Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 suppl.32 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup32.19

ARTICLES

A transforming body: A post-exilic reading of Psalms 50 and 51 in the light of social norms communicated through the Leviticus sacrificial system and body imagery

L. Sutton

Department Old- and New Testament Studies, Unviersity of the Free State. E-mail: suttonl@ufs.ac.za ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5502-5932

ABSTRACT

Although Psalms 50 and 51 do not share the same superscription (a Psalm of Asaph and a Psalm of David), they do share multiple images relating to the body and the cult. Situated between a collection of Korahite (42-49) and Davidic psalms (51-70[51-72]) in Book II of the Psalter (4272), Psalm 50 is considered to be part of the liturgy with a prophetic character. The psalm, with its strong focus on offering, brings about the renewal of Israel before God. Psalm 50 focuses on the community, while in Psalm 51, the focus is on the individual. In Psalm 51, body imagery becomes an essential part of describing the acts of purification, penitence and offering. Reading these Psalms in the light of social norms communicated through the Leviticus sacrificial system and body imagery, the body's renewal process (community and individual) before God becomes apparent.1

Keywords: Psalms 50 and 51, Social norms, Leviticus sacrificial system, Body imagery

Trefwoorde: Psalms 50 en 51, Sosiale waardes, Levitikus offer stelsel, Liggaamstaal

1. INTRODUCTION

The study of the cult concerning the covenant and repentance and its impact on the shape and shaping of the Psalter2 has taken a new turn in recent publications (see Attard 2016; Hensley 2018). A topic in this regard that needs further attention is the use of sacrifice as a way to communicate social norms in the editing of the Psalms. The purpose and the motives of sacrifice in the book of Psalms is traditionally understood in mainly three categories, namely thanksgiving, petition and homage (Courtman 1995:4146). In a few Psalms, the motive of sacrifices is questioned. Among these are Psalms 50 and 51.3

Although Psalms 50 and 51 do not share the same superscription (a Psalm of Asaph and a Psalm of David), they do share multiple images relating to the body and the cult, and specifically to sacrifices. Situated between a collection of Korahite (42-49) and Davidic psalms (51-70[51-72]) in Book II of the Psalter (42-72), Psalm 50 is considered as part of the liturgy with a prophetic character. The psalm, with its strong focus on offering, brings about the renewal of Israel before God. In Psalm 51, body imagery becomes an essential part of describing the acts of purification, penitence and offering. Individually, in each of these psalms, it seems at first glance as if sacrifices are viewed negatively by many scholars;4however, reading them together in their final placement after the editing of the Hebrew Psalter in a post-exilic context may present a different view.5This can be done by evaluating the communicative value of the sacrificial and body imagery in these Psalms. This process of renewal leads to a transformation of the body.

For the purpose of this article, the Levitical sacrificial system6 is used to understand the social norms communicated through the sacrificial system and body imagery. The imagery in Psalms 50 and 51 regarding sacrifices and body imagery is evaluated in the light of the Levitical sacrificial system to indicate a possible relationship between these two Psalms and to establish whether the sacrificial language in these Psalms should be understood as positive or negative. By establishing if the language is viewed positively or negatively, the message communicated through the sacrificial and body imagery becomes more apparent. To achieve this, firstly, the social norms communicated through the Levitical sacrificial system will be established. Secondly, the social norms communicated through body imagery will be formulated. Thirdly, these norms will be applied to Psalms 50 and 51 to evaluate what these Psalms communicate through the use of sacrificial and body imagery.

2. SOCIAL NORMS COMMUNICATED THROUGH THE LEVITICUS SACRIFICIAL SYSTEM

In the Priestly writings of Leviticus (P), the first seven chapters in the book describe sacrifices7 and how they must be performed.8 The burnt, grain and peace sacrifices are the first three in these chapters that were all voluntary. They functioned as a way to show praise or worship and reverence to God (Boda 2009:60).9 The worldview of P concerning sacrifices in these chapters gains clarity when one studies the detail of these sacrifices regarding who served them, and how and where they were performed.10The order of sacrifice and what was sacrificed play an essential part in establishing why it was necessary to make these sacrifices. In Leviticus 10, one sees crucial elements of P's worldview,11 those of holiness and purity.12 With holiness and purity come the degrees of these concepts as understood by P (see Lev 11; 13-14; 15; 18:6-30; 20:3).13 From Leviticus 10:10 and 16:13, the need for sacrifices concerning holiness and purity14become more evident as a way to "place the holy within Israel" (presence of YHWH in relation to the people). Janzen (2004:103) describes it:

As should be clear, the presence of YHWH within Israel poses moral as well as cultic problems, for the categories delineated by holiness impact action (that is, moral decisions) as well as being. Sacrifice within this worldview of holiness keeps separate the holy and the most holy from the impurity of Israel, who surrounds the tabernacle.

Impurity brings separation15 between the impure and the holy. To avoid contact between the holy and the impure, sacrifices are needed. At the tabernacle, sacrifices are offered to mark the end of a period of impurity, and through the ritual that is performed by the priest, an act of final cleansing is indicated (Lev 12:7, 8). Purity is therefore firstly achieved through the passage of a period of time, whereafter the ritual of sacrifice is a mark of cleanliness. It is removing the distance between the impure and the holy consequently (Janzen 2004:105). It seems then that in P, there is no distinction between cultic and moral sins as impurity becomes a cultic and moral problem (Boda 2009:53; see Morrow 2017).16 This said, debt offerings in the Priestly law address actions that may be interpreted as sin. All sin can be expiated, but not necessarily with sacrifice. The effects of sin are addressed in the participation of rituals concerning atonement. The purification offering (חטַַּא֥ת, Lev 4:1-5:13; Ps 51:4, 5)17 and the reparation offering (אשֵָׁם֖, Lev 5:14-6:7)18 are debt offerings. According to the Priestly interpretation, sin can be classified into three categories, it seems (Gane 2010:252; see Morrow 2017:149). The first of these is high-handed sin or actions that are considered defiant and deliberate, meaning that they are against moral and cultic regulations. The action of sin is done in full knowledge of the perpetrator (see Num 15:30-31) and is therefore considered unforgivable and inexpiable through sacrifice. The outcome of this sin is that the perpetrator is removed from his/her people either by judicial action or divine punishment. The death penalty is, in many instances, the desired outcome (understood literally or metaphorically -see Lev 20:10-13). The second category of sin is that of inadvertent sins that are committed unintentionally. According to Priestly law, these are therefore expiable through sacrifice, specifically purification sacrifices (see Lev 4; 5:1-6; Num 15:22-31). The third category of sin is nondefiant deliberate sin, where a person encroaches upon divine commandments but does not "intend to betray a basic loyalty to God of Israel". These sins are expiable through sacrifice, specifically through reparation offerings (see Lev 16:1-7; 16:24) (Morrow 2017:148-155; see Boda 2009:61). Another important factor concerning sin in the book of Leviticus is the Day of Atonement. For the purpose of this article, it may be noted that the Day of Atonement is used to address all iniquities and transgressions regarding all the sins of the people of God, especially intentional sin, as those who have sinned intentionally cannot bring a sacrifice to the sanctuary. The high priest must do it on this day of purification (Lev 16). On this day, nondefiant and defiant sins can be addressed as the purpose of the day is to purify the sanctuary with the result of purifying the people of God (Lev 16:30) (Boda 2009:67-68).

William Morrow (2017:132) indicates the importance of examining the communication value of sacrifices in the Bible.19 In his discussion, he identifies three critical areas when asking about the communicative value of biblical sacrifice.20 The first of these three is social solidarity. Social solidarity21 is understood as part of how sacrificial rituals contribute to constructing a sustainable community. In this regard, Morrow (2017:133) focuses on how a sacrifice is consumed by its offerers or representatives, or its consumption on the altar by fire and blood sprinkling. In this regard, it literally and symbolically becomes a meal that in the social space of ancient Israel included the community and the divine in order to sustain the need for the group's social solidarity (Morrow 2017:133). The second communicative value is social indexing. Social indexing is understood by Morrow (2017:134) as indicating who in the social community or group is at the centre and who is on the edge or even outcast. Sacrificial rituals contribute to this social-communicative indexing by the way in which a piece of the offering is given to the deity (the fat of the animal) or where the entire animal is burnt as a whole on the altar, for example, as in the case of a burnt offering.22 This communicates the importance of the deity to the community and establishes a pure and holy relationship with God. The third communicative function is that of conflict resolution. Conflict resolution is considered by Morrow (2017:134-136) as part of a sacrificial ritual's function to resolve conflicts that threaten the group's sense of solidarity. Moving from a negative to a positive state is essential, as this also influences the distance or rather the relationship between the individual or group and their diety. Douglas Davies (1977:394; see Boda 2009:51-52) created a polar chart between the negative and the positive poles and the importance of opposite thinking in Leviticus. How this was achieved by sacrifice may be debated. Still, it can be observed if one considers the purification (see Lev 4:1-5:13) and reparation offerings (see Lev 5:14-6:7) as well the Day of Atonement (see Lev 16) in Leviticus. These three communicative values of sacrificial rituals help sustain a society in symbolic terms as they promote a strong relationship between the group and God (Morrow 2017:135-137). In this regard, Morrow may arguably also be called an anthropological functionalist, as Janzen (2004:13) also called Emile Durkheim, who argued that ritual could be understood as a way in which the group reaffirms its loyalty to God. This social unity is, of course, not the only thing a ritual can communicate (see Janzen 2004:17).23

Evaluating these three categories, namely social solidarity, social indexing and conflict resolution, makes it apparent that parallels to all sacrificial actions cannot be determined in all of them equally. Still, the importance of the social value communicated by the ritual to the people who are participating in it must be considered. Janzen (2004:10, 34) indicates that rituals in general and ritual sacrifice as a social act must be understood in their contexts as they maintain authentic community with the deity. For this reason, the essential role sacrifices perform as social communication serves as social rhetoric to persuade or to influence others (see Morrow, 2017:131). The social context, or rather the ritual context, is vital because rituals are performed within a context of events before and after them (Janzen, 2004:14). The social function of the ritual only finds its meaning in the context. Therefore, the same ritual performed in different social or historical contexts may have different social meanings. Another critical factor is the order in which the events happen in relation to the ritual; this factor will also contribute to social indexing. Ritual characteristics make rituals successful in communicating social values: they are a set of formalised actions and are done repeatedly (see Janzen 2004:24; Morrow 2017:131). For this reason, social solidarity is communicated through sacrificial rituals as they are done repeatedly and can be considered normal. The group being part of this thus experiences solidarity. Janzen (2004:25-30) stipulates that when it comes to the communicative strategy or rhetorical strategies of rituals, they are not only intended to persuade the members of a social group to conform or to be part of their specific worldview,24 but can also be used to bring distance between a social group's members and other societies. This is subject to a group's worldview and moral system, knowing that the ritual persuasion is not always successful.

3. SOCIAL NORMS COMMUNICATED THROUGH THE BODY

As stated above, ritual sacrifices are not the only way social norms can be communicated. Just as sacrifices communicate social norms in terms of boundaries between people and God concerning being holy and pure and creating a sustainable community, body imagery communicates these boundaries by using concrete images of the human body.25 The communicative value of the human body can first be understood in terms of the ears and the mouth (as a zone of self-expressive speech).26 These images can be understood literally or metaphorically. The boundary image concerning the mouth can be understood in terms of what can go into (for instance, food) and what can come out (for instance, speech) of the mouth. This imagery can communicate anything from purity to impurity, depending on what is going in or coming out of the mouth. Speech should be evaluated as it can be used as a "key strategy for establishing, maintaining and defending honour" (McVann 2016:25-26; see also Pilch 2016:114-118). It can therefore communicate honour and also be used to shame others. What is spoken should be acceptable and within the boundaries of the acceptable social worldview to establish social solidarity in the community. The ears are parallel to the mouth, and that which is going into the ear (what is said) should also be considered as pure and unpolluted. The imagery can be used to communicate what is wrong and what should be done to rectify the relationship or boundaries between pure and impure, holy and unholy, in order to resolve conflict and restore balance. In the psalms, the ears and mouth are used in many instances to communicate, call, shout or ask someone or the divine to hear so as to act and change or resolve the current situation (positively or negatively).27

Communicativeness is effective, valued, and prized if it endorses and explicates the world view and ethos held by the culture in general, i.e. if it upholds and defends tradition. It is inadequate, untrustworthy, or contemptible if it challenges, denies, or repudiates the culture's core values. The world view and its values are structured and informed by what is understood to be God's revealed law... The degree to which communicativeness conforms with the ethical requirements of observance of law is the degree to which it may be understood as authentically communicative (McVann 2016:26).

Human behaviour is further communicated through the body imagery of the eyes and heart (as a zone of emotion-fused thought). The heart is the seat of thought in the human body, where the heart receives its input from the eyes. The input, as with the ears and the mouth, can be evaluated negatively or positively. The communicative value is expressed in different metaphors related to the heart (Malina 2016a:58-61). Imagery related to the heart functions mainly in three ways, namely, vegetatively (physical nature of the heart), emotionally (heart is seen as one of the seats of emotion, in many instances in relation to the kidneys), and noetically (as the seat of human thought) (Janowski 2013:157-158). An important function is when the heart is used to evaluate the innermost part of the body (see Pss 51, 139). In this regard, the heart is not used only as part of the assessment of the person but also as part of the refinement of the person or of purification language (imagery of fire and water is used in relation to the heart and kidneys) (see also Keel 1978:184; Sutton 2018:247-248).28

The capabilities and actions of the human body are communicated through the imagery of the hands and feet, which represents purposeful activity.29 Intentionally or unintentionally, sinning (any of the three categories considered in the P writings) will be regarded as an act that can be categorised under purposeful activity. The activity can, as with the other imagery, express positive or negative imagery. The communicative value of the act will determine how it must be viewed and whether or not the imagery contributes to possible conflict resolution as with Psalms 50 and 51.

4. READING PSALMS 50 AND 51 IN THE LIGHT OF SOCIAL NORMS COMMUNICATED THROUGH THE LEVITICUS SACRIFICIAL SYSTEM AND BODY IMAGERY

4.1 Content and structure of Psalms 50 and 51

Psalm 5030 is the first Asaph psalm in the Psalter31 and is followed by a group of Davidic psalms. According to Gerhard Wilson (2002:758), Psalm 50 shares thematic links with Psalms 44-49, from the concerns of the safety and security of Zion/Jerusalem and the collapse of the Davidic monarchy, to the festive celebrations of the king, and specifically with Psalms 46-49, with the focus of God as a fortress in whom the "exilic community must place their trust."32

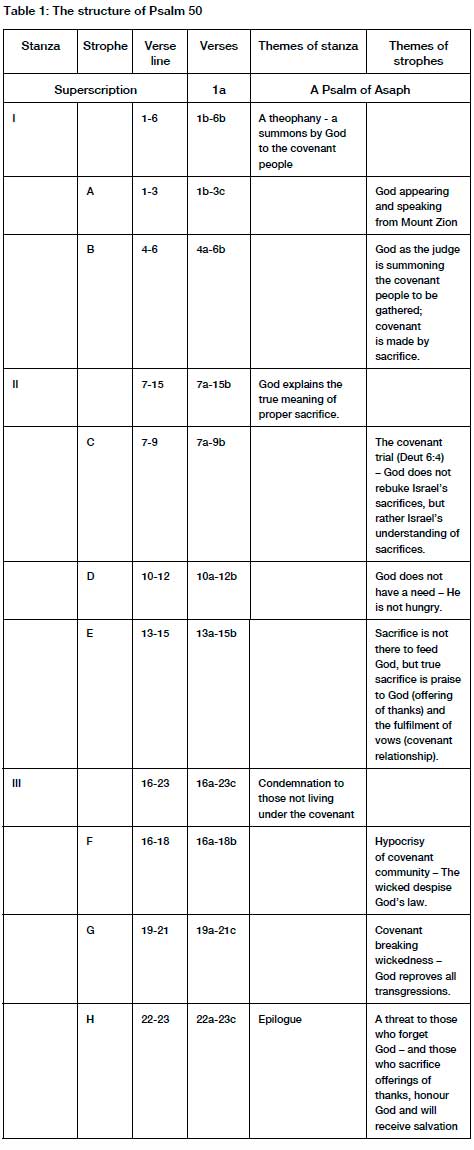

The first verses (vv. 1b-6b) of Psalm 50 set the tone of the psalm as a theophany. YHWH is presented as the God of gods (v. 1b) and later as the Judge (vv. 4b, 6).33 In these verses, a summons is made to the world (v. 1b - to observe), heavens and earth (v. 4 - as witnesses of the covenant), and the covenant people (vv.5).34 From verses 7-15, the true meaning of sacrifice is explained through a divine speech. These verses become an address to the whole community on how they practice worship. God explains that he does not need their sacrifices as food; therefore, sacrifice has different purposes and meanings (vv 8-13, see Lev 1, 3 concerning whole offerings). It is better to sacrifice thanks or gratitude to God (v.14), as gratitude is more important than thinking God needs sacrifices as food (see Goldingay 2007:115-116). In verses 16-21, the divine speech focuses on the condemnation of those not living under the covenant. Wilson (2002:763) explains that their inner commitment to God is the problem, which is why their sacrifices do not have any meaning. Six examples are presented in the following verses on how they do not follow the covenant (vv. 17-20). In verse 21, God explains that he will judge and that by keeping quiet (v.21 - compare with v.3), he was not fooled by their actions. The divine judgment is severe, using animal imagery of tearing apart (v.22), but those who sacrifice offerings of thanks, honour God and will receive salvation (v. 23).35 According to Craigie and Tate (2004:367), the purpose of Psalm 50 is to explain the importance of the covenant relationship (the communicative value of social solidarity). The relationship must be reestablished after the exile (resolving conflict - the communicative value of conflict resolution).36 The structure of Psalm 50 can be seen as the following (see also Wilson 2002:759; Terrien 2003:395-396; Craigie and Tate 2004:363-364; Goldingay 2007:110; Van der Lugt 2010:82-83, 87-88):

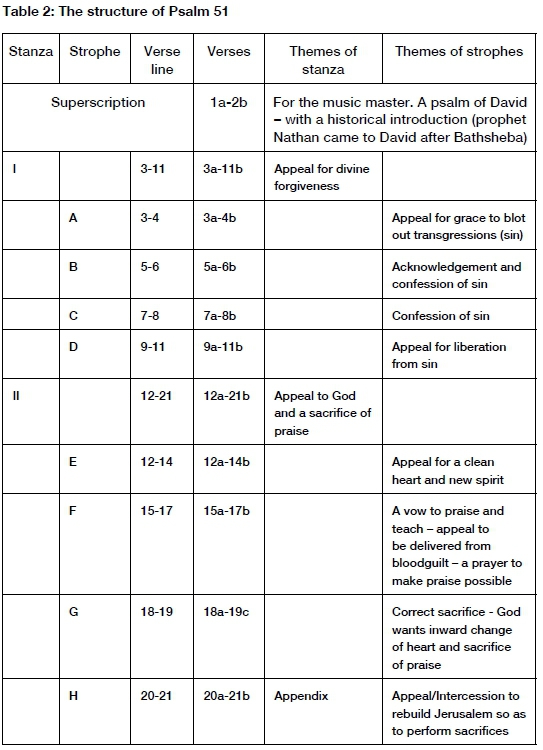

Psalm 5137 is classified by many as being an individual lament of a sick person. This classification seems to be problematic as the content does not seem to support the hypothesis. In recent years, Psalm 51 has been viewed as part of the penitential psalms (Pss 6; 32; 38; 51; 102; 130; and 143).38 As a penitential psalm, the speaker or the one praying the psalms can be understood as an individual or a collective voice. Holt (2017:110) supports the interpretation of Zenger (Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:16-18) by interpreting this psalm as having two main sections focusing on a central theme in the psalm, an appeal to God for cleansing or purification of the heart and spirit.39 The two main sections focus on the transgressions of the psalmist, with an appeal for forgiveness in the first section (vv. 3-11), and an appeal to God (outcome of mercy) and a sacrifice of praise (vv.12-19) in the second section, with an appendix that is a prayer for the rebuilding of Jerusalem (vv. 20-21).40 Holt (2017:113) argues that Psalm 51 must be understood as a "written penitence for the use of absolute penitence when caught in flagrante delicto" (Holt 2017:117). The psalm for Holt (2017:117121) must be understood as a penitential psalm in the Axial Age (time of the late monarchy, the exile and Second Temple period), demonstrating a renewed reflection on the unreserved sinfulness of the people who are discussed by the scribes who placed this psalm in its final shape in the Psalter in Second Temple period.41 The structure of Psalm 51 can be seen as follows (see Tate 1990:12; Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:16-17; Van der Lugt 2010:92-93, 97-98; Holt 2017:110):

4.2 Reading Psalms 50 and 51 as a unit

Book II of the Psalter starts with a collection of Korahite psalms (42-49). Bellinger Jr. (2019:78) reads these psalms as a literary expression of the trauma of the exilic community concerning the destruction of the Jerusalem temple, where the covenant community would have experienced the presence of YHWH. Psalms 42-43 express this sentiment and the journey of the exile, with a longing to worship at the temple in order to encounter God (social solidarity). Psalm 44 recalls the community's obedience to the covenant, and according to the people (again social solidarity), YHWH's avoidance of the covenant (Ps 44:18-23). Psalm 45 presents a royal perspective that is more hopeful, followed by Psalms 46-48, which express YHWH's choice of Zion as his place of dwelling (divine presence - a central theme for Leviticus). Psalm 49, as a wisdom psalm, provides guidance that that which brings life is a true relationship with YHWH (social solidarity). Jerusalem, Zion, the temple, covenant and being in the presence of God are the themes that connect this Korahite collection to Psalms 50 and 51. Psalm 50 as a Psalm of Asaph becomes the connection between the Korahite collection and the collection of Davidic psalms that follow, with Psalm 51 as the first of this group. The calling of the covenant community in Psalm 50 and God seeking his people to repent and to be in solidarity with each other again is answered in Psalm 51, with the repentance of the figure David (representing the nation). For Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:23; see also Bellinger Jr. 2019:79), the Davidic figure in Psalm 51 becomes a "messianic figure who calls his people to repentance and keeps alive the hope for Zion's eschatological fulfilment."42

Attard (2016:93-107) discusses at length the connections between Psalms 50 and 51 in relation to genre, structure and exegetical observations.43He notes that the psalmist in Psalm 51 does not try to plead innocence but rather expresses a state of sinfulness that is not different from the sins mentioned in vv. 17-20 in Psalm 50, that must be viewed as merely representative and not a complete list of sins. Sacrifice, sin, repentance and restoration (renewal) are shared themes within these psalms, where the Davidic Psalm (51) is a response to the Asaph Psalm (50). Attard (2016:106) points to the fact that this indicates how the rhetorical implications of different Levitical collections have consequences for each other. Both of these psalms start with a description of God. Although Psalm 51 does not list sins, other than by providing an introduction that alludes to a sinful narrative (2 Sam 11-12), Psalm 50 provides the list that is indicated in the narrative (adultery - Ps:18). Both of the psalms focus on Zion, where the address made to the community in Psalm 50:16 is acknowledged in Psalm 51:6 and therefore becomes the penance that must be followed by the community as a whole (Attard 2016:107).

In Psalm 50:8-13, the idea is given that the sinners are trying to blind the eyes of YHWH with their sacrifices, and in Psalm 51:18, the one praying is stating that he knows that this will not work. The falseness of Psalm 50:8 is therefore addressed in Psalm 51:5 through repentance.44 The result of this repentance is that the sinners (Ps 50:16-21) will now be taught about the forgiveness that they received (Ps 51:15). The purpose and outcome are that the sacrifices not acceptable in Psalm 50 will again become acceptable (Ps 51:20-21).45

Gaiser (2003:388) indicates that the structures of Psalms 50 and 51 could be viewed as concentric structures based on thematic units concerning the critique of sacrifice. He proposes the following concentric structure (Gaiser 2003:388 - the structures presented in Tables 2 and 3 are assimilated in brackets in Gaiser's structure):46

F 51:5 a sinner when my MOTHER conceived me E 51:6 teach me wisdom D 51:14 deliver me from bloodshed...and my tongue will sing aloud C 51:16 you have no delight in sacrifice B 51:16 if I were to give a BURNT OFFERING A 51:18, 19 Do good to ZION...then you will delight in right SACRIFICE

A 50:1-6 On Zion and sacrifice (covenant is made by sacrifice) B 50:7-15 On sacrifice and deliverance (true meaning of proper sacrifice)

C 50:16-21 The rebuke (condemnation of those not living under the covenant)

D 50:22-23 Call to repentance/divine wrath (a threat to those who forget God - and those who sacrifice offerings of thanks, honour God and will receive salvation)

E 51:superscript Nathan oracle D 51:1-2 Turn to God/divine grace (appeal for grace to blot out transgressions) C 51:3-9 Confession (acknowledgement and confession of sin) B 51:10-17 On deliverance and sacrifice (appeal to God for a clean heart and new spirit and a sacrifice of praise) A 51:18-19 On Zion and sacrifice (appeal/intercession to rebuild Jerusalem in order to perform sacrifices) From this concentric structure, the rhetorical use of sacrifice and the fact that sacrifices perform a key communicative element in these two psalms becomes apparent.

4.3 Social norms communicated through the Leviticus sacrificial system and body imagery

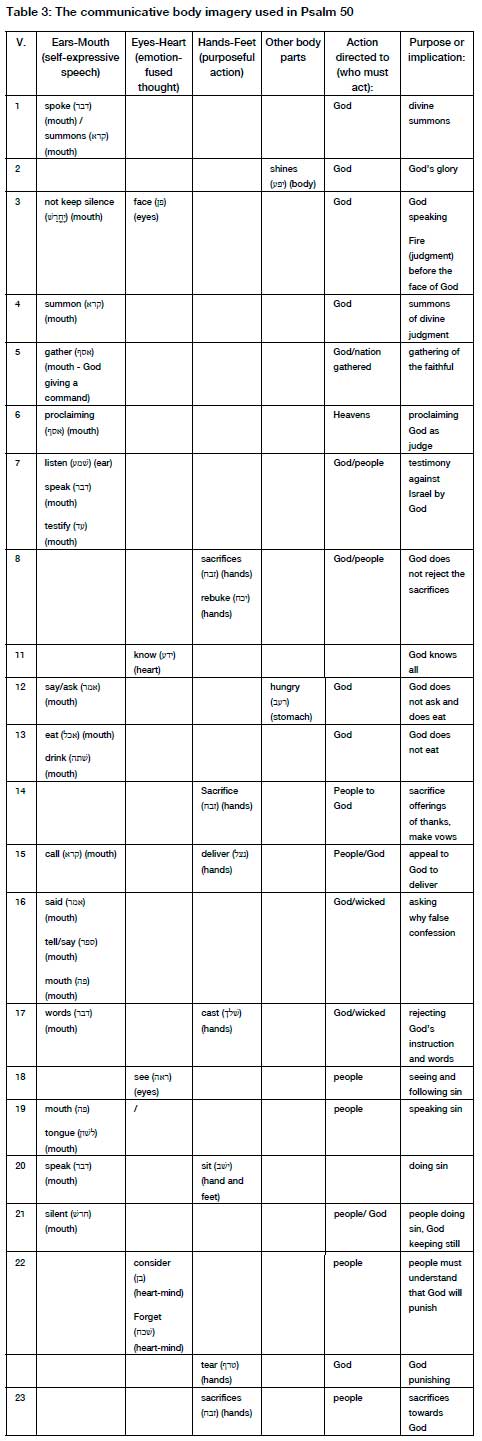

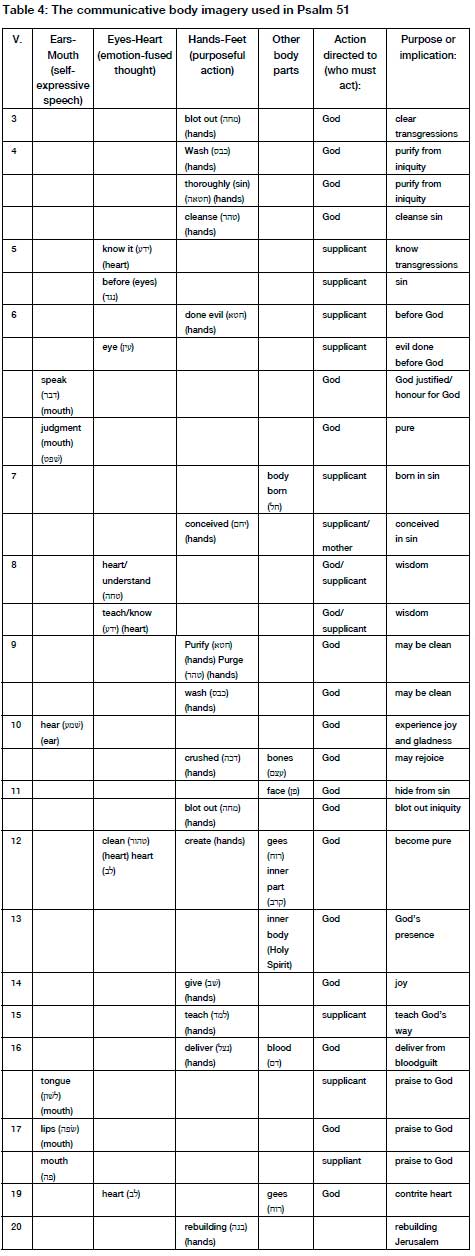

In Tables 3 and 4, the body imagery communicated in Psalms 50 and 51 is structured according to the social norms communicated through the body imagery of the ears-mouth, eyes-heart, and hands-feet and other body imagery related to the inner or outer body. Further, it is indicated who performs the actions or to whom the actions/imagery are directed to indicate the purpose or implication of the imagery. This is then understood as indicating the social norms that are communicated through body imagery in these psalms.

In Table 3, it is indicated that the body imagery in Psalm 50 is dominated by imagery concerning the ears-mouth zone, which focuses on communicating self-expressive speech. The purpose of the ears-mouth imagery is YHWH as the Judge, who is summoning his covenant people (vv.1-6) using expressive imagery: spoke, summons (v.1), not keeping silent (v.3), summons (v.4), gather (v.5), and proclaiming (v.6). The expressive speech imagery using the mouth-ears continues in verses 7-15, where YHWH gives testimony against the people, explaining the true purpose of sacrifice (listen, speak, testimony - v.7; say, drink - v.12; call - v.15). In verses 16-21, the imagery expresses condemnation towards those not living under the covenant. The instances of ears-mouth imagery used in these verses are: said (false confession), say, mouth (v.16); words (rejecting God's instructions - v.17); mouth, tongue (v.19); speak (v.20); and silent (v.21). Purposeful action is communicated through the hands-feet imagery in vv. 22-23, communicating that salvation and honour are given to God through proper thanksgiving sacrifices. God seeks social solidarity with his covenant people, but the relationship is in conflict (conflict resolution is not yet attained), hence the negative view on sacrifices in verses 7-15 and why correct sacrifices are needed. The conflict is explained in verses 16-21, by indicating the hypocrisy of the covenant community. Only after the conflict is resolved will sacrifices of thanks offerings be acceptable again (vv. 2223). Social solidarity is sought, but due to the current conflict between God and His people, conflict resolution is not yet established. In this regard, it is not the act of sacrifice that is viewed negatively in the psalm, but because conflict resolution is not yet achieved, the communicative value and purpose of sacrifices is also not achieved, and therefore performing them then is considered by God to be empty (negatively - vv. 7-15).47

Where the body imagery is predominantly related to the zone of the ears and mouth in Psalm 50, the imagery in Psalm 51 is connected to the zone of the hands and feet, according to the analysis of Table 4. The one praying the psalm asks God to blot out (vv. 3, 11), wash (vv. 4, 9), cleanse and purify him (vv. 4, 9) from his transgressions. The imagery is reinforced by imagery from the eyes-heart zone that indicates that the petitioner is not only aware of what he has done (vv. 5, 6, 8, 12, 19 - knowledge-heart) but is also aware that it is not only the outer body that needs to be cleansed but also the inner body and therefore the imagery of the heart and spirit (vv. 12, 13, 19). The inner body parts are those parts of the body that can distinguish between right and wrong. That knowledge must lead either to change or not (see Walters 2015:99; see also Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:21). The ears and mouth zone further contributes to the person's transformation, pleading for forgiveness as a pleasing transformation with the heart and spirit using the tongue (v.16), lips, and mouth (v.17). The ears-mouth imagery is enclosed in the imagery of the heart and spirit (vv. 12-14//18-19) and the corresponding statements regarding sacrifices (see Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:17). The imagery constitutes the transformation of the inner body of the petitioner.

For Hwang (2017:690-691), the confession of sin, or rather the appeal to be forgiven, is not so much the supplicant's desire to reverse the sin or the suffering but rather to be forgiven by God so as to maintain or to seek God's honour (see Pss 25, 32, 69, 86). Groenewald (2009:50) explains the critical evaluation of sacrifice in Psalm 51: that sacrifice alone is not enough (vv. 18-19) and that what is expected from the one praying the psalm is also a "broken and contrite heart." The psalm is not against burnt offerings or other debt offerings. Psalms 50 and 51 clearly communicate through body imagery that what is needed is purification. To become clean, pure and holy, true repentance is needed, meaning that one needs a clean heart and spirit. The purposeful action (hands-feet) of the words in Psalm 51 to "blot out," "wash," and "cleanse" all indicate this. The communicative value lies in the purposeful action (hands-feet) that wants to resolve the conflict (conflict resolution) between YHWH and his people, to bring renewal to his people and to the covenant relationship in order to reinforce social solidarity. Social solidarity is re-established by remembering that physical offering is not the only process to establish solidarity. From Leviticus, the function of sacrifice is to indicate how members of the group can be included, establishing social solidarity (positive interpretation of sacrifice).

5. CONCLUSION

In Psalms 50 and 51, sacrifices are used to communicate the correct way in establishing social solidarity, as communicated by Leviticus. If the correct way is not followed, then the function of the sacrifice is irrelevant and becomes an obsolete or rather an empty ritual.48 Therefore in both of these psalms, it is indicated why God does not need burnt offerings. Burnt offerings are not required if what must be communicated by the ritual is not correct. In the beginning of this article, it was indicated that sacrifices are offered to mark the end of a period of impurity as an act of final cleansing (Lev 12:7, 8). Purity is therefore firstly achieved through the passage of a period of time, whereafter the ritual of sacrifice is a mark of cleanliness.49 The true meaning of sacrifice is captured in the entire process from understanding the sin committed (what type of sin - Pss 50:16-21; 51:1-6)50, confession (Ps 51:3-9), forgiveness (Ps 51:10-17), total dependence on God and His mercy (Pss 50:23; 51:18-21), and finally living in the salvation of God (Pss 50:23; 51:14) (see Courtman 1995:55; Tate 1990:26-28; Hossfeld & Zenger 2005:22-23; Groenewald 2009:50). It is removing the distance between the impure and the holy consequently (see Janzen, 2004:105). In Psalm 50, the order and appeal made by God through the body imagery are to the covenant people, those with whom God seeks a relationship (Ps 50:4-6 - social solidarity). In Psalm 51, the body imagery communicates a petitioner (a community) that through purposeful action (hands-feet imagery) seeks to make penitence with God to have a pure heart and spirit (inner transformation) and be able to bring sacrifices to God (social solidarity). In the end, for Psalms 50 and 51, what is needed is a body that has gone through a transformation from unclean to clean to proper sacrifices. In a post-exilic context, a transformed body is required for the renewal and restoration process after a period of conflict and separation, to restore social solidarity between YHWH and His people.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Attard, S.M. 2016. The implications of Davidic repentance. A synchronic analysis of Book 2 of the Psalter (Psalms 42-72). Roma, Italy: Gregorian & Biblical Press. [ Links ]

Barrett, M.P.V. 2017. A paradigm of confession: An Analysis of Psalm 51:1-9. Puritan Reformed Journal 9(2):21-35. [ Links ]

Beokwith, R.T. & Selman, M.J. (EDS). 1995. Sacrifice in the Bible. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers. [ Links ]

Bellinger Jr. W.H. 2019. Psalms as a grammar for faith. Prayer and praise. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press. [ Links ]

Boda, M.J. 2009. A severe mercy. Sin and its remedy in the Old Testament. Wiona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Boshoff, W., Soheffler, E. & Spangenberg, I. 2008. Geskiedenis en geskrifte. Die literatuur van ou Israel. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis. [ Links ]

Oourtman, N.B. 1995. Sacrifice in the Psalms. In: R.T Beckwith & M.J. Selman (eds), Sacrifice in the Bible, (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers), pp. 41-58. [ Links ]

Oraigie, P.O. & Tate, M.E. 2004. Psalms 1-50. Second Edition. Word Biblical Commentary 19. Columbia: Nelson Reference & electronic. [ Links ]

Davies, D. 1977. An interpretation of Sacrifice in Leviticus. Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentlische Wissenschaft 89:387-399. [ Links ]

deOlaissé-Walford, N. 1997. Reading from the beginning. The shaping of the Hebrew Psalter. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. [ Links ]

deOlaissé-Walford, N. 2004. Introduction to the Psalms. A song from Ancient Israel. St. Louis, MO: Chalice. [ Links ]

deOlaissé-Walford, N. 2014a. The canonical approach to scripture and the editing of the Hebrew Psalter. In: N. deClaissé-Walford (ed.), The shape and shaping of the Book of Psalms. The current state of studies. Ancient Israel and its literature 20 (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature), pp. 1-11. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qh23j.5 [ Links ]

deOlaissé-Walford, N. 2014b. The meta-narrative of the Psalter. In: W.P. Brown (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the Psalms (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 363-376. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199783335.013.024 [ Links ]

declaissé-Walford, N., Jacobson, R.A. & Tanner, B.L. 2014. The Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans. New International Commentary on the Old Testament (NICOT). [ Links ]

DiFransico, L. 2015. Identifying inner-Biblical allusion through metaphor: Washing away sin in Psalm 51. Vetus Testamentum 65(4):542-557. [ Links ]

DiFransico, L. 2018. Distinguishing emotions of guilt and shame in Psalm 51. Biblical Theology Bulletin Volume 48(4):180-187. [ Links ]

Dozeman, T.B. 2017. The Pentateuch. Introducing the Torah. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Eberhart, CA. 2004. A neglected feature of sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible: Remarks on the burning rite on the altar. The Harvard Theological Review 97(4):485-493. [ Links ]

Eberhart, CA. 2011. Sacrifice? Holy smokes! Reflections on cult terminology for understanding sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible. In: C.A. Eberhart (ed.), Ritual and metaphor. Sacrifice in the Bible (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature), pp. 17-32. [ Links ]

Gane, R.E. 2010. Loyalty and scope of expiation in Numbers 15. Zeitschrift für Altorientalische und Biblische Rechtsgeschichte 16:249-262. [ Links ]

Gaiser, F.J. 2003. The David of Psalm 51: Reading Psalm 51 in light of Psalm 50. Word & World 23(4):382-394. [ Links ]

Goldingay, J. 2007. Psalms. Volume 2: Psalms 42-89. Baker Commentary on the Old Testament Wisdom and Psalms. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic. [ Links ]

Goulder, M.D. 1990. The prayers of David (Psalm 51-72). Studies in the Psalter, II. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Goulder, M.D. 1996. The Psalms of Asaph and the Pentateuch. Studies in the Psalter, III. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. [ Links ]

Groenewald, A. 2009. Psalm 51 and the Criticism of the Cult: Does this reflect a divided religious leadership? Old Testament Essays 22(1):47-62. [ Links ]

HWANG, J. 2017. "How long will my glory be reproach?" Honour and shame in Old Testament Lament Traditions. Old Testament Essays 30(3):684-706. [ Links ]

Hensley, A.D. 2018. Covenant relationships and the editing of the Hebrew Psalter. London: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Ho, P.C.W. 2016. The design of the MT Psalter: A macrostructural analysis. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Faculty of Media, Arts and Technology. Gloucester: University of Gloucestershire. [ Links ]

Holt, E.K. 2017. "Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean": Psalm 51, Penitential piety, and cultic language in Axial age thinking. In: M.S. Pajunen & J. Penner (eds), Functions of Psalms and Prayers in the Late Second Temple Period, (Germany: De Gruyter), pp. 105-121. [ Links ]

Hossfeld, F-L. & Zenger, E. 2005. Psalms 2: A Commentary on Psalms 51-100. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress. [ Links ]

Howard, D.M. Jr 1997. The structure of Psalms 93-100. Biblical and Judaic Studies from the University of California, San Diego 5. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Human, D.J. 2005. God accepts a broken spirit and a contrite heart - Thoughts on penitence, forgiveness and reconciliation in Psalm 51. Verbum et Ecclesia 26(1):114-132. [ Links ]

Jacobson, R. 2011. "The Faithfulness of the Lord Endures Forever": The theological witness of the Psalter. In: R.A. Jacobson (ed.), Soundings in the theology of Psalms. Perspectives and methods in contemporary scholarship (Minneapolis: Fortress Press), pp. 111-137. [ Links ]

Janowski, B. 2013. Arguing with God. A theological anthropology of the Psalms. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster, John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Janzen, D. 2004. The social meanings of sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Jenson, P.P. 1995. The Levitical sacrificial system. In: R.T. Beckwith & M.J. Selman (eds), Sacrifice in the Bible (Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock Publishers), pp. 25-40. [ Links ]

Johnson, V.L. 2009. David in distress. His portrait through the historical Psalms. New York: T&T Clark. [ Links ]

Jones, D. 1963. The cessation of sacrifice after the destruction of the temple in 586 B.C. The Journal of Theological Studies 14(1):12-31. [ Links ]

Keel, O. 1978 (1997). The symbolism of the biblical world. Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. New York: Seabury Press. [ Links ]

Kimuhu, J.M. 2008. Leviticus. The priestly laws and prohibitions from the perspective of ancient Near East and Africa. Studies in Biblical Literature 115. New York: Peter Lang. [ Links ]

Klawans, J. 2001. Pure violence: Sacrifice and defilement in ancient Israel. The Harvard Theological Review 94(2):133-155. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J. 2001. The New Testament world. Insights from cultural anthropology. Revised and Expanded. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J. 2016a. Eyes-Heart. In: J.J. Pilch & B.J. Malina (eds), Handbook of Biblical social values. Third Edition (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books), pp. 58-61. [ Links ]

Malina, B.J. 2016b. Hands-Feet. In: J.J. Pilch & B.J. Malina (eds), Handbook of Biblical social values. Third Edition (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books), pp. 83-86. [ Links ]

McCann, J.C. Jr 2014. The shape and shaping of the Psalter: Psalms in their literary context. In: W.P. Brown (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the Psalms (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 350-362. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199783335.013.023 [ Links ]

Mcvann, M. 2016. Communicativeness. In: J.J. Pilch & B.J. Malina (eds), Handbook of Biblical social values. Third Edition (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books), pp. 25-27. [ Links ]

Morrow, W.S. 2017. An introduction to Biblical Law. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Olson, D.T. 2017. Is the Concept of "Repentance" a Modern Imposition on the Old Testament? Psalm 51 as a Test Case. Word & World Supplement 7:86-96. [ Links ]

Pilch, J.J. 2016. Mouth-Ears. In: J.J. Pilch & B.J. Malina (eds), Handbook of Biblical social values. Third Edition (Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books), pp. 114-118. [ Links ]

Polan, G.J. 2016. A fitting sacrifice of thanksgiving, praise, and repentance: Psalms 50-51. The Bible Today 54(2):89-94. [ Links ]

Robertson, O.P. 2015. The flow of the Psalms. Discovering their structure and theology. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing. [ Links ]

Ross, W.A. 2019. David's spiritual walls and conceptual blending in Psalm 51. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 43(4):607-626. [ Links ]

Smith, J.M.P. 1922. Law and rituals in the Psalms. The Journal of Religion 2(1):58-69. [ Links ]

Smith-Cristopher, D.L. 2002. A Biblical Theology of Exile. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Sutton, L. 2018. The anthropological function of the outcry "When God searches my heart" in Psalm 139:1 and 23 and its later use in Romans 8:27. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 4(2):243-263. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2018.v4n2.a12 [ Links ]

Tate, M.E. 1990. Psalms 51-100. Word Biblical Commentary 20. Columbia: Nelson Reference & electronic. [ Links ]

Terrien, S. 2003. The Psalms. Strophic structure and theological commentary. Volume 1. Psalms 1-72. Eerdmans Critical Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. [ Links ]

Van der Lugt, P. 2010. Cantos and strophes in Biblical Poetry II. Psalms 42-89. Oudtestamentische Studien Volume 57. Leiden: Brill. [ Links ]

walters, S.D. 2015. I talk of my sin (to God) (and to You): Psalm 51, with David speaking. Calvin Theological Journal 50:91-109. [ Links ]

Watts, J.W. 2007. Ritual and rhetoric in Leviticus. From sacrifice to scripture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Watts, J.W. 2011. The rhetoric of sacrifice. In: C.A. Eberhart (ed.), Ritual and metaphor. Sacrifice in the Bible (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature), pp. 3-16. [ Links ]

Willgren, D. 2016. The formation of the "Book" of Psalms. Forschungen Zum Alten Testament 2. Reihe 88. Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H. 1985. The editing of the Hebrew Psalter. SBL Dissertation Series 76. Chico, CA: Scholars Press. [ Links ]

Wilson, G.H. 2002. Psalms Volume 1 . The NIV Application Commentary. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan. [ Links ]

Zenger, E. 1998. The composition and theology of the Fifth Book of Psalms, Psalms 107-145. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 80:77-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/030908929802308005 [ Links ]

Zenger, E. (Ed.) 2010. The composition of the Book of Psalms. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum Theologicarum Lovaniensium 238. Leuven: Peeters. [ Links ]

Date received: 31 October 2021

Date accepted: 5 November 2021

Date published: 10 December 2021

1 This article is dedicated to Prof. Jurie Hendrik le Roux (14 Nov 1944 - 12 October 2021). Prof. Jurie was a remarkable person, a true Old Testament academic, historian and philosopher. He had a wonderful love for the Pentateuch, which he shared as a teacher, mentor and friend.

2 On the topic of the development of canonical-critical research in the Book of Psalms, the shape and shaping of the Psalter, and the meta-narrative of the Psalter, see Wilson (1985); Howard (1997:1-18); deClaissé-Walford (1997; 2004; 2014a:1-11; 2014b:363-376); Zenger (1998:77102; 2010); deClaissé-Walford, Jacobson & Tanner (2014:21-38); McCann Jr. (2014:350-362); Robertson (2015), Ho (2016), and Willgren (2016).

3 See also Pss 40, 69 and 141 (Courtman 1995:48).

4 See Jacobson (2011:137).

5 Ps 51 is traditionally viewed as an exilic psalm. The exilic psalms (Pss 9; 10; 51; 60; 74; 77; 102; 123 and 137) typically express the political hardship and suppression of the Babylonian exile. Some of these psalms are written as from the perspective of an individual who is suffering because of the exile. It is important to realise that in this period the temple in Jerusalem was destroyed and normal cultic rituals and practice could not happen (Boshoff, Scheffler & Spangenberg 2008:162-163). In the Persian period and the early second temple period when the book of Psalms went through its final stages of compilation and editing, the temple and the law again played an extremely important function in the daily lives of the people. This can also be seen in the final editing of the Psalter, in the five divisions of the Psalter (Boshoff et al. 2008:213-214; see also Smith 1922:58-69). It is for this reason that the final placement of Pss 50 and 51 and the communicative value of sacrificial imagery in these psalms must be considered for the post-exilic context.

6 One of the main purposes and motivations for sacrifice is to communicate the commitment between the people of Israel and God. In relation to this, purification and sin must be taken into account. For the purpose of this article, the sacrificial system of Leviticus is used to understand how purification and sin are viewed, as they played an important part during the exilic and post-exilic periods of Israel's history. During the exile, Israel was confronted with the question of why they were in exile, and also during the reign of the Babylonians, Persians and Greeks, they had to understand the boundaries of their own religious identity and relation to their patron God. The sacrificial system communicated these boundaries and is clearly formulated in the book of Leviticus. The sacrificial system communicated Israel's social solidarity with God and illustrated their devotion and consecration. The purity laws contributed in this regard to help the Israelites maintain a pure body that was not polluted and therefore did not trespass on any boundaries that could cause distance between them and the presence of God (see Morrow 2017:137).

7 Eberhart (2004:485-493) focuses on the burning rite that is a component of each of the five types of sacrifices in Lev 1-7. For him the process of burning sacrificial material on the altar transforms the material offering to a suitable offering for God, that makes it "the climax of human communication with God" (Eberhart 2004:493).

8 For a further description and explanation on the sacrifices found in Lev 1-7, see Eberhart (2011:23-30).

9 According to Boda (2009:49-50), Chapters 8-10 are narratives describing the ordination of the priest, followed by Chapters 11-27, which are concerned with regulations for the life of the community of YHWH. Chapters 11-15 focus on ceremonial uncleanness, and Chapter 16 on the prescriptions for the Day of Atonement, followed by the Holiness code, Chapters 17-27.

10 Malina (2001:180-187) makes a valuable contribution to the discussion on how to understand the social space in relation to the sanctuary and sacrifices, and how sacrifices influence how the space between the person or group and God must be understood.

11 For Boda (2009:50), the priestly legislation in the book of Lev "constructs a ritual world, designed to foster the covenant established between YHWH and his people." In this world the presence of YHWH creates a situation where that legislation is needed to address the possible dangers of a community with imperfections living before YHWH and how these imperfections must be defined and dealt with. For a further discussion on the worldview or rather the priestly framework, see Boda (2009:50-52).

12 For a full discussion on the worldview of P and the perspective of holiness and purity, see Janzen (2004:96-110) and Dozeman (2017:363-416).

13 In the work of Kimuhu (2008), prohibitions and the nature of taboos are described and explained in the contexts of the ancient Near East and Africa. The study is helpful to understand some of the degrees and applications of holiness and purity in the Hebrew Bible, especially the family laws that are considered in Lev 18.

14 For a further discussion on the importance of how sacrifice and purity are structurally interrelated in the book of Leviticus, see Klawans (2001:133-155).

15 There are mainly two degrees of separation in Leviticus. The first is between the sacred and the profane and the second is between the pure and the impure (Dozeman 2017:366).

16 For a discussion on the categories of sin, the effect of sin and remedies of sin, see Boda (2009:52-60).

17 חטַַּא֥ת, is traditionally translated as sin offering, but it can be understood as an offering that at its heart focuses on the purification of the sanctuary from human impurities or rather pollution. Again it is about being pure in the presence of YHWH - Lev 4:3 (see also Dozeman 2017:382-385; Morrow 2017:148-149).

18 אשֵָׁם֖, is traditionally translated as guilt offering. The focus of this offering is reparation and therefore it can also be translated as a reparation offering. The focus of this offering is address the trespass of unintentional sin - Lev 5:14-15) (see Dozeman 2017:386; Morrow 2017:148-149).

19 For a further discussion on the rhetoric of sacrifice see the works of Watts (2007; 2011:3-16).

20 One should note that the definition of what constitutes a ritual or a sacrifice is a complicated matter that has been debated among scholars. For the purpose of this article it is understood that cultic acts of sacrifice belong to the category of ritual that is understood as repeated formal actions that communicate essential social values to those who participate in the ritual (see Janzen 2004:34-35; Morrow 2017:130-131). For a detailed discussion on the complexity of the meaning of sacrifice see Eberhart (2011:17-32), and for the use of sacrifice in the Bible see Beckwith and Selman (1995).

21 In the post-exilic community, the priestly theology helped to create boundaries or identity-maintenance through their understanding of purity so as to promote social solidarity. For a further discussion on social solidarity see Smith-Christopher (2002:145-160).

22 The burnt offering (עלָֹה- Lev 1:3-17; Pss 50:8; 51:18, 21), grain offering (מנִחְָה- Lev 2:1-16) and well-being offering (זבֶַח שְׁלמָיִם or שֶׁ֫לםֶ - also translated as a peace offering - Lev 3:1-17; Ps 50:14) are part of the gift or voluntary offerings (Lev 1-3). The first purpose of the burnt offering (an offering that was burnt entirely on the altar) was acceptance (Lev 1:3), where YHWH recognises the offerer as a committed member of the community of God. It is therefore firstly a gift offering. Secondly, the burnt offering was also associated with atonement (Lev 1:4). The burnt offering therefore could act as an expiatory sacrifice for certain sins that the purification offering did not address. The problem is that in Lev 12-15 it is indicated that a burnt offering must be presented after the purification offering, hence the reference to atonement in Lev 1;4, may be to the Day of Atonement where the burnt offering also functions as an atonement ritual (Lev 16:24) (see Jenson 1995:28-29; Dozeman 2017:378-379; Morrow, 2017:141-142).

23 According to Janzen (2004:22), "One difficulty with defining ritual as a kind of communication, however, is the problem of defining it so as to distinguish it from all other kinds of social communications. As Gilbert Lewis points out, if we decide to define ritual as expressive, symbolic or communicative behaviour, then we have managed to extend the meaning of ritual to almost any kind of human behaviour. In order to avoid this difficulty, Wuthnow argues that ritual is not actually a category of behaviour distinct from that of everyday existence, and is simply a dimension of all social activity."

24 The purpose of the ritual rhetoric is to establish commitment and loyalty within those who participate in the ritual so as to strengthen the social group according to the moral system of their social worldview, or rather their social ideology. The purpose of a ritual is always to communicate the truth about a worldview or ideology so as to indicate that this is the correct reality. One should therefore note that for the author of a text, or for a social group, rituals are not understood to communicate ideologies that misrepresent reality. This may be viewed differently from outside social groups or even by those studying the ritual ideology or text as they have to acknowledge their own subjective views (Janzen 2004:57-59, 64).

25 Although this section is explained in terms of the human body, the imagery can in many instances be used to express anthropomorphic language as well. The body imagery and its communicative value can be used for human or divine body imagery (in some instances that of animal body parts as well).

26 Words associated with mouth and ears as self-expressive speech are "mouth", "ears", "tongue", "lips", "throat", "teeth" and "jaws." Action words are "speak", "hear", "say", "call", "cry", "question", "sing", "recount", "tell", "instruct", "praise", "listen", "blame", "curse", "swear", "disobey" and "turn a deaf ear to" (Pilch 2016:115).

27 See An appeal for God to inline his ear - Pss 49:2-13; 88:2, purity and righteousness of the one praying's mouth or speech - Ps 24:3-6, an appeal to be pure - Ps 51 (McVann 2016:26).

28 Words associated with the eyes and heart are "eyes", "heart", "eyelid", "pupil" and their actions "see", "know", "understand", "think", "remember", "choose", "feel", "consider", "look at" as well as "thought", "intelligence", "mind", "wisdom", "folly", "intention", "plan", "will", "affection", "love", "hate", "sight", "regard", "blindness", "look", "intelligent", "loving", "wise", "foolish", "hateful", "joyous", "sad" and "like" (Malina 2016a:61).

29 Words associated with the hands and feet are "hands", "feet", "arms", "fingers" and "legs" and some of the activities are expressed in words such as "do", "act", "accomplish", "execute", "intervene", "touch", "come", "go", "march", "walk", "sit" and "stand" (Malina 2016b:85). Any words expressing a specific action or activity, for instance "work", "stealing", "doing (something)" fall within this category of purposeful activity.

30 It is not the purpose of this article to do a full exegetical analysis of Pss 50 and 51. Both of these psalms have been analysed extensively. For the purpose of this article, the focus will be mainly on how the content of these psalms are structured.

31 For a full discussion on Ps 50 as a Psalm of Asaph, see Goulder (1996:38-52).

32 See also Ho (2016:145-148) on the macrostructure of Book II of the Psalter.

33 "God of gods" is an expression used probably from an older Canaanite polytheism (see Terrien 2003:396). YHWH as judge is linked with sun imagery (vv. 1b-2), which is also not strange in the ancient Near East, as judgment imagery is in many instances associated with the sun (see Wilson 2002:759).

34 See Craigie and Tate (2004:364-365).

35 For Terrien (2003:398-399), the "salvation of God implies an ultimate destiny, whether in the realm of terrestrial existence or within an eternal transfiguration of life in the company of God." What is expected is a transformation of the body through the salvation of God. When that transformation happens, the meaning of the covenant relationship is there and proper sacrifices can take place.

36 According to Craigie and Tate (2004:367), the covenant relationship between God and his people covered every aspect of human existence and at some time or point in history, needed to be renewed. This included specific rituals and sacrifices. This was for the people to remember their part in the covenant, not for God, as God was always faithful. The ceremonies are not the core of the covenant, rather the covenant is there as a reminder that what God seeks is thanksgiving (vv. 14,23 - תודה), as thanksgiving testifies to lives lived in joy and on the path of God (v. 16). For a further discussion on the use and meaning of thanksgiving in sacrifices within the Psalms, see Courtman (1995:41-44).

37 The superscription of Ps 51 provides a historical context with 2 Sam 11-12, where the narrative reports the affair of David with Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah. In this narrative, David steals another man's wife by committing adultery; he impregnates her and then sends the husband to be slaughtered on the battlefield. Ps 51 points to the section of the narrative where the prophet Nathan confronts David. The penalty for murder is death (Lev 24:17; see Exod 21:12), also for adultery (Lev 18:20; 20:10; see Deut 22:22) (Johnson 2009:27-34). According to Goulder (1990:60), the reason why the one praying is not put to death for his crimes is because he must be the king.

38 See Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:14-15) for arguments for and against the hypothesis for a sick person or penitential psalm.

39 For a further discussion on the importance of this theme in Ps 51 and how it contributes to the process of repentance - penitence - forgiveness - renewal and, reconciliation in the psalm, see Human (2005:114-132). See also Olson (2017:86-96).

40 There is a lot of debate among scholars on how to view the last two verses of Ps 51, as many scholars view them as a later addition to the psalm. It is the positive attitude to sacrifice in vv. 20-21 that is important to take note of. Throughout the entire psalm it becomes apparent that the focus of the psalm is on the personal confession of the psalmist and the petition for forgiveness. In regard to sacrifices, it is mentioned that burnt offerings are not what God is expecting, but rather a sacrifice of a contrite heart and broken sprit. Inward reflection is therefore important. The positive attitude to burnt offerings at the end of the Psalm then does not seem to proclaim the same focus as the rest of the psalm. Ross (2019:607-626), using cognitive linguistic and literary approaches, demonstrates why vv. 20 and 21 should be viewed as part of Ps 51 as part of a conceptual blended network. In his article, he shows that David must be understood as Zion/ Jerusalem and that YHWH as the builder must restore David's (Jerusalem's) damaged walls. When David is purified from sin, he as the king will again facilitate correct sacrifices in Israel (Ross 2019:625-626).

41 On the importance of understanding Ps 51 in its Second Temple context as an example of cult-critical relativisation, see Groenewald (2009:47-62; see also DiFransico 2015:542-557).

42 Hossfeld and Zenger (2005:24) sees Ps 50 as a theophany where the demands God made in the Psalm are answered by the promises made in the prayer by the Psalmist in Ps 51. The placement of the two Psalms next to each other by the redactors of the psalter is reinforced by the shared themes of sacrificial theology, judgment and God that saves (see Pss 50:6//51:6, 16; 50:23//51:14). Even the addition of vv. 20-21 at the end of Ps 51 links with the Zion theme (Ps 50:2), the proper sacrifice (Ps 50:23) and different types of sacrifices listed at the end of Ps 51 with the reference to the bull (Ps 50:9).

43 For a further discussion on the connections between Pss 50 and 51, see Gaiser (2003:382-394) and Polan (2016:89-94).

44 DiFransico (2018:180-187) focuses on understanding the emotional guilt and shame that must have been experienced through the petitions for penitence and how that contributed to the restoration process between the one praying (on behalf of the community) and YHWH. See also Barrett (2017:21-35).

45 See the article of Douglas Jones (1963:24-27), where he argues for a new spiritual movement after the exile in relation to sacrifice and penitence, and the difficulty of sacrifice after the exile. The link also between the Davidic figure as representative of the community of Israel is indicated in this article.

46 Gaiser (2003:388-389) made a further valuable contribution by indicating a concentric structure of Pss 50-51 based on verbal links (this is a direct representation of his structure): A 50:2, 5 Out of ZION...a covenant with me by SACRIFICE B 50:8 your BURNT OFFERINGS are continually before me C 50:9 I will not accept a bull from your house D 50:15 call on me...I will deliver you, and you shall glorify me E 50:18-20 recitation of Decalogue F 50:20 You slander your own MOTHER'S child G 50:22 call to repentance: you who forget GOD H 51: superscript Nathan's oracle (the turning point) G 51:1 prayer of repentance: have mercy on me, O GOD

47 See Courtman (1995:49).

48 See Courtman (1995:51).

49 This idea is also supported in the work of Bell (2018:70-72) with his explanation on the vocabulary for Holiness in the book of Psalms. Holiness, according to Bell, must firstly be understood as an attribute of God, so as to allow us to understand the difference between divine and non-divine. This is the concept that is reflected in Lev to be holy, according to the worldview of P. The outcome of not being holy is separation, between YHWH and His people. Bell (2018:7276) further identifies seven propositions on holiness in the Psalms. One of these is that "God's holiness involves His action of deliverance for his saints" with specific reference to Ps 51:13, where the petitioner appeals to God not to take away his Holy Spirit, not to separate them. If the Spirit is still with the one praying, cleanliness is confirmed.

50 If it is high-handed sin, inadvertent sin or non-defiant sin. See Hossfeld and Zenger's (2005:19), discussion on the vocabulary of sin and an explanation of sin in Ps 51. In this explanation, Zenger indicates that the words the petitioner is using are not only outward descriptions of sin, but also an inward description to appeal to God's forgiveness.