Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Acta Theologica

On-line version ISSN 2309-9089

Print version ISSN 1015-8758

Acta theol. vol.41 n.2 Bloemfontein 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v41i2.5

ARTICLES

A Christian spirituality of imperfection: Towards a pastoral theology of descent within the praxis of orthopathy

D.J. Louw

Research Fellow, Department of Practical and Missional Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein. E-mail: djl@sun.ac.za ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4512-0180

ABSTRACT

The endeavour towards perfectionism in a praxis pietatis is most of the time described and portrayed as the preferential "narrow way", resulting in a kind of "theology of ascent" (the legalistic upgrading of human beings equipped with super, spiritual abilities). Rather than a spirituality of self-improvement, the article proposes a theology of descent (engaging with human suffering, weakness, brokenness, frailty, and imperfection), as well as a paradigm shift from orthodoxy to orthopathy. In a theology of descent, the following question emerges: How does the pastoral ministry address the painful realities of failure and existential imperfection as related to the limitations of suffering human beings? The author develops a Christian spirituality of imperfection, which implies the following spiritual movements of the human soul, namely from having to sharing; from possession to communion; from competition to compassion, from withdrawal to solidarity; from estrangement to engagement, and from hostility to hospitality. In this regard, Henri Nouwen's notion of a "wounded healer" plays a decisive role.

Keywords: Christian spirituality, of imperfection, Theology of ascent, Theology of descent, Orthopathy

Trefwoorde: Christelike spiritualiteit, van feilbaarheid, Teologie van opportunistiese voorspoed, Teologie van neerbuigende ontferming, Outentieke medelye

1. INTRODUCTION

As teenager (1958-1962), due to my understanding of 1 John 2:15-17, my impression of Christian spirituality was a kind of negating all forms of "worldly engagements". Rather than embracing and enjoying life, Christian spirituality revolved, at that time in my life, around acts of suppression and avoidance, in order to promote the demands and ethical stipulations of orthodox thinking (right belief or thinking). According to my understanding, many forms of pleasure were more or less equal to "lustful perversion". Sensuality and bodily desires should be totally rejected. The alternative was rigorous attempts to strive for perfection, while avoiding all forms of worldly and sexual desires. Instead of a spirituality of playfulness and enjoyment, the other dreadful choice was an unworldly escapism.

Is life in itself bad and creation merely about misery - a fatal divine experiment that failed, due to the fall and human disobedience? However, Genesis 1 and 2 do not start with a negative account. In fact, Genesis starts with a divine exclamation mark: "God saw all that he had made, and it was very good" (Gen. 1:31 NIV).1 Creation is described as fulfilment in terms of a telic dimension. The question is not whether life is perfect or not, but rather to what purpose is life created. The creation narrative records that God created over against nothingness (the darkness that can rob human beings of hope and meaning). Creation is an act of hope, despite the existential reality of human failure and imperfection. This is why the Bible gives no rational or causative explanation for failure, suffering, death, dying and imperfection. To be exposed to imperfection is a kind of existential, even ontic reality. Anxiety, guilt feelings, despair, loneliness, anger, fraud, greed, and hostility are facts of life that constantly remind us of the fact that human beings are frail and essentially imperfect.

Thus, the core question: How do we accommodate imperfection within a Christian spirituality of woundedness, and pastoral encounters facing misery and failure? Is the pilgrimage of Christian spirituality a summoning to embark on the so-called "narrow way", avoiding the temptations of the "broad way"? But what about the option of a third avenue: Orthopraxis as connected to orthopathy?

2. A DREADFUL CHOICE: JOY OF LIFE (HAPPINESS) (ODE TO JOY) OR ESCAPISM (THE VULGAR OF HUMAN DRIVES)?

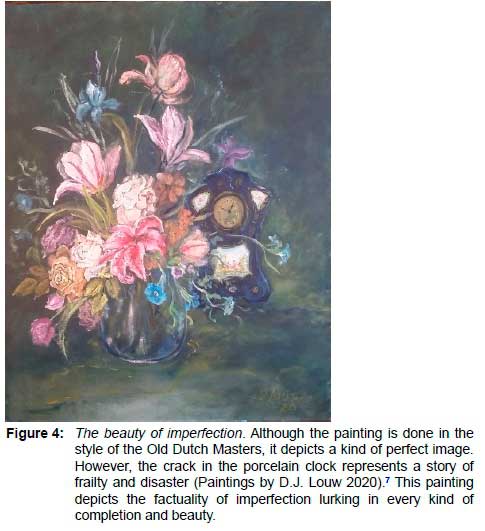

As mentioned earlier, the endeavour towards moral and spiritual perfection creates a form of spiritual escapism. It stands in stark contrast with Pablo Picasso's interpretation of life experiences as a display of joyful festivity: La joie de vivre (1946). The French phrase means a delight in being alive; keen, carefree enjoyment of living. It corresponds with sans souci, a carefree lifestyle without any worry or concern.2

For Picasso, the painting La joie de vivre (Figure 1) represents a feeling of great happiness and gay playfulness. He painted this after World War II as alternative to the dread of war and destruction. Although some of the colours still reflect the monochromatic composition of his portrayal of suffering, as in the case of Guernica, La joie de vivre vividly expresses his new sense of sensual enjoyment and a celebration of a newfound happiness. It could also be rendered as a parody on Henri Matisse's celebrated work Bonheur de vivre (1905-1906) - Joy of life. Joy and sorrow represent the ambiguity of life. Life is framed by both light and shadow.

For me as teenager, sheer La joie de vivre was impossible within the confines of what was communicated to me as "reformed spirituality" based on a "Calvinistic view on life". Thus, my rather legalistic interpretation and black or white approach to many intriguing ethical questions. The complexity of what is right and what is wrong totally excluded an aesthetic approach, i.e. the promotion and beautification of life by means of a cosmic spirituality of creatureliness and playfulness.

At that stage in my life, even a spirituality of enjoyment and beautification, as captured by Ludwig von Beethoven, was totally beyond the scope of my world view and framework of reference. In his Ode to joy (An die Freude; the final/fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony, completed in 1824), Beethoven captured a lifestyle of enjoyment, despite the shadow of imperfection, as follows:

Joy, beautiful spark of Divinity ... All creatures drink of joy/ At nature's breasts/ All the Just, all the Evil/ Follow her trail of roses /Kisses she gave us and grapevines/ A friend, proven in death / Salaciousness was given to the worm /And the cherub stands before God (Beethoven 2020).

Two factors dictated my understanding of spirituality in Christian faith. First, specific stipulations and prescriptions of the church on life issues. On my first synod in 1972, the Dutch Reformed Church reissued that dancing and swimming on Sundays are sinful activities and improper Calvinists. While teaching at the faculty of theology, the curatorium of the Dutch Reformed Church (1979) decided that all students who wish to enter the ministry must sign a document, promising that they will never dance. If not, they could not be ordained as ministers. Personally, I saw how many signed the document simply to make sure that they will be ordained, although they were involved in dancing activities at the students' hostels. In the meantime, the church still attempted to justify apartheid theologically, while Blacks could not study at the faculty. Ethically and theologically speaking, I was totally confused.

Secondly, the background of ideologic "Calvinism". Despite several (often skewed) interpretations of what an orthopraxis entails, many representers of a Calvinistic view on life issues tended to detect a kind of purity of faith (orthodoxy) that correlates with God's will, as deployed in several strict stipulations for daily practices: Right doctrine (orthodoxy) dictated right practice (orthopraxy). This was more or less my understanding of what was called Calvinism.

Pure Reformed Calvinism has therefore continually struggled to maintain its purity against the rise of various confessional deviations. Only by maintaining its purity can it be an effective alternative for non-Christian ideologies in society (Brümmer 2017:2).

Life unfolds under the spell of what was called God's general grace:

It preserves all human beings from the worst effects of sin and enables all humans to maintain an orderly society, to develop culture and to spread civilization in the world (Brümmer 2017:2).

Christian life is about a rigorously disciplined Christian deportment (Bouwsma 2020).

My personal directive for a praxis pietatis was aligned with 2 Colossians 2:23. Transferring my Christian sense of piety into practice, I associated a do-not approach with pious devotion and "Calvinism". This pious stance led to a dualistic sway between piety (inner life) and existential engagements (worldly behaviour) - the ideology of abstract privatism and escapism.

However, in my ministerial engagements, I started to realise that a reduced moralistic approach with the sole focus on legalism led most of the time to depletion in caregiving and the pastoral ministry. It could easily lead to the spiritual pathology of personal depletion (burnout) (Capps 1993) and compassion fatigue.3

Furthermore, a reduced form of moralism, fed by escapism, narrows life itself. Life becomes a small avenue, based on the fear for worldliness with only two basic options, namely the "narrow way" (salvation by means of negation and withdrawal) or the slippery "broad way" (damnation, due to sensual enjoyment and embodied forms of self-expression).

I still recall a poster (Figure 2) indicating the decisive choice between the so-called "narrow way" (Christian purity) and the "broad way" (the worldly desires of the flesh). I stood in front of that gate, totally afraid of the watchful and scrutinous eye of God, the scrupulous Judge. Christian spirituality should, therefore, consist of merely fear and trembling.

Within the background of a very pietistic and Puritan paradigm, the image of a "narrow way" contributes in my personal life to a very negative understanding of life. In this reduced paradigm, the Christian spiritual option was to make a clear ethical distinction between right (salvation as the good way) and wrong (damnation as the evil way). The only way to escape the temptations of the "narrow way" was to strive for moral perfection. Thus, the metaphor of a "pilgrim's progress" based on rigorous self-improvement.

3. HOPSCOTCH THROUGH LIFE: A PILGRIM'S PROGRESS - FLEEING FROM WORLDLY BURDENS

John Bunyan's Pilgrim's progress could be rendered as a classic in the literature on Christian spirituality. The Pilgrim's progress from this world, to that which is to come (1678) was written as a kind of allegory for spiritual growth; in other words, how to depart from becoming at home with the world and how to journey through life, in order to flee from sinful temptations, and being prepared to enter that which is to come. To embrace heaven, we should avoid hell (sinful temptations). We should not enter the "wicket gate" and, therefore, should leave home, wife, and children, to save ourself. In practice, this kind of spirituality implies a kind of existential displacement in worldly affairs.

Displacement means to discover the real "place of deliverance" (allegorically, the cross of Calvary and the open sepulchre of Christ). When we are relieved of the "burden of sin", a new passport is issued to enter the celestial city (Bunyan 2020). Another implication of this kind of spiritual pilgrimage is the mortification of all earthly desires.

4. THE MORTIFICATION OF ALL EARTHLY DESIRES - THE FIGHT AGAINST CONCUPISCENCE (THOMAS Á KEMPIS)

The core plot in Thomas Á Kempis' Imitation of Christ is to detect the Spirit of Christ (2004:Book One, First Chapter:1). The core challenge in Christian spirituality is to pattern our whole life on that of Christ.

In the pursuit of spiritual growth, we need to acknowledge the stumbling block of vanity. We must conquer the whims of evil inclinations. The spiritual challenge, therefore, is to master ourself and control the inclinations of the heart and worldly desires. We should grow stronger, advance in virtue, and become dictated by right reason, in order to obtain a clean conscience.

A virtuous life coincides with striving for perfectionism, although life is indeed imperfect.

Every perfection in this life has some imperfection mixed with it and no learning of ours is without some darkness. Humble knowledge of self is a surer path to God than the ardent pursuit of learning (Á Kempis 2004:10).

True peace of heart and spiritual maturity are found and accomplished in resisting passions, not in satisfying them. There is no peace in the carnal man, in the man given to vain attractions, but there is peace in the fervent and spiritual man (Á Kempis 2004:12).

Á Kempis (2004:14) poses the soul-searching question: Why were some of the saints so perfect and so given to contemplation? The answer and the summoning to root out all earthly desires:

Because they tried to mortify entirely in themselves all earthly desires, and thus they were able to attach themselves to God with all their heart and freely to concentrate their innermost thoughts (Á Kempis 2004:14).

The perfect way of the saints is, therefore, to become free from passions and lusts, uproot vices, and lay the axe to the root of all evil, namely human passions.

This emphasis on uprooting differs slightly from Bunyan's emphasis on fleeing from worldly passion. Á Kempis (2004:15) suggests a spirituality of patience and humility:

Many people try to escape temptations, only to fall more deeply. We cannot conquer simply by fleeing, but by patience and true humility we become stronger than all our enemies. The man who only shuns temptations outwardly and does not uproot them will make little progress; indeed, they will quickly return, more violent than before.

The example of the Holy Fathers should be followed.

They renounced all riches, dignities, honours, friends, and associates. They desired nothing of the world. They scarcely allowed themselves the necessities of life, and the service of the body, even when necessary, was irksome to them. They were poor in earthly things but rich in grace and virtue (Á Kempis 2004:19).

Humility, simplicity, and purity pave the way to God (Á Kempis 2004:3034). We should, therefore, seek a cross and martyrdom rather than rest and enjoyment for ourself. To despise the world and serve God is "sweet", for God is "sweet" (Á Kempis 2004:52-73). The core of the spiritual challenge to imitate Christ resides in acquiring the patience to fight concupiscence, to abandon many desires, pleasures, and our own wishes (Á Kempis 2004:54).

Very surprisingly, in his novel War and peace (1982), Leo Tolstoy referred to this very narrowed world view of Thomas Á Kempis. Tolstoy poses the question: Why such a reductionist view on life? He links his critical assessment to the following intriguing life questions:

What is wrong? What is right? What should one love and what hate? What is life for, and what am I? What is life? What is death? What is the power that controls it all? (Tolstoy 1982:407).

For Tolstoy, Á Kempis' spiritual reductionism should be linked to the human being's uneasiness with death,5 and the struggle in vain with perfectionism. Schoeman (2017:160) affirms Tolstoy's interpretation: The only absolute knowledge attainable by man is that life is meaningless.

For Tolstoy, Christian spirituality should rather focus on the goodness of life and the fostering of freedom and true humanity within the ethos of practising Christian love.

5. THE QUEST FOR "GOODNESS" AND "BEAUTY": LA PRINCIPALE FIN DE LA VIE HUMAINE AS ORTHOPATHY

While reading Tolstoy's War and peace (1982), with his emphasis on goodness, beauty, and purposefulness,6 I revisited the writings of Calvin. To my surprise, I discovered a totally different John Calvin.

According to Calvin, the key issue in Christian spirituality is the meaning and purposefulness of life: La principale fin de la vie humaine. Human life should be guided by spiritual issues, namely faith and the fundamental knowledge about God. Knowing God is an existential endeavour; it implies a new mode of living. Thus, his argument that God should be glorified through human life (pour estre glorifi, en nous) (Weber 1972:586). Why? Because the doxa of God is displayed throughout the whole of creation (splashes of glory captured by cosmic beauty). Due to the playfulness of salvation, the whole of life becomes a joyful event. In the words of Calvin: The world (cosmos) is a kind of theatre displaying the glory (doxa) of God (cosmos as theatrum gloriae) (Moltmann 1971:25).

The discovery of the cosmos as theatrum gloriae helped me move from a paradigm of worldly escapism to a paradigm of worldly embracement. In this regard, Calvin's question regarding the fundamental directives and principles for human life helped my rediscovering the Jewish and Christian wisdom tradition, with its emphasis on the knowledge of the heart (sapientia), as expressed in love and compassionate being-with the other. But then we have to discover the beauty within the different cosmic dimensions of life such as singing, enjoyment, laughing, humour and artistic expressions (art and painting). This discovery changed my lifestyle: From guilt feelings regarding cosmic joy to cosmic gratuity: Life as an opportunity to share, to reach out, to comfort, to make whole, to dignify, and to promote general, human well-being (the humanisation of life).

Previously, for me, the practice of Christian spirituality was closely related to the notion of "mission": Change yourself and evangelise the world. The discovery of the world as theatrum gloriae, and not as sinful space for continuous failure, evoked in me a new passion for life. Translated into pastoral terminology, it evoked a compassion for human misery and suffering; purposefulness became a challenge to reach out to suffering human beings in their plight for meaning and hope. I gradually discovered that the pastoral and fundamental theological question is not so much about the strategies of the missio Dei (the vocational dimension of spirituality and discipleship), but in the first place about the meaningful and hopeful dimension of the passio Dei (the engagement of the suffering Christ - the weakness of God - with the emphasis on compassionate being-with; the caring dimension in Christian spirituality - orthopathos; the art of living with brokenness in a meaningful way).

Orthopathos points in the direction of the question as to how we deal with human brokenness within the existential and unavoidable ontic polarisations: Life and death; light and darkness; healing and weakness; love (grace) and hatred (evil). The core question about the healing of life (cura vitae) (Louw 2008) shifted in the direction of the aesthetic endeavour, namely how pathos could contribute to finding meaning within the painful trajectories of loss, anxiety, guilt, despair, and suffering?

Inevitably, orthopathy leads to the theological question in practical theology: What is the link between a passio Dei and the human engagement with imperfection and human limitations? What is meant by "true spirituality" and how is the Christian praxis related to the so-called "narrow road" and its connection to the summoning in Matthew 5:48: "Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect"? Could it perhaps be that a spirituality of imperfection is nearer to "costly discipleship" (Bonhoeffer) than the "narrow road" of "contemptuous worldliness"? and that imperfection can fuel a deep sense of spiritual pleasure and enjoyment?

6. THE BASIC CHALLENGE AND PARADIGM SHIFT: FROM AVOIDANCE AND WITHDRAWAL TO THE SPIRITUALITY OF EMBRACEMENT (THE BONHOEFFER OPTION) AND ENGAGEMENT (THE PAULINE OPTION)

Orthopathy implies that Christian spirituality cannot avoid suffering, frailty, weakness, loss, and the reality of mortality within the realm of death and dying. Bonhoeffer (2020: n.p.) accepted this truth as a core pillar in Christian spirituality: "Cheap grace is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate." For Bonhoeffer (2020:n.p.), this kind of sacrificial ethics does not imply the loss of joy and beauty.

Music ... will help dissolve your perplexities and purify your character and sensibilities, and in time of care and sorrow, will keep a fountain of joy alive in you.

Thus, the basic presupposition: The challenge in Christian spirituality is not to avoid the emptiness of loss and pain, trying to sidestep the threat and anxiety of suffering and death, but to engage with frailty, weakness, and vulnerability. However, in the words of Bonhoeffer (2020:n.p.), we should not fill the gap of emptiness with the image of a punitive God:

It is wrong to say that God fills the emptiness. God in no way fills it but much more leaves it precisely unfilled and thus helps us preserve -even in pain - the authentic relationship.

We should rather engage the transitoriness of life within the mode of frolic gratitude:

Gratitude transforms the torment of memory into silent joy. One bears what was lovely in the past not as a thorn but as a precious gift deep within, a hidden treasure of which one can always be certain (Bonhoeffer 2020:n.p.).

Rather than withdrawal, the Pauline option is to differentiate between the source of Christian spirituality (a theology of the cross - the weakness of God is stronger than man's weakness, 1 Cor.:25), and the sacrificial offering of the body as act of worship (a liturgical investment in the transformation of life - being within the world). Orthopathy shows that Christian spirituality is not conformed to the pattern of this world (destruction, enmity, and hatred) (Rom. 12:1-2), but to the patterns of salvation and healing and hope-giving. We live in the interlude: Spiritual differentiation and bodily engagement within the confines of the beatitudes. The latter defines and demarcates the Christian pilgrimage directed by the habitual question: How do we journey through life?

7. JOURNEYING THROUGH LIFE: DISCOMFORT (SPIRITUAL UNEASINESS) WITHIN A COSMIC UNREST

In her travel journal Reisiger, Elsa Joubert (2009:428-429) describes her journey through life as a struggle with imperfection, which she calls a cosmic unrest and discomfort (uneasiness), due to our struggle to come to terms with suffering, frailty, and loss. It is about a kind of existential anxiety wherein we have to wrestle with the following questions: Why? From where? For what purpose (our destiny in life)? (Joubert 2009:429). Spirituality is then not about fleeing the world, but about the challenge to meet the cosmic forces of life as displayed in human vulnerability and a painful awareness of mortality, transience, and human imperfection.

In her book Spertyd (Joubert 2017:192), imperfection is more or less the discovery of nothingness, which we have to articulate before God when confronted with the following sheer reality: Life is determined by the cul-de-sac of death. This awareness penetrates the core of our being human and creates an existential experience of loss and anxiety (Joubert 2017:104). Within this cosmic unrest, she discovered that any attempt to try to cope and achieve (ek moet harder probeer), a kind of managerial peace, is, in fact, a sheer illusion (Joubert 2009:428-429).

The point is that to understand spirituality as an existential struggle with death and frailty and to internalise weakness and vulnerability as ingredients that demarcate imperfection in life means to become engaged with our existential anxiety and the reality of loss. They are the ingredients of life. Imperfection and death reveal the woundedness of the human soul (Joubert 2009:288). It challenges us to promote justice and foster human dignity. This is the reason why Joubert decided to write the long life journey of Poppie Nongena in her struggle with the apartheid regime, which led to a constant exposure of human displacement (Joubert 2009:252-264, 288, 277-278).

In our struggle to come to terms with frailty and imperfection, we have to face the reality that death destructs all our safe comfort zones and creates a sense of discomfort. Life is then about the spiritual energy (strength) to push forward against a "cloud of unknowing" (Joubert 2009:194). At this point, we are overwhelmed by imperfection, fear, helplessness, and vanity.

In Slot van die dag, Schoeman (2017:177) argues that a sense of vanity creates the space to move from being lonely to a spirituality of solitude, in order to deal with the cul-de-sac of life (Schoeman 2017:174) - the first step into the direction of compassionate solidarity. For Schoeman, imperfection implies more than fear; it brings about a dreadful hesitation and a sense of deadly temporality. Schoeman (2017:162) refers to a poem by Walt Whitman:

Come lovely and soothing death/ Undulate around the world, serenely arriving, arriving/ In the day, in the night, to all, to each,/ Sooner or later delicate death.

Thus, Schoeman's personal choice to end his life by making a personal and constructive decision: Self-termination (suicide). Instead of growth and ascent, his choice was for a deadly descent.

But is a deadly descent indeed the appropriate choice in terms of a Christian spirituality of beautification? It could perhaps be that imperfection can help us overcome our obsession with wealth, affluence, and egoistic expressions of perfectionism.

Could a confrontation with imperfection perhaps culminate into a lifestyle of pathetic engagements with frailty and death rather than the desperate obsession with wealth, importance, and prestige?

8. TOWARDS A "SMART SPIRITUALITY" OR A PATHETIC SPIRITUALITY OF IMPERFECTION?

In an affluent society, with the emphasis on achievement, flourishing and ascent, we need to reach the highest sport in life. We can call this striving: The obsession to become important, wealthy, and acknowledged; in other words, to establish "smart living" within the allure of globalisation: Living with smart phones in smart Dubai. According to an article in Time Magazine (2017), urbanisation is currently about the vicious attempt to ascent into the 21st century with its smart cities (Beresford 2017:3). In this regard, Dubai is described as "smart Dubai", the most intelligent city on earth and as a resort of "unifying happiness". According to Yousef Al-Assaf (2017:13), President of Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) Dubai, "[o]ther cities can learn a lot from Dubai's happiness strategy": Happy living = smart living = high tech living: instant happiness (Louw 2020:111-134).

8.1 The "smart spirituality" of ascent: Homo Deus

In theological terminology, this smart spirituality of ascent (the upgrading of human beings equipped with super-abilities), can be called the striving towards a kind of homo Deus prospect. In his book Homo Deus, a brief history of tomorrow, Yuval Harari (2016:46) captured this tendency as follows:

In the twenty-first century, the third big project of humankind will be to acquire for us divine powers of creation and destruction, and upgrade Homo sapiens into Homo Deus.

Homo Deus is the prospect of attaining

super-abilities such as the ability to design and create living beings; to transform their own bodies; to control the environment and the weather; to read minds and to communicate at a distance; to travel at very high speeds, and, of course, to escape death and live infinitely (Harrari 2016:47).

This business of acquiring super abilities is linked with the quest for absolute happiness. In his publication Happiness, Brown (2017:xv) remarks as follows:

Yet the desire to be happy, to obtain happiness, to claim our right to be happy, remains the most enduring and conspicuously self-defeating aspect of our modern condition.

8.2 The painful reality: The frail, vulnerable and mortal human being

Suddenly, at the beginning of 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic shattered the dream about a sans souci of smart life. Homo Deus is suddenly cut back to size: Homo doloribus (the suffering human being as being constantly exposed to sorrow). We are back to the predicament of Pierre Bezuhof in Tolstoy's War and peace: What is life? What is death? (Tolstoy 1982:407. See also note 4).

This business of creating a smart life, based on super abilities and the bliss of absolute happiness, stands in stark contrast with a spirituality of imperfection, dealing not with a homo Deus obsession, but with the frailty of life and the vulnerability of imperfect human beings. This is the reason why the Franciscan priest, Richard Rohr (quoted in Hernandez 2006:90-91), argues for a paradigm shift from an "ascent theology" to a "theology of descent". The latter refers to the existential reality of imperfection, displacement, and humble surrender. The spiritual focus is, therefore, less on spiritual advancement and more on personal woundedness.

8.3 Imperfectus hominum

A spirituality of imperfection means an attitude and aptitude of humility and simplicity in the human quest for meaning, purposefulness, and comfort framed by vulnerability, frailty, weakness, and woundedness. The connection with descent implies that the challenge in a spirituality of imperfection is to internalise suffering within a daily orientation regarding these coincidences that endanger our sense of security, safety, pleasure, and happiness. In this regard, imperfection is shaped by the unpredictability of life events as related to relativity and "fate". It is closely linked to what Taleb (2010) calls the Black Swan syndrome, namely the unpredictability of life events that occur without any reasonable or rational explanation.

According to Taleb (2010:8), the human mind suffers from three ailments, which he calls the "triplet of opacity", in other words, the illusion of understanding, the retrospective distortion, and platonification (i.e. the tendency to platonify, namely liking known schemes and well-organised knowledge to the point of blindness to reality) (Taleb 2010:131).

Imperfection should be linked to life's two inevitable realities and polarisations, namely our quest for meaning; the search for a sense of aliveness, pleasure, acknowledgement, and fulfilment, and the anxious awareness of death and dying. Life occurs within these two polarities and causes the space of a dynamic interlude: Light and darkness; vividness and degeneration (death). The dynamics of this polarisation is depicted in the painting The interlude - Life and death (Figure 3).

9. TOWARDS A SPIRITUALITY OF LIFE FULFILMENT AND MATURE COMPLETION (TELEION): THE HEALING AND BEAUTIFICATION OF LIFE

The text in Matthew 5:48 captures the connection between spirituality, meaning, purposefulness, and fulfilment (destiny and vocation). The word used for being perfect is teleion (IMAGEMAQUI adjective - nominative plural masculine; teleios, tel'-i-os: complete). It is used in general Greek in various applications of labour, growth, mental and moral character, and so on, referring inter alia to completeness or a person of full age indicating a kind of spiritual maturity. The core noun in teleion refers to telos as indication of achieving a goal or purpose (having reached its end).

Within the context of Matthew 5, spiritual completeness is about living life according to the directions of the beatitudes (Matt. 5:1-11). The whole notion of being perfect culminates in the summoning to be salt and light in human relationships (13-16); to fulfil the law (17-20), in order to promote life (not to kill or murder; vv. 21-25); to reconcile with the other and to settle matters following the principles of true wisdom - sapientia; to nurture the body, in order to establish trust in human, sexual and marital relationships (vv. 27-30); to exhibit trustworthiness, faithfulness and truth when taking oaths (integrity) (vv. 33-37); to link reconciliation to justice, in order to promote human dignity (vv. 38-42), and to heal life (the beautification of life) by exercising the basic principle of unconditional and sacrificial love by means of the directive: love your enemy (vv. 43-47). To live a virtuous live (completeness) should culminate in reaching out; in charity by sharing our belongings and helping people in need without expecting any rewards or grateful feedback (Matt. 6:1-4). In fact, Matthew 5 depicts "the narrow road" of Christian spirituality not as a fleeing from ... (the perfection of legalistic self-improvement), but as an engaging with ... (the woundedness of compassionate reaching out). This may be the reason why Luke 6:36 supplements Matthew 5:48 exegetically and hermeneutically by explaining: "Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful" (NIV). Completeness coincides with pity, compassion, and mercy (grace).

Hernandez (2006:89-90) aptly captures the core meaning of teleion (being perfect - completion, spiritual maturity):

Perfection is about complete freedom to love, not necessarily freedom from flaws. For one thing, the Greek word used in the Matthean text, teleios, has more to do with the idea of 'completeness' than [with] freedom from fault or error.

The fact is that spiritual limitations "inhere in human condition" (Hernandez 2006:93). Nouwen (1979) captured the core of a spirituality of imperfection by referring to the orthopathos of The wounded healer. Ministry in contemporary society.

Caregivers are lonely people in the sense that in helping people in their pain and loss, they are always confronted by existential loneliness, pain and woundedness. Caregivers have to care for lonely people, while being intensely aware of their own weakness.

He [caregiver] is called to be the wounded healer, the one who must look after his own wounds but at the same time be prepared to heal the wounds of others (Nouwen 1979:82).

Christensen (2006:xi) summarises Nouwen's spirituality of imperfection:

Brokenness and woundedness are part of what it means to be human. Weakness and vulnerability are part of the strength of our spirituality.

10. FEATURES OF A SPIRITUALITY OF ORTHOPATHOS IN A THEOLOGY OF DESCENT

Descent means the act, process, or fact of moving from a higher to a lower position; a downward inclination or slope; a passage or stairway leading down. In theological and ecclesiological terminology, it means to move from the clerical paradigm of orthodoxy (top-down approach) to the orthopraxy of bottom-up; in other words, being there with compassion where they are (engaging with human suffering, weakness, brokenness, frailty imperfection). A descent approach provides real entrance to the existential reality of the human "soul" and the core, ontic realm of our very being as shaped by the polarities of striving for life fulfilment (completeness, wholeness) and simultaneously dealing with loss, death, and dying (mortality and fragmentation).

Descent theology focuses on downward mobility. It manifests in servanthood, solidarity, compassionate being-with, and a praxis of hospitality. In terms of Nouwen's (quoted in Hernandez 2006:40) concept of the wounded healer, the downward movement implies a movement towards solidarity with

the way of the poor, the suffering, the marginal, the prisoners, the refugees, the lonely, the hungry, the dying, the tortured, the homeless -toward all who ask for compassion.

This concerns a movement from estrangement to engagement, from enmity to hospitality - the enemy becomes "my guest".

Keeping Nouwen's proposal for a "wounded-healer" approach in mind, a descent theology within the framework of a spirituality of imperfection consists of the following ortho-pathetic challenges in caregiving:

• Integrating our brokenness as a way and mode of being human in this world to achieve spiritual wholeness: reconciling and being at peace with God and fellow human beings (the other as stranger).

• Living within the sound, often paradoxical tension between "interiority" and "exteriority". They are never exactly the same but coincide where human wholeness and healing are at stake. For instance, the Chilean writer Segundu Galilea (in Hernandez 2006:50-51) aptly pointed out that the concept of "integral liberation" implies the coincidence of social engagement (solidarity) and the spirituality of interior transformation (divine contemplation).

• Living within displacement implies that, due to the spiritual tension, we live within worldly and existential realities of loss and pain but are shaped and motivated by categories stemming from the transcendent realm of the passio Dei: The suffocating cry of divine forsakenness as expressed in Chris' vicarious suffering (we are in the world but not from the world). A spirituality of imperfection is about the ecclesial praxis of making home for the homeless.

• Befriending mortality. The anxiety for death is a common factor in human life. Mortality and loss should, therefore, be recognised and acknowledged as features of life so that we can use our brokenness as an ingredient to grow into maturity rather than as an intoxicating factor contributing to the pathology of denial and anxiety (fear for loss).

• Expressing the experience of loneliness and forsakenness as a prayerful expression of suffocation and the cry for mercy and divine pity. Nouwen noted that every eucharistic celebration starts with a cry for God's mercy (the Kyrie Eleison) and so open acknowledgement of our own part in the brokenness of our condition (in Hernandez 2006:77).

• Engaging with experiences of victimisation. It is important to link with the fact that when I am the victim, I am also sometimes the perpetrator. I then become an agent of change rather than a masochistic sufferer.

• Becoming compassionate about a ministering of failure, i.e. to be graceful to our own failures, in order to reach out to the failure of others.

• Voluntarily accepting the so called "my-cross" (impairments), in order to move "downwards" to the crosses others have to carry in their struggle to survive meaningfully, as well as the challenge of proceeding forwards into new spaces of embracement and hospitable caring.

• Exercising radical self-abnegation, not as a kind of self-denial but as a constructive element in our spiritual attempts to grow into strength (the Christian parrhesia - boldness of being and speech) and, thus, to beautify life.

• Enjoyment of life and "worldly pleasures" are expressed in acts of healing such as the preservation and conservation of nature, and acts of diaconical sharing and compassionate reaching out; being grateful for the beauty of creation and life; nurturing existential desires and bodily sensuality for creating intimate spaces for unconditional love; trustworthy modes of friendship; practices of justice, and the promotion of human dignity.

• Learning the spiritual lesson that the link Calvary-justification inevitably leads to the link loss-sanctification, because dealing with victory over failure and the flaw of sinfulness often implies to negate, in order to gain.

• Expressing dissatisfaction and discomfort, due to pain and loss as a way of being honest to God. Rather than the illusive wish that God should keep pain away from us, acknowledging pain becomes an avenue for true communion with God.

• Discovering in painful experiences of loss and suffering how God partakes in every mode of human deformation by means of the vicarious suffering of Christ and the act of divine substitution: God in my place, on my behalf (not God as opponent and gruesome causative factor - God not behind suffering but within suffering).

• The spiritual challenge of combatting all forms of dehumanised suffering by saying "no" to violent destruction and "yes" to graceful healing and restitutive justice - the humanising of dehumanising structures in life.

• The beautification of ugliness. In the passio Dei, Christ became the ugly suffering Servant so that in the diakonia of love, we can start to beautify life and offer human beings the space to recapture their human dignity. The summoning of a normative and virtuous spirituality resides in the following imperative: Display unconditional love - the agape factor despite imperfection.

11. CONCLUSION

In the paradigm shift from a theology of ascent to a theology of descent, a spirituality of imperfection implies a spirituality of accommodation, namely living within the ambiguity and often paradoxical character of daily coincidences. It is sensitive to an awareness of the unpredictability of life events.

In its link with imperfection (transience), the realism of wisdom is captured by Ecclesiastes 5:18-20. Life is viewed as a gift of God and should be merged with a habitus of gratitude. Gratitude beautifies life: fides quaerens beatitudinem (faith seeking the beautification of life) (Louw 2020). The happiness and enjoyment8 that emanate from eating and drinking and toilsome labour, even the awareness of the temporality of life, its shortness, brevity and transience, do not restrict what we can call a theology of grateful happiness.

When God gives any man wealth and possessions, and enables him to enjoy them, to accept his lot [imperfection; all is in vain; life is unpredictable] and be happy in his work - this is a gift of God (Eccl. 5:19).

Even though life is also about a chasing of wind, the steering factor is that God gives wisdom, knowledge, and happiness (Eccl. 2:26).

• Imperfection coincides with a spirituality of displacement in our journey through life, i.e. the pilgrimage of completion (wholeness and fulfilment - the space and place of grace). Imperfection deals with the spiritual pathology and intoxicating as well as xenophobic exclusivity of "my place" and the space of exclusive me obsessions.

• A spirituality of imperfection is a yearning for a spirituality of joy - starting to embrace human embodiment and pleasure as meanings to discover that, in spite of impairment, life and cosmic experiences are on a daily basis exposed to the beauty of the human desire for pleasure, play, friendship, healing, constructive change, and peace (the pilgrimage of the beatitudes). In this sense, the beautification of life is prepared to deal with the spiritual pathology and intoxication of worldly escapism and the legalism of fleeing from ...

• A spirituality of woundedness should be rendered as the first step into care, healing, helping, and flourishing (happiness). A spirituality of woundedness should, thus, be supplemented by a spirituality of happiness. This could be achieved by a praxis of compassionate being-with the other wherein we are prepared to deal with the spiritual pathology and intoxicating artificiality of "good luck" - happiness as merely an obsessive indulgence in selfish satisfaction of needs and the ascent of achievement ethics (I need to be a winner at all costs).

• Imperfection implies a spirituality of humility as the discovery of our own limitations, in order to move from selfish self-attachment to the freedom of other-involvement (dealing with the exclusivity of self-maintenance at the expense of the other - the greedy exploitation of the other and life and environment).

• Imperfection culminates in a spirituality of simplicity as the habitus of becoming free from the my obsession and the thing obsession to the enrichment of sharing and diaconical reaching out - the spiritual movement from having to sharing; from possession to communion; from competition to compassion (dealing with the spiritual pathology and intoxication of excessive wealth and affluent prosperity); from withdrawal to solidarity; from estrangement to engagement; from hostility to hospitality.

Imperfection and the fear of death coincide. Hence, the following proposition by Pierre Bezuhof regarding the art of meaningful living (Tolstoy 1982:1000; see also note 4):

Man can be master of nothing while he is afraid of death. But he who does not fear death is lord of all. If it were not for suffering, man would not know his limitations, would not know himself.

To embrace death, imperfection should be merged with simplicity - the art of persisting in the divinity of sacrificial love.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Á Kempis, T. 2004). The imitation of Christ. Electronic version. The Catholic Primer (Public Domain). [ Links ]

Al-Assaf, Y. 2017. Future city. The Buzz Business. In: Time Magazine, 20 November, pp. 1-15. [ Links ]

Beethhoven, L. 1824. Ode to joy. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ode_to_Joy [7 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Beresfürd, M. 2017. Future cities. The irresistible rise of urbanization. Time Magazine, 20 November, p. 3. [ Links ]

Bonhoeffer, D. 2020. Dietrich Bonhoeffer Quotes. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/29333.Dietrich_Bonhoeffer [7 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Boüwsma, W.J. 2020. Calvinism. Encyclopedia Britannica. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Calvinism [12 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Broad and Narrow Way 2020. Depiction of broad and narrow way in the Orthodox tradition. Orthodox Tradition. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://za.pinterest.com/pin/105412447499046567/. Public domain. [7 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Brown, D. 2017. Happy. Why more or less everything is fine. London: Corgi Books. [ Links ]

Brummer, V. 2017. Predestination and evangelical spirituality: Neo-Calvinism in South Africa. Litnet, Academic Research, 16 February. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.litnet.co.za/predestination-evangelical-spirituality-neo-calvinism-south-africa/ [1 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Bünyan, J. 2020. The pilgrim's progress. Wikipedia. [Online.] Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pilgrim%27s_Progress [7 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Capps, D. 1993. The depleted self. Sin in a narcissistic age. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. [ Links ]

Christensen, M.J. 2006. Foreword. In: W. Hernandez, A spirituality of imperfection (New York/Mahwah: Paulist Press], pp. i-xi. [ Links ]

De Heer, C. 1969. Makar, Eudaimõn, Oblios Eutyche. A study of the semantic field denoting happiness in Ancient Greek to the end of the 5thcentury B.C. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert Publisher. [ Links ]

Harrari, Y.N. 2016. Homo Deus. A brief history of tomorrow. London: Harvill Secker. [ Links ]

JOÜBERT, E. 2009. Reisiger. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

JOÜBERT, E. 2017. Spertyd. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Kranendonk, D. 2012. Did John Calvin bowl on the Sabbath? Reformed Resource.net. [Online.] Retrieved from: http://reformedresource.net/index.php/sabbath-observation/59-did-john-calvin-bowl-on-the-sabbath.html [10 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J. 2008. Cura vitae. Illness and the healing of life. Wellington: Lux Verbi. [ Links ]

Louw, D.J. 2020. The search for happiness. Towards a practical theology of joy: Faith seeking beatific happiness - Fides quaerens beatitudinem. International Journal of Practical Theology 24(1):111-134. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijpt-2018-0006 [ Links ]

Moltmann, J. 1971. Die ersten Freigelassenen der Schöpfung. Versuche an der Freiheit und das wohlgefallen am Spiel. München: Kaiser Verlag. [ Links ]

Moschella, M.C. 2016. Caring forjoy: Narrative, theology and practice. Boston: Brill. [ Links ]

NouwEN, H.J.M. 1979. The wounded healer. Ministry in contemporary society. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. [ Links ]

Picasso, P. 2020. La joie de vivre. Picasso La joie de vivre, 1946 [Online.] Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Pablo-Picasso-La-Joie-de-Vivre-1946-Musee-Picasso-Antibes-France-194614_fig1_272251676 [7 September 2020]. Public domain; for academic purposes only. [ Links ]

Reihlen, C. 2020. Poster: The broad and the narrow way. Translated from the original German by Miss Marriott, Mildmay Deaconess. Private Collection - © Peter N Millward). [Online.] Retrieved from: https://pictureswithamessage.com/78/181.htm [7 September 2020]. [ Links ]

Schoeman, K. 2017. Slot van die dag. Gedagtes. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis. [ Links ]

Taleb, N.N. 2010. The black swan. The impact of the highly improbable. London: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Tolstoy, L.N. 1982. War and peace. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. [ Links ]

VAN DER MERWE, C. 2015. Donker Stroom. Eugène Marais en die Anglo-Boereoorlog. Kaapstad: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Weber, O. 1972. Grundlagen der Dogmatik I. Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag. [ Links ]

Date received: 12 November 2020

Date accepted: 6 August 2021

Date published: 15 December 2021

1 In Genesis 1:31, "very good" (the text adds IMAGEMAQUI, meod - very) refers to appropriateness and a kind of divine delight regarding the beauty and purposefulness of creation. In Revelation 4:11, the connection honour, glory, and power emphasise the link between creation and the reflection of the mind and will of God.

2 The castle of Fredrich the Great in Potsdam, Berlin, was called Sans Souci in order to reflect, even in the architecture of the palace, a lifestyle of sheer enjoyment. The palace was designed/ built by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff between 1745 and 1747 to fulfil King Frederick's need for a private residence where he could relax away from the pomp and ceremony of the Berlin court. The palace's name emphasises the quest for enjoyment and happiness. The French phrase sans souci translates as "without concerns", meaning "without worries" or "carefree" and symbolises the palace as a place for relaxation rather than a seat of power.

3 Capps (1993:97-98) relates depletion to self-failure. It is related to self-pathology and self-fragmentation within our narcissistic age, with its emphasis on productivity and achievement.

4 The poster (Figure 2) stems from an interpretation by Charlotte Reihlen (1867): "The foreground of our picture, as above described, is occupied with a descriptive representation, comprehensive and universal, referring to all men without exception. It leads us at once to the place of decision that is so near, and at the same time shows us the great difference between the two gates and the two ways. For, evidently, the people, standing on the common entrance ground, of high or low rank, old or young, men or women, nobles, burghers, or peasants, are preparing to set out in one direction or the other. Yet before doing so they turn to the wooden sign-post standing in the middle, painted with alternate bright and dark stripes, as if to indicate that the choice of one of the paths leads to the joyous light of everlasting day, but the other to the sad darkness of the hopeless night of despair. The two arms of the sign-post express this further in a most unmistakable manner, as one of them is turned towards an open and very narrow gate, and bears the inscription - 'Life and Salvation', whereas the other is directed towards a beautiful, wide-open portal, and bears the inscription - 'Death and Damnation'". (Reihlen 2020).

5 The fact of death and dying confronts us with our own failure and weakness (Tolstoy 1982:411). This realisation linked the main character Pierre Bezuhov with Thomas Á Kempis' writings which somebody sent him. Weakness appears to drive us into the bliss of believing in the possibility of attaining perfection (Tolstoy 1982:414). However, this striving for perfection, by using our freedom and force, time and again confronts us with imperfection and failure; it forces us to fall back into the pit of fatalism, while facing the irrationality within the sequences of historical events (Tolstoy 1982:717). In this regard, the French Emperor, Napoleon, with his passion for war, power, control and attempts to create peace by means of personal, autocratic endeavours, only produces "armed peace" - an irrational rationale, the illusion of perfect control. Instead of attaining goodness and truth, the evil and falsehood of life prevail (Tolstoy 1982:635).

6 The question was often posed: Did Calvin play bowls on a Sunday? By referring to a publication by Chris Coldwell, Kranendonk (2012:1) remarked as follows: "Calvin in the hands of the Philistines. Did Calvin bowl on the Sabbath?" (1998): "Among those who desire a Lord's day occupied with a broader range of activities than ones focused on the Lord, some appeal to Calvin's practice. They claim that one Lord's day, John Knox, the Scottish Reformer, visited his Genevan friend, John Calvin, and found him bowling. However, some years ago Chris Coldwell researched this account and concluded this account lacks a historical basis. First, Calvin's teaching on the Sabbath would contradict with him bowling on the Sabbath. As John Primus writes, 'Calvin calls for a literal, physical cessation of daily labour on the Lord's Day, not as an end, but to provide time for worship of God. Recreational activity should also be suspended, for such activity interferes with worship as certainly as daily labour does.' Not only are people to attend worship services, but also to devote 'the rest of the time' to the Lord. If he preached against gaming, it is highly unlikely he would have engaged in it."

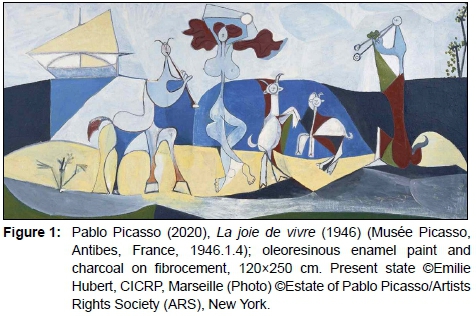

7 The porcelain clock as well as our home was totally destroyed in the Ceres earthquake on 29 September 1969. The following day, I gathered all the pieces and painfully restored the beautiful, antique clock. However, I could not find one small part. To commemorate the event after fifty years, I did the painting in the style of the old Dutch masters. On the top of the clock, on the right-hand side, the crack could still be identified. It reminds me of the fact that the crack of imperfection lurks in every form of beauty. Thus, the name of the painting: The beauty of imperfection.

8 In his dissertation on the semantic field denoting happiness in Ancient Greek, De Heer (1969:1) pointed out the difficulty to determine the meaning of concepts such as eudaimõn and makar. Happiness and the pursuit of happiness were not so much about personal needs and individualistic concerns. They rather described a heroic way of life. My argument is that happiness in Christian spirituality is related to three basic categories, namely the benevolence of blessing (eulogia); the well-being of happiness (makarios), and the sacramental enjoyment of life determined by xaris (good grace) (eucharistia). The concepts are used in different texts and contexts and should thus be read within a hermeneutical network that can be called a kind of makariology: Life directed by the benevolence of grace, the mindset and attitude of sjalõm, and the enjoyment of the sacramental gift of life (Louw 2020:111-134). Moschella (2016) designs a theology of joy, in order to provide a spiritual framework and source of hope in the darkness of suffering.