Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Acta Theologica

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9089

versão impressa ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 supl.32 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.sup32.9

ARTICLES

COVID-19 pandemic as a socio-psychological influence on transformations in religion

Y. GavrilovaI; E. ZakharovaII; M. LigaIII; M. ZhironkinaIV; A. BarsukovaV

IPhD, Department of Sociology and Cultural Studies, Bauman Moscow State Technical University, Moscow, Russian Federation. E-mail: yulia_gavrilova@rambler.ru

IIDepartment of Philosophy, Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russian Federation

IIIDepartment of Social Work, Transbaikal State University, Chita, Russian Federation

IVDepartment of Psychology, Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Moscow, Russian Federation

VDepartment of Social, Psychological and Legal Communications, Moscow State University of Civil Engineering (MGSU) National Research University, Moscow, Russian Federation

ABSTRACT

This article aims to establish COVID-19's socio-psychological influence on religion. This interdisciplinary study's theoretical framework embraces the social-ecological systems framework, the concept of deprivation, the theory of religious myth-making, religious individualism and bricolage, as well as the concept of quality of life. A sociological survey was conducted of 4,700 residents of Moscow and the Moscow region. The results revealed that the social sphere of society was relatively stable during the pandemic. Exploring COVID-19's socio-psychological influence, this study examines transformations in religion that resulted from tactile deprivation.

Keywords: Religion, COVID-19, Deprivation, Religious bricolage

Trefwoorde: Godsdiens, COVID-19, Ontneming, Godsdienstige bricolage

1. INTRODUCTION

The world is currently plunged into such deep crisis that people across the globe become overly pessimistic about the future of society. The coronavirus outbreak has affected all spheres of life. Scientists discussed the catastrophic implications of the virus, whilst theologians suggested a range of new interpretations of divine providence, referring to prophecies about events such as the COVID-19 infection (Gallegos 2020; Marshal 2020; Ramzy & McNeil 2020; Rob et al. 2020:4).

The overall public attitude towards the situation is rather negative. Scholars, politicians, economists, religious figures, believers, and ordinary people living without a commitment to any ideas and principles experience panic attacks as well as inadequate emotional and sensory reactions to what is happening in the world. Apocalyptic fears, eschatological expectations, and thanatophobia are on the rise (Li et al. 2020:E2032). Such a response is the result of worldwide mass COVID-19-related deaths.

In January 2020, WHO officially declared the COVID-19 outbreak a public health emergency; soon thereafter, it was called a global pandemic (CDC 2020; Ramzy & McNeil 2020). It seems thus that the wave of panic swept across the world after several million confirmed cases and after the WHO acknowledged the threatening spread of the disease. The essence of this effect is multifaceted. As a socio-psychological response of society, it manifests in damage to the individual's psyche, engendered by the emergency measures taken to stabilise the political, economic, and social spheres of life. A factor that accompanies and enhances COVID-19's influence is the existential uncertainty. The merging of these two drivers blurs the boundaries of our perception of events. An opinion has been increasingly expressed that religion can play a decisive mitigating role at all levels of the pandemic's influence. At the micro-level, religious leaders may offer people spiritual and material assistance, while at the macro-level, religious organisations can contribute towards resolving broader socio-economic problems caused by the crisis (Bentzen 2020). Under such circumstances, hoping for supernatural help becomes a mainstream.

All levels of religious consciousness (individual, social, day-to-day, and conceptual) turned out to be highly sensitive to the pandemic. Representatives of various faiths, engulfed in psychological tension and apocalyptic fears, engaged in myth-making. Some traditional religious images underwent subjective rethinking against the background of increased religious bricolage. The changes primarily affected the individual religious consciousness; but the religion industry was also endangered. Religions managed to adapt to new social conditions in time, thereby embarking on an unprecedented change: religious services and sermons were either cancelled or preached remotely, using broadcasting networks.

Learning about COVID-19's socio-psychological influence on religion may help find ways to reduce social tension through faith and to restore a safe social environment. The church has strongly influenced public opinion and social behaviour in the past and this continues to affect contemporary society. Hence, the exploration of the negative effects of the pandemic will lay the ground for the prevention of secular-religious confrontations and schisms within the church.

This article aims to establish the role of the COVID-19 pandemic in religious transformations. The article consists of four sections. The first section of the study explains the need for an interdisciplinary approach towards the analysis of COVID-19's socio-psychological influence and provides insight into the basic concepts and methods necessary to identify the role of the pandemic in religious transformations. The second section focuses on the influence of lockdown measures on the mental state of believers. In this instance, the section characterises the socio-psychological essence of deprivation and its role as a socio-natural mechanism of religious transformation. It also addresses the psychological aspects and trends of religious myth-making and religious bricolage. The third section of the study explores the relationship between one's quality of life and one's subjective well-being under conditions of psychological tension caused by the pandemic. An analysis of the survey results determined a range of COVID-induced concerns and sociocultural factors influencing social security. The key facts on COVID-19's influence on religion conclude the study.

The work discloses the social-ecological nature of the pandemic. The results of the study cover the general knowledge of the natural and social factors of religious transformation as well as the understanding of interactions between social and natural systems.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Theoretical framework

This study is based on five conceptual pillars, namely social-ecological systems framework (Gavrilova et al. 2018:231; Muhar et al. 2018:756; Subbotina 2001:15); religious individualism and religious bricolage (Léger 1987:11); religious myth-making (Neal & Youngelson-Neal 2015:32; Zhukov & Bernyukevich 2018:10003); the concept of "deprivation" (Norris & Inglehart 2011:34; Stark 2015:11), and the concept of "quality of life" (Liga 2006:22; Skevington & Böhnke 2018:22).

The socio-ecological systems framework (interactions between social and natural systems) is a basic concept to identify, classify and analyse factors influencing the formation and transformation of religions. The social refers to something that belongs to, and is generated by and within society, whereas "natural" relates to natural systems, natural properties, and natural laws (Subbotina 2001:12). The natural is divided into external and internal natural systems. External natural systems have not been subjected to anthropogenic and sociogenic effects. Internal natural systems refer to a human body, one's psyche, natural needs, instincts, and reflexes. The external and internal natural systems are closely interconnected and define a variety of processes, social included.

Religious bricolage permits the exploration of the psychological, subjective nature of religions. Addressing this concept makes sense, as a new type of religiosity is emerging - "personal religiousness", which is not bound to doctrinal attitudes and does not recognise closure and exceptionalism (Léger 1987:15).

The theory of religious myth-making indicates that social events play a key role in religious transformations. Religious myths are constructed and interpreted under the influence of social reality. Nowadays, religious myth continues to perform a range of functions that are vital in preserving society as a structure (Zhukov & Bernyukevich 2018:10003).

Restrictive measures aggravate the negative psychological influence of COVID-19. The lockdown has induced deprivations that define the socio-psychological consequences of the pandemic. The concept of deprivation explains the link between various kinds of deprivation and transformations in religion, including religious myth-making and religious bricolage. Deprivation diversity provides the framework for exploring the newly emerged types of deprivation associated with the pandemic (Stark 2015:12).

To establish COVID-19's role in social destabilisation, one should turn to the concept of "quality of life" (Liga 2006:5). Quality of life is defined as an individual's satisfaction regarding his needs and style of life. This measure is a composite construct that drives social development. Quality of life depends on social security and vice versa. For instance, a population's quality of life strongly influences social security. However, a decent quality of life results from strong and sustainable social security (Skevington & Böhnke 2018:27).

The framework for an analysis of COVID-19's influence comprises philosophical, psychological, religious, and sociological concepts. It allows for a closer scrutiny of the pandemic and its role in transforming religions from the socio-psychological perspective.

2.2 Methodological framework

As stated earlier, this study uses the socio-ecological systems framework approach (Subbotina 2001:35) to explore how the external natural system (the COVID-19 virus) affects the internal natural system (the human psyche), thereby activating alterations in the social system (for instance, change of social consciousness and social practices). This principle throws light upon the natural grounds of social processes and reflects the socio-psychological influence of the pandemic as well as its role in transforming religion.

The empirical data was collected, using a sociological survey conducted by a "Sociology of the Quality of Life" Laboratory within the framework of the Quality of Life research under the guidance of the author (Liga 2006:12).

2.3 Research design

The empirical data reported in this study constitute part of the research entitled "Satisfaction with quality of life as an indicator of social security". The major stage of that study took place in November/December 2019 and focused on identifying the relationship between quality of life and social security.

The research hypothesis is that the sociocultural environment that has changed under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic has a negative influence on the subjective well-being of individuals and may result in a disruption in the social security system.

The survey questionnaire consisted of 21 questions concerning the following dimensions of the quality of life framework: socio-ecological systems framework, satisfaction/anxiety regarding the limited access to religious items, satisfaction regarding physical and mental health, subjective sense of life security, and overall experience of life. The questions enabled the researchers to measure the sociocultural quality of life appreciation as an indicator of social security. Respondents were asked to identify what bothered them during the lockdown, by selecting either of the answer options related to all spheres of social life, including spiritual. All questions touched on the basic sociocultural dimension of quality of life, in other words, the axiosphere (religious values and access to them).

2.4 Sample and survey

The study population included residents of Moscow and the Moscow region, aged over 18 years. Participants were selected regardless of gender, education, social status, and religion to investigate the relationship between COVID-19-induced changes to the religious life of people (limited access to religious items and places of worship) and their social well-being. Study participants were recruited through random sampling. The target sample included both representatives of various faiths and individuals who did not belong to any religion.

2.5 Data analysis

The sociological data was processed, using the SPSS software. The results, presented in the form of linear and paired distributions, reflect quality of life satisfaction as an indicator of social security.

The survey involved 4,700 residents of Moscow and the Moscow region (95% CI, ± 5%).

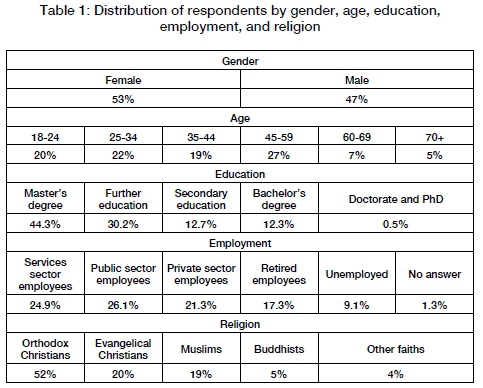

The vast majority (53%) of the respondents were women. Respondents aged between 45 and 59 years (27%) were in the lead, with 5% of the respondents older than 70 years. Most of the respondents have higher education. Representatives of various professions took part in the survey: civil servants and service-sector employees accounted for the vast majority of the respondents. In terms of religion, 52% of the respondents are Orthodox Christians, 20% are Evangelical Christians (Protestants), 19% are Muslims, and 5% are Buddhists.

Table 1 shows the respondents' socio-demographic profile.

2.6 Research limitations

The quantitative research toolkit is rather limited. The actual number of questionnaire items did not allow for the most accurate estimation of the sociocultural influence on overall quality of life. This narrows down the analysis of religious transformations to bricolage, syncretism, and myth-making. The study sample was composed of representatives from religious denominations living within a specific territory. The research did not include adherents of various minor religions and Eastern-oriented cults.

The central research limitation is the respondents' uncertainty in terms of individual religiosity and the institutionalisation of religious faith. Numerous factors, including those of a religious nature, but not mentioned in this study, influence the subjective assessment of one's own well-being.

2.7 Ethical issues

The study was conducted by the "Sociology of the Quality of Life" Laboratory, Chita. The authors of this article are employees of the Sociology of Quality of Life Laboratory at Transbaikal State University. All respondents were informed of the aim of the survey, the voluntary nature of their participation, the confidentiality and anonymity of records. They were also informed that their refusal to participate will not result in any negative consequences. Respondents were allowed to skip any item on the survey if s/he was unwilling to provide answers.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Deprivation as a socio-psychological mechanism for transformation in religion

The deadly coronavirus spreads to people of different age and social groups, forcing the propagation of social distancing. Individuals are restricted from meeting specific social needs, in order to keep their own organism and its vital functions intact. Social distancing and isolation are the best ways to achieve this goal. This gives rise to deprivations, a socio-psychological mechanism of transformation in religion.

The state of deprivation refers to the situation in which a person is kept from his/her sources of satisfaction and thus not able to meet his/ her basic mental needs for a long time. In many religions, deprivations are viewed as something that has the potential to purify one's soul and body. This applies to voluntary deprivations only. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people were told to stay isolated at home, in order to avoid catching the deadly virus. The emotional and intellectual consequences of forced deprivation in spiritual experience may be deep and traumatic. Whether these implications will be positive, negative, or neutral depends heavily on how a person perceives the situation. Thus, deprivation is a social response that results from natural circumstances and manifests in changes in behaviour, in individual and social consciousness, and in social structure.

During the pandemic, believers were deprived of speaking with God (in many religions, such a conversation is only possible in certain places) and of attending sermons. Under these circumstances, many believers may feel guilty for not participating in religious activity. In this study, 17% of the respondents found it difficult to meet religious needs, due to limited access to religious facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite being deeply rooted in faith, some representatives from religious communities tended to adjust their religiosity to the new reality. This suggests that pandemic-induced isolation strongly influenced people's mental health and religious sphere of life.

3.2 Myth-making and psychology behind religious bricolage

In an attempt to explain the emergence and rapid spread of the infection, people dive into the world of myth. The new prophecies, both religious and esoteric, thus gained a great deal of influence on public consciousness. The practice of exploring religious texts for prophecies about COVID-19 became popular among some theologians, members of the clergy, and believers. In most instances, these predictions mention the imminent destruction of humanity, thus provoking anxiety and thanatophobia.

The withdrawal from religious items poses a risk of developing religious bricolage. This phenomenon refers to the construction of religious images, ideas, and religious practices by using those components of religion that are at hand. Religious communities turn to introspective practices, online sermons, and digital means to deliver religious content.

When isolated, a person has the opportunity to self-reflect. Introspection sheds light upon one's deep-seated fears. As the feeling of loneliness escalates, believers tend to the transcendental. One may achieve the transcendental state through praying or chanting. Transcendental meditation as a tool results in a positive emotional experience. The COVID-19 restrictions deprive believers of the opportunity to attend churches and meetings, plunging them into anxiety. This calls for the construction of new models of religiosity. Believers now perform religious rituals at their own places and seek religious texts on the Internet.

The church's loosening of institutional control contributes to the spread of individual beliefs, thus leading to the establishment of religious bricolage, a form of religiosity that does not need to be institutionalised. One would think that, under such conditions, one would lose one's religion and desire to participate in religious services. However, this was not the case. On the contrary, there has been an increase in individual religious efforts.

Religious bricolage driven by fears and mental stress is established unconsciously. The desire to eliminate the contradictions of uncertainty requires believers to undertake active actions. Therefore, they actively "build" their religious reality, using improvised materials from the real and virtual worlds.

For religious bricolage, the access to resources is of particular importance. The social status, income, and quality of life of individuals play a substantive role in receiving these resources. For instance, people of high social status have more access to symbolic resources for the creation of religious homemade items, compared to individuals of middle and lower status. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly limited the access to religious items, placing everyone in the same boat.

3.3 Quality of life and social well-being

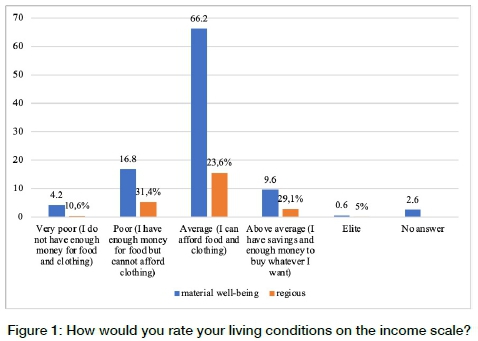

The study explored the following dimensions of subjective life satisfaction: health, material well-being, access to religious items and places of worship, as well as safety (Liga 2006:15; Skevington & Böhnke 2018). Based on material well-being, five groups of respondents have very high (elite), high, average, poor, and very poor quality of life (Figure 1).

Of the survey respondents, 0.6% rated their level of material well-being as elite (Figure 1). Of these, 5% are believers. The percentage of people who rated themselves above average is 9.6%. Of these, 29.1% are believers. Of the respondents, 66.2% mentioned that they have an average level of material well-being. Of these, 23.6% consider themselves religious. These three groups of respondents were totally satisfied with their health, work, life security, and access to religious items and places of worship during the lockdown period (Table 2). The survey also found that, across these three groups of respondents, 17.9% of believers are engaged in bricolage behaviour, 5.7% in myth-making, and 0.3% in religious syncretism. Of all the respondents, 16.8% feel poor and 4.2% feel very poor. In these two groups, believers make up 31.4% and 10.6%, respectively. These two groups of respondents reported suffering from increased levels of stress, emotional disposition, and fears of becoming infected. They also expressed negative attitudes towards home isolation rules and the lack of access to religious items and places of worship. Among the religious respondents in these two groups, 11.5% are engaged in bricolage behaviour; 27% in myth-making, and 1.1% in religious syncretism.

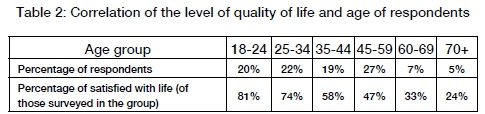

In terms of subjective material wealth, several social groups have elite, sufficient, average, poor, and extremely poor quality of life. The correlation between age and quality of life suggests that young and middle-aged people rate their well-being as average and good, whereas people over the age of 60 years tend to rate their quality of life as poor and very poor.

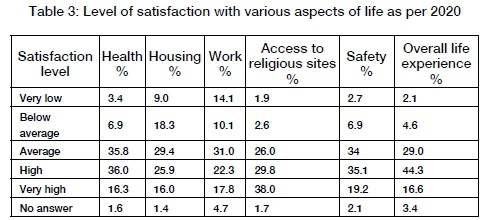

In assessing quality of life appreciation, one should pay attention to influences such as work, housing, access to religious items, safety, and overall life experience. Thus, one's satisfaction depends on the subjective perception of the life space. Table 3 shows the results of the life-satisfaction analysis.

The subjective measure of life satisfaction shows the relationship between overall quality of life and its components. The low quality of life preconditions the low satisfaction with one's own health, housing, work, access to religious items, and safety. By contrast, high and very high quality of life determine high and very high levels of satisfaction with various aspects of life.

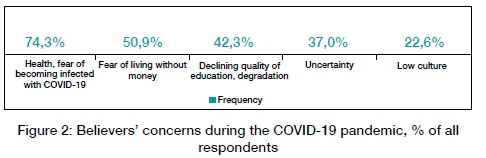

During the study, issues were identified that believers found concerning during the COVID-19 pandemic period, regardless of their material wealth. The most frequent responses were social and socio-psychological challenges such as the fear of being infected with COVID-19, the fear of living without money, the declining quality of education, and the fear of uncertainty. Access to religious sites, on the other hand, was the least of their concerns (Figure 2).

The present findings show that the psychological stress among believers is largely due to the potential deadliness of the spreading SARS-CoV-2 virus. Restrictions on visiting places of worship had relatively little effect on the psychological state of believers. These results contradict the research hypothesis and indicate the existence of socio-psychological tension during the pandemic.

Social and socio-psychological challenges of the pandemic were the most frequent responses: fear of becoming infected with COVID-19; fear of living without money; declining quality of education, and uncertainty. The sociocultural concerns closed the feedback. These results failed to confirm the research hypothesis. However, they succeeded in revealing the presence of socio-psychological stress during the pandemic.

4. DISCUSSION

The results obtained show that contemporary society suffers from mass and individual psychological effects related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic acts at both social and natural levels, which align it with the fundamental preconditions for religion such as the natural-social interactions, the laws of the human psyche, and social alterations. The socio-natural character of the pandemic, which means that COVID-19 exists in both biological and social spheres, enhances its influence on spiritual life. These findings are consistent with other studies exploring the relationship between natural and social mechanisms of social development and their role in social structuring (Gavrilova et al. 2018:234; Muhar et al. 2018:760; Subbotina 2001:14). The use of the socio-ecological systems framework in this study was productive, as it allowed proving the influence of natural premises on social development, thus confirming the interdependence between society and environment. This principle enabled the researchers to identify the socio-natural mechanism of transformations in religion that exists in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This mechanism may be described as follows: the external natural system (COVID-19 virus) affects the internal natural system (human body and psyche), activating the social component (isolation, deprivation, religious bricolage, social contradictions, irrational behaviour, and myth-making). The results confirm the opinion that mechanisms of socio-natural interaction are universal and may be used to examine changes of consciousness and social practices (Gavrilova et al. 2018:240; Kerényi & McIntosh 2020:75; Soga & Gaston 2016:94; Subbotina 2001:12; Sutton 2017:545; Zhukov & Bernyukevich 2018:10003). These findings form the basis for an investigation into how religions develop during outbreaks.

The rapid spread of the disease, social isolation, and crisis resonated with the public mind, evoking fears and mental stress. Such a response became a catalyst for the change of religious consciousness and spiritual practices. This approach is innovative and complements the attempts of scientists to study the socio-psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the behaviour of believers in isolation, and their fears (Holmes et al. 2020:547).

The psychological reaction of society to the COVID-19 pandemic is characterised by mass hysteria, panic attacks, stress, and depression. Those who seek to escape this situation tend to address supernatural forces, as they are not able to predict their own future. This behaviour results in the construction of religious myths. Isolation and deprivation shifted the attention of believers from the abstract essence of God to their own inner world. The transcendental reality supplanted by the subjective reality began to lose its meaning. The results of this study are consistent with research on the post-pandemic transformation of religions in America (Campbell 2020), which described the role of deprivation in strengthening individual religiosity.

The study confirms that religions depend on social events and their reflection in individual and mass consciousness (Lorea 2020; Marshal 2020). To overcome adverse circumstances and allay fears of infection and death, people typically resort to religious myth-making (Bentzen 2020). The interpretation of the COVID-19 pandemic as a sign of the end of times is as comforting as frightening. This way of thinking makes one doubt one's own actions and world view.

The topic of interdependence between religiosity, quality of life and social security remains controversial. This connection exists, and is due to many factors such as psychological stress, fears, access to religious items, security, and so on (Peres et al. 2018:1842). Individuals who report average and above average levels of quality of life are more stable psychologically, as they are confident in the future. Their religiosity is also stable: problems associated with transformations in religion hardly concerned this group of respondents. The more confident and calmer people feel, the less they are in need of aid for protection from the religion. However, the negative influence of public religiosity on quality of life is not ruled out.

In this study, not only the socio-psychological influence of the pandemic was revealed, but some characteristics of religious development were also highlighted. Data available indicates that public stress activated the processes of transformation in the religious environment. Currently, religious transformations related to COVID-19's influence on the spiritual sphere of society are at the nascent stage (Hart & Koenig 2020:2). Perhaps, the recurrence of the pandemic will provoke stronger transformations, but the current changes (for example, a shift to subjectivity and self-discipline, partial loss of the sacred perspective, reshaping of religious subjective experience, and so on) are distinctive enough. Despite the permission to deliver religious services and perform mass rituals, the pandemic retains its influence on religious consciousness. The findings of this study may serve as a framework for future investigation into religion and COVID-19's socio-psychological influence.

5. CONCLUSION

Religion depends on natural determinants such as biological threats to humanity; on social, political, and economic conditions that society may interpret as difficult, and on conflicting public sentiments. Religion's response to the pandemic may be described as transformations in religious consciousness and an effort to produce new impersonal services.

The major result is that COVID-19 preconditions the transformation of religion. The coronavirus provokes stress, numerous fears, increased anxiety, and discrimination on the grounds of infection. It causes increasing mental trauma and hysteria over the meaningful safe life guidelines.

A change in sociocultural conditions influences social well-being and quality of life. The vast majority of the respondents rated their economic and sociocultural aspects of quality of life as average. Over 20% rated their satisfaction with the situation as below average. A small percentage of the respondents gave "high" and "very high" ratings. The results show that respondents with average and higher levels of satisfaction tend to be more dispassionate and coolheaded during a crisis. This group of respondents showed hardly any dependence on religion. Respondents with low level of satisfaction were prone to anxiety and had increased concerns about the withdrawal from religious items. These findings suggest that the social sphere of society persisted, despite the influence of the pandemic.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bentzen, J. 2020. In crisis, we pray: Religiosity and the COVID-19 pandemic. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://cepr.org/active/publications/discussion_papers/dp.php?dpno=14824 [20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Campbell, H. A. 2020. Religion in quarantine: The future of religion in a post-pandemic. [Online.] Retrieved from:https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/18800420 [20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Centers for Disease Control and Preventions (CDC) 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): COVID-19 Situation Summary. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/summary.html [20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

GallegoS, A. 2020. WHO declares public health emergency for novel coronavirus. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/924596 [20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Gavrilova, Y., Shchetkina, I., Liga, M. & Gordeeva, N. 2018. Religious syncretism as a sociocultural factor of social security in cross-border regions. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 21(3):231-245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2018.1460590 [ Links ]

Hart, C.W. & Koenig, H.G. 2020. Religion and health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 15:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01042-3 [ Links ]

Holmes, E.A., O'Connor, R.C., Perry, V.H. et al. 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry 7(6):547-560. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1 [ Links ]

Kerényi, A. & McIntosh, R.W. 2020. Changes on earth as a result of interaction between the society and nature. In: A. Kerényi & R.W. McIntoch (eds), Sustainable development in changing complex earth systems (Cham: Springer), pp. 75-202. [ Links ]

Léger, D. 1987. Faut-il definir la religion? Questions préalables à la construction d'une sociologie de la modernité religieuse/Must religion be defined? Questions previous to the establishment of a sociology of religious modernity. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 63(1):11-30. https://doi.org/10.3406/assr.1987.2418 [ Links ]

Li, S.,Wang, Y., Xue, J., Zhao, N. & Zhu, T. 2020. The impact of COVID-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active Weibo users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(6):E2032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062032 [ Links ]

Liga, M. 2006. Quality of life as the basis of safety. Moscow: Gardariki. [ Links ]

Lorea, CE. 2020. Religious returns, ritual changes and divinations on COVID-19. Social Anthropology 28(2):307-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12865 [ Links ]

Marshal, K. 2020. What religion can offer in the response to COVID-19. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/28789/what-religion-can-offer-in-the-response-to-covid-19 [20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Muhar, a., Raymond, C.M., van Den Born, R.J. et al. 2018. A model integrating social-cultural concepts of nature into frameworks of interaction between social and natural systems. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 61(5-6):756-777. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1327424 [ Links ]

Neal, A.G. & Youngelson-Neal H. 2015. Myth-making and religious extremism and their roots in crises. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. [ Links ]

Norris, P. & Inglehart, R. 2011. Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Peres, M.F.P., Kamei, H.H., Tobo, P.R. & Lucchetti, G. 2018. Mechanisms behind religiosity and spirituality's effect on mental health, quality of life and well-being. Journal of Religion and Health 57(5):1842-1855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0400-6 [ Links ]

Ramzy, A. & McNeil, D.G. 2020. WHO declares global emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus spreads. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://nyti.ms/2RER70M [20 June 2020]. [ Links ]

Rob, A.B.A., Roy, S., Huq, S. & Marshall, K. 2020. Faith and education in Bangladesh: Approaches to religion and social cohesion in school textbook curricula. Berkley, CA: Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. [ Links ]

Skevington, S.M. & Böhnke, J.R. 2018. How is subjective well-being related to quality of life? Do we need two concepts and both measures? Social Science & Medicine 206:22-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.005 [ Links ]

Soga, M. & Gaston, K.J. 2016. Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14(2):94-101. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1225 [ Links ]

Stark, R. 2015. The triumph of faith: Why the world is more religious than ever. New York: Open Road Media. [ Links ]

Subbotina, N.D. 2001. Social in the natural. Natural in the social. Moscow: Prometey Publishing House. [ Links ]

Sutton, R. 2017. Reflex syncope: Diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Arrhythmia 33(6):545-552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joa.2017.03.007 [ Links ]

Zhukov, A. & Bernyukevich, T. 2018. Religious security of the Russian Federation as a reflection object of Philosophy and Religious Studies. MATEC Web of Conferences 212:10003. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201821210003 [ Links ]

Date received: 30 September 2020

Date accepted: 07 May 2021

Date published: 10 December 2021