlled by the immediate context in which we find it. Poems are also structured works, and attention to structure also helps reveal how its language is used. As this is not a comprehensive treatment of Psalm 100, this stage is relatively brief.

Secondly, Psalm 100 is read within its current context in the Psalter, specifically as the conclusion to Psalms 93-100. Attention to this context demonstrates important semantic and conceptual links that hold these psalms together. This stage of the process is simultaneously intra-textual and intertextual. It is intra-textual, because these poems are read as units within the Psalter; it is also intertextual, because each psalm is still a distinct poem. Thus, the links between these poems are viewed as intentional within the Psalter, while still allowing for degrees of variation, a process that allows for openness in how certain terms are understood.

Thirdly, sample texts from Joshua are read alongside Psalm 100. This is a self-consciously intertextual approach that enables readers to observe more clearly how the language found in Psalm 100 can occur in contexts in which warfare, and not worship, is central.

2. TEXT AND TRANSLATION

2.1 Text

In verse 3, read וְלֹו, following Qere and many manuscripts rather than Kethib ולְאֹ Although Kethib is the more difficult reading, and is supported by LXX, the widespread support for Qere (Aquila, Targum, Jerome) suggests that Kethib is a corruption based on a scribe mishearing the text. In addition, Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:492-493) note that the line appears to be taken from Psalm 95:6. If so, and the placement of this psalm as the conclusion to Psalms 93-100 would support this, then the fact that its reading is the same as Qere provides further support for that reading in this instance.

3. STRUCTURE

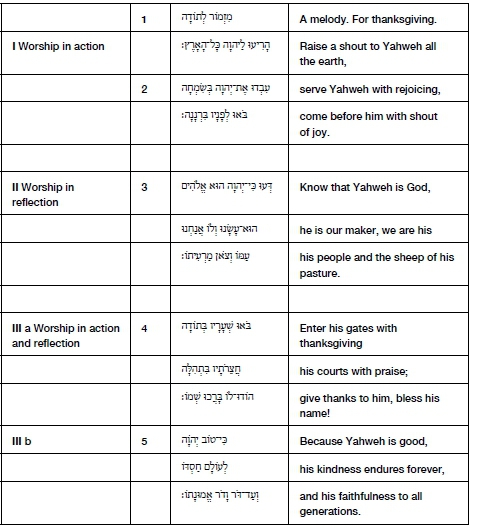

This short poem is presented in three brief stanzas with an emphasis on tricola (see Stocks 2012). After the title, the first stanza runs from verse 1b-2 and consists of a single tricolon, each part-line commencing with a plural imperative verb summoning an act in worship. Verse 3 is a second tricolon, and it also commences with a plural imperative, but the second and third part-lines both draw an implication from the imperative, which summons reflection on Yahweh's status as God. The third stanza also commences with a plural imperative, inviting an action in worship, while the third part-line contains two further imperatives, summoning an action, perhaps because the opening imperative carries its force over to the second part-line. This stanza is made up of two tricola, as is evident from the conjunction כִּי. This immediately shows that it is explaining why the various acts of worship matter. Expressed entirely in the indicative mode, it notes three aspects of Yahweh's character, the second and third of which are expressly said to endure. As the first tricolon in this stanza ended with a call to bless Yahweh's name, with the name (שֵׁם) representing his character, these qualifying statements about Yahweh relate particularly to the last part-line, though in reality they also point to the wider themes of the poem. It is also entirely appropriate that this final stanza pivots around reference to the name, given that "Yahweh" occurs three times in the first stanza and once in the second, all of which build to the declaration of his character in the closing tricolon. The structure thus initially treats worship actions and reflection separately before bringing them together in the closing stanza,2 having begun by noting that such worship is for all the earth and concluding with the note that such worship is always appropriate.3

4. PSALM 100 AND PSALMS 93-100

In elaborating on the work of Howard (1997), there is now widespread agreement that Psalm 100 closes a section in Book 4 of the Psalter (see Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:494-495; Vesco 2006:924), although Prinsloo (1991:972) already hinted at this. More importantly for the purposes of this article, along with Psalm 95 it provides a frame around Psalms 96-99 and the interchange found there between the summons to "sing a new song to Yahweh" (Psalms 96:1, 98:1) and the declaration that "Yahweh reigns" (Pss. 97:1, 99:1) (see McKelvey 2014:165-166). For the purposes of this article, it is not necessary to resolve the question of the exact sense of יְהוָה מָלָךְ beyond noting that in any interpretation it reflects an understanding of Yahweh's kingship. This language picks up the declaration at Psalm 93:1, while reference there to the holiness that befits Yahweh's house (Ps. 93:5) is echoed in the references to the gates and courts of the sanctuary in Psalm 100.4 The frame with Psalm 95 also emphasises the importance of song, a theme picked up in the two "new song" psalms. The noun translated "shout of joy" in Psalm 100 (רְנָנָה) is not common, but the cognate verb (רנן) occurs as an imperative in Psalm 98:4 and as an imperfect in Psalms 96:12 and 98:8, while the cohortative occurs in Psalm 95:1. Depending on the context, this can be translated as some form of shout or singing, meaning that the linguistic connection between these psalms is not always particularly evident in translation. Nevertheless, this forms part of the range of connections between these psalms, which have numerous other points of linguistic contact that hold them together. Although kingship is not expressly mentioned in Psalm 100, the description of the worshippers as the "sheep" of Yahweh's pasture evokes the widespread motif of the king as shepherd of his people, and this is consistent with the themes of the whole of this section, especially when one notes that the imperative clause עִבְדוּ אֶת־יְהוָה occurs only twice in the Psalter, namely in Psalms 100:2 and 2:11. Within that context, the language of kingship is prominent (McKelvey 2014:160). Yahweh's kingship over all creation is declared in Psalm 93, reaffirmed in Psalms 97 and 99, and concluded in worship in Psalm 100.

How is this reign recognised? It is important to note that the two "new song" psalms evoke important themes associated with Yahweh war in the Old Testament (see Longman 2014:341-346). Although this is more prominent in Psalm 98, Psalm 96 plays an important preparatory role in announcing Yahweh's coming not only to Israel, but also to the nations (see Beuken 1992). Of importance for the purposes of this article, the psalm specifically celebrates Yahweh's strength and glory, so that all the earth is ultimately to tremble before him (Ps. 96:7-9). Yahweh's coming to the nations is ultimately good news, but he will also judge the peoples (Ps. 96:10, 13). These themes are expressed more fully in Psalm 98, in part because of its internal poetic coherence (see Prinsloo 1994b:163), but also because the language of Yahweh having worked salvation to Israel so clearly evokes the theme of the exodus (see Longman 1984). Numerous elements in both psalms thus have their background in the language of warfare. Although the language, in this instance, is clearly expressed in terms of worship in the cult, this worship is closely associated with victory in battle.

However, although these psalms clearly reflect Israel's experience in the past, they also point to the importance of these victories for the nations. Yahweh may have defeated these nations, but the victories are also presented as a witness to the nations. Yahweh's salvation (Ps. 96:2) clearly looks back to the events of the exodus, but this is to be declared among the nations (Ps. 96:3). Likewise, the clans of the peoples (מִשְׁפְּחֹות עַמִּים) are summoned to "ascribe to Yahweh" (Ps. 96:7) recognising his strength and glory while bringing an offering to his courts (Ps. 96:8). Although this language can in part be linked to themes drawn from creation (Ps. 96:10), even this points to Yahweh's authority to judge the nations. In Psalm 96, the knowledge that Yahweh previously won the victory provides reason not only for Israel to sing a new song, but also to call the peoples to do the same. This motif is developed further in Psalm 98, where Yahweh's salvation demonstrated his righteousness before the nations, so that all the ends of the earth saw Yahweh's salvation of Israel (Ps. 98:2-3). As such, all the earth is to make a joyful noise and sing Yahweh's praises (Ps. 98:4). As with Psalm 96, Psalm 98 closes with the motif of Yahweh coming to judge the world, and especially the peoples, something he does with equity (Ps. 98:9). All this demonstrates Yahweh's reign, so that the opening declarations of both Psalms 97 and 99 have an immediate context which shows that his reign is expressed over the earth and the peoples, in particular. In Psalm 99:9, the imperative רֹומְמוּ is not addressed to Israel alone, but rather to all the peoples.

The language of Psalm 100 is then closely engaged with Psalms 93-99, with many terms shared between them. Moreover, where Psalm 99 ended with a summons to all to exalt Yahweh, even though he is Israel's God, Psalm 100 can now assume that the nations do indeed come to Yahweh's sanctuary to worship. The language of worship in this psalm also echoes the language of warfare in the preceding psalms. This connection might be enabled by the recurrence of the title מִזְמֹור from Psalm 98,5 the only other psalm in this small collection to have a title in MT.6 This title is expanded in Psalm 100 with the unique לְתֹודָה. This is commonly (and appropriately) translated as "for thanksgiving", but the noun תֹודָה strikingly occurs in Ezra 10:11, where it also involves making a confession of sin. The context also evokes Joshua's charge to Achan (Josh. 7:19), where a confession of sin is clearly intended, although in Joshua the term is also associated with giving glory to Yahweh.7 Elsewhere, in Psalms 26:7 and 42:5, the noun clearly refers to the act of giving thanks, whether in song (Neh. 12:7) or with an offering (Lev. 7:12). There is thus a semantic breadth that is difficult to represent in translation. The title could indeed suggest that the psalm is for thanksgiving, an acknowledgement of what Yahweh has done and typically expressed in song - perhaps antiphonal song, as suggested by Amzallag (2014). Or, it could be a confession of sin, of standing against Yahweh's purposes, even if worship is the most appropriate context for doing this.

The polysemous sense of תֹודָה is already evident in its only other occurrence in Psalms 93-100, namely in Psalm 95:2. This is perhaps less evident with the noun there, since the surrounding terminology is predominantly understood in terms of joyful worship, although, as shall be noted, even it has background in warfare. As becomes clear at Psalm 95:7d,8 the psalm is also a warning against sin. As such, this has the effect of asking the reader to think again about whether the act of coming before Yahweh is one of thanksgiving or confession. Likewise, when Psalm 100:4 picks up the term again, those entering Yahweh's gates with תֹודָה may be doing so either as an act of thanksgiving for the privilege of worship or as a need to confess sin. The connection made by the title to Psalm 98 also means that Psalm 100 is directly connected to a poem already noted as a victory song. All the earth was there to sing praises, but the fact that Yahweh has wrought salvation for his people also means that he has defeated his foes. Those who come with their תֹודָה might be either defeated foes or those genuinely thankful for salvation. Their תֹודָה could be a confession of sin for having resisted Yahweh or thanksgiving those for whom salvation was good news. Although the various senses of תֹודָה continue to be evident in this instance, the sense is that whatever reason there might be for someone being in the sanctuary, it remains good news.

This emphasis is evident in the cognate verb (ידה) in verse 4, where it is paired with the imperative בּרֲָכוּ, the combination having the effect of ensuring that the focus is finally on prayer.

The connections with Psalms 95 and 98 continue to be evident as one moves to the psalm proper. The poem begins by calling all the earth to "raise a shout" to Yahweh (הָרִיעוּ לַיהוָה). The verb רוע, in this instance a hiphil imperative, also occurs in these psalms, further strengthening the connections between them. It occurs in Psalm 95:1-2, as a cohortative in verse 1 and as an imperfect with cohortative meaning in verse 2. As the opening of the psalm clearly focuses on worship that responds to Yahweh as the God of salvation, it is typical to translate the verb, in this instance, as "make a joyful noise". That is, the shout offered is itself celebratory. Something similar can be mentioned about the two occurrences in Psalm 98 (verses 4 and 6), although now the verbs are both hiphil imperatives that match the forms in Psalm 100. Again, the larger context of the psalm indicates that the shout, in this instance, is joyful and is linked with the signing summoned at the poem's start. Where Psalm 98:1 might initially seem to be directed only to Israel, since they are the people for whom Yahweh has presumably won the victory, in verse 4 all the earth must make the joyful noise. The victory won by Yahweh is not only for Israel. It is also for all the earth, even as this also prepares for Yahweh's coming to all the earth. Those who cry out in worship thus anticipate Yahweh's further victories, which prepare for the time when he judges the peoples. This background is still evident in Psalm 100, but the focus is on worship as the joyful experience of all the earth.

5. PSALM 100 AND JOSHUA

Further examples can be given of the ways in which the language of Psalm 100 evokes that of Psalms 93-100. The above examples suffice for our purposes to show that the language of worship in Psalm 100 has the language of warfare in the background, and this background is already evident, to some extent, in Psalms 93-99. As is the nature of poetry, these psalms are somewhat elusive and open in their language, allowing a range of senses to be present. But the linguistic connections with the book of Joshua make the military background of much of the language a great deal clearer, even if the contexts in Joshua are also presented in a way that permits the motif of worship to remain visible.

As mentioned earlier, the presence of the noun תֹודָה in the title could evoke an allusion to Joshua 7:19 and the Achan story, an event that sits squarely in Israel's traditions of Yahweh war. However, a single noun (even if not especially common with only 32 occurrences in the Hebrew Bible) is not an especially strong connector to this story. Regarding the verb with which Psalm 100 begins, רוע, the connections are somewhat stronger. With 44 occurrences across the Hebrew Bible, it is only slightly more common. But of those, seven occur in Joshua 6, all associated with the capture of Jericho (Josh. 6:5, 10 (three times), 16, 20 (twice)). There are clear elements in this battle report that associate the battle with some form of liturgy, most notably the presence of the priests with the שׁוֹפָר; in their procession, although we might also note that the שׁוֹפָר; is also mentioned in Psalm 98:4. In Joshua 6, every stage of the battle is marked by the use of the verb רוע. The shout in Joshua 6 probably includes some element of worship, but it is primarily an act of war. The shout may be intended to invoke Yahweh, but it is primarily a war cry. This background can be traced further within the Former Prophets, such as the shout of the Philistines in Judges 15:14, or the shouts in 1 Samuel 17:20, 52, all of which show that the shout is at home in warfare. But this is already established in Joshua.

Without providing an extensive analysis of the connections with Joshua, one might also note that the verb "עבד, with which Psalm 100:2 begins, also has echoes in Joshua. In this instance, the military connections are slightly less evident in Joshua, but their context still points to this dimension. In Joshua 24, the verb occurs 13 times. Much of the time, this is in the context of discussion about which God to serve, a discussion that is important in Joshua, given the ways in which various non-Israelites have been integrated into the community (Firth 2018). Of note for Psalm 100 is the fact that the imperative, with which Joshua 24:14 ends, is identical to that opening Psalm 100:2, apart from the conjunction. Although the verb does not have a directly military connotation, the fact that it is presented immediately after the account of the military victories Yahweh has won for Israel (Josh. 24:2-13) makes it clear that it is the logical response to Yahweh as the divine warrior. This, of course, is the same situation as in Psalms 93100, where Yahweh's status as the divine warrior is stressed in the buildup to Psalm 100. That the decision to serve Yahweh is a response to him as the divine warrior is evident in the people's response to Joshua (Josh. 24:16-18). Although Joshua and the people debate this through Joshua 24, this aspect of the discussion remains central. Yahweh is the warrior who has defeated Israel's foes; therefore, the only appropriate choice is to serve him, that is, to live a life worshipping him alone. Nevertheless, a key transformation is introduced by Psalm 100 at this point, when it insists that Yahweh is to be served בּשְִׂ מחְהָ . The verb עבד occurs elsewhere with שִׂ מחְהָ only in Deuteronomy 28:47, where it refers to the curses that come upon Israel because of a failure to serve Yahweh with rejoicing. While retaining echoes of the military background, Psalm 100 has transformed it, in this instance, by declaring that Yahweh can be served with rejoicing. This is no longer the service of compulsion that might be expected after a military victory, but rather one that finds joy in worshipping Yahweh.

6. CONCLUSION

One could mention more about the relationship between Psalm 100 and Psalms 93-99 and the book of Joshua. But the purpose of this article is not to provide a comprehensive study of these connections. Rather, it aimed to show that, even though Psalm 100 is a clearly liturgical text, one that celebrates Yahweh and the possibility of all the earth coming before him in worship, in doing so it still retains echoes of the language of warfare. The breadth of these elements can also be explored through the connections with Yahweh's kingship, which are also evident in the psalm, and which would themselves also have military connotations, but that is beyond the scope of this article. As argued earlier, the language of warfare also undergoes a degree of transformation, partly because of the psalm's place at the close of this collection within the Psalter (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:497). Although the dimension of warfare is not removed, the effect is less bellicose than it might have been. The more immediate transformation of war language is that which Psalm 100 has itself introduced, so that as one moves through the psalm the element of warfare becomes less prominent, and Yahweh's goodness and faithfulness are stressed instead (McKelvey 2014:166). The opening phrases of the psalm allow the reader to understand them in the context of war, and this is something that continues through the first stanza, although the initial transformation occurs in this instance. Once the second stanza shifts its focus to Yahweh's character, a rather different dimension begins to develop, even if the motif of kingship would still allow for some military inference. As these elements are brought together in the third stanza, this is no longer possible, so that thanks and praise predominate in response to Yahweh's goodness, kindness, and faithfulness. By the end of the psalm, readers know that Yahweh does indeed reign as king and has the power to defeat foes. But the language of warfare is transformed to show that the service of Yahweh is, in fact, the way to freedom and joy. Thus, by the end of the psalm, readers understand that Yahweh's reign is best expressed in freely given worship, and this can be offered by all the earth.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amzallag, N. 2014. The meaning of todah in the title of Psalm 100. Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 126(4):535-545. [ Links ]

Beuken, W.A.M. 1992. Psalm 96: Israel en de volken. Skrif en Kerk 13(1):1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v13i1.1043 [ Links ]

deClaissé-Walford, N., Jacobson, P.A. & Laneel Tanner, B. 2014. The Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. NICOT. [ Links ]

Firth, D.G. 2018. Joshua 24 and the welcome of foreigners. Acta Theologica 38(2):70-86. https://doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v38i2.5 [ Links ]

Firth, D.G. 2020. Reading Psalm 46 in its canonical context: An initial exploration in harmonies consonant and dissonant. Bulletin for Biblical Research 30(1):22-40. https://doi.org/10.5325/bullbiblrese.30.L0022 [ Links ]

Goldingay, J. 2008. Psalms. Volume 3: Psalms 90-150. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. BCOWP. [ Links ]

Hill, A.E. 1993. Enter his courts with praise! Old Testament worship for the New Testament church. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F.L. & Zenger, E. 2005. Psalms 2: A commentary on Psalms 51-100. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Howard, D.M. Jr. 1997. The structure of Psalms 93-100. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Howard, D.M. Jr. 1999. Psalm 94 among the Kingship-of-Yhwh Psalms. Catholic Biblical Quarterly 61(4):667-685. [ Links ]

Longman, T. Ill 1984. Psalm 98: A divine warrior victory song. Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 27(3):267-274. [ Links ]

Longman, T. Ill 2014. Psalms: An introduction and commentary. Nottingham: IVP. [ Links ]

Mare, LP. 2000. Psalm 100 - Uitbundige lof oor die Godheid, goedheid en grootheid van Jahwe. Old Testament Essays 13(2):218-234. [ Links ]

McKelvey, M.G. 2014. Moses, David and the High Kingship of Yahweh: A canonical study of Book IV of the Psalter. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. GBS 55. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, W.S. 1991. Psalm 100: 'n Poëties minderwaardige en saamgeflansde teks? HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 47(4):968-982. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, W.S. 1994a. A comprehensive semiostructural exegetical approach. Old Testament Essays 7(4):78-83. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, W.S. 1994b. Psalm 98: Sing 'n nuwe lied tot lof van die Koning, Jahwe. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 50(1&2):155-168. [ Links ]

Seybold, K. 1996. Die Psalmen. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. HAT. [ Links ]

Stocks, S.P. 2012. The form and function of the tricolon in the Psalms of the Ascents: Introducing a new paradigm for Hebrew poetic line-form. Eugene, OR: Pickwick. [ Links ]

Vesco, J.-L. 2006. Le psautier de David. Traduit et commenté. Paris: Cerf. [ Links ]

Waltke, B.K. & Houston, J.M. 2019. The Psalms as Christian praise: A historical commentary. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans. [ Links ]

Watts, I. n.d. Sing to the Lord with joyful voice. [Online.] Retrieved from https://hymnary.org/text/sing_to_the_lord_with_joyful_voice. [26 August 2021]. [ Links ]

Wray Beal, Lm. 2019. The story of God Bible commentary: Joshua. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Date received: 20 October 2020

Date accepted: 17 June 2021

Date published: 10 December 2021

1 Though not especially contemporary, one might note Watts' Sing to the Lord with joyful voice.

2 Mare (2000:220-222) reaches similar conclusions.

3 Because of the closeness of these elements, Waltke & Houston (2019:255) prefer a two-part structure, combining the first two stanzas. Although this does not significantly affect the poem's meaning, noting the changing grammatical structure at verse 5 makes the three-part model slightly preferable. Amzallag (2014:540-542) develops a complex model of antiphonal responses, although the fact that it requires the title to be part of the poem's structure makes this less likely.

4 In all this, Psalm 94 might seem to be an outlier, but Howard (1999) has demonstrated various ways in which it is integrated into the collection. See also deClaissé-Walford et al. (2014:709-710).

5 On titles as creating different types of links within the Psalter, see Firth (2020:29-34).

6 LXX adds titles to Psalms 93, 95, 96, 97 and 99, while also making Psalm 98 Davidic (a standard motif in these titles). Waltke & Houston (2019) defend the value of these titles, although it is more common for these additions to be discounted outside of studies of the LXX Psalter.

7 As Wray Beal (2019:163) notes, the verb in Joshua is also part of the deliberate contrast with Rahab, so that Achan's "confession" stands in contrast to Rahab's praise.

8 In this instance, the change is so sharp that it challenges the unity of the psalm. For a defence of its unity, and a brief overview of key literature, see Goldingay (2008:89).