Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 supl.32 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup32.18

ARTICLES

Transforming Presence: Seeing God's body in Books I and II of Psalms

C. Brown Jones

Associate Pastor, King's Cross Church, Tullahoma, Tennessee, USA; Research Fellow, Department of Old and New Testament Studies, University of the Free State. E-mail: christine@kcc.church; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7669-4067

ABSTRACT

The Book of Psalms contains a significant amount of language and imagery related to the physical and sensing body of God. This article applies two questions to Books I and II of the Psalms. Related to God, what body language and imagery exist in these books? What might we make thereof? After a brief consideration of method, the article summarises the body language specific to God in Books I and II. Both books include several references to various parts of God's head and to God's arms, while there are fewer references to other body parts. Next, the article discusses the ways in which anthropomorphism may inform the reading of such language. Understanding the body and body language necessitates an understanding of the culture that produced the language. The references to God's head and hands in Psalms correspond to a broader ancient Israelite emphasis on God's communication and action.

Keywords: Psalms, God, Anthropomorphism

Trefwoorde: Psalms, God, Antropomorfisme

1. INTRODUCTION

At the 2011 meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, in a session on the Book of Psalms dedicated to examining the impact of the work of Gerald Wilson, Jacobson (2011; 2014:231246) presented a paper, titled "Imagining the future of Psalms studies", in which he suggested that research on Psalms might find interdisciplinary scholarship a fruitful avenue for continued pursuit, and mentioned embodiment, in particular. Jacobson (2014:244) suggested that the Psalms refuse to abstract "our 'selves' and our 'minds' and our 'ideas' from our bodies". Given the concentrated occurrences of body terms and images, the Psalms are a likely place to apply embodiment studies. Jacobson's suggestion motivated this study of body in the Psalms. As Jacobson noted, there is no shortage of such terminology nor of approaches to the scholarship of human or divine embodiment.

In light of such abundance, this article focuses mainly on God's body and anthropomorphism. This article also represents research limited to the first two books of the psalter and pursues two questions. Related to God, what body language and imagery exist in these books? What might we make thereof? After a consideration of method, the article summarises the findings from Books I and II and discusses the ways in which anthropomorphism may inform the reading of such language.

2. METHOD AND SCHOLARSHIP

A significant portion of this article focuses on compiling information regarding body language and imagery as it relates to God. Such information is essential for exploring the implications of the use of this language in Books I and II. It is important to note that, although the psalmist refers to animal bodies (Schellenberg 2014:166), this study focuses on the references to human body parts. Combing through these 72 psalms for the various words that indicate human body parts required reading and re-reading the text and making countless charts. The range of meaning of several "body" words, such as face or nose, complicate this task in ways described below.

In "Body images in the Psalms", Gillmayr-Bucher (2004) notes that there are over a thousand explicit references to the body or its parts in 143 psalms. The average number of body parts named in each of these psalms is 5.7 (Gillmayr-Bucher 2004:302). In her accounting, Gillmayr-Bucher considers direct body language such as "ear" and more indirect language such as hearing, which requires an ear, as explicit language. Together, the body language and imagery create a fairly complete image of the human body (Gillmayr-Bucher 2004:303), while language about God's body seems to consist mostly of the head and chest (Gillmayr-Bucher 2004:304).

Although important for gaining an understanding of the scope of body language and image, such a lexical accounting of God's body parts should not minimise the artistry and creativity of the biblical poets.

The psalmists were poets, liturgists, and musicians. Their hymns and prayers are not simply ideological constructs designed to mask sociological realities or statistical word fields for the lexically inclined. The Psalmists were masters of word and image, and their poetry reflects, foremost, the mosaic of Israel's faith (Brown 2002:15).

It is hoped that this accounting of word usage will bring God's body into focus, while allowing insight into the world of the poet and the poet's faith.

It may be interesting and helpful to have a solid understanding of the body language and imagery present, but other questions remain. Why did the psalmists so often choose body language and imagery to describe God? What are we to make thereof? Several avenues could be explored - metaphor, metonymy, or other literary methods. This article, however, pursues these questions through the concept of anthropomorphism. In her book entitled "When Gods were men": The embodied God in biblical and Near Eastern literature, Hamori (2008:26) defines anthropomorphism as referring to divine physicality using human terms. Hamori (2008:29-33) provides a helpful discussion of a variety of anthropomorphisms that serve different literary and theological purposes, some of which appear later in this article. Hamori recognises the tension created in the Hebrew Bible by a robust use of anthropomorphism, on the one hand, and a repeated emphasis that God is not like human beings, on the other. She argues that many early theistic doctrines, under the influence of Greek philosophy, downplayed or rejected out-right anthropomorphic depictions of God (Hamori 2008:34-35).

Likewise, Sommer takes the anthropomorphism of the Hebrew Bible seriously. Sommer (2009:1) begins his book, The bodies of God and the world of Ancient Israel, with this definitive statement: "The God of the Hebrew Bible has a body." Furthermore, he argues that this body is manifest in many places and in various forms. Sommer (2009:3) defines body as something located in a particular time, whatever its shape or substance. The fact that God has a body does not limit God's knowledge or influences to a singular space. Sommer (2009:8) notes that many scholars overlook, minimise, or deny God's body, especially when they view anthropomorphism as merely metaphorical. Sommer prefers to take such language at face value rather than limiting it to the figurative.

Similarly, in his work entitled Where the Gods are: Spatial dimensions of divine anthropomorphism, Smith explores the spatial aspects of anthropomorphism. Smith (2016:1) notes that, in the ancient Near East, the sense of the divine was regularly mediated through places, texts, and artistic forms. Divine spaces such as temples foster communication between the deity and human beings; this communication mirrors human to human communication; thus, deities reflect human characteristics (Smith 2016:5). Anthropomorphism serves as a kind of cognitive model upon which human beings may build their understanding of an unseen deity (Smith 2016:7-8). On the basis of the anthropomorphic language of the Hebrew Bible, Smith (2015; 2016) describes three types of divine bodies: a natural human body, a superhuman-sized liturgical body, and a cosmic or mystical body.

Although Wagner (2019) recognises the potential danger of anthropomorphism, he suggests that a thorough understanding of ancient cultures and their approach to the body helps current readers avoid some of the dangers. In God's body: The anthropomorphic God in the Old Testament, Wagner investigates ancient Israelite and Near Eastern material objects (stele, scarabs, or seals) and written works that depict bodies. In both material and written sources, the body depicts function rather than form. The anthropomorphic language for God focuses on the functions of communication and action, the features of the Old Testament God (Wagner 2019:136). The use of anthropomorphic language in the Old Testament explains that, although God has similar functions to humanity, God's ability within those functions exceeds that of humankind. Anthropomorphic elements allow people to relate to God, while still emphasising God's divinity.

The assertions made about God immediately create comprehension, conversance and closeness in each person. A direct relationship between God and [human] comes into being. The verbal image of God's body is like a net, thrown out over and over again, refined and cultivated through reception and impact. God remains present, identifiable, a counterpart to humans but not restricted to a cult image (Wagner 2019:137).

Wagner's focus on the ancient understanding of body provides a helpful reminder to resist applying modern cultural assumptions to the Old Testament text.

Admittedly, this focus on anthropomorphism may stretch the imagination of those who have often understood the body language related to God as figurative. In a later section, this article explores how the scholarship of anthropomorphism may transform perceptions of God's body in the Psalms.

3. BODY LANGUAGE AND IMAGERY RELATED TO GOD IN BOOKS I AND II

The broad field of anthropomorphism encompasses more specific terminology regarding God's body (Wagner 2019:2, 30). Anthropopathism focuses on God's feelings, emotions, or impulses. Anthropopragmatism focuses on God's behaviour and action. Since physical descriptions of God often relate to God's feelings and/or behaviours, this article will not make such specific distinctions.

In the accounting of God's body in the Psalms, this work distinguishes between direct and implied body language. References to specific body terms are direct language. For example, "O God, lift up your hand" (Ps. 10:12);1 "Why do you hide your face?" (Ps. 44:25), and "incline your ear to me and save me ..." (Ps. 71:2). I view indirect references, often relating to the sensing or acting body, as implied body language. For example, in Psalm 61:6, "For you, O God, have heard my vows", the sense of hearing implies that God has an ear. Similarly, "he [God] utters his voice, the earth melts" (Ps. 46:7) implies a mouth, and "But the LORD sits enthroned forever." (Ps. 9:8) implies a full body.

Of the direct body parts, two pose an interpretive challenge - face and nose. Face, or פנה, does not always constitute a stated reference to the face. Often face functions as a metonym for God's presence. When prefixed with a preposition it takes on a more spatial meaning of "in front of" or "before". This count does not include occurrences of the prepositional usage, although it does include cases of metonymy.

Nose or אף poses a similar challenge, as it may also mean the more specific nostril, the more general face, or even anger. While there is a clear difference in translation between nose and anger, I have included the occurrences that clearly mean anger (Pss. 2:12; 7:7; 69:25). The early readers and hearers of the text would have understood the connection between the emotion and the body part, and they should thus be included in this instance.

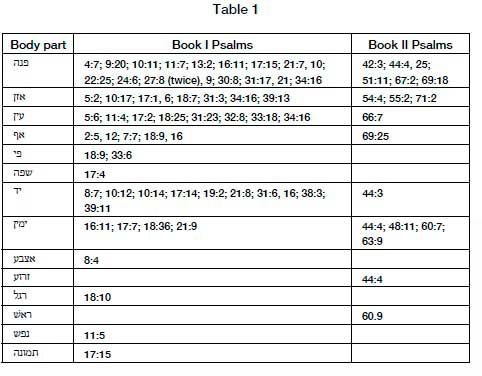

3.1 God's body in Book I

By this count, 24 psalms in Book I contain at least one instance of direct body language in reference to God. Table 1 provides a list of the Hebrew words and corresponding psalms. Another 13 include only implied language related to God's body for a total of 37 psalms. Only Psalms 1, 15, 26, and 36 are without direct or implied references to God's body. However, three of these do contain body language referring to the righteous (Ps. 15) or the enemy (Pss. 26; 36).

The psalmist directly references "face" 18 times. In these occurrences, God's face shines in Psalms 4:7 and 31:17. The righteous will have the opportunity to see God's face (Pss. 11:7; 17:15) and to seek God's face (Pss. 24:6; 27:8 [twice]). The righteous praise God, because God did not hide God's face (Ps. 22:25), while God's face is set against evildoers (Ps. 34:17). Other times, the Psalmist feels that God is hiding God's face (Pss. 13:2; 30:8) or hopes that God will not do so (Ps. 27:9). The enemy assumes that God's face is hidden (Ps. 10:11). In five instances, face, as a metonym, implies God's presence (Pss. 9:20; 16:11; 21:7, 10; 31:21).

Beyond the general reference to face, there are more specific references to head and facial body parts. On eight occasions, the Psalmist directly references God's ears in the nominal and verbal forms of the root אזן. The psalmist implores God to "give ear" in Psalms 5:2, 17:1, and 39:13. Similarly, the Psalmist asks God to incline God's ear in Psalms 10:17, 17:6, and 31:3. In Psalm 18:7, the Psalmist celebrates that his cry reached God's ears. In Psalm 34:16, he acknowledges that God's ears are open to the cries of the righteous.

Similarly, God's eyes, עין, are directly referenced eight times. They are open to the righteous (Ps. 34:16). God's eyes also see the right (Ps. 17:2), recognise the cleanness of the blameless one's hands (Ps. 18:25), and are on those who fear the LORD (Ps. 33:18). God's eye provides guidance in Psalm 32:8.2 At times, the psalmist feels far from God's eyes (Ps. 31:23). God's eyes judge: "the boastful will not stand before God's eyes" (Ps. 5:6). Similarly, "His eyes behold, his gaze examines humankind" (Ps. 11:4).

Filling out the remainder of God's face, the psalmist references God's nose, אף, four times and God's mouth, פי, twice. Psalm 18 references God's mouth in verse 9 and God's nostrils in verses 9 and 16. All three references reflect a vivid theophany of deliverance that occurs as a result of the psalmist's cry for help. In a drastically different image, Psalm 33:6 rejoices over the creative power of God's mouth that uttered words resulting in the creation of the heavens. Psalms 7:7 and 2:12 refer to God's anger in the word אף. There is one reference to God's lips, שׂפה, in Psalm 17:4.

References to God's hands make up the second most frequently occurring body part. In this category, I include both the more general יד, "hand"; the more specific ימין, "right hand", and אצבע, "finger". Psalms 8 and 19 recall the creative works of God's hands (Pss. 8:7; 19:2) or fingers (Ps. 8:4). In Psalm 10:12 and 14, the Psalmist hopes that God's hands might bring justice to the oppressed. In Psalm 31:6 and 16, the Psalmist hopes that God's hand might provide deliverance. God's hand brings judgement upon the enemy in Psalms 17:14 and 21:9 and upon the psalmist in Psalms 38:3 and 39:11. God's right hand provides guidance in Psalm 16:11, refuge in Psalm 17:7 and protection in Psalm 18:36. In Psalm 21:9, God's right hand has the capacity for discernment as the Psalmist declares, "your right hand will find out those who hate you". In Psalm 20:7, God's right hand is victorious.

Body parts beyond the torso also appear, including a reference to God's feet, רגל (Ps. 18:10), soul, נפש (Ps. 11:5), and form or likeness, תמונה (Ps. 17:15), which can be understood as a direct reference to body (associated with kind/species). Together, these occurrences total 60 direct references to God's body parts in Book I.

In terms of the implied references, as mentioned earlier, many have to do with God's senses and actions. In Book I, God's sense of hearing dominates, followed by God's sight. Regarding actions that imply a body, the hands dominate. Often, the psalmist describes God wielding weapons - shield, sword, bow and arrow, spear and javelin - which implies that God has hands and arms. Taken together, the direct and implied references to God's hand make it the most referenced body part in Book I. In several other psalms, the references to God sitting or rising up imply a full body, and references to speech, voice, and command imply a mouth.

3.2 God's body in Book II

Book II of the Psalter contains 31 psalms, all of which include at least one reference to a body. However, references to God's body appear less often than in Book I. Ten psalms of Book II contain at least one direct reference to God's body. Table 1 provides a list of the Hebrew words and corresponding psalms. An additional 15 psalms contain only implied references, for a total of 25 psalms with references to God's body. For the sake of comparison, that is approximately 80 per cent of the psalms of Book II versus 90 per cent of the psalms of Book I. In both cases, implied references outnumber direct references.

As in Book I, the direct references in Book II most often relate to the face and hands. The psalmist directly references the face six times in Book II. In Psalm 42:3, the psalmist desires to see the face of God. In Psalm 44:4, the psalmist credits the light of God's face for Israel's victory and, in Psalm 67:2, the psalmist hopes that God's face will shine upon them. The remaining references relate to God hiding God's face. While Psalm 44:25 asks why God hides God's face, in Psalm 51:11, the psalmist actually requests God to hide God's face, not from the enemy, but from the psalmist's sins. By contrast, the psalmist pleads that God does not hide God's face in Psalm 69:18. There are no metonymical references to face in Book II. The word 'לפני is used six times and מפני once in regard to being before God. Four of these uses appear in the context of theophany, once in Psalm 50 and three times in Psalm 68, making them somewhat tricky. As per the decision not to include the prepositions, they are not included in the table.

Moving to more specific parts of the face/head, the psalmist references God's ears three times, twice in verbal form, "to give ear", and once in nominal form. In Psalms 54:4 and 55:2, the psalmist asks God to give ear to his prayers for help against the enemy. Psalm 71:2 asks that God incline God's ear and rescue from the enemy. The psalmist mentions God's eyes once, in Psalm 66:7. In this psalm, God's eyes keep watch over the nations, lest the rebellious ones think they can act up. Rounding out the face, there is one direct reference to God's burning nose, or anger, in Psalm 69:25. There are no direct references to God's mouth, tongue, or lips, although they certainly are implied approximately 11 times.

The remaining direct references in Book II relate to God's arm and hand, with half of these references found in Psalm 44. Verse 3 celebrates how God's hand (יד) drove out nations and planted the people. Verse 4 reminds the people that it was by God's right hand (ימינ) and arm (זרוע), not their own that they won the land. Two more psalms reference God's right hand. Psalm 60:7 associates God's right hand with victory and Psalm 63:9 associates it with God's firm support.

Implied references far outnumber the direct references in Book II. God has a voice, calls, speaks, laughs, gives commands, and answers, all of which imply a mouth. God hears and listens or not, suggesting ears. God sees, looks, and watches with implied eyes. In actions that assume hands, God shoots, girds, washes, crushes, tears, scatters, shatters, opens, casts down, and takes from the mother's womb. God marches, tramples, and treads with God's implied feet. God sits, cringes, bows, and visits with God's implied body.

While Book II does not paint as complete a picture of God's body as Book I, God's face and torso are well represented in the direct and implied language. While references to God's body are not as frequent in Book II, it is interesting to note an increase in psalms highlighting the psalmist's body, including, but not limited to Psalms 44/43, 51, 57, 63, and 69. The enemy's body remains prevalent. It is interesting to note that, in Book II, God is more frequently associated with non-human objects such as rock, fortress, and refuge than in Book I.

4. ANTHROPOMORPHISM

With the question of what body language appears in Book II resolved, the article now turns to the second question: "What might we make thereof?". Several scholars have noticed the Psalmist's use of body language and imagery related to God. Keel's (1997:8) use of ancient Near Eastern iconography helps readers imagine the psalms and "compels us to see through the eyes of the ancient Near East", rather than the modern world. Brown's Seeing the Psalms (2002) explores a variety of metaphorical source domains in relation to God's body. He explores God's senses, face, hands, mouth, voice, and breath or wind. Brown (2002:182) states, "Poets map the divine with a degree of 'physiological hyperbole' to highlight God's activity and effectiveness." Like Hamori and others, Brown (2002:167-169) notes the tension between God's distinctiveness from humanity and the many anthropomorphic images with which the psalms refer to God.

Assuming Smith's (2016:1) assertion that our view of the divine is often created through places, text, and artistic form, it makes sense that the Psalms would contain a significant amount of anthropomorphism. Many authors of psalms likely participated in the liturgical life of the cult, experiencing worship spaces, creating texts, and performing rituals. Human communication became their primary cognitive model for participating in divine communication. That model easily turns into describing God through anthropomorphism. They assume that God sees, hears, talks, smells, sleeps, sits, and stands, just as they do. They also readily notice that the deity is not like them. God does not get ill or hungry, and God does not die (or at least remain dead).

The catalogue of direct and implied body language used of God in Books I and II of Psalms aligns well with Wagner's research into anthropomorphism. God's face and hands feature prominently in the Psalms. In Wagner's extensive research, God's face and hands are mentioned far more often than other parts of God's body (Wagner 2019:119). The references to God's body in the Psalms also focus most often on functions of communication and action. In the absence of the tangible presence of God, the psalmist creates a verbal presence that fulfils God's primary functions in relation to humankind.

Of the various works on anthropomorphism,3 I find Hamori's types of anthropomorphism helpful when exploring God's body in the Psalms. Hamori (2008:28-33) defines five types of anthropomorphism:

• Concrete anthropomorphism: The concrete, physical embodiment of the deity. An example would be God walking in the Garden in Genesis 3.

• Envisioned anthropomorphism: Experiencing the deity in a vision or dream, without an earthly experience; some of Ezekiel's visions fit in this category.

• Immanent anthropomorphism: An expression of the closeness or presence of the deity without physical embodiment or with limited physical embodiment. Job's encounter with God in the whirlwind would fit this definition.

• Transcendent anthropomorphism: An anthropomorphic description of the deity who is located in the heavens, for instance God being enthroned in heaven.

• Figurative anthropomorphism: Representational language referring to the deity.

Figurative anthropomorphism may overlap at times with the other types, but it remains distinct. Hamori cautiously associates this type with metaphor. It is symbolic, but she does not want to dismiss the language as merely metaphor. Sommer echoes Hamori's caution regarding metaphor, asking:

Should we take the anthropomorphic statements of the Bible as mere metaphor? Did these ancient authors mean precisely what they said, or did they use anthropomorphic language for some other reason?

An understanding of metaphor, metonymy, or synecdoche and other similar language as a type of cognitive linguistics that helps readers and hearers organise and make sense of varied information may help us avoid treating figurative anthropomorphism as "mere" metaphor.

According to Hamori (2008:26),

while anthropomorphism in a general sense is unavoidable, the use of specific types of anthropomorphic depiction, including physical embodiment, is certainly avoidable.

That is to say that, in this instance, the Psalmist did have various options available. As noted earlier, popular options in Book II include rock, fortress, and refuge. Appreciating the options and the choices may make us more informed readers.

Of the five types of anthropomorphism, immanent, transcendent, and figurative seem to apply most often in Books I and II of the Psalter. For example, Psalms 29 and 68 express ideas of immanent anthropomorphism. Psalm 29 expresses ideas of immanent anthropomorphism as it describes the Lord's voice over the waters (vv. 3-4), breaking cedars (vv. 5-6), shaking the wilderness (vv. 7-8), and stripping the forest bare (vv. 9-10). The Lord's powerful voice reveals the Lord's presence in the land and yet, no physical body appears in these verses. The Lord's immanent presence demonstrates strength. In Psalm 68, God's immanent presence brings judgement. The enemies bear the brunt of God's judgement in Psalm 68, when God, the one who rides in the clouds (vv. 5, 34), comes into his sanctuary in Jerusalem (vv. 6, 25, 36). The earth responds with quaking and the heavens with rain (vv. 9-10). In this instance, the psalmist recalls God marching through the wilderness (v. 8), commanding armies (v. 12), scattering kings (v. 15) and enemies (v. 22), and participating in processions (vv. 19, 25-26).

Psalm 33:13-15 presents the clearest transcendent anthropomorphism in Book I:

The LORD looks down from heaven; he sees all humankind. From where he sits enthroned, he watches all the inhabitants of the earth - he who fashioned the hearts of them all, and observes all their deeds.

This anthropomorphic description of God aligns well with Smith's understanding of God's cosmic "mystical" body (Smith 2015:482-484). This body resides in the heavens rather than in the Temple or Zion. God's heavenly vantage point allows for easy observation of all the earth. In contrast to the cosmic body of Psalm 33, in Psalm 9, the Lord who sits enthroned (v. 8), dwells in Zion. While God judges the world from this throne, the vantage point seems more limited.

Perhaps Psalm 47 presents an example of transcendent anthropomorphism in Book II. This psalm celebrates God's worldwide rule. "The Lord, the Most High" is the great king over all the earth (v. 3). As king, God sits on God's holy throne (v. 9). Although the psalm does not mention the location of the throne, it does use language that sets God apart from or over the people. People are subdued (v. 4), while God goes up (v. 6) and is exalted (v. 10).

Two examples of figurative anthropomorphism include the midwife nurse images in Psalms 22 and 71. In Psalm 22:10-12, the implied hands of God that delivered the baby and placed her at the mother's breast represent a rare feminine example of anthropomorphism in the Psalms. In the symbolic reference to God as midwife, the psalmist reminisces about God's former closeness and longs for such closeness to return. Psalm 71:6 also contains a brief metaphor of God as midwife. "Upon you I have leaned from my birth; it was you who took me from my mother's womb." In the symbolic reference to God as midwife, the psalmist celebrates an ongoing, life-long commitment to God.

5. CONCLUSION

Of the 72 psalms of Books I and II, 62 directly or indirectly reference God's body. This article provides a detailed catalogue of God's body. Although a complete image of God's body does not appear in the direct language, God's body communicates and acts powerfully in these psalms. While much of biblical scholarship has approached this language figuratively, this article has considered implications of a more robust anthropomorphic understanding of this language. Taking into consideration the cultural implications of anthropomorphism in the ancient world allows for a transformed and transforming image of God's presence to appear through these psalms.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brown, W.P. 2002. Seeing the Psalms. A theology of metaphor. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. [ Links ]

Gillmayer-Bucher, S. 2004. Body images in the Psalms. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 28(3):301-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030908920402800304 [ Links ]

Hamori, E. 2008. "When gods were men": The embodied God in biblical and Near Eastern literature. Berlin: De Gruyter. BZAW 384. [ Links ]

Jacobson, R. 2011. Imagining the future of Psalms studies. San Francisco, CA: Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting. [ Links ]

Jacobson, R. 2014. Imagining the future of Psalms studies. In: N.L. deClaisse-Walford (ed.), The shape and shaping of the book of Psalms: The current state of scholarship (Atlanta, GA: SBL Press), pp. 231-246. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt9qh23j.20 [ Links ]

Kamionkowski, S.T. 2010. Introduction. In: S.T. Kamionkowski (ed.), Bodies, embodiment, and the theology of the Hebrew Bible (London: T. & T. Clark), pp. 1-10. [ Links ]

Keel, O. 1997. The symbolism of the biblical world: Ancient Near Eastern iconography and the Book of Psalms. Translated by T.J. Hallett. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns. [ Links ]

Moore, S.D. 1996. Gigantic God: Yahweh's body. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 21(70):87-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030908929602107007 [ Links ]

Sohellenberg, A. 2014. More than spirit: On the physical dimensions in the priestly understanding of holiness. Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 126(2):163-179. [ Links ]

Smith, M.S. 2015. The three bodies of God in the Hebrew Bible. Journal of Biblical Literature 134(3):471-488. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jbl.2015.0033 [ Links ]

Smith, M.S. 2016. Where the Gods are: Spatial dimensions of anthropomorphism in the biblical world. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Sommer, B. 2009. The bodies of God and the world of Ancient Israel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Wagner, A. 2019. God's body: The anthropomorphic God in the Old Testament. Translated by M. Salzmann. London: T. & T. Clark. [ Links ]

Date received: 30 November 2020

Date accepted: 05 August 2021

Date published: 10 December 2021

1 The Psalm versification noted is from the Masoretic Text. Some verse numbers will be different in English translations.

2 Ambiguous speaker, it could be the eye of the psalmist.

3 Many authors have explored anthropomorphism (Kamionkowski 2010; Moore 1996; Smith 2015, 2016; Sommer 2009; Wagner 2019).